1. Introduction

This article is an overview of selected research on the learning, teaching, and assessment of English and other foreign languages studied in Sweden at different levels of education.Footnote 1 We aim at providing a critical review of local Swedish research in the field of foreign language education to an international readership. However, as pointed out by Aronin and Spolsky (Reference Aronin and Spolsky2010), there is no straightforward definition of local research. Considering the “unbreakable connection between local and global” (p. 298), they outlined some factors that complicate the task of distinguishing the two, the most important probably being researcher mobility and the expectations to publish in international channels of publication. Considering this, our criteria of inclusion have been the following.

Firstly, the reviewed texts were published between 2012 and 2021. A previous review of applied linguistics research with a focus on foreign language learning and teaching in Finland and Sweden covering the years 2006–2011 was authored by Ringbom (Reference Ringbom2012) and published in Language Teaching. We start our critical review of research carried out in Sweden where Ringbom stopped.

Secondly, the research regards topics related to the overarching theme of the review, namely, the learning, teaching, and assessment of foreign languages studied in Sweden. Hence, the work reviewed is concerned with issues typically relevant to the Swedish setting. It is our conviction that such topics are of relevance and interest to scholars, including teachers, also outside Sweden, and sometimes even transferable to those contexts, both from a theoretical and a practice-oriented point of view.

Thirdly, predominantly studies drawing on data collected in Sweden have been reviewed. However, a small number of studies on Swedish speaking learners studying abroad have also been included. Again, we think that a strictly local perspective would not be fruitful, considering that study abroad is today an integral part of many educational programs (Forsberg Lundell & Bartning, Reference Forsberg Lundell and Bartning2015).

A fourth criterion, that the text was published in Sweden, was striven for, but not possible to adhere to entirely, since excluding all work published outside Sweden would give a distorted and incomplete picture of the ongoing research in the country (cf. Ringbom, Reference Ringbom2012, p. 490). Several scholars active in Sweden publish both locally and internationally, especially those who have contributed substantially to research on language education in Sweden during the reviewed period. Therefore, international publications and talks will also occasionally be mentioned, although not technically reviewed. Regarding conference papers, we include only those published in Sweden. How research publications were identified will be further described in Section 3.

In summary, the review will cover selected research conducted, presented, and published in Sweden from 2012 to 2021, but will also include work published outside Sweden if reporting on projects carried out in the Swedish context.

The work covered in the review will be drawn from Swedish licentiate,Footnote 2 Ph.D., postdoctoral, and senior researchers’ projects. The corpus comprises an array of output; for example, published books (including dissertations), research reports, chapters in edited volumes, papers in journals, and conference proceedings. The targeted foreign languages are English, French, German, and Spanish, and a smaller number of additional languages, in proportion to how much research has been carried out during the period under review. Regarding the overarching strands of learning, teaching, and assessment, we are aware that they are umbrella terms with no clear-cut boundaries, and particular studies may therefore fit into more than one of these categories.

The article is structured into four parts. In Section 2, we offer a presentation of the language situation in Sweden, providing a brief historical background. We highlight some salient sociolinguistic traits and relevant educational and language policy matters, focusing on the study of foreign languages. In Section 3, we cover each of the three strands in turn. The article ends in Section 4 with a discussion of some trends emerging from the review in Section 3.

2. Contextualizing Swedish foreign language education

2.1 The language situation in Sweden

2.1.1 Swedish and other mother tongues spoken in Sweden

Before zooming in on foreign language education in Sweden, it is appropriate to provide a brief overview of the Swedish language situation. In 2009, the Parliament adopted the Language Act (Sveriges riksdag, 2009), stipulating that Swedish formally be the principal language. This means that Swedish is the common societal language and that everyone living in Sweden is entitled to information in Swedish and can expect to be able to use Swedish in all parts of society.

Even though Sweden has been linguistically relatively homogeneous for a long time, there have always existed other languages alongside Swedish. Finland and Sweden were one country for 800 years, until 1809,Footnote 3 and during that time, Finnish became (and still is) a significant minority language.Footnote 4 Since Finland became independent, Finnish-speakers have continuously immigrated to Sweden. Sweden has always had immigration, though limited, mainly from countries in northern Europe. However, from the early post-Second World War period, immigration to Sweden increased continuously. Today, almost one-fifth of the population was born abroad, according to Statistics Sweden (Statistikmyndigheten, 2022). People have immigrated to Sweden from practically all countries of the world, but this fact obviously does not reveal how many languages are represented among them (Parkvall, Reference Parkvall2019). According to an estimate from the Institute for Language and Folklore (Institutet för språk och folkminnen, 2022), approximately 200 languages are spoken in Sweden today.

2.1.2 English – a foreign language or a second language?

As in several other countries, the status of English in Sweden is in transition (for the case of the neighbouring country Norway, see Rindal, Reference Rindal, Rindal and Brevik2019). Although officially a foreign language, English in Sweden has in practice many traits that make it more similar to a second language (L2), considering how, when, and where it is used (Hult, Reference Hult2012; Hyltenstam, Reference Hyltenstam2004; Hyltenstam & Österberg, Reference Hyltenstam and Österberg2010) and its status is continuously negotiated (Hult, Reference Hult2012). Moreover, as discussed by Aronin and Yelenevskaya (Reference Aronin and Yelenevskaya2022), the terms English as a foreign language (EFL) and English as a second language (ESL) are dynamic and can co-exist as performance varieties at the individual as well as the societal level. In fact, we have in this review attempted to use the terms L2 and FL (foreign language) with some parsimony, aware of the fuzzy boundaries between them. In analogy to this, and especially in relation to English, but also considering speakers of Swedish as a L2 and heritage language speakers, the notion of the native speaker and the label L1 (first language) are acknowledged as problematic. Nevertheless, both terms will appear in our review on several occasions because of their role in some of the reviewed projects.

Proficiency-wise, according to the Eurobarometer 386 (European Commission, 2012a), Swedes (aged 15 years and upwards) are confident regarding their competences in English. As many as 86% of the Swedes who participated in the survey deemed themselves capable of having a conversation in English. The corresponding figures for the other European respondents were on average 54%. The dominant position of English among Swedish youth was further confirmed in the First European survey on language competences (European Commission, 2012b), where Swedish students were at the top of the league when their reading and listening skills were tested in English but at the bottom when tested in Spanish (see section 3.3.1 for more details).

In light of the generally very positive attitudes amongst Swedes towards learning and using English, it is interesting to note the somewhat more sceptical attitudes held towards learning additional languages. However, when comparing the results from the two subsequent Eurobarometers conducted by the European Commission (2006, 2012a), some shifts can be noted in Swedes’ views on the relevance of speaking more than one foreign language. When asked whether it is important for EU citizens to learn two languages alongside the mother tongue, only 27% of the Swedes answered positively in 2006. In the survey conducted in 2012 this attitude had changed and 45% of the Swedes totally agreed with the statement that everyone in the EU should be able to speak at least two languages in addition to their mother tongue. The potential reasons behind this shift remain to be investigated.

2.2. Foreign language studies in compulsory and upper secondary school

2.2.1 English in compulsory school

English has a very strong position in Swedish compulsory school. In order to continue studies at upper secondary school, a grade of E (= Pass) is required in at least eight subjects, necessarily including the subjects English, Mathematics, and Swedish/Swedish as a second language (Skolverket, 2022a). Students start studying English no later than school year 3, aged 9, and continue until they finish compulsory school in Year 9, aged 15–16.

Grades are awarded for all subjects, including English, for the first time at the end of Year 6. In Year 6 and Year 9, all students take National tests in English. The Parliament decided in 2018 that teachers should pay special attention to the results in the National tests when awarding grades owing to observed discrepancies between awarded grades and National test results.

