1. Introduction

Language comprehension involves integrating linguistic and extralinguistic information (Hagoort, Reference Hagoort2019; Hagoort & Berkum, Reference Hagoort and Berkum2007). The prominent effect of social hierarchical information from linguistic and extralinguistic sources on language comprehension has been evidenced in several studies (Ashizuka et al., Reference Ashizuka, Mima, Sawamoto, Aso, Oishi, Sugihara, Kawada, Takahashi, Murai and Fukuyama2015; Cui et al., Reference Cui, Jeong, Okamoto, Takahashi, Kawashima and Sugiura2022; Garvey et al., Reference Garvey, Caramazza and Yates1975; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Li and Zhou2013; Kwon & Sturt, Reference Kwon and Sturt2016; Momo et al., Reference Momo, Sakai and Sakai2008; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022). Social hierarchical information is intrinsically embedded in the semantics of some second singular personal pronouns (see Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Li and Zhou2013) and Chinese social hierarchical verbs (Ma, Reference Ma and Ma1997; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022; Yang, Reference Yang2012; Zhang, Reference Zhang1997; Zou, Reference Zou2009). Chinese social hierarchical verbs can impose semantic selectional restrictions on the relative hierarchy of its two arguments. For example, the verb 赡养 (Chinese Pinyin, /shan4yang3/, English, ‘support: provide for the needs and comfort of one’s elders’) only allows its Agent to lower in the social hierarchy than the Patient (Ma, Reference Ma and Ma1997; Yang, Reference Yang2012; Zhang, Reference Zhang1997; Zou, Reference Zou2009). The social hierarchical information not only exists within the semantics of some pronouns and verbs, but is also implied in extralinguistic information provided by the noun pairs (e.g., father-grandfather; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022). However, the precise time course of the integration of linguistic and extralinguistic sources of social hierarchical information during online comprehension remains unclear.

Two models have been proposed to explain when linguistic and extralinguistic information would influence language interpretation (Hagoort & Berkum, Reference Hagoort and Berkum2007). The one-step model claims that during sentence comprehension, all available relevant information (e.g., syntax, prior discourse, and world knowledge) can be immediately used to co-determine the interpretation of a sentence (Clark, Reference Clark1996; Hagoort, Reference Hagoort2019; Hagoort et al., Reference Hagoort, Hald, Bastiaansen and Petersson2004; Jackendoff, Reference Jackendoff2002; MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Pearlmutter and Seidenberg1994; Nieuwland & Van Berkum, Reference Nieuwland and Van Berkum2006; Tanenhaus & Trueswell, Reference Tanenhaus, Trueswell, Miller and Eimas1995; Van Berkum et al., Reference Van Berkum, Van den Brink, Tesink, Kos and Hagoort2008). In contrast, the two-step model argues that the interpretation of a sentence takes place in two stages. First, the initial sentence meaning is computed by combining fixed word meanings derived from its syntactic structure; once this stage is completed, information from prior discourse and extralinguistic world knowledge is integrated to constrain the interpretation of the sentence (Cutler & Clifton, Reference Cutler, Clifton, Brown and Hagoort1999; Fodor, Reference Fodor1983; Lattner & Friederici, Reference Lattner and Friederici2003; Sperber & Wilson, Reference Sperber and Wilson1995).

Two psycholinguistic studies using electroencephalograph (EEG) have documented the neural response to a mismatch between linguistic and extralinguistic sources of social hierarchical information (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Li and Zhou2013; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022). Jiang et al. (Reference Jiang, Li and Zhou2013) found that pronouns that violated the social status of the speaker and the addressee in communication elicited an anterior N400-like effect followed by a delayed sustained effect that varied in accordance with the pragmatic implications of the pronouns. This study suggested the mismatch between linguistic and extralinguistic hierarchical information could cause difficulties in semantic integration.

Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022) extended the research on pronouns to study Chinese social hierarchical verbs. As the core constituent in a sentence, a verb serves as the pivot to link other nominal arguments (Fillmore, Reference Fillmore, Bach and Harms1968). Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022) manipulated Verb Type (hierarchical vs. non-hierarchical) and Social Hierarchy Sequence (match vs. mismatch) and found that compared to matched extralinguistic social hierarchy sequences, those that violated the verbs’ social hierarchical restriction (e.g., *爷爷精心赡养着爸爸, /ye2ye0 jing1xin1 shan4yang3zhe0 ba4ba0/, ‘The grandfather supports the father carefully’) evoked stronger anterior negativity on the sentence-final noun (NP2) in the 300–500 ms time window. The results suggested that the verbs’ social hierarchical restriction could be available during online comprehension and be integrated with extralinguistic social hierarchical information to influence sentence interpretation. The extralinguistic social hierarchy sequence that violated the verbs’ social hierarchical restriction caused difficulties in semantic integration. It was proposed that these difficulties might be closely associated with violations of readers’ event knowledge. This event knowledge captures some specific information about the Agents and Patients that are most likely to participate in familiar and repeatable events or states described by the verbs, and it is inherently about the events in specific situations (Matsuki, Reference Matsuki2013; McRae et al., Reference McRae, Ferretti and Amyote1997; McRae & Matsuki, Reference McRae and Matsuki2010; Metusalem et al., Reference Metusalem, Kutas, Urbach, Hare, Mcrae and Elmana2012; Paczynski & Kuperberg, Reference Paczynski and Kuperberg2012). In hierarchically inappropriate sentences, the relative social hierarchy of the Agent and Patient conflicts with readers’ event knowledge, thus leading to difficulties in semantic integration.

