INTRODUCTION

This article presents a brief description and analysis of some of the categories of linguistic features found in contemporary Manx, by which present-day usage may diverge from the norms of the traditional language. Manx today is a revived Celtic language with no traditional native speakers. According to Zuckermann (Reference Zuckermann2009, Reference Zuckermann2020) and Zuckerman & Walsh (Reference Zuckermann and Walsh2011), languages revived initially as an L2, such as Israeli Hebrew, inevitably have a permanent ‘hybrid’ character, blending the substrate of the L1 of the ‘founder generation’ of revivalists with forms and patterns incompletely assimilated from the target language—even if they then become a fully vernacularized mother tongue of subsequent generations. We may compare the observation of Hinton & Ahlers (Reference Hinton and Ahlers1999:61) with regard to indigenous Californian languages now moribund as L1s:

In the situation of language revitalization in small speech communities, the new learners will one day be the sole bearers of the language, and therefore all of the patterns of simplification, interference, and incomplete learning that remain extant in the learners’ speech will be a permanent part of that language. (Hinton & Ahlers Reference Hinton and Ahlers1999:61)

Such blending of the features of the target language with new patterns introduced through the process of L2 language revival can clearly be seen in the case of Revived Manx. The present case study also illustrates how the particular historically contingent idiosyncrasies of a given pair of linguistic systems and traditions can have a significant impact—for example, the complexities of the Manx orthography and how these are interpreted in relation to English. Language ideology is also shown to be an important variable, although a significant degree of commonality between language revitalization scenarios can be observed, as discussed below.

Zuckermann's (Reference Zuckermann2009, Reference Zuckermann2020) work stresses the centrality of Hebrew (or ‘Israeli’) as the natural focus and prototype for his proposed field and paradigm of ‘revival linguistics’ or ‘revivalistics’, given that it is undoubtedly the most successful and best documented revival in terms of achieving large numbers of speakers and full sociolinguistic vitality as a community and subsequently state language (Blanc Reference Blanc1957; Nahir Reference Nahir1998). It may be argued, however, that revived minority languages such as Manx are in fact more typical, and in some ways more instructive, cases of language revival. Unlike Hebrew, but like most, perhaps all, other revived languages, Manx remains largely an L2, moulded by conscious learning by relatively small numbers of adults in each generation, rather than being subject to the usual unconscious processes of language change during intergenerational transmission of natively spoken languages. Even in the rare cases of L1 acquisition, English is likely to remain, or become, the speaker's cognitively and socially dominant language. Similarly, language immersion pupils, whose degree of future continued participation in the language movement is uncertain and subject to great variation between individuals (Sallabank Reference Sallabank2013:219; Wilson Reference Wilson2009:24–25), are by no means guaranteed to have a decisive role in developing the linguistic norms of the future, which remain contested. In these respects the Manx situation is perhaps a more typical example of what to expect when a second language is maintained over the long term in small networks of enthusiasts and activists who are mostly adult learners, rather than the process of rapid and complete language shift from Yiddish (and other languages) to Revived Hebrew, followed by ‘normal’ L1 language transmission in subsequent generations (and assimilation to this L1 norm of subsequent generations of immigrants), which characterizes the Israeli experience.

Manx: Historical background

Manx is the autochthonous heritage language of the Isle of Man, a self-governing British crown dependency in the Irish Sea with a population of c. 83,000. It is closely related to Irish and Scottish Gaelic, although mutual intelligibility is low without prior familiarization or study (Ó hIfearnáin Reference Ó hIfearnáin2015a:114–15). In its revived variety (or varieties), Manx is spoken by several hundred people,Footnote 1 predominantly as a second language acquired either in adolescence or adulthood, or since 2001 through immersion primary school education (Clague Reference Clague2009). Some cases of family intergenerational transmission have been reported (Sallabank Reference Sallabank2013:146; Ó hIfearnáin Reference Ó hIfearnáin2015b:47), but remain rare. Manx is today a network language used predominantly at formal and informal language-focused events, in certain friendship and acquaintance circles, a handful of households and workplaces, and in online digital environments. The language in its historical vernacular form was already moribund by the mid-nineteenth century (Broderick Reference Broderick1999; Miller Reference Miller2007). Ned Maddrell (b. 1878), generally reported to be the last native speaker (or semi-speaker; Lewin Reference Lewin2017a:191–93), died in 1974, and language revitalization efforts in the mid-twentieth century centred on documenting and emulating the Manx of Maddrell and a number of other elderly speakers, as well as the study of written texts, most notably the eighteenth-century Bible translation. A significant degree of continuity between the traditional and revived varieties is thus generally claimed by those involved in the language movement (Sallabank Reference Sallabank and Spolsky2012:101; Ó hIfearnáin Reference Ó hIfearnáin2015b:48).

There is now a considerable literature on Manx language policy and planning, predominantly from historical, sociological, linguistic anthropological, and ethnographic perspectives (e.g. Broderick Reference Broderick1999:173–87, Reference Broderick2013b; Gawne Reference Gawne, McCoy and Scott2000, Reference Gawne, Davey and Finlayson2002, Reference Gawne, Scott and Bhaoill2003; Ó hIfearnáin Reference Ó hIfearnáin, Eloy and Ó hIfearnáin2007, Reference Ó hIfearnáin2015a,Reference Ó hIfearnáinb; Wilson Reference Wilson and Novacek2008, Reference Wilson2009, Reference Wilson2011; Ager Reference Ager2009; Clague Reference Clague2009; George & Broderick Reference George, Broderick, Ball and Müller2009; Mannette Reference Mannette2012; Sallabank Reference Sallabank and Spolsky2012, Reference Sallabank2013; Lewin Reference Lewin and Sture Ureland2015, Reference Lewin2017b; McCooey-Heap Reference McCooey-Heap2015; Wilson, Johnson, & Sallabank Reference Wilson, Johnson; and Sallabank2015; Ó Murchadha & Ó hIfearnáin Reference Ó Murchadha and Ó hIfearnáin2018), covering areas such as the institutional developments in immersion education, adult learning, the linguistic landscape, and the experiences, aspirations, and ideologies of those engaged in the language movement.

However, there has been relatively little published research on the formal linguistic features of Revived Manx varieties, or on the processes of corpus planning, pedagogy, and second language acquisition by which the language has been and is being ‘revived’, including the degree of continuity or disjuncture between the natively spoken and revived varieties. More consideration is also needed of the ways in which linguistic features interact with factors external to the linguistic code, especially the ideological stances of speakers. A small number of studies have examined specific linguistic features of the revived variety of Manx: for example, Clague (Reference Clague2004–2005) on discourse markers, Kewley Draskau (Reference Kewley Draskau2005) on verbal inflection and periphrasis, Broderick (Reference Broderick2013a) and Lewin (Reference Lewin and Sture Ureland2015) predominantly on lexis, and McNulty (Reference McNulty2019) on certain morphosyntactic features. The dissertation (Lewin Reference Lewin2016a) on which the present article is based was the first work to attempt a general overview or classification of the linguistic features of the revived language.

