1. Introduction

The last few decades have witnessed a vivid interest in expressive language, that is, language that does not merely describe the world, but appears to express evaluations and attitudes toward it in a distinctive way. In this paper, we focus on a particular kind of terms that we call negative expressives, namely, terms such as jerk, bastard or idiot, and we investigate what kind of meaning is attached to such words.Footnote 1 It is often assumed in the literature that the meaning of expressives is attitudinal, in the sense that an agent who uses a negative expressive like jerk in reference to someone thereby expresses a negative attitude about this person. Expressives are taken to be distinctive linguistic devices used to convey the speaker’s emotions and feelings. In this influential view, the content associated with negative expressives amounts to something like ‘the agent has a negative attitude toward the target’. We call this assumption agent-orientedness, and we contrast it with an alternative assumption, target-orientedness, according to which the meaning of a negative expressive is more directly about the person for whom the expressive is used. In this account, calling someone a jerk means, in a nutshell, calling them a bad person. Notice that on both assumptions the content at stake is evaluative in nature, but the former is about the speaker’s feelings and attitudes, while the latter is about the target’s features. We can better appreciate the difference between agent- and target-orientedness by contrasting the judgment that a speaker expresses by saying ‘I hate this’ as opposed to ‘This is hateful’ (or ‘I dislike this’ versus ‘This is dislikeable’, and, more generally, ‘I find this such-and-such’ as opposed to ‘This is such-and-such’). The former is about the speaker’s attitudes toward a target, the latter is about the target’s properties.Footnote 2 Yet, a third possibility is that nominal expressions such as jerk are special in that, unlike expressives such as ‘damn’ or ‘fuck/ing’, which are syntactically unconstrained and only serve to express negative emotions, and unlike descriptions such as ‘a bad person’, which only serve to attribute badness to a person, they simultaneously express and describe; in other words, they are mixed expressives, in the terminology of McCready (2010) and Gutzmann (Reference Gutzmann2015).

In this work, we investigate the content associated with negative (mixed) expressives such as jerk. Spelling this out is crucial for a deeper understanding of what expressives are, how they work and what conversational and normative effects they bring about. Suppose that in a conversation with Luca and Claudia, Sofia says ‘Marco is a jerk’. No one protests, and their chat goes on without a hitch. How did Sofia’s utterance update the conversational context? The conversational import of expressives will be characterized along very different lines depending on how one cashes out the associated content. According to the agent-oriented view, jerk simply reflects Sofia’s feelings, which does not make it common ground that Marco is bad in any way, only that she dislikes him. According to the target-oriented as well as the mixed-expressive views, in contrast, jerk implies that the target is, roughly, a bad person. Updating the conversational context with such information about Marco does not only involve Sofia’s feelings, but also Luca and Claudia, the other participants who accept that Marco is a bad person, at least for the purposes of that exchange. The former account predicts that Sofia’s use of jerk should, prima facie, commit only her to a negative evaluation of Marco; the latter accounts predict that her utterance also commits her interlocutors Luca and Claudia, since they accept (at least in the context of that conversation) that Marco is a bad person.Footnote 3 The normative power of negative expressives turns out to differ considerably between these views.

Getting a clearer picture of the content associated with negative expressives can shed light on the normative impact of these terms and make a valuable contribution to the understanding of expressive meaning more generally. In this paper, we undertake this task by means of two experimental studies: a rating task and a selection task. The two studies, presented respectively in Sections 3 and 4, aim to empirically assess the assumptions of agent- and target-orientedness. Before presenting the studies, we take a brief look at the current theoretical landscape (Section 2.1), and we offer some informal insights as to how experimental studies try to address the theoretical issues under consideration (Section 2.2). Section 5 discusses the implications of our studies for theories of expressives, while Section 6 concludes.

2. By way of background: theoretical and experimental work on expressives

2.1 Two widely shared assumptions about negative expressives

In the literature, negative expressives are almost exclusively discussed in their referential use, that is, when they occur in a referential phrase that picks out some specific person (Kaplan 1999, Potts 2005, Reference Potts2007, Hess Reference Hess2018, Gutzmann Reference Gutzmann2015). Consider the following question, asked by a certain Narelle Christine in a Facebook discussion:Footnote 4

(1) Has anyone ever seen that jerk Trump smile?

It is widely assumed that the phrase that jerk does not contribute to the truth-conditional content of the question asked; the latter amounts to the descriptive at-issue content, namely, whether anyone has ever seen Trump smile. The expression that jerk serves to depict Trump in a negative light. Many scholars in the literature would say that what Narelle asks in (1) is whether anyone has seen Trump smile, but she additionally conveys her negative attitude about him. The idea, in a nutshell, is that the expressive (that) jerk conveys the information that the speaker has a negative attitude toward the target. What is more, this information projects from the environment in which it is embedded; in other words, even though it occurs within a question, it is not a part of what Narelle is asking.

An influential proposal from Potts (2005, 2007) is to analyze such expressive contents in terms of conventional implicatures, i.e., non-at-issue contents conventionally attached to certain lexical items. These secondary contents indicate that the speaker feels negatively about the target. They are independent from ordinary descriptive content, they always refer to the utterance situation and they are evaluated from the perspective of some particular agent, who is typically the speaker.

A different but similar proposal from Schlenker (Reference Schlenker2007) is to analyze expressives as triggers of a special kind of presupposition, along the following lines:Footnote 5

⟦That jerk x F⟧c is defined if the speaker in c has a negative attitude toward x; if defined, then ⟦That jerk x F⟧c = ⟦x F⟧c.

The presupposition triggered by jerk is special in that it is indexical and attitudinal. It is attitudinal because it conveys information concerning the attitudes of an agent. It is indexical because the agent in question is the speaker of the context of utterance. An interesting consequence is that such a presupposition is ‘self-fulfilling’, in the sense that it is accommodated automatically. By uttering the phrase that jerk, speakers communicate that they are in the correct state of mind that satisfies the presupposition that they have a negative attitude toward the target.

Note that according to both proposals, the use of expressives imposes no special requirement on the context of utterance. Conventional implicatures, as foreground contents, do not require any backgrounded information. Presuppositions, on the other hand, usually do, but not in this case, since, as we have just explained, they are self-fulfilling. It does not come as a surprise, then, that Tonhauser, Beaver, Roberts and Simons (Reference Tonhauser, Beaver, Roberts and Simons2013) analyze expressives as lexical items associated with projective contents that do not impose what they call a ‘strong contextual felicity constraint’. In other words, using an expressive like jerk does not require that the context should entail any information as to whether the target is to be held in low opinion or whether the speaker (or, for that matter, anyone else) feels negatively about the target. For Tonhauser et al. (Reference Tonhauser, Beaver, Roberts and Simons2013), this trait distinguishes expressives from other kinds of items associated with projective contents, such as the additive adverb too.

We can now extrapolate from these different proposals two claims on which all these authors ultimately agree. Those claims constitute what we take to be the influential view of expressives.

Claim 1: the content associated with expressives is attitudinal and agent-oriented.

In other words, many existing accounts of (negative) expressives converge on the idea that the expressive content is about an agent’s attitudes and that, in general, the relevant agent is the speaker. In the words of Gutzmann (Reference Gutzmann2019: 16):

“In contrast to descriptive predicates, expressive[s] always seem to be evaluate[d] from the perspective of an attitude holder, which seems to default to the speaker but can also be instantiated by another salient attitude host”.

Expressives are taken to communicate how an agent (typically the speaker) feels rather than what the target is like Footnote 6. When Narelle asks if anyone ‘has ever seen that jerk Trump smile’, the content associated with that jerk is that Narelle feels negatively about Trump, regardless of what kind of person Trump is and what other people think of him or how they feel about him.

Claim 2: the use of expressives imposes no strong contextual felicity constraint.

The underlying idea is that for Narelle’s question, or any other utterance containing the phrase ‘that jerk Trump’, to be felicitous, there should be an individual (Trump) for the complex demonstrative to refer to, but no other information is required to be in the common ground. In particular, using the expressive jerk does not require that the associated expressive content should already be entailed by the context.

It is important to stress from the outset that not everyone agrees with the influential view. In the next section, we will discuss some criticisms that this view has received on empirical grounds, and which we aim to expand by the results of our own experiments. But, equally importantly, some may be reluctant to consider expressions such as ‘jerk’ as bona fide expressives at all. In this line of thinking, expressive terms are exemplified by exclamative expressions such as ‘ouch’, ‘oops’ or ‘damn’. This leaves open the possibility that other expressions may have some expressive aspects. This idea may be traced back as far as Frege’s claim that some expressions, such as ‘dog’ and ‘cur’ can have the same sense (and, of course, the same reference) but still differ in terms of coloring or tone (see also Cruse Reference Cruse1986: 274). In more recent theorizing, McCready (2010) and Gutzmann (Reference Gutzmann2015) developed the notion of mixed expressives. While ‘damn’ only communicates a negative perspectival expressive content, epithets such as ‘jerk’, as well as slurring terms, may be seen as communicating both expressive and a descriptive content.Footnote 7 Note, though, that the very idea of a mixed expressive conflicts with Potts’ hypothesis that ‘no lexical items contributes both an at-issue and a CI-meaning’ (Potts 2005: 7). This being said, it still remains a widely shared assumption that at least in their nominal uses, as in ‘that jerk Trump’ such epithets behave as bona fide expressives. In fact, since the influential work of Potts (2005), many researchers have taken it for granted that expressive nominals like idiot, bastard or jerk are pure expressives with no descriptive content when they are used ‘ad-nominally’, even if they may have descriptive content when they are used predicatively.

