INTRODUCTION

For as much as they may appreciate their fans, celebrities also have a vested interest in keeping themselves separate from and inaccessible to their admirers. Yet many celebrities also attempt to minimize the appearance of this separation. One explanation for this is the importance of appearing ‘authentic’—that is, more closely aligned with the ‘ordinary’ and the ‘everyday’—because it allows the celebrity to assert a broader moral credibility (Tolson Reference Tolson2001:445), which in turn leverages positive publicity for and interest in a celebrity's works. In recent years, as social media technologies have created new kinds of public spheres (Habermas Reference Habermas1991) in which celebrity culture operates, celebrities have developed new strategies for maintaining the existence of this order, while concurrently emphasizing their authentic alignment with ordinary people.

Two important techniques for authenticity management include strategies aligned with Goffman's (Reference Goffman1972) civil inattention and Sacks’ (Reference Sacks and Atkinson1985) notion of doing being ordinary. Through civil inattention, celebrities maintain a ‘moral order’ that asserts the separation of the ‘ordinary’ social worlds that fans move in from the ‘extraordinary’ lives of celebrities, even when a fan happens to run into a celebrity in public (Ferris Reference Ferris2004). And in order to enact civil inattention, celebrities must instead carefully attend to the business of doing being ordinary (Sacks Reference Sacks and Atkinson1985). While a celebrity's presence in a grocery store or a public park full of ‘ordinary’ people is, almost by definition, ‘extraordinary’, celebrities can do being ordinary by upholding the interactional and presentational norms of the given frame. This might mean, among other things, avoiding outlandish red-carpet style outfits, not stopping to sign autographs and take selfies with fans, and generally keeping a low profile. Failure to uphold these norms entails the risk of being deemed attention-seeking, egocentric, narcissistic, and, most importantly, inauthentic. Techniques of civil inattention and doing being ordinary are also used to authenticate (Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2003) public personae in mediatized contexts, such as when a journalist positively comments on how ‘friendly’ or ‘down-to-earth’ a celebrity interviewee seemed. In either case, such moves authenticate by aligning the celebrity with the moral credibility of the ‘ordinary’ and ‘everyday’, while still allowing the celebrity to benefit from access to exclusive spaces and opportunities.

Pop star Lady Gaga regularly flouts norms of both civil inattention and doing being ordinary, yet still manages to maintain a strong sense of ‘authentic’ credibility amongst her fans. With the release of her first major radio single in 2008, she quickly gained notoriety for her extravagant artistic and personal style. In these early days, Lady Gaga often came across as cold, strange, or obnoxiously intellectual in her interviews with media journalists. By contrast, the persona she constructed in interactions with her fans was personable, friendly, and familiar. These contrasting linguistic strategies, used across different mediated communication platforms, offer a productive site to discuss the relationship between sociolinguistic theories of stance and audience design, and how these concepts can sharpen our understanding of the moral order(s) of public space.

In this article, I argue that Lady Gaga is able to maintain both her ‘unordinariness’ and her ‘authenticity’ simultaneously by engaging in stancetaking moves that highlight her alignment with her fans above all other audiences. Specifically, I examine linguistic stance-taking moves in Lady Gaga's interactions with fans via the microblogging website Twitter, and her interactions with media journalists. In the following sections, I discuss how theories of celebrity, moral orders, stance, audience design, and authenticity intersect to provide the theoretical foundations of this article. After a brief history of Lady Gaga's career, I then present an analysis of the linguistic strategies used in a corpus of her Twitter posts and interviews with journalists. The divergent stance-taking moves used on these platforms serve to mask or delegitimize the divide between the ‘ordinary’ and ‘extraordinary’ spheres of the fan-celebrity moral order, thus allowing her to lay claim to the authenticity of ordinariness—regardless of whether it is Lady Gaga herself or her management that is the true ‘author’ of the discourse (Goffman Reference Goffman1981), and despite continuing to benefit from the social divide between fans and stars. This analysis of Lady Gaga's language use provides a nuanced understanding of what ‘authenticity’ can mean in the context of the new publics created by social media and (post)modern fan-celebrity relations, and the ways in which the fault lines of public space(s) can be shaped through language use.

THE MORAL ORDER OF PUBLIC SPHERES

Virtually all work examining the role of celebrity argues that the category confers power and privilege on those who inhabit it. Ferris’ (Reference Ferris2004) work situates the privileged category of celebrity in relation to ‘ordinary’ folk, and within the public space(s) of everyday, normal, run-of-the-mill interaction. Ferris focuses on ‘celebrity sightings’—chance encounters with a public figure in the course of one's everyday life—but her interpretation of these interactions within a framework of ‘moral orders’ is applicable to other aspects of fan-celebrity interaction, and to the broader cultural understanding of this social role.

Ferris describes moral orders as sets of shared norms and values that ‘[facilitate] social cohesion, [provide] a form of social control, [offer] a set of rules for behavior for which persons are held accountable, and [furnish] guidelines for managing conflicts when they arise’ (Ferris Reference Ferris2004:242). For instance, in many Western contexts, seeing a friend in public requires you to at least stop and chat (extenuating circumstances, which must be explicitly invoked, e.g. ‘Sorry I can't stop to chat, I'm in a big hurry! I'll call you later!’, notwithstanding). Conversely, while there is certainly an expectation that we will smile and greet a work colleague if we pass them in the street after hours, we do not necessarily need to stop for a long chat. Smiling and greeting a stranger who you pass in the street is even less of a moral imperative.

Moral orders thus shape how we move through public space, and in particular they speak to an organizing principle of modern urban life that Goffman (Reference Goffman1972) described as civil inattention. This principle can be understood as a moral order that values avoiding imposition and maintaining social distance, even among groups in close social proximity. Goffman uses this concept to illustrate how cities can be simultaneously crowded and anonymous, but it also helps us understand how the ‘public’ aspect of ‘public-place encounters’ is connected to a sense of ordinariness. Civil inattention is a technique of doing being ordinary (Sacks Reference Sacks and Atkinson1985), and it is crucial for public-place encounters with celebrities, who despite moving through public space exist in an ‘ideal sphere’ even more socially removed from the average person (Goffman Reference Goffman1967). Although fans may develop what feels like an intimate relationship with the celebrities they admire, this ‘parasocial’ (Giles Reference Giles2002) relationship is one-sided, so the normal rules for approaching someone you know when you see them in public cannot apply. Even when they do decide to risk the face-threat imminent in approaching and soliciting interaction from a celebrity, fans often acknowledge (either in the moment, or in posthoc reflections on the encounter) the rupture to the moral order of such interactions (Ferris Reference Ferris2004). In other words, these ‘ordinary’ people express a fine-tuned sensitivity to the ‘extraordinary’ aura that protects celebrities as they moves through public space. Celebrity privacy can be ‘protected’ by ordinary people by engaging in civil inattention: when faced with an extraordinary person in an ordinary sphere, they look away, pretend not to see, or hear, and thereby maintain the separation between the celebrity's extraordinary world and their own.

Such moral orders do not only constrain fan behavior. Ferris notes that celebrities out in public spaces who either work too hard to draw attention to themselves, or try overly hard to conceal their identities, are perceived negatively (Ferris Reference Ferris2004). In addition to disrupting the expectations of the fan-celebrity moral order, this kind of attention-drawing behavior may also damage a celebrity's ability to claim the moral credibility of ‘authenticity’—a claim that demands alignment with the ordinary and the everyday. By presenting themselves as ‘authentic’ and relatable, stars are able to build a base of hard-core, dedicated fans (Marshall Reference Marshall1997:178–80). Authenticity, then, is crucial to a pop star's commercial success, and therefore an economic imperative. But media and mediated contexts are often and widely seen as inherently inauthentic. Tolson's (Reference Tolson2001) work addresses how celebrities can achieve this perception of authenticity, even in mediated contexts.

Focusing on an autobiographical documentary project of Geri Halliwell, formerly of the British pop group Spice Girls, Tolson analyzes how talk is used to construct an authentic persona. Specifically, Tolson observes how Halliwell discusses the problematics of ‘being ordinary’ when one is a celebrity. Using strategies like the ‘Do you know what I mean?’ tag question following narratives of bothersome aspects of celebrity life, Halliwell generates an alignment with the ordinary lives of fans. While the audience has no experiential evidence of the difficulties celebrities face, Halliwell's discursive invitation for viewers to imagine the vulnerability of such a position acknowledges the difficulty of being ordinary in mass-mediated contexts. Such moves allow her to lay claim to the moral credibility, and thus the authenticity of ordinariness. Because authenticity is not a static quality (Eckert Reference Eckert2003), but an accomplishment (Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2003), linguistic, discursive, and other semiotic choices are important tools for achieving this. One type of linguistic strategy through which authenticity can be accomplished is stance-taking.

STANCE, AUDIENCE DESIGN, AND AUTHENTICITY

Building on Goffman's notions of participant roles, framing, and footing (Goffman Reference Goffman1959, Reference Goffman1981), the last 15–20 years have seen a major increase in sociolinguistic research on stance and stance-taking. The concept of stance is multiplex and heterogeneous, but offers practical, theoretical, and methodological tools for understanding how relations among individuals, and between and across broader social groups, are constructed through language.

