Introduction

The ethnic distribution of English sociolinguistic variables has been studied in large American cities since the 1960s (see e.g. Labov Reference Labov1966/2006; Labov, Cohen, Robins, & Lewis Reference Labov, Cohen, Robins and Lewis1968; Shuy, Wolfram, & Riley Reference Shuy, Wolfram and Riley1968; Laferriere Reference Laferriere1979). Relatively few such studies, however, have made white, European-Americans their primary focus. Using sociophonetic and ethnographic data collected in Philadelphia, this study contributes to an understanding of why sociolinguistic differences may sometimes be detected between long-established European-American immigrant groups. Irish- and Italian-American adolescents are shown to exhibit a difference in their realization of a local sound change: the centralization of the nucleus of /aɪ/ before voiceless consonants, henceforth (ay0).Footnote 1 Following the approach of Benor (Reference Benor2010) and others working within Eckert's (Reference Eckert2005) “third wave” sociolinguistic framework, the article demonstrates that the (ay0) variable is an indexically rich resource for signaling not only speaker ethnicity, but multiple social meanings, especially within the adolescent lifestage. Although the study focuses only on females, it interrogates the construction of gender (masculinity, femininity) within females. The study shows how ethnic differences can locally index gender, and accomplishes this through an exploration of the “toughness” meaning of centralized (ay0).

It is important to note that centralization of (ay0) is not unique to the Irish and Italians in Philadelphia: it is a community-wide process among all white speakers in the city (Labov Reference Labov2001). Until recently, sociolinguistic differences across ethnic groups in monolingual speech communities have been most prominently attributed to the effects of social segregation and social network, where variation across ethnic groups reflects the diffusion of a linguistic change from group to group over time (e.g. McCafferty Reference McCafferty1998; Boberg Reference Boberg2004). Yet Philadelphia has been home to Irish-Americans and Italian-Americans for over a hundred years (Hershberg Reference Hershberg1981), where they have lived in fairly close proximity, and a previous study found almost no linguistic differences between them (Labov Reference Labov2001). In seeking to account for Irish and Italians' differential employment of (ay0), this article turns to a more agentive view of ethnolinguistic difference, in which speakers participate in language changes or employ stable features “not simply to reflect or reassert their particular pre-ordained place on the social map but to make ideological moves” (Eckert Reference Eckert2008a:464).

Fought (Reference Fought1999, 2003) takes the same approach, demonstrating that Chicano participation in Anglo-led (uw)-frontingFootnote 2 in California is more than an epiphenomenon of speakers' exposure to the Anglo change. Participation depends on a complex array of factors including gang membership and community-specific expectations of gendered behavior. The continuum of (uw)-fronting thus does not perfectly reflect a continuum running from ethnic Chicano to ethnic Anglo identity, but encompasses a diverse array of speakers using (uw) for diverse social purposes. Likewise, in a study of ethnic groups in Toronto, Hoffman & Walker (Reference Hoffman and Walker2010:59) summarize:

the speech community makes available a pool of linguistic features which are associated with (or come to be associated with) particular social distinctions and values…. Whether these features are already extant or are introduced into the pool through first-generation immigrants, speakers adopt and use these features strategically in ethnolinguistic variation.

The present article shows that the high school is a particularly good locus for exploring the “strategic” construction of linguistic correlates of ethnicity. This is especially the case, as pointed out above, in monolingual white speech communities where features derived from immigrants' home languages are (almost) no longer discernible. Indeed, although ethnolinguistic differences typically attenuate over the generations, age grading (Cheshire Reference Cheshire, Ammond, Dittmar and Mattheier2006; Wagner Reference Wagner2012a) may play a role in preserving them. In the present study, therefore, ethnicity is examined from the perspective of a single age group: adolescents aged sixteen to eighteen in their junior or senior year of high school. High school students are heavily engaged in the construction and maintenance of social oppositions (Eckert Reference Eckert1989). Perceived differences between the Irish- and Italian-American communities in Philadelphia today are relatively minimal,Footnote 3 but they are magnified in the high school context and can be recruited for peer-group boundary creation and other meaning-making. The Irish and Italian categories in the high school described here reflect adolescent communities of practice (Lave & Wenger Reference Lave and Wenger1991; Wenger Reference Wenger1998) that are rooted in—but not isomorphic with—opposing local norms of gender and social class behavior. In keeping with the third wave approach just outlined, I argue that for these speakers, raised and/or backed (ay0) is not directly associated with membership in an ethnic category. Instead, it indirectly indexes (Ochs Reference Ochs, Duranti and Goodwin1992) a number of more general qualities such as “toughness” that happen to be more positively valued in the Irish community than the Italian community.

The study

Sacred Heart High School

The linguistic and ethnographic data for this study were collected during two three-month long periods of participant observation in 2005 and 2006. The observation site was “Sacred Heart High School,”Footnote 4 an urban, co-educational Catholic school (grades seven through twelve) in South Philadelphia.Footnote 5 This area is popularly associated with white, working-class culture (Dubin Reference Dubin1996), despite its ethnic diversity (53% white, 34% black, 9% Asian) and a median household income that is only slightly below that of the entire city (~$31,000 Philadelphia, ~$27,000 South Philadelphia). The school itself is located in a majority white, majority Italian ancestry neighborhood, but draws students from parochial grade schools across South Philadelphia.

