INTRODUCTION

This article introduces and analyses the discourse of five members of a British support group for transgender youth. In the west, trans identity is typically understood to mean an identification which differs from the sex category one was assigned at birth. This disrupts long-standing, hegemonic, essentialist ideas of gender and sexuality and, as reported in the data which follows, trans people's bodies are frequently questioned and contested as a result. Through their interaction as a group, the participants in this study describe moments where this happens and then respond affectively and collaboratively to them. I argue that they use language strategically to recontextualise discourse which seeks to marginalise and constrain them, focusing in particular on their embodiment.

Within the sociolinguistic literature, theorisation of embodiment has often drawn upon Williams’ (Reference Williams1977) sociological framing of language as not only a system of signs but a material process. Recent analyses have exemplified the role of, for instance, hand gestures, posture, clothing and makeup choices, and facial expressions in communicating identities (e.g. Hall, Goldstein, & Ingram Reference Hall, Goldstein and Ingram2016; Corwin Reference Corwin2017; Calder Reference Calder2019). In this article, however, I take a poststructuralist approach to prioritise ‘the discursive dimension of embodiment’ (Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz, Hall and Coupland2016:182). More specifically, this study adds to the growing body of evidence (e.g. Zimman Reference Zimman, Zimman, Davis and Raclaw2014; King Reference King2016; Konnelly Reference Konnelly2021) that embodiment can be conceived of not only in terms of its physicality, but as a symbolic resource made real through interaction. Furthermore, this analysis demonstrates that language can be used creatively by marginalised groups to resist, recontextualise, and ultimately undo discourse which seeks to oppress and constrain them.

I take a queer linguistics approach here, which means that my analysis has the political aim of revealing and problematising normative, constraining ideologies associated with gender and sexuality (Motschenbacher & Stegu Reference Motschenbacher and Stegu2013). Queer linguists critique discourses which render particular groups, bodies, or practices ‘strange’ on the basis of their divergence from the heteronormative ideal (e.g. Morrish Reference Morrish, Livia and Hall1997; Peterson Reference Peterson2010; Turner, Mills, Van der Bom, Coffey-Glover, Paterson, & Jones Reference Turner, Mills, Van der Bom, Coffey-Glover, Paterson; and Jones2018). I do this here, but I also attempt to respond to Zimman's (Reference Zimman, Hall and Barrett2020, Reference Zimman2021) call for a trans linguistics, which prioritises the perspective of trans people and which has a positive impact on trans people's lives. Zimman demonstrates that many sociolinguistic studies into trans subjects thus far have evaluated their interaction on the basis of a narrow, cisnormative understanding of gender.

Cisnormativity concerns the salient assumption that ‘the gender assigned to an individual at birth is the same as the gender identity experienced by the individual, and remains so throughout the individual's life’ (Ericsson Reference Ericsson2018:140). Cisnormativity is reproduced in everyday interaction, such as through the use of binary gendered terms (like ‘madam’ or ‘sir’) to refer to non-binary or gender-nonconforming people. In this way, cisgender identity (whereby one's gender identity reflects the sex assigned at birth) is repeatedly positioned as ‘natural, healthy, desirable and socially expected’ (Ericsson Reference Ericsson2018:146), which leads to transgender identities being marginalised. Cisnormativity thus reflects the privileged position held by those who are not trans, whereby they do not need to question the apparently ‘normal’ status of their own gender identity—a perspective which can be found in some sociolinguistic work seeking to document trans people's language use. As Zimman (Reference Zimman, Hall and Barrett2020) argues, analyses have sometimes judged trans speakers both for deviating from traditional binary gender norms, and for not deviating from these norms enough; such work may be viewed as cissexist, or discriminatory against trans people. A trans linguistics approach, instead, views trans speakers’ language in terms of its creative and nuanced potential to disrupt gendered categories and navigate cisnormativity (Konnelly Reference Konnelly2021). By focusing, in this article, on how young trans people negotiate their marginalisation to ultimately claim agency over their own embodiment, I aim to respond to the call for trans linguistics. However, I also reflect on the impact of my positionality as a cisgender researcher on these efforts.

Before this, I consider below the sociolinguistic conceptualisation of embodiment in relation to trans speakers. I then review key concepts which frame the perspective on identity construction underlying my approach. Following that, I provide an account of the young people involved in this study, before presenting the data itself.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Trans embodiment

In the context of trans people, Borba & Ostermann (Reference Borba and Ostermann2007:132) define embodiment as ‘the appropriation of signs that index gender and sexuality’; the body itself is an important site for the presentation of oneself as gendered, but so are the symbols and signs used in this endeavour. As Bucholtz & Hall (Reference Bucholtz, Hall and Coupland2016) demonstrate, embodiment has been understood for some time to be a discursive phenomenon; they consider Butler's (Reference Butler1990, Reference Butler1993) theorisation of the body as gendered through the repetition of performative acts which society perceives of as gendered, meaning that discourse both reinforces and challenges ideological notions of the body itself. They cite, as an illustration of this, Braun & Kitzinger's (Reference Braun and Kitzinger2001) account of how dictionary definitions of genitalia rely on gendered ideologies which position women as passive and men as active. In this way, embodiment may be viewed as a dialogic process: the body is ‘co-constructed in the back and forth of speakers and hearers’ (Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz, Hall and Coupland2016:183).

As King (Reference King2016:361) reminds us, to argue ‘that bodies are discursively constructed is not to suggest that they are not important’, but instead that ‘the relationship between bodies and discourse is one of co-construction’. King demonstrates this through discourse analysis of New Zealand classroom interactions, where participants negotiate the prevalent cultural model of viewing genitals as either female or male, and together find creative linguistic ways of articulating (and thus bringing into being) intersex genitalia. Similarly, Zimman's (Reference Zimman, Zimman, Davis and Raclaw2014) discourse analysis of an online forum for trans men in the US also identifies creative linguistic means employed by interlocutors to describe genitalia. Through their discourse, his participants redefine what is ‘male’ or ‘female’ when discussing the body, so the lack of a penis or possession of a vagina does not prevent them from identifying or being recognised as men. In this way, Zimman argues, the body itself is discursively produced.