The EEG results reported by Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022) suggest that the social hierarchical information from the verb’s semantic selectional restrictions and extralinguistic sources could be integrated and influence sentence interpretation. However, this study has the limitation of using the rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP) unnatural reading mode to present stimulus, which precludes identification of the specific process underlying this integration during natural reading. In this mode, the parafoveal-to-foveal effect cannot be observed because participants cannot see the critical word while reading the word that precedes it. Comparatively speaking, eye-tracking techniques that mimic natural reading can overcome the drawbacks of the RSVP unnatural reading mode (Rayner et al., Reference Rayner, Warren, Juhasz and Liversedge2004; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Tang and Privitera2023; Zang et al., Reference Zang, Zhang, Zhang, Bai, Yan, Jiang, He and Zhou2019). And in eye-tracking research, various indices have been used to measure different stages of language processing (Clifton et al., Reference Clifton, Ferreira, Henderson, Inhoff, Liversedge, Reichle and Schotter2016). In the current study, the early measures, including the first fixation duration (FFD, the duration of the first fixation on a region during the first pass reading) and gaze duration (GD, the sum of all fixations on a region before moving to another region), were used to detect the process during the initial integration stage in reading. The late measures, used to reflect the reading pattern in later-stage processing, included total reading time (TRT) and regression path duration (RPD). The total reading time (TRT) is the sum of all fixation durations in a region. The regression path duration (RPD) is the sum of fixation durations from when a region was first fixated until the eyes first moved right outside of the region, including the time regressed to regions preceding this region. Together, the early and late eye-tracking measures can reveal the time course of the process in which social hierarchical information embedded in Chinese social hierarchical verbs is integrated with information from extralinguistic hierarchical knowledge during natural reading.

To the best of our knowledge, no eye-tracking study to date has directly focused on a verb’s social hierarchical restrictions or extralinguistic social hierarchical knowledge as a way to detect the integration between linguistic and extralinguistic sources of social hierarchical information. Several studies have adopted eye-tracking techniques to investigate the time course of participants’ use of other types of semantic selectional restrictions of verbs and event knowledge during sentence comprehension (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Liversedge, Blythe, White, Gathercole and Rayner2008; Rayner et al., Reference Rayner, Warren, Juhasz and Liversedge2004; Warren et al., Reference Warren, Mcconnell and Rayner2008, Reference Warren, Milburn, Patson and Dickey2015). The findings exhibited an immediate disruptive effect of a violation of verbs’ semantic selectional restrictions but a delayed effect of event implausibility (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Liversedge, Blythe, White, Gathercole and Rayner2008; Rayner et al., Reference Rayner, Warren, Juhasz and Liversedge2004; Warren et al., Reference Warren, Mcconnell and Rayner2008). Rayner et al. (Reference Rayner, Warren, Juhasz and Liversedge2004) manipulated the degree of event implausibility and investigated its impact on sentence interpretation. Compared with plausible sentences (likely themes such as John used a knife to chop the large carrots for dinner), sentences that were anomalous (inappropriate themes such as John used a pump to inflate the large carrots for dinner) induced longer early eye movement on the target word. This result provided evidence of the immediate disruption effect on sentence comprehension caused by the violation of verbs’ semantic selectional restrictions. However, disruption caused by implausible sentences (unlikely themes such as John used an axe to chop the large carrots for dinner) was detected only on late measures. The results suggested that violations of verbs’ semantic selectional restrictions and event knowledge might disrupt sentence comprehension at different stages.

To elucidate whether knowledge of verbs’ semantic selectional restrictions is privileged among all available knowledge during sentence comprehension, Warren et al. (Reference Warren, Mcconnell and Rayner2008) compared processing disruption caused by impossible events cued by verbs’ semantic selectional restriction violations (impossible-implausible, e.g., The man used a photo to blackmail the thin spaghetti yesterday evening) and that caused by possible but implausible events without semantic selectional restriction violations (possible-implausible, e.g., The man used a blow-dryer to dry the thin spaghetti yesterday evening). The results showed that compared with the possible-implausible condition, the impossible-implausible condition induced longer first fixation on the target word (e.g., spaghetti), and this effect continued in the post-target region. In contrast, compared with the possible-plausible condition (e.g., The man used a strainer to drain the thin spaghetti yesterday evening), the possible-implausible condition caused longer regression path duration on the target word. Thus, the authors proposed that semantic feature matching between the verb and its arguments occurred before world knowledge about event plausibility was available. Further, Warren et al. (Reference Warren, Milburn, Patson and Dickey2015) demonstrated that the verbs’ semantic selectional restrictions can be dissociated from general event knowledge during language comprehension. These studies jointly showed that participants’ integration of event knowledge occurred in later-stage processing relative to their use of the verbs’ semantic selectional restrictions during natural reading.

