聞人說洞天石室,有錄文金簡天書,凡夫讀之不能解釋,不能信從。

此卷書,凡夫讀之亦不能解釋,不能信從。

I've heard that in stone studios of grotto-heavens there hide celestial writings inscribed on gold slips. Mortals read them, but cannot understand them or follow them.

This book is the same. Mortals read it, but cannot understand it or follow it.

—Liu E's auto-commentary to the eleventh chapter of The Travels of Lao CanIntroduction: Hu Shih's fury

This article studies the late Qing Chinese novel The Travels of Lao Can (Lao Can youji 老殘遊記, hereafter The Travels) authored by Liu E 劉鶚 (1857–1909) as a book of prophecy. The Travels is arguably the best-known and most acclaimed Chinese novel of this period. In a century-long process of canonisation, scholars have acknowledged the many contributions of the novel to Chinese literary history: its exploitation of the capacities of the vernacular language, its innovative adoption of various genres (exposé, political novel, martial arts fiction, and detective story), its sophisticated gesture toward national allegory, the unusual design of its plot structure (though for some this is a flaw), its subtle balance between the traditional Chinese xiaoshuo 小說 tradition and the new Western literary techniques — to name the most often mentioned.Footnote 1 Despite the existence of many different reading strategies and approaches to this text, The Travels is without doubt a novel, a piece of fiction, and a literary masterpiece of the first order. Therefore, to say that it is a “book of prophecy” would inevitably surprise and even upset many. However, this statement is neither attention-seeking nonsense nor some form of metaphorical word play. It is a simple statement of historical fact — a fact that has been deliberately repressed and forgotten over the course of the novel's canonisation. A careful interrogation of material and discursive traces left in the late Qing and early Republican periods reveals that there exists a huge gap between how we perceive The Travels today and how it was read and circulated in the immediate decades after its publication. For a considerable proportion of the readers of that period, The Travels was not a literary work, but a book of prophecy, a mythical repository of riddles, ciphers, and secret knowledge, and a revelation of a form of occult wisdom that might explicate everything, from the past to the future. It is this perception, instead of its merits as a literary work, that accounted for its high popularity in the late Qing and early Republican book market. This popular perception invoked discomfort from some of the progressive intellectuals, who saw the occult as a disturbing leftover of “feudal superstitions” and saw otherwise great potential in The Travels as a materialisation of their advocacy for the “new literature”. They therefore made efforts to collate the text and erect the interpretation of the book as a resolute literary work. Gradually, a new perception of the book was established, while the old one disappeared. In the end, the status of The Travels in the pantheon of the Chinese literary canons was secured, yet its affordance of mediating the complexity of that chaotic historical period was also unfortunately attenuated.

This article explores this historical process in detail and restores what has been forgotten in The Travels’ reception history. Yet, the purpose of this article is not to argue that reading The Travels as a prophecy is a more correct or righteous approach; nor am I interested in contesting the literary merits that scholars have insightfully pointed out. Like its author Liu E, who had multiple, controversial, and sometimes self-contradictory identities (a flood control specialist, an entrepreneur, a philanthropist, a classicist, a collector of oracle bones, a writer, a “traitor” of the national interest, etc.), The Travels is also complicated and multifaceted.Footnote 2 Clearly, to believe in the occult power of The Travels and to essentialise it as a book of prophecy was a misreading of an otherwise far richer and more sophisticated work. But instead of repressing the mistake (or glorifying it), this article holds that it is more productive to acknowledge its existence and to see what we can learn from it. I hope that as we dig into the historical details that were long forgotten, new light will be shed on this familiar text and answers to these questions will come into view: What qualities of the book made people take it as a prophecy? What was Liu E's purpose in incorporating such qualities into his text? If the prophetic power of The Travels was simply a myth, then who and what kind of mechanisms were involved in the making of the myth, and why did readers embrace it? What does this story tell us about the entangled relationship between print culture, literary consumption, and the production of occult knowledge in this changing era?

We begin these explorations with a quick review of the textual history of The Travels. In 1903, Liu E started serialising the work in the fiction journal Xiuxiang xiaoshuo 繡像小說 (illustrated fiction) published by the Commercial Press 商務印書館 under the alias Hongdu Bailiansheng 洪都百鍊生. The initial motivation for him to do so remains debateable, but it was certainly not a carefully planned project.Footnote 3 The Travels is the only novel Liu E wrote in his lifetime, and becoming a novelist never seems to have been a priority for the author, who diligently multitasked in many kinds of enterprises. In 1904, the serialisation was terminated by the author's side because of the Commercial Press’s censorship of the “superstitious contents” in the novel.Footnote 4 In 1906, the novel was moved to the Tianjin Daily News 天津日日新聞. The new serialisation restarted from the first chapter and ended in the twentieth, making up a complete twenty-chapter novel (which the scholar Timothy Wong calls the “Text Proper”). In 1907, Liu E embarked on a short-lived serialisation of the Erji 二集 (the “Sequel” in Wong's term), and may have started drafting a totally different Lao Can story (the “Fragment” in Wong's term), but both had very limited circulation and influence.Footnote 5 As a result, the title The Travels of Lao Can usually refers to the twenty-chapter Text Proper unless otherwise noted. The Text Proper proved to be a phenomenal success. Within the first decade after its initial publication, at least nine publishers were selling their own editions, although none of them had even figured out to whom the alias Hongdu Bailiansheng really referred.Footnote 6

In 1925, The Travels received a well-collated and punctuated new edition from the Yadong Library 亞東圖書館 — one that proved to be an authoritative version and the master copy for many later editions. Hu Shih (1891–1962) wrote a long preface to this edition, which contributed the first biographical study of the author Liu E as well as the first comprehensive literary critique of the novel (aside from Lu Xun's well-known but brief mention in his A Brief History of Chinese Fiction 中國小說史略 which was completed a little bit earlier but officially published in the same year). Towards the end of this preface, Hu Shih curiously diverged from the novel itself and started harshly satirising a “fake edition” he had seen in the market. This edition, Hu Shih reported, was “published in 1919” and it claimed to be a “complete edition” consisting of two volumes: volume one of the usual The Travels in twenty chapters, and volume two a “fake sequel” with the same number of chapters. Quoting at length from the “fake sequel” a scenery description that was written in the hackneyed and formulaic style of classical Chinese, this most radical advocate of the vernacular literature furiously ended his preface:

My dear readers, have you ever seen any scenery description from the first twenty chapters of The Travels that is as ugly as this? Aren't these impudent fraudsters overtly insulting Mr Liu E? Aren't they overtly insulting the readers of our society?Footnote 7

The way Hu Shih ended his essay leads us to ponder on a number of quandaries. What was that “fake edition” like? Who produced it and for what purpose? And, most curiously, why was Hu Shih so furious about it? The making of fake sequels is nothing new in the Chinese fictional tradition. For a popular text like The Travels, and in a period of a flourishing print industry not yet well regulated by the notion of intellectual property, to encounter one or more forged sequels was only natural. Serious scholars and writers were well aware of these kinds of cheap commercial tricks, and they would normally not even bother to direct a glance in their direction. It is thus hard to imagine that Hu Shih, with his well-known reputation of being a modest gentleman, would overreact in this manner. The answer to these questions would thus depend on locating this edition, reading it, and studying its own textual history. As the investigations below will show, this mysterious “fake edition” played a surprisingly important role in the early reception history of The Travels, and its significance in revealing the complexity of the text can hardly be exaggerated.

The “fake sequel”

What is the “fake edition” like? There is no straightforward answer that we might hope to look up and cite from a standard encyclopedia of Chinese literature. In fact, we probably would not have known of the existence of this edition were it not for Hu Shih's authoritative and enduringly influential preface. But Hu Shih revealed in his essay very little bibliographical information about the “fake edition”. He only mentioned that it was published in 1919 (which is incorrect, as will be shown) and that it had forty chapters. No publisher's name was given. He also mentioned en passant the names of two authors of prefatory materials to the text, Qian Qiyou 錢啟猷 and Fu Youpu of Jiaozhou 膠州傅幼圃, but only in a parenthetic note in a different portion of the essay. Neither of the names leads to any celebrities that might be easily identified. The story of this “fake sequel” might thus have led to a dead end, but for the testimony from Liu E's fourth son Liu Dashen fourteen years later, which would solve the mystery and reveal the incredible secret behind the making of this “fake edition”.