Similarly, Konnelly (Reference Konnelly2021:77) argues that language is often used by trans people in creative and strategic ways, meaning speakers might dialogically construct different types of embodiment depending on the context. Konnelly shows how non-binary people accessing medical care in Canada adapt their language to ensure that doctors outside of specialist gender-identity clinics understand them. For example, many trans and non-binary people assigned female at birth have surgery to remove their breast tissue and contour their chest, typically referred to as ‘top surgery’, yet a non-binary person in Konnelly's dataset referred instead to their ‘double mastectomy’ while in a mainstream medical context. Although this aligned them inaccurately with a cisnormative understanding of womanhood, it allowed them to ensure they received an appropriate level of care. Importantly, Konnelly argues, rather than capitulating or assimilating towards mainstream norms, such practice represents a negotiation of high-risk interactions whereby a non-binary person's marginal status could have real-life implications (Reference Konnelly2021:78). Again, this demonstrates that the body itself is produced through discourse—and that this is always context-dependent.

The framing of embodiment as dialogic is a logical extension of the now well-established view in sociolinguistics that a person's sense of self is ‘fundamentally the outcome of social practice and social interaction’ (Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2011:1). Yet this view is not universally shared. Regarding trans people, a dominant cultural perspective of cisnormativity continues to position embodiment in much more literal terms; it is believed by many that ‘the category of woman and/or female must be centered on bodily sex (as a biological category)’ (Zanghellini Reference Zanghellini2020:3). Even in cases where the existence of trans people is acknowledged, their embodied experience is subject to constant scrutiny and policing. In particular, institutional boundaries exist around trans people's identity; in many countries, those wishing to access medical support must first be evaluated as genuinely trans, usually via psychiatric evaluation which assesses them in line with pre-determined criteria. Borba & Milani's (Reference Borba and Milani2017) sociolinguistic analysis of interactions between clinicians and trans patients in a Brazilian gender-identity clinic demonstrates this, as they find that ‘allegedly rational taxonomies of what should be felt and experienced in order to count as “authentically” transgender’ (Reference Borba and Milani2017:12) are established through medical discourse in the clinical context. Crucially, this notion of authenticity is centred on heteronormative ideology which positions femininity and masculinity as polar opposites, each with defined gender roles which reflect the supposed complementarity of women and men. Borba's (Reference Borba2019) analysis of an interaction taking place in this setting shows clinical staff actively shaping patients’ discourse to conform to this restrictive ideal, offering a particularly clear example of dialogic identity construction.

Dialogic identity construction

In the data which follows, a group of young trans people talk about their own experiences of being subjected to policing and scrutiny based on cisnormative and heteronormative assumptions. They describe specific moments where their embodiment is evaluated and mischaracterised, sometimes quoting their interlocutors directly, and then respond to the anecdotes collaboratively. Tannen (Reference Tannen1989) refers to this as ‘constructed dialogue’; because the retelling of events allows speakers to present a particular version of a story and therefore themselves, even apparently verbatim quotes are part of a storyteller's identity construction. Our analysis of constructed dialogue allows us to consider ‘the ways in which speakers evaluate and position themselves in relation to the voices they invoke’ (Pichler Reference Pichler2021:6), as well as how speakers invite their interlocutors to align themselves with that positioning (Cashman Reference Cashman2018:81). In this way, the whole telling of a story—including the dialogue within it—is part of identity construction; it is a mechanism by which speakers can position themselves as particular types of people in relation to (a) one another, (b) broader ideological identity categories, and (c) the specific moment of interaction. Bucholtz & Hall (Reference Bucholtz and Hall2005) refer to this as the positionality principle.

A key mechanism by which identity may be constructed in interaction is through stance, or the ‘taking up [of] a position with respect to the form or content of one's utterance’ (Jaffe Reference Jaffe and Jaffe2009:3). Analytically, this enables a focus on speaker's evaluation of and orientation to the claims or positions taken by others. Though stancetaking ‘cannot be fully interpreted without reference to its larger dialogic and sequential context’ (Du Bois Reference Du Bois and Englebretson2007:142), it may be argued that stances typically fall into three categories: they are evaluative (whereby the stancetaker interprets an idea or object either positively or negatively), epistemic (whereby stances are based on what a stancetaker does or does not know), and affective (whereby stances are based on emotion). Indeed, affect may be more broadly understood as the ‘circulation’ of emotions through objects and individuals (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2014), meaning that emotions are themselves shaped during interaction (Milani & Richardson Reference Milani and Richardson2020). That is to say, feelings and emotions—like identities—are discursively and dialogically constructed; they are produced through language as a form of ‘affective practice’ (Wetherell Reference Wetherell2012) rather than being pre-existing and unconscious. In the analysis that follows, affective stancetaking—what Ochs (Reference Ochs, Gumperz and Levinson1996:410) defines as the articulation of ‘a mood, attitude, feeling and disposition, as well as degrees of emotional intensity vis-à-vis some focus of concern’—is a key part of the young people's identity construction.

By focusing on affect as it emerges through dialogic stancetaking, we can gain important insight into the value systems shaping identity constructions. For example, in Glapka's (Reference Galupo2019) analysis of black South African women's talk about their hair, stancetaking is shown to constitute the women ‘as embodied and emoting subjects amid the hegemonic discourses of body and beauty’ (2019:604). Glapka shows how her participants’ affective stancetaking sometimes aligns with westernised aesthetics framing them, as black women, as inferior, while other affective stances reject these norms. In this way, the women's affective stancetaking in relation to their hair both reinforces and disrupts ‘power relations inherent in the local identity and body politics’ (Glapka Reference Glapka2019:615).