However, the semantic selectional restrictions that were violated in the above studies were coarser restrictions. For example, John drank a tree has a coarse restriction because the verb drink requires a liquid object, but a tree is not liquid. These semantic selectional restriction violations can be detected based on purely lexical information during initial interpretation (Warren et al., Reference Warren, Mcconnell and Rayner2008). Unlike these coarser restrictions, the social hierarchical restriction of verbs is a finer constraint that is imposed on the relative social hierarchy of the verbs’ two arguments (Ma, Reference Ma and Ma1997; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022; Yang, Reference Yang2012; Zhang, Reference Zhang1997; Zou, Reference Zou2009). The detection of this restriction violation depends on readers’ correct judgment of the relative social hierarchy. Therefore, further investigation is required to explore how the social hierarchical restriction interacts with extralinguistic social hierarchical knowledge to affect sentence comprehension.

Using the same design and stimuli from Shi et al.’s (Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022) study, we adopted the eye-tracking technique, which has high ecological validity and time sensitivity, to identify the specific process underlying the integration of the social hierarchical information embedded in Chinese social hierarchical verbs and information from extralinguistic sources. We anticipated two possible results regarding the critical sentence-final NP2 in the hierarchically inappropriate versus appropriate conditions. The one-step model assumes that the integration process starts immediately. This immediate effect would be reflected in a significant difference between the two conditions at the initial stage of processing as indicated by early measures such as first fixation and gaze duration. Alternatively, according to the two-step model, the integration process occurs only at a later stage. In this instance, the violation effect would be only detected by late measures, such as regression path duration and total reading time. More importantly, there would be no significant difference between two non-hierarchical conditions for either early or late measures, and only in this case could we attribute the violation effect to the difficulty of integrating the semantic restrictions of Chinese social hierarchical verbs and extralinguistic social hierarchical information.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Thirty-two native Chinese speakers (15 males; age range: 18–24 years) were recruited. All participants were right-handed, with normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and without a history of psychiatric problems. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the experiment. Each participant was given a financial reward after the experiment. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiangsu Normal University.

2.2 Stimuli

We used the same stimuli as in Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022), constituting 240 verbs, 120 noun pairs, and their combinations. There were 120 Chinese social hierarchical verbs (verbs with a social hierarchical restriction, e.g., 赡养, /shan4yang3/, ‘support: provide for the needs and comfort of one’s elders’). There were 120 non-hierarchical verbs (verbs without a social hierarchical restriction, e.g., 看见, /kan4jian4/, ‘see: to become aware of somebody or something by using your eyes’). There were 120 social hierarchy noun pairs (e.g., 爸爸, /ba4ba0/, ‘father’; 爷爷, /ye2ye0/, ‘grandfather’) involving family members, job titles, and government positions. Then we combined each of the noun pairs with 120 Chinese social hierarchical verbs to create sentences for the hierarchically appropriate condition (HA), such as 爸爸精心赡养着爷爷, /ba4ba0 jing1xin1 shan4yang3zhe0 ye2ye0/, ‘The father is supporting the grandfather carefully’, and we combined each of the noun pairs with 120 non-hierarchical verbs to create sentences for the hierarchically appropriate control condition (HAC), such as 爸爸昨天见到了爷爷, /ba4ba0 zuo2tian1 jian4dao4le0 ye2ye0/, ‘The father saw the grandfather yesterday’. Finally, the subject and object in the HA and HAC sentences were exchanged to create sentences for the hierarchically inappropriate condition (HIA), such as 爷爷精心赡养着爸爸, /ye2ye0 jing1xin1 shan4yang3zhe0 ba4ba0/, ‘The grandfather is supporting the father carefully’) and the hierarchically inappropriate control (HIAC), such as爷爷昨天见到了爸爸, /ye2ye0 zuo2tian1 jian4dao4le0 ba4ba0/, ‘The grandfather saw the father yesterday’. In total, there were 120 sets of stimuli, each with four sentences, without repetition of verbs or social pairs repetition across sets.

All sentences were in subject-verb-object (SVO) structure. We matched the character frequency, t(119) = 1.26, p = 0.21, and the number of strokes, t(119) = −1.62, p = 0.11, of the target words (i.e., sentence-final object noun) between the appropriate and inappropriate conditions (e.g., ‘grandfather’ and ‘father’, respectively, in Table 1). There was no significant difference in stroke number between Chinese social hierarchical and non-hierarchical verbs, t(119) = −0.35, p = 0.72. However, compared with the non-hierarchical verbs, the character frequency of hierarchical verbs was significantly lower, t(119) = −6.95, p < 0.001.

