INTRODUCTION

During ethnographic fieldwork at a Copenhagen gymnasium (the Danish equivalent of high school), the following situation occurred: A group of students used a private Facebook Messenger group to write in negative terms about some of their classmates. A few weeks later, it turned out that their interaction had been screenshot and subsequently leaked to another Facebook Messenger group involving all of the students in the class. The leaked screenshots featured the slandering activity as well as the names of the students who were responsible. The students behind the slandering were not aware of being retrospectively monitored and only later became aware that their earlier correspondences were exposed to an audience and framed as transgressive behavior.

I return below to how the students who were subjected to slander gained access to the screenshots and how we (the research team) gained access to the data. I also return to analyzing the posts as well as their uptake. For now, this incident illustrates the focus of the article: how and why the students who took and posted the screenshots created a retrospective surveillance structure and what social and interactional consequences this activity had. In their choice of social media platform, the posters decided who should be invited as an audience (the whole class), and directed the gaze of that audience toward what they deemed to be transgressive behavior (slandering). The posting of accusations of slander for selected audiences, accompanied by screenshots as documentation, turned out to be a repeated activity that also involved the movement of digital discourse across different social media platforms (for example, a screenshot of an Instagram post inserted into a conversation in a Facebook Messenger group). Inspired by Foucault's notion of panopticism (Foucault Reference Foucault1977), I suggest that situations in which people expose each other's behavior to selected audiences should be analyzed as panoptic structures. A central point here is that the affordances of digital devices provide a powerful tool for this type of communicative practice. Such practices of strategic exposure in digital environments have hitherto received little attention within sociolinguistics (see Skovholt & Svennevig Reference Skovholt and Svennevig2006; Jaynes Reference Jaynes2020 for exceptions). However, the data presented below demonstrate how this type of activity plays a central role in the participants’ online interaction.

The creation of panoptic structures resulted in prolonged and heated discussions, and the participants continued to refer to these incidents as the conflict progressed. As such, I contend that they deserve to be studied in detail. What characterizes such practices? What type of response do they prompt? What norms do the participants negotiate for their use, and are there any long-term consequences for social life? These sub-questions allow me to answer the article's central research question: What characterizes the discursive creation of panoptic structures in digitally mediated communication, and how is this activity exploited as a powerful tool in the lived experience of contemporary youth?

To answer this, I first introduce my theoretical framework, which I have divided into three parts: the affordances of digital devices organized in polymedia repertoires (Tagg & Lyons Reference Tagg and Lyons2021) providing for the choice of an audience, the metaphor of the Panopticon prison (Foucault Reference Foucault1977) and its relevance to studies of online interaction, and the movement (or entextualization) of bits of communication from one context to another (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1990). To understand more about the role of panoptic practices in daily communication, I then turn to the case study. The data I address are part of the SoMeFamily project and were collected among students at a Copenhagen gymnasium. The project is a multi-sited, online and offline ethnography (Androutsopoulos & Stæhr Reference Androutsopoulos, Stæhr, Creese and Blackledge2018) aiming at documenting the students’ communicative practices across offline and online settings. I present in detail how we obtained data by combining offline- and online observation with interviews and how we were able to observe the conflict between the two groups of students unfold. I then turn to analyze specific instances of panoptic practices and their uptake. To conclude, I argue that an understanding of panoptic practices is necessary to account for contemporary social life among networked individuals (Papacharissi Reference Papacharissi2010).

THEORETICAL UNDERPINNINGS

Digital evidence, polymedia repertoires, and choosing an audience

Social media provide affordances that enable people to support arguments and reinforce allegations with digital ‘evidence’ and strategically choose their audience or potential ‘witnesses’ across various online platforms. A recent study by Jaynes (Reference Jaynes2020) establishes how screenshots of one's own as well as others’ social media activities may constitute such evidence. Screenshots are a technical affordance that allows the user of a device, such as a smartphone or a computer, to generate a digital image of whatever is displayed on the screen. With most devices, taking a screenshot is easy and only takes one action. This easily allows for the documentation and storage of social media activities as they unfold and enables the recycling of these screenshots in new interactions. Hence, the smartphone and similar devices function not only as communication devices but also as storage devices with the potential to recycle digital discourse into new communicative contexts.

When it comes to the online recycling of such ‘evidence’, social media users can choose where, how, and with whom they share it. This aspect of choice is accounted for by the concept of polymedia repertoires (Tagg & Lyons Reference Tagg and Lyons2021), which describes how networked individuals (Papacharissi Reference Papacharissi2010) strategically choose between a variety of social media platforms depending on their communicative needs in specific situations. The theory hierarchically orders the relation between devices (mobile phones, PCs, etc.), social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, etc.), channels (different online groups, one-to-one interactions, etc.), modes (writing, pictures, video clips, etc.), and signs (words, ways of spelling, emojis, etc.). In this article, I adopt this terminological distinction and the insight that social media users employ their knowledge of which combinations of platforms, channels, modes, and signs are perceived as belonging together in specific types of communication. In this way, choosing an appropriate combination is a reflexive practice that requires metapragmatic knowledge about online communication, and such knowledge can be applied strategically, for example, in the accusations described in the case study below.

The choice of platforms and channels involves choosing between different groups of (potential) recipients. An almost trivial fact about the daily lives of the participants in our study is that they can choose between sharing a picture with a few close friends in a private Facebook Messenger group or sharing it with hundreds of potential recipients by making a public post on Instagram. In this way, polymedia repertoires provide an excellent tool for the modeling and strategic exploitation of an ‘audience’. In his study of language style as audience design, Bell (Reference Bell1984, Reference Bell, Eckert and Rickford2001) describes how audiences consist of four different types of recipients: addressees, auditors, overhearers, and eavesdroppers. The distinction is similar to Goffman's (Reference Goffman1981) description of listener roles in his theory of participation framework. In Bell's theory, auditors are ratified participants in the activity. Overhearers are not ratified participants, but the speaker knows they are there, as opposed to eavesdroppers, whose presence is unknown (Bell Reference Bell1984:159). If we imagine a school class where a teacher asks a question to a particular pupil, this pupil is the addressee, and the other pupils are auditors. If a parent enters the classroom to deliver a forgotten lunch box and stays in the classroom for a while without permission, this makes the parent an overhearer, and if the headmaster happens to pass the class in the hallway and stops to listen for a moment behind the door, the headmaster becomes an eavesdropper. A point about social media communication, such as Facebook Messenger threads, is that its permanent character enables the roles of overhearer and eavesdropper to be populated a long time after the actual communication took place. Choosing a suitable platform from one's polymedia repertoire allows users to decide who should be included in the audience and to strategically explore the different audience roles. To theorize this strategic exploitation of visibility in more detail, I now describe the perspective of panopticism.