Like Zimman's (Reference Zimman, Zimman, Davis and Raclaw2014) participants (discussed above) who recontextualise gendered bodily terms, the women in Glapka's study challenge and subvert hegemonic structures and ideals through their stancetaking and, in this sense, are agentive in their identity construction. Defined by Ahearn (Reference Ahearn2001:112) as ‘the socioculturally mediated capacity to act’, an analytic focus on agency is particularly important when considering the language of marginalised groups. As Parish & Hall (Reference Parish, Hall and Stanlaw2020) argue, speakers who might otherwise lack material or cultural power can, in certain interactional contexts, nonetheless be active in controlling their own positionality. Indeed, the analysis below shows that a group of young trans people's stancetaking has the ultimate effect of subverting cisnormativity. As they resist and reject the interpretations of others, they affirm their own subjectivities and dialogically construct agentive identities for themselves.

THE STUDY

The data in this study occurred during a focus group held with members of a trans youth support group in Lakebury,Footnote 1 a working-class town in northern England. I carried out ethnography with the support group between January and April 2015, during which time I met twelve young people: the youngest was fifteen and the oldest was twenty. Some of them already knew me because they were also members of a lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans (LGBT) youth group where I had conducted fieldwork previously (Jones Reference Jones2016, Reference Jones2018, Reference Jones2020a). The youth worker who ran both groups invited me to come and meet the young people, at which point I explained my research aims. They agreed to me returning and five members later volunteered to take part in a one-hour focus group.

Unlike the LGBT youth group, which was a social space where young people only sought support if they needed it, the trans support group was focused on advice and safeguarding. As such, the young people could bring parents or guardians with them. Not everyone did this, as not all parents were accepting and not all young people were openly trans outside of the group. It was clear, though, that the support group was immensely valuable for all members; parents were able to share their experiences with one another, with a view to better supporting their children, and the young people benefitted from a context in which they were not a minority. The town was known for being conservative and traditional, and the young people had all experienced discrimination and abuse due to their gender identity. The safe and collaborative space of the support group was therefore an opportunity to share coping strategies and get practical help from professionals.

Despite the clear need for the support group, however, due to extraordinarily stretched resources it ran only once a month, mid-week, for two hours. The group was staffed on a voluntary (unpaid) basis by two cisgender youth workers who were employed to run the LGBT youth group, and who recognised the need for a trans-specific space. The local council could not finance the youth workers’ time but did allow them free use of a local authority building for meetings. I was conscious of the limited time the young people had together and recognised that they may feel unable to speak freely in my presence. For that reason, I limited the duration of my fieldwork and tended not to stay for the full two hours; this was ethically important but did reduce the scope of my ethnography. Despite being an outsider, I gained useful insight into the young people's shared experiences and subsequent sense of self by observing their interactions together, both during informal conversations with one another and during whole-group meetings which included their parents and youth workers.

Of course, it is not unusual to be something of an outsider in the context of linguistic ethnography, which means that our analyses are always partial. We must therefore reflect on our own positionality when considering the conclusions we draw (Aiello & Nero Reference Aiello and Nero2019). In this case, I had never lived in Lakebury and was a middle-class woman in my thirties. The way my participants talked to me reflected this; they checked if I had heard of particular celebrities before talking about them and used expressions like nowadays when talking about their own experiences. I held relative insider status thanks to being lesbian, thus a fellow member of an imagined ‘LGBT community’, but the young people knew I was cisgender; they explained their lives to me in ways that revealed their assumptions about my ignorance of the milestones they described (such as beginning to take hormones or adopting new pronouns). And of course, every aspect of the study itself—from its design to my analysis—is informed by my own positionality, including my inexperience of trans subjectivity (cf. Galupo Reference Galupo2017) and the cisgender privilege that comes with never questioning or having to justify my gender identity (Serano Reference Serano2007).

Through my participant observation, however, I was able to gain crucial insight into the young people's everyday experiences, from the hurdles they faced to the joy they felt when they received acceptance from family and friends. I also gained an understanding of the dynamics of the group—a key aim of linguistic ethnography—and came to see them as collaboratively creating an empowered space in which they reframed the ignorance of others, prioritising and validating their own understanding of their trans subjectivities (see Jones Reference Jones2020b). My interpretation of the data is fundamentally informed by these observations, but I also endeavour to embed a ‘trans analytic lens’ (Zimman Reference Zimman, Hall and Barrett2020) into my analysis by drawing wherever possible on insights from trans scholars. In doing so, I aim to not only better contextualise my data and illustrate the salience of the experiences described by my participants, but also to acknowledge the limitations of my own understanding. I therefore follow Zimman (Reference Zimman2021:427), who argues that trans linguistics ‘is not exclusively for trans thinkers, but for anyone who aims to fully divest from transphobic worldviews while meeting the moral obligation to materially invest in the wellbeing of trans humans, including supporting and amplifying the voices of trans students and scholars.’

The data presented below comes from a focus group that I ran towards the end of my fieldwork. Three young trans men (Kyle, 19; Dan, 17; Zack, 15) and two young trans women (Ashleigh 20; Bella, 19) took part. All were white except Bella, who had one black parent and one white parent. I collected informed consent from the young people and, in Zack's case because he was under sixteen, from his parents (who also attended the support group) as well. I printed out a short list of questions (approved by the lead youth worker in advance) for the young people to read out and answer; this minimised my involvement during the session despite my presence there. The questions, such as ‘what words have you heard used to talk about trans people?’, did not require the young people to disclose sensitive information. I explained that they did not have to share anything personal, but that, if they chose to do so, they could be assured that the recording would remain anonymous. In fact, the interaction flowed freely, and the young people typically strayed quite far from an original question, chatting spontaneously and leading the direction of the conversation. Ashleigh was very anxious about taking part but asked to sit in on the focus group, and only made a few small contributions. She does not appear in the data presented below, and Bella speaks only once; the analysis which follows therefore largely reflects a transmasculine perspective.

