1. Introduction

Are speakers perceived to be committed only to what they say, or also to what they mean (even when it is not said)? The exact boundaries of the saying–meaning distinction are much discussed in semantics and pragmatics (Austin, Reference Austin1962; Carston, Reference Carston and Bianchi2004; Grice, Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1957; Recanati, Reference Recanati2004; Searle, Reference Searle1969; Sperber & Wilson, Reference Sperber and Wilson1986/1995; Wilson & Sperber, Reference Wilson, Sperber, Horn and Ward2004). Some researchers have proposed that this distinction is of key relevance to how commitment is created in communication. In particular, researchers of different backgrounds have proposed that commitments are stronger when meaning is fully linguistically encoded than when it is only implied (Moeschler, Reference Moeschler2013; Morency, Oswald, & De Saussure, Reference Morency, Oswald and De Saussure2008; Reboul, Reference Reboul and Assimakopoulos2017). This idea, in short, is that we are more strongly committed to what we say than to what we merely mean. Recent experimental work has been interpreted as providing empirical grounds for this idea (e.g., Lee & Pinker, Reference Lee and Pinker2010; Mazzarella, Reinecke, Noveck, & Mercier, Reference Mazzarella, Reinecke, Noveck and Mercier2018). In general, within this literature, commitment is understood as speakers’ endorsement or distance from what they communicate (see, e.g., Boulat & Maillat, Reference Boulat, Maillat, Grisot, Durrleman and Länzingler2017).

Here we present theoretical arguments against this picture, and experimental data highlighting clear counter-examples. Specifically, we argue that in the most general perspective what communicators are committed to is the relevance Footnote 1 of their communicative behaviour, irrespective of whether this is explicitly or implicitly expressed (Section 2). We then present three studies of commitment attribution in the case of promises, contrasting the different roles played by (i) the saying–meaning distinction and (ii) the extent to which an audience relies on what has been expressed (Sections 3–5). Participants were presented with vignettes, comic strips, and video-clips illustrating everyday situations in which a verbal promise was violated by a communicator. We asked them to judge whether a promise was broken, whether the communicator is a desirable partner for future interaction, and whether the communicator is accountable for any broken promise. We manipulated whether the content of the promise was implicitly or explicitly conveyed and whether the intended audience was likely to rely on the promise. Our findings support the hypothesis that the extent to which the audience relies on the communicator’s promise, this being mutually known, is the main factor leading to the attribution of commitment to what has been promised, regardless of whether it is explicit (i.e., linguistically encoded) or implied. This leads us to suggest (Section 6) that the social consequences of the saying–meaning distinction might be overstated. While this distinction is certainly relevant in some institutionalised contexts, such as rituals and legal texts – where what is explicit often has some privileged status – in most individual social interactions the fundamental factor is instead the relevance of what is expressed (Wilson & Sperber, Reference Wilson and Sperber2002).

2. Commitment and relevance

The saying–meaning distinction plays a decisive role in many domains of human cultural life. In legal texts and certain ritualised events such as marriage, it is not enough that the agents ‘mean’ something. Instead what counts is ‘what is said’. One dramatic illustration is the famous Bronston vs. US case (409 U.S. 352 1973). Facing fraud allegations, Mr Bronston replied to the attorney’s question about whether he ever had a personal bank account in Switzerland by uttering the following statement: “The company had an account there for about six months, in Zürich.” While this statement clearly falsely implied that Bronston never himself had a personal bank account in Switzerland, Bronston was acquitted from a perjury indictment. Strategic uses of the saying–meaning distinction such as this are highlighted by the theory of the strategic speaker, according to which speakers use implicit expressions as a way to provide plausible deniability when it might be advantageous to do so (Lee & Pinker, Reference Lee and Pinker2010; Pinker, Nowak, & Lee, Reference Pinker, Nowak and Lee2008).

Building on these observations, some researchers have argued that communicators are not perceived to be equally committed to what they say and to what they mean. One line of argument is that communicators are perceived as less committed to ‘what is meant’ because in cases of implicit communication the audience is somewhat responsible for the interpretation of the implicature (Morency et al., Reference Morency, Oswald and De Saussure2008). A second line of argument is that, since implicatures are cancellable (see Carston, Reference Carston and Bianchi2004), communicators can use them as pragmatic devices to modulate commitment to the message conveyed (Mazzarella et al., Reference Mazzarella, Reinecke, Noveck and Mercier2018). This in turn creates room for plausible deniability, or provides a means by which the cognitive mechanisms that filter incoming information (called ‘epistemic vigilance’; see Sperber et al., Reference Sperber, Clément, Heintz, Mascaro, Mercier, Origgi and Wilson2010) might be bypassed (Reboul, Reference Reboul and Assimakopoulos2017).

There are theoretical reasons to question these arguments. While hearers expect to be provided with relevant information, there is, we suggest, no special reason to expect the information to be fully linguistically encoded (i.e., explicit). It is enough that the information is recognised to be the communicator’s intended meaning. This point is most clearly illustrated by cases of non-linguistic communication. If, for instance, you are asked about the quality of a wine and you then raise your eyebrows and produce a sound of satisfaction while tasting it, you will be perceived as committed to the idea that the wine is good. Such examples speak against the idea that ‘what is said’ should have any special status for commitment attribution, relative to ‘what is meant’. It is true that there are cases in which commitment is tied to ‘what is said’ rather than ‘what is meant’, such as those mentioned above (legal texts, marriage rituals, the Bronston case). We suggest, however, that these are special cases in which the means by which commitments take effect is institutionally formalised in one way or another.