2.2 Empirical challenges to the agent-oriented interpretation of expressive content

In this paper, we report the findings of two experimental studies that aim to test the assumption that the content of expressives is attitudinal and agent-oriented (which lies at the core of Claim 1 of the classical influential view). Before we present our studies, let us point to some previous studies that tried to engage with such a view. First, the studies in Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic (Reference Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic2021) present a challenge to Claim 2. Their main study investigated whether the Italian expressive stronzo (equivalent to the English jerk) imposes a strong contextual felicity constraint. For that purpose, they asked participants to rate various sentences for acceptability on a 1-to-5 point Likert scale. They used a 2x2x2 design. The first point of comparison was between the expressive stronzo versus non-expressive controllers, such as Lombardian or veterinarian. The second point of comparison was between referential uses (viz. ‘quello stronzo/quel lombardo di Marco’; ‘that jerk/Lombardian Marco’) and predicative uses (viz. ‘Marco è stronzo/lombardo’; ‘Marco is a jerk/Lombardian’). The third point of comparison was between supporting and neutral contexts; that is to say, contexts that entail the content associated with the expression under consideration (e.g., it is part of the context that the target is a jerk, or Lombardian) and those that do not. What they found was that the acceptability ratings for expressives were much lower in neutral than in supporting contexts, to a greater extent than non-expressive terms. This difference in acceptability was particularly striking for referentially used expressives, but also quite significant for predicative uses, too. This led them to conclude that contrary to Claim 2, felicitous uses of negative expressives do impose certain contextual constraints.

Moreover, some earlier experimental studies on negative expressives engaged with certain aspects of Claim 1.Footnote 8 The first is Harris and Potts (Reference Harris and Potts2009), who decided to test the observation made in Amaral et al. (Reference Amaral, Roberts and Smith2007), contra Potts (2005), that expressives do not always reflect the speaker’s perspective. Harris and Potts (Reference Harris and Potts2009) presented the participants with two-sentence sequences, where the first sentence varied across four conditions, and the second contained a negative expressive in an anaphoric definite description (such as the jerk). Here is a sample item:

Suppose you and I are talking and I say:

-

A. My classmate Sheila said that her history professor gave her a low grade.

-

B. My classmate Sheila said that her history professor gave her a really low grade.

-

C. My classmate Sheila said that her history professor gave her a high grade.

-

D. My classmate Sheila said that her history professor gave her a really high grade.

Target sentence: The jerk always favors long papers.

The participants were then asked ‘Whose view is it that the professor is a jerk?’ and could choose between: ‘Mine (Speaker); Sheila’s (Subject); Mine and Sheila’s’. Harris and Potts found that the Speaker choice was preferred across conditions; it was highly preferred (88%) in conditions C and D, while in conditions B and C, it reached 54%, against 17% Subject responses and 29% Speaker-and-Subject responses. Based on this, they noted that ‘non-speaker-oriented readings are possible for expressives, if the right contextual factors are present’ and that ‘such readings do not require syntactic embedding’ (Harris & Potts Reference Harris and Potts2009: 20). Subsequent experimental studies in Kaiser (Reference Kaiser2015) replicated some of these findings, but also introduced a new task, in which participants were asked to resolve a potentially ambiguous pronoun. Kaiser compared two conditions, only one of which included an expressive. Here is a sample item:

-

A. Arthur hollered at Eric at the restaurant. He did not care about using foul language in a room full of people.

-

B. Arthur hollered at Eric at the restaurant. That ignorant jerk; he did not care about using foul language in a room full of people.

Participants were then asked ‘Who didn’t care about using foul language?’ and were given a 6-point scale ranging from ‘Definitely Arthur’ (subject) to ‘Definitely Eric’ (object). Kaiser found that while in the A condition the pronoun was, as expected, ambiguous, in the B condition, ‘participants [were] more likely to interpret the pronoun as referring to the preceding object (a sign of them having shifted to the perspective of the preceding subject)’ (Kaiser Reference Kaiser2015: 365). Consequently, this study provides further evidence that the content of expressives like jerk does not always reflect the speaker’s attitudes, but sometimes reflects those of some salient agent.

Importantly for our purposes, both Harris and Potts (Reference Harris and Potts2009) and Kaiser (Reference Kaiser2015) only challenge the assumption of speaker-orientedness, or what Gutzmann (Reference Gutzmann2019) calls ‘speaker linking’ – which, to be sure, was endorsed in Potts (2005), Schlenker (Reference Schlenker2007) and Tonhauser et al. (Reference Tonhauser, Beaver, Roberts and Simons2013) –, but not the deeper assumption of agent-orientedness that we take Claim 1 to state. That is to say, in the alternative interpretations of expressives that their studies bring to light, the content of expressives is still attitudinal and agent-oriented: it reflects the negative attitudes of an agent toward the target of the expressive, even though the agent is different from the speaker. Our own aim is to address Claim 1 in a more direct way. We want to ask whether the content of expressives is attitudinal at all (regardless of whose attitudes are relevant on a given occasion of use); the alternative proposal being that the content of an expressive is not (only) about someone’s attitudes, but also about the target of the expressive.

This proposal is also motivated by theoretical reasons, and more specifically, the idea, due to McCready (2010) and Gutzmann (Reference Gutzmann2015), that epithets such as ‘jerk’ are mixed expressives, and as such, have a double communicative function, conveying both descriptive content and an expressive evaluation. The intuition that such expressions have a descriptive component is particularly strong when these terms are used in predicative (‘N is a jerk’) rather than in nominal (‘That jerk N VP’) positions. We have therefore decided to test this intuition on empirical grounds.

In order to assess Claim 1 from an experimental point of view, we have conducted two studies. The first one is a rating task, in which we asked participants to rate sentences including negative expressives for acceptability, on a 1-to-5 Likert scale. Taking inspiration from Tonhauser et al (Reference Tonhauser, Beaver, Roberts and Simons2013) and from the study in Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic (Reference Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic2021), we have manipulated the context parameter between supporting and neutral contexts.

However, within the range of supporting contexts, we have compared five conditions. Three of those correspond to the idea that underlies Claim 1, namely, that the content of negative expressives is attitudinal and agent-oriented. Of those three, one condition was that the content of jerk reflects the speaker’s negative attitudes toward the target, as predicted by the influential view of expressives. Since Harris and Potts (Reference Harris and Potts2009) found that expressives can acquire non-speaker-oriented interpretations and reflect a perspective that is not necessarily that of the speaker but also of other relevant subjects, we have translated this prediction in two ‘intersubjective’ conditions: one that reflects a negative attitude toward the target that is shared between the speaker and the hearer (s), and another that reflects such a negative attitude shared between the speaker, the hearer and other people involved in the conversation. We call the first, ‘agent-oriented’ and the second and third, ‘intersubjective 1 & 2’. Crucially, the fourth supporting context condition was not about anyone’s attitudes, but about the target of the expressive. For that purpose, the context was described as one in which the target ‘must have done something bad’. Additionally, in a neutral context condition, we have compared negative expressives with both positively valenced and negatively valenced controller expressions, such as nice (simpatico in Italian) and unpleasant (sgradevole). As we shall shortly see in much greater detail, our results replicate the finding in Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic (Reference Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic2021) that negative expressives are significantly less acceptable in neutral than in supporting contexts. But in addition, the results also show that expressives are significantly less acceptable in the three agent-oriented conditions (with no further differences among the speaker-oriented and the two intersubjective conditions) than in the target-oriented condition. This result, we believe, calls into question the assumption widely shared in the existing accounts of expressives to the effect that their content is generally attitudinal and agent-oriented. Note, though, that, unlike Harris and Potts (Reference Harris and Potts2009) or Kaiser (Reference Kaiser2015), we were not interested in comparing agent-oriented conditions in which the agent is the speaker versus somebody else.

The motivation behind our second experimental study was to try to see how participants interpret negative expressives. We presented them with a selection task, in which they would see a sentence containing a negative expressive and were asked what the speaker meant, with the possibility of choosing among four options. As in the previous task, there were three agent-oriented options (namely speaker, speaker-and-hearer, speaker-hearer-and-others) and a target-oriented option. And once more, we used positively and negatively valenced expressions (nice, unpleasant) as controllers. As we shall shortly see, there was a significant preference for the target-oriented interpretation over the speaker-oriented interpretation (the two intersubjective interpretations, on the other hand, were largely discarded).

A final introductory remark is in order. Recall that most scholars focus on the referential uses of expressives, i.e., expressives occurring in constructions like that jerk. Even if predicative uses of expressives have received some attention, notably in Beller (Reference Beller2013), Gutzmann (Reference Gutzmann2019), Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic (Reference Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic2021) and Carranza Pinedo (Reference Carranza Pinedo2022), they are still marginal with respect to the referential uses. Contrary to the existing tendency, we believe that referential constructions are not the ideal case at which to look. The reason is that it is very hard to disentangle the content associated with the expressive itself from whatever content is triggered by the complex demonstrative construction that F. Footnote 9 This is why we have decided to turn to predicative uses. Hence, while we acknowledge that the assumption of agent-orientedness has been primarily endorsed with respect to referential uses of expressives, our focus in this paper is on whether it applies to their predicative uses.

