“The Indian […] is raw material in the mountain and plain to be brought and put through the proper refining influences of our civilization mills of today, wrought into shape and then sent to work on the great oceans of our industry and thrift.”

— Richard Henry PrattFootnote 1

“The majority of men and women are hopelessly treading Drudgery mills and that is civilization?—To be compelled to work when you do not wish it—is drudgery—not civilization! That is about what Carlisle would gain in the end—success in making drudges. I prefer to be stone-dead than living-dead!”

— Zitkala-ŠaFootnote 2

In 1882, when he was around 12 years old, Luther Standing Bear (Oglala Lakota) was brought by his schoolmaster to a “big hall” to serve as entertainment for an audience of white visitors to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. In one of his several memoirs written decades later, Standing Bear describes singing a “love-dance song” at the request of Carlisle founder “Captain” Richard Henry Pratt, to the great pleasure of the audience. A man who “looked like Santa Claus” then requested to hear an oration “in the Sioux tongue.” Standing Bear describes,

Now in school we were not allowed to converse in the Indian tongue, but here was an old man making a formal request which Captain Pratt did not wish to refuse. […] I arose and said, “Lakota iya woci ci yakapi queyasi oyaka rnirapi kte sni tka le ha han pe lo,” which, interpreted into English, means, “If I talk in Sioux, you will not understand me anyhow.” But I did not understand exactly how to interpret this properly at the time, so I was pleased when there was a clapping of hands, so I could sit down again. Just then the old man stood up again, and while I was shivering in my shoes for fear of what he might again ask me, he said “Can that boy interpret what he said into English?” I knew I had to say something, so I replied that it meant, “We are glad to see you all here to-night.”Footnote 3

This episode, one of many rich first-hand stories Standing Bear recorded of his life navigating the Federal Indian Boarding School system from its watershed moment in 1879, points to the complexities of signification, performance, and contestation that subtended the assimilationist education program writ large.Footnote 4 On the surface, Standing Bear's story reveals what Stó:lō musicologist Dylan Robinson has theorized as the insatiable settler “hunger” for Indigenous aural and performance cultures and knowledges—one always attended by a hunger for land.Footnote 5 On a deeper level, it shows Standing Bear playing with white aural expectations and navigating complex and dissonant domains of signification, making meaning for himself and his peers to which the white audience is oblivious. If Standing Bear's narrative bears witness to the degradation to which young Native people were subjected at Carlisle, it also shows how those same people brought their own complex strategic engagements to their circumstances, playfully inverting performance expectations to make their own way within hostile circumstances.

The complex mediations and conflictual meanings embedded in this passage provide a model for this article's investigation of the broader significance of music at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, the institution at the center of the boarding school system that Red Lake Ojibwe historian Brenda Child has suggested is representative of settler colonialism “at its most genocidal.”Footnote 6 Scholars of Indigenous North American history have long understood the boarding school system not simply as a humanistic “civilizing” mission (itself a thinly veiled cultural assault on Native children), but just as crucially as a way of structurally undermining Native tribal and political blocs in order to facilitate the state dispossession of Native land.Footnote 7 Land and territory, as Lenape theorist Joanne Barker and many others have argued, is “not anecdotal but formative” to the colonial processes on which settler nations like the United States are founded, and the question of land subtends the longue durée of colonial and early-U.S. policy toward Native peoples, including the boarding school era.Footnote 8 Thus, this article builds off of Indigenous studies scholars’ insistence on the centrality of land to the history of settler-colonial governance, as well as musicological scholarship on the role of music in the experiences and policies of the assimilation era, to ask how music in carceral and assimilationist institutions played into larger processes of land dispossession. I argue ultimately that, although federal policies that suppressed Native music and dance in reservation life and imposed Euro-American music at boarding schools were part of the broader field of governance that tried to break up Native communities and undermine relationships to their land bases, the actual practices of music and performance at Carlisle and other institutions of carceral assimilation provided the sparks of mutual recognition, solidarity, and sociality among students of a wide range of backgrounds. Assimilationist cultural policy thus paradoxically contributed to the development of nascent forms of intertribal political and social formations that would guide Native music practices and self-determination movements in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

I aim to contribute to the historiographic understanding of U.S. American settler colonialism and the role of music and expressive culture within that broader structure, while also modeling deep intellectual engagement with the Indigenous scholarship that continues to lead the scholarly discourses around music, colonialism, and Indigeneity. Of course, my positionality as a white settler scholar bears on how I approach this question.Footnote 9 My method is therefore not to pretend to speak from an embodied or privileged knowledge of the complex meanings of musicking for Indigenous communities; rather, I assemble critical readings of settler discourses and policies using the conceptual tools developed in Indigenous critiques of colonialism. By reading the settler archive against the grain, I hope to make the dispossessive machinations of colonial culture more apparent, offering discussions that could be seen as complementary to those Indigeneity-centered music historiography and analysis that orient the anticolonial critique of contemporary music studies. In short, I take seriously the provocations of musicologists Jessica Bissett Perea (Dena'ina) and Gabriel Solis, who ask the question, “what happens to American music studies if you put Indigeneity at its center?”Footnote 10 Furthermore, this article's central theoretical concern—a consideration of the politics of music under settler colonialism as inextricable from the material geopolitics of land—is meant to contribute to the increasing urgency of debates around “decolonizing” music studies by taking seriously Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang's now-standard insistence that “decolonization is not a metaphor.”Footnote 11 Hidden behind debates about decolonizing music studies is a seldom-investigated set of questions about what music and land (i.e., the material basis of decolonization) have to do with each other. May the following discussion help sharpen some of those questions.Footnote 12

The boarding school system in context

Established in the Susquehanna Valley in central Pennsylvania by Brigadier General Richard Henry Pratt in 1879, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School was the flagship federal off-reservation boarding school for the compulsory education for Native children.Footnote 13 Over the school's 39 years of existence, thousands of young Native people were brought from their communities across the continent and beyond, ostensibly in order to be assimilated into U.S. American society. Carlisle transformed federal policy on Native education, setting the course for hundreds of other federally operated boarding schools across the United States and Canada.Footnote 14 Notwithstanding the school's official messaging, which touted a humanistic, sentimentalist, and philanthropic mission of “civilizing” Native children, the racial discourses and suppressive practices of the school show the more fundamentally violent and geopolitical function of the boarding school system. The explicit goal of the Carlisle School was to “Kill the Indian and Save the Man”: A motto that encapsulates the way the supposed civilizational mission of the schooling system hardly masked the actual corporeal and cultural violence it enacted.Footnote 15

