Nos convertimos en coeditores de Latin American Antiquity (LAQ) el 24 de abril de 2020, aunque estuvimos trabajando y aprendiendo con los coeditores salientes, Geoffrey Braswell y María Gutiérrez, desde febrero de ese año. Nuestra asunción como editores coincidió con la propagación del coronavirus. Las instituciones cerraron sus puertas y se pidió a los empleados que trabajaran a distancia para ayudar a frenar la propagación del virus. La gente se vio imposibilitada de viajar a los centros de investigación, de acceder a los laboratorios o de presentar sus investigaciones en conferencias. Los que se dedican a la enseñanza enfrentaron, a mediados de marzo, un cambio inmediato a la enseñanza a distancia, mientras que las personas con hijos se enfrentaron al cierre de las guarderías y las escuelas, y sus hijos se convirtieron en alumnos a distancia también, sin suficiente equipo ni capacidad de internet para conectar a todos los miembros de la familia. La preocupación por el contagio, la pérdida de interacción con amigos y familiares, el miedo a perder el trabajo o incluso la vida, la necesidad de hacer frente a la brecha digital y muchas otras preocupaciones se combinaron para crear uno de los años más difíciles y estresantes que muchos de nosotros hemos vivido. Escribir esta editorial a principios de abril de 2021, es un buen momento para analizar cómo autores y revisores de LAQ se han visto afectados por el estrés y las tensiones de la pandemia.

Durante la primera semana de marzo de 2019, Calogero viajó a Olavarría, pueblo ganadero y hogar de María Gutiérrez al suroeste de Buenos Aires, para aprender a manejar la plataforma editorial de LAQ, bebiendo litros de yerba mate. Este fue el último viaje de Calogero fuera de Chile, y el último bife de chorizo que comiera antes de quedar completamente recluido en Arica. Mientras tanto, Julia intentaba hacer Zoom con Geoffrey Braswell y los instructores de Cambridge University Press, descubriendo lo terrible que era el servicio de internet de su casa en la zona rural de Pensilvania. Julia se encontraba en un año sabático con todos los planes de viaje cancelados. Natalia Villavicencio, nuestra asistente editorial con sede en Santiago de Chile, ha hecho malabares para cumplir con las demandas de LAQ y sus obligaciones como postdoctorante en medio de las prohibiciones para realizar trabajo de campo y el acceso al laboratorio.