White South Philadelphians are largely of Irish or Italian descent, with the highest concentration of people of self-identified Irish ancestry (43% Irish) in the eastern Pennsport district known as “Second Street,” a neighborhood that is of central importance in this article. The next highest concentration of Irish ancestry residents is in the western “Thirtieth Street” district (26% Irish), bookending those of Italian ancestry in the middle neighborhoods (57% Italian), with the exception of some narrowly defined districts around 5th to 8th streets that are home to people of various other ethnicities including African-Americans and Asians. People of Italian ancestry are also highly concentrated (82% Italian) in the southern neighborhood of Packer Park. This dense residential aggregate of Italian-Americans in South Philadelphia's highest-income neighborhood has contributed to the conviction among Sacred Heart students (discussed below) that the local Italian community is wealthier than the Irish community.

All of the participants in the Sacred Heart project were white. The whiteness of the school population (at that time, 79% according to internal school records) was important for linguistic reasons. Philadelphia's white community had been extensively studied by sociolinguists since the 1970s (see Labov Reference Labov2001 and references therein) and this provided a detailed baseline for the main goal of the larger study from which the present article is derived: an analysis of the students' participation in community-wide sound changes as they aged (Wagner Reference Wagner2008, Reference Wagner2012b). Earlier studies in the city (Poplack Reference Poplack1978; Adamson & Regan Reference Adamson and Regan1991; Henderson Reference Henderson and Meyerhoff1996) had also established that nonwhites generally do not participate in local mainstream white linguistic changes, even where ethnic communities are fairly well integrated. It became clear to me very rapidly, however, that the white Sacred Heart students did not view themselves as ethnically homogenous, and this provided the impetus for additionally exploring linguistic markers of ethnic affiliation.

Following the methodology employed by Eckert (Reference Eckert1989), I spent most of every day in the school—in the hallways, the cafeteria, and the school offices, and very occasionally in a classroom. The participants represent a convenience sample, located through the “friend of a friend” technique (J. Milroy & L. Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy1985; L. Milroy Reference Milroy, Chambers, Trudgill and Schilling-Estes2002). I conducted digitally audiorecorded sociolinguistic interviews with sixty-six young women,Footnote 6 of whom forty were recorded in both observation periods. The majority of participants were first interviewed in grade twelve, their senior year, aged seventeen to eighteen; others were first interviewed in their junior or sophomore year, aged sixteen to seventeen.

The sample for phonetic analysis

Previous studies of ethnolinguistic features have included variable realization of consonants (e.g. Dubois & Horvath Reference Dubois and Horvath1998; Rose Reference Rose2006; Mendoza-Denton Reference Mendoza-Denton2008), lexical items (De Fina Reference De Fina2007; Benor Reference Benor, Rabinovitch, Goren and Pressman2012), suprasegmental processes such as syllable-timing (Fought & Fought Reference Fought and Fought2002; Torgersen & Szakay Reference Torgersen and Szakay2011), morphosyntax (Malan Reference Malan and De Klerk1996; Green Reference Green2002; Cheshire & Fox Reference Cheshire and Fox2009) and discourse/pragmatics (Meyerhoff Reference Meyerhoff1994; Stubbe Reference Stubbe1998; Torgersen, Gabrielatos, Hoffmann, & Fox Reference Torgersen, Gabrielatos, Hoffmann and Fox2011). The phonetic analysis in this article is limited to the vowel system, in the full acknowledgement that Irish and Italian ethnolinguistic variability is highly unlikely to be confined to these vocalic variables.Footnote 7 Nonetheless, it is the vowel system that has received the most attention over the decades in the literature on the Philadelphia speech community mentioned above (Labov Reference Labov2001; Conn & Horesh Reference Conn and Horesh2002; Conn Reference Conn2005; Fruehwald Reference Fruehwald2008; Wagner Reference Wagner2008; Labov, Baranowski, & Dinkin Reference Labov, Baranowski and Dinkin2010; Fruehwald & MacKenzie Reference Fruehwald and MacKenzie2011; Prichard & Tamminga Reference Prichard and Tamminga2012), and that therefore provides the best community-level backdrop against which to compare the young people in this study.

Eighteen speakers were selected for their socioeconomic and ethnic characteristics (Table 1), and these are discussed in more detail below. For each of the eighteen speakers, their 2005 interviews were manually segmented in Praat 4.5.11Footnote 8 for stressed tokens of forty-seven vowel classes and allophones. The coding system of the Plotnik 8 programFootnote 9 was used, which identifies twenty-five American English vowel classes (Labov Reference Labov1994, Reference Labov2001), thirteen classes of allophones before /l/, and nine classes of allophones before /r/. A minimum of ten tokens per main vowel class was aimed for (although in practice this was not always achieved, due to the brevity of some interviews), with no more than three tokens of any lexical item, for an average of 270 total tokens per speaker.Footnote 10

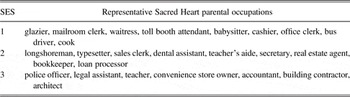

Table 1. Panel for vowel analysis, eighteen speakers by socioeconomic status (SES) and ethnicity.

The ethnic categories of “Irish” and “Italian” are described in more detail in the next section. A composite index of parents' education, caregivers' occupation, and residence value (Conn Reference Conn2005; Wagner Reference Wagner2008) was used to allocate the informants to one of three socioeconomic status (SES) categories. SES 1 represents the lowest socioeconomic category, and SES 3 represents the highest. Categorizing minors by social class is a well-known problem in both sociology (see e.g. Hughes & Perry-Jenkins Reference Hughes and Perry-Jenkins1996 for a review) and sociolinguistics (Eckert Reference Eckert2000; Fought Reference Fought2003; Cameron Reference Cameron2005). Since minors are not yet fully engaged in the socioeconomic activity of their community, it is usual to classify them according to their parents' status, as I have done here. The educational and occupational background of both parents (if relevant) was incorporated into the index calculation. For concision, I present in Table 2 some examples of parental occupations cited by Sacred Heart students, to illustrate the three SES categories.

