ShawiFootnote 1 is the language of the indigenous Shawi/Chayahuita people in Northwestern Amazonia, Peru. It belongs to the Kawapanan language family, together with its moribund sister language, Shiwilu. It is spoken by about 21,000 speakers (see Rojas-Berscia Reference Rojas-Berscia2013) in the provinces of Alto Amazonas and Datem del Marañón in the region of Loreto and in the northern part of the region of San Martín, being one of the most vital languages in the country (see Figure 1).Footnote 2 Although Shawi groups in the Upper Amazon were contacted by Jesuit missionaries during colonial times, the maintenance of their customs and language is striking. To date, most Shawi children are monolingual and have their first contact with Spanish at school. Yet, due to globalisation and the construction of highways by the Peruvian government, many Shawi villages are progressively westernising. This may result in the imminent loss of their indigenous culture and language.

Figure 1 Map of the Kawapanan linguistic area.

As for documentation of Shawi, there was no single grammatical sketch of it until the 1980s, when the Christian missionary and SIL linguist Helen Hart initiated a project to study and describe the language. Hart, together with a large number of consultants coming from very different Shawi-speaking communities, translated the New Testament into Shawi (Hart Reference Hart1978), wrote a very complete dictionary of the language (Hart Reference Hart1988), as well as a short grammar sketch, and wrote the first phonological sketch of the language (Gordon de Powlison et al. Reference Gordon de Powlison, Hart and Hart1976). More recently, Barraza de García (Reference Barraza de García2005) wrote a Ph.D. dissertation on the verbal system of Shawi, and Luis Miguel Rojas-Berscia worked on the syntax and semantics of causative constructions (Rojas-Berscia Reference Rojas-Berscia2013) and the distribution of split ergativity in the language (Rojas-Berscia & Bourdeau Reference Rojas-Berscia and Bourdeau2018).

There were, however, a few substantial attempts to analyse the history of the language. One of these was Beuchat & Rivet (Reference Beuchat and Rivet1909), dedicated to the study of the origins of Kawapanan languages, mentioning for the first time a clear cut between this language family and Chicham/Jivaroan. The number of comparative and philological studies of the Kawapanan languages increased exponentially during the last decade. Valenzuela (Reference Valenzuela and Adelaar2011) worked extensively on the reconstruction of Proto-Kawapanan, as well as on possible areal connections with major Andean languages such as Quechua and Aymara (Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela2015). Thanks to current philological analyses of 18th-century Shiwilu (Alexander-Bakkerus Reference Alexander-Bakkerus2013, Reference Alexander-Bakkerus2016; Rojas-Berscia Reference Rojas-Berscia2017), and to current descriptions of both Shawi and Shiwilu, we will be able to better understand the underlying dynamics behind the emergence of the great linguistic diversity found in Northwestern Amazonia.

Consonants

The Shawi phoneme inventory consists of twelve consonants and four vowels. The consonants phoneme group consists of five plosives, two fricatives, two nasals, one tap, and two approximants. The following consonant chart is adapted from Rojas-Berscia (Reference Rojas-Berscia2013: 23).

Minimal pairs are offered below in phonemic transcriptions, with syllable boundaries indicated by dots and stress by [ˈ]. The list was kept as minimal as possible. Some consonants are repeated to illustrate contrastiveness as accurately as possible. The words are followed by their orthographic representations and English glosses. (Abbreviations used in this paper are listed at the end of the transcription section.)

Unlike Barraza de García (Reference Barraza de García2005: 37), we do not include the segment [ʰ] as a phoneme of the language. As already noted by Hart (Reference Hart1988) – evident from her transcriptions and previous analyses of the phonology of the language (Gordon de Powlison et al. Reference Gordon de Powlison, Hart and Hart1976) – [ʰ] is not phonemic, as will be shown in the ‘Processes’ section.

Plosives

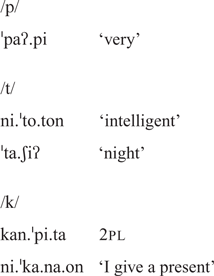

There are five plosives in Shawi. On the basis of proprioceptive and visual observations, /p/ is an unaspirated bilabial plosive, /t/ is a laminal alveolar plosive, and /k/ is a dorsal velar plosive. All of them occur in onset position. None of these plosives are allowed in coda position. Below we present some examples:

/t͡ʃ/occurs at the beginning of the word, as in the word ˈt͡ʃi.mi.naw ‘I die’. / t͡ʃ/ is a laminal postalveolar affricate. The occurrence of this consonant inside the word or root is rare, but possible. Below we present some cases:

Some borrowings which present the prototypical /ʤ͡/ of Amazonian Spanish are accommodated to /t͡ʃ/ in the language, such as the word for ‘street’, kachi [ˈka.t͡ʃi] (Spanish ‘calle’). Apart from these cases and some reduplications such as [ˈt͡ʃiɁ.t͡ʃi.wi.tɘɁ] ‘intestine’, this phoneme is very productive in front of /i/, but not with the other vowels, which suggests a diachronic palatalisation process from *ki/ti >[t͡ʃi].Footnote 3

The glottal stop in Shawi does not behave like most Shawi consonants: it only occupies the coda position:

Plosives can undergo inter-vocalic voicing. This phenomenon occurs mostly in southern varieties:

In this case, /p/ underwent voicing and was realised as its allophone [b]. Nevertheless, in most southern varieties of Shawi, [b] is realised as [w] due to lenition. This process is progressively leading to the elision of the consonant. Below we present one of the most prototypical examples:

Voicing after nasals also occurs in Shawi, as well as in Shiwilu (see Valenzuela & Gussenhoven Reference Valenzuela and Gussenhoven2013, Madalengoitia Reference Madalengoitia2013). This phenomenon, however, is absent in southern varieties such as the Paranapura variety. Barraza de García (Reference Barraza de García2005: 49) documents the occurrence of this phenomenon in Cahuapanas and Sillay Shawi.Footnote 4 For example:

Fricatives

There are two fricatives in Shawi. /s/ is a laminal alveolar fricative, while /ʃ/ is a laminal post-alveolar fricative. Like the plosives, both occur in onset position, never in coda position.

Fricatives can also undergo voicing. This phenomenon occurs mostly in southern varieties, e.g.:

Nasals

There are two nasal consonants in Shawi. /m/ is a bilabial nasal, while /n/ is a laminal alveolar nasal. Both occur in onset position. /n/ can occur in coda position.

Nasals assimilate in place to a following consonant. Below we present some examples. In some cases, however, nasals coalesce with the preceeding vowel, which becomes nasalised. This is explained in the section on vowels.

As shown in the last two words, the nasal /n/ is realised as its velar allophone [ŋ] in coda position.

Tap

In Shawi there is only a single tap – the apical alveolar /ɾ/. As most consonant phonemes in the language, it only occurs at the beginning of the syllable, e.g.:

/ɾ/ is neutralised in word-initial onsets and, word-internally, after a glottal stop. Once neutralisation takes place, /ɾ/ is realised as [n]. Consequently, the occurrence of [ɾ] as onset of the first syllable is almostFootnote 6 inexistent.Footnote 7 Examples include:

Approximants

Shawi is characterised by a frequent occurrence of approximants, just like its sister language Shiwilu (Valenzuela & Gussenhoven Reference Valenzuela and Gussenhoven2013: 100). Approximants behave very much like their other consonantal counterparts. They always occur in onset position and never in coda position. /w/ is a labial-velar approximant. /j/ is a palatal approximant. Below we present some examples:

However, they cannot occur in onset position when a vowel of a similar articulation follows: /w/ never occurs before /o/, and /j/ never occurs before /i/.

Vowels

Shawi has four vowels: the close front unrounded /i/, the close-mid central unrounded /ɘ/, the open central /a/ and the close-mid back rounded /o/. A similar analysis can be found in Gordon de Powlison et al. (Reference Gordon de Powlison, Hart and Hart1976). Vowels occur in every word context and there is no clear synchronic quantity contrast.Footnote 8 The vowel chart for Shawi, including its main vocalic features, is adapted from Rojas-Berscia (Reference Rojas-Berscia2013: 30).

Minimal pairs are offered as phonemic transcriptions with syllable boundaries indicated by dots and stress by [ˈ]. Some vowels are repeated to illustrate contrastiveness as accurately as possible.

Below we provide an acoustic analysis, carried out with the help of a male consultant of Pueblo Chayahuita. The analysis is based on 16 words from a Swadesh list. The words used were: ka ‘I’, a’na ‘one’, sami ‘fish’, and nante’ ‘foot’ for /a/; pi’i ‘sun’, ira ‘path’, iwan ‘wind’ inchinan ‘left’ for /i/; werun ‘leaf’, pen ‘fire’, teme ‘louse’, and kema ‘you’ for /ɘ/; and nu’pa ‘soil’, shu’shu ‘nipple’, nuya ‘good’, and ku ‘no’ for /o/. Table 1 displays the means of F1 and F2 for each of the vowels in the four words:

Table 1 Means of F1 and F2 after four words.