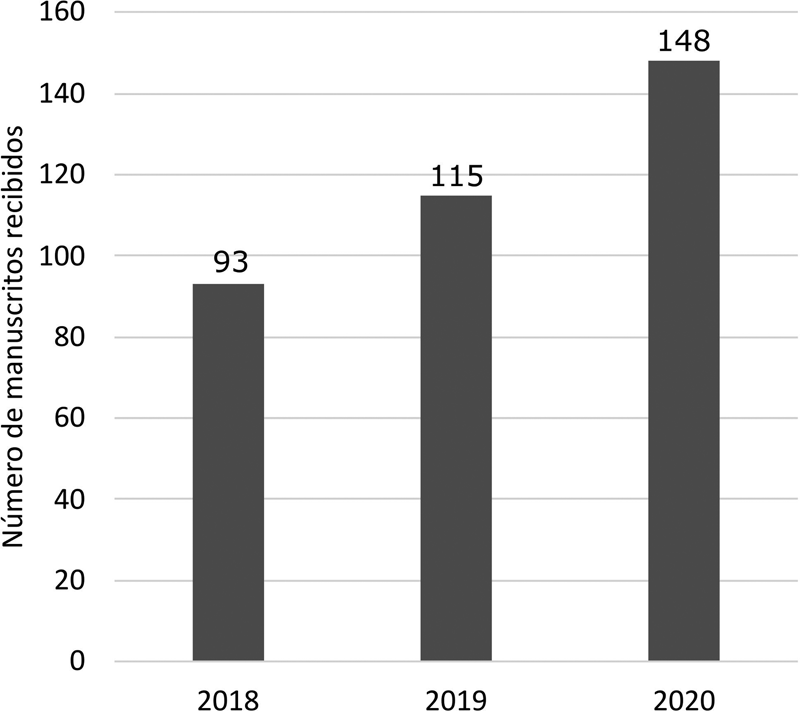

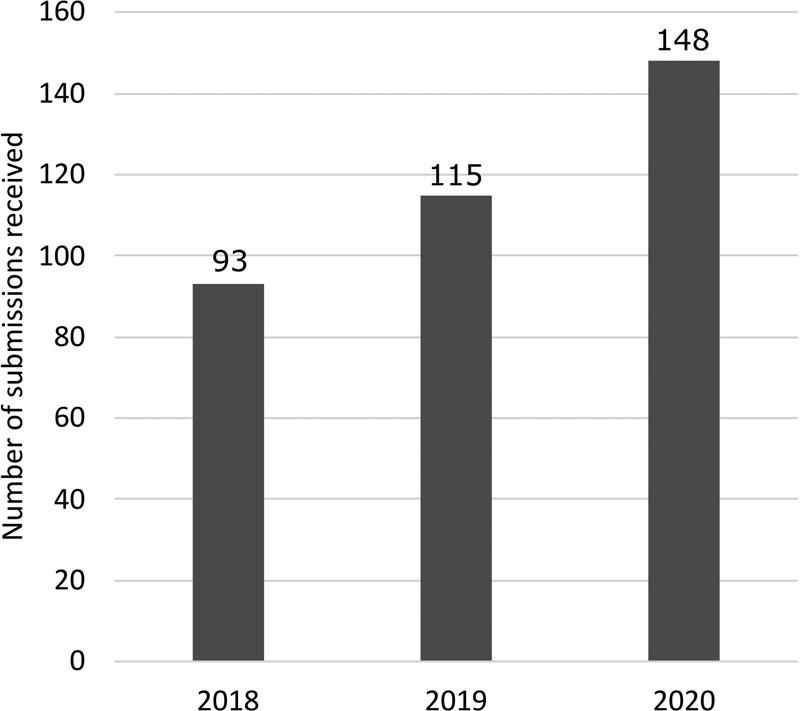

Como era de esperar, heredamos varios manuscritos que se encontraban en distintas fases del proceso editorial. Si comparamos 2020 con los dos años anteriores, vemos un aumento constante del número de envíos (Figura 1). Durante 2020, el 82% de los envíos llegaron entre el 1 de abril y el 31 de diciembre, coincidiendo con el periodo en el que gran parte de la humanidad estuvo recluida. El número de manuscritos de los tres primeros meses de 2021 (41) es mayor que los del primer trimestre de 2020 (27). La tramitación de estos envíos desde la recepción inicial hasta la decisión final se ha visto afectada por el hecho de que todos los implicados —editores, revisores y autores— han tenido que hacer frente a las tensiones ya comentadas. Agradecemos la paciencia de todos los participantes en la tramitación de este gran número de manuscritos hasta la decisión final.

Figura 1. Manuscritos recibidos entre 2018 y 2021 (ilustración de Natalia Villavicencio, utilizada con su permiso).

Algo que nos preocupó desde el principio fueron los informes de que las mujeres académicas e investigadoras se vieron especialmente afectadas por las consecuencias de la pandemia (véase, por ejemplo, Flaherty Reference Flaherty2020; Fulweiler et al. Reference Fulweiler, Davies, Biddle, Burgin, Cooperdock, Hanley, Kenkel, Marcarelli, Matassa, Mayo, Santiago-Vàzquez, Traylor-Knowles and Ziegler2021; Gewin Reference Gewin2020; Squazzoni Reference Squazzoni, Bravo, Grimaldo, García-Costa, Farjam and Mehman2020; Viglione Reference Viglione2020). Hasta ahora, estos análisis se han centrado sobre todo en las contribuciones a los servidores de preimpresión y a las plataformas de informes registrados por parte de las mujeres (según su nombre) que trabajan en campos STEM. El hecho de que las mujeres en el mundo académico están perdiendo tiempo de investigación se confirma en un informe de la National Bureau of Economic Research de los EE.UU. (Deryugina et al. Reference Deryugina, Shurchkov and Stearns2021). Los resultados de la encuesta revelan que las académicas con hijos son las más afectadas, pero los padres en general son los más impactados. Una joven académica de la Universidad de Tarapacá y madre de dos hijos ha dicho a Calogero, “aparte de las preocupaciones físicas e intelectuales que demanda la vida de todos los seres que viven dentro del hogar, las mujeres tenemos una carga emocional que no es reemplazada con nada, ni por nadie”.

