I think if I'd been given the same opportunities as my peers, that would've been great. … That means if I'd started from the same starting line, learning English from kindergarten, if that'd been the case, I think it might've been different. … I think that'd have been enough. … I feel that English is really important, so I think if the starting line hadn't been so far away, if I hadn't learnt the alphabet only in Primary 3, I think my English would've been different, and so my life would've been different. (Cynthia, 2017)

INTRODUCTION

We begin this case study of Cynthia (a pseudonym), a Hong Kong graduate of an elite institution who is a high achiever in all subjects except English, with an epigraph taken from an interview in which she articulates her subjective understanding of herself and her plight. Her consistent failure to find appropriate employment in the highly competitive labour market of neoliberal Hong Kong is attributed to a perceived lack of proficiency in English—the result, in her view, of a late start from which it has been impossible to recover. This article draws on a series of interviews conducted by the first author, Steven Yeung, between 2017 and 2019 (fuller details below) in which Cynthia talks about her painful experience of learning English and her inability to find employment commensurate with her qualifications. By way of contextualisation, we begin with a discussion of neoliberalism, before moving on to the specific context of Hong Kong and the role of English as a key element in the job-seeker's toolkit. This is followed by an account of Goffman's (Reference Goffman1963) understanding of stigma and the concept of spoiled identity, which we argue provides a useful heuristic for interpreting Cynthia's self-presentation and the ways in which she positions herself across the interviews. We also suggest that the mobilisation of her particular understanding of her stigmatic condition functions paradoxically to absolve her from taking full responsibility for her perceived failure—and indicates the limited extent to which she is able to resist the imperative of neoliberal self-governance. This is followed by an account of our methodology in which we draw on Block's (Reference Block, Ayres-Bennett and Fisher2022) expanded model of positioning theory, a fuller portrait of our informant, our analysis of the data, and a discussion of what the findings suggest with regard to neoliberal subjectivity.

In bringing these perspectives to bear on a single case, which we suggest is far from unique, we aim to provide an anatomy of the current neoliberalised intersection of language, economy, and subjectivity. Our analysis reveals both the injurious nature of neoliberalism and the way in which neoliberal governmentality can never be assumed to operate absolutely.

PERSPECTIVES ON NEOLIBERALISM: MARX AND FOUCAULT

In line with theorists such as Harvey (Reference Harvey2010:10) we take the view that neoliberalism, for all its variability across time and space, is fundamentally ‘a class project … designed to restore and consolidate capitalist class power’. In doing so we align ourselves with those for whom neoliberalism is best understood as an evolving political-economic programme (Stedman Jones Reference Stedman Jones2012; Mirowski Reference Mirowski2013; Slobodian Reference Slobodian2018; Plehwe, Slobodian, & Mirowski Reference Plehwe, Slobodian and Mirowski2020), which is ideologically masked by a constantly deployed ‘rhetoric about individual freedom, liberty, personal responsibility and the virtues of privatization’ (Harvey Reference Harvey2010:10) where, paradoxically, the concept of class and all labour-based human collectives are abolished. At the same time, following scholars such as Brown (Reference Brown2019) and Moskowitz (Reference Moskowitz2019), we hold that attempts to understand neoliberalism also need to pay attention to how it gets under people's skin, colonising to a greater or lesser extent their speech and how they think about themselves, the world in which they live, and the ways in which they act. As Brown (Reference Brown2019:21) argues, Marxist-oriented understandings where the focus is on structure, economics, and ideology (e.g. Duménil & Lévy Reference Duménil and Lévy2004; Harvey Reference Harvey2010) can be complemented by Foucauldian-inspired analysis, which attends to the production of neoliberal subjectivity (e.g. Dardot & Laval Reference Dardot and Laval2013)—although we argue below that Marx was far from indifferent to the ways in which capitalism impacts on human consciousness.

The production of a specific kind of subjectivity has in fact been a constant in neoliberal theory and practice. In a newspaper interview given two years after her first election, Margaret Thatcher (Reference Thatcher1981) was explicit about how her government was tackling what she referred to as the ‘inheritance of socialism’ and ‘the collectivist society’. Having listed the privatisations already undertaken and those planned, she stated, ‘Economics are the method; the object is to change the heart and soul’ (Thatcher Reference Thatcher1981). What Thatcher wanted to engineer socially was a repurposed version of the eighteenth-century figure of homo economicus, described (presciently in the late 1970s) by Foucault (Reference Foucault2008) as an individual who is an ‘entrepreneur of himself, being for himself his own capital, being for himself his own producer, being for himself the source of [his] earnings’ (2008:226)—the kind of person who is agile and who ‘accepts reality or who responds systematically to modifications in the variables of the environment’ (2008:270). Such a person, viewing themself as embodying a bundle of marketable skills (Urciuoli Reference Urciuoli2008; Gershon Reference Gershon2011, Reference Gershon2017), which collectively comprise their human capital (Becker Reference Becker1962; discussed below), is held to be ‘eminently governable’ (Foucault Reference Foucault2008:270) having been ‘freed’ (in neoliberal terms) to pursue their own self-interest in an ever-expanding marketplace.