In this article, we shall consider a variety of phonological, morphosyntactic, and lexical features whereby Revived Manx usage may diverge from the traditional variety. These can often be shown to reflect various factors including:

• substratal influence from the societally dominant language, and L1 of most Revived Manx speakers, English;

• the impact of prominent ideological stances within the revival movement throughout its history;

• internal factors specific to the linguistic structure and orthographic tradition of Manx, both independently and with regard to their similarity to or divergence from English structures and orthography;

• inaccuracies or omissions (from the perspective of the traditional language) in key pedagogical and reference works.

The coining of new terminology is not discussed in detail in the present article, as this has been covered to a certain extent elsewhere (Broderick Reference Broderick2013a; Lewin Reference Lewin and Sture Ureland2015, Reference Lewin2017b). We also consider briefly countervailing tendencies towards maintenance of traditional features.

Sources and representativeness

Examples of the features discussed are taken primarily from a corpus of written sources dating from the mid-twentieth century onwards, as well as videos and audio recordings of interviews with Revived Manx speakers which have been published as learning resources on YouTube and Culture Vannin's learnmanx.com website; a full list of sources is given in Appendix B. More extensive analysis of this dataset is provided in Lewin (Reference Lewin2016a). I have also drawn on my own experience as a member of the Revived Manx community over the past two decades. The speakers of Revived Manx from whom the examples are derived all learnt Manx in adolescence or adulthood, and may vary in proficiency, but all can express themselves reasonably fluently and confidently and would generally be regarded within the community as ‘speakers’ rather than ‘learners’ (cf. Ó hIfearnáin Reference Ó hIfearnáin2015b:57–58).

It is difficult to say how representative the speakers are, and how widespread the features highlighted are. The revival community is small, and speakers’ pathways in terms of acquiring and using the language, as well as their current language ideologies and practices, are markedly varied, and at present there is probably not a sufficient density of speakers, especially of L1 speakers, to facilitate systematic levelling or koineization comparable to the processes of new dialect formation described by Trudgill (Reference Trudgill1986). It has been noted that networks of L2 speakers of minority languages in non-traditional environments display a high degree of variation and heterogeneity in their linguistic practices, such that it is difficult to make any straightforward generalizations about features that are characteristic of the variety (e.g. Moal, Ó Murchadha, & Walsh Reference Moal, Murchadha, Walsh, Smith-Christmas, Murchadha, Hornsby and Moriarty2018; Nance Reference Nance, Smith-Christmas, Murchadha, Hornsby and Moriarty2018). The following description of the situation of new speakers of Scottish Gaelic in Glasgow is likely to be typical of situations of this kind:

a growing community of adult new speakers plays an important role in what can be considered as the Glasgow Gaelic-speaking community. Analysis of their phonetic behaviour… suggests that, so far, there is little evidence of a consistent group variety developing. Instead, there is substantial individual variation which can be linked to explicit and implicit aims of what it means to be a new Gaelic speaker. (Nance Reference Nance, Smith-Christmas, Murchadha, Hornsby and Moriarty2018:224–25)

In a similar vein, Ó hIfearnáin (Reference Ó hIfearnáin2015a:116, Reference Ó hIfearnáin2015b:57) describes how the lack of a clearly defined target variety for Manx results in a situation where the usage of the most fluent speakers constitutes a ‘moving target’. Notwithstanding the difficulty of generalizing about the characteristics of Revived Manx, I would judge from my own experience that all of the features described here are reasonably frequently encountered in contemporary Manx speech or writing, or are at least illustrative of wider trends. Quantitative research into specific linguistic features has the potential to shed further light on the prevalence of different variants, and on the relationship between subgroups of speakers (cf. McNulty Reference McNulty2019). However, a broad-based introduction of the kind offered here may be considered a helpful initial orientation.

LANGUAGE IDEOLOGY AND LINGUISTIC FORMS

Before proceeding to examine the linguistic features, it is useful to sketch some aspects of the ideological stances towards linguistic forms prevalent within the Revived Manx community, drawing on previous discussion in the literature. There have been differences of opinion as to the aims of the Manx language movement from the beginning. Early figures in the late nineteenth century took a largely ‘preservationist’ view (Stowell Reference Stowell and Ó Néill2005:400, 406): they aimed to preserve Manx literature as an antiquarian pursuit, but saw little hope of practical revival of the language as an everyday vernacular, and in some cases were actively opposed to such an objective. Towards the end of the 1890s, pan-Celtic enthusiasm reached the island and a more radical approach was taken to teaching the language, including to children, but initial hopes in some quarters for a dramatic revival were soon frustrated as public interest waned and the realities of already advanced language shift were recognized (Broderick Reference Broderick1999:174–75; Maddrell Reference Maddrell2001:89–96).

In more recent times the ‘preservationist’ view, strictly speaking, has hardly been in evidence, with most of those involved in the language movement being committed to practical revernacularization in some form. There have, however, always been different opinions as to the appropriate degree of adherence to traditional models deriving from the native speakers and writers of the past, and the degree to which revival should entail the ‘correction’ of (real or perceived) English influence on Traditional Manx, or accept such features as part of the fabric of the language. I have described a spectrum between ‘purist’ and ‘authenticist’ (or ‘reverse purist’) stances (Lewin Reference Lewin and Sture Ureland2015, Reference Lewin2017b), which is further discussed by Ó hIfearnáin (Reference Ó hIfearnáin2015a):

Lewin (Reference Lewin and Sture Ureland2015) describes the most active Manx speakers as falling into two broad currents with regard to the nature and standard of the language. He calls them ‘purists’ and ‘authenticists’. Those who take a purist stance tend to perceive Manx as having decayed in vocabulary and grammar, particularly under the influence of English. Taking a pan-Gaelic stance, they prefer to use native words and expressions or Gaelic-derived equivalents rather than ones that display English influence, even if they are well attested in the literature and recordings of the native speakers. … Lewin (Reference Lewin and Sture Ureland2015) also highlights examples of current Manx usage which are based on Irish and Scottish models but which were not attested in Manx and a purist tendency to reject English-derived forms that might be in use in Ireland or Scotland in favour of newly-coined Manx neologisms.

