Introduction

Modern scientific interest in cetacean diversity emerged in the mid-1700s all over Europe based on the examination and collection of specimens originating from animals found dead or killed on the beach or near shore – nowadays collectively known as ‘stranding records’. Although being a heterogeneous dataset, they none the less constitute the only long-time series available for comparative studies into species diversity and changes therein (Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, MacLoud, Hall, Bereton, Dunn, Wall, Jepson, Deaville and Pierce2011).

For the entire North Sea coastline, cetacean stranding records date back to the 13th century, but systematically they have only been compiled and published for about a century with regular British stranding reports commencing in 1913 (Harmer, Reference Harmer1927). The first comprehensive Dutch compilation appeared in 1931 (van Deinse, Reference Van Deinse1931) with regular reports published since then. From the Danish coastline older records date back to 1575 and new records up till 2017 were compiled by Kinze and co-authors (Kinze, Reference Kinze1995; Kinze et al., Reference Kinze, Tougaard and Baagøe1998, Reference Kinze, Jensen, Tougaard and Baagøe2010, Reference Kinze, Thøstesen and Olsen2018).

While British, Dutch and Danish strandings are reported on a regular basis, similar overviews covering the entire German North Sea coastline so far have been unavailable, despite earlier attempts to launch a systematic reporting scheme for cetacean strandings (Mohr, Reference Mohr1937; Kock, Reference Kock1976). It was only in the mid 1980s that cetacean species found along the German North Sea coast became the subject of scientific investigations, with a stranding network being established only by 1990 after the first seal die-off (Benke et al., Reference Benke, Siebert, Lick, Bandomir and Weiss1998; Siebert et al., Reference Siebert, Gilles, Lucke, Ludwig, Benke, Kock and Scheidat2006). However, Schultz (Reference Schultz1970), in his review of North and Baltic Sea cetacean occurrences had already included some German North Sea records covering the period to 1969, mainly from the northern coasts, i.e. the German federal state of Schleswig Holstein (SH). Goethe (Reference Goethe1983), Meyer (Reference Meyer1994) and Stede (Reference Stede1994) reviewed finds from the coast of the federal state of Niedersachsen (NI) until 1992 while Borkenhagen (Reference Borkenhagen2011) added and corrected records for the SH coast to 2010.

The harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) is the most common cetacean species in the North Sea (Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Berggren, Benke, Borchers, Collet, Heide-Jørgensen, Heimlich-Boran, Hiby, Leopold and Øien2002) and comprehensive studies during recent decades have re-stablished its status as an abundant native species in the German Bight (Siebert et al., Reference Siebert, Gilles, Lucke, Ludwig, Benke, Kock and Scheidat2006) and the lower reaches of all major German rivers (Wenger & Koschinski, Reference Wenger and Koschinski2012).

Kinze et al. (Reference Kinze, Adddink, Smeenk, Garcia Hartmann, Richards, Sonntag and Benke1997) summarized records from the entire German North Sea coastline of white-beaked (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) and Atlantic white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus acutus) for the years 1983–1992, while Ijsseldijk et al. (Reference Ijsseldijk, van Neer, Deaville, Begeman, van de Bildt, van den Brand, Brownlow, Czeck, Dabin, ten Doeschate, Herder, Herr, IJzer, Jauniaux, Jensen, Jepson, Jo, Lakemeyer, Lehnert, Leopold, Osterhaus, Perkins, Piatkowski, Prenger-Berninghoff, Pund, Wohlsein, Gröne and Siebert2018a) included the most recent records of the white-beaked dolphin along the German North Sea coasts in their study. The 2016 sperm whale mass strandings all over the North Sea prompted a detailed investigation (Unger et al., Reference Unger, Bravo Rebolledo, Deaville, Gröne, IJsseldijk, Leopold, Siebert, Spitz, Wohlsein and Herr2016; Ijsseldijk et al., Reference Ijsseldijk, Brownlow, Davison, Deaville, Haelters, Keijl, Siebert and ten Doeschate2018b).

Here we provide the first full review of all cetacean species records from the German North Sea coast and lower reaches of the larger rivers based on archival data, earlier publications, newspaper records and hitherto unpublished data. Due to the large number of stranding records for the harbour porpoise, below we only summarize available data while for all other less frequently occurring cetaceans we provide full details.

Finally, we offer a zoogeographic interpretation of these local cetacean occurrences.

Materials and methods

The data sets used for the present analysis comprise cetacean stranding records, here defined as any whale corpse encountered at a certain locality along a stretch of coast or riverbank at a given date within the German North Sea coastline. Although circumstances may vary, these records are considered to provide the most reliable faunistic signal over time. Cetacean corpses discovered in advanced and final stages of decomposition and finds of skeletal remains were excluded from the analysis in order not to weaken the signal due to possible drift-ins from other waters hereby causing temporal imprecisions.

Records were compiled from archive sources, published information (newspaper reports and popular and scientific reviews and papers) and databases held at the Institute for Terrestrial and Aquatic Wildlife Research, the Lower Saxony State Office for Consumer Protection and Food Safety, the Seal Nursery and National Park Center Norddeich, the Wadden Sea National Park Authority of Lower Saxony, natural history museum collections in Oldenburg, Wilhelmshaven, Bremerhaven, Hamburg, Kiel, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Berlin and critically reviewed and assigned to a cetacean species using standard determination procedures. False species identifications and double counts were corrected.

Subdivision of the coastal and riverine areas

Geographically, the German North Sea coastline is of considerable length (1155 km Table 1) as it includes both the shores of the mainland and that of several chains of islands. A major part of the Wadden Sea is found in German coastal areas and ecologically they are governed by its tidal regime. Further, the German coastal waters are influenced by the combined freshwater discharge of four larger rivers into the German Bight: the Ems, the Weser, the Elbe and the Eider, second only to the Rhine estuary output which also affects the adjacent German North Sea coastline (Radach, Reference Radach1992). As such, the German Bight forms a biologically relevant sub-entity of the larger North Sea.

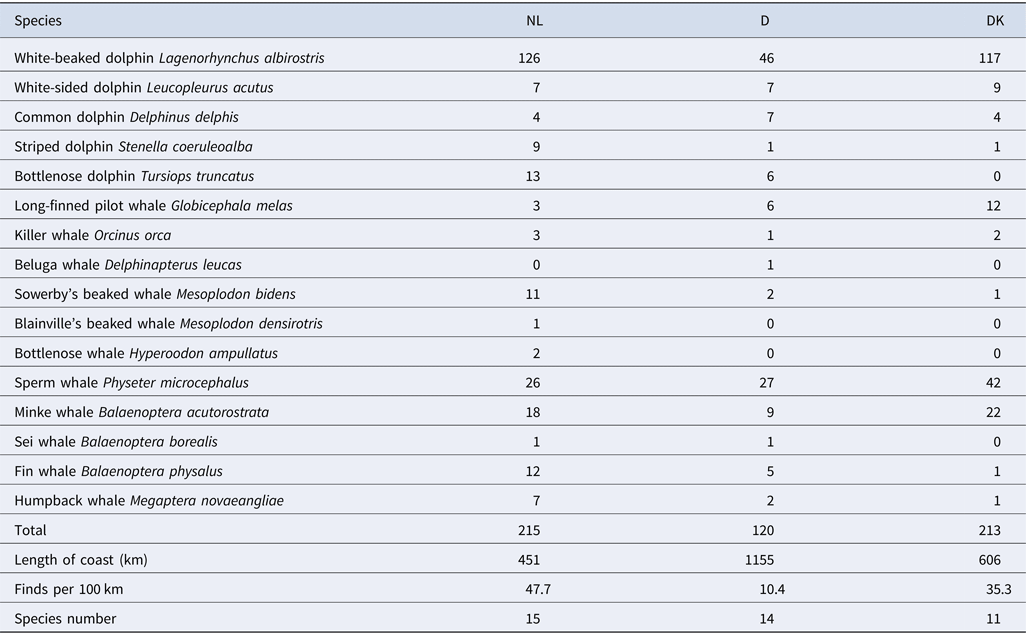

Table 1. Non-phocoenid cetacean record for the German North Sea coastal area in total and subdivided into four 50 years periods and finds older than 1818

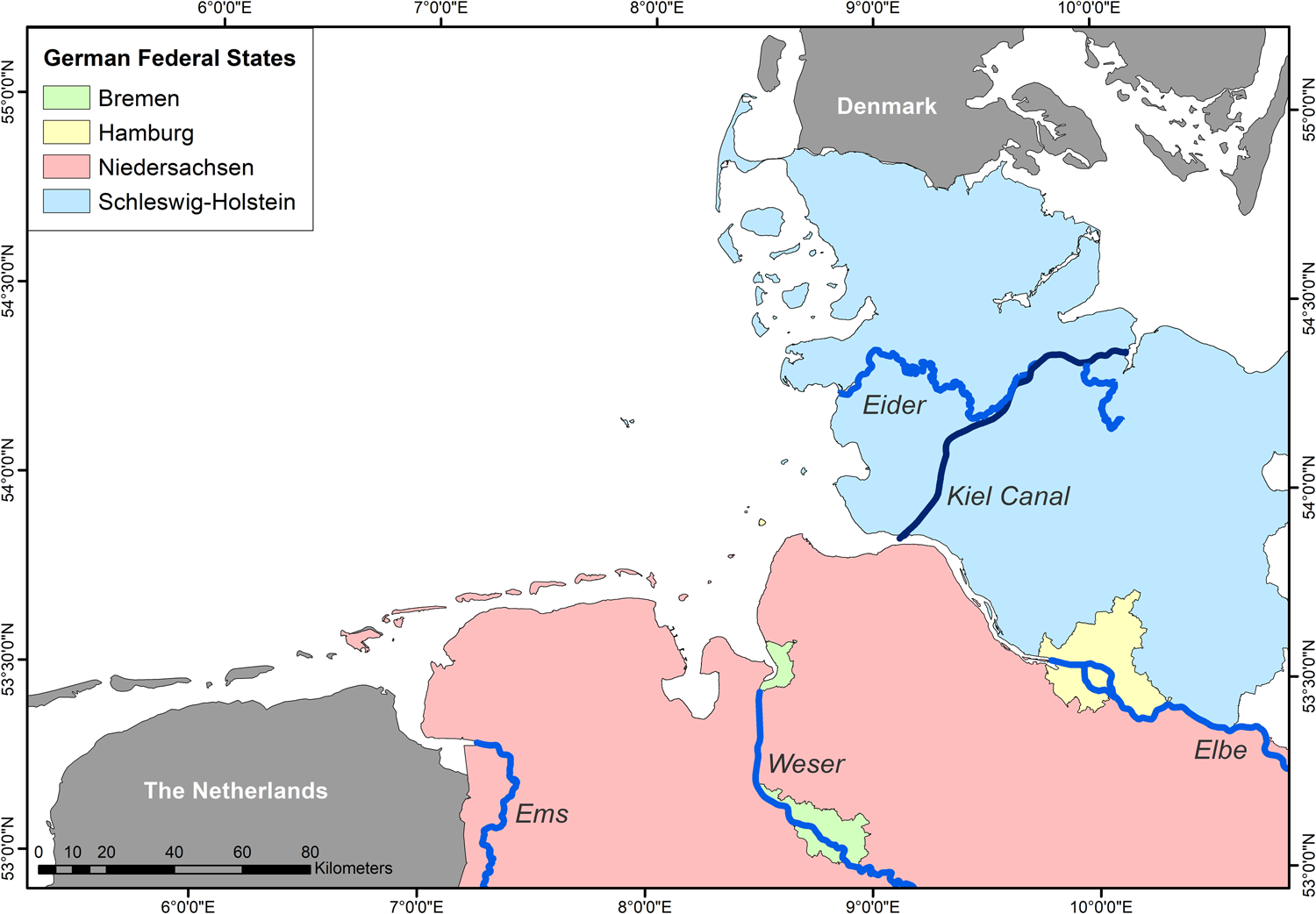

Administratively, the major portions of the coastline of the German North Sea belong to the federal states of Niedersachsen (NI) and Schleswig-Holstein (SH), respectively, while two tiny portions are part of the federal states of Hamburg (HH) and Bremen (HB), respectively. The River Elbe for about 110 km forms the border between SH and NI and also includes the major part of the HH coastline (Figure 1). Here we subdivide the German North Sea coastlines into a south-western component (Ems estuary to the mouth of Elbe; SW (NI) or SW (HH) for the island of Neuwerk), a north-eastern component (mouth of Elbe to Danish border; NE (SH)), and four riverine components (lower courses of the rivers Ems, Weser, Elbe and Eider; R Ems, R Weser, R Elbe and R Eider, respectively).