Integral to the idea of homo economicus is the concept of governmentality. Governmentality refers to the ways in which the modern state is held to exercise power, less through the use of brute force than through the myriad institutions at its disposal. In understanding how subjects are governed, Foucault shifted his focus from an initial concern with the ways in which the modern state governs (Foucault Reference Foucault1977, Reference Foucault2007) to governmentality in its neoliberal guise (Foucault Reference Foucault2008). Central to the latter is the cultivation of ‘choice, autonomy, self-responsibility, and the obligation to maximise one's life as a kind of enterprise’ (Rose, O'Malley, & Valverde Reference Rose, O'Malley and Mariana2006:91). These notions of specifically neoliberal governmentality have also been applied to language and educational studies (e.g. Martín Rojo Reference Martín Rojo, Tollefson and Pérez-Milans2018). Urla (Reference Urla2019:262), for example, with reference to the kind of neoliberal subject at the heart of this article, defines linguistic governmentality as ‘an assemblage of techniques … that seek to guide, rather than force, the linguistic conduct and subjectivity of the populace and/or the self’.

However, seen through a Marxist lens, homo economicus is the ‘crystallization’ (Moskowitz Reference Moskowitz2019:86) of the alienation that results from neoliberalism's ideological figuration of the market as ‘the site of veridiction par excellence within capitalism’ (Reference Moskowitz2019:85), such that, Moskowitz suggests we look to the market not only to understand the economy but to understand ourselves. But to understand oneself thusly is from the Marxist perspective a misrecognition and a form of alienation (or estrangement) from what Marx (Reference Marx and Tucker1844/1978) refers to as our species being or human essence. Such an essence Marx asserts ‘is no abstraction inherent in each single individual. In its reality it is the ensemble of the social relations’ (Reference Marx and Tucker1845/1978:145) through which human beings create and reproduce their lives under historically specific conditions. But it is the precise nature of social relations under capitalism that contemporary neoliberalism seeks to obscure. As Foucault (Reference Foucault2008:225) points out, the neoliberal worker is expected to see themself as an ‘abilities-machine’ in which their labour power (i.e. their capacity to work and deploy the skills they have acquired in exchange for wages) is re-conceptualised as ‘capital-ability’ (Reference Foucault2008:225), whereby wages are seen as a return on the capital they possess and entrepreneurially continue to invest in. However, we take the view that this ideological reformulation of labour power as capital-ability causes the concepts of exploitation and surplus value (i.e. that which is realised by the employer as profit) to disappear (Mirowski Reference Mirowski2013). From this perspective homo economicus is an ideological confidence trick that reduces human beings to the level of economic units, alienating them from the fullness of their humanity and their relations with others. Having outlined these perspectives on neoliberalism, we now turn to the case of Hong Kong and the role that English plays in the employment market.

HONG KONG AND THE ROLE OF ENGLISH

By the late 1970s and early 1980s as neoliberalism was making concrete political gains, one of its prime movers, Milton Friedman, singled out colonial Hong Kong as emblematic of what the neoliberal programme sought to achieve globally. Referring to it as ‘the freest market in the world’, he claimed it was ‘a place where there is an almost laboratory experiment in what happens when government is limited to its proper function and leaves people free to pursue their own objectives’ (Common Sense Capitalism 2010). Significantly, Friedman makes no mention of Hong Kong's colonial status and the lack of any meaningful form of political representation. The proper function of government (or in the case of colonial Hong Kong, its appointed Legislative and Executive Councils) was to leave the market to determine the fate of its inhabitants. In this respect, as Hamilton (Reference Hamilton2021) argues, Hong Kong was always different from other East Asian economies (e.g. South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore) whose capitalist transformations were state led. In fact, it was the absence of a strong state that made Hong Kong appear so appealing to the neoliberal imagination. Paradoxically, Keliher (Reference Keliher2020) argues, the recent China-directed brand of nationalism and political authoritarianism in Hong Kong is consonant with the recalibration of neoliberalism currently taking place globally. In this regard, it is suggested, Hong Kong remains an archetype, but this time of a kind of illiberal neoliberalism, which may in fact be representative of a profound transformation of neoliberal political economy in which an authoritarian form of state capitalism co-exists with ruthless competitiveness for jobs (Gerbaudo Reference Gerbaudo2021; Peck, Bok, & Zhang Reference Peck, Bok and Zhang2020)