3. Experiment 1 – The Rating Task

3.1 Methods

Participants

219 participants took part in the study [MA = 31.01; SD = 12.51; 156f; 63 m]. Participants were all native Italian speakers. The experiment was administered online. Informed consent was obtained from every participant.Footnote 10

Stimuli

In this study, we adopted Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic’s (Reference Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic2021) design, consisting of eight written vignettes in Italian composed of a context scenario and a target sentence of the form ‘X is P’ where X was the target individual while P was the negative expressive stronzo (jerk in English). We also included 18 filler items: nine positively valenced and nine negatively valenced non-expressive fillers.Footnote 11

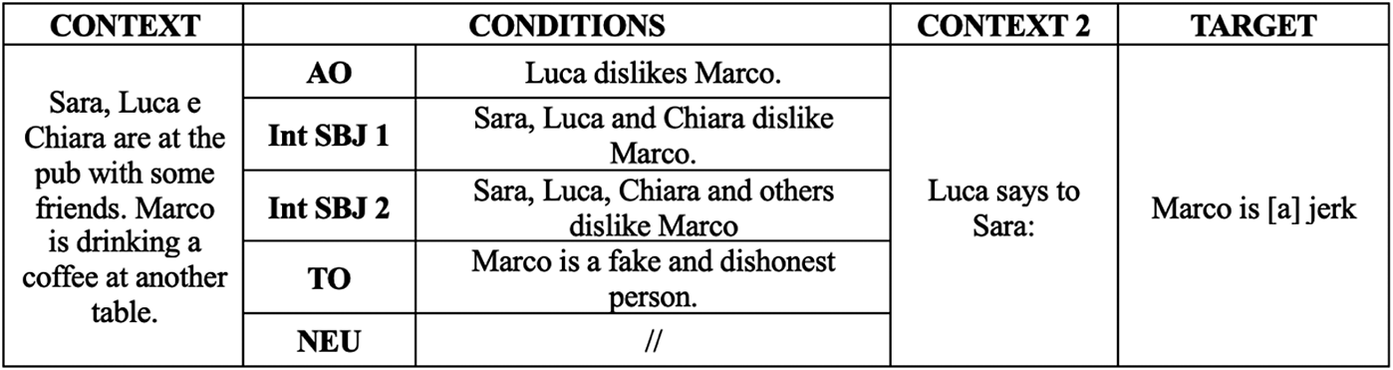

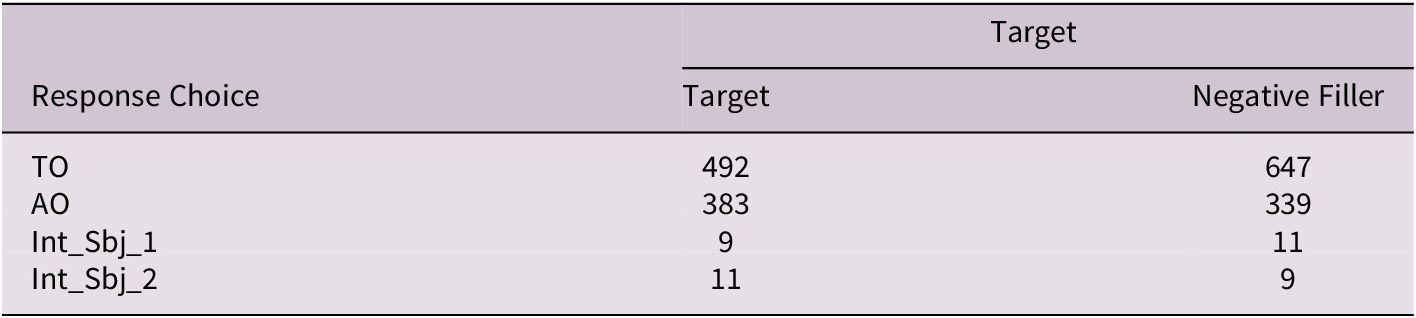

The context sentence was manipulated in order to generate five conditions – see Fig. 1. In the agent-oriented condition (AO) participants were given the information that the speaker uttering the expressive had a negative attitude toward the target individual. In the first intersubjective condition (Int_SBJ_1), the context sentence provided the information that both the speaker and their interlocutors had a negative attitude toward the target individual, while in the second intersubjective condition (Int_SBJ_2), this negative attitude was shared by yet other unspecified persons. The target-oriented condition (TO) was generated by a context scenario providing the information that the target individual must have done something bad. Finally, we included a neutral condition (NEU) that provided no information regarding the use of the expressive. Filler items (both positive and negative fillers) were presented in neutral conditions only, i.e., in non-supporting contexts.

Figure 1. Example of a target item (Engl. Tr.) with the context sentences generating the five experimental conditions.

Procedure

The procedure consisted of reading the context scenarios. Participants were then asked to rate on a 1-to-5 point Likert scale (1 unacceptable; 5 completely acceptable) the degree of acceptability of the target sentence as uttered by a fictional speaker, and of the positive and negative fillers in the five experimental conditions. Specifically, the question was: ‘How acceptable do you consider S’s [the fictional utterer] utterance?’ Hence, the task consisted of a comprehension task where participants assessed the fictional speaker’s utterance as receivers. The rationale was to explore which contextual condition best supported the utterance of the target sentence containing the negative expressive.

