Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 January 2020

Further progress in Josquin research and in the study of the music of the whole age will largely depend on detailed inquiry into the catalogue of the authentic works of the master. This will probably be the most burning problem, for how should the scholar pursue serious studies of Josquin's music, and how should the amateur find an approach to this outstanding musician, unless they know that the composition in their hands is really by Josquin?'

1 Blume, Friedrich, ‘Josquin des Prez The Man and the Music’, Josquin des Prez Proceedings of the Josquin Festival-Conference, ed Edward E Lowinsky and Bonnie J Blackburn (London, 1976), 18–27 (p 21).Google Scholar

2 ‘Memini summum quendam virum dicere, Josquinum lam vita defunctum, plures cantilenas aedere, quam dum vita superstes esset.’ The remark is from Forster's preface to Selectissimarum mutetarum tomus primus (Nuremberg, 15406), printed by Johannes Petreius Translation quoted from Edgar H Sparks, The Music of Noel Bauldeweyn (n p, 1972), 95 Other studies of authenticity in the work of Josquin include Edgar H Sparks, ‘Problems of Authenticity in Josquin's Motets’, Josquin des Prez Proceedings, 345–59; Milsom, John, ‘Circumdederunt. “A Favourite Cantus Firmus of Josquin's”?’, Soundings, 9 (1982), 2–10, Jaap van Benthem, ‘Lazarus versus Absalon About Fiction and Fact in the Netherlands Motet’, Tijdschrift van de Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis, 39 (1989), 54–82, Martin Just, ‘Josquins Chanson “Nymphes, Napées” als Bearbeitung des Invitatoriums “Circumdederunt me” und als Grundlage für Kontrafaktur, Zitat und Nachahmung’, Die Musikforschung, 43 (1990), 305–35, Joshua Rifkin, ‘Problems of Authorship in Josquin: Some Impolitic Observations, with a Postscript on Absalon, fili mi’. Proceedings of the International Josquin Symposium, Utrecht 1986, ed. Willem Elders (Utrecht, 1991), 45–52, and Patrick Macey, ‘Celt enarrant An Inauthentic Psalm Motet Attributed to Josquin’, ibid., 25–44Google Scholar

3 Sparks, The Music of Noel Bauldeweyn, 34–98. Jaap van Benthem has recently questioned the authenticity of one of the 18 accepted Masses, the Missa Une mousse de Biscaye, on grounds of style and source distribution, see ‘Was “Une mousse de Biscaye” Really Appreciated by L'ami Baudichon?’, Muzieh & Wetenschap, 1 (1991), 175–94Google Scholar

4 See Blackburn, Bonnie J, ‘Josquin's Chansons Ignored and Lost Sources’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 29 (1976), 54–6, also Lawrence F Bernstein, ‘Chansons Attributed to Both Josquin des Prez and Pierre de la Rue A Problem in Establishing Authenticity’, Proceedings Utrecht 1986, 125–52Google Scholar

5 Gustave Reese and Jeremy Noble, ‘Josquin Desprez’, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (London, 1980), ix, 713–38, revised in The New Grove High Renaissance Masters (London, 1984), 1–90 (pp 37–9)Google Scholar

6 Werken van Josquin des Pres, ed Albert Smijers and others (Amsterdam, 1921–69) For a complete catalogue of Josquin's works and their sources, see Charles, Sydney Robinson, Josquin des Prez A Guide to Research (New York, 1983).Google Scholar

7 Josquin's psalm motets are listed in the context of contemporary works in Edward Nowacki, ‘The Latin Psalm Motet 1500–1535’, Renaissance Studien Helmuth Osthoff zum 80 Geburtstag, ed Ludwig Finscher (Tutzing, 1979), 159–84Google Scholar