Du Bois’ definition of stance is a useful and usual place to begin: ‘a public act by a social actor, achieved dialogically through overt communicative means (language, gesture, and other symbolic forms), through which social actors simultaneously evaluate objects, position subjects (themselves and others), and align with other subjects, with respect to any salient dimension of the sociocultural field’ (Du Bois Reference Du Bois and Englebretson2007:163). This definition highlights the fact that virtually any ‘communicative means’ can be used to evaluate, position, and align. Dialect forms (Johnstone Reference Johnstone and Englebretson2007), morphological markers (Shoaps Reference Shoaps2009), slang (Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2009), and phonological variation (Kiesling Reference Kiesling2009) are only some of the linguistic forms that have been shown to index stance. Jaffe (Reference Jaffe2009b:1) describes this indexing not as a static relationship, but as a process, and these processual perspectives foreground the interplay between language, interpersonal stance, and the broader social meanings of such stances.

In her 2009 analysis of the speaking style of Texas politician Barbara Jordan, Johnstone shows how stancetaking in interaction can project personal authority and moral consistency. She terms this stancetaking strategy the ethos of self: the linguistic and discursive presentation of moral authority and credibility through reference to one's unique history and individual point of view (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2009:30). Johnstone notes that in many contexts ‘speakers whose appeal rests on being perceived as moral and intellectual authorities may encourage less overt negotiation of meaning with the audience than speakers who frame their ethical (i.e. ethos-based) appeal in more egalitarian terms’ (39). Barbara Jordan's authoritative stance is achieved ‘by remaining detached from her audience, frequently making assertions of fact and infrequently attempting to create rapport. She sounds formal, precise, and careful rather than informal or relaxed the way a more audience-centered, rapport-building speaker might’ (39). Lady Gaga uses a similar ethos of self strategy in her interviews with journalists, as I discuss further on.

Understandings of stance such as those described above suggest an agentive, even self-conscious shaping of the self through linguistic choice. Although Irvine recognizes the strengths of this emphasis of ‘point of view and action’, she has also noted that an overemphasis on the explicitly addressed intentions of an individual speaker ‘risks producing a form of methodological individualism, such that the speaker's role in constructing social and linguistic outcomes is taken to be the only, or at least the most crucial, focus of analysis and locus of explanation’ (Irvine Reference Irvine2009:54). This is a reasonable concern to raise in dealing with quotidian genres of speech. In the case of public figures, however, this emphasis on agency and awareness is warranted. There is a widespread presumption that all public celebrity speech is hyper-designed and highly edited (Dilling-Hansen Reference Dilling-Hansen2015). Although it is certainly within the realm of possibility that, even in mediated contexts, celebrities speak ‘off the cuff’, many fans seem to agree that it is naive to assume that any public celebrity speech is wholly unedited. Since there is no way to independently verify whether or not a celebrity's interview speech or Twitter posts were truly unplanned, for this analysis it is more productive to take Lady Gaga's language in the same way her fans do—that is, as authentic, genuine, and intimate (Dilling-Hansen Reference Dilling-Hansen2015).

An agentive approach to stance also makes clear the role of audience design (Bell Reference Bell1984, Reference Bell, Eckert and Rickford2001) in constructing an authentic, morally credible celebrity persona. Audience design is a model for explaining how and why speakers may choose different linguistic resources—including stancetaking strategies—to respond to different kinds of audiences (Bell Reference Bell, Eckert and Rickford2001:145). As Bell points out, audience design is an ongoing, ever-present process, even in everyday conversation between ordinary people (Bell Reference Bell1984:187), but it is plainly evident how the concept is useful for analyses of public speech by public figures. In the subsequent sections, I present data from two different genres of Lady Gaga's public speech. Although the stance-taking moves themselves are different for each genre, I show how they both ultimately orient to the same audience (her fans). The stance-taking moves that construct this audience design simultaneously underscore the construction of her consistent persona, thus lending a moral credibility to her celebrity persona that allows her fans to read her as ‘authentic’.

WHO IS LADY GAGA?

Born Stefani Germanotta in 1986, Lady Gaga began her career as a go-go dancer in New York City. She worked briefly as a songwriter for Sony before landing a record deal with Interscope Records. Her 2008 debut album, The Fame, was a tremendous commercial and critical success. Her early musical and performance style drew heavily on the avant-garde scene of New York's Lower East Side, and her appearance and attitude in interviews with journalists strongly reflected this performance artist aesthetic. Just under two years after the release of her first album, Gaga released an eight-song EP, titled The Fame Monster, dealing lyrically with the dark sides of fame. When performing tracks from this album, Gaga would refer to the audience as ‘monsters’. Around this time, Gaga's base of hard-core, dedicated fans grew substantially. This growth was especially evident on the social networking site Twitter, where in 2011 she had amassed millions of followers. Twitter was also an important early site for community building among Lady Gaga fans, where many alluded to Gaga's ‘monster’ references in performances by referring to her as ‘mother monster’ and simultaneously to themselves as her ‘little monsters’. Soon after, Gaga adopted these relational terms, even tattooing the words Little Monsters on her arm. Unlike the terms Deadhead, and Gleek (for fans of the band Grateful Dead and the television show Glee, respectively), which allowed fans to identify themselves as a group of supporters of a particular cultural icon, ‘little monster’ emerged as a co-constructed effort by both fans and Gaga herself to define a Lady Gaga fan identity.

STANCES OF RELATIONAL CLOSENESS ON TWITTER

The mechanics of Twitter and its communicative affordances

Since its beginnings in 2006, the microblogging website Twitter has become an increasingly important platform for public discourse. While many people use Twitter to simply express short thoughts, many users also wish to direct comments at other users in a more specific manner. Perhaps the most common way of doing this is by including their username, preceded by the @ symbol. Including this type of collocation in a tweet notifies the indicated user that someone has tagged them in a tweet. This tactic is often referred to as @-ing someone. It is also possible to publicly reply to tweets. Users can retweet (sometimes referred to as RT-ing) something that another user has written, either by itself, or with the addition of some of their own commentary. RTs without commentary are often used to express agreement with or enjoyment of the original tweet, but it is also often used as a method for engaging in public disagreement.

Although not a communicative affordance per se, another feature of Twitter that is relevant to this analysis is the blue check mark that appears before certain account names, seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Lady Gaga's verified Twitter account.

This icon indicates a ‘verified account’: an account that has been determined by Twitter's operational team to be legitimately/officially run by the person or group with whom the account is associated. It is not the case, however, that a blue check mark indicates that tweets from the account come directly from the celebrity themselves: in many cases, official accounts are administered by a social media team, and tweets that come directly from the celebrity individual are specifically marked as such to differentiate them from tweets published by the team. There is no such distinction made on Lady Gaga's account, although that does not discount the possibility that an employee, rather than Gaga herself, drafts, edits, and/or publishes the tweets. Dilling-Hansen's (Reference Dilling-Hansen2015) work on the emotional experiences of Lady Gaga fans suggests that while her fans are aware of the possibility that Lady Gaga is not truly the ‘animator’ of her social media posts (Goffman Reference Goffman1981), they still experience her presence on these sites as ‘authentically’ her.

Verification offers celebrities a communicative affordance that I call unidirectionality. Verified accounts are presumed to deal with incredible amounts of traffic, so most users who tweet to a verified account accept that the likelihood of the account responding is slim. For verified celebrity accounts, Twitter can serve as a ‘one-way’ (hence, unidirectional) form of communication to an audience, without the pragmatic requirement of responding to bids for interaction from the audience. Because the possibility of response from a celebrity account does technically exist, though, many fans do engage with celebrity Twitter accounts, in the hope that they will be granted the unique and exciting experience of a close encounter with a celebrity (Ferris Reference Ferris2001, Reference Ferris2004).

Lady Gaga's verified Twitter account1 was started in 2008, at the beginning of her mainstream musical career. I manually compiled 583 tweets via screenshotting that were published by the account between 2009–2017 in which Lady Gaga speaks about her fans, speaks to her fans in general, or interacts with a fan in particular. The tweets analyzed here represent iconic/prototypical cases of some of the major recurrent themes in tweets about or directed to fans, particularly. Below, I show how posts to Lady Gaga's Twitter account linguistically construct stances of relational and/or physical closeness with her fans. These stance-taking moves, coupled with the sense of pseudo-intimacy that the communicative affordances of Twitter supports, allow Lady Gaga to demonstrate an ‘authentic’, morally credible rejection of the typical moral order of fan-celebrity relationships.

