The earliest extant footage of African American jazz and classical violinist Emma “Ginger” Smock is an episode of the popular Los Angeles variety television show Dixie Showboat, broadcast on local station KTLA. Approximately 7 minutes into the episode, just after a blackface minstrel routine by duo Peanuts and Popcorn, the camera pans to Smock sitting stage right among the showboat's “passengers.” An open violin case waits expectantly at her side. The ship's “captain,” host Dick Lane, approaches, saying, “Ma'am, I don't want to appear to interrupt your reverie here, but you seem totally fascinated by this orchestra and the music [i.e., the house band, Nappy Lamure and his Straw Hat Strutters]. Is that right?” “Oh, I am. I definitely am,” she says in a lilting Californian accent. He asks, “Are you a musician?” She shakes her head and replies, this time in a high, strained voice with a faux-Southern twinge, “Well, I'm trying to be.”Footnote 1

By late 1951, when this episode of Dixie Showboat likely aired, Ginger Smock was an established Los Angeles freelancer. She had fronted bands including The Sepia Tones, The Three (later Four) V's, and Ginger and Her Magic Notes; held down long-running engagements at venues such as The Last Word and The Waikiki Inn; hosted the radio show Melody Parade; played on a number of recordings; and, earlier that year, made her television debut with the short-lived CBS production The Chicks and the Fiddle.Footnote 2 Her claim on Dixie Showboat that she is “trying to be” a musician is thus as facetious as the altered voice with which she makes that claim; her role on the show was presumably to play the ingenue, just as Dick Lane played her discoverer.

“Trying to be,” repeats Lane. “Well, I see you've got an instrument here.” “What kind of an instrument is that, ma'am?” Smock responds in a teacherly, almost patronizing, tone: “A violin.” Lane asks if she would “mind playing us a little something on that violin” and Smock's faux-Southern accent returns. On a high, incredulous pitch, she replies, “Well, I wouldn't mind, but in front of all these people and with a great big band like that?” Again, her altered vocal quality underscores the disconnect between her scripted lines and her musical history to date.

Ginger Smock was known for her arresting stage presence. In the late 1940s, she had been hailed as “a happy combination of personality, glamour and talent” and a “heart throb violinist-entertainer.”Footnote 3 Later reviews of her performances on Dixie Showboat, once she joined the cast as a regular, also give the lie to her staged amateurism on this episode. Indeed, in April 1952, Jet would celebrate her “zany antics” on the show, calling her “bombastic” and “a fireball… She stomps her feet, sways her head and gyrates her arms in lively rhythm as she bows vigorously on her fiddle.”Footnote 4

“Why certainly,” Lane replies to Smock's disingenuous hesitancy. “Here's your chance, ma'am. What would you like to play?” She says, “Well, I'd be thrilled if they'd play ‘What Is This Thing Called Love.’” Lane turns to the house band and asks, “Boys, you know ‘What Is This Thing Called Love’? Miss Ginger Smock. Would you play it for her?”

Once Ginger Smock has accepted Lane's invitation to perform, her demeanor shifts. No longer playing the wannabe musician, she cracks a huge smile and strides confidently to center stage. The band starts up and Smock plays the melody once with classical tone and technique, adding in occasional double stops and virtuosic runs. She stands tall and poised, her eyes often closed, her face concentrated. Toward the end of the form, she smiles slightly, the band switches to a swing rhythm, and Smock breaks into a high-energy solo over three choruses. She relaxes her posture, her hips shifting from side to side. When she plays an extended run of ascending tremolo scales, some audience members clap spontaneously, and she smiles in response. On the final sixteen bars, she shifts higher, swings harder, strums a few pizzicato chords precisely in time with the house band and stops short, flinging her arm out as the horns play a long note. The audience claps and cheers, some yelling “Yay!” Smock takes a slight bow. Beaming, with a nod to the captain and a bounce in her step, she walks back to her seat—and disappears from our view for 30 years. The next video footage of her would be a late-career demo tape accompanying lounge singer Billy Andre in Las Vegas in the 1980s.Footnote 5

Ginger Smock can claim a number of firsts: She was the first woman to record hot jazz improvisations on the violin; she was one of the first African American women bandleaders on television; and she may have been the first African American full member of a Las Vegas showroom orchestra.Footnote 6 My goal in this article is not to argue for Smock's exceptionalism, however. Rather, I draw on a wide range of archival sources to examine the ways in which Smock negotiated the work-a-day world of professional music-making as a racialized woman. This is a world in which she was often called upon to play the dual roles that she inhabits on the set of Dixie Showboat: The timid amateur “trying to be” a musician and the stunning virtuoso with a “gingervating” stage presence.Footnote 7 It was a world in which she was a civic-minded “star” in the local African American press but a struggling musician in need of discovery, her gender foregrounded and her race effaced, in jazz magazine DownBeat. It was also a world in which she was denied recording opportunities due to her race and gender, but hired to play a variety of Others, from Hawaiian native to “bronze Gypsy,” roles that Smock seems to have taken on with pragmatism and, occasionally, delight.

This article documents Smock's 50-year career, from her early years on Los Angeles’ Central Avenue through her work on radio and television, a stint at national touring, and her last decades in Las Vegas. I weave together Smock's outward-facing successes, in the form of gigs, studio sessions, and audience reception, with her later disheartened reflections on her career, as voiced in interviews and correspondence: “What a waste!” she would write to friends in 1983, “I should've been a secretary or something.”Footnote 8 Through a close reading of a 1951 DownBeat profile of Smock, I argue that mid-century jazz reporting positioned women instrumentalists, whatever their previous accomplishments, as waiting for a career break that never comes—a narrative which I term perpetual discovery. Such narratives foreground the discoverer and the recuperative process rather than the subject herself. I also show that, despite DownBeat's ostensibly color-blind presentation of jazz at the time, the magazine foregrounded the physicality and sexuality of white women instrumentalists while absenting race and even corporality for Black women instrumentalists. Throughout, I hold in consideration a question posed by Jayna Brown with respect to Valaida Snow: “How can histories—particularly lost histories—of black women be constructed in ways that remain sensitive to the slippery properties of fact (and its often unsupportive banality) and wary of the temptations of recuperative triumphalism?”Footnote 9 As an antidote to the effacement implicit in a narrative of perpetual discovery—itself a form of recuperative triumphalism—I propose close documentation of sustained artistic practice: The day-to-day facts of a working musician's life, in all their slipperiness and banality.

This article reads Smock's career through an intersectional lens in order to, in the words of Patricia Hill Collins and Sirma Bilge, “illuminate the organization of institutional power” in the musical worlds she inhabited and the ways in which “power relations of race, class, and gender… buil[t] on each other” to shape her performing and recording opportunities and her reception in the mainstream press.Footnote 10 By demarcating the breach between Smock's 50-year professional career and the narratives of discovery that positioned her as always on the verge of unachieved success, I interrogate what Maria V. Johnson has termed the “entrenched notions of authenticity” in both scholarship and journalism that determine not only which artists are “recognized, recorded, and studied” but also, crucially, how Black women musicians (electric blues guitarists, in Johnson's example) are received and portrayed and which recording opportunities are made available to them.Footnote 11 Women jazz instrumentalists in the mid-twentieth century were, almost by definition, inauthentic, as Sherrie Tucker has noted, with instruments other than the piano “considered ‘normal’ in the hands of men, and a ‘gimmick’ in the hands of women,” but Black women instrumentalists had even fewer recording opportunities than their white peers.Footnote 12 An intersectional reading of Smock's career illuminates the structuring of what Collins and Bilge term the “cultural domain of power” and points to the ways in which narratives of perpetual discovery help “manufacture and disseminate [a] narrative of fair play” through unrealized promises of “equal access to opportunities” via the next big break.Footnote 13

How do we hear, and see, the performances of an African American woman whose professional identity, stage persona, reception, and gigging opportunities were inextricably linked to her gender and to the color of her skin? How do we historicize the contributions of a performer who succeeded—as measured via gigs and reputation—as a working musician for a half-century but who retrospectively saw herself as a failure? Furthermore, reworking a question that Lisa Barg has posed with regard to Billy Strayhorn, what new histories of musical, social, and cultural life in jazz and classical music does Smock's story afford, and what sonic histories of Otherness might be recorded in her musical output?Footnote 14 Through an in-depth survey of Smock's professional life, I offer a critical perspective on the ways in which social identities may shape both musical careers and our historicization of those careers.