8 Teramoto, Manko, Die Psalmmotettendrucke des Johannes Petrejus in Nurnberg (Tutzing, 1983), 17Google Scholar

9 ‘In tanta igitur Musicae artis vastitate, cum aliquid typis excudere vellem, quod ad conservanda ea quae supersunt Musicae artis bona conferret, et ad eruenda ea, quae ad eius perfectionem adhuc desiderantur, studiosos et Musicos homines excitaret, Psalmos potissimum delegi. Primum, quia argumentum habent vere Musicum, hoc est divinum Deinde quia in illis componendis praestantissimi nostri seculi Musici, cum minime inepti fuerunt, turn omnes nervos intenderunt, ut quid in hac arte possent, posteris testatum relinquerent. Postremo ut illis cantitandis, studiosa luventus, aliud agens verbo Dei assuesceret.’ Tomus primus psalmorum selectorum (Nuremberg, 1538), sig aiii-aiiiv. I would like to thank Jeremy Noble for assistance with the translationGoogle Scholar

10 Quoted in Helmuth Osthoff, Josqum Desprez, i (Tutzing, 1962), 88Google Scholar

11 Quoted in Jessie Ann Owens, ‘Music Historiography and the Definition of “Renaissance”’, MLA Notes, 47 (1990), 305–30 (pp 307–8). See Heyden, Sebald, De arte canendt, trans Clement A Miller (American Institute of Musicology, 1972).Google Scholar

12 Josquinum celebemmum hujus artis Heroem facile agnoscent omnes, habet enim vere divinum et inimitabile quidam ’ Quoted in Osthoff, Josquin Desprez, 1, 89 For a comprehensive account of the Josquin ‘Renaissance’ in Germany from 1537 to 1560, see ibid., 82–90 See also Owens, ‘Music Historiography’, 310–12Google Scholar

13 Glarean, Dodecachordon, trans Clement A Miller, ii (American Institute of Musicology, 1965). 264Google Scholar

14 Glarean, Dodecachordon, ii, 248. I have revised the translation slightly to make it more readable. Glarean apparently completed work on the Dodecachordon in about 1530, so he would be referring to music composed since 1500 as an ars perfecta, this date coincides with the latter period of Josquin's life See Lichtenhahn, Ernst, ‘“Ars perfecta” – zu Glareans Auffassung der Musikgeschichte’, Festschrift Arnold Geering, ed Victor Ravizza (Berne, 1972), 129–38.Google Scholar

15 On the use of the term ‘classic’, René Wellek provides a succinct overview of its history ‘Classicus first occurs in Aulus Gellius, a Roman author of the 2nd century A D, who in his miscellany Noctes Atticae (19, 8, 15) refers to classicus scriptor, non proletarius, applying a term of the Roman taxation classes to the ranking of writers Classicus means there “first class”, “excellent”, “superior” The term seems not to have been used in the Middle Ages but it reappears in the Renaissance in Latin and soon in the vernaculars The first recorded appearance in French [is] in Thomas Sebillet's L'art poetique (1548).’ See ‘Classicism in Literature’, Dictionary of the History of Ideas, ed Philip P Wiener (New York, 1968), 449–56 (p 451)Google Scholar

16 ‘For posterity the name of Cicero has come to be regarded not as the name of a man, but as the name of eloquence itself. Let us, therefore, fix our eyes on him, take him as our pattern.’ Institutionis oratoriae, trans Harold Edgeworth Butler, iv (London, 1922), 65Google Scholar

17 Quoted in Sparks, The Music of Noel Bauldeweyn, 95Google Scholar

18 Separate volumes of The New Josquin Edition are being prepared by individual editors working under the guidance of the editorial board, including Willem Elders, Lawrence F Bernstein, Howard Mayer Brown, Martin Just and Herbert Kellman One volume has appeared so far Secular Works for Three Voices, ed Jaap van Benthem and Howard Mayer Brown, 27 (Utrecht, 1987)Google Scholar

19 Qui habitat is edited in Werken van Josquin des Pres, 37 (Amsterdam, 1954), no 52 Helmuth Osthoff praises the lucidity of the writing, and compares it to another late work of Josquin's, In exitu Israel, with which it is often paired in the sources. See Osthoff, Josquin Desprez, ii, 128 For information regarding the connection of Miserere mei, deus with Ercole I d'Este, see Lockwood, Lewis, ‘Josquin at Ferrara’, Josquin des Prez Proceedings, 103–37 (p 117)Google Scholar