Dado que LAQ es una revista revisada por pares que no publica preimpresos, el tiempo que transcurre entre el envío y la publicación es demasiado largo para abordar eficazmente los efectos de la pandemia. Como editores, tenemos acceso a datos algo más actualizados a través del sistema de envío en línea, Editorial Manager (EM). EL EM no incluye información sobre la identidad de género de un individuo. Por lo tanto, nuestro análisis (al igual que los de los investigadores que aparecen en como reportan los artículos citados anteriormente) nos obligó a asignar un género presunto a nuestros autores y revisores. Lo hicimos mediante una combinación de nombres, biografías en la web y conocimiento personal. Somos conscientes que este enfoque no es el ideal porque reduce un complejo conjunto de identidades a un género binario. No obstante, creemos que el intento de evaluar diferencias de género entre nuestros autores y revisores merece la pena y se suma a la creciente literatura sobre mujeres y hombres investigadoras y académicas. Parte de la información presentada aquí está incluida en Herr y colaboradores (Reference Herr, Gamble, Hendon, Santoro and Rieth2021). Hemos utilizado estos datos, junto con la información adicional extraída del EM, para observar más de cerca el tiempo antes y después del cierre de COVID-19. Para simplificar la búsqueda, elegimos como período anterior a COVID-19 hasta el 1 de abril de 2020. También elegimos comenzar nuestras comparaciones con el año 2018. Los individuos cuyo género percibido no pudo determinarse no están incluidos en nuestras figuras.

