The variety described here is Pontic Greek (ISO 639 name: pnt), and specifically the variety that originates from Trapezounta in Asia Minor (present-day Trabzon in Turkey) as spoken today in Etoloakarnania, Greece by second-generation refugees. The term ‘Pontic Greek’ (in Greek: ![]() ) was originally an etic term, while Pontians called their language by other names, mainly [ɾoˈmeika]

) was originally an etic term, while Pontians called their language by other names, mainly [ɾoˈmeika] ![]() ‘Romeika’ (Sitaridou Reference Sitaridou2016) but also [laziˈka]

‘Romeika’ (Sitaridou Reference Sitaridou2016) but also [laziˈka] ![]() ‘Laz language’ (Drettas Reference Drettas1997: 19, 620), even though Pontians and Laz people do not share the same language, the latter being Caucasian. Nowadays,

‘Laz language’ (Drettas Reference Drettas1997: 19, 620), even though Pontians and Laz people do not share the same language, the latter being Caucasian. Nowadays, ![]() is the standard term used not only by researchers, but also by native speakers of Pontic Greek born in Greece to refer to their variety (but see Sitaridou Reference Sitaridou, Jones and Sarah2013 for Romeyka in the Black Sea). Pontic Greek belongs to the Asia Minor Greek group along with other varieties, such as Cappadocian Greek (e.g. Horrocks Reference Horrocks2010: 398–404; Sitaridou Reference Sitaridou2014: 31). According to Sitaridou (Reference Sitaridou2014, Reference Sitaridou2016), on the basis of historical reconstruction, the Pontic branch of Asia Minor Greek is claimed to have been divided into two major dialectal groups: Pontic Greek as spoken by Christians until the 20th century in Turkey and Romeyka as spoken by Muslims to date in Turkey. Triantafyllidis (1938/Reference Triantafyllidis1981: 288) divides Pontic varieties, as were spoken in Asia Minor, into three dialectal groups, namely Oinountian, Chaldiot, and Trapezountian, the latter consisting of the varieties that were spoken at Trapezounta, Kerasounta, Rizounta, Sourmena, Ofis, Livera, Tripolis, and Matsouka in Asia Minor (Trabzon, Giresun, Sürmene, Of, Yazlık, Tirebolu, and Maçka respectively in present-day Turkey). However, Triantafyllidis does not explain his criteria for this classification (Chatzissavidis Reference Chatzissavidis and Gavras2012). According to one other classification (Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos1955: 17–18; Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos1958:

is the standard term used not only by researchers, but also by native speakers of Pontic Greek born in Greece to refer to their variety (but see Sitaridou Reference Sitaridou, Jones and Sarah2013 for Romeyka in the Black Sea). Pontic Greek belongs to the Asia Minor Greek group along with other varieties, such as Cappadocian Greek (e.g. Horrocks Reference Horrocks2010: 398–404; Sitaridou Reference Sitaridou2014: 31). According to Sitaridou (Reference Sitaridou2014, Reference Sitaridou2016), on the basis of historical reconstruction, the Pontic branch of Asia Minor Greek is claimed to have been divided into two major dialectal groups: Pontic Greek as spoken by Christians until the 20th century in Turkey and Romeyka as spoken by Muslims to date in Turkey. Triantafyllidis (1938/Reference Triantafyllidis1981: 288) divides Pontic varieties, as were spoken in Asia Minor, into three dialectal groups, namely Oinountian, Chaldiot, and Trapezountian, the latter consisting of the varieties that were spoken at Trapezounta, Kerasounta, Rizounta, Sourmena, Ofis, Livera, Tripolis, and Matsouka in Asia Minor (Trabzon, Giresun, Sürmene, Of, Yazlık, Tirebolu, and Maçka respectively in present-day Turkey). However, Triantafyllidis does not explain his criteria for this classification (Chatzissavidis Reference Chatzissavidis and Gavras2012). According to one other classification (Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos1955: 17–18; Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos1958:

![]() $\upzeta$

), the variety that was used in Trapezounta belongs to the dialectal group in which post-stressed /i/ and /u/ delete along other varieties, such as e.g. the ones that were spoken in Chaldia (present-day Gümüşhane), Sourmena, and Ofis (as opposed to the rest of Pontic varieties, such as the one of Kerasounta, in which those vowels are retained). Trapezountian Pontic Greek can also be classified with the group of varieties that retain word-final /n/, such as the varieties of Kerasounta and Chaldia, as opposed to the varieties that do not retain it, such as the ones of Oinoe (present-day Ünye) and (partially) Ofis (Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos1958: θ).