2.2.2 Other foreign languages in compulsory school

The introduction of nine-year compulsory education in 1962 was part of the community development that shaped post-war Sweden. One challenge for the new compulsory school was to establish criteria for eligibility for further studies in upper secondary school. Whereas English was made compulsory for all students, German or French became optional, but was required for advancing to upper secondary school. This requirement was abandoned in 1969, the second foreign language remaining an optional subject in compulsory school and being so still today. In 1994, some changes took place. Spanish was introduced in the so-called Language choice, and, since then, a school organizerFootnote 5 must offer at least two out of the languages French, German, and Spanish. Since 1994, it is also possible for students to study a third foreign language within the framework of the Student's Choice (Tholin & Lindqvist, Reference Tholin and Lindqvist2009). This is illustrated in Figure 1. Very few students seize this opportunity, however, and in 2019 only 1,372 (c.1%) students did so in Year 9 according to the Swedish National Agency for Education (NAE) (Skolverket, 2022b). (For thorough descriptions and analyses of the history and status of foreign languages other than English in Swedish compulsory school, see Bardel et al., Reference Bardel, Erickson and Österberg2019; Granfeldt, Reference Granfeldt2021; Tholin, Reference Tholin2019).

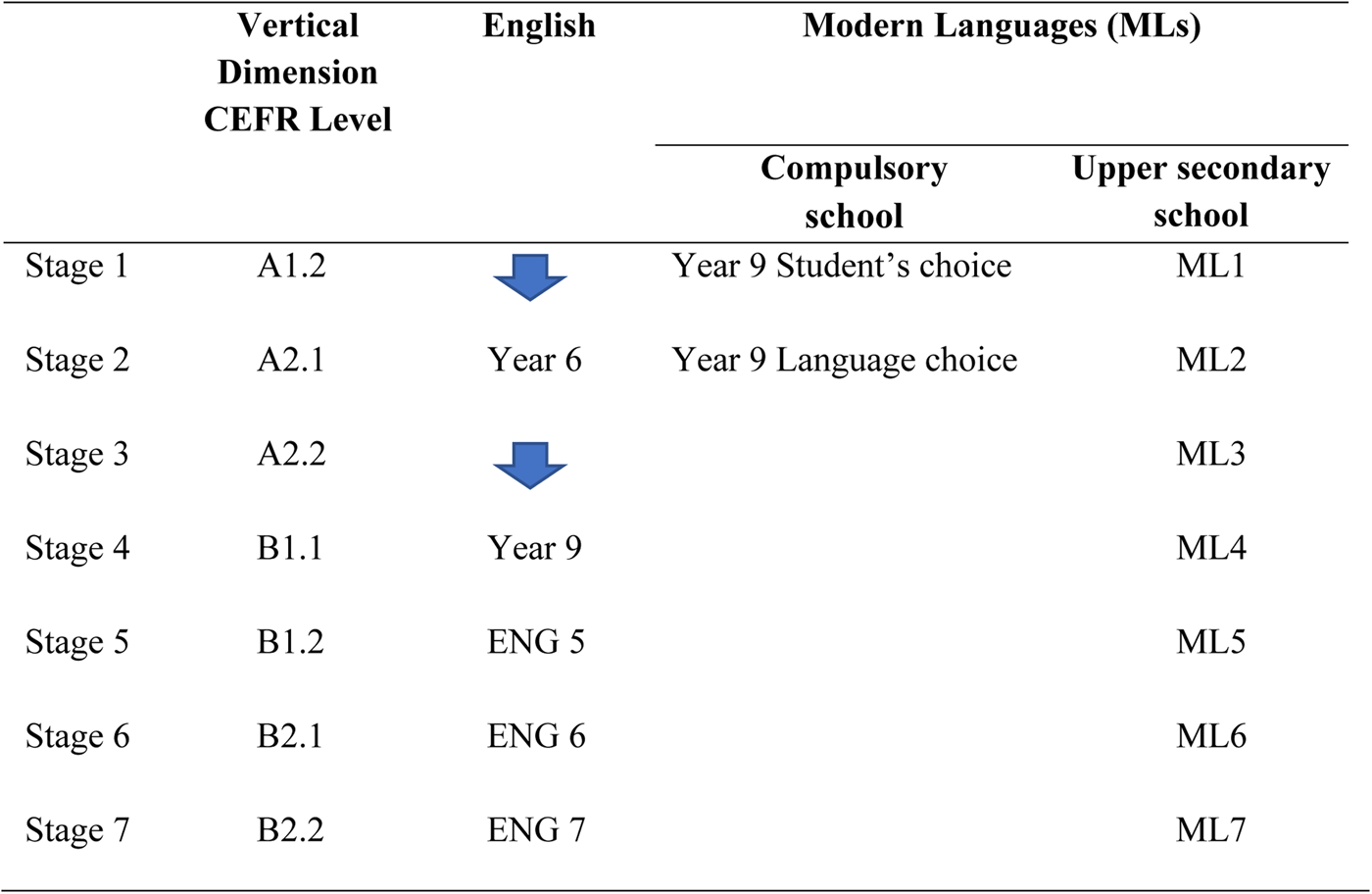

Figure 1. The structure for English and modern languages in relation to CEFR levels (adapted from Skolverket, 2021).

Note: The Swedish syllabus for compulsory school contains knowledge requirements at the end of Years 3, 6, and 9. For English, as opposed to all other stages, Stages 1 and 3 are not described in the syllabus. This is illustrated by the arrows in the figure. (Stage 3 is, however, described in assessment materials for mapping proficiency levels among newly arrived students [Skolverket, 2023]).

Between 1996 and 2011, approximately 80% of the students in Year 7 started studying a second foreign language (Tholin, Reference Tholin2019), or a so-called modern language (henceforth ML), which is the official term for the school subject in question. Today, this figure has risen to 86–88%. The overall percentage of drop-outs has been relatively constant over the years. In Year 9, approximately 70–72% of the students continued with French, German, and Spanish. About 4–5% of the students do not achieve the minimum level specified in the syllabus for the ML subject and receive no grade after four years of study (Granfeldt et al., Reference Granfeldt, Sayehli and Ågren2020).

In 1994–2014, there was a dramatic shift concerning MLs. Spanish grew in popularity and became the most studied language in 2006, continuing to expand until 2014. Since 2014, the proportion of students of Spanish has remained relatively stable. French and German faced a sharp decline during the period 2000–2008, but German has seen a small increase in the last couple of years, with 58% of the students choosing Spanish, 23% German, and 19% French for the academic year of 2019/2020. These figures have seen little fluctuation over the last ten years. In comparison, other languages were studied by very few: 404 studied Chinese, 266 Finnish, 138 Italian, and 128 Sami (out of approximately 112,000) in 2019/2020, according to statistics retrieved from the NAE (Skolverket, 2022c).

Furthermore, the compulsory school ordinance states that as an alternative to a ML, other languages can be chosen in compulsory school within the Language choice: Mother tongue (when other than Swedish), Swedish, Swedish as a second language, English, or Swedish Sign Language for the hearing (Skolförordning, 2011: 185, Chapter 9, § 6).

2.2.3 The stage model for the teaching and learning of foreign languages

Foreign languages in the compulsory school system and at upper secondary level, both English and MLs, are structured along seven stages, in alignment with the levels in The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001, 2020). This is visualized in Figure 1. The alignment means that a specified CEFR level should be reached as a minimum at the end of a stage level of study. It should be noted, though, that an extensive and thorough empirical alignment study has not yet been carried out.

For example, in English, a CEFR level of B1.2 should be met at the end of the course English 5 in Year 10 (the first year of upper secondary school). In English, Stages 1 to 4 apply to compulsory school, whereas Stages 5 to 7 apply to upper secondary school.

Students can choose a ML in the Language choice in Year 6 and reach Stage 2 at the end of Year 9. They can then continue with Stage 3 in upper secondary school. As part of the Student's choice, they can choose to study a second ML and reach Stage 1 in Year 9 and then go on with Stage 2 in upper secondary school. Students can also start with a new ML at Stage 1 in upper secondary school (Skolverket, 2021).

2.2.4 English in upper secondary school

Swedish upper secondary school offers two types of programs, higher education preparatory and vocational. For English, students reach Stage 4 by the end of compulsory school, whereas Stage 5 is reached in the first year of upper secondary school and is mandatory in all programs. Stage 6 is mandatory in some programs and optional in others. Stage 7 is optional, and approximately two-thirds of all students in higher education preparatory programs choose to study this course. In vocational programs, however, as few as 3–4% of the students choose Stage 7 (Skolverket, 2018).