Panopticism and post-panoptic sociality

In the case study I elaborate upon below, when screenshots were used to support accusations of gossiping before an audience, the poster took advantage of the posts’ visibility to wield social control. Theoretically, this resembles Foucault's theory of panoptic power wielding (Foucault Reference Foucault1977) and the further development of this theory under the umbrella term of post-panoptic sociality (Arnaut Reference Arnaut, Arnaut, Blommaert, Rampton and Spotti2012; Leppänen, Kytölä, Jousmäki, Peuronen, & Westinen Reference Leppänen, Kytölä, Jousmäki, Peuronen, Westinen, Seargeant and Tagg2014; Rampton Reference Rampton2015; Boyne Reference Boyne2000).

The Panopticon refers to a prison designed in the eighteenth century by the philosopher Jeremy Bentham, where an authority figure is able to observe all inmates from a central position. The authority figure stays in darkness, but the inmates are exposed because they are in light. In this way, the inmates never know whether they are being observed or not. Foucault's point is that the mere possibility of being watched (and sanctioned) is enough to make the inmates adjust their behavior in accordance with the expectations of the authority figure. In this way, visibility becomes a trap (Foucault Reference Foucault1977:200), and the constant risk of exposure becomes a way of exercising social control.

The metaphor of the Panopticon has been influential in surveillance theory (Lyon Reference Lyon2007) and is useful in describing the effects of surveillance carried out by authorities in institutional settings like schools and hospitals (Boyne Reference Boyne2000). These contexts are characterized by clearly defined distributions of power, static organizations of space, and predefined norms for behavior (Haggerty Reference Haggerty2006). The notion of post-panopticon extends the theory to also include spaces characterized by fluid boundaries, dynamic distributions of power, and multiple centers of normativity such as, for example, social media contexts (Leppänen et al. Reference Leppänen, Kytölä, Jousmäki, Peuronen, Westinen, Seargeant and Tagg2014:2).

Two earlier studies focus on the strategic use of visibility in digitally mediated communication. Skovholt & Svennevig (Reference Skovholt and Svennevig2006), for example, study how the CC function in emails is exploited in a workplace. In their analysis of a conflict, they find that one of their participants copies a number of other participants when responding to an email she found intimidating (Skovholt & Svennevig Reference Skovholt and Svennevig2006:56). The point here is that the sender decides who should view whose previous behavior. As Skovholt & Svennevig point out, this choice creates a particular kind of participation framework (Goffman Reference Goffman1981; Clarke Reference Clark1992). Again, the important point is that the roles of watchers and watched are introduced when the previous communication is shared with new participants.

Jaynes (Reference Jaynes2020) studies the use of screenshots in teenagers’ social media activities. Jaynes describes how the participants in the study take screenshots of social media activities as ‘evidence … valuable for reaffirming friendships and resolving or igniting conflict’ (Jaynes Reference Jaynes2020:2, emphasis in original). In a case study of a conflict between two groups, Jaynes shows how a participant writes in negative terms in a private group about a person who is not part of the group. A member of the group takes a screenshot of the interaction and shares it with the person who was slandered. Later, the screenshot is shared on Twitter, which further exposes the person writing ill of another. This shows how a screenshot can be used as ‘digital evidence’ and shared strategically to gain sympathy for the person subjected to slander and to punish the person doing the slandering.

In these two studies, the Foucauldian understanding of panoptic surveillance becomes relevant in relation to the local construction of the interactional roles of the watchers and the watched and the use of exposure as a powerful tool for seeking justice online. In contrast to the more static construction in a Panopticon prison, the participants use their polymedia repertoires to design a panoptic structure where the behavior of others’ previous or present behavior is exposed to an audience. In the Panopticon prison, one authority figure watches the many. In post-panoptic online settings, social control may be enforced by allowing many to watch the few (cf. synopticism; Mathiesen Reference Mathiesen1997). Also, the monitoring and the policing are carried out by peers rather than being conducted by institutional authorities (Arnaut Reference Arnaut, Arnaut, Blommaert, Rampton and Spotti2012). A consequence of this is that the authority to expose others’ behavior is not determined in advance. These rights are claimed and constructed locally, and acts of exposing transgressive behavior may be treated as violations of privacy norms.

Summing up, the creation of panoptic structures in digitally mediated communication can be understood as activities where people exploit their polymedia repertoires to put the behavior of others on display in a strategically selected media context and before a strategically selected audience; the purpose of the display is to expose and police others’ behavior. In the next section, I turn to the third part of my theoretical framework—a more detailed description of the phenomenon of sharing digital evidence.

Entextualization of screenshot social media activities

Accusations of earlier transgressive behavior supported by digital evidence point back in time by moving earlier events into new contexts. As such, constructing panoptic structures involves a series of causally interrelated events. Androutsopoulos (Reference Androutsopoulos2014:8) suggests that acts of sharing online—for example, quotes, pictures, screenshots, and movie clips—contain three stages: ‘selecting’, ‘styling’, and ‘negotiating’. The first two stages are conducted by the poster, while ‘negotiating’ also involves the uptake of the recipients. In connection to the case study detailed below, my analysis suggests that the ‘selecting’ stage would need to be supplemented with a stage of gaining access to digital evidence.

When sharing screenshots of others’ social media interactions, the screenshot discourse is decontextualized (i.e. removed from its original context) and recontextualized (i.e. inserted into a new context). Bauman & Briggs (Reference Bauman and Briggs1990) have labeled this process as entextualization. Based on studies of verbal performance, they describe how acts of entextualization involve negotiations of power and authority. Indeed, they describe entextualizations as ‘acts of control’ (1990:76) and identify four relevant components: access to the text, legitimacy to use it, competence in using it, and its value in the context. Regarding screenshots of content from private social media channels, access is often conditioned by an act of invitation or admission by somebody who is already a member of these channels. Legitimacy, according to Bauman & Briggs, is primarily concerned with the rights granted by institutions to produce such content. However, as described above, the power structures in social media settings are often more fluid than in institutional settings, and legitimacy is constructed locally in the recontextualization phase. Competence includes the technological knowledge and skills of taking screenshots and storing digital content, but also metapragmatic competence in strategically choosing platforms and channels and styling the post. Value can be seen as the function the posting of a screenshot fulfills in the interaction (birthday greetings, evidence, etc.). Seen together, access, legitimization, competence, and value are what construct authority in acts of entextualization (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1990:77). The poster of entextualized material may attempt to construct such authority more or less explicitly, but to what degree it is established depends on the uptake by the interlocutors.

