Liszt and opera

Liszt's brief career as an operatic composer is rarely taken seriously today. Despite a battery of operatic transcriptions and a storied variation set on Bellini's ‘Suoni la tromba’ (I puritani), his only completed opera, Don Sanche (1825), is typically classed as an unsuccessful juvenile work of dubious authorship.Footnote 1 All other planned operas of the 1840s and 1850s remained the embryos of ambition, including Richard of Palestine (Walter Scott), Le corsaire (Byron/Dumas), Consuelo (George Sand), Jankó (Karl Beck), Spartacus (Oscar Wolff), Marguerite (Goethe),Footnote 2 Divina commedia (Dante/Autran), Jeanne d'Arc (Friedrich Halm) and Sardanapalo (Byron).Footnote 3 This scattergun approach to great literary topics indicates the breadth of Liszt's ambition, but also underscores the extent to which his desire to conjoin literature and music – the premiss of symphonic poetry – may have first been kindled within the aesthetic potential of opera.Footnote 4

Like Beethoven's aborted opera Macbeth or Mendelssohn's Lorelei, Liszt's endeavours have garnered scholarly interest principally for reasons of curiosity and melancholy. Why were they abandoned? What have we lost? The situation has lent Liszt's foray into Franco-Italian opera a split status: either a curious missed opportunity or a puzzling, apparently false step by an aspiring composer soon to find firmer ground in the progressive agenda of instrumental programme music. This narrative has arguably been in place ever since Franz Brendel's influential Geschichte der Musik (1852) rendered a stultifying verdict on the potentiality of Italian opera:

This nonsense in Italian opera: where we always encounter the same approach to the most diverse situations; where we always have before us the same stereotypical form in individual pieces, this endless cadencing on innumerable fermatas, the accompaniment of each number with trumpet, timpani and janissary music, etc. In a word: this style, this vacuous casualness is mentioned here only in order to justify the verdict that Italian musical art of the present has played itself out, and now finds itself at the lowest ebb of decay.Footnote 5

As with so many historical narratives, this soon ossified into a hermeneutic – in this case one that disenfranchises the operatic. Liszt's sustained flirtation with opera is enmeshed therein and its re-examination in the light of Sardanapalo offers us an opportunity to ‘wrest this tradition anew from the conformism which is on the point of overwhelming it’.Footnote 6

The case of Sardanapalo is unique in that it is the only planned opera for which Liszt wrote any significant music. He devotes 115 pages to it at the start of the music book N4,Footnote 7 and among his Weimar papers there survives an accompanying 36-page French prose scenario in three acts, long thought to be the basis of the opera's libretto but subsequently shown to be a scenario Liszt solicited, but ultimately rejected, from Félicien Mallefille.Footnote 8 To be sure, the music notation of N4 has been known to Liszt scholars for more than a century, but it has been largely ignored on account of its seeming illegibility and incompleteness, and the assumed futility of piecing it all together: few returns for such time-consuming troubles.Footnote 9 (Against this pattern of scholarly neglect, philological sleuthing has occasionally born fruit. Comparable editorial work on other nineteenth-century operas – Verdi's Gustavo III and Stiffelio, Rossini's Il viaggio a Reims, Donizetti's L'ange de Nisida and (at Mahler's hands) Weber's Die drei Pintos – is worth mentioning, if only for its scarcity.Footnote 10)

The first printed comment on Sardanapalo set the tone: in 1911, Ida Marie Lipsius (writing under the pseudonym La Mara) remarked that Liszt's work amounted to little more than ‘a series of sketches’.Footnote 11 In 1954, Humphrey Searle catalogued the opera as S.687 and paraphrased Mallefille's French scenario, but paid scant attention to the music in Liszt's hand, declaring it to be ‘for the most part extremely fragmentary’.Footnote 12 This unpromising verdict has remained largely unquestioned, with the same token fragments appearing in print on a few occasions. Some diplomatic transcriptions were included in Bryan James's dissertation of 2009, but in their uninterpreted, often inaccurate form these make little sense, and James concluded as much, declaring Liszt's music to be ‘riddled with seeming metric inconsistencies and ambiguous harmonic strategies’.Footnote 13 As a result, Liszt's aborted opera has lived a half-life through footnotes, an item of passing curiosity mentioned more out of obligation than interest and assumed to lack artistic coherence. Quite why it has evaded biographical scrutiny – it received mention neither in the first posthumous biographies of Liszt (by Lina Ramann (1894) and by La Mara (1913)) nor in the two most recent (by Alan Walker (1983–96) and by Oliver Hilmes (2011; 2016)) – would seem to be answered simply enough: an aborted or ‘failed’ opera draft runs counter to the romanticizing ideology underlying common conceptions of Liszt's life.Footnote 14 It compromises the image of his creative potency, and its elaboration during 1849–51 would seem to challenge the narrative that by 1849 ‘Liszt's compositional activity hitherto pressed in all its chief characteristics towards [instrumental] programme music’, as Ramann put it.Footnote 15

If we read Liszt's MS N4 consecutively, across the spatial gaps and shorthand, we find that it is not fragmentary at all, but corresponds to what appears to be almost the entirety of the first act of the planned opera Sardanapalo. It is rare to discover that a 50-minute act from a nineteenth-century opera has effectively been hiding in plain sight, yet the evidence points to this being the case. The vocal parts are complete and continuous. They contain most of the libretto text as underlay, and make sense as a narrative whole. The piano score is also de facto continuous, but deceptively so: Liszt uses various forms of shorthand throughout, and revisions and deletions abound; yet, as we shall see, there are no gaps in the musical conception as such. This situation would seem at least partly to corroborate Liszt's optimistic comment, reported by Hans von Bülow in June 1849, that the opera ‘is well on the way to completion’,Footnote 16 and his prediction to Wagner some months later that ‘my Sardanapalo (in Italian) will be completely finished in the course of the summer’.Footnote 17 It suggests that Peter Raabe was correct in his initial assessment of Liszt's Weimar papers for his archival catalogue from 1910–11, namely that N4 contains ‘a large slab of Liszt's opera Sardanapalo!’Footnote 18 More than a century on, it seems that Raabe's startled exclamation mark remains valid.

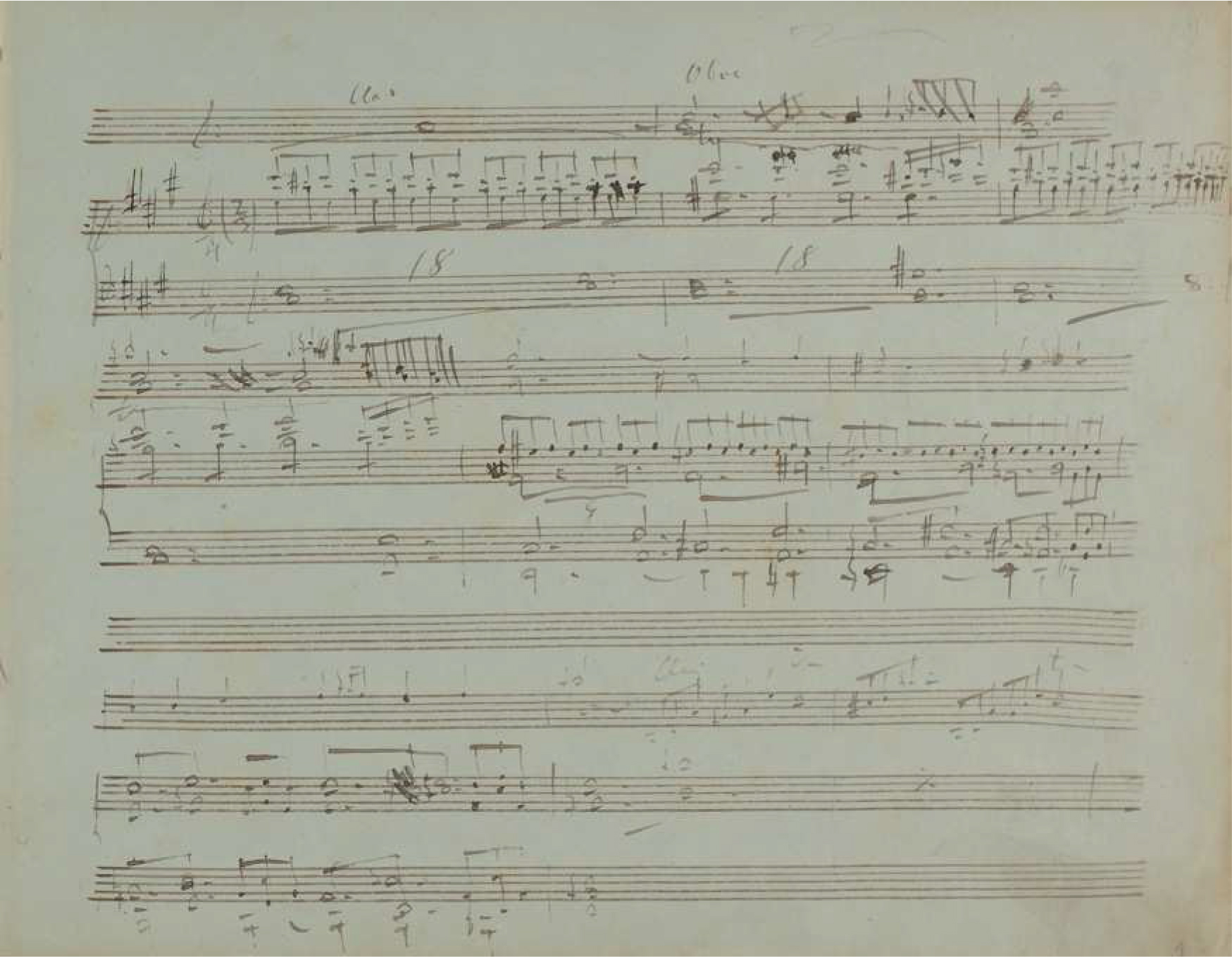

Before proceeding to this article's main focus on the history and aesthetic implication of Liszt's project, it is worth touching on the editorial challenge posed by the apparent gaps. Three exist (bars 705–51, 1082–93 and 1107–61), above which multiple continuous vocal parts are written, however. The most likely explanation is that Liszt wrote down only what he needed to remember. The common element for these passages is formulaic or modular accompaniment that begins clearly, but peters out. Liszt apparently felt that the patterned idiom made it unnecessary to write out the full accompaniment explicitly. Instead, as Figure 1 shows, in the case of bars 705–51 he indicated significant moments of harmonic direction with the necessary bass pitches but left the quaver figuration largely unwritten, as a continuation too obvious to belabour, safe in the knowledge that he would write out a clean copy for later orchestration. Example 1 shows this part of the score as it might be realized editorially. When contemplating such passages, it is worth recalling Liszt's view of how automatically Italian operas appeared to be written at La Scala. ‘One might say it is a manufacturing operation,’ he explains, ‘where everything is known in advance and nothing is required but the actual time needed to put the notes on paper.’Footnote 19 While his complaint concerns what he regarded as a vacuous aesthetic starved of the space needed for inspiration, it contextualizes a trope of criticism concerning Italianate accompanimental patterns. This reading helps to explain his notation through the logic of pragmatism: Liszt wrote out everything except what could be generated as a kind of Fabriksarbeit (Hanslick's term) by any competent assistant.Footnote 20 Indeed, accusations of unoriginal, formulaic accompaniment are not rare during the mid-century. François-Joseph Fétis complained that Verdi's imagination ‘is no richer in the orchestration and rhythm of his accompaniments. There is only one manner, one formula for each thing, and from his first score to the latest [1850], he shows himself everywhere the same, with a desperate obstinacy.’Footnote 21 From a critical perspective, the ‘low’ status of such predictable, patterned textures simply rendered them too straightforward to write out in full. In such a reading, then, there are no gaps in the musical continuity as such; this was not a presentation copy but a private document, and such moments remind us that Liszt was writing in N4 for his eyes only.Footnote 22

