INTRODUCTION

Studies on various languages have demonstrated that the design of repetitions, particularly prosody, has the potential to differentiate among a range of social actions and interactional functions that can be implemented through other-repetition: checking a candidate hearing, requesting a clarification, challenging what has been said, registering receipt of new or revised information, and so on (e.g. Kelly & Local Reference Kelly and Local1989; Selting Reference Selting, Couper-Kuhlen and Selting1996; Schegloff Reference Schegloff1997; Svennevig Reference Svennevig2008; Robinson Reference Robinson, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013; Benjamin & Walker Reference Benjamin and Walker2013; Persson Reference Persson2015b; Rossi Reference Rossi2015). This research shows that actions implemented by other-repetitions appear to ‘cluster’ around some recurrent action-types, which are found across languages and attest to generic functional distinctions (cf. Rossi, introduction, this issue). While each instantiation of an action-type (i.e. each ‘action token’) inevitably involves ultimately unique meanings and nuances associated with locally specific particularities of context and turn-design (Enfield & Sidnell Reference Enfield and Sidnell2017), action-types are useful as analytic heuristics that capture recurrent patterns in interaction, and that provide a basis for comparison, for the purposes of cross-linguistic analyses of action-formation—as illustrated in this special issue. A central issue in research on action-formation generally, and with respect to repetitions in particular, is the interplay of position and composition. Using conversation-analytic and interactional-linguistic methods, this study shows that prosodic composition is indeed central in differentiating among action-types in repetitions in French. Empirical evidence from talk-in-interaction shows the interactional significance of prosodic features and other turn-design features involving grammar and lexis. All of these compositional aspects are relevant for distinguishing among actions accomplished by repetition-formatted turns, and for shaping the sequential trajectory that ensues. That said, the findings of this study do not warrant a straightforward one-to-one mapping between form and function of other-repetitions. This leads us to consider, more closely than in prior research, how the distinctions among various types of repair-initiations and nonrepair actions relate to specific aspects of the talk targeted by repetition.

This study contributes to the general goals of the special issue on several counts. First, it provides an analysis of how different action-types, or interactional functions, are distinguished in French. In this respect, French is typologically unlike some of the other languages represented in this special issue, as it manifests heavy reliance on intonation contour type and pitch span, whereas morphosyntactic resources and particles are more marginally involved. Second, it foregrounds the interplay between position and composition in action-formation. For instance, distinctive roles are identified for some combinations of positional and compositional features, such as a rising contour in repetitions of turns containing negation, and a rising contour in repetitions of turns in which the speaker conveys heightened agency with respect to the propositional content. Third, this study addresses the topic of ‘double-barrelled’ first pair parts (Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007), which establish two distinct relevancies to be dealt with in the response turn, and demonstrates how other-repetitions can come to do such work.

BACKGROUND

The French language

Since repetitions often constitute a type of polar question, it is worth reviewing the various ways in which polar questions can be formed in French, grammatically or prosodically (Mosegaard Hansen Reference Mosegaard Hansen2001; see also Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo, Hirst and Cristo1998:201–205 and Delais-Roussarie et al. Reference Delais-Roussarie, Post, Avanzi, Buthke, Di Cristo, Feldhausen, Jun, Martin, Meisenburg, Rialland, Sichel-Bazin;, Yoo, Frota and Prieto2015:82–83). First, in formal registers, polar questions can be formed through inversion of verb and subject clitic. Second, polar questions may be constructed using the clause-initial interrogative particle est-ce que (lit. ‘is-it that’, derived from grammaticalised inversion). Third, French also has clause-final question tags (e.g. non, hein). Fourth, and importantly, polar questions can be designed as such using intonation (see below). However, intonational marking of questions is not ubiquitous: a corpus study (Fónagy & Bérard Reference Fónagy, Bérard, Grundstrom and Léon1973:95) showed that 37% of grammatical declaratives responded to as questions actually have intonation comparable to that of nonquestioning declaratives. Furthermore, Mosegaard Hansen (Reference Mosegaard Hansen2001) finds that grammatically unmarked questions (regardless of intonation) frequently occur with so-called B-event propositions (see Labov & Fanshel Reference Labov and Fanshel1977), whereas inversion and interrogative particle mostly occur with propositions about other types of events. These findings suggest that epistemics also plays a role (cf. Heritage Reference Heritage2012), but there are no detailed interactional studies investigating how different design features of questions relate to one another, to epistemics, and to sequential organisation.

In terms of phonology, French has ten to eleven ‘full’ oral vowels and three to four nasalised vowels (depending on variety), in addition to a ‘nonfull’ mid-central oral vowel (/ə/). The latter is particular with reference to prosody (see below), and often subject to deletion. As some of the figures here show, syllables may span word boundaries, because word-final consonants are often resyllabified as onsets of the following syllable, when followed by vowel-fronted words.

French prosody

Unlike in other Romance languages, stress in French does not occur in different positions of the word for the purposes of lexical contrast. While sometimes described as consistently word-final, stress (or primary accentuation) in French is more appropriately termed phrase-final, since it falls on the final syllable of an accentual phrase (or stress group) (Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo, Hirst and Cristo1998:196). Thus, word-final syllables are unaccented if occurring medially in an accentual phrase. Primary stress is restricted to syllables that have a full (nonschwa) vowel nucleus, so schwa syllables are unstressed (Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo, Hirst and Cristo1998:196). An accentual phrase can also have a secondary (‘initial’) accent, usually on the first or second syllable of a content word (Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo, Hirst and Cristo1998:197–98).

In autosegmental-metrical analyses of French, the pitch movements associated with the primary accent (or the last primary accent, if there are several) and with the phrase-final boundary tone occurring after the primary pitch accent, form an inventory of categorically distinct intonation contours, or nuclear configurations (see e.g. the F_ToBI model, Delais-Roussarie et al. Reference Delais-Roussarie, Post, Avanzi, Buthke, Di Cristo, Feldhausen, Jun, Martin, Meisenburg, Rialland, Sichel-Bazin;, Yoo, Frota and Prieto2015:98–99). These contour-types are used distinctively in French for pragmatic purposes, in addition to any gradient prosodic variations (pitch span, register variation, etc.). Questions are regularly formed through intonation: declaratives with a nuclear rise (H* H% in F_ToBI) is typically cited as a common, even default, way of designing polar questions (Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo, Hirst and Cristo1998:201–202; Delais-Roussarie et al. Reference Delais-Roussarie, Post, Avanzi, Buthke, Di Cristo, Feldhausen, Jun, Martin, Meisenburg, Rialland, Sichel-Bazin;, Yoo, Frota and Prieto2015:82–83).

Few interactional studies have investigated prosody as a resource for social action in French. One general finding from the available work is that intonation contour types indeed can differentiate between distinct actions with diverging sequential projections, in turns with otherwise comparable turn-design. This has been demonstrated for a few turn-types, including formulations (Persson Reference Persson2013) and other-repetitions (Persson Reference Persson2015a,b; also de Fornel & Léon Reference de Fornel and Léon1997).

Other-repetitions

As mentioned, prosody has the potential to differentiate among various social actions that can be implemented through other-repetition. For French, Persson (Reference Persson2015b) found that registering repeats (which make confirmation optionally relevant) have a globally falling contour, with prominent (high) initial accents and low final accents. Repair-initiating repeats, which elicit confirmation and possibly more talk to remediate interactional trouble, instead have prominent (high) final accents. These findings are further developed and specified here.

In traditions primarily concerned with elicited or read speech, utterances resembling other-repetitions are analysed under the term echo questions or echo yes/no questions (for analyses of French, see e.g. Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo, Hirst and Cristo1998:205; Delais-Roussarie et al. Reference Delais-Roussarie, Post, Avanzi, Buthke, Di Cristo, Feldhausen, Jun, Martin, Meisenburg, Rialland, Sichel-Bazin;, Yoo, Frota and Prieto2015:85–87). However, echo yes/no questions are typically not defined as verbatim repetitions. Delais-Roussarie and colleagues (2015) describe them as having declarative form, so echo questions may be, for example, declarative clauses recycling material from preceding phrase-formatted utterances (as in the following, where B has asked for the time: A: une heure ‘one o'clock’ B: il est une heure? ‘it's one o'clock?’), or quotation-framed repeats (vous avez dit qu'il est une heure? ‘did you say it's one o'clock?’). Smith (Reference Smith2002) uses the label ‘echo questions’ for all declarative-formatted questions in French. In terms of marking questionhood, several authors note that echo questions are typically formed without subject-verb inversion or the interrogative particle (Mosegaard Hansen Reference Mosegaard Hansen2001:465; Delais-Roussarie et al. Reference Delais-Roussarie, Post, Avanzi, Buthke, Di Cristo, Feldhausen, Jun, Martin, Meisenburg, Rialland, Sichel-Bazin;, Yoo, Frota and Prieto2015:83), suggesting an important role for prosody.