An excellent example of entextualization in lived social life is Goodwin's (Reference Goodwin1980) he-said-she-said study. It investigates how a group of girls confront each other with rumors of talking behind their backs. Goodwin describes situations in which person A is confronting B because C told A that B had been gossiping about A to C. In other words, the confrontation refers to a series of events where A (the accuser) has been present in some of them and not in others. If we view the situations in chronological order, we can identify three situations.

-

Situation 1: B talks about A to C

-

Situation 2: C tells A what B said

-

Situation 3: A confronts B

As is apparent here, A was present in situations 2 and 3 but not in situation 1. The chain of events gives B the opportunity to reject the accusation and postulate that C must have misunderstood what took place in situation 1. Since A was not present there, A has no way of knowing whether this is correct or not. In fact, Goodwin finds that accusations such as the one conducted by A in situation 3 are typically followed by denials (Goodwin Reference Goodwin1980:680). Goodwin further describes how an acceptance of the accusation may end up in physical violence and concludes that ‘the act of denial, as contrasted with the act of acceptance, preserves the face of both parties and prevents a possible fight from occurring’ (Goodwin Reference Goodwin1980:681).

Goodwin's study has been taken up by much work investigating the role of gossip in social life (e.g. Briggs Reference Briggs1992; Aslan Reference Aslan2021) and illustrates how entextualization can be studied in interaction. Goodwin's study also serves as an important backdrop for comparing how gossip is handled before and after digitally mediated written communication became a central part of social life, including the possibility of keeping bits of communication for later use. The accusations of slandering addressed in Goodwin's he-said-she-said study are very similar to the accusations I analyze in this article. There is, however, one important difference. When gossip-based accusations are documented by a screenshot of the activity in focus, it is difficult to claim that the screenshot interaction never took place or that the accuser had the wrong idea about what was communicated in the original interaction—what were face-saving strategies in Goodwin's study. Instead, the accused may claim that an utterance has been taken out of a larger context, and—in particular—that the poster has no right to put the screenshots on display (especially not in front of a larger audience).

In the previous three sections, I have discussed how digital devices afford the storage and recycling of digital evidence, how polymedia repertoires allow for making strategically styled accusations backed by digital evidence before an exclusively selected audience, and how the exposure of other people's earlier online activities form panoptic structures of (retrospective) surveillance. Furthermore, these acts of exposure necessarily involve the movement of texts across a series of interrelated events. Taken together, these ideas provide the theoretical underpinnings of my study and allow me to investigate how entextualized social media posts, when used as evidence of accusations, travel across contexts and how the participants in the study exploit the options of visibility afforded by their polymedia repertoires as a way of seeking justice. But first, I introduce the case study in more detail.

METHODOLOGY

The data analyzed below originates from the SoMeFamily project. From the perspective of linguistic ethnography (Rampton, Maybin, & Roberts Reference Rampton, Maybin and Roberts2014; Heller, Pietikäinen, & Pujolar Reference Heller, Pietikäinen and Pujolar2018) and multi-sited online and offline ethnography (Androutsopoulos & Stæhr Reference Androutsopoulos, Stæhr, Creese and Blackledge2018), the overall aim of this project is to investigate social media communication and socialization in families (see e.g. Stæhr & Nørreby Reference Stæhr and Nørreby2021; Madsen Reference Madsen2022). The initial stage of data collection was carried out in two first-year classes in a Danish gymnasium, where we collected ethnographic data offline and online in cooperation with the students. The part of the project I address here is from one of these classes (twenty-eight students, sixteen to eighteen years old).

From August to October 2018, one or more researchers from our team would be physically present several days a week in the class. The research team followed the class from the first day in their new class and documented the students’ initiatives to create a sense of community online and offline. In the initial phase, the researcher would just observe and engage in informal conversations with the students during breaks. From October onward, we started to collect media-go-along interviews (Jørgensen Reference Jørgensen2016), where the participants made screenshots of the communication channels on their mobile devices while explaining to a researcher what the interactions were about. We continued collecting this type of interview data for approximately a year until September 2019.

Throughout the study, our ethical guidelines were to approach informed consent as a process (Mortensen Reference Mortensen2015). First, we gathered written consent forms from all participants and their parents. In connection with this, the participants were informed that our focus was on interaction in daily life, including interaction that took place in online settings. An example of our handling of informed consent can be seen in relation to our access to the students’ shared Messenger group named after the class. During a break, one of the researchers discussed with a student the online possibilities of communicating with the whole class at once. The student told the researcher about the shared Messenger group and offered the research group access to it. We accepted on the condition that the student needed to inform the class. Then we discussed our presence in the group with the class, informed them that we would never show content to parents or teachers, and agreed that they could always ask us to leave specific interactions out of our data. Similarly, we specified in the media-go-along interviews that the participants were the ones to decide what to show us and what to leave out. In terms of how to represent the data, all examples in the article are anonymized, and all names of persons and groups are replaced with pseudonyms.

The organization of a common polymedia repertoire in the class

In the class, all students, without exceptions, were active on social media. The following field note extract is from the first day of fieldwork.

We also talk a bit about which media they are using. All use Facebook. All except one use insta [Instagram]. All have Snapchat. One uses WhatsApp. Hannan uses Viber as the only one. And 5 uses Twitter. We inform them that we [the research team] have made profiles on Facebook, Insta, and Snapchat and that we would like to follow them there. (field note from our first visit to the site; my translation from Danish)

As is apparent above, the participants use a range of different social media applications, and the three most common are Facebook (including the Messenger app), Instagram, and Snapchat. Even before the first day of physical presence in the gymnasium, the future classmates had formed the common Messenger group referred to above, which they, among other things, used to arrange a joint trip for the new class. Likewise, several students explained how they had checked out their new classmates on Facebook and Instagram. During the first days in the gymnasium, the students created a common group on Snapchat and an Instagram profile bearing the class name, for which everyone in the class received the log-in information. The students told us that creating such class profiles on Instagram was something all new classes did. In addition, they formed several smaller groups based, for example, on reading groups and emerging new friendships. All in all, modeling the polymedia landscape was a central aspect of how the students created a social life for themselves.