20 Translation adapted from the Douay Reims Bible (Rockford, Ill, 1989) The Douai Reims Bible is a direct translation from the Vulgate by an English priest, Gregory Martin, and thus provides a more literal rendering into English of the text of Psalm 90 than the King James version Undertaken at the Catholic College at Douai, France, the New Testament appeared in 1582 at Reims, while the Old Testament was published in 1609–10 at DouaiGoogle Scholar

1 a Qui habitat in adjutorio altissimiGoogle Scholar

b in protectione dei caeli commorabiturGoogle Scholar

2 a Dicet domino susceptor meus es tuGoogle Scholar

b et refugium meum deus meus, sperabo in eumGoogle Scholar

3 a Quoniam ipse liberavit me de laqueo venantium,Google Scholar

b. et a verbo asperoGoogle Scholar

4 a Scapulis suis obumbrabit tibiGoogle Scholar

b. et sub pennis ejus sperabisGoogle Scholar

5 a Scuto circumdabit te veritas ejusGoogle Scholar

b non timebis a timore nocturnoGoogle Scholar

6 a A sagitta volante in die, a negotio perambulante in tenebrisGoogle Scholar

b ab incursu, et daemonio meridianoGoogle Scholar

7 a Cadent a latere tuo mille, et decern millia a dextris tuisGoogle Scholar

b ad te autem non appropinquabitGoogle Scholar

8 a Verumtamen oculis tuis considerabisGoogle Scholar

b et retributionem peccatorum videbisGoogle Scholar

9.a Quoniam tu es domine spes meaGoogle Scholar

b altissimum posuisti refugium tuumGoogle Scholar

Secundo parsGoogle Scholar

10 a Non accedet ad te malum.Google Scholar

b. et flagellum non appropinquabit tabernaculo tuo 11.a Quoniam angelis suis mandavit de teGoogle Scholar

b ut custodiant te in omnibus vus tuisGoogle Scholar

12 a. In manibus portabunt teGoogle Scholar

b ne forte offendas ad lapidem pedem tuumGoogle Scholar

13 a. Super aspidem et basiliscum ambulabisGoogle Scholar

b. et conculcabis leonem et draconemGoogle Scholar

14 a Quoniam in me speravit, liberabo eumGoogle Scholar

b. protegam eum, quoniam cognovit nomen meumGoogle Scholar

15.a Clamabit ad me, et ego exaudiam eum cum ipso sum in tribulationeGoogle Scholar

b. eripiam eum et glonficabo eumGoogle Scholar

16 a Longitudine dierum replebo eumGoogle Scholar

b. et ostendam illi salutare meumGoogle Scholar

[1a.] Qui habitat in adjutorio altissimiGoogle Scholar

21 Anthony M Cummings, ‘Toward an Interpretation of the Sixteenth-Century Motet’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 54 (1981), 43–59, see also Jeremy Noble, ‘The Function of Josquin's Motets’, Tijdschrift van de Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis, 35 (1985), 9–22Google Scholar

22 Cummings, ‘Toward an Interpretation’, 48Google Scholar

23 Das altere Gebetbuch Maximilians I., with introduction by Wolfgang Hilger (Graz, 1973), f 33.Google Scholar

24 The first book dates from 1533 (New York, The Pierpont Morgan Library, M 491, f 44), and Psalm 90 bears the heading ‘Hic psalmus dicitur contra omnia adversa’ The other manuscript with Psalm 90 in the section of free prayers seems to have been prepared as a replacement for the well-worn M 491, and dates from after 1547 (The Pierpont Morgan Library, M 696, f 32)Google Scholar

25 Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. lat 10532, f 289 See Leroquais, Victor, Les livres d'heures manuscrits de la Bibliothèque Nationale, i (Paris, 1927), 328Google Scholar