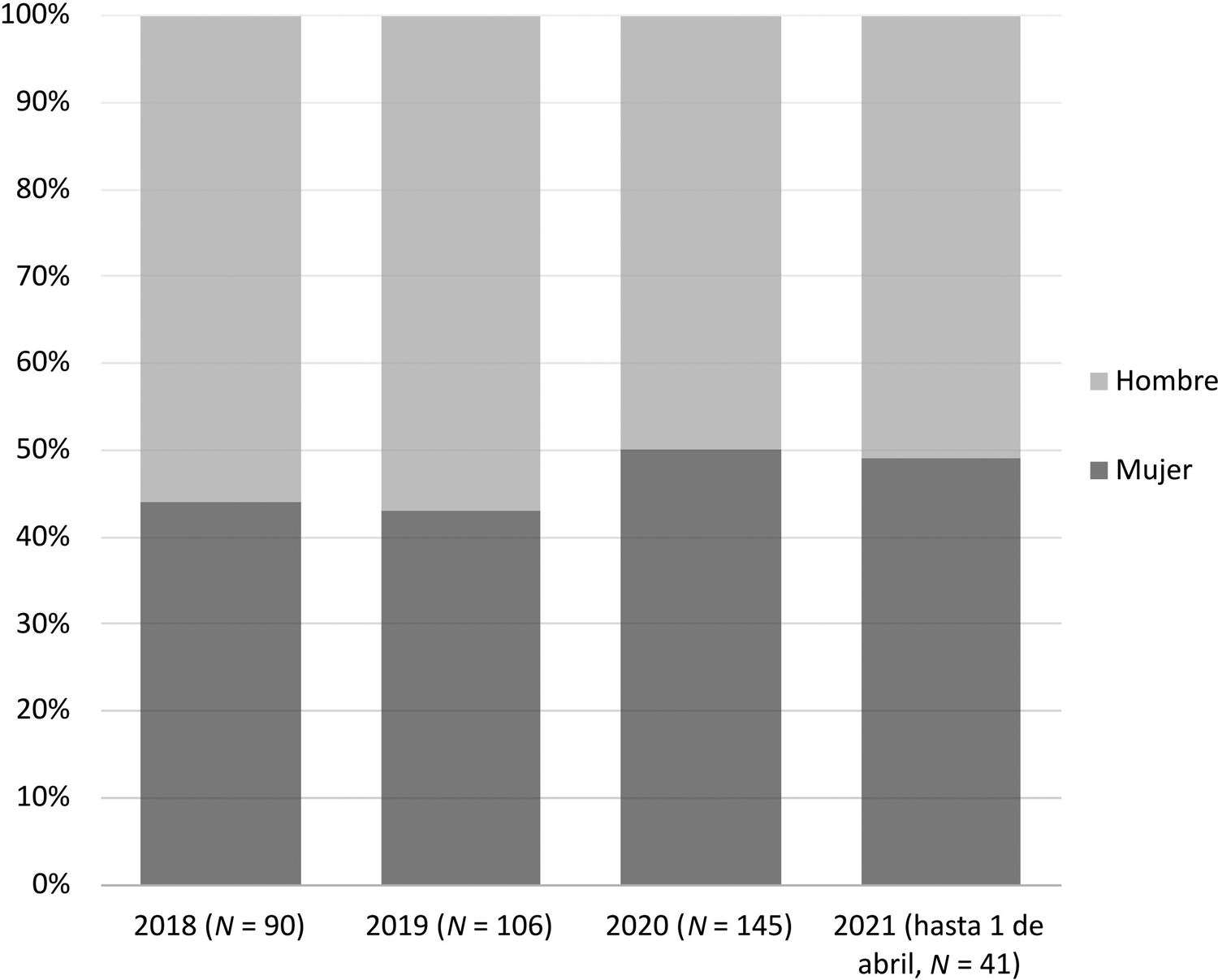

La mayoría de los envíos a LAQ tienen dos o más autores: 67% en 2018, 81% en 2019, 82% en 2020 y 76% en 2021 (hasta el 1 de abril). Hemos optado por utilizar el género del autor correspondiente (AC) para nuestra comparación. En el caso de los envíos con varios autores, el autor correspondiente es el autor principal en el 90% o más de los casos. Incluso cuando el AC no es el autor principal, la base de datos de EM vincula cada presentación a su nombre, haciendo que el AC sea el principal punto de contacto. Recibe las revisiones de los pares y los comentarios editoriales. Debe atender a todas las consultas relacionadas con la corrección de textos, la calidad de las imágenes, la información faltante, etcétera. En el marco del creciente impulso de Cambridge University Press para el acceso abierto a las revistas, es la afiliación institucional del AC la que determina si el manuscrito está cubierto por un acuerdo de publicación y lectura libre entre su institución y Cambridge. Una vez publicado el artículo, el AC es el principal punto de contacto para los lectores de la revista.