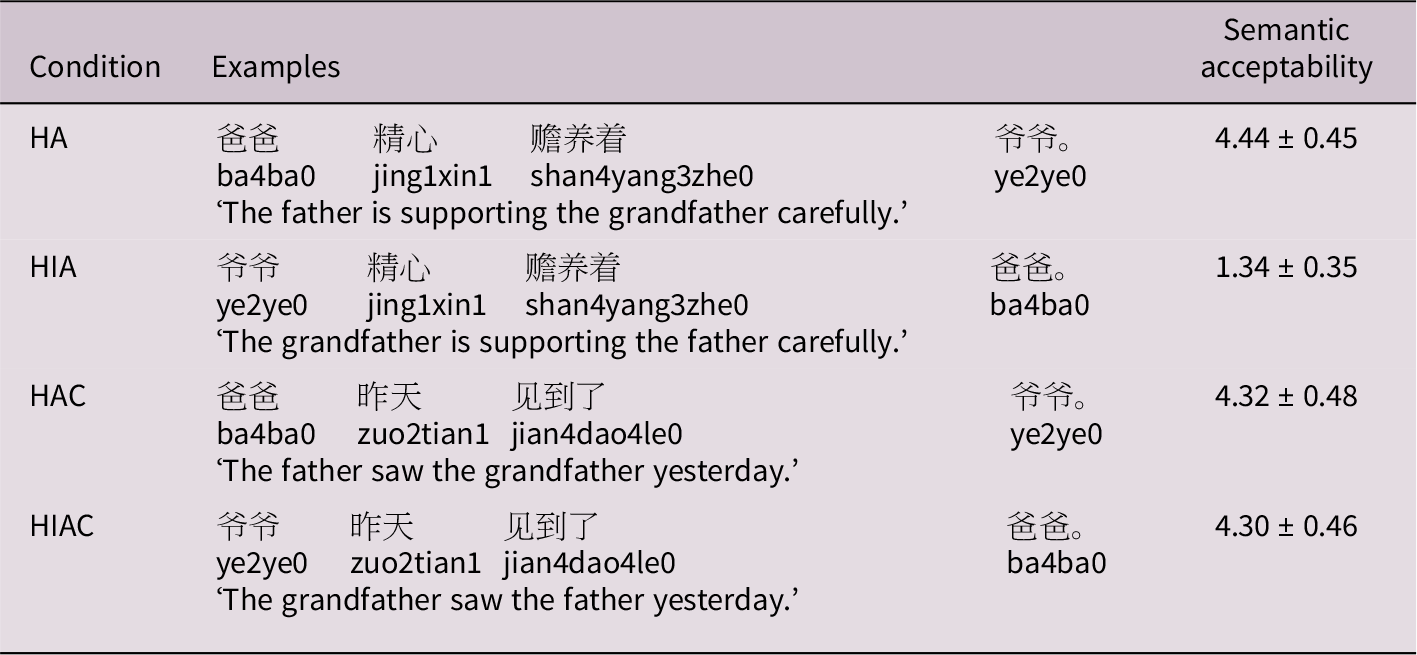

Table 1. Examples of stimuli and the means and standard errors of semantic acceptability ratings

Abbreviations: HA, hierarchically appropriate condition; HAC, hierarchically appropriate control; HIA, hierarchically inappropriate condition; HIAC, hierarchically inappropriate control.

Twenty participants who did not participate in the eye-tracking study rated the semantic acceptability of all sentences on a 5-point Likert scale (1 for totally unacceptable and 5 for fully acceptable). The means and standard errors (in parenthesis) of the rating scores in each condition are shown in Table 1. We conducted repeated-measures analyses of variance (RM-ANOVAs) on the acceptability rating scores using the factors Verb Type (hierarchical, non-hierarchical) and Social Hierarchy Sequence (mismatch, match). There was a significant main effect of Verb Type, F(1, 119) = 1,072, p < 0.001, and Social Hierarchy Sequence, F(1, 119) = 1,507, p < 0.001. The Verb Type by Social Hierarchy Sequence interaction was also significant, F(1, 119) = 1,475, p < 0.001. Simple main effects analysis revealed higher acceptability of the HA condition than HIA condition sentences, t(238) = −59.55, p < 0.001, but no significant difference between the HAC and HIAC conditions, t(238) = −0.34, p = 0.73.

The 120 sets of sentences were then divided into four lists, counterbalanced across participants and conditions. Verbs and social noun pairs were not repeated in any participant’s list. An additional 30 semantically unacceptable filler sentences with the same structures, such as 工人顺利修建了教授, /gong1ren2 shun4li4 xiu1jian4 le0 jiao4shou4/, ‘The workers built the professor smoothly.’ were created for each list.

2.3 Apparatus

Eye movements were recorded with an Eyelink 1000 plus system (SR Research Ltd., Canada) at a sampling rate of 1,000 Hz. Stimuli were presented at the middle vertical position of a 19-inch Dell screen. The viewing distance was 91 cm, and only eye movements of the right eye were analyzed. Each sentence was presented in a single line by Experiment Builder (EB) software in black on white background in Song font No. 26. The maximal visual angle of Each Chinese character was 0.630. The experimental data were recorded simultaneously by another computer.