Table 2. Examples of Sacred Heart parents' occupations by SES.

Ethnicity, or “where you're from”

The ethnic categories assigned to the speakers in Table 1 were based on a combination of self-identification and my own judgment. So many students had mentioned Irish or Italian affiliation in their 2005 interviews that in the 2006 follow-up interviews I gave participants a written survey to complete. It included questions about ethnicity and how the participants would usually describe themselves to others. Ethnicities mentioned by students in the survey included Irish, Italian, German, Polish, English, Armenian, and Chinese. In practice, however, Sacred Heart girls tended to align themselves with one of the two dominant ethnic groups: Irish or Italian. The Irish and Italian designations in Table 1 reflect the written responses provided by the eighteen participants. For the few speakers who described themselves using hyphenated ethnic terms (e.g. Irish-Polish), I coded them as Irish or Italian based on the dominant ethnicity of their neighborhood, information from their interviews, and my own observations of their friendship networks. In conversations, all of the white students I spoke to identified themselves as either Irish and/or Italian, and this binary ethnic opposition was by far the most dominant (white) social segregator in the school.

Across the United States, formerly separate European immigrant ethnic groups have increasingly come to participate in what Hall-Lew (Reference Hall-Lew2010:460) refers to as “the powerful… construction of whiteness,” thereby reducing or eliminating within-white ethnic difference. Yet at Sacred Heart the Irish and the Italians continued to enjoy highly contrastive visibility. The maintenance of Irish and Italian ethnic identity came at the expense of other ethnicities in a local process of erasure (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000). Students appeared to be collectively participating in an “imagined homogenization” (Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine1995:974) of European-Americans at the Sacred Heart as exclusively “Irish” or “Italian.” I saw this homogenization process at work when I conducted a controlled discussion of Sacred Heart peer categories in 2006. A group of girls, who had been seniors in the first round of fieldwork and who were still close friends, completed a collaborative “pile-sort task” (Matthews Reference Matthews2006). Photographs of every member of their senior class, copied from their senior yearbook, were placed in a pile on the table. I asked the girls to sort the photographs into groups using any criteria they chose. They immediately sorted the nonwhite students into two groups (“Blacks” and “Asians”) and removed them from further consideration. By the end of the task, nine of the twenty groups—and the majority of the students—had been defined by race, neighborhood, or grade school: for white students, all instantiations of Irish and Italian ethnicity. Conversations with other students demonstrate that these criteria were not particular to the group engaged in the pile-sort task. In (1), Courtney and Danielle spontaneously raised the subject of their own ethnicities.

(1)

Courtney: You're in the Irish part. I'm in the Italian part […]

Danielle: Yeah, we- In school you go by where you're from.

The frequently invoked concept of “where you're from” did not concern ancestral countries: none of the girls were “from” Ireland or Italy. Rather, membership in one of the two opposed ethnic categories was perceived as and legitimized by a combination of biological heritage, residence in an ethnic neighborhood, attendance at an Irish- or Italian-dominant grade school, past affiliation with a local street corner or park, and present social network. In (2) two Italian students contrasted peers from traditionally Irish neighborhoods (Second Street and Thirtieth Street) with peers from Italian neighborhoods.

(2)

Monica: [Eighth grade], that's when we started like knowing like people from the other side of Broad [Street] [i.e. other Italians]…. But like the Second Streeters and all and the Thirtieth Streeters [i.e. Irish], we—

Natalie: Yeah, we don't like know them and we don't really talk to them ‘cause they're not- they're different from us. They're not like us.

Monica: Yeah, they clique together.

Natalie: Yeah. Different types of people. There's definitely an Italian-Irish split, I think.

Neighborhood-based ethnic ties constrained the establishment of new friendships when students started attending Sacred Heart. It is noteworthy that Monica, in (2), implies that she had no friends beyond her Italian social network prior to eighth grade—that is, for her entire first academic year at Sacred Heart. Because ethnic group membership at Sacred Heart could be defined along several parameters, one could be more or less Irish, or more or less Italian. The school continuum ranged from the most iconically Irish students (“Second Streeters”) to the most iconically Italian (“princesses”),Footnote 11 with everyone else in between, or excluded altogether.Footnote 12 No jock-burnout continuum emerged of the kind described by Eckert (Reference Eckert1989), or indeed any single set of “populars” (Moore Reference Moore2003). In (3), jocks and burnouts were explicitly rejected.

(3)

SW: … people who are really school-oriented versus people who are really nonschool-

Hayley: No, we really break down by neighborhoods.

Julia: Exactly. [general agreement, yeses, etc.] And corners. Corners and neighborhoods.

Melissa: Corners and parishes, like old [grade] schools.

Opinions differed regarding the importance of neighborhood for ethnic membership. Danielle, for example, was from an Irish family and grew up on Second Street, but she had attended an Italian grade school outside her neighborhood and so had many Italian friends. Nonetheless, in her view, neighborhood residence was a primary determinant of category membership, and she made a claim to Irish ethnic identity on this basis. “If Second Street ever gets into a fight,” she told me, “even though… I don't even stayFootnote 13 there, I'd have to be part of Second Street side.” But her claim to Irish membership wasn't ratified by other students. In the pile-sort task she was described as “someone who's really popular” but “not popular on Second Street,” and thus “someone who doesn't really belong there.” In other words, popular kids existed, but there were distinct groups of Irish popular kids and Italian popular kids. Irish popular kids were usually those whose social lives were heavily intertwined with multigenerational networks on Second Street, and who spent a lot of time there in its parks and on its corners. Danielle wasn't one of these kids, so the sorters didn't know what to do with her. Their additional refusal to group her with the Italian popular crowd, even though the Italian populars were her friends, underlines the possibility that popularity at Sacred Heart was not independent of the Irish-Italian ethnicity continuum.