The off-reservation boarding school system was introduced as an improvement on existing federal policy in two ways: First, Carlisle founder Richard Henry Pratt sought to improve upon the existing institutions of colonial education, including the day schools, mission schools, and on-reservation boarding schools. Against the bilingualism of many of the mission schools and the proximity to home communities offered by the day and on-reservation boarding schools, Pratt argued that these institutions would fail to fully assimilate Native children because they allowed some measure of inclusion of the students’ cultures, languages, and lifeways.Footnote 16 Second, the emergence of the humanistic discourse of Carlisle was meant as a transformation of the federal government's stance toward Native peoples away from the outright military violence that characterized settler-colonial expansion earlier in that century.Footnote 17 This supposedly gentler, sentimental approach to Indigenous peoples was encapsulated by Ulysses S. Grant in his 1869 inaugural address, which called for the “proper treatment of the original occupants of this land,” favoring “any course toward them which tends to their civilization and ultimate citizenship.”Footnote 18 To understand Carlisle and the program it launched as a part of the broader policy reforms at the time means understanding it as a continuation of the violent processes of dispossession and domination by other, only superficially more “enlightened,” means. In this way, the boarding school system went hand-in-hand with the parallel legislative process known as allotment, which imposed Euro-American property and landholding patterns onto Native peoples by turning communally held tribal lands into individual parcels of private property—in the process, making much of that newly private land available for property tax foreclosure and dispossession by predatory settler venture. Consolidated in the 1887 General Allotment (or Dawes) Act, the allotment process was draped in the same ideological cloth as the boarding school system, enforcing the belief, in the words of Daniel Heath Justice (Cherokee) and Jean M. O'Brien (White Earth Ojibwe), that “the privatization of land is a necessary precondition for individual success and cultural modernity.”Footnote 19 The centrality of the schooling system in this new ideology of assimilationist progressivism in settler-colonial society is encapsulated by the well-known allegorical painting American Progress, in which Columbia, the mythical personification of the United States, glides frictionlessly to the West, spreading civilization in the form of railroads and telegraph wire, trampling Native peoples underfoot. Nested in Columbia's right arm is a “School Book”Footnote 20 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. John Gast, American Progress, 1872.

This article proceeds in five sections: First, I discuss the important precursors to Carlisle in Pratt's educational experiments with Native prisoners at Fort Marion, a military fortress in St. Augustine, Florida. The prominent role of arts, crafts, and performance for the broader ideological mission of the Fort Marion experiment laid the groundwork for the aesthetic discourse of Carlisle and the assimilation era more broadly. The second section provides an overview of the role of music in the daily life of the students at Carlisle, from the sonic regimentation of time by bells and prayers to the extracurricular ensembles that students formed. In the third section, I elaborate the aforementioned argument on the role of music at the schools as inextricable from the changing dynamics of land by examining assimilation-era state discourse on music and dance in light of contemporary Indigenous sound and music studies scholarship. I then turn to a discussion of The Captain of Plymouth, a Savoy-esque comic opera performed by students during commencement weekend in 1909, showing how the opera's supposed “civilizing” function failed on its own terms. I conclude by meditating on the operatic text's striking inclusion of a “Ghost Dance,” interpreting this resolutely anti-assimilationist reference within the assimilationist text as a kind of flashpoint for new sparks of intertribal solidarity among the young people who performed it.

Spectacle and the origins of the boarding school system: Fort Marion Prison

In 1875, Richard Henry Pratt was charged with overseeing the transportation of seventy-two prisoners of war from the Central Plains—mostly Kiowa, Comanche, and Cheyenne—over 1,000 miles from Fort Sill in the Oklahoma Territory to Fort Marion, a military prison in St. Augustine, Florida.Footnote 21 At Fort Marion, Pratt subjected his prisoners to forced labor (including in the exhumation of Indigenous burial sites in Florida) and experimented with “educating” them in English and the ways of U.S. American civilization.Footnote 22 He would go on to model his institution in Carlisle, Pennsylvania on his experiments at Fort Marion, including the central importance of public performances by prisoners as part of their “civilization.” Art and cultural performance played an important part in constructing the highly mediated relationship between the prisoners and the townspeople of St. Augustine. The prison was well-known as a “hive of artistic creativity,” and the visual works produced by Bear's Heart (Cheyenne) and other ledger artists there have long been appreciated as a kind of counter-archive visualizing the experience of forced transportation and imprisonment.Footnote 23 In addition to the visual artworks, Pratt curated performances of dances and songs from Central Plains Native communities in strictly controlled environments, supposedly in an effort to help ameliorate white “religious and race hatred” against Native people.Footnote 24 In the 1870s, settler fascination with (usually highly decontextualized and constructed versions of) Native expressive culture was on the rise, and Pratt capitalized on this desire, with the nominal purpose of smoothing over the tensions that his social experiment had created in the town, but also to win support for his endeavors and advance his career as an educator and/as jailer.

Figure 2 shows the Kiowa prisoner Etahdleuh Doanmoe's depiction of an Omaha dance for the townspeople of St. Augustine. The performance, out of context and under conditions of extreme coercion, of this and other Native dances must be regarded in light of the ongoing assault from the Office of Indian Affairs on the autonomy of Native communities on reservations to participate in their dance cultures. Although dances like the Sun Dance and the Omaha Dance complex were not officially outlawed until the 1880s, Pratt's sanctioned curation of otherwise discouraged performances by prisoners of war as entertainment for white audiences strikingly reveals the contradictory power of spectacle.Footnote 25 Upon close inspection, one is struck by the layers of reality and artifice in Doanmoe's representation: Notice how the ground on which the dance occurs extends, proscenium-like, from the wall of the prison, as if it is a mere simulation of the land to which the dance is indigenous. The alignment between the smoke from the central fire and the prison watchtower, as well as the visual continuity between townspeople and the fortress windows, adds to the dissonance between the dance itself and its surroundings. Unsurprisingly, it is the dancers that animate the image, in bright colors and fluid motion against the backdrop of stationary spectators. It is also notable that, though it apparently depicts the culturally specific Omaha Dance, this scene shows a cultural practice being shared by members of related but distinct Plains peoples. Despite Pratt's dismissive description of the dance as given for the prisoners’ “new friends”—and only secondarily “to amuse themselves”—perhaps we can see in Doanmoe's drawing a spark of creative, intertribal sociality under captivity, a theme to which I will return below.

Figure 2. Etahdleuh Doanmoe, “Omaha Dance at St. Augustine,” c. 1877. Box 32, Richard Henry Pratt Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New Haven, CT.

It was the musical performances outside the prison walls that shaped the course of the captives’ lives and the future of colonial education programs. In March of 1878, Pratt programmed a night of entertainment intended to secure funds for the continuing education of several of the prisoners. The evening was so popular that Pratt offered a repeat performance the next night (see Figure 3). By providing a pageant of variety entertainment, Pratt hoped to garner philanthropic support from the elite Euro-Americans visiting St. Augustine for the winter. The performance of “war whoops” and “love songs” for the audience of mostly well-to-do white women made such an impression that Pratt received multiple offers for the philanthropic sponsorship of the prisoners’ educations. At the same concert, women from St. Augustine put on a “Mother Goose” number with both their own white children as well as “decorated Indians.” This gesture of maternalistic incorporation resonated with sentimentalist racialism of the era by performatively casting Native peoples in general as the “children” of the white race, to be “lifted…into their rightful place as real potential Americans.”Footnote 26 This episode shows one form of racism replacing another: By displaying the prisoners as emotive, child-like, and ultimately improvable objects of white sympathy, these performances were designed to counteract the perceptions of Native peoples as barbaric and warlike, thereby securing philanthropic support for their assimilation.