During the three months of observation, we could observe how the communication channels set up in the beginning were typically used. We observed a pattern where the Snapchat group was mostly used for sharing quick messages and photos when participants were at home, on the go, had to find each other at school, or were teasing each other in class. The shared Instagram profile was used for more styled photos from everyday life and parties and became a way to showcase the social qualities and cohesion of the class to other students in the gymnasium, which was the main group of followers. The Messenger group was mainly used for discussions of homework as well as to suggest and arrange social activities and subsequently share pictures from them. Thus, the Messenger and Snapchat groups were private (restricted to classmates) online contexts, while the (shared) Instagram profile was a semipublic space (Ellison & Boyd Reference Ellison and boyd2013) in the context of the gymnasium where the classmates may add friends and similar profiles representing other gymnasium classes. In addition, we could see how other groups with fewer participants were used for more private purposes, including gossiping and grouching. In line with the concept of polymedia repertoires, this illustrates how the classmates organized different channels that came to fit different purposes in their new social life as gymnasium students.

Before turning to the case that includes the panoptic practices, I want to stress that the conflict interaction represents only a fraction of the social life in the class. In the Messenger group, where the conflict primarily unfolds, the vast majority of posts can be categorized as community-building activities such as friendly jokes, help with homework, and organizing social arrangements. This means that it cannot be concluded from this study that social media, in general, has made young people less social and less considerate. However, the panoptic practices I discuss below turned out to be part of the communication and community-building activities and therefore deserve attention.

The conflict

During the fieldwork, a conflict between two groups of students occurred. The first group shared an interest in parties and fashion, communicating intensively on social media on a daily basis, and were seemingly in the process of developing close friendship ties. The second group was based on a study group initiated by the institution but also seemed to be developing close friendship ties and, as we see below, a sense of loyalty.

The first time the research team became aware of the conflict was about two weeks after the accusation of slandering described in the introduction was posted. In the discussion following the post, the students referred to an earlier incident where a classmate critiqued the class in a public post on Instagram. Tracing this event in our data, we found out that this episode involved screenshots of others’ online activities too. We then started asking the students about the conflict when conducting the media-go-along interviews. Maya was one of the students who appeared on the screenshots that were shared in the class Messenger group as part of the accusations of slandering. In a media-go-along interview, she explained how the students posting the screenshots also shared these with the school administration and how, as a consequence of this, she and the rest of the group accused of slandering were called to an official meeting with the vice principal. Maya explained that the administrator of the group from where the screenshots were taken chose to close it down. However, the administrator then formed a new group with the same participants and the same name as the original group (here called the Clan) shortly after they were called to the meeting. Maya shared the communication in this group with the research team, including a long discussion of how the conflict progressed. When we interviewed other participants in the Clan group afterward, we informed them of our knowledge of this communication. Nobody questioned our access or intent to use it for research.

When combining the information gained from the online observation of the class's Messenger group, the interview with Maya, and the Clan group discussion, the conflict's progression can be divided into eight related situations (see Table 1 for an overview). In situation 1, a group of students slanders Hannan and Tobias in a Messenger group (here named the Clan). Situation 2 occurs at an outdoor party, where the Clan group member Lea adds Louis to the Messenger group. She claims this is a mistake made due to drinking too much alcohol. Louis is part of the same study group as Hannan and Tobias. Louis is removed again from the Clan Messenger group immediately after, but he is still able to see the earlier communication. We know this from the interview with Maya and online discussions in the reestablished Clan group (called Clan 2 below). Some days after, a post criticizing the class is made on the class's shared Instagram account (situation 3). This post is not signed, and because it is posted on a shared account, there is no name in the post's meta-data. The student Nabil takes a screenshot of the critique, posts the screenshot in the class's Messenger group, and asks the criticizer to stand forward (situation 4). After some discussion, Louis admits that he was the anonymous poster (situation 5). Two weeks later, Tobias and Hannan post five screenshots in the class's Messenger group of instances where they were slandered in the Clan group accompanied by a letter-like text addressed to the Clan members (situation 6). In this text, they mention that Louis gave them access to the screenshots. The entextualization of these screenshots leads to a prolonged discussion online. Two days later, Hannan reports the Clan group to the school authorities and accuses them of bullying (situation 7), and the Clan group members are called to a meeting with the administration (as explained by Maya). This makes Nabil reestablish the Clan Messenger group. The members use this group to prepare for the meeting with the administration (situation 8), and in connection with this, Nabil shares screenshots from a private Messenger exchange he is having with Hannan.

Table 1. Timeline of the polymedia activity; the arrows indicate the trajectories of the entextualized discourse.

Table 1 illustrates the progression of the conflict across the eight situations, including how it unfolds on different social media platforms. The arrows indicate how screenshots are entextualized from one platform to the other.

Apart from providing an overview of the conflict, including the travel of texts, the table illustrates the following theoretical points.

First of all, we can observe how the polymedia repertoire is not just a number of stable and parallel channels for the participants. In acts of entextualization, discourse is decontextualized and moved as screenshots across different Messenger groups and from Instagram to Messenger. In this way, the screenshotting activities enable the participants to exploit their polymedia repertoires for strategic selections of the audience.

Second, we can observe the trajectory of how text travels across offline and online contexts and from situation to situation. We see how the slandering from the Clan group moves from its members to Louis, from Louis to Hannan and Tobias, and from them to the rest of the class, and later to the school administration. The chain of entextualizations does not merely involve the circulation of screenshots across mediated contexts; it also involves a genre transformation from slandering among friends to digital evidence among peers and finally to an institutionalized piece of evidence on the vice principal's desk(top).

Third, we can observe how exposure becomes a central aspect of how the conflict unfolds across the situations. The critique on Instagram exposes the internal problems of the class to the rest of the gymnasium, and the person behind the critique, as well as the acts of slandering in the Clan group, are exposed to the other students in the class. The types of audiences afforded by private and (semi)public platforms play a central role in the students’ choices of where to post accusations of transgressive behavior.

In the following analysis, I address details of the panoptic practices and their uptake with a particular focus on the construction of audiences, how the entextualized material is framed as digital evidence, and the uptake from other students in the class.