In 1939, Liu Dashen published a memoir “About The Travels of Lao Can” (Guanyu Lao Can youji 關於老殘遊記, hereafter “About The Travels”) in the inaugural issue of the Wenyuan 文苑, a journal of the Fu Jen Catholic University.Footnote 8 Previously, other descendants of Liu E had spoken in public about what they knew about Liu E and The Travels, but this memoir from Liu Dashen, who had spent much time with Liu E and had witnessed many important incidents in his father's life, would prove to be the most detailed and comprehensive report.Footnote 9 In this memoir, Liu Dashen recollected five different kinds of “imitated editions” (fangzuo 仿作) he had heard of or witnessed in different places (which is also circumstantial evidence for The Travel's national popularity): one in Hankou, two in Tianjin, and two in Shanghai. He had no interest in making further comments on them, because “they were all absurd and sordid in their wording. Anyone seeing them would immediately know they are fake, and it would be worthless to denounce them.”Footnote 10 But he made an exception for one of the editions produced in Shanghai and spent quite some time detailing the story behind the making of it. The story is so telling that it is worthy of being cited at length:

A publisher in Shanghai also made an “imitated edition” and it was entitled A Sequel to The Travels of Lao Can. They had posted advertisements for presale before the book was published. I saw the ad and inquired about it. It turned out that the publisher had no idea about the existence of the authentic Sequel, and I was surprised to know that the book they were advertising was but a fan fiction. Because of my inquiry, the manager visited me to make an explanation and also stated the difficult situation they were facing: they had already accepted many pre-orders. The advertisement cost was huge and they would not be able to afford the loss if the project was now terminated. If this really happened, the stockholders of the company would be accusing him, the manager, and he would have no way out. He apologized many times and suggested that they would love to pay rich compensation if I could give them the real Sequel for publication. I replied that I couldn't make this decision alone without asking others in the family. However, considering that it was not reasonable to forbid others from making a sequel, and that it was indeed a difficult situation for them, I dictated terms to the manager: their book could not be published in the name of Hongdu Bailiansheng; they could not use words like “erbian” 二編 (sequel)” or “erji” 二集 (the continuation) in the title; I need to review the manuscript when it was ready, and I would give my consent only if it did not harm my father's reputation. The manager agreed to all these terms.

Later the manager visited me again, saying that they had invited the notable Mr Fu of Jiaozhou to serve as the chief editor. After many discussions, Mr Fu still thought that it would be better if he could borrow the authentic Sequel to read, so that the new edition would not diverge too much. I responded that this would not happen, but I could share with them the brief life history of my late father. After a while this manager visited me for the third time, asking to borrow the original Tianjin Daily News edition of the first twenty chapters for the purpose of text emendation. I agreed because it was indeed the case that the existing editions on the market all had too many errors and mistakes.

The new edition came out, and at that time my late second older brother Dafu 大黼 (style name Yizhong 扆仲) happened to be visiting from Suzhou. Hearing about this edition, he also went to question them, and they made an explanation to him too. After confirming this with me, he decided not to pursue the matter. Several days later, the manager sent us twenty copies of the newly printed The Travels as well as twenty copies of their new sequel. They also suggested making recompense. We kept the books but refused the money. My brother later brought these books to Suzhou.

In the sequel authored by Mr Fu, there are episodes like Lao Can touring the Doulao Palace of Mt. Tai 泰山斗姥宮, debating the principles of the three teachings, visiting Beiping and Xi'an, and founding the textile factory. The manager had heard about my father's general life history from me, but without many details. Therefore, these episodes somehow allude to my father's actual experiences, but only in a vague way. After several years, I was working in the Beijing-Tianjin area. I saw an essay by Mr Fu published in the Xinyu fukan 新語副刊 (Supplement to the New Words) of Qingdao, in which he confessed about the forging of the sequel, and made apologies to the original work. Because of this, my brother and I came to admire Mr Fu's honesty and courage.Footnote 11

This testimony answers all the curiosity we have about Hu Shih's preface. Apparently, the “Mr Fu of Jiaozhou” in this memoir is the same person as “Fu Youpu of Jiaozhou” in Hu Shih's preface, and this two-volume edition, produced with the assistance of Liu Dashen, is precisely the “fake edition” that Hu Shih condemned. The story is illuminating in many regards, and we will revisit it frequently in the rest of this exploratory journey. But before we continue, the “fake edition” that has been kept in suspense deserves a formal and direct presentation. Thanks to the clues from Hu Shih and the revelation from Liu Dashen, we have been able to excavate this edition produced by some Shanghai Baixin Company 百新公司 from the dusty corners of the repertory of Chinese books.Footnote 12 (See Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4.)

Figure 1. The Baixin edition: cover of the first volume (the original twenty chapters). Source: Courtesy of the C. V. Starr East Asian Library, University of California, Berkeley. Photo prepared by Dr Jianye He.

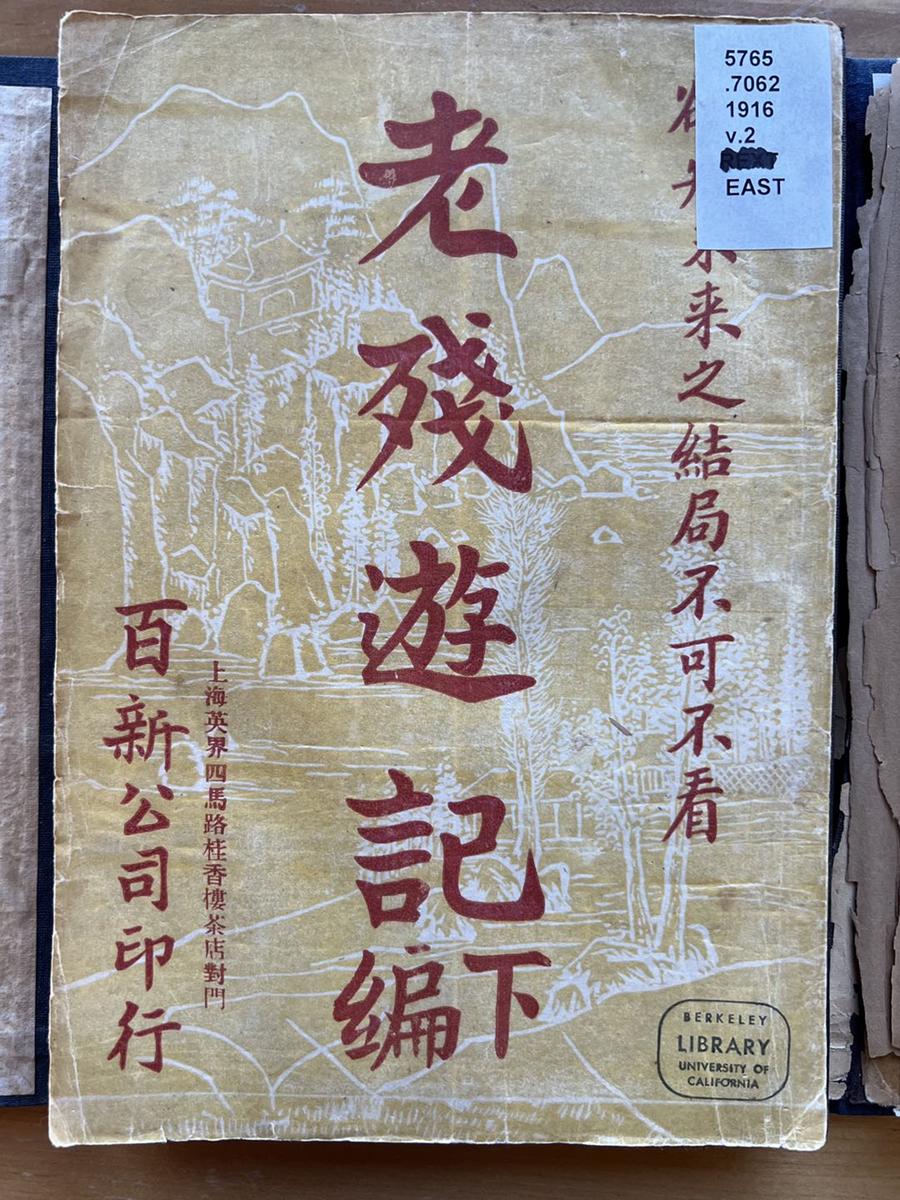

Figure 2. The Baixin edition: cover of the second volume (the “fake sequel”). Source: Courtesy of the C. V. Starr East Asian Library, University of California, Berkeley. Photo prepared by Dr Jianye He.