One issue in noninteractional linguistic studies of echo questions, pointed out by Kelly & Local (Reference Kelly and Local1989:277), is that such discussions do not relate echo questions to other repeat-formatted utterances, such as registerings and displays of recognition. Moreover, if echo questions are understood as variously expressing uncertain hearing, noncomprehension, surprise, disbelief, and disagreement (cf. Delais-Roussarie et al. Reference Delais-Roussarie, Post, Avanzi, Buthke, Di Cristo, Feldhausen, Jun, Martin, Meisenburg, Rialland, Sichel-Bazin;, Yoo, Frota and Prieto2015:85–86), less emphasis is placed on teasing apart these distinct purposes—a task taken up here. However, Delais-Roussarie and colleagues (2015:85–87) do find that both rising-falling (H* L%) and rising (H*H%) contours occur—with distinct functions—in French echo questions: rise-falls convey no specific epistemic or attitudinal stance, whereas rises express incredulity or disagreement. It is true that these findings may not be strictly comparable with those of the present study, since echo questions are not always repeats, and vice versa; furthermore, findings for elicited speech may or may not be borne out for naturally occurring interaction.

DATA

The data include audio-recordings of telephone interaction (twenty hours), and video-recordings of face-to-face interaction (eleven hours). In addition, a smaller portion of the collected repetitions (18%) comes from audio-only recordings of face-to-face interaction (four hours). The recordings include both everyday conversation (eight hours) and institutional interaction (twenty-seven hours, from various settings: radio phone-in shows, calls to university departments, service encounters in bakeries and cheese shops, guided tours, and various workplace interactions). Data sources include the CLAPI databaseFootnote 1 and the UBS/OTG corpora (Nicolas, Letellier-Zarshenas, Schadle, Antoine, & Caelen Reference Nicolas, Letellier-Zarshenas, Schadle, Antoine and Caelen2002), among others. Unsurprisingly, the telephone data are primarily dyadic, whereas both multi-party and dyadic interactions are well represented in the face-to-face data. The recordings were predominantly made in various parts of France, but a few recordings were made in Belgium and Switzerland. The core collection contains 203 cases. The target phenomenon ‘other-repetition’ is understood as replication (either verbatim or with limited modification, e.g. deictic shift, pronominalisation, word order changes, or addition of particles/adverbials/pronouns) of verbal material produced by someone else, designed to problematise or otherwise engage with the first saying, thus making some response conditionally or optionally relevant. The delimitation of the phenomenon, and the conceptual and analytic framework, are thoroughly discussed by Rossi (introduction, this issue).

In the transcribed extracts, the original French is presented along with a fairly idiomatic translation, and morpheme glosses where relevant. Pitch data are represented as traces of fundamental frequency (manually corrected and scaled to speakers’ approximate ranges) rather than Jeffersonian notation, since pitch is distributed over whole turns, rather than occurring only at specific points. The phonological analysis of the intonation contour inventory draws on F_ToBI representations (Delais-Roussarie et al. Reference Delais-Roussarie, Post, Avanzi, Buthke, Di Cristo, Feldhausen, Jun, Martin, Meisenburg, Rialland, Sichel-Bazin;, Yoo, Frota and Prieto2015). In figures, syllable boundaries are displayed on the phonetic transcription tier, and word boundaries on the orthographic tier.

STRUCTURE OF OTHER-REPETITION SEQUENCES

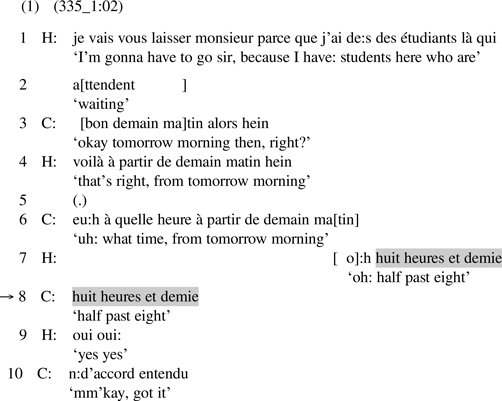

Extract (1) serves to illustrate some key notions and issues concerning other-repetition sequences. In this call to a university, the call-taker H has previously explained that the person that C is seeking will not be available until the next working day.

Here, the original turn (line 7) is a second pair part. In the repetition turn (line 8) in next-turn position, C launches a postexpansion by checking understanding, and with the response turn (line 9) H merely confirms the understanding. Next, C produces a form of the acceptance token d'accord ‘okay’, and the perfect participle entendu (lit. ‘heard/understood’) to explicitly claim receipt of the time reference, and the instructions to which the time-giving is tied. The fact that acceptance is overtly done only after H's confirmation shows that C designed his repeat to check understanding (rather than display understanding).

Having established the basic structure of other-repetition sequences, the following sections account for how repetition turns come to implement particular actions. Special attention is paid to constructional aspects including prosody and grammar, and contextual aspects including sequential environment and epistemics. First, we focus on actions dealing with problems of hearing and understanding, including confirmation-requests (illustrated by extract (1)).

OTHER-REPETITIONS DEALING WITH PROBLEMS OF HEARING AND UNDERSTANDING

Requesting completion

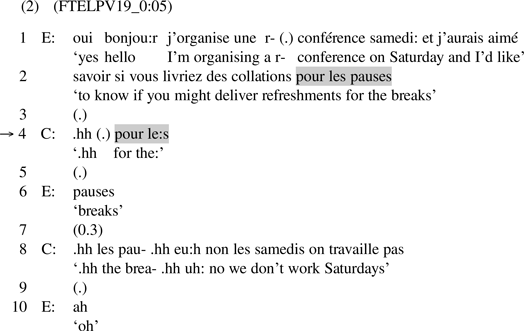

One distinct use of other-repetitions for repair-initiation is hanging repeats: repetitions of a hearably incomplete part of the prior turn, designed for requesting completion (Persson Reference Persson2017a:239–40; cf. Rossi Reference Rossi2015:274–75). Here, a repair-solution is elicited in the form of a redoing of the trouble-source, to which the incomplete repetition leads up. The left-out trouble-source is thus presented as not heard, or as possibly misheard. Extract (2), where E is calling a catering service, illustrates this practice.

C's repetition (line 4) is not only partial, but syntactically incomplete: it ends in the plural definite article les, projecting a noun. In this instance, E's response turn (line 6: pauses) is the direct completion of the repeated portion of the original turn; elsewhere, the response turn also includes (part of) the lead-up (so that E's response would be les pauses or pour les pauses). Another instance of a hanging repeat occurs in extract (8) (line 7).