There are, moreover, good reasons to positively expect commitments to be tied to ‘what is meant’, and not ‘what is said’. Aspects of the context that are mutually known can influence the interpretation of communicative stimuli, regardless of what is expressed explicitly or implicitly. This can in turn affect commitment attribution. A speaker saying “It’s 7.30” when it is mutually known that the audience has to catch a train leaving at 7.32 will (likely) be taken as committed to it indeed being 7.30; but the same utterance in other contexts, including when the departure time is not mutual knowledge, will entail a commitment to it being only approximately 7.30 (and quite possibly later than 7.32). Similarly, when someone makes a promise, they should be perceived to be committed to whatever content makes the promise relevant – which is, largely, the extent that the audience will rely on it being kept. The relevance of what is expressed in a promise depends largely on the extent to which the audience will rely on it in some way, i.e., the extent to which the audience is expected to change their course of action under the assumption that the promise is maintained (the speech act is fulfilled). In other cases – assertions, orders, questions, and so on – the relevance of what is expressed will depend also on other factors, but in all cases what matters for commitment attribution is (we suggest) what is put into the common ground (i.e., ‘what is meant’) rather than ‘what is said’.

All in all, we suggest that in the most general perspective what communicators are committed to is what makes their communicative behaviour relevant to the audience (see Van Der Henst, Carles, & Sperber, Reference Sperber and Wilson2002; Wilson & Sperber, Reference Wilson and Sperber2002). Of course, in the case of promises, this commitment is a de facto commitment to performing a future action: it is only by acting upon it that the speaker can satisfy their promise (Searle, Reference Searle1969); this is, however, not the case for other types of speech act, which have different and more complex relationships between content and action, with varying normative consequences (Bach & Harnish, Reference Bach and Harnish1979; but see Geurts, Reference Geurts2019, for a different perspective). Thus, although our study was focused on the specific case of promises, the theoretical point that speakers should be held to be committed to ‘what is meant’ rather than ‘what is said’ should generalise to other speech acts too, such as assertions.

3. Study 1

3.1. HYPOTHESIS

Study 1 tests the hypothesis that the degree to which communicators are taken to be committed to a promise is determined by the degree to which the audience relies on the promise (this being mutually known between the hearer and the speaker), rather than by the degree of explicitness of the promise itself. We contrast promises that are linguistically explicated with promises that need to be pragmatically enriched in order to be understood (more technically, we contrast utterances whose illocutionary force applies to a proposition that does not require any enrichment, with those whose illocutionary force applies to a proposition that does require enrichment). Methodologically, we operationalise commitment by measuring: (1) participants’ explicit moral judgements about the communicator, i.e., about whether the communicator should engage in some reparation strategy following the violation of the commitment; (2) whether participants take into account the violation of a commitment when engaging in partner choice, or, in other words, whether the communicator incurred reputational costs; and (3) whether participants perceive a violation of a promise. If speakers are committed only to what they say, then these judgements should diverge when ‘what is said’ differs from ‘what is meant’. We test this hypothesis by comparing three conditions (Explicit, Enriched, Explicit But Not Relied On) which differ in both the degree to which the hearer relies on the promise (i.e., whether they are expected to change their course of action under the assumption that the promise is fulfilled), and whether the promise applies its force to an unenriched proposition or not (i.e., whether or not it is fully linguistically encoded).

3.2. METHODS

3.2.1. Participants

We implemented a web-based paradigm with a between-subjects design on an online platform (SurveyMonkey). A power analysis using G*Power 3.1 (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007) indicated that a total sample size of 279 participants would be needed to detect a low-to-medium effect size (f = 0.2) with a predicted statistical power of 85% using a one-way ANOVA with alpha at .05. Since we planned to run a non-parametric test, given the nature of our data (Liddell & Kruschke, Reference Liddell and Kruschke2018), we added 15% to our desired sample (Lehmann, Reference Lehmann2006). We thus aimed to collect 321 participants. We included data from all participants who had begun the experiment when we closed the survey collector.

Participants were 322 adults, recruited via SurveyMonkey Audience. Data was discarded from subjects who did not complete the survey (N = 34) and failed one or more control questions (N = 33), leaving 255 subjects (132 females; Mage = 49.43 years, SD = 17.58): 81 in the Explicit condition, 96 in the Enriched condition, and 78 in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition. The sample was composed entirely of North Americans. All participants gave their informed consent by ticking a box prior to the experiment.

The methods used in this and in the following studies are in accordance with the international ethical requirements of psychological research and approved by the EPKEB (United Ethical Review Committee for Research in Psychology) in Hungary.

3.2.2. Stimuli and procedure

Participants were asked to read different hypothetical situations in which a speaker makes a verbal promise, i.e., performs a commissive speech act, which is later found not to be fulfilled.

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of three between-subjects conditions (Explicit, Enriched, Explicit But Not Relied On). We manipulated both the degree to which the hearer relies on the promise (i.e., whether they are expected to change their course of action under the assumption that the promise is fulfilled), and whether the promise applies its force to an unenriched proposition or not (i.e., whether or not it is fully linguistically encoded).

In the Explicit condition, a speaker makes a promise explicitly, the content of which the hearer will need to rely on. Here, ‘what is meant’ corresponds to ‘what is said’, and ‘what is said’ does not need to be pragmatically enriched. In the Enriched condition, a speaker makes a promise whose content is something the hearer will be likely to rely on. Here ‘what is said’ needs to be pragmatically enriched in order for the listener to recover ‘what is meant’. In the Explicit But Not Relied On condition, a speaker makes an explicit promise, but the exact content of the promise is not something the hearer will be likely to rely on. Here, ‘what is said’ is not relevant to attributions of commitment. Then, in both the Explicit and also in the Explicit But Not Relied On conditions, the speaker who made the promise fails to comply with the explicitly conveyed content. In the Enriched condition, the speaker who made the promise fails to comply with the conveyed content, but does comply with the explicitly uttered content.