3.2 Results

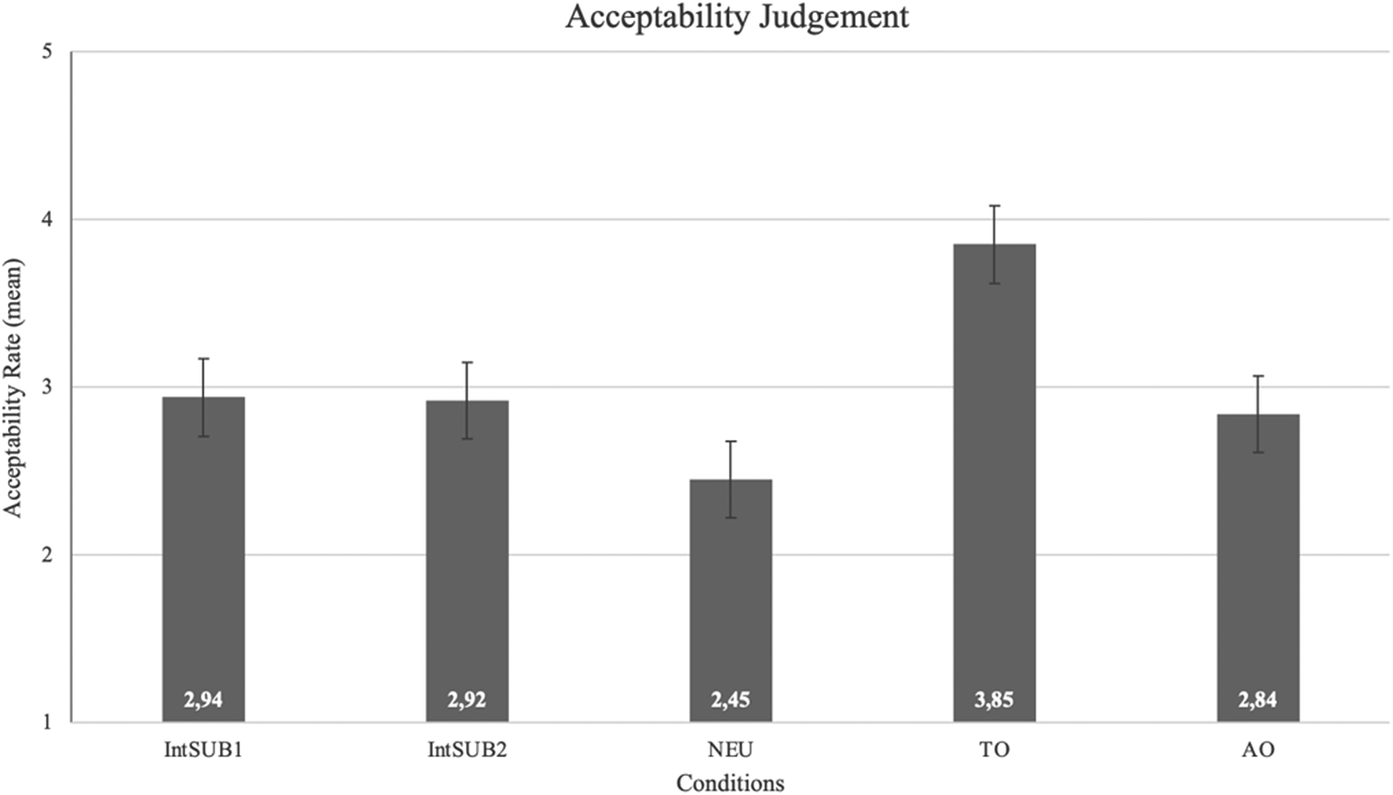

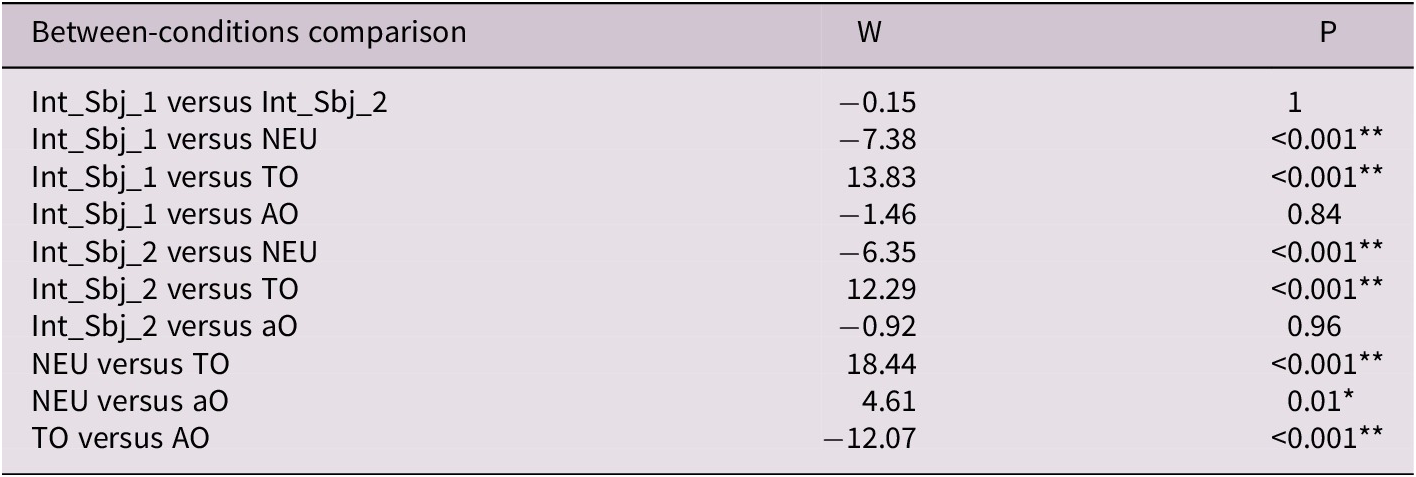

Figure 2 shows the mean acceptability rate for each of the five experimental conditions. A non-parametric Kruskall–Wallis test was conducted to examine the differences in participants’ acceptability judgments regarding the target sentences according to experimental conditions. This analysis revealed a significant effect of condition (χ2(4) = 180; p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons between conditions were conducted using the Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Fligner (DSCF) method. Most importantly, this analysis revealed that participants judged as significantly more acceptable the target sentences containing the target expression when these were presented in condition TO than in conditions Int_Sbj_1 (W = 13.83; p < 0.001), Int_Sbj_2 (W = 12.29; p < 0.001), NEU (W = 18.44; p < 0.001) and AO (W = –12.07; p < 0.001). Additionally, the target sentences were judged as significantly less acceptable when these were presented in condition NEU than in conditions Int_Sbj_1 (W = –7.38; p < 0.001), Int_Sbj_2 (W = –6.35; p < 0.001) and AO (W = 4.61; p = 0.01) – see Table 1 for the results of all pairwise comparisons.

Figure 2. Mean acceptability rate for each of the five experimental conditions.

Table 1. Results of the Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Fligner pairwise comparisons for participants’ acceptability rate of the target sentences between conditions

A second set of statistical analyses was conducted to explore potential differences in participants’ acceptability judgments regarding the target sentences in the neutral condition and the positive and negative filler sentences – see Figure 3 for the mean acceptability rates in the three conditions. A Kruskall–Wallis test revealed a significant effect of condition (χ2(2) = 134; p < 0.001). DSCF pairwise comparisons revealed that filler sentences were significantly more acceptable in the positive than in the negative condition (W = 9.72; p < 0.001). Most importantly, participants judged as less acceptable the target sentences in the neutral condition as compared to both the positive (W = 16.05; p < 0.001) and the negative (W = –7.17; p < 0.001) filler items.

Figure 3. Mean acceptability rates of the target item in neutral condition (NEU), negative fillers and positive.

3.3 Discussion

Study 1 replicates some of the findings of Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic (Reference Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic2021) and reveals further interesting results. In line with those previous studies, we found that sentences containing the expressive stronzo are deemed more acceptable in all supporting contexts (target-oriented, speaker-oriented and the two intersubjective ones) than in the neutral one (that is, the context that contains no information on what kind of person Marco is or how other people think of him). We also found that in the neutral condition, the acceptability of target sentences is significantly lower than that of fillers. Note that we also replicated the result of the follow-up study from Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic (Reference Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic2021): we found, as they did, that sentences containing negative non-expressive terms (like hateful or rude) are significantly more acceptable than those containing stronzo in neutral contexts.

Note however that those previous studies employed positive, negative and non-valenced terms as fillers, without distinguishing among them. Instead, we split fillers into positively and negatively valenced ones, which allowed us to see that in the neutral condition, all the differences between expressives, negative fillers (like ‘hateful’ or ‘rude’) and positive fillers (like ‘kind’ and ‘wise’) were significant: target sentences containing stronzo were significantly less acceptable than those containing negative fillers, which, in turn, were significantly less acceptable than those containing positive fillers.

Most importantly, Study 1 sheds new light on the content associated with expressives, on which previous acceptability studies did not provide any insights: our experiment reveals that the TO is the one that is judged significantly more acceptable, compared to the AO one and the two intersubjective ones. No significant difference was found between the AO and each of the intersubjective conditions, nor between the two intersubjective conditions.

4. Experiment 2 – The Selection Task

4.1 Methods

Participants

112 participants took part in the study [MA = 23.74; SD = 8.63; 90f; 22 m]. Participants were all native Italian speakers. The experiment was administered online. Informed consent was obtained from every participant.

Stimuli and procedure

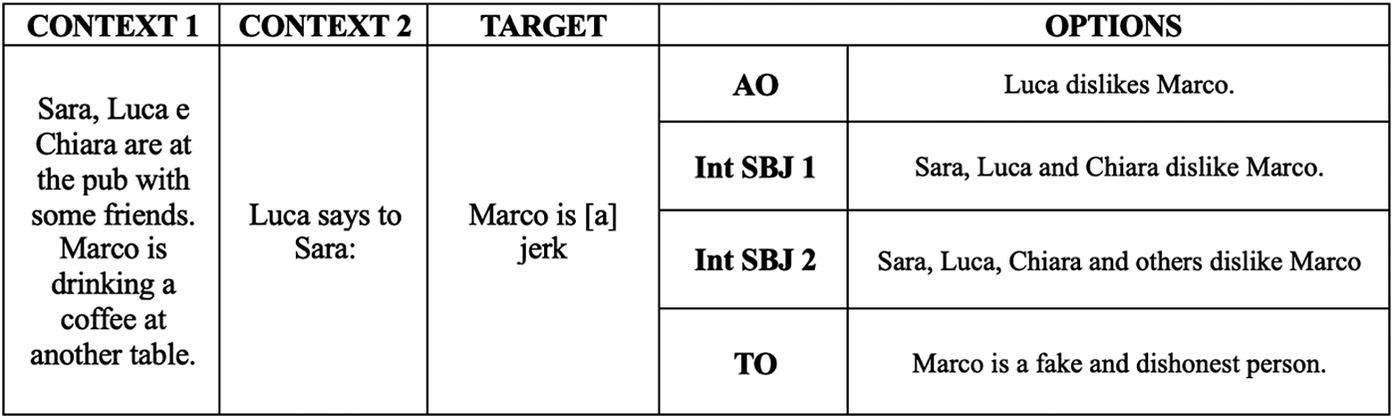

We used the stimuli of Experiment 1 to create eight written vignettes (randomly presented). In this study, however, each vignette was a story composed of a context scenario consisting of one sentence, followed by a target sentence. The context scenario described a circumstance in which two or more people are having a conversation about a target person. The target sentence is an utterance made by one of the two interlocutors about the target person. The utterance was a predicative sentence of the form ‘X is P’ where X was the target person while P was the negative expressive stronzo. 18 filler items were included: nine positive filler scenarios in which the target sentence P included a positively valenced predicate ascribed to X (e.g., simpatico/nice); in the other nine filler scenarios, P was a non-expressive negatively valenced predicate (e.g., sgradevole/unpleasant). The context sentence generated a neutral context that provided no information supporting the target sentence; see Figure 4.

Figure 4. Example of a target item (Engl. Tr.) with the context sentences, the target sentence and the four options of the selection task.

The procedure consisted in reading the context scenario and the target sentence. After that, participants were asked to perform a selection task by selecting one out of four possible alternative paraphrases of the target sentence containing the negative expressive. The question that the participants were given was about the speaker’s intended meaning, namely, ‘What does [the speaker] mean to say?’ (It. transl. ‘Che cosa [il parlante] intende dire?’). The first paraphrase corresponded to the agent-oriented reading (AO) according to which the speaker uttering the expressive had a negative attitude toward the target person (e.g., Luca odia Marco/Luca hates Marco). The second and the third options expressed the two intersubjective readings (Int_Sbj_1 and Int_Sbj_2) according to which the target sentence conveys the information that, respectively, the speaker and their interlocutors, or the speaker, their interlocutors and other unspecified persons have a negative attitude toward the target person. Finally, the fourth option paraphrased the target-oriented reading (TO) according to which the negative expressive expresses the information that the target person must have done something bad. The order of presentation of the options was randomized.