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), defined as learning through the teaching of a subject in a language other than Swedish, is a relatively common approach in Swedish upper secondary schools. Sylvén (Reference Sylvén2019) reported that 27% of upper secondary schools use some type of CLIL (see also Yoxsimer Paulsrud, Reference Yoxsimer Paulsrud2014). However, no statistics are available for how many students participate in this type of teaching, and to what extent any language other than English is the language of instruction. It is safe to assume, though, that English is used in the great majority of cases.

2.2.5 Other foreign languages in upper secondary school

Studies in a second foreign language, one or two stages, are required in four out of six higher education preparatory programs. It is, however, optional for students in all other programs to study MLs. The school organizer must offer French, German, and Spanish both to beginners and from Stage 3 for those who have already studied the language in compulsory school. The school organizer should also strive to offer additional languages (Sveriges riksdag, 2010), although nearly nine out of ten courses offered in MLs are in French, German, and Spanish. Italian is the most common additional language, followed by Arabic, Danish, Japanese, and Russian (Statistikmyndigheten, 2018).

Over the past eight years, the proportion who study a second foreign language in upper secondary school has increased slightly every year. Of those who graduated in the academic year 2017/2018, 55% had taken at least one course in a second foreign language during their time in upper secondary school, whereas 5% had studied two or more languages (Statistikmyndigheten, 2018).

Most students at upper secondary level take Stage 3 in MLs, but for languages rarely studied in compulsory school (e.g., Chinese, Danish, Italian, Japanese, Russian) most students take only Stage 1. In 2007, a system of extra credit points (Meritpoäng) was introduced. This implies that students who reach Stage 3, 4, or 5 in a second foreign language, or Stage 7 in English, can gain extra credit points, which will improve their chances of being accepted to university studies. Less than 100 students per year reach Stage 7 in ML (Statistikmyndigheten, 2018).

2.3 Languages in adult education and higher education

2.3.1 Languages in adult education

Adults who have not finished primary or secondary education, and students who have not achieved the grades required for higher education, are offered adult education at municipality level, kommunal vuxenutbildning (‘municipal adult education’), in short, Komvux. Komvux offers the same courses as secondary school.

Another important part of adult education in Sweden is the concept of ‘study circles’. Study circles are offered by national educational associations and the purpose for the participants is to informally deepen their knowledge in a subject or a knowledge area. The participants do not receive formal grades or degrees. According to The Swedish Agency for Public Management (Statskontoret, 2018), approximately 21,000 people studied languages in study circles in 2016.

2.3.2 Languages in Swedish higher education

2.3.2.1 English as a university subject and as lingua franca

For courses and study programs at bachelor's level, the general entry requirement includes at least a grade E in Swedish/Swedish as a second language, Mathematics, and English. As in school, English has a more prominent role than other languages also at university level. In a report from a survey conducted at Stockholm University, Bolton and Kuteeva (Reference Bolton and Kuteeva2012) stated that in the sciences English is used more frequently than in the humanities and social sciences, where English is typically used as an additional language to Swedish.

An overwhelmingly large part of Swedish scientific publishing is in English, and two recent dissertations highlight the special position of English in academia. Firstly, Salö (Reference Salö2016) showed that most scientific texts at university are written in English. Swedish is used for scientific purposes to some extent, especially for popular science, but also in scientific reports, mainly in the humanities. In recent years, however, English has been boosted by the current research policy in Sweden, recognizing its role when it comes to impact at the international research front.

Secondly, in a study by Jämsvi (Reference Jämsvi2020), comparisons were made between language policies that governed higher education institutions during the 1970s and those of today, and the author observed a shift in how multilingualism is viewed and valued in Sweden. In the 1970s, there was an ambition and a notion of multilingualism as something relevant and valuable for higher education. In the internationalization study presented to the Government in 1974, it was suggested that Swedes need to know a number of world languages, such as Chinese, French, German, and Russian. In the twenty-first century, however, that mindset no longer exists. Instead, Jämsvi found that current policy documents are permeated by the view that English is synonymous with internationalization. She also noticed an ideological shift, where solidarity as a linchpin had lost ground to market forces, more specifically economic interests, in all areas of society – something that gives English an edge.

2.3.2.2 Foreign language studies in higher education

For several years, there has been a declining interest in Sweden for studies of foreign languages at university level. In 2016, The association of Swedish higher education institutions (SUHF) appointed a working group to review the status of languages in higher education and make recommendations for the future (SUHF, 2017). The report highlighted a need for a national language strategy that identifies the direction for which specific initiatives and assignments are necessary. The report also shows the extent to which languages have been discontinued at universities during the time span 2008–2016. French has been cut at six universities, English at five, Russian at four, and Finnish, German, Greek, Italian, and Spanish have been cut at three universities, to give some examples.

2.3.3 Pre- and in-service training of foreign language teachers

Swedish teacher education has for many years had great difficulty attracting applicants to languages other than English. The Swedish National Audit Office published a report on this issue in 2014 (Riksrevisionen, 2014). It showed that many universities were suspending their language teacher education owing to a low influx of students, at the same time as many language teachers in Sweden were approaching retirement. Eighty percent of the municipalities in the report stated that they found it difficult to recruit new language teachers. This is corroborated in a recent report from the Swedish higher education authority stating that there is a profound lack of language teachers (Universitetskanslerämbetet, 2020).

The Language Teachers’ Association (Språklärarnas riksförbund) was founded in 1938. Currently there are just over 1,000 members. The Association arranges a ‘language day’ every year with lectures by researchers as well as professional teachers. The association's journal Lingua is issued four times per year. A review of Lingua 2011–2020 shows that it publishes many articles in the popular science genre. Researchers often summarize their doctoral dissertations. It also happens that researchers report smaller projects or publish partial results from their research. Not only Swedish researchers but also international researchers are often invited to write in the journal.

3. Research on learning, teaching, and assessing English and other foreign languages

This overview presents a selection of research on learning, teaching, and assessment of English and other foreign languages. Before moving on to the overview, however, a few words about the overall conditions for conducting educational research in the Swedish context are appropriate. During the years covered by this overview, there has been a necessary increase in the allocation of funding to practice-based research. The government has in some rounds allocated funds to the Swedish Research Council for graduate schools in educational science for in-service schoolteachers. Furthermore, in 2015, the government established the Swedish Institute for Educational Research (Skolforskningsinstitutet) to fund high-quality practice-based research. Since 2017, the government has also funded the national network ULF (acronym for Utveckling, Lärande, Forskning [‘development, learning, research’]), involving universities aiming at developing and testing sustainable models for collaboration between academia and schools in terms of research, school activities, and teacher education (Olsson & Cederlund, Reference Olsson and Cederlund2020). For the field of language education, the above attempts to promote educational research have facilitated a number of research studies involving schoolteachers and teacher educators.

The overview focuses on linguistic and educational aspects, including language policy. For reasons of space, some aspects of language education are by necessity excluded. For example, research on intercultural competence, and the role of literature and other cultural aspects in language education, are not included; see, for example, Lutas (Reference Lutas, Persson and Johansson2014) and Marx Åberg (Reference Marx Åberg2014, Reference Marx Åberg and Larsson Eriksson2016) for such studies.

Looking back at Ringbom (Reference Ringbom2012), some research themes highlighted in his review as significant for the Swedish context are relevant to delve further into. These are, for example, interlanguage grammar development, cross-linguistic influence (CLI), language processing, and multilingual language learning, where much research has continued to be carried out during the last ten years, not least in the area of third language (L3) learning. CLIL and out-of-school learning of English are other fields that have emerged or been further developed in the Swedish context, as are motivation and attitudes toward foreign language learning, learning and teaching vocabulary and phraseology, writing skills, and assessment of language proficiency, especially spoken skills. These are the main themes covered in this review.