In Lewin's view (Reference Lewin and Sture Ureland2015) the ‘authenticist’ stance is a form of reverse purism, minimising aspects of neology creation and pan-Gaelicism in speech and writing, instead striving to use a form of language that draws as much as possible on native classical Manx. This stance may be gaining ground as electronic access to the Bible and other classical Manx texts has facilitated access to those forms of the language. (Ó hIfearnáin Reference Ó hIfearnáin2015a:112–13)

Stowell (Reference Stowell and Ó Néill2005:406) refers to a similar dichotomy with reference to ‘preservationist’ and ‘revivalist’ wings in the membership of Coonceil ny Gaelgey (the official Manx translation and terminology committee), although these labels are perhaps not entirely accurate, as discussed above. Recently, the two currents have come to be recognized and labelled by some within the language community as ‘revivalist’ (≈ ‘purist’, Stowell's ‘revivalist’) and ‘revisionist’ (≈ ‘authenticist’, ‘preservationist’), since the latter tendency is perceived as seeking to revise established norms of the revived language in light of corpus evidence from traditional sources.

However, these ideological differences have not led to significant open conflicts or the emergence of explicit factions or named linguistic varieties (Lewin Reference Lewin and Sture Ureland2015:30; Ó hIfearnáin Reference Ó hIfearnáin2015a:113; Ó Murchadha & Ó hIfearnáin Reference Ó Murchadha and Ó hIfearnáin2018:465), unlike in the case of Cornish, for example (Davies-Deacon Reference Davies-Deacon2017). Indeed, many Manx revivalists are aware of the conflicts within the Cornish movement, and tend to regard them as a cautionary tale (Gawne Reference Gawne, McCoy and Scott2000:141; Ó hIfearnáin Reference Ó hIfearnáin2015a:116).

What I have labelled ‘purism’ has long been a predominant ideological strand within the Manx movement, as reflected notably by Fargher's influential English–Manx dictionary (Fargher Reference Fargher1979) in his lexicographical choices and in the preface of the work (Lewin Reference Lewin2017b), and can be traced to early figures in the revival such as J. J. Kneen in the early twentieth century (Maddrell Reference Maddrell2001:96–97). Lexical purism in Revived Manx is also discussed by Broderick (Reference Broderick2013a:8–26, Reference Broderick2013b:142–61) and Ó hIfearnáin (Reference Ó hIfearnáin2015a:107–09). Indeed, the dominance of this ideology is asserted without caveat by Gawne (Reference Gawne, McCoy and Scott2000:142), who was a language development officer at the time of writing:

Our lack of a native-speaking community has some advantages and many other disadvantages. The advantages include a general improvement on the grammar which was used by the native speakers and a re-instatement of Gaelic words where English words had been substituted in later spoken Manx, the most famous example being corran buigh (‘yellow crescent’) instead of banana. … We also strongly believe in using Gaelic neologisms rather than English loan-words. In creating new words we endeavour to generate words from within the Manx language, however, Manxifying Irish and Scottish Gaelic loan words comes a close second. (Gawne Reference Gawne, McCoy and Scott2000:142)

Nonetheless, an ‘authenticist’ current has long existed within the language movement, notably represented in the second half of the twentieth century by the Celtic scholar and long-term member of Coonceil ny Gaelgey, Robert L. Thomson. ‘Authenticist’ stances are characterized by a concern not to depart too far from the traditional language, and are accepting of well-established English-derived lexis or constructions, rather than ‘native’ replacements or pan-Gaelic borrowings, especially if the latter are felt to depart from the ‘character of the language’ (Thomson's words, quoted in Lewin Reference Lewin2017b:103). As noted above, such ‘authenticist’ perspectives appear to have had a new lease of life in recent years, as online publication of traditional texts in digital format as well as audio recordings of native speakers, now available on YouTube (Manx National Heritage 2017), have made such sources more accessible, and the divergences of the revived language from native usage more apparent. The long-established dominant ‘purist’ stances appear to remain widespread in the broader Revived Manx community, although there are now a number of prominent younger ‘authenticist’ voices in Coonceil ny Gaelgey and other positions of influence.

Details of the range of ideological positions both in the Manx community and elsewhere are undoubtedly considerably more complex than the simple bipolar spectrum described in the present brief discussion. Nonetheless, in broad terms, dichotomies of the kind described here have been widely observed in situations of language endangerment and revitalization including such cases as Breton (Jones Reference Jones1995; Hornsby & Quentel Reference Hornsby and Quentel2013), Cornish (Davies-Deacon Reference Davies-Deacon2017), Occitan (Costa Reference Costa2015), Corsican (Jaffe Reference Jaffe1999), Galician (Alvarez Reference Alvarez1990), Basque (Urla Reference Urla2015), Irish (Ní Ghearáin Reference Ní Ghearáin2011; O'Rourke & Walsh Reference O'Rourke and Walsh2020), and Hawaiian (Wong Reference Wong1999; NeSmith Reference NeSmith2003).

In the case of Breton, for example, most L2 speakers broadly embrace mainstream ‘Neo-Breton’ stances and linguistic practices which have been widely described as being characterized by supradialectal standardization, lexical purism (rejection of French borrowings, even if long-established in the traditional dialects), borrowings from other Celtic languages, alongside pervasive French syntactic and phonological substrate features of which speakers may be largely unaware (Jones Reference Jones1995; Le Pipec Reference Le Pipec2013; Hornsby & Quentel Reference Hornsby and Quentel2013). Some revivalist speakers, however, espouse what Hornsby & Quentel (Reference Hornsby and Quentel2013:78–82) label as a ‘native authenticist’ ideology: they valorize native dialectal varieties, attempting to acquire and use these as far as possible, and reject the conscious lexical purism of mainstream Neo-Breton. This is broadly comparable to the Manx situation, with the main difference that the possibility of direct interaction with native speakers and their linguistic varieties is no longer part of the picture in the case of Manx.

It has been suggested that puristic stances tend to emerge as the default ideology of many language revitalization movements because such assumptions are congruent with the dominant discourses concerning purity, monolingualism, and homogeneity in established standard (European or Western) national languages (Jaffe Reference Jaffe1999:146–59, 185–90, 271–85), which are internalized by speakers of the minority language. In Jaffe's (Reference Jaffe1999:23) terms, a ‘resistance of reversal’, which resists the outcomes of language domination but not its underlying ‘structures of value’, arises more readily within revitalization movements—and seems more intuitive to most speakers, immersed as they are in the ideological frames of the dominant culture—than ‘radical models of resistance’ (Jaffe Reference Jaffe1999:29) which challenge dominant assumptions around monolingualism, linguistic standardization, and identification of language with nation. Alternative stances are more likely to arise at a subsequent stage among those who begin to perceive and problematize the growing gap between traditional and revitalization varieties, and among those aware of and influenced by the descriptivist assumptions of most contemporary linguistics.Footnote 2 They seem particularly likely to emerge among those engaged in professional or amateur scholarship of the traditional variety of the language in question, that is, individuals with significant metalinguistic awareness of the different varieties, and personal investment in knowledge of the historical vernacular norms. Of course, ideological stances which originate in an intellectual subgroup (a ‘counterelite’, in Hornsby & Quentel's (Reference Hornsby and Quentel2013:78) terms), without necessarily having buy-in from the wider language community, are not unproblematic in terms of power dynamics and potential accusations of elitism, not to mention practical effectiveness and reach, even if, as in the case of the so-called ‘sociolinguistic’ ideology of polynomie in the case of Corsican, they are explicitly intended to be egalitarian and inclusive (Jaffe Reference Jaffe, Creese, Martin and Hornberger2008; Sallabank Reference Sallabank2010).