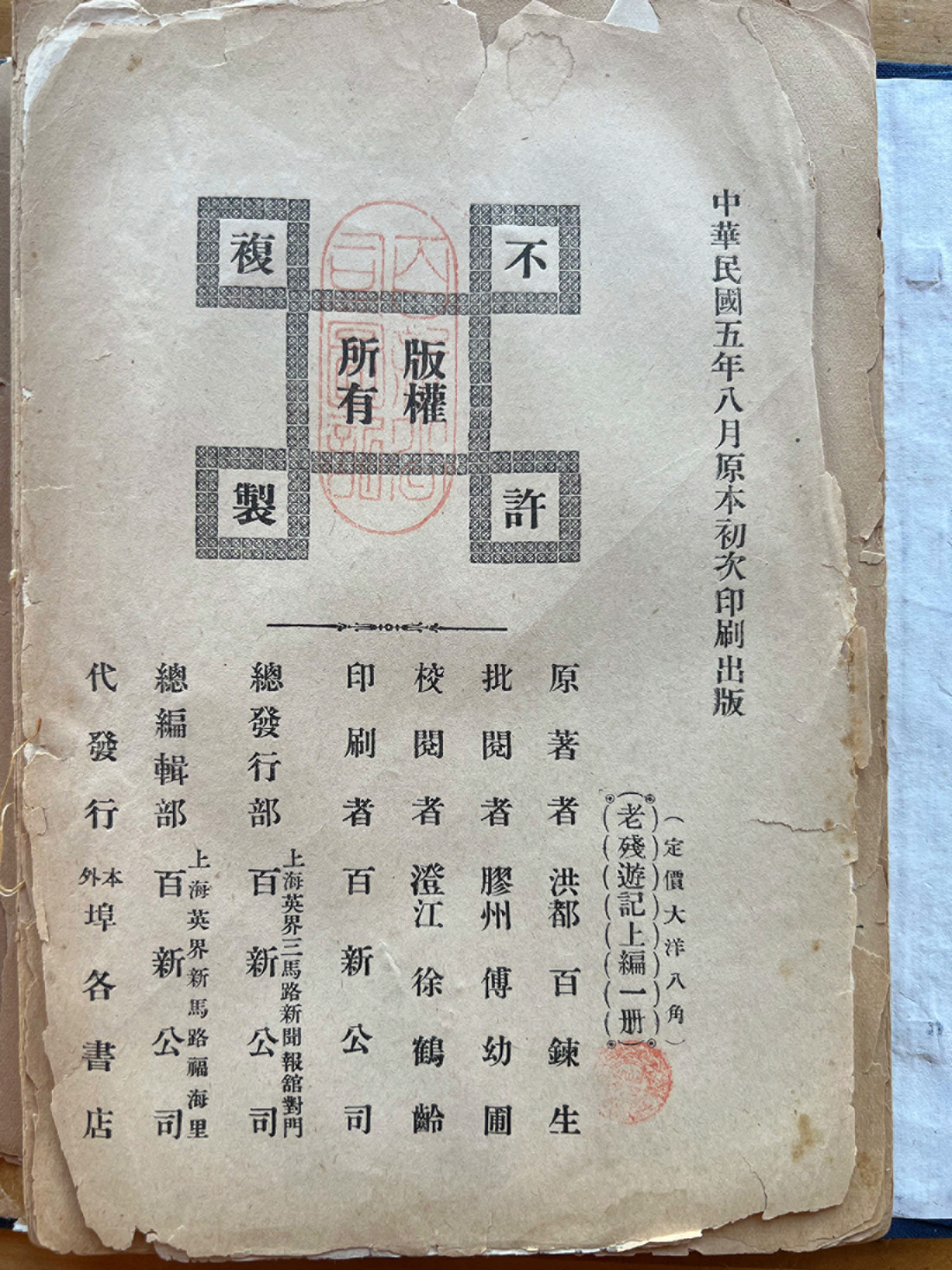

Figure 3. The Baixin edition: colophon of the first volume. Source: Courtesy of the C. V. Starr East Asian Library, University of California, Berkeley. Photo prepared by Dr Jianye He.

Figure 4. The Baixin edition: colophon of the second volume. Source: Courtesy of the C. V. Starr East Asian Library, University of California, Berkeley. Photo prepared by Dr Jianye He.

The “fake edition” (which I will term the “Baixin edition” hereafter) was first published in 1916. (Apparently, Hu Shih has misremembered the date, or what he saw was a 1919 reprint.) It comes in two volumes, and both cover pages have the title, the name of the publisher, and its address. On the right side of the first volume's cover, a line of characters reads: “Carefully collated based on the original edition; no missing parts; with commentaries and notes added”. On the left side characters in smaller size read: “Different from the lithographic copies; buyers and readers please take note”. This is no commercial gimmick. As Liu Dashen has attested to in the memoir, the Baixin Company indeed had the original Tianjin Daily News edition as the master copy, which allowed them to differentiate this moveable-typed product from the existing “lithographic copies” that — in Liu Dashen's words — “had too many errors and mistakes”. On the cover of the second volume, a line of characters reads “You cannot afford not reading this book should you want to know what is going to happen in the future.” This is appropriate for a sequel that tells the “future” of the original story. But as will be discussed soon, this expression can also be interpreted as an emphasis on the prophetic power of the book. The colophon of the first volume reads: “August of 1916. First edition. First print. Author: Hongdu Bailiansheng. Commentator: Fu Youpu of Jiaozhou”. The second volume's colophon contains mostly the same information, except that it designates the authorship to a “Qianren” 前人 (forerunner), while the real author of the sequel, Fu Youpu, remains a “commentator”. In this way, the Baixin Company managed to abide by Liu's term, i.e. not to publish the sequel under his father's name, yet the literal meaning of the vague “Qianren” could also be interpreted as “the one as before”, misleading the readers into believing that the two volumes had the same author. Indeed, this abidance was merely expedient. In some later reprints, Liu E (instead of Hongdu Bailiansheng or “Qianren”) was explicitly presented as the sole author of all forty chapters. A lithographic copy of Liu E's handwritten manuscript of the original preface to The Travels is also included in the preliminaries. The Baixin Company probably also obtained this copy from Liu Dashen, which further strengthened the “authenticity” of its product. Besides, each volume is also accompanied by a new preface: “Thoughts after Reading The Travels of Lao Can” 讀老殘遊記感言 by Qian Qiyou of Chengjiang 澄江 in the first volume and “Preface to the Second Volume” 下編序 by Fu Youpu, of which more later.

Where the novel proper begins, the printing switches from lithography to moveable type — a technology that was more expensive and desirable in that period. Like most traditional Chinese novels, on each page there is a designated header for commentaries. At the end of each of the first seventeen chapters, there are also chapter commentaries attached. Fu Youpu as the “commentator” apparently took credit for all the commentaries. But as a matter of fact, these seventeen pieces of chapter commentaries were penned by Liu E himself. They were included in the original Tianjin Daily News serialisation but were omitted in most of the later book editions because people did not know they were also Liu E's writing.Footnote 13 This proves that the Baixin Company people had indeed rigorously studied the original edition that they borrowed from Liu Dashen. The chapter commentaries resume in the second volume, and these are obviously written by Fu Youpu. He left the last three chapters of the first volume blank instead of filling the gap with his brush pen, which was probably his way of showing some respect for Liu E.

Surveying the basics of the Baixin edition leads to an unexpected conclusion: if we leave the “fake sequel” aside and just consider the first volume, it was actually a very high-quality production. It was well collated and punctuated based on the best available source text. It restored the chapter commentaries that were missing in other circulated editions. It had newly added header commentaries that required extra investment. For the novel proper it used moveable type printing that was neater and more expensive, but for the preliminaries it used lithography so as to retain the feel of the author's own handwriting. Considering these facts, this edition, when it first came out in 1916, was probably the best edition of The Travels on the market.

The high quality of this meticulously produced edition leads to another surprising yet quite understandable fact: it sold very well and garnered a very wide circulation. As a result, to a great extent, this edition shaped the popular perception of what The Travels should be like, and it might have even overshadowed the true twenty-chapter editions. To precisely quantify the popularity of this edition is not easy, not only because we lack the necessary statistics for the general book market, but also because of the deliberate censorship it received, which had left no room for it in the later projects of preserving and studying twentieth-century Chinese literature. However, various clues about the circulation of the Baixin edition may still be traced and, when put together, they give us a quite clear picture of its popularity.