Building Out the Archive

Archives are “where law and singularity intersect in privilege,” writes Jacques Derrida.Footnote 15 The reminder by Joan M. Schwartz and Terry Cook that archives are “dynamic technologies of rule” that “create the histories and social realities they ostensibly only describe” carries particular meaning in a story such as Smock's, whose absence from jazz violin histories is linked to her lack of recordings—the sine qua non of jazz historiography—which is in turn linked to the “social realities” within which she lived and worked.Footnote 16 The contents of public archives delimit the narratives that may be told about the associated body politic, meaning that building out those archives is one means of claiming space to script the future.Footnote 17 Nevertheless building out an archive does not eliminate its limitations. In certain corners of the jazz archive Ginger Smock is an object of perpetual discovery while in others she is simply absent. To dismiss this—even in the name of expanding that archive—is to deny its impact on her career and her own retrospective reading thereof, while to foreground it would generate a new narrative of discovery. This article seeks a middle ground that “inhabits [the] limitations” of the archive while refusing to center exclusion or absence.Footnote 18

From 2013 to 2018, I worked with two families to coordinate the transfer of their private collections of Smock-related materials to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). Items donated by Lydia Samuel Bennett, a member of Smock's extended family, include handwritten manuscripts of Smock's compositions and big-band arrangements; onionskins and prints for several of her compositions; reel-to-reel recordings of a studio session and a 1967 live performance at Raffles Restaurant; items from Smock's own collection of LPs and 78 rpm records; and various personal and professional effects, including her violin and music stand. Items donated by Dean and Ivy Reeves, the son and wife, respectively, of Canadian jazz violin collector John Reeves, include correspondence between Smock and John Reeves from 1973 to 1994; gig announcements and press clippings; personal and publicity photos; several videocassettes; and forty-three cassette tapes and seven reel-to-reels containing recordings of live performances, interviews, phone conversations, a backstage jam session, and practice and listening sessions, as well as dubs of earlier studio and demo recordings. This article draws from these materials as well as African American newspapers, trade journals, magazines, and published and unpublished interviews.

Smock spent much of her later career working toward a solo album that was never realized, though one of her bands did release an LP, On the S.S. Catalina with the Shipmates and Ginger, of what Smock called “original island music.”Footnote 19 Recent interest in her jazz playing is indebted to the posthumous CD Strange Blues: Ginger Smock, The Lovely Lady with the Violin, Los Angeles Studio & Demo Recordings 1946–1958, compiled by English jazz violin historian Anthony Barnett, who was in touch with Smock in the last years of her life.Footnote 20 Barnett published a comprehensive discography of Smock in the print newsletter Fable Bulletin Violin Improvisation Studies in 1994, with subsequent updates.Footnote 21 He also wrote a brief entry on Smock for the New Grove Dictionary of Jazz and profiled her in Strad magazine.Footnote 22

Academic sources on Ginger Smock are few and far between. Kristin McGee mentions her briefly in Some Liked It Hot: Jazz Women in Film and Television, noting her work with The Chicks and the Fiddle on CBS.Footnote 23 Smock also appears in Linda Dahl's Stormy Weather: The Music and Lives of a Century of Jazzwomen, though Dahl states, incorrectly, that Smock's first professional gigs were with Ada Leonard's all-white big band.Footnote 24 Los Angeles music educator and historian Bette Yarborough Cox interviewed Ginger Smock in 1983: A video of that interview is available online and a lightly edited transcription appears in Cox's magisterial Central Avenue—Its Rise and Fall (1890–c. 1955).Footnote 25 Several interviewees for the UCLA Central Avenue Sounds Oral History Project mention Smock, but she herself was not interviewed for that project.Footnote 26 Sherrie Tucker graciously shared with me a transcription of her own 1993 interview with Smock, excerpts of which may be found in Tucker's 1998 article on African American women musicians on Central Avenue.Footnote 27

Given that Smock's later career was defined, in part, by her struggle for recording opportunities, a word is in order with regard to the audio and video tapes now at the NMAAHC. Many of the tapes are significant for research purposes, such as a 1975 radio interview on CRFN in Edmonton, Alberta; a 1976 recording of Smock playing along with a televised broadcast of violinist Clarence Gatemouth Brown on Austin City Limits; and a 1981 recording of Smock commenting on and playing along with LPs of violinists Stuff Smith, Fritz Kreisler, Don Harper, and Svend Asmussen. Two reunion concerts with organist Nina Russell and “friends” in Hungry Horse, Montana, for Russell's birthday, have a promising line-up but, unfortunately, poor audio quality.Footnote 28 Sound quality is better on a 1985 recording of a live concert with guitarist Greg Lowe in Winnipeg, but the musicians’ stage patter indicates that Smock is sight-reading many of the pieces. Some tapes are dubs of Smock's earlier studio and demo recordings, now available on Strange Blues, while others are copies of demos that she made during her Las Vegas years. Sound quality varies widely. In sum, although these recordings are of significant scholarly interest, substantial curatorial work would be necessary before making selections available to the general public.

“First Lady of the Violin”: Building a Career

The geographic story of Smock's family, from rural areas of the southeastern United States to urban centers in the North and West, follows common trajectories of the Great Migration. Smock's mother, Ruby May Garrett, was born in Greenwood, Mississippi circa 1891. Her father, Henry James Smock (born circa 1887) was from Shelbytown, Kentucky, though he seems to have spent at least some time in Marion, Indiana as a boy. By 1919, they were married and living in Chicago, and their daughter was born in that city on June 4, 1920.Footnote 29 Six years later, due to challenging family circumstances, Smock was sent to live with her paternal aunt and uncle, Georgia and Lawrence Jones, in Los Angeles. She grew up on Central Avenue in a close-knit African American community, delimited by race-restrictive housing covenants, where music was at the center of cultural and economic life, and her teenage years coincided with the swing era and an “explosion of jazz” on the Avenue.Footnote 30

Smock was something of a child prodigy. She began private classical violin lessons with Bessie Dones at age eight and, at age ten, performed Kreisler's “Old Refrain” at the Hollywood Bowl to a standing ovation.Footnote 31 The following year, she gave a recital at the People's Independent Church of Christ and with the proceeds purchased the violin that she would play throughout her career.Footnote 32 At age twelve, she was invited to a film audition. As she later told Sherrie Tucker, “Twentieth Century Fox heard of [me]… They wanted a little girl violinist to play in a movie. And so my teacher came by the school and got me.” At this point, however, Smock's story shifts:

I walked in there and the studio moguls looked at me from head to toe, a twelve-year-old, with the braids hanging down, like I was something from Mars… They acted like they weren't glad to see me. I didn't receive any kind of welcome… And one of them said, “What are you?” And I didn't know how to answer that other than say, “I'm an American.” I come from a mixed marriage, which is obvious. And very proud of that. Thankful. And they said, “Well, my dear, I'm afraid we can't use you. You do not represent any particular group of people.” And the tears, I remember, rolled down my cheeks, ran down my chest, and I said, “I'll never come back, even if you begged me. I'll never come back. I will never see you again.” And I walked out… And my teacher was crying, fighting back the tears, because she was humiliated and embarrassed for me. And I guess that did something to where that rejection has stuck to that day. And I'm 73 years old and it's still sitting.Footnote 33