Figure 3. Box 30, Folder 828, Richard Henry Pratt Papers WA MSS S-1174, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

The pageant, which also contained “a talk in the Indian sign language” translated by Tsait-Kope-Ta but not listed on the program, was celebrated by Pratt as a great success. As a direct result of this performance, the captives at Fort Marion were sent away to be educated after their official release from prison.Footnote 27 It won favor among the white elites in St. Augustine, earning sponsorship and placement in northern schools for several of the performers, including Etahdleuh Doanmoe and Tsait-Kope-Ta.Footnote 28 It also set an important course for how spectacle and performance could be used as a frame for what Chickasaw scholar Jodi Byrd has called “paradigmatic Indianness”: The wordless “war song” and the “love song” in the unfamiliar Kiowa language, for example, surely titillated the spectators with the alluring display of a sanitized otherness.Footnote 29 However, it also demonstrates how even the fetishizing construction of spectacular “Indianness” could never fully annul the agency and experience of the performers: The love-song's raucous popularity, the ambiguous lyrics in the final song, and the opportunity to perform a war song in such a restrictive context must, at minimum, have stirred a wider range of reactions among the performers than mere acquiescence to U.S. American civilization. Indeed, even the stated desire of certain prisoners to get an education in settler-operated schools was itself a strategic negotiation with the terms of their incarceration. Some of the prisoners actively sought education simply because they saw it as a more dynamic and capacious opportunity than their brute confinement in a military fortress.Footnote 30 Thus, even though Pratt would describe this evening of “pleasing entertainment” as evidence of the success of the white civilization program, the captives’ performance itself, at least insofar as it led to their emancipation and opportunities for further negotiation of settler society, must have been seen as a success for something quite different.

Music in daily life at Carlisle

As a result of what was hailed as the great success of the Fort Marion experiment, several prisoners were released in 1878 into the official care of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Rather than send the men back to their home communities, Pratt arranged to have some of them sent to the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute to receive “white education” alongside formerly enslaved people and their children. Due in part to his ideological differences with Hampton founder Samuel Chapman Armstrong, Pratt immediately began soliciting the federal government and east coast elites for financial and political support for a school specifically for the education of Native children.Footnote 31 He was soon given access to a decommissioned barracks and transported the first group of students from Pine Ridge and Rosebud Agencies to Carlisle in October of 1879.Footnote 32

Like at Fort Marion, the musical activities at Carlisle were central to its processes of subjection. These activities took a number of different forms, most prominently the music and arts classes that all students would attend at some point in their time at the school. The extracurricular school bands were also a source of pride for many students and for the school officials themselves. There were also occasional concerts at the school, both by live bands and on gramophone, that played a large part in the school's official leisure activities.Footnote 33 Music and sound were operationalized in the highly regulated social life of the Carlisle School both in terms of content and form. The lyrical content of the musical materials themselves expressly communicated messages of national pride, racializing stereotypes, and the middle-class liberal values into which the students were supposed to be indoctrinated. Whether mealtime hymns celebrating Christian meekness, jingoistic songs narrating the bravery of the founding fathers, or school songs designed to simulate the consent of the children to give up their identity, the music at Carlisle was more often than not chosen for its explicitly assimilation-friendly message. The form of musical training provided an equally important, albeit more implicit, arena for racializing aesthetic education.Footnote 34 By “form” I mean not only the semiotic codes of “Western” (Euro-American) music, including harmonic, orthographic, structural, and performance norms (which themselves can carry a kind of “colonizing force,” as Kofi Agawu has arguedFootnote 35), but also the form of wider curricular design through which the school imposed a version of settler musical culture as a leisure activity separable from and secondary to the labor-oriented core of U.S. American life.

Therefore, it is important to consider not just the semiotic content but the institutional and bodily “relations of production” that governed the musical program at Carlisle.Footnote 36 This division also highlights the problem of the epistemic clash at the heart of the education program. Although K. Tsianina Lomawaima (Mvskoke/Creek) and Teresa L. McCarty have emphasized the early stages of the assimilationist curriculum as essentially an “erase and replace” model of re-education, we should be attentive to the hidden epistemic violence of making commensurable what was erased and what it was replaced with.Footnote 37 It is not just that Native cultural repertory was simply suppressed and replaced with a Euro-American one: It is also that the assimilationist education program imposed a universalist conception of what music is and does in such a way that papers over the deep ontological and epistemological incommensurabilities that structure listening and sounding across colonial divides. As Robinson has argued, the (re)cognitive structures of settler listening all too often misapprehend Indigenous sounding as merely musical, aesthetic, or cultural, at the expense of reckoning with the active force of such sounding as “more-than-aesthetic,” for example as its own subjectivity in an intersubjective listening field, as territorially specific law, or as historical documentation.Footnote 38 In this way, we must recognize that the policy bind that suppressed Native expressive complexes and imposed Western aesthetic education was not just a kind of cultural chauvinism that preferred Western music to Native music; rather, it sought to break down Native expressive practices that were intimately imbricated with territoriality and sovereignty.

Discussing the development of boarding school policy after its strictest version in the early “erase and replace” model, Lomawaima and McCarty identify what they call an expanding “safety zone” in which expressions of Native identity—especially arts, handicrafts, and performance—were gradually deemed “safe” enough to be included in boarding school curricula. An attention to the hidden epistemic violence of assimilation helps us understand that for a cultural practice to be deemed “safe” by school officials meant judging that practice as effectively dematerialized—that is, isolated within a reified domain of culture that, in the policymakers’ minds, had nothing to do with the politics of sovereignty. At the same time, however, it was of course not the government officials that decided how a Native cultural practice related to group life. The policy directive that allowed gradual inclusion of certain expressions of Native identity would also serve as a source of creative subterfuge on the part of the students.

