In December 2020, Toronto's Against the Grain Theatre (AtG) released Messiah/Complex, which they describe as a “new interpretation of the Messiah with the goal of amplifying this unique moment of pride and inclusivity in Canada—honouring and giving support to Indigenous and underrepresented voices from coast-to-coast-to-frozen-coast, and hoping to share these voices with an international audience.”Footnote 1 Joel Ivany, AtG's Founder and Artistic Director, and Reneltta Arluk, Director of Akpik Theatre and of Indigenous Arts at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, directed four choirs and twelve IBPOC (Indigenous, Black, and People of Color) soloists who perform Handel's music in six languages: Arabic, Dene Kede, English, French, Southern Tutchone, and two dialects of Inuktitut/Inuttitut.Footnote 2 Streaming for free on YouTube during Christmas 2020 and the subsequent Easter and Christmas seasons, the film catapulted the indie opera company onto the world stage, garnering 144,819 views in forty-four countries after features in the New York Times, BBC, CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Company), and several other major media outlets.Footnote 3 Additionally, the digital album was nominated for a Juno award in 2022.Footnote 4

The COVID-19 pandemic and intensification of IBPOC activism during this time have prompted many in the classical music industry to pause and reflect on the ways in which we perpetuate colonialism and racism in our leadership and governance structures, programming, casting practices, performance practices, and treatment of IBPOC artists. AtG is one of many companies in North America whose pandemic programming was motivated by anticolonial and/or antiracist intentions. This article focuses on Messiah/Complex not to uphold it as a model for anticolonial art music but, rather, because its shortcomings have been lost on the many journalists who have done so.

My choice of the adjective “anticolonial” instead of “decolonized” is deliberate. Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang observe that “decolonization” has become a “metonym for social justice,” at least in the academy. They argue in favor of confining our use of decolonization to actions involving “the repatriation of Indigenous land and life.”Footnote 5 Examples within the arts include the Yale Union of Portland, Oregon, giving their building and land to the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation in July 2020.Footnote 6 The project “Xoxelhmetset te Syewa:l/Caring for Our Ancestors: Reconnecting Indigenous Songs with Community and Kin” can also be understood as decolonization in Tuck and Yang's sense. As xwélméxw (Stó:lō/Skwah) scholar and artist Dylan Robinson explains, he and his collaborators are “re-connecting kinship between Indigenous songs and material culture—variously understood as loved ones, ancestors, life—and the communities that they come from.”Footnote 7 Because Messiah/Complex did not involve the repatriation of Indigenous land or life, it is better described by a less specific term like anticolonial.Footnote 8

One of the many critical interventions Robinson has made in music scholarship has been to bring awareness to the idea of “listening positionality”: “how race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, and cultural background intersect and influence the way we are able to hear sound, music, and the world around us.”Footnote 9 My cultural background—as a second-generation Canadian of Mennonite and Polish ancestry—and training as a clarinetist in the Western classical tradition has made me into what Robinson refers to as a “hungry listener”; one more comfortable with songs as mere aesthetic objects than as beings with agency. I approached Messiah/Complex as someone who grew up watching my father perform Messiah every year in amateur choral groups. As a scholar, I have written about AtG's efforts to remake canonical operas for contemporary audiences.Footnote 10 Watching Messiah/Complex after having read Robinson's Hungry Listening (which had come out earlier in 2020) raised questions and concerns that had not arisen in my earlier writing on AtG.

Where I live and work, the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe peoples, a guiding principle of research and writing about Indigenous Peoples is “nothing about us without us.”Footnote 11 To center the experiences and perspectives of the Indigenous artists who created Messiah/Complex, I rely heavily on quotations from interviews and email exchanges I conducted as well as public Q&A sessions and roundtables on the film. Although all of the artists I spoke and corresponded with were satisfied with the end product, some mentioned ways in which the creative process could have been more supportive of Indigenous resurgence. For Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar, writer, and artist Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Indigenous resurgence or biskaabiiyang in Nishnaabemowin

does not literally mean returning to the past, but rather re-creating the cultural and political flourishment of the past to support the well-being of our contemporary citizens. It means reclaiming the fluidity around our traditions, not the rigidity of colonialism; it means encouraging the self-determination of individuals within our national and community-based contexts; and it means re-creating an artistic and intellectual renaissance within a larger political and cultural resurgence.Footnote 12

Based on conversations with several Indigenous artists involved in this project, this article argues that supporting Indigenous resurgence within Western classical music is going to involve more than merely hiring more Indigenous artists. We also need to give these artists the space to question what classical music is and how it should be created, presented, and appreciated. In other words, we need to move from thinking about how to include more Indigenous artists to thinking about how we can create space for Indigenous sovereignty. That is going to involve giving over the decision-making power to Indigenous artists at all levels and in all capacities, not just in roles visible to the audience. AtG gave the Indigenous artists they worked with more autonomy than typical collaborations in classical music. However, because these artists joined the project after several key decisions had been made, their ability to make Messiah their own had decided limits.

Against the Grain Theatre and Messiah

AtG is an indie opera company that focuses on presenting canonical repertoire in new ways. In a video on AtG's website, soprano Jonelle Sills describes the company as “giving new life to traditional operatic work and introducing it to new audiences. Their drive is to reach people who are not reached by [traditional] opera.”Footnote 13 Their shows are typically set in present-day Toronto. Unlike most updatings (e.g., much of Peter Sellars's work), Joel Ivany's productions feature new English-language libretti. For this reason, Ivany refers to his productions as “transladaptations.” Although remaining “congruent with the original libretto and music,” AtG seeks “to represent the characters’ circumstances and environments as belonging to and speaking to Canadians and Canada and the issues we face today.”Footnote 14

Most of AtG's shows are intimate, site-specific, and feature emerging artists, particularly from underrepresented groups. In 2011, they burst on to Toronto's opera scene with a production of La Bohème at the Tranzac Club. In the fall of 2019, AtG toured the production to bars in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and the Yukon. Due to their budget and chosen venues, AtG typically performs reduced arrangements (e.g., piano only for Bohème) with somewhat heavier cuts than is typical at the big houses. Otherwise, they make minimal changes to the score. The choices AtG made in Messiah/Complex are congruent with their earlier work.