As Collins and Bilge note, intersecting dynamics of power and control based on social categories may shape the specific, individual ways that a person experiences bias and “create pipelines to success or marginalization.”Footnote 34 Although census records list both sides of Smock's family as Black and she grew up in a predominantly African American community, she seems to have self-identified as mixed-race (of African American, Irish American, and Native American heritage) and the above anecdote suggests that Smock understood early on her particular physiognomy as a basis for marginalization.Footnote 35 In her letters to John Reeves, Smock refers to herself as an “I.B.I.,” or “Irish-Black-Indian,” and presumes that others will restrict her opportunities based on her racial identity.Footnote 36 “He probably thought it was ‘corny,’” she writes to Reeves after he has sent her demo to a potential supporter, adding, “Plus, maybe he doesn't favor IBI's, too. smiles!”Footnote 37 When she is invited to participate in the 1984 St. Patrick's Day parade in Las Vegas, she underscores the disconnect between the presumed whiteness of that space and her own racial identity, again softening her statement with a wry “smiles!”: “Did I tell you…I rode and played (by special invitation) on the Daughters of Erin float… Yep! The ol’ I.B.I. herself. smiles!”Footnote 38 The mix of bitterness, defiance, and dry humor that characterizes these and similar remarks in her letters suggests that once Smock had been shunted toward the pipeline to marginalization as a 12-year-old, she carried the experience of that rejection across her career.

Smock's star continued to rise through her teenage years. At age thirteen, she performed “To a Wild Rose” on Clarence Muse's local radio program and, according to Tele-Views, “her rendition so charmed an influential listener that she was given a scholarship at the Music and Art Foundation in Los Angeles.”Footnote 39 At Jefferson High School, she joined the band and was drum majorette under celebrated orchestra and bandleader Sam Browne, who occasionally had her conduct in his stead.Footnote 40 Meanwhile, although she did not study jazz formally, she would often “sit by the phonograph” and improvise along to records by violinists Joe Venuti, Stuff Smith, and Eddie South.Footnote 41 She also attended big band performances by Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Benny Goodman, and Glenn Miller: “I'd sit there and get really inspired… and go home and try and play a few things that I would hear on violin.”Footnote 42

As a teenager, Smock was first violinist with the All-City Symphony Orchestra and the “only person of her race” to play with the Junior Philharmonic Orchestra, under conductor Otto Klemperer.Footnote 43 She attended Los Angeles City College and the Zoellner Conservatory of Music and, after graduating, led the 48-member Symphonetta ensemble, which performed “light concert music” in Southern California.Footnote 44 Indeed, as violinist Kelly Hall-Tompkins has noted, Smock's early life had all the hallmarks of a pre-professional classical music career, and her goal was in fact a position with a symphony orchestra.Footnote 45 In the early 1940s, however, African Americans were excluded from professional orchestras in the United States. Smock took a job at a lithography shop, continued to perform at church and community functions, and joined the Southeast Symphony, a community orchestra for African American musicians.Footnote 46 Her first jazz gig, in 1943, was unexpected: She received a call from the union to sub for Stuff Smith with Austin McCoy's ensemble at Randini's on Western Avenue and, although she still thought of herself as a “concert violinist and a church violinist,” agreed to audition. She went to the club, played along, according to Tele-Views, to a “jazz tempo beat out by the [club] owner,” and got the job.Footnote 47

Smock's high school classmate Jackie Kelso would later recall her approach to gigging as eminently pragmatic: “[Her attitude was,] you want to make a living playing music? You simply find out what product is being sold on the market and make sure that you can do [it].”Footnote 48 Her first band, The Sepia Tones, with Mata Roy on piano and Nina Russell on Hammond organ, performed such favorites as “Rhapsody in Blue,” “Persian Market,” “Holiday for Strings,” and their theme song, “Poinciana.” This was the “less challenging swing and novelty repertoire” that, as Tucker states, “employers and audiences generally expected” from all-women groups at the time.Footnote 49 By May 1944, the trio was “packing them in” at The Last Word on South Central Avenue.Footnote 50 Billboard described them as a “sure-hot” for upscale venues booking “sepian talent” and a solid fit for “[u]pholstered lounges appealing to moderns,” and lauded Smock's contributions: “As a hot fiddler she carries the fast tempos well and her boogie-woogie interpretation is out of this world. She is one of the most versatile violinists to hit these parts.”Footnote 51 Although The Last Word was presumably integrated, given its location, at least some of the trio's performances were likely for all-white audiences. Later in 1944, for instance, they performed at The Rite Spot in Glendale, a sundown town.Footnote 52 The Sepia Tones disbanded in late 1944 or early 1945 when Smock fell ill, “suffering from exhaustion and a near-nervous breakdown.” She put down the violin for a year to recover and then returned to performing in Los Angeles clubs.Footnote 53

Smock's primary gig from 1947 to 1950 was at The Waikiki Inn on South Western Avenue, where she “dressed Hawaiian, with the grass skirts … the flowers in the hair and the lei.”Footnote 54 From August to September 1947, she played electric violin with Walter Johnson on piano, a duo which the Los Angeles Sentinel described ambivalently as “definitely different.”Footnote 55 From March to May 1948, she performed with Emile Williams and Lloyd Glenn on “twin pianos” before returning to a duo lineup with Glenn only. Reviewing the show that June, The Pittsburgh Courier called her a “big hit” with a repertoire that “[ran] the gamut from Bach to Boogie… Talent scouts from Hollywood are casting their eyes her way.”Footnote 56 Williams returned to the ensemble in July, now on Hammond organ, thus replicating the Sepia Tones instrumentation. “[W]hen it comes to sweet music, this trio have really got something,” declared the Los Angeles Sentinel.Footnote 57 The ensemble was a steady draw, in part for its musical constancy:

Contrary to the belief of many that the public tires of the same type of entertainment over and over again… the musical trio at Mike's Waikiki, over on Western [A]venue, still hold forth nightly and continue to draw upon a large following that never seem to get enough of their kind of music… With all due credit to the talents of these three top-notch artists, like credit must be given to their realization of the type of music their patrons enjoy and their efforts towards adhering strictly to this policy.Footnote 58

In Smock's final year at the Waikiki, she replaced Glenn first with pianist Gid Honore and then with guitarist Ceele Burke and pianist Charles (Charlie) Pryme before settling on a trio with Pryme and Williams, both of whom she would continue to perform with over the following decades.Footnote 59

Smock's long stints at the Waikiki—where she ended her tenure as the “‘Sweetheart of the Strings’ and her torrid trio”—framed numerous other engagements in the same years.Footnote 60 In 1946, she brought “Ginger and Her Magic Notes” to the Sphinx Club on Sunset Boulevard, with a rhythm section composed of Jack Carrington on piano, Louis Gonzales on guitar, and Bill Thomas on bass.Footnote 61 As “First Lady of the Violin” in a revue at The Last Word from October to November 1947, she “scored a smash success,” according to The Cleveland Call and Post, and four nightclubs in San Francisco began “bidding against each other for her services.”Footnote 62 In January 1948, she opened at The Memo on a bill that included blues singers Wynonnie Harris and Joe Turner.Footnote 63 The Pittsburgh Courier also has her hosting “her own radio program,” Melody Parade, in these years.Footnote 64

Smock launched her recording career in the mid-1940s. Her first studio session was in July or August 1946 for Joe Alexander with the Red Callender Quintet, under the name Emma Colbert, but the recording that put her on the proverbial map came in September of that year, when she joined the Vivien Garry Quartet for Leonard Feather's Girls in Jazz project on RCA Victor.Footnote 65 Playing a Rickenbacker electric violin, she recorded four 78 rpm sides, including the 12-bar blues “A Woman's Place is in the Groove.”Footnote 66 “Five west coast girls playing good jazz, including some stuff Smithian sounding fiddle [sic],” wrote DownBeat.Footnote 67 Billboard panned the project, however, describing it as of little musical value and useful only as “novel emcee chatter,” though they nevertheless considered it “a demonstration that there are femme jazz talents that can make many a feller pack up.”Footnote 68 Smock's playing on these sides amply demonstrates her hard-edged rhythmic sensibility and blues-based soloing and showcases certain hallmarks of her improvisational approach, such as the use of ostinati to build intensity. The narrow compass and straightforward phrase structure of her solos does, however, point to her relative inexperience at this stage of her career.