In 1901, the federal Office of the Superintendent of Indian Schools published a comprehensive Course of Study, outlining the standard curriculum for boarding schools and detailing the moral and practical values of teaching each subject. Although this document was published two decades after the opening of Carlisle, most of its materials were clearly modeled closely on Pratt's approach to pedagogy, as was most boarding school education policy until the 1910s. The 1901 Course of Study cited Carlisle's curricular materials directly and was illustrated with well-known photographs of the various workshops, classrooms, and extracurricular activities at Carlisle. One of the shortest sections in the text, especially in comparison to those on various forms of agricultural and domestic labor, is the chapter on music. Reel writes that “music is an uplifting element in life and its power is felt. […] Music as a moral factor makes the pupil feel the charms of harmony and beauty, thus softening and enriching his nature.” Whereas labor cultivated the body and schoolroom instruction cultivated the mind, schoolmasters were urged not to neglect the cultivation of the “hearts” and “souls” of the children, for such spiritual uplift would “help the children to erect for themselves high ideals, and this will aid them to choose the good in life.”Footnote 39

The text goes on to discuss instruction in vocal and bodily technique. Because “tones are the expressions of our moods,” the brochure insisted, singing must be taught in a “pure tone,” with the mouth and the throat open and unobstructed to allow for the “correct enunciation” and “free use of the voice.” Nasal vowels—common in the phonology of many Native languages—were “never permitted.” The Course of Study also stressed that the children must know the meaning of the words they were singing, so as to double the meliorative spiritual effects of the music as sonic entrainment and as meaningful moral lessons.Footnote 40 Following this ideal of total comprehension of the music, the Office urged that “patriotic songs must be taught and the children told something of the life of the author and the reasons for writing the songs given. This leads up to the celebration of national holidays, when patriotic songs should have a prominent place on the program.”Footnote 41 As will be discussed more below, patriotic and holiday rituals played a major role in the ideological discipline of the school, and music was a convenient vehicle to accustom children to the values of patriotism, preparing them for participation in holiday pageants and for their allotted place in U.S. American life.

This emphasis on patriotic songs provided the counterpoint to the other major theme of the children's songs, namely good behavior and an appreciation of schooling. As the following example from a calisthenic musical text shows, students often sang songs that affirmed their gladness to be at school, combining these messages with the physical entrainment not just of their voices, but of their entire bodies. The illustration that accompanies “Away to School” (see Figure 4) shows a group of children coordinated in singing and with their hands upon their head, which the song's lyrics describe as a quality indicative of active and eager learners.Footnote 42 In this way, music education, especially for the youngest students, could combine several of the most important factors of Carlisle's soft coercion: It modeled physical disciplinary coordination and saturated the students with patriotic and moral ideals, which in turn would guarantee that they would “succeed” in assimilating and not go “back to the blanket.”

Figure 4. From Flora T. Parsons, Calisthenic Songs Illustrated, 1.

Beyond the classrooms themselves, music was ubiquitous for marking the strictly regimented daily schedule. Bugle calls marked clock time in military fashion. In My People the Sioux, Luther Standing Bear describes waking up early in the morning to blow the wake-up call for the other students, then having an hour to practice cornet before laboring in the tin shop for most of the morning. In the afternoon, he would go to class, rehearse with the brass band until dinnertime, and finally blow the evening calls at nine o'clock.Footnote 43 Time was also ordered through bells, especially to mark the beginning of mealtimes. Students would sing from the “Grace Before Meals” book, printed onsite, with short choral tunes “written especially” for Carlisle by William Gustavos Fischer with words commonly taken from well-known American poets like Edna Dean Proctor (see Figure 5).Footnote 44

Figure 5. “Grace Before Meals,” cover page and 1, PI-09, Box 15, Carlisle Indian School Collection, Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA.

Although vocal instruction and group singing was the extent of most younger children's exposure to music at Carlisle, more advanced students had the opportunity to pursue music in greater depth, forming various chamber ensembles and choirs. Students could receive piano instruction, join brass or wind ensembles, and even start their own choirs. Military bands played a prominent role in reinforcing the larger disciplinary environment of the school.Footnote 45 These activities made space for select students to develop their musical skills and interests to a considerable degree, leading eventually to relatively successful careers for a few students. Among the most prominent of these was the Oneida cornetist and composer-conductor Dennison Wheelock, who enrolled in Carlisle in 1885 and went on to direct the Carlisle Indian Band, and later, the U.S. Indian Band. Luther Standing Bear also played cornet in the Carlisle band, as did the Lakota musician Robert Coon, who would go on to play in John Philip Sousa's prestigious band.Footnote 46

Music, labor, and land

School officials, however, were careful to distinguish music as extraneous to the real essence of the kind of U.S. American lifestyle to which the students might aspire, which was resolutely centered around agricultural, industrial, and domestic labor. A poem titled “Girls, Take Notice” in an 1886 school newspaper makes this point more explicit:

This poem insists on the superfluity of creativity and social life while also inculcating a sense of noble domesticity for the female students. The feminized domestic labor of social reproduction is presented as Native women's aspirational lot in life; music, literature, art, and even friendship were to be enjoyed sparingly, if at all, and only after the housework is complete. This strict hierarchization of the place of music in life was strongly determined by class-inflected ideologies of enjoyment and pleasure. As the aforementioned 1901 Course of Study put it, “It is not the desire of the Department to give advanced instruction in music, but it is intended to be taught more as a recreation, whose uplifting influence will be felt in the home.”Footnote 48 These statements reveal the way that education at Carlisle was put to particular ideological goals, including the construction of a certain kind of lower-class identity awaiting the students upon assimilation.

However the narratives of industrial education were themselves largely overdrawn. Despite official school rhetoric on the importance of useful job training, the type of vocational training the students at boarding schools received was largely rural in orientation at a time when the white workforce was shifting to industrial manufacturing labor in and around urban settings. As Lomawaima has argued, the “industry” touted by these “Industrial Schools” meant not training for manufacturing work but rather “instruction in the rudiments of civilized living, especially the hard labor necessary to serve the most civilized elite.”Footnote 49 Furthermore, as political theorist Glen Coulthard (Yellowknives Dene) has argued, the explanatory framework of “proletarianization” (forced subsumption into the labor economy) must be considered alongside the prior but related process of dispossession that, with proletarianization, is constitutive of capitalist originary accumulation.Footnote 50 In other words, it is not enough to say that the schools were designed to transform Native peoples into workers; it is also important to understand how these institutions fit into the broader processes of land theft and privatization. Thus, the political-economic raison d’être of the schools lies not primarily in training a new industrial workforce but rather in structurally dismantling Native communities through child removal and subsequently facilitating the capture of Indigenous lands through legislative processes like allotment.

Close attention to the politics of music at Carlisle can help bring this crucial point into relief. Despite the ubiquity of music in daily life at Carlisle, unauthorized musicking (much like the speaking of Native languages) was still officially forbidden, subject to regular surveillance, and suppressed at all costs. This also highlights the important broader context, discussed above, in which Native dance forms were explicitly outlawed on reservations. Expressive practices like the Omaha Dance and the Sun Dance were considered a threat by the federal government in that they represented Native refusals to be engulfed by U.S. American society.Footnote 51 In fact, the state's fixation on breaking up Native peoples meant that any gathering that government officials felt threatened by could be described as a “dance,” which came to symbolize a general anathema to civilization. In the words of an 1887 annual report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Native dance gatherings represented a “cohesion, which is bred of idleness, of a common history, a common purpose, and a common interest” which “must be broken up before the dancing will cease.”Footnote 52 Official statements like these are revealing in that they make clear that the assault on dancing and other “cultural” practices were explicitly tied to federal anxieties about the very cohesion of Native peoples as groups, and therefore to their resistance to ongoing dispossession. Represented in official government texts as cesspools of orgiastic barbarism, dances and related forms of sociality were outlawed as part of the broader preparation of Native peoples for individualization through the allotment process.

