page 1041 note 1 The third syllable seems to be distinctly o, not ho, both in the inscriptions and on the coins.

page 1043 note 1 It must have been by some slip of the pen that McCrindle presented this name as Mombaros, with o (instead of a) in the first syllable. He was using the text published by Didot, in Geographi Graeci Minores, vol. 1, which (p. 289)Google Scholar gives the genitive ![]() and presents Mambarae in the Latin translation. In respect of the reading, Müller, observed in his Prolegomena, p. 144, that we should read

and presents Mambarae in the Latin translation. In respect of the reading, Müller, observed in his Prolegomena, p. 144, that we should read ![]() with the codex.Google Scholar

with the codex.Google Scholar

page 1043 note 2 “We can now see more clearly how the name Nahapāna became transformed into Mambanos or Mambanēs. The ease with which the H as eta (and necessarily also as h), the M and the N might, at any rate in their cursive forms, all be confused with each other, is well illustrated by the coins of Kanishka and Huvishka. It may also be well recognized in the table of cursive Greek characters given by SirThompson, Edward Maunde in his Greek and Latin Palæography, at page 148.Google Scholar

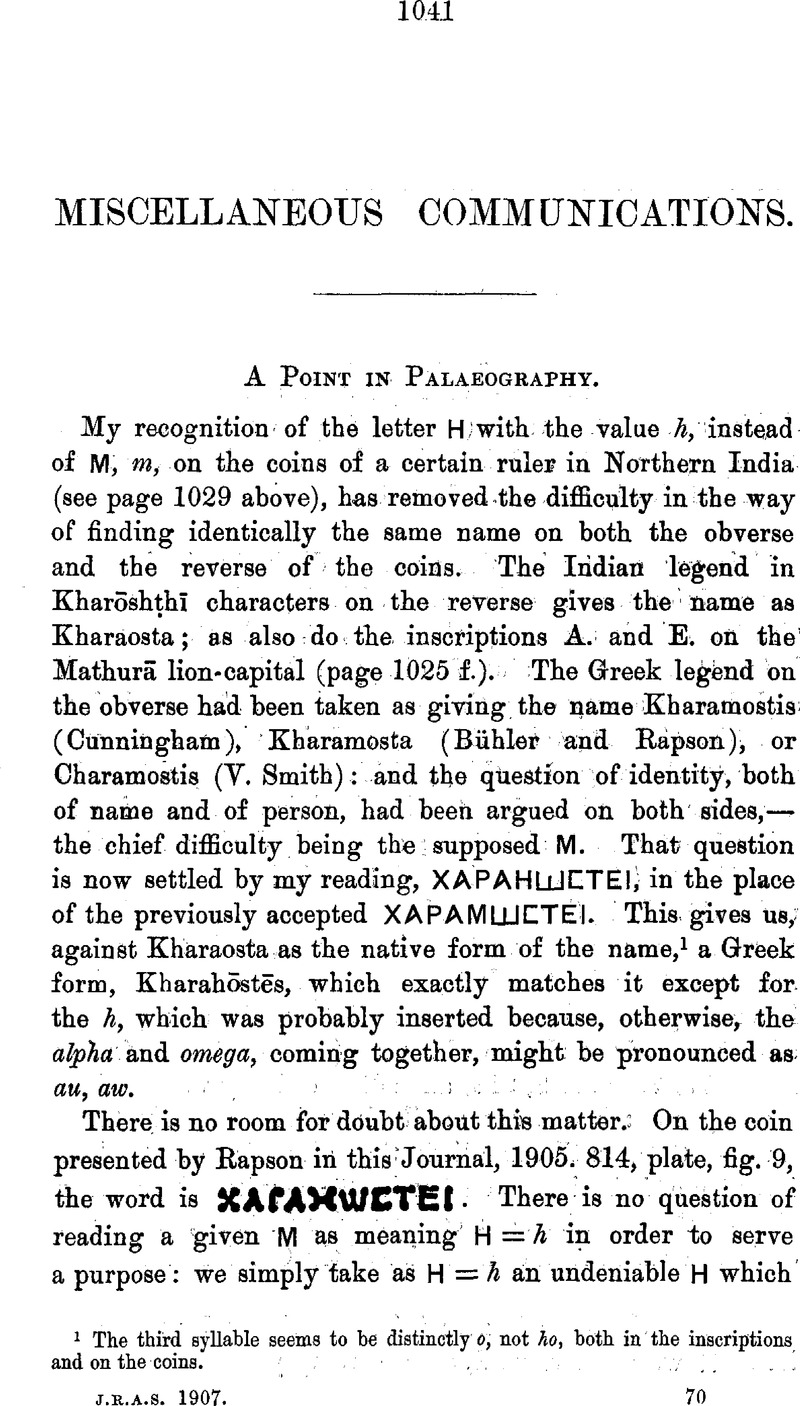

The initial m in the form ![]() came from some copyist's confusion of nu and mu. The second m, however, came, not from any insertion of an m, under phonetic influence or otherwise, as in the case of Palibothra, Palimbothra, but from a similar confusion of h and mu: just as modern numismatists have been mistaking Η for Μ on the coins of Kharaosta, Kharahōstēs, so some ancient copyist—(or possibly the author of the Periplus himself, in citing the name from a coin)—made the same mistake with the name of Nahapāna, written, not exactly in its full form

came from some copyist's confusion of nu and mu. The second m, however, came, not from any insertion of an m, under phonetic influence or otherwise, as in the case of Palibothra, Palimbothra, but from a similar confusion of h and mu: just as modern numismatists have been mistaking Η for Μ on the coins of Kharaosta, Kharahōstēs, so some ancient copyist—(or possibly the author of the Periplus himself, in citing the name from a coin)—made the same mistake with the name of Nahapāna, written, not exactly in its full form ![]() but, with the omission of an alpha, as

but, with the omission of an alpha, as ![]() in which form it actually occurs on some of the coins. That mistake produced the form