ANALYSIS

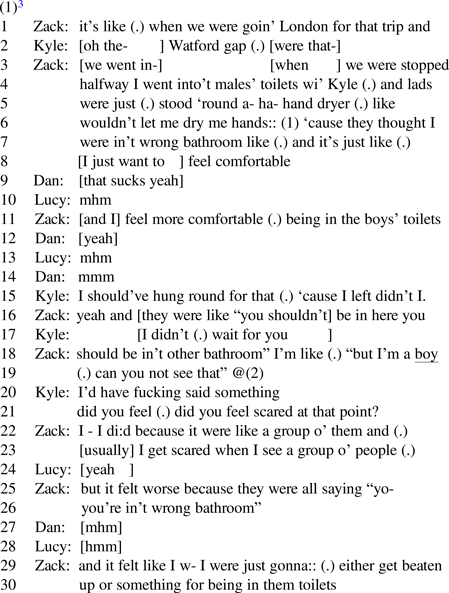

Around fifteen minutes into the focus group, I asked the young people if they thought that modern society was mostly accepting of trans people. By way of arguing that it is not, Bella introduced the topic of the ‘bathroom bill’ controversy, taking place at the time in the US, whereby possible legislation would force trans people to use public facilities correlating with the sex they were assigned at birth. This led to Zack sharing the story below, in which he felt scared when strangers questioned his use of the public toilets intended for men at motorway servicesFootnote 2 during a trip with the LGBT youth group.

Zack frames this event in terms of his agency being impinged upon by other young men in the bathroom who prevented him from accessing the hand dryer. This elicits a supportive evaluative stance from Dan (“that sucks yeah”) in line 9. Zack describes his aggressors as “lads” (line 4), a colloquial term in British English often used to describe groups of young men who engage in hyper-masculine behaviour. The use of this term, rather than the more generic ‘men’ or ‘boys’, emphasises the potential danger of the situation Zack found himself in—especially since, as Kyle states in line 15, he had been left alone. Notably, Zack does not premodify “lads” with a determiner, such as ‘some’; this serves to position the men in generic terms, foregrounding the frequency with which young men like this might be encountered.

Zack explains in line 5 that they were “just stood round a hand dryer”, the adverb “just” indicating a lack of purpose and suggesting they were not actively using the equipment themselves. Zack does not elaborate on the specific way in which they “like wouldn't let me dry me hands” (line 6), but the discourse marker “like” indicates an approximate link between the lads’ physical presence and the fact they “wouldn't let” Zack use it. Zack therefore sets a scene whereby they were deliberately blocking his path to the dryer. The verb “let” in the active sentence positions Zack as passive, so he frames himself as powerless in this situation. Furthermore, in line 15, Zack introduces constructed dialogue through the quotative “like”: “you shouldn't be in here you should be in't other bathroom” (lines 16, 18). Zack's repetition of the modal verb “should” attributes authority to the lads, portraying them as believing they hold the power to dictate where he is allowed to go. The contrasting use of the prepositional phrase “in here” with the noun phrase “other bathroom” alludes to the binary way in which public facilities are divided and positions the space they were all inhabiting at the time (“in here”, already defined as the “males’ toilets” in line 4) as exclusive to them. Combined, this dialogue positions the lads as authoritative, policing the space and framing Zack's presence there as illegitimate due to them not seeing him as ‘male’.

Zack explains the reason for the lads’ claim in lines 6–7, “they thought I were in't wrong bathroom”, and again in line 26, where they are quoted as saying “you're in't wrong bathroom”. The phrase “wrong bathroom” logically implies that there is a correct bathroom for Zack to use; this correlates with his statement in line 11 that “I feel more comfortable being in the boys’ toilets”. Zack uses indirectness to explain his situation; rather than state explicitly that the lads had read him as female or recognised that he was trans, he implies that they believed his place was in the female bathroom. This allows him to save face, telling this story without engaging directly with its implication that he did not pass as male. Furthermore, by not making explicit the link between the lads’ belief that he was in the wrong bathroom and his own trans status, Zack positions his aggressors as wrong (“they thought”, line 6), with the verb “thought” indicating an assumption in this context.

This is reinforced in line 18, when he quotes himself as saying “but I'm a boy can you not see that”. This is likely internal dialogue rather than actual speech, given he subsequently says he was scared, but nonetheless the constructed dialogue frames the lads as effectively blind to Zack's gender. The conjunction “but” allows him to refute their assumption that he is not a boy by implying that this fact should be obvious, thus he takes an explicit stance against their claim. Indeed, his question ‘can you not see that’ mocks them for missing such a clear fact. He therefore both frames the lads’ statement as illogical by revealing its inaccuracy and reinforces his own gender identity, stressing his essential identity as a boy. His laughter closes his turn, reinforcing that this was an implausible and laughable conclusion for the lads to have drawn. In constructing the story in this way, Zack reclaims his agency by positioning the lads as at fault for not understanding his gender identity, rather than himself for not adhering to their cisnormative expectations of what someone using those facilities should look like.