In this sense, the prohibition of dance and its replacement via the music education programs in the boarding school system are deeply tied to struggles over the land. As Mark Rifkin has argued, dance was seen by federal agents not just as an unbecoming cultural holdover to be discouraged, but rather as the material instantiation of the kinds of Native collectivity that posed “a structural impediment to the implementation of the privatizing imaginary” and its attendant ideal of the private property-owning nuclear family.Footnote 53 Extending this logic, we can conceptualize the music and arts education program at Carlisle as designed to foster a kind of music making apposite to the newly assimilated Native people in their path toward a life of agricultural and domestic wage labor and second-class possessive individualism. As historian John Troutman has argued, the federal government's “civilization agenda […] depended upon the close monitoring of every musical utterance both on the reservations and in the boarding schools.”Footnote 54 The outlawing of traditional practices in both contexts can therefore be seen as part of the broader material assault on Native peoples and their land. As Mohawk theorist Audra Simpson has shown, the colonial project of knowing, regulating, and suppressing Indigenous “cultures,” including dances and expressive life, was itself a way of distracting from—and even normalizing—ongoing dispossession as the material “scene of object formation.”Footnote 55

Official anxiety around apprehending Native expression thus showed that policymakers understood, in their own way, the deep relationship between music, dance, religion, and communal territorial coherence. Perhaps, then, what Robinson has described as the colonial misrecognition of Indigenous musicking as “just song” can be understood not only as the effect of a “tin ear” that refuses to hear, but also as part of the broader colonial weaponization of aesthetic culture that attempts actively to reduce that musicking to the merely aesthetic.Footnote 56 Such a policy mindset aims, in other words, not just to suppress but to reify Native music as so many dematerialized, commodifiable aesthetic products divorced from the politics of land and sovereignty. It obscures the “more than aesthetic” ontology of Indigenous song, which, Robinson describes, goes beyond mere cultural production or aesthetic contemplation and can operate in various contexts as law, as history, and as what Glen Coulthard and Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar and musician Leanne Betasamosake Simpson call “grounded normativity.”Footnote 57 As Hopi musicologist and legal scholar Trevor Reed has relatedly argued, Indigenous sonic cultures ought to be considered as “the actual material of governance and a source of Indigenous authority,” manifesting a “sonic sovereignty” that confounds the normative separation of law and culture in settler society.Footnote 58 By placing Indigenous music and the arts into the dematerialized sphere of “cultural” difference, settler discourse severs those practices from their inherent relationship to law, politics, ecologies, and sciences, as Bissett Perea has argued. Considering these Indigenous ontologies of song in light of what she describes as their “integral” relationship to “Indigenous self-determination and resurgent movements” is essential for comprehending the larger ontological and epistemological clash of (de)colonization.Footnote 59 These insights can help guide a way of reading assimilationist federal practices against the grain in order to show that, far from being simply ignorant of the place-making power of Indigenous music and dance, settler policy explicitly sought to suppress that expressivity because of its power to produce, activate, and affirm place-based Indigenous solidarity and life. Moreover it is at this level that we can identify another deep parallel between music education at boarding schools and the allotment process, the latter being designed not just to dole out property in acreage but to negate Native relationships to land, transforming land from what Leanne Simpson calls “context and process” into a thing to be owned by an individual.Footnote 60 Likewise, boarding school education attempted to transform the students’ experience of music from one of functional efficacy within collective modes of life to one of meager, individualist recreation within a depoliticized domain of culture.Footnote 61

Opera at the limits of assimilation: The Captain of Plymouth

In this section, I explore the implications of these incommensurabilities by focusing on a celebrated 1909 performance by Carlisle students of The Captain of Plymouth, a little-known comic opera. This reading aims to demonstrate a musicological approach to the cultural texts of settler colonialism that takes seriously the politics of land and place at the heart of both the ongoing processes of dispossession and Indigenous resurgence, expressive practices, and land-based struggle. Like so much opera with colonial themes or performed in colonial contexts, The Captain of Plymouth played what Robinson and Pamela Karantonis have identified as a “nation-building” role in the ideological production at Carlisle.Footnote 62 However, the contradictory significations of the operatic text itself and the discrepant engagements of the students reveal how such nation building is never as univocal as it represents itself to be. Dramatic performance may have served official purposes of indoctrinating students into “civilized” aesthetic culture but, as I explore below, they produced a much more complex array of significations and engagements than Carlisle officials could understand, let alone control.Footnote 63 Opera in federal boarding schools, as Martha Feldman has argued of opera in a different context, “manifest[ed] the very crisis it denied.”Footnote 64

Beyond the daily musical activities, Carlisle's prominent culture of spectacle was central to its assimilationist program. School officials deployed strategies of cultural performance that played on Native-white antagonisms by narratively resolving them on the stage. Some of Carlisle's bands had opportunities to perform for the wider public, and these performances had the dual affordance of enjoyment for the musicians and beneficial publicity for the school itself. Like the rest of the school's propaganda campaign, such public-relations benefits meant the reinforcement of racializing ideologies of cultural development, for instance when the Carlisle Band performed at the Columbian quadricentennial parades in Chicago and New York, under a banner reading “Into Civilization and Citizenship.”Footnote 65 Bands also played at inaugural parades for multiple presidents and the opening ceremony for the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883. These performances can be approached as dually symbolic according to the racial and national ideologies of the day. The spectacle of a group of young Native people in military dress performing Western military and patriotic music communicated the dawning arrival of Native people “into” U.S. American society, as the parade banners made explicit. At the same time, these performances created a sense of the teleological unification of the uncivilized prehistory of the continent with the arrival of a permanent state of civilization under the sign of the nation. This symbolic unification, which made the telos of the nation appear inevitable while simulating Native consent to be civilized, traveled by way of the ritual character of public musical performances. The conscription of Native musicians in these performances could thus be deployed as suggesting a kind of spectacular utopia of U.S. American liberal democracy, in which Native peoples are included as one group among other “others” in the multicultural melting pot.Footnote 66 The dissonance between myth and reality—that a national polity supposedly based on the consent of the people is in fact rooted in historical and ongoing nonconsensual destruction of existing polities—thus strives to resolve itself symbolically by way of the “inclusion” of Native performers in pageantry that celebrates teleological national destiny, representing unbecoming racial and political antagonism as a thing of the past. In addition to serving this broad nation-edifying ideological purpose, this inclusionary signifying maneuver also flattens the broad range of approaches and self-understandings that Native musicians themselves would have brought to such performances, including everything from using the opportunity to make a little money and publicly display their musical excellence to a sincere commitment to the values of democracy and dignity that national culture at least nominally espoused.