in which form it actually occurs on some of the coins. That mistake produced the form ![]() or, with the mistake in the initial letter already made,

or, with the mistake in the initial letter already made, ![]() From that we might have

From that we might have ![]() under phonetic influence: or a cursive pi might easily be mistaken by a copyist for a cursive beta (see Thompson's table of the Greek cursives).

under phonetic influence: or a cursive pi might easily be mistaken by a copyist for a cursive beta (see Thompson's table of the Greek cursives).

page 1044 note 1 There are twenty-four characters— (should have been twenty-six)— in the Greek legend, but only twelve in each of the others.

page 1044 note 2 No doubt some of the coins present rañō, as read by Mr. Scott. But there is no clear instance of the ō in. the specimens seen by me. The Greek transliteration ranniō is interesting, as illustrating the pronunciation of jñ and ñ, ññ, with the y-sounḍ.

page 1045 note 1 Dr. Stein's case for an h-value of O rests chiefly (IA, 17. 91, 95) upon the name ![]() as = the Pahlavī and modern Persían Māh, the, Moon-god and upon the, regal, title

as = the Pahlavī and modern Persían Māh, the, Moon-god and upon the, regal, title ![]() as = shāhanāno shāh as a form of the Irañian shāhan-shāh. I have no special object in denying the possibility. But Dr. Stein himself has indicated Māo as the Avestic name of the Moon-god; and we have О = clearly u, w, at least in

as = shāhanāno shāh as a form of the Irañian shāhan-shāh. I have no special object in denying the possibility. But Dr. Stein himself has indicated Māo as the Avestic name of the Moon-god; and we have О = clearly u, w, at least in ![]() the Wind-god,. the Vēdic Vāta Wāta, and probably in.

the Wind-god,. the Vēdic Vāta Wāta, and probably in. ![]() = Vanaiñti-(uparatãṭ); and it, seems to me that the cases specially relied upon by him are fully met by treating the О as o itself, withthe value u, w;— especially since, in another of his cases, against the usual

= Vanaiñti-(uparatãṭ); and it, seems to me that the cases specially relied upon by him are fully met by treating the О as o itself, withthe value u, w;— especially since, in another of his cases, against the usual ![]() we have an instance of

we have an instance of ![]() (Cunningham, , Coins of the Kushāns, plate 22, fig. 9). We may also ask:— If Ŏ had some-times the value h, why was not the first component of the Indian name Mahāsēna. (see page 1047 below) transliterated by