4.2 Results

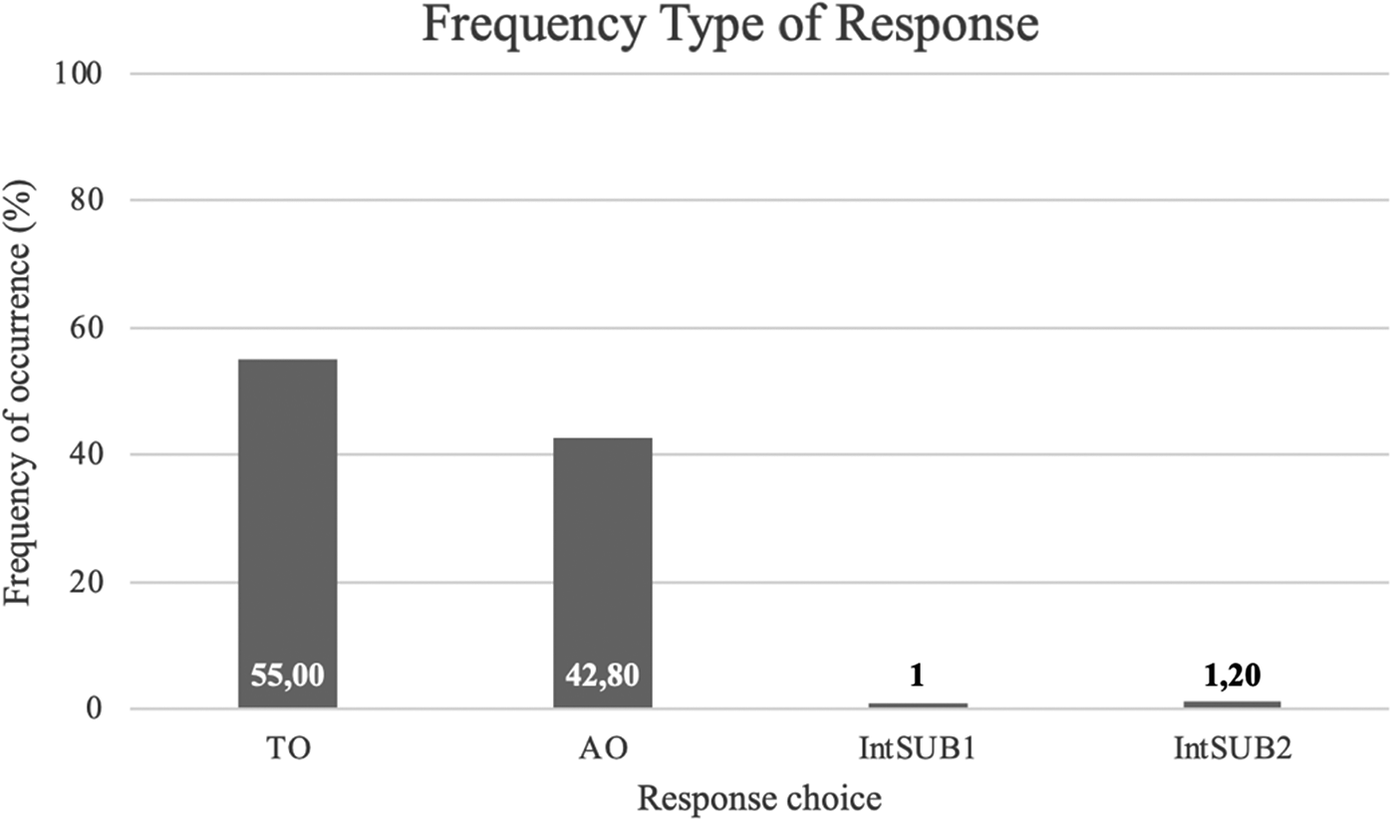

Figure 5 illustrates the frequency of occurrences for each response choice. To check for any significant differences in the distribution of participants’ response choices, two statistical analyses were performed. First, a chi-squared goodness of fit test, comparing the observed frequency for each response type to the expected frequency (i.e., 0.25 for each response type), was used to analyze the distribution of participants’ response types in the dataset. Afterward, two-sided Z-tests with continuity correction were conducted for an analysis of the proportion between response types.

Figure 5. Frequency of occurrences for each response choice in the selection task: Agent-Oriented option (AO), Target-Oriented option (TO), Intersubjective option 2 (Int_Sbj_2) and Intersubjective option 1 (Int_Sbj_1).

The chi-squared statistics revealed that the four types of response choices were not equally distributed in the dataset, since the observed frequency significantly differed from the expected frequency (χ2(3) = 843.35; p < 0.0001). The Z-test statistics provided more details on the differences in the distribution among the four response types. In fact, while the proportion of choices did not significantly differ between the Int_Sbj_1 and Int_Sbj_2 condition (χ2(1) = 0.05; p = 0.82), this was significantly different in all other comparisons: Int_Sbj_1 versus TO (χ2(1) = 643.96; p < 0.0001); Int_Sbj_1 versus AO (χ2(1) = 454.44; p < 0.0001); Int_Sbj_2 versus TO (χ2(1) = 637.07; p < 0.0001); Int_Sbj_2 versus AO (χ2(1) = 447.94; p < 0.0001); and TO versus AO (χ2(1) = 26.07; p < 0.0001).

Filler analyses

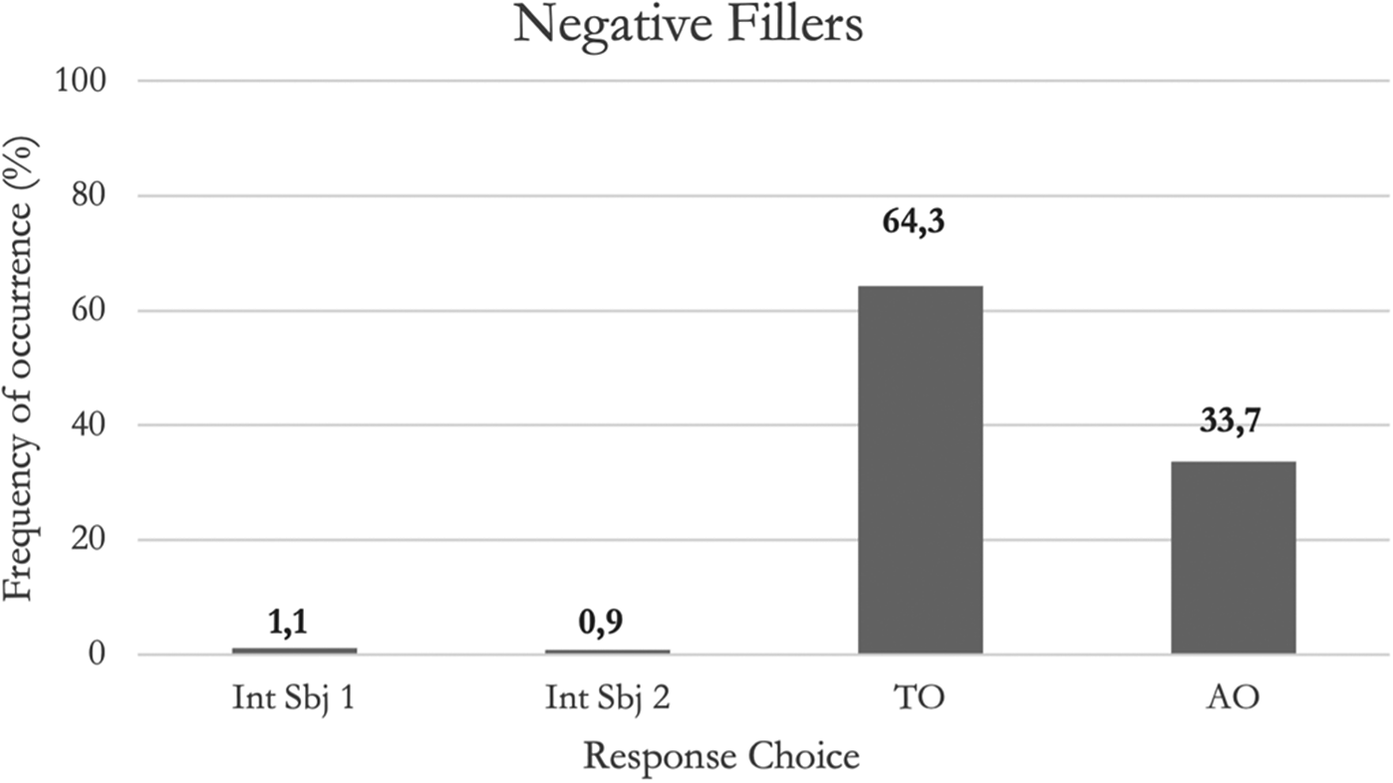

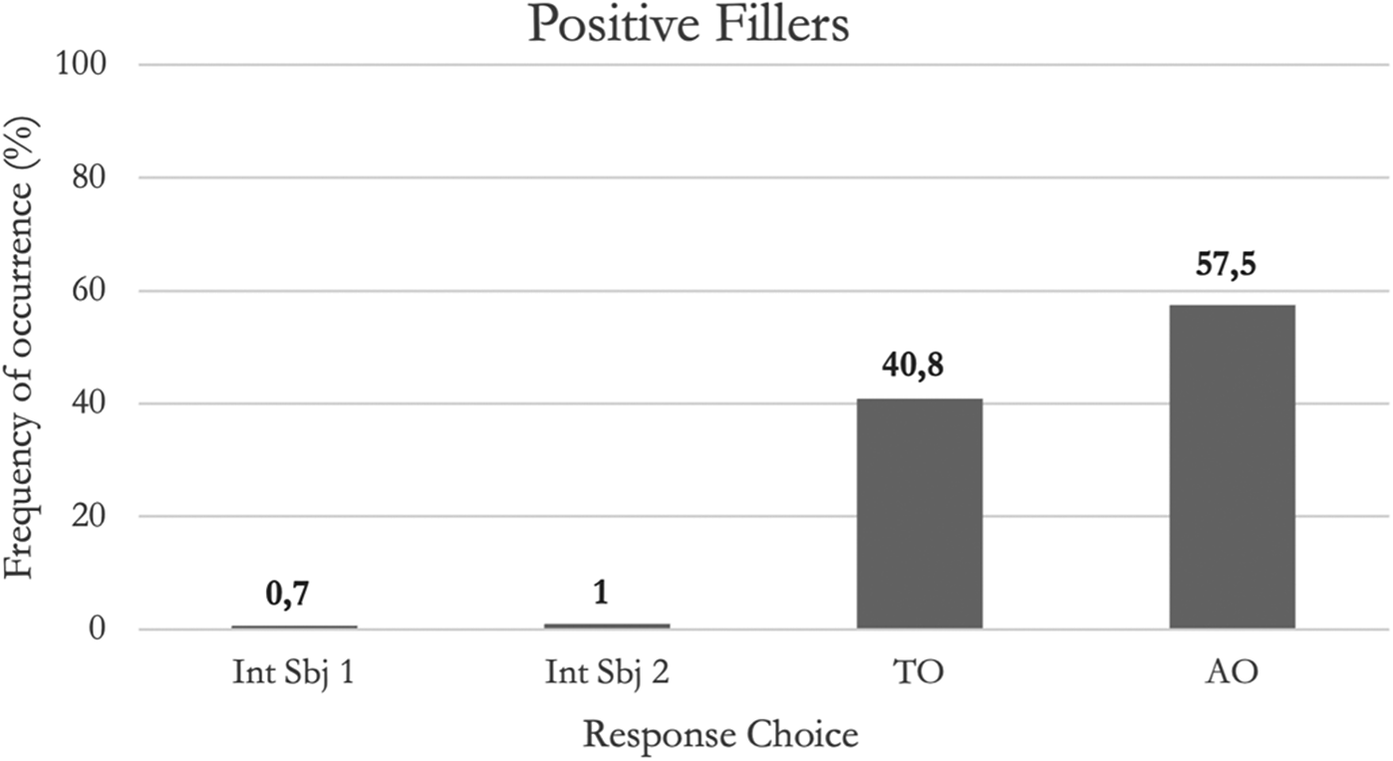

Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the frequency of occurrences for each response choice in negative and positive filler stories, respectively. To check for any significant differences in the distribution of participants’ response choices, two statistical analyses were performed for each of the filler story types (i.e., negative filler stories and positive filler stories). First, a chi-squared goodness of fit test, comparing the observed frequency for each response type to the expected frequency (i.e., 0.25 for each response type), was used to analyze the distribution of participants’ response types in the selected dataset. Afterward, two-sided Z-tests with continuity correction were conducted for an analysis of the proportion between response types.