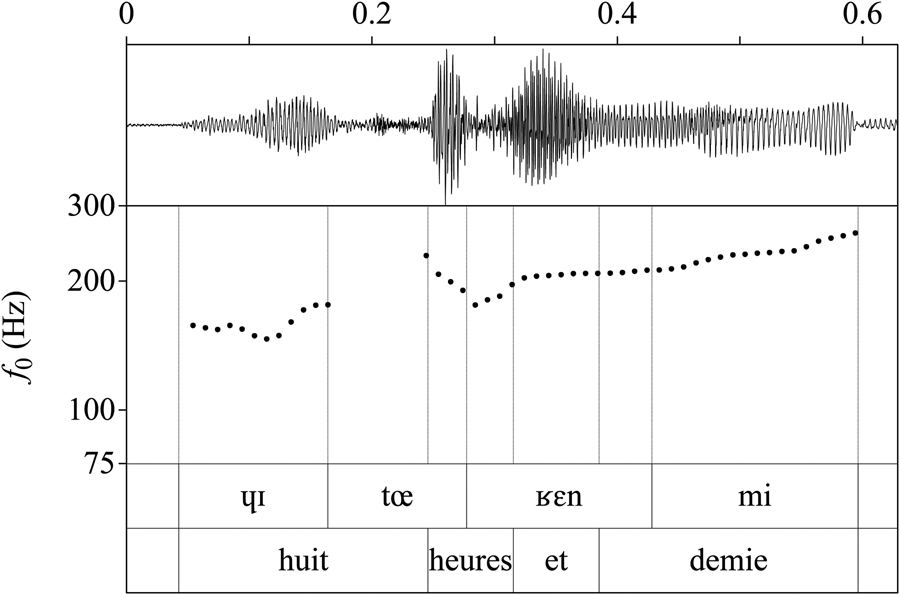

Hanging repeats are typically done with a rise-from-low contour (L* H%). This contour takes two slightly different forms depending on prosodic context: if there is a phrase-final primary accent on the penultimate syllable (in addition to the turn-final accent), the last syllable has a pitch fall/downstep followed by a rise; if not, the contour has a rise that begins late in the accented syllable, typically some way into the vowel; see Figure 1 (in such cases the contour could be more transparently described as a late rise). The vowel of the turn-final accented syllable may also have noticeably greater lengthening, compared with other turn-final accented syllables. Alternatively, the primary accent may be followed by an unstressed schwa syllable, with pitch at least as high as the primary accented syllable. The realisation of final schwa (generating a post-accentual syllable) in fact appears to be favoured by the rise-from-low contour, compared with other contours. Besides hanging repeats initiating repair, the rise-from-low pitch contour is also used for other ‘fill-in-the-blank questions’, that is, completion-eliciting incomplete utterances (Persson Reference Persson2017a), and increment elicitors. This provides further evidence of the functionally distinct role of this contour in French.

Figure 1. Pitch trace for line 4, extract (2).

In extract (2), the incompleteness of what is repeated is conveyed both intonationally and syntactically; in other instances, incompleteness may not be syntactic but pragmatic (e.g. when the first part of a telephone number is repeated); and in yet other cases the intonation contour may be the only cue to incompleteness.

Hanging repeats typically get responses that merely fill in the blank. This seems to distinguish this practice from the repair-initiating formula [incomplete repeat + wh-word] (as in pour les quoi ‘for the what’), which instead often occasions reworking of the trouble-source, for example, clarifications or specifications (Persson Reference Persson2017a:239–40). Thus, with hanging repeats, the tacit claim that comes with virtually any repair-initiation—that there was something ‘not quite right’ with the trouble-source turn (Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007:151)—appears to be neutralised: repeat-speakers present the problem as one of hearing (and thus lying with the hearer), thereby assuming responsibility for the breakdown in intersubjectivity (see also Persson Reference Persson2017a:239–40).

Requesting confirmation

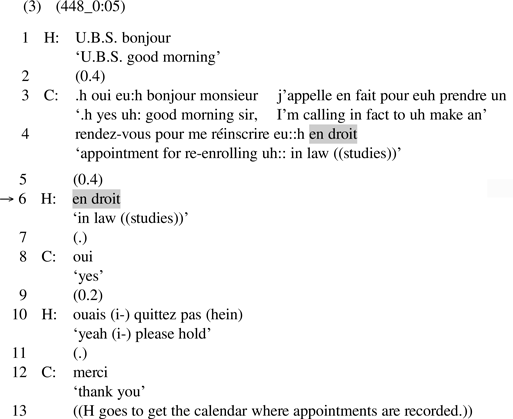

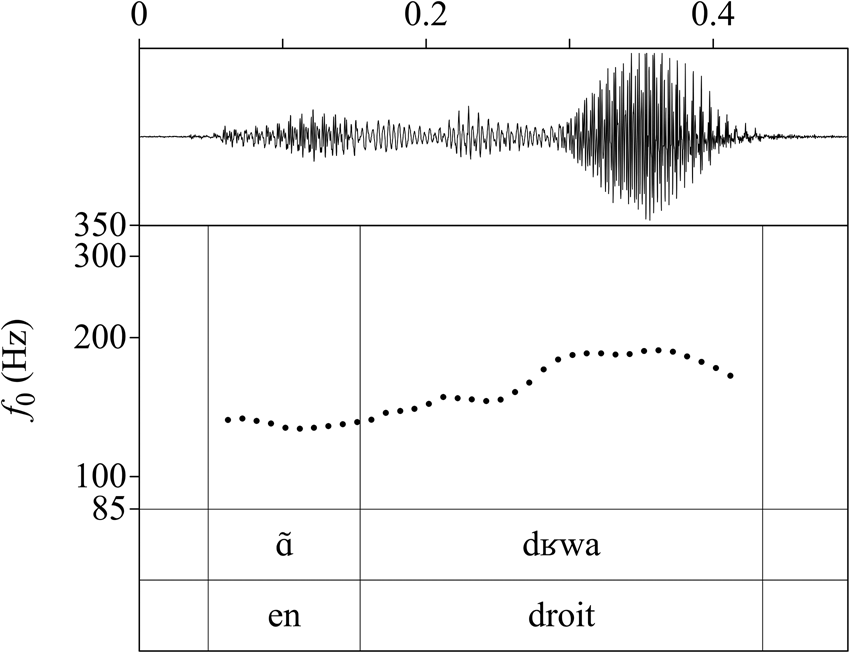

Participants regularly deploy repeats for checking that they ‘got’ what was said in the original turn, as illustrated in extract (3) (and extract (1)). Extract (3) is from a call to the faculty of law at the University of Southern Brittany, UBS. Unlike in extract (1), here the original turn is a first pair part.

H produces the repetition (line 6) with a rise contour (H* H%): despite the microprosodic effects of the consonants, Figure 2 shows that the rise is aligned with the onset of the primary accented second syllable (earlier than in the L* H% contour). The repetition is responded to with a confirmation token only (line 8). Nothing in the talk or the context suggests that H is doing something more complex than merely seeking confirmation that the repeated talk is an accurate hearing or understanding of what C said: there is nothing a priori remarkable about law studies in this institutional context, and confirmation is treated as sufficient, as H begins to respond to the initiating action implemented by the original turn (line 10).

Figure 2. Pitch trace for line 6, extract (3).

In many straightforward repair sequences such as extracts (1) and (3), it is hard to pinpoint the cause of trouble precisely (e.g. audibility or recognisability of referents). What is most central is that these repair sequences are satisfactorily solved by mere confirmation. That said, in some confirmation-requests in the collection, audibility issues are highly plausible (e.g. due to overlapping talk, ambient noise, or disturbances on the telephone line). Furthermore, there are cases of ‘would-be repetitions’ that are actually mishearings, and that get responded to with correction (cf. Schegloff Reference Schegloff1997:525–26), which implicitly disconfirms and repairs the candidate hearing. In such cases, hearing is likely to be an issue for the repeat-speaker too (although there may be additional issues), and these ‘would-be repetitions’ are indeed implemented as requests for confirmation.

Repetitions requesting confirmation are overwhelmingly done using the rise contour, as in extracts (1) and (3). The pitch trace for C's repetition in extract (1) is given in Figure 3: after a pitch upstep from the first to the second syllable, the (vowels of the) second and third syllables have similar pitch height, and the (narrow) final rise begins during the [m].

Figure 3. Pitch trace for line 8, extract (1).

Generally, the rise contour involves a primary accent that is rising and/or has a pitch upstep (especially when the primary accented syllable has a voiceless onset). At the very end of a rise contour there may be a slight fall, and when the primary accented syllable is followed by a postaccentual schwa syllable, the latter typically has falling pitch (unlike in the rise-from-low contour).

In intonational phonology, the French rise contour is often analysed as the default contour for polar questions, which are by definition confirmation-seeking (Delais-Roussarie et al. Reference Delais-Roussarie, Post, Avanzi, Buthke, Di Cristo, Feldhausen, Jun, Martin, Meisenburg, Rialland, Sichel-Bazin;, Yoo, Frota and Prieto2015:83). At a very general level, this is consistent with the function of the rise contour illustrated here. However, which specific type of response an other-repetition elicits also hinges on various verbal, epistemic, and sequential factors, as demonstrated in the following sections.