2.4 Procedure

Participants were informed of the experimental instructions and task. Then, they completed a nine-point calibration procedure with an average calibration error below 0.50 degrees. After the calibration, they read sentences appearing on the screen and judged the plausibility of each sentence using a reaction box. For half of the participants, the left button indexed “yes” and the right button indexed “no.” For the other half, the left button indexed “no” and the right button indexed “yes.” All participants were asked to press the left button with their left index finger and the right button with the right one. Sixty percent of the trials required a “yes” answer, and the remaining trials required a “no” answer. After each sentence, participants completed a drift validation. Before the formal experiment, proper exercises were carried out to ensure that participants correctly understood the experimental task. The experiment lasted approximately 30 min.

2.5 Data analyses

Three regions of interest were predefined for analysis: NP1 ROI at sentence-initial position (e.g., 爸爸, /ba4ba0/, ‘father’), VP ROI (e.g., 赡养着, /shan4yang3zhe/, ‘support: provide for the needs and comfort of one’s elders’), and NP2 ROI at sentence-final position (e.g., 爷爷, /ye2ye0/, ‘grandfather’). In the present study, FFD and GD were used for early stage measurements, and TRT and RPD were used for later stage measurements. Trials with durations shorter than 50 ms or longer than 800 ms, 1,000 ms or 1,500 ms were excluded from analyses for FFD, GD, and TRT, respectively. Trials with no fixation in a region of interest were excluded from analyses for all duration measures. All fixation duration measures were analyzed using log-transformed data.

Linear mixed models (LMMs) were used for all duration measures and RT as dependent variables, and generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were used when accuracy was the dependent variable, using the lme4_1.1-26 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015). The p-values for t-statistics in the LMMs were computed using the lmerTest_3.1-3 package (Kuznetsova et al., Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017) in R-studio (R version 3.6.3, http://cran.r-project.org). We used the sum contrast to code two fixed factors, namely Matrix Verb Type (hierarchical verb vs. non-hierarchical verb) and Matrix Hierarchical Sequence Type (mismatch sequence vs. match sequence). We fitted all models with Matrix Verb Type, Matrix Hierarchical Sequence Type, and their interaction as fixed factors. Following Chang et al. (Reference Chang, Duan, Qian, Wu, Jiang and Zhou2020), random effects included by-participant and by-item random intercepts and random slopes were determined by backward model selection according to the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC, Akaike, Reference Akaike1974) and the χ 2-distributed likelihood-ratio test (Matuschek et al., Reference Matuschek, Kliegl, Vasishth, Baayen and Bates2017).

The model selection procedure started with the full model, including by-participant and by-item random intercepts and the random slopes for all fixed factors (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2013). We fitted a set of reduced models by excluding one of the random slopes. By comparing the AICs of these reduced models, we selected the one with the minimum AIC and compared it with the more complex model by a likelihood-ratio test. We would select the more complex model when the p-value of a χ 2-statistic was smaller than 0.2 (Matuschek et al., Reference Matuschek, Kliegl, Vasishth, Baayen and Bates2017). Otherwise, we repeated to reduce the model until a model was selected or all the random slopes were excluded. Models that failed to converge were not considered in this procedure.

In the ‘Results’ section, we report the parameter estimates (b), standard errors (SE), t or z statistics, and p-values of the best models selected by backward model selection.

3. Results

3.1 Comprehension task data

The M (SE) of accuracy scores in the HA, HIA, HAC, and HIAC conditions were 94.0% (1.0%), 88.0% (1.0%), 88.0% (1.0%), and 87.0% (1.0%), respectively. There were significant main effects of Verb Type (b = 0.64, SE = 0.22, z = 2.95, p = 0.003) and Social Hierarchy Sequence (b = −0.56, SE = 0.12, z = −4.68, p < 0.001). The accuracy was higher in hierarchical conditions compared to non-hierarchical conditions and higher in match conditions compared to mismatch conditions. The Verb Type by Social Hierarchy Sequence interaction (b = −0.79, SE = 0.24, z = −3.33, p = 0.001) was also significant. Simple main effects analysis was used to interpret the interaction. There was higher accuracy in the HA condition than in the HIA condition (b = −0.89, SE = 0.18, z = −4.95, p < 0.001), but no difference between the HAC and HIAC conditions (b = −0.21, SE = 0.15, z = −1.40, p = 0.163).

The M (SE) of RT in the HA, HIA, HAC, and HIAC conditions was 2005 (38 ms), 2104 (39 ms), 2077 (38 ms), and 2041 (34 ms), respectively. There were no significant main or interaction effects (Verb Type: b = −0.01, SE = 0.03, t = −0.32, p = 0.748; Social Hierarchy Sequence: b = 0.03, SE = 0.02, t = 1.85, p = 0.066; Interaction: b = 0.05, SE = 0.03, t = 1.78, p = 0.078).