As discussed by Ó hIfearnáin (Reference Ó hIfearnáin, Eloy and Ó hIfearnáin2007:167), an overarching priority for most Revived Manx speakers—regardless of their particular views on linguistic details—has been pragmatism, and a concern not to let questions of linguistic form get in the way of the expansion and elaboration of the language movement. This kind of pragmatism, however, tends to be most closely allied with the dominant purist ideology—not necessarily because there is a direct or inherent link between the two, but because individuals with relatively little personal interest or investment in formal linguistic questions and metalinguistic debates are likely to gravitate to whatever the majority view on these matters happens to be.

SUBSTRATAL FEATURES

As would be expected from the literature on language contact and second language acquisition, as well as language revitalization and revival more specifically, substratal impacts from English, the first language of most Revived Manx speakers, are widespread.

Loss of syllable-final r, intrusive r

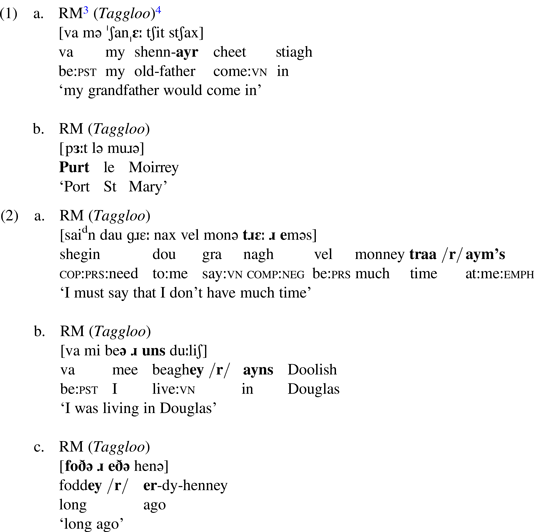

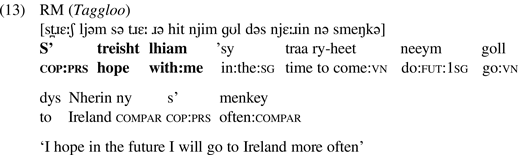

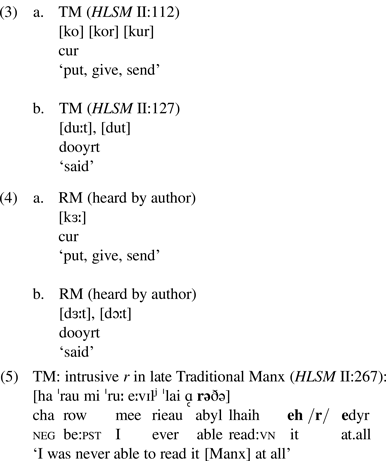

The phenomena of loss of syllable-final /r/ in (1) and intrusive /r/ in (2) are very frequent (the relevant syllables are highlighted in bold). These well-known developments are typical of many varieties of English, including that of the Isle of Man (Jackson Reference Jackson1955:118; Hamer Reference Hamer and Britain2007:173), but are not otherwise usual in Gaelic varieties.

Both of these phenomena were found to some extent in the Traditional Manx of the last speakers recorded in the mid-twentieth century (see (3) and (5) below), and rhotic deletion is already reported in the nineteenth century (Rhŷs Reference Rhŷs1894:148), although the details are somewhat different. In Traditional Manx the loss of /r/ did not necessarily alter the preceding vowel as in (3), whereas in Revived Manx the vowel often corresponds to English pronunciation as in (4) where earlier /ʊr/, /ɛr/, /ɪr/ have all become /ɜː/, and traditional /ʊə/ (</uːr/) (retained in conservative varieties of both Received Pronunciation and Manx English) is increasingly smoothed to a long monophthong.Footnote 5

Interchange of emphatic and non-emphatic pronouns

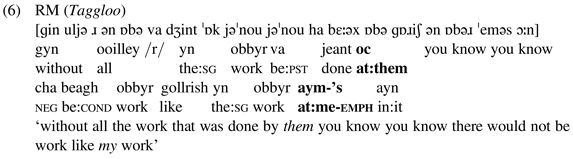

Some Revived Manx speakers appear not to control fully the pragmatic difference between plain and morphologically marked emphatic pronouns found in Traditional Manx.Footnote 6 Such emphatic pronouns are characteristic of the Gaelic languages and are generally used in contexts where English would employ heavy phonetic stress to indicate an explicit or implied contrast between two or more actors. In (6) the non-emphatic prepositional pronoun oc ‘by them’ (Ir. acu) is phonetically heavily stressed and is pragmatically contrastive with the speaker's reference to himself, but lacks the expected emphatic suffix (ocsyn, Ir. acusan), whereas it appears as expected in aym's ‘at me, my’ (Ir. agamsa).

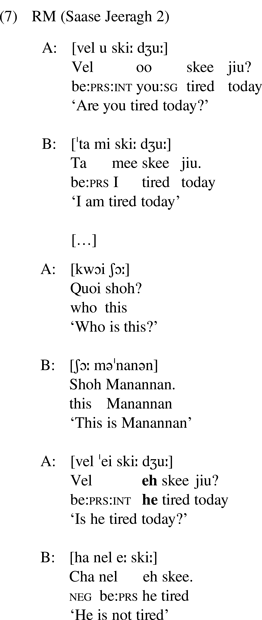

In (7), we find the plain form used in an emphatic context in a video from a series of Manx lessons, perhaps because the emphatic forms have not yet been taught at this point in the course. In the exchange, A uses the plain pronoun eh ‘he’ with heavy stress where the emphatic form eshyn would be expected.

The unfamiliarity of the Gaelic plain-emphatic distinction to L1 English speakers is likely to make it difficult to acquire in any case, and the pedagogical choice in (7) may increase the probability of fossilization of the non-traditional usage.