Relationship terms and the construction of shared physical space

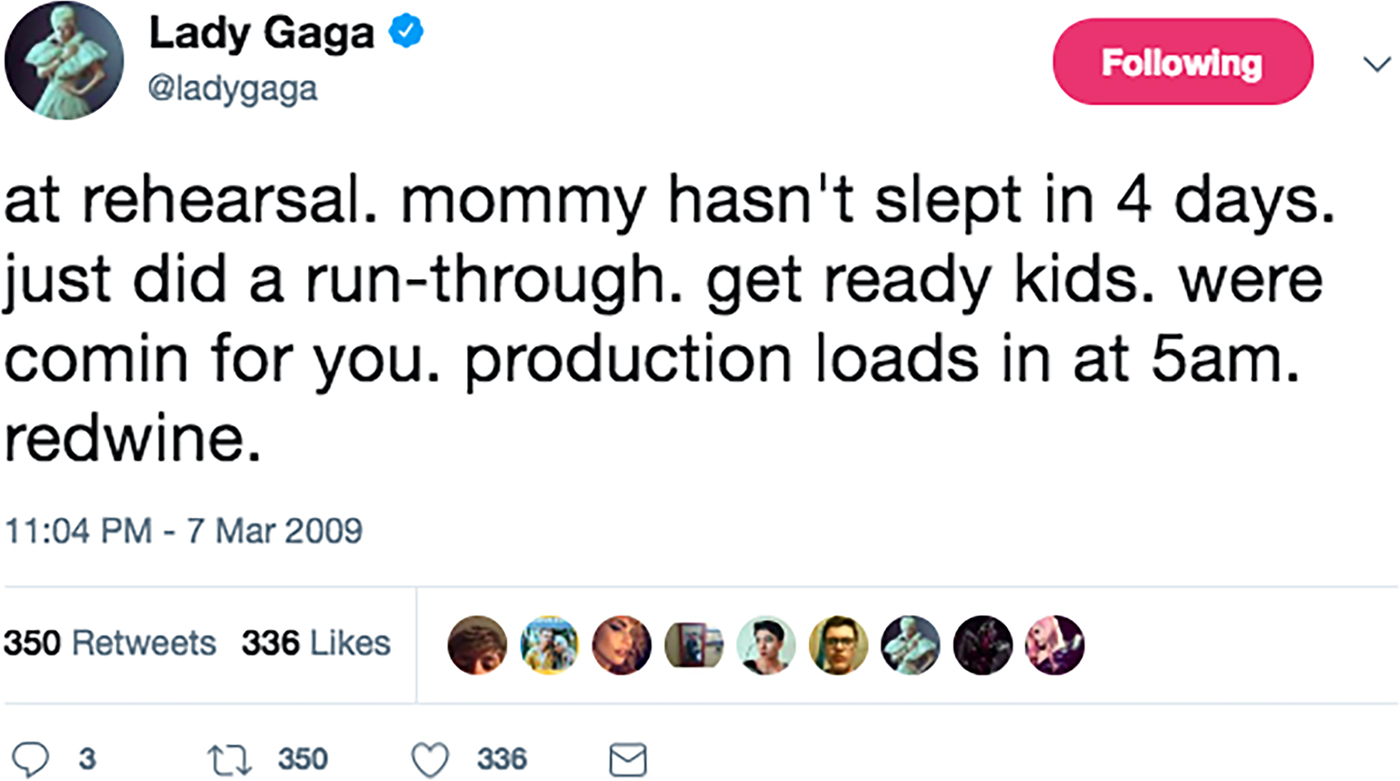

In some tweets, Lady Gaga uses terms that refer to intimate relationships to construct a stance of relational closeness with her fans. One such instance occurred in a 2009 tweet (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Lady Gaga tweet from March 7, 2009.

In this update about tour rehearsal and production, Lady Gaga uses familial kinship terms to describe both herself and her fans. In doing so, she invokes a stance of intimacy and closeness. Not only does this legitimize the strong sense of closeness that hard-core fans feel for her, it elevates that sense of closeness to the level of a socially sacred relationship: that between mother and child. It is possible that this sort of stance-taking move is what precipitated the use of the paired terms little monsters/mother monster to refer to Lady Gaga's hard-core fan community and Lady Gaga, respectively. There is also evidence that this choice of relationship terminology is a deliberate one by Lady Gaga, such as the reply to a fan's tweet, shown in Figure 3 above.

Figure 3. Lady Gaga's reply to a fan tweet on September 22, 2017.

After one fan's critique of other fans’ reference to Lady Gaga using kinship terms like mother, Lady Gaga responded directly, claiming ownership of the term and explicitly highlighting how she sees the relationship with her fans as “unique”. Although in this specific interaction, the stance that Lady Gaga takes toward this individual fan is conflicting, the stance it encodes with respect to fans as a group is one of legitimate, intimate closeness.

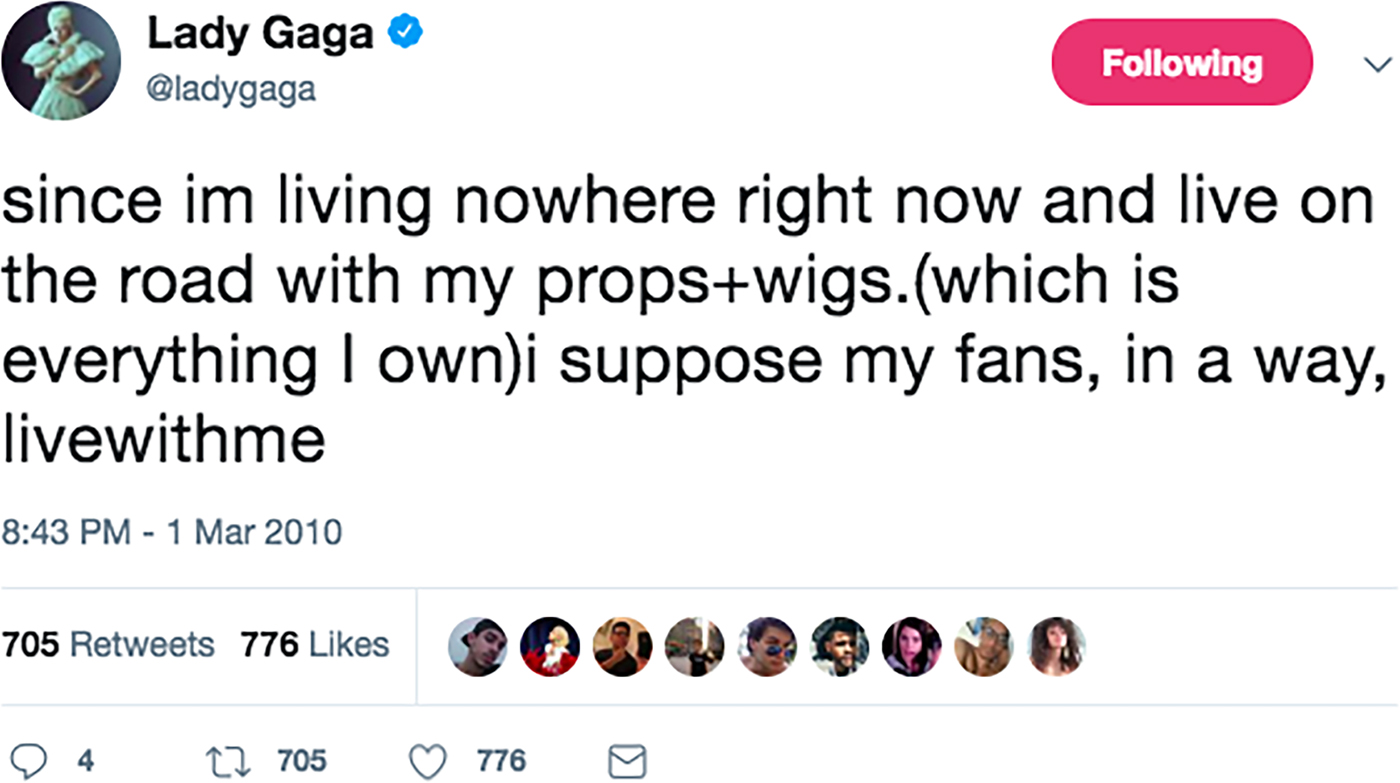

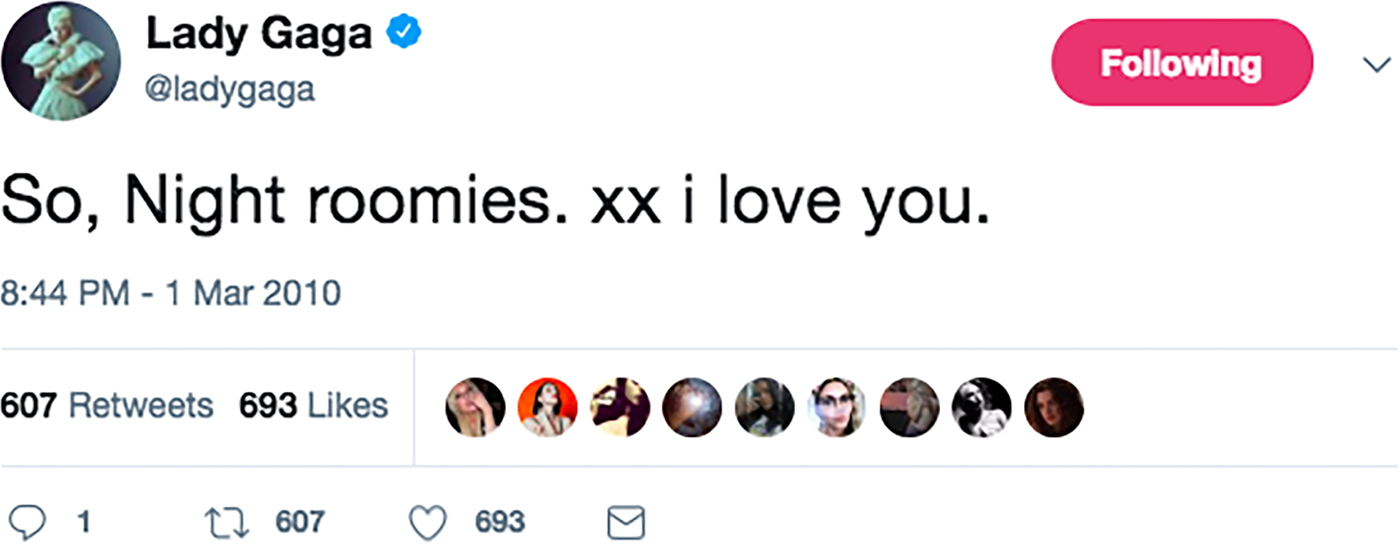

In addition to emotionally charged terms of reference such as mother or kids, Lady Gaga has also used other intimate relationship terms to refer to her fans. On March 1, 2010, Lady Gaga posted the following two tweets one right after the other (see Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. Lady Gaga tweet from March 1, 2010.