As it has happened elsewhere (see Shin & Park Reference Shin and Park2016), neoliberalism impacted significantly on the education system in Hong Kong—not only in terms of its subjection to marketised principles, but also in terms of the requirement to produce school-leavers and graduates with the requisite amounts of ‘human capital’ (Becker Reference Becker1962), namely the skills and dispositions deemed necessary to service the economy (Tse Reference Tse, Ho, Morris and Chung2005; Cheng Reference Cheng2009; Woo Reference Woo2014; Lee, Kwan, & Li Reference Lee, Kwan and Man Li2020). In this, the role of English as an index of employability cannot be underestimated (Evans Reference Evans2016; Soto & Pérez-Milans Reference Soto and Pérez-Milans2018). Holborow (Reference Holborow2015:15) describes human capital theory as ‘the main plank of neoliberal thinking’, which seeks to extend the logic of commodification to more and more aspects of human activity. In this process, education is reconfigured as ‘an enabler of human capital development’ and ‘the crucial driver of the economy’ (2015:16). Park (Reference Park2016:456) argues persuasively that language is seen as a key skill under neoliberalism and ‘a crucial aspect of neoliberal self-development’. From this perspective, varieties of language (i.e. prestige dialects or regional varieties) as well as certain foreign languages are understood apolitically and ahistorically as neutral and transparent media of communication, forms of pure potential through which speakers can acquire and deploy their accumulations of human capital. Language is thus doubly important in the political economy of neoliberalism—at once a skill in its own right, and at the same time one to be used in the acquisition of new skills and the exercise of those already acquired. At an individual level, citizens invest (Norton Reference Norton2013) in English chiefly because good English skills are promoted as providing access to symbolic and material resources and positions of power. As Lin (Reference Lin1997) noted on the eve of Hong Kong's return to China, the neoliberal logic in the promotion of English has long been accompanied by familiar discourses of the need to improve supposedly poor teaching and of students’ personal responsibility for educational outcomes, whereby those who fail to attain the expected standards have only themselves to blame. Similar points have been made by Gershon (Reference Gershon2011), and by Park (Reference Park2016) with regard to South Korea.

In this regard, the situation in Hong Kong has not changed and the differential distribution of linguistic resources across different social groups today continues to contribute to the reproduction of inequalities. It is taken for granted that professional and skilled workers should possess a high level of English proficiency, which has to be demonstrated at the job-hunting stage. This is one of the key moments where the screening and gatekeeping function of English is realised, causing anxiety and insecurity especially to the less privileged—something we see exemplified in the case of Cynthia. As Gal (Reference Gal1989:352) noted (with regard to verbal interaction in gatekeeping encounters generally), failures on the part of those seeking entry to deploy the requisite linguistic resources are not viewed as evidence of linguistic difference, ‘but as indications of personal qualities, and thus as objective grounds for rejection and devaluation of those attempting access’.

STIGMA AND SPOILED IDENTITY

As stated in our introduction, we argue that Goffman's concept of stigma and spoiled identity are pertinent to our interpretation of Cynthia's self-presentation and specifically the ways in which neoliberalism gets under the skin. In Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity Goffman (Reference Goffman1963:11) draws on a wide range of commentary and personal narratives in a sustained meditation on the ways in which ‘[s]ociety establishes the means of categorising persons and the complement of attributes felt to be ordinary and natural for members of each of these categories’. His focus is on what happens when an individual is perceived to possess an attribute (or to lack one) which is held to be at odds with what is conventionally expected and the ensuing re-evaluation and potential discrediting and spoilage of identity that can occur. This has parallels with Foucault's (Reference Foucault1973) concept of gaze (discussed below), whereby the individual may be revealed as falling short of conventional expectations. However, stigma is not simply a matter of attributes, but of how the possession or lack of attributes is socially perceived and internalised by the individual. The spoilage of identity is said only to occur when the stigma is recognised by the bearer as discrediting.

Goffman (Reference Goffman1963:14) identifies three main types of stigma—those arising from what he calls ‘abominations of the body’ (e.g. physical disabilities), those related to ‘blemishes of individual character’ (e.g. varieties of moral failings and those inferred from addiction, unemployment, non-normative sexuality, possession of a criminal record, etc.), and those which are ‘tribal’ (e.g. related to race, nationality, and religion—as well as social class). Goffman also distinguishes between those individuals whose stigma is visible or known about and who are discredited as a consequence, and those whose stigma is not immediately visible, but discoverable and therefore potentially discreditable. In both cases there is a need for the bearer to manage the stigma socially, often entailing a considerable amount of anxiety—whether dealing with the consequences of the stigmatising gaze or attempting to avoid discovery.

In the case of Cynthia, we suggest that Goffman's second category is the most relevant. Although her perceived lack of proficiency in English may seem to be of a lesser order than some of the ‘blemishes’ listed, Goffman is at pains to point out that stigma can be the result of varied and seemingly less momentous forms of differentness but still be very consequential for the bearer. Frequently accompanying the concept of stigma is the notion of shame, which in Goffman's view is triggered by the social gaze of those who are ‘normal’. In their study of economic inequality in societies across the Global North, Wilkinson & Pickett (Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2009) show that social anxiety and shame are key features of the most highly unequal societies. Given Hong Kong's reputation as a particularly unequal society (e.g. Wu Reference Wu2009; Oxfam 2018), it is not surprising that anxiety and shame are recurring features of Cynthia's presentation of herself, particularly with reference to her proficiency in English. Having outlined the key elements in Goffman's theorisation of stigma and spoiled identity we now explain how we analyse the data.

POSITIONING THEORY: AN EXPANDED MODEL

To examine Cynthia's spoiled identity, we need an analytical framework that is sensitive to the wider social and institutional structures, as well as to the individual's internalisation of the stigmatising social gaze. To this end, we turn to Block's expanded model of positioning theory (hereafter PT) (Davies & Harré Reference Davies and Harré1990; Van Langenhove & Harré Reference Van Langenhove, Harré, Harré and Langenhove1999). Originally developed in discursive psychology, PT has increasingly been applied to identity research in applied linguistics (Kayi-Aydar Reference Kayi-Aydar2019). Positioning refers to the ‘discursive process whereby people are located in conversations as observably and subjectively coherent participants in jointly produced storylines’ (Davies & Harré Reference Davies, Harr, Harré and Langenhove1999:37). Concerned with rights, duties and obligations in social episodes or communicative events, PT is originally a tri-polar framework consisting of mutually determining constituents, namely positions, storylines, and speech acts, which interlocutors jointly construct. A position refers to ‘a cluster of beliefs with respect to the rights and duties of the members of a group of people to act in certain ways’ (Harré Reference Harré and Valsiner2012:198). As is evident, the model is predominately concerned with identity construction in local interactions.