Handel's Messiah is a decidedly unlikely vehicle for Indigenous resurgence, something AtG acknowledges as part of the land acknowledgment at the beginning of the film.Footnote 15 In the R/18 Collective's roundtable on March 23, 2021, musicologist Ellen Lockhart remarked that Handel composed Messiah at the “centre of empire. For centuries, it was a piece of British propaganda that was taken to different corners of the empire” to assimilate Indigenous Peoples into European and, specifically, Christian ways of thinking.Footnote 16 Handel was, furthermore, no innocent bystander. In 2013, librarian David Hunter found Handel's name in a 1720 list of investors in the Royal African Company, one of Britain's two official slave trading companies.Footnote 17 These investments cannot be neatly separated from Handel's creative work, Hunter notes. Handel used the profits to cover losses from his opera seasons in London. Furthermore, the very form of the English oratorio arose out of the patronage of James Bridges, the Duke of Chandos, patronage that was made possible by Chandos's own, much more substantial investments in the Royal African Company.Footnote 18

For many Indigenous people in Canada, Messiah calls to mind the genocide committed by church-run residential schools, which operated from 1883 to 1996.Footnote 19 In an effort to assimilate Indigenous Peoples into white, settler society, the Canadian government forcibly removed Indigenous children from their families and sent them to schools that were typically far away from their communities and ancestral lands. Children were beaten for speaking their languages or practicing their cultural and spiritual traditions. Abuse—physical, emotional, psychological, sexual—was widespread. Overcrowding and substandard sanitation, food, and health care led to countless preventable deaths. In the summer of 2021, remains of over a 1,000 children were discovered in unmarked graves on the sites of residential schools in British Columbia and Saskatchewan.Footnote 20

The answer to the question of why AtG decided that Messiah was the work to give “support to Indigenous and underrepresented voices” in 2020 has less to do with the artistic properties of Handel's work and its long and complex history than with plans AtG had in place prior to the pandemic. As AtG's Executive Director Robin Whiffen outlined in an email exchange with me in June 2021, AtG had planned to remount their fully staged/choreographed production of Messiah (2013, 2015) at the Winter Garden Theatre in Toronto in December 2020. The Toronto Symphony Orchestra (TSO) had engaged Joel Ivany to direct a semi-staged Rigoletto in winter 2021. Through Ivany's connection to the TSO, particularly the VP of Artistic Planning, Loie Fallis, these plans merged into Messiah/Complex.Footnote 21

The approach AtG took to creating something they could share with an online audience was influenced by the reception of their initial forays into virtual programming. In June 2020, they launched AtGTV on YouTube, which initially featured interviews with industry leaders and an online version of their Opera Pub series called Quarantunes.Footnote 22 Many of the Quarantunes concerts were recorded on the performers’ phones and broadcast live. AtG encouraged spectators to tune in at a specific time on their preferred social media platform (YouTube, FacebookLive, Twitter, or Twitch) and to share their reactions in the chat. Although AtG's live Opera Pubs were successful at bringing opera to new audiences, the Quarantunes series was not. As directors Atom Egoyan and Fiona Shaw note in their interviews with Ivany in the summer and fall of 2020, something is lost when one isn't sharing the same physical space with the singers, even more so with opera than with other performing arts because opera singing is typically unamplified.Footnote 23

With Messiah/Complex, AtG provided audiences with an experience that they could not get in a concert hall, including stunning aerial shots of the Kluane icefield and Saint Elias mountain range in the Yukon. Recording the audio and video separately not only allowed them to shoot outdoors but also to feature talent across Canada.

Whiffen recalled that their initial aim to have artistic representation from each of Canada's provinces and territories “quickly evolved into the desire to engage only soloists who were representative of racially marginalized communities.” She described her team as “deeply impacted by the resurgence of Black Lives Matter in May [2020].”Footnote 24 In discussions after the premiere, Ivany also named Black Lives Matter (BLM) as one of the chief inspirations for Messiah/Complex.Footnote 25

AtG's first response to BLM was to commission a blog post by Michael Zarathus-Cook, a Black music writer based in Toronto. In his post from June 19, 2020, he critiqued the “performative allyship” of diversity statements and token hires, and called on opera companies to give IBPOC artists “a seat at the table” and “a legitimate voice and presence in your boardrooms and conference calls.”Footnote 26 Subsequently, AtG invited Zarathus-Cook to chair two conversations about opera, racism, and other inequities in the industry, which they broadcast on FacebookLive on June 30 and July 1 (Canada Day), 2020.Footnote 27 The tenor of these conversations was similar to the conversation J'Nai Bridges and the LA Opera hosted on June 5, 2020, except that AtG's conversations featured emerging (rather than established) IBPOC, queer, trans, and differently abled artists.Footnote 28

Inspired by these conversations, AtG decided to hire only IBPOC soloists. With seven Indigenous soloists and an Indigenous co-director, Messiah/Complex became less about BLM and more about Indigenous resurgence. Notably, AtG not only reached out to Indigenous opera singers like Deantha Edmunds and early music specialists like Jonathon Adams, but also to musical-theater singers (Julie Lumsden) and singer-songwriters (Diyet, Leela Gilday, and Looee Arreak). In so doing, they showcased a variety of ways Indigenous artists are pursuing careers in music and engaging with colonial structures such as the classical music canon.

Joel Ivany, a white settler, initially spearheaded Messiah/Complex. As part of the casting process, he consulted with Reneltta Arluk, a theater director of Inuvialuit, Cree, and Dene ancestry, whom he knew from his work at the Banff Centre. She recommended nêhiyaw michif (Cree-Métis) baritone Jonathon Adams, who suggested that Arluk be invited to co-direct. In my interview with Adams on April 18, 2021, they noted that “the Indigenous participants really needed to have an Indigenous leader because of the content and because of the history of Messiah and the piece and Canada. It was important to decentre whiteness, to decentre that Euro-centricity that's so much a part of the annual Messiah tradition.”Footnote 29 The other Indigenous soloists agreed and Arluk took the lead on the direction of their numbers.