An illustrated advertisement in the California Eagle suggests that by 1948, Smock—with her violin—had come to function as a metonym for the successful, elegant, and socially connected African American working woman. The ad shows two women conversing on the phone. One is dressed in bathrobe and slippers, her hair up in a kerchief, and sitting in a torn armchair surrounded by empty liquor bottles. “No Mabel,” she says. “I just can't go. I entertained ‘at home’ last night, and I'm as beat as Lionel Hampton's Drums.” Her conversation partner wears a fitted skirt, billowing blouse, and heels. Her hair is loose and wavy, and she leans casually against a cupboard. “Why honey,” she replies. “I gave a big party last night too. But I entertained at ASSOCIATED CLUBS and I'm as [fit as] Ginger Smock's fiddle.”Footnote 69 This advertisement, which ran on at least eight occasions, points to the high degree of name recognition that Smock enjoyed on Central Avenue while still in her twenties and suggests that she and her music denoted independence and professionalism for women in Los Angeles’ African American community.

In late 1950, although still at the Waikiki, Smock brought her band to the Sphinx Club for an after-hours gig and caught the ear of Klaus Landsberg, an executive at Los Angeles television station KTLA.Footnote 70 He invited her to audition and a few months later the Los Angeles Sentinel reported that “PHIL MOORE is rehearsing an eight-piece all-girl combo for a shot at television, which may feature GINGER SMOCK on violin.”Footnote 71 The show was The Chicks and the Fiddle, which premiered on June 4, 1951—Smock's birthday—with Smock as bandleader, Clora Bryant on trumpet, Willie Lee Terrell on guitar, Jackie Glenn on piano, Anna Glasco on bass, Mattie Watson on drums, and Vivian Dandridge on vocals and as MC.Footnote 72 They were “the first band of sepia swingsters to break into west coast TV,” with “some really bright and jumping musical routines,” according to DownBeat, and one of the first African American bands nationwide to host a regular television show.Footnote 73 In the end, The Chicks and the Fiddle ran for just over a month, due to a lack of commercial sponsorship and in spite of a campaign by the Los Angeles Sentinel to “bombar[d]” the station with “letters and phone calls… [to let] sponsors know just how much we appreciate the talent presented.”Footnote 74 Smock had broken into television, however, and would continue working in the new medium through the remainder of the decade.

“Just Another Problem We Have to Face”: Navigating Bias in the Jazz Press

In July 1951, shortly after her television debut, Ginger Smock was profiled in DownBeat by staff reporter Charles Emge, writing under the pseudonym Hal Holly.Footnote 75 This profile is ostensibly a column for Emge's “Hollywood Beat” series but also functions as a contribution to the magazine's “Girls in Jazz” series, launched by critic and producer Leonard Feather shortly after his production of the album by the same name. I have located eight “Girls in Jazz” articles from 1951 and 1952, six by Feather and two by Emge, including the latter's profile of Smock. In this section, I interrogate racialized constructions of gender in the “Girls in Jazz” series and argue that both Feather and Emge shaped their writings according to a narrative of perpetual discovery. According to this narrative, women musicians must wait for an external agent—such as a producer, critic, or record label representative—to offer them a “break” in order to achieve professional success. When such breaks do arrive, however, they are never sufficient to lift these women out of obscurity.

Feather's first five “Girls in Jazz” subjects are white women. He typically frames them as brilliant—and shapely—musicians facing a bleak future and, by extension, positions himself as their champion:

A good-looking redhead who sings, and can play the coolest trumpet this side of Miles Davis—it sounds like the stuff of which hip dreams are made. But it hasn't done Norma Carson much good.Footnote 76

Mary Osbourne, girl singer and girl guitarist extraordinary … still has youth and beauty and talent, but it is hard to say how long these qualities will endure before she can be considered to have missed the gravy train forever.Footnote 77

Feather's article on pianist Beryl Booker—to the best of my knowledge, his only profile of a Black musician for “Girls in Jazz”—describes her as “the greatest girl pianist since Mary Lou Williams” and “the female Erroll Garner” but “plagued” by a series of “bad breaks”: “She was to play the Paris Jazz Festival in 1949 but had to beg off when pneumonia trapped her. She started a new solo career in New York recently but left suddenly…when pleurisy set in.” Although he notes that she has performed with Slam Stewart's trio and the Austin Powell quintet, toured with Dinah Washington, and recorded numerous sides, Feather describes Booker as still in need of a “real break.” He hopes that she might soon see “the first glimpses” of one due to interest from producer Bod Shad and agent Billy Shaw.Footnote 78

The “Girls in Jazz” profiles take a formulaic approach, typically quoting the featured artist on the challenges of being a woman in jazz, detailing her childhood and musical influences, briefly surveying her professional career while emphasizing that she has yet to reach her potential, and, where relevant, highlighting her tracks on the Girls in Jazz album.Footnote 79 Charles Emge joined Feather for the series in July 1951 with his profile of Smock, with a headline (“Addition To ‘Girls In Jazz’ Found On Coast By Holly”) that makes no mention of her but rather speaks to a friendly competition between the two men. Emge opens by quoting Smock on the difficulty of “get[ting] anywhere in the musical profession” given that “[a] lot of people think there's something…unladylike about a girl jazz musician… Just another problem we have to face.” He dubs her “the No. 1 girl jazz violinist in the business” but documents no professional accomplishments other than her Girls in Jazz sides and a vague reference to her television appearances. The profile ends with a paraphrase of Smock that attributes women musicians’ lack of success to a desire for domesticity: “Ginger, despite all the handicaps she's encountered, still thinks the main reason girl musicians rarely make the top brackets is that they find it much easier to marry, settle down and raise families.” Emge's narrative style leaps from discovery to discovery: First by Feather, who “pass[es] on” a “tip” to Emge, then Emge's own “belated ‘discovery’ of Ginger via her guest appearances on local TV shows,” and finally a suggestion that Smock might “get her long-deserved and long-delayed ‘break’ in the new medium” of television. Although the accompanying photo is of Smock, the caption is about Feather and Emge, describing them as intrepid explorers of “every gal musician in sight.”Footnote 80 This is the crux of the narrative of perpetual discovery: It divests power from the objects of such “discoveries” and instead grants agency to the (male) “discoverers.” Effaced are the day-to-day working lives of these women.

Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham has argued for race as a “metalanguage” with a “powerful, all-encompassing effect on the construction and representation of other social and power relations, namely, gender, class, and sexuality.”Footnote 81 In the early 1950s, DownBeat had a complicated relationship to race. On the one hand, the magazine decried instances of racial discrimination, from the Jim Crow South to Los Angeles’ segregated musicians’ unions.Footnote 82 On the other, it was adamant that such inequities did not exist in jazz—except against white musicians, which it dubbed “Crow Jim.”Footnote 83 Thus, in May 1951, DownBeat devoted over a full page to an interview with Roy Eldridge in which the trumpeter describes being denied hotel rooms and harassed in venues while on tour with Gene Krupa and Artie Shaw in the 1940s. Nevertheless the headline singles out Eldridge's statement that, after a year of performing in Europe, he wants “never in my life [to] work with a white [American] band again!” In subsequent issues, it is to this assertion that DownBeat returns, accusing Eldridge of reverse racism.Footnote 84 The “Girls in Jazz” series likewise expressed concern that white women might be victims of “Crow Jim”—Feather writes that Marian McPartland has “three hopeless strikes against her” in the eyes of French jazz fans because she is “English, white, and a girl”Footnote 85—but avoided any mention of race for Black women. In short, DownBeat allowed space for collective grievance within jazz for white male musicians, its primary readership, and occasionally extended that collectivity to white women, but not to Black men or women.