As already noted, the boundaries between learning, teaching, and assessment are not set in stone – on the contrary, the connections between them are central in language education. For the sake of organizing the work reviewed, however, we have categorized it into either of these three overarching areas, its focus placed mainly on either the learner (the developing interlanguage, language processing and representation, skills, motivation, and attitudes), or the teacher (teaching and assessment practices and processes, including grading, and validation of tests). As mentioned, we have given prominence to work published in Sweden in order to make such research accessible to an international readership. However, it is inevitable that international publications will also be mentioned for the purpose of contextualizing the reviewed work, and, not least, since Swedish journals concerned with foreign language education are extremely few, as discussed below. Otherwise, justice would not be given to all research of relevance for the review and the comprehensive picture would be clouded.

Aiming at including all theses, monographs, edited volumes, single book chapters, journal articles, conference papers, and reports of relevance for foreign language learning, teaching, and assessment and their subthemes, we examined book series and other publications issued from language and linguistics departments and departments of educational research. This resulted in an extensive list of theses including those written in Swedish, English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish (a thesis from a language department in Sweden is normally written in the language of study). The list was compiled by searching online at the web sites of the Swedish universities that offer Ph.D. education in English, other languages, language education, or other educational research. The theses from most of these universities are stored in the repository DiVA, while Gothenburg store theirs in GUPEA, and Lund in Lund University Research Portal.

We also examined the books and articles edited by publishers and journals that publish research reports on language education in the Swedish context. There are a few commercial publishing houses that target teachers, students, and researchers in language education. Two prominent publishers of academic work on English and other foreign languages are Studentlitteratur and Natur & Kultur. Hence, the publications from these publishers during 2012–2021 have been examined.

As for Swedish journals focusing on foreign languages, the only scientific journal is Moderna språk (‘Modern languages’), a Swedish peer-reviewed journal, which publishes articles in English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish on linguistics, literature, and area studies, often with an educational focus. From its inception back in 1906 to 2008, Moderna språk was published yearly in a printed version, but from 2009 it has been published as a web-based journal (https://publicera.kb.se/mosp).

Lingua, the online journal of the Swedish language teachers’ association, hosts short articles on language learning, teaching, and assessment, language and culture, and summaries of an informative nature of current research (https://www.spraklararna.se/lingua).

Educare, a peer-reviewed journal published at Malmö University, is a national and Nordic forum for educational science, targeting researchers, students and teachers (https://ojs.mau.se/index.php/educare/index). Another Swedish journal covered is Utbildning & Demokrati (https://journals.oru.se/uod).

Considering the small number of Swedish journals within the field, we have also scrutinized three journals published outside Sweden but in the Nordic context, where Swedish language education research is sometimes published, Acta Didactica Norden (https://journals.uio.no/adnorden/about), Nordand (Nordisk tidsskrift for andrespråksforskning [Norwegian for: ‘Nordic journal of second language research’], https://www.idunn.no/nordand), and Nordic Journal of English Studies (NJES, https://njes-journal.com/). Acta Didactica Norden and Nordand accept manuscripts in Swedish.

We have also considered the proceedings from two regularly-occurring Swedish conferences, the Swedish Association of Applied Linguistics (Svenska föreningen för tillämpad språkvetenskap, ASLA), that is, the local conference of Association Internationale de Linguistique Appliquée, AILA, and the Swedish language teachers’ association (Språklärarnas Riksförbund, https://www.spraklararna.se/). The former is biannual, and the latter is arranged yearly for language teachers, with invited speakers.

3.1. Learning foreign languages in Sweden

In this section, we will review studies that focus mainly on the learning side of foreign language education, starting with research on grammar, then turning to vocabulary and phraseology, writing skills, and finally motivation, attitudes, and beliefs regarding English and MLs. These are the areas that we have identified as the most productive during the period reviewed, when it comes to the learner's perspective. One area where we find relatively few studies in the Swedish context is that of oral production and interaction in foreign languages (but see Aronsson, Reference Aronsson2020, on Spanish, and Selin, Reference Selin2014, on English classroom interaction). As for pronunciation, there are some international publications in the domain of French (Ågren & van de Weijer, Reference Ågren and van de Weijer2019) and Spanish (Aronsson, Reference Aronsson2014, Reference Aronsson2016, Reference Aronsson2020). Interestingly, the assessment of oral production and interaction seems to be a far more prolific field (see 3.3.2).

3.1.1 Learning grammar

Research into the learning of grammar, especially French, has a longstanding tradition above all at the universities of Lund and Stockholm (see e.g., Lindqvist & Bardel, Reference Lindqvist and Bardel2014, for a collection of studies). The study of grammar development in other languages has flourished as is evident in a number of theses during the covered period. These add to the knowledge base concerning less researched foreign languages and are therefore worth mentioning. For example, gender and number agreement in Italian was studied by Gudmundson (Reference Gudmundson2012) in a functionalist framework. Data were drawn from Swedish university students, and the Italian corpus of oral language Lessico di frequenza dell'italiano parlato (LIP) (De Mauro et al., Reference De Mauro, Mancini, Vedovelli and Voghera1993) was used as a reference corpus. The results pointed at the importance of frequency of use and formal regularity. Kuwano Lidén (Reference Kuwano Lidén2016) investigated spatial-deictic demonstratives in the interlanguage of Finnish- and Swedish-speaking learners of Japanese in relation to native speakers’ use in the three languages as well as teaching materials. The findings revealed some differences in the usage rate of demonstratives between the two learner groups, which were attributed both to the teaching materials and to the linguistic environment in which the learners resided.

The role played by the background languages (previously acquired, learnt or studied) when learning an L3 has gained attention by Swedish researchers in recent years (e.g., Bardel & Falk, Reference Bardel, Falk, Cabrelli, Rothman and Flynn2012), reflecting an international upsurge of L3 research. A Swedish anthology from 2016 gives an overview of the research field in the national context, focusing especially on grammar and vocabulary (Bardel et al., Reference Bardel, Falk and Lindqvist2016). The study of the role of background languages requires a meticulous methodology, and the first studies from the period vary in scientific rigor, but deserve attention, above all for their originality.Footnote 6

Sayehli (Reference Sayehli2013) explored German studied after English by learners with Swedish as L1 in lower secondary school. The focus of interest was the V2 rule, present in both Swedish and German, according to which the finite verb must appear in second position (Sw.: ‘Idag åt jag ett äpple’ [gloss: ‘Today ate I an apple’]). Since data did not indicate any positive transfer of the Swedish structure into German (the learners violated the V2 rule), Sayehli claimed that L3 learning follows certain universal developmental stages, independently of prior knowledge of other languages. A problematic aspect of the study is the role arguably exerted by English (L2) where the V2 rule does not apply.Footnote 7

Spanish as L3, specifically the development of tense and aspect in groups of upper secondary and university students, was investigated through error analysis in a thesis by Lopez Serrano (Reference Lopez Serrano2018). The author concluded that, apart from Swedish L1 influencing the use of imperfect, a number of linguistic factors such as prototypical associationsFootnote 8 played a major role for the learning process. Although the author pointed at hypothetical influences from Swedish L1, English and other FLs studied in compulsory school, the design of the study only allowed proper analyses of L1 influence.

While tense and aspect constitute a well-researched area in traditional L2 acquisition research, it is in fact fairly under-researched in the L3. However, an article-based thesis of Italian (see Vallerossa et al., Reference Vallerossa, Gudmundson, Bergström and Bardel2021) exploring the acquisition of tense and aspect by Swedish university students shows that learners draw on previously acquired languages, both L1 and L2. Data gathered through several tests indicate an intricate interplay of linguistic typology, language proficiency, and prototypicality, when learning aspectual contrasts.

3.1.2 Learning vocabulary and phraseology – linguistic and psycholinguistic approaches

Research on vocabulary and phraseology learning has developed considerably during the period, notably concerning CLI; for international publications on CLI, see, for example, Wolter and Gyllstad (Reference Wolter and Gyllstad2011, Reference Wolter and Gyllstad2013), Lindqvist (Reference Lindqvist, Cabrelli Amaro, Flynn and Rothman2012), Bardel (Reference Bardel and Peukert2015), and Carrol et al. (Reference Carrol, Conklin and Gyllstad2016). Some of this work has generated national publications that will be reviewed in Sections 3.2 on teaching and 3.3 on assessment.