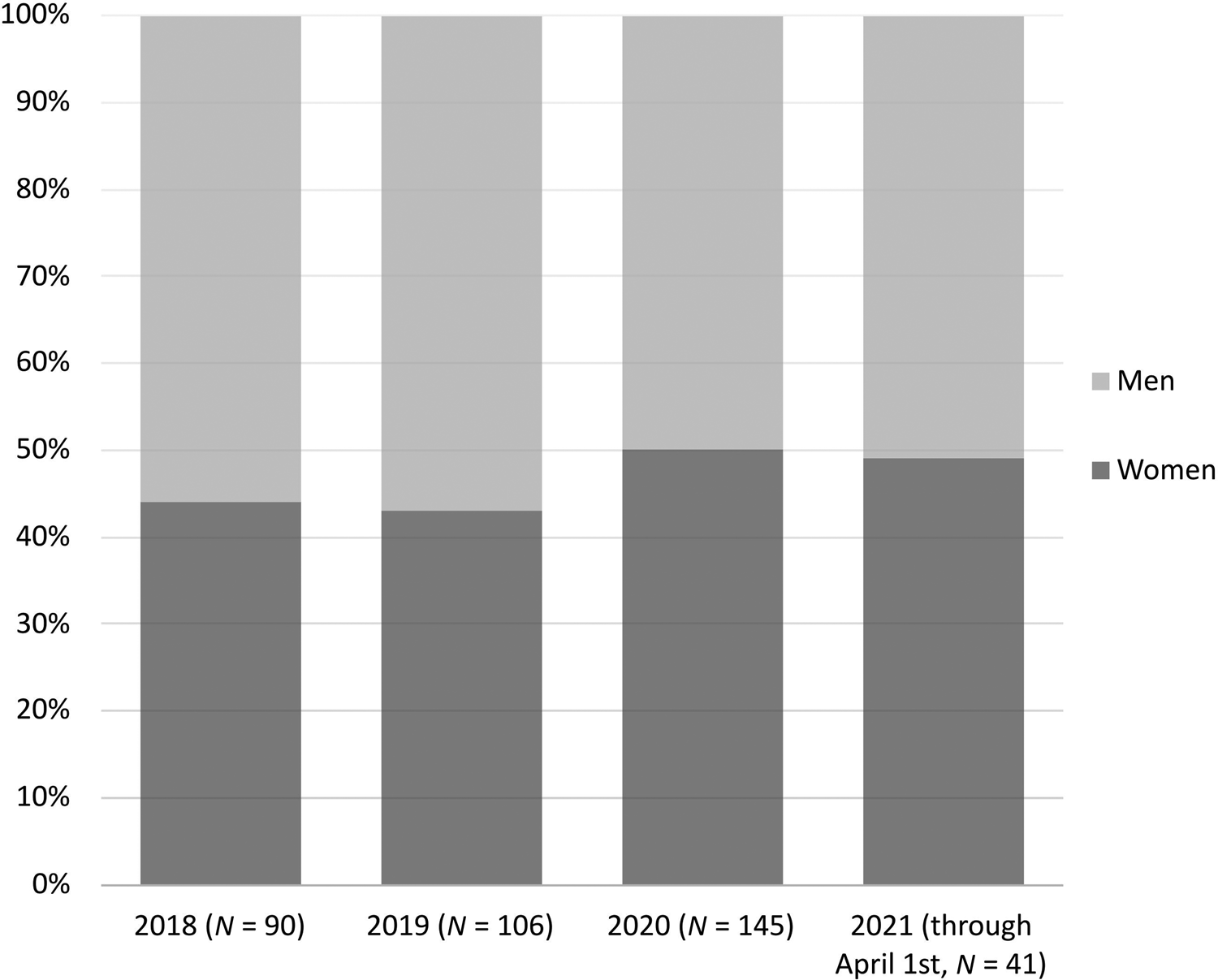

Durante los dos primeros años de nuestra comparación, hubo más hombres que mujeres como AC (Figura 2). En 2020, las mujeres alcanzaron la paridad con los hombres, con un ligero descenso en 2021. Los índices de aceptación también han pasado a una representación más equitativa de la autoría por parte de mujeres y hombres (Figura 3).

Figura 2. Género atribuido al AC para manuscritos enviados entre 2018 y 2021 (ilustración de Natalia Villavicencio, utilizada con su permiso).

Figura 3. Género atribuido al AC para manuscritos aceptados entre 2018 y 2021 (ilustración de Natalia Villavicencio, utilizada con su permiso).