White women musicians profiled in DownBeat in the early 1950s fell somewhere between pin-up girl, virginal innocent, and devoted wife.Footnote 86 Leonard Feather consistently mentions his white subjects’ physical attractiveness and marital status: Pianist Barbara Carroll is a “young brunette” hoping to marry (to Feather's dismay); Marian McPartland is a “tall, laughing chick with [a] happy disposition” and “half of… a ‘Dixieland vs. bop’ connubial team”; and bassist Bonnie Wetzel—even if her fingers are “covered with rough, ugly calluses… [and] big, bleeding blisters”—is “lovely to behold,” but a widow (her husband, trumpet player Ray Wetzel, having died young in a tragic car accident).Footnote 87 Charles Emge labels white harpist Corky Hale “as cute as her name” and a natural for “cheesecake photos,” and asks if she is dating (she is not). He peppers her with leading questions and reports her non-sequitur responses with glee: When he asks for her “favorite girl musician,” for instance, she replies with accolades for the Charlie Ventura sextet and the Woody Herman band.Footnote 88 Emge used this aggressive interview style in other articles on white woman instrumentalists, too. The previous year, he had bragged about his attempts to “trap” bandleader Ada Leonard into a “scrap” with fellow bandleader Ina Ray Hutton by asking questions such as, “What about those gowns Ina wears? They're so tight, everyone is waiting—and hoping—for an accident.”Footnote 89 A generous reading suggests that Emge was willing to offer white women instrumentalists his grudging respect provided they demonstrate that they could hold their own against prurient remarks by white male colleagues.

Meanwhile, the two “Girls in Jazz” profiles of Black women—Ginger Smock and Beryl Booker—absent their bodies entirely. Although Emge “discovers” Smock via the visual medium of television, he makes no mention of her appearance or stagecraft, and his trademark sexual innuendo is lacking. Feather likewise includes no physical descriptors for Booker, instead characterizing her as poor and family oriented: She grew up in a large family that could not afford music lessons, earned her musicians’ union dues by waitressing at $5 per hour, supported her young daughter from a short-lived early marriage by playing Philadelphia bars, and later stopped gigging to care for her terminally ill mother.Footnote 90 Both men also studiously avoid any mention of race. At times, this borders on the absurd, as when Emge writes that Smock “thought she was headed for the [classical] concert stage… [b]ut, like thousands of other good violinists, she didn't make [it],” with no mention of the fact that the color of her skin would have precluded her from such a career in the early 1940s. This is no politics of respectability, as per Higginbotham, in which the “reform of individual behavior and attitudes” is also “a strategy for reform of the entire structural system of American race relations,” for in disallowing race Feather and Emge disallow the possibility of an African American collectivity.Footnote 91 Rather, they implicitly connect Black female sexuality, and even corporality, to presumptions of impropriety by granting space to these women only after evacuating any mention of their bodies.

Although credit is due to Feather and Emge for tackling gender bias in the industry, the “Girls in Jazz” profiles suggest a certain voyeurism that watches both Black and white women fail while fetishizing female obscurity. The series uses a variety of mechanisms to circumscribe the place of both white and Black women instrumentalists in DownBeat and, by extension, in professional jazz: Depicting them as passive actors waiting for a break that never comes; emphasizing that technical prowess on an instrument is no guarantee of success for a woman; reassuring a readership of primarily white male musicians that white women could succeed in jazz only so long as they remained physically attractive; and, in the case of Black women, absenting their race and their bodies in order to portray them as morally sound. Taken together, these techniques delineate the different spaces allocated to white and Black women instrumentalists in jazz, while maintaining a near-unbreachable chasm between the categories of “girl” and “professional jazz musician.” What complicates the picture in Smock's case is the fact that, as per her later letters and interviews, she also seems to have understood her career in these terms.

“Wherever You Were, People Flocked To”: The 1950s and 1960s

The 1950s were, in many respects, the height of Smock's career, even as Central Avenue declined as a musical hotspot and cultural hub.Footnote 92 She was a recognized television personality, appearing on multiple shows. In early 1952, after she signed a contract as a regular cast member for Dixie Showboat, where she was “The Swinging Lady of the Violin” and “The Lovely Lady of the Violin,” Jet magazine noted that she was the “only Negro musician regularly appearing on television on the West Coast.”Footnote 93 Her gigging continued apace, including slots at Las Vegas’ Jungle Club in late 1951 (with the J. C. Heard Trio) and Club Oasis in Los Angeles in early 1952, where she played “many of her own compositions in addition to popular request numbers.”Footnote 94 In 1953, she toured the West Coast with the Jackson Brothers Orchestra, a jump blues band, performing at the Say When in San Francisco, the Tropics in Portland—where they were billed as a “hard-driving ‘go-go’ sextette”—and the Ernie Piluso Club in Eugene, Oregon. (Smock would marry Jackson Brothers bassist Harold Jackson, also known as Hal or Hack, in June 1954.)Footnote 95 While in San Francisco, Smock was approached by a representative from RCA Victor, who, as she later wrote to Reeves:

liked my playing so well, he rented a studio, made the tape, took it back to Hollywood to RCA. He played it for the rest of the execs there, they listened, said it was superb (especially my rendition of “Dark Eyes”[)] and asked him who was the artist.

Smock told this story on at least two occasions. In her letter to Reeves, the representative describes her to the executives as “a girl from L.A.” Their response: “They told him I had no-name and they could get Joe Venuti instead.”Footnote 96 When Smock retold this story to Sherrie Tucker in 1993, however, she added an additional detail: When the executives say, “Who on earth is playing the violin?” the representative says, “A colored girl up there in San Francisco,” and they respond, “Aw, forget it. We've got Joe Venuti.”Footnote 97 Putting aside the question of how Smock learned of this in-house exchange at RCA Victor, I note that this anecdote follows the same trajectory as that of her failed Twentieth Century Fox audition at age twelve: An industry insider offers her a potential break only to withdraw it due to her physical presentation—hair, skin tone, gender. As she wrote to Reeves, “Needless to say that ‘took the wind out of my sails’ in more ways than one.”Footnote 98 Smock would later link her lack of a record deal to her move to Las Vegas, saying, “[I] never did have anything out that was really worthwhile because I never got a chance to. I never had anyone to record me… I got discouraged and I went on into orchestral work.”Footnote 99