Whatever the disagreements over the classification of individuals into ethnic groups, white students at Sacred Heart were unified in their strong foregrounding of these social categories. Since we might reasonably expect to find linguistic differentiation where we find social differentiation, the vocalic systems of the nine Irish and nine Italian students in the present sample were compared.

Results

Labov's 1970s survey of white Philadelphia English found that ethnicity (Italian, Irish, Jewish, German, WASP)Footnote 14 generally did not co-vary with vowel production (Labov Reference Labov2001:257). Only in the fronting of (uw) (as in shoe, boot) and (ow) (as in go, boat) was there a clear effect of ethnicity, where Italians lagged approximately 100–200 Hz behind other ethnic groups. Substrate influence from Italian was not an explanatory factor (Labov Reference Labov2001:258–59). The data were collected at a time when Irish-Italian social tension and segregation were still evident. In his popular account of the history of South Philadelphia, former journalist Murray Dubin quotes a Polish-American who was born in South Philadelphia in the 1940s and who recalled of his youth.

Italians… [didn't] date Two-Streeters. It was a pretty rough neighborhood in those days, all Polish and Irish. Going south, you start running into guys you knew, but it was a different territory, and you had to have good reasons for being down there. They didn't like you dating girls in their neighborhood, but they tolerated it. (Dubin Reference Dubin1996:188)

In (4), Italian-American Veronica describes Irish-Italian relations when her father was young, perhaps a decade after Labov's project.

(4)

Veronica: Yeah, the Italian people don't like the Second Streeters. And the Second Streeters are all the people who are Irish. A lot of Irish people live on Second Street. And a lot of Italian people live from Sixth Street over. And so you got the Irish people on one side and the Italian people on one side. And they always used to battle. Like, they always used to hate each other. Now it's just starting to calm down since we got older. And like- some- like an Italian boy might like an Irish girl so- I mean, it's calming down but you can still see a little rivalry.

SW: So you mean it's calming down since you all got to high school, or it's calming down generally over the generations?

Veronica: Over generations. Like my dad used to tell me when he lived in- on Sixth Street where I always lived that you weren't allowed to pass Second Street because of the Irish people.

SW: Wow. Were these like big street fights?

Veronica: Yeah, yeah. It was just like, I guess you could say the West Side Story (laughs). It was just like that except there were Italian and Irish people.

SW: Was your dad ever in a fight?

Veronica: Yes. Especially with the Second Streeters.

SW: Really? Did he tell you stories about it?

Veronica: Yeah. He was like, “I used to like this Irish girl and I wanted to go out with her so bad and then we tried to go out and then”, he's like, “I got jumped because the Irish people didn't like me.”

By the time the Sacred Heart participants were in high school, the ethnic tension between Italians and Irish had become more moderate. Veronica told me that the tension had “come down” since her father's youth. The retarding effect of Italian ethnicity on (ow) and (uw) had apparently also lessened as the two groups became more integrated. In the Sacred Heart data, Italian lagging was evident only for the checked allophone of (ow), as in, for example, phone, most, hose (Wagner Reference Wagner2008:189–90). It appears that this particular correlation with ethnicity has waned since the 1970s. No significant ethnic effects were found for any of the other vowels, with the exception of (ay0).

(ay0)

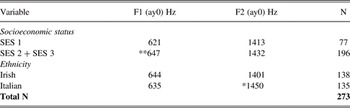

Significant effects of ethnicity and social class emerged in a series of t-test comparisons of vowel means. Table 3 displays the mean F1 and F2 for speakers grouped by socioeconomic status and ethnicity.

Table 3. Normalized means of (ay0) for eighteen speakers by SES and ethnicity.

** p ≤ 0.001; * p ≤ 0.05

The results in Table 3 show that there is an effect of social class on the height of the (ay0) nucleus, with speakers in SES 1, the lowest social class group, exhibiting more raised nuclei on average than their peers in SES 2 and SES 3. This is unsurprising: the raising of the nucleus of (ay0) was identified as a “new and vigorous change” in the 1970s (Labov Reference Labov2001) led by the working class, and the nucleus has continued to raise rapidly in the decades since (Conn Reference Conn2005; Labov Reference Labov2011), with the working class still in the lead.

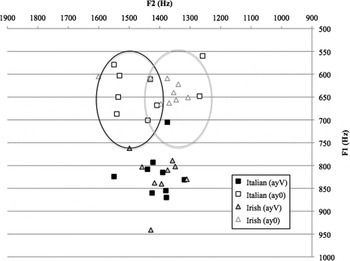

No effect of ethnicity on the front-back dimension of (ay0) had previously been identified, however. Yet it can be seen in Table 3 that on average the nine Irish teenagers are significantly more advanced than the nine Italians with an F2 value that is on average approximately 50Hz backer than the Italian F2 value. Figure 1 displays, for each of the eighteen speakers, the mean F1 and F2 of (ay0) and of (ayV), which is the nucleus of /ai/ before voiced consonants (e.g. bide, time). The raising of (ay0) in the F1 dimension is apparent. The normalized means for the Italian girls’ (ay0) cluster within the black-outlined oval to the left, while the means for the Irish girls cluster within the gray-outlined oval to the right. Even though, at the individual level, the speaker with the frontest mean (ay0) is an Irish girl, Melanie, and the backest nuclei were produced by two Italian girls, Becky and Courtney, the general trend is for Irish girls to produce (ay) further back when it is followed by a voiceless consonant rather than (ay) before voiced consonants. In contrast, Italian girls produce (ay) before voiceless consonants in a fronter position rather than (ay) before voiced consonants.