While retaining the focus on local interactions, but with the aim of capturing more of the complexity of ‘acts of identity’ (Le Page & Tabouret-Keller Reference Le Page and Tabouret-Keller1985:14), Block proposes an expanded model of PT (see Figure 1) by incorporating constructs from political economy, sociology, anthropology, social theory, cultural studies, human sciences, and geography. He argues that PT should foreground the sociohistorically situated nature of positioning and include an explicit consideration of power. In particular, drawing on Foucault's notions of discursive formations and the ‘gaze’, Block (Reference Block, Ayres-Bennett and Fisher2022) considers ‘rights and duties’ as a mediating component between ‘compliance, acquiescence, acceptance vs. denial, defiance, resistance’ and ‘gaze as power residing in institutions’. The former contributes to ‘positions’ (‘as particular types of people’) directly, while the latter is engendered by ‘discursive formations as institutional frames’. Gaze, in the Foucauldian sense, refers to the ways in which subjects are produced through their imbrication in the disciplinary and surveillance mechanisms found in schools, hospitals, prisons, and so on, in which the scrutiny of the institution results in the production of a particular kind of knowledge of the scrutinised. As suggested above, this aligns well with Goffman's (Reference Goffman1963:2) idea of ‘normative expectations’ essentially shaped by such mechanisms. In what follows we refer to the English language gaze to mean the ways in which speakers are positioned, understood, and evaluated by institutions and their representatives in terms of their proficiency in English. Block's expanded model is proposed with a view to addressing the power exerted by institutions in the form of the gaze in a (reported) social episode and to pinpointing how the gaze is received. A sociolinguistically informed examination of relevant speech events (as undertaken here), as Gal (Reference Gal1989:353) argues, shows ‘how institutions constrain the options of speakers, and how speakers use the microstructures of interaction to reproduce, and on occasion transform …, their own often stigmatized social identities’. Viewed thusly, Block's model can be seen as a sociologically complex attempt to operationalise a view of identity in which the role of shaping structures (e.g. class position, geographical location) and institutional frames are recognized. From this perspective, identities are not only brought about in interaction, they are also brought along (Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman, Antaki and Widdicombe1998; Baynham Reference Baynham, Dervin and Risager2014).

Figure 1. An expanded model of positioning theory (Block Reference Block, Ayres-Bennett and Fisher2022).

PORTRAIT OF CYNTHIA

We now turn to the protagonist of this article, Cynthia. She was born in 1993 into what she describes as a ‘deprived, under-educated family’ in Hong Kong. Before attending kindergarten (as would have been normal in Hong Kong), her family relocated to Guangdong Province, China, where she used Cantonese at home, Mandarin at school, and started learning English in primary school when she was nine years old. She began her secondary education in China but completed it in Hong Kong when she returned there with her family in 2008 at age fifteen. Her language-learning experience is therefore different from that of her Hong Kong counterparts, who normally use Cantonese at school and start learning English from kindergarten. After returning to Hong Kong, she continued her secondary education in a bilingual government secondary school. She performed well academically except in English and relates fearing that she would not obtain the minimum of level 3 (out of a possible 7) in English in the public examinations which determined entry into university. In fact, she obtained a level 3 in English and was admitted to an elite university in Hong Kong to study economics.

The first author, Steven Yeung, first met Cynthia in a university foundation English class he taught and was impressed by her diligence. She performed well in her major studies, as shown by her eventual first-class honours degree. However, as she repeatedly says (details of the research interviews below), she struggled with English throughout the four years of her university life. As a high-achieving student, she was successful in securing job interviews in the business, marketing, and banking sectors in her final year. However, she was unsuccessful in getting a job and attributed her failure to her level of English. Given the stark contrast between Cynthia's overall academic achievement and her perceived lack of competence in English as well as her constant association of (potential) failures in life with English, Yeung invited Cynthia, with whom he had developed a relationship of trust as her teacher, to participate in this exploratory study.

DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

The data, which comprise interviews with Cynthia (C), her diary entries related to her encounters with English, and observational field notes made by Yeung (Y), were collected between January 2017 and September 2019. The data collection period was an important time of transition for Cynthia because she was working towards her final examinations while preparing for the aforementioned job interviews. Over this period Yeung interviewed Cynthia formally on five occasions and chatted with her informally approximately six times, always in Cantonese. The duration of all of the interviews and chats ranged from forty minutes to two hours. All of the interviews were semistructured, recorded, transcribed verbatim, and translated from Cantonese to English as literally as possible, while all the chats were unstructured and recorded in the form of field notes. The first interview with Cynthia was essentially a life story interview (Linde Reference Linde1993) with a focus on her language learning. This provided a baseline narrative, elements of which Cynthia referred to in follow-up interviews. Additionally, Cynthia agreed to keep and share a diary (mainly in English) in the first eighteen weeks of the study to record any events she felt were relevant to her language learning and use. This allowed Yeung to follow up on events that might not otherwise have emerged in the interviews. Together, these form an assemblage of narrative data that tell her story.

