Mapudungun (/m

![]() pʊðʊˈŋʊn/ or /m

pʊðʊˈŋʊn/ or /m

![]() pʊθʊˈŋʊn/; also known as ‘Mapudungu’, ‘Mapuzugun’, ‘Mapuche’, ‘Mapuchedungun’, ‘Chedungun’ and ‘Araucanian’ or ‘Araucano’ (the latter two being archaic)) is a language isolate spoken actively by approximately 144,000 people in Chile (Zúñiga Reference Zúñiga2007), as well as by some 8,400 people in Argentina (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos 2005), virtually all of whom are bilingual in Spanish. Its ISO 639–3 code is arn.

pʊθʊˈŋʊn/; also known as ‘Mapudungu’, ‘Mapuzugun’, ‘Mapuche’, ‘Mapuchedungun’, ‘Chedungun’ and ‘Araucanian’ or ‘Araucano’ (the latter two being archaic)) is a language isolate spoken actively by approximately 144,000 people in Chile (Zúñiga Reference Zúñiga2007), as well as by some 8,400 people in Argentina (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos 2005), virtually all of whom are bilingual in Spanish. Its ISO 639–3 code is arn.

Mapudungun can be divided into three broad dialect groups: north, central and south. These are further divided into eight sub-groups: I and II (northern group), III–VII (central group) and VIII (southern group). These dialects share a high degree of mutual intelligibility, which decreases only between I and VIII (Croese Reference Croese1980). The Mapudungun spoken in the Argentinean provinces of Neuquén and Río Negro is similar to that of the central dialect group in Chile, while the Ranquel (Rankülche) variety spoken in the Argentinean province of La Pampa is closer to the northern dialect group (Golluscio Reference Golluscio, Haspelmath and Tadmor2009).

Mapudungun is not an official language of Chile or Argentina, and has received virtually no government support throughout its history. It is not used as a language of instruction in either country's educational system (Salas Reference Salas1992), and no university trains teachers of the language. At present, a small number of schools may impart Mapudungun in optional second-language classes (spoken greetings and phrases only; neither true oral language competency nor literacy are taught) to Mapuche students as part of the Chilean government's Bilingual Intercultural Education Program (Fernández Droguett Reference Fernández Droguett2005). However, the use of this educational strategy by the program, along with its lack of a language revitalization policy, make its efficacy in furthering the use of Mapudungun highly doubtful.

A multitude of writing systems have been developed for Mapudungun, but none has gained widespread adoption, and the language is rarely written.

Only 2.4% of urban speakers and 15.9% of rural speakers use Mapudungun when speaking with children (Zúñiga Reference Zúñiga2007), while only 3.8% of speakers aged 10–19 years in the south of Chile (the language's stronghold) are ‘highly competent’ in the language (Gundermann et al. Reference Gundermann, Canihuan, Clavería and Faúndez2009). These factors, combined with the language's small number of speakers and the strong pressures that they face to abandon the language in favor of Spanish, indicate that Mapudungun's survival cannot be guaranteed unless the current situation changes substantially.

The present description is based on the speech of four female and five male speakers whose ages range from 40 to 62 years (average: 51 years). All are native first-language speakers of Mapudungun who learned Spanish as a second language, starting on average at age 9, and all but two of them remain dominant in Mapudungun. They were born and raised in Isla Huapi, an isolated agricultural settlement of approximately 600 inhabitants located in Chile's 9th Region (Araucanía), and all but one continue to live there.Footnote 1 Their dialect belongs to sub-group V. The recordings of the word lists and the ‘North Wind’ text are of a 56-year-old male speaker, with the exception of seven words containing phenomena not found in his idiolect.Footnote 2 Additional recordings of each speaker's stressed and unstressed allophones of /ɘ/ have also been provided as supplementary sound files.

The orthographic transcriptions in the present article follow Zúñiga's (2001) proposal, with the addition of <sh> for /ʃ/. It should be noted that the selection of an alphabet to represent Mapudungun is a politically- and emotionally-charged issue that is far from being settled; our choice in this matter reflects what we believe to be the most transparent option for the readers of this Illustration.