The IPA symbol used for each token is based on vowel quality and our familiarity with the sounds. The distribution of vowel sounds in the plot is presented in Figure 2 (on next page).

Figure 2 Vowel ellipses for /i ɘ o a/ in the F1/F2 plane. Each vowel contains 24 scatters (4 words × 2 repetitions × 3 equidistant measurements taken from the steady-state portion). Raw formant values were converted to bark and sigma ellipses were superimposed (number of sigmas = 2) in Praat (Boersma & Weenink Reference Boersma and Weenink2016).

There are no nasal vowels in the language. However, Shawi vowels sometimes become nasalised when followed by a nasal, while the nasal itself is deleted. This occurs only in word-final position.Footnote 9 Below we present some examples:

Table 2 Distribution of consonantal phonemes. (Y) indicates a consonant occurs in position (X) while (N) indicates that it does not. (–) indicates that, although that combination is possible, such a syllable does not appear in the corpus. #_ = word-initial;. _/ = syllable-initial, V._ = post-vocalic; C._ = post-consonantal; _. = syllable final, _# = word-final; _(x) = preceding vowel (x). /p t k t ʃ s ʃ/constitute a natural class in the language.

Syllable structure

The general syllable structure of the language is (C)V(C[+nasal, +dorsal]/[+contr gl]), with both the onset and the coda being optional. CC-onsets are normally the product of reductions, such as the vm+non.fut construction te-ra>tra-, and the 1.incl marker, pu-wa>-pwa.

A detailed overview of the distribution and restrictions of occurrence of consonantal phonemes in syllable structure is presented in Table 2.

Processes

[ʰ]epenthesis in coda position

Shawi displays an [h]-like segment in some words. Figures 3 and 4 show the spectrograms of two words, kema ‘you’ and keken ‘heavy’, respectively. The former does not display [h]. The latter shows a friction in the coda position of the first syllable.

Figure 3 Spectrographic representation of /kɘma/ ‘you’. In this case no [ʰ] is found.

Figure 4 Spectrographic representation of /kɘkɘn/ ‘heavy’. The friction found in the coda of the first syllable has been marked.

The occurrence of [ʰ] was previously described as a co-vowel by Gordon de Powlison et al. (Reference Gordon de Powlison, Hart and Hart1976: 2), and as an independent phoneme of the language by Barraza de García (Reference Barraza de García2005). Both accounts agree upon the fact that [h] only occurs in coda position. Yet, the occurrence of can be explained in terms of a simple lexical rule of epenthesis (Gussenhoven & Jacobs Reference Gussenhoven and Jacobs2011: 164). Epenthesis is expressed as insertion of [ʰ] in coda position. This is a rule specified in the lexicon. Thus, the rule only applies before any derivational or inflectional processes have taken place. [ʰ] is then inserted as a coda to an open syllable if the onset of the following syllable is an obstruent (plosives and fricatives). All these conditions must be met in order for [ʰ] to occur. The fact that [h] only occurs before an obstruent resembles the phonetic environment required in Huariapano (Parker Reference Parker1994: 108–109) for the [ʰ] epenthesis.

Below we present some examples, including the underlying form as specified in the lexicon, followed by the form which already underwent [ʰ] epenthesis. Some derivational or inflectional processes were specified as occurring postlexically:

All examples meet all conditions. Nitepaw [ni+ˈtɘʰ.pa+w] is of special interest. Had the rule not applied at the lexical level, the outcome would have been *[niʰ.ˈtɘʰ.paw]. The rule, nevertheless, applied before the prefixation of ni- ‘reciprocal’.

There are some suffixes, such as the progressive -sa, the genitive -ken and the additive -pu, which also trigger the occurrence of [ʰ] outside the main lexical rule.Footnote 10 The suffixes -pu and -ken trigger the occurrence of [ʰ] in the preceding syllable. By contrast, -sa triggers the occurrence of [ʰ] in the following syllable. Although the rule applies postlexically, the syllable in question must be open. This area of morphophonemics, however, still awaits further exploration. Below we present some examples (bold indicates the place of these suffixes in the examples):

Syncope

Syncope is frequent in Shawi speech. There are two suffixes that are commonly syncopied: -we 1.sg and -te vm. Examples include the following:

Transcription of the recorded passage

The story of the North Wind and the Sun was translated from its original English version in one session with the help of speaker A. The transcription is phonemic. Parentheses indicate intonational phrases.

Phonemic transcription

This is a broad transcription, which exclusively employs segmental symbols that were assigned to vocalic and consonantal phonemes.