The simulation of consent through spectacle was made even more explicit by the nationalistic theatrical programming at Carlisle and elsewhere. Students were regularly made to perform plays, pageants, and operas that reenacted propagandistic narratives of U.S. American history, including narratives of the arrival of Columbus in the New World, the adventures of George Washington, and the first Continental Congress. Like the Columbian centennial parades and other national events, these productions can also be seen as performing a kind of symbolic and narrative engulfment of Native peoples into the telos of U.S. American nationhood, in that the student performers would be made literally to voice and to embody the inevitable history of the nation. Indeed, the profound usefulness of these performances for the school—both in terms of revenue from ticket sales and ideological edification—shows the symbolic power of this spectacle. However, although these performances might be seen as part of the simple hegemonic production of nationalist mythology, a closer look reveals the ambiguity and even the ambivalence of their signifying processes.Footnote 67

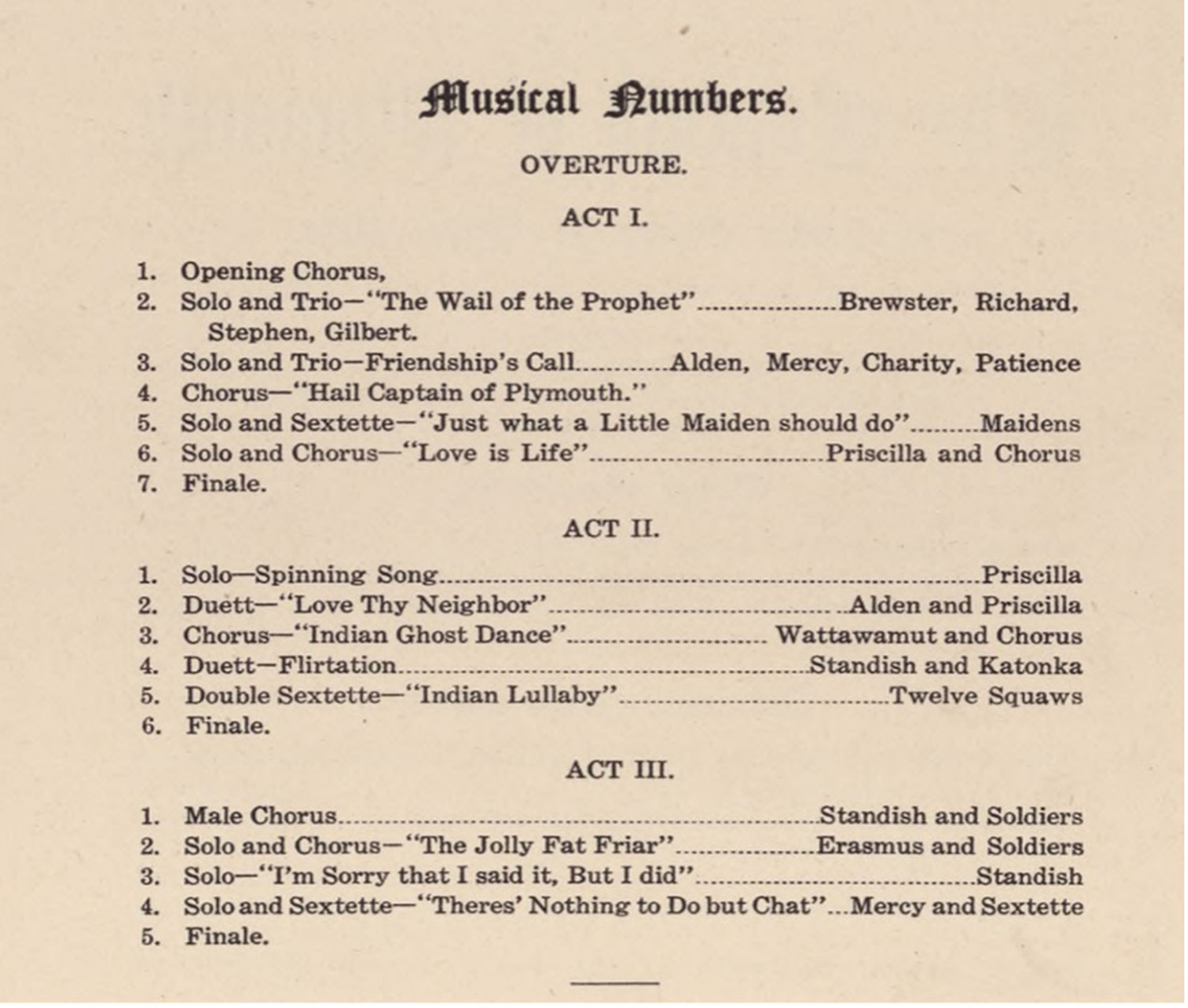

In 1909, the students performed The Captain of Plymouth, “a comic opera in three acts” composed by Harry Eldridge with a libretto by Seymour Tibbals. Based on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's popular 1858 narrative poem The Courtship of Miles Standish, the opera centers on the early English settlers at Plymouth and their conflicts with the Pequots. With a principal cast of twenty plus accompaniment by several choruses and the school orchestra, the three-night run was a major event in the 1909 academic year. One performance was attended by a theater critic for the Philadelphia North American, and accounts were picked up in newspapers across the country. School officials described the performance as “the best ever given at Carlisle.”Footnote 68 In his annual report to the Bureau of Indian Commissioners in 1909, Superintendent Moses Friedman described it as “a remarkable evidence of the artistic temperament and love of music which is possessed by the American Indian,” praising the performance as “beautifully rendered” with “good singing [and] fine orchestral accompaniment”Footnote 69 (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 6. Full cast of The Captain of Plymouth, 1909. Photographer: Everett Strong. CCHS_PA-CH3-117, Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA.

Figure 7. Program for The Captain of Plymouth, “by students of the Carlisle Indian School as Part of the Commencement Exercises, 1909,” PI-1-7-9, Carlisle Indian School Collection, Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA.

The Captain of Plymouth tells the story of Miles Standish (played by Montreville Yuda [Oneida]), leader of a colonial army and captain of the Mayflower, attempting to seduce Plymouth colonist Priscilla Mullins (Carlysle Greenbrier [Menominee]). Miles, though fearless in the face of “the wild beast and savage,” is afraid of (white) women, and so must send his secretary John Alden (Albert Scott [Hoopa]) to win Priscilla's heart on Miles's own behalf. The story of Captain, as well as the Longfellow poem it parodies, is structured by what becomes a love triangle between Miles, Priscilla, and John. In the second act, Miles and his man-at-arms Erasmus are found tied to a tree in a winter forest, having been captured by “Pequot Chief Wattawamut,” played by Harry Wheeler (Nez Perce), and a chorus of “twelve Indian men.” Wattawamut is an apparent reference to the real historical Wituwamat, not in fact a Pequot chief but a Massachusett pniese or “counselor-warrior” who, along with another pniese named Pecksuot, was killed by Standish around 1622 in a “preemptive” attack in defense of the English colony of Wessagussett, nearby Plymouth.Footnote 70 In the opera, after a few minutes of comedic banter between the two captives, they are approached by Wattawamut's daughter, the princess Katonka, described as “a tall, slim girl dressed in gaudy colors.”Footnote 71 Katonka (played by Emma EsanetuckFootnote 72) agrees to release the men on the condition that Miles marries her and takes her to live among the settlers. After being cut loose, both men attempt to run away, but Katonka recaptures Miles and forces him to agree to marry her, after which they sing an idyllic lullaby duet, accompanied by a chorus of Native women.Footnote 73

Act III culminates with the wedding of Miles and Priscilla, which proceeds despite Priscilla's nonconsent because Brewster has promised her to Miles as a reward for him having vanquished the Pequots from the land. Just as Miles and Priscilla are about to wed, however, Katonka announces her objections from the crowd, explaining that “the little Captain belongs to me. He promised to marry me if I would help him to escape from the Indians.”Footnote 74 Katonka thus foils Miles's plan to marry Priscilla, who is then given by Brewster to John (Miles’ secretary), who has fallen in love with her. That Miles is now commanded by the church father to wed the undesirable Katonka is the crowning gag of the opera's comedy of errors.