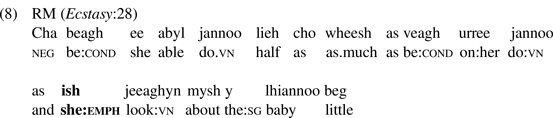

Some Revived Manx speakers seem to have reanalysed the emphatic pronouns as something akin to the disjunctive pronouns of French (moi, toi, etc.), or the generalized disjunctive use of the historical object pronouns in English (e.g. ‘It's me’), that is, stressed pronominal forms used in syntactic environments other than verbal subject or direct object. For example, the emphatic pronouns are frequently used in circumstantial clauses introduced by subordinating as ‘and’ (G. agus, is) (see e.g. Ó Siadhail Reference Ó Siadhail1991:284–87 and Vennemann Reference Vennemann and Aziz Hanna2012:189–93 for descriptions of this clause type in Irish), irrespective of the pragmatic or semantic nuances conveyed by the distinction between plain and emphatic pronouns in Traditional Manx. In (8) the emphatic form ish ‘she’ (Ir. ise), as opposed to plain ee (Ir. í), would in Traditional Manx imply contrast with another actor, but no one else is mentioned: the passage concerns the effects of the fact that the character has to look after the baby, not about whether it is she or someone else who is looking after it; nor is there a pragmatic contrast between her and the baby.

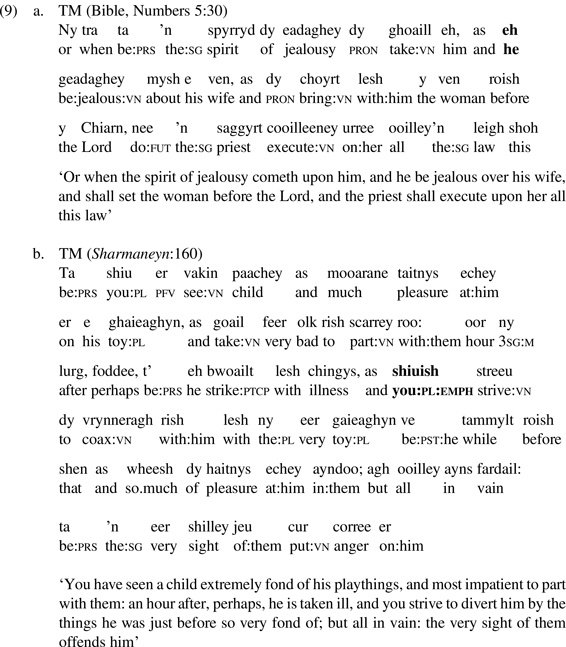

Compare the Traditional Manx examples (9a) where there is a plain pronoun and no contrastive sense, and (9b) where there is an emphatic pronoun and an element of contrast between emphatic shiuish ‘you’ and the child.

FEATURES REFLECTING DOMINANT LANGUAGE IDEOLOGY

Certain features may be interpreted as reflective of the dominant ‘purist’, pan-Gaelic language ideology discussed above. It is known that removal of English influence was a priority for revivalists such as the lexicographer Douglas Fargher (Lewin Reference Lewin2017b), as the following quotation from the preface of his English-Manx dictionary shows:

It always appalled me to hear the last few native speakers interspersing accounts of their travels in Manx with the anglicised renderings of Gaelic names. This unnecessary dependence upon English cannot be tolerated if the Manx language of the future is to survive in its own right, and has, therefore, been discouraged here. (Fargher Reference Fargher1979:vi)

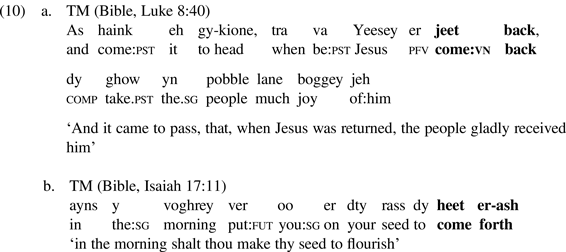

Avoidance of long-standing loanwords

In Traditional Manx, including in the Bible translation, the English loanword back is generally used for the adverb sense of returning to a prior location as in (10a), where a(i)r ais would be usual in other Gaelic varieties. The cognate native adverbial er-ash exists in Traditional Manx, but has developed specialized senses of ‘flourishing, blooming’ or ‘coming to light after being lost’ as in (10b) (Broderick Reference Broderick2013a:18–20; Lewin Reference Lewin and Sture Ureland2015:25).

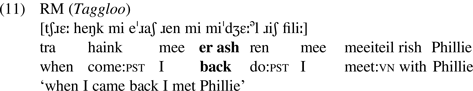

For many speakers of Revived Manx however, er-ash is used for ‘back’ as in (11) and the Traditional Manx sense of er-ash is unknown. Thus a potentially useful semantic distinction is lost.

Hyper-Gaelicisms

Another type of purism concerns the coining of new constructions which apparently are felt to be closer to the spirit of Gaelic idiom (and less similar to English constructions), even if the exact structure in question, or context of usage, does not exist either in Traditional Manx or other Gaelic varieties. These we term hyper-Gaelicisms.

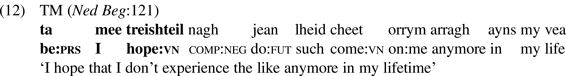

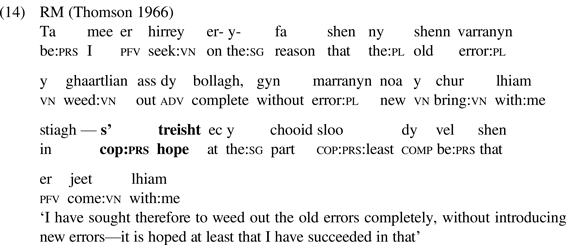

For example, in Traditional Manx ‘I hope’ was generally expressed by the regular verb treishteil (also ‘trust’) as in (12).

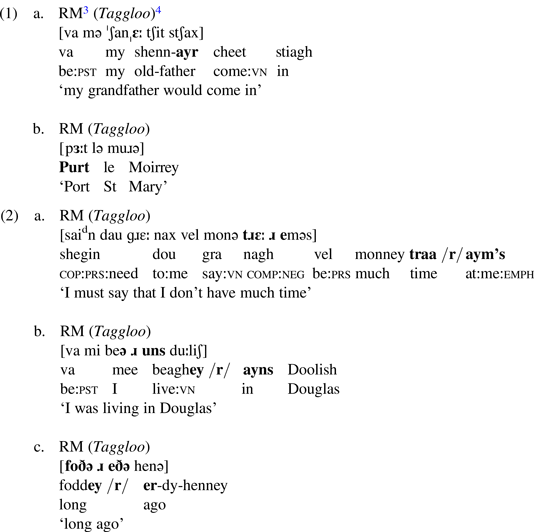

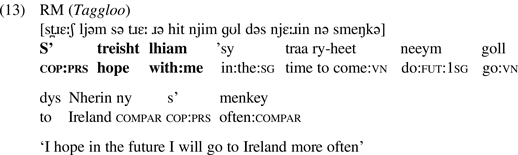

However, many speakers of Revived Manx are more familiar with, and regularly use, a copula and preposition construction s'treisht lhiam (lit. ‘is hope with me’) as in (13), which is unattested in the traditional language. Fargher's (Reference Fargher1979:393–94) dictionary has only jerkal (also ‘expect’, sometimes ‘hope’ in TM) and ta treisht aym lit. ‘I have hope’, suggesting that the construction has become established in the revived language more recently.