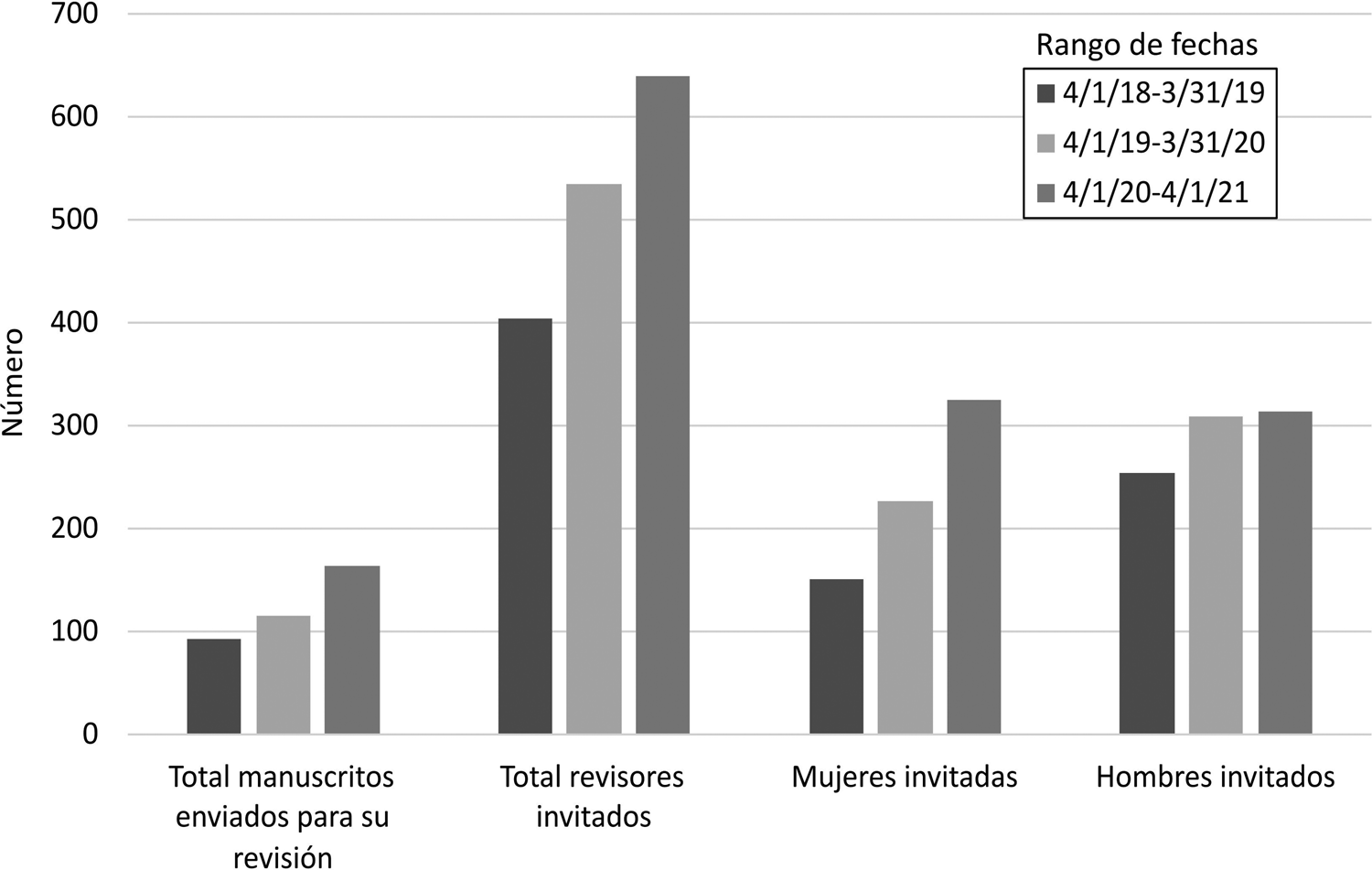

Los revisores son fundamentales para el éxito de una revista con revisión de pares como LAQ. Servir como revisor es una de las actividades académicas o profesionales peor recompensados. Hemos sabido de revisores que necesitan más tiempo para completar una revisión o que se niegan a revisar debido a la pandemia. Es comprensible que la revisión tenga baja prioridad en tiempos de crisis, cuando las demandas y responsabilidades en competencia hacen que el tiempo sea un recurso aún más escaso (véase Deryugina et al. Reference Deryugina, Shurchkov and Stearns2021). Hemos tenido que invitar a más revisores durante el año de la pandemia, aunque también hemos tenido más envíos (Figura 4).

Figura 4. Invitaciones a los revisores (ilustración de Natalia Villavicencio, utilizada con su permiso).

La disposición de las personas invitadas a comprometerse a revisar para nosotros ha descendido ligeramente, pero no muestra un descenso pronunciado como temíamos. En la Figura 5 se muestra como la disposición de las mujeres a revisar para la revista ha aumentado con el tiempo. En otras palabras, no sólo se ha invitado a más mujeres a revisar, sino que han aceptado hacerlo con más frecuencia. La aceptación de los hombres a las invitaciones de revisión ha disminuido con el tiempo, pero se ha mantenido estable en los últimos dos años.

Figura 5. Comparación de las tasas de aceptación de revisores masculinos y femeninos (ilustración de Natalia Villavicencio, utilizada con su permiso).

Nos alegramos de que los envíos a la revista se hayan mantenido firmes y, de hecho, hayan aumentado durante el año de la pandemia. Mujeres y hombres nos están enviando sus investigaciones originales, por lo que estamos muy agradecidos. Estas cifras, sin embargo, no nos dicen nada sobre cuántas mujeres u hombres no enviaron artículos que, de otro modo, podrían haberlo hecho.

La información que hemos extraído del EM ofrece una instantánea de un año de pandemia. Las consecuencias a largo plazo de los trastornos de la pandemia en la vida cotidiana y académica todavía se están desarrollando. Probablemente la mayoría de los envíos que hemos recibido en el primer año como editores se basan en investigaciones que tuvieron lugar antes de 2020. Como editores de una revista cuya misión es publicar investigaciones originales en arqueología, historia del arte, etnohistoria y campos afines, nos preocupa cómo la suspensión de las temporadas de campo y el cierre de los laboratorios de investigación, oficinas, museos y bibliotecas pueden afectar a la producción de conocimiento académico en el futuro.