Although Katonka is undoubtedly written as the target of ridicule, her structuring role as the hinge of the narrative also contains the opera's own undoing. Having become by act III the last of her people (Wattawamut and the other Pequots are last seen in Pilgrim captivity at the end of act II), Katonka reappears as the interruption of the expected narrative arc: Namely, the church-approved marriage of Miles and Priscilla, the heteropatriarchal consummation of white colonial society as a literal reward for the Captain's vanquishing of the Pequots. In Tibbals's racialized contortion of the interrupted-wedding trope, Katonka ruins Miles's plan by holding him to his promise to marry her, wreaking havoc on the symbolic closure of white marriage over settled, emptied land. Although Katonka is represented as the target of racist stereotypes, she also foils Miles's triumphant arrival into social power, and in so doing disturbs the society of Plymouth itself.

The contradictory significance of Katonka raises the question of why this particular opera was selected for performance at Carlisle. In a glowing review in the Philadelphia North American, Carlisle music director Claude Maxwell Stauffer was quoted as follows:

I was moved to attempt this [production] through reading an editorial in The North American on the civilizing influence of opera. I thought if Oscar Hammerstein can spend $1,000,000 to civilize Philadelphians, we could spend a few weeks for the same civilizing influence on the wards of the nation. And say, do you know that I believe we got the better results.Footnote 75

The writer for the North American went on to marvel that such a “wonderful” performance could have been put on “entirely by children of the reservations, many of whom came to Carlisle without surnames.”Footnote 76 However, it is in light of this broader “civilizing” project that the strangeness of the opera itself raises some unsettling questions. As Mohawk scholar Louellyn White—whose great uncle John played to role of Elder Brewster—has pointed out, no “civilization” takes place in the opera at all. Steeped in racist stereotypes and ending in the sense of irreconcilable differences between Katonka and the settlers, the opera, White argues, “may have offered a more realistic view of white-Native relations” than the official discourse of the school itself as an institution of assimilation.Footnote 77 Furthermore, Katonka's return represents, if anything, a ruination of Miles's designs on “civilized” white society. She reappears to disrupt the smoothness of the Plymouth Colony, leading to the comedic disarray of the opera's closing scene. Instead of what might be the expected climax of the white heterosexual couple happily riding off to set up U.S. American society on empty land evacuated of racialized obstacles, Captain ends with the would-be white wedding foiled by Katonka's refusal to disappear. This refusal, moreover, is seen as anything but a welcome assent to assimilation. Rather, Katonka is rendered unassimilable, preventing Miles from enjoying the social power he claims to have earned through anti-Indigenous violence. Katonka's ruination of white heterosexual narrative closure disturbs the social significations of the opera as an explicit aspect of the assimilationist aesthetic education at Carlisle. As a mythologization of the early seventeenth-century Anglo-settler venture in the Plymouth Colony, the compulsory performance of this opera by Native teenagers who did not assent to being assimilated out of existence makes what seems like a flatly nationalistic cultural text into a complex expression of what Dylan Robinson has described as “agonistic” musical performance, refusing the “settled” narrative resolution that it supposedly proclaims.Footnote 78

Conclusion: Mediations of Ghost Dance

One final striking detail raises further questions of the relationship between the surfaces and the depths of the opera's meanings. In act II, Wattawamut and his chorus are directed to perform what the score indicates is a “Ghost Dance.” Given what was already a rather fantastical revision of the real, historical relations between English settlers and Native peoples in the seventeenth century, there is nothing particularly surprising about the historical inaccuracy of the reference to the Ghost Dance, which, contrary to the ahistorical stereotype to which it is reduced here, indexes a specific set of closely related Native spiritual revivalist movements in the late nineteenth century. Standard historical accounts narrate the Ghost Dance of 1890 as a religious movement emerging from the Paiute prophet Wovoka's visions in 1889 and rapidly spreading across the continent, only to be violently suppressed at Wounded Knee on December 29, 1890, when the U.S. Seventh Cavalry massacred around 300 Lakota women, children, and men. As anthropologist James Mooney described it in what has become a standard text on the movement, Wovoka foresaw “that the time will come when the whole Indian race, living and dead, will be reunited upon a regenerated earth, to live a life of aboriginal happiness, forever free from death, disease, and misery.”Footnote 79 However, as Nick Estes (Lower Brule Sioux) has argued, Mooney “pander[ed] to the sympathies of a US public in an attempt to make the Ghost Dance more palatable.”Footnote 80 In the settler imaginary, the Ghost Dance has represented a final “outbreak” of Native resistance that was finally defeated at Wounded Knee.Footnote 81 Estes and other Indigenous studies scholars have more recently questioned this “ontological reduction” and insisted on radically reframing the Ghost Dance movement not as an isolated “cult” that disappeared at Wounded Knee but rather as a symbol of broad Indigenous anticolonial conceptions of time and space, as a “critical metaphor” for Native literary production, and as “Indigenous revolutionary theory.”Footnote 82 If the Ghost Dance (and its supposed demise at Wounded Knee) has been a symbol of the finality and futility of Native resistance in settler eyes, but has alternatively remained an expansive vehicle—both metaphorical and literal—for ongoing anticolonial theory and practice, what happens when young Native people perform what a colonial operatic script calls a “Ghost Dance” within the walls of the institution that is perhaps most representative of the violence of colonialism?