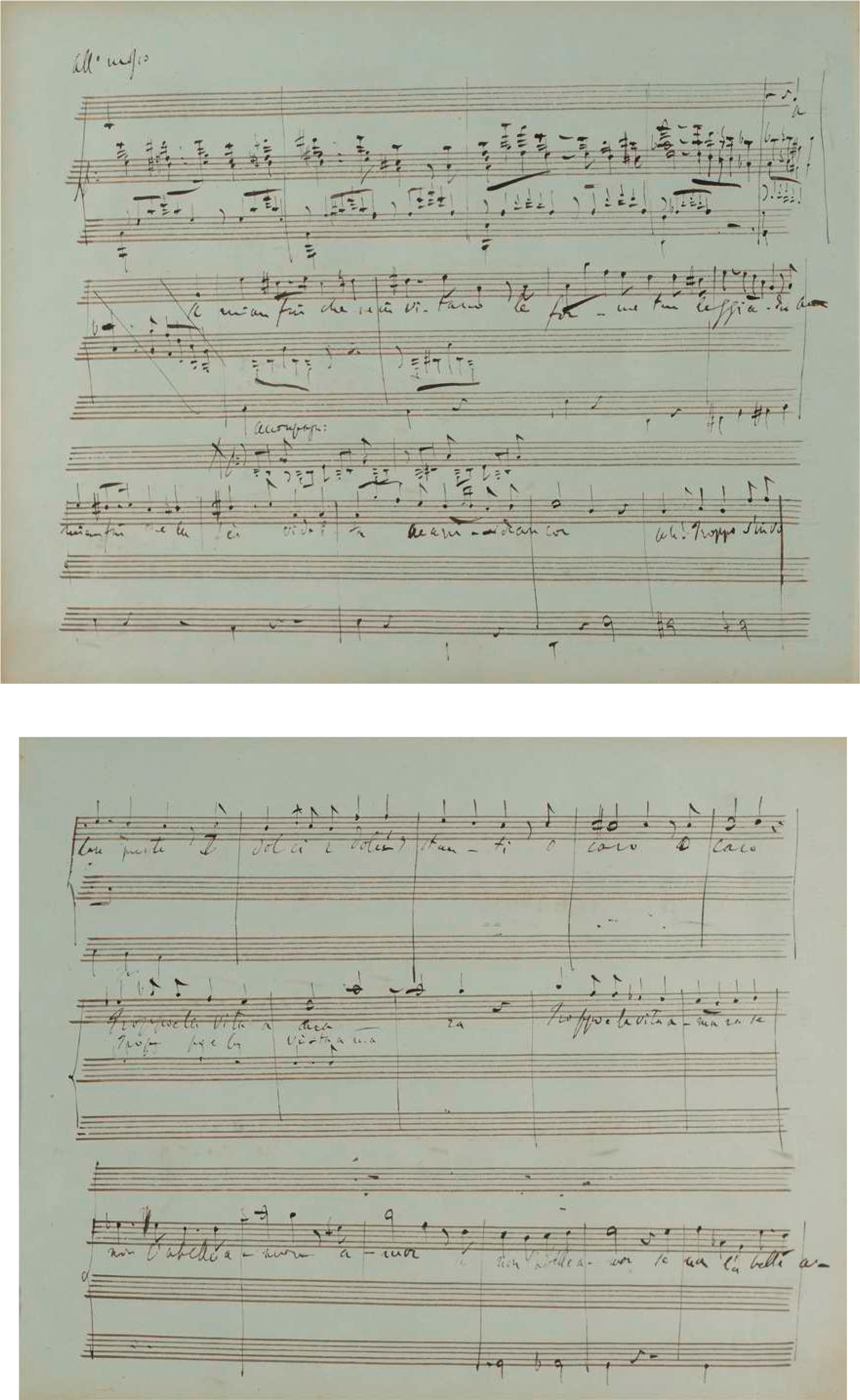

Figure 1. Liszt's autograph MS N4, pp. 70–1, showing the musical ‘gaps’ in his notation of Sardanapalo (GSA 60/N4) for bars 700–29. Foto: Klassik Stiftung Weimar.

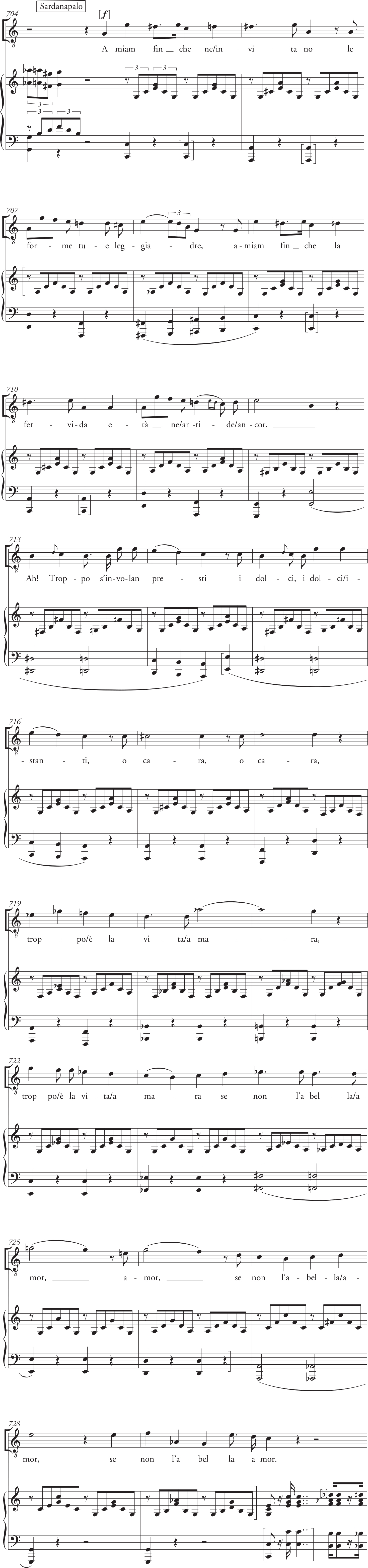

Example 1. Liszt, Sardanapalo, bars 704–30, realizing editorially what is shown in Figure 1. Edition © David Trippett.

In its material layout (see above, note 7), N4 contains 195 pages of music. Liszt entered music into it from both ends. Sardanapalo was first (pp. 1–115), and it seems that when he broke off work on the opera he turned the music book upside down and began writing music not associated with the opera from the other end, perhaps (we may assume, initially) to leave space for the opera's continuation. This evidence – combined with the fact that there are no surviving preliminary sketches and that N4 is written in consistent light-brown ink with at least two discernible stages of revision – suggests that Liszt notated what is given in N4 as a continuous draft which he or one of his young assistants at the time (August Conradi or Joachim Raff) would have orchestrated, for Liszt later to revise.Footnote 23 In fact, Raff understood the situation in precisely these terms, writing in December 1851: ‘I have presently to orchestrate some symphonic works and the opera Sardanapalo by Liszt.’Footnote 24 Such a view accords with Rena Mueller's analysis of Liszt's working practices in Weimar, where seven of the nine Weimar ‘sketch’ books, N2–N7 and N9, might more accurately be termed ‘draft’ books, for ‘although they may contain brief motivic sketches, more often they are devoted to extended workings-out of musical material. […] Preliminary […] sketches simply do not exist for the majority of [Liszt's] works: the pieces were full-blown by the time they reached the writing stage, often after many trial performances.’Footnote 25 While there is no evidence to suggest that Liszt tried out the written music for Sardanapalo with his singers at the Hoftheater in Weimar, it seems clear that a great deal of composition took place in his head and/or at the keyboard before he set pen to paper.

In short, N4 contains a continuous, self-contained extended passage from Sardanapalo, rather than a collection of ‘fragmentary sketches’. This circumstance has a number of implications: first, it allows for the possibility that Act 1 of what would have been Liszt's only mature opera could be realized today in performance.Footnote 26 It also affords us the opportunity to examine Liszt's musical approach to Italian opera during the aesthetic crucible of 1849–51, a period of loud anti-Italian rhetoric in the German press and blisteringly rapid work for Liszt, during which he composed (versions of) his first six symphonic poems, two piano concertos, Totentanz and several four-part choral works, revised the ‘Dante’ Piano Sonata, and conducted a number of new and relatively unfamiliar operas, including both Tannhäuser and Lohengrin, for which he drafted extended essays.Footnote 27 In this context, the music of N4 raises questions about Liszt's aesthetic orientation as a post-Beethovenian symphonist and future pillar of Brendel's neudeutsche Schule, and about his accommodation of, and shifting relation to, Wagner and the aesthetics of what – at the time – was a decidedly self-conscious futurism.

In Part 1 of this article, following the question of Wagner's influence, I consider Liszt's protracted struggles to obtain a libretto for his opera, and present a new, source-rich chronology supporting the stages of work traceable in N4. In the second part, I explore three aesthetic and critical matters arising therefrom: Liszt's avowed focus on declamatory melody for the portrayal of character; his complex engagement with, and attempts to modernize, Italian operatic forms; and the historiographic implications arising from his setting of an operatic libretto, in contrast to an instrumental programme. Given the Byronic libretto to Sardanapalo and Liszt's contemporary veneration of what he called ‘musical drama’ (musikalisches Drama), all this raises the question of whether the opera's ‘unfinishedness’ may mark a moment of unanticipated frailty in his veneration of literature.

Part 1

The Wagner factor

We might start at the end: with Wagner. After conducting Tannhäuser on the occasion of the Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna's birthday on 16 February 1849, Liszt first entertained the idea of a mutually supportive friendship with Wagner, writing: ‘Once and for all, number me in future among your most zealous and devoted admirers; near or far, count on me and make use of me.’Footnote 28 Wagner did not hesitate, of course, and history records an asymmetrical relationship. For at least a few months, however, it appeared to be more reciprocal, even symbiotic, in the sharing of aspirations; Wagner's support and encouragement of Liszt's compositional ambition during this time is a matter of record.Footnote 29 Less appreciated, perhaps, is the extent to which it was interwoven with his music for Sardanapalo.

In his analysis of the reasons for Liszt's abandonment of the opera, Kenneth Hamilton posited Wagner's role as decisive:Footnote 30 ‘The spectre of Wagner's pioneering dramas would hover balefully over anything [Liszt] did in Germany,’ he argues:

However difficult Liszt found it to comprehend the convolutions of [Oper und Drama, 1851], it must have become quickly clear to him just how little an antiquated Italian offering like Sardanapale would fit in with Wagner's notions of the artwork of the future. Liszt, usually only too keen to be at the cutting edge of the avant-garde, suddenly found himself to be yesterday's man. […] Opera on the stage would be left to Wagner.Footnote 31

In such a view, Liszt recognizes the force of Wagner's aesthetic direction in opera and steps aside for the greater artist, rechannelling his creative energies into symphonic poetry, like electricity discharging itself along a more accommodating conductor. In this reading, his explicit statement ‘I must abide by my resolution never to write a German opera’ (1851) becomes less a tactful sidestepping of Wagner's suggestion that he set Wagner's cast-off libretto for Wieland der Schmied and more ‘a strong reluctance to compete directly on Wagner's turf’.Footnote 32 This is undoubtedly plausible (as is James's suggestion that, when faced with Wagner's knotty alliterative prose, Liszt viewed a familiar Italian genre as the easier option).Footnote 33 However, with the music now at hand and the greater overview afforded by newly available correspondence, it is possible to draw slightly different conclusions. In short, while Wagner's role is undoubtedly present, it now appears less influential in Liszt's decision to abandon his opera.Footnote 34

‘Creative power in music’, Wagner tells Liszt encouragingly in 1849, ‘appears to me like a bell, which the larger it is, the less able to give forth its full tone, unless an adequate power has set it in motion. This power is internal.’Footnote 35 The letter arrived six months after Liszt's first attempt to draft the music for his long-planned opera. With gently goading metonymy it goes on to allude to Liszt's Goethe-Festalbum (1849), comprising discrete incidental and choral works related to Faust, three years after Liszt had first aspired to compose an opera entitled Marguerite:Footnote 36

As I have every reason to deem your [power] great, I desire for it the corresponding great incitement; […] if you had been able to ring the whole Faust bell (I know this was impossible!), if the detached pieces had had reference to a great whole, then that great whole would have thrown on the single pieces a reflex which is exactly the certain something that may be gained from the great whole, but not from a single piece. In single, aphoristic things we never attain repose […] Unrest in what I do is proof to me that my activity is not perfectly self-contained […] This unrest I have found in your compositions, even as you must have found it only too often and with equally good reason in mine! […] I compare it to the claw by which I recognize the lion; but now I call out to you, show us the complete lion: in other words, write or finish soon an opera!Footnote 37

Coming from a new confidant whose Tannhäuser had fired Liszt's imagination in two piano transcriptions and an extended, propagandistic essay, this message tapped unwittingly into Liszt's long-standing ambition. Liszt was happy to divulge his plans. Two weeks later, he duly replied that Sardanapalo would soon be completely finished (see above, note 17) – a sentiment reiterated to various interlocutors.Footnote 38 Two years later, however, the opera remained incomplete and Wagner raised the topic again, this time firmly suggesting that Liszt change direction:

Write a [German] opera for Weimar, I entreat you; write it exactly for the artists who are there. […] Continue, if you like, your plans for the Italians […] [but] frankly speaking, what do you seek just now, and with your present activity among the Italians, other than – an increase of your fame? Fine! But will that make you happy? You – no longer! You can only become happy under entirely different conditions! Do something for your Weimar!Footnote 39

Why the about-turn? During the winter of 1850–1, Wagner famously penned his most sustained diatribe against Italian opera in Part 1 of Oper und Drama. Had Sardanapalo come to fruition it would have sat awkwardly with Wagner's claim that Italian opera had died with Rossini (its ‘murderer’), that Italianate melody was a ‘plastic’ crime in music and that the whim of its overpaid singers rendered claims for a seriousness of dramatic purpose impossible. Wagner's subsequent words to Liszt, quoted above, suggest a direct correlation, as Hamilton argued.