3.2 Online eye-movement measures

Results of LMM on eye movement measures showed no effects in the NP1 ROI. Thus, we do not report results for this region. Table 2 shows the untransformed means of the eye movement measures for each condition in the remaining two ROIs.

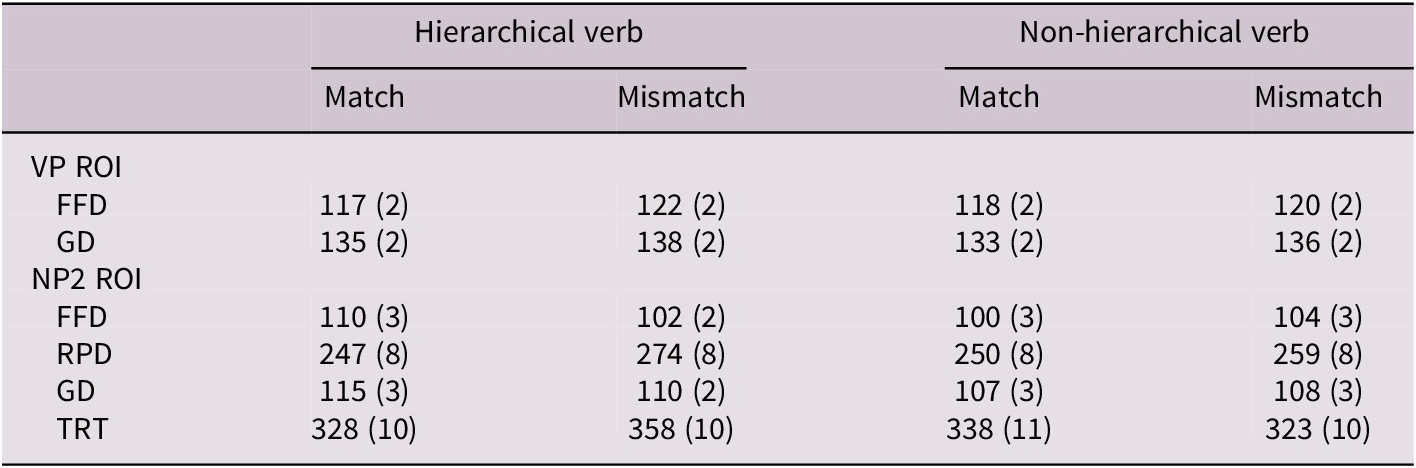

Table 2. Means and standard errors (in parenthesis) of eye-movement measures for four experimental conditions

Abbreviations: FFD, first fixation duration; GD, gaze duration; RPD, regression path duration; TRT, total reading time.

3.2.1 The VP ROI

In the VP ROI, a significant main effect of Hierarchical Sequence was found on first fixation duration (b = 0.03, SE = 0.01, t = 2.05, p = 0.041) and gaze duration (b = 0.03, SE = 0.01, t = 2.03, p = 0.042). For these two measures, there was longer duration for the mismatched sequence compared with the matched sequence (FFD: 121 vs. 118 ms; GD: 137 vs. 134 ms).

3.2.2 The sentence-final NP2 ROI

In the NP2 ROI, there was a significant main effect of Verb Type (b = 0.06, SE = 0.02, t = 2.52, p = 0.012) on gaze duration. Participants had longer gaze duration in hierarchical conditions compared to non-hierarchical conditions (112 vs. 107 ms). Different results were found for other dependent measures. There was a significant Verb Type by Hierarchical Sequence interaction effect on first fixed duration (b = −0.09, SE = 0.05, t = −2.03, p = 0.043), regression path duration (b = 0.36, SE = 0.16, t = 2.25, p = 0.024), and total reading time (b = 0.13, SE = 0.05, t = 2.66, p = 0.008). Simple main effects analyses were used to interpret these interactions. There was no significant difference between the two non-hierarchical verb conditions on first fixed duration (b = 0.03, SE = 0.03, t = 0.91, p = 0.363), regression path duration (b = 0.01, SE = 0.15, t = 0.06, p = 0.949), or total reading time (b = −0.02, SE = 0.04, t = −0.64, p = 0.524). By contrast, there were significant differences between the two hierarchical verb conditions. First fixation duration was shorter in the HIA condition than in the HA condition (b = −0.06, SE = 0.03, t = −1.95, p = 0.052, 102 vs. 110 ms), but regression path duration and total reading time were longer in the HIA condition than in the HA condition (RPD: b = 0.36, SE = 0.18, t = 2.07, p = 0.044, 274 vs. 247 ms; TRT: b = 0.09, SE = 0.04, t = 2.12, p = 0.036, 358 vs. 328 ms).

4. Discussion

Using an eye tracking technique with high ecological validity and time sensitivity, the present study mapped the precise time course of the integration of the semantic selectional restrictions of Chinese social hierarchical verbs and extralinguistic social hierarchical information during natural reading. Online eye-movement measures revealed that compared to the hierarchically appropriate condition, readers showed shorter FFD but longer RPD and longer TRT in the hierarchically inappropriate condition. These differences were absent when two non-hierarchical conditions were compared. The effects indicated by early measures are more in line with the assumptions of the one-step model than the two-step model of language comprehension.