Insofar as it articulated resistance to the forces of assimilationism and axiomatic settler expansion, the Ghost Dance represented the opposite of everything that Carlisle stood for—from state education policy to a liberal-progressive philosophy of history that assumed the inevitable demise of Native peoples—and was an illegal religious practice under the 1883 “Code of Indian Offenses.” Here too, however, Carlisle's “safety zone” policy was riddled with contradictions: In 1907, students performed Stauffer's arrangement of a “Song of the Ghost Dance,” with “words in English.”Footnote 83 As Troutman has argued, school officials believed that such a “dangerous” cultural form would be admissible at Carlisle as long as it were “safely contained in the students’ repertoire.”Footnote 84 In school newspapers from the months following the Wounded Knee massacre—to which Pratt only referred as a “battle”—the Ghost Dance was understood sometimes as an existential threat to progress and sometimes as merely “trouble” and “foolishness.” In either case it was always blamed solely on “ignorance on the part of the Indians.”Footnote 85 A polemic in the school newspaper argued that the tragedy at Wounded Knee would have been prevented “had there been [a] hundred times as many Sioux boys and girls educated away from their tribes as there have been in the past ten years.”Footnote 86 In fact, a number of returned students who left the school in the first decade of its existence, including Plenty Horses, Grant Left Hand, and Plenty Living Bear, found in the Ghost Dance a renewed sense of the community ties that Carlisle had attempted to extinguish.Footnote 87 Like other practices deemed “conservative” from the perspective of liberal settler teleology, the Ghost Dance provided disaffected Carlisle survivors an energetic new structure of feeling through which they could articulate themselves within their communities.

Perhaps, then, the opera unwittingly calls up something of the unassimilable force of the Ghost Dance as a symbol of the general Native refusal to disappear (by conquest or by assimilation), a conjuring that the opera itself tries unsuccessfully to neutralize by providing semiotic and narrative closure. Nevertheless, although the archives I have consulted do not record how Harry Wheeler and the young men in the “Indian chorus” felt in performing The Captain of Plymouth's version of a “Ghost Dance” (or even how they chose to stage it), the ontological clash at issue here suggests that a wider range of meanings were available to them than those which music director Stauffer could have intended. As the Osage scholar Robert Warrior has argued of boarding school history, “music and art created space within the schools for a sanctioned alternative to the totalized space that Pratt and other educators initially designed.”Footnote 88 In this case, even when the music that students were assigned to perform carried a clear (if rather overstated) “civilizing” function, the students might be seen as setting a strategic and creative intelligence to work in their realization of the music, exceeding the official school policy of assimilationist subject formation.

In its striving for meaningful, self-conscious unity and the ultimate return of all the land to Native peoples, the Ghost Dance also provided a formal resource for the emergence of “intertribal sociality” that many historians have attributed to the boarding school era itself.Footnote 89 In this way, the self-conscious sense of an Indigenous collectivity beyond particular tribal, linguistic, and geographical associations can be understood as the ironic outcome of the kind of deindividuation that the schools violently enforced under the rubric of U.S. American capitalist individuality. The Captain of Plymouth was performed by a cast of over eighty young people from over a dozen different Native communities all across the continent, within an institution where thousands of students from hundreds of different communities would gather and bring their personalities, identities, and densities with them to a shared experience of navigating settler-colonial structures.Footnote 90 Perhaps, for this reason, the 1909 performances of Captain can be seen as a kind of flashpoint in what music scholars Tara Browner (Choctaw) and John-Carlos Perea (Mescalero Apache) have discussed as the Native American musical intertribalism that forms so vital a part of contemporary Native musicking practices.Footnote 91

Native peoples who negotiated government boarding schools continuously made and remade their own terms of engagement beyond the narrow expectations of policymakers and school officials. As settler-colonial policy and ideology braced under the weight of its own contradictions, students used much of what was available to them at school and rejected what they didn't need. Even if The Captain of Plymouth's deployment of a “Ghost Dance” trope was meant simply to signify barbarism, it also symbolizes the very resurgent intertribal sociality and radical visions of Native land-based sovereignty that ended up emerging from the boarding school era. Perhaps the clearest evidence for the failure of the boarding school mission is that it was exactly visions of this kind that would go on to guide continental and global Indigenous decolonial movements in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Despite its imposition as part of the broad “civilizing” project of the school, this collective performance of an illegal dance bore an irreducibly “more-than-aesthetic” nature that may have provided one of the sparks for this new political formation. At the very least, though, it was a moment in the young lives of the students who performed it, lives that would continue to develop based not on the predetermined telos of national time but based on their own agencies, desires, and senses of self and community. This calls to mind Harry Wheeler, who as Wattawamut led the group of young men dressed up as (imagined) “Pequots” in their interpretation of the Ghost Dance. Decades later, Wheeler collaborated with linguist Haruo Aoki in the construction of a Nez Perce dictionary. Nez Perce scholar Beth Piatote has described studying with Aoki in her own process of linguistic and literary resurgence, working with materials produced both in bilingual mission schools and from Wheeler's collaboration in the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 92 Wheeler had applied to enroll at Carlisle on his own behalf in 1908 and left after 3 years, presumably having gotten what he wanted from the school. He returned to his home, where he would go on to become a cherished historian and spend his life helping to sustain the communal memory of his people.

Wheeler's post-Carlisle trajectory also calls to mind Emma Esanetuck, who had petitioned to leave the school in the spring of 1909 and finally departed for her home in Port Clarence in June, just a few weeks after the performances of Captain. Despite what was hailed as her successful performance as Katonka, school officials marked her behavior as declining from “good” to “medium” in her final months at school.Footnote 93 I imagine her declining marks as just the archival impression of an unfolding refusal of the sort of “civilizing” mission that required her to stay away from her family and her community. Ultimately, Esanetuck, Wheeler, and the rest of the young people who navigated Carlisle demonstrated time and time again that it was not ultimately for the state officials to decide what these institutions would be used for. The supposedly “civilizing” effect of an opera performed at a school bent on elimination by assimilation was as much a settler fantasy as the notion that these colonial institutions—Carlisle, the system it launched, and the settler state itself—were justified, benevolent, and permanent.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to those who helped bring this article into being, first and foremost the two anonymous peer reviewers who provided extraordinarily helpful and generous feedback on the manuscript. I am also grateful for the feedback of Dylan Robinson, David Samuels, Fanny Gribenski, Mara Mills, and Brigid Cohen, who helped me shape this material when it took the form of a dissertation chapter. Others provided helpful feedback, insight, and encouragement along the way, especially Lou Cornum, Brian Fairley, and Nancy Yunhwa Rao. I would also like to thank my collaborators on the Boarding School History Project at the Center for Black, Brown, and Queer Studies: Rachael Nez, Elizabeth Rule, Eli Nelson, Sarah Clinton-McCausland, Ahmed Ragab, and Myrna Perez Sheldon. This group's discussions of the role of Carlisle in Native and U.S. histories and presents have immensely shaped my thinking. Archival research for this article was funded in part by the Department of Music at NYU's Graduate School for Arts and Sciences and by a Research Fellowship from the Consortium for the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine. I would lastly like to thank Emily Abrams Ansari, Jacqueline Avila, and Anna Lopez for their guidance through the editing process.

Competing interests

None.

Derek Baron (Ph.D., NYU 2023) is a postdoctoral associate at the Center for Cultural Analysis at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, and a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Black, Brown, and Queer Studies (BBQ+), where they work on the collaborative Boarding School History Project. Their monograph in progress, The Geopolitics of Voice, explores the role of music, language, and sound in early American settler-colonial policy and discourse. They are currently guest editing a special issue of American Music on the theme of “Music, Sound, and Law in the Americas.”