Figure 6. Frequency of occurrences for each response choice with the negative fillers.

Figure 7. Frequency of occurrences for each response choice with the positive fillers.

Negative filler stories

The chi-squared statistics revealed that the four types of response choices were not equally distributed in the dataset for the negative filler stories, since the observed frequency significantly differed from the expected frequency (χ2(3) = 1116.2; p < 0.0001). The Z-test statistics provided more details on differences in the distribution among the four response types. In fact, while the proportion of choices did not significantly differ between the Int_Sbj_1 and Int_Sbj_2 condition (χ2(1) = 0.05; p = 0.82), this was significantly different in all other comparisons: Int_Sbj_1 versus TO (χ2(1) = 910.61; p < 0.0001); Int_Sbj_1 versus AO (χ2(1) = 369.85; p < 0.0001); Int_Sbj_2 versus TO (χ2(1) = 917.79; p < 0.0001); Int_Sbj_2 versus AO (χ2(1) = 376.09; p < 0.0001); and TO versus AO (χ2(1) = 187.54; p < 0.0001).

Positive filler stories

The chi-squared statistics revealed that the four types of response choices were not equally distributed in the dataset for the positive filler stories, since the observed frequency significantly differed from the expected frequency (χ2(3) = 997.83; p < 0.0001). The Z-test statistics provided more similar patterns of results as for the negative filler stories. The proportion of choices did not significantly differ between the Int_Sbj_1 and Int_Sbj_2 condition (χ2(1) = 0.23; p = 0.62); and this significantly differed across all other comparisons: Int_Sbj_1 versus TO (χ2(1) = 690.17; p < 0.0001); Int_Sbj_1 versus AO (χ2(1) = 786.34; p < 0.0001); Int_Sbj_2 versus TO (χ2(1) = 480.36; p < 0.0001); Int_Sbj_2 versus AO (χ2(1) = 775.79; p < 0.0001); and TO versus AO (χ2(1) = 56.016; p < 0.0001).