One line of research on vocabulary learning that has seen growing interest is formulaic language, with contributions through the doctoral dissertations of Moreno Teva (Reference Moreno Teva2012) and Arvidsson (Reference Arvidsson2019). A related concept, collocation, has also been targeted in a thesis by Wang (Reference Wang2013).

Moreno Teva (Reference Moreno Teva2012) showed positive effects of study abroad on the acquisition of multi-word expressions (MWEs). Recordings of oral interaction between Swedish university students who studied in Spain for 3–4 months and native speakers of Spanish were analysed. The learners developed a variety of MWEs, the number of such expressions increased, and their use became more similar to that of the native speakers, during the stay in Spain. Based on the results, the author also discussed how native and non-native speakers collaborated in interaction and how this influenced the native speakers’ use of MWEs.

Arvidsson's (Reference Arvidsson2019) thesis also dealt with the development of MWEs in the context of study abroad, but in French. Arvidsson operationalized idiomaticity as the knowledge and use of MWEs – for example, c'est ça and en fait. Across three studies, factors that promote idiomatic French during a term abroad were mapped out: varied target language (TL) contact and taking part in native speaker social networks were found to be positive factors in combination with the noticing of language forms, a favourable sense of self-efficacy, and strong learning motivation.

Wang (Reference Wang2013) investigated the use of verb + noun collocations such as make a decision in Swedish and Chinese learner English, using written learner corpora and an English TL corpus. Developmental patterns as well as the extent to which CLI occurs in the learners’ use of such collocations were explored, drawing on Sinclair's (Reference Sinclair1991) division of labour between ‘the idiom principle’ and ‘the open-choice principle’ and building on work by scholars like Nesselhauf (Reference Nesselhauf2005). Wang found that some combinatorially restricted word combinations seemed to be processed as holistic units, complemented by the use of less fixed and more transparent combinations. Proficiency level, register awareness, and psychotypology were found to interact with L1 influence.

Formulaic language in relation to communicative proficiency in advanced L2 learners’ use were explored also by several colleagues in the program High level proficiency in second language use (Hyltenstam et al., Reference Hyltenstam, Bartning and Fant2014). They found that L2 users of English, French, and Spanish overall employed fewer MWEs compared with native speaker controls, except in a telephone speaking task, where users of L2 English performed on par with native speakers, a result ascribed to the status of English in Sweden and the early start of instructed learning in Swedish schools. By and large, results also showed that the acquisition of MWEs tends to be more difficult than the acquisition of single words, something that calls for more and better coverage in instructed learning.

Other work packages of the program investigated aspects of the advanced lexicon of English, French, and Italian L2 learners, looking into different factors: word frequency, cognateness, and thematic vocabulary, when characterizing lexical complexity (see e.g., Bardel & Gudmundson, Reference Bardel, Gudmundson, Hyltenstam, Bartning and Fant2018; Erman et al., Reference Erman, Denke, Fant and Forsberg Lundell2015, Reference Erman, Forsberg Lundell, Lewis, Hyltenstam, Bartning and Fant2018). In relation to this program, and other projects, Lindqvist has carried out several studies on the learning of French vocabulary. Specifically, she has focused on the topics of vocabulary size in students of French in the Swedish compulsory school (Lindqvist, Reference Lindqvist2016–2017) and CLI in Swedish learners of French as a L3 (Lindqvist, Reference Lindqvist, Bardel, Falk and Lindqvist2016). French offers an interesting test case for recent theories of L3 learning, as do Romance languages generally. These are almost always studied after English, and in some cases also after another Romance language, which makes it possible to investigate the role that typology and other factors play in CLI. Recent studies of this field are Fuster and Neuser (Reference Fuster and Neuser2020) on intentional and unintentional transfer in adult multilingual learners of Catalan in Sweden, and Fuster and Neuser (Reference Fuster and Neuser2021) on the role of morphological similarity for transfer in multilingual learners of Spanish in Swedish upper secondary school.

Lexical diversity and sophistication were further explored by Berton (Reference Berton2020) in the written production of university students of Spanish. The study investigated the effect of overall language proficiency, receptive vocabulary knowledge, task complexity, and task type. Results suggested that overall proficiency influenced lexical richness only in a narrative task, and receptive vocabulary knowledge only in a decision-making task. The different cognitive load of different task types showed the most consistent effect in the study, as it was supported by all the measures of lexical richness and some measures of structural complexity.

Other work on lexical issues carried out at graduate level are the Ph.D. theses by Mežek (Reference Mežek2013), Smidfelt (Reference Smidfelt2019), Suhonen (Reference Suhonen2020), and the work by Gunnarsson (see below). Mežek's (Reference Mežek2013) work focused on English vocabulary in relation to reading in higher education, comprising a total of nearly 500 participants studying Biology and English. Students’ reading habits in both Swedish and English were investigated, considering additional factors such as academic biliteracy, reading speed, and motivation. English reading skills were found to vary considerably, reading speed and lacking vocabulary skills being the main challenges. Students performed on par with native speaker controls when given more time to read, but terminology was observed as an obstacle. Extensive and qualitative notetaking, featuring paraphrasing and translating, lead to remembering more from lectures. Mežek's thesis ends with a concise list of pedagogical implications and advice to students and faculty.

Smidfelt (Reference Smidfelt2019) and Suhonen (Reference Suhonen2020) offer interesting complementary work to current L3 research. Smidfelt's (Reference Smidfelt2019) compilation thesis focused on intercomprehension, that is, the capacity of learners to understand new languages thanks to their knowledge of closely related languages, at the first encounter with Italian as an additional language. Smidfelt (Reference Smidfelt2015) studied the role of guessing strategies for text and word comprehension, using introspection among upper secondary students. Other Romance languages were not used to the same extent as English or Swedish, which points to the role of high proficiency for strategic use of other languages. Furthermore, Smidfelt (Reference Smidfelt2018) and Smidfelt and van de Weijer (Reference Smidfelt and van de Weijer2019) investigated translation from Italian to Swedish, other Romance languages, or English. All known languages were to some extent activated and used for comprehension. Furthermore, the language into which the participants translated apparently had an impact on which background language was activated. When translating into another foreign language, Swedish was not activated and used to the same extent as the L2s.

Suhonen (Reference Suhonen2020) investigated the multilingual mental lexicon in terms of CLI amongst adult learners in situations where there are three languages involved. In a series of four controlled experiments, the author collected data from the very initial state of learning up to a high level of L3 proficiency (≥Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) C1). Whereas Experiments 1 and 2 focused on the initial state in L2 and L3, respectively, drawing on a Finnish-based pseudolanguage (‘Kontu’), Experiment 3 explored naturalistic learners of L3 Swedish, with L1 German and L2 English, in a longitudinal design. Experiment 4 comprised a cross-sectional replication of Experiment 3. In terms of main results, CLI was observed to be multidirectional, and no indications of independence from the previously acquired languages in the L3 lexical representations were found. Furthermore, cognitive control, working memory, and psychotypology were all factors found to affect learners’ behaviour.

In relation to processing and multilingualism, it is appropriate to mention Gunnarsson's licentiate thesis (Reference Gunnarsson, Housen, van de Weijer and Källkvist2015) investigating students’ languages of thought when writing in English. Students in lower secondary school with Swedish as an L1 or as an L2 participated. Participants (N = 131) responded to a language background questionnaire (Gunnarsson & Källkvist, Reference Gunnarsson, Källkvist, Bardel, Falk and Lindqvist2016; Gunnarsson et al., Reference Gunnarsson, Housen, van de Weijer and Källkvist2015). The majority of the participants used both English and Swedish as language of thought when writing in English. Students with two L1s used Swedish to a higher extent, and the other L1 to a limited extent. Six of the participants were also engaged in an introspective case study based on think-aloud protocols and retrospective interviews (Gunnarsson, Reference Gunnarsson2019). All of them declared that knowledge of multiple languages was beneficial when writing in English, especially when searching for vocabulary. This research provides insights into both the writing process and the field of teaching and learning of English in multilingual Swedish society.