The analytical steps were informed by an iterative approach. Data were initially analysed right after collection to inform further data collection. We then generated a list of events and characters in Cynthia's narratives and traced how she positioned herself, and was positioned by others, in relation to English learning and how she epistemically and affectively evaluated relevant events—as well as how she positioned herself in relation to her interviewer. After this initial analysis, we found Cynthia's stigmatised subject positions were particularly salient. We then re-read the data paying particular attention to how these positionings emerged, drawing on Block's expanded model of PT and in the light of Goffman's (Reference Goffman1963) concept of stigma and spoiled identity.

CYNTHIA'S POSITIONINGS

In the first interview, in response to Yeung's questions about her experience of learning English, Cynthia recounts a number of stories from different stages in her life, all of which are negative and serve to confirm her contradictory attitude towards it while underlining her sense of having a spoiled identity. At the outset of the interview Cynthia makes it clear (see epigraph quotation) that her English and—significantly—her life would have been different if she had started learning the language in kindergarten. In framing her narrative in this way Cynthia may be said to be invoking what has been described as an ‘origin myth’ (Engel Reference Engel1993). Writing about the ways in which the parents of children with disabilities tell their stories, Engel shows how they frequently foreground a moment when all that followed began.

Origin stories are a distinctive form of narrative. In their account of how something ‘began to be’, such stories connect past and present, clarify the meanings of important events, reaffirm core norms and values, and assert particular understandings of social order and individual identity. (Engel Reference Engel1993:785)

In what follows we suggest that the storylines produced are variations on, or responses to, this foregrounded origin myth that pinpoints how her stigma began to be. Extract (1) marks a new storyline after the origin-myth framing as Cynthia recounts her school-girl experience of being forced to relinquish the opportunity to do enhancement mathematics (for students with good results in mathematics only) due to having to take a remedial English class (for students with unsatisfactory results in English). Such enhancement and remedial classes are common in many Hong Kong secondary schools.

This exemplifies one of Cynthia's recurring positions as a victim—“I felt they were picking on me” (line 10)—at having to face various constraints because of her level of English. As her former teacher and a researcher conducting the first interview, Yeung mainly acknowledges Cynthia's responses encouragingly throughout this exchange, while his use of laugher can be seen as an attempt to establish rapport—thereby prompting her to elaborate. By telling this story, Cynthia positions herself as a powerless victim of the school's English language gaze, which, on the one hand, denies her the right to choose the mathematics enhancement class and, on the other, categorises her as someone required to submit to institutional power with a duty to remedy her underperformance in English. Her choice of language indicates her sense of lack of agency and the extent of the school's power over her—“they didn't allow me” (lines 6–7), “[they] made me go” (line 7), “why did they not let me” (line 10), and “they had to force me” (line 11). Although having to acquiesce to the arrangement, she positions herself in affective terms as “REALLY not pleased” (line 8) and “scared” (line 12) at being deprived of her wish to study mathematics and the obligation to study something she states she “didn't want to learn” (line 12). Her choice of words in line 28 (“free from their clutches”) vividly captures the loss of agency she experiences in acquiescing to institutional authority, and the concomitant feelings of stress this compliance provoked (line 30).

Her assessment of the lessons as unhelpful is attributed to the English-only pedagogy, although this is something normally expected in the Hong Kong English classroom. However, her emphasis is less on the shortcomings of the monolingual pedagogy than on herself as someone for whom it was inappropriate—“there was no way for me, with the ability I had” (line 20) and “I hadn't adapted to that” (line 23). These comments echo indirectly the origin myth storyline of the life-determining late start in English. This extract is also indicative of the constant contradictions she introduces as she recounts her English learning trajectory. On the one hand, there is her initial disadvantage of having missed out by not studying English in kindergarten, but on the other, there is her repeatedly declared wish throughout the interviews to master this language, as well as her strong affective rejection of it.

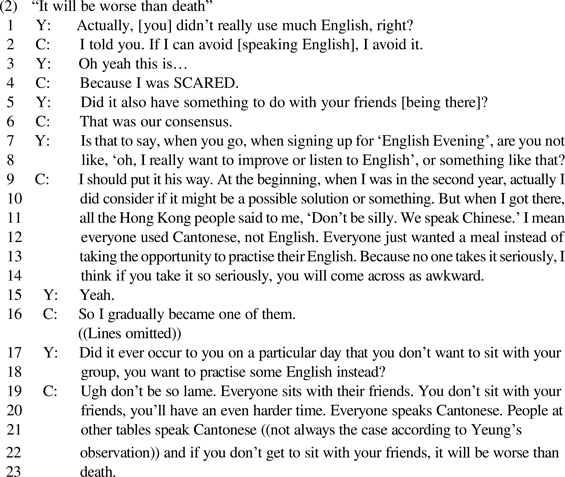

Notwithstanding these complex feelings about herself, her perceived need to learn English and her attitudes towards it, during her university studies Cynthia was proactive in joining an English enhancement activity known as an ‘English Evening’, which was attended by both international students (often as English-speaking helpers) and local students (as participants). Prompted by the taken-for-granted institutional imperative for students to improve their English, this typical Hong Kong university activity aims to enhance spoken language ability through thematic talks, activities, and conversations in English. Having been told by Cynthia how important English was to her countless times, Yeung was surprised when he accompanied her to several of these events to see that she rarely spoke any English. He also noted that the organiser tried to arrange for participants to sit randomly, but that Cynthia and her friends found a way to stick together and spoke Cantonese only. In extract (2), from a subsequent interview, Yeung asks Cynthia about this.