Consistent with Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022), the present study showed that violations of the verb’s social hierarchical restrictions could interrupt sentence interpretation. Importantly, the results further suggested that disruption was immediate. In Shi et al.’s (Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022) study, the violations of social hierarchical restrictions, such as *爷爷精心赡养着爸爸, /ye2ye0 jing1xin1 shan4yang3zhe0 ba4ba0/, ‘The grandfather is supporting the father carefully’, evoked a stronger anterior negativity around 350 ms after the onset of NP2, indicating difficulties in semantic integration. In the current study, the violation effect as indexed by FFD occurred around 100 ms after the onset of NP2. The difference may reflect the timing sensitivity of the two techniques. In Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022), the RSVP unnatural reading mode may have interfered with the real-time course of the integration between the social hierarchical restrictions and extralinguistic social hierarchical information during sentence reading. In the current study, the effects observed on the FFD suggested that during comprehension, readers could immediately activate and utilize extralinguistic social hierarchical information from NP1–NP2 noun pairs to detect violations of the social hierarchical restrictions.

The interpretation of hierarchically inappropriate sentences can be divided into detection and verification stages, indicated by the effect on FFD and RPD, respectively. The verb’s social hierarchical restriction was a finer constraint imposed by the relative social hierarchy of its two arguments, and detection of its violation was determined by this relative hierarchy. For example, the social hierarchy of the Agent of the verb 赡养, /shan4yang3/, ‘support: provide for the needs and comfort of one’s elders’ must be lower than its Patient (Ma, Reference Ma and Ma1997; Yang, Reference Yang2012; Zhang, Reference Zhang1997; Zou, Reference Zou2009). Therefore, when 爸爸, /ba4ba0/, ‘father’ and 爷爷, /ye2ye0/, ‘grandfather’ were the Agent and Patient of this verb, respectively, the sentence 爸爸精心赡养着爷爷, /ba4ba0 jing1xin1 shan4yang3zhe0 ye2ye0/, ‘The father is supporting the grandfather carefully’ was acceptable. However, when 爸爸, /ba4ba0/, ‘father’ as the Agent and 女儿, /nǚ ér/, ‘daughter’ as the Patient, the sentence 爸爸精心赡养着女儿, /ba4ba0 jing1xin1 shan4yang3zhe0 nǚ ér/, ‘The father is supporting the daughter carefully’ was unacceptable. Therefore, for hierarchically inappropriate sentences, when participants encountered NP2s, they might have perceived semantic implausibility and looked back to NP1s to verify the relative social hierarchy of the two arguments. This caused shorter FFD and longer RPD in hierarchically inappropriate compared to appropriate conditions. Wei et al. (Reference Wei, Tang and Privitera2023) also found shorter FFD on the word preceding the critical word (pre-CW) for semantically violated as opposed to correct sentences. Based on our own results and those reported by Wei et al., we can infer that when the participants perceived the semantic violation of the critical word, they further quickly checked this violation.

The longer TRT in the hierarchically inappropriate condition revealed the greater processing effort needed to accomplish integration in a later stage. In the hierarchically inappropriate condition, there was a mismatch between the verb’s social hierarchical restrictions and its arguments’ social properties (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022). In this case, the event representation constructed by the sentence conflicted with the participants’ event knowledge. The conflict then demanded additional effort to re-analyze the linguistic input to accommodate the alternative, more plausible representation (Brouwer et al., Reference Brouwer, Fitz and Hoeks2012). This additional effort is also suggested by performance on the comprehension task, namely longer reaction time but lower accuracy in the hierarchically inappropriate condition.

The processing of hierarchically inappropriate sentences might differ from processing sentences that violated coarser semantic selectional restrictions of verbs. When a coarser selectional restriction was violated, participants would detect it based on purely lexical information. The mismatch between the verb’s selectional restriction and semantic features of its object argument caused the participants’ difficulties in integration. This was manifested as longer first and single fixation duration (Warren et al., Reference Warren, Mcconnell and Rayner2008, Reference Warren, Milburn, Patson and Dickey2015) or gaze duration (Rayner et al., Reference Rayner, Warren, Juhasz and Liversedge2004) on the object argument. The results observed on the early and late measures in the hierarchically inappropriate sentences in the current study, combined with the results of earlier studies showing the violation effect of coarser semantic selectional restrictions (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Liversedge, Blythe, White, Gathercole and Rayner2008; Rayner et al., Reference Rayner, Warren, Juhasz and Liversedge2004; Warren et al., Reference Warren, Mcconnell and Rayner2008, Reference Warren, Milburn, Patson and Dickey2015), lead us to infer that the violations of social hierarchical and coarser semantic selectional restrictions trigger different cognitive processes.