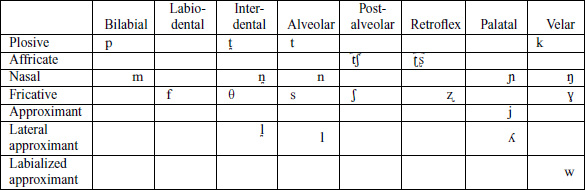

Consonants

An asterisk is used in the preceding list to indicate words which were pronounced with stress on the other syllable by some speakers (see ‘Suprasegmental features’, below).

In the variety of Mapudungun that this illustration describes, four pairs of consonants are distinguished by an interdental/alveolar opposition: /

![]() /–/t/, /

/–/t/, /

![]() /–/l/, /θ/–/s/ and /

/–/l/, /θ/–/s/ and /

![]() /–/n/. With the exception of the voiceless phonemes /θ/ and /s/, these pairs have merged in favor of the alveolars in dialect sub-group I (Salamanca & Quintrileo Reference Salamanca and Quintrileo2009). In sub-group II, there are conflicting reports: Sánchez (Reference Sánchez1989) claims that the same merger has occurred, while Salamanca (Reference Salamanca1997) finds that the distinction is maintained. In other dialects, there is also dispute on this issue, with several authors claiming the distinction is either dying out (Smeets 2007) or has already done so (Moesbach Reference Moesbach1962, Croese Reference Croese1980). In dialects in which the merger has taken place, the interdentals may be present as allophones of the corresponding alveolars (Croese Reference Croese1980, Salamanca & Quintrileo Reference Salamanca and Quintrileo2009).

/–/n/. With the exception of the voiceless phonemes /θ/ and /s/, these pairs have merged in favor of the alveolars in dialect sub-group I (Salamanca & Quintrileo Reference Salamanca and Quintrileo2009). In sub-group II, there are conflicting reports: Sánchez (Reference Sánchez1989) claims that the same merger has occurred, while Salamanca (Reference Salamanca1997) finds that the distinction is maintained. In other dialects, there is also dispute on this issue, with several authors claiming the distinction is either dying out (Smeets 2007) or has already done so (Moesbach Reference Moesbach1962, Croese Reference Croese1980). In dialects in which the merger has taken place, the interdentals may be present as allophones of the corresponding alveolars (Croese Reference Croese1980, Salamanca & Quintrileo Reference Salamanca and Quintrileo2009).

Given the typological rarity of this series of contrasts (Moran Reference Moran2011) and the controversy that surrounds them, we present a series of palatograms (Figures 1–8) to both confirm their existence and illustrate their precise articulatory nature.Footnote 3

Figure 1 Plosive /

![]() /. Palatogram of /fɘˈ

/. Palatogram of /fɘˈ

![]()

![]() / ‘husband’. Note the stain on the biting and outer surfaces of the upper teeth, indicating interdental contact.

/ ‘husband’. Note the stain on the biting and outer surfaces of the upper teeth, indicating interdental contact.

Figure 2 Plosive /t/. Palatogram of /fɘˈt

![]() / ‘elderly

person’.

/ ‘elderly

person’.

Figure 3 Nasal /

![]() /. Palatogram of /mɘˈ

/. Palatogram of /mɘˈ

![]()

![]() / ‘male cousin on father's side’. Note the stain on the biting and outer surfaces of the upper teeth, indicating interdental contact.

/ ‘male cousin on father's side’. Note the stain on the biting and outer surfaces of the upper teeth, indicating interdental contact.

Figure 4 Nasal /n/. Palatogram of /mɘˈn

![]() / ‘enough’.

/ ‘enough’.

Figure 5 Fricative /θ/. Palatogram of /θɪf/ ‘rope’. Note the stain on the biting and outer surfaces of the upper teeth, indicating interdental contact.

Figure 6 Fricative /s/. Palatogram of /ˈsɪpʊ/ ‘jewelry used by women’.

Figure 7 Lateral approximant /

![]() /. Palatogram of /

/. Palatogram of /

![]()

![]() / ‘cadaver’. Note the stain on the biting and outer surfaces of the upper teeth, indicating interdental contact.

/ ‘cadaver’. Note the stain on the biting and outer surfaces of the upper teeth, indicating interdental contact.