In the Enriched condition, the scenarios read as follows:

Scenario A: Jack lent €200 to his friend Ben a couple of months ago. Jack's landlord wants the rent to be paid by the Monday of the next week, and Jack does not have enough money to pay it. So a week before the rent is due, Jack asks Ben to return the money, saying that he wouldn't be able to pay the rent by the Monday deadline otherwise. Ben replies: “Don’t worry, I will definitely pay you back." Ben pays Jack back on Thursday, three days after the rent was due.

Scenario B: Alexis prepares to go on holiday with her family. So she asks around her friends to find someone who will take care of her indoor plants. She tells Bonnie, one of her friends: “I am away for three weeks and I need someone to water my plants.” Alexis explains that the plants should be watered every four to five days, otherwise they will dry out. Alexis tells Bonnie that she needs someone to come to her place at least four times over the course of the three weeks that she’ll be gone for. Bonnie replies: “No problem, I will water them.” When Alexis returns, she checks her alarm systems, which records every time it gets deactivated. According to the alarm system, over the previous three weeks the house was entered once, right in the middle of the three weeks.

In the Explicit condition, the vignette differed only in the addition of words that make the content of the promise explicit – specifically, to “Don’t worry, I will definitely pay you back" is added the words “before Monday”, and to “No problem, I will water them” is added “every four days”. In the Explicit But Not Relied On condition the vignette was based on the Explicit condition, but differed so that the exact explicit promise will not be relied upon – specifically, the vignette was changed so that the rent is due before Friday (rather than Monday) and so that the plants need to be watered only once (see <https://osf.io/zrufe/> for the full vignettes).

After reading the vignette, participants were given two comprehension questions, and three commitment questions. The comprehension questions were designed to check whether the subject was careful enough in reading the story to have grasped the most relevant information in order to properly respond to the target questions. The commitment questions were designed to measure whether the speaker was perceived to have broken a commitment or not. Specifically, the three questions measure: (i) the extent to which the participant believes that the speaker owes the hearer an apology (Apology Required); (ii) the extent to which the participant would, if in the hearer’s position, rely on the speaker in the future (Partner Choice); and (iii) the extent to which the participant believes that the speaker failed to live up to the promise (Violated Promise). For the commitment questions participants indicated, on a 6-point Likert scale, their agreement with some statements about the evaluation of both the situation and the speaker. The responses have been collected on a 6-point scale from 0 (strongly disagree with the statement) to 5 (strongly agree with the statement).

-

Comprehension Question 1: “How much money did Ben borrow from Jack?” (“50 EUR”; “200 EUR”; “400 EUR”) or “How long has Alexis been on holiday?” (“One week”; “Two weeks”; “Three weeks”)

-

Comprehension Question 2: “When did Ben pay the money back (“Monday”; “Thursday”; “Saturday”) or “How many times did Bonnie enter the house?” (“Never”; “Once”; “Four times”)

-

Apology Required: “The speaker owes the hearer an apology”

-

Partner Choice: “If you were the hearer, you would rely on the speaker in the future”

-

Violated Promise: “The speaker failed to live up to their promise”

The comprehension questions and the commitment questions were presented as blocks, in random order. Data from those who failed to answer these questions correctly (N = 33) were discarded from the final sample.

For Apology Required, we predicted that participants would more likely evaluate the speaker as having misbehaved in the Explicit and in the Enriched conditions than in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition, with the additional prediction that there would be no significant difference between the Explicit and the Enriched conditions. For Partner Choice we predicted that participants would more likely exhibit a lower willingness to interact with the speaker in the future in the Explicit and in the Enriched conditions than in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition, with the additional prediction that there would be no significant difference between the Explicit condition and the Enriched condition. For Violated Promise, considering the possibility that people might have a naive intuition of a promise being verbal, we were agnostic about possible differences between the Explicit condition and the Enriched condition. We predicted, though, that participants would perceive a promise being broken significantly more often in the Explicit condition than in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition, despite the fact that the two statements are identical and both falsified.

3.3. RESULTS

To test this hypothesis, we ran a Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test for each variable; additionally, we ran a Mann–Whitney test to check the effect of scenario for each variable. Given that our measures involve ordinal scales, we opted for using appropriate non-parametric tests (Liddell & Kruschke, Reference Liddell and Kruschke2018). All the analyses here and elsewhere were performed using R version 3.4.1.

For Apology Required there is a significant difference in the judgements across the two scenarios [Mann–Whitney W (255) = 6759, p = .014], with significantly more frequent higher rates in Scenario A than in Scenario B. Thus, we ran the analyses for Apology Required on the two groups separately.

In the Scenario A group, a Kruskal–Wallis H test showed a significant difference in the responses to Apology Required [χ 2 (2) = 15.707, p < .001, η2 = 0.13]. A series of post-hoc pairwise comparison tests showed that the rates of agreement are significantly lower (i.e., speaker is less frequently judged to owe the hearer an apology) in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than in the Explicit condition (p < .001). However, no significant difference is found between the Enriched condition and the Explicit condition (p = .09), and between the Explicit But Not Relied On condition and the Enriched condition (p = .09). Here and elsewhere, all p-values were adjusted with the Bonferroni correction for performing three pairwise comparisons. Raw data are illustrated in Figure 1.

Fig. 1: Frequencies of responses for Apology Required in the two scenarios. In Scenario A (N = 121), participants were more likely to judge that an apology was in order in the Explicit condition than in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition, whereas no difference is found between the Explicit condition and the Implicit condition, and between the Implicit condition and the Explicit But Not Relied On condition. In Scenario B (N = 134), participants were more likely to judge that an apology was in order in both the Explicit condition and the Implicit condition than in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition, whereas no difference is found between the Explicit condition and the Implicit condition.