Indigenous–Settler Collaborations in Canada

Canada's Multiculturalism Act of 1988 has encouraged an increasing number of collaborations between artists trained in Western classical and Indigenous musics.Footnote 30 In his study of these collaborations, Dylan Robinson notes that inviting Indigenous artists to participate in Western art music “could be understood as seeking to redress a history of compositional ‘resourcing’ and appropriation of non-Western music … . Yet to include Indigenous and non-Western musicians in such work may just as easily take part in a representational politics that does not necessarily address the structural inequities that underpin inclusion.”Footnote 31

Robinson exposes the unequal power dynamics governing many well-funded and publicly praised musical collaborations, such as Tafelmusik's The Four Seasons: A Cycle of the Sun (2003–7, 2013), featuring Inuit throat singers Sylvia Cloutier and June Shappa, Jeanne Lamon on violin, Aruna Narayan on the Indian sarangi, and Wen Zhao on the Chinese pipa. He gives Tafelmusik's Four Seasons as an example of “inclusionary music.” Musicians from other traditions have been included, but only because they have agreed to conform to the norms and expectations of Western classical music. In the documentary The Four Seasons Mosaic (2005), Lamon described the difficulty of getting Cloutier and Shappa to be “totally reliable and perfect every time.”Footnote 32 As Robinson notes, the expectation that throat singers conform to the precisely measured nature of Baroque music and perform in precisely the same way each time “is to overlook the very nature of throat singing as play and the flexibility of time in play.”Footnote 33 The problem with merely including Indigenous artists, without altering existing ways of working, is that even the “best intentions of integration continue to reinforce and maintain the hierarchical dominance of art music as the genre to which other music must conform.”Footnote 34

For this reason, Robinson finds more promise in the approach he terms “Indigenous + art music,” which foregrounds (instead of attempting to efface) the irreconcilable nature of Western classical and Indigenous musics. As seen in Tafelmusik's Four Seasons, these musical traditions not only contrast in terms of aesthetics and modes of production and appreciation, but also in terms of their assumptions about the ontology of music. Although classical musicians regard musical works as objects for aesthetic contemplation primarily and only secondarily in terms of other sorts of functions they may perform, in many Indigenous cultures, Robinson notes, songs function “as law, medicine, or primary historical documentation.”Footnote 35

Writer and arts consultant Soraya Peerbaye and violinist and ethnomusicologist Parmela Attariwala make similar recommendations in “Re-sounding the Orchestra: Relationships between Canadian Orchestras, Indigenous Peoples, and People of Colour,” a 2019 report commissioned by Orchestras Canada. The Indigenous artists and artists of color they interviewed “argue that, while inclusion may increase the representation of a group within a system, it does not alter the fundamental dynamics of that system, or their level of control within it.” Unfortunately, the “initiatives described by administrators and artistic directors [they interviewed] were primarily (though by no means exclusively) about access, inclusion and diversity; in other words, they included Indigenous artists and artists of colour, but did not necessarily change or cede the values, practices and protocols of the orchestra.”Footnote 36 Similarly to Robinson, Peerbaye and Attariwala argue that we need to move beyond inclusionary approaches and toward creating space for sovereignty, particularly for Indigenous artists but also artists of other historically marginalized groups.

Messiah/Complex: Singer Agency and Language Reclamation

Messiah/Complex began from a different starting point than most performances of Messiah or of Western classical music more generally. In a public Q&A AtG hosted on April 1, 2021, Spencer Britten, a Chinese-Canadian tenor, described his surprise that the first question Ivany asked him was “Who is Spencer and how can we represent that?” rather than the more familiar starting points of “How is this aria traditionally performed?” “What did the composer intend?” or “What does the director want to say?”Footnote 37 At the same event, Dene singer-songwriter Leela Gilday described being given an “open invitation to take the piece, whatever piece I chose, and make it my own.”Footnote 38 In the interview I did with Gilday on April 19, 2021, she added that she was “invited to be a collaborator. I chose the aria that I would sing. I decided what I would do with that aria, and none of it was prescriptive.”Footnote 39

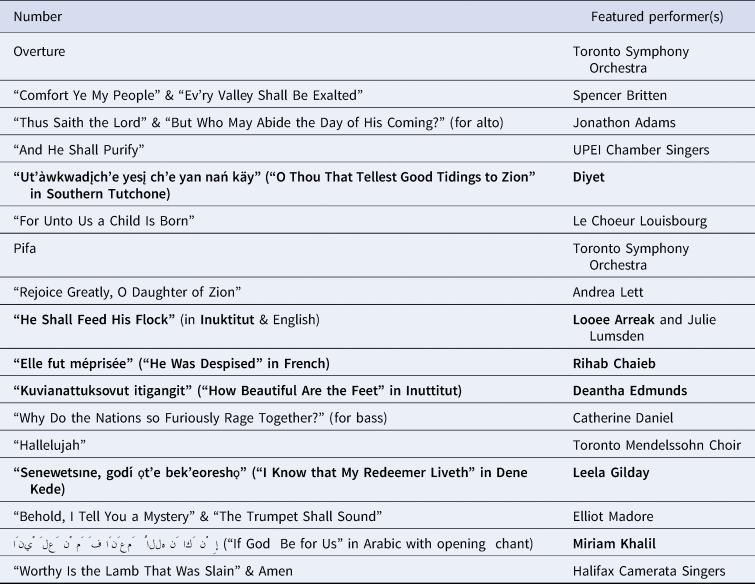

Table 1 lists the arias the singers chose. Jonathon Adams and Catharine Daniel selected arias not intended for their genders or voice types. Adams performed the most commonly heard version of “But Who May Abide the Day of His Coming?” As a singer who specializes in historically informed approaches to Baroque music, Adams has performed the original setting of this text for bass, but not this later version Handel composed for the alto castrato Gaetano Guadagni.Footnote 40 In their interview with me, they explained that the alto version was commonly performed by basses in the nineteenth century and that its fiery coloratura is better suited to the images of Alberta's “refinery alley” that accompanied their performance in Messiah/Complex.Footnote 41

Table 1. AtG's Messiah/Complex (2020)

The singers also decided what language to perform in (in Table 1, numbers in languages other than English are in bold).Footnote 42 When Ivany approached Diyet, a Southern Tutchone singer-songwriter from the Kluane First Nation, her initial reaction to performing in Messiah was “no thanks.” After completing a bachelor's degree in Western classical voice at the University of Victoria, Diyet decided to walk away from that tradition and write her own music. As she explained to me in an interview on July 6, 2021, Ivany was not only asking her to return to classical music after a 20-year hiatus, but to do so performing a piece written “at the peak of British colonization” about the “coming of Christ.” Diyet's mother is a residential school survivor. Like many Indigenous people of her generation, Diyet's “relationship with the Christian religion is not positive.” What eventually convinced her to participate was Ivany's invitation to “reinterpret what this music can mean to you as an Indigenous person living where you live and the life that you live.” The only way she could feel “confident and comfortable doing this” was to “completely flip [Messiah] on its head: either sing it in my language or rewrite it.”Footnote 43