Fig. 1. The German North Sea coastline showing federal states and major rivers.

Validation of species assignments and deletion of double counts

Since the onset of zoological nomenclature with the 10th edition of Linnæus Systema Naturae in 1758 the number of cetacean species has increased from originally eight to about 40 extant North Atlantic cetacean species (Jefferson et al., Reference Jefferson, Webber and Pitman2015). While the identification of a species relies on specific diagnostic features either depicted on an illustration or description in words, the scientific name of the species may have changed over time. Therefore, sometimes incorrect species assignments survived till the present day although the record originally was based on correct contemporaneous literature available. For our taxonomic review we follow Jefferson et al. (Reference Jefferson, Webber and Pitman2015) and our validation is based on collection specimens, depictions and descriptions from literature including newspaper records.

In northern European waters traditionally two small cetacean species have been recognized: a smaller (i.e. the harbour porpoise Phocoena phocoena) and a larger ‘porpoise’ species (i.e. an ‘umbrella species’ containing present-day bottlenose dolphin Tursiops truncatus and other similar sized delphinids). This conception can be traced back in time to at least the early 18th century. Both species were referred to as ‘Tümmler’ in the German language and without further specification the two species probably from time to time were confused with one another. Until 1975, the harbour porpoise and the bottlenose dolphin indeed were the most common species along the Dutch coast (Kompanje, Reference Kompanje2001).

Also, bottlenose and white-beaked dolphins have been confused with one another as already pointed out by van Bree (Reference Van Bree1970). Among the rorqual species as well several misidentifications have been revealed with minke whales being reported twice – erroneously as blue whale calves and correctly as minke whale adults from the same locality and almost the same date (Goethe, Reference Goethe1983).

The drift of cetacean carcasses is influenced by the dynamics of the hydrographic regime of the North Sea, and along the German North Sea coast in particular the shifting tides of the Wadden Sea. Therefore, as a source of error the same individual when not collected may have been reported several times from different localities and over time in different stages of decomposition.

Results

Including the harbour porpoise, 19 cetacean species have been recorded along the German North Sea coastline, the lower reaches and tributaries of the Ems, Weser, Elbe and Eider rivers.

In total, 239 individuals of non-phocoenid cetaceans (i.e. species other than the harbour porpoise) comprising 18 species were compiled and validated. The earliest record documented concerns a multiple sperm whale stranding on the island of Pellworm (SH) in 1604. Rare occurrences comprise the narwhal (1669 and 1736 only), Risso's dolphin (twice in 1873 only), and the blue whale (1881 only). Records for the latest 50 years (1968–2017) hence comprise 16 species only. More than half of these records (N = 122) originate from the period 1990–2017 comprising 13 species in addition to the harbour porpoise for which during the same period the number amounted to 3734 (see below) (Table 1).

Harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena (Linnæus, 1758))

The harbour porpoise throughout time has been recognized as the only native species in the German Bight.

For the NE (SH) coast Mohr (Reference Mohr1962) reported on the species providing qualitative data whilst Goethe (Reference Goethe1983) and Meyer (Reference Meyer1994) compiled similar records for the period 1840–1989 for the NI (SW) coastline.

The species, now supported by quantitative data, is regarded as an indigenous inhabitant of the entire North Sea. Quantitatively, this status within the German part of the North Sea only became well-established by the late 1980s when annual stranding numbers became available in conjunction with the set-up of dedicated stranding networks in the various federal states.

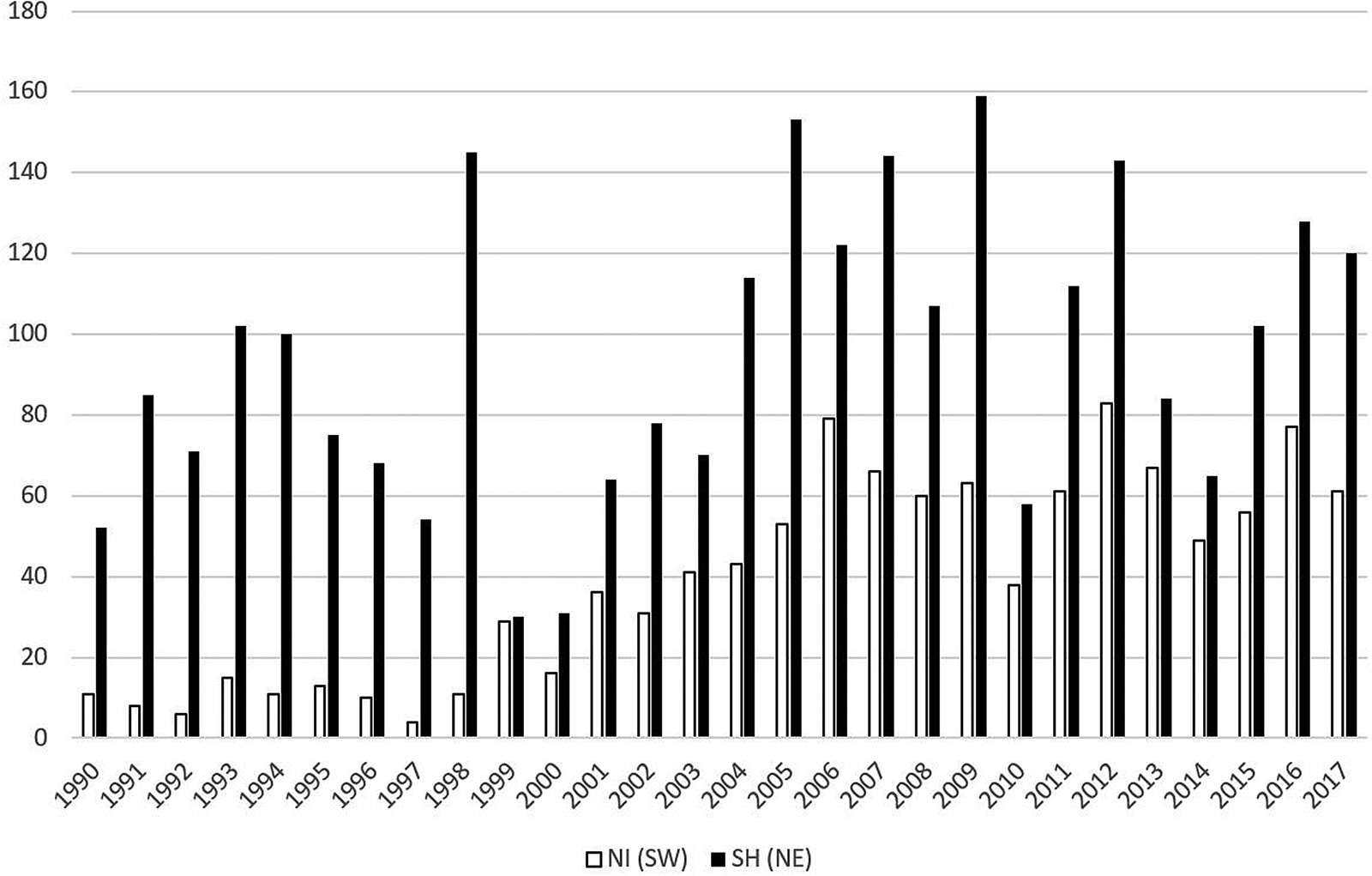

The total number of stranding records for the years 1990–2017 was 3764. While the numbers for SW (NI) exhibit an increase over time, indicative of a shift in distribution to the south, the NE (SH) figures fluctuate. Figure 2 provides an overview of the annual number of harbour porpoise strandings for NI and SH, respectively, for the period 1990–2017.

Fig. 2. Number of harbour porpoise strandings 1990–2017. NI (SW) = federal state of Niedersachsen (south-western component), SH (NE) = federal state of Schleswig-Holstein (north-eastern component).

The harbour porpoise used to be seasonally abundant in the lower reaches of all major rivers discharging into the German Bight, but due to increased pollution occurrences probably ceased totally in the mid-1990s.

For German rivers historical records are known from the River Elbe at least since 30 December 1651 (newspaper report in Extra Ordinari Mittwochs Postzeitungen CCCIV, 8 January 1652) and the River Weser as early as 2 April 1670 (Poppe, Reference Poppe1882). Subsequent occurrences also include the River Rhine (1885, city of Emmerich (le Roi & von Schweppenburg, Reference le Roi and von Schweppenburg1909), River Ems (de Fries & Focken, Reference de Vries and Focken1881), and the River Eider (August 1863, city of Tönning; newspaper report Vestslesvigsk Tidende, 10 August 1863).

A recolonization of the Elbe and the Weser rivers by the species has occurred, most likely caused by the significant habitat improvements of recent decades (Wenger & Koschinski, Reference Wenger and Koschinski2012), while re-entrances to the lower River Eider may have been hampered though not entirely blocked by the construction of the Eider Barrage in 1973.

White-beaked dolphin (Lagenorhynchus albirostris Gray 1846)

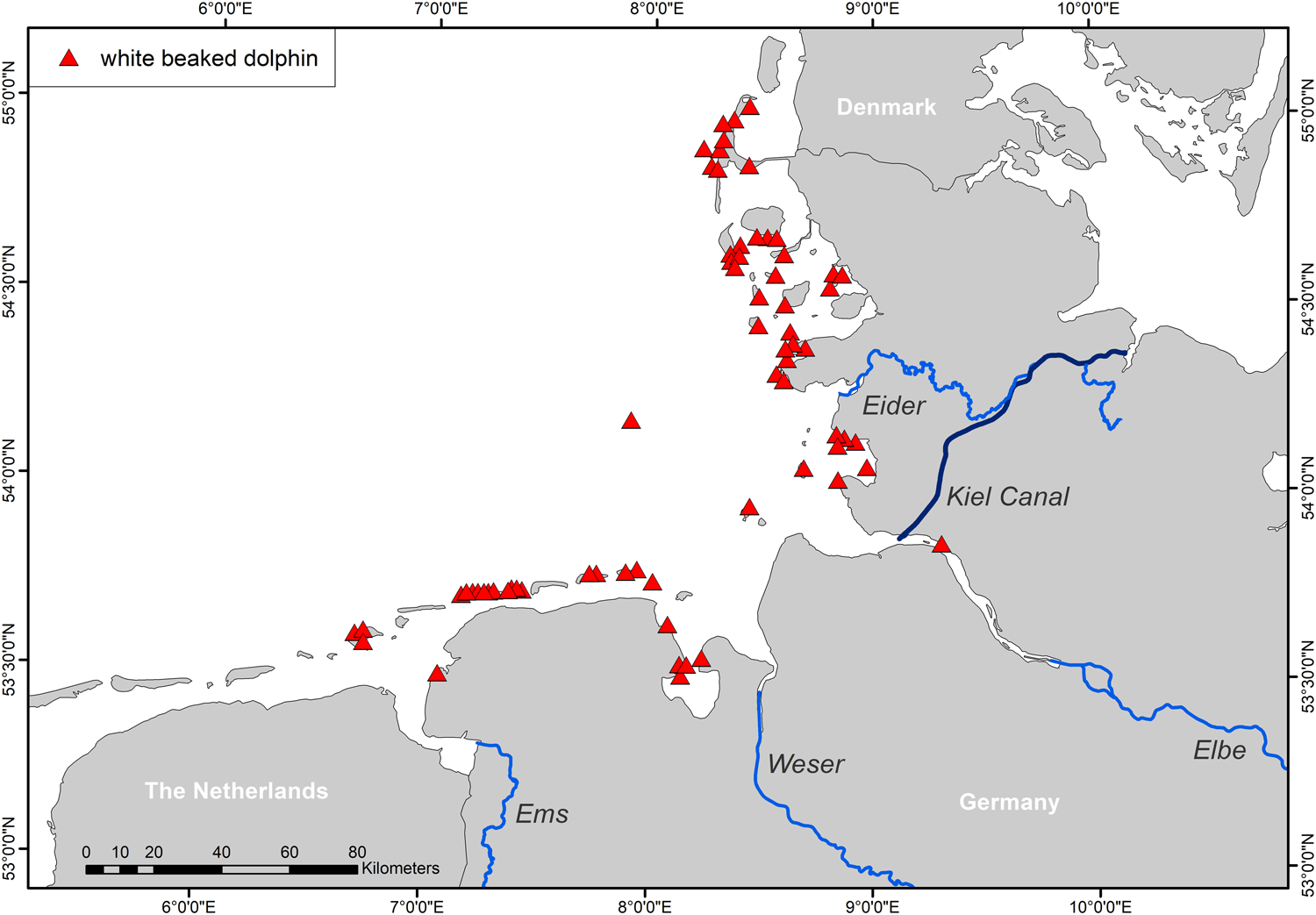

The white-beaked dolphin is the second most frequent cetacean species encountered along the German North Sea coastline with altogether 64 strandings since 1920 (Appendix 1). While peaking in the 1990s, fewer strandings have been recorded during the last two decades (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Records of white-beaked dolphins.