ANALYSIS

Situations 3, 4, and 5: The Instagram critique

In early November, a general critique of the class is posted on the classmates’ shared Instagram profile. As mentioned earlier, this means that the other students in the class do not know who the poster is—just that it is somebody who possesses the log-in information, meaning that it is one of their classmates. BTC is the anonymized acronym for the class—short for Basic Training Class.

(1) “Roten milk” (situation 3)

Translation:

BTCgym: BTC is like milk! Fresh in the beginning…rotten in the end [rotten spelled råden, standard spelling is rådden]

As described above, the posts on the Instagram profile are generally characterized as being styled and featuring entertaining pictures and video clips, often creating an image of the class as being fun and coherent. The participants described the Instagram profile as the public display of the class's image to outsiders—mainly other students at the gymnasium. In this case, the post creates a somewhat different image of the class. It consists of a seemingly random picture taken out of a Metro window and a caption that explicitly criticizes the class. Furthermore, the post contains non-standard spelling, which also deviates from how the students normally write on Instagram, where standard spelling is the norm.

The post shows how the meaning of a message communicated within a polymedia repertoire is inseparable from the choice of channel and platform. The picture and the accompanying text become meaningful only in relation to the class's general norm of posting on Instagram and the choice of audience, that is, putting the class's internal problems on display in a (semi)public context in front of ‘outsiders’.

In the post, Louis informs the recipients outside the class about problems in the class and simultaneously lets his classmates know that something is going on. Furthermore, he potentially puts pressure on the members of the Clan Messenger group where the slandering took place. The Instagram post takes place a few days after he was included in the Clan group, and the group members know that he had access to their conversation. However, the Clan members are not certain at this point that Louis is the poster.

As the conflict between the classmates developed further, the participants often referred back to this post as being particularly offensive and an example of transgressive online behavior. On a later occasion, in a contribution to the class's Messenger group, the student Lea describes the post as “et insta billed hvor klassen bliver svinet til offentligt” ‘an Insta picture where the class is dragged through the mud in public’. In this way, she highlights the publicness of the platform (“insta”) and channel (the class's profile) and thereby criticizes Louis's choice of context for this type of compromising message. Furthermore, Lea's comment emphasizes that a successful Instagram class profile matters in the popularity economy of the gymnasium. Several students in the class invested significantly in the popularity of the profile. This can explain the negative reactions from the classmates in which the post is experienced as a way of sabotaging their previous online identity work.

Shortly after the post appeared on Instagram, the student Nabil posted a screenshot of the Instagram post on the class's shared Messenger group.

(2) “Just asking” (situation 4)

Translation (accompanying comments to screenshot of Instagram post):

Nabil: Who actually posted [spelled pistet where the standard spelling is postet] this ??

Just asking [spelled spørg where the standard spelling is spørger]

The entextualization of the Instagram post is supplemented by a caption, in which Nabil asks who posted the picture on Instagram. He adds two question marks and the utterance “just asking” to emphasize his question. In this way, he evaluates the act of anonymously criticizing the class as being inappropriate and, at the same time, positions himself as an authority with the right to make inquiries. By posting the screenshot, Nabil directs the gaze of his classmates toward the inappropriate post and puts pressure on the poster by letting the person know that he or she is being watched. By moving the post from Instagram to the Messenger group (and thus choosing Messenger as an appropriate context for further inquiry), Nabil decides who should be the audience to his accusation. In doing so, he controls the damage done to their shared Instagram profile by moving the internal discussion away from the (semi)public eye of Instagram.

Nabil's accusation is supported by other students in their comments (who, just for the record, are also part of the Clan group, but at this point, this is not known to the rest of the classmates).

(3) “The person won't stand by it obviously” (situation 4)

Translation:

1 Stephanie: By the way to whoever wrote this, it is spelled “rotten” [blinking smiley]

2 Nabil: Yes who is it?

3 Maya:I don't think we'll ever find out

4 Nabil: No [two footprints emojis] 5 Stephanie: The person won't stand by it obviously

In the first reaction, Stephanie mocks the non-standard spelling of “rådden”. Nabil reacts by enquiring who wrote the post. When Maya states that she thinks they will never find out, Nabil agrees and adds two footprints emoji. Stephanie's uptake in line 5 follows up on these footprints by stating that the one who wrote the post is walking away from the deed without assuming responsibility.

In line 1, Stephanie directly addresses the person who wrote the post “til dig der har skrevet det” ‘to whoever wrote this’. This shows that they expect him or her to read the exchange. This makes sense because only members of the class have the passcode to the Instagram profile. After this exchange, they move on to discuss ‘clues’ in the picture while knowing that the poster is very likely to watch their investigation unfold, thus putting pressure on the person to come forward.

The following day, several classmates were actively discussing a social arrangement in the evening. After a classmate creates an invitation in the messenger group, Louis selects the option indicating that he is not coming. This reply by Louis is automatically shown in the group and this leads to the following exchange.

(4) “Why are you not coming” (situation 5)

Translation:

1 Nabil: Louis why are you not coming after all

2 Louis: Have become sick

3 Nabil: Roten milk [using the non-standard spelling råden]

In this sequence, Nabil indirectly accuses Louis of having posted the picture and the critique on Instagram. He does so by implying that Louis suddenly feels ill due to the intake of “råden mælk” ‘roten milk’, thereby quoting the Instagram post including the same non-standard spelling of the word ‘rotten’ used in the original post. This adds another layer to the accusation. If Nabil knew or suspected that Louis was behind the Instagram post in the first place, his entextualization and the following inquiry could be interpreted as a way of putting pressure on Louis without confronting him directly with his classmates as an audience.

After a while Louis posts the following.

(5) “Here is the truth” (situation 5)

Translation:

1 Louis: Okay folks! Here is the truth: I was with some people it was not meant to be shared and it WAS REALLY not meant to be taken seriously. AND IM SORRY SINCE I DON'T MEAN IT … so sorry, I know it was stupid but hope you understand

2 Stephanie: We all knew it

Here Louis takes responsibility for the Instagram post. In a post using capital letters to emphasize central parts, he regrets, apologizes, and excuses the post as being stupid. Without outing his friends, Louis describes how he was fooling around with a group of people. By admitting his deed in this way, Louis acknowledges the norm for the Instagram platform as not being a place for internal critique.

Apparently, this was what Stephanie, Molly, and Nabil wanted. After the confession, they praise Louis for coming forward and try to convince him to participate in the social activity in the evening, thereby linking his excuse for not attending the evening's party to the social media exchange.