In the Scenario B group, and consistent with the predictions, a Kruskal–Wallis H test showed that there is a statistically significant difference in the responses to Apology Required [χ 2 (2) = 44.102, p < .001, η2 = 0.33]. A series of post-hoc pairwise comparison tests showed that the rates of agreement are significantly lower (i.e., speaker is less frequently judged to owe the hearer an apology) in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than in both the Explicit condition (p < .001), and the Enriched condition (p < .001). However, no significant difference is found between the Enriched condition and the Explicit condition (p = 1.00). These results are consistent with our predictions. Raw data are illustrated in Figure 1.

The effect of scenario on Partner Choice is non-significant, i.e., we found no significant difference in the judgements across the two scenarios, [Mann–Whitney W (255) = 7493.5, p = .272].

Consistent with the predictions, a Kruskal–Wallis H test showed that there is a statistically significant difference in the responses to Partner Choice Question [χ 2 (2) = 48.742, p < .001, η2 = 0.19]. A series of post-hoc pairwise comparison tests showed that the rates of agreement are significantly higher (i.e., speaker is judged to be significantly more reliable) in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than in both the Explicit condition (p < .001) and the Enriched condition (p < .001). However, no significant difference is found between the Enriched condition and the Explicit condition (p = 1.000) (as shown in Figure 2). Raw data are illustrated in Figure 2.

Fig. 2: Distribution of responses (N = 255) for Partner Choice and Perceived Promise. Participants were less willing to rely on the speaker and more likely to judge that promise was not lived up to both in the Explicit condition and the Implicit condition than in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition, whereas no difference is found between the Explicit condition and the Implicit condition.

The effect of scenario on Violated Promise is non-significant, i.e., we found no significant difference in the judgements across the two scenarios [Mann–Whitney W (255) = 8422.5, p = 0.558].

A Kruskal–Wallis H test showed that there is a statistically significant difference also in the responses to Perceived Promise [χ 2 (2) = 40.274, p < .001, η2 = 0.16]. A series of post-hoc pairwise comparison tests showed that the rates of agreement are significantly lower (i.e., the promise is less frequently judged to be broken) in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than in both the Explicit condition (p < .001), and the Enriched condition (p < .001). Furthermore, no significant difference is found between the Implicit condition and the Explicit condition (p = .053). Raw data are illustrated in Figure 2.

3.4. DISCUSSION

Collectively these results support the hypothesis that people take into account pragmatically enriched content when they interpret what the speaker is committing to, and that commitment attribution is modulated by the degree to which the hearer will actually rely on the promise, and not by the degree of its explicitness. However, these results might not hold for all types of pragmatically derived contents. Grice (Reference Grice1989) distinguished Particularised Conversational Implicatures (PCIs) and Generalised Conversational Implicatures (GCIs). PCIs do not contribute to the truth-conditional content of the utterance, typically the explicitly expressed proposition. For instance, in some particular contexts the utterance “The cake looks delicious” would raise the implicature ‘I would like a slice of cake’. GCIs, however, contribute to individuating the truth-condition of a proposition, and therefore some kinds of supposedly implicit content are de facto part of ‘what is said’. For instance, the utterance “I ate some of the cookies” generally raise the implicature ‘I ate some but not all the cookies’. Furthermore, some studies suggest that people distinguish implicatures (PCIs) from other types of pragmatic operations aimed to retrieve the truth-evaluable proposition (GCIs) (e.g., Doran, Ward, Larson, McNabb, & Baker, Reference Doran, Ward, Larson, McNabb and Baker2012).

In the next study, we assess whether speakers are perceived to be committed to PCIs, and not just to GCIs. To do this we modify the kind of implicit content used by the characters, contrasting cases in which the promise is fully linguistically available with cases in which the promise needs to be fully retrieved by the hearer.

4. Study 2

4.1. HYPOTHESIS

Study 2 tests the hypothesis that the degree to which speakers are taken to be committed to a promise is determined not by whether the promise was explicit or not, but by the degree to which the audience relies on the promise. Study 2 thus repeats the general design of Study 1, but contrasts promises made implicitly with those that are explicit.

4.2. METHODS

4.2.1. Participants

We implemented a web-based paradigm with a between-subjects design on an online platform (SurveyMonkey). Based on the effect sizes detected in Study 1, a power analysis using G*Power 3.1 indicated that a total sample size of 270 participants would be needed to detect the expected effect size (f = 0.19) (derived from a predicted statistical power of 80% using a one-way ANOVA with alpha at .05). We added 15% to our desired sample, thus we aimed to collect 310 participants. We included data from all participants who had begun the experiment when SurveyMonkey registered that this number had been reached.

Participants were 310 adults, recruited via Amazon M-Turk. Data was discarded from subjects who did not complete the survey (N = 7) and failed one or more control questions (N = 7), and technical errors (N = 2), leaving 294 subjects (131 females; Mage = 37.02 years, SD = 10.81): 94 in the Explicit condition, 97 in the Implicit condition and 103 in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition. The sample was composed entirely of North Americans. All participants gave their informed consent by ticking a box prior to the experiment.

4.2.2. Stimuli and procedure

Participants were asked to read different hypothetical situations in which a speaker performs a verbal promise, i.e., a commissive speech act, which is later found not to be fulfilled. Subjects were presented with one of the two scenarios presented below, in one of three conditions (Explicit, Implicit, Explicit But Not Relied On) in which the promise is explicit rather than only implied, and in which the relevance of the promise is high rather than low.

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of three between-subjects conditions (Explicit, Implicit, Explicit But Not Relied On).

In the Implicit condition, the scenarios read as follows:

Scenario A: Thomas is planning to invite some of his friends to a home party. He says to his friend James: “I am throwing a party next Saturday at home. Do you have time to join? It’ll be a potluck lunch, so everybody brings something to share. Nobody shows up empty-handed!” James replies: “Sure, I’ll be there!” At the party, James does not bring any food along.