This extract shows the omnipresence of the English language gaze. Yeung starts with his observation of Cynthia's lack of English use at the event to prompt a response (line 1), which is the first instance of invoking the gaze. She immediately dismisses his question and rejects his gaze by positioning herself as someone who avoids English wherever possible (line 2) and considers this as something that Yeung should have understood from his ongoing study. Cynthia's avoidance of English is arguably a strategy for managing her spoiled English-learner identity and her anxiety about English use, as shown by her strongly affective clarification in line 4 “Because I was SCARED”.

Nevertheless, attending the ‘English Evening’ without speaking English is counterintuitive because students are expected to communicate in English only, and the event is policed by the organiser, which can be understood as another materialisation of the English language gaze. In fact, Cynthia noted her compliance with the gaze in the first ‘English Evening’ of the year in one of her diary entries (written in English).

This Tuesday night I have attended English night. The leader of my group has actively talked with us so that I should replied her in English which means it provided me an opportunity to practice English. I asked her how she can speak English so great, she said she has practiced a lot while she was exchanging. I just felt I was so poor that my English did not improve even after my exchange, so sad.

Because the “leader” (event helper) spoke to her in English, Cynthia felt obligated (“should”) to speak English and assumed her duty as a good participant and English learner on that occasion. This contradicts her claim in extract (2) that “Everyone speaks Cantonese” (line 20).

Recalling this and clearly not feeling not completely satisfied with the answers, Yeung asks if it was also because of the presence of her Cantonese-speaking friends (line 5). Cynthia explains that they reached a consensus on language use, that is, speaking Cantonese. Asking if she has ever intended to improve her English through this event in line 8 and lines 17–18, Yeung projects the English language gaze again. Cynthia clarifies that she once considered that English Evenings “might be a possible solution” (line 10), thus—by mentioning a solution—indirectly indexing an unstated problem. Again, we see this as an invocation of the stigma of her debilitating late start in the origin myth storyline. Cynthia rejects the gaze by effectively claiming that her avowed wish to practise English is at odds with the expectations of her group—“no one takes it seriously” (line 13). When the chance arises, she complies with the social gaze that grants her a right to speak Cantonese and enjoy dinner, and, crucially, in order to avoid being seen as an “awkward” (line 14) English speaker by her friends. Her last turn (lines 19–23) further dismisses Yeung's questions (e.g. “don't be so lame”) as insufficiently cognisant of the difficulties she faces. Not being in her friendship group would entail “an even harder time” (line 20) which would be “worse than death” (lines 22–23). Cynthia's choice of words in lines 20–21 is significant, as they indicate the omnipresence of the English language gaze even when in the company of her Cantonese speaking friends. Although not discredited by having to speak English in front of them, she remains painfully aware of being discreditable were she to be exposed. Paradoxically the English language gaze is evident here through her avoidance of English. Although being among her Cantonese speaking friends at the event is a refuge, the deeply internalised English language gaze acts on her by default, no matter whether she acquiesces to it (e.g. speaking to the English speaking “leader”) or otherwise (e.g. speaking Cantonese to her friends). This extract highlights the pervasive social anxiety and shame Cynthia associates with speaking English in social settings and is a powerful reminder of the centrality of these emotions in the operation of stigma and the difficulty of managing it. It is also a reminder of the point made by Wilkinson & Pickett (Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2009), that these emotions are particularly prevalent in highly competitive unequal societies.

Cynthia also evoked her spoiled identity position in her accounts of other activities such as job hunting and pursuing further studies. Typical of Hong Kong high achievers, she sought a difficult-to-obtain management trainee position by applying to several large companies. In some of the research interviews conducted shortly before her graduation, she repeatedly mentioned her difficulty in performing well in job interviews. Job interviews in Hong Kong, especially those in large companies, are conducted at least partially in English, which is in line with the widely circulated discourse that English is important to business and economic success. In extract (3), she assesses her interview performance in relation to English use.

In this exchange, Cynthia describes herself as “screwed” (line 2) whenever she gets to the interview stage. She underscores how fierce competition is and ascribes her failure to her English being a “handicap” (line 4) that prevents her from performing well compared to other applicants. In an earlier interview she had mentioned this, although nuancing her self-assessment as follows: “Actually, to a great extent, I don't screw up my interview…. I mean I don't screw up because of my thinking or my ability to express myself, I screw up because of my English”. This can be interpreted as acceptance of the onus (or in PT terms, ‘duty’) to speak good English in job interviews, but it is also indicative of her positive view of her own ability to think. It is her ability in English that is the discrediting attribute that she wants to conceal and whose appearance will “give the game away” (line 4) rather than any other aspect of herself. But English is a key element in the high-achiever's skillset in Hong Kong—and as a discreditable person in Goffman's (Reference Goffman1963:57) formulation, Cynthia is aware of her inability to ‘manage information about [her] failing’.