26 After the death of Ferrante in 1494, his warlike son Alfonso succeeded to the throne, but the French King Charles VIII, laying a simultaneous claim to the title through his Angevin ancestors, invaded Italy in 1494 Meeting little or no resistance, he entered Naples early in 1495 Alfonso, deserted by his allies, abdicated to his ferocious son Ferrammo, but the latter also fled as Charles entered Naples victoriously The French were soon driven out, and Ferrammo was succeeded by his gentle-natured uncle, Frederick III, in 1496 See The New Cambridge Modern History The Renaissance, 1493–1520, ed George Richard Potter, i (Cambridge, 1957), 350–4 Not many years later, French troops under Louis XII again stood at the walls of Naples, and the ill-starred Frederick, betrayed by his Spanish allies, abdicated the throne in 1501 Given the duchy of Anjou by Louis XII in compensation, he ended his days in France in 1504 (ibid, 357–8). One can well imagine that Frederick had many occasions after 1496 to recite the psalm against his enemies In an earlier generation in Naples, the singing of what appears to be polyphonic settings of psalm texts was cultivated in celebration of battle victories by King Alfonso (r 1443–58) In a letter of 1473 to the maestro di cappella of King Ferrante, Duke Galeazzo Maria Sforza of Milan requested that he send some of the psalms that the late King Alfonso was accustomed to have sung for him ‘after he had some victories’ (‘la copia de quelli salmi che faceva cantare la bona memoria del Re Alfonso quando sua Maestà haveva qualche victorie’), see Isabel Pope and Masakata Kanazawa, The Musical Manuscript Montecassino 871 (Oxford, 1978), 562 On the importance of Josquin's psalm motets at the French royal court, see Macey, Patrick, ‘Josquin's Misericordias domini and Louis XI’, Early Music, 19 (1991), 163–77Google Scholar

27 New York, The Pierpont Morgan Library, M 227, f 127Google Scholar

28 New York, The Pierpont Morgan Library, M 53, f 136vGoogle Scholar

29 New York, The Pierpont Morgan Library, M 14, f 208v Books of hours published in the sixteenth century include one from Venice in 1512 with the heading ‘Psalmos contra inimicos et diverses ac varias tribulationes’, Officium beate Marie (Venice, 1512), sig. S ii See also Horae (Paris, Thielman Kerver, 1505), sig O Vv, and Horae (Paris, Gilles Hardouin, 1513), unnumbered folios (near the opening), where the psalm is titled ‘Psalmus contra omnia adversa’ An Italian manuscript book of hours from the sixteenth century contains the psalm near the end with the free prayers Florence, Biblioteca Laurenziana, Antinori 100, f 77, the heading is ‘Ant Angielum nobis medicum salutis’ One French example, in Baltimore, Walters Art Gallery, MS W 446, f 92v, was copied in Tours or Bourges for Jean Lallemant le Jeune c 1510–20, it includes Psalm 90 near the end, with the instruction to recite it against enemies and various tribulations. See Wieck, Roger, Time Sanctified The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life (New York, 1988), 206 One of the earliest appearances of the psalm seems to be in the book of hours of Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy (1396–1467), where it is prefaced with the simple heading ‘Psalmus David’, in The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, MS 76 F.2, f. 210. During the past decade I have examined several hundred books of hours in libraries in the United States and Europe, Psalm 90 is one of the few psalms that occur as independent prayers, and its occurrence is relatively rareGoogle Scholar

30 Robert J Snow, ‘Toledo Cathedral MS Reservado 23 A Lost Manuscript Rediscovered’, Journal of Musicology, 2 (1983), 246–77 (pp 267, 274–7), and Herbert Kellman, ‘Josquin and the Courts of the Netherlands and France The Evidence of the Sources’, Josquin des Prez Proceedings, 181–216 (p 214)Google Scholar

31 Bente, Martin, Neue Wege der Quellenkritik und die Biographie Ludwig Senfls (Wiesbaden, 1968), 70Google Scholar

32 This type of passage emphasizes important words in a motet or madrigal whose musical texture is prevailingly contrapuntal The term noema was adopted for this technique by Joachim Burmeister, the German theorist who wrote about musico-rhetorical devices See his Musica poetica (Rostock, 1606, facsimile edn Kassel, 1955), 59–60Google Scholar