Situation 6: The accusation in the class's Messenger group

Approximately two weeks after the exchange above, the class's Messenger group is once again used as a platform for making accusations based on evidence in the shape of screenshots. This time the entextualization consists of two coordinated posts made by Tobias and Hannan—the example used at the beginning of the introduction. Tobias posts five screenshots of two different Messenger conversations. One screenshot is from the class's Messenger group (i.e. the same group as the screenshots are now posted in), which contains accusations made toward Hannan concerning the interaction following the discussion of the ‘roten milk’ post. The remaining four screenshots are from the Clan Messenger group, where seven named classmates appear in the screenshot interaction (Nabil, Eva, Maya, Molly, Naima, Stephanie, and Lea). The central theme in the screenshot interaction concerns the group members’ discussion of how they can avoid inviting Hannan and Tobias to an upcoming social event. The tone of the messages in the screenshots from the Clan group is rather harsh—for example, Hannan and Tobias are referred to as “snakes”.

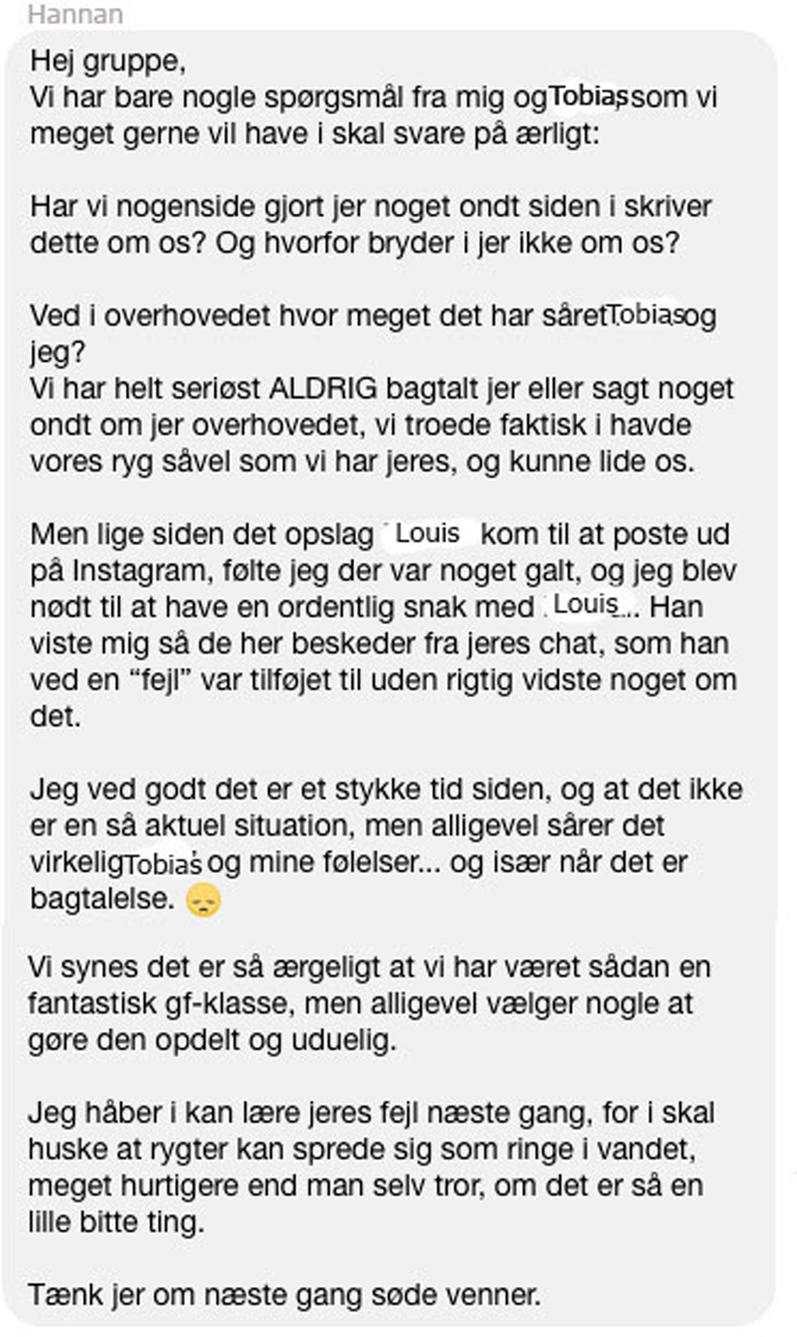

Hannan posts an accompanying letter-like text on behalf of her and Tobias. Compared to what is generally posted in the class's Messenger group, the character of the combined posts is massive. As there are several important theoretical points in connection to the accompanying text, it follows here in its entirety.

(6) “why don't you like us?” (situation 6)

Translation:

1 ‘Hi group,

2 We just have a few questions from me and Tobias that we

3 want you to answer honestly:

4 Did we ever hurt you since you write this about us? And

5 why don't you like us?

6 Do you have any idea how much it hurt Tobias and I? We

7 have seriously NEVER slandered you or said anything

8 negative about you at all. We actually thought that you

9 had our backs like we have yours and that you like us.

10 But ever since that post Louis posted by mistake on

11 Instagram I felt that something was wrong and that I

12 needed to have a serious talk with Louis. He then showed

13 me these messages from your chat, which he by “mistake”

14 was added to without really knowing anything about it.

15 I know it's been a while and that it's not a current

16 situation, yet it really hurt Tobias’ and my feelings …

17 and especially when it is slander.

18 We think it's so unfortunate that we've been one great

19 class, yet some choose to make it divided and incompetent.

20 I hope you will learn from your mistakes next time because

21 you need to remember that rumors can spread like rings in

22 the water, much faster than one thinks, even if it is a

23 tiny little thing.

24 Think about it next time sweet friends.’

In line 1, the text is addressed to the Clan group participating in the screenshot interaction. Tobias and Hannan explicitly accuse the persons of slandering, disloyalty, and hurting their feelings. This is quite similar to the three-step pattern observed in Goodwin's (Reference Goodwin1980) he-said-she-said study: (i) A group member shares the interaction with Louis, (ii) Louis informs Tobias and Hannan about the slandering, (iii) Tobias and Hannan confront the group. However, there are some significant differences as well.