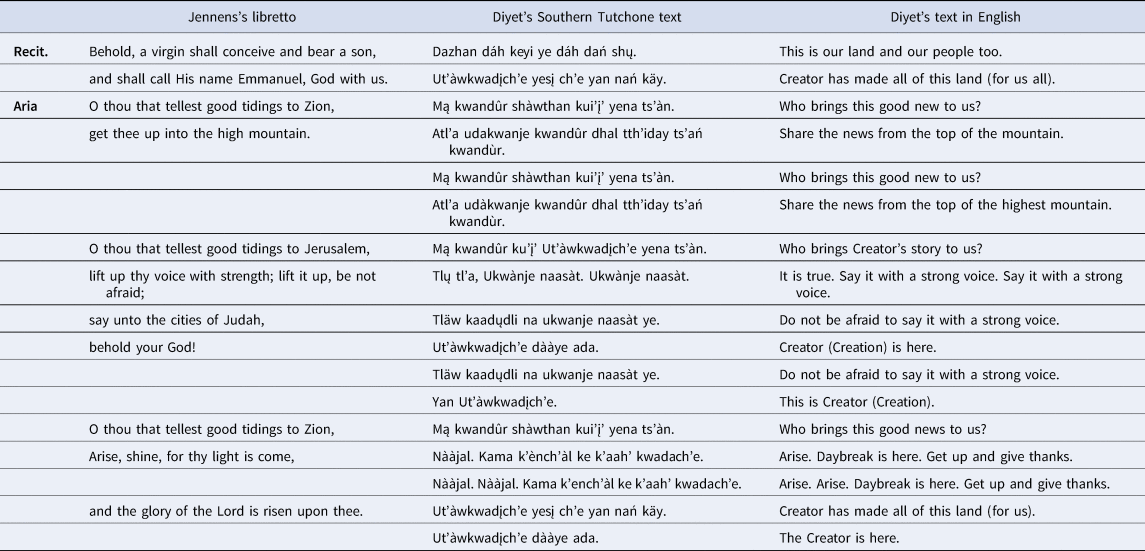

Diyet decided to perform “O Thou That Tellest Good Tidings to Zion” in Southern Tutchone (Table 2). She picked this number because its text reminded her of the land on which she lives—on the Saint Elias mountain range, home of the highest peak in Canada—as well as her people, who identify as mountain people.Footnote 44 She worked on the Southern Tutchone text with her grandmother, one of the few fluent speakers of their dialect. Diyet described their text as a “retelling” rather than a direct translation. Because Southern Tutchone is a tonal language, they needed to take liberties with the Biblical text “to find the right words that fit within the tone realm of what was happening musically.”Footnote 45 Their translation also involved a shift from Christian to Indigenous worldviews. The “good tidings” of which Diyet sang are not that “a virgin shall conceive and bear a son” but that “Creator has made all of this land (for us all).”

Table 2. Jennens's libretto and Diyet's text in Southern Tutchone and English

Reproduced with permission.

Language reclamation was also one of the main reasons Leela Gilday participated.Footnote 46 With translation assistance from her mother and aunties, she performed “I Know that My Redeemer Liveth” in Dene Kede (Table 3). In the R/18 Collective's roundtable, Gilday explained that she “threw the libretto out and rewrote it” to reflect her own spiritual beliefs, which are based on Dene spirituality.Footnote 47 Like Diyet, Gilday removed all references to God and Christ. In the promotional spotlight AtG released on their website prior to the initial airing of Messiah/Complex, Gilday provided the following gloss: “I talk about the spirit of the land, the water and the earth—the whole world. And then I speak about transformation. When you pass away, your spirit transforms—I believe in the Creator, and that when you pass away, you join the Creator.”Footnote 48

Table 3. Jennens's libretto and Gilday's text in Dene Kede

Reproduced with permission.

Similarly, Tunisian-Canadian mezzo-soprano Rihab Chaieb described “reclaim[ing] the Messiah as my own” by taking “Jesus out of the equation” in her performance of “He Was Despised” in French.Footnote 49 On the day of the recording, she decided to sing “Elle fut méprisée” to make a personal statement about the Islamophobia she and female members of her family have experienced since immigrating to Québec.Footnote 50 In June 2019, the Québec government under Premier François Legault passed Bill 21, which banned public employees from wearing religious symbols (including head scarves, turbans, and kippas) at work. Despite the bill's neutral title, “Act of Respecting the Laicity of the State,” it has predominantly affected Muslim women who wear the hijab.Footnote 51 Chaieb's mother has been on the receiving end of the increase in macro and microaggressions toward Muslim women who wear headcoverings.Footnote 52 Although Diyet, Gilday, and Chaieb all de-Christianized their performances, Chaieb's number was the only one that attracted negative attention in the YouTube chat.Footnote 53

Singers who decided not to perform in English also decided whether to have subtitles. Looee Arreak and Deantha Edmunds opted to leave their numbers in Inuktitut/Inuttitut untranslated.Footnote 54 Métis visual artist David Garneau notes:

The colonial attitude is characterized not only by scopophilia, a drive to look, but also by an urge to penetrate, to traverse, to know, to translate, to own and exploit. The attitude assumes that everything should be accessible to those with the means and will to access them; everything is ultimately comprehensible, a potential commodity, resource, or salvage. … The primary sites of Indigenous resistance, then, are not the rare open battles between the colonized and the dominant but the everyday active refusals of complete engagement with agents of assimilation. This includes speaking with one's own in one's own way, refusing translation and full explanations, creating trade goods that imitate core culture without violating it, and refusing to be a Native informant.Footnote 55

Refusing translation is one way to resist the colonial attitude. However, because the film lacked program notes, some viewers did not recognize this as an artistic and political choice.Footnote 56

Visual Storytelling

The singers also led discussions about the visual imagery that would accompany their musical performances. In my interview with Adams, they explained that they wanted their segment to expose “the colonial impact on the land.”Footnote 57 They filmed their segment on their godparents’ land in Sherwood Park County in Treaty 6 territory. They explained that refinery alley—showcased at the very beginning of their segment—is visible from the estate and has affected the water there.

Adams also wanted their segment to reflect their Two-Spirit identity.Footnote 58 Their spotlight on AtG's website provides a fuller explanation of the impetus for their number:

I'm from Alberta, so we started with the concept of refinery—associated with resource extraction. We created a character [played by actor Nathan Loitz] who is a refinery worker—and after work, as he comes back onto his land, which is a place where he feels safe, and he builds a fire for himself—contrasting the fire of industry he works with at the refinery. And then, I emerge.