Requesting clarification or specification: Indicating problems of understanding

For lexical or referential trouble-sources, French speakers appear to rely mainly on repair-initiating wh-questions, which are outside the scope of this study but may still involve partial repeats, such as c'est quoi X ‘what is X’ where X is the repeated trouble-source (cf. Golato & Golato Reference Golato and Golato2015). These formats verbally diagnose the problem as one of understanding, thus seeking clarification or specification.

However, French speakers may also indicate problems of understanding through other-repetition alone. On the surface, these repeats appear to be confirmation-seeking just like those analysed in the previous subsection. However, in these cases, requesting confirmation is only one layer of a more complex repair-initiating action. Whereas confirmation-seeking repeats are adequately and sufficiently responded to with just confirmation, clarification-seeking repeats are ‘double-barrelled’ (Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007) and make relevant [confirmation + clarification], where the clarification may amount to, for example, an alternative or more specific reference, or explanatory informings. In clarification-seeking repeats, confirmation is treated as normatively expectable in the first slot of the response turn, but not as sufficient response, since the second slot should be occupied by clarification (cf. Raymond Reference Raymond, Reed and Raymond2013). The work of the repeat may thus be glossed as: ‘Is this what you said? And if so, explain it!’.

Similarly to confirmation-seeking repeats, clarification-seeking ones are produced with the rise contour, usually with nonexpanded pitch span. In the collection, using other-repetition for implementing requests for clarification appears to rely on either (a) the original turn containing negation, or (b) the need for clarification/specification being inferable from the repeat-speaker's predictable lack of epistemic access to the problematic reference or expression. Here, the position-composition interplay is apparent: repetition design features help establish the first response relevancy (confirmation) and positional aspects the second (clarification). The two conditions (a) and (b) are treated in turn below.

Condition (a): Original turn involves negation

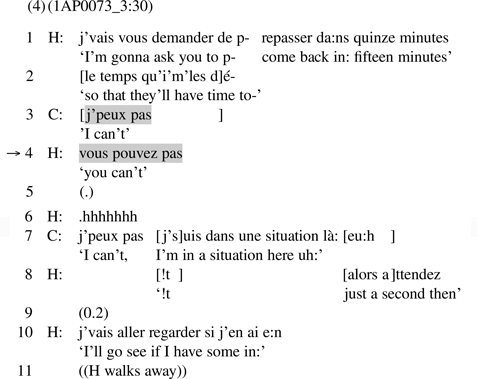

When the original turn is negatively framed (and the negation is kept in the repetition), the repetition mobilises responses composed as [confirmation + clarification], that is, confirmation with negative polarity followed by clarifying, specifying, or other explanatory talk. This is illustrated in extract (4), from a tourist information centre. The customer C has requested a relatively large number of city maps.

Prior to this, H has explained that their stock of maps is probably not sufficient to accommodate C's request, and the back office staff will need to make additional copies. In lines 1–2, H asks C to allow for some time for that. In overlap, C rejects on account of being unable (line 3), and at line 4, H repeats C's turn with a rise contour (Figure 4)—after the voiceless onset of the final syllable, there is a slight upstep and a rise, together spanning 4 4 semitones (the whole turn spans 7 semitones). After some delay (lines 5–6), C responds with repetitional confirmation (line 7) followed by an attempt at clarification of her circumstances, albeit elliptical and rather uninformative.

Figure 4. Pitch trace for line 4, extract (4).

Negative assertions, stating that something did not happen or is not the case, have been shown to serve the accomplishment of negatively valenced actions, in particular complaints (e.g. Schegloff Reference Schegloff, Drew and Wootton1988; Jacoby & Gonzales Reference Jacoby, Gonzales, Ford, Fox and Thompson2002), by way of conveying a failure or some other unfulfilled expectation that is typically morally charged. Against this background, it is unsurprising that, when repetitions of negative assertions are responded to with more than confirmation, such elaborations are often hearable not only as clarifications but additionally as justifications of the position or action conveyed in the negatively formulated trouble-source talk (i.e. the response beyond confirmation functions as an account, in the sense of morally charged reasoning aimed at defending or legitimising some conduct or opinion; cf. Robinson Reference Robinson and Robinson2016:15–16). Such is the case in extract (4), where C in line 7 begins to produce an elaboration to justify her inability account (i.e. line 3), although the elaboration in line 7 remains opaque, as H comes in with a service-focussed proposal (lines 8–10). Thus, H does not treat C's specific reasons as crucial. Even though H does not fully focus on eliciting an account from C, the original turn prefigures a subsequent explication of the negative turn component, and that explication is ‘set off’ through the vehicle action of requesting confirmation.

Negative turn components are often elaborated on, and unelaborated negated talk is regularly treated as problematic (e.g. Ford Reference Ford, Selting and Couper-Kuhlen2001). This also holds here, when response turns begin with confirmation of the negative repetition. Note that the literature has primarily discussed disconfirming (disaligning) negative responses, which are dispreferred actions and therefore frequently accompanied by accounts. By contrast, the pattern discussed here concerns confirming negative responses, since negatively framed repetitions normally require negation to be confirmed. There is no immediately obvious reason why negatively framed confirmations—which are generally aligning—would project elaboration. However, when the negatively framed original turn is taken into the equation, the same principles identified by Ford (Reference Ford, Selting and Couper-Kuhlen2001) explain the heightened relevance of elaboration here: the original turn is an initial unelaborated negative (and disaligning) utterance, and the repetition amounts to a pursuit of elaboration, although by means of requesting confirmation first. Thus, the confirmation satisfies the first, immediate relevancy (of a confirmation), and the elaboration deals with the implications of the confirmation-request within the larger course of action (cf. Raymond Reference Raymond, Reed and Raymond2013). Both position and composition are involved here: a negatively framed original turn does not entail elaborate confirmation in the response turn when the repetition turn is produced with other contours that do not implement requests for confirmation.

Condition (b): Predictable lack of epistemic access

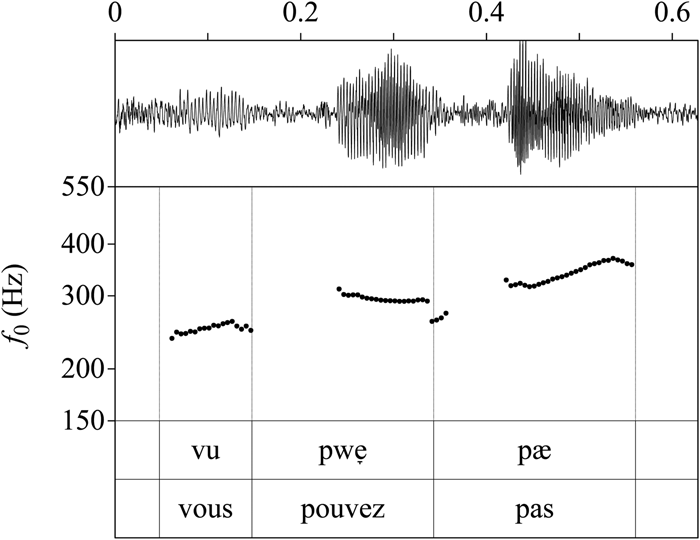

Condition (b) is illustrated in extract (5), from a guided tour of a manor house.

In line 2, G elicits a modifier of the noun machine, further pursued in line 5. The expression resulting from the visitors’ responses (machine à coudre ‘sewing machine’) is implicitly rejected as the ‘right’ answer is given (machine à broder ‘embroidery machine’), in a turn where G also comments on her deliberately misleading questioning (lines 9, 11). H repeats the modifier (line 13) with a rise contour,Footnote 2 thus inviting confirmation. The response turn (lines 15, 17–18) takes the form [confirmation + clarification]. Given that none of the visitors successfully identified the physical object, G has reason to assume that the concept machine à broder is also unfamiliar to H. Thus, what heightens the relevance of clarification here is that H predictably lacks epistemic access (and not merely has lesser epistemic authority than G). Additionally, one could argue that the clarification is a projectable continuation of the original turn; in this activity context, naming an unfamiliar object may prefigure more elaborate commentary. Indeed, the clarification is prefaced by alors ‘so/now’ (line 15), suggesting that some specification was already on the interactional agenda (Bolden Reference Bolden2009b).