$\upzeta$

), the variety that was used in Trapezounta belongs to the dialectal group in which post-stressed /i/ and /u/ delete along other varieties, such as e.g. the ones that were spoken in Chaldia (present-day Gümüşhane), Sourmena, and Ofis (as opposed to the rest of Pontic varieties, such as the one of Kerasounta, in which those vowels are retained). Trapezountian Pontic Greek can also be classified with the group of varieties that retain word-final /n/, such as the varieties of Kerasounta and Chaldia, as opposed to the varieties that do not retain it, such as the ones of Oinoe (present-day Ünye) and (partially) Ofis (Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos1958: θ).

Until the 1920s, speakers of Pontic Greek lived in the Pontus region of northern Asia Minor, i.e. the Black Sea region of present-day Turkey. As a result of the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, a population exchange between Greece and Turkey took place in the 1920s, with Christian Pontians moving to various places in Greece (see Clogg Reference Clogg1992: 100ff.). According to the 1928 census, almost 163,000 Pontic refugees arrived in Greece (Drettas Reference Drettas1997: 18), while in the late 1990s the number of persons with an active command of Pontic Greek was estimated to be around 300,000 (Drettas Reference Drettas, Anastasios-Phoevos, Maria and Giannoula1999: 15). Even though one would expect a decrease in the number of Pontic Greek speakers in Greece due to assimilation to Standard Modern Greek, this increase reported by Drettas is due to waves of Pontic Greek speakers from (former) USSR: it is estimated that between 1965 and 1997 around 100,000 Pontic-Greek-speaking immigrants relocated in Greece (Vergeti Reference Vergeti, Michel and Vlassis1998). Today, the number of people of Pontic origin in Greece may have increased compared to the figures mentioned 20 years ago, but it is unclear how many actively use Pontic Greek and which variety precisely. The main areas in which populations of Pontic origin are found in Greece are Macedonia and Thrace (Chatzisavvidis Reference Chatzissavidis and Gavras2012). As regards Pontians originating from Trapezounta (present-day Trabzon), they are found in northern Greece as well, but also in the Etoloakarnania (see Kontoeidis Reference Kontoeidis1980) and Preveza prefectures: in the latter, villages such as Nea Kerasounta and Nea Sampsounta were founded (‘nea’ meaning ‘new’). Pontic Greek of Trapezountian origin as spoken today in Etoloakarnania is the topic of the present study.

For the purposes of this study, a female consultant (hereafter FC), who is a second-generation refugee born in Greece with origins from the city of Trapezounta, Asia Minor, was recorded. At the time of the recording (summer 2018), FC was 63 years old and reported no speech disorders. She grew up in the Mpampalio village in Etoloakarnania, Greece, one of the various centres with significant numbers of Pontic Greek speakers from Trapezounta. Her parents were native speakers of Trapezountian Pontic Greek, which they continued using after their settlement in Greece as the language of communication within extended family and also with other members of the network of Pontic Greek speakers in Mpampalio. Thus, FC acquired and used Trapezountian Pontic Greek as L1 along with Standard Modern Greek. Trapezountian Pontic Greek is the variety she uses as the language of communication with the family she created and with extended family as well. As expected, because of the long contact with the form(s) of Greek spoken in Greece (the standard and local Greek varieties), Pontic Greek has been changing in some respects, both because of the ongoing attrition towards Standard Modern Greek (more evident in younger generations) and also due to koineisation processes taking place after settlement in Greece, which involve levelling of Pontic Greek dialectal variation and the emergence of a Pontic Greek Koine (Chatzisavvidis Reference Chatzissavidis and Gavras2012, Sitaridou Reference Sitaridou2014). Notwithstanding, FC reported that dialectal differences within Pontic Greek are to a certain degree still maintained and recognised by its speakers, a claim though that needs to be empirically verified. In this study, the variety described is considered to be a continuation of the Pontic Greek variety as was spoken in Trapezounta, thus the term ‘Trapezountian Pontic Greek’; however, because, due to the above-mentioned factors, this variety must have been evolving as well, we will hereafter refer to it as ‘Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek’. For conducting the present study, FC was recorded reading a word list and the ‘North Wind and the Sun’ passage, which was translated into Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek by the paper’s fourth author, a third-generation speaker of this variety. His translation was checked by a second-generation speaker and by FC herself.

Figure 1 Map or the Etoloakarnania prefecture (shaded area) in Greece. Mpampalio village is indicated with a dark dot.