(Cunningham, , Coins of the Kushāns, plate 22, fig. 9). We may also ask:— If Ŏ had some-times the value h, why was not the first component of the Indian name Mahāsēna. (see page 1047 below) transliterated by![]() Google Scholar

Google Scholar

This question about the h-value of O may be considered fully when we come to deal with the name ![]() Oēsho, Oēsha (in one exceptional case

Oēsho, Oēsha (in one exceptional case ![]() Oēzo), applied to a god who is unmistakably Śiva. I regard this word as a very good attempt to represent in Greek the Sanskṛit Vṛisha, as pronounced Wṛisha or Wisha, which, in addition to denoting Śiva's bull, was an appellation of Śiva himself as ‘the rain-maker.’

Oēzo), applied to a god who is unmistakably Śiva. I regard this word as a very good attempt to represent in Greek the Sanskṛit Vṛisha, as pronounced Wṛisha or Wisha, which, in addition to denoting Śiva's bull, was an appellation of Śiva himself as ‘the rain-maker.’

The words quoted in this note, and some of those quoted in my text, ought to he shewn in cursive characters. But it has not been found convenient to do so on this occasion.

page 1046 note 1 We have something very similar, namely an eta representing a long ī, in ![]() alongside of

alongside of ![]() = Abhīra, and in

= Abhīra, and in ![]() = the Persian dīnār, which we have in Sanskīit as dīnāra.

= the Persian dīnār, which we have in Sanskīit as dīnāra.

page 1046 note 2 Professor Rapson has shewn us that the first component of the native name of this member of the Kadphisēs group is Vima, not Hima or Hema as had previously been supposed: see the Transactions of the Fourteenth Oriental Congress, Algiers, 1906, Indian Section, p. 219.Google Scholar

page 1046 note 3 It appears probable that the first step was the same in the production of the literary form ![]() = Hiraññabāha, Hiraṇyavāha: first, the rough breathing was understood, and then it seems to have been lost under the influence of

= Hiraññabāha, Hiraṇyavāha: first, the rough breathing was understood, and then it seems to have been lost under the influence of ![]() ‘lovely,’ applied particularly to places.

‘lovely,’ applied particularly to places.

page 1047 note 1 See my note “A Coin of Huvishka,” in the next number of this Journal.

page 1047 note 2 This is, perhaps, MrThomas', fig. 10 in his plate in this Journal, 1877, 212; or it may be from the same die with Mr. V. Smith's plate 12, fig. 8. The name occurs again as Maasēno in Gardner's plate 28, fig. 24; Cunningham's plate 20, fig. 17: where, however, the legend is too small to be drawn. It also occurs in the same way (Mr. Allan tells me) on a fourth coin, originally belonging to Sir A. Cunningham, now in the British Muṣeum: I have not reproduced this legend, because it is practically identical with the second one given above.Google Scholar

page 1047 note 3 It is the case that there are instances amongst the coins of Nahapāna in which, instead of the second alpha being omitted as in the form ![]() (see note 2 on page 1043 above), the h was omitted and the alpha was preserved. But the legend had then become corrupted in various ways: the initial nu was reversed; the Latin P was substituted for the Greek

(see note 2 on page 1043 above), the h was omitted and the alpha was preserved. But the legend had then become corrupted in various ways: the initial nu was reversed; the Latin P was substituted for the Greek ![]() the third alpha also was omitted; and so (see the illustrations given with Mr. Scott's article) we have such forms as

the third alpha also was omitted; and so (see the illustrations given with Mr. Scott's article) we have such forms as ![]() … and

… and ![]()

Even in the best specimens of their work, Nahapanās die-sinkers were unable to bring the whole of, the Greek legend onto their dies. But they were careful to omit from those specimens only the comparatively unimportant final a of the genitives zaharatasa and nahapanasa. Huvishka's die-sinkers, however, were not hampered in that manner at all: there was ample room to insert the h on the Mahāsēna coins, if it had then been known.