It should be noted that in the verb ROI, compared with matched sequences, participants showed longer FFD and GD on mismatched sequences. Specifically, the difference between the two hierarchical verb conditions was numerically greater than that between the two non-hierarchical verb conditions. This effect might be attributed to a parafoveal effect from NP2s. Several studies have shown that processing information being fixated might be influenced by the information presented in the parafoveal region (Inhoff et al., Reference Inhoff, Starr and Shindler2000; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2000; Starr & Inhoff, Reference Starr and Inhoff2004; Vitu et al., Reference Vitu, Brysbaert and Lancelin2004). Rayner et al. (Reference Rayner, Warren, Juhasz and Liversedge2004) reported that gaze duration in the semantic selectional restriction violation condition was longer than that in the implausible and control conditions in the pre-target region. The researchers interpreted this as a parafoveal-on-foveal effect, meaning that participants semantically pre-processed the target word when they fixated the pre-target word. Similarly, in the current study, when participants fixated the verbs, they might have extracted some properties of NP2s. In the hierarchically inappropriate condition, this semantic pre-processing of NP2s made participants spend more time fixating verbs to confirm their social hierarchical restrictions. The parafoveal-on-foveal effect here may have benefited from the more natural reading mode used in this study, whereas the effect was not observed using the RSVP paradigm in which sentence segments are sequentially presented (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022). In a word, the effects found on the verbs suggest that the integration can be traced back to a very early stage.

Given the evidence, when did participants’ event knowledge related to Chinese social hierarchical verbs start to exert its effect on sentence interpretation? We propose that this event knowledge is effectively encapsulated in the semantics of Chinese social hierarchical verbs and can affect sentence interpretation at the early stage. Consistent with Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Zhou, Zhu and Yang2022), the recognition of a Chinese social hierarchical verb appeared to accompany the automatic activation of the verb’s relevant thematic/event knowledge. In the hierarchically inappropriate condition, the event knowledge related to Chinese social hierarchical verbs was violated, and this violation could be detected immediately, as indicated by its effect on the FFD observed on NP2.

It must be pointed out that several studies have found that participants’ integration of general event knowledge (e.g., The man used a blow-dryer to dry the thin spaghetti yesterday evening) occurred in a later stage (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Liversedge, Blythe, White, Gathercole and Rayner2008; Rayner et al., Reference Rayner, Warren, Juhasz and Liversedge2004; Warren et al., Reference Warren, Mcconnell and Rayner2008, Reference Warren, Milburn, Patson and Dickey2015), and these results may challenge our findings. This discrepancy might be due to differences in the event knowledge related to Chinese social hierarchical verbs. For example, in the sentence The man used a blow-dryer to dry the thin spaghetti yesterday evening, the candidate object arguments of the verb dry range widely, and the semantic features of the object argument the thin spaghetti match its semantic selectional restriction. It is implausible but possible for a man to use a blow-dryer to dry the thin spaghetti, and this possibility may have delayed the processing of event knowledge in previous studies. However, for the Chinese social hierarchical verbs (e.g., 赡养, /shan4yang3/, ‘support: provide for the needs and comfort of one’s elders’) in the present study, the candidate object arguments in the context (e.g., 爷爷精心赡养着…, /ye2ye0 jing1xin1 shan4yang3zhe0…/, ‘The grandfather is carefully supporting…’) were relatively few. The relevant event knowledge was already encapsulated in the semantics of these verbs. Therefore, the violation of the verbs’ social hierarchical restrictions was accompanied by the violation of the related event knowledge and thus disrupted sentence interpretation at the early stage. The benefit of this encapsulation was also evidenced by the accuracy scores, which indicated that the comprehension of hierarchical verb conditions was promoted even though the character frequency was lower for the hierarchical verbs than the non-hierarchical verbs.

It is still unclear whether extralinguistic information can be immediately used to co-determine the interpretation of a sentence during language comprehension. In this study, the interpretation of the hierarchically inappropriate sentences just right involved integrating linguistic and extralinguistic social hierarchical information. Our eye-tracking evidence of the precise time course of processing these sentences enlightens the debate on the one-step and two-step models of language comprehension. Nevertheless, in this study, the critical word was at the sentence-final position and the results might be affected by possible wrap-up effects, and future research can use discourse materials to address this issue.

5. Conclusion

The semantics of Chinese social hierarchical verbs, by their very nature, encapsulate intrinsic social hierarchical information. Using an eye tracking technique with high ecological validity and time sensitivity, the present study examined the precise time course of the integration of a verb’s social hierarchical restrictions and extralinguistic social hierarchical information during natural reading. We found that violations of semantic selectional restrictions of Chinese social hierarchical verbs induced shorter FFD but longer RPD and longer TRT on sentence-final nouns (NP2). These results suggest that the mismatch between linguistic and extralinguistic social hierarchical information is detected immediately in the brain, in line with the assumptions of the one-step model of language comprehension.

Data availability statement

The data and analysis scripts related to the reported results are available on OSF: https://osf.io/hkyaj/.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Xiulin Gu for vital guidance on the experimental operation.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the National Social Science Major Bidding Project of China (22&ZD298) and the Shanghai International Studies University Mentorship Program (2020114229).

Competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.