But Liszt had no means of reading the anti-Italian rhetoric of Part 1 of Oper und Drama before (at the earliest) the end of November 1851, when the book was finally published by J. J. Weber, and his opera project continued thereafter.Footnote 40 The three serialized excerpts to which he did have access in March and May – those that Wagner published in the Deutsche Monatsschrift – came from Part 2 (on poetry/drama), not Part 1 (on music/opera).Footnote 41 Wagner chose not to send him a personal copy of the full book, preferring instead to imply (misleadingly) on 14 December 1851 that it had ‘long been published, as you probably know’.Footnote 42 Instead he prompts Liszt to buy a copy of Eine Mittheilung an meine Freunde, whose preface summarizes some of the central claims in Oper und Drama, but – significantly for present purposes – closes with an encomium to Liszt as his principal supporter and, in artistic matters, his ‘second self’: ‘ I wager the preface will interest you very much.’Footnote 43 If there were a malign intent in Wagner's actions here (vis-à-vis his knowledge of Liszt's aspiration for Sardanapalo), it would seem to be only to shackle Liszt to Wagner's views in Eine Mittheilung by publicly declaring Liszt's allegiance. The flip side is that Wagner apparently took pains not to share the rawest anti-Italian sentiments from Oper und Drama.

It is likely that Liszt read Part 1 eventually, of course. Assuming that he did so, his verdict was sure but delayed: it emerges in published comments on Meyerbeer and Rossini in the 12 essays he published in 1854, which place him starkly at odds with Wagner's judgments. Rossini ‘bestowed literary value’ on the literary texts used in his operas, ‘many of which had never been given attention before. Like a son of the gods who plays with the stars, he played with art.’Footnote 44 When confronted with a mind such as Shakespeare, Rossini

adopted the poet's psychological observations and pathological studies in Othello's character anima nobili, he also captured all of the elegiac melancholy, sorrow and innocence that were portrayed in the destiny of Shakespeare's character Desdemona […] Where the dramatic author revived Shakespeare's characters there was nothing in Rossini's opera that pertained to the same formlessness, dramatic pretensions, or unrestrained action of the Italian school.Footnote 45

It is telling that slapping down Wagner's views was not incompatible with Liszt's own criticism of Italian opera (see below). In complementary fashion, Meyerbeer – ‘for almost 50 years […] the leader of the gradual development of opera in France and Germany’Footnote 46 – effected ‘new requirements for opera texts’ where dramatic situations come to the fore, motivating a merger of so-called ‘declamatory and melodic styles’.Footnote 47 Differences of temperament notwithstanding, Liszt's independence from Wagner's character assassinations is palpable here, a fact that reflects his secure status in firmly disagreeing with his younger colleague.Footnote 48

Perhaps this should come as little surprise. Wagner himself wrote privately at the time of ‘a friend […] quite distant from me in many important aspects of life. […] In my mind he doesn't understand me, my conduct is perfectly distasteful to him.’Footnote 49 And Liszt quietly dismisses Wagner's plea for a new originality of purpose in theatres (in Ein Theater in Zürich) as an amusing diversion ‘that has little to teach us’.Footnote 50 After Brendel first aligned Liszt and Wagner in the final chapters of his Geschichte, their popular conflation would be mercilessly caricatured by Nietzsche as ‘the emergence of the actor in music: […] In a formula: Wagner and Liszt’.Footnote 51 In such a view, Liszt – shorn of individuality – becomes a second in command, a sideshow, a kind of historical sidekick to Wagner's aesthetic leadership.Footnote 52 The hierarchy within this perspective sees the idealist project of symphonic poetry emerge only after Wagner decreed Beethoven's Ninth Symphony a historic pivot to future art, a threshold beyond which no purely symphonic composition is possible. This contradiction accounts for the diplomatic tiptoeing in Wagner's open letter on the symphonic poems (1857), where, after indicating that mental representations of Orpheus or Prometheus could replace the march or dance as arbiters of ‘form’ (on which music's ability to communicate depends), he nevertheless unveils a certain scepticism: that one may ‘point to the difficulty of extracting an intelligible form for musical composition out of such exalted representations’ and that ‘while listening to the best of [instrumental programme music], even works of genius, it always happened that I would lose the musical thread so completely that no amount of exertion allowed me to hang on to it or take it up again’.Footnote 53 If we unshackle ourselves from Nietzsche's caricature, the historiographic implications of Liszt's compositional work on Sardanapalo and his later essays on opera suggest a number of such underlying differences of opinion.

In 1988, Detlef Altenburg summarized Liszt's independence cogently in this respect:

Liszt opposes the lineage from Beethoven's Ninth Symphony to music drama, developed by Wagner in Oper und Drama, with a derivation from the tradition of opera and of theatre music. With the express inclusion of grand opera, Liszt repeats the thesis that had induced Wagner in Oper und Drama to formulate a counter theory. The fact that Liszt is concerned not only with the importance of Beethoven's Fidelio, but also with the music of Egmont, reveals how Liszt's perspective deviates from Wagner's: the symphonic style has its roots in Beethoven's various altercations with the problem of combining drama and music, and not in his symphonies.Footnote 54

The implications of this discrepancy arguably have wider ramifications than Altenburg first intimated. It explains why Liszt's essays on opera consistently emphasize drama, literature and symphonic narrative: Fidelio constitutes a ‘uniquely dramatic work’ and Egmont ‘a new path for art’ wherein ‘the great composer felt immediate enthusiasm for this great poet's work’;Footnote 55 Weber's Euryanthe becomes a ‘wonderful divination of the future form of drama’;Footnote 56 and the composer of Der fliegende Holländer constitutes ‘the founder of German opera, or of musical drama’.Footnote 57 This subtly alternative genealogy reveals how the differences with Wagner extend beyond valuations of Rossini and Meyerbeer to the very manner in which drama and literature could serve as the axis on which modern opera was to pivot. Such stark differences remind us that, despite his effusive appreciation of Tannhäuser and Lohengrin, Liszt was independently minded enough to avoid taking Wagner's comments too seriously at the time. For all these reasons, then, Wagner's words – private and public – are unlikely to have been a decisive factor in his decision to stop work on Sardanapalo.

Towards Sardanapalo

That decision nevertheless closed the door on an ambition that dated back to October 1841, when Liszt first harboured ideas of composing a French opera after Byron, initially Le corsaire then Manfred,Footnote 58 and a setting of Dante's Divina commedia. At the time, Liszt's interest in pursuing these operatic subjects was bound explicitly to his desire to attain status as a European composer, as opposed to that of a keyboard virtuoso. Over and above the pain of Schumann's stinging verdict in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (that a bald disparity (Mißverhältnis) was noticeable between Liszt's developed piano playing and his far less developed compositional aptitude),Footnote 59 Liszt eyed Rossini's success and supra-musical stature in central Europe with a certain envy, comparing his progress in advancing art with Napoleon's in advancing society.Footnote 60 In his eyes, it seems, the spectacle, size, expense and public appeal of Franco-Italian opera ensured that this was the privileged route to such power, to realizing his own avowed ‘social mission’ through art, and to enter ‘the musical guild’, as he later put it.Footnote 61 Accordingly, at the apex of his so-called Glanzzeit, Liszt tells his close friend the refugee noblewoman and salonnière Cristina Belgiojoso of his secret desire to dovetail careers; he will abandon his identity as a touring virtuoso ‘within three years’, he declares. ‘I'll end my career in Vienna and in Pest, where I began it. But before then, during the winter of 1843, I want to première an opera in Venice (Le corsaire after Lord Byron).’Footnote 62 It did not remain secret for long. Marie d'Agoult reports the same sentiment a year later,Footnote 63 and Liszt would variously restate this retirement plan – ‘to cross my dramatic Rubicon’ – in January 1843 and March 1845.Footnote 64 In fact, both matters were delayed: it would take him until September 1847 to retire as a professional virtuoso, and problems with the initial libretto for Le corsaire led him to Alexandre Dumas; in February 1844 Liszt tells d'Agoult that Dumas's libretto is ‘amusing’ (drôle), but it vanishes from his correspondence thereafter.Footnote 65 Of the other planned subjects, Manfred and the Divina commedia, Liszt's compositional work on the former indicated that there would be a steep learning curve: ‘I began composing [the chorus for] Manfred ’, he states in 1844, conceding that ‘it is much harder than I thought because there is a certain monotony, and it's difficult to change that’.Footnote 66 (His dissatisfaction with a libretto – in this case by O. L. B. Wolff – would prove prognostic, as we shall see.) As late as January 1850, Raff 's unvarnished words confirm the point: ‘His intention is to spend 2–3 years preparing in every style for a career as a composer, and thereafter to appear on the scene in Paris.’Footnote 67

Late in 1845, again in tandem with Belgiojoso, Liszt conceived of, and settled upon, an opera based on (Lord Byron's) tale of Sardanapalus,Footnote 68 the last Assyrian king, whose historic downfall followed his aversion to bloodshed, his indulgence with women and in revelry, and his unwillingness to employ brute force in governing his subjects.Footnote 69 The choice of subject is perhaps unsurprising, its imagery and narrative thick in the air as Liszt came of age: Byron gave it exponential currency when he published a five-act tragedy, Sardanapalus (1821), twinning the weakness of Sardanapalus's non-violent rule with his reckless love of the Ionian slave-girl Mirra. Written in blank verse and dedicated to Goethe, it united two titans of literary Romanticism for Liszt, who acquired the first French translation in 1827. While he comments little on Byron's actual verse, Liszt's copy of Byron's Oeuvres complètes contains underlinings and marginalia, including one pencil bracket in Act 4 of the Englishman's play.Footnote 70 At this point in the narrative, the King is dazzled by the spectacle of his own tragedy: he seeks to justify to his wife his pursuit of a peaceable regime rather than that of a brutal conqueror, rueing the lack of respect it has inspired among his subjects.

Even as Liszt's pencil stroke pinpoints the crux of the King's tragedy – a self-delusion that all are innately good – it reveals little of his hermeneutics as a reader, confirming only that, as with Le corsaire, he read the play, pencil in hand.Footnote 72 Elsewhere, as is well known, Liszt quoted from Childe Harold's Pilgrimage in two epigraphs within his Album d'un voyageur (1837–8), planned several other operas after Byron and visited Byron's house in Venice during 1839, expressing delight at a chance encounter with a gondolier who had transported Byron himself around the waterways 15 years earlier.Footnote 73 A year later, after paying a similar visit to Newstead Abbey, Byron's ancestral home, Liszt declared an idealist affinity: ‘After you [d'Agoult] […] it is to him alone that I feel deeply attracted. I know not what burning, whimsical desire comes over me from time to time to meet him in a world in which we shall at last be strong and free.’Footnote 74 It would endure: ‘Byronism eats away at me,’ he confessed again in 1844.Footnote 75

Also inspired by Byron's tragedy, Eugène Delacroix's substantial oil La mort de Sardanapale (1827–8) was displayed at the Paris Salon in 1828. A controversial work, it was criticized both for its subject – ‘the name [of Sardanapalus] has become synonymous with all that is most ridiculous and vile about debauchery and cowardice’ – and for its non-neoclassical, starkly coloured form. It was likened to a ‘Persian carpet’ and a ‘kaleidoscope’ by some, and the Journal des débats dubbed it simply ‘an error of the painter’.Footnote 76 As Figure 2 shows, Delacroix's painting depicts the actions of the Eastern monarch upon learning that his kingdom has been sacked: he witnesses the destruction of all that is dear to him – a bonfire of the vanities – including his concubines, slaves, pets and stud of horses; all in preparation for his famed, opiate-fuelled self-immolation, or, as Byron puts it, ‘a leap through flame into the future’ whose excruciating pain would serve as a historic act of defiance:

Figure 2. Eugène Delacroix, La mort de Sardanapale (1827–8). Musée du Louvre / Wikimedia Commons.