Figure 1. Mean (ay0) and (ayV) values for eighteen speakers by ethnicity.

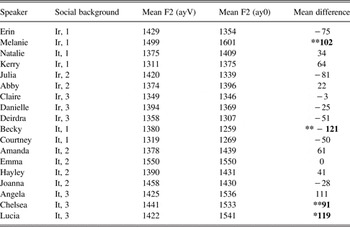

In an analysis of the unnormalized (ay0) means by individual, all but one of the speakers (Natalie), exhibited (ay0) nuclei that were significantly higher than their (ayV) nuclei (p < 0.05). Thus all speakers except NatalieFootnote 15 display the allophonic distribution of (ayV) and (ay0) that we would expect for Philadelphians their age. For the front-back dimension each individual's unnormalized F2 of (ayV) was compared with her normalized F2 for (ay0) in a t-test. Speakers whose (ayV) and (ay0) F2 values were significantly different (i.e. their mean (ay0) was significantly fronter or backer than (ayV)) are indicated in Table 4 with asterisks.

Table 4. Unnormalized mean values of (ayV) and (ay0) by individual speaker (Ir = Irish; It = Italian; 1, 2, 3 = SES 1, 2, 3 respectively).

** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05; all others are not significant.

Most speakers show no significant difference in F2 between their nuclei of (ay0) and (ayV); the exceptions are Melanie, Lucia, and Chelsea, whose (ay0) is significantly fronter than their (ayV), and Becky, whose (ay0) is significantly backer. Overall, however, Irish girls' F2 of (ay0) is on average 75 Hz backer than their mean F2 of (ayV), and Italian girls' (ay0) is on average 287 Hz fronter than their (ayV), as derived from the individual normalized mean differences in the right-hand column of Table 4.

Discussion

The association of more backed (ay0) nuclei with Irish girls and more central or fronted (ay0) nuclei with Italian girls is subtle, but it is reflective of the symbolic values attached to the (ay0) front-back dimension in the wider community. I argue in this section that in Philadelphia, (ay0) indexes men and the working class, and that the teenage girls in this study are making use of (ay0)'s indexical meanings for their own local, age-appropriate stylistic purposes.

Previous studies: Production and perception of (ay0)

In the 1970s, the raising of the nucleus of (ay0) in Philadelphia was being led by the working class, as mentioned in the previous section. Evidence that this lead has been maintained has been provided in follow-up studies, such as Conn's (Reference Conn2005) trend replication of Labov's 1970s apparent time survey of the city. Conn's study also revealed that a slow (ay0) backing change was in progress, and that this backing was only evident in the working classes (Conn Reference Conn2005:101). Although no sex effects have been demonstrated for the backing change, both Labov (Reference Labov2001) and Conn (Reference Conn2005) report that men are leading in the raising of the nucleus. This is an extraordinary finding, given that women have repeatedly been shown to lead linguistic change (Labov Reference Labov1990). Men and the working class are therefore implicated as the vanguard in changes in the phonetic position of (ay0).

Labov (Reference Labov2001:203–4) described (ay0) in the 1970s as a “change from below,” in the sense of being below the level of public awareness. Noone in that study commented explicitly on (ay0), as they often did for the older sound changes such as the nearly completed tensing of (aeh).Footnote 16 Conn likewise did not report any overt mention of (ay0) among his participants in their discussions of typical Philadelphia speech. However, in the 1970s subjective reaction tests, people consistently downgraded advanced variants of (ay0), a typical reaction to an ongoing change from below that suggests some sensitivity to the change. In the 2000s, Conn's participants went a step further, downgrading only the advanced variants of (ay0) produced by a female speaker, and upgrading advanced variants produced by a male speaker. The male-produced advanced (ay0) variants were evaluated as tougher and more masculine than the conservative variants. It is possible that if Labov had played (ay0) samples produced by both male and female speakers that he would have gotten similar results, and this hypothesis is supported by some of the off-the-cuff comments noted by the fieldworker, Ann Bower (Labov Reference Labov2001:203). In South Philadelphia, an Italian informant described the advanced variants as “Two-streets! sounds like the Irish on Second Street.” In an Irish neighborhood, a young woman said that the advanced variants sounded “like tough kids.” Hindle's (Reference Hindle1980) study of the speech of a single subject, Carol Meyers, over the course of a single day, provided data on (ay0)'s sensitivity to social situations. Carol produced more advanced variants when she was at work, and less advanced variants when playing bridge at home with her girlfriends. In other words, we can suppose that more advanced, male-like variants were appropriate in the tougher, male-dominated world of work, while more conservative, female-like variants were appropriate for the bridge game.