It is clear, however, that Zack's marginalised status as a trans boy whose body was read as female dictated the encounter he describes, and his affective stancetaking reveals the impact it had on him. In lines 8 and 11, he states, “I just want to feel comfortable and I feel more comfortable being in the boys’ toilets”. He rationalises this feeling through the adverb “just”, minimising any impact this could have on others and naturalising his preference for the men's bathroom. In doing so, Zack disputes that his status as a trans boy should prevent him from using the bathroom where he experiences positive affect. By repeating the phrase “feel comfortable” and adding to this a gradable quality (“more”), Zack indicates that he feels uncomfortable in ‘women's’ toilets. The emphasis here is on his own individual experience, articulated through the repeated use of the first-person singular pronoun “I”; combined with “just”, Zack evaluates this as a highly personal and, importantly, a reasonable request. This contrasts with constructed dialogue of the lads, who Zack positions as offended by his presence in the men's bathroom. In this sense, Zack frames the vulnerability he experienced in the bathroom as disproportionate and rejects the notion that only those with bodies normatively categorised as male should use ‘men's’ toilets. Though he positions himself as powerless at the time, in his constructed dialogue he reworks these normative expectations and thus gains agency. Furthermore, through his affective stancetaking, he subverts cisnormative ideology around his embodiment.

In response to my question of whether he felt scared (line 21), Zack responds with an affirmative (“I did”) in line 22, qualifying this through the conjunction “because” and emphasising that this was a group. This allows him to save face as he stresses that he was outnumbered, implying he would not have been scared if it had been just one lad. This may indicate some concern to adhere to hegemonic ideals of masculine bravery, though I did not witness overtly ‘macho’ performance as part of the identity construction taking place in this group. Indeed, Zack goes on to say that “usually I get scared when I see a group o’ people” (line 23). He includes no prepositional phrase to postmodify “people” and no adjective to premodify it, suggesting that he would feel fear in most contexts (indicated by the adverb “usually”) when any group was present. His reported affective stance here is unmitigated, foregrounding his everyday vulnerability outside of the support group. Zack implies that the sense of danger he felt in this specific experience was due to his trans status, stating that “it felt worse because they were all saying ‘you're in't wrong bathroom’” (line 26), an utterance to which Dan and I provide supportive minimal responses. This leads Zack to explain why this moment felt worse, stating that “it felt like I were just gonna either get beaten up or something for being in them toilets” (lines 29–30). The use of the past tense “felt” signals his affective response to the situation at the time, emphasising his fear of violence.

Though the conversational floor in this extract is taken up largely by Zack, when we consider the uptake from others in the interaction, the dialogic nature of embodiment is revealed. Indeed, as demonstrated by Calder's (Reference Calder2019) analysis of drag queen discourse, a measure of a speaker's success in communicating their desired identity in a given interactional moment is how their interlocutors respond to it; identity moves interpreted as less authentic are likely to receive less speaker uptake. In this case, both Dan and Kyle are encouraging in their responses to Zack; Dan provides a supportive stance in line 9 through the declarative “that sucks”, empathising with his friend and thus legitimising Zack's feeling of intimidation. Similarly, Kyle articulates regret in lines 15 and 17: “I should've hung around for that ‘cause I left didn't I. I didn't wait for you”, again legitimising Zack's affective stance that he felt uncomfortable. Kyle was older than Zack and had been transitioning for a number of years; he passed as male and therefore had more perceived legitimacy to be in the men's toilets, and he expresses regret in not capitalising on that to offer Zack some protection. The lack of mitigation in his statement and the use of the modal verb “should” indicates this, and he expresses anger on Zack's behalf through the expletive “fucking” in line 20. The affect produced by Kyle here, in the form of both guilt and anger, reveals much about the relationship between public toilets and many trans people. Segregated toilets shape our understanding of gender and reinforce cisnormative, binary ideologies from childhood (Slater, Jones, & Procter Reference Slater, Jones and Procter2018), and they remain a place of considerable danger for many trans people as they get older (Patel Reference Patel2017; Lester Reference Lester2017). Both Dan and Kyle empathise with Zack in his retelling here, providing supportive affective responses which serve to problematise the lads’ interpretation of him as not male. In doing so, they implicitly reframe and legitimise Zack's embodiment as masculine within the context of their interaction.

Approximately ten minutes later, I asked the young people about words they had heard used to describe trans people, resulting in a conversation about times they had been told they were wearing “girls’ clothes’ or ‘boys’ clothes”. In response, Dan shared the following anecdote.

Dan begins his story in the past and, more specifically, during his childhood (“I used to… when I was little”, line 1), quickly moving to “the point where I started puberty” (line 3). Dan mentions puberty and his resistant stance towards wearing a bra (“I wasn't gonna wear a bra”, lines 3–4), implying that breast development occurred but focusing on the contrast between the “masculine clothes” that “obviously I always wore” (line 2) and the apparent need to wear a bra. The adverbs “obviously” and “always” serve to position Dan's behaviour, even as a child, as rooted in his masculine identity; he presents it as logical that he would wear non-feminine clothes, authenticating his maleness by invoking binary ideology. Dan's use of the past progressive (“wasn't gonna”) frames this as a historic issue but one which continued for some time, reflecting the prolonged nature of puberty and a continued resistance towards wearing a bra. Dan's emphasis of the word “bra” in line 4 with a laughing quality enables his stancetaking, rejecting the notion that he would wear one.

Zack's turn in lines 5–6 serves to explicitly gender this item of clothing: “a bra, a magical thing that women wear”. The vague noun “thing” has the effect of positioning bras as unfamiliar, while the adjective “magical” frames them as other-worldly. Furthermore, the phrase “that women wear” very firmly distances bras from Zack and Dan by placing them as for women rather than men (and therefore as strange items with which men, like them, are unaccustomed). Although this is intended to be humorous (shown by Zack's laughter), it plays a key role in differentiating between women, who develop breasts and wear bras, and men, who do not. As with Kyle and Dan's supportive stancetaking in extract (1), Zack's turn here supports Dan's construction of his embodiment as masculine by drawing this distinction with bras.