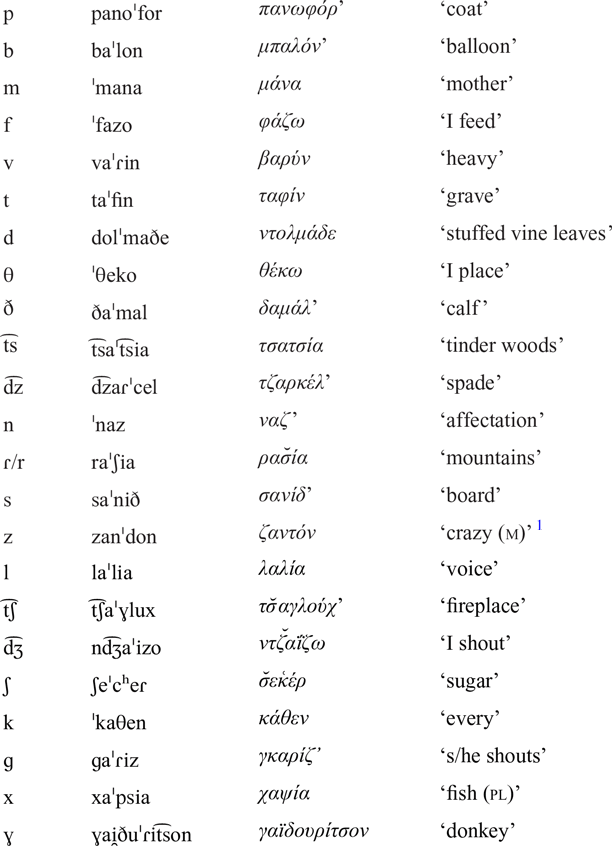

Consonants

Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek has 23 consonantal phonemes in its inventory.

Plosives

Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek plosives are of three places of articulation: (a) bilabial /p b/; (b) coronal /t d/ realised impressionistically as denti-alveolar [t̪ d̪]; and (c) the dorsal /k ɡ/ (see below for the velar vs. palatal realisation of the dorsal plosives). Voicing is contrastive for plosives, e.g. [do] ![]() ‘what’ vs. [to]

‘what’ vs. [to] ![]() ‘the.n.acc’ (see panel a and b respectively in Figure 2). The underlying voicing distinction is realised phonetically with negative VOT for the voiced plosives [b d ɡ ɟ] and with virtually zero VOT for the voiceless unaspirated plosives [p t k c]. A third VOT specification is also encountered, namely long positive VOT, for the voiceless aspirated plosives [pʰ tʰ kʰ cʰ]. Regarding this aspiration distinction, it is not considered by Drettas (Reference Drettas1997: Section 31) to be contrastive, as only one near minimal pair differing in aspiration can be found, namely [cʰ] vs. [c]: the former is the contracted form of the negation particle /kʰi/

‘the.n.acc’ (see panel a and b respectively in Figure 2). The underlying voicing distinction is realised phonetically with negative VOT for the voiced plosives [b d ɡ ɟ] and with virtually zero VOT for the voiceless unaspirated plosives [p t k c]. A third VOT specification is also encountered, namely long positive VOT, for the voiceless aspirated plosives [pʰ tʰ kʰ cʰ]. Regarding this aspiration distinction, it is not considered by Drettas (Reference Drettas1997: Section 31) to be contrastive, as only one near minimal pair differing in aspiration can be found, namely [cʰ] vs. [c]: the former is the contracted form of the negation particle /kʰi/ ![]() ‘not’, while the latter is the contracted form of the conjunction /ke/

‘not’, while the latter is the contracted form of the conjunction /ke/ ![]() ‘and’. For example:

‘and’. For example:

In this paper, we adopt Drettas’s analysis and do not consider aspiration to be phonemically contrastive. In our data too, it is not the case that aspirated and plain plosives are in complementary distribution, as no rule predicts their distribution. Even though FC was consistent in her production of aspirated plosives (something that arguably suggests that voiceless plosives are underlyingly specified for aspiration), the authors did informally observe that there is some inter-speaker variation and (especially with younger speakers) intra-speaker inconsistency regarding the plain vs. aspirated distinction. This issue requires a larger scale sociophonetic investigation in the future. Panel c in Figure 2 shows the first syllable of the word [tʰuˈlum] ![]() ‘bagpipe’ containing a word-initial aspirated [tʰ]; panel b shows the word [to]

‘bagpipe’ containing a word-initial aspirated [tʰ]; panel b shows the word [to] ![]() ‘def.n’ containing a word-initial unaspirated [t], while panel a shows the word [do]

‘def.n’ containing a word-initial unaspirated [t], while panel a shows the word [do] ![]() ‘what’ containing a word-initial voiced [d] with substantial prevoicing.