I'm a representation of the forest, of the land, and being from the land—a timeless being. That's what I think of when I think of my own two-spirit identity—a feeling of oneness with nature, with the land and the water. Historically two-spirit people were medicine people. They carried out ceremonial functions, in many nations they were respected as knowledge keepers, and associated with wisdom.

Eventually, in the film, it becomes clear that the refinery worker and this two-spirit figure are connected—and as the worker comes closer, we embrace.Footnote 59

Arluk described their meeting as representing the worker realizing “how unnatural or how impactful land resource extraction is.”Footnote 60 Without changing a word or note of the aria, Adams completely changed its meaning in Messiah/Complex. The “He” of the Biblical text no longer refers to Jesus but to the Two-Spirit being Adams portrays.

Because of COVID-19 travel restrictions, Arluk and Ivany were not on set for all of the filming. Arluk, based in Alberta, was only able to be physically present for Adams's and Lumsden's shoots. Both Arluk and Adams attributed the success of Adams's segment to their ability to work together on location. In their interview with me, Adams explained that they “could respond to the light and the land. And our animal relatives were on site with us and guiding us. I really felt the presence of my ancestors there too, guiding us from place to place.”Footnote 61 Even though Arluk had storyboarded Adams's number, she confessed that if they hadn't been on set together, “I don't think that would have been the film we would have gotten, because we were changing the concept a day or two days before we shot it. … A lot of the shots didn't change, but the intention of the shots and the reason why the shots were shot really changed” to bring Adams's Two-Spirit identity to the forefront.Footnote 62 One way they did that was through the tattooing on Adams's chin and neck. “There was the practice of women having markings on their face and men having markings on their body in Cree culture,” Adams explained to CBC News. “With stage makeup, I made the image of a tattoo running all the way from my chin down onto my chest to represent what it means to be two-spirit.”Footnote 63

Gilday also stressed the importance of working with Indigenous directors and filmmakers. She has described her segment as a vision of Dene futurism. “Our ancestors are with us all the time,” she explained in AtG's public Q&A session. “We are still living that worldview and that traditional life though we may live our lives in the city. And the spiritual underpinnings of that are something that has gone on for thousands of years.”Footnote 64 Her number represents the change that comes over a Dene woman after participating in Dene Ceremonies, such as smudging and feeding the fire. Gilday stressed that she was filmed performing Ceremony, not merely pretending to do so.Footnote 65 Arluk explained the power of this decision in her interview with me: “the church punished us [in residential schools] and the government punished us [through incarceration] to do our ceremonial practice and her doing it on film during Messiah/Complex gives a sense of self-determination of spiritual practice.”Footnote 66 Gilday was initially hesitant about performing Ceremony on camera, citing that “our Ceremonies are not performative.” It was only because she was working with Dene filmmakers Amos Scott and Deneze Nakehk'o with whom she had worked before that she felt comfortable performing Ceremony in front of them and trusting that they would represent it in an appropriate light.Footnote 67

Sanctity of the Score

Deantha Edmunds, an Inuk opera singer, writer, and composer wanted her number to draw attention to the long history of European art music in Labrador. Moravian missionaries settled on the North Coast of Labrador in 1771 and brought music by Handel and other European composers. “The Inuit not only learned how to read and write this music,” Edmunds explains in her spotlight on AtG's website, “but they changed it over time and transformed it. They recomposed and reinterpreted it to reflect their culture and traditions.”Footnote 68 Tom Gordon, a musicologist who has cataloged the music in Moravian churches in Labrador, has argued that “despite its European origins, despite the fact that it was something that was imposed on them by the missionaries, [the Inuit in Labrador] regard this wholly as their own music, and with good reason, because over two hundred years, they have made it their own. It's no longer what it started as.”Footnote 69 Unfortunately, this story was not dramatized in the film itself. Only listeners who happened to peruse AtG's website would have discovered that this was not the first time Handel had been performed in Inuttitut. This point could have been articulated in the film itself if Edmunds was shown performing from historical sources and demonstrating the ways in which her people adapted this music, not only through translation but also through recomposition.

This missed opportunity points to a decided limitation of Messiah/Complex. The biggest change to Handel's score was the Melkite (Byzantine) chant Miriam Khalil performed in lieu of the recitative before “If God Be for Us,” which she performed in Arabic.Footnote 70

For an updating to involve revisions to the score is unusual within Western art music practice. Messiah, however, has received several notable musical modernizations including the 1992 album Handel's Messiah: A Soulful Celebration, which inflects Handel's score with elements of African American spirituals, blues, jazz, R&B, and hip hop. The following year, Marin Alsop delivered a similar aesthetic to live audiences in New York City with Too Hot to Handel: The Gospel Messiah.

An even more direct comparison comes from the Toronto-based company Soundstreams. They have been producing versions of their Electric Messiah since 2015. Like AtG, they opted for a streamable video in 2020, describing it as “a full-length music video that reimagines Handel's classic for today's world.”Footnote 71 In keeping with their mandate to showcase work by living composers and musicians, they made minimal changes to the texts and, instead, fit these texts with new music for harpsichord, shō, guitar, electric organ, turntables, and electronics. Influences on the 2020 Electric Messiah ranged from contemporary art music in the Euro-American tradition to electronic dance music (EDM), pop, hip hop, and folk.

Not all classical singers would be willing and able to don the hat of composer or arranger. However, because AtG invited Indigenous artists who work outside of the sphere of classical music, their cast of soloists included several seasoned songwriters and composers, including Gilday, Diyet, and Edmunds. There are several reasons why Messiah/Complex did not showcase their songwriting skills. The first is the project's leadership: Ivany is a stage director and librettist who specializes in updating the visual and textual components of canonical pieces.Footnote 72 Arluk also describes her work as “text-driven, being theatre-based.”Footnote 73 By contrast, composers and musicians have always been the driving force behind Soundstreams's Electric Messiah.