Liszt knew the lines and the painting, calling Delacroix ‘the Rubens of the school of Romanticism’ and telling Belgiojoso that his operatic finale will ‘even aim to set the audience alight!’Footnote 78 While Stendhal felt that Delacroix had captured the spirit of Byron's ‘satanism’ and Victor Hugo found the work ‘magnificent’, rueing only the absent ‘basket of flames’ underneath, the complexity of the composition bewildered the writer Auguste Jal: ‘[Delacroix] wanted to compose disorder, and he forgot that disorder itself has a logic.’Footnote 79 Its reception, in short, became a topic au courant within Paris's intellectual debate between classiques and romantiques.

Still closer to Liszt's circle, Berlioz's cantata La dernière nuit de Sardanapale (1830, setting a text by Jean François Gail) famously received the Prix de Rome. Berlioz destroyed most of the music (for tenor and male chorus), but Liszt attended its second performance in Paris.Footnote 80 Alongside several versions of the play for spoken theatre (including some with incidental music)Footnote 81 and Giovanni Galzerani's azione mimica from the 1830s (which Liszt could conceivably have encountered in Milan),Footnote 82 the tale would prove popular for operatic treatment, receiving at least six settings during the nineteenth century (see Table 1). Even Verdi considered a request to set a version of the story in 1843, but refused on the grounds that the libretto was too similar to Nabucco.Footnote 83 Liszt knew Pietro Rotondi's libretto for the 1844 opera, having studied a marked-up copy from Belgiojoso (‘of which I take great care’),Footnote 84 but there is no evidence that he took an interest in, or was aware of, subsequent settings.

TABLE 1 operatic settings of the tale of sardanapalus during the nineteenth century

| Composer | Librettist | Title | Date of première | Place of première |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giulio Litta | Pietro Rotondi | Sardanapalo | 2 Sept. 1844 | Teatro Filodrammatici, Milan |

| Giulio Alary | Emil Pacini | Sardanapale | 16 Feb. 1852 | Imperial Theatre, St Petersburg |

| Victorin Joncières | Henry Becque | Sardanapale | 8 Feb. 1867 | Théâtre Lyrique, Paris |

| Guiseppe Libani | Carlo d'Ormeville | Sardanapalo | 29 Apr. 1880 | Teatro Lirico, Rome |

| Tommaso Benvenuti | Francesca Maria Piave | Sardanapalo Footnote a | unknown | unknown |

| Alphonse Duvernoy | Pierre Berton | Sardanapale | Dec. 1882 | Lamoureux Concerts, Paris |

Note: The existence of further settings – by Julius Sulzer, Otto Bach, Moritz Strakosch, Baronnede Maistre and F. C. A. Durette – is postulated in Franz Stieger, Opernlexikon: Titelkatalog, 3 vols. (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1975), iii, 1084, where, however, no further details are provided. The earliest known operatic settings of the tale are Giovanni Freschi's Sardanapalo (Venice, 1679) and Christian Boxberg's Sardanapal (Ansbach, 1698). Some details of Boxberg's setting are available in Hans Marsmann, Christian Ludwig Boxberg und seine Oper ‘Sardanapalus’ (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1916).

a Piave's autograph libretto and Benvenuti's autograph score, along with a revised score for an ‘orgy finale to Act 2’, are housed at the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice, as VE0049 BENVENUTI 11796-97-98 and VE0049 BENVENUTI 11706. There are no details pertaining to performance.

From a different perspective, colonial plunder also stirred interest in the subject of ancient Assyria. Five years after Liszt set aside his work on the opera, the eminent French critic Augustin Thierry wrote to Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein expressing regret that Liszt ‘has not yet given us his opera Sardanapalo, whose libretto – I have learned [from Belgiojoso] – is excellent’. He elaborates:

The ancient discoveries made at Nimrod and at Kersabad make this subject truly of the moment. The museums of Paris and London contain inspiration for a great musician who would today depict the Assyrian life in these palaces, the doors of which were guarded by elderly bulls with a human face.Footnote 85

Thierry was speaking of the shedu or lamassu, a huge winged bull that guarded gateways (see Figure 3). Suffice it to say that the imagery and anti-heroic narrative of Sardanapalus permeated an array of artistic media during the nineteenth century. From October 1845 Liszt harboured fervent ambitions to enter this cultural arena. As the following chronology demonstrates, he would work on and off for seven years to do so.

Figure 3. Assyrian shedu or lamassu, winged bulls who guard gateways, relocated from northern Iraq to museums in London and Paris during the 1850s. Photo © Musée du Louvre, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Thierry Ollivier.

A reconstructed chronology

On the basis of newly available correspondence (published and unpublished), and building on Hamilton's pioneering work in establishing an initial version of the chronology, it now seems most likely that events unfolded as follows. Liszt had decided to collaborate with Belgiojoso on an opera based on Byron's Sardanapalus shortly before his letter of 16 December 1845. He initially planned to procure the scenario from the novelist and playwright Félicien Mallefille for Belgiojoso to oversee, perhaps to translate and versify. ‘Soon I will bring you the scenario of the three acts of Sardanapalo,’ he promised her in December 1845. ‘We will have plenty of time to talk, and barring unforeseen circumstances I may be very tempted to première it during the carnival season of 1846–7 in Milan.’Footnote 86 And in January 1846: ‘I warmly thank you for agreeing to take care of Sardanapalo. […] What you say about [it] is profoundly intelligent; I hope we can achieve a very good première for the opera. I'll send you a Sardanapalique scenario by mid-February at the latest, on which I pray for your observations. Versification comes next.’Footnote 87 This suggests that Mallefille's deadline was February 1846. By April, Liszt had received nothing, and wrote to Belgiojoso with reassurance:

I am told of the imminent arrival of Sardanapalo, which I shall have the honour of sending to you at once. Within the next six weeks I shall probably also know something definite about the date it is to be staged and the principal singers. Barring unforeseen and adverse events, I think people in Vienna will have a chance to boo me in May ’47.Footnote 88

Frustrated with the delay, Liszt was burning to proceed: ‘I am behind with my paperwork and absolutely itching to compose,’ he confides to d'Agoult. ‘There remains the theatre, it is true, e vedremo il nostro Sardanapalo [and we will see our Sardanapalo]!’Footnote 89 A month later, he writes again to Belgiojoso (who had yet to receive the promised scenario) to reassure her a second time and confirm his ambitions for a Vienna première ‘next season’ (1847).Footnote 90 He tells others of the planned première,Footnote 91 while assuring d'Agoult of his confidence at becoming ‘a unanimously nominated candidate for [Donizetti's soon-to-be-vacant] position’ as Kapellmeister at the Kärntnertortheater in Vienna, a prestigious post to which he was only initially attracted, but one that d'Agoult had urged him to ‘make every effort to obtain’.Footnote 92

During the summer of 1846, with no sign of Mallefille's scenario, Liszt's patience snapped. A vitriolic letter screams that Gaetano Belloni, his secretary, had been received ‘like a dog in a skittle-alley’ when he broke the news that ‘I had to put my hopes for Sardanapalo on hold until the end of September [1846]’. This was the second time Mallefille had missed a deadline (‘At all costs, I am determined he will not make a fool of me a third time’), and Liszt was resolute: ‘To be frank, it is quite impossible for me to hang around kicking my heels any longer!’Footnote 93 Fearing for the planned Vienna première, he evidently decided to explore Belgiojoso's (undocumented) suggestion that she procure a scenario from a second poet whom she never names. This poet's work was to be rapid: before 5 August, Liszt sent Belloni again to Paris ‘with orders to bring me back, dead or alive, a Poem (which would be suitable for me) in his pocket. […] All my travel plans are thus subordinated to the quarter of an hour which will bring this result that matters to me above all.’Footnote 94 The work was completed with alacrity. On 25 September Liszt thanked Belgiojoso for a scenario ‘so excellent that I doubt greatly that there could be an Italian poet capable of composing such a good one, and that I suspect your Highness, in particular, has been busy working on it. Another reason that I am doubly grateful to you.’Footnote 95 The new arrangement – in which a poet creates and Belgiojoso edits and corrects – meant that Liszt was heavily reliant on Belgiojoso, and trusted her literary acumen, content in the knowledge that an Italian libretto would emerge under her authority:

Permit me simply to place my entire musical destiny in your beautiful hands, and allow me to implore you to consent to hasten and oversee with all your intelligent care the definitive preparation of this libretto of Sardanapalo which seems to me, aside from its other merits, admirably cut out for musical developments. If it were possible to send the finished libretto to me in Vienna towards the end of November (and I hope you will deign to follow through on your kind offer to review and make necessary corrections to the versification, which should be vigorously energetic), you would make me very happy!Footnote 96

Towards the end of the year, Liszt evidently sent Belloni on a third trip to chivvy matters along and extract the versified libretto. A full libretto was not forthcoming, but on New Year's Day 1847 Liszt confirmed to a publisher: ‘Belloni pulled it off ! / The first act of my opera has arrived – I will attend to it quickly, but after all these unexpected delays there can be no talk of it before the coming spring.’Footnote 97 This versified text was completed mere weeks after the three-act scenario; as we shall see, it is almost certainly the only versified text Liszt received that was to his satisfaction, and hence that he set in N4.

In the meantime, Liszt had written – new scenario in hand – to tell Mallefille the partnership was off, and complained wryly to a confidant about his procrastination:

Mallefille is a great genius and a great man. I do not deny it. But he is putting me in the most terribly unfortunate position and whatever my feelings on the matter, I must finally make a decisive stand and renounce the idea of associating my humble name with his resounding […] and late glory. […] It is evident that our Shakespeare will not or cannot come up with a suitable scenario for Sardanapalo. Well fine! Others will manage it better and certainly quicker than him. […] To the devil, then, with Mallefille's Sardanapalo. May the thousand francs that I gave him on account rest lightly on his republican Puritanism and may the gods preserve me henceforth from all rotten collaborators.Footnote 98

Liszt's ironic inversion (‘our Shakespeare’) indicates the hope that had been thwarted, and the frustration that cut correspondingly deep; he confirmed it to d'Agoult (‘You were right to protect me from the great man of the rue Tabazan’)Footnote 99 and to Belgiojoso herself (‘At the same time as these lines, I am writing to Mallefille sending him swiftly to the devil, which I am perfectly entitled to do given his behaviour towards me’).Footnote 100 As an unpublished Konzeptbuch containing draft copies of Liszt's letters shows, Liszt had written on 21 May 1846 to his friend the drama critic Jules Janin to articulate his frustration at what transpired, quoting from correspondence with Mallefille that is no longer extant.Footnote 101 The letter reveals further details, and its relevant paragraphs are given in the Appendix (see p. 431).Footnote 102 In short, Liszt had paid 1,000 francs in advance to the Frenchman in order to receive the French scenario by the end of February (1846), ‘so that I could take it with me to Vienna and make it rhyme in Italian’.Footnote 103 On receiving Liszt's letter cancelling their collaboration, Mallefille requested a further 2,000 francs in advance for the full ‘drama in three acts’, which he promised to send by the end of the month. Liszt resented his ‘republican’ behaviour, adding: ‘In truth I could hardly have imagined that I would be treated like such a cashcow! […] it is simply a scenario (and not a completed work) that I must then have translated into Italian and checked and reshaped in accordance with the exigencies of the Italian stage.’Footnote 104 From the correspondence quoted in Liszt's letter draft, it appears that Mallefille protested that there had been a ‘misunderstanding’ about the timetable, and claimed he had felt obliged to take on other work. He did finally send the scenario on 9 December (GSA 59/156), and while Liszt's response does not survive, the draft records his intention to decline Mallefille's offer and send him ‘two-thirds of the amount which he asks of me’ to end the matter: ‘Amen! Fraternity in death!’Footnote 105

On 3 January 1847 – with Act 1 of the libretto in hand – Liszt grumbled to d'Agoult that ‘almost nothing has been done’ on the opera.Footnote 106 As the planned première in May 1847 looked increasingly unrealistic, he tacitly abandoned it, later signalling his intention to ‘complete my 3 acts’ upon returning to Weimar in mid-July,Footnote 107 but in July confirmed that ‘it has been more than 8 months since I have written to Princess Belgiojoso’.Footnote 108 In other words, he still lacked a full versified libretto at this time. At some point over the ensuing months he evidently resigned himself to the need for a third poet; Belgiojoso's poet was languishing in prison and appeared to have declared the task beyond him.Footnote 109 Writing to Belloni in February 1848, he anticipates making final arrangements for the première of Sardanapalo with Gustav VaëzFootnote 110 and Giovanni TadoliniFootnote 111 ‘by the end of April or May at the latest’. It seems that Tadolini had offered to help procure assistance with the libretto in Belgiojoso's absence: ‘At the same time we shall finish off the Sardanapale in Italian,’ Liszt explains, ‘for which I gratefully accept the good services that M. Tadolini has kindly offered me – I hope that by next September I shall be in possession of the two libretti [Sardanapalo and Richard of Palestine], and then shall set to work immediately.’Footnote 112 It seems that Liszt wrote to Belgiojoso explaining his intention to collaborate with a third poet, to be procured by Tadolini, after receiving negative news about her poet. On 12 May 1848, the princess replies:

This saddens me because I have in my drawer the most beautiful Sardanapalo in the world, the fruit of toil and slavery of that same poet whom I'd first addressed myself and who at my request had sent you a ‘scenario’! I mentioned before that prison had clipped the wings of my nightingale, who could neither accept nor fulfil any literary commission in the situation he found himself. The person who told me of this has misunderstood and explained himself even less well. My poet was modest and nothing more. ‘I fear not being successful,’ he said; ‘how can I engage in a work of imagination under these locks’, etc. etc.; and the interpreter translated: ‘Tell the princess that I cannot work.’ In short, he got out, with the finished manuscript in his pocket and with much satisfaction in his heart because I told him his manuscript would earn him 2,000 francs, and this sum was dancing before his eyes. […] If it is possible, send the 2,000 francs very soon, for the place where my poor friend just spent a whole year is not Peru, and he came out a lot poorer than he went in; this was not, however, very easy.Footnote 113

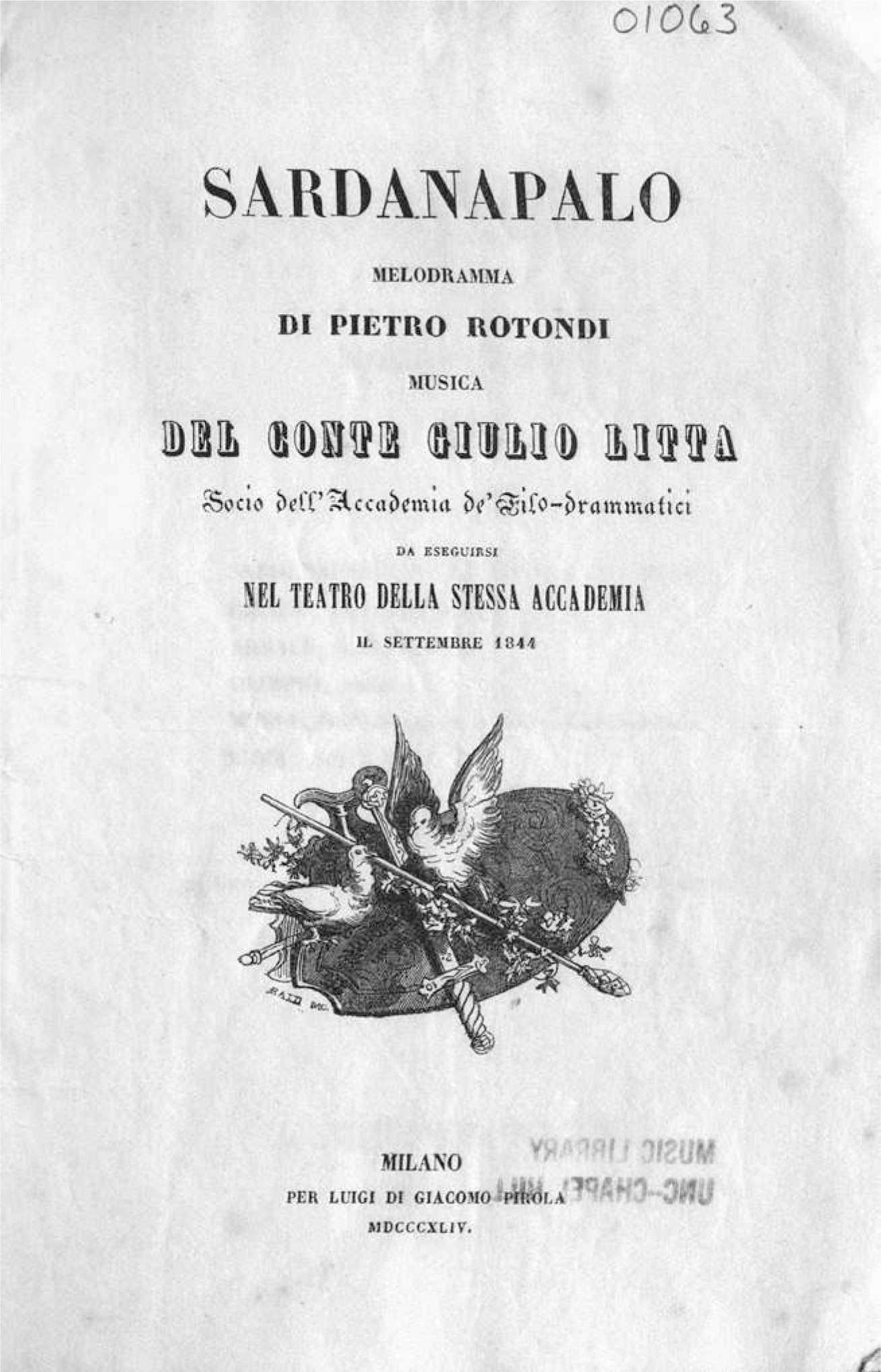

Liszt's undated reply (c.June–July 1848) speaks of rekindling ‘a desire, an idea whose postponement I had been resigned to, but which I had scarcely abandoned. Your Sardanapalo comes to me in just as timely a manner as will the two thousand francs for the poet.’Footnote 114 It goes on to duplicate elements of Liszt's message from 6 October 1846, reminding the princess of her responsibility to edit the versified libretto and adding: ‘The notes and commentaries which you added in the margin of Rotondi's libretto (of which I take great care), are witness to such mastery in this genre that there is no wiser course than to have full confidence in your judgment.’Footnote 115 The mention of Rotondi here led Felix Raabe, Searle, Szelènyi-Farago, Kaczmarczyk and others to assume that ‘Rotondi’ was the missing librettist all along.Footnote 116 As Hamilton pointed out, however, the syntax of Liszt's letter suggests that Rotondi's libretto and that expected for Liszt's opera were different.Footnote 117 Indeed they are. Pietro Rotondi was the librettist for an Italian opera on the same topic composed by Giulio Litta in 1844, as noted in Table 1 above. Furthermore, his text has few if any points of close correlation with the libretto that Liszt set. (The title page of Rotondi's libretto is given as Figure 4.)

Figure 4. The title page of Pietro Rotondi's libretto, Sardanapalo (1844). From the Italian Opera Libretto Collection, Music Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. With permission.

After seemingly waiting for Godot, matters moved forward considerably in August 1848. Liszt confirms to d'Agoult that Belgiojoso ‘has just advised me that the Italian libretto for my Sardanapale, which she assures me is a masterpiece, has been sent off; I will set to work on it immediately’.Footnote 118 One might argue that this timescale lends credence to Liszt's suspicion that Belgiojoso herself was the librettist: after delaying a year and a half to versify Acts 2–3, the full versified libretto was sent within a month of Liszt's letter reconfirming their collaboration after he threatened to employ Tadolini.Footnote 119 But such hypotheses remain as so many bubbles – vulnerable to the pinprick of evidence.

With the full versified libretto now at hand, Liszt finally began composing the score. He told Raff on 1 August 1849 that his Sardanapalo would be completed during the coming winter (see above, note 38). Raff advised J. J. Schott that composition was under way by 11 April 1850 (‘Right now Liszt is busy working on his opera Sardanapalo’);Footnote 120 and Liszt himself confirmed two weeks later that the creative process was finally alight (see again note 38), and set about securing a publishing contract for the opera from Léon Escudier, explaining on 4 February 1851: ‘I decided to work actively on the score. I expect to have a copy ready by the end of next autumn.’ Thus the music for Act 1 which Liszt did compose was almost certainly notated between April 1850 and February 1851. Table 2 summarizes the proposed timeline.

TABLE 2 a timeline for the genesis of liszt's sardanapale based on actions confirmed in extant correspondence

| ABBREVIATIONS | |

|---|---|

| FL | Franz Liszt |

| CB | Cristina Belgiojoso |

| Dec. 1845 | FL and CB decide to collaborate on Sardanapalo, to be drafted in French by Félicien Mallefille, and translated and versified by CB. |

| Feb. 1846 | Mallefille misses his first deadline to submit the prose scenario. |

| 21 May 1846 | With Mallefille protesting about a misunderstanding and requesting more money, FL expresses misgivings about their collaboration, and accepts CB's suggestion to procure the libretto from an unnamed Italian poet and political prisoner. |

| 25 Sept. 1846 | FL receives the prose scenario from CB's Italian poet. |

| 6 Oct. 1846 | Mallefille misses his second deadline; FL writes to him formally cancelling their arrangement (and pays him off); FL suggests compressing CB's planned three acts into two. |

| 9 Dec. 1846 | Mallefille sends the prose scenario in French, which FL ignores. |

| 1 Jan. 1847 | FL confirms receipt of CB's versified libretto for Act 1. |

| 22 Feb. 1848 | FL tells Gaetano Belloni (his secretary) of his intention to seek help from Giovanni Tadolini to complete the Italian libretto. |

| 12 May 1848 | CB confirms the versified libretto is finished. |

| 10 Aug. 1848 | CB sends the full versified libretto to FL. |

| 15 Jan. 1849 | CB tells FL his suggestion for an orgy scene is unrealistic, and implies that further revisions are forthcoming. |

| 11 Apr. 1850 | Joachim Raff (FL's assistant) confirms FL's composition of the opera is under way. |

| 4 Feb. 1851 | FL reasserts in past tense his earlier decision ‘to work actively on the score’. |

| Dec. 1851 | Raff writes to a musical confidante explaining that he anticipates orchestrating the opera soon. |

Why, then, did collaborative work cease with composition under way and just as the versified libretto had finally arrived? There are several possible answers, including Liszt's changing relation to Belgiojoso (for a time, potentially a romantic partner), his developing interest in and sympathy for Wagner's music, and the fate of Belgiojoso's unknown Italian poet.Footnote 121 A less conjectural and more plausible answer than these are the revisions to the final version of the libretto, understood as part of Liszt's aspiration towards what he called ‘musical drama’. With a nod to Occam's razor, then, I believe this to be the simplest, most practical and significant factor and thus focus closing comments on it here.

Liszt's correspondence indicates a consistent concern for the dramatic integrity of his opera. Writing to Grand Duke Carl Alexander on the same day as he fired Mallefille, Liszt explained: ‘You would not be able to believe, my Lord, the time and patience I shall need to carry through my librettos to perfection.’Footnote 122 As we have seen, he implored Belgiojoso twice to take personal responsibility for editing the libretto, and on at least two occasions made consequential suggestions regarding the opera's plot: the first regarding the scenario; the second the libretto.

First, on 6 October 1846 he sought to compress the proposed three acts into two:

A single observation concerning the scenario of Sardanapalo, which I humbly submit to your Highness: would it not be better to tighten the libretto into two acts; and to hasten the conclusion after scene v of Act 2 in moving to the dénouement, which must be incendiary from all points of view: […] In this way we would avoid the trailing, elegiac aspect (which would possibly cool it down) as it currently stands; and the overall effect would succeed better, in my opinion.Footnote 123

In the event, Sardanapalo remained a three-act work.Footnote 124 But it may be no coincidence that he would voice the same concern about the protracted historical plot of Donizetti's Dom Sébastien (1843), whose performances (he worried in 1854) ‘grow colder and colder continually’.Footnote 125 While we cannot know quite when such concerns crystallized in Liszt's mind, it seems reasonable to conclude that he may have been crafting his libretto negatively, with concern for what he saw as the weaknesses of contemporary Franco-Italian opera in mind.

Secondly, on 15 January 1849, Belgiojoso responded to a suggestion that Liszt evidently made but which has not survived:

I am going to write to your poet to get him to prepare a scene as you desire, but I don't very well know how he will manage an orgy scene in which there appears neither wine, amusements nor women. Have you yourself invented something new? In that case please reveal the secret to your poet, for I very much doubt whether a poor devil who has passed from prison to war, and from war to exile has a mind sufficiently attuned to guess such mysteries. As for myself, I would propose to you a mock orgy, that is to say, grand festive preparations that would end with a walk in the moonlight and a philosophical conversation. Sardanapalo would not, perhaps, have scorned that.Footnote 126

This complaint – that Liszt's request is unrealistic, unrealizable – is the last known correspondence about the opera between Liszt and Belgiojoso; it is also the only time there is a splitting of egos between the princess and the librettist. On this – frustratingly scant – basis, it seems most plausible that Liszt never drafted the later acts of Sardanapalo in N4 in part for the simple reason that he never received a revised version of them from Belgiojoso, and gave up on pursuing them from a librettist whose work (he worried) needed doctoring and adjusting.