Figure 5. Lady Gaga tweet from March 1, 2010.

By framing her fans as “roomies” (roommates), Lady Gaga not only invokes an intimate relationship category, but also metaphorically describes her fans as sharing physical space with her. This stance invites fans to see themselves as part of Lady Gaga's elite, celebrity sphere, metaphorically erasing the invisible boundary separating fans from stars.

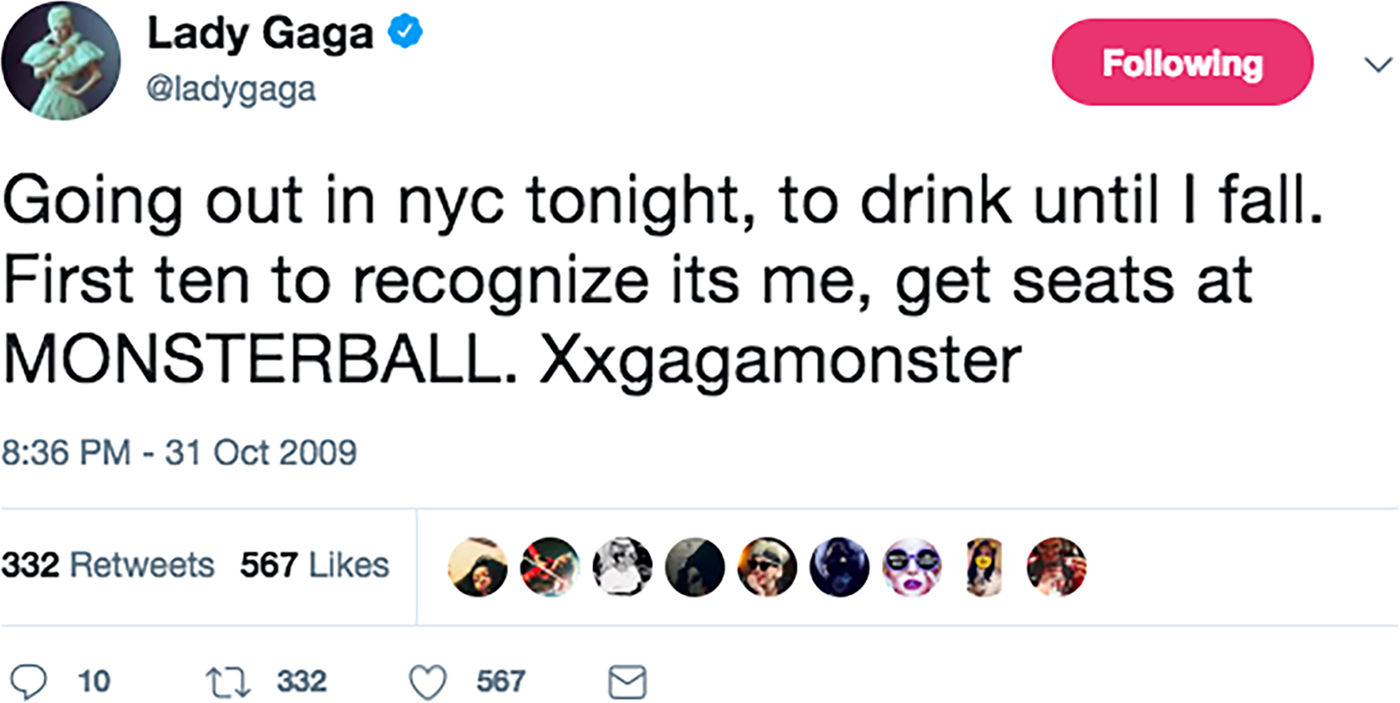

In other tweets from the earlier years in her career, Lady Gaga has challenged the boundaries between fan and celebrity in a more direct way. Consider the tweet, shown in Figure 6, from Halloween night of 2009.

Figure 6. Lady Gaga tweet from October 31, 2009.

In this tweet, Lady Gaga explicitly invites fans to transgress the fan-celebrity moral order. Not only does this alleviate fears of potential face-threats when approaching celebrity in public, it offers the possibility of being rewarded for it. Here, Lady Gaga goes beyond the usual stance of relational closeness that a celebrity might want to cultivate with fans. Although the appearance of social accessibility is useful for celebrity (as it strengthens the claims one can make on authenticity), most celebrities would likely want to preserve the distinction between the elite sphere of celebrities and the ordinary, everyday sphere of fans (Ferris Reference Ferris2004). With this tweet, the discursive erasure (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000) of personal and physical distance between fans and Lady Gaga becomes material. The stance of relational and physical closeness that we have seen her cultivate in some of the previously discussed tweets is now anchored in a real-life opportunity. Fans are able to read this as evidence of Lady Gaga's morally credible claim to the authenticity of being ‘ordinary’.

Pronoun choice

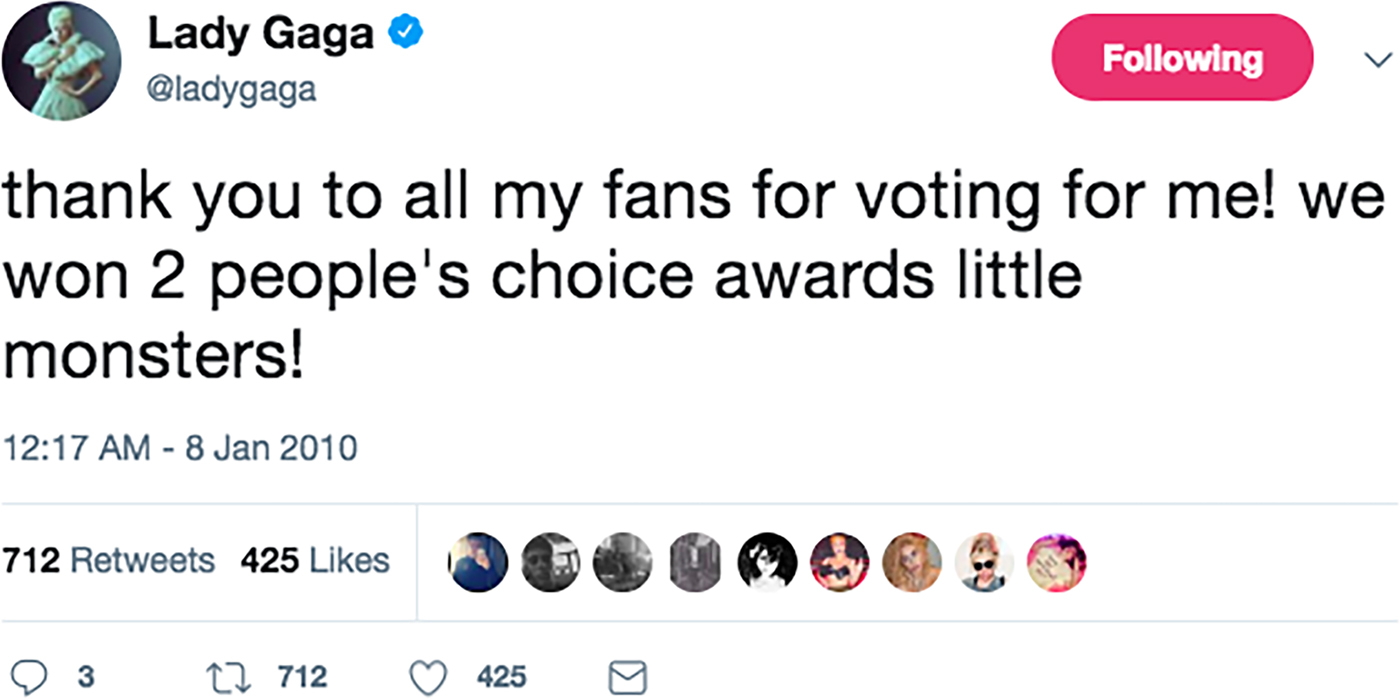

Lady Gaga also uses pronoun choice to construct stances of relational closeness. When tweeting about awards, Lady Gaga frequently uses third person plural pronouns to announce a win. This is illustrated in a tweet following the 2010 People's Choice Awards (CBS), shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Lady Gaga tweet from January 8, 2010.

By using a pronoun that semantically includes fans, Lady Gaga frames her professional wins as wins for which her fans can take credit and ownership. Here, Lady Gaga seems to be ceding a certain degree of the prestige of celebrity to her fans, incorporating their identities into the construction of her celebrity persona. This reflects a stance of relational closeness by metaphorically merging the identities of ‘fans’ and ‘Lady Gaga’.