(ˈi.wan) (ˈpiʔ.i.ˈpi.pi.ɾin.ˈkɘ.ɾan) (i.ˈnawa) (ˈpiʔ.i) (ˈja.wa.pi.ɾi.na.wɘ) (ˈin.ta) (ˈt͡ʃi.ni t͡ʃi.ˈni.kɘn.ˈtaʔ.to.na) || (i.ˈna.ɾan) (ˈwɘʔ.nin) (ˈaʔ.na ˈi.ɾa.ka.ˈma.jo) (ˈjaʔ.sɘʔ.ko.tɘ.ɾin) (ˈaʔ.na) (wɘ.ˈto.ja ˈko.ton) || (i.na.ˈpi.ta) (ˈkan.pi) (ˈaʔ.na) (jon.ˈki.nan.kɘ) (ˈin.ta) (ˈi.na) (ˈi.ɾa.ka.ˈma.jo) (ˈko.ton) (ˈmaʔ.tɘ.ɾin.so) (ˈi.na) (ˈni.sa.ɾin) (ˈt͡ʃi.ni t͡ʃi.ˈni.kɘn.ˈto.pi) || (i.ˈna.ran) (ˈpiʔ.i.ˈpi.pi.ɾin.ˈkɘ.ɾan) (ˈi.wan) (ˈt͡ʃi.ni ˈt͡ʃi.ni.kɘn) (ˈpi.wi.pi.ɾin.wɘ) (ˈi.ɾa.ka.ˈma.jo.so) (a.ˈkɘ.tɘ) (ˈja.sɘ.ko.tɘ.ɾin) (ˈko.to.nɘn.kɘ) || (i.ˈna.ɾan) (to.ˈpi.nan) (ˈi.wan) (ˈpiʔ.i.ˈpi.pi.ɾin.kɘ.ɾan) (ka.ˈno.tɘ.ɾin) || (i.ˈna.ɾan) (ˈpiʔ.i) (ˈaʔ.pi.nin) (ˈwɘ.no.kaʔ) | (i.ˈna.ɾan) (ˈna.po.a.wa.ton) (ˈi.ɾa.ka.ˈma.jo) (ˈko.ton) (ˈi.nan.pi.ɾa.ɾin) || (i.ˈna.po.t͡ʃin) (ˈi.wan) (ˈpiʔ.i.ˈpi.pi.ɾin.ˈkɘ.ɾan) (ˈna.ni.tɘ.ɾin ˈno.wi.tɘ.ka.ˈma.ɾɘ) (ˈpiʔ.i) (ˈt͡ʃi.ni t͡ʃi.ˈni.kɘn ˈni.ton) (ˈka.to.ˈɾo.sa.ˈkɘ.ɾan) ||

Orthographic version

This is an orthographic version, in the current official Shawi alphabet, as requested by our consultants.

Iwan pi’ipihpirinkeran inawa Pi’i yawapirinawe inta chini chinihken ta’tuna. Inaran we’nin a’na irakamayu yase’kuterin a’na wehtuya kuhtun. Inapita kampi a’na yunkinanke inta ina irahkamayu kuhtun ma’terinsu ina nihsarin chini chinihken tuhpi. Inaran pi’ipihpirinkeran Iwan chini chinihken piwipirinwe irahkamayu ahkete yasekuterin kuhtunenke. Inaran tuhpinan Iwan pi’ipihpirinkeran kanuhterin. Inaran Pi’i a’pini wenuka’, inaran nahpuawatun irakamayu kuhtun inanpirarin. Inahpuchin Iwan pi’ipihpirinkeran naniterin nuwitekamare Pi’i chini chinihken nihtun kahturusakeran.

Glossed and translated version

Abbreviations

The abbreviations used in this Illustration rely primarily on the Leipzig Glossing Rules.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Amalia Arvaniti and two anonymous referees for the insightful comments on a previous version of this Illustration. We also thank André Radtke for his help with the optimisation of the audio files. The first author acknowledges the financial and academic support from the Language in Interaction Research Consortium in the Netherlands. The authors greatly acknowledge the useful comments and criticisms on previous drafts of the present Illustration by Carlos Gussenhoven, Pieter Muysken, Steve Levinson, Pieter Seuren, Hamed Rahmani, Gunter Senft, Simeon Floyd, and Roberto Zariquiey. The first author is grateful to Pilar Valenzuela for the initial encouragement to study Kawapanan languages, as well as for her insighful comments during the Amazonicas VI conference in Leticia, Colombia, and Tabatinga, Brazil, in May 2016.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100318000415.