Interlocutors’ identification of repeats as clarification-seeking appears somewhat variable: repeats with a rise contour may be treated initially as merely confirmation-seeking, with the trouble being diagnosed as understanding-related only in a second round of repair (Persson Reference Persson2015b:589). Alternatively, the response-speaker may continue (after confirming) by explicitly checking whether the repeat-speaker is familiar with the repeated reference/expression (cf. Svennevig Reference Svennevig2008:342). This further demonstrates that unlike repair-initiating wh-questions, clarification-seeking repetitions do not convey the need for clarification through composition alone, but through composition in conjunction with position, that is, the locally current epistemic situation, which remains negotiable.

OTHER-REPETITIONS DEALING WITH PROBLEMS BEYOND HEARING AND UNDERSTANDING

The interactional functions of other-repetition found cross-linguistically include actions that go beyond indicating problems of hearing or understanding. This often involves raising problems of expectation with what the previous speaker has said, for example ‘because it reports an extraordinary or remarkable fact, or because it presents an inappropriate or questionable view’ (Rossi, introduction, this issue 512). The following subsection deals with a first subset of these actions (displaying surprise or seeking justification), before we turn to another subset, where the action involves raising more serious problems of acceptability.

Dealing with problems of expectation: Displaying surprise or seeking justification

Like clarification-requests, actions of displaying surprise or seeking justification are implemented through the same rise contour associated with requesting confirmation, but in conjunction with specific constructional and contextual features. Thus, implementing these actions similarly relies on confirmation-requests working as vehicles for other actions. Apart from choice of contour, two sets of compositional resources are drawn upon, separately or combined, for indicating that the repeated talk runs counter to expectations: (i) increasing the span of the rise and (ii) doing a modified repetition by adding material to the repeat. These repeats may be treated either (a) as a confirmation-seeking display of surprise, or (b) as a double-barrelled request for [confirmation + justification]. Which of these distinct actions the repeat is understood as implementing depends on positioning—namely, certain particulars of the original turn—as shown below.

Case (a): Display of surprise

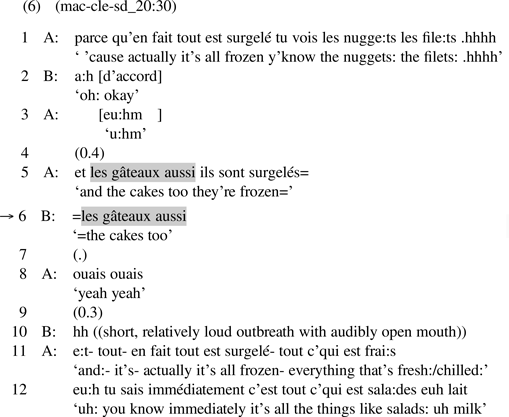

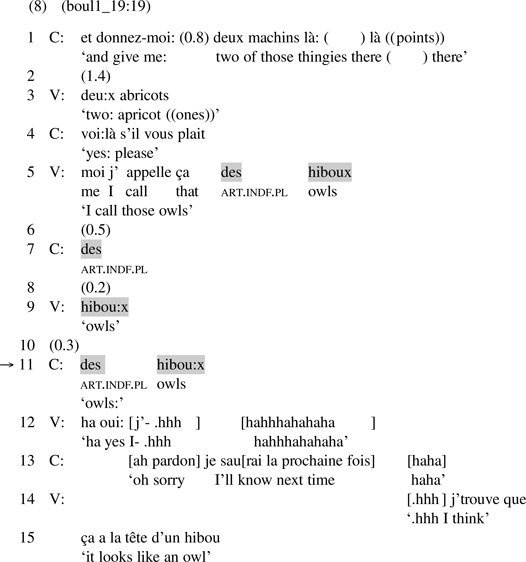

A display of surprise makes relevant confirmation and some form of affiliation with, or acknowledgment of, the displayed surprise. An illustrative case is extract (6), where A is describing practices at the McDonald's where she works.

The original turn is somewhat ‘primed’ for a subsequent display of surprise with the adverb aussi ‘too’ underscoring that cakes might have been expected not to be frozen, unlike previously mentioned items. B's repetition picks up on this, and is delivered with a wide rise contour (see Figure 5) with a total pitch span of 12 semitones and a pitch upstep across the voiceless onset of the last syllable spanning 7 semitones. A confirms with a double ouais (line 8), which does ‘assuring’, thus acknowledging and minimally affiliating with B's display of surprise (see below on confirmation formats). At the next transition-relevance place, B produces a sharp outbreath (line 10), embodying further surprise by passing on a turn and presenting herself as literally ‘left open-mouthed’ (cf. Wilkinson & Kitzinger Reference Wilkinson and Kitzinger2006:166–67).

Figure 5. Pitch trace for line 6, extract (6).

In extract (7), we find an other-repetition at some distance from the original turn. The turn immediately following the original turn is instead occupied by a confirmation-seeking news-receipt, and the other-repetition is a second response to the same turn. Although this pattern is common in the data, these other-repetitions are not part of the core collection as they occur later than in next turn (see Rossi, introduction, this issue, for inclusion criteria). Nevertheless, extract (7) is shown here to provide a more complete picture of how participants deploy other-repetitions in the doing of surprise. This extract is from a radio phone-in show; the caller A is organising a public debate on unconditional basic income, and its possible implementation in France or the EU.

B's first repair-initiation (line 8) may be strictly about audibility: since A recycles the words ils ont in line 5, the place reference is the only part of A's proposition not produced in the clear. However, the news-receipt at line 10 (with a wide rise) is designed to display surprise, and A's double oui (line 11) is responsive to and affiliative with that surprise-display. The host B then produces the repetition with a very wide rise contour (en Alaska ‘in Alaska’), with an additional secondary accent on the first vowel of Alaska (the repetition part of the turn spans 20 semitones; see Figure 6). B then extends the turn beyond the repeat with chez les Américains là-bas ‘among the Americans over there’ (two further high accents on -cains and -bas). This addition is disambiguating—it spells out an implicit element (policy-makers in Alaska are Americans) and does not result in an alternative or more precise version than the original turn. The addition simultaneously pinpoints the aspect of A's talk that runs counter to B's expectations, something further unpacked later (lines 16–17). The unexpectedness of A's informing is also explicitly referred to by B as étonnant ‘surprising’ and A overtly affiliates with this position by evaluating the fact as incroyable ‘unbelievable’. Subsequently, B also terms it bizarre ‘strange’.

Figure 6. Pitch trace for line 12, extract (7).

As mentioned, extract (7) illustrates that when displays of surprise involve other-repetition, the performance of surprise may be distributed over several turns, with a division of labour between repetition and other surprise-displays like news-receipts (e.g. ah bon ‘oh really’) and expressions like dis donc (roughly ‘oh wow’). The disambiguating addition in extract (7) also exemplifies a set of nonprosodic resources for signalling unexpectedness: additions to the repeated material that may be included in the repetition turn (thus making it a modified rather than exact repetition; see Rossi, introduction this issue). Below are further illustrations of how additions may index expectation issues (additions underlined).

(i) Additions may be disambiguating, spelling out elements that are arguably implicit in the original turn or the context (cf. extract (7)). Here, the repeat-speaker treats the cost of hiring a nanny as unexpected by adding the implicit ‘denominator’:

(ii) Additions may produce constructions singling out the unexpected element. Here, the emphatic (disjunctive) pronoun toi ‘you’ (singular) is added to a repeated infinitive phrase—the repeat-speaker treats it as unexpected that the addressee, specifically, should talk about football.

(iii) Additions may consist of expectation-indexing lexical items, which explicate how the problematic talk relates to expectations, such as the adverb-like que ‘only’.

Responses to surprise-displays regularly involve more ‘insisting’ confirmation, as if to dispel potential doubt. This typically takes the form of either multiple confirmations tokens (e.g. lines 13, 19 in extract (7), and line 8 in extract (6)), or [confirmation token + repetitional confirmation], and may include a prefatory particle eh, which in combination with confirmation tokens oui/ouais conveys insistence in the face of surprise or astonishment (see extract (7), lines 13, 19). These response forms are one way in which coparticipants minimally acknowledge the surprise displayed by repeat-speakers. These responses allow dealing with both relevancies set up by a repetition displaying surprise—confirming and affiliating—with a single responsive action. Displaying surprise is then treated as a second-order action (Levinson Reference Levinson, Sidnell and Stivers2013), laminated onto the first-order action of requesting confirmation. Although sometimes subsequent responses may be dedicated to affiliating with surprise-displays (cf. extract (7), line 15), surprise-displays are typically not double-barrelled (cf. justification-seeking repeats).