‘what’ containing a word-initial voiced [d] with substantial prevoicing.

Figure 2 Waveforms and spectrograms of three words beginning with plosives aligned at the onset of their burst. Panel (a): voiced ![]() of the word

of the word ![]() ‘what’. Panel (b): voiceless unaspirated

‘what’. Panel (b): voiceless unaspirated ![]() of the word

of the word ![]()

![]() ‘def.n’. Panel (c): voiceless aspirated

‘def.n’. Panel (c): voiceless aspirated ![]() of the word

of the word ![]() ‘bagpipe’.

‘bagpipe’.

Affricates

There are four affricates in Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek: the alveolars /t͡s d͡z/ and the laminal palatoalveolars /t͡ʃ d͡ʒ/. The phonemic status of the voiced affricates /d͡z/ and /d͡ʒ/ may be questioned by the fact that they often appear after a nasal, e.g. [n̠d͡ʒaˈizo] ![]() ‘I shout’, [ˈnd͡zid͡zifa]

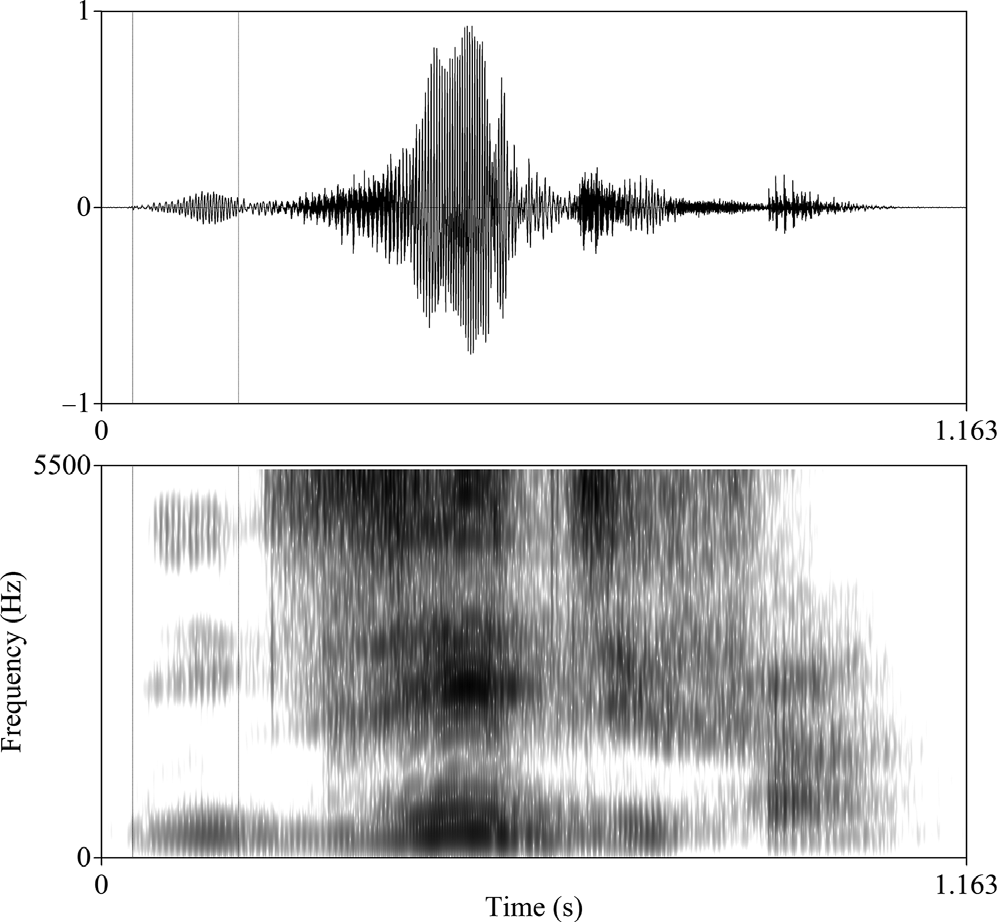

‘I shout’, [ˈnd͡zid͡zifa] ![]() ‘jujube fruits’. As the nasal + affricate sequences are encountered even word-initially, where the nasal cannot belong to a preceding morpheme or syllable, they could be alternatively analysed as presenalised segments, i.e. [ⁿd͡ʒ] and [ⁿd͡z], arguably in allophonic variation with [d͡ʒ] and [d͡z] (something that needs empirical verification with more data). Notwithstanding, the bisegmental analysis is not prohibited by their appearance in word-initial position, as such tautosyllabic nasal + affricate clusters are encountered in other Modern Greek varieties, such as Cypriot Greek (e.g. Arvaniti Reference Arvaniti1999b). Moreover, the productions of the subject of this study show rather long nasal portions before the affricate, something that points towards treating them as separate segments rather than prenasalisation. Figure 3, for instance, shows a fully-fledged word-initial nasal of around 140 ms in the word [ˈnd͡zid͡zifa]