Figure 8 Lateral approximant /l/. Palatogram of /l

![]() f/ ‘spread out on horizontal surface’.

f/ ‘spread out on horizontal surface’.

Varieties of Mapudungun that maintain the interdental–alveolar distinction are notable for having a series of five phonologically-opposed nasals: /m/, /

![]() /, /n/, /ɲ/ and /ŋ/.

/, /n/, /ɲ/ and /ŋ/.

Before the front vowels /ɪ/ and /

![]() /, the velars /k/, /ŋ/ and /ɣ/ tend to be fronted to [c], [

/, the velars /k/, /ŋ/ and /ɣ/ tend to be fronted to [c], [

![]() ], and [

], and [

![]() ] or [ʝ], respectively (e.g. /

] or [ʝ], respectively (e.g. /

![]() / ‘five’ > [

/ ‘five’ > [

![]() ]). The voiceless plosive /k/ is often aspirated, giving [kʰ] (/

]). The voiceless plosive /k/ is often aspirated, giving [kʰ] (/

![]() / ‘to wring out’ > [

/ ‘to wring out’ > [

![]() ]). Aspiration also occurs fairly frequently with [c] (see [

]). Aspiration also occurs fairly frequently with [c] (see [

![]() ], above), /t/ (/ˈfɘt

], above), /t/ (/ˈfɘt

![]() / ‘elderly person’ > [ˈfɘtʰɜ]), and occasionally with /p/ and /

/ ‘elderly person’ > [ˈfɘtʰɜ]), and occasionally with /p/ and /

![]() /. In all cases, the aspiration is more lenis than that which is produced in English, for example.

/. In all cases, the aspiration is more lenis than that which is produced in English, for example.

The voiced retroflex continuant /ʐ / can be realized as either a fricative [ʐ ] or an approximant [ɻ] in all positions; we have opted to classify it as the former (against the traditional interpretation) as this is the predominant variant in our sample. Palatographic evidence (not shown) indicates that /ʐ / is apical rather than sub-apical. In post-nuclear position, /ʐ / may be devoiced to [ʂ] (/

![]() ʊˈkʊʐ/ ‘fog’ > [

ʊˈkʊʐ/ ‘fog’ > [

![]()

![]() ˈkʊʂ]). In three of the nine speakers in our sample, /ʐ / is most frequently a retroflex lateral [ɭ] (/ˈm

ˈkʊʂ]). In three of the nine speakers in our sample, /ʐ / is most frequently a retroflex lateral [ɭ] (/ˈm

![]() ʐ

ʐ

![]() / ‘hare’ > [ˈm

/ ‘hare’ > [ˈm

![]() ɭɜ]).

ɭɜ]).

In some speakers, the retroflex affricate /

![]() / has allophones that may be described as an apical post-alveolar affricate [

/ has allophones that may be described as an apical post-alveolar affricate [

![]() ] and an aspirated apical post-alveolar plosive [

] and an aspirated apical post-alveolar plosive [

![]() ].Footnote

4

].Footnote

4

Contrary to reports in the literature, the phonemes /n/ and /l/ do not have retroflex allophones ([ɳ] and [ɭ]) when in the presence of the retroflex phonemes /ʐ / and /

![]() /, but remain alveolar (/wɪˈ

/, but remain alveolar (/wɪˈ

![]()

![]() n/ ‘visitor’ > [w

n/ ‘visitor’ > [w

![]() ˈ

ˈ

![]()

![]() n]; /kɘˈ

n]; /kɘˈ

![]()

![]() l/ ‘fire’ > [k

l/ ‘fire’ > [k

![]() ˈ

ˈ

![]()

![]() l]).

l]).

The approximant /j/ may be realized as the fricative [ʝ] (/k

![]() jʊ/ ‘six’ > [kɜˈʝʊ]).

jʊ/ ‘six’ > [kɜˈʝʊ]).

In utterance-final position, /

![]() / and /l/ may be devoiced to [

/ and /l/ may be devoiced to [

![]() ] and [ɬ], respectively (/k

] and [ɬ], respectively (/k

![]() ˈɣɘ

ˈɣɘ

![]() / ‘phlegm that is spit’ > [kɜˈɣɘ

/ ‘phlegm that is spit’ > [kɜˈɣɘ

![]() ]; /k

]; /k

![]() ˈɘl/ ‘a different song’ > [kɜˈɘɬ]).