Occurrences prior to 1980 only account for six records exhibiting several decadal gaps and therefore may be under-represented due to confusion with the bottlenose dolphin. There are specimens of Lagenorhynchus albirostris most likely originating from the German North Sea coastline in the collections of several European museums (e.g. the Vienna Natural History Museum) purchased as ‘Tursiops tursio’. The first definite German North Sea record of this species is from Büsum (NE (SH)) and in the year 1921 but was, however, not recognized as such until 1970 when van Bree (Reference Van Bree1970) corrected Mohr's (Reference Mohr1935) original species assignment ‘Tursiops tursio’ i.e. bottlenose dolphin. For the NE segment, Dahl (Reference Dahl1894, Reference Dahl1906) listed both the common dolphin (Island of Amrum without year specified) and the bottlenose dolphin (without details). Since for both these species quotations no diagnostic details were provided, it cannot be ruled out that they may have been finds of white-beaked dolphins instead. Tursiops tursio in sensu Mohr (Reference Mohr1935) hence is to be regarded synonymous with the white-beaked dolphin. Therefore, doubt must be cast on several other records of Tursiops tursio listed in her work. Pohle (Reference Pohle1941) considered Tursiops tursio (i.e in sensu Mohr = Lagenorhynchus albirostris) as ‘the other native species’ in German North Sea waters (see Appendix 1).

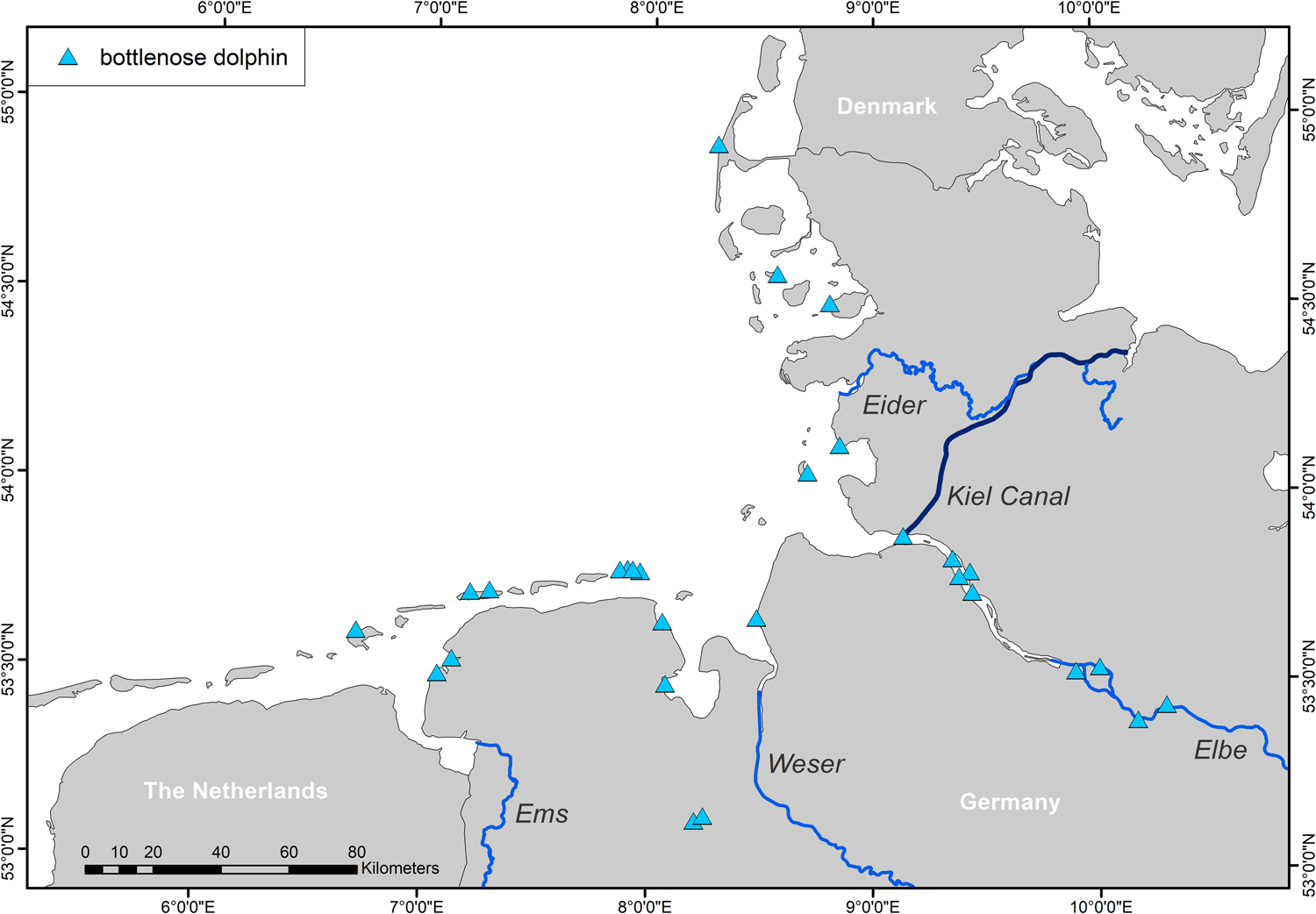

Bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus (Montagu, 1821))

Altogether there are 31 records of T. truncatus documented between 1836 and 1998 (Figure 4). Until the 1920s, river occurrences predominated while the most recent occurrences solely have originated from the south-western component of the German North Sea coast (SW (NI)).

Fig. 4. Records of bottlenose dolphins.

The occurrence of the bottlenose dolphin, as pointed out above, may have been blurred due to the confusion with both the white-beaked dolphin (van Bree, Reference Van Bree1970) and the harbour porpoise (Wiepken & Greve, Reference Wiepken and Greve1876).

The bottlenose dolphin possesses the highest riverine affinity second only to the harbour porpoise and has been documented for all major German riverine systems.

River Eider: In early March 1843, a school of 10–12 dolphins was sighted at Friedrichstadt at the confluence of the River Treene with the River Eider (NE (SH)). The estimated lengths (8–10 Danish feet; 2.5–3.1 m), the general behaviour and the school size fit both the white-beaked and the bottlenose dolphins, while the riverine and in-land locality only makes the latter species plausible (Danish newspaper Berlingske Tidende, 14 March 1843).

River Elbe: During the 19th century the species was documented for the year 1852 near Winsen (NI) (Poppe, Reference Poppe1882), 1860 near Glückstadt (SH) (Mohr, Reference Mohr1935), 1867 from an unspecified Lower Elbe locality (based on a specimen in the Copenhagen Zoological Museum), between 1875 and 1876 near Wittenberge (federal state of Brandenburg) (Erhardt, Reference Erhardt1937), in May 1879 at the confluence of the River Stör with the Elbe (SH) (Häpke, Reference Häpke1880; concerning a female and her newborn calf) and in 1924 from almost the same locality yet another animal (Wegener, Reference Wegener1924).

River Weser: In December 1836, an individual was caught at Drielake, Oldenburg (NI) (Wiepken & Greve Reference Wiepken and Greve1876, Reference Wiepken and Greve1897) while a ‘large dolphin’ was reported by Häpke from the town of Celle (NI) in the River Aller tributary to the Weser. Poppe (Reference Poppe1882) reported on an animal taken in 1852 in the Hunte, a tributary of the Weser.

Coastal records include a stranding near Wilhelmshaven (NI (SW)) in 1872 (Möbius, Reference Möbius1888). Schultz (Reference Schultz1970) listed two records of Tursiops from the NE (SH) Wadden Sea area (erroneously with reference to Mohr (Reference Mohr1935) but apparently based on photographic evidence in the Hamburg Mohr archive). Both records are from September 1935 and the Islands of Hooge (SH) and Nordstrand (SH), respectively. Mohr (Reference Mohr1961) under ‘false cover’ provided evidence on yet another specimen stranded on the island of Trischen (SH) without specified date.

Kompanje (Reference Kompanje2001) gave a comprehensive summary of Dutch strandings and found a marked decline in occurrence. By about 1975, the species here was reduced to the status of straggler. To the north, along the adjacent Danish coastline there has been an absence of the species since 1968 (Kinze, Reference Kinze1995). Our findings agree well with the general riverine and southern warmer-water distribution known for the species and possibly the bottlenose dolphins formerly occurring along the German North Sea coast thence formed part of the Dutch Zuiderzee population (Kompanje, Reference Kompanje2001).

Atlantic white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus acutus (Gray, 1828))

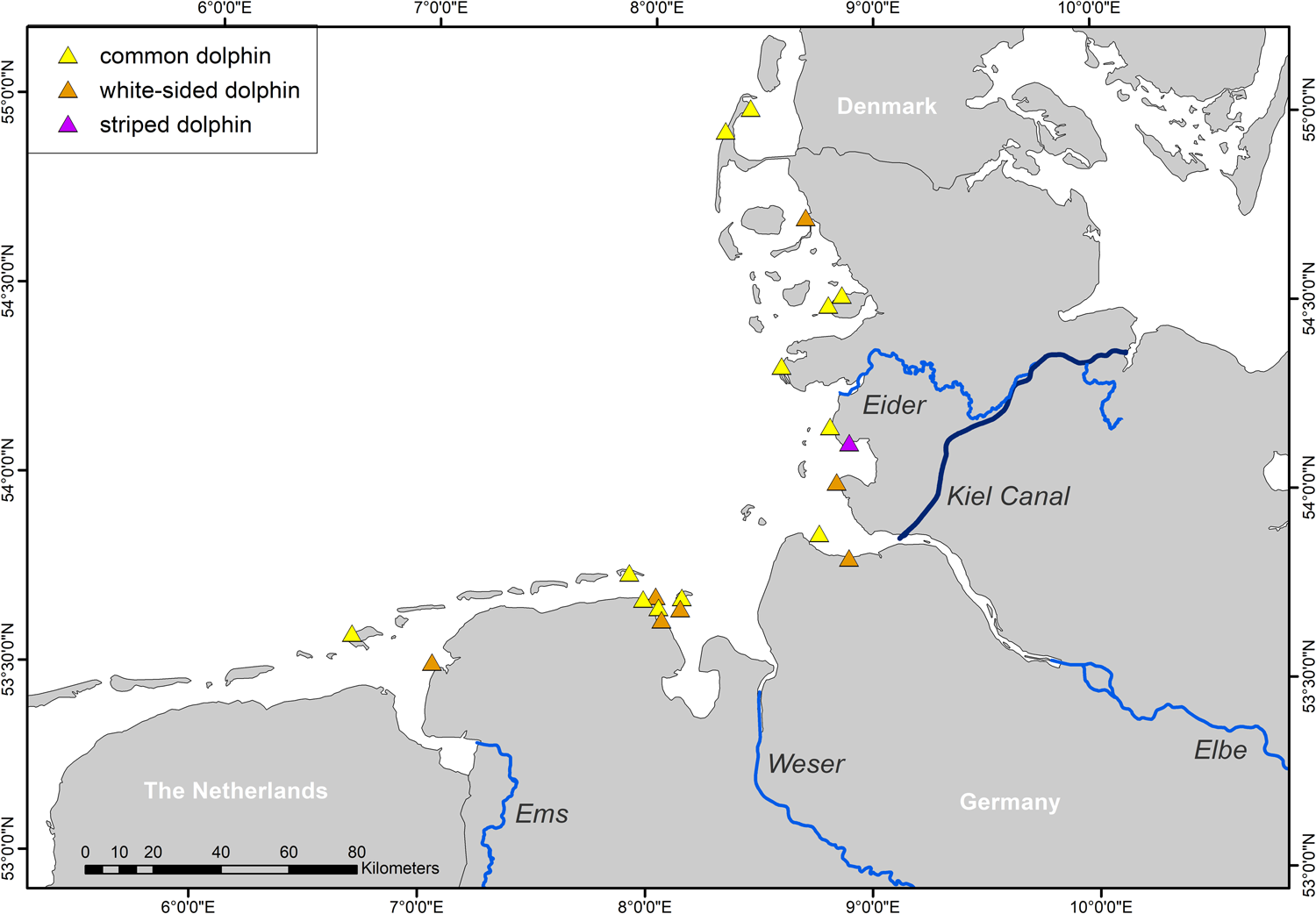

The Atlantic white-sided dolphin was recorded seven times from the German North Sea, the first time in 1968, a single find from the island of Schillig, SW(NI) (Goethe, Reference Goethe1983), while of the remaining six records five originate from the south-western (NI) coastline (all but one from the month of April) and a single from the north-eastern (SH) coastline from the month of September (Figure 5).