‘jujube fruits’. As the nasal + affricate sequences are encountered even word-initially, where the nasal cannot belong to a preceding morpheme or syllable, they could be alternatively analysed as presenalised segments, i.e. [ⁿd͡ʒ] and [ⁿd͡z], arguably in allophonic variation with [d͡ʒ] and [d͡z] (something that needs empirical verification with more data). Notwithstanding, the bisegmental analysis is not prohibited by their appearance in word-initial position, as such tautosyllabic nasal + affricate clusters are encountered in other Modern Greek varieties, such as Cypriot Greek (e.g. Arvaniti Reference Arvaniti1999b). Moreover, the productions of the subject of this study show rather long nasal portions before the affricate, something that points towards treating them as separate segments rather than prenasalisation. Figure 3, for instance, shows a fully-fledged word-initial nasal of around 140 ms in the word [ˈnd͡zid͡zifa] ![]() ‘jujube fruits’.

‘jujube fruits’.

Figure 3 Waveform and spectrogram of the word ![]() ‘jujube fruits’. The selection lines enclose the initial nasal.

‘jujube fruits’. The selection lines enclose the initial nasal.

Regarding aspiration, it is reported (Drettas Reference Drettas1997: Sections 53f.) that the voiceless affricates are usually produced with aspiration, e.g. [t͡sʰeˈkur] ![]() ’ ‘axe’, [ˈt͡ʃʰanda]

’ ‘axe’, [ˈt͡ʃʰanda] ![]() ‘bag’. However, in our data, some words did appear systematically without aspiration, e.g.

‘bag’. However, in our data, some words did appear systematically without aspiration, e.g. ![]()

![]() ‘tinder woods’, [kaˈlat͡ʃeman]

‘tinder woods’, [kaˈlat͡ʃeman] ![]() ‘chat’. Further research is required in order to examine to what extent aspiration in the case of affricates is as systematically used as in the case of plosives.

‘chat’. Further research is required in order to examine to what extent aspiration in the case of affricates is as systematically used as in the case of plosives.

Nasals

There are two nasal phonemes in Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek: bilabial /m/ and alveolar /n/. Phonetically there are more variants of nasal consonants, as they agree in place of articulation with the following consonant, e.g. bilabial [m] as in [tombeˈðan] ![]() ‘def.m:acc boy:acc’; labiodental [ɱ] as in [siɱˈfeɾ]

‘def.m:acc boy:acc’; labiodental [ɱ] as in [siɱˈfeɾ] ![]() ‘it’s worthwhile’; dental [n̪] as in [ˈt͡ʃʰan̪d̪a]

‘it’s worthwhile’; dental [n̪] as in [ˈt͡ʃʰan̪d̪a] ![]() ‘bag’; alveolar [n] as in [ˈnd͡zid͡zifa]

‘bag’; alveolar [n] as in [ˈnd͡zid͡zifa] ![]() ‘jujube fruits’; palatoalveolar [n̠] as in [n̠d͡ʒaˈizo]

‘jujube fruits’; palatoalveolar [n̠] as in [n̠d͡ʒaˈizo] ![]() ‘I shout’; palatal [ɲ] as in [ˈeɲɟen]

‘I shout’; palatal [ɲ] as in [ˈeɲɟen] ![]() ‘s/he brought’; and velar [ŋ] as in [eneˈŋɡasta]

‘s/he brought’; and velar [ŋ] as in [eneˈŋɡasta] ![]() ‘I got tired’. Apart from assimilation to the following consonant, a palatal [ɲ] may result from synizesis (see below, towards the end of the ‘Consonants’ section).

‘I got tired’. Apart from assimilation to the following consonant, a palatal [ɲ] may result from synizesis (see below, towards the end of the ‘Consonants’ section).