3.1.3 Writing skills

Two lines of research can be identified in Swedish research on foreign language writing; one is interested in the writing process while the other can be said to focus more on the product. The latter is closely related to the research reported in section 3.1.1., as it explores interlanguage grammar (see e.g., Bernardini & Granfeldt, Reference Bernardini and Granfeldt2019, for a study on linguistic complexity in learner texts written in English, French, and Italian; or Rosén, Reference Rosén2020, for a comparative study of L1 influence in syntax and discourse in essays written in Sweden, China, and Belarus). In this section, we will mainly concentrate on the former line of research, where we find a greater number of studies published in channels that meet our selection criteria. Several of the studies are classroom oriented and as such they represent innovation in foreign language research in Sweden, considering that this kind of research was not highlighted in Ringbom's (Reference Ringbom2012) review. At the end of the section, we will return to some examples of research that focus on the written product, analysing it from a linguistic point of view.

Writing skills have been explored mainly with regard to English, both in compulsory and upper secondary school and also at university levels. Publications reporting research on other target languages are rare, but a thesis on German is also reviewed in this section. Apart from the internationally renowned work on notetaking by Siegel (e.g., Reference Siegel2019b), and some work reviewed in section 3.2.3 from the information and communication technology (ICT) perspective, we are not acquainted with any work on more casual or personal forms of composition. Rather, the work reviewed here focuses on formal aspects of language (e.g., grammar, spelling, vocabulary choice, discourse). Although some of them concern the effects of different teaching methods on students’ writing skills, most of the studies on the writing process involve the learning process and will therefore be reviewed in this section.

In a study by Karlsson (Reference Karlsson2020), 30 students in school year 4 composed three narrative texts in English with intervals of two weeks. The learners had received explicit teaching of the noun phrase (i.e., nouns with pre- and post-modifications) directly before composing the first and the second text, whereas no such instruction was offered before writing the third story. There were two control groups, Swedish L1-writers and English L2-writers, neither being offered treatment. Results showed that learners with explicit teaching improved their writing in several ways; for example, through an increase of text length and of number of post-modifying prepositional phrases. As the author acknowledges, the study suffers from limitations, especially concerning the small number of participants and the short period of data collection. Nevertheless, it is a step towards better understanding of the effects of explicit instruction in L2/FL writing.

Berggren (Reference Berggren2013, Reference Berggren2019) conducted two intervention studies on students peer reviewing each other's written texts in English, exploring potential learning benefits of giving feedback. Students in two EFL classrooms in Year 8 were engaged with three written tasks of different text genres. The findings suggest that reviewing texts and giving feedback can raise students’ genre and audience awareness and enhance their ability to self-assess and edit their own writing, highlighting the roles of learner involvement in assessment-as-learning activities. This is significant since previous research in the benefits of peer review has mainly been carried out at university and college levels.

Pålsson Gröndahl (Reference Pålsson Gröndahl, Bardel, Erickson, Granfeldt and Rosén2021) is a licentiate study of students’ understanding of teachers’ written feedback in English, with a focus on how learners make sense of and use feedback on their writing. Students in Years 8 and 9 participated in the study. After writing a draft, and upon received teacher feedback, they were asked to revise their text. The author identified feedback categories and analysed students’ understanding of the feedback thematically. The students were observed to understand approximately 50% of the teachers’ feedback points. The author concluded that feedback was seldom perceived as constructive by students and highlights the need to explicate why and when feedback is given, and what is focused on. She also emphasized the role of some features that seemed to be underdeveloped in the sample, namely a shared meta-language and consistency in teacher feedback notation.

Of relevance is also Knospe's (Reference Knospe2017) intervention study on writing in German. The thesis explored the effects of teaching focused on writing strategies and metacognitive reflections. Two groups in upper secondary school participated, one of which received special instruction. Additional data was collected from five individual writing sessions with seven students from the group with instruction (keystroke logging, screen-recording software and individual stimulated-recall interviews). Results showed that text quality improved only in those students who attended both the intervention and the individual writing sessions, suggesting that apart from practice being crucial for writing development, writing skills can be further enhanced by writing strategy instruction and metacognitive reflections.

While the hitherto reviewed writing studies concern students in compulsory and upper secondary school, there are some on writing in English at university level worth highlighting because of their originality. Larsson (Reference Larsson2012) investigated variation in English spelling. The study aimed at distinguishing whether British or American spelling was preferred, and if there was consistency in students’ choice of variety. This is interesting, because most previous studies on students’ preferred variety have focused on vocabulary and pronunciation. British English (BE) has traditionally served as a model in Sweden, as well as other European countries, but a shift in attitudes toward higher preference for American English (AE) has been noted (cf. 3.1.4). The results revealed a clear preference for BE spelling and the students were generally consistent in their use of one variety. Hence, despite the process of Americanization noticed by other researchers operating in the Swedish context, the preference for BE seems to be strong when it comes to spelling, as concluded by the author.

Although Swedish university students are generally very advanced users of English, an overly informal style was found in essays written in the second year of university studies (Herriman, Reference Herriman2011). The learners tended to select an interactional starting point in written sentences, mainly using personal pronouns (I or you), or forming a question or an imperative, thereby approaching the style of spoken language. As pointed out in earlier research, the lack of awareness of differences in register is one reason for the impression of non-nativelikeness of Swedish advanced learners’ written production and results in a tendency to use an informal and colloquial style (Altenberg & Tapper, Reference Altenberg, Tapper and Granger1998).

In another study on Swedish university students’ writing, Tåqvist (Reference Tåqvist2016) examined unspecific, abstract nouns such as argument, fact, issue, problem, and thing. Their use was explored in a corpus of English L2 academic writing, with the aim of understanding in what ways texts produced by students resemble or differ from those produced by advanced native-speaker students and from expert scientific writing in this respect. Although the L2 writing was found to be similar to native students’ and experts’ texts in many ways, the students’ texts displayed less variety and more frequent occurrences of semantically vague words and also more words expressing attitude and involvement.

Taken together, the findings from Herriman (Reference Herriman2011) and Tåqvist (Reference Tåqvist2016) indicate that Swedish university students of English find it difficult to express themselves with precision in academic texts, and to find the appropriate style using a more colloquial or interactive register than native speakers. Advanced learners would surely benefit from teaching leading to increased awareness of style and register.

As mentioned in 2.3.2.1, like in many other parts of the world, scientific publishing in English is commonplace in Swedish higher education and internationalization is synonymous with the use of English. As noted by Herriman (Reference Herriman2011) and Tåqvist (Reference Tåqvist2016), notwithstanding the generally high level of English proficiency, there are weaknesses in Swedish students’ writing at university level. Also, among postgraduates and researchers, all are not, or do not identify themselves as, fully fledged writers of English, which has been shown by McGrath (Reference McGrath2015) and Rosén and Straszer (Reference Rosén, Straszer, Bendegard, Melander Marttala and Westman2017). In two in-depth studies of researchers and doctoral students in the fields of medicine and natural sciences, Sandström (Reference Sandström2016) and Fryer (Reference Fryer2019) delve into methods for raising academic literacy through multisemiotic approaches and collaborative learning, respectively.

3.1.4 Motivation, attitudes, and beliefs regarding English and Modern Languages

In this section, we examine some studies on how English and other foreign languages are perceived as learning objects. These relate to the attitudinal and policy-related issues outlined in Section 2, especially concerning the subject Modern Languages, and are therefore of high relevance to this review. Most of the studies reviewed concern learners’ viewpoints, but some of them focus also on teachers and parents. Motivation for English has been explored through studies on young people's gaming on the internet (e.g., Henry, Reference Henry and Ushioda2013) and gaming has also been studied in relation to language proficiency (Sundqvist & Sylvén, Reference Sundqvist and Sylvén2014; Sylvén & Sundqvist, Reference Sylvén and Sundqvist2012). While English is generally experienced as important, useful, and consequently motivating (Henry, Reference Henry2012), low motivation for other foreign languages is a phenomenon that has been paid ample attention by Swedish scholars, as well as teachers and policymakers, during the last decades.