Fig. 5. Records of white-sided, common and striped dolphins.

Common dolphin (Delphinus delphis Linnæus, 1758)

The application of the name ‘Delphinus delphis’ also in the German literature has been a matter of great confusion. A species under this heading was ubiquitously listed for German waters, but with no specific records ever provided. Without certainty, whether the present-day species was meant, these records must remain dubious. Dahl (Reference Dahl1894, Reference Dahl1906) reported ‘Delphinus delphis’ from the island of Amrum, a record doubted by Mohr (Reference Mohr1935) who believed most German records of ‘Delphinus delphis’ instead to be bottlenose dolphins. However, as van Bree (Reference Van Bree1970) established, she confused bottlenose dolphins with yet another species: the white-beaked dolphin. Poppe (Reference Poppe1882) listed ‘Delphinus delphis’ from the SW coast with reference to Heineken (Reference Heineken1837) who, however, also listed the species without any supportive evidence.

The first genuine record of the common dolphin originates from the SW coast and the year 1958 (Goethe, Reference Goethe1983) with 12 subsequent records (Figure 5).

The common dolphin during certain periods enters the southern North Sea, presumed to be indicative of an influx of warmer water. Fraser (Reference Fraser1937) reported such an earlier occurrence during the 1930s while Kompanje (Reference Kompanje2005) and recently Smeenk & Camphuysen (Reference Smeenk, Camphuysen, Broekhuizen, Spoelstra, Thissen, Canters and Buys2016a) reviewed the trends in occurrence along the Dutch coast.

Striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba (Meyen, 1833))

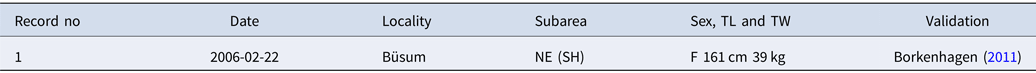

The striped dolphin was documented for the first time in 2006 near Büsum (NE (SH)), a single record adding a new species to the list of cetaceans recorded from German North Sea waters (Figure 5). The natural distribution area of the striped dolphin is both further south and further offshore than German coastal waters. Two Danish North Sea records were presented by Kinze et al. (Reference Kinze, Schmidt and Tougaard2000) and Kinze et al. (Reference Kinze, Thøstesen and Olsen2018), respectively, while adjacent Dutch records were reviewed by Kompanje (Reference Kompanje2005) and Smeenk & Camphuysen (Reference Smeenk, Camphuysen, Broekhuizen, Spoelstra, Thissen, Canters and Buys2016b).

Already in 1910, however, Trouessart (Reference Trouessart1910) had reported ‘Prodelphinus euphrosyne’ from near the mouth of the River Elbe. The source of his record is unfortunately unknown. Mohr (Reference Mohr1931) doubted this occurrence, quoting Brohmer (Reference Brohmer1914), as did Schultz (Reference Schultz1970) although citing Tomelin (Reference Tomelin1967) for this information. A misinterpretation of Möbius (Reference Möbius1873) so-called ‘Gestreifter Delphin’ (literally = striped dolphin), referring to two finds of Risso's dolphin near Büsum in 1873, seems evident.

Risso's dolphin (Grampus griseus (Cuvier, 1812))

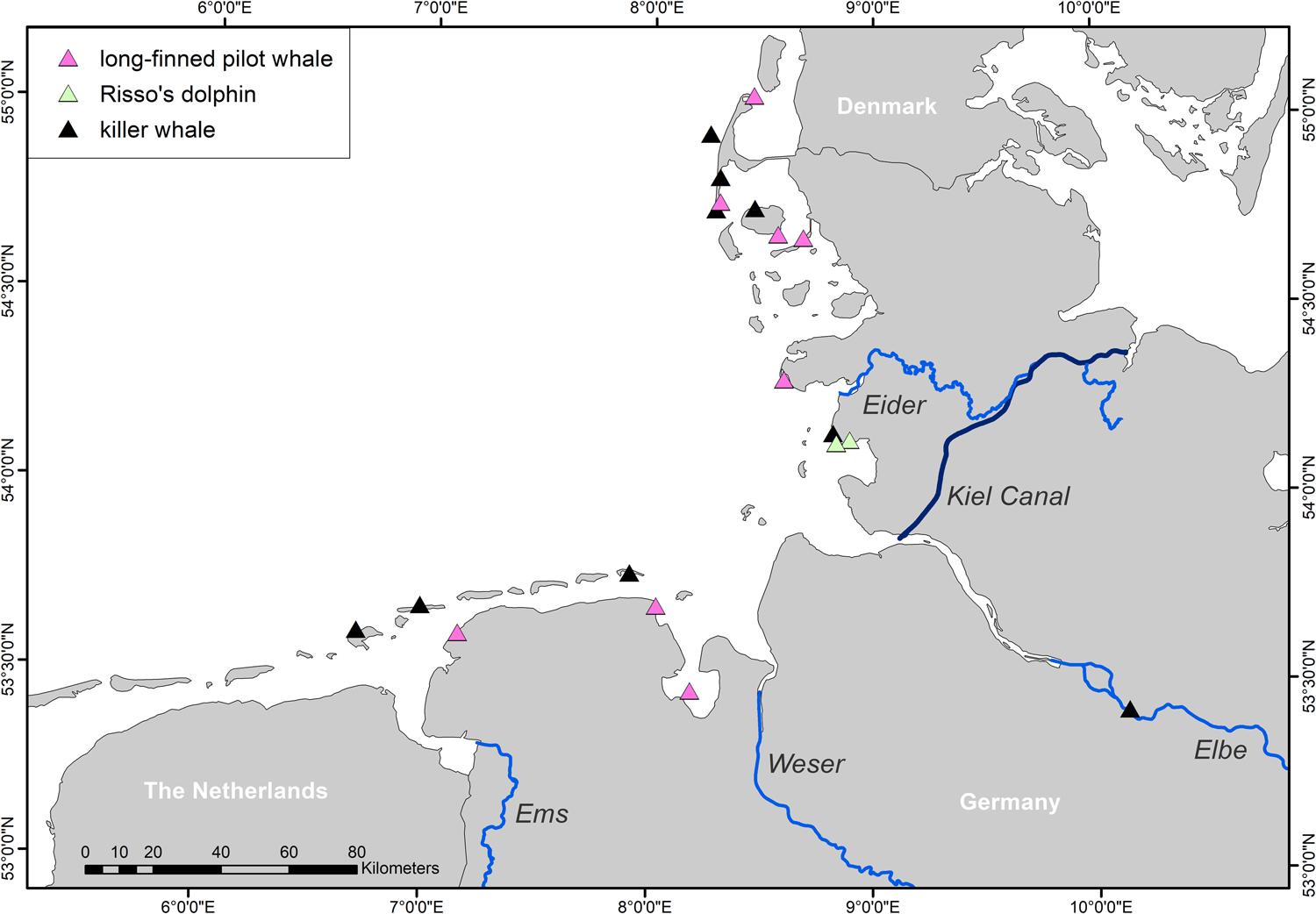

The first and hitherto only record from the German North Sea coast originates from the year 1873 (Figure 6).

Fig. 6. Records of Risso's dolphins, long-finned pilot whales and killer whales.

Two individuals of this species were found in February within two days of each other near the town of Büsum NE (SH) (Möbius, Reference Möbius1873). The literal translation of the German vernacular name ‘Gestreifter Delphin’ is striped dolphin and may have caused a confusion with Stenella coeruleoalba.

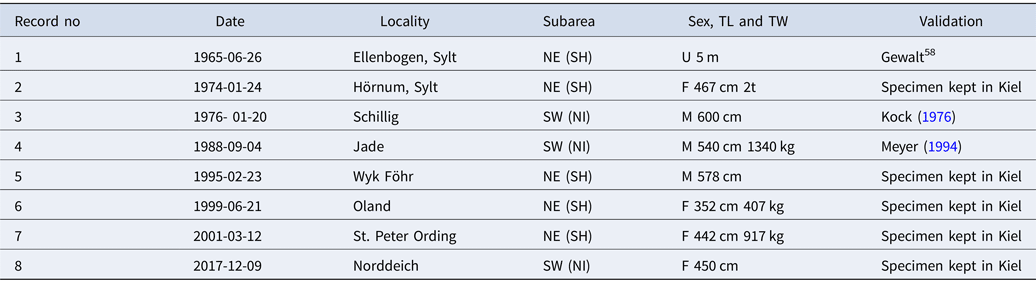

Long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melas (Traill, 1809))

The long-finned pilot whale was documented eight times (Figure 6). The first reported record of the species originates from the year 1965 and the island of Sylt (Gewalt, Reference Gewalt1971). Three finds were registered for the SW coast (1976, 1988 and 2017) and five for the NE coast (1965, 1974, 1995, 1999, 2001), respectively.

The long-finned pilot whale is an oceanic teuthophageous species and therefore probably poorly adapted to the coastal habitat and in particular to the Wadden Sea coast – alike sperm whales. Unlike these, they are much smaller and therefore may have escaped detection in earlier decades.

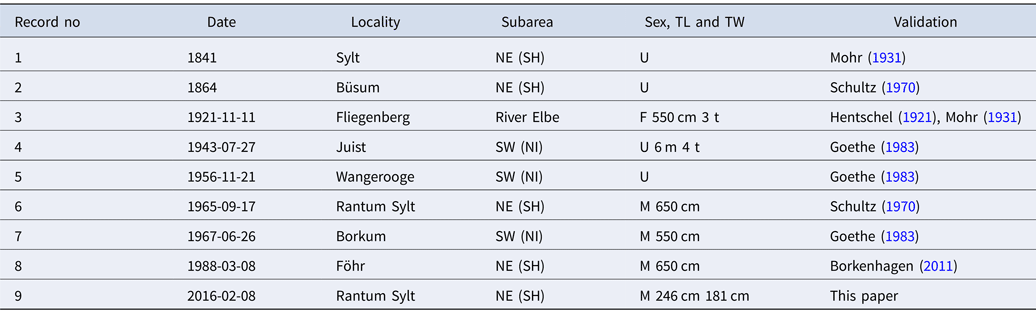

Killer whale (Orcinus orca (Linnæus, 1758))

Between 1841 and 2016 nine strandings of killer whale have been documented (Figure 6). Dahl (Reference Dahl1894, Reference Dahl1906) and Mohr (Reference Mohr1931, Reference Mohr1935) listed the earliest documented find (1841) from the island of Sylt (NE (SH)). Other older records of the species include an individual stranded on the shores of the island of Juist NI around World War I (Schultz, Reference Schultz1970) and another killed upstream in the Elbe at Fliegenberg (NI) in 1921 (Hentschel, Reference Hentschel1921).