Part 2

Declamatory style as ‘character’

More broadly, Liszt's two interventions indicate his underlying unease about what a modern libretto ought to entail. Three years after ceasing work on Sardanapalo, he published a series of 13 articles on contemporary opera in the Neue Zeitschrift which range from a historical overview of the genre to criticism of modern librettos and challenges for contemporary singers. His comments arguably retain a self-referential character, for it is librettists and their poetry, rather than musical matters, that dominate the discourse. The universal success of Auber's La muette de Portici was owed ‘to a very fortunate text selection’, he remarked; in contrast, Scribe's librettos for Donizetti are ‘too complicated for the audience’,Footnote 127 a representative case being Dom Sébastien, Donizetti's ‘most carefully worked-out production’ – which sought to amass ‘as many situations as possible’ and resulted in a wearying effect of continuous transformation and contrast. ‘During such procedures,’ he went on, ‘insufficient development naturally emerges, which compromises the entire poetic structure, and continually suppresses the portrayal of character,’ adding for good measure: ‘There is hardly any peripeteia.’Footnote 128 With these words in mind, there is a glimmer of frustration in his description of the shifting relations between poet and composer that he had inherited for Sardanapalo:

During Metastasio's time, it was merely an advantage for a composer to set one of this poet's poems, but during Scribe's time, it was absolutely essential. Until that time it was considered a lucky find when a composer came upon a libretto such as those written for Don Juan, Freischütz or Norma. […] After that time, one could not even write a thread of the best music without an interesting or piquant libretto.Footnote 129

Modern composers’ dependency on librettos and their drama was far greater than in the past, in other words. This observation cum complaint soon crystallized into a full-blown historical schema for the relationship between opera and poetry, setting the stage for what Liszt saw as opera's three elementary phases: an emphasis on the expression of feeling (Metastasio) was followed by an aspiration for dramatic situations that motivate such feelings coherently (Scribe, whose Robert le diable marks ‘the historic moment’ of equal collaboration between poet and composer), and thereafter ‘interest focussed on character development’, whose psychological explication on stage Liszt associates with the Wagner of Der fliegende Holländer, Tannhäuser and Lohengrin.Footnote 130 Accordingly, writing to Carl Alexander about his essay on Tannhäuser, Liszt's self-reflexive remark confirms the centrality of the libretto for contemporary opera: ‘This poetical analysis of Wagner's libretto was for me only an opportunity to express something that I feel very deeply.’Footnote 131

The challenge for modern composers, as Liszt saw it, was to eschew ‘earlier operatic forms’Footnote 132 while accommodating the telescoped requirements of opera's three elementary phases (cited above), wherein ‘every metamorphosis in style has enriched opera with a new moment, without suspending earlier moments. The aspiration to achieve situations does not preclude the expression of feeling. Likewise, the portrayal of character is little impeded down the path toward creating situations of expressing feeling.’Footnote 133 Such an accretion of requirements explains why ‘this epoch is at a great disadvantage’, he concludes, perhaps conveying a heaviness of thought that weighed down his own work.Footnote 134 Indeed, the surviving libretto to Liszt's single act for Sardanapalo feeds quite naturally into this quietly self-conscious writing about contemporary opera. It survives only as underlay in the continuous draft within N4. Marco Beghelli, Francesca Vella and David Rosen have deciphered and – where necessary – reconstructed this text for our edition; ultimately, very few words were missing or proved illegible, allowing us to access the words Liszt set with reasonable certainty.Footnote 135 On this basis, the plot for Act 1 of Liszt's opera can be summarized as follows.

In the royal palace at Nineveh, a chorus of concubines calls Mirra, a Greek slave-girl and favourite of the King, to the harem to raise her spirits (‘Come – your palpitating heart, / Shedding all worry, / Will forget the earth and the sky in ecstasy’). Mirra is unhappy, nostalgic for her lost home and sad about her current situation, but the chorus, unabated, venerates her as de facto queen (‘Among thousands of virgins […] / The king of Assyria has chosen you / Wreathe your brow with garlands of roses and vine leaves’). Despairing, Mirra seeks refuge and peace (‘Have no further thought for me!’) and relates her predicament in an aria and recitative: she is ridden with guilt for loving the man who conquered her homeland, and for adopting his Ashurian faith; she weeps while thinking of her mother on the one hand and of her love for Sardanapalo on the other, angrily declaring herself ‘a slave mocked by fate’. The King enters and asks why she is distressed; eventually she explains only that her adulterous role as his favourite carries no dignity (‘Your wife's vigilant gaze, / Her pallor accuses me’), but the King – infatuated – does not grasp the full circumstances of her unhappiness, promises to encircle her with the splendour of the royal palace and declares his love in a confident duet (‘Let us love as long as / The fervid age still smiles upon us’). While Mirra's predicament remains unresolved, Beleso – a soothsayer (Chaldean) and elder statesman – enters, warning of war. He accuses the King of enjoying comforts while ignoring ‘the inner voice of duty’ as insurgent leaders ready their forces against him. He urges the King to take up arms (‘Throw off your soft garments, / Set aside the distaff, grasp the sword!’) and earn the people's reverence, which only superficially attends the diadem he wears. Sardanapalo hesitates, lamenting that ‘every glory is a lie / If it must be bought with the tears / Of afflicted humankind’. In a lyric passage, Mirra wonders aloud why he is not stirred to ‘noble valour’, and makes a personal plea for action that heralds the moment of peripeteia, as the King is finally persuaded to fight (‘The earth is not vast enough for us to live together in peace […] Your wish will be fulfilled’). The act closes with a grand trio in which Beleso beats the drums of war and Mirra speaks of love inspiring lofty feelings in the King, who professes now to wear his royal purple more easily.

In keeping with Liszt's diagnosis that modern opera was transitioning towards a focus on individual character, the twin foci of the internal struggles of Mirra and Sardanapalo seem fitting: her bifurcated loyalties see her racked between the memory of family and heritage on the one hand and her genuine love for the King on the other; his vision of peaceful coexistence is increasingly exposed as illusory, forcing him to broaden his world-view and embrace the necessity of violence. Indeed, his change of mind – the decision finally to go to war – is the only action of consequence during the act, even though, as Dahlhaus observed of Isolde's love potion, it arguably only brings about what has already been determined by the characters’ psychological needs or ‘inner action’.Footnote 136

Far from being spectral nonentities or perfunctory grotesques, such roles are multifaceted, often complex in their motivations. The extent to which their text is scrutable at the level of the word is of course dependent upon how transparently any given utterance has been retrieved from the underlay of N4.Footnote 137 Nevertheless, Liszt relates the explication of character on stage genetically to poetry in precisely this way (vis-à-vis Wagner's appropriated philology in Part 2 of Oper und Drama):

The portrayal of characters, this first condition for the perfection of tragedy, will henceforth also be the first condition for the perfection of musical drama. Transplanting the depiction of characters into the realm of music makes a declamatory style an inevitable necessity. In addition to the action on stage, the characters make themselves known through the word: therefore Wagner lays extraordinary value upon the intrinsic beauty of the poetry in his operas.Footnote 138