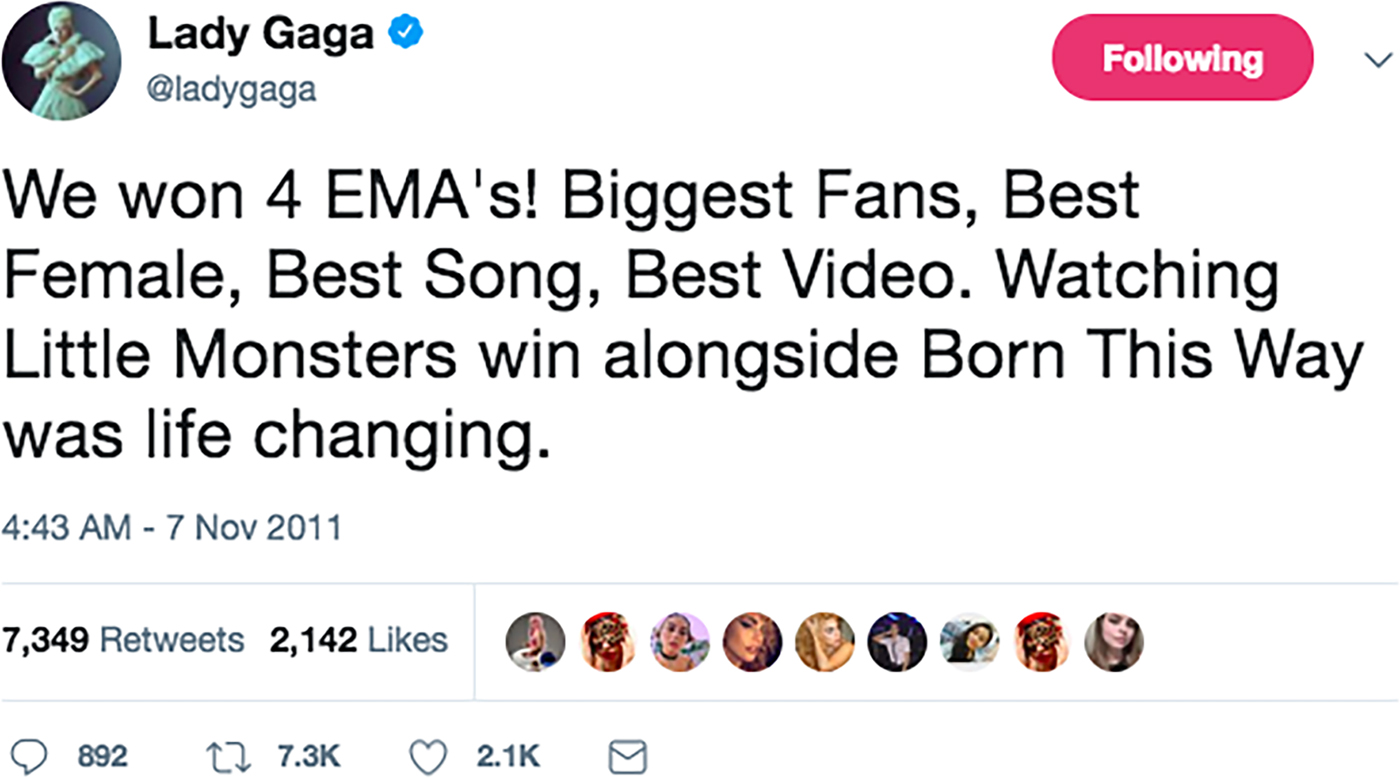

Lady Gaga's Twitter account has published at least eleven posts with the collocation we won, referring to awards that Lady Gaga was nominated for and for which she discursively rejects sole ownership—so the case above is not an isolated incident. Another interesting case came following the 2011 MTV Europe Music Awards.

The two tweets shown in Figures 8 and 9 reflect the order in which several awards that Lady Gaga was nominated for at the Europe Music Awards (produced by MTV) were announced. In the first tweet, Lady Gaga reacts to the announcement that she—or rather her fans—have won the award in the somewhat unusual category, ‘Biggest Fans’. This was the first year that an award in this category was given. In response to the Biggest Fans award, Lady Gaga tweeted that it was the award she most wanted, using the first person singular pronoun I, but follows it directly with a third person plural pronoun in we won. Later in the night, Lady Gaga tweeted about the other awards she won, still using the third person plural to refer to the win (“We won 4 EMAs!”). In this second tweet, she also refers back to the earlier win, stating that “watching Little Monsters win alongside [the album] was life changing”, implying a distinction between a win for the fans and a win for Lady Gaga herself. This indeterminate pronoun use truly blurs the lines between Lady Gaga and little monsters, thereby constructing a stance of relational closeness that goes even beyond the use of relationship terms. Not only do Lady Gaga and her fans share an intimate, personal relationship, they are almost one and the same person.

Figure 8. Lady Gaga tweet from November 6, 2011.

Figure 9. Lady Gaga tweet from November 7, 2011.

One final case of a stance of relational closeness being constructed through pronoun choice occurred on December 31, 2010. In anticipation of the release of her second full-length studio album, Lady Gaga published the tweet shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Lady Gaga tweet from December 31, 2010.

In this tweet, Lady Gaga uses the second person singular pronoun you to frame her fans as agents of actions that Lady Gaga (and her team) undertook. Metaphorically, this usage of you names little monsters as authors both of Lady Gaga's upcoming album, and of Lady Gaga herself. More literally, this pronoun usage blurs the distinction between the fan and the celebrity. By referring to her fans as authors of her work, Lady Gaga does not simply adopt a stance of relational closeness to her fans—she inverts the fan-celebrity relationship, inviting her fans to take credit for her artistic accomplishments.

Directly responding to fans

The use of relationship terms, references to shared physical space, and pronoun choice are all linguistic tools that Lady Gaga has used to construct a stance of relational closeness with her fans. However, there is nothing about these linguistic tools that restricts their use to Twitter posts. In this section, I describe one way in which Lady Gaga adopts a stance of relational closeness with her fans that may be specific to Twitter (but possibly to social media sites more generally).

As described above, the affordance of unidirectionality in celebrity Twitter posts constrains fans’ pragmatic expectations about celebrity behavior on the site. Generally, fans may assume that due to the sheer volume of tweets a celebrity receives, the chances of their tweet garnering a response are vanishingly slim (Dilling-Hansen Reference Dilling-Hansen2015). Lady Gaga has shown that occasionally violating this assumption can be used to demonstrate a stance of relational closeness with fans. One example of this, in response to a fan critique, has already been demonstrated (Figure 3). A tweet from October 3, 2009, shown in Figure 11, also demonstrates this strategy.

Figure 11. Lady Gaga tweet from October 3, 2009.

With this metapragmatic commentary on real-time fan conversations on Twitter, Lady Gaga suggests that when she logs on to Twitter, it is not just to promote her work or garner attention for herself, but just to see what her fans are ‘up to’. While this example does not illustrate a breaking of expectation of unidirectionality, it does communicate to fans that the possibility for such a breakage is there—perhaps more so than with other celebrities, who do not demonstrate an awareness of what fan conversations are happening on Twitter.