The species was further encountered both for the SW coast (Juist 1943; Wangerooge 1956; Borkum 1967) and the NE coast (Sylt 1965, 2016; Föhr 1988), respectively. It is noteworthy that the 1943 killer whale was reported as a ‘Nordkaper’, a German vernacular name confusingly also in use for the fin whale and the North Atlantic right whale

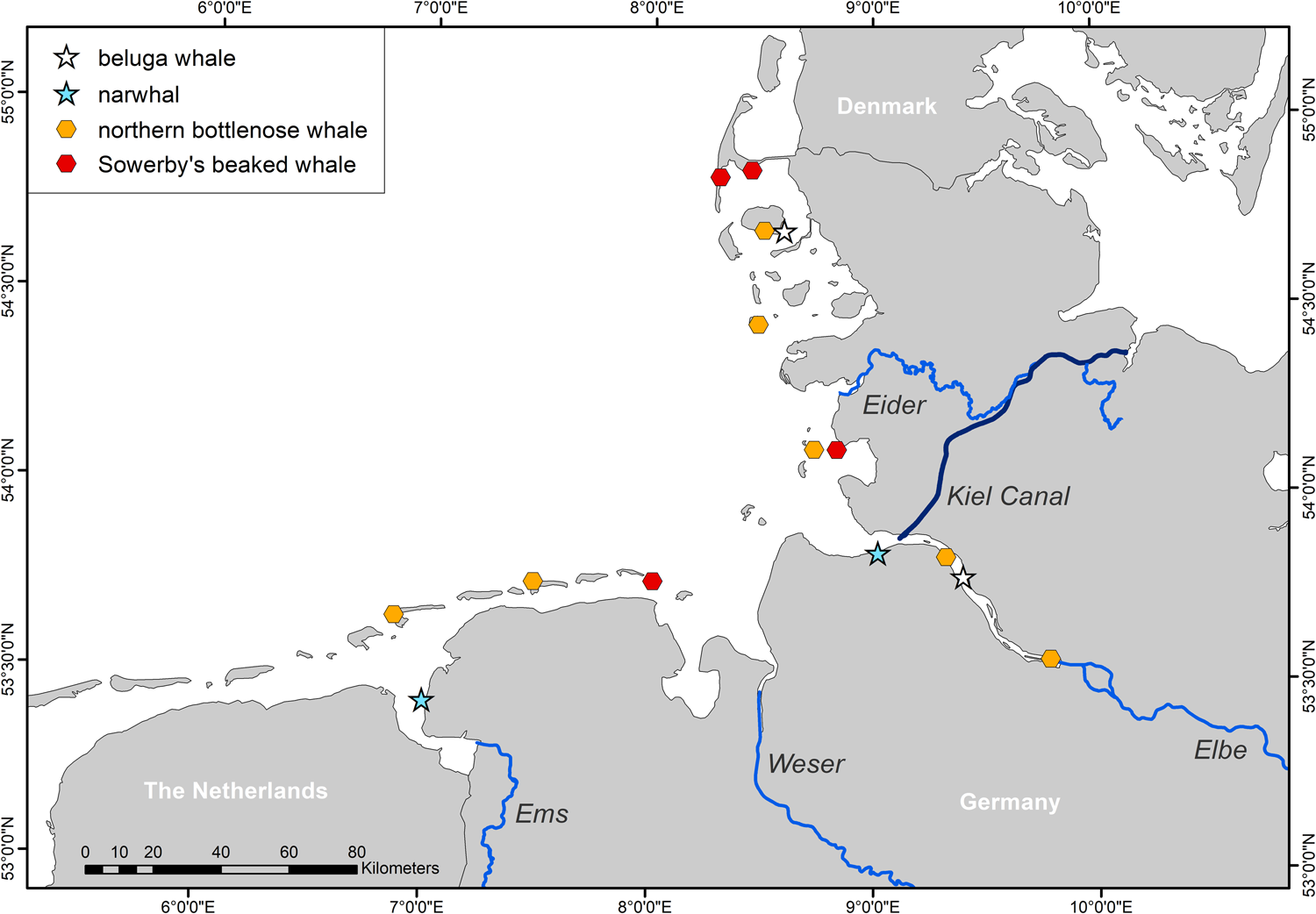

Beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas (Pallas, 1770))

Records of stranded dead belugas are rare due to the pronounced coastal adaptability of the species. Individuals often enter rivers and migrate upstream. Accordingly, the only German North Sea stranding hitherto reported was of a beluga whale found dead on the Island Rhinplatte in the vicinity of the town of Glückstadt (SH), i.e. some 100 km upstream in the River Elbe in 1993. Here, we include another record recovered from an unequivocal newspaper report: a 5 m individual found on the island of Föhr (SH) in 1905 (Neue Hamburger Nachrichten, 17 August 1905) (Figure 7).

Fig. 7. Records of beluga whales, narwhals, Sowerby's beaked whales and northern bottlenose whales.

Although the beluga whale is an arctic coastal species, during certain periods invasions seem to take place into more southern coastal waters, namely also the North Sea. In 1984 an individual swam up the River Elbe near Hamburg, and subsequently appeared in the Jadebusen and Dollart at the mouth of the River Ems (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Kinze and Sørensen1987; Goethe, Reference Goethe1996). Already in 1967, another beluga had swum 400 km up the Rhine to Bad Honef (Gewalt, Reference Gewalt1976).

There is a very doubtful old record of the species from the River Elbe near Hamburg for the year 1736. The only source here seems to be Mohr (Reference Mohr1935) who quoted Japha (1919 sic!; a reference not contained in her reference list) to have quoted Klein (Reference Klein1741) for this record, but Klein reported on a 1736 narwhal only. Schultz (Reference Schultz1970) as well lists a beluga for this year with reference to another Mohr paper (Reference Mohr1962) which, however, again only refers to a narwhal. This record therefore has been deleted from the list.

Narwhal (Monodon monoceros Linnæus. 1758)

There are two historical records of the narwhal, one from the Dollart in 1669 (SW, NI; Hartmann 1930) and another from 1736 and the mouth of the River Oste, a tributary to the Elbe (R Elbe, NI; Klein, Reference Klein1741. Mohr, Reference Mohr1931, Reference Mohr1962) (Figure 7).

Mohr (Reference Mohr1931) at first believed that two individuals had been taken during 1736, but in 1935 she considered only a single occurrence of a male in early February of this year. Donndorff (Reference Donndorff1792) on the other hand provided a different month (December) and Tomelin (Reference Tomelin1967) reported the specimen to be female. Recently, Haelters et al. (Reference Haelters, Kerckhof, Doom, Evans, Van den Neucker and Jauniaux2018) reviewed extralimital occurrences of the species in the North Sea.

Sowerby's beaked whale (Mesoplodon bidens (Sowerby, 1800))

Records of this species have been extremely rare with only four finds from the German North Sea coast (Figure 7). The two earliest finds are both from the island of Sylt: 1962 Rantum and 1970 Morsum (Schultz, Reference Schultz1970; Kühlemann, Reference Kühlemann1983). In 2009, there were two reports of the species from two adjacent localities, but in different federal states. Careful analysis of photographs documents them as two independent records. Also, during 2009 there were two North Sea live strandings: first 13 August on the English coast near Blakeney Point on the northern shores of Norfolk (which subsequently was found dead), then later 4 October 2009 on the Dutch coast near Masvlaake. The latter specimen was not re-encountered and may be identical with one of the German North Sea strandings.

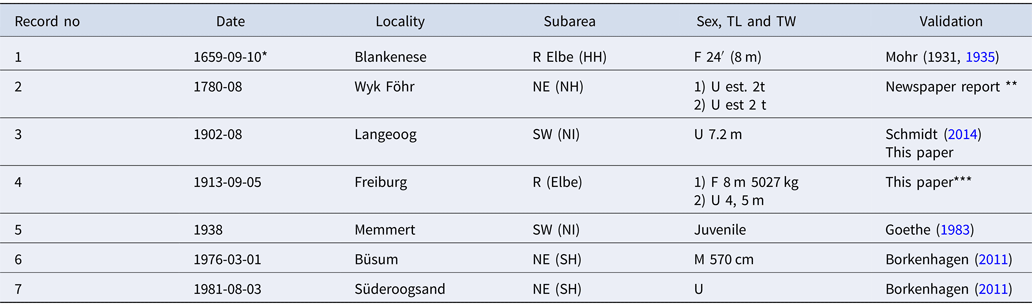

Northern bottlenose whale (Hyperoodon ampullatus Forster, 1770)

This large beaked whale was recorded seven times (Figure 7) comprising nine individuals in total. For the year 1659, Mohr (Reference Mohr1935) reported on the earliest bottlenose whale find from Blankenese on the banks of the River Elbe to the west of Hamburg. To this we add from the island of Föhr (SH) a catch of two individuals during the summer of 1780 (Danish newspaper report Kiøbenhavns Kongelig alene priviligerede Adresse-Contoirs Efterretninger, 9 August 1780). The species identity of the latter record rests on the vernacular Danish, German and Dutch names applied, the size of the two individuals, the season of the catch and the obvious reference to the bottlenose whale account delivered by Chemnitz (Reference Chemni(t)z1779).

Marshall (Reference Marshall1896) listed it as one of the more commonly occurring species and mentioned several contemporaneous finds (i.e. the 1890s) exhibited in public, but unfortunately without providing any details. Recently, an additional find from the early 20th century has been identified from a photograph and newspaper reports of an individual stranded on Langeoog (NI) in 1902 (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2014, Neue Hamburgsche Zeitung, 28 August 1902).

For the year 1913 a well-known find from Freiburg (upon Elbe, NI) hitherto erroneously was considered a stranding of a single male. Correctly the incident, however, instead involved a mother-calf pair (Neue Hamburger Zeitung 13 September 1913). A single record is known from Memmert (NI) in 1938 (Goethe, Reference Goethe1983). In 1976 there was a stranding near Büsum (SH) and another in 1981 from Süderoogsand (SH) (Borkenhagen, Reference Borkenhagen2011).

Sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus L. 1758)

Due to the immense size of this toothed whale, sperm whale strandings can be traced back in time further than any other large cetacean. The earliest known German North Sea sperm whale stranding dates back to 1604. In total, 21 strandings of at least 59 individuals have been documented (Figure 8). Here we include a hitherto overlooked sperm whale stranding from the Eider estuary from early 1695. Subsequent strandings have occurred in the 18th century in 1721, 1723 (18 animals), 1738 (3 animals), 1751 (3 animals, scattered), 1759 (2 animals) and 1762 (≥2 animals). From the 19th century there are no safe records. A presumed sperm whale stranding from 1848 on the island of Borkum (Vanselow & Ricklefs, Reference Vanselow and Ricklefs2005) did not meet the criteria for an unequivocal species identification and was not included in the list compiled by Smeenk & Evans (Reference Smeenk and Evans2018).

Fig. 8. Records of sperm whales.

The gap in records between 1762 and 1969 for the German North Sea strandings is in accordance with findings from the entire North coastline. Smeenk & Evans (Reference Smeenk and Evans2018) reviewed sperm whale stranding for the entire North Sea area while Pierce et al. (Reference Pierce, Santos, Smeenk, Saveliev and Zuur2007) proposed a relationship between strandings and fluctuations in sea temperature.

Minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata Lacepede, 1804)

The minke whale was documented 16 times in total between 1669 and 2017 (Figure 9). For the period 1990–2017 it ranked the most commonly encountered baleen whale with an overwhelming preponderance for the NE (SH) coastline. Records from the SW (NI) coastline include Beichle et al. (Reference Beichle, Stede and Pasenau2005).

Fig. 9. Records of minke and sei whales.

The species was originally known as the Balaena rostrata of Fabricius, 1780, but has frequently been confused with its homonym Balaena rostrata, Müller, 1776, a junior synonym of the northern bottlenose whale. Therefore, Poppe (Reference Poppe1882) erroneously listed an undisputable minke whale of 1669 (a life-size oil painting in the town hall of Bremen; Goethe, Reference Goethe1983) as a bottlenose whale.