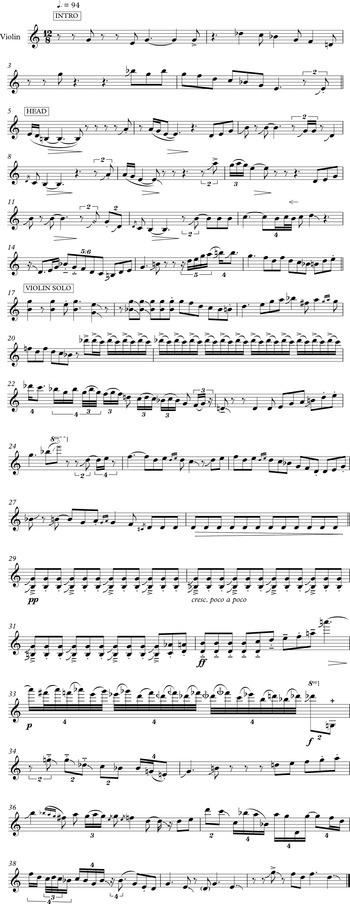

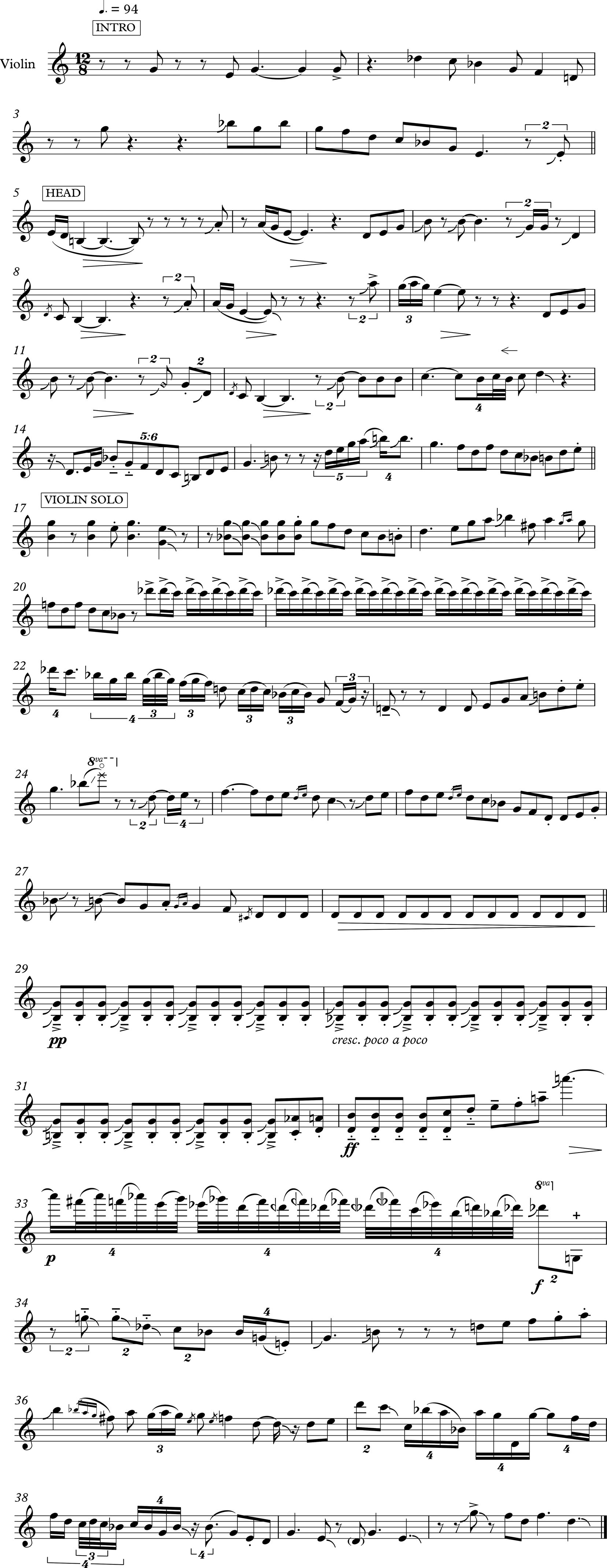

What might have been is audible in a 1953 recording of Smock's composition “Strange Blues” with Cecil “Count” Carter and his Orchestra (Figure 1; notated in 12/8 to indicate predominant triplet feel).Footnote 100 Her “flaming violin,” as hailed by the Atlanta Daily World, leads the band through the head and takes the first solo.Footnote 101 Smock's playing is rhythmically complex, technically demanding, and alternately strident and delicate, with long melodic lines spun out across the changes. She concludes her otherwise restrained statement of the head with a descending quintuplet and an unexpected mid-bar slide to a B (bars 14–15). A bluesy run leads back to the tonic chord, which Smock underscores with raucous double-stopped sixths intensifying into a Db-C ostinato (bars 16–21). Breaking up the prevailing eighth-note feel, Smock spins out a rapid run of descending sixteenth-note triplets before tracing an ascending G pentatonic scale and then a wild upward slide from a B flat (bars 22–24). The solo seems to draw to a close as the piano takes over, yet Smock's accompanying double-stops grow in volume and intensity and leap to a high A (bars 29–32). With her technical prowess clearly on display, Smock descends chromatically on rapid broken thirds, leaps again to reach the high Db, and counters that with a low G pizzicato (bar 33). Her solo closes by counterposing duplets and quadruplets against the prevailing triplet feel while mapping out ever-more-complex melodic descents, first from G, then from B, and finally from D (bars 33–39). We hear echoes of Stuff Smith's wide vibrato, conspicuous slides, horn-like phrase structures, and thoroughly bluesy harmonic language, as well as the sweetness of tone and technical virtuosity of the likes of Stephane Grappelli and Eddie South, but Smock's assertive, uncompromising sound, bold melodic gestures, and easy virtuosity are unmistakable. “Strange Blues” foregrounds Smock's artistry as a composer and soloist and highlights the loss of having so few recordings of her from the 1950s, a time when she was, in many ways, at the peak of her game as a jazz and blues player.

Figure 1. Ginger Smock solo on her composition “Strange Blues” (1953), as recorded on Federal 12130-B (78 rpm) with Cecil “Count” Carter and his Orchestra. Transcription by Laura Risk and Evan Price.

As a performer, Smock evinced something akin to the early twentieth century “blues culture” of urban, working-class Black women that has been traced by Angela Davis: Sexually expressive, independent, neither jezebel nor prudishly respectable, but rather, in the words of Patricia Hill Collins, “much closer to erotic sensibilities about Black female expressiveness, sensuality, and sexuality.”Footnote 102 In “Ginger Boogie,” recorded with the Jackson Brothers in 1953, Smock openly flirts with a male bandmate who sings, “I love to do the boogie with Ginger, ’cause Ginger puts it on my mind… Ginger, Ginger, Ginger, wanna park right in your stall.” After a few half-hearted objections to his request to “make it,” she cheerfully acquiesces and then, on his prompt to “rock me with all your might,” launches into a frenzied solo loaded with virtuosic pyrotechnics.Footnote 103 This did not preclude her from being a model of civic engagement on other stages, however, and she was a regular performer in church and for benefit events. In 1968, the People's Independent Church awarded Smock a certificate in recognition of 30-plus years of musical service to the community.Footnote 104

Smock's first and only stint on the national stage came in 1953–1955 with R&B ensemble Steve Gibson and the Red Caps, featuring singer Damita Jo. They toured the country, playing large venues such as Emerson's in Philadelphia (December 1953 and January 1954), Ciro's and Copa City in Miami (circa February/March 1954 and January/February 1955, respectively), and El Rancho in Las Vegas (circa September 1954).Footnote 105 The Philadelphia Tribune described a winning combination of stagecraft, virtuosity, and sex appeal:

That fine framed, personality girl with the raven tresses…and her golden violin held this southside spot's customers enthralled for four weeks. Ginger is all of this and more with her terrific driving style of syncopated bow-bending. She is a show all by herself… Stuffy [sic] Smith and his hawkish fiddling and Yehudi Menuhin wrapped into one mold. Despite the difficulty of playing in airish and large-sized clubs her amplified violin turns ‘em on…Ginger is the bombshell of the fiddle in more ways than one, if you let the men folks from hereabouts talk!!Footnote 106

Smock left the Red Caps for several months in mid-1954 over disagreements regarding “her length of tenure with the organization,” but was back with the band later that year for gigs in Las Vegas and Miami.Footnote 107 She split with the Red Caps for good in early 1955.