An early occurrence, but without the prepositional pronoun, is found in Thomson's preface to his edition of Goodwin's First lessons in Manx, shown in (14).

No construction of the type is X le (copula + noun + experiencer headed by preposition le ‘with’) is in common use for ‘to hope’ in any Gaelic variety (cf. Ir. ta súil agam ‘I have hope’, lit. ‘I have an eye’, or tá mé ag súil ‘I am hoping’; ScG. tha mi an dòchas ‘I am in hope’). The Revived Manx innovation is part of a wider tendency to expand the use of copula structures, which are apparently felt to be more distinctively Gaelic and less English (Lewin Reference Lewin2016a:64–73).

Hyper-archaisms

Especially in written Revived Manx, there may be attempts to restore older features. For example, Kewley Draskau (Reference Kewley Draskau2005) has noted a tendency towards increased use of inflected verb tenses (e.g. vrie mee ‘I asked’) as opposed to the semantically interchangeable ‘do’-periphrasis (ren mee briaght lit. ‘I did ask’), contrary to the diachronic trend in the traditional language.

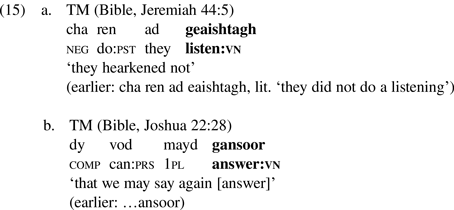

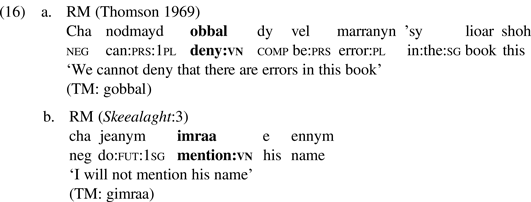

Forms may be restored to those considered historically ‘correct’, even when these may in fact have been obsolete or ungrammatical in attested periods of the traditional language, as shown by the following case. The progressive proclitic *ag (originally a preposition ‘at’) has been elided entirely in Manx apart from the survival of the consonant /ɡ/ as a prefix on vowel-initial verbal nouns, as in geaishtagh ‘listening’, Ir. ag éisteacht, lit. ‘at listening’. By the eighteenth century it had become usual to prefix this g- to vowel-initial verbal nouns in other constructions besides the progressive as in (15).

I have argued that the g- prefix had been reanalysed as a general marker of non-finite verbs in Classical Manx, to the extent that omission of g- (with a few lexical exceptions) in the non-progressive constructions was probably no longer grammatical (Lewin Reference Lewin2016b:191–99). In Revived Manx, however, bare forms of the verbal noun without g- are sometimes found, as in (16).

It is likely that this represents conscious restoration of the historical, perceived more ‘logical’ construction, especially in view of the fact these are written sources and Thomson (see (16a)) was a professional scholar of the Gaelic languages.

MAINTENANCE OF TRADITIONAL FEATURES

Although the focus in this article is primarily on ways in which Revived Manx usage diverges from the historical language, it is worth noting that there are also instances of retention of traditional elements, especially of pronunciation, even where these are not indicated in writing. These can be considered part of the oral tradition of the revival, having been acquired by the mid-twentieth-century revivalists who interacted with the final traditional speakers (cf. Ó Murchadha & Ó hIfearnáin Reference Ó Murchadha and Ó hIfearnáin2018:464).

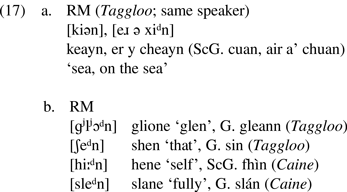

Preocclusion

Preocclusion is a feature of Traditional Manx involving the insertion of an often weakly articulated homorganic stop before final liquids in stressed syllables (Rhŷs Reference Rhŷs1894:142–44; Jackson Reference Jackson1955:113–15; Broderick Reference Broderick1984–1986:vol. 3, 28–34; Lewin Reference Lewin2020:308–36), not found in other Gaelic varieties. Preocclusion has never been written in the standard orthography, but is quite widely encountered in Revived Manx (see (17)). It seems to be especially common in certain words and therefore may be considered to have been lexicalized by revival speakers. The articulation may also be somewhat different from Traditional Manx, being more distinctly articulated and more likely to be realized syllabically (cf. English syllabic liquids in words such as paddle). Usage is variable; in (17a) the same speaker has the same item with and without preocclusion.

Features such as preocclusion in Revived Manx are likely to represent retention or restoration of particularly salient or iconic linguistic features (i.e. distinctively ‘Manx’ as opposed both to English and other Gaelic varieties), which are seen as a link to the historical language and thus a marker of linguistic authenticity (cf. Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000; Ó hIfearnáin Reference Ó hIfearnáin2015b:56–57; McNulty Reference McNulty2019:17, 55–56). They can fulfil this iconic function at the same time as other features of the traditional language are disregarded or altered, whether knowingly or unknowingly.

Dialect

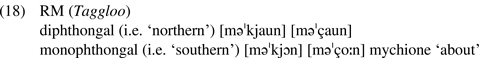

Traditional Manx is recognized as having had a primary dialect distinction between north and south (Rhŷs Reference Rhŷs1894:160–61; Broderick Reference Broderick1984–1986:vol. 3, 160–66), although the differences are relatively slight. Speakers from both regions survived into the mid-twentieth century and were recorded and interacted with the revivalists. Revived Manx speakers today tend to have features historically associated with both southern and northern Manx, although metalinguistic awareness of the traditional dialects seems to be low for the majority of speakers. In some cases, a pronunciation reflecting one dialect has become widespread, even though the spelling better represents the other dialect. It is possible that these represent further cases of iconization of traditional, orthographically non-transparent pronunciations.

For example, a diphthongal pronunciation of the word kione ‘head’ (G. ceann) and the compound mychione (preposition ‘about, concerning’) is frequent, reflecting the northern form, although the spelling better represents the southern monophthongal realization as in (18).

Similarly, the historically northern pronunciation of shenn ‘old’ (G. sean) with /a/ is considerably more common in Revived Manx than southern and orthographic /e/ (cf. Broderick Reference Broderick1984–1986:vol. 2, 398).

A few speakers make a conscious effort to adopt one dialect or the other. This includes both the handful remaining who had personal contact with particular traditional speakers, as well as newer speakers making use of the recorded and transcribed material. For example, the revival speaker interviewed in (19) uses the northern diphthongal form [ei] for oie ‘night’ (G. oidhche), rather than the southern form [iː] which is usual in revival speech.

(19) RM (Crellin)

Interviewer: [kiɹəd te ɡɹɛː son iː vai]

C'red t'ou (?) gra son ‘oie vie’?

what be:prs:you:sg say:vn for night good

‘What do you (?) say for oie vie (goodnight)?’