Prior to 1971, the only German record known for this species originated from Leesum, the River Weser and the year 1669 (Goethe, Reference Goethe1983). Here, a record from Hooksiel and the 1830s originally considered a fin whale (Wiepken & Greve Reference Wiepken and Greve1876), we re-assign to minke whale. Mohr (Reference Mohr1935) reported a ‘fin whale suckling’ on exhibit in Hamburg in early 1932. This animal stranded near Cuxhaven at the mouth of the River Elbe and was reported to be 7–8 m in length. Based on newspaper photographs (e.g. in Der gerade Weg, 3 April 1932) we re-identify it as a minke whale.

Sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis Lesson, 1828)

Only two records of this species were documented from the German North Sea coastline: in 1955 on the island of Norderney (NI) (Goethe, Reference Goethe1983) and recently in 2016 near Blexen (NI) at the mouth of the River Weser (Figure 9).

Due to its pelagic habitat the sei whale is a very rare visitor to the shallow parts of the North Sea. However, further sei whale specimens may be found among collected rorqual specimens 7–10 m in length that were entered to scientific collections under an incorrect species heading. The 2016 Blexen specimen was identified morphologically (baleen colour) and molecularly (DNA analysis) to sei whale (Ralph Tiedemann, pers. com.).

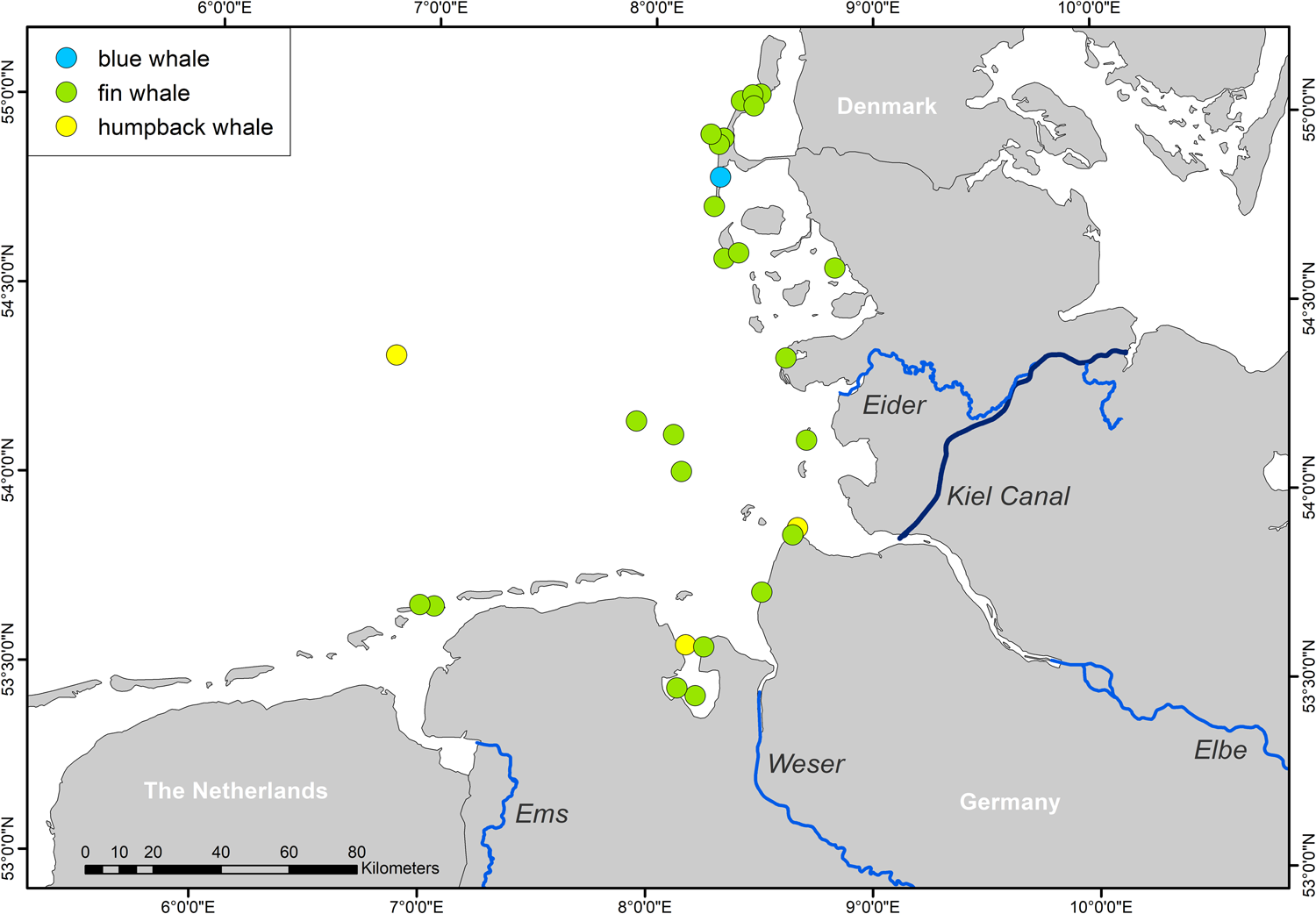

Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus (Linnæus, 1758))

Twenty-one fin whale records have been documented, spanning from 1827–2012 (Figure 10) indicating a preponderance in occurrence on the Sylt coasts (SH) (N = 8) and among these finds for the List Deep between the islands of Sylt and Rømø (Denmark).

Fig. 10. Records of fin, blue and humpback whales.

Unfortunately, the fin whale was known by both the German vernacular names ‘Nordkaper’ and ‘Grönländischer Wal’, also being in use for the North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) and the Greenland right whale or bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus), and even the killer whale (Orcinus orca) thereby causing a lot of confusion (see above). In the 18th century fin whales were listed under the species heading Balaenoptera musculus (Companyo Reference Companyo1830) therefore in later reviews (e.g. Schultz, Reference Schultz1970) erroneously were considered records of blue whale.

Here, we establish the correct species assignment of a 75-feet female ‘Walfisch’ from the island of Helgoland found in November 1849 to be a fin whale (archival evidence: Claudius in lit., 28 August 1857 to J. H. Blasius; Appendix 1). This stranding was erroneously considered a record of Balaena mysticetus, the Greenland right whale by von Dalla Tore (Reference von Dalla Torre1889) based on Oetker (Reference Oetker1855). Mohr (Reference Mohr1931) after Dahl (Reference Dahl1894, Reference Dahl1906) gave the year as 1805 (an obvious printing error for 1850) for the same incident.

Of Wiepken & Greve's (Reference Wiepken and Greve1876) two records of fin whale (Hooksiel 1830s, Wilhelmshaven 1870), only the latter record could be validated as belonging to the species while the Hooksiel record has been re-identified as minke whale. Newspaper reports revealed a further two fin whale strandings near Cuxhaven for the year 1882, and the species has also been documented from the island of Sylt in 1911 by Mohr (Reference Mohr1931).

Both World War I and II unfortunately produced fin whale casualties due to collisions with sea mines. During August 1915, another two large baleen whales, possibly fin whales, washed ashore on the west coast of Amrum (SH) and the island of Pellworm (SH), respectively. A possible third fin whale stranding occurred in July 1943 as a ‘headless’ rorqual was found on the Juister Riff (NI).

Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus (Linnæus, 1758))

For the German North Sea coastline, the blue whale still only has been encountered once in 1881 on the island of Sylt (SH) (Möbius, Reference Möbius1885) (Figure 10).

While the fin whale during the latter half of the 19th century unfortunately was known as Balaenoptera musculus (Companyo Reference Companyo1830) a homonym of the present day scientific name of the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus (Linnæus, 1758), the blue whale during the same period carried a variety of scientific names including Sibbaldius borealis Gray 1864 and Pterobalaena gigas Van Beneden 1861. Some 19th century records of ‘Balaenoptera musculus’ in literature therefore refer to fin whales instead and sometimes even are listed twice, both correctly as fin whales and incorrectly as blue whales (e.g. Schultz, Reference Schultz1970).

Further, Meyer (Reference Meyer1994) erroneously reported a minke whale as ‘blue whale’. This stranding supposedly occurred on the island of Neuwerk on12 December 1984, but indeed it is identical with a find the previous day on exactly the same location of a minke whale.

From the adjacent North Sea there are just three additional validated records: a Belgian (1827) and a Dutch (1840) one (Smeenk & Camphuysen, Reference Smeenk, Camphuysen, Broekhuizen, Spoelstra, Thissen, Canters and Buys2016c) and a single 1907 record from the Danish North Sea coast (Kinze, Reference Kinze, Baagøe and Jensen2007).

Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae (Borowskii, 1791))

The humpback whale was reported thrice only, in 1824 at the mouth of River Elbe (Mohr, Reference Mohr1935) and a single specimen, 1991 in the Jade inlet, and in 1994 an individual floating in the German Bight (Stede et al., Reference Stede, Lick and Benke1996) (Figure 10).

Discussion

As compared with adjacent coastlines, the lower cetacean diversity (Table 2) encountered in the German Bight may be explained by the hydrographic conditions possibly favouring species with coastal affinity and adaptability. The riverine habitat has been exploited by both the harbour porpoise and the bottlenose dolphin, but with increasing riverine pollution throughout the 20th century these visits ceased. However, the successful return of the harbour porpoise to these rivers also may be a precursor to the reappearance of the bottlenose dolphin. So far records of bottlenose dolphin are documented for the southernmost part of the German North Sea coast and may be an inclusive part of the Dutch distributional scenario with stragglers occurring only. Along the northern English North Sea coastline bottlenose dolphins from Scotland have recently expanded their range further south (Stockin et al., Reference Stockin, Weir and Pierce2006; Evans & Waggitt, Reference Evans, Waggitt, Crawley, Coomber, Kubasiewicz, Harrower, Evans, Waggitt, Smith and Mathews2020).

Table 2. Strandings of non-phocoenid cetaceans (number of individuals) along the Dutch, German and Danish North Sea coasts for the period 1990–2017

Sources: NL: Smeenk, Reference Smeenk1995, Reference Smeenk2003, Camphuysen et al., Reference Camphuysen, Smeenk, Addink, van Grouw and Jansen2008, Keijl et al., Reference Keijl, Begeman, Hiemstra, Ijsseldijk and Kamminga2016 and www.walvistrandingen.nl. DK: Kinze, Reference Kinze1995, Kinze et al., Reference Kinze, Tougaard and Baagøe1998, Reference Kinze, Jensen, Tougaard and Baagøe2010 and Reference Kinze, Thøstesen and Olsen2018.

Historically, all cetaceans encountered in the German part of the North Sea other than the harbour porpoise over-simplified were lumped into a single category of presumed erratic species. However, they constitute a rather heterogeneous group of species with very different potentials to adapt to the hydrographic regime of the larger German Bight. So-called ‘neighbourhood species’ include frequently reported white-beaked dolphins and minke whales while sperm whales and other pelagic cetaceans are purely erratic species (Gosselck & Kinze, Reference Gosselck and Kinze2011). Hence, coastal and shelf species from southern and northern areas may adapt to environmental conditions and altered sources of food. On the other hand, oceanic or pelagic species are challenged by their lack of resilience to the coastal habitat and may even face shortcomings of their orientation and navigation capacities.

Historical context

Several German scholars of the late 18th and early 19th century have pointed out the lack of knowledge on cetaceans occurring along the German coasts in particular and the North Sea coastline in general (Blasius, Reference Blasius1857). These treatises therefore in many ways provided a generalized picture drawn from adjacent, in many cases Dutch, waters – thereby listing cetacean species assumed to occur or expected to appear in German waters. The literature containing information on historical cetacean strandings is rather scattered, reflecting the historical administrative division of present-day Germany into then several independent states. The species assignment sometimes relied on inadequate literature and was in several cases found incorrect. Even the most recent reviews by Schultz (Reference Schultz1970) and Goethe (Reference Goethe1983) contain misinterpretations and double counts (see above).