Smock returned to Los Angeles after 2 years on the road and her gigging continued apace: Featured in a “Sexsational! Glamourous! Floor Show” at Club Californian (top billing went to “Jeni, The Cherokee Charmer”); performing at the Club Mar-lin with Harold Jackson and his Tornados; and her only known film appearance, a bit part as an Egyptian court musician in Cecil B. DeMille's “The Ten Commandments.”Footnote 108 At the Rubaiyat Lounge of the Watkins Hotel in 1956 and 1957 she was “The Bronze Gypsy and her Violin,” attracting “large crowds nightly,” and her fans at the integrated venue included Hollywood actors Mantan Moreland, Pauline Myers, and Luukialuana Kalaeloa (Luana) Strode; bandleader Cab Calloway; and boxer Kid Gavilan.Footnote 109 In 1957, she was “Queen of the Violin” with The All-Star Four (Travis Warren, Hammond organ, Tommy Askew, piano, Sharkey Hall, drums) for a weekly television show on KCOP-TV Channel 13. Originally scheduled for just 13 weeks, some version of this show seems to have continued through 1960, eventually acquiring the title Rhythm Review.Footnote 110 Smock also guested on the Larry Finley Show, on Spade Cooley's popular The Hoffman Hayride (KTLA-TV), and on “Club Checkerboard” (KTLA).Footnote 111 Increasingly, she gigged in Las Vegas as well, playing both The Sands and the Moulin Rouge, Las Vegas’ first integrated casino, with Charlie Pryme in 1955.Footnote 112 In 1958, she was with Jack McVea's band at Town Tavern, the only Black-owned and operated club in Las Vegas.Footnote 113

In 1959, Smock launched a new band, the Aristocats—soon renamed “The Shipmates and Ginger”—with Art Maryland (guitar), Al Mitchell (guitar, trumpet), and LeRoy Morrison (bass). For several years in the early 1960s they wintered in Las Vegas, playing venues such as the Flamingo, the Frontier, and the El Cortez, and summered in Los Angeles, where they were the house band on the S.S. Catalina, a cruise ship that ran daily between San Pedro and Catalina Island. Smock was the first woman musical director for the S.S. Catalina and the Shipmates were the ship's first African American band in three decades.Footnote 114 Several years ago, I received an email from someone who had heard the band on an eighth-grade field trip, with the following description: “The music was different than anything I had ever heard—the rhythmic acuity of Ms. Smock and the whole group was astounding! Mainly jazz, with some blues, Latin, and pop songs.”Footnote 115 As noted above, the Shipmates recorded one LP of “original island music”; this was Smock's only full-length album to be released in her lifetime.Footnote 116 (Smock would meet her third husband, Bob Shipp, at a Shipmates engagement in Salinas, CA.)Footnote 117

Smock continued playing club dates, performing as a “Fabulous Swinging Gypsy of the Jazz Violin…Direct from Rumania” [sic] at Archie Moore's Restaurant in 1964, and bringing her “swinging Quartette” to the Tikki in 1965 and her “swingsational jazz violin” to the Parisian Room in 1970.Footnote 118 “Wherever [she was], people flocked to,” recalled Bette Yarborough Cox. “If it was a restaurant, they flocked to eat there, and if it was a supper club or whatever, they were there, following Ginger.”Footnote 119 Her repertoire remained a mix of standards, popular songs, and blues, though she had a special interest in “Gypsy”-themed repertoire, such as “Play Gypsy Play,” “Play Gypsies, Dance Gypsies,” and her signature, “Dark Eyes” (“Ochi chyornye”).Footnote 120 These are not actual melodies from one of the European populations commonly called “Gypsy” or “Tzigan,” of course, but rather early twentieth-century popular songs following in the tradition of, to use Brian Currid's words, the “Gypsy” as “a centerpiece of the cultural fantasies of Central European art music.”Footnote 121

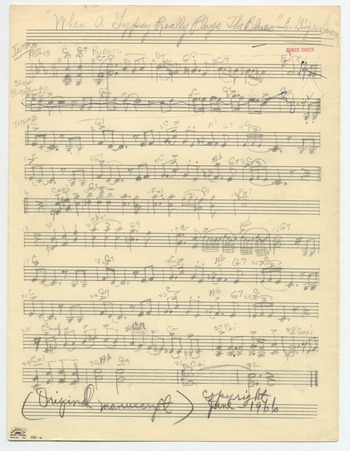

Performing “Gypsy”-themed melodies allowed Smock to show off both her classical chops and her jazz skills (and adhered to a common trope of the “Gypsy violinist” in both genres). By her own account, however, it also pointed to something deeper. In the early 1980s, she sent John Reeves a cassette dub of some of her earlier recordings, with spoken commentary before and after each track. After “Play Gypsies, Dance Gypsies,” recorded live in 1967, Smock says, “Basically, I presume I was once a Gypsy when I was here before, maybe 500 years ago.” And then she laughs awkwardly.Footnote 122 Smock's self-identification as a reincarnated “Gypsy” invokes the romantic stereotype of, in Corradi's words, the “‘happy Gypsy,’ beautiful and seductive, who freely wanders around the world”—and, in Smock's case, through time.Footnote 123 Nevertheless imagining herself as a “Gypsy” reborn into the body of a twentieth-century African American woman may have offered Smock a way to make sense of the many liminal spaces that she inhabited. She rarely spoke openly of the interstices of identity at which she found herself, instead expressing herself obliquely through offhand remarks and seemingly casual asides—always softened by her trademark “smiles!”—in interviews and letters. She negotiated identity not verbally but musically; through performance, through her choice of repertoire, and through her compositions, such as “When a Gypsy Really Plays the Blues” (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Ginger Smock, “When a Gypsy Really Plays the Blues” (comp. 1966). Ginger Smock Archives, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Lydia Samuel Bennett. Digital copy reprinted with permission from the personal collection of Lydia Samuel Bennett.

“I Finally Got Discouraged”: Ginger Smock in Las Vegas

Ginger Smock recentered her career on orchestral work in the 1970s. In Los Angeles, she performed with the George Rhodes Orchestra at the Now Grove from April 1970 to February 1971, backing Sammy Davis Jr., Johnny Mathis, Connie Stevens, and Dionne Warwick.Footnote 124 In Las Vegas, where she and Shipp lived from 1971, she was concertmaster at The Tropicana and then moved to The Flamingo, backing Gladys Knight and the Pips, Jack Jones, Tony Bennett, and others.Footnote 125 She played Caesar's Palace for a decade, accompanying Diana Ross, Frank Sinatra, Julie Andrews, and her “favorite star,” Sammy Davis Jr.Footnote 126 An intriguing note in the Los Angeles Sentinel from 1972 seems to suggest that she had a hand in integrating showroom orchestras: “DON'T know when we have heard such great news as learning that violinist Ginger Smock is now a full member of the Antonio Morrelli Orchestra at the Las Vegas Sands in Vegas … Of course, this is a first.”Footnote 127 Nevertheless in her correspondence with John Reeves, Smock makes it clear that this work was a regrettable necessity, the disappointing outcome of a jazz career that had never quite taken off as she'd hoped.Footnote 128

Reeves cold-called Smock in 1973 to request copies of her recordings, but their conversation quickly turned to her past accomplishments, her hopes for the future, and her frustration at the limitations placed on her career:

Ginger Smock: I never got really a chance to play, you know, a real chance… I used to be on television here in Los Angeles. Several shows. A bunch of malarky… But I finally got discouraged and went on into playing orchestra work because I just didn't quite make the grade as a soloist.

John Reeves: And yet you play terrific jazz.

GS: Well, I don't know about being so terrific, but just nice, you know. I can play. I've had the pleasure of Stuff Smith putting his violin up and giving up. And Eddie South got mad and walked out of the club one night because I stood up and played against him.