Centralized variants of (ay0) thus appear to have covert prestige (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1972) in Philadelphia. Centralization is led by men and the working class, and this is to some extent perceived by members of the speech community, who assign these traits to advanced speakers and evaluate them positively if speakers embody those social characteristics. Yet as Ochs (Reference Ochs, Duranti and Goodwin1992:341) has argued for gender categories, social meanings rarely map straightforwardly or statically on to any macrosocial categories such as “male” and “working-class.” Rather, these meanings are constantly available for activation (or not) by speakers and listeners in their construction and deconstruction of linguistic style. By using advanced variants of (ay0), speakers are not necessarily making the claim that they are members of the working class, or that they are men; nor are they even positioning themselves as “like men” or “like the working class.” As Eckert (Reference Eckert2008a:455) points out, “women (and men) are not saying ‘I'm a woman’ when they use a ‘female-led’ change, nor are they saying ‘I'm not a woman’ when they do not.” Under this view, the relationship between a sociolinguistic variable and the demographic categories in which it is most frequently produced is an indirect and fluid one. Variables accrue interrelated meanings (an “indexical field” in Eckert's terms) not only at the macrolevel, but also at the local, microsocial level; existing meanings are reinforced and new meanings acquired in the moment of interaction. This might especially be the case for changes in progress, whose indexical fields may be “less well-defined” than those for well-established variables such as (ing), (-t, -d) deletion, (dh), and hyper-articulation of (t), but “leave more room for local interpretation” (Eckert Reference Eckert2008a:471).

In Philadelphia, as we have seen, advanced (ay0) variants were heard not only as male and working class, but as typical of Irish speakers from the iconic South Philadelphia neighborhood of Second Street. This suggests that (ay0) is best understood as available for interpretation at several levels of indexicality (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003). At a first-order level, it is heard by local listeners as indexing local Irish ethnicity; but it simultaneously activates second-order indexical meanings such as “working class” (for the Irish community in Philadelphia, both a historical and a contemporary association), which in turn activates third-order indexical meanings such as “male” and “tough.” In the next section, I explore the indexical relationship between Second Street and toughness through my observations of and conversations with Sacred Heart students.

Two-streets! Sounds like the Irish on Second Street

Second Street—also known as “Two Street”—was more frequently mentioned at Sacred Heart than any other South Philadelphia neighborhood. In Gal & Irvine's (Reference Gal and Irvine1995:973) terms, it iconically represents the Irish community's “inherent nature,” and was locally perceived as embodying the essence of Irishness. Melissa, for instance, expressed it this way:

(5)

Melissa: If you say Second Street to somebody in Philly they're like, “Oh, Second Street.” Like if you—You could say something like, “Oh, that's so Second Street!” and people would know exactly what you're talking about. […] Second Street is always Irish. If you're Irish, you're probably from Second Street. If you look Irish or your name is Irish you probably are from Second Street.

No single locality was ever as strongly associated with the Italian community in any of the conversations I had with students. Natalie commented, “We're all Italian but we don't show it, like ‘Oh, we're Italian.’ Like the Irish people are so into that they're Irish.” Her observation that the Irish in school “are so into that they're Irish” was confirmed by the girls' choice of AOL screen names. At the time, AOL was the service most commonly used by the girls who had an internet connection at home, and I used the AOL instant messenger service to contact them. For the thirty-nine screen names I collected (Table 5), only two of the Italian girls opted to incorporate ethnic names like bella and bella ragazza ‘beautiful girl.’ Yet fully twelve of the seventeen Irish girls incorporated an ethnic marker, usually a variation on “Two Street.”

Table 5. AOL screen names as markers of ethnic identity.

A student who described herself as “from Second Street” or as a “Second Streeter” rather than “from Pennsport” (the municipal name for the wider neighborhood in which Second Street is located) or “from Third and Mifflin” (a street intersection in the neighborhood) was not only describing where she lived, nor simply claiming Irish ethnicity, but claiming allegiance to the most salient cultural practices of Second Street. Melissa's characterization of Second Street in (6) is representative of many other similar descriptions:

(6)

Melissa: Second Street is like um where—you know, where the clubhouses are. Where the Mummers are, all that stuff. They're all down that way. And it's a big drinking area, and you know, nobody has a problem with underage drinking down there. And that's a whole group of people who hang out together. They all go to, you know, [parochial elementary school] or um what else [parochial elementary school]. And they're that kind of, you know—they're all friends. … It's like you know, blue collar working class.

Melissa sketches Second Street with a few key features of what she typifies as its “blue collar” culture: dense social networks, drinking, and turning a blind eye to drinking laws. Melissa was a middle-class Italian, but the same features were described proudly by Second Streeters themselves. It was a place where everyone knew everyone else. Girls explained to me the concept of the “Second Street cousin,” or child of an unrelated family friend. Second Street provided numerous places for people to interact with their neighbors: clubhouses of the many working-class men's performance groups known as Mummers Clubs, a highly popular neighborhood basketball center, and, as I was told by everyone, “a bar on every corner.”

These local perceptions of Second Street are crucial to interpreting the distribution of (ay0) in the Sacred Heart sample. Second Street is strongly locally associated with the same indexical meanings that listeners in previous studies assigned to advanced tokens of (ay0): Irish ethnicity, working class, but also maleness and toughness. As such, “Second Street” is itself at the center of an indexical field. “Second Street” indexes the local construction of Irishness. This in turn indexes a set of values and practices with related social connotations, in both local and nonlocal spheres. Local Irishness indexes drinking in corner bars, a practice that is traditionally associated both in Philadelphia and across the nation with working-class men. Local Irishness also indexes the Mummers Clubs, which are heavily male-dominated and function as additional places to drink. As for sports, although participating in or watching sports was common to both sexes at the Second Street community sports center, it is still a traditionally male activity in the wider Philadelphian and national community. The dominant sport at the sports center, amateur basketball, was played by both sexes, but it is associated more generally in American culture with urban, working-class men.Footnote 17

For young Irish women in the high school, sports in particular were used as a cultural shorthand for “typical” Irish characteristics. The exchange in (7) highlights the locally foregrounded intersection of Irish ethnicity and masculinity. Abby and Kaitlyn, both Irish girls, are talking about boys from a local all-male school who recently joined their class. They present the boys' reported speech as evidence that Irish girls' interest in sports is one of several indicators that they are independent, with appealingly male-like qualities. They explicitly contrast the laidback attitude of Irish girls with that of the “dagos,”Footnote 18 who are prissy and helpless. Likewise, in (8), Irish-affiliated girls, Sarah and Melanie, unflatteringly characterize the most Italian of Italian girls as über-feminine “Italian princesses.”