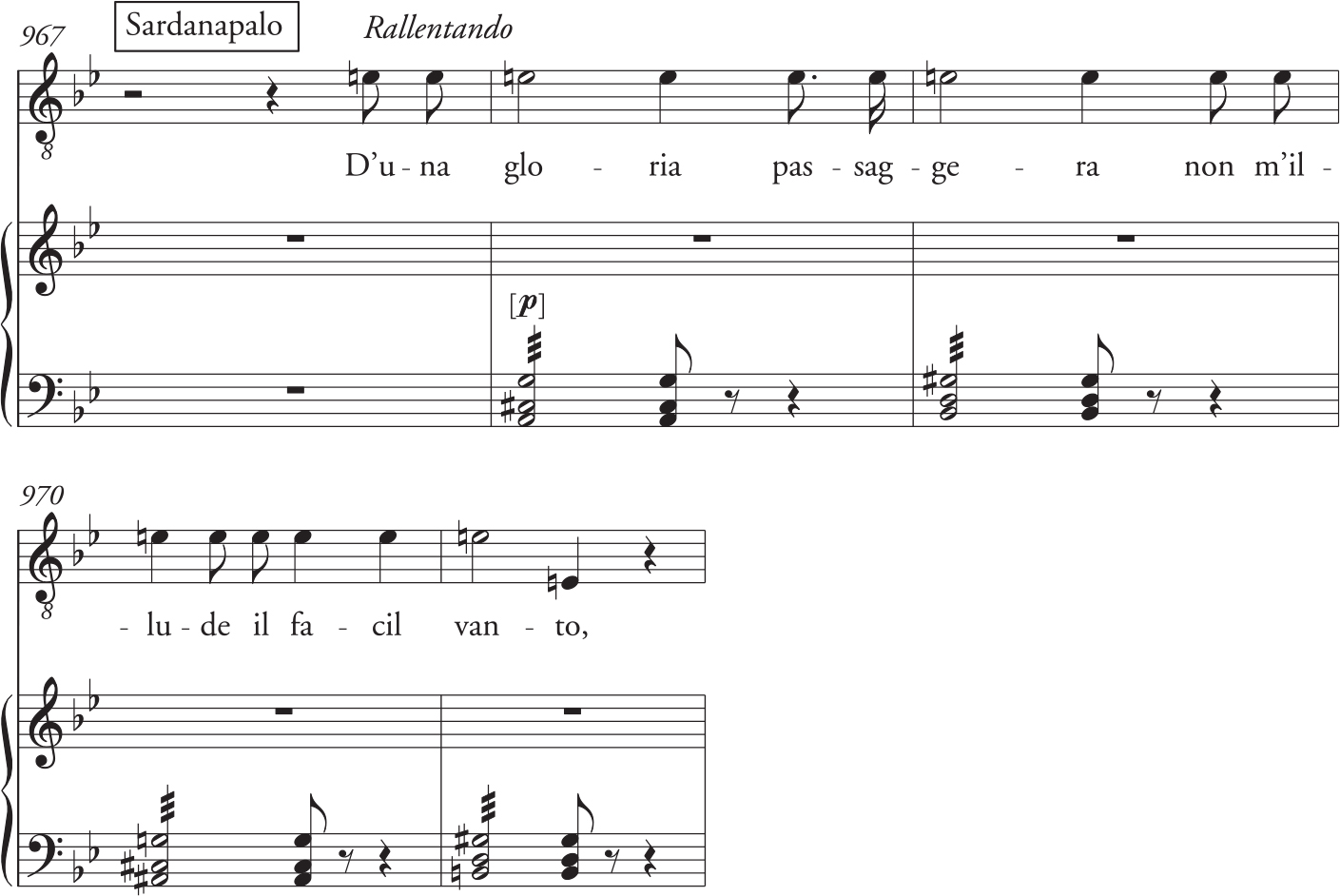

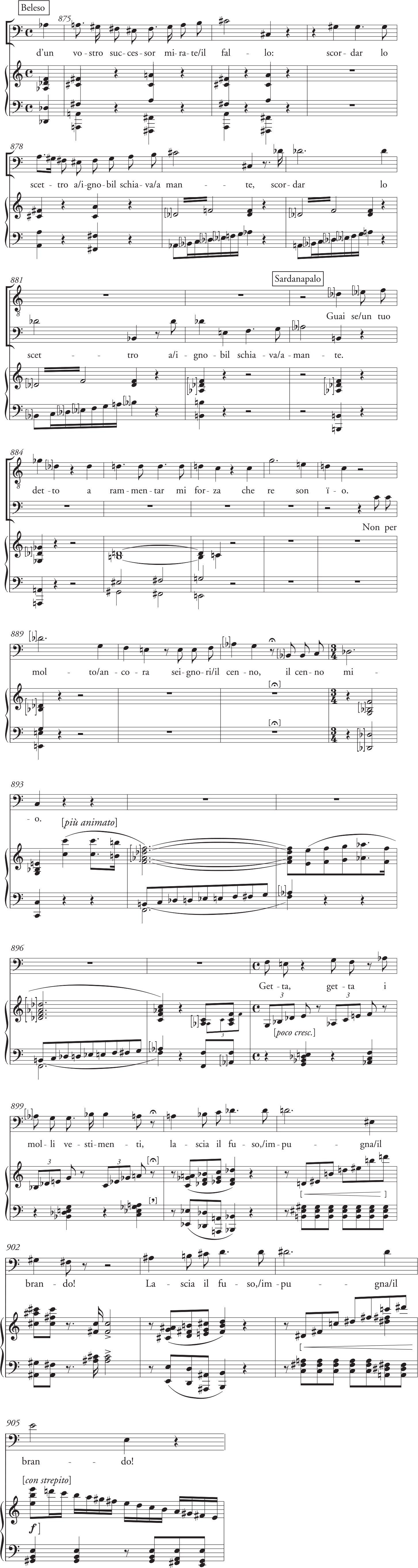

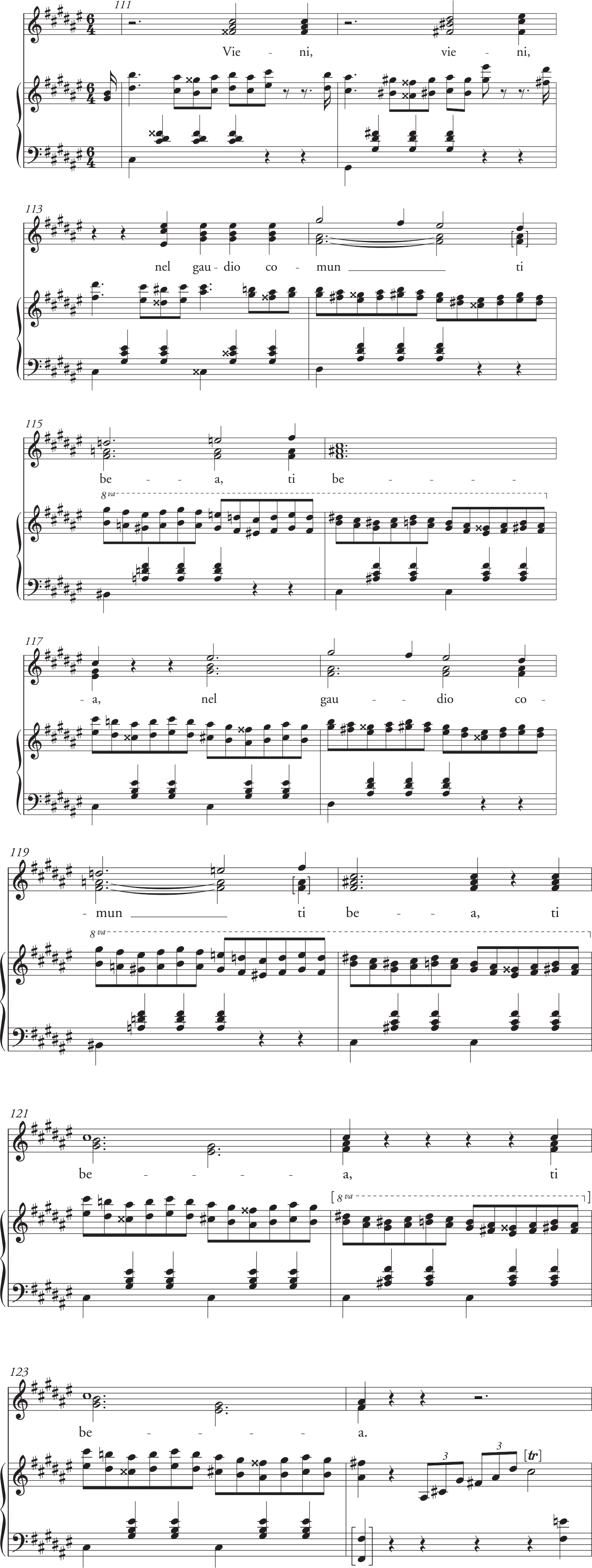

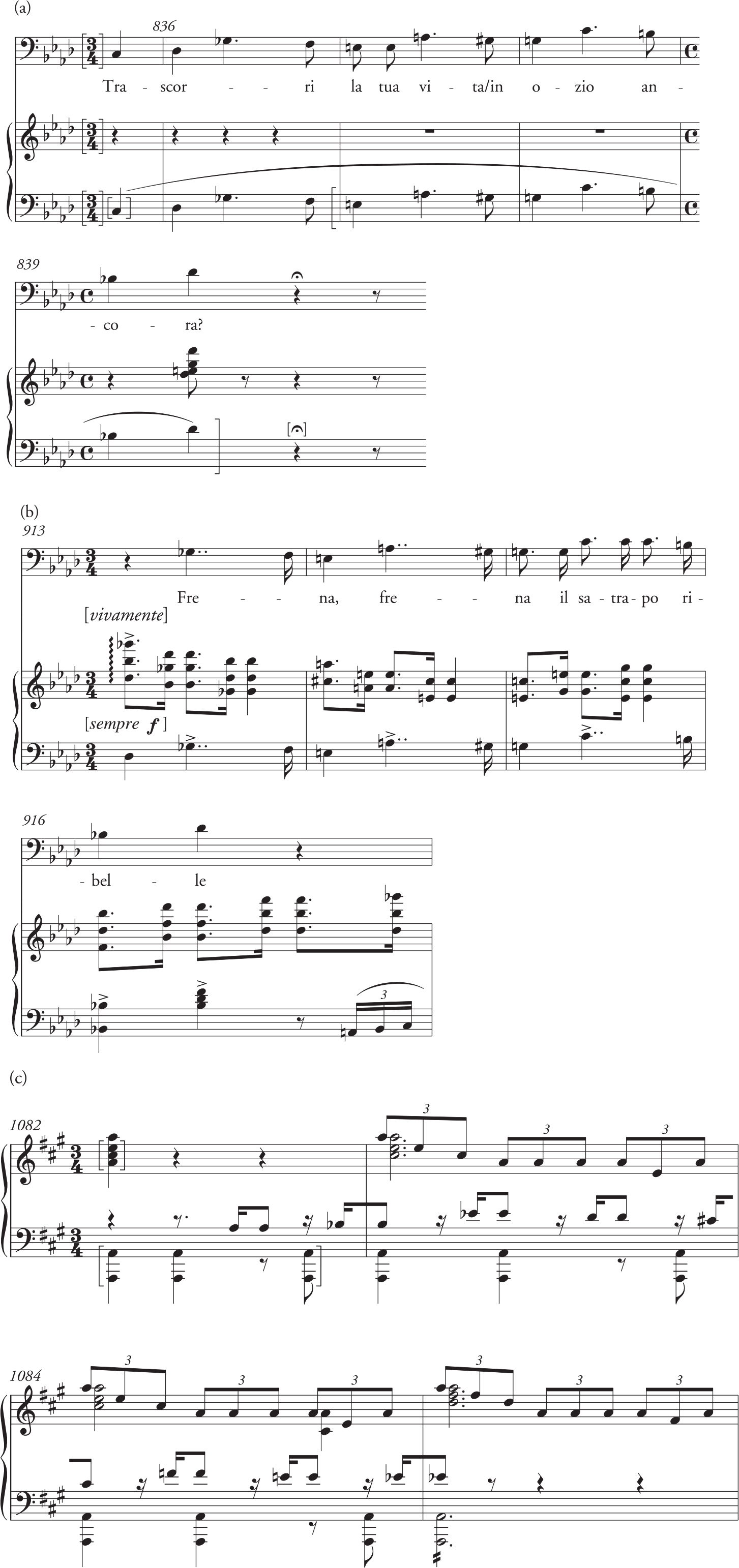

The declamatory melodic style referenced here was nothing less than a precondition for the emergence of ‘musical drama’, which Liszt felt was exemplified in the dramatic action of Meyerbeer's Robert and Rossini's Otello in particular.Footnote 139 In Sardanapalo, he draws on declamatory melody freely for all three principal roles, often to deliver kinetic text in moments of agitation. Consider the following three examples. When Mirra, alone, reflects angrily on her situation, the vocal line is structured by opposing tendencies: driven downwards by the surface voice-leading of falling semitones and upwards by the rising chromatic sequences. As Example 2 shows, a lamentation affect (cf. planctus / pianto) peppers the melodic line (bars 381, 383, 385, 389, 397–8, 401–2), while also underpinning rising sequences (LH, bars 380–5). Like the verses of Tannhäuser's hymn to Venus, both lines of Mirra's cri de coeur (‘Slave, alone, mocked by fate! / An error tempted my heart’) are repeated up a semitone, separately, even as the repeated monotone pitches they contain offer licence for declamatory delivery. Indeed, the use of monotone recitation is itself characteristic; in bars 967–71 (see Example 3), Sardanapalo decries the vanity of royally sanctioned violence on nothing but repeated e ♮ʹs (‘I am not deceived by the easy boast / Of a fleeting glory’). And in his first speech to the King, Beleso urges Sardanapalo to confront his regal responsibilities and stop indulging his desires while ignoring ‘the inner voice of duty’. Beleso's monosyllabic, rhythmically strident lines, given in Example 4, are decidedly unlike the structured bel canto expressiveness found in Liszt's transcriptions of Bellini and Donizetti. Alongside their rising chromatic sequences, the short, articulated phrases (bars 898–905), irregular phrase lengths and repeated declamatory pitches (bars 879–82, 885) point to Liszt's determination to write character, breath and agogic utterance into the shape of the melodic lines, resulting in an idiom we might more readily associate with the stylistic impulses of French ‘declamatory’ opera, or what Vincent d'Indy would later describe as a mode of drama ‘frequently even subordinating the musical form, the musical number, to the demands of the dramatic tone and the dynamics of the plot’.Footnote 140

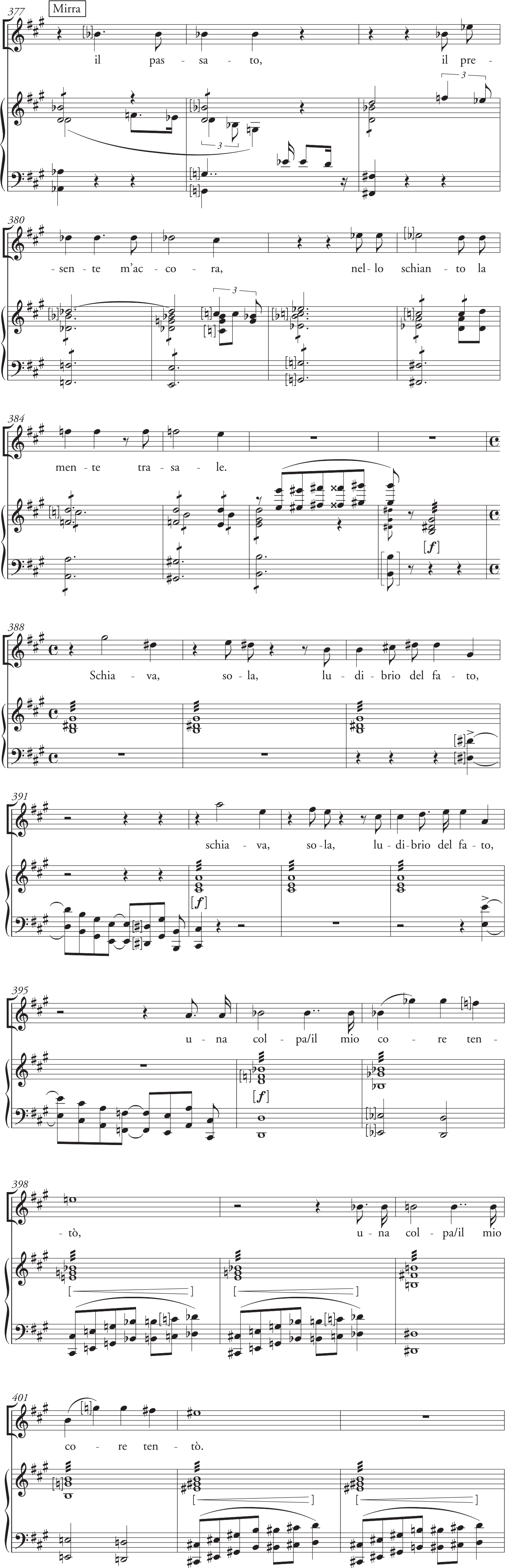

Example 2. Liszt's declamatory melodic style in Sardanapalo, bars 377–403. Edition © David Trippett.

Example 3. Sardanapalo's monotone recitation, Sardanapalo, bars 967–71. Edition © David Trippett.

Example 4. Beleso in dialogue with the King, illustrating Liszt's declamatory melody, with its character-driven, accented utterances; Sardanapalo, bars 875–905. Edition © David Trippett.