When Reeves suggested that she might receive more recognition were she to perform in Europe, Smock replied:

They say they're very responsive [in Europe]. Well, Stuff [Smith] was telling me, when he went to Paris and then he played all in through there. You know, he died over there… He always called me his daughter. And [Joe] Venuti called me his daughter. The two of them called me their daughters. I was quite flattered ’cause each one would say that… I must have been their kid, because I played like both of them, you know. And so, anyway, Stuff came back saying that it's too bad that I never went to Europe because they would have, you know. But I guess somewhere along the line just—I got a little discouraged and just didn't bother … I didn't seem to have gotten an agent or somebody that was interested enough. You know, you can't do things by yourself.Footnote 129

Remarkable in this exchange is the contrast between Smock's descriptions of besting Stuff Smith and Eddie South in cutting contests, and of Smith and Venuti claiming her as their musical “daughter,” and her assertion that she never really had “a chance to play” because she lacked “somebody that was interested enough.” Smock worked with agents, promoters, and record labels across her career but none, it seems, offered her the break she felt she deserved. In her telling, she had the raw talent but not the professional spaces in which to develop it. Eventually, she “got tired of so many ‘doors’ being closed in my face.”Footnote 130

John Reeves promised to “try to get the people that matter interested in giving you the chance to prove them stupid in the past” and began writing to labels and promoters.Footnote 131 Smock, for her part, recorded several new demos.Footnote 132 Producer Joachim Berendt expressed interest in making an album for MPS Records, which had issued the legendary Jazz Violin Summit, but withdrew his offer after label executives stated that they already had “the great violinists” on MPS and did not need Smock as well.Footnote 133 When Claude Nobs then refused Smock a spot at the Montreux Jazz Festival because she did not have a record deal, Smock's bitter reply to Reeves is all the more cutting for its flurry of exclamation points, underscores, faux-Irish colloquialisms, and emoji-like “smiles”: “Rejections, rejections! the story of me life! smiles! Oh, well, when it's the proper time we'll go to the jazz festival with flying colors, eh? Why not? … Can't win ’em all, just want to win some. smiles!”Footnote 134 Meanwhile, her health was in gradual decline, her hands stiffening with arthritis and her eyesight worsening.Footnote 135 In the end, none of Reeves’ efforts panned out. Smock's orchestral work diminished, and the hoped-for recording and European tour did not materialize.

Smock was acutely aware of the late-in-life successes of her fellow jazz violinists. Stuff Smith restarted his career with a 1957 recording produced by Norman Granz (whom Reeves would later approach about an album for Smock).Footnote 136 After his 1967 comeback at Dick Gibson's Jazz Party in Colorado, Joe Venuti recorded dozens of albums and toured extensively. Johnny Creach, who lived and worked in Los Angeles from the mid-1940s, rose to fame as Papa John Creach when he joined Jefferson Airplane in 1970. Each of these musicians was celebrated as an elderly statesman of the instrument in his later years and accessed a higher degree of stardom. This was the trajectory that John Reeves sought for Smock—and that Smock sought for herself. In his press releases, Reeves labeled Smock the “Cinderella of jazz violin,” implicitly calling on record labels, festivals, and producers to act as her Prince Charming.Footnote 137 This, too, is a narrative of discovery, and there is an uneasy tension between John Reeves’ dogged pursuit of the festival gig or recording contract that would finally end the cycle of breaks-turned-rejections that, in Smock's telling, had defined her career, and the ways in which Reeves’ correspondence with an all-male, all-white set of power brokers reinscribes the purgatory of perpetual discovery.

What public recognition Smock did receive in the last decades of her life would come from another source; the Los Angeles-based BEEM Foundation (The Black Experience as Expressed Through Music), founded by Bette Yarborough Cox to document and celebrate the history of African American musical life in Los Angeles in Central Avenue's heyday. Invited to Los Angeles for a filmed interview as an “unsung musical heroine,” Smock thanked Cox profusely: “I'm so thrilled and grateful that you asked me. You don't know, this means an awful lot just to be asked and to be wanted.”Footnote 138 Smock returned to Los Angeles for BEEM Foundation events on several occasions over the following years, including performances with the Buddy Collette Trio and Quintet in 1985 and 1989, respectively (pianist Gerald Wiggins and bassist Red Callender were in both ensembles).Footnote 139 When she jammed with pianist Dorothy Donegan and trumpeter Bob Rodriquez at the BEEM Foundation's “First Annual Free Jazz Concert” in 1990, the Los Angeles Sentinel reported that “the roof appeared to be raised from its rafters.”Footnote 140 Nevertheless these were not the breaks she had hoped for and past injustices still rankled. “I still go through some stuff,” Smock told Tucker in 1993, “hoping someday that I'd be invited to a jazz concert or jazz festival, you know. And they would ask me to play. Like the Monterey Jazz Festival. I never was asked to that, yet… People of my age, caliber, there was just too many closed doors. A lot of talent went down the drain.”Footnote 141 Smock was voted into the Black Hall of Fame at the Black Museum of Southern California in February 1995. Four months later, she passed away at the age of 75.Footnote 142

Conclusion: “Are You a Musician?”

One of the loveliest recordings in the Ginger Smock Archives at the NMAAHC is a 1981 backstage jam session with Sammy Davis Jr.'s rhythm section. “Sammy's guys, piano, bass & drums, asked me to ‘sit-in’ between shows,” Smock wrote to Reeves. “We did—and surprisingly, it was a ‘blast’… [I am] kind of encouraged, think the ol’ gal has some spark left.”Footnote 143 The backstage sessions continued and, after a few nights, Smock brought her portable tape recorder. Her solos are relaxed and informal. She plays with a light, delicate touch and spins out long, melodic lines with little of her usual bravura. With her habitual showmanship absent, there is space for something else: An introspective musicality, a certain playfulness with the tunes, and even the possibility of mistakes.

At the time of this recording, Smock's orchestral work in Las Vegas was slowing down. Increasingly, her age was a liability. Three years earlier, she and her husband had pooled their savings to pay for a face lift because, as she wrote to Reeves, “They've been laying off the older and older-looking ones like ‘mad’ here. So, pain and all, I don't have much choice.”Footnote 144 For decades, she had successfully navigated an industry in which she had no choice but to perform both her music and her body when on stage. As she aged, however, fewer and fewer spaces in the industry aligned with the spectacle of her performing body.

As a young woman guesting on Dixie Showboat, Smock was granted airtime in part due to her willingness to play at musical ineptitude. When she was granted space in DownBeat, it was as a “girl” in need of a break and with her race, sexuality, and even corporeality evacuated. To be legible as a professional musician was, in these instances, to pretend that she was not yet one. Smock's story thus offers a particular set of historiographic challenges. On the one hand, she appeared often enough in African American newspapers that we can document her day-to-day life as a working musician with a high degree of accuracy. On the other, her later correspondence and interviews highlight the missing and retracted opportunities that marked her career: The gigs she didn't get, the albums she didn't record, the tours she wasn't offered. Her later recounting of the high points of her career was tempered by bitterness at what she perceived to be a lifetime of exclusion and the premature truncation of that career;Footnote 145 in one telling comment, likely a reference to rising star Regina Carter, Smock writes, “How about this young jazz violinist? Good for her. Glad she's accepted.”Footnote 146 A recuperative history of Smock must ask—following a question posed by Tucker—not only what she did that has been “omitted from historical memory,” and how we might “add it back in,” but also what she did not do, and how we might reinscribe those absences back into her narrative while still foregrounding her agency.Footnote 147

A narrative of perpetual discovery is, in part, an unrealized promise of historiographical space, where the break functions as a turning point between absence and presence. To position a woman as forever on the verge of unachieved success is another means of justifying her exclusion from history. Through a close reading of the full arc of Ginger Smock's professional life, from the nuances of her gigging and recording to her own retrospective reading of her career as one of lost opportunity, this article speaks not only to the rich detail of her life but also to the potential for that detail to be effaced in the blur of pre-discovery obscurity. It is with the sum total of her career—the music, the spectacle, the rejections, the successes, and the longevity—that we must answer the question posed to Smock on Dixie Showboat: “Are you a musician?”

Competing interests

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Laura Risk is assistant professor of music and culture in the Department of Arts, Culture and Media at the University of Toronto Scarborough, with a graduate cross-appointment at the Faculty of Music at the University of Toronto. Her research proactively builds out public archives in order to amplify unheard voices and critically interrogates the notion of tradition, with a focus on traditional music historiography in Quebec. She is also a fiddler.