Tap/Trill

The rhotic phoneme /ɾ/ is realised as a tap [ɾ] in most environments, e.g. [ɡaˈɾiz] ![]() ‘s/he shouts’, [t͡ʃʰaˈiɾ]

‘s/he shouts’, [t͡ʃʰaˈiɾ] ![]() ‘meadow’, [ˈaɣɾeos]

‘meadow’, [ˈaɣɾeos] ![]() ‘wild (m)’, [piɾˈʒʝas]

‘wild (m)’, [piɾˈʒʝas] ![]() ‘townsperson’. In word-initial position and sometimes in word-final position, it is realised as a trill [r], e.g. [raˈʃia]

‘townsperson’. In word-initial position and sometimes in word-final position, it is realised as a trill [r], e.g. [raˈʃia] ![]() ‘mountains’, [aˈŋɡur]

‘mountains’, [aˈŋɡur] ![]() ‘cucumber’. Word-initially, the trill may surface with an initial voiceless portion: [r̥͡raˈʃia]

‘cucumber’. Word-initially, the trill may surface with an initial voiceless portion: [r̥͡raˈʃia] ![]() ‘mountains’,

‘mountains’, ![]()

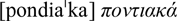

![]() ‘back (the body part)’. As shown in Figure 4, the onset of periodicity is delayed relatively to the onset of the initial trill of the [r̥͡raˈʃia] production.

‘back (the body part)’. As shown in Figure 4, the onset of periodicity is delayed relatively to the onset of the initial trill of the [r̥͡raˈʃia] production.

Figure 4 Waveform and spectrogram of the word ![]() ‘mountains’. The solid selection lines enclose the trill; the thin dashed line indicates the offset of the initial voiceless part of the trill.

‘mountains’. The solid selection lines enclose the trill; the thin dashed line indicates the offset of the initial voiceless part of the trill.

Fricatives

Fricative phonemes are of five places of articulation: labiodental /f v/, interdental /Θ ð/, alveolar /s z/, palatoalveolar /ʃ/, and dorsal /x ɣ/. The dorsal phonemes have two allophones, velar [x ɣ] and palatal [ç ʝ] (see below). The fricative [ʃ] can be the allophone of /s/ before /ke/ or /ki/, e.g. [ˈkʰloʃcete] ![]() ‘s/he turns’ (as opposed to [ˈkʰloskume]

‘s/he turns’ (as opposed to [ˈkʰloskume] ![]() ‘I turn’); it may also be the allophone of /x/ before a front vowel (see below). The voiced palatoalveolar fricative [ʒ] is considered to be an allophone of /z/ before synizesis, e.g.

‘I turn’); it may also be the allophone of /x/ before a front vowel (see below). The voiced palatoalveolar fricative [ʒ] is considered to be an allophone of /z/ before synizesis, e.g. ![]() ‘townsperson’. As is the case with Standard Modern Greek (Holton, Mackridge & Philippaki-Warburton Reference Holton, Mackridge and Philippaki-Warburton2004: 8–9), the voiced alveolar [z] can be the allophone of /s/ when followed by the voiced fricatives /v ð ɣ/ and the nasal /m/, e.g. [ˈlaizman]

‘townsperson’. As is the case with Standard Modern Greek (Holton, Mackridge & Philippaki-Warburton Reference Holton, Mackridge and Philippaki-Warburton2004: 8–9), the voiced alveolar [z] can be the allophone of /s/ when followed by the voiced fricatives /v ð ɣ/ and the nasal /m/, e.g. [ˈlaizman] ![]() ‘animal cry’.

‘animal cry’.

Lateral approximants

There is one lateral phoneme, /l/. Apart from its main realisation as a voiced alveolar lateral approximant [l], it is also realised as [ʎ] as a result of synizesis.

The palatal consonants of Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek

As is the case with Standard Modern Greek (Arvaniti Reference Arvaniti1999a: 3), the dorsal plosives /k ɡ/ and fricatives /x ɣ/ have two allophones in complementary distribution: the velar [k ɡ x ɣ] and the palatal [c ɟ ç ʝ]. The palatals appear before front vowels /i e/, while velars appear everywhere else, e.g. [ˈlikon] ![]() ‘wolf.nom’ vs. [ˈlice]

‘wolf.nom’ vs. [ˈlice] ![]() ‘wolf.voc’. Before front vowels, the voiceless dorsal fricative /x/ is realised either as a palatal [ç] or a palatoalveolar [ʃ], a variation which is lexically determined, e.g. [ˈçile]

‘wolf.voc’. Before front vowels, the voiceless dorsal fricative /x/ is realised either as a palatal [ç] or a palatoalveolar [ʃ], a variation which is lexically determined, e.g. [ˈçile] ![]() ‘lips’, but [eʃ]

‘lips’, but [eʃ] ![]() ‘s/he has’; in this last example the /x/ → [ʃ] derivation may be opaque, as the front vowel /i/ after the dorsal /x/ deletes (compare [ˈexo]

‘s/he has’; in this last example the /x/ → [ʃ] derivation may be opaque, as the front vowel /i/ after the dorsal /x/ deletes (compare [ˈexo] ![]() ‘I have’).