The first evidence comes precisely from the 1925 Yadong Library edition that Hu Shih prefaced. In the “Notes on the Collation” 校讀後記, Wang Yuanfang 汪原放 (1897–1980), the famous editor who was responsible for the production of this edition, introduced the existing editions of The Travels he had studied. He wrote:

It is indeed very hard to find a good edition of The Travels of Lao Can, although it is a recent work. Very few of the existing editions are reliable and with fewer errors. There are two kinds of commonly seen editions. One is the twenty-chapter edition, and the other the forty-chapter edition. Hu Shih in his preface has showed the evidence proving that the forty-chapter edition is a forgery. Thus my punctuation has of course relied on the twenty-chapter edition.Footnote 14

This highly technical and routine introduction is very easily overlooked. Yet it is precisely in this paragraph that the clue we are looking for is hiding. According to Wang Yuanfang, the “forty-chapter edition” (which now we know means the Baixin edition) was highly visible on the market by 1925 as one of the “two kinds of commonly seen editions”. What is more, it seems that nobody — including the renowned editor Wang Yuanfang himself — had ever doubted its authenticity until Hu Shih pointed it out.

The second piece of evidence is somewhat circumstantial. According to the 1985 “Bibliography of the Historical Editions of The Travels of Lao Can” (hereafter “Bibliography”), eight different publishers, including the Commercial Press and the Tianjin Daily News, had produced their own book editions of The Travels between 1907 and 1915, which reflects the highly competitive nature of the market. But ever since the launch of the Baixin edition in 1916, the number of the competitors dramatically dropped. In the ten years between 1916 and 1925 (in which year the Yadong Library launched its own authoritative edition), only two publishers produced new editions (Shanghai Taidong Books 上海泰東書局 in 1922 and Jingzhi Books 競智書局 in 1924).Footnote 15 Although other factors might have been at play, it seems very plausible that the Baixin edition had marketed itself so well that the other publishers thought it was not worthwhile to join in the competition, and that in 1925 a serious scholar like Hu Shih would feel it urgently necessary to promote an authentic edition to eliminate the ill effects of the fake one.

But the most convincing evidence comes from the lasting proliferation of the Baixin edition itself. By 1923, the 1916 edition was at its nineteenth reprint.Footnote 16 According to the aforementioned “Bibliography”, two derivative editions were released in 1924, probably to fulfil the needs of different readerships. The A edition, with commentaries (jiazhong pizhu 甲種批註), was designed for the readers nostalgic for the traditional book format. In comparison, the B edition, with new style punctuation (yizhong xinshi biaodian 乙種新式標點), aimed to please the younger generation who had a preference for modern book layouts. The B edition had its third reprint in 1925. In 1928, a C edition in four volumes was also produced.Footnote 17 From other sources, I have also come across several surviving Baixin copies: a 1931 B edition (the tenth reprint), a 1934 A edition (the twenty-sixth reprint), and a 1937 A edition (the twenty-ninth reprint).Footnote 18 These numbers are stunning, because to our knowledge no other edition of The Travels has been reprinted more than ten times (in fact, most of them only have one or two reprints). This shows just how popular the Baixin edition was. Even after Hu Shih's imprecations of 1925, the Baixin edition continued to thrive on the market.

In this light, we finally understand why Hu Shih was so furious in 1925. He was not making a fuss about some cheap commercial gimmickry. Quite the opposite — he was battling against, arguably, the most popular and influential edition of The Travels, one that had greatly shaped what kind of book The Travels was understood to be. We need then to ask what The Travels had become as represented by the Baixin edition? How did it violate Hu Shih's understanding of it? To be sure, the formulaic description of scenery in classical language was what Hu Shih disliked. But as they appeared in Hu Shih's preface, they only served as evidence for forgery because they did not match the style in the first twenty chapters. What really upset Hu Shih was something far more fundamental: the fact that the edition amplified and valorised a long-standing interpretation of The Travels as a book of prophecy. We will read the actual contents of the Baixin edition soon, but before that, we need to review where the “prophecy” was from and what exactly it foretold.

The prophecy

Ever since its initial serialisation, The Travels was read by many as a mysterious prophecy that materialised the superior wisdom of the Chinese occult tradition, mainly thanks to the revelations made in the famous Peach Blossom Mountain episode from Chapters eight to eleven. In this episode, the young man Shen Ziping 申子平 is sent to the Peach Blossom Mountain by his cousin Shen Dongzao 申東造 with the mission to pay a visit to the chivalrous figure Liu Renfu 劉仁甫, whom Lao Can has recommended to take charge of the local security under Shen Dongzao's jurisdiction. Before seeing Liu Renfu, Shen Ziping is lost in the mountain and encounters two mysterious figures, the young lady Yugu 璵姑 and the elder hermit-sage Yellow Dragon (Huang Longzi 黃龍子). In a long conversation between them, Yellow Dragon reveals to Shen Ziping the “sanyuan jia-zi” 三元甲子 (roughly translated: three fatal points of the sexagesimal circles) theory. Invoking Chinese numerological and astrologic terms, Yellow Dragon explains that the year 1864 (a jia-zi 甲子 year by the traditional Chinese calendric reckoning of Heavenly Stem and Earthly Branches) was the “first fatal point” (shangyuan jia-zi 上元甲子, also called the “pivotal point” or zhuanguan jia-zi 轉關甲子) that marked the beginning of a new and chaotic sixty-year circle. All the major political incidents to date (sometime between 1895 and 1898 in the story's setting), according to Yellow Dragon, were all predetermined in light of this theory, including the death of the Tongzhi emperor (1874, the jia-xu 甲戌 year), the Sino-French War (1883–1885, around the jia-shen 甲申 year 1884), and the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895, which broke out in the jia-wu 甲午 year 1894). Responding to Shen Ziping's question about the future, Yellow Dragon reveals what the rest of this pivotal circle would be like:

They will be just as I have said: Boxers in the north, revolution in the south (beiquan nan'ge 北拳南革). Preparations for the Boxer outbreak in the north began in wu-zi 戊子 (1888) and were already mature by jia-wu 甲午 (1894). In geng-zi 庚子 (1900) zi 子 (rat) and wu 午 (horse) will clash with a great explosion. Their rise will be sudden, their fall equally abrupt. They are “the political force in the north.” […] Preparations for the southern revolution, begun in wu-xu 戊戌 (1898), will mature by jia-chen 甲辰 (1904). In geng-xu 庚戌 (1910), chen 辰 (dragon) and xu 戌 (dog) will clash with a great explosion. Their rise will be gradual, their decline equally unnoticed. They are “the political force in the south.” […] These two rebellious parties will both brew disaster, but together they will open up a new era. The Boxers in the north will gradually make inevitable the political changes of jia-chen 甲辰 (1904); the southern revolution will gradually make inevitable the political changes of jia-yin 甲寅 (1914). After jia-yin there will be great cultural developments.

Yellow Dragon persists in elaborating a series of complicated causative relations that seem impossible to be understood by our worldly minds, and then he casts a rather optimistic end of this pivotal sixty-year circle that these complex dynamics would ultimately lead to:

After jia-yin will be a time of cultural florescence, but although brilliant to look upon, still it will not equal the development of other countries. Jia-zi 甲子 (1924) will be a time of a real independent cultural harvest. After that the introduction of new culture from Europe will revivify our ancient culture of the Three Rulers and Five Emperors, and very rapidly we shall achieve a universal culture. But these things are still far off, not less than thirty or fifty years.Footnote 19

To be fair, prophetic discourses are common in the premodern Chinese literary tradition (especially among the zhiguai 志怪 writings), but they could become controversial in that time of great intellectual change and clash of values. In fact, the Peach Blossom Mountain episode was precisely what upset the Commercial Press during the initial serialisation. The Commercial Press took the liberty to delete much of the content and reframed the episode as a dream that Shen Ziping has had, because, they stated: “Now it is the period of banishing superstitions. People in our society ought not to talk about absurdities anymore.”Footnote 20 This impudent censorship infuriated the author's side and led to the termination of the serialisation, as mentioned earlier. In the wake of the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, however, many readers realised that the two nearest “futures” foretold by Yellow Dragon, “Boxers in the north and revolution in the south”, had both been almost perfectly “fulfilled” by the actual historical process in the past decade: the Boxer Rebellion indeed broke out in the north in 1899 and reached its climax in 1900 (the geng-zi year), and the great revolution that had just happened took place only one year later than the prediction. Liu Dashen observed that this “fulfilment” of prophecy led to a rapid increase in the number of the unauthorized copies of The Travels on the market in the early years of the Republican period.Footnote 21 The renowned scholar Hu Huaichen 胡懷琛 (1886–1938) also noted: “The book was not very well-known in the beginning. But its pronouncements on beiquan nan'ge were taken as prophecies by many in the wake of the Republic era. […] For this reason, people scrambled for it, and it became very widely circulated.”Footnote 22 These observations are in accord with the history of editions reviewed above. For the publishers competing to sell their own editions, the otherwise obscure expression “beiquan nan'ge” became an indispensable marketing slogan. Now even the Commercial Press, which in 1904 practised censorship against such “superstitions”, was using this slogan to advertise its edition of The Travels in 1919.Footnote 23