Scenario B: Andrea is working on her Master’s thesis and the final draft is almost done. Because Andrea is not a native English speaker, she asks another student, Jen, to proofread the draft. She asks: “Can you help me out and check my writing? I’ll have to hand in my thesis in three days.” Jen answers: “I have some free time tomorrow.” Andrea receives the proof-read document from Jen four days later, one day after her deadline.

In the Explicit condition, the vignette differed only to the extent that the implied information was now explicitly uttered: “I’ll bring some food" (“I’ll read it then”). In the Explicit But Not Relied On condition the vignette was based on the Explicit condition, but differed so that the explicit promise will not be relied upon -- specifically, the vignette was changed so that satisfying the statement “I’ll bring some food" (“I’ll read it then”) would be irrelevant for the hearer – as in Scenario A the speaker makes clear there will be food for everyone, and in Scenario B the thesis deadline is still two weeks ahead (see <https://osf.io/zrufe/> for the full vignettes).

As in Study 1, after reading the vignette, participants were asked to indicate their agreement with some statements. We measured whether the speaker was perceived to have broken a commitment or not. The responses have been collected on a 6-point Likert scale from 0 (strongly disagree with the statement) to 5 (strongly agree with the statement).

The commitment measures were the same as in Study 1. We again controlled for participants’ understanding of the text by asking two comprehension questions (see <https://osf.io/zrufe/>). Both the comprehension questions and the commitment measures were always presented in a randomised order. Responses from those who failed to answer this question correctly were discarded from the final sample (N = 7).

4.3. RESULTS

To test this hypothesis, we ran a Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test for each variable; additionally, we ran a Mann–Whitney test to check the effect of scenario for each variable.

The effect of scenario on Apology Required is non-significant, i.e., we found no significant difference in the judgements across the two scenarios [Mann–Whitney W (293) = 10432, p = .65].

Consistent with the hypothesis, a Kruskal–Wallis H test showed a significant difference in the responses to Apology Required [χ 2 (2) = 124.85, p < .001, η2 = 0.43]. A series of post-hoc pairwise comparison tests showed that the rates of agreement are significantly lower (i.e., speaker is less frequently judged to owe the hearer an apology) in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than in the Explicit condition (p < .001). However, no significant difference is found between the Implicit condition and the Explicit condition (p = .09), and between the Explicit But Not Relied On condition and the Implicit condition (p = .09). Raw data are illustrated in Figure 3.

The effect of scenario on Partner Choice is non-significant [Mann–Whitney W (293) = 12066, p = .062].

Consistent with the predictions, a Kruskal–Wallis H test showed that there is a statistically significant difference in the responses to Partner Choice Question [χ 2 (2) = 83.896, p < .001, η2 = 0.29]. A series of post-hoc pairwise comparison tests showed that the rates of agreement are significantly higher (i.e., speaker is judged to be significantly more reliable) in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than in both the Explicit condition (p < .001) and the Implicit condition (p < .001). However, no significant difference is found between the Implicit condition and the Explicit condition (p = 1.000) (as shown in Figure 2). Raw data are illustrated in Figure 3.

Fig. 3: Distribution of responses (N = 294) for Study 2. As can be seen, participants were more likely to judge that an apology was in order and that the speaker was unreliable in the Implicit and in the Explicit conditions than in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition, whereas no difference is found between the Explicit condition and the Implicit condition. However, participants were more likely to judge that promise was not lived up to in the Explicit condition than in the other two conditions, and more likely to judge the same in the Implicit condition than in the Explicit but Not Relied On condition.

The effect of scenario on Violated Promise is non-significant [Mann–Whitney W (293) = 12048, p = .06].

A Kruskal–Wallis H test showed that there is a statistically significant difference also in the responses to Perceived Promise [χ 2 (2) = 78.802, p < .001, η2 = 0.27]. A series of post-hoc pairwise comparison tests showed that the rates of agreement are significantly lower (i.e., the promise is less frequently judged to be broken) in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than in both the Explicit condition (p < .001), and the Implicit condition (p < .001). A significant difference is found also between the Implicit condition and the Explicit condition (p = .046). Raw data are illustrated in Figure 3.

4.4. DISCUSSION

Collectively these results support the hypothesis that, with regards to commitments, there is no principled or qualitative distinction between explicit and implicit communication.

The one finding that was not replicated concerns the perception of a violation of a promise; while in Study 1 the pragmatically enriched content was taken into account in the assessment of the promise (with no significant differences between the Explicit and the Implicit conditions), in Study 2 the pragmatically inferred content was less taken into account by participants (they were more likely to judge the promise as violated in the Explicit condition than in the Implicit condition).

In order to increase the robustness and generalise our results, we ran another study, effectively a conceptual replication of the previous study, using a different type of stimuli.

5. Study 3

5.1. HYPOTHESIS

As did Study 2, Study 3 also tests the hypothesis that the degree to which speakers are taken to be committed to a promise is determined not by whether the promise was made explicitly or not, but by the degree to which the audience relies on the promise. Study 3 replicated the design of Study 1 and 2, but differed in the following respects: (i) differently to Study 1, the kind of implicit content used is a conversational implicature (a PCI); and (ii) we presented participants with video-clips and comic strips rather than with written scenarios. This increases the ecological validity of the situation, and underlines the mutual manifestness of the fact that the hearer relies on the promise, by creating a clearly perceptible case of joint attention (Carpenter & Liebal, Reference Carpenter, Liebal and Seeman2011) rather than relying on explicit verbal description of the agents’ epistemic stances.