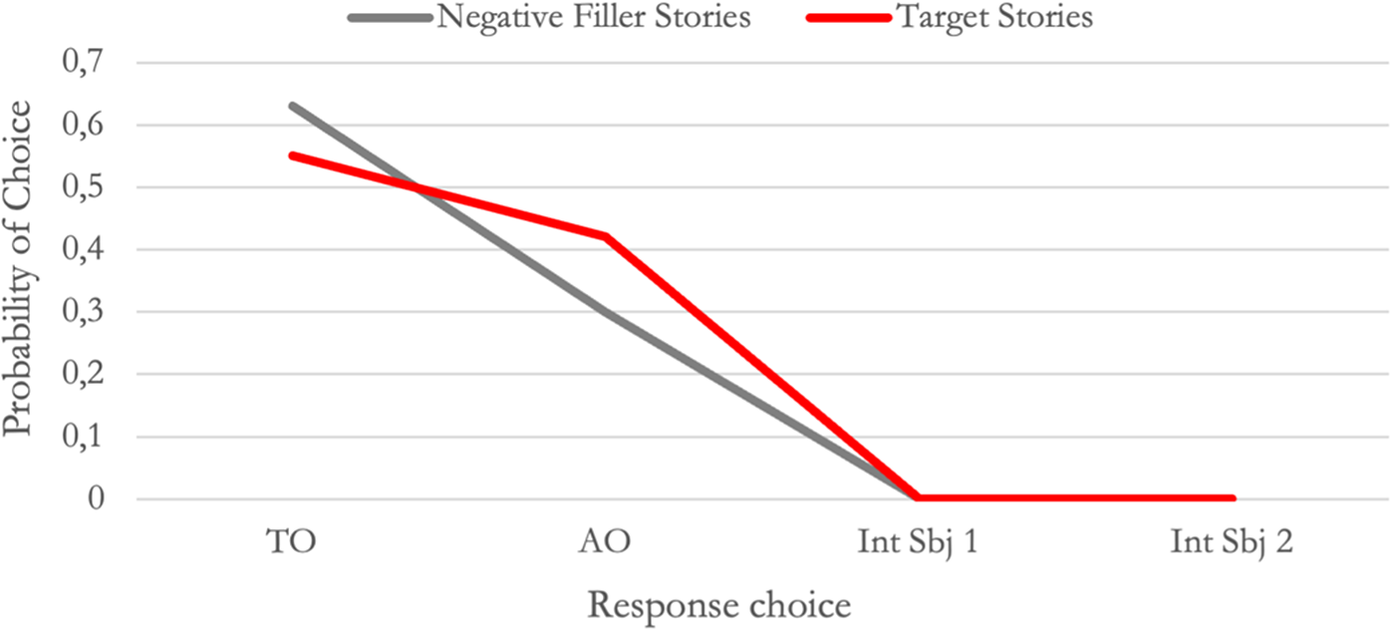

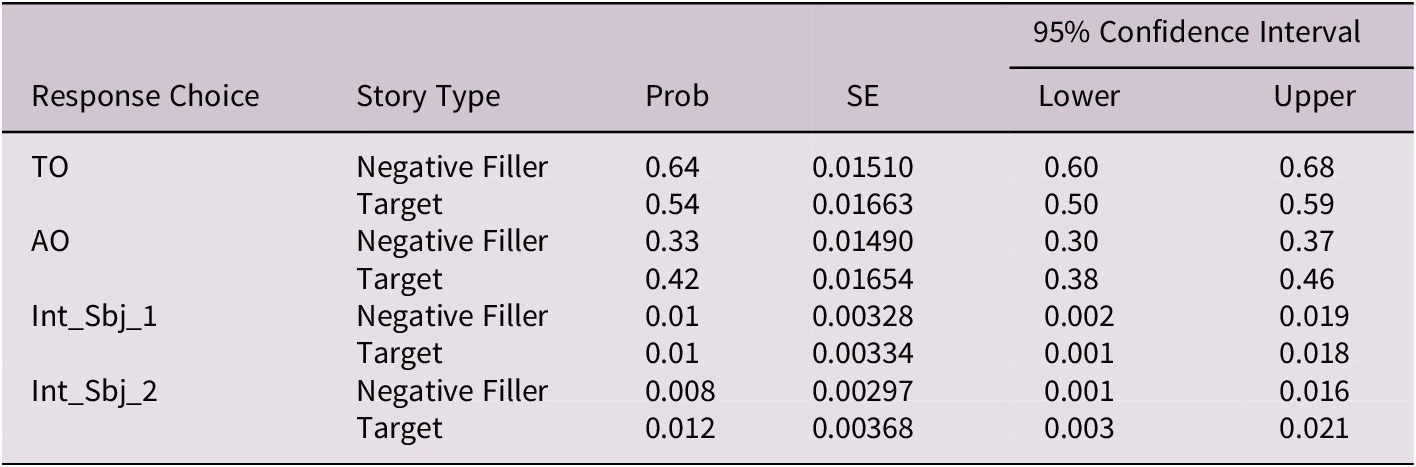

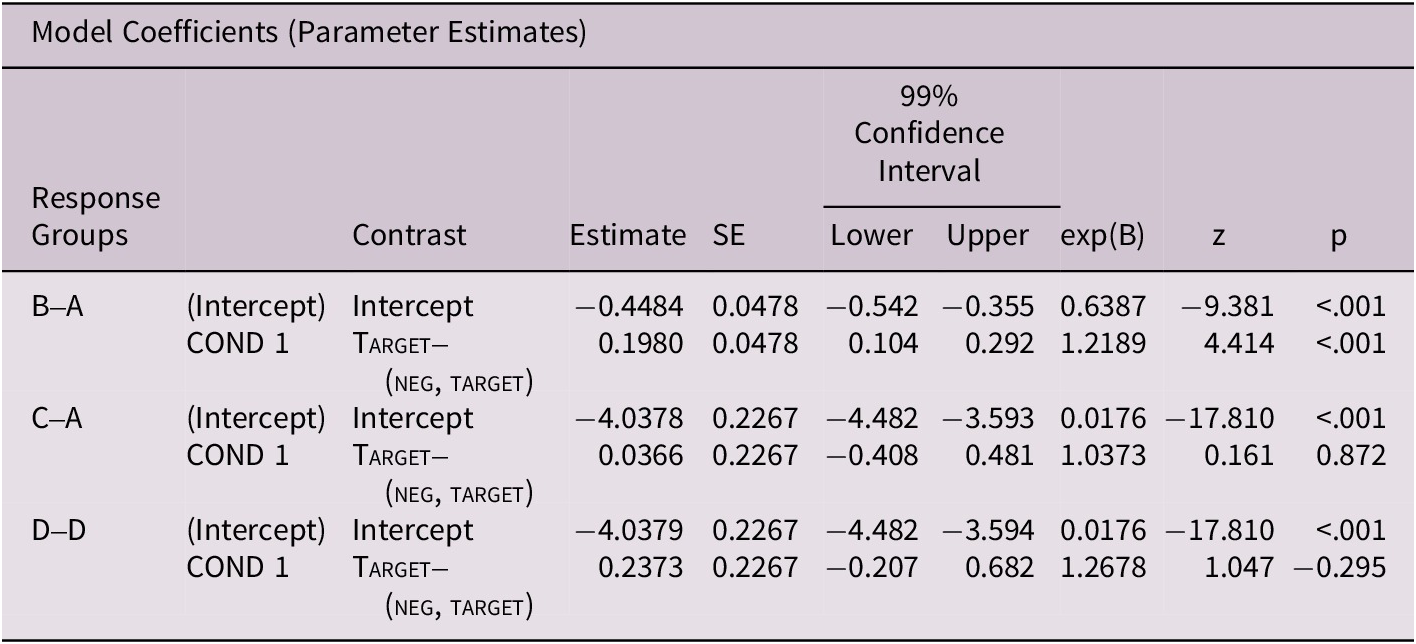

Probability of options choice in target stories and negative filler stories

Table 2 illustrates the frequency of occurrences of each of the four options choice in the target stories and the negative filler stories. To estimate whether the probability of choosing each of the four choices varies depending on story type, a Multinomial Generalized Linear Model (multinomial GLM) statistics with a logit link function was conducted. In this model, participants’ response choice in both story types was the 4-level categorical outcome variable and story type was the 2-level predictor variable (i.e., target versus negative filler)Footnote 12. The omnibus chi-squared test for these statistics revealed that the probability of choosing the available options was not the same between story types (χ2(3) = 17.8; p < 0.001). The details of the regression coefficients most importantly revealed that the probability of choosing the AO over the TO option in the target stories was 1.21 times higher than in the negative filler stories, and this effect was statistically significant (z = 4.14; p < 0.001) – Figure 8. All other contrasts were not significant – see Table 3 for the estimated marginal means of the probability of response choices between story types and Table 4 for details of the regression coefficients.

Figure 8. Probability of choosing each of the four choices depending on story type, i.e., target stories versus negative filler stories.

Table 2. Frequency of occurrences of option choices TO, AO, Int_Sbj_1 and Int_Sbj_2 in target and negative filler stories

Table 3. Estimated marginal means of the probability of response choice in negative filler and target stories

Table 4. Details of model coefficients for the Multinomial GLM. Response Groups: A = TO; B = AO; C=Int_Sbj_1; D=Int_Sbj_2. Contrasts Coding, Groups to levels: 1 = negative fillers; 2 = target

In addition, to further explore the differences in the distribution of each response choice in the two-story types under scrutiny, a post-hoc analysis comparing the frequency of each choice between story types with Bonferroni correction was run. This analysis corroborated the pattern that emerged in the multinomial GLM, and revealed that only the distribution of choices TO and AO significantly differed between story types: in the target stories, the probability of choosing option AO was significantly higher than in the filler stories (z = 4.15; SE = 0.02247; PBonferroni < 0.001), and the probability of choosing option TO was significantly lower than in the filler stories (z = −4.08; SE = 0.02226; PBonferroni < 0.001). No significant differences between story types emerged for the remaining two option choices (Int_Sbj_1: z = 0.18; SE = 0.00468; PBonferroni = 0.85; Int_Sbj_2: z = −0.70; SE = 0.00473; PBonferroni = 0.50).

4.3 Discussion

Study 2 investigates what is the most adequate paraphrase of the content associated with stronzo. It reveals that the TO is the one that is most frequently chosen as the best paraphrase of the expressive. While the AO option was often chosen (even if to a lesser extent than the target-oriented option), the two Intersubjective (Int_Sbj_1, Int_Sbj_2) options were almost entirely dismissed. We observe a similar pattern for negative fillers: once again, the TO option was the most frequently chosen paraphrase, followed by the AO one, while the two intersubjective ones were almost entirely dismissed. Interestingly, positive fillers show an opposite pattern: the AO option was the most frequently selected, followed by the TO one; once again, though, the intersubjective options were hardly ever selected.

5. General Discussion

With the results of our studies at hand, let us go back to what we take to be an influential view of expressives and to its two core claims. Claim 1 holds that the content associated with expressives is attitudinal as well as agent-oriented and that it is furthermore typically speaker-oriented; that is to say, that expressives like jerk typically communicate how the speaker feels about the target. Suppose that Sofia says ‘That jerk Marco is talking’. The content associated with that jerk is that she feels negatively about Marco, regardless of what kind of person Marco is or how other people feel about him. Claim 2 holds that the use of expressives imposes no strong contextual felicity constraint. For Sofia’s utterance of the sentence ‘That jerk Marco is talking’ to be felicitous, there should be an individual (Marco) for the complex demonstrative to refer to; the context need not provide any information as to whether the target is to be held in low opinion or whether the speaker (or, for that matter, anyone else) feels negatively about the target.

Both claims have gone unquestioned for a long time, and it is only recently that they have started to be investigated from a more empirical angle. Several experimental studies (Harris and Potts Reference Harris and Potts2009, Harris Reference Harris2012, Kaiser Reference Kaiser2015) aimed to engage with Claim 1. However, the focus of those studies was the question whether the attitudinal content associated with negative expressives was always anchored to the speaker or could instead be anchored to someone else (a further question being what triggered such perspectival shifts). None of those studies questioned the assumption that the content is attitudinal in the first place. The studies in Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic (Reference Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic2021) aimed to engage with Claim 2, and showed that, contrary to the influential view, negative expressives such as stronzo do impose certain constraints on the context in order for their use to be deemed acceptable. In sections 5.1 and 5.2, we will explain why the studies that we are reporting here may be seen as providing evidence against both claims. In sections 5.3, 5.4 and 5.5, however, we will outline possible explanations of the obtained results that remain compatible with the influential view. Which among the possible explanations are the most plausible is a question that we must leave for future research.

5.1 Challenge to Claim 1

Both of our studies provide evidence that seems to speak against Claim 1, assuming that the claim is taken to hold for expressive terms such as ‘jerk’ and not only for pure expressives such as ‘ouch’ or ‘damn’. Study 1 shows that the use of stronzo (in predicative constructions) is significantly more acceptable in the target-oriented condition than in any other condition. (Additionally, they show that it is also significantly more acceptable in the speaker-oriented condition or the two intersubjective conditions than in the neutral condition.) In other words, it is more acceptable to call someone a jerk when it is common ground that they have behaved in a bad way, rather than when it is common ground that the speaker feels negatively about them, or even the speaker and their interlocutors. This seems to be in tension with Claim 1, according to which the agent-oriented option should be expected to yield the highest acceptability results. Furthermore, Study 2 shows that the target-oriented paraphrase was the most often selected one, significantly more often than any other. Again, this is in tension with Claim 1, according to which the content associated with stronzo is attitudinal and agent-oriented. This being said, let us note that the agent-oriented condition makes the use of stronzo relatively acceptable, and definitely more so than the neutral condition (Study 1), and that a significant number of participants preferred the agent-oriented paraphrase to the target-oriented one (Study 2).

This suggests that, when used in a predicative position, an expressive noun like ‘jerk’ is mainly interpreted as having the communicative function of informing the audience about some negative features of the person for whom the expressive is used. This consolidates the idea, defended first in McCready (2010) and then in Gutzmann (Reference Gutzmann2015), that such nouns are not solely expressive, but also encode some descriptive content – that is, the idea that nouns like ‘jerk’ are mixed expressives. Importantly, note that this target-oriented interpretation is still evaluative in nature; but while the agent-oriented reading is about the agent’s feelings, the target-oriented interpretation is about the target’s properties. This evidence suggests that these expressive nouns carry a two-fold semantic contribution: a predication about a certain target individual as well as an evaluative content. In this sense, this result partly corroborates the intuition that some categories of expressive terms can, in certain syntactic environments, have a mixed behavior, conveying both descriptive and evaluative contents.

To be sure, if one gives up Claim 1, then the question becomes what kind of non-attitudinal or non-agent-oriented content is associated with negative expressives. Some recent proposals such as Beller (Reference Beller2013) or Carranza Pinedo (Reference Carranza Pinedo2022) point to a promising direction. However, it is beyond the scope of our paper to examine in detail whether their predictions are completely in line with the results of our studies.

5.2 Challenge to Claim 2

Study 1 replicates some of the main results from Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic (Reference Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic2021), showing that stronzo is the least acceptable in the neutral condition. In other words, when the context leaves it open what kind of person the target of the expressive is or how the speaker or the other conversation participants feel about them, calling them ‘a jerk’ is hardly deemed acceptable. The acceptability rises significantly in all the other conditions, suggesting that, pace the influential view, stronzo does impose something akin to a strong contextual felicity constraint.

We see that target sentences that contain the expressive stronzo are significantly less acceptable than those that contain negative control items (e.g., hateful), which, in turn, are significantly less acceptable than those that contain positive control items (e.g., kind). This means that, in the absence of supporting information, saying something negative is in general deemed less acceptable than saying something positive. This feature of negative terms, however, is not enough to account for the contextual constraint imposed by stronzo, since expressives such as jerk are judged to be significantly less acceptable than non-expressive negative terms such as hateful.