In line 6, Yeung projects the English language gaze again by seeking confirmation that she found it hard to express herself in interviews. As a high-achieving student who has always wanted to get the best results, it is interesting that she claims she muddles through. This is similar to what she did during academic presentations observed by Yeung. She refused to memorise a script (something many Hong Kong students do), despite her anxiety about speaking English, because she thought improvisation is the key to performing well. From this perspective English is the culprit, preventing her from speaking impromptu, thus rendering her powerless. Although Cynthia does not distinguish between her ability in written and spoken English, it appears that in terms of her perceived shortcomings she is referring to her impromptu spoken English as the main impediment to the realisation of her potential. She has, as we have pointed out, a first-class honours degree from an elite institution and would have written much of her coursework in English. In addition, she uses her written English in job applications and has no problem in getting job interviews. The problem occurs—or as she puts it, “you … give the game away” (line 4)—when unplanned speaking is involved.

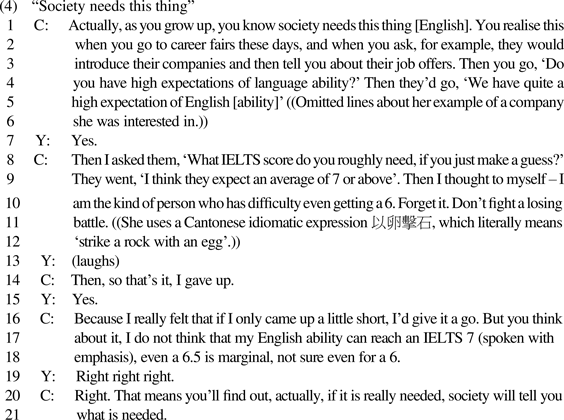

In extract (4) Cynthia again constructs a storyline of being unable to meet the expected standard in English, this time with reference to her experience at a career fair. Shortly before this conversation, Yeung asks why she thinks English is important.

Here, Cynthia highlights the necessity of possessing a desirable, institutionally certified English level in society by reflecting on a conversation she had at a career fair. The necessity for a specific kind of English language skillset can be understood in terms of the English language gaze projected by the labour market which Cynthia conflates significantly with “society” (lines 1, 20)—a point we return to in our discussion. She begins in line 1, by saying “as you grow up”, implying a learning process about the linguistic facts of working life in Hong Kong. Her use of the pronouns “you” and “they” in lines 1–4 is noteworthy as they allow her to generalise from her experience to construct a general truth about what society needs. She evaluates her English ability in examination terms in lines 10–11 and positions herself as an ill-equipped applicant who is unable to achieve even a much lower standard. That said, her suggestion that the possibility of coming up just “a little short” (line 16) in terms of English ability indicates her belief in herself as capable of doing the job (“I'd give it a go”). However, the thought is immediately banished as she recognises that society will tell her otherwise. Here Cynthia acquiesces under the English language gaze and assumes her spoiled English learner identity yet again.

DISCUSSION

What then, we might ask, does Cynthia's experience tell us about the ways in which neoliberalism gets under the skin, the extent to which (echoing Thatcher) it impacts on the human heart and soul in the production of homo economicus? With regard to the entrepreneurialism that Foucault sees as integral to this one-dimensional figure, Holborow (Reference Holborow2015:87) writes:

The fact that the individual entrepreneur may crash on the rocks of social realities, that she may flounder amid the fall-out of a market crash, or that she may discover that her entrepreneurial skills get her nowhere in the real world, does not enter Foucault's tableau.

Although true, this may be harsh on Foucault, who is not concerned with neoliberalism's individual victims but rather with the idealised figure it seeks to produce. Drawing on Block's expanded model of PT we have argued that Cynthia positions herself from the outset as having a spoiled identity, her perceived weakness in English is a source of anxiety and shame which is repeatedly revealed under the stigmatising institutional gaze projected by the school, the university, her interviewer, the Hong Kong labour market, and society. As far as the ideal described by Foucault is concerned, Cynthia may be said to have come up short in much the same way that the North American working-class informants interviewed by Silva (Reference Silva2013) do. After years of hard work and obtaining a first-class degree from an elite university, she finds herself in a highly competitive job market with a skillset that is deemed deficient in one key area. Curiously though the ‘cultural trope of individual responsibility’ identified by Wacquant (Reference Wacquant2010:231) as one of the institutional logics of neoliberalism is not deployed by Cynthia's in her positionings and storylines. Nor, unlike many of Silva's (Reference Silva2013) informants, does she blame herself explicitly for the situation in which she finds herself. Rather, following Goffman (Reference Goffman1963:21), we see her stigma being deployed altogether differently, along the lines of the medical patient with a disfigurement.

It is the ‘hook’ on which the patient has hung all inadequacies, all dissatisfactions, all procrastinations and all unpleasant duties of life, and he (sic) has come to depend on it not only as a reasonable escape from competition but as a protection from social responsibility.