Interviewee: [ei vai eɹ ə tuːi]

‘[ei vai] oie vie’ er y twoaie

night good on the:sg north

‘[ei vai] in the north’

INTERNAL LANGUAGE-SPECIFIC FACTORS

Internal analogy and overgeneralization

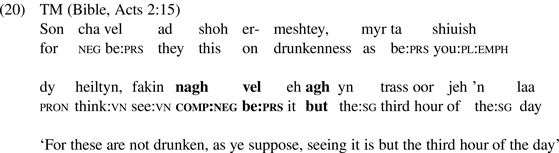

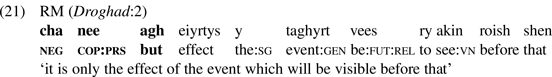

Some divergences from Traditional Manx usage cannot be attributed directly to English influence per se, but rather to internal analogy or overgeneralization. That is, speakers innovate features or patterns that might appear to be logically possible—or even required—in the structure of the traditional language, but which are in fact unattested, or were expressed in other ways, and appear to have been ungrammatical or at least dispreferred in the historical variety. For example, in Manx the concept ‘only’ can be expressed with a negative verb and agh ‘but’ in (20), as in Irish (Ó Siadhail Reference Ó Siadhail1991:218).

In Revived Manx the negative copula cha nee is sometimes found in clefting structures followed by agh ‘but, only’ in the sense ‘it is only’ as in (21).

As far as is known, this configuration is unattested in Traditional Manx,Footnote 7 even though clefting is very frequent otherwise. That these two focusing constructions appear to be syntactically incompatible in the traditional language is perhaps related to the fact that clefting locates the focused item to the left edge of the clause, whereas the agh construction favours shifting of the focused constituent rightwards (cf. McCloskey Reference McCloskey1980:64–66).

Spelling pronunciations

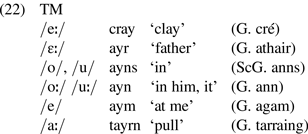

The Manx orthography, which is based largely on English conventions but with significant innovations to represent distinctive Manx sounds, is notorious both among scholars and revivalists for its complexity and inconsistency (Ó hIfearnáin Reference Ó hIfearnáin, Eloy and Ó hIfearnáin2007; Lewin Reference Lewin2020:59), although no serious replacement has ever been proposed. It is unsurprising that spelling pronunciations are frequent, some of which have become well established.

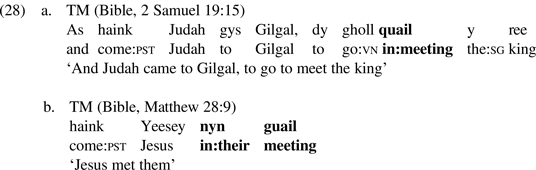

For example, the digraph <ay> may represent a variety of vowel sounds as in (22).Footnote 8

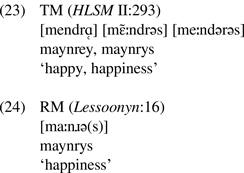

The adjective maynrey ‘happy’ is expected to have /eː/ (G. méanar, méanra < Early Irish mo-génar) and is attested thus in Traditional Manx speech as in (23), but frequently has [aː] in revival speech as in (24).

The revival pronunciation may be traced to Kneen's English-Manx pronouncing dictionary (Reference Kneen1938:38) as in (25).

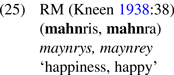

The Manx orthography usually roughly follows the Modern English values of the vowel symbols (i.e. the outcomes of the Great Vowel Shift), but sometimes the latinate values are found, as also in English (cf. combine and machine). This leads to confusion, for example, in the following pair in (26) and (27), which I have heard confused in RM speech.

Incomplete or erroneous information in reference works

Certain forms attested in Revived Manx can be shown to derive from erroneous or incomplete descriptions of the traditional language in the tradition of the revival, as documented and transmitted in widely used reference works.

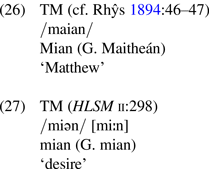

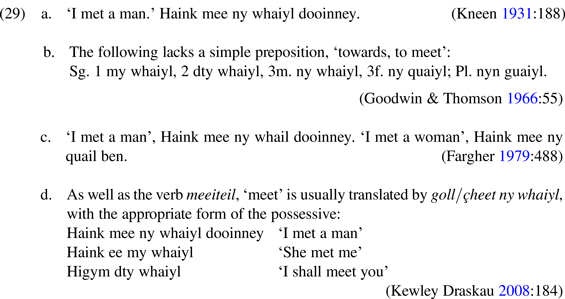

In Manx there is a class of complex prepositions formed from an original simple preposition together with a noun, and with pronominal forms involving possessives (analogous to English ‘for my sake’, ‘in his stead’). Sometimes there is elision of the original simple preposition. An example in Traditional Manx is quail ‘towards, meeting’ (G. i gcomhdháil ‘in the meeting (of)’), which as expected has pronominal forms based on the possessives, given in (28).

The preposition quail followed by a noun phrase complement in (28a) is well-attested in Traditional Manx sources. However, a misconception about this has appeared in various reference works in (29), where it is stated or implied that the possessive is required even when there is a non-pronominal complement. According to Fargher (Reference Fargher1979:488), there is agreement with the gender and number of the complement as in ny quail ben ‘to meet a woman’ (29c), cf ny quail ‘towards her’. Such constructions are not found in with any other complex preposition in Manx or in other Gaelic varieties.

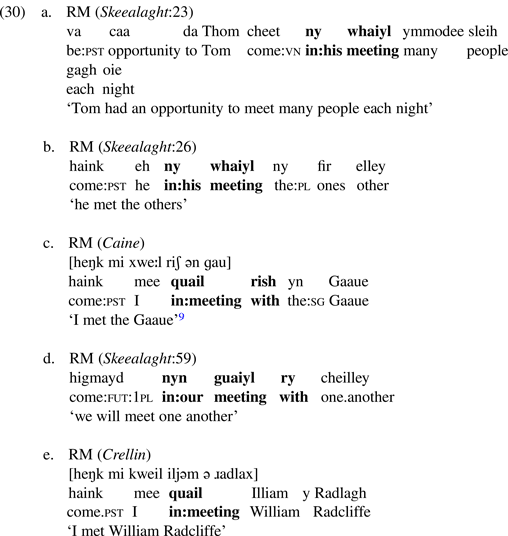

Accordingly, the redundant possessive is often used in Revived Manx in (30) (albeit in these examples without number agreement), as well as another innovating variant where it is compounded with the preposition rish ‘to, with’ as in (30c), perhaps reflecting the synonymous construction meeiteil rish ‘to meet (with)’, and a mixed form with both possessive and rish as in (30d). The Traditional Manx construction with simple quail + nominal complement is also found in revival usage as in (30e).