5.2. METHODS

5.2.1. Participants

We implemented a web-based paradigm with a between-subjects design on an online platform (SurveyMonkey). Based on the effect sizes detected in Study 1, a power analysis using G*Power 3.1 indicated that a total sample size of 270 participants would be needed to detect the expected effect size (f = 0.19) (derived from a predicted statistical power of 80% using a one-way ANOVA with alpha at .05). We added 15% to our desired sample; thus we aimed to collect 310 participants. We included data from those participants who had already begun the experiment when SurveyMonkey registered that this number had been reached.

Participants were 346 adults, recruited via Amazon M-Turk. Data was discarded from subjects who did not complete the survey (N = 19) and failed one or more control questions (N = 17) leaving 310 subjectsFootnote 2 – 102 in the Explicit condition, 125 in the Implicit condition, and 88 in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition. The sample was composed entirely of North Americans. All participants gave their informed consent by ticking a box prior to the experiment.

5.2.2. Stimuli and procedure

Participants were asked to read and watch different hypothetical situations involving a potential violation of a promise. Subjects were presented with one of the two scenarios described above, in one of three conditions (Explicit, Implicit, Explicit But Not Relied On) in which the promise is explicit, or only implied, and in which the relevance of the promise is high rather than low.

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of three between-subjects conditions (Explicit, Implicit, Explicit But Not Relied On). The scenario is presented to be read as if the events occurring in the scenario were true.

In the Implicit condition, the scenarios were shown as follows:

Scenario A: in a black-and-white short video-clip, X and Y are having a chat at a café and at some point X mentions that he needs to go to the restroom. He points at his laptop on the table and looks at Y. Y states: “You can leave it here.” When X comes back from the restroom, the laptop is on the table unattended while Y is chatting with another person.

Image 1: Extracts from the video-clip, Implicit Condition (Scenario 2A).

Scenario B: in a comic strip, X and Y are planning to go home from the office. After crossing a hallway where some free umbrellas are available to be borrowed, X and Y notice that it is raining. While X is about to fetch the umbrellas, Y stops him, stating that: “I am gonna fetch something.” When Y comes back, he only has one umbrella.

Image 2: Extracts from the video-clip, Implicit Condition (Scenario 2B).

In the Explicit condition, the vignette differed only to the extent that the implied information was now explicitly uttered: “I’ll keep an eye on it” (“I am gonna fetch two umbrellas”). In the Explicit But Not Relied On condition, the vignette was based on the Explicit condition, but differed so that the explicit promise will not be relied upon – specifically, the vignette was changed so that satisfying the statement (“I’ll keep an eye on it”; “I am gonna fetch two umbrellas”) would be irrelevant for the hearer – as in Scenario A there were two other friends keeping an eye on the laptop at the table,Footnote 3 and in Scenario B X and Y would leave the building together, so one umbrella would be enough for them not to get wet (see <https://osf.io/zrufe/> for the full vignette).

As in Study 1 and 2, after reading the vignette, participants were asked to indicate their agreement with some statements. We measured whether the speaker was perceived to have broken a commitment or not. The responses have been collected on a 6-point Likert scale from 0 (strongly disagree with the statement) to 5 (strongly agree with the statement).

The commitment measures were the same as in Study 1 and 2. We again controlled for participants’ understanding of the text by asking two comprehension questions (see <https://osf.io/zrufe/>). Both the comprehension questions and the commitment measures were always presented in a randomised order. Responses from those who failed to answer this question correctly were discarded from the final sample (N = 17).

5.3. RESULTS

We first checked whether the scenario we presented significantly influenced participants’ responses. For all three measures there is a significant difference in the judgements between the two scenarios. There is a significant difference in the responses to Partner Choice across the two scenarios [Mann–Whitney W (310) = 7806, p < .001], with significantly higher rates in Scenario B than in Scenario A. There is a significant difference in the responses to Apology Required across the two scenarios [Mann–Whitney W (310) = 16857, p < .001], with significantly higher rates in Scenario A than in Scenario B. Finally, there is a significant difference in the responses to Perceived Promise across the two scenarios [Mann–Whitney W (310) = 17376, p < .001], with significantly higher rates in Scenario A than in Scenario B.

Since the scenario played a role in the formation of the judgements, we decided to run the analysis for the two scenarios independently, despite the loss of statistical power. We therefore considered the data from the first scenario as Study 3A (N = 153), and the data from the other scenario as Study 2B (N = 157).

5.3.1. Results of Study 3A

To test this hypothesis, we ran a Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test for each variable.

Consistent with the predictions, a Kruskal–Wallis H test showed that there is a statistically significant difference in the responses to Apology Required [χ 2 (2) = 6.291, p = .043, η2 = 0.04]. However, a series of post-hoc pairwise comparison tests showed a non-predicted pattern: the rates of agreement are significantly lower (i.e., speaker is less frequently judged to owe the hearer an apology) in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than in the Implicit condition (p = .043), but not than in the Explicit condition (p = .257). As predicted, no significant difference is found between the Implicit condition and the Explicit condition (p = 1.000). Raw data are illustrated in Figure 4.

Contrary to the predictions, a Kruskal–Wallis H test showed that there is no statistically significant difference in the responses to Partner Choice [χ 2 (2) = 0.944, p = .624]. Raw data are illustrated in Figure 4.

Fig. 4: Distribution of responses (N = 153) for Study 3A. As can be seen, participants were more likely to judge that an apology was in order in the Implicit condition than in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition, whereas no difference is found between the Explicit condition and the Implicit condition and between the Explicit condition and the Explicit But Not Relied On condition. No difference is found between the three conditions for Partner Choice and for Perceived Promise.

A Kruskal–Wallis H test showed that there is no statistically significant difference in the responses to Perceived Promise [χ 2 (2) = 4.155, p = .125]. Raw data are illustrated in Figure 4.