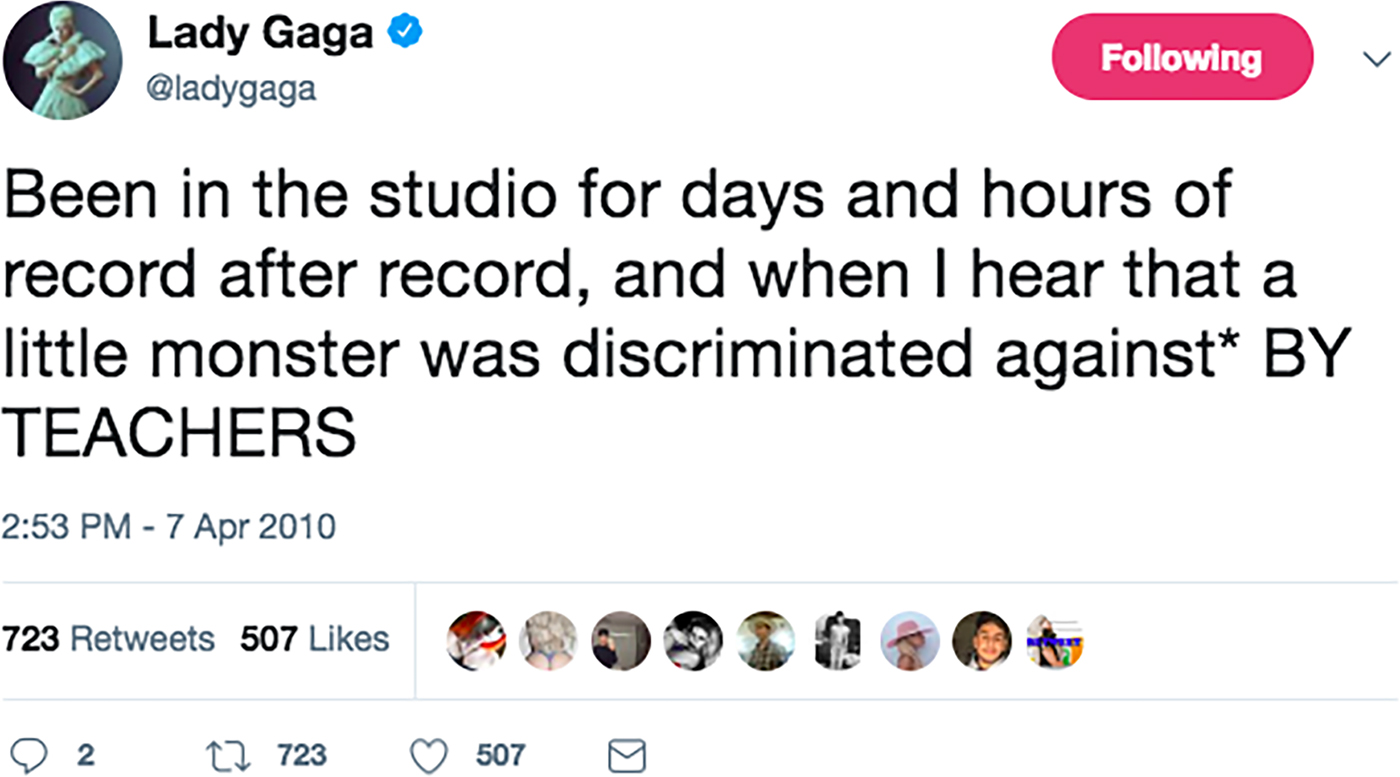

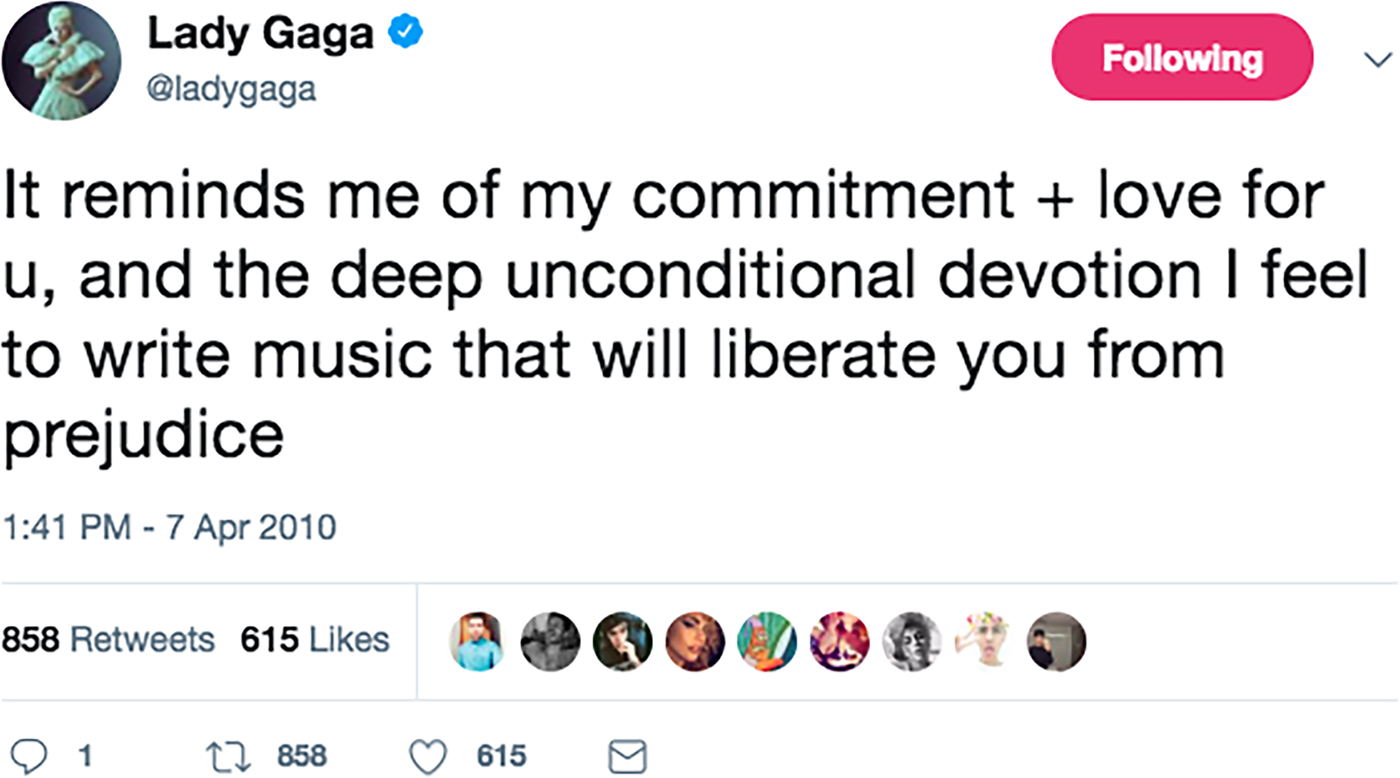

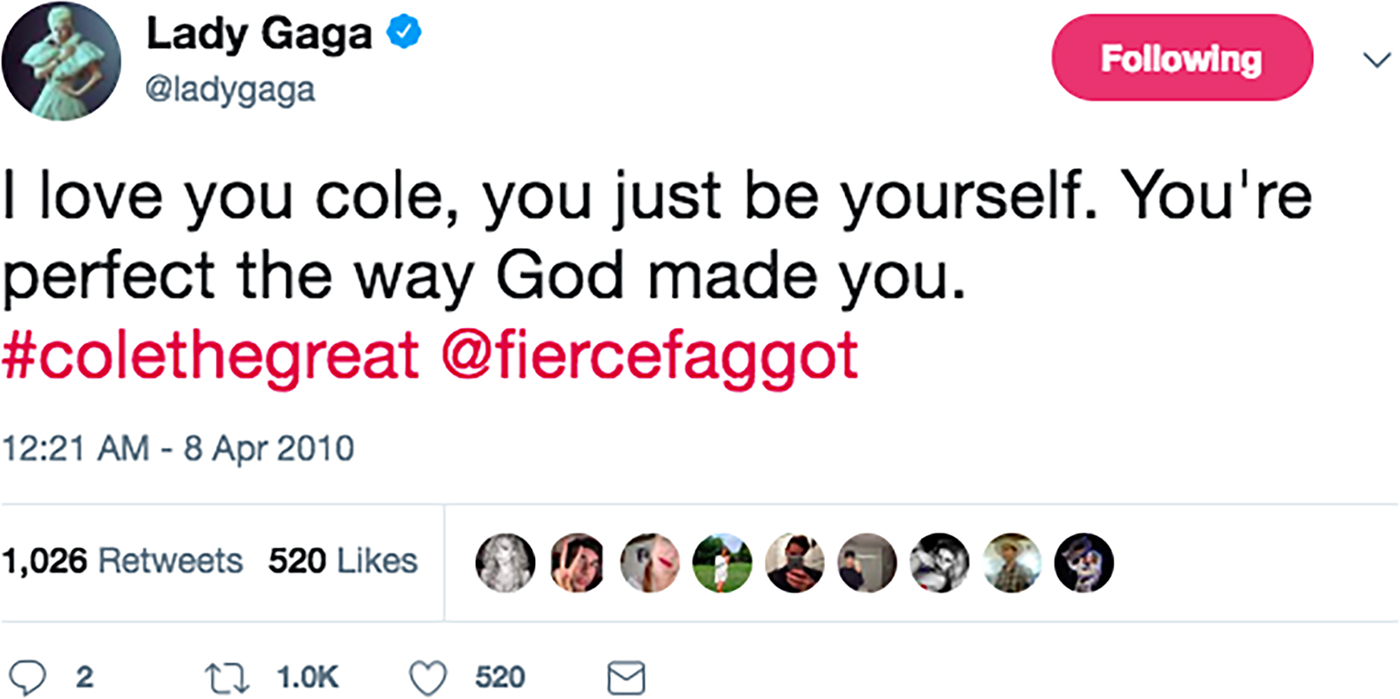

Cases where Lady Gaga uses Twitter posts to directly communicate with fans offer the strongest example of this strategy. One particularly memorable example is the case of Cole Goforth, a high school student from Tennessee who garnered national attention after being sent home from school for donning a shirt that read I Heart Lady Gay Gay. The text of this shirt referred to a joke about Lady Gaga that had circulated on Twitter a few months prior, and was generally accepted by little monsters as a tongue-in-cheek way to refer to Lady Gaga's positive embrace of the gay community. Between April 7 and April 8, 2010, Lady Gaga published a series of tweets referencing this incident, shown in Figures 12–14.

Figure 12. Lady Gaga tweet from April 7, 2010.

Figure 13. Lady Gaga tweet from April 7, 2010.

Figure 14. Lady Gaga tweet from April 7, 2010.

In the three tweets below, Lady Gaga indicates both her awareness of Goforth's situation, and her powerful emotional reaction to his issues. In Figure 14, Lady Gaga seems to directly speak to Goforth—she is proud of him, and she thanks him for wearing his t-shirt in the face of prejudice. Early in the morning of April 8, 2010, Lady Gaga published one last tweet about the incident, shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15. Lady Gaga tweet from April 7, 2010.

This tweet is the most remarkable of the set—here, Lady Gaga directly ‘speaks’ to a fan, by @-ing them. Rather than speaking to fans as a group, or even speaking about a particular fan indirectly, Gaga references a specific fan's username. Mentioning specific users by @-ing them could be interpreted as signaling a stance of alignment even in cases of Twitter conversation between ‘ordinary’ people. When a celebrity @’s a fan, the stance signaled is indeed one of alignment, but it can additionally be read as more special and exciting. Out of all the millions of Twitter followers that Lady Gaga has, she noticed Cole Goforth, and tweeted directly at him. While not a strategy that Lady Gaga uses often (indeed, it would likely lose some of its force if Lady Gaga could devise some way to directly @ many fans without using up all the hours in her day), it is a powerful one.