(7)

Kaitlyn: Even like the boys that like came are like, “Irish girls are so much easier than like–”

Abby: Yeah. They know it's a lot easier. Cause we're so much more laidback. Like, we don't care.

Kaitlyn: Yeah. Like, they're like, “Youse are all easy-going.” He's like, “The dagos, we have to be like, Oh my god, like you wanna do this, go here, you can't do this for yourself.” He's like, “Youse, like, girls like sports and everything!”

Abby: Yeah! Or when we like- burp and stuff.

(8)

Sarah: Well, sometimes like, you have the Italian princesses, they are dagos.

Melanie: The stuck-up ones who wear the too much lip liner, and put their—

Sarah: And all the gold jewelry and all the perfect bags and everything perfect.

Melanie: And their mothers go tanning and they look like they were in a toaster.

Italian girls were similarly dismissive of the Irish girls' behavior, sometimes explicitly characterizing it as masculine (see (8)). When I asked Natalie and her friend Monica (both Italians) about a street fight that had occurred outside the school that week, Natalie claimed not to know anything about it. Monica filled it in: it was a fight between Second Street and an Italian gang, and “the Second Street girls were in it too.” Natalie responded indignantly in (9).

(9)

Natalie: See, like that, like that they wanted to fight. We would never really like-… We wouldn't act like that. […] We just act like girls and we don't act like men and try to like fight or whatever all the time…

Natalie's comments reflect the prevailing ideology in the school that Italian girls were more feminine than Irish girls. My own observations also support this. Successful construction of ethnic identity at Sacred Heart was achieved through a process of bricolage (Hebdige Reference Hebdige1984): the assembling of symbolic resources such as hairstyle, dress, and physical demeanor that in concert could be interpreted locally as constituting “Irish” or “Italian.” Italian girls were likelier to have hair that was more artfully arranged and wear greater quantities of make-up and jewelry. Irish girls and Italian girls alike wore make-up, carried small reproduction designer purses and sported nail extensions, but Italian girls were more likely to do all of these things, while Irish girls might carry the purse and wear nail extensions, but eschew heavy make-up and wear their hair pulled back in a ponytail. Irish girls were more likely to tell me that they “didn't care” how they looked at school, with the implication often being that Second Street—and not school—was their primary arena for social display. Irish girls were also more likely than Italian girls to tell funny stories about their own physical clumsiness. The Irish girls themselves didn't necessarily display “toughness” in the sense of aggressiveness, but their subversion of some of the expected norms of female demeanor led to the perception within the school that they were “acting like men,” and thus that they were “tough” and liked to fight. As Natalie's comment underscores, however, the local interpretation of symbolic resources occurs in the context of wider societal meanings. Acting like a Sacred Heart Irish girl can only be understood as “acting like men” in a Western society where clumsiness, for instance, is considered an undesirable trait in women. In a similar analysis, Eckert (Reference Eckert2008a:548) describes the wearing of pastel-colored clothes by popular preppy girls in a California school as being locally associated with their peer group, but nonlocally associated (“culture-wide”) with innocence: a characteristic that is also desirably associated in American culture with females. In other words, to indicate their position as nice girls (i.e. proper, well-behaved girls) in the local peer social order, preppy girls had not coincidentally selected pastels as one of the components of their style. It is also not coincidental, I would argue, that components of Irish girl style (or the proportion of their use) index masculinity at a societal level, while components of Italian girl style index femininity.

Eckert (Reference Eckert2000) has also pointed out that language is an important component in adolescent stylistic bricolage. The (ay0) variable is an indexically rich resource available for this process, and the results of the sociophonetic analysis suggest that it is certainly recruited. Centralized—and especially backed—(ay0) is associated with Second Street girls such as Erin, who display a certain kind of male-like camaraderie with each other and with boys. Thus Second Street and (ay0) lie at the intersection in Sacred Heart of masculinity and Irish ethnicity: two social values that locally index “toughness,” and this is reflected in the backed variants of (ay0) produced by Irish girls.

Centralized (ay0) was associated with toughness in another study, too: the Burnouts at Belten High produced the most advanced tokens of this vowel in general, and particularly when discussing their own nonconformist behavior, such as staying out all night, being hyper (Eckert Reference Eckert, Guy, Feagin, Schiffrin and Baugh1996). Gordon & Heath (Reference Gordon and Heath1998) went so far as to suggest that the association of men (or in the present case, stereotypical features of masculinity) with back-vowel changes might prove to be a sociolinguistic universal for English. Backed (ay0) is not, therefore, the exclusive symbolic province of the Irish. Rather, it can perhaps be employed by any American English speaker displaying toughness: something that is much likelier to be necessary for SES 1 speakers such as Becky and Courtney, regardless of their Italian ethnic affiliation.