Readers today with knowledge of the book's textual history would easily notice the little chronological sleight of hand that Liu E was playing: the book was actually written and published between 1903 and 1906, when the Boxer Rebellion had already ended and a series of minor revolutionary revolts had been going on in the southern provinces. Why Liu E played this trick is not a necessary question for today's readers, for whom it has become common sense that fiction has no responsibility to faithfully report the facts. We can also argue that this little trick reflects Liu E's painstaking effort to bring hope to his fellow citizens in a chaotic era: if the Boxer Rebellion as “foretold” had come true, so would the bright future of a “universal culture” by the end of the 60-year circle. Yet, readers in that period apparently had different interpretations of this episode. Progressive intellectuals condemned it as superstition, just like the Commercial Press had before. For example, Qian Xuantong 錢玄同 (1887–1939) in 1917 wrote in La Jeunesse 新青年 that those predictions were “opinions from a muddled head of an ‘old new fellow’” and that “Yellow Dragon's words on ‘beiquan nan'ge’ are nonsense that only makes one burst into laughter.”Footnote 24 By this time Qian Xuantong already knew the author's real identity (and probably also the textual history of the book), which was rare knowledge in the elite circle.Footnote 25 However, for the general readers who had no access to such knowledge and who were deeply influenced by the traditional Chinese culture that always had an occult dimension, this mesmerising “sanyuan jia-zi” theory and its “success” in “foreseeing” the beiquan nan'ge were undeniable evidence attesting to the efficacy of The Travels as a book of prophecy.

Two anecdotes reported by Liu Dashen in a note to his 1939 memoir are especially illuminating in this light. These anecdotes were removed from records in the Socialist era, which was apparently a result of censorship aimed at repressing the “superstitious” memories of the book. It is worthwhile to restore this note below in its complete form.

Seventy or eighty per cent of the general readers have some occult ideas in their minds, and for that reason bizarre and uncanny discourses are everywhere. Below is what I have personally experienced. In the winter of 1913, I was travelling from Suzhou to Huai'an 淮安. In the cabin of a small ferry on the southern canal, I met a traveller Mr Zhang who was reading The Travels of Lao Can. He asked me whether I had read it, and then talked to people around us: “The person who wrote this book is indeed extraordinary. He knew the world would become catastrophic in the future, so he got one wife, had some children, and bought some properties in each of the eighteen provinces of China, so that some of his descendants would survive the catastrophe. I once paid a visit to him through the offices of someone's introduction. I begged to become his disciple, but he refused me.” Et cetera.

Another experience: in the May of 1917, I took a train ride from Shanghai to Zhangde 彰德 on the Ping-Han 平漢 line. There was an old man Mr Yu on the same train and we started chatting. He talked about himself: “I have been learning the Way in Mt. Emei 峨眉. My master is a monk named Zhiyuan 智元. Now I am ordered by my master to leave the mountain and to help the world. Many years ago, a senior fellow disciple of mine, Lao Can, had left the mountain for the same purpose. He could tell the past and the future. He is still travelling everywhere, and he has written a book called The Travels of Lao Can.” Et cetera.

Those two did not know that my father had passed away for many years, nor did they know who I was. As I heard this kind of ridiculous language and their thoughts about my father's work, I really did not know whether to laugh or to cry. To be sure, I could not agree with them any less, but I also had no idea how to refute them. Besides these two, many others — even those who are comparatively better educated — also speak about or write similar absurdities. They are just not as outrageous as these two.Footnote 26

It takes a lot of imagination to fill the gaps between The Travels as we know it and the “eighteen wives” and the “master Zhiyuan of Mt. Emei”. But we must stay humble in the face of the vitality and productivity of popular discourses: how they deviate, intermediate, transform, and proliferate. As Liu Dashen hopelessly stated in the end, “absurdities” about The Travels was a common discourse, not an occasional one. To fully capture how “absurd” Lao Can's story had become in this discourse is hard for the lack of further documentation. What we do have, however, is the Baixin edition that has survived a century's repression and neglect. Our reading of this edition below shows it played a significant role in the valorisation of The Travels' early reception as a book of prophecy. Its commercial success came from its manipulation of the existing discourse about the efficacy of the book. In turn, the high quality and wide circulation of this edition reinforced this discourse.

Reading the Baixin edition

Earlier we had a taste of the high quality of the design and presentation of the Baixin edition. Now we turn to its contents. The Baixin Company added three kinds of new contents that distinguished this product from any existing editions: prefaces by Qian Qiyou and Fu Youpu, the header commentaries on the first twenty chapters, and the entire “fake sequel” (which also includes its own commentaries). All of these materials explicitly highlight the prophetic power of the book.

The preface entitled “Thoughts on Reading The Travels of Lao Can” is placed at the beginning of the first volume. It is dated in 1916 and signed by a certain “Study Committee Member Qian Qiyou of Chengjiang 學務委員澄江錢啟猷”. What exactly the “Study Committee” means is not clear, but the lack of a modifier might easily create the impression that it is something significant at the national level. In fact, however, it belongs to a local school in Chengjiang of the Yunnan Province. As the text of the preface reveals, Qian Qiyou was an employee of that school and he had just come to Shanghai during the summer break to buy books for the school. Hearing that the Baixin Company had recently published an annotated edition of The Travels in two volumes, he eagerly purchased it and found out that this edition was different in many ways from The Travels he had read before. Disappointed, he blamed the company for making an edition full of mistakes. The manager of the company, Mr Xu, addressed his complaints: “This is but a misunderstanding, and these are not mistakes.” He took out two volumes of manuscripts, saying: “These are the original handwritten manuscripts of Hongdu Bailiansheng. I spent years looking for them. Finally, I obtained them from the author's descendants. I persuaded them to give me the consent to publish the manuscripts, so that they will perpetually exist in the world.” Accepting this edition as authentic, Qian Qiyou then started commenting on the contribution of the Baixin edition in revealing the full value of The Travels that was otherwise incomplete:

The Travels of Lao Can is so popular in China and abroad because it reveals the timing of prosperity and catastrophe, and it foresees the alternations of rise and downfall. It grasps the historiographical sophistication, which is accompanied by the divinatory power of the graphs from The Classic of Changes (Yi Jing 易經). Once the book is split [like it was before the Baixin edition], the meanings of the words become obscure and tasteless.Footnote 27

Here Qian Qiyou explicitly declared the prophetic nature of The Travels by juxtaposing it with The Classic of Changes, one of the earliest Confucian classics and the most canonical text in the Chinese occult tradition. Indeed, The Classic of Changes is an important reference in The Travels. For example, in the Peach Blossom Mountain episode, Yellow Dragon invokes the “ze-huo-ge” 澤火革 hexagram from The Classic of Changes to interpret the meanings of the character “ge” in the “beiquan-nan'ge” prophecy.Footnote 28 This is not to say that any reference to The Classic of Changes is a gesture of occultism. As one of the “four books and five classics”, this work has deeply influenced the Chinese intellectuals’ ways of thinking, speaking, and writing. Yet, intellectuals (as opposed to grassroots occultists and their followers) usually use this book as a repository of philosophical wisdom instead of as a tool for divination. For example, many progressive modern thinkers have used the rhetoric in The Classic of Changes to justify their advocacy for reforming the country and learning from the West.Footnote 29 Qian Qiyou's discourse here, by contrast, is to single out the “divinatory power” of The Classic of Changes, and to transplant the same power to The Travels as a strategy of corroborating the occult appeals of the book to the general readers.

Qian Qiyou was certainly a participant in this “fake sequel” hoax, despite his innocent tone in the narrative. The sticking point is the timing. This preface appeared in the 1916 first edition. There was no earlier edition for him to have purchased and to feel disappointed in before he wrote the preface. Apparently, for the Baixin Company a good way to dispel people's doubt about the authenticity of its product was to give testimony from a suspicious reader, who was not only convinced after viewing the original manuscripts, but also enlightened by the full efficacy of the “complete” edition. Hence the story in the preface. This also explains why we found it hard to identify who exactly this Qian Qiyou was. For a meticulously prepared book, it was strange that the publisher did not follow common practice and invite a celebrity to preface it. The manager “Mr Xu” was very likely to have been the same person as the “proof-reader Xu Heling of Chengjiang” 澄江徐鶴齡 as shown on the colophon pages. If this is true, Qian Qiyou must have been someone from the manager's hometown (they were both from Chengjiang) who was asked to help effect the hoax — if this person indeed actually existed.