Harmonically, such passages also suggest that Hamilton's preliminary conclusion – that the music of N4 gives ‘the effect of a work written by two different composers’, where Liszt's chromatic language is reserved for the orchestra while ‘he seems frequently to rein [this] in […] as soon as the voice enters’ – may be unduly schematic.Footnote 141 On the contrary, such declamatory moments indicate the extent to which Liszt's vocal parts find expression outside diatonic Italianate melodic shapes, even as they observe a certain unrevised bel canto expressiveness; the examples above indicate that they share in the language of mid-century chromatic voice-leading as palpably as the conventions of expression that Liszt felt had shackled Rossini.

Methodologically, the problematic practice of reading composers’ reflections into analyses of their musical style (as though this could offer a closed circuit, insulated from the complex multitude of external and internal factors) is less indulgent in this case than it may seem. For Liszt's music in N4 never received critical attention, even from his inner circle at the Altenburg. It may never have been heard by anyone but him. Ipso facto, there is little option but to adopt such an approach for the present study, if the perspective of historical criticism is to be incorporated. On this basis it is telling that Liszt's contemporary writings posit the declamatory style as explicitly future-orientated, so much so that in his landmark essay (1855) on Berlioz's symphony Harold en Italie he twinned its role in modern opera with that of programmes in the modern symphony:

We consider the introduction of the program into the concert hall to be just as inevitable as the declamatory style is to the opera. Despite all handicaps and setbacks, these two trends will prove their strength in the triumphant course of their development. They are imperative necessities of a moment in our social life, in our ethical training, and as such will sooner or later clear a path for themselves.Footnote 142

Earlier that year, Liszt had conducted Schumann's Genoveva (1850), with its declamatory ‘recitative in time’ (Recitativ im Takt), remarking that despite its shortcomings as drama, and excepting Wagner's works, he preferred it to all operas of the past 50 years.Footnote 143 Did it represent the fruit of a move away from ‘the cult of stereotypical melody’, a move he saw initiated by Meyerbeer's Robert?Footnote 144 Perhaps. In any case, the historical inevitability driving both developments – declamation and programmes – is given as an ever more magnetic union of music and great literature, a union whose genetic relation to vocal music (that is, music with text) he confirms later in the same essay:

Through song there have always been combinations of music with literary or quasi-literary works; the present time seeks a union of the two which promises to become a more intimate one than any that have offered themselves thus far. Music in its masterpieces tends more and more to appropriate the masterpieces of literature. […] Why should music, once so inseparably bound to the tragedy of Sophocles and the ode of Pindar, hesitate to unite itself in a different yet more adequate way with works born of an inspiration unknown to antiquity, to identify itself with such names as Dante and Shakespeare? Rich shafts of ore lie here awaiting the bold miner, but they are guarded by mountain spirits who breathe fire and smoke into the faces of those who approach their entrance […] blacken[ing] what they do not burn, threatening those lusting after the treasure with blindness, suffocation, and utter destruction.Footnote 145

Described three years after work on Sardanapalo had ceased, this high-stakes scenario raises the possibility of an autobiographical reading in which Liszt-as-composer felt threatened with ‘utter destruction’, his own internal ‘mountain spirits’ stymieing progress on the opera, whose rich shafts of artistic ore had tempted a ‘bold miner’ such as him for seven years (rhetorically, perhaps an allusion to Wagner's ‘boldest sailor’ or Beethoven-as-Columbus, who first traversed the ‘apparently shoreless sea of absolute music’).Footnote 146

If Liszt pointedly omitted Byron from ‘such names as Dante and Shakespeare’, his inclusion in this pantheon of literary minds channelling ‘inspiration unknown to antiquity’ had been intimated a year earlier. Liszt's conceit for the organic magnificence of Romeo and Juliet provides a tangible link to Byron's Sardanapalus:

Shakespeare builds an altar out of green branches with condensed foliage, which he allows to flare up before our eyes until it becomes a pyre. We see the pure, fragrant and flowing flames of love between two young hearts until they yearn for death, until they are inflamed with envy for death. In the annals of martyrdom, love has never exhibited a more endearing sacrifice, neither in legend nor in myth.Footnote 147

Such imagery flickers against the shadow of his own operatic subject, the self-immolation of Sardanapalo and Mirra, where ‘fragrant and flowing flames’ echo Byron's command: ‘Bring cedar too, and precious drugs, and spices […] Bring frankincense and myrrh, too for it is / For a great sacrifice I build the pyre.’Footnote 148 Coded references rarely amount to conclusive evidence, but Liszt's wholesale borrowing of the imagery of Sardanapalus to interpret Romeo and Juliet at least suggests the comparable esteem in which he held these tragedies – perhaps, as it turns out, an esteem tipping into acute sensitivity, even inhibition.

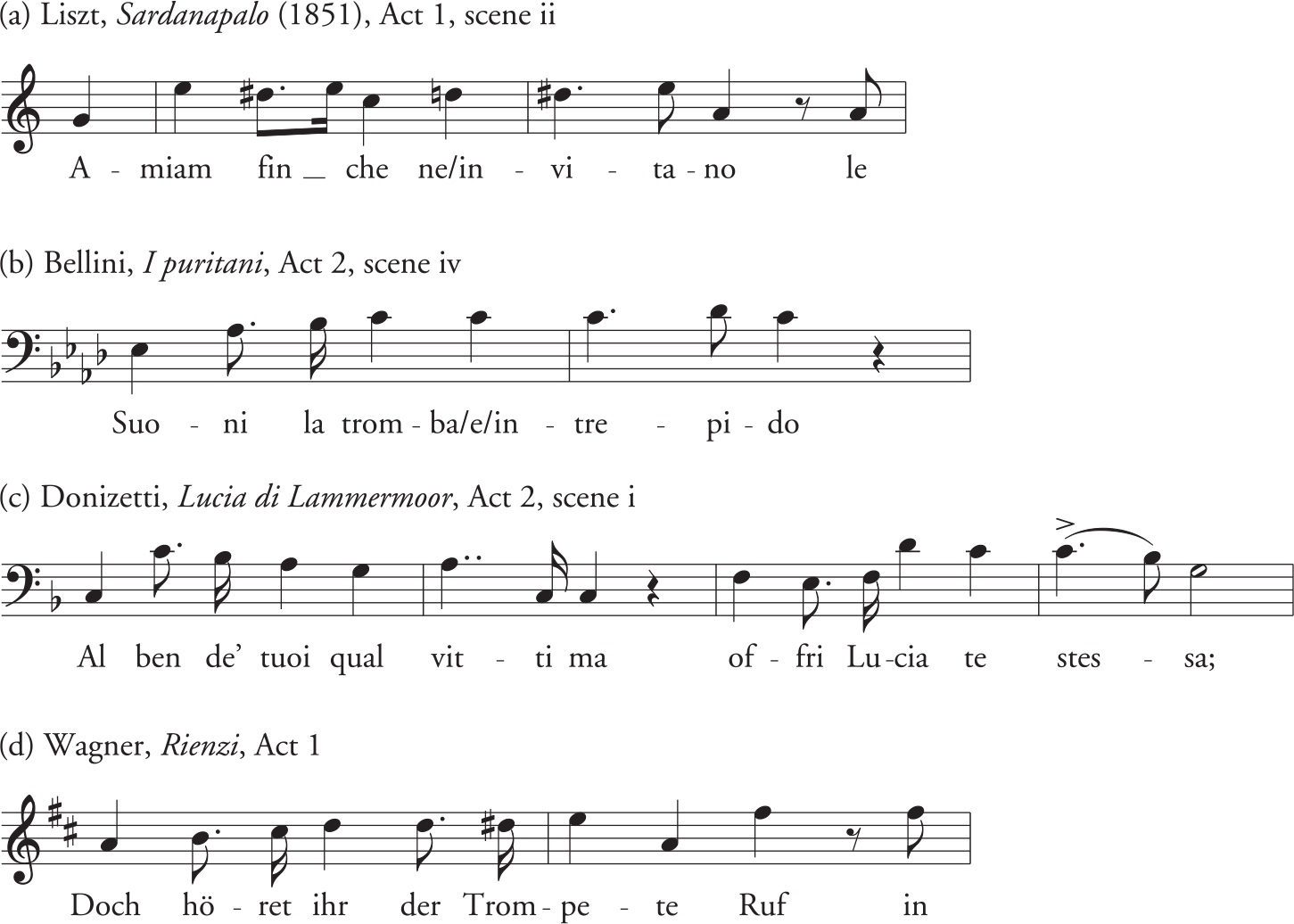

In this context it is unsurprising that close correspondences exist between Byron's tragedy and the libretto Liszt sourced via Belgiojoso. At first blush, this suggests that the author of Liszt's libretto was borrowing directly from Byron in places. Three examples are shown in Table 3. But if such semblances suggest a dependent relationship, clear differences between the plot of Byron's text and Liszt's libretto undermine any structural comparison.Footnote 149

TABLE 3 direct borrowings from byron's sardanapalus in liszt's opera libretto

| Byron (Sardanapalus, a Tragedy, 1821) | Liszt's libretto (trans. Rosen) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sardanapalus: Thou dost forget thee: make me not remember I am a monarch. (p. 11) | Sar: Guai se un tuo detto a rammentar mi forza / [che] re son io. | Sar: Woe betide you if what you say forces me to remember that I am king. |

| Sar: Oh! If it must be so, and these rash slaves / Will not be ruled with less, I'll use the sword / Till they shall wish it turn'd into a distaff . (p. 29) Salemenes: They say, thy sceptre's turn'd to that already. (p. 29)Beleses: I blush that we should owe our lives to such / A king of distaffs! (p. 80) | Bel: Getta [i molli vestimenti], / lascia il fuso, impugna il brando! | Bel: Throw off your soft garments, / Set aside the distaff, grasp the sword![an antithesisrepeated twice elsewhere] |

| Sar: Thou wouldst have me go / Forth as a conqueror … Sal: Wherefore not? Semiramis – a woman only – led these our Assyrians to the solar shores / Of Ganges.Sar: 'Tis most true. And how return'd? … And how many / Left she behind in India to the vultures? … she had better woven within her palace / Some twenty garments, than with twenty guards / Have fled to Bactria, leaving to the ravens, / And wolves, and men … / Her myriad of fond subjects. Is this glory? / Then let me live in ignominy ever. (pp. 16–17) | Sar: D'una gloria passaggera / non m'illud[e] il facil vanto, / ogni gloria è menzognera / se mercar si dèe col pianto / dell'afflitta umanità. | Sar: I am not deceived by the easy boast / Of a fleeting glory. / Every glory is a lie, / If it must be bought with the weeping / Of afflicted humankind. |

Byron's characters would sustain Liszt's creative work for several decades, of course. Central to Liszt's advocacy of musical progress is the need for individual character to be expressed via the most apposite medium, where the rules of genre do not inhibit what he saw as the goal of communicating a literary-musical art to modern audiences. ‘There are characters and feelings which can attain full development only in the dramatic; there are others which in no wise tolerate the limitations and restrictions of the stage.’Footnote 150 Declamatory melody has a part to play in the former, while in the latter, written programmes can bestow on instrumental music ‘the character of the ode, of the dithyramb, or the elegy, in a word, of any form of lyric poetry’.Footnote 151 Contemporaneous aestheticians would probe such claims sceptically, so we might conclude only that within a forward-looking union of music and literature, cast in the shadow of Byron, the variety of character-types and their necessary expressive freedoms justify – for Liszt – loosening ties equally with the established forms of Italian opera and with the Viennese symphony.

Pro and contra Italy

If Liszt's veneration of great literature lurks in the background to his ambitions in opera, this is typically expressed negatively, in critical remarks on Italian opera. See, for instance, caustic denunciations of Bellini's treatment of the Romeo and Juliet story (I Capuleti e i Montecchi) and Donizetti's vis-à-vis Hugo (Lucrezia Borgia). If Hugo's poetic intentions are ‘mutilated for the sake of operatic shenanigans’,Footnote 152 Bellini and Felice Romani provoke outright anger in Liszt:

How brutal, how raw and prosaic was Bellini's libretto's treatment of the wonderful transparency of this material. […] Not a trace has remained of all the outlines that create the individuality, fullness or life and truth of Shakespeare's characters. […] If we consider the barbaric manner with which the setters of opera texts defaced the most divine poetic creations, how quickly they mutilated them without mercy and compassion, and how they distorted them into some monstrous caricature, we cannot help but remark that they have indeed denigrated the beauty of the form in which the genius wanted to manifest his idea, a debt that can never be repaid.Footnote 153