5.3.2. Results of Study 3B

Similarly to the previous study, to test our hypothesis, we ran a Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test for each variable.

Consistent with the predictions, a Kruskal–Wallis H test showed that there is a statistically significant difference in the responses to Apology Required [χ 2 (2) = 44.569, p < .001, η2 = 0.29]. A series of post-hoc pairwise comparison tests showed that the rates of agreement are significantly lower (i.e., speaker is less frequently judged to owe the hearer an apology) in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than in the Explicit condition (p < .001), and in the Implicit condition (p = .006). Contrary to the previous finding, a significant difference is found between the Implicit condition and the Explicit condition (p < .001). Raw data are illustrated in Figure 5.

Fig. 5: Distribution of responses (N = 157) for the three measures in Study 3B. As can be seen, participants were more likely to judge that an apology was in order in the Explicit than in the other two conditions, and they were more likely to make this judgement in the Implicit condition than in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition; they would be more willing to rely on the speaker in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than in the other two conditions, whereas no difference is found between the Explicit condition and the Implicit condition; and finally they were more likely to judge that the promise was not lived up to in the Explicit condition than in the other two conditions, and they were more likely to judge that the promise was not lived up to in the Explicit But Not Relied On than in the Implicit condition.

Consistent with the predictions, a Kruskal–Wallis H test showed that there is a statistically significant difference in the responses to Partner Choice, [χ 2 (2) = 52.596, p < .001, η2 = 0.38]. A series of post-hoc pairwise comparison tests showed that the rates of agreement are significantly higher (i.e., speaker is judged to be significantly more reliable) in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than both in the Explicit condition (p < .001) and the Implicit condition (p < .001). However, no significant difference is found between the Implicit condition and the Explicit condition (p = .28). Raw data are illustrated in Figure 5.

A Kruskal–Wallis H test showed that there is a statistically significant difference in the responses to Perceived Promise [χ 2 = 46.291, p < .001, η2 = 0.30]. A series of post-hoc pairwise comparison tests shows that the rates of agreement are significantly lower (i.e., a promise is less frequently judged to be broken) in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than in the Explicit condition (p < .001), but significantly higher (i.e., the promise is more frequently judged to be broken) than in the Implicit condition (p = .007). Consequently, a significant difference is found between the Implicit condition and the Explicit condition (p < .001). Raw data are illustrated in Figure 5.

5.4. DISCUSSION

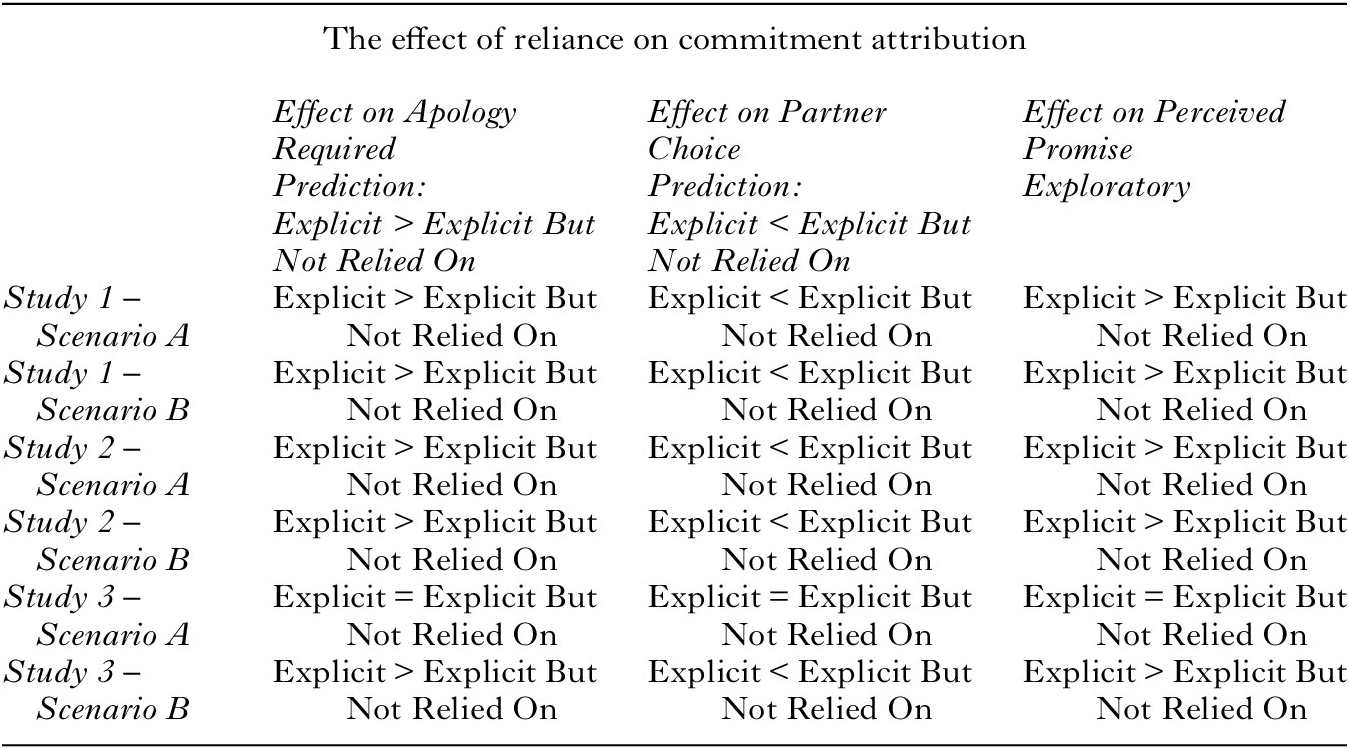

These results corroborate the results of Study 1 and Study 2 (see Table 1 and Table 2 for summary).