For example, Cardelús (Reference Cardelús2015) delved into the problem of lack of motivation, relating it to attitudes toward MLs in a study of 43 upper secondary students. He investigated their motivation and attitudes in questionnaires and interviews on why they had chosen French, German, or Spanish, and what made them carry on with the subject. According to the results from this socio-cognitively informed thesis, encouragement from the family and influence from peers played important roles both in the language choice and for the motivation to continue.

Students’ attitudes towards French have been studied in a series of studies by Plathner (e.g., 2014). Questionnaires were administered to students in lower and upper secondary school to capture their image of France and of the French language in terms of language status. Students’ perceptions of the language and the role these perceptions may play in students’ language choice were discussed, also from a gender perspective.

Attitudes were also studied in the recent project, Learning, teaching and assessment of second foreign languages – an alignment study on oral language proficiency in the Swedish school context, funded by the Swedish Research Council during 2016–2018 (Granfeldt et al., Reference Granfeldt, Bardel, Erickson, Sayehli, Ågren, Österberg and Vetenskapsrådet2019). In a survey of Year 9 students in different parts of Sweden, most of the participants stated that they wanted to know more foreign languages, not only English. At the same time, only approximately 40% agreed that ML is an important school subject (Granfeldt et al., Reference Granfeldt, Bardel, Erickson, Sayehli, Ågren, Österberg and Vetenskapsrådet2019, p. 31). The students’ answers in the questionnaires point, as do teachers’ and principals’ answers in the same project, to a certain incoherence in relation to the subject's status, which is probably related to the fact that there is discrepancy between the individual perception and the signals that policy sends to teachers, principals, and students, and probably also to parents, as the subject is not compulsory.

Language choice and dropouts from ML in compulsory school were further studied and linked to class and gender by Krigh (Reference Krigh2019). Krigh found that predominantly children from the middle and upper middle classes, and especially girls, continued until the end of Year 9. Moreover, the girls were awarded higher final grades than the boys. Data also indicated that well-educated families in both regions held positive attitudes toward ML and were positively inclined to formal and cultural aspects of the study of ML, while families with a lesser amount of educational capital were less positive to the study of ML, emphasizing English as the most important language to learn.

Another survey conducted on a more locally restricted sample from two schools with international profiles showed that the motivation for ML can be very high among students in compulsory school (Henry & Thorsen, Reference Henry and Thorsen2018). A more in-depth qualitative study (Henry, Reference Henry2020) showed positive attitudes among students and high motivation to choose an extra ML in Year 8, in addition to the first one selected in the Language choice (see 2.2.2 and 2.2.3). In this latter study, data were gathered in a metropolitan area in a school where languages were prioritized and students were offered an additional FL on top of English and one ML. Although both studies comprise high numbers of participants and the results contribute to the bigger picture, the specific conditions of both the involved schools make generalizations at a national level unattainable.

Inspired by the concept of the L3 Self (Dörnyei & Ushioda, Reference Dörnyei and Ushioda2009; Henry, Reference Henry2012), Rocher Hahlin (Reference Rocher Hahlin2020) studied motivation focusing on French as a foreign language from two viewpoints. In a first study, pedagogical activities specifically designed to strengthen students’ capacity to see themselves as future speakers of French, were explored. A second study was dedicated to French teachers’ perceptions of themselves as motivators, coining the term Teacher Motivator Self. The two studies indicate that learners’ and teachers’ psychology interact in relation to motivation. Using tasks at an early stage that may stimulate learners’ perception of having a connection to French speaking cultures, and that French can be a part of their future, is recommended.

In another study of ML teachers’ attitudes, Nylén (Reference Nylén2014) explored Spanish teachers’ opinions about grammatical competence in relation to communicative language teaching in a framework based on pedagogical content knowledge (Shulman, Reference Shulman2004) and teacher cognition (Borg, Reference Borg2003). As pointed out by Nylén, the Swedish national syllabus offers no explicit guidelines of how to teach grammar. Data from interviews with 13 participants show that these teachers acknowledged the role of grammar in language teaching and saw communicative competence as a goal. Most of them claimed to draw on their own experiences as learners and teachers when designing grammar class work, rather than their teacher education or language education research, suggesting there being room for improvement in language teachers’ pre- and in-service training.

Studies on learners’ motivation for MLs that have surfaced so far in Sweden are too few to draw any general conclusions about a predominance of either high or low motivation. The results available indicate that motivation fluctuates within individuals and varies among them, and it is clear that a number of students drop out during the last years of compulsory school and switch to English or Swedish (see 2.2.2), even after policy changes have been made, aiming at making students stay. Tholin (Reference Tholin2019) interviewed 16 teachers about their beliefs about why some students choose to discontinue the subject study before reaching the end of compulsory school. Their answers were centred around the perception that the policy changes did no good or even made the situation worse. For example, the problem with many unqualified teachers was pointed out, as was the fact that studying a new language is hard work, while students tend to prioritize less demanding tasks. Five of the teachers claimed that not everyone has the aptitude for language and therefore, according to them, it is natural that some students take the opportunity to drop the subject. Furthermore, 12 of the interviewed teachers believed not all students should study a ML; especially those with another native language than Swedish may need to concentrate on studying Swedish and English, according to these teachers.

On the contrary, attitudes to learning English are generally extremely positive among Swedes, and students’ proficiency levels are among the highest in Europe (see 2.1.2), but this does not mean that teaching this language lacks challenges. As pointed out by Henry et al. (Reference Henry, Sundqvist and Thorsen2019), there is discrepancy in how young people view the language itself, on the one hand, and its teaching and learning in the classroom, on the other. In their studies on motivation, Henry and colleagues notice that young people in Sweden perceive English used in the classroom and the language occurring outside school as two types of English representing two different cultures. English is without doubt a language that exerts a very strong influence on young peoples’ lives and identities in Sweden today (Henry et al., Reference Henry, Sundqvist and Thorsen2019, pp. 23–24). With generally high proficiency and frequent use of ‘extramural English’ (Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist2009; Sylvén, Reference Sylvén2006), learning is efficient, which makes it challenging for the teacher to find motivational practices in the classroom, as well as for teachers of other languages to compete.

Motivation for English was also investigated in Sundqvist and Olin-Scheller (Reference Sundqvist and Olin-Scheller2015), together with a few other topics (ICT, extramural language learning vs learning in school). After providing an extensive literature review on motivation/demotivation in second language learning in general, the authors reflected on their own experiences and drew on data from a small-scale survey administered to English teachers participating in an in-service training for teachers. Key factors raised by the teachers for meeting future demands were the importance of training and its empowering effect on them and getting exposure to alternative ways of teaching.

The perception of English as important to learn is found also in younger learners in Sweden. A dissertation on primary and middle school students’ experiences of foreign language anxiety, beliefs, and agency in connection with speaking in the English classroom filled previous knowledge gaps concerning young learners of English in Sweden (Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2020). Data were gathered through a survey inspired by the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS, Horwitz et al., Reference Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope1986) and through focus group discussions about language learning. Positioned in a socio-cognitive field and hence considering both individual and contextual factors, this work contributes to an increased understanding of children's perspectives on English oral interaction.

We end this subsection with a study by Eriksson (Reference Eriksson, Ljung Egeland, Roberts, Sandlund and Sundqvist2019), on learners of English at upper secondary level who were found to perceive varieties of English as differentially attractive to learn and use. Eriksson asked 129 students which accent they aspired for. Forty-eight percent of the students said they wanted an American (AE) accent, while 35% said they preferred a British (BE) accent. The rest opted for other accents, including Swedish. When asked to describe the American and British varieties, students found both pleasant, but motivated their preference for AE by claiming that it sounded cool and simple, or for BE that it was authentic and prestigious. The study also showed that not all of the students’ teachers had a teaching agenda that comprised world Englishes or English dialects, although all of them claimed to present both BE and AE to their students as the norm.