The present federal state Schleswig-Holstein until 1864 was part of the Danish monarchy which is why several older reports on cetacean strandings are written in the Danish language. After a transition period, SH became a province of Prussia in 1867. Subsequent literature on 19th century cetacean records from the North Sea coast comprise the works of Möbius (Reference Möbius1873, Reference Möbius1885) and Dahl (Reference Dahl1894, Reference Dahl1906) while Mohr (Reference Mohr1931, Reference Mohr1935) provided the first comprehensive compilation but also introduced several errors, as did Schultz (Reference Schultz1970). Borkenhagen (Reference Borkenhagen2011) listed and corrected records to the year 2010. Also, certain ‘border cases’ were removed from the list since they took place on the present-day Danish coast and already have been treated elsewhere (Kinze, Reference Kinze1995).

The present Federal State of Niedersachsen was only formed in 1945, merging the coastal areas of the Prussian province of Hannover and the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg into a single entity and hence older literature on cetaceans covered only certain portions of the present coastline.

For the present-day Federal States of Hamburg and Bremen information on cetacean records are found in Itzerodt (Reference Itzerodt1904) and Heineken (Reference Heineken1837), respectively.

Harbour porpoise

The period 1990–2017 in adjacent Dutch waters (Smeenk Reference Smeenk1995, Reference Smeenk2003; Camphuysen et al., Reference Camphuysen, Smeenk, Addink, van Grouw and Jansen2008; Keijl et al., Reference Keijl, Begeman, Hiemstra, Ijsseldijk and Kamminga2016) yielded 8444 specimens. The Dutch figures do indicate a very high reporting effort along with a marked increase in occurrence resembling the SW (NI) German figures while the NE (SH) figures seem to fluctuate with no clear trend.

Other species

For the entire German North Sea coastline and the period 1990–2017, 120 specimens of 14 non-phocoenid species were documented while the Dutch coast yielded 215 specimens of 15 and the Danish coast 213 of 11 species. The German coastline exhibited the lowest number of specimens as well as the lowest encounter rate with about 10 finds per 100 km coastline while for the Dutch and Danish coasts a much higher encounter rate could be noted with nearly 48 finds per 100 km and 35 finds per 100 km, respectively and each above 200 specimens. (Table 2). The white-beaked dolphin was the most frequently encountered species along all three coastlines with 38.3%, 54.9% and 58.6% of the finds from the German, Danish and Dutch coasts, respectively. Sperm whales accounted for 22.5%, 19.7% and 12.1%, respectively. Figures for the minke whale were 7.5%, 10.4% and 8.4%, respectively (Table 2). White-beaked dolphins predominate in the northern parts of the North Sea while common dolphins range into its southern parts (MacLeod et al., Reference MacLeod, Bannon, Pierce, Schweder, Learmonth, Herman and Reid2005). So far along the German North Sea coast, the white-beaked dolphin has kept position as the most common delphinid, but due to evident climate changes shifts in species frequency are to be expected and rising sea temperatures could push white-beaked dolphins further north and away from the German North coastline and instead attract more common dolphins, although these two species do not share the same ecological preference (Evans & Waggitt, Reference Evans, Waggitt, Crawley, Coomber, Kubasiewicz, Harrower, Evans, Waggitt, Smith and Mathews2020). Common dolphins, being indicative for a warmer climate, have also occurred in earlier periods in the southern North Sea (Fraser, Reference Fraser1937).

Striped dolphins are both pelagic and southern indicators. Their occurrence along the German North Sea coast has been recorded just once so far. There have been several finds along the English and Dutch coasts, generally in increasing numbers since 1967 (Ijsseldijk et al., Reference Ijsseldijk, van Neer, Deaville, Begeman, van de Bildt, van den Brand, Brownlow, Czeck, Dabin, ten Doeschate, Herder, Herr, IJzer, Jauniaux, Jensen, Jepson, Jo, Lakemeyer, Lehnert, Leopold, Osterhaus, Perkins, Piatkowski, Prenger-Berninghoff, Pund, Wohlsein, Gröne and Siebert2018a, Reference Ijsseldijk, Brownlow, Davison, Deaville, Haelters, Keijl, Siebert and ten Doeschate2018b).

The killer whale is a rare visitor to the German North Sea coastline with no clear trend in occurrence. Within the northern sectors of the North Sea killer whales have continuously been present for decades (Evans & Waggitt, Reference Evans, Waggitt, Crawley, Coomber, Kubasiewicz, Harrower, Evans, Waggitt, Smith and Mathews2020). The white-sided dolphin had its first appearance on the SW (NI) coast already in 1968 and may be considered a northern pelagic intrusion. Possibly the freshwater output within the German Bight has led to finds only outside the river mouths, i.e. further to the west and to the north.

The beluga whale is a coastal Arctic species with a high riverine affinity. As in adjacent waters this species exhibits a low stranding mortality with much more frequent sightings and live strandings than finds of dead specimens. In 1983 for instance, the entire German North Sea coastline for weeks was visited by a single beluga whale (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Kinze and Sørensen1987; Goethe Reference Goethe1996) without a lethal stranding incident. During periods, e.g. 1903–1908 (Schultz, Reference Schultz1970) there have been extralimital intrusions of beluga whales into temperate waters. The rediscovered find from the island Föhr and the year 1905 falls into the same period while the find from the River Elbe is supportive for the riverine affinity of the species. The narwhal is a high Arctic pelagic species for which there are only historic records. From Dutch, English and Belgian North Sea waters more recent finds are known (Weber, Reference Weber1912; Fraser, Reference Fraser1949; Haelters et al., Reference Haelters, Kerckhof, Doom, Evans, Van den Neucker and Jauniaux2018).

Genuine oceanic species such as the teuthophageous sperm whale, northern bottlenose whale and Sowerby's beaked whale may find little food along the German North Sea coast. In addition, their navigation capacities may run short. None the less, ziphiid species are known to enter rivers and venture upstream. For the Thames estuary and river at least six such occurrences of northern bottlenose whales have been documented (Crouch, Reference Crouch1891; Deaville & Jepson, Reference Deaville and Jepson2007) that may mirror the occurrences in the River Elbe (1659, 1913).

Among the baleen whales there is a high preponderance of fish-eating species (minke, fin and humpback). The minke whale is a rather stable fauna component in the northern and central North Sea but has also become the most frequent rorqual in the German North Sea stranding record. The species may have benefited from the intense exploitation of the larger piscivorous baleen whales such as the fin whale and the humpback whale. The fin whale seems to have been a foraging visitor along the NE (SH) coast, with occurrences in the deeps between the islands. The humpback populations of the North Atlantic experienced a heavy exploitation in the 19th and 20th century but now seem to have undergone a full recovery with few but regular sightings off the Dutch coast (Leopold et al., Reference Leopold, Rotshuizen and Evans2018) and accordingly again records from the German North Sea coast.

Acknowledgements

Details of strandings data were extracted from databases held at Landesmuseum Natur und Mensch, Oldenburg, Niedersächsisches Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit, Cuxhaven and Seehundstation und Nationalpark-Haus, Norden (RC) while the Schleswig-Holstein data directly was made available by US.

The holdings of the collections in Frankfurt (Senckenberg Museum), and Stuttgart (Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart) were accessed over their websites (CCK). Details of specimens held in the scientific collections of the museums in Oldenburg were provided to RC.

Access to the scientific collection in Berlin (Museum für Naturkunde), Hamburg (Zoologisches Museum, University of Hamburg) and Kiel (Zoologisches Museum, Christian Albrechts University) was granted by Nora Lange, Thomas Kaiser and Dirk Brandis, respectively (CCK).

Special thanks to Volker Lautenbach for providing photographs of a Sowerby's beaked whale on Minsener Oog to RC and to two anonymous reviewers for comments improving the contents of this paper.

Authors contribution

CCK Conducted the overall compilation and analysis, drafted the manuscript, provided historical records from literature and archives. RC provided recent records from Niedersachsen and photographic documentation. HH designed the distribution maps. US initiated the work and provided recent records from Schleswig-Holstein and photographic documentation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Appendix 1

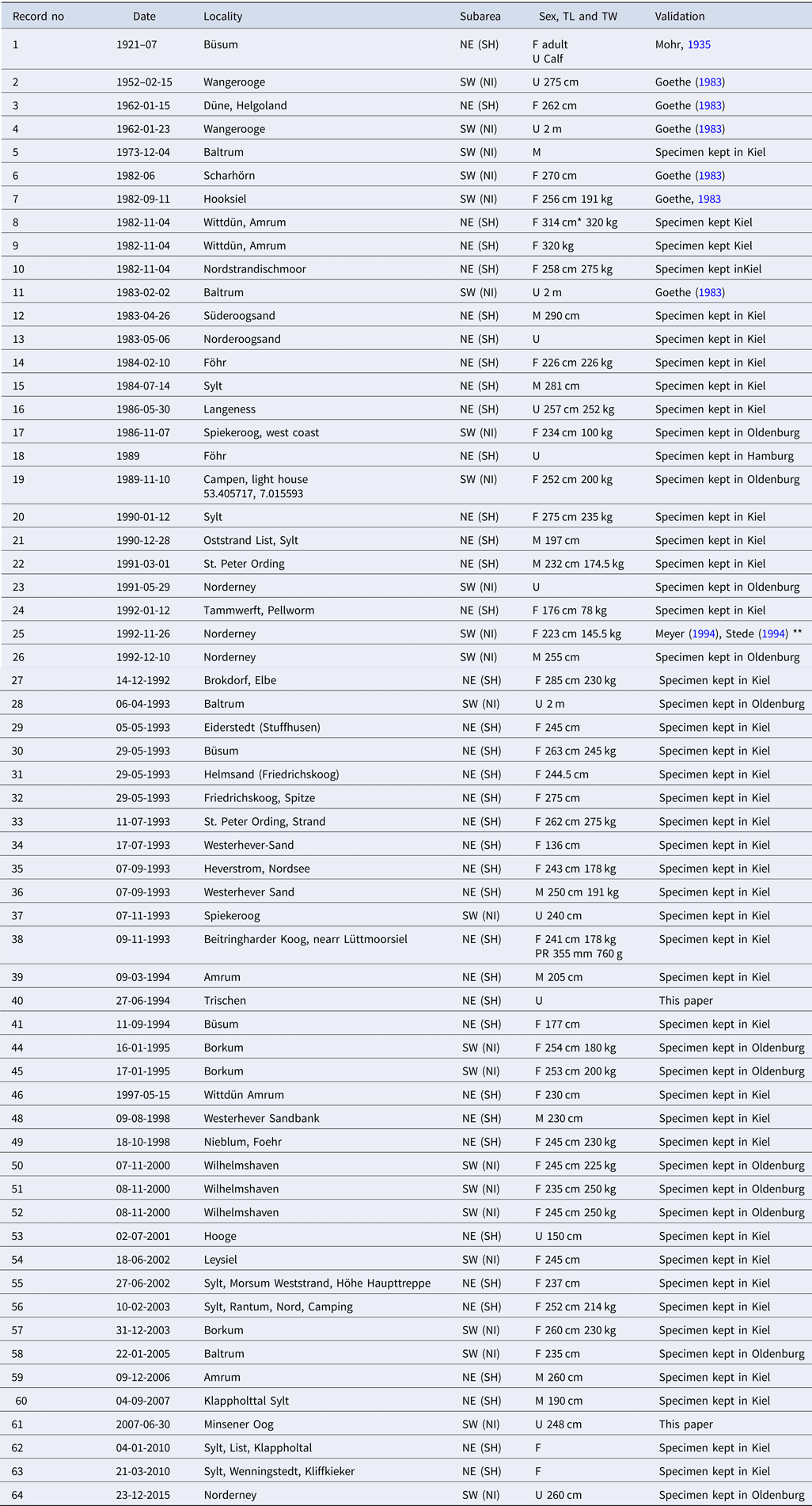

Record details. Date given in format YYYY-MM-DD. Sex M, male; F, female; U, sex unknown; TL, total length; TW, total weight; PR, pregnant.