It is clear that the variety of forms in (30) reflects the existence of conflicting models: the usage of the traditional language (and the analogy of other complex prepositions) on the one hand, and the prescriptions of several notable Revived Manx reference works in (29) on the other. The persistence, from the 1930s to the 2000s, of the belief that the preposition quail lacks a non-conjugated form, and that the conjugated forms can be combined with a governed noun phrase, is striking. No other structure in the language behaves like this, so the innovation runs contrary to the rationalizing, analogical tendency discussed above. It is clear testimony to the abiding influence of successions of reference works and the usage of influential individuals in the revival which have been accorded authority within the community.

CONCLUSION

The present article has presented a typology of characteristic innovating features of contemporary Manx, a postvernacular language in the process of revival within a relatively small network of second language speakers and learners. We have traced a complex set of internal and external factors which are likely to be present in any language revival scenario, as well as particular traits of the linguistic and orthographic relationship between Manx and English, and specific historical developments and ideological trends in the course of the revival.

The kind of ‘hybridization’ noted by Zuckermann (Reference Zuckermann2009) in the case of Israeli Hebrew is clearly apparent in Revived Manx; however, there is also an ongoing dynamic of malleability whereby features of the target variety remain fluid and variable in the absence of a definitive ‘founder generation’ and subsequent nativization as a dominant L1. Although we have seen that there is clearly a specific oral and written tradition within the Manx revival which has a significant impact, for example, through perpetuating idiosyncrasies from earlier textbooks, or certain traditional phonological features, nevertheless each succeeding generation of revival speakers remains in some sense part of an extended ‘founder generation’, able consciously to reshape the language and introduce or restore features in a non-linear fashion.

This can be regarded as a symptom of the relative weakness of the language revival and its failure to achieve robust intergenerational sociolinguistic vitality; however, the current fluidity of the language's norms can also be viewed more positively as empowering present and future cohorts of Manx speakers. The future development of the language is subject to their conscious reflexive choices in a way not true of ‘natural’ L1s—including, now, Hebrew (cf. Blanc Reference Blanc1957:399). In the latter, language change is largely an incremental and unconscious phenomenon, and deliberate manipulation of the linguistic code plays only a small part; whereas in a small network of L2 revival speakers, influential individuals, groups, or publications can potentially have a disproportionate impact in modifying linguistic norms and practices. This has been true over past decades in the Manx revival community, and is likely to remain the case.

The features of Manx which have been noted in this article are thus not necessarily set in stone to the degree they might be had Revived Manx gained a significant cohort of native speakers in the earlier stages of the revival, as occurred in the case of Hebrew. In the present circumstances, it is unclear whether and to what extent the ideological stances discussed above will continue to be as influential in the Revived Manx community as they have been to date, and how far future norms will adhere to or diverge from models derived from the traditional language. These questions are to a significant degree in the hands of Manx speakers themselves as they participate in an ongoing project of creative renewal and reimagining the language they have chosen to (re)claim and make their own. As discussed above, this is likely to be true of many other language revitalization contexts in which adult L2 learners are numerically dominant, and where traditional native speakers are absent, or contact with them is limited.

Appendix A: Abbreviations

General abbreviations:

- G.

Gaelic (Irish or Scottish Gaelic)

- Ir.

Irish

- lit.

literally

- RM

Revived Manx

- ScG.

Scottish Gaelic

- TM

Traditional Manx

Glossing abbreviations:

- adv

adverbial

- comp

complementizer

- compar

comparative/superlative

- cond

conditional

- cop

copula

- emph

emphatic

- fut

future

- gen

genitive

- int

interrogative

- m

masculine

- neg

negative

- pfv

perfective

- pl

plural

- pron

pronominal particle

- prs

present

- pst

past

- ptcp

participle

- rel

relative (verb form)

- sg

singular

- vn

verbal noun/verbal noun particle

- 1, 2, 3

first, second, third person

Appendix B: Primary sources

Revived Manx sources:

Spoken material:

- Caine

Culture Vannin. Bernard and Joan Caine Interviews. Online: http://www.learnmanx.com/cms/video_collection_79769.html; accessed January 18, 2021.

- Crellin

Culture Vannin. Juan Crellin [interviews]. Online: http://www.learnmanx.com/cms/video_collection_31498.html; accessed January 18, 2021.

- Saase Jeeragh

Culture Vannin. Saase Jeeragh video files. Online: http://www.learnmanx.com/cms/video_collection_74051.html; accessed January 18, 2021. Reference is to the number of the lesson.

- Taggloo

Culture Vannin (2014). Taggloo: Conversational Manx. Online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lPygOMM8Fk4&list=PLY5y-gRhKs8gmP0sMWYlmp25dl1b0TWeu; accessed January 18, 2021. YouTube playlist.

Written material

- Droghad

Lewin, Christopher (2010). Droghad ny Seihill. Douglas: Yn Cheshaght Ghailckagh.

- Ecstasy

Ó Laighléis, Ré, & Robert W. K. Teare (trans.) (2008). Ecstasy as Skeealyn Elley. St Judes: Yn Cheshaght Ghailckagh.

- Lessoonyn

Culture Vannin. Lessoonyn Meanagh. Online: http://www.learnmanx.com/cms/inter_lesson_index.html; accessed January 18, 2021. References are to the number of the lesson.

- Skeealaght

y Crellin, Lewis; Juan y Crellin; Colin y Jerree; & Shorys y Creayrie (1976). Skeealaght. Douglas: Yn Cheshaght Ghailckagh.

- Thomson 1966

Thomson, Robert L. (1966). Gys y lhaihder [To the reader]. In Edmund Goodwin & Robert L. Thomson, First lessons in Manx. Lessoonyn ayns Chengey ny Mayrey Ellan Vannin. 3rd edn. Douglas: Yn Cheshaght Ghailckagh.

- Thomson 1969

Thomson, Robert L. (1969). Gys y lhaihder [To the reader]. In Archibald Cregeen, A dictionary of the Manks language. 3rd edn. Menston: Scolar Press.

Traditional Manx sources:

- Bible

Bible in Manx, 1819 Bible Society edition. Online: https://www.bible.com/versions/1702-bib1819-yn-vible-casherick-1819; accessed January 18, 2021.

- HLSM

All examples of Traditional Manx speech are from George Broderick (Reference Broderick1984–1986), A handbook of Late Spoken Manx, 3 vols. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Ned Beg

Broderick, George (1981). Manx stories and reminiscences of Ned Beg Hom Ruy. Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie 38:113–78.

- Sharmaneyn

Wilson, Thomase (1783). Sharmaneyn liorish Thomase Wilson [Sermons by Thomas Wilson]. Bath: Cruttwell.