Case (b): Justification-seeking repeats. Justification-seeking repeats are double-barrelled requests for [confirmation + justification], similarly to requests for clarification. Again, the double-barrelledness ties in with the position-composition interplay: two different positional features appear to favour the interpretation of the repeat as seeking justification (rather than displaying surprise):

(i) The original turn involves negative turn components (cf. above).

(ii) The original turn speaker has heightened agency, that is, takes a stance of being personally invested in and responsible for what the original turn conveys.

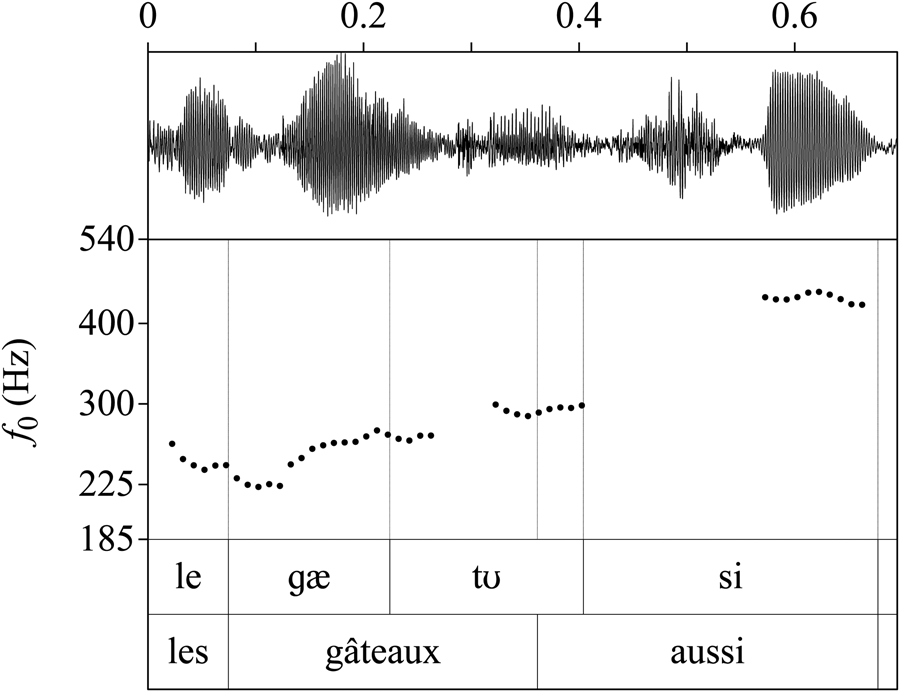

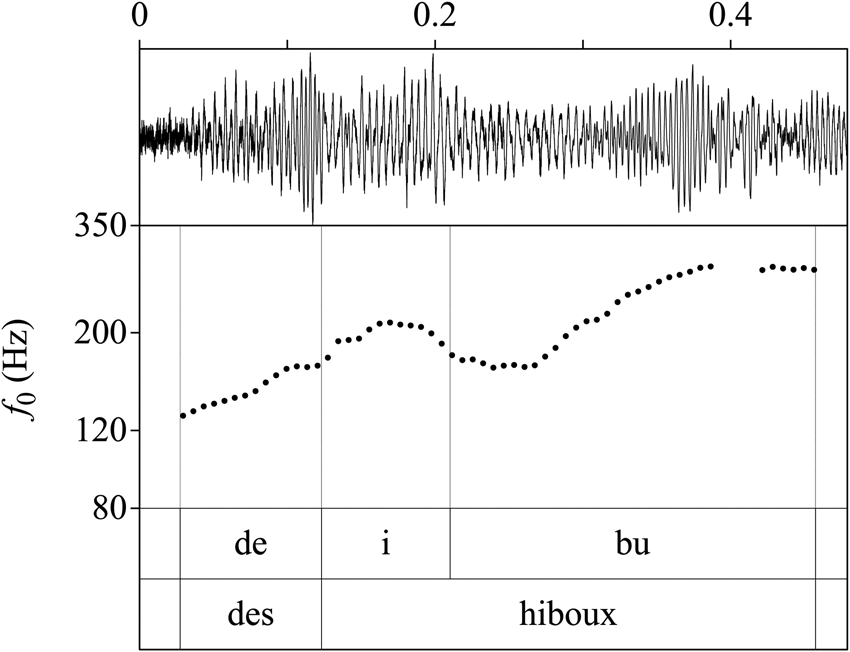

Extract (8), from a bakery, illustrates a justification-seeking repetition (line 11), preceded by a completion-seeking one (line 7).

C uses a placeholder noun (machins ‘thingies’) in his request for some pastries (line 1), and V's candidate understanding (line 3) proffers a semantically richer reference form for the product (abricots ‘apricot ((ones))’). Then, the original turn (line 5) is formulated as a personal choice of terminology (and not e.g. as an assertion of conventional usage): C even uses a left-dislocated first-person pronoun (moi ‘me’), underscoring precisely this. C initiates repair with a completion-seeking repetition of the indefinite plural article (line 7), using the rise-from-low contour, and V responds with the bare, projected noun (line 9). Thus far, the trouble is treated as restricted to hearing. However, C initiates further repair, repeating the whole referring expression at line 11 with a rather wide rise contour (see Figure 7): the whole turn spans 13 semitones, and the rise during the final vowel 7–8 semitones (after the microprosodic dip caused by consonant articulation). V responds with confirmation (line 12) before beginning and then suspending what appears to be the justification later produced in full (lines 14–15), referring to the appearance of the product. Note that in line 13, C begins an apology (for not using V's term) immediately after V's confirmation. So although C's interactional objective may not be to elicit justification, the linguistic form (wide rise repeat) together with the particulars of the original turn (C's investment in its content) make the repetition hearable as doing just that, and V responds accordingly, even though it requires a re-launch after the overlap (lines 14–15).

Figure 7. Pitch trace for line 11, extract (8).

Essentially, justification-seeking repetitions are distinguishable from surprise-displays thanks to position, rather than composition. In extract (6), the expectation problems signalled by B are treated by A not as making justification relevant (A does not justify selling frozen cakes), but as a surprise-display making relevant confirmation and affiliation. This is because in and before the original turn, A's impersonal descriptions consistently present the routines as matter-of-fact practices at her workplace, rather than as agency-laden actions or practices for which she as an employee would have some responsibility. This is a question of agency and not epistemics: A is more knowledgeable than B, but that does not affect the attribution of agency. Similarly, in extract (7), although A is treated by both participants as more knowledgeable on the subject, A does not justify what her original turn reported, since the unexpectedness concerns matters over which A has no agency. B's actions therefore amount to a display of surprise.

Justifying responses are sometimes difficult to analytically disentangle from clarifying ones, and problems of understanding can also be intertwined with problems of expectation (Rossi, introduction, this issue). Also, occasionally, hearably expectation-related repair-initiating repeats (with wide span) get clarifying matter-of-fact responses that ignore the putative expectation issues. All of this indicates that respondents sometimes have some leeway in terms of whether to produce clarifying or justifying elaborations.

Dealing with problems of expectation: Questioning acceptability

The interactional work of repetitions that question acceptability may be glossed as: ‘Is this what you said? If so, it doesn't make sense!’. These repetitions also diagnose the trouble as expectation-related, but work differently from those described above.

First and foremost, acceptability-questioning repeats deal with getting a candidate hearing or understanding confirmed, thus starting by excluding, for example, incorrect hearing, in order to first eliminate a less ‘serious’ type of potential trouble (cf. Svennevig Reference Svennevig2008 on trouble-type ordering in repair sequences). However, as a second-order action, they also adumbrate dealing with more serious trouble in the event that the problematic understanding indeed is what the trouble-source speaker said and meant. Such serious trouble may have to do with the problematic turn or action being incoherent, unreasonable, or otherwise unacceptable. Acceptability-questioning repeats thus display or project a disaffiliative stance different from justification-seeking repetitions: indeed, they convey that in the repeat-speaker's perspective, the problematic talk or what it reports cannot reasonably be justified. Consequently, the response-speaker may—instead of confirming—take the opportunity to back down from the problematic turn or action.