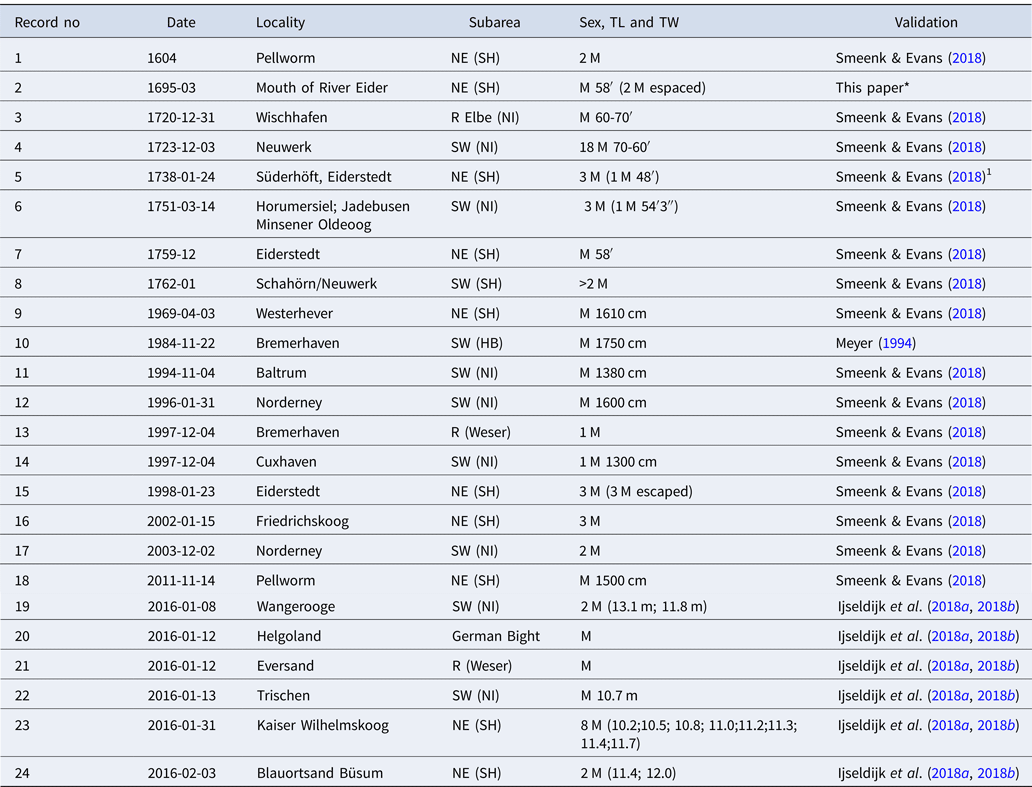

White-beaked dolphin (Lagenorhynchus albirostris Gray, 1846)

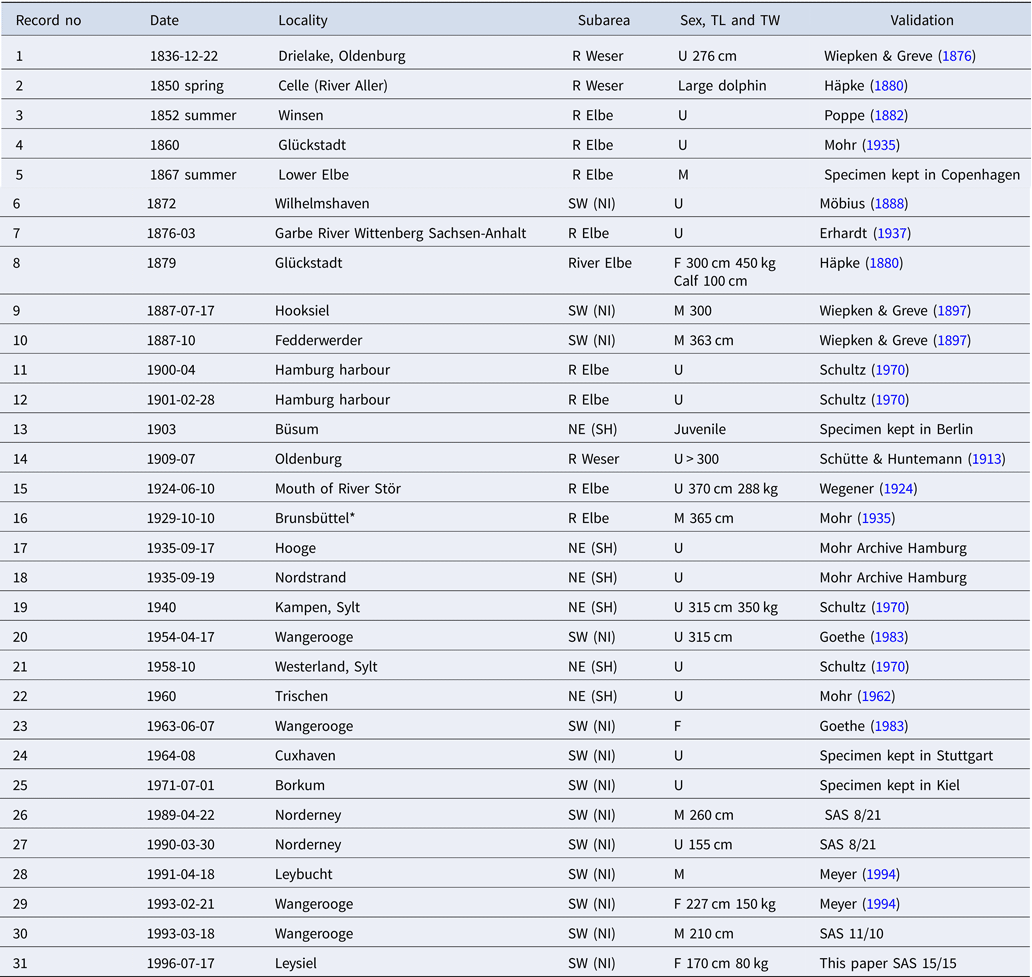

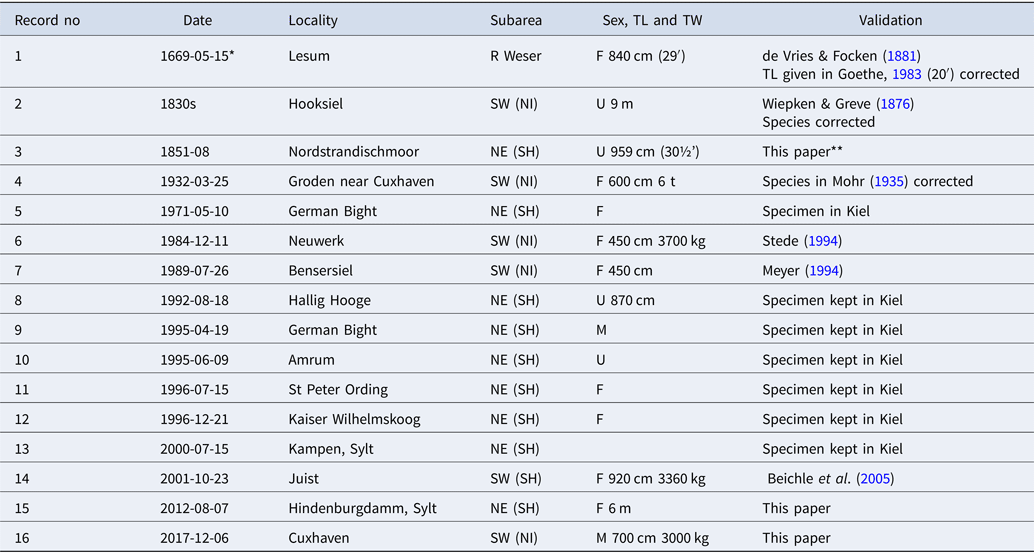

Bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus (Montagu, 1821))

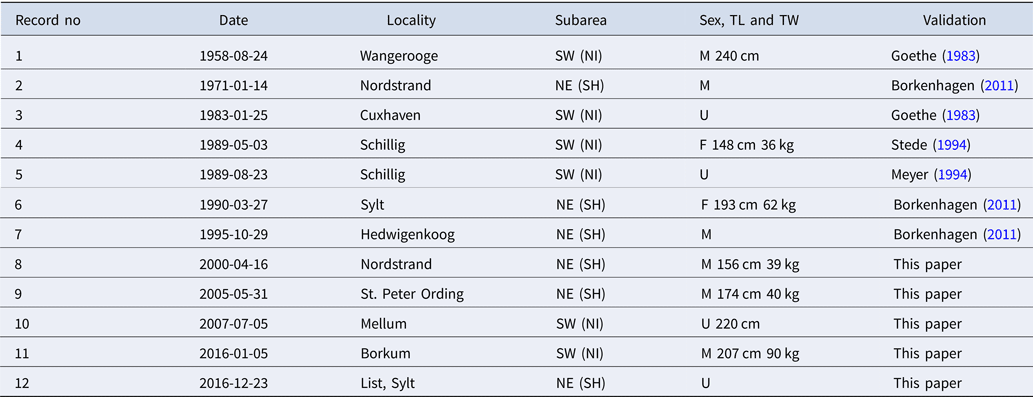

White-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus acutus (Gray, 1828))

Common dolphin (Delphinus delphis Linnæus, 1758)

Striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba (Meyen, 1833))

Risso's dolphin (Grampus griseus (Cuvier, 1812))

Longfinned pilot whale (Globicephala melas (Traill, 1809))

Killer whale (Orcinus orca (Linnæus, 1758))

Beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas (Pallas, 1770))

Narwhal (Monodon monoceros Linnæus, 1758)

Sowerby's beaked whale (Mesoplodon bidens (Sowerby, 1800))

Northern bottlenose whale (Hyperoodon ampullatus Forster, 1770)

Sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus L. 1758)

Minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata Lacepede, 1804)

Sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis Lesson, 1828)

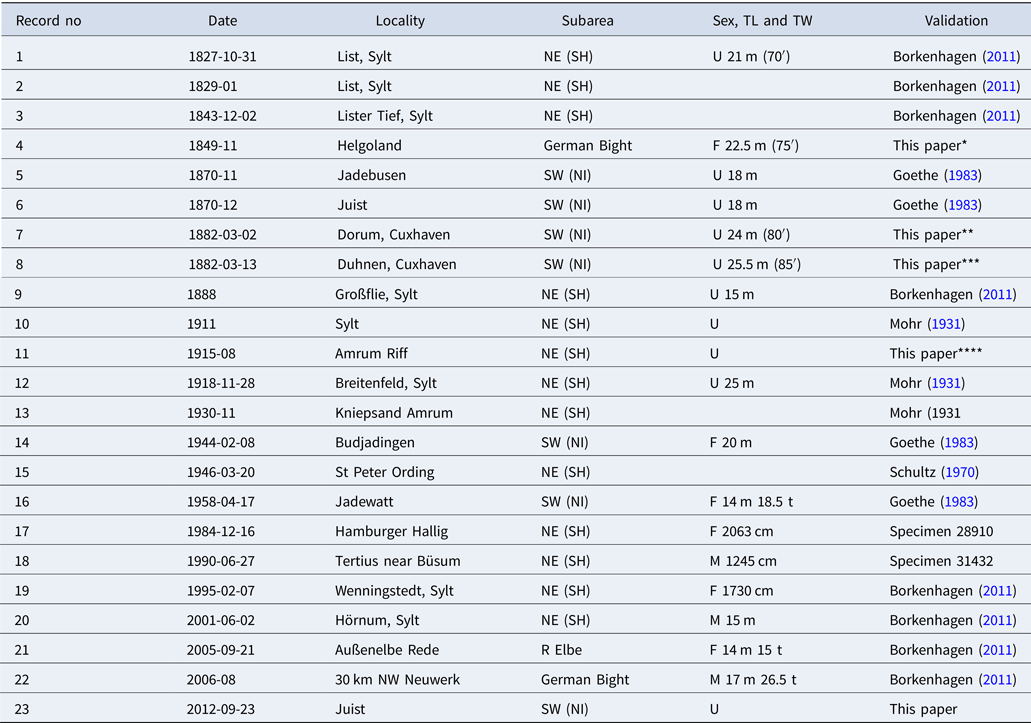

Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus (Linnæus, 1758))

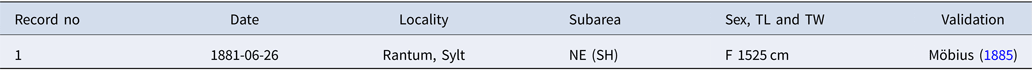

Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus (Linnæus, 1758))

Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae (Borowskii, 1791))