A medida que los académicos retoman los hilos de sus investigaciones, alentamos la presentación de manuscritos reflexivos y teóricos que apunten a revisar, mejorar y ampliar los paradigmas explicativos tradicionales sobre las diferentes formaciones sociales que se dieron en las Américas antes de la invasión europea en el siglo dieciséis. En definitiva, imaginar la integración de investigadores de los hemisferios norte y sur trabajando juntos para construir una praxis más inclusiva y menos colonialista de la disciplina.

We became coeditors of Latin American Antiquity (LAQ) on April 24, 2020, although we had been working with and learning from the previous coeditors, Geoffrey Braswell and María Gutiérrez, since February of that year. Our editorship thus coincides with the spread of the coronavirus. Institutions closed their doors and asked employees to work remotely to help slow its spread. People found themselves unable to travel to their offices and research sites, access equipment necessary for analyses, or present their research at conferences. Those who teach found themselves changing almost immediately in mid-March to remote teaching, and those with children grappled with the closure of childcare facilities and schools as their children became remote learners—with not enough equipment or internet capacity to plug in all members of the household. Worries about infection, the loss of interaction with friends and relatives, fear of losing one's job or even one's life, coping with the digital divide, and many other concerns all combined to create one of the most difficult and stressful years many of us have ever experienced. Writing this editorial in early April 2021, it is a good moment to look at how LAQ authors and reviewers have been affected by the stresses and strains of the pandemic.

During the first week of March 2019, Calogero traveled to Olavarria, a cattle-raising town located southwest of Buenos Aires and home to former coeditor María Gutiérrez, to learn how to operate the editorial platform of LAQ, as they drank liters of yerba mate. This was his last trip out of Chile and the last bife de chorizo he ate before being completely confined in Arica. Meanwhile, Julia was attempting to Zoom with Geoffrey Braswell and trainers from Cambridge University Press, discovering just how terrible her home internet service in rural Pennsylvania really was. Julia was on sabbatical with all travel plans canceled. Natalia Villavicencio, our editorial assistant based in Santiago, was juggling LAQ's demands and her duties as a postdoc amid prohibitions on fieldwork and lab access.

As was to be anticipated, we inherited some manuscripts that were at various stages in the submission process. Comparing 2020 to the two previous years, LAQ experienced a steady increase in the number of submissions (Figure 1). During 2020, 82% of the submissions arrived between April 1 and December 31, coinciding with the period when much of humanity was in seclusion. The number of submissions for the first three months of 2021 (41) is greater than what was received in the first quarter of 2020 (27). Moving these submissions through the process from initial receipt to final decision has been affected by the fact that all concerned—editors, reviewers, and authors—were dealing at the same time with the pandemic's stresses and strains. We appreciate everyone's patience as we move this large number of manuscripts through the pipeline and reach final editorial decisions.

Figure 1. Manuscripts received from 2018 to 2021 (illustration by Natalia Villavicencio and used with permission).

From the outset, we were concerned by the reports that women academics and researchers were particularly hard hit by the consequences of the pandemic (see, for example, Flaherty Reference Flaherty2020; Fulweiler et al. Reference Fulweiler, Davies, Biddle, Burgin, Cooperdock, Hanley, Kenkel, Marcarelli, Matassa, Mayo, Santiago-Vàzquez, Traylor-Knowles and Ziegler2021; Gewin Reference Gewin2020; Squazzoni Reference Squazzoni, Bravo, Grimaldo, García-Costa, Farjam and Mehman2020; Viglione Reference Viglione2020). These analyses mostly examined the number of contributions to preprint servers and to platforms for registered reports by women (as determined by name) working in STEM fields. That women in academia are losing research time during the pandemic is confirmed by a report from the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research (Deryugina et al. Reference Deryugina, Shurchkov and Stearns2021). The survey results reveal that women academics with children have lost the most research time but that parents as a whole lost more generally than those without children in the home. Supporting this research is this comment made by a young academic from the Universidad de Tarapacá and the mother of two children: “Aparte de las preocupaciones físicas que demanda la vida de todos los seres que viven dentro del hogar, las mujeres tenemos una carga emocional que no es reemplazada con nada, ni por nadie” (Apart from the physical worries that everyone living at home experiences, women have an emotional burden that cannot be replaced by anything or anyone).