We turn to the second preface, which is placed at the beginning of the second volume. It is attributed to the “commentator Fu Youpu”, who we now know is the real author of this volume. I translate his preface below in full, not only because it much more dramatically advertises the occult power of The Travels, but also because its revelation of the unusual textual history (which we now know is fake) makes for an interesting conflict with Liu Dashen's recollection of the same matter that we have read earlier.

The Travels of Lao Can authored by Hongdu Bailiansheng was initially revealed and serialised in the Tianjin Daily News. It was hailed by the readers as soon as it was launched, causing a sensation in the book market. What a joy this marvellous writing has brought to the readers, and many of them have eulogized it in different venues. Its popularity keeps growing these years, and it has circulated around the globe.

A special merit of this book, aside from its literary strength that entertains the true connoisseurs, is that it helps with people's inquiries into the world. I used to have an unworthy career in Tianjin, and by chance I got the first volume of the book. Carefully studying it, I realised that hidden in the story's narratives was the exquisite efficacy in divination and prophecy, which was even more precise than the numerological books such as the Tuibeitu 推背圖 (Back Pushing Diagrams) and the Shaobingge 燒餅歌 (Baked Bun Rhymes). It was so marvellous that I could not help but slap the reading desk. I then carefully wrote commentaries on it in my spare time, but I always felt regretful for not having seen the book in its complete form.

In 1912, I came to Shanghai and began a friendship with Mr Xu, the manager of the Baixin Company. In our conversation I mentioned this book and my regret of not having seen the complete work. Mr Xu said in laughter: “My company has obtained the original manuscript in two volumes. The first volume is already circulated widely in China and abroad. As to the second volume, we were planning to publish it. However, it happened to be the wartime between the north and the south. We were afraid that those in power would consult this book for their own political interests, so we did not dare to hastily put the manuscript into the hands of the typesetters.”

I requested the manuscript and read it through. The records in it were elaborate and the divinatory methods were delicate, making it an adequate reference for the future. Opening each chapter, one cannot bear to move on to the next. Appreciating each section, one tastes a special flavour. Out of this enchanting pleasure of reading I again penned commentaries on this volume. I urge Mr Xu to publish it in order to fulfil the wishes of all book lovers. This piece humbly serves as the preface.

Fu Youpu of Jiaozhou in his temporary Shanghai residence, on the fifteenth day of the Jiaping month, 1912.Footnote 30

This preface was curiously “dated” 2 February 1912 (converted to the Gregorian calendar), leaving quite a big four-year gap between it and the final release of the book from the publisher. The purpose of this subterfuge is not easy to be discerned from the preface itself, but a reasonable explanation might be deduced from the “prophecies” made in the “fake sequel”. As we will soon learn, the “fake sequel” correctly “prophesied” many incidents after 1912, including Yuan Shikai's 袁世凱 (1859–1916) 1915 revival of the monarchy. Expecting that people might question the credibility of the prophecies (since they were published after the incidents had happened), dating the preface before those prophesied incidents was obviously a good way of forestalling any such doubts. In this regard, the intentional mention of the manager Mr Xu's postponing of the publication was also a brilliant move. It not only highlighted the power of the book in actual political life, but also set up in advance a convenient excuse for the four-year gap: if Mr Xu had been postponing the publication of the manuscript up to 1912 in order to prevent it from being appropriated by “those in power”, then he may well have chosen to postpone it for another four years for the same reason.

As clever as the trick was, it still left one (and probably the only one) internal blemish that undermined the credibility of the preface (as opposed to the external evidence that is Liu Dashen's testimony). To nail down the prophetic nature of The Travels, Fu Youpu wrote it was “even more precise than the numerological books such as the Tuibeitu and the Shaobingge”. At first sight this is another brilliant marketing strategy. While Qian Qiyou related The Travels to The Classic of Changes, the most canonical text in the occult tradition, Fu Youpu made the connection to the less authoritative but much more user-friendly texts that were associated with this tradition. The Tuibeitu is reputedly the work of the Tang dynasty occultists Li Chunfeng 李淳風 and Yuan Tian'gang 袁天罡. It contains some sixty (varying from edition to edition) groups of illustrations and poems that hide its secret divinatory messages. Similarly, the Shaobingge is alleged to come from a conversation between the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty Zhu Yuanzhang 朱元璋 (1328–1398) and his trusted counsellor Liu Ji 劉基 (1311–1375), who in this conversation used a series of ciphered rhymes to satisfy Zhu Yuanzhang's curiosity about the future. However, to juxtapose these two titles in 1912, assuming they were popular texts that the readers were all familiar with, would be an anachronistic mistake.

Despite their alleged ancient origins, the actual textual history of the Tuibeitu and the Shaobingge is full of uncertainties and obscurities. Texts of this sort only circulated to a limited degree in manuscript form throughout the Qing dynasty, mainly because the Qing government had rigorous censorship against divinatory inquiries into the rise and fall of a dynasty. The first printed Tuibeitu was not published until 1912, after the Qing had fallen in the previous year. This edition, however, simply presented an old textual corpus which had little relevance to the contemporary world.Footnote 31 What really embodied the prophetic power of the Tuibeitu was a so-called “Jin Shengtan 金聖歎 (1608–1661) annotated version” that was suddenly brought to the market in 1915. Alleged to have been a secret collection in the imperial Forbidden City which was recently declassified with the fall of the dynasty, this version correctly “foretold” many late Qing political incidents. It was published as a part in the book Chinese Prophecies from Two Millennia Ago 中國二千年前之預言 (hereafter Chinese Prophecies), a product of the famous Chunghwa Books 中華書局. In addition to the Tuibeitu, Chinese Prophecies also included the Shaobingge, as well as five other kinds of “ancient” prophetic texts. The book was a huge success and was pirated by many other publishers under the same or similar titles. Interestingly, the Baixin Company was one of these pirates.Footnote 32

In this context, it becomes clear that Fu Youpu could not have invoked the juxtaposition of the Tuibeitu and the Shaobingge as an emblem for efficacious prophetic books if he really had written the preface in 1912. He must have written the preface after 1915 when the release of Chinese Prophecies had already aroused public passion for the ancient prophetic texts and had established the practice of bundling the Tuibeitu and the Shaobingge together as birds of a textual feather. To detect this anachronistic mistake thus not only helps authenticate the dating of the preface, but also reveals that the making of the Baixin edition was not an isolated or accidental case. It was instead a timely response to a larger social undercurrent, that is, a collective anxiety about the future of the nation and a public craze for a prophecy that truthfully reveals the prospect.

We proceed from these preliminaries to the contents that Fu Youpu had painstakingly fabricated. As expected, in the header commentaries on the first volume Fu Youpu singled out the “sanyuan jia-zi” theory that we have introduced earlier. His interpretation was short and concise, but that was not because he lacked interest in this matter. As we will read below, Fu Youpu apparently needed more room than the header could provide and he found the outlet for his talent in the second volume, which was completely his own creation. In his sequel, the protagonist Lao Can continues his adventures and even travels to Japan and Korea. Fairly speaking, the literary quality of the sequel is not as poor as in Hu Shih's assessment. In some regards it even improves upon the original work, such as in the consistency of the storyline. But for our purpose of understanding how the Baixin edition valorises The Travels’ divinatory nature, we need only focus on the most exemplary places where Fu Youpu showed off his talents of fabricating prophecies, rather than assessing his literary skills or the content of the narrative as such.