First, the accusation is supported by digital evidence obtained through a complex entextualization chain. The accompanying text describes how Louis “by mistake” was included in the group and subsequently showed Hannan screenshots of the chat (lines 10–14). This illustrates the persistence of digital discourse, which allows messages to be seen by others long after they have been produced. To stay in the metaphor of the Panopticon, Louis invites Hannan and Tobias to join him in the surveillance room weeks after the interaction took place.

Second, Tobias and Hannan choose to post their accusation in front of the whole class and not just the students involved in the slandering activity. As they put it in the text: “we've been one great class, yet some choose to make it divided and incompetent” (lines 18–19). In this way, they ascribe different roles to the participating classmates in the Messenger group. The Clan group is the addressee of the accusation, and the rest of the class is invited to watch. Again, a local panoptic structure is established.

Third, the text contains a meta-communicative reflection about gossiping at the end: “I hope you will learn from your mistakes next time because you need to remember that rumors can spread (…) much faster than one thinks” (lines 21–22). In other words, the accused persons need to adjust their behavior in the future because they don't know who is going to be watching. This is similar to the original idea of the Panopticon where the possibility of being watched should lead to self-induced social control. Hannan's explanation here illustrates that the (post)panoptic perspective is not just a theoretical idea but also a lived experience among the students.

Hannan and Tobias’ text also illustrates the relevance of the notions of access, legitimacy, competence, and value underpinning the definition of entextualization (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1990). Hannan and Tobias entextualize screenshots from a private Messenger group, which they are not members of themselves. Therefore, they run the risk of being accused of breaching norms of privacy. This might explain why they, in a quite detailed way, describe how they got access to the Messenger group and the screenshot material. Furthermore, they legitimize their act of sharing the screenshots by the fact that they were slandered. In addition, they show competence by coordinating their individual contributions to the joined post (Hannan posts the letter, and Tobias posts the screenshots) and orient to the value of the entextualized material as evidence of who is responsible for the class being “divided and incompetent” (line 19). In connection to this, they explain Louis’ ‘milk post’ (excerpt (1)) on Instagram as a reaction to what he was exposed to in the Clan group, rather than as an offensive act in itself.

However, the accused group does not accept their authority to share the screenshot, which becomes clear in the immediate uptakes of the post.

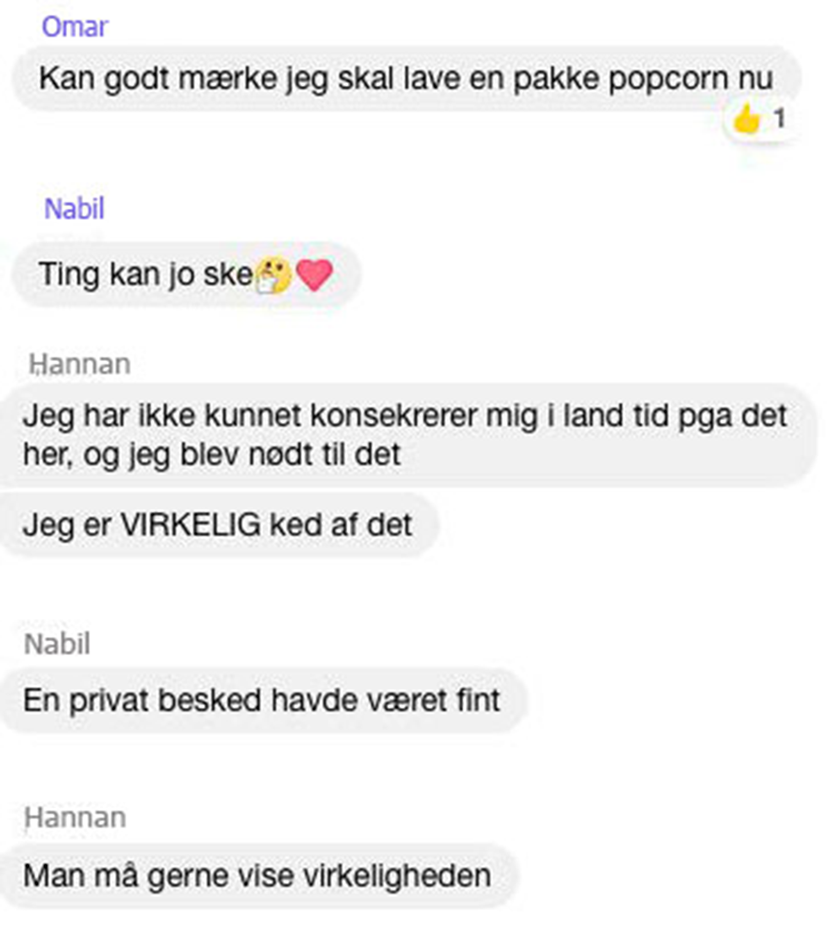

(7) “A private message would have been fine” (situation 6)

Translation:

1 Omar: Can sense that I should make a box of popcorn now

2 Nabil: Things can happen, after all [hand in front of mouth emoji,heart emoji]

3 Hannan: I haven't been able to concentrate for a long time because of this and I had to do it

I am REALLY sad

4 Nabil: A private message would have been fine

5 Hannan: One is allowed to show the reality

The first reaction is from the classmate Omar who is not part of the accused group. With his popcorn comment, he frames the situation as potentially dramatic and identifies with his assigned role as a spectator in a way that emphasizes that he expects a reaction from the accused group. Nabil provides this reaction by first briefly acknowledging that it happened, followed by two emojis (line 2). It is not entirely clear from the content how Nabil's contribution in line 2 should be interpreted, but the hand in front of mouth emoji and the heart emoji indicate that it is an attempt to downplay the severity of the content in the screenshots. Hannan reacts by stating how the screenshot interaction had affected her emotionally for a long time (line 3), rejecting Nabil's attempt to mitigate the situation. Nabil then addresses Tobias’ and Hannan's choice of audience by stating that he would have preferred a private message (line 4). He does not criticize their right to confront him, but rather that they did so in front of an audience. Hannan replies in line 5 that “one is allowed to show the reality”, thereby confirming that the inclusion of an audience is based on a reflexive choice. Thus, focus on the participation framework is again brought forward as central.

During the next couple of hours, more and more classmates joined the discussion. As the other members of the Clan group join the interaction, they take a position similar to Nabil's ‘private message’ response. The positions of the Clan group and Hannan become increasingly locked as the discussion continues in the group. Hannan claims that she is entitled to post whatever has been written about her—also from private groups. When she is confronted with having exposed the Clan Group members to the rest of the class, she states that “jeg havde brug for alle skulle vide det” ‘I needed everyone to know’. The Clan group, by contrast, argues that sharing messages from a private group with a larger audience is unacceptable. Members of both groups attempt to stop the conflict in a constructive way, but this turns out to be difficult. Two days later, Hannan shows the screenshots from the Clan group to the school administration (situation 7), and subsequently, the members of the clan Messenger group are called to a meeting with representatives from the administration about online bullying.