Tweets in which Lady Gaga demonstrates an attention to and awareness of fan lives and activities both help construct a stance of relational closeness with her fans—just like your friends in real life, Lady Gaga knows what the topics of conversation are and what is going on in your life—but also lend moral credibility to the adoption of such a stance. By judiciously breaking the assumption of unidirectionality in celebrity talk on Twitter, Lady Gaga shows that all of the work that goes in to cultivating this stance of closeness with her fans is authentic, and comes from a legitimate place of affection and interest.

While Lady Gaga's talk about and to fans on Twitter seems to be primarily geared towards the construction of a stance of relational closeness, her talk to and about media journalists appears to create a more confrontational and argumentative stance. In the following section, I show the linguistic moves that Lady Gaga uses to construct a more antagonistic stance in conversation with media journalists. I also show how this very different stance-taking project ultimately serves the same end as the construction of a personal, intimate stance with fans on Twitter.

STANCES OF DISALIGNMENT IN MEDIA INTERVIEWS

Celebrities give interviews with journalists and other members of the mass media establishment for various reasons, not the least of which being that it provides a way to disseminate authorized information to their fans and others about their public persona and business/artistic ventures in an efficient, wide-reaching manner. During interviews, celebrities are tacitly aligned with a kind of overarching media institution, whose agents (journalists) are specially sanctioned to interact with celebrities and disseminate information about them. Even if the topic of an interview centers on a celebrity's relationship with his or her fans, the context remains highly mediated and distanced from the fans themselves. Fans are only ‘auditors’ of these interactions—present in the discourse, but not active participants (Bell Reference Bell1984). In these cases, journalists and media representatives act as gatekeepers between the ‘ordinary’ social worlds of fans and ‘extraordinary’ social worlds of celebrities. When engaged in mediated conversation with journalists, celebrities are generally expected to enact a stance of polite affability with journalists (perhaps simply as a norm of polite conversation generally, but the expectation remains regardless); when celebrities flout these expectations, it may be interpreted as taking a critical stance towards the institution of mass media or the mechanics of modern celebrity culture (Ferris Reference Ferris2001, Reference Ferris2004; Kurzman, Anderson, Key, Lee, Moloney, Silver, & Van Ryn Reference Kurzman, Anderson, Key, Lee, Moloney, Silver and Van Ryn2007).

In this section, I present excerpts from two media interviews in which Lady Gaga's stance towards the journalists interviewing her is either adversarial, or contradictory and corrective. As I demonstrate below, in adopting such stances towards her media interlocutors, she distances herself from media institutions, and therefore her claim on the elite, separated celebrity social sphere. This, in turn, implies a closer, more positive alignment with ordinary people—her fans. In short, by taking a radically different sort of stance in a different communicative context, Lady Gaga accomplishes the same discursive goals as she does by adopting a stance of relational closeness with her fans through her Twitter usage. Although in interview contexts Lady Gaga is more obviously the ‘animator’ of what is said than she is on Twitter, whether she is the ‘author’ or ‘principal’ of the speech is just as vague and indeterminate (Goffman Reference Goffman1981)—we do not know whether interview questions had to be pre-approved, whether her answers were planned and rehearsed, and so on. As her ethos of self is consistent across these contexts and indeterminate participation frameworks, it strengthens the claim that her celebrity persona is ‘authentic’.

“I'm just a rock star”

The first interview analyzed occurred on July 30, 2009, in which Norwegian journalist Gjermund Jappee discussed themes of sexuality in Lady Gaga's work.

(1) GJ: Gjermund Jappee, LG: Lady Gaga2

1 GJ: uh also also in your in your videos ((at least)) Poker Face directed by Ray Kay

2 h-has a strong sexual undertone? h- how important in your (.) artistry i- is is that

3 is the sexuality?

4 LG: .hh it's as important to me as it is to you. isn't sex important to everyone

5 GJ: probably is (.) a- are you scared though that uh having sexuality references c-

6 can it undermine the music? be- because the sexual references l- lot of people

7 only focus on that [((image))

8 LG: [I'm not scared are you scared?

9 GJ: no .hh .hh

10 LG: cause I'm not scared

11 GJ: no? cause you you're not worried that they'll (.) um just uh check out the

12 sexual references a- and not care about the music is that something that bothers you?

13 LG: no (.) not at all I've got three number one records and I've sold almost four

14 million albums worldwide

15 GJ: s-s-so what's the biggest thrill of your career so far?

16 LG: .hh the gay community.

17 GJ: oh (.) wow (.) why can you elaborate on=

18 LG: =cause I love them so much (.) cause they don't ask me questions like that.

19 GJ: .hh .hh

20 LG: cause they love sexual strong women who speak their mind (.)

21 you see if I was a guy (.) and I was sitting with a cigarette in my hand

22 grabbing my crotch and talking about how hh. I make music cause I

23 love fast cars and fucking girls (.) you'd call me a rock star (.) but when I

24 do it in my music and in my videos (.) because I'm a female (.) because I

25 make pop music (.) you are judgmental (.) and you say that it is uh um hh.

26 distracting (.) I'm just a rock star

While interviews with political figures often carry the expectation of a combative dialogue between interviewer and interviewee (Clayman & Heritage Reference Clayman and Heritage2002), celebrity interviews are more frequently seen as light-hearted ‘fluff’ (Ferris Reference Ferris2001; Kurzman et al. Reference Kurzman, Anderson, Key, Lee, Moloney, Silver and Van Ryn2007), where the stakes are lower and Gricean cooperativeness is more easily maintained (Jurker Reference Jurker1986). One of the most striking aspects of this interview is how utterly uncooperative Lady Gaga is with Jappee. This is evident in several places: through a dismissal of his opening question as imprecise (line 4), a redirection of a question for her back to him (line 8), and an implication that Jappee asked a bad question (line 18). These moves strongly key (Goffman Reference Goffman1974) Lady Gaga's stance towards Jappee as disdainful. She also seems to take an argumentative, corrective stance in lines 13–14, when she responds to a reframing of the question “are you worried people will only check out sexual references in your art and not focus on the music?” by responding with details about how successful she is in terms of album sales—implying that not only is there no need for such a worry, it is a bit stupid for him to wonder about it at all. Similarly, in lines 18–26, Lady Gaga explains why “the gay community” has been “the biggest thrill of [her] career”: the answer is that they don't ask ridiculous “judgmental” questions like Jappee has done. Although there is the potential for some cross-cultural misunderstanding here with respect to the precise meaning of politeness, Jappee's nervous laughter (line 9, 19), stuttering (line 15), and his allowance of Lady Gaga's interruption (lines 17–18) indicate that he was indeed caught off guard by Lady Gaga's brash responses.

Through these impolite responses, Lady Gaga constructs an adversarial stance towards her interviewer. In addition to this stance, she also constructs a stance of alignment with a particular subgroup of fans. When Lady Gaga responds to Jappee's question in line 15, “what's the biggest thrill of your career so far?”, Lady Gaga's immediate response (line 16) is “the gay community”, and goes on to describe how they love her overtly sexual style (line 20), implying through the rest of her answer that they wouldn't be so stupid as to ask the kinds of questions that Jappee asked. This stance of alignment with a group of fans—and, by extension, ordinariness—puts her stance in conflict with the mass media institution—and therefore, the extraordinariness of celebrity, despite adopting a very ‘rock star’ style and attitude in this interview.

“It's not a character”

In a December 21, 2009 interview with American MTV News correspondent James Montgomery, Lady Gaga was asked to explain her celebrity persona.

(2) JM: James Montgomery, LG: Lady Gaga

1 JM: s- so I'm interested in the idea of Gaga sort of y you know th- the cha-

2 the character I don't know if that's even I don't mean that in a derogatory

3 way but do you have to sort of get yourself in to a space to be Gaga

4 all the time or [has it has it sort of become like=

5 LG: [no (.) =do you have to get yourself

6 into a space to be [yourself all the time?

7 JM: [but well I I I don't really I mean but n the reason I ask

8 is also is because I st- spoke to you on the phone like a year ago (.) you

9 were at a nail salon (.) in Belfast (.) and you were talking about what

10 you wanted to accomplish with your album and you said these

11 things about (.) something you wanted to make pop this sort of

12 cultural thing and I think the quote was something like you

13 wanted to see kids crowding into times square just to touch the

14 fingernail of a pop star something like that you know?=

15 LG: =yeah=

16 JM: =and it seems like you've done that in a sense and I'm interested

17 you know do you think that is sort of Gaga the character people

18 are responding to or is it the music I mean=

19 LG: =I'll tell you what you're responding to (.) first of all when

20 I'm backstage I never speak with anyone (.) I am uhh a very very

21 focused performer and when I'm working I care about nothing else

22 than changing the lives of the audience .hh so (.) I don't drink

23 before shows I don't uh distract myself I'm very focused and .hh uh

24 no it's not a character but what it is is it's a devotion and a loyalty

25 to the music and .hh preparing myself for the moment so that I

26 may fully be free and fully give myself to the audience

In this interview, while Lady Gaga is noticeably less confrontational and argumentative than in her interview with Jappee, she does continue to construct a general stance of disalignment with Montgomery, and with media institutions. As in her interview with Jappee, we see her turning questions that she sees as poorly formed back on the interviewer (line 5–6), forcing Montgomery to stumble over a lengthy explanation to correct himself (lines 7–18). Once he finally manages to explain what he meant by his original question, he appears to be wrapping up his turn, although the I mean at the end of line 18 could also signal a desire to hold the floor, in which case Lady Gaga's entrée in line 19 could be considered an interruption. When Lady Gaga begins her turn, via interruption or not, she indicates that she won't be responding to the question Montgomery actually posed, but rather to a reframed version of the question—she'll tell Montgomery what “[he] is responding to”, not what the fans are “responding to”, as posited in his question (lines 17–18) (cf. Goffman's (Reference Goffman1981) ‘faultables’).