Similar to the original Travels, Fu Youpu also conveyed his primary prophecies in a series of philosophical conversations taking place in an isolated mountainous place (this time on top of the Mt. Tai). The conversations are between Lao Can, his friend Qingxu 清虛, the monk Puhui 普惠, and the Taoist Yunhe 雲鶴: a narrative setup that responds to the spiritually syncretic inclinations expressed in the original work. The four continue their somewhat pedantic discussions about multiple issues across three chapters (twenty-nine to thirty-one), but the main theme centres around the “heavenly Way” 天道, a universal force that predetermines everything in the world, and how it makes “human efforts” 人力 useless. The monk Puhui is a figure of unfathomable wisdom. Although declaring several times that “the heavenly secrets cannot be revealed” — a hackneyed saying (and often a tantalising trick) in Chinese divinatory practice, he still harangues the others throughout chapter thirty-one to answer questions about the future. The “beiquan nan'ge” prophecy and the “sanyuan jia-zi” theory are again put under the spotlight, and this time they are given full play with more details and threads of reasoning. It is only at this point that we realise how patiently Fu Youpu had been waiting for this moment to prove how considerate a forgery maker he was: this topic was first introduced in the beginning of the eleventh chapter of the original work, and here, too, Fu Youpu resumed the theme in the eleventh chapter of the sequel:

Yunhe smiled: “How about you, my respectable master, just elucidate to us the result of the beiquan nan'ge and the transitions to take place in the future world?” Puhui said: “The destinies can be calculated, but as heavenly secrets they cannot be revealed in advance. Since you (addressing Lao Can) were talking about the alternation of prosperity and turbulence, let me just humbly discuss the Way of the changes.”Footnote 33

The monk Puhui continues his preaching about the correspondence between the heavenly Way and the mundane politics. The theoretical sources he draws upon are multiple. Besides the mysterious “sanyuan jia-zi”, he also invokes yin-yang dualism, five-elements dynamics, the graphic readings of trigrams in The Classic of Changes, and the Confucian human-heaven induction theory 天人感應 made famous by Dong Zhongshu 董仲舒 (179–104 bce). Powered by these old systems of wisdom, Puhui extends his comments on the “current” political tension between the Guangxu Emperor (1871–1908) and the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908) to a series of “future” incidents, including the Hundred Days’ Reform (1898), the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901) (the beiquan), and the revolutionary revolts in the south (the nan'ge). To be sure, these incidents were already “predicted” in Liu E's original work, but Fu Youpu's version is much richer in its provision of details. Moreover, writing a decade later than Liu E allows Fu Youpu to “prophesy” the future of the country with a greater degree of accuracy. Drawing on some complicated calculations in the “sanyuan jia-zi” framework, the monk Puhui reveals, “After [the revolutions] the power of this country will belong to the people, and the titles of all the nobles and officials will be completely changed.”Footnote 34 Lao Can asks if this means the country would become a “democratic state” and that the people would get “equal rights and freedom”. Regarding this, Puhui applies graphic divinations from The Classic of Changes and asserts that there will be no one-off revolution that changes the “four-thousand years of autocracy” for good. Instead, the first leader of the new country will be a “demon-king in the human world” 混世魔王 who rules as a dictator (apparently alluding to Yuan Shikai). The real catastrophe then begins:

[He] will incur several new revolutionary revolts against his dictatorship. With power in hand, the leader will certainly suppress these revolts with military force. Being defeated, the revolutionaries will have no better option than to plan assassinations and terrorist actions. Without prioritising the country's greater good, they will look for such chances day after day, and even draw support from the foreigners at the expense of harming the interest of their own country. In this quagmire situation the leader will decide to change the new regime back to the old and claim the restored throne by himself, in hopes of passing down the power to his descendants, and by doing so, draining the hope of the revolutionaries. This deed will again give rise to many armed revolts. It is of course the leader's selfishness to blame, but it is also predetermined by heavenly calculation. The leader does not understand that he was able to usher in a new era not only because he was chosen by the heaven, but also because he complied with the aspirations of the people. That's why he could overturn the Qing dynasty at one stroke. Now that he wants to take the country as his private belonging, who would be willing to bear with that? Not long after the new monarch is established will the revolutionaries throughout the country be united to fight him. The people will again go through a wave of disasters.

When the demon-king finally vanishes, the world will be renewed. But everything is destitute after all the destructions. A weakened country will be doomed to suffer from foreign insults. Although those in power will try hard, it is worrisome that they are not competent in shouldering such responsibilities. The demons dispersed everywhere will be consistently instigating and causing new clashes. Military conflicts are regular, killings are normal, and the people have no means to live a life. At the same time, some conservatives will rise in rebellion in the name of restoring the Qing regime. […] It will be not until a new pivotal jia-zi that a renewed peace can be expected.”Footnote 35

This pretended “prophecy”, if divested of its future perfect tense, would become a faithful narration of the political world of the early Republican era. Its extraordinary accuracy would shock any reader who believed that the book was written in the previous century. It successfully “foresaw” the founding of the Republic (1912), the Second Revolution (1913), Yuan Shikai's notorious restoration (1915), and the warlords’ dogfights after Yuan Shikai's death. To be sure, this “accuracy” is predicated upon the fact that the sequel was written sometime between 1915 and 1916 after all these incidents had already happened. However, in a surprising way, this paragraph indeed prophesied something that had yet to happen: its words concerning the conservatives’ rebellion in the name of restoring the Qing and China's suffering from foreign insults arguably foresaw the Zhang Xun 張勛 Restoration (1917) and China's failure in the Paris Peace Conference (1919), although the temporal order of the two was reversed. This stunning “efficacy” could perhaps be explained with Hu Shih's rationale regarding Liu E's prediction of a great revolution of 1910 that was almost fulfilled by the Xinhai Revolution in 1911. Hu Shih asserted that what Liu E had done was reasonable speculation based on the contemporary political atmosphere instead of any kind of mysterious prophecy.Footnote 36 Similarly, for Fu Youpu, or for any intellectual with knowledge of the current political world, it was also not hard to speculate on potential reactions from the Qing conservatives and China's awkward situation in international relations.

This rationale, however, was probably too elitist for the general readers, who had used their collective purchasing power to show their endorsement of the Baixin edition. One could easily imagine how amazed the readers were when in 1919 these last two prophecies were fulfilled, and this fulfilment would drive away any suspicion that one might have had about the authenticity of the book. As a result, and ironically, the Baixin edition as a forgery became arguably the most popular and influential edition of The Travels in the early Republican period. The manager Xu Heling and the writer Fu Youpu had proved their rare talent in manipulating the existing text and transforming it into a great commercial success. To be sure, the prophecy was only a very small part in the original novel, and Xu and Fu were also not the first to notice this. But as our above reading has demonstrated, they had seized this most inviting aspect, magnified it, mystified it, and finally established a sense of what the book should be like and how it should be read. In the rest of the Republican period (and even after Hu Shih's 1925 denunciation), the Baixin edition continued proliferating. As we will see in the next section, it was something that one could not detour around when approaching The Travels, no matter whether the purpose was to decipher its hidden secret message or to repress such “superstitions”.

The aftermath

The Baixin edition had a long-lasting influence in the Republican period. The influence was not in the form of standardising the text of the book, as is usually observed in the studies of the history of books. In fact, the sequel made up by Fu Youpu remained a distinguishing feature of the Baixin edition and it was not incorporated into any other later editions. The reasons are not hard to discern: in the beginning it was probably because of the Baixin Company's strong claim over the copyright, as we can see from the colophon pages, and as time went on (especially after Hu Shih's 1925 preface), it was because other publishers were assured that the sequel was a forgery. The Baixin edition's influence on The Travels took the form of shaping how people perceived and remembered the book. It created a certain discourse about the prophetic nature of The Travels, and this discourse kept reverberating in the Republican period.