TABLE 1. Summary of the results of our studies. Our three measures mostly show no differences between how people treated explicit and implicit commitments across the six scenarios

TABLE 2. Summary of the results of our studies. Our three measures mostly show differences between how people treated Explicit Relied On and Explicit But Not Relied On commitments across the six scenarios

In Study 3A, as with Study 2, participants’ responses to the commitment questions were not significantly different in the Explicit condition and in the Implicit condition, as predicted (see Table 1). On the other hand, contrary to Study 2, we did not find the predicted difference between the Explicit condition and the Explicit But Not Relied On condition (see Table 2). Rather than reject our hypothesis outright, we reason that the vignette suffers from a lack of salience in the critical difference between these two conditions. Specifically, the presence of additional people at the same table might not have been enough to release the speaker from looking after the laptop, thus (contrary to the intended manipulation) not decreasing the relevance of the promise “I will keep an eye on it”. The importance of the tool, of course, increases the type of assurance needed, while the additional people at the table did not offer any. This would mean that de facto there was no difference in the relevance of the promise or in the wording between the Explicit condition and the Explicit But Not Relied On condition.

In Study 3B, as with Study 1 and 2, we found that breaking a commitment when the hearer relies on the promise has reputational consequences on the violator, and, as with Study 2 and in Study 3A, this is true regardless of whether the promise was made implicitly or explicitly. Speakers were judged to be significantly more reliable in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than in the other two conditions, whereas no difference was found between the Implicit condition and the Explicit condition.

We also found that, contrary to Study 1 but consistently with Study 2, whether the promise was made implicitly or explicitly affected the responses to Apology Required and Perceived Promise questions. On the one hand, speakers were judged to owe the hearer an apology significantly less frequently in the Explicit But Not Relied On condition than in the other two, but also less frequently in the Implicit condition than in the Explicit condition; on the other hand, as in Study 2, the perception of a promise was affected by it being explicitly uttered.

6. General discussion

In general our experimental results align with our theoretical points (Section 2). Specifically, we found that breaking a commitment when the hearer relies on the promise has reputational consequences for the communicator regardless of whether it is explicitly said or implicitly meant, but not otherwise. Furthermore, reliance on the promise often decisively influenced participants’ judgements about whether an apology was necessary or appropriate. Across all our studies people tended to not perceive that a promise that was not relied on (e.g., the implied promise ‘I will read it tomorrow’ in the case where the deadline is in two weeks) had even been broken. (The one exceptional finding was that most participants in Study 2 and Study 3B, in cases in which the promises were relied on (e.g., the promise ‘I will read it tomorrow’ in the case where the deadline is the day after tomorrow), evaluated the promise primarily taking into account ‘what is said’ (in line with Saul, Reference Saul2012). One possibility is that, compared to Study 1, Study 2 and Study 3B in fact implements a conversational implicature (a GCI rather than a PCI; see Section 3.4), thus changing perception of what has in fact been said (see Doran et al., Reference Doran, Ward, Larson, McNabb and Baker2012).

In sum, our results suggest that audiences take speakers to be committed to ‘what is meant’ rather than ‘what is said’ (see below for comments on the generality of this finding). More broadly our findings align with theories of commitment based on social expectations (e.g., MacCormick & Raz, Reference MacCormick and Raz1972; Scanlon, Reference Scanlon1998; Sugden, Reference Sugden, Nida-Rümelin and Spohn2000; for experimental support see also Bonalumi, Isella, & Michael, Reference Bonalumi, Isella and Michael2019), and they speak against theories which argue that commitments derive from conventions and social practices (e.g., Austin, Reference Austin1962; Rawls, Reference Rawls1971; Searle, Reference Searle1969).

These findings raise the interesting question of whether there is a folk concept of promise, tied to ‘what is said’ rather than to ‘what is meant’. There is a small amount of experimental research on the folk concept of lies, which shows that evaluations of whether a lie was uttered does indeed depend on what was meant rather than what was said (Weissman & Terkourafi, Reference Weissman and Terkourafi2019; Wiegmann, Samland, & Waldmann, Reference Wiegmann, Samland and Waldmann2016; Willemsen & Wiegmann, Reference Willemsen, Wiegmann, Gunzelmann, Howes, Tenbrink and Davelaar2017; and see Meibauer, Reference Meibauer2018). However, there is not (to our knowledge) any existing experimental research directly focused on the folk concept of promise, and we view this as a productive avenue for future enquiry. Note, incidentally, that if folk intuitions about promises are indeed tied to ‘what is said’, that creates space for speakers to deny having meant what was only implicitly communicated by invoking this folk belief, and hence to avoid commitments that they might otherwise be held to (Lee & Pinker, Reference Lee and Pinker2010).

We conclude with some remarks about the potential generality of our findings. Folk intuitions about promises and lies – not to mention other aspects of communication also – are likely to vary between cultures, and maybe within them too. In particular, it is possible that WEIRD societies (Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, Democratic) will place greater emphasis on what is said, given the history and prevalence of institutions based on what has been made explicit, such as legal systems, formal contracts, and others. Future cross-cultural research could explore this hypothesis. At the same time, we expect, looking under the surface of folk intuitions, that commitment to ‘what is meant’ rather than ‘what is said’ will not exhibit too much variation, either within or between cultures. This is because the underlying cognitive processes involved in communication and commitment attribution are part of the ordinary and robustly developing human cognitive phenotype, which includes an inter-related suite of processes for the expression, recognition, and epistemic evaluation of intentions (Levinson, Reference Levinson2006; Scott-Phillips, Reference Scott-Phillips2015; Sperber et al., Reference Sperber, Clément, Heintz, Mascaro, Mercier, Origgi and Wilson2010; Wilson & Sperber, Reference Wilson and Sperber2012).