Dan's uptake through brief laughter supports Zack's characterisation before he returns to his narrative and his focus on clothes in more general terms. Remaining in the past tense, Dan returns to “the skate park” (line 1)—a space often dominated by young men—where his “t-shirt would push against” him (lines 8–9) as he skated down ramps at speed. What is implied here, but not stated explicitly, is that Dan was developing breast tissue which could be seen through his clothes. By giving grammatical agency to his t-shirt rather than his body, Dan distances himself from the culturally female signifier of breasts.

Dan goes on to produce constructed dialogue in which his marginalisation as a gender non-conforming child was realised verbally: “just wear a bra it's time for you to wear a bra” (lines 11–12). Though Dan does not attribute this to any specific actors, he indicates that he was told this often (“a lot”, line 11). As Dan positions this dialogue as occurring within the skate park, he implies that this policing of his body came from his peers. He quotes them as framing it as a natural progression to begin wearing a bra (“it's time”) which, in itself, should be a simple act (“just wear a bra”). Dan's resistance is evident in lines 12–13: “I'm just like I'm not wearing a bra.”. Again, it is unclear whether Dan intends for this to be perceived as actual or internal dialogue, but the falling intonation which concludes this statement and the lack of hedging around it allows him to position himself as firm and clear, despite efforts to regulate his behaviour. In this moment, then, Dan constructs an agentive identity position for himself, despite describing his marginalisation. This mirrors Cashman's (Reference Cashman2018) analysis of queer Latinx speakers’ coming out stories; she shows that her participants ultimately construct an agentive identity, despite their narratives often describing them being ostracised.

Through the conjunction “but” and the adverb “then” (line 13), Dan frames his refusal to wear feminine clothing (“dress like that”, line 16) as leading to questions, with the constructed dialogue “hang on, is it a boy or a girl” (line 14). Characterising “those people” (an undefined and presumably therefore ubiquitous group) as saying “hang on” presents them as confused. This both reinforces Dan's self-characterisation as gender non-conforming in terms of his clothing and allows him to foreground the fact that he was quizzed about his gender (which, notably, his constructed dialogue frames as binary). In lines 17–18, Dan constructs an affective stance in relation to these questions; “I don't want them to ask me what gender I am I just want them to know that I'm a guy”. Here, Dan frames his clothing choices as raising questions about his gender, and his body as preventing people from “just” understanding it, with “just” indicating the natural and simple process that he desires (shown through repetition of the affect marker “want”). Though Dan frames his identity as “a guy” as under question, his direct stancetaking in claiming this category for himself (through the declarative “I'm a guy”) asserts his embodiment as male and subverts cisnormative ideology to the contrary.

At this point, Zack makes a second contribution to the discussion and moves the narrative into the present tense, engaging in linguistic recontextualisation of the body part in question—breasts—to reframe them as part of a masculine (rather than feminine) body: “you just got these moobs” (line 20). ‘Moobs’ is a contemporary neologism formed of a blend between ‘man’ and ‘boobs’ (a colloquial British word for breasts). It is typically used to refer to cisgender men with excess fat on their chest, leading to some visual similarity with breasts. In this moment, then, Zack uses a label for a masculine body part to refer to the breasts Dan was developing, effectively erasing the cisnormative link they have with womanhood. As Zimman argues, the ‘tactical claiming of “male” terminology in reference to body parts often seen as female … works to construct trans men as male-bodied despite the powerful discourses that insist otherwise’ (Reference Zimman, Zimman, Davis and Raclaw2014:29). This is particularly effective here because of the mainstream cultural recognition that ‘moobs’ are a male version of ‘boobs’.

This attribution is reinforced by Dan in line 21 as he repeats the word “moobs” and claims ownership of them (“I've just got moobs yeah”), using the present tense for the first time in this extract. It is telling that throughout his narrative, Dan did not use the word ‘breasts’ (or a colloquial equivalent) to describe this part of his body, labelling them only once Zack provides an appropriate term. This reveals his discursive distancing of himself from this body part. Similarly, in Corwin's (Reference Corwin2017) study, one genderqueer participant used the term ‘puffy nipples’ to ‘ascribe more masculine or ambiguous meaning to what otherwise would be called their breasts’ (Corwin Reference Corwin2017:263). It is evident, then, that symbols of femininity may cause particular problems for those not identifying as female, but that linguistic creativity is one way to negotiate this in an agentive way. As in King's (Reference King2016) analysis, Zack and Dan work together to bring into being that which standard language is insufficient to describe, and in this sense their embodiment is dialogically produced. Furthermore, through this process they collaboratively index a fundamentally masculine identity.

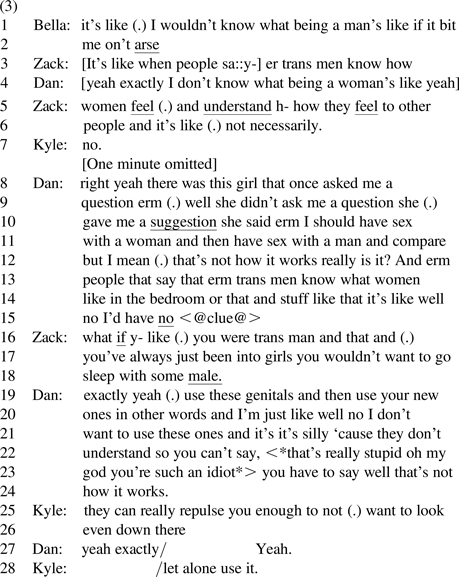

Towards the end of the focus group, Bella began talking about a boy she had a crush on. This led her to describe an article she had read online with the topic ‘Why straight men date trans women’. She reported that it was an interesting article, except that one of the reasons given was that “transgender women can understand better what being a man's like”. She said that she was offended by the suggestion that trans women have this understanding.