Second, AtG commissioned the TSO to supply backing tracks from Handel's Messiah before Arluk and the singers had been brought on board.Footnote 74 Thus, agreeing to perform in Messiah/Complex amounted to agreeing to perform Handel with the TSO. In my interview with Gilday, she described being given “free reign to rewrite the melody,” adding that she considered including melodic elements of traditional Dene songs, as she has done in her own compositions. She also thought about “adding other elements like the Dene drum,” but concluded that “it never was obviously appropriate.” Given that the TSO would be laying down their tracks first, the drummer would have had to follow the orchestra, rather than functioning in the traditional role as the leader of the ensemble. Moreover because the TSO would be performing Handel's score as written, Gilday noted that she “would have still had to write it within the chord structure of [Handel's] music.”Footnote 75

The tight production timeline also prevented more extensive musical adaptations.Footnote 76 Unlike Soundstreams, AtG had never produced a musically updated version of Messiah. “Just rewriting the lyrics and translating them into Dene Kede (which was not a direct translation) was a huge challenge and took quite a lot of time,” Gilday explained. When I asked her whether she would have been interested in recomposing the music in the style of her other creative work, she responded that this interested her, but that “it would have been a much larger project for me. I would have had to take pause to really see whether I would have been up for that in the middle of the pandemic when I've reinvented my career completely.”Footnote 77

In my interview with Diyet, she also expressed interest in undertaking musical changes that would have been “supportive of the language,” such as adding a traditional hand drum or rattle or having the chorus part (which was omitted) sung in Southern Tutchone or as a chant.Footnote 78 However, like Gilday, she noted that recomposition would have required more time. It also would have required more money to appropriately compensate singers who decided to take on additional duties as arrangers or composers.

In the R/18 Collective's roundtable, Ivany admitted that “from a musical perspective, we were only scratching the surface in terms of what could have been done.”Footnote 79 When I asked Ivany why they didn't explore more extensive musical adaptations, he admitted that they “contemplated having each artist decide their own instrumentation and [musical] interpretation, but thought it may not come across as cohesively. The project was already possibly going to be not the most unified with ten teams of filmmakers, different languages etc.”Footnote 80

Given that this film purports to represent Canada in 2020, a degree of incongruity (as heard in Soundstreams's Electric Messiah) is, arguably, desirable. Because of colonization and immigration, the peoples who currently reside on the lands known as Canada are not unified. Furthermore, as Robinson notes, when stylistic cohesion is achieved in collaborations between musicians trained in Western classical and Indigenous musics, it is typically the Indigenous musicians who are expected to compromise.Footnote 81

Of course not every singer would have wanted to change the score. As Jonathon Adams explained to me, their approach to “Indigenous resurgence through an early music lens is that we should perform the music as written. As a Two-Spirit, as a queer Indigenous person, me singing the music that was actually put upon us, was used to indoctrinate us in the colonizers’ language, but then reimaging the narrative framework and the impetus for that expression, that's what I think is really powerful.” They were concerned that changing the text or music may “send a message out that ‘this music is fine. This music doesn't have a problematic history. This music doesn't have a role in colonization and cultural genocide.’” In their segment of the film, they aligned “the role of the music to the role of the refinery.” They wanted their “visual narrative … to both include and accuse the source material in a way” by making “the words descriptive of and complicit in the genocide.”Footnote 82

Recording Process

Although Adams was pleased with their segment of the film, in their interview with me, they described the process as “very challenging,” not only because of COVID-19, but also because of “the way that we were offered [to participate].” Each singer had one Zoom meeting with the conductor, Johannes Debus, in which to work out the tempi and phrasing. Adams is accustomed to approaching tempi “from an affect-based place, in a rhetorical sense,” and through a “process-oriented way of working,” but was, instead, required to give a metronome marking.Footnote 83

The TSO recorded their portions at the end of September 2020, which were then sent out to the singers. Adams had a single hour in a recording studio to record their vocal tracks. Coming from early music, Adams is used to having considerable freedom in their musical interpretation. Because the TSO's part was pre-recorded, however, Adams had to “memorize exactly the number of beats that they left me for a cadenza.”Footnote 84 Given the health and safety measures in Toronto during the fall of 2020, it was not possible for even local singers to record with the orchestra. However, Debus could have been more responsive to the ways in which Adams wanted to collaborate.

Debus seems to have taken a different approach to his meetings with singers outside of the world of Western classical music. In conversation with me, Diyet described Debus as being remarkably open, even to the idea of performing new arrangements.Footnote 85 Due to time and budget constraints, however, the only major musical change to her number was the omission of the chorus parts. Both Diyet and Gilday described singing phrases for Debus and hearing him play the accompaniment back at the piano.Footnote 86 Diyet described trying out various tempi and eventually settling on a “happy tempo” that was slow enough that the words would be intelligible but fast enough that she would have enough breath to make it through each phrase. Both singer-songwriters were satisfied with the orchestra's recordings. Gilday described hers as “pretty much bang on to what we had discussed.”Footnote 87

Diyet and Gilday also had more positive experiences of the recording process than Adams did, but both spent much longer than an hour laying down their tracks. Gilday recorded herself at the home studio she built during the pandemic. Although Diyet recorded outside of her home, she also described doing many takes over multiple days with a producer (Matthew Lien) she had worked with before on traditional music in Southern Tutchone.Footnote 88

Although Adams wished that they could have “recorded in the same room at the same time,” Gilday surprised me by saying that this “wouldn't have been better for me. I probably never would have participated in a live setting to be honest with you. Being able to showcase my territory … The recording studio is much more forgiving than a live performance setting.”Footnote 89 When I asked her whether it would have been preferable to have recorded with the orchestra in the same room, she confessed: “I wouldn't have been able to make it through the piece. It's been twenty-five years since I sang opera. I had thirty takes. This was a unique situation. Maybe if I was a professional opera singer, it would be much better to be in person to record with the orchestra.”Footnote 90

Indigenous Protocols and Indigenous Resurgence

The restrictions imposed by COVID-19 not only allowed artists like Gilday and Diyet to participate but moreover to thrive. In other respects, AtG could have done more to support their Indigenous co-creators. The recommendations in this section are based on conversations I had with Indigenous participants. To protect their anonymity, I am avoiding direct quotations.