Given that LAQ is a peer-reviewed journal that does not publish preprints, the time between submission and publication is too long to effectively address the effects of the pandemic. As editors, we have access to somewhat more timely data through the online submission system, Editorial Manager (EM), but EM does not include information on an individual's gender identity. Therefore, we were required, like the researchers in the articles cited earlier, to assign a presumed gender to our authors and reviewers. We did so through a combination of name, web biographies, and personal knowledge. We realize that this approach is not ideal because it reduces a complex set of identities to a gender binary. Nevertheless, we think the attempt to evaluate differences in the gender of our authors and reviewers is worthwhile and adds to the growing literature on women and men as researchers and scholars. Some of the information presented here is included in the study by Herr and colleagues (Reference Herr, Gamble, Hendon, Santoro and Rieth2021). We used these data plus additional information extracted from EM to look more closely at the time before and after the COVID-19 shutdown. To simplify searching, we defined the period before COVID-19 as before April 1, 2020, and we chose to start our comparisons with the year 2018. Those individuals whose perceived gender could not be determined are not included in our data.

Most of the submissions to LAQ have two or more authors: 67% in 2018, 81% in 2019, 82% in 2020, and 76% in 2021 (through April 1). We chose to use the gender of the corresponding author (CA) for our comparison. The CA is the lead author in more than 90% of the multiauthored submissions. Even when the CA is not the lead author, the EM database ties each submission to his or her name, making the CA the primary point of contact. The CA receives the peer reviews and editorial comments and must respond to all queries regarding copyediting, image quality, missing information, and so on. As part of Cambridge University Press's expanding push toward open access publishing, it is the CA's institutional affiliation that determines whether the manuscript is covered by one of the press's Read and Publish agreements. Once an article is published, the CA is the primary point of contact for journal readers.

During the first two years of our comparison, more men than women were CAs (Figure 2). In 2020, women achieved parity with men, with a very slight dip in 2021. Acceptance rates have also shifted to a more equal representation of authorship by women and men (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Perceived gender of CA for manuscripts submitted from 2018 to 2021 (illustration by Natalia Villavicencio and used with permission).

Figure 3. Perceived gender of CA for manuscripts accepted between 2018 and 2020 (illustration by Natalia Villavicencio and used with permission).

Reviewers are critical to the success of a peer-reviewed journal such as LAQ, yet serving as a reviewer is one of the most poorly rewarded types of scholarly or professional work. It is understandable that reviewing would be a low priority in a time of crisis like the pandemic, when competing demands and responsibilities make time an even scarcer resource than usual (see Deryungina et al. Reference Deryugina, Shurchkov and Stearns2021). Unsurprisingly, we heard from reviewers who needed more time to complete a review or who declined to review an article because of the pandemic. We have had to invite more reviewers during the pandemic year, although we have also had more submissions (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Reviewer invitations (illustration by Natalia Villavicencio and used with permission).

The willingness of those invited to commit to reviewing for us has gone down slightly but does not show the steep decline that we feared might be the case. As shown in Figure 5, women's willingness to review for the journal has increased over time. In other words, not only have more women been invited to review but they also have agreed to do so more often. Men's acceptance of reviewer invitations has declined over time but has held steady over the past two years.

Figure 5. Comparison of male and female reviewer acceptance rates (illustration by Natalia Villavicencio and used with permission).

We are happy that submissions to the journal have remained strong and have in fact increased during the pandemic year. Women and men are sending us their original research, for which we are very grateful. These numbers, however, do not tell us anything about how many women or men did not submit articles who might otherwise have done so in a less stressful time.

The information we extracted from EM provides a snapshot of one plague year. The long-term consequences of the pandemic's disruptions of daily and scholarly life are still unfolding. It seems likely that most of the submissions we received in our first year as editors are based on research that took place before 2020. As editors of a journal whose mission is to publish original research in archaeology, art history, ethnohistory, and related fields, we are concerned with how the cancellation of field seasons and the closure of research labs, offices, museums, and libraries may affect the production of scholarly knowledge in the future.

As scholars pick up the threads of their research, we encourage the submission of reflective and theoretical manuscripts aiming to revise, improve, and expand the traditional explanatory paradigms of the different social formations that occurred in the Americas before the European invasion in the sixteenth century. In short, we imagine the integration of researchers from the Northern and Southern Hemispheres working together to build a more inclusive and less colonialist praxis of the discipline.