The young people work collaboratively here to reject the notion that trans people understand the gender identity which is normatively attached to the sex they were assigned at birth. The extract begins with Bella's epistemic stance: “I wouldn't know what being a man's like if it bit me on't arse” (lines 1–2). This conditional sentence is structured with the if-clause at its end, allowing the declarative “I wouldn't know” to be foregrounded: this emphasises Bella's negative stance-taking. The if-clause also reflects the formulaic construction of the English idiom ‘you wouldn't know X if it bit you on the nose’, meaning the subject has no comprehension of the object. Employing this structure here allows Bella to emphasise the impossibility of her having experience of male identity.

In lines 3–7, Dan, Zack, and Kyle also respond negatively to the original proposition by framing it as problematic. Dan takes an epistemic stance in alignment with Bella (“yeah exactly”) and then mirrors her declarative and applies it to himself as a trans man: “I don't know what being a woman's like” (line 4). His repetition of “yeah” affirms his stance-taking. Zack also likens Bella's story to trans men, saying “it's like when people say trans men know how women feel and understand how they feel” (lines 3, 5). He constructs hypothetical speech here, but the use of “people” indicates a generic mass, suggesting this is a frequent claim. Dan and Zack's combined responses generalise Bella's story to all trans people, allowing them (as trans men) to engage in this authentication work themselves. Zack's extension of knowing (as Bella and Dan put it) to feeling also emphasises the emotional experience that would be needed to have knowledge of ‘what it's like’ to be a woman or man. They therefore emphasise the difference between gender identity (defined by experience) and sex characteristics. Whereas Bella and Dan take firm epistemic stances against the original proposition, Zack's evaluative stance is weaker (“not necessarily”, line 6) but still negative. Kyle responds with a straightforwardly negative response in support of Zack: “no” (line 7).

From line 8, Dan constructs dialogue whereby “this girl” suggested he should have sex with a boy while he has a vagina, and then with a girl once he has a penis. The determiner “this” specifies a particular girl who made this suggestion, while also distancing Dan from her; it is telling that he does not describe her as a friend. His self-correction from “asked me a question” to “gave me a suggestion” (lines 9–10) indicates his irritation; whilst a question would signify that she was seeking knowledge, his reframing of this as a suggestion (which he emphasises to show its importance to the story) reverses the balance of power and thus renders him subordinate. Though he does not specify that she is cisgender, it can be deduced from his constructed dialogue in response (“that's not how it works”, line 12) that she does not have personal experience of being trans. The inclusion of the adverb “really” and the tag question “is it” indicates a patronising tone from Dan, further distancing himself from her.

Dan then links back to the previous topic, referring again to a generic mass of ‘people’ who believe trans men understand what it is like to be a woman. In lines 13–14, he focuses specifically on sexual practice by constructing hypothetical dialogue: “people say that erm trans men know what women like in the bedroom or that and stuff like that it's like well no I'd have no clue”. The laughing quality as he articulates “clue” positions it as humorous to suggest this, though it may also indicate some embarrassment; the dysfluency features in Dan's speech (“or that and stuff like that”) appear to function as fillers and suggest an awkwardness in discussing sex in this context. This analysis is strengthened by the euphemistic construction “in the bedroom”. Nonetheless, in this moment Dan reinforces his earlier stance-taking against the proposition that trans people have an understanding of another gender identity (“I'd have no clue”, line 15). Through the epistemic stance that he would have “no clue”, he characterises himself as having zero comprehension of being female, strongly asserting his identity as male. Dan's story exemplifies the sexual objectification many trans people experience through being asked intrusive questions about their genitalia (Nadal, Davidoff, David, & Wong Reference Nadal, Davidoff, Davis and Wong2014), a phenomenon which Lester (Reference Lester2017) argues reflects a preoccupation with the medical aspects of (some people's) transition. Again, then, the young people's marginalised, ‘other’ status is reinforced here.

The uptake to Dan's anecdote from line 16 returns the focus of the interaction to the specific suggestion that Dan have sex with a woman and a man. Zack responds to this in lines 16–18 by saying, “what if you were trans man… and you've always just been into girls you wouldn't want to go sleep with some male”. This conditional sentence uses the generic second person “you” to position a hypothetical trans man, who is heterosexual, being expected to have sex with a man. The hypothetical nature of this construction is apparent from the rhetorical question format presented at the start of the sentence: “what if”. This allows Zack to avoid framing the “you” in his utterance as Dan, specifically, as does his use of the present perfect tense (“you've always”) to indicate that this is a theoretical imagining. Through this construction, Zack mitigates any face threat by not making an assumption about Dan's sexuality: the young people were particularly careful to avoid assumptions about anyone's sexuality and/or gender. Zack highlights the incongruence of expecting someone who had “always just been into girls” (with “just” emphasising an exclusively heterosexual identity) to then “sleep with some male”. “Some” as a non-specific determiner allows Zack to present this as an unfamiliar and undesirable option while also constructing an opposition between “male” and “girls”. This juxtaposition is grammatically asymmetrical, with “male” being an adjective functioning as a noun, and “girls” being a simple noun. This increases the positioning of “some male” as an unlikely object choice for the hypothetical trans man who has exclusively and continuously (shown by “always”) been attracted to girls, specifically.

Zack's turn, then, problematises the cisnormative assumption that trans people's sexuality correlates to their genitalia, and therefore shifts before and following surgery. Dan shows agreement with Zack (“exactly yeah”) and reinforces his point in line 19, as he summarises the suggestion from “this girl”: “use these genitals and then use your new ones”. Through the repetition of the verb “use”, he characterises genitals as tools or inanimate objects, interrupting the dominant cultural view of genitalia as gendered and removing them from the context of sexual desire. In this way, Dan and Zack again construct their embodiment as trans men; similar to Zimman's (Reference Zimman, Zimman, Davis and Raclaw2014) findings, these young men disrupt the cisnormative link between particular types of genitalia and male identity. Dan's affective stance in the constructed internal dialogue (“I'm just like well no I don't want to use these ones”, lines 20–21) allows him to put into stark contrast the girl's superficial understanding of his relationship with his body and the fact that genitalia are a common source of gender dysphoria (a point reinforced by Kyle in line 25 through the verb “repulse”).