In her only interview Courtney devoted a good deal of time to describing South Philadelphian territories. She told me her neighborhood was “okay where I'm at, but two blocks down it's pretty bad.” Friends and family from suburban New Jersey, she told me scornfully, were usually scared when they came to visit: “They wanna go home so bad […] I don't see anything wrong with it though. I guess I'm just a city girl.” More than any other student, Courtney talked with authority about the rivalry between particular “corners” and her brother's loyalty to Eighteenth Street, an iconic Italian neighborhood: “He stays there on that corner all day every day.” While it seemed clear that it was her brother who generally participated in actual fights, Courtney too was prepared to get involved, because “the worst thing you can do is back down from someone around here.” Perceived slights should always be responded to, especially if directed at members of her family.

(10)

Courtney: I hate that, when people try to make me look inferior. I hate that. And then the only time I ever f- like I fought other than that was wi- over my brother.

SW: And what was that about? Tell me what happened.

Courtney: Actually it was just something that just- it wasn't even anything that had to do with me. Him and his ex- girlfriend broke up. And uh, she did some really messed up things too, and he was like real upset over it. And I seen her, just, you know— Like my brother is like my world. If there's anybody in my family that- it's him. Like I know he's not like, you know, the greatest person in the world– But he's the same way with me though. Like there's times he's went to like Thirtieth Street to go find someone who just pushed me.

Courtney told me that her parents raised her to defend herself. People in her neighborhood fight all the time, she said, “I mean, to be dead honest, like, some people say they like to fight […] That's how my brother is. He enjoys it. He'll sit on that corner all day and wait for trouble to fall into his lap. See I'm not like that. I just stay out of everything.” But while Courtney might not have participated in corner fights, it was clear that she was proud of both her brother's and her neighborhood's notoriety.

Becky, by contrast, did not talk about fights, but her best friend was Irish and she spent more time at her friend Erin's house on Second Street than her own, because “her [Erin's] parents don't care.” If Becky is making use of backed (ay0), it is perhaps to assert her allegiance to the more casual, unpretentious lifestyle of the Second Streeters whom she admires, whereas for Courtney this vowel is associated with her self-image as a potentially tough street fighter who will defend herself if provoked.

Conclusion

Labov (Reference Labov2001) found little evidence of ethnic differentiation in the Philadelphia vocalic system in the 1970s. The present study shows that even when the linguistic effects of ethnic affiliation may not be discernible at the level of the wider speech community, they can be located and explored within specific community subgroups or “communities of practice” (Wenger Reference Wenger1998). Adolescents, potentially, are especially motivated to foreground minor ethnic differences as they negotiate their way through the social marketplace of institutionalized education. Among adolescent girls in South Philadelphia, self-identification as Irish- or Italian-American has subtle effects on their production of (ay0), a vowel not previously recognized as having an ethnic distribution at the community level in Philadelphia. Backer variants of (ay0) were more likely to be produced by Irish girls, or by Italian girls for whom “toughness” was an especially important social meaning. (ay0) indexed “toughness” at both local and supralocal levels. At the level of the school, Irish girls presented a modified form of “toughness” through their reduced participation in the feminine, sexualized rituals of hair and make-up that are performed by Italian adolescent girls, and by their embrace of more stereotypically male behaviors such as burping and fighting. At the level of the local community, the Second Street neighborhood that iconically represents the Irish community in South Philadelphia is associated with the “tough” practices and values of traditional working-class culture, such as physical prowess (sports, fighting), drinking, and loyalty to neighbors. Beyond Philadelphia, (ay0) may also index “toughness” through its association with masculinity and nonconformity. I have argued that an understanding of how ethnicity is constructed at a variety of levels, and within a restricted set of social parameters (age, sex, locality), is necessary to discern how speakers are deploying linguistic features to convey their ethnic affiliation. I believe there is no question that in long-established immigrant communities such as those of the Irish and Italians in South Philadelphia, in which few or no first-language transfer effects are discernible in the majority's use of English, we cannot speak of “ethnolects” or “ethnic varieties.” Rather, we must be guided by recent approaches (Eckert Reference Eckert2008b; Benor Reference Benor2010; Hoffman & Walker Reference Hoffman and Walker2010) in which the linguistic construction of ethnicity is viewed as a dynamic process, both from moment-to-moment and from setting-to-setting, as well as across generations. The present study has also supported the notion that ethnicity itself is a fluid concept, and that this can be surprisingly evident even in highly culturally and linguistically assimilated communities such as Sacred Heart, in which an individual's claimed ethnicity can encode a linked cluster of social characteristics that go well beyond ancestors' country of origin. In these cases ethnicity is no more and no less than an orientation to a set of behaviors (linguistic, interpersonal, stylistic) that are regularly perceived by others as constituting a meaningful social category, regardless of whether this category is Irish, gay (Podesva Reference Podesva2007), nerd (Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz1999), hip hop (Cutler Reference Cutler1999), Southern (Allbritten Reference Allbritten2011), Catholic (McCafferty Reference McCafferty1998), or some other locally or supralocally recognized category. Yet the vowel system of Philadelphia English is clearly not the locus of Irish-Italian linguistic differentiation, as both the present study and earlier studies of Philadelphia have demonstrated. It may be that for these longstanding, co-existing ethnic communities, differentiation in the vowel system requires sharper social differentiation than Irish-Italian adolescent rivalry provides. Future work in the South Philadelphia speech community should look beyond vowels, perhaps to consonants (one of my interviewees parodied a typical “princess” Italian mother, using affricated voiceless stops), or perhaps suprasegmental features, as Eckert and her students have fruitfully shown for preadolescent girls (Eckert Reference Eckert2010) and gay male “divas” (Podesva Reference Podesva2007), among other social groups and communities of practice. It is, however, crucial that we continue to relate findings from small, socially bound groups such as the Sacred Heart girls to the wider local speech community (Labov Reference Labov2011) if we are to understand how “ethnicity” interacts with ongoing language change.