Intonation-wise, acceptability-questioning repetitions have a rise-fall contour (H* L%) with a wide span, usually due to a wide fall. (So like many surprise-displays and justification-seeking repetitions, these repetitions have increased span, but a different intonation contour.) This contour is also used in candidate interpretations—which involve substantial reformulation of the original turn or inferencing going beyond it—with an analogous action import and sequential trajectory (Persson Reference Persson2017b:47–48).

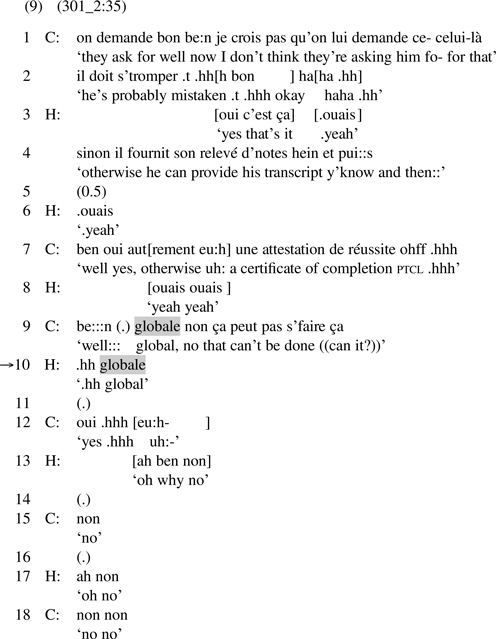

Extract (9) illustrates acceptability-questioning repeats. Speaker C is calling the faculty of law on behalf of his son (a former student), who has claimed that he urgently needs a certificate of completion of studies for the first year of studies. H has explained that certificates of completion are only issued as temporary certificates while waiting for an official degree diploma. Therefore, certificates of completion are issued only for the second/DEUG, third/bachelor, and fourth/master years. In lines 7 and 9, C asks a question about a ‘global’ certificate of completion, that gets partially repeated (line 10).

H produces the repeat with a wide rise-fall contour, where the fall encompasses 20 semitones (see Figure 8). The repeat (line 10) works to verify that a ‘global’ certificate of completion really is what the caller is asking about, and C provides a mere, single-token confirmation (line 12). Additionally, the repeat works as a preliminary to H's emphatic disaffiliative answer (line 13), where the negative particle (non) is prefaced by particles ah ‘oh’ and ben ‘why/well’ which contribute to conveying that C's question was inapposite and that it goes without saying that there is no such thing. H's negative answer (non ‘no’) is then receipted by C (line 15), reasserted by H (line 17) and again receipted by C (line 18).

Figure 8. Pitch trace for line 10, extract (9).

These repeats can be analysed as ‘prechallenges’ since convey incipient disaffiliation, with a sequential organisation reminiscent of pre's (Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007): repeat-recipients have the option to merely confirm, thereby allowing the sequence to proceed to the adumbrated disaffiliative action from the repeat-speaker. Alternatively, repeat-recipients may anticipate the disaffiliative action ‘in the works’ and pre-empt it by emending or backing down from the problematic turn or action (cf. Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007:151–55). However, wide rise-fall repetitions are not responded to as double-barrelled actions: backing down is an alternative to confirming, and the two are not combined in the same response turn. Thus, the (pre)disaffiliative work of wide rise-fall repetitions is a second-order action (cf. Persson Reference Persson2015a), and not a second ‘barrel’.

OTHER-REPETITIONS DEALING WITH OTHER ‘PROBLEMS’

Some classes of other-repetitions do not initiate repair, but accomplish other interactional work.

Registering repeats

Registering repeats may occur in sequence-closing third position (see Schegloff Reference Schegloff1997:527–28), but may also serve to register a first pair part, before the doing of the pending second pair part. These repeats make confirmation optionally relevant; confirming responses may unproblematically either occur or not (Persson Reference Persson2015b). Registering repeats are typically produced with a fall-with-initial-rise (Hi L* L%) contour—which involves a falling or low primary (nuclear) accent accompanied by a prominent (high) secondary (‘initial’) accent—or with a fall (L* L%)—which lacks a prominent secondary accent.

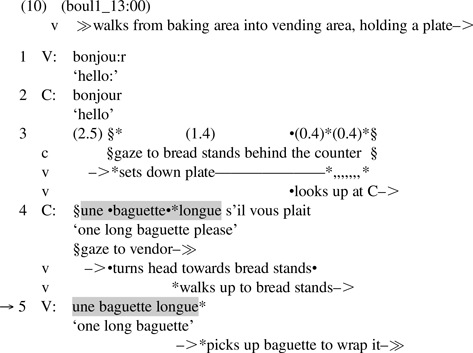

Extract (10), where a vendor (V) in a bakery repeats the customer's request, illustrates a registering repeat with a fall-with-initial-rise contour.

The repeat gets no response, such as a confirmation, and the physical action of getting the item is done immediately upon completion of the repeat in line 5 (the physical action is also prepared throughout lines 4–5). This indicates that before the request is properly dealt with, it is being registered as unproblematic, which sets registering repeats apart from repair-initiations.

Some registering repeats in the collection convey that although not immediately forthcoming, a relevant response is under way. Such instances are analysable as ‘mulling over’ the original turn (Kelly & Local Reference Kelly and Local1989:272ff), or as buying time (Bolden Reference Bolden2009a:136–38). These functions may be thought of as particularised tasks that registering repeats can accomplish in various sequential environments where a response from the repeat-speaker is pending.

Topicalising repeats

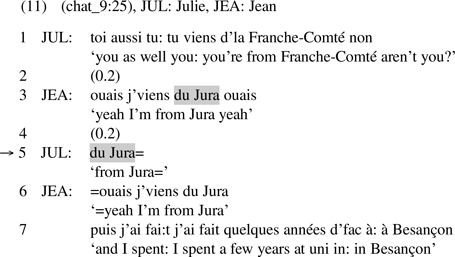

The rise contour, robustly associated with requesting confirmation across trouble-types, is also used with repeats that topicalise the repeated talk. Here too, confirmation is requested before the topical development is normatively produced by the original turn speaker. Consider extract (11), from a conversation among friends. For a while, the talk has revolved around Julie's recent stay in a Swedish city, compared by Julie to French city Besançon, capital of the Franche-Comté region. Julie's question (line 1) is hearable as topic-proffering, proposing a transition to a topic attentive to Jean, and this proffer is taken up in lines 6–7 and beyond.

The original turn (line 3) first confirms, and then specifies, the terms in which the question (line 1) is framed (Jura being part of Franche-Comté). Julie's repetition (line 5; Figure 9) has a rise contour exhibiting narrow pitch span (5 semitones over the whole turn): disregarding microprosodic dips during consonants, each syllable is slightly higher than the previous. In response, Jean treats the repeat as double-barrelled, both requesting confirmation and encouraging topical development (line 6–7). Note that the elaboration of the response turn (line 7) does not repair, clarify, or justify the original turn, but rather extends or continues Jean's telling, and the topic of Jean's experience with Franche-Comté. Also, while the original turn itself does not project more talk from Jean, the wider sequential context does: Julie's topic-proffer is designed to engender sustained topic talk. Thus, what differentiates topicalising repeats from mere confirmation-requests is not compositional aspects of the repetition, but the sequential position of the original turn.

Figure 9. Pitch trace for line 5, extract (11).

Repeats as prompts for recommitment

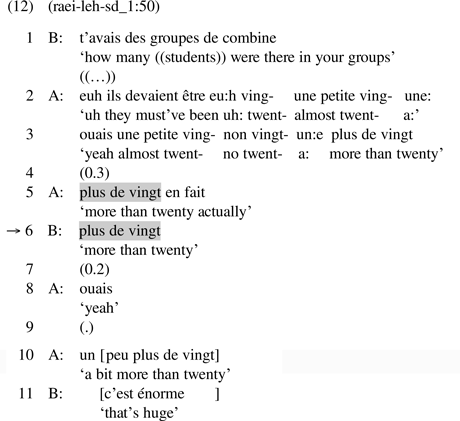

As mentioned, confirmations can be adequate responses to actions that do not clearly involve raising any of the canonical troubles: hearing, understanding, or expectation. Such is the case in repetitions used to deal with a lack of displayed commitment with respect to the position taken in the original turn. The work of such repetitions can be glossed as ‘Are you sure?’. Thus, the repeat provides another opportunity for speaker A to strengthen their commitment to the original turn (as taken up by B); see extract (12).