‘I have’).

Apart from the dorsal obstruents, the nasal phoneme /n/ also has velar and palatal allophones: when preceding the dorsal consonants /k ɡ x/, the nasal /n/ assimilates to their place of articulation, as mentioned above, e.g. [ˈeŋɡa] ![]() ‘I brought’, but [ˈeɲɟen]

‘I brought’, but [ˈeɲɟen] ![]() ‘s/he brought’. The palatal allophone [ɲ] also results as the product of synizesis.

‘s/he brought’. The palatal allophone [ɲ] also results as the product of synizesis.

The palatal allophones [c ɟ ç ʝ] of the dorsal consonants /k ɡ x ɣ/ may result due to synizesis. Synizesis is a phonological process specific to Modern Greek whereby a vocalic phoneme /i/ in a prevocalic position in certain lexical items does not surface as a syllable nucleus, but either turns into an onset consonant or deletes. For example, ![]() ‘upright’,

‘upright’, ![]() ‘traveller’. In some cases, the palatal [ʝ] can be an allophone of the non-syllabic /i̯/ that undergoes synizesis, e.g.

‘traveller’. In some cases, the palatal [ʝ] can be an allophone of the non-syllabic /i̯/ that undergoes synizesis, e.g. ![]() ‘townsperson’.

‘townsperson’.

Apart from the palatalisation of dorsals, synizesis may also cause the palatalisation of the coronal sonorants /l/ and /n/, as is the case with other Modern Greek varieties. The resulting allophones are traditionally transcribed as palatal [ʎ] and [ɲ] respectively (see e.g. Arvaniti Reference Arvaniti1999a). However, impressionistically, their exact realisation may be a post-alveolar lateral and an alveolopalatal nasal respectively (see Nicolaidis Reference Nicolaidis, Theophanopoulou-Kontou, Lascaratou, Sifianou and Georgiafentis2003; Arvaniti Reference Arvaniti2007: 113).

Notwithstanding, Pontic Greek varieties are known for their lack of synizesis in certain contexts. For instance, while, in Standard Modern Greek, synizesis takes place in words such as ![]() ‘voice’,

‘voice’, ![]() ‘children’, and

‘children’, and ![]()

![]() ‘who:m:nom’, in Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek there is no synizesis in those words:

‘who:m:nom’, in Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek there is no synizesis in those words: ![]() ‘voice’,

‘voice’, ![]() ‘children’,

‘children’, ![]() ‘who:m:nom’.

‘who:m:nom’.

Vowels

Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek has five vowels, namely [a e i o u], as is the case with most Modern Greek varieties.

However, contrary to Standard Modern Greek, where the low vowel is a central [ɐ] (Arvaniti Reference Arvaniti2007: 118), in this variety, as produced by FC, the low vowel is rather a front vowel [a]. The vowels [e] and [o] were produced by FC at intermediate height between low-mid and high-mid and thus a more narrow phonetic transcription for them would be [e̞] and [o̞] respectively. These vowels are presented in a F1-F2 plot in Figure 5. The formant values of this plot resulted from the acoustic analysis of an extended word list that FC read. This list consisted of 82 tokens, of which 69 contained instances of the five vowels represented in Figure 5.

Figure 5 Formant values and error bars in Bark scale for F1 and F2 for the five vowels of Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek. Numerical numbering (in dark) outside the axes indicates Bark values; the numbering (in grey) inside the axes indicates Hertz values. The origin is in the upper right.

Pontic Greek is traditionally described as containing three more vowels: [ӕ], [œ], and [ɯ] (Oeconomides Reference Oeconomides1908: 2). However, the speaker recorded did not produce any of those vowels and was unaware of their existence: more specifically, when the first author, a trained phonetician, produced the vowels [ӕ], [œ], and [ɯ] in certain Pontic Greek words found in the literature, FC reported that she had never heard such vowels being used in any variety of Pontic Greek. The same holds in an informal investigation we ran among other native speakers of Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek. The lack of these three vowels is arguably the result of contact with the form(s) of Greek spoken in Greece. In our informal investigation, the native speakers we consulted reported that they recognised the words containing [ӕ] or [œ] as belonging to the lexicon of their variety, albeit produced not with those vowels; however, the words containing [ɯ] that were encountered in the literature (all in Turkish loanwords) were not known to the native speakers we consulted. Following this informal perceptual investigation, we recorded FC producing 20 words of her variety that have been traditionally described as containing [ӕ] or [œ] (as explained above, no words exist in the subject’s variety containing [ɯ]). The results showed that the vowel used where an [œ] was expected was invariably produced as [o]; as shown in Figure 6, the instances of expected [œ] overlapped with the area of the realisations of the actual [o] vowel. Regarding the expected [ӕ] vowel, it was realised mainly as a low [a] vowel with a distribution overlapping with the distribution of the actual [a] vowel; in some cases, such as in the word meaning ‘stuffed vine leaves’, which was expected to be pronounced as [dolˈmaðӕ] ![]() , the expected [ӕ] vowel was realised as [e] (i.e. [dolˈmaðe]

, the expected [ӕ] vowel was realised as [e] (i.e. [dolˈmaðe] ![]() ).