While our results suggest that there may be some correlation between saying something negative and being interpreted as conveying something about what the target is like (and conversely, between saying something positive and being interpreted as expressing one’s attitude toward the target), they do not point to a simplistic picture according to which the more something is deemed acceptable, the more it will elicit an agent-oriented interpretation, and the more it is deemed unacceptable, the more it will receive a target-oriented interpretation. The data turn out to be more complicated than that. Even if both expressives and non-expressive negative terms reveal a preference for the target-oriented reading, this preference is stronger for non-expressive negative terms, which, on the other hand, turn out to receive higher acceptability rates than expressives. In other words, acceptability does not align neatly with a preference for an agent-oriented interpretation.

5.3 Disentangling the descriptive and the expressive dimensions

We have been careful enough to present the results of our studies as merely a challenge to the influential view, rather than direct evidence against it. While we believe that it is worth exploring alternatives to it, let us briefly sketch, in this and the next two sections, three ways in which the influential view may try to accommodate our results.

The first and most immediate way of defending the influential view is to acknowledge its limitations. Claims 1 and 2, or so the idea goes, hold for pure expressives such as ‘damn’, but when it comes to mixed expressives such as ‘jerk’ (as well as, arguably, slurs) these core claims only hold for the expressive content carried by such terms, but not for its descriptive content.Footnote 13 This is, in a nutshell, the proposal advanced in McCready (2010) and Gutzmann (Reference Gutzmann2015); see also Beltrama and Lee (Reference Beltrama and Lee2014) for discussion. What our studies additionally show is that the descriptive dimension appears to be the most salient one whenever such mixed expressives are used in a predicative position.

Even if the steady and successful development of theories of mixed expressives points toward a promising direction, two points are worth stressing. First, to the same extent that this line of reply may be seen as a refinement of the influential view, it is also a significant departure from the early versions of it, in particular Potts (2005), which did not leave room for expressions that simultaneously operate on the expressive and the at-issue level. Second, the philosophical literature on thick moral terms such as ‘cruel’, which similarly appear to convey a descriptive content (namely willfully causing pain or suffering to others without feeling any concern) and an evaluative content (namely a negative moral judgment about cruelty) has made it blatant that disentangling the two dimensions is far from a trivial matter (for discussion, see, among many others, Cepollaro and Stojanovic Reference Cepollaro and Stojanovic2016, Väyrynen Reference Väyrynen2016, Roberts Reference Roberts, McPherson and Plunkett2018, Willemsen and Reuter Reference Willemsen and Reuter2021). Hence a view that holds that the expressive content of ‘jerk’ is attitudinal and agent-oriented while its descriptive content is target-oriented, even if not overall implausible, would still require substantive development before being able to fully account for the data that our studies have delivered.

5.4 A pragmatic explanation

The second option takes inspiration from a more general stance toward experimental findings, the idea being that it is not always clear what it is to which the participants of a study are responding. We tried to design both of our studies in such a way that they would track the speakers’ intuitive understanding of the semantic content associated with negative expressives. However, it could be that participants are actually more responsive to some broader pragmatic considerations. Thinking along such lines, one could suggest that in our rating task, when participants are asked to judge the acceptability of various utterances in various contexts, they are less sensitive to grammatical acceptability than to a broader notion of acceptability that concerns not only what the speaker actually said, but also, why they said what they said. So, for example, when Sofia utters ‘That jerk Marco is talking’ in the neutral condition, since the context fails to provide any justification for Sofia to be calling Marco a jerk, participants may deem the utterance less acceptable than in the other conditions, in which they can find some such justification (namely, that she has negative feelings toward Marco, or that Marco has behaved badly). Similarly, the target-oriented condition provides stronger justification for her to call him a jerk than the agent-oriented condition does – or, for that matter, either of the two intersubjective conditions. The idea that the speaker has better reasons to use a negative expressive for the target in the target-oriented condition than in the others could, then, account for higher acceptability ratings in the target-oriented condition. In sum, one could argue that the results of Study 1 are compatible with the idea that the content associated with jerk is that the agent has a negative attitude toward the target, since the participants’ judgments may track acceptability in some broader, pragmatic sense.

As for Study 2, even though we formulated the task explicitly in terms of meaning (recall that participants were asked to select the best paraphrase of what the speaker means with her utterance), a defender of the influential view could suggest that here, too, participants’ judgments may be shaped by intuitions about so-called speaker meaning, rather than literal meaning. After all, it is widely agreed that ordinary speakers’ introspective knowledge about semantics is not perfect (or, at least, not transparent; see Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2020). So, once again, the participants’ preference for the target-oriented paraphrase over the agent-oriented paraphrase appears to be compatible with the idea that from a purely semantic point of view, the agent-oriented paraphrase is the correct one, since there can be other pragmatic factors that influence their responses.

5.5 A narrator-oriented explanation

The third option of accommodating our results into the influential view takes inspiration from previous empirical studies on negative expressives mentioned in section 2.2, that is, Harris and Potts (Reference Harris and Potts2009), Harris (Reference Harris2012) and Kaiser (Reference Kaiser2015). Recall that they showed that the attitudinal content associated with expressives need not always reflect the speaker’s attitudes, but can reflect some other salient agent’s attitudes. In particular, Kaiser (Reference Kaiser2015) argued that such shifted interpretations are prominent in certain linguistic environments in which there is a salient narrator, such as free indirect discourse (see also Stojanovic Reference Stojanovic, Maier and Stokke2021 for corpus-drawn examples and discussion). With this in mind, one could take the results of the rating task to merely replicate this previously observed phenomenon. The idea would be that what we call the target-oriented condition is, at the bottom, yet another agent-oriented condition, but the agent at stake is none of the characters mentioned in the context of the scenario; instead, it is the narrator (that is, the imaginary speaker who presents the task to the study participants).

We are generally sympathetic to the idea of using a familiar mechanism – in this case, that of perspectival shift – to account for newly observed results. Nevertheless, the strategy outlined on behalf of the influential view is not without major problems. First, in previous research on perspectival shift with expressives, there was always a clear figure of some agent (other than the speaker) to whom the attitudes encoded in the expressive content could be anchored. This is not the case here: it takes quite some effort and imagination to construct a ‘narrator figure’ when responding to the rating study. Second, the target-oriented condition is not (or at least, not explicitly) about anyone’s attitude. To suggest that a sentence such as ‘Marco is a fake and dishonest person’ has for its content that the speaker has a negative attitude toward Marco is a highly controversial claim.Footnote 14 Third, recall that the vignette of the rating task uses direct discourse reporting (rather than the indirect ‘said that…’ or free indirect discourse). A pattern in which an agent-sensitive element is not anchored to the speaker whose speech is being reported, but shifts over to some other agent, or to the narrator, has, to our knowledge, never been observed before. Hence the proposed explanation of the results of our studies does not, after all, rely on any familiar mechanism and definitely does not fit the pattern of perspectival shift evidenced in previous empirical studies on expressives.

6. Conclusion and prospects for further research

Our aim in this work has been to pin down the main tenets of what we take to be the influential view of expressives and test them on empirical grounds. Most existing accounts hold that the content associated with expressives is attitudinal and agent-oriented, and that referring to someone as ‘a jerk’ communicates how a salient agent, typically the speaker, feels about this person (Claim 1). A related assumption is that expressives impose no strong contextual felicity constraint, i.e., for their use to be felicitous, the context need not entail any specific information about the speaker, the target or their relationship (Claim 2). While most of the literature has focused on referential uses only, we have followed Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic (Reference Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic2021) in incorporating predicative uses. What is more, we have decided to focus on predicative uses, because referential uses make it hard to disentangle the content associated with the expressive itself from whatever content is triggered by the complex demonstrative construction (that jerk). Extending the influential view to predicative uses, we have tried to engage with its two main claims on empirical grounds. We have replicated Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic’s (Reference Cepollaro, Domaneschi and Stojanovic2021) results that speak against Claim 2 (as regards predicative uses). More importantly, we have engaged empirically with Claim 1. While there exists a body of previous experimental work on the content of negative expressives, in particular Harris and Potts (Reference Harris and Potts2009), Harris (Reference Harris2012) and Kaiser (Reference Kaiser2015), it is important to keep in mind that what those studies asked is whether the attitudinal content associated with the expressive could be anchored to someone other than the speaker. They did not question Claim 1, as we understand it here, which relies on the idea that this content is attitudinal in the first place, and that it is agent-oriented (even if the agent need not be the speaker). We believe that our results present a certain challenge to this more general assumption. For one, participants consider the use of stronzo to be the most acceptable in the target-oriented condition (Study 1); for another, they prefer a target-oriented paraphrase (Study 2). Last but not least, our studies reveal some interesting asymmetries in behavior between positively versus negatively valenced non-expressive evaluatives, which invite further investigation.Footnote 15

Acknowledgements

Bianca Cepollaro gratefully acknowledges the support received from the PRIN projects “The Mark of Mental (MOM)” (Ministero dell‘Università e della Ricerca [MUR], 2017P9E9N) at Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan, as well as the support from the COST Action CA17132 “European Network for Argumentation and Public Policy Analysis”. Bianca Cepollaro and Filippo Domaneschi would like to extend their gratitude for the support received from the project “Explaining Pejoratives in Theoretical and Experimental Terms (EPITHETS)” (Ministero dell‘Università e della Ricerca [MUR], 2022N87CR9) at Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan, and the University of Genoa. Isidora Stojanovic’s work has been funded by the European Union, as part of the ERC Advanced Grant Valence Asymmetries, Grant Agreement Nº 101142133. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Competing interest

All authors have equally contributed to the manuscript, have approved the final version and declare no conflicts of interest. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.