A's original turn (lines 2–5) exhibits numerous same-turn self-repairs, which ultimately (together with the epistemic modal construction in line 2) make her answer hearable as ‘lacking conviction’. B's repeat with a rise contour (line 6) provides A with an opportunity to recommit to her answer. She does so by confirming (line 8). She then also adjusts her answer (line 10), albeit in overlap with B's assessment (line 11).

Neither the rise contour, nor the expectable response [confirmation], is specific for prompts for recommitment. Thus, the action of prompting recommitment is best seen as particularised use of a form associated with the more generic function of seeking confirmation, deployed in environments where the original turn is hearably noncommittal.

Ah-prefaced repeats

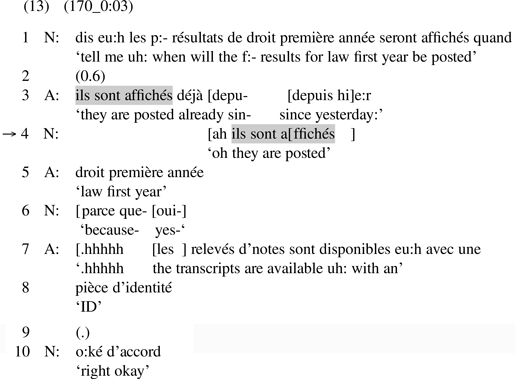

Repeats prefaced by the change-of-state token ah occupy a position between repair-initiators and receipt tokens (Persson Reference Persson2015a). Specifically, the particle suggests that its speaker has undergone a change-of-state in terms of informedness. Thus ah-prefaced repeats differ from repair-initiating repeats by indicating that the producer is, at least tentatively, taking in or accepting the repeated talk. An ah-prefaced repeat performs a specific combination of interactional tasks: acknowledging receipt of the repeated talk while simultaneously indexing the repeat-speaker's own prior action (before the original turn) as somehow inadequate; see extract (13)—from a call between two student-facing staff members at a university.

Following N's question (line 1), A provides an answer (line 3) that early on rejects one presupposition of the question (namely, the results not having been posted yet). In overlap with A's emerging answer, N displays taking this in, with an ah-prefaced repeat (line 4), here with a fall contour. Thus, N both receipts A's informing and retrospectively acknowledges her own prior turn to be problematic (based on a faulty assumption). The ah-prefaced repeat, produced in overlap, is not directly responded to, but A continues her turn by extending the answer (lines 5 and 7–8).

Ah-prefaced repeats differ from repair-initiating repeats by retrospectively indexing trouble (and sometimes topicalising it, depending on prosodic-phonetic design), rather than identifying trouble yet-to-be-resolved. Ah-prefaced repeats and their prosodic-phonetic variability are investigated in detail elsewhere (Persson Reference Persson2015a).

CONCLUSION

This article has considered how actions are formed in French talk-in-interaction through position-composition interplay. The essential features of the action-formation mechanisms are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of constructional and contextual features with relevance for action-formation. A: original turn speaker, B: repeat-speaker.

The outlined system shows the importance of both position and composition; the normatively expectable response is often a product of repetition turn-design (including prosody and grammar) in interplay with the particulars of the repeated material and the sequential and epistemic context. However, the intonation contour type is often of primary importance for differentiating among the various repair and nonrepair functions of repetitions. The rise-from-low, rise-fall, and fall contours all characterise distinct functions. Another indication of the robust functional distribution of contour-types is that the versatile rise contour is strongly associated with seeking confirmation (in repeats and elsewhere), and confirmation is part of the sought-after response in all repeat-categories that have a rise contour (regardless of span). So when the response involves some form of clarification, specification, or justification, the response turn overwhelmingly begins with confirmation, and the repetition is thereby treated as double-barrelled. This is a parallel to other double-barrelled actions, for example, yes/no-interrogatives in English (Raymond Reference Raymond, Reed and Raymond2013), where the interrogative ‘vehicle’ action elicits a polar answer, and the ‘cargo’ action elicits some elaboration. Here, the first relevancy (that of confirmation) is established through the rise contour, while the second relevancy is shaped by the particulars of the repeated talk and its context (which thus narrow down the function of the repetition, beyond confirmation-seeking). Furthermore, note that double-barrelledness is only one possible way in which actions can be laminated—actions can also be layered as first-order and second-order actions, as in repetitions that display surprise or question acceptability.

Regarding grammar of other-repetitions, it is noteworthy that the collection contains no repetitions that elicit response through any of the nonprosodic formal indices of questionhood: subject-verb inversion, the interrogative particle est-ce que, or question tags. This is another indication of the importance of prosody, epistemics, and sequential context for the response relevancies set up by other-repetitions. Also, no discernible action import was found for the grammatical constitution of the repetition, for example, clausal/phrasal or full/partial. However, syntactic incompleteness is common in hanging repeats, and ah-prefacing of repetitions characterises the function of retrospectively indexing trouble. Finally, expectation trouble can be indicated through additions to the repeat, and negation in the original turn is interactionally significant.

One general upshot of this study concerns the interplay between position and composition in action-formation. Regarding repair, it has been argued that repair-initiation after first pair parts is prone to indicate upcoming disagreement or rejection, that is, problems of acceptability (Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007:102–104), suggesting that the post-first sequential status of an other-repetition may be a powerful cue to the actions it may accomplish beyond initiating repair. This study, however, suggests otherwise: repair-initiating repeats can function as simple understanding checks after both first and second pair parts, and expectation-related repair does not hinge on sequential status relative to adjacency pair structure. Beyond adjacency pair structure, however, other aspects of ‘position’ are consequential for the action conveyed by the repeat, for example, whether the immediately preceding talk conveys heightened speaker agency, and whether it projects elaboration. Aspects of epistemic context are also consequential, for example, whether the repeat-speaker can be assumed to have access to the matters referred to in the repeated talk: the diagnosis of trouble as understanding-related partly depends on the trouble-source being intersubjectively understood as epistemically inaccessible to the repeat-speaker (cf. Robinson Reference Robinson, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013).

Another general upshot concerning repair is that attribution of trouble to the respective gross trouble-categories speaking/hearing/understanding may neither be omnirelevant nor sufficient for participants. For instance, some hearing trouble is dealt with through confirmation-seeking repeats (understanding checks) and some through hanging repeats (and in yet other cases nonrepeat repair-initiators are used, e.g. open-class ones). Furthermore, given the versatility of some repair-solutions with respect to trouble-type, the solution may rather be what the repair sequence is organised around, at least in some cases: confirmation may be adequate response both to actions that raise a problem of hearing, and to other hearing/understanding checks where the exact cause of trouble from either participant's perspective remains unclear, as well as to actions that treat the original turn as noncommittal. Thus, not only do the functions of repetition-classes cut across gross trouble-categories, but sometimes the specific trouble-type does not even go on the interactional record.

To conclude, let us consider some implications of this interactional study in the light of intonation research in other traditions. Interactional analysis of other-repetitions partially confirms and partially disconfirms what we might expect based on claims about ‘echo questions’ in elicited speech. Delais-Roussarie and colleagues (2015) find that rise-falls convey straightforward understanding checks, and rises indicate problems of expectation. In contrast, the present study shows that straightforward understanding checks are done with a rise contour, and that both rises (H* H%) and rise-falls (H* L%) can serve to signal problems of expectation—albeit of different kinds—typically in combination with pitch span expansion. Furthermore, recent work on elicited speech in various Romance languages has challenged the idea—commonly accepted in phonology—that pitch span variation is gradient and therefore paralinguistic by noting that pitch span expansion over the nuclear pitch movement allows categorically perceptible distinctions between ‘neutral’ and ‘counter-expectational’ questions (e.g. Savino & Grice Reference Savino and Grice2007; Borràs-Comes, Vanrell, & Prieto Reference Borràs-Comes, del Mar Vanrell and Prieto2014). While seemingly in line with such results, the present study shows that wider pitch span (on certain contours) is only one of the resources that participants use for conveying expectation-related repairable trouble.