Looking at the data through a Foucauldian lens, Cynthia may be said to approach learning English as a form of investment. As Foucault (Reference Foucault2008) suggests, to form a good abilities-machine with a high level of human capital, one requires initial educational investments in the form of, for instance, early familial and school socialisation. Indeed, Cynthia could be held to attribute implicitly her linguistic underachievement, as measured by the system and confirmed by her spoiled sense of self, to insufficient initial investments in a key area of her linguistic skillset which makes her overall capital accumulation an uphill battle. In addition, it could be argued that her conflation of the labour market which requires proficiency in English with society is an indication of her recognition of the market as the site of veridiction (to echo Moskowitz again) in contemporary Hong Kong. The two are one and the same thing. Her unease during the ‘English Evenings’ while speaking Cantonese with her friends is a powerful reminder that even when she is not directly subjected to the English language gaze as in a job interview, she remains indirectly subjected to it while socialising with others—with whom perforce she is in competition. To that extent Cynthia may be said to have internalised the prevailing neoliberal discourse that English language proficiency promises profits and success and a view of society as site of individualised competition. As a calculating and rationalised entrepreneur of herself hoping to reap the promised benefits, she finds it imperative to keep trying to invest in English, as a way to increase her competitiveness. Attempting to ‘manag[e] [her] own human capital to maximal effect’ (Fraser Reference Fraser2003:168), she has no choice but to alternate between anxiously investing in English and anticipating losses. However, she has come to the realisation that her attempts at investment yield a poor return and that the endeavour is a ‘losing battle’.

Turning then to a Marxist perspective, what sense can we make of Cynthia's positionings? Building on Marx's early work on alienation, Lefebvre (Reference Lefebvre2002) points out that alienation in late capitalism is an infinitely complex dialectical process. Not only are people alienated from their species being by being treated as, or made to think of themselves as, abilities-machines or embodiments of capital-ability, they actively seek to assuage these feelings through ‘disalienating’ activities, which in turn can give rise to enhanced new feelings of alienation. Cynthia's repeated disalienated returns to learning English (e.g. her course with Yeung at university, the ‘English Evenings’, and other activities not drawn on in this article) and her invariable new alienations leaving her feeling worse about herself than before can be seen as an example of this dialectical movement. In addition, Lefebvre writes (2002:214):

Alienation is the result of a relation with ‘otherness’, and this relation makes us ‘other’, i.e., it changes us, tears us from ourself and transforms an activity (be it conscious or not) into something else, or quite simply, into a thing.

From this perspective Cynthia's alienating experience of learning English others her (“my English is a handicap”) and is reified in the stigma of her spoiled identity, which is borne with all the shame and suffering of one of Goffman's cases. However, her refusal to take personal responsibility for her English and her dogged adherence to the origin myth of the late start suggest that, despite what Lefebvre refers to as the mutilations of alienation, her heart and soul have not been made entirely in the image of homo economicus. This self-positioning is crucial for her and for our assessment of her. In positioning herself thusly Cynthia may be seen to resist to an extent the all-powerful English language gaze and the self-blaming that her failure (from the perspective of neoliberalism) should entail. Cynthia makes it clear from the outset that she knows that the market is not a place where equals meet and that not all who enter it have had the same opportunities. Such a position suggests that the ‘ideological haze of the market’ (Moskowitz Reference Moskowitz2019:95) has been penetrated, at least partially, by Cynthia, although she continues to acquiesce to its rules.

CONCLUSION

By way of conclusion we suggest that our analysis draws attention to the inequities of neoliberalism as an ideology and as a multifaceted shaping structure (as per Block's expanded model of PT), and specifically to the damage it inflicts on those whose English language skills are judged to be substandard. It also draws attention to the central role that language, and specifically English, plays in so-called human capital development in the Hong Kong setting. The Foucauldian lens illuminates how ‘the techniques of the self are integrated into structures of coercion and domination’ (Foucault Reference Foucault1993:203)—specifically how Cynthia's linguistic conduct and neoliberal subjectivity are shaped and produced through the manipulation of her hopes and desires in a ‘free’ market and the regime of truth/normality determined by the market. The Marxist lens, by contrast, allows us to account for her suffering in terms of alienation from her species being, while at the same time countering the ideological sleight of hand whereby neoliberalism seeks to re-conceptualise labour power as capital-ability. Together they allow us to make greater sense of Cynthia and the precise nature of her stigmatic condition. Furthermore, in line with Park & Wee's (Reference Park, Wee, Rubdy and Tupas2021) recommendations for further research, the focus on alienation allows us to explore in greater depth the affective impact of neoliberalism on individual subjectivity. Our discussion also sheds light on the formation of her spoiled identity and the resulting consequences under the pervasive English language gaze in Hong Kong, where only the ‘fittest’ will survive but the promise of English remains integral to the blandishments of neoliberalism. Cynthia's case is also a reminder that neoliberalism is not just ‘out there’, but also ‘in here’—in the minds of the subjected. But it also shows that, for all the damage done, the production of homo economicus is far from guaranteed.

APPENDIX: TRANSCRIPTION CONVENTIONS

- WORD

emphasis

- ((word))

transcriber's comments

- (word)

paralinguistic features such as laughter, sighing

- [word]

additions for clarity of reading