AtG was aware of Handel's investments in the slave trade as well as the associations Messiah may have for the Indigenous artists they were collaborating with.Footnote 91 Nevertheless, they did not give these artists an opportunity to meet on their own to discuss their feelings about performing this work or how their performance could further Indigenous resurgence. “While decolonization and Indigenization is collective work,” Garneau notes, “it sometimes requires occasions of separation—moments where Indigenous people take space and time to work things out among themselves, and parallel moments when allies ought to do the same.”Footnote 92 Garneau has created works that “visualize Indigenous intellectual spaces that exist apart from a non-Indigenous gaze and interlocution.”Footnote 93 Such spaces are important, he explains, because “when Indigenous folks (anyone, really), know they are being surveyed by non-members, the nature of their ways of being and becoming alters. Whether the onlookers are conscious agents of colonization or not, their shaping gaze can trigger a Reserve-response, an inhibition or a conformation to settler expectations.”Footnote 94

Creating spaces for Indigenous sovereignty within the creative process (as well as parallel spaces for settlers to reflect on their own relationships with Messiah and with Indigenous Peoples) would have supported the artists’ emotional and spiritual health and could only have enriched the final product. Importantly, the artists would have needed to be paid for this time in a way that is appropriate to the emotional and spiritual labor it demands.

Although several artists reached out to Elders for translation assistance and to talk through their involvement in Messiah/Complex, this was something they needed to seek out for themselves. Embedding keepers of Traditional Knowledge into the process for all participants would have relieved the Indigenous artists of the responsibility to find the supports they needed.Footnote 95 For settlers, such conversations could have been an opportunity to discuss how Messiah/Complex could, in Robinson's words, “make visible structures of settler colonialism and white supremacy that underpin art music's presentation and composition.”Footnote 96

Ceremony also could have aided Indigenous participants in working through their feelings regarding Handel's Messiah. Due to the pandemic, the possibilities for incorporating Ceremony were limited. Nevertheless, Arluk successfully incorporated Ceremony in Akpik Theatre's Zoom production of Pawâkan Macbeth, which aired May 1, 2020, during the early days of the lockdown.Footnote 97

Reception

In the R/18 Collective's roundtable on Messiah/Complex, Mi'kmaw professor of English Robbie Richardson raised the “danger that this can be appropriated into feel-good narratives of Canadian liberal multiculturalism, much like the notion of ‘reconciliation’ for Indigenous people has been rendered almost meaningless in the face of boil water advisories, land disputes, and continued systemic racism.”Footnote 98 Ivany responded that AtG did not intend to put forth Messiah/Complex as “the perfect solution.” They merely hoped that it would be a “step in the right direction.”Footnote 99

Richardson's concerns have not been unfounded. The press has been overwhelmingly positive. “It's hard to imagine a more awe-inspiring lesson on reconciliation and inclusion,” gushed Brad Wheeler in the Globe and Mail's second story on the film. “A masterpiece has been made masterclass to those open to the message.”Footnote 100 The comments on YouTube were predominantly (self-)congratulatory remarks about how diverse and inclusive a place Canada is. During Chaieb's number, for example, Carolyne Thompson remarked in the chat: “I'm so proud to be a Canadian. This project what our country is all about … a celebration of beauty, peace, love and diversity.”Footnote 101

For viewers in other countries, Messiah/Complex confirmed Canada's image as model multicultural nation. For example, Barbara Bloemink remarked in the comments:

I am in my NYC apt sobbing thru the beauty of this Messiah … and saluting CANADA for leading and showing the rest of us what true Diversity and shared Joy and Beauty and Hope look and sound like and unite us across all different races, religions, cultures into what makes us most extraordinarily HUMAN. Thank you Canada and everyone involved in making and sharing this beautiful tribute we so need at this time in human history.Footnote 102

Based on the YouTube comments, Messiah/Complex also tended to affirm for viewers the universality of the Western art music canon. For example, Anne Scott thanked AtG for “bringing together all the pieces of a true Canadian and universal spirituality!”Footnote 103 In one of the few critical comments, Pegi Eyers remarked: “Great for neo-liberals who think this represents ‘diversity,’ but I thought we were supposed to be decolonizing from the assumed Euro-supremacy of classic composers and ‘music theory,’ not celebrating it.”Footnote 104

Robinson observes the tendency for “‘feel-good’ artistic spectacle” to substitute for “social work, environmental change, and political change.”Footnote 105 This is especially true of shows like Messiah/Complex that evoke strong emotional reactions.Footnote 106 Robinson observes that “the intensity of affect when experiencing socially and politically oriented performance allows for a conflation of affect with efficacy. Audiences are persuaded, or more accurately feel, that something has happened; a moment (or more) of something ineffable that might best be called ‘reconciliation’ has been witnessed because our affective response is irreducible, and as such does not lie.”Footnote 107 Robinson argues that we need to move “beyond the position of intergenerational bystanders. It is necessary to acknowledge the privilege and power that we hold within our artistic and working communities, and then find ways to give over such power that move beyond forms of inclusion.”Footnote 108

From Inclusion to Sovereignty

AtG took steps toward giving over some of their power as a settler-run cultural institution in Toronto by hiring an Indigenous co-director and an entire cast of IBPOC soloists. In conversation with Dylan Robinson, Lisa C. Ravensberger, a theater artist of Ojibwe/Swampy Cree and English/Irish descent, notes that

even in classical/traditionally “white” roles, if those characters are inhabited by a brown body, that character's previously one-dimensional worldview has the potential, for possibly the first time, to be enlivened and coloured by a complexity that encompasses more than just an ethno-European experience of power, time, history, land, et cetera. The work is richer for it and, I'd like to think, so are we.Footnote 109

AtG did not merely hire IBPOC soloists to perform Messiah in the same way as they may have done in the past. They invited them to use Handel's music to speak to their lived experience and issues of importance to them. The artistic choices they made—from the language in which they sang to the imagery that accompanied their performances—raised issues not normally raised in performances of Messiah. Diyet, Gilday, Edmunds, and Arreak showed that Indigenous languages are not dead or dying but in fact are making a resurgence. Adams exposed the environmental costs of colonization on their homeland. These are but a few examples of how Indigenous artists enacted sovereignty over their segments of Messiah/Complex.

Regarding the collaborative process as a whole, however, AtG could have gone further in relinquishing power to the IBPOC artists they hired. Arluk and the soloists joined the team after the main parameters of the project had been decided, including the decision to perform Handel's score as written, accompanied by the TSO. Not being part of that decision-making process limited the degree to which the soloists can be considered co-authors of Messiah/Complex as a whole. The philosopher Paisley Livingston argues that being an author involves exercising sufficient control over the artistic planning for the work and the work's final form.Footnote 110 The singers performed that role in their individual segments but were not involved in the work's planning from its initial stages nor were they consulted about the overall shape of the film. Gilday confessed to me that she “had no idea what the production [as a whole] was going to look like at all.”Footnote 111 In this respect, Messiah/Complex bears more resemblance to Robinson's “inclusionary music” than a process that begins by giving IBPOC artists a blank slate with which to work.