3.2 Teaching foreign languages in Sweden

3.2.1 Terminological issues

As an instrumental segue from the previous section on learning into the present one on teaching, we would like to refer to an edited volume from Umeå University (Lindgren & Enever, Reference Lindgren and Enever2015), which features contributions from colleagues – most of them based in Sweden – on various topics related to language education. The volume deals with two important topics. First of all, it aims to bridge the well-known gap between research and practice in language education (e.g., Erlam, Reference Erlam2008; Spada, Reference Spada, Bardel, Hedman, Rejman and Zetterholm2022) in an attempt to define the field connecting Applied Linguistics and teaching practice. The Swedish term språkdidaktik is often used to denote this field, many times in relation to Swedish teacher education, and is a constantly growing research field. As the volume editors explain in their Introduction chapter, språkdidaktik includes language as subject matter and theories as well as practices of teaching and learning. Furthermore, according to the editors, the way the Swedish term didaktik and the German Didaktik are used is broader than the English ‘didactics’, the latter referring more closely to teaching methods (Lindgren & Enever, Reference Lindgren and Enever2015, p. 13). This may be the case, but the complex relationship between ‘didactics’, ‘teaching and learning’, and ‘language education’ remains to be clarified, with language education including more aspects of language in relation to teaching and learning, such as the role of language development when learning other subjects than languages, for example. To be fair, some of the contributions in Lindgren and Enever (Reference Lindgren and Enever2015) touch upon this issue (e.g., the text by Ivanov, Deutschmann & Enever).

The remaining studies included in the volume represent different subareas of language education, and those concerned with English and other foreign languages deal mostly with representative topics of Swedish research on English and MLs, such as the teaching and learning of grammar (Johansson Falck); collaborative learning among students of German at the university level (Malmqvist & Valfridsson); Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL, Deutschman & Trang Vu); and written communication in German, a language in which the participants have relatively low proficiency (Knospe, Malmqvist & Valfridsson). In fact, some of these topics occur also in the research reported in the following subsections, which primarily targets teaching perspectives related to formal structures or elements of language (vocabulary, phraseology, and grammar), language teaching and ICT, language policy, multilingualism, and CLIL.

3.2.2 Vocabulary, phraseology, and grammar

Studies of teaching materials are not common in our corpus. It is in our view an important topic, however, and we will here comment on three studies – two on vocabulary in textbooks for young learners of English, and one on grammar in textbooks of Italian produced in Sweden and Italy.

There is wide agreement in the foreign vocabulary learning literature that both incidental and intentional learning presuppose several encounters with words and lexical phrases (Webb & Nation, Reference Webb and Nation2017; Schmitt & Schmitt, Reference Schmitt and Schmitt2020). Nordlund (Reference Nordlund2015) explored what vocabulary was present in a corpus of three commonly used textbooks for school years 4–6 (10–12 years of age), which the most frequent words were, and to what extent words recurred. The author drew the conclusion that there is no consciously considered rationale behind the inclusion of the words in the investigated books, and that many words were hapaxes (i.e., occurred only once). In a co-authored study, Nordlund and Norberg (Reference Nordlund and Norberg2020) also investigated teaching materials, this time seven textbooks for young learners. Again, on the assumption that textbooks need to be designed in an aligned fashion with relevant research findings, the two authors note that there was very little connection between those findings and the limited and seemingly unsystematic appearance of vocabulary in the investigated textbooks. They concluded that this is an issue that needs to be addressed by textbook authors and publishers.

Moving to the language level of morphosyntax, in her thesis Tabaku Sörman (Reference Tabaku Sörman2014) carried out a study of the linguistic input in textbooks of Italian as a foreign/second language. The aim was to understand to what extent certain morphosyntactic features of contemporary (neostandard) Italian, currently discussed in the sociolinguistic field, were present. A comprehensive corpus of 38 textbooks published in Sweden and eight in Italy was compiled and analysed. It was found that for neostandard forms and structures, only those that have obtained normative status in the target language were generally included (e.g., some personal pronouns). As for more complex structures, such as dislocations or cleft sentences, their presence depended on the general level of the material and were found in authentic texts or grammatical explanations but not in books containing simplified language.

Transitioning from analysis of learning materials to studies investigating teaching interventions and teacher beliefs, we would like to mention Snoder (Reference Snoder2019), who aimed at exploring teaching procedures that may actively contribute to increasing learners’ collocational competence in EFL. The impact of instruction on the acquisition of English collocations was explored in three intervention studies carried out in three upper secondary school classrooms. Results from these studies showed that English teachers can increase learners’ collocational competence thanks to relatively small manipulations of teaching methods and input conditions. In an interview study with 14 Swedish EFL teachers, Bergström et al. (Reference Bergström, Norberg and Nordlund2022) investigated teachers’ beliefs of vocabulary development in an upper secondary classroom setting. The authors found that vocabulary was not considered an independent learning objective by the teachers, even if an expressed understanding of the important role of vocabulary in language learning was evident. Incidental learning during reading and playing games dominated as general practice, and even though teachers showed an awareness of what is involved in learning and knowing a word, they were in general not very capable at explaining effective methods to be used for vocabulary learning.

Finally, and along the lines of vocabulary research, worth mentioning is also a study by Lindqvist and Ramnäs (Reference Lindqvist and Ramnäs2020) who discuss vocabulary teaching in the French subject at university level. A case study at Gothenburg University explored the past, current, and future approaches to word learning in a foreign language. They analysed syllabi and other policy documents and lament the general dearth of vocabulary as an explicit component, especially after the introduction of communicative approaches in the early 1990s. With empirical evidence of the importance of vocabulary size as a backdrop, the authors conclude that there is a conspicuous lack of inclusion and actual teaching of French vocabulary in Sweden, leaving students to their own devices. On a positive note, though, they forecast increased attention to research-based approaches to vocabulary learning, such as the framework presented in Laufer (Reference Laufer2017).

3.2.3 Language teaching and ICT

ICT has a pivotal role in Swedish education generally. Computers are used in most subjects and assigning a personal computer to every student in compulsory school is a principle followed by most schools (Skolverket, 2019). Despite this, surprisingly few computer-assisted language learning (CALL) studies have appeared during the time span for our review. In the following, four studies with a foreign language teaching and learning theme are highlighted, the first looking into web-based language learning activities in English for Specific Purposes in higher education, and the three following focusing on the upper secondary level.

Bradley (Reference Bradley2013) is a doctoral thesis based on four case studies of educational designs for engineering students’ activities in blogs and wikis. The data consist of logs of student driven web-based activities and interviews. Each study focuses on a different aspect of collaborative writing, such as blogging and peer-reviewing, and together they show how educational designs utilizing web-based writing technologies may develop discursive, linguistic, and cultural competences. For example, collaboration and co-production of texts in a wiki can enhance students’ engagement in text production at different levels ranging from detailed linguistic questions to discursive and semantic aspects. Furthermore, it is shown how blogging with native speakers about literary topics can help developing intercultural competence.

Örnberg Berglund (Reference Örnberg Berglund, Rosén, Simfors and Sundberg2013) also discusses opportunities and challenges of text-based interaction, but in this case in the EFL classroom of a Swedish upper secondary school. In her small-scale exploratory study, a learning activity was elaborated around instant messaging in a chat forum, where eight students of English interacted with the teacher/researcher. An appealing feature is the author's triangulation of methods, where data from chat logs were complemented with screen recordings, keystroke logging data, and eye tracking data. The article ends with a discussion of potential implications for the foreign language classroom, encouraging teachers to work on raising students’ awareness of different writing genres.

Two Ph.D. students, also teachers of Spanish, participating in the research school FRAMFootnote 9 (Bardel et al., Reference Bardel, Erickson, Granfeldt and Rosén2017), oriented their work toward the CALL field. Both used innovative data collection methods, such as computer screen recordings, and in the case of Källermark Haya (Reference Källermark Haya2015), also audio and video uptake. Källermark Haya explored how upper secondary school students of Spanish performed during a pair activity aimed at searching for information on the internet and writing up a presentation about Latin America. The study aimed at mapping what choices students made while searching for information and what resources they used. Students’ choices were compared with teacher-recommended use of essential resources when accomplishing the task. The results showed that the students focused on the product rather than the learning process, exploiting several strategies, for example using the copy/paste function or searching information in Swedish or English and then using Google Translate to translate text into Spanish, strategies that clearly clashed with the ideas expressed by the teachers.