).

Figure 6 Same as Figure 5, with the addition of ellipses representing the spread of realisations of the vowels ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() (solid lines). The realisations of the expected

(solid lines). The realisations of the expected ![]() vowel are represented with diamonds and are enclosed in a dashed lined ellipsis. The realisations of the expected

vowel are represented with diamonds and are enclosed in a dashed lined ellipsis. The realisations of the expected ![]() vowel are represented with squares and are enclosed in two dotted lined ellipses.

vowel are represented with squares and are enclosed in two dotted lined ellipses.

Stress

As is the case with all Modern Greek varieties, words in Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek bear lexical stress, with the exception of clitics and some functional words. Stress is manifested as increased duration, higher intensity and changes in F0. Stress is contrastive, e.g. [kaˈla] ![]() ‘well’ vs. [ˈkala]

‘well’ vs. [ˈkala] ![]() ‘better’. Most Modern Greek varieties restrict stress on one of the last three syllables of the word. Pontic Greek allows stress to fall beyond the third syllable from the end either due to inflectional endings or because of clitics that get attached on the stem, e.g. [ekaˈlat͡ʃevanemaˌsen]

‘better’. Most Modern Greek varieties restrict stress on one of the last three syllables of the word. Pontic Greek allows stress to fall beyond the third syllable from the end either due to inflectional endings or because of clitics that get attached on the stem, e.g. [ekaˈlat͡ʃevanemaˌsen] ![]() ‘they were talking to us’, [ˈestilanemaˌsen]

‘they were talking to us’, [ˈestilanemaˌsen] ![]() ‘they sent us’, [ˈiðaˌnatune]

‘they sent us’, [ˈiðaˌnatune] ![]() ‘they saw him’. In these cases there is a secondary stress on the first or third syllable from the end (see Kontosopoulos Reference Kontosopoulos2008: 15).

‘they saw him’. In these cases there is a secondary stress on the first or third syllable from the end (see Kontosopoulos Reference Kontosopoulos2008: 15).

Trapezountian belongs to the varieties of Pontic Greek in which unstressed /i/ and /u/ may delete, e.g. [tɾaˈpez] ![]() ‘table’ and [ˈakson]

‘table’ and [ˈakson] ![]() ‘listen (2sg.imp)’ in Trapezountian as opposed to [tɾaˈpezin]

‘listen (2sg.imp)’ in Trapezountian as opposed to [tɾaˈpezin] ![]() ‘table’ and [ˈakuson]

‘table’ and [ˈakuson] ![]() ‘listen (2sg.imp)’ in other Pontic Greek varieties (see Kontosopoulos Reference Kontosopoulos2008: 14).

‘listen (2sg.imp)’ in other Pontic Greek varieties (see Kontosopoulos Reference Kontosopoulos2008: 14).

Transcription of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’

In what follows, a broad phonemic and narrow phonetic transcription is provided along with an orthographic version of the ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ passage translated into Etoloakarnania Trapezountian Pontic Greek. Pontic Greek in general does not have a codified writing system. The one the authors use in this paper is to a certain extent based on Papadopoulos (Reference Papadopoulos1955); in particular the use of a diacritic over certain consonantal graphemes is followed in order to represent post-alveolar sounds. In addition, we use the rough breathing diacritic for representing aspirated consonants.

Broad phonetic transcription

Narrow phonetic transcription

Orthographic version

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100320000201.

) was originally an etic term, while Pontians called their language by other names, mainly [ɾoˈmeika]

) was originally an etic term, while Pontians called their language by other names, mainly [ɾoˈmeika]  ‘Romeika’ (Sitaridou

‘Romeika’ (Sitaridou  ‘Laz language’ (Drettas

‘Laz language’ (Drettas  is the standard term used not only by researchers, but also by native speakers of Pontic Greek born in Greece to refer to their variety (but see Sitaridou

is the standard term used not only by researchers, but also by native speakers of Pontic Greek born in Greece to refer to their variety (but see Sitaridou