Although the musical influences over Soundstreams's Electric Messiah extend beyond Western classical and Indigenous musics, much about both their process and end product bear comparison with Robinson's “Indigenous + art music” category. Adam Scime, music director and composer on the 2020 edition, notes that they invite the musicians involved in each iteration to “bring their own voice to sculpt the project” and that they “give everyone equal collaborative footing.”Footnote 112 As shown in Table 4, the featured performers authored many of the arrangements. In keeping with Robinson's recommendations, Soundstreams made no attempt to smooth over the differences between, for example, SlowPitchSound's turntablism, Métis and French-Canadian composer Ian Cusson's newly composed O Death, O Grave, and Scime's beach-dance-party arrangement of the “Hallelujah” chorus. Soundstreams not only went further than AtG in giving over artistic control to IBPOC artists, but the sonic results questioned the hegemony of the European art music tradition.

Table 4. Soundstreams's Electric Messiah (2020)

Messiah/Complex could have made a more decisive move toward sovereignty if it had begun with conversations with IBPOC artists about what they want to say, artistically and politically, at this moment. The performers should have been able to decide not only what language to perform in but also whether they want to perform Handel's music at all, who they want to collaborate with, and how they want to work together, with AtG recognizing that Indigenous working methods may take more time.Footnote 113 Moreover, singers who decided to take on additional duties as translators, poets, arrangers, or composers should have been appropriately compensated for this labor.

There are many systemic reasons why AtG did not take this approach. First, this is not how most opera companies, even indie companies like AtG, are accustomed to working. Although Peerbaye and Attariwala's report concerns Canadian orchestras, many of their observations apply to the opera world as well. Opera companies are “hierarchical and rigidly structured in terms of creation and production processes and protocols of decision-making.”Footnote 114 They specialize in presenting predominantly European works from the past. They endeavor to present these works in ways that resonate with audiences in their communities. However, because they regard the operatic work as more or less synonymous with the score, the focus tends to be on appearing diverse rather than sounding diverse.Footnote 115

Even when musicians from other traditions are brought in to collaborate with classically trained musicians, there are barriers toward these artists working productively on equal terms. Current training programs for musicians in the Western art music tradition focus almost exclusively on performing the notes on the page rather than on improvising or composing.Footnote 116 They also rarely involve intercultural collaboration. Finally, inviting more artists to the decision-making table and following Indigenous protocols takes more time and money, and most classical music organizations are already in financially precarious positions.

Nevertheless, IBPOC-led companies, such as Amplified Opera in Toronto, are demonstrating that it is possible to work productively in new ways. For example, Marion Newman, Kwagiulth/Stó:lo mezzo soprano and Co-Founder of Amplified Opera, is developing a new opera, Namwayut, with Calgary Opera in which she has free reign as to the subject, her collaborators, and their working methods. Newman decided to work with multiple composers: Ian Cusson and Parmela Attariwala. Even more unusually, she and the other singers are involved in the compositional process; their voices holding authority equal to that of Cusson and Attariwala. At the end of their initial workshop (January–February 2021), the librettist Yvette Nolan remarked: “We can't even tell who made what happen. Everything is so woven together.”Footnote 117 Through Amplified Opera's work as consultants (e.g., Disruptors-in-Residence at the Canadian Opera Company, 2021–22), they are sharing these new collaborative approaches with the big houses. Companies like Amplified Opera and projects like Namwayut point toward a future for opera, and classical music more generally, that is grounded in equity and sovereignty for IBPOC artists.

Messiah/Complex Revisited

In response to calls from audience members and the press for Messiah/Complex to become an annual holiday tradition, AtG brought it back for the 2021 Christmas season.Footnote 118 They made no changes to the film itself but added a 30-minute “pre-show” showcasing The Messiah Project, a community engagement effort by AtG and Opera InReach. They gave two high school choirs in Canada the opportunity for mentorship from industry professionals, culminating in the production of a music video of the “Hallelujah” chorus that would be screened during the pre-show.Footnote 119 As Opera InReach Co-Founder Daevyd Pepper explained in the pre-show, they “weren't looking for a polished, perfect performance. We wanted to see heart. We wanted to see soul. We wanted to see how the choir was engaging with their community.” Accordingly, they encouraged choirs to “submit applications in whatever way they felt most showed their community off, whether that be a video, a letter, a painting, a TikTok, [an Instagram] Reel.”Footnote 120

The choirs they selected were the Agincourt Singers of Agincourt Collegiate Institute in Scarborough, Ontario and the Mennonite Collegiate Institute (MCI) Concert Choir from Gretna, Manitoba. Both choirs performed the same music to the same backing track the TSO recorded for Messiah/Complex. Although each choir produced their own videos, the pre-show only showed a composite video. Images of racially diverse students from Scarborough appearing to make music with Mennonites singing in front of a grain elevator were in keeping with AtG's decision to emphasize unity over difference in Messiah/Complex. Moreover as with Messiah/Complex, these choices tended to blunt the messages individual artists/groups were attempting to convey. For example, Andrew Adridge, Co-Founder of Opera InReach and alumnus of Agincourt Collegiate, directed the Agincourt video to represent changes in choir practice before and after the COVID-19 outbreak. I found this narrative to be much clearer in Agincourt's solo video than when their performance was intercut with that of the MCI choir.Footnote 121

For me, the relaunch was a missed opportunity to critically reflect on Messiah/Complex and take it further. At the very least, I would have liked to see the students’ performances incorporated into the 2021 Messiah/Complex rather than presented as a mere opener to the real event by the professionals. Seeing AtG treat Messiah/Complex as an evolving artist statement would have also been more in keeping with Ivany's hope that Messiah/Complex would be a step in the right direction. Sovereignty for IBPOC artists within classical music is not going to be accomplished with one action. It is something we are going to need to continually work toward.Footnote 122

Nina Penner is a musicologist specializing in opera, musical theater, and film music. Her first book Storytelling in Opera and Musical Theatre (Indiana University Press, 2020) explores how forms of sung drama tell stories in comparison with other media. She also reflects on how centuries-old works remain meaningful to contemporary audiences. Her current work documents the experiences of Indigenous people and people of color in Canadian opera and how projects led by Indigenous people and people of color are exploring new models of authorship and collaboration.