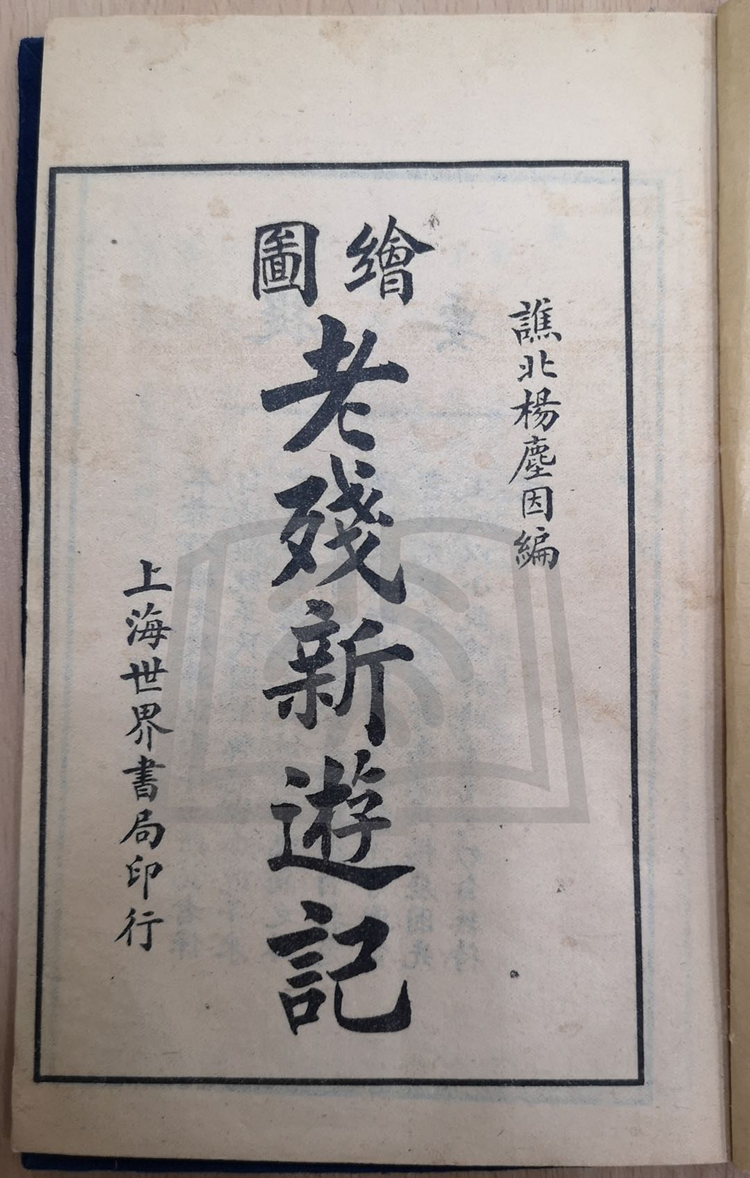

In 1924, World Books 世界書局, one of the biggest presses in Republican China, decided to dip into the market by presenting The Illustrated Travels of Lao Can 繪圖老殘遊記, which was obviously a tactical move to respond the Baixin Company's dominance in the market (Figure 5 and 6). Probably inspired by the Baixin edition, the World Books edition also came with a sequel: The Illustrated New Travels of Lao Can 繪圖老殘新遊記 (Figure 7 and 8).Footnote 37 The difference was that they made it very clear that the sequel was fan fiction authored by the popular writer Yang Chenyin 楊塵因 (1889–1961), despite the misleading fact that the layout and format of the two books are almost identical.Footnote 38 A brief “Synopsis” in the beginning of The Illustrated Travels reads:

[…] This is the number one marvellous book in the modern times. What is especially mystical is the fact that the book was published in the mid Guangxu period (1875–1908), but it prophesied the Boxer Rebellion in the north and the revolutions in the south, as well as all the relevant political incidents thereafter. All these prophecies have been perfectly fulfilled with no exception. It does not become inferior even when compared with the Shaobingge and the Tuibeitu. For this reason, my dear readers, you should not resist reading it immediately and verifying the prophecies with regard to the actual politics.Footnote 39

Figure 5. The Illustrated Travels of Lao Can: title page. Source: Courtesy of Mr Feng Chaohai 馮超海, Shiwai cangshulou 世外藏書樓 (Wuxi, China).

Figure 6. The Illustrated Travels of Lao Can: “Synopsis”. Source: Courtesy of Mr Feng Chaohai 馮超海, Shiwai cangshulou 世外藏書樓 (Wuxi, China).

Figure 7. The Illustrated New Travels of Lao Can: title page. Source: Courtesy of the Peking University Library.

Figure 8. The Illustrated New Travels of Lao Can: colophon. Source: Courtesy of the Peking University Library.

The World Books edition did not make any explicit allusion to the Baixin edition, yet the influence of the latter is obvious. The crucial words in this “Synopsis” are the two book titles the Shaobingge and the Tuibeitu. The bundling of these two books and The Travels, as we have investigated above, was Fu Youpu's invention in his preface to the Baixin edition. The World Books edition was not an exceptional case. In 1934, the Fusheng Newspaper 福生報 reprinted some chapters of The Travels, and an accompanying introduction to the author Liu E read: “The scholarship of Tieyun (Liu E's style name) was profound and extensive. He made the prophecy of ‘beiquan nan'ge’ before the geng-zi year. After the Boxer Rebellion and the Xinhai Revolution really happened, people in the world all took him as a reincarnation of Li Chunfeng.”Footnote 40 Li Chunfeng, as we have introduced, was the Tang dynasty occultist who was believed to be one of the authors of the Tuibeitu. To compare Liu E with Li Chunfeng was thus another way of reinforcing the bundling of the Tuibeitu-Shaobingge and The Travels. And if we believe the credibility of this statement, we would know this bundling not only expressed the newspaper's standpoint, but also reflected the general opinion of the “people in the world”. Indeed, this introduction to Liu E written in 1934 was still full of mistakes, suggesting that the editor of the newspaper had not cared to consult any recent studies on Liu E by the elite literary circles and only wrote the introduction based on popular (but incorrect) discourses.

No matter how anachronistic and ex parte this bundling was, its efficiency was high in reinforcing the status of The Travels in the pantheon of the Chinese occult tradition. It almost became a set phrase and had even appeared in Hu Shih's 1925 preface, though his purpose was to disassemble it. What Hu Shih must have regretted later was that his high profile certainly helped to spread this bundling. Towards the end of the Republican period, the scholar Jiang Yixue 蔣逸雪 (1902–1985) was still writing, in such a way as to apparently appraise Hu Shih's legacy: “There have been two main readings of The Travels of Lao Can. Some people took it as a book comparable to the Tuibeitu and the Shaobingge, because some of the incidents predicted in the book were fulfilled. Some others praised it for its literary merits and said it could be a model text for literary students to learn from.”Footnote 41

These two bifurcated responses to The Travels were both devastated for good in the new Socialist era, a period in which the late Qing and Republican popular fiction in general were hardly endorsed by the new spirit of the time, not to mention the case of The Travels with such “feudalistic and superstitious” contents. More dramatically, its contribution to vernacular literature, which could have garnered it some credit in this new period, was now in vain because the praise for this contribution was from the “wrong critic”, Hu Shih. Amid a large campaign in the 1950s to criticise Hu Shih's “bourgeois thought”, The Travels was depicted as a “reactionary” book written by a “traitor of the national interest”, and its popularity was attributed to Hu Shih’s puffery. “Any excerpts from The Travels or any articles about it should be removed from all textbooks, and all the wrongful narratives on the book and its author should be corrected.”Footnote 42 Although some scholars tried to resist such extremism, these efforts soon became futile with the coming of an even more extremist era in 1966.Footnote 43 A re-evaluation of The Travels was not brought up until the new epoch in the 1980s, but now the task was only to rescue The Travels from the political vortex and to reestablish its place in the literary canon. Nobody seemed to want to bother with “superstitions” anymore, not to mention to give the Baixin edition its due attention.Footnote 44

In the reprinted version of Liu Dashen's 1939 memoir, the original footnotes now deemed inappropriate to the spirit of the new time, have been removed. As a result, the anecdotes that I have translated above, telling how The Travels was hailed as a prophecy, have gone missing. What has also gone is the pardon that Liu Dashen issued to the “forgery maker” Fu Youpu after he had seen Fu's confessional essay. In one of the missing footnotes, he wrote:

Mr Fu's work in itself also has considerable value. Besides showing our respect for Mr Fu's honesty and courage, my brother and I hope that the publisher [of the Baixin edition] would restore Mr Fu's name as the author of the sequel and also include his confessional essay into the book when it is reprinted. This is not only to avert the eclipse of Mr Fu's talent; this is also to cherish an unusual literary encounter, so that in the future people will have a good story to tell.Footnote 45

This kind-hearted proposal, however, was never put into action. In fact, the words themselves were taken off the record in the new era. I close the article by restoring these words here, not only out of the admiration for Liu Dashen's big heart. More than that, I think this simple and unassuming note describes quite aptly what this article wants to achieve most. True, it aims at excavating an unknown history of reception of The Travels of Lao Can, and it reveals how and why a literary masterpiece for us was read as a book of prophecy in its own historical context. As a case study, it also sheds new light on deeper questions about the relationship between print culture, literary consumption, and the production of occult knowledge in China's modern transition. But on top of all these, this article sought to get closer to that “good story” that has been forgotten. I hope I have told the story well.

Acknowledgements

This article was written and accepted when I was a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, which also provided generous funding to make the article Open Access. I am grateful to Andrew F. Jones, Sophie Volpp, Robert Ashmore, Nicolas Tackett, and the two anonymous reviewers of JRAS for their help in the writing and revision process. I also thank David Johnson, Ted Huters, Chris Rea, the Princeton community (especially Paize Keulemans and Jonathan Gold), the Georgetown community, and Shoufu Yin and Hui-Lin Hsu, among many others who have read or commented on the manuscript.