These moves construct what I call a corrective, contradictory stance. Again, although she does not appear as openly disdainful of Montgomery and his questions, she still frames his questions as unsatisfactory and in need of some editing, on her part, before she can respond. The argument that such a stance positions her in disalignment with media institutions and, in turn, alignment with her fans is perhaps less obvious here based on the rhetorical/conversational moves taken here, but the content gives us additional clues. Lady Gaga speaks of “[caring] about nothing else than changing the lives of the audience” (lines 21–22), and of “fully [giving myself] to the audience” (line 26). This last line in particular harkens back to the stance-taking strategies Lady Gaga uses on Twitter to frame her fans as co-creators of her work, and to metaphorically merge their identities with her own. Paired with the not-entirely-cooperative conversational moves described above, this sort of language clearly indicates who Lady Gaga is invested in during this exchange. It certainly is not Montgomery, or MTV, or the journalists seeking to parse her unusual celebrity persona: it is her fans, who represent an authentic and emotional understanding of who she is as an artist.

In each of these excerpts, Lady Gaga (indirectly) asks interviewers to reflect on an irrealis situation—in Jappee's case, ‘what you would do and say in this interview if I were a male rock star’; in Montgomery's, ‘what do you really mean when you ask about my “character”’. This move is reminiscent of the sort of phenomena described as shadow subjects (Taha Reference Taha2017), or shadow conversations (Irvine Reference Irvine, Silverstein and Urban1996). In the imagined discursive settings that Lady Gaga constructs for her journalist interlocutors, she is not only able to further elaborate a stance of (some kind of) disalignment with the journalists and the media institutions they represent, but is able to clearly bring her fans in as discursive subjects that the journalists are prompted to see as ideal actors. In excerpt (1), gay fans are presented as people who would ask better, more interesting questions than Jappee due to their evolved gender ideologies. In excerpt (2), fans are presented as ideologically pure audience members, seeking contact with Lady Gaga only due to the ‘authentic’ emotions her work brings out in them, rather than a nitpicky, analytical journalist, seeking to lift up the curtain and reveal some nonartistic, ‘true’ self of Lady Gaga. In audience design terms, the shadow subjects that Lady Gaga creates here could be seen as a way to reposition the role of fans from overhearers to auditors (Bell Reference Bell1984).

These two excerpts from interviews with media journalists reveal Lady Gaga's stance of diaslignment with the media institution, and the social divide between fans and celebrities that it both encodes and represents. To do this, Lady Gaga engages in a range of conversational moves that construct stances that are adversarial, contradictory, and corrective. These moves allow her to demonstrate her lack of affiliation with the traditional fan-celebrity moral order, and therefore an alignment with a shifted, re-envisioned moral order that puts her fans on an equal social standing with herself. Because she is willing to reject the (norms of) institutions that privilege celebrities over fans, namely by behaving so openly aggressive to and noncompliant with the usual interactional orders of celebrity interviews, Lady Gaga's claims about her special and close relationships with her fans can be seen as more than ‘just talk’. Although the stance-taking strategy that Lady Gaga adopts in media interviews is so radically different from the strategy she adopts on Twitter posts, she achieves the same discursive ends: creating a persona that appears to be authentically aligned with her fans.

DISCUSSION

Marshall (Reference Marshall1997) has illustrated how, particularly for pop music stars, the execution of a credibly ‘authentic’ public persona is crucial to a star's commercial success. Even if Lady Gaga herself would disavow this perspective, it is undeniable that by cultivating such a dedicated fan base through her strategies of alignment with them, she is also securing her own economic well-being. Here, we begin to see how, despite all of the linguistic work she does to reshape the moral order separating ‘extraordinary’ celebrities from their ‘ordinary’ fans (Ferris Reference Ferris2004), Lady Gaga continues to benefit from the privileges associated with celebrity status. Despite occasional invitations to transgress the boundaries of this moral order (e.g. the tweet shown in Figure 6), ultimately, Lady Gaga remains socially and physically separate from her fans. In addition to the luxury clubs, restaurants, and hotels she patronizes, her public appearances make use of several material means of distinguishing the ‘extraordinary’ sphere from the ‘ordinary’. At meet-and-greet opportunities, autograph signings, and concerts, Lady Gaga is separated from fans via metal barriers, surrounded by a coterie of body guards, and is driven off in cars with tinted windows. While some of these actions are no doubt driven by safety concerns, they also still clearly mark her as a member of an elite social sphere.

Two scenes from the Netflix-produced biographical documentary, Gaga: Five foot two (Mourkabel Reference Mourkabel2017) illustrate this clash between ‘ordinary’ and ‘extraordinary’. In one scene, Lady Gaga drives past a local school, convertible top down. As she passes a school bus, she remarks, “They probably don't even know who I am. They probably think I'm just some crazy old lady who lives down the street”. Later in the documentary, Lady Gaga goes to a local WalMart to purchase copies of her latest album. Although the sales associates don't recognize her at first, soon a crowd begins to form with workers and shoppers alike asking her for a selfie. Like the Geri Halliwell documentary that Tolson (Reference Tolson2001) analyzes, this is not a project of doing being ordinary, but of illustrating the constraints that prevent celebrities from being ordinary, much as they might like to be. These scenes, as well as the rest of the documentary—in which we see her health struggles, break-ups, visiting family, and frustration with the 2016 presidential election—reminds her fans that even if the boundaries of the moral order must be maintained, on the other side of it, she really is just like them.

CONCLUSION

The analysis in this article has shown that Lady Gaga's engagement in stance-taking towards her interlocutor(s) differs based on her audience and the communicative platform she uses. On Twitter, stances of alignment are constructed with her fans through the use of intimate relationship terms, inclusive pronoun choice, and by directly responding to fan comments. In contrast, during interviews with journalists, she constructs stances of disalignment with media professionals through strategies such as critique, dismissal, and reframing of journalist questions, as well as more generally refusing to engage in the polite, cooperative question-response format of typical celebrity interviews (Jurker Reference Jurker1986). Like Texas politician Barbara Jordan, Lady Gaga refuses to allow her interviewers to co-negotiate meaning with her and avoids building rapport with them by remaining distant and cold, creating a persona that sounds ‘formal, precise, and careful’; quite different from the ‘audience-centered, rapport-building’ style (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2009:39) she uses when speaking to fans on Twitter. These different approaches to stance-taking, depending on audience and medium, function together to help craft a perception of Lady Gaga as a morally credible, ‘authentic’ celebrity. By showing overt alignment with her fans through Twitter, and indirect alignment with her fans through disalignment with the elite gatekeepers of media institutions, Lady Gaga produces an ethos of self that is both consistent and morally credible (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2009). With her attitude towards her fans remaining noticeably the same across discourse contexts, Lady Gaga can felicitously claim an ‘authentic’ celebrity persona.

Within the broader context of Lady Gaga's fame, this felicitous claim to authenticity is surprising. Ferris’ work suggests that discouraging adherence to the fan-celebrity moral order creates the possibility for Lady Gaga to be viewed as attention-hungry and, therefore, morally not credible and inauthentic (Ferris Reference Ferris2004:258), or as someone who ‘panders’ to her fans. Similarly, her outlandish and sometimes simply ridiculous fashion and performance styles (including, but not limited to, the infamous ‘meat dress’), as well as the complete stylistic revamp she typically undergoes with the release of each album, have often earned her criticism in the mainstream media for being ‘fake’ or ‘trying too hard’—both ostensibly death knells for claims to authenticity. Yet, as Dilling-Hansen's (Reference Dilling-Hansen2015) research shows, fans continue to see her as personally and authentically invested in the relationship they share with her. As I have argued above, this enduring perception of authenticity is due, at least in part, to stancetaking strategies that Lady Gaga uses to speak to and about her fans. Unlike other celebrities, who use techniques of civil inattention (Goffman Reference Goffman1972) and doing being ordinary (Sacks Reference Sacks and Atkinson1985, Tolson Reference Tolson2001) to authenticate (Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2003) their public personae, Lady Gaga maintains her utterly unordinary creative style as well as a morally credible ethos of self by engaging in stancetaking moves that highlight her alignment with her fans above all other audiences.

In the context of modern celebrity, ordinary forms of ‘ordinariness’ are impossible. To achieve the sense of authenticity that Marshall (Reference Marshall1997) argues is key to economic success, then, pop stars must develop other strategies for constructing this kind of persona. This work offers insight into how public figures—not just pop stars, but actors and models and politicians—can utilize stance to construct viable public personae, as well as how stancetaking can reshape and redefine the moral orders of public spheres more broadly. Although many regard celebrity culture as frivolous and vapid, the data presented here show that in fact a complex array of linguistic and semiotic strategies are needed to produce a public persona that is readable as ‘authentic’. It helps us understand when a strongly agent-driven interpretation of stance is appropriate, and how such a view of stance leads to a particular understanding of linguistically constructed authenticity.

APPENDIX: TRANSCRIPTION CONVENTIONS

- (.)

pause

- -

abrupt stop in speech

- =

latching

- .hh

exhalation

- hh.

inhalation

- ?

question/rising intonation

- ((words))

uncertain transcription

- [

overlap