33 Similar passages occur in Josquin's late psalm motet In exitu Israel, for exampleGoogle Scholar

34 Edited in Werken, 42 (Amsterdam, 1956), no 70Google Scholar

35 Translation after Douay Reims BibleGoogle Scholar

1 a Levavi oculos meos in montesGoogle Scholar

b unde veniet auxilium mihiGoogle Scholar

2 a Auxihum meum a domino,Google Scholar

b qui fecit caelum et terramGoogle Scholar

3 a Non det in commotionem pedem tuum,Google Scholar

b neque dormitet qui custodii teGoogle Scholar

4 a Ecce non dormitabit neque dormiet,Google Scholar

b qui custodii IsraelGoogle Scholar

Secunda parsGoogle Scholar

5 a. Dominus custodii te, dominus protectio tua,Google Scholar

b super manum dexteram tuamGoogle Scholar

6 a. Per diem sol non uret teGoogle Scholar

b neque luna per noctemGoogle Scholar

7 a Dominus custodii te ab omni malo,Google Scholar

b custodial animam tuam dominusGoogle Scholar

8 a Dominus custodial introitum tuum et exitum tuumGoogle Scholar

b ex hoc nunc, et usque in saeculumGoogle Scholar

[1.] Levavi oculos meos in montesGoogle Scholar

36 Osthoff, Josquin Desprez, ii, 138.Google Scholar

37 Dahlhaus, Carl, Untersuchungen uber die Entstehung der harmonischen Tonalltat (Kassel, 1967, repr 1988), English translation, Studies on the Origin of Harmonic Tonality, trans Robert O Gjerdingen (Princeton, 1991), 261–3. Saul Novack remarks on the harmonic control of the bass line of Levavi oculos, noting that it frequently outlines motions from I to V in a progressive manner, see ‘Tonal Tendencies in Josquin's Use of Harmony’, Josquin des Prez Proceedings, 317–33 (pp 330–3). My thanks to Cristle Collins Judd for reminding me of these two discussions, she arrived independently at doubts about the authenticity of Levavi oculos I would like to thank Ms Judd for sharing with me unpublished material on the use of real and tonal answers in the imitative structures of the two motets from her forthcoming dissertation, ‘Aspects of Tonal Coherence in the Motets of Josquin Modal Types, Ut, Re, Mi Tonalities, and Chant-Based Tonality’ (King's College, London)Google Scholar

38 Works attributed to Josquin that trace the same interval in the superius are the Gloria of the Missa D'ung aulire amer and the Credo of the Missa La sol Ja re mi, see Fallows, David, ‘The Performing Ensembles in Josquin's Sacred Music’, Tijdschrift van de Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muztekgeschiedenis, 35 (1985), 32–64 (p 47)Google Scholar

39 Carl Dahlhaus remarked on the almost exact similarity of the two cadences, see Studies on the Origin of Harmonic Tonality, 265.Google Scholar

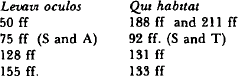

40 Compare the following bars of the two motets.Google Scholar

| Levavi oculos | Qui habitat |

| 50 ff | 188 ff and 211 ff |

| 75 ff (S and A) | 92 ff. (S and T) |

| 128 ff | 131 ff |

| 155 ff. | 133 ff |

41 Edited in Werken, 16 (Amsterdam, 1936), no 31, and 52 (Amsterdam, 1954), no 93Google Scholar

42 Osthoff, Josquin Desprez, ii, 67. ‘Es ist eine gediegene Komposition von ernster Haltung, doch ohne grossen rhetorischen Zug, und die Frage, ob Josquin wirklich der Autor ist, kann nicht mit Sicherheit entschieden werden’ See also n, 296.Google Scholar

43 Reese and Noble, ‘Josquin Desprez’, 735Google Scholar

44 Glarean, Dodecachordon, ii, 271–2Google Scholar

45 On other psalm motets possibly composed by Josquin for kings of France, including Memor esto, see Macey, Patrick, ‘Josquin's Misericordias domini and Louis XI’.Google Scholar