Situation 8: Collecting the evidence

Prior to the meeting, Nabil invites the members of the old Clan group to a new Messenger group—Clan 2. As mentioned, we know from the interview with Maya that the first group was shut down after the posting of screenshots (situation 6). Nabil informs the participants that the purpose of the ‘new’ group is to prepare for the meeting. The following example is from the beginning of the interaction. It shows how Nabil frames the situation and his position in it.

(8) “the real lawyer” (situation 7)

Translation:

1 Nabil: I will collect all evidence, you just let me do the talking

2 Stephanie: Hey I'm fucking scared

3 Mark: Nothing is going to happen

4 Stephanie: Have a warning ((meaning “I have already got a warning”))

5 Maya: Just think it is fucked up that Hannan and the others are not invited

6 Nabil: Let me show you the real lawyer

Hahah

7 Mark: No you should get Omar

Stephanie mentions that she already received “a warning” in the sense of a first warning to be expelled. By mentioning it in this context, she indicates that she is scared that this warning may influence the gymnasium's decision on whether to expel her or not based on the accusations of bullying. Maya reacts in line 5 by stating that it is “fucked up” that it is only their group and not the other group that is called to the meeting. This points to a central aspect of the administration's handling of the situation: They react to the slandering and the use of vocabulary in the screenshots Hannan showed them but not to acts of exposure.

In line one, Nabil mentions that he will get the “evidence”, and in line 6 he offers to be their “advokay” (sic) ‘lawyer’. In this way, Nabil draws on the institutional frame of a trial where the Clan group is the accused and he is positioned as the one who will lead their case. Later in the group's interaction, it turns out that Nabil is serious about collecting the evidence. Simultaneously with the Clan 2 group interaction, he wrote a private message to Hannan on Messenger and asked her what she told the administration. As soon as Hannan answers him, he screenshots her replies and posts them in the Clan 2 group. Altogether, he posts five screenshots of their conversation. This means that Hannan actually participates in two interactions simultaneously without knowing it. Just like wiretapping in a criminal investigation, the other members of the Clan 2 can follow the person under surveillance. The acts of entextualization carried out by Nabil differ from the earlier examples (excerpts (2) and (5)) by being a planned collection and sharing of digital evidence for later use rather than wielding social control through public exposure. By sharing the screenshots of his conversation with Hannan, Nabil constructs himself as a person who looks out for the other Clan group members and is ready to set aside norms of privacy to get digital evidence. The group treats sharing screenshots of the other conversation carried out simultaneously as turns in the ongoing interaction. The other group members discuss Hannan's written production without questioning Nabil's right to screenshot it. They agree on dismissing her arguments; in this way, the exposure of Hannan can be said to construct solidarity in the group where the screenshots are shared.

Viewed as a whole, the different acts of exposure in the conflict can be seen to create disturbance, direct and indirect accusations, but also solidarity. We have seen how these constructions of panoptic structures represent key moments in the conflict and how they seemingly lead to new acts of exposure. More generally, we could observe that panoptic practices constitute part of the participants’ polymedia repertoires.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this article, I have focused on specific instances of acts of exposure in an ongoing conflict. To summarize, the analysis illustrates how accusations before an audience are reacted upon as central contributions to the conflict—not least when these are backed up by screenshots framed as digital evidence. The Instagram post (excerpt (1)) causes a disturbance precisely because a large group of students from the gymnasium may potentially be watching. The entextualization of the post to Instagram (excerpt (2)–(5)) directs the gaze of the classmates toward the anonymous poster. The combined posting of screenshots and text in excerpt (6) puts the accused classmates and their actions on display and explains how the digital evidence included in the post was obtained. In the discussion following the post, it becomes clear that the selection of the class's group on Facebook Messenger was far from coincidental. As stated by Hannan, she “needed everyone to know”. When Hannan also chooses to share the screenshots with the school authorities, the members of the Clan group treat this sharing as transgressive behavior. This leads to the (to our knowledge) final incident of exposure taking place in the second Clan Messenger group just before the meeting with the school authorities. This time the person who is exposed (Hannan) does not know this, and hence the purpose is not to police her but rather to create a sense of secrecy and solidarity among the Clan group before the meeting.

This case illustrates why and how a panoptic perspective is relevant to sociolinguistic studies of contemporary youth life as it unfolds across offline and online contexts. The article offers a theoretical framework to address such cases. The central argument is that the participants construct panoptic structures when they expose the behavior of others. The metaphor of the Panopticon is relevant because the participants decide who will be exposed, who will be the audience, what the audience will see, and how they should interpret what they see.

The act of slandering as the trigger of the conflict analyzed here bears similarities to the case in Goodwin's study (1980), but the difference is that the conflict is fought with new technological weapons. What is new is the possibility to screenshot and entextualize ‘evidence’ and to strategically select channels from polymedia repertoires, including the composition of an audience. This technical development has resulted in changes in communication patterns. As a consequence of the affordances provided by digital devices, the ‘he-said-she-said’ pattern (Goodwin Reference Goodwin1980) has been supplemented with a ‘look-what-he/she-wrote’ pattern.

The way the gymnasium authorities handled the situation illustrates a societal need for studies that shed light on panoptic dimensions of conflicts carried out online. According to the participants, the authorities reacted to the slandering but not to the acts of exposure. The administration focused on the content in the screenshots and did not pay attention to how they travelled from a private group to the vice principal's desk. The case illustrates that, to deal with such conflicts, it is also necessary to ask who has exposed whose behavior, where, and to whom for what reasons.

The metaphor of the Panopticon synthesizes how the power to control who watches whose behavior can be used to police and control individuals. This is relevant for the field of sociolinguistics because, as we have seen, panoptic structures can be created in communication. This article has focused on how screenshots of a conversation among friends were entextualized as digital evidence in a gymnasium environment. However, in principle, the method and the theoretical framework may be applied to all cases where text is recontextualized as evidence and presented in front of an audience. In this way, the article can be seen as a step toward the development of a sociolinguistics of online exposure with a focus on the employment of panoptic structures and their consequences for social life.