Finally, Dan characterises the girl as “silly” before referring more generally to people like her (using the collective pronoun “they”) who “don't understand” (lines 21–22). This leads him to express, through constructed hypothetical dialogue, a tension between how he would like to respond and how he actually does respond in such instances: “you can't say that's really stupid oh my god you're such an idiot you have to say well that's not how it works” (lines 22–24). While the emphasis (through “really” and “such”) on the ignorance of these people (indicated by “stupid” and “idiot”) is clear, Dan positions trans people (shown through the generic “you”) as comparatively constrained and therefore unable to express themselves in these terms: “you have to say” (line 23). The modal “have to” indicates a requirement to be patient and polite (also indicated through the discourse marker “well”), despite being subjected to such enormously intrusive suggestions. This affective stancetaking reveals, yet again, the vulnerable status of many trans people, as challenging cisnormative discourse can put them at risk (Konnelly Reference Konnelly2021). Certainly, in this case, Dan positions himself as lacking agency when it comes to correcting people, despite his frustration at being subjected to ignorant questions about his own body. Nonetheless, together, the group members problematise this constructed dialogue and thus authenticate their lived experience as trans people.

DISCUSSION

In each of the three moments above, the young people's constructed dialogue frames other people as assuming they have the right to inscribe meaning and function on their bodies, thus reproducing cisnormative power relations. They are told which toilet to use, clothes to wear, and people to sleep with. This constructed dialogue reflects what Serano (Reference Serano2007) calls gender entitlement, whereby some cisgender people feel they have the right to both question and correct trans people's gender identities. This symbolic act of violence, of course, undermines trans people's very existence. Whether their stories invoke direct aggression or ignorant questioning, the young people above are marginalised, as their interlocutors characterise their bodies in ways which conflict with their sense of self.

In telling these stories and positioning themselves as marginalised within them, however, the young people are able to actively reject the characterisations imposed upon them and to subvert the problematic assumptions made about their own bodies. In turn, they disrupt and expose hegemonic expectations through their talk, a response which may be viewed as ‘a hopeful crack in a seemingly solidified oppressive system’, given that such resistance ultimately breaks down cisnormativity (Nordmarken Reference Nordmarken2019:43). In extract (1), and with the support of his friends, Zack reclaims the agency lost to the men who prevented him from using the male bathroom by ultimately blaming them for their ignorance and foregrounding the essential fact of his maleness. In extract (2), Dan and Zack work together to linguistically recontextualise breasts as ‘moobs’, allowing them to reject the argument that they should wear a bra. In extract (3), although Dan articulates a lack of agency in being subjected to people's invalid assumptions about his sexuality, the young people gain agency in their collaborative construction of those people as ignorant. This positioning and recontextualisation is fundamentally dialogic, with uptake from the young people to one another's stancetaking revealing the co-construction of the group's identity and thus their agency in this interactional context.

Indeed, despite each story being initially about one individual (the storyteller) who is subjected to misgendering or marginalisation, the group respond collectively in each case; they empathise and express solidarity, take supportive stances, and demonstrate through their discourse that these moments impact them all. They collectively reject the link between cisnormative ‘masculine’ bodies and the use of male public toilets, and they reframe body parts labelled ‘feminine’ as masculine or inanimate. In doing so, they work together to deconstruct and reconstruct their own bodies, demonstrating Bucholtz & Hall's (Reference Bucholtz, Hall and Coupland2016) claim that the body is produced in interaction. This analysis shows how dialogic embodiment may be achieved through speakers’ collective recontextualisation of their bodies, with the production of affect and storytelling (including constructed dialogue) being key tools in the mutual construction of identity. It therefore adds to existing evidence that the body can be, quite literally, spoken into being.

This study offers a contribution to trans linguistics in its effort to disrupt ‘ways of thinking that are rooted in cissexism’ (Zimman Reference Zimman2021:425). In foregrounding the agentive nature of the identity construction in this data, the young people are shown to be empowered rather than passive. I have argued that the dialogic embodiment evident in their identity construction is indicative of the innovative strategies they employ to resist cisnormativity; these strategies reflect what Konnelly (Reference Konnelly2021:78) describes as linguistic ‘forms of trans resistance that are enacted in contexts where trans narratives may be shaped by hegemonic expectations’. Yet the empowered identity constructions illustrated here do also highlight the everyday transphobia endured by the young people. The impact on their emotional wellbeing of being forced to repeatedly navigate a world in which they are misgendered, ostracised, and endangered cannot be underestimated. It was clear even from my short period of fieldwork with the support group that having this space, where they could share their experiences with those who understand on a personal level, was absolutely central to their wellbeing. The trauma of having their gender questioned whenever they were outside of this safe space was palpable. This makes it all the more distressing to know that, shortly after my fieldwork ended, the support group was disbanded due to those staffing it being made redundant. The findings of this article thus provide clear evidence of the need for the continued support by local and national government of specialist services for trans youth.

APPENDIX: TRANSCRIPTION CONVENTIONS

The method of transcription used here is adapted from Jefferson (Reference Jefferson and Lerner2004).

- -

self-interruption or false start

- (.)

pause of less than one second

- (2)

timed pause

- .

end of intonation unit; falling intonation

- ?

end of intonation unit; rising intonation

- <italics>

transcriber comment

- :

lengthening of sound

- @(2)

laughter with duration

- <@word@>

laughing quality

- underline

emphatic stress or increased amplitude

- [ ]

overlapping speech

- <*word*>

rapid speech

- /

latching speech