46 Reese and Noble, ‘Josquin Desprez’, 735.Google Scholar

47 Osthoff, Josquin Desprez, ii, 67Google Scholar

48 Note values in all examples have been reduced by halfGoogle Scholar

49 See Macey, Patrick, ‘Josquin's “Little” Ave Maria A Misplaced Motet from the Vultum tuum Cycle?’, Tijdschrtft van de Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis, 39 (1989), 38–53Google Scholar

50 Institutio oratoria, 75 (X ii 1–3) Humanist teachers in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries instructed their pupils to take notes on their reading and prepare their own lexica and compendia of the works of Cicero and other classical authors An illuminating description of the education of the boy-king Edward VI of England in the 1540s serves as an example ‘The exercises he performs are meticulous, dutifully imitative rhetorical compositions, in which the balanced phrase has clearly occupied the pupil's mind, rather than the weightiness of the issue For one short period Edward produced carefully competent and utterly soulless orations, crafted out of Cicero's and Erasmus’ borrowed phrases.' See Anthony Grafton and Lisa Jardine, From Humanism to the Humanities Education and the Liberal Arts in Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Europe (Cambridge, Mass, 1986), 16, 155Google Scholar

51 See Brown, Howard Mayer, ‘Emulation, Competition, and Homage Imitation and Theories of Imitation in the Renaissance’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 35 (1982), 1–48, Leeman L, Perkins, ‘The L'homme armé Masses of Busnoys and Okeghem A Comparison’, The Journal of Musicology, 3 (1984), 363–96, J Peter Burkholder, ‘Johannes Martini and the Imitation Mass of the Late Fifteenth Century’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 38 (1985), 470–523, ‘Communication’, Leeman L Perkins and J Peter Burkholder, ibid., 40 (1987), 130–9, Paula Higgins, ‘In Hydraulis Revisited. New Light on the Career of Antoine Busnois’, ibid., 39 (1986), 76–82, M Jennifer Bloxam, ‘In Praise of Spurious Saints The Missae Floruit egregiis by Pipelare and La Rue’, ibid., 44 (1991), 207–12, and Macey, ‘Celt enarrant‘Google Scholar

52 Rob C Wegman, ‘Another “Imitation” of Busnoys's Missa L'Homme armé - and Some Observations on Imitatio in Renaissance Music’, Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 114 (1989), 189–202CrossRefGoogle Scholar

53 It should be remembered that the German theorist Johannes Frosch (c 1480–1533), who was active in Augsburg and Nuremberg, has a section titled ‘De imitatione Authorum’ near the end of his Rerum musicarum opusculum rarum (Strasbourg, 1532) But the type of borrowing that he discusses is different from the examples discussed above that were based on Josquin's psalm motets Here he instructs the student on borrowing model figures of counterpoint and working them into new compositions, but his examples are all cadential figures Frosch provides a listing of individual cadential figures, then provides two motets of his own composition, one for four voices and the other for six, showing how these figures are worked into the texture See Wolff, Helmuth Christian, ‘Die ȧsthetische Auffassung der Parodiemesse des 16 Jahrhunderts’, Miscelánea en homenaje a Monseñor Higinio Anglés, ii (Barcelona, 1961), 1011–17 (pp. 1015–17); and Lewis Lockwood, ‘On “Parody” as Term and Concept in 16th-Century Music’, Aspects of Medieval and Renaissance Music A Birthday Offering to Gustave Reese, ed Jan La Rue (New York, 1966), 560–75 (p 569, n 15) Joachim Burmeister directly addressed the issue of imitatio by concluding his Musica poetica with a chapter titled ‘De Imitatione’, in which he put forward a later generation of composers such as Clemens non Papa, Orlandus Lassus and ten others as models for novices, see Musica poetica, 74–6Google Scholar

54 In this respect, Quintilian remarks. ‘Whatever is like another object, must necessarily be inferior to the object of its imitation, just as the shadow is inferior to the substance’ Institutio' oratoria, 79–80 (X.ii 11)Google Scholar

55 See Macey, , ‘Celi enarrant’, and Sparks, ‘Problems of Authenticity’ I would like to thank Michael P Long, Jeremy Noble and Gretchen Wheelock for their comments on a draft of this articleGoogle Scholar