ˈɘl/ ‘a different song’ > [kɜˈɘɬ]).

In emphatic speech, the nasals /m/, /n/ and /

![]() /, as well as the laterals /l/ and /

/, as well as the laterals /l/ and /

![]() /, may be lengthened to up to triple the duration of non-lengthened tokens (e.g. /ˈmɘn

/, may be lengthened to up to triple the duration of non-lengthened tokens (e.g. /ˈmɘn

![]() / ‘enough’ > [ˈmɘnː

/ ‘enough’ > [ˈmɘnː

![]() ]) when in pre-nuclear position in a word-final syllable, giving the impression of a geminate. However, this phenomenon gives rise to no phonological oppositions.

]) when in pre-nuclear position in a word-final syllable, giving the impression of a geminate. However, this phenomenon gives rise to no phonological oppositions.

Dialectal differences

In dialect sub-groups III and IV the fricative phonemes /f/ and /θ/, which are predominantly voiceless in sub-groups V–VIII, have voiced allophones ([v β] and [ð], respectively) in free variation with the voiceless allophones [f ɸ] and [θ] (Echeverría & Contreras 1965; Salas Reference Salas1976; Lagos Reference Lagos1981, 1984; Álvarez-Santullano Reference Álvarez-Santullano1986). In sub-groups I and II, the voiced allophones predominate to the extent that the labiodental and interdental fricative phonemes are /v/ and /ð/ instead of /f/ and /θ/ (Salamanca Reference Salamanca1997, Salamanca & Quintrileo Reference Salamanca and Quintrileo2009). This phenomenon has also been observed in the Ranquel variety (Golluscio Reference Golluscio, Haspelmath and Tadmor2009).

The phoneme /ʃ/ occurs with certainty in sub-group V, and was suggested for IV by Suárez (Reference Suárez1959) using data from Lenz (Reference Lenz1895). In the Alto Bío-Bío region of II, neither /ʃ/ nor [ʃ] exists (Sánchez Reference Sánchez1989, Salamanca Reference Salamanca1997); cognate words in this dialect have /s/ instead. In the Tirúa region of I (Salamanca & Quintrileo Reference Salamanca and Quintrileo2009) and in sub-group IV (Echeverría Reference Echeverría1964), [ʃ] exists as an allophone of /

![]() /. In III, [ʃ] is an allophone of /s/ (Salas Reference Salas1976). It should be noted that in some cases, the differences in the status of /ʃ/ and [ʃ] may be due to authors’ differing interpretations of what constitutes a phoneme, rather than to actual dialectal differences.

/. In III, [ʃ] is an allophone of /s/ (Salas Reference Salas1976). It should be noted that in some cases, the differences in the status of /ʃ/ and [ʃ] may be due to authors’ differing interpretations of what constitutes a phoneme, rather than to actual dialectal differences.

Vowels

Mapudungun has six vowel phonemes, /ɪ ë

![]() ö ʊ ɘ/, all of which have more close allophones in unstressed position, [

ö ʊ ɘ/, all of which have more close allophones in unstressed position, [

![]() ], as per the instrumental analysis described below. It should be noted that the vowels of Mapudungun have traditionally been treated as the five vowels of Spanish (/i e a o

u/), with identical stressed and unstressed allophones, plus a high central unrounded vowel /ɨ/ (commonly known as the ‘sixth vowel’) having a mid central allophone [ə] in unstressed position (Echeverría & Contreras 1965).

], as per the instrumental analysis described below. It should be noted that the vowels of Mapudungun have traditionally been treated as the five vowels of Spanish (/i e a o

u/), with identical stressed and unstressed allophones, plus a high central unrounded vowel /ɨ/ (commonly known as the ‘sixth vowel’) having a mid central allophone [ə] in unstressed position (Echeverría & Contreras 1965).

For the present description, an instrumental analysis was performed on 871 vowel tokens produced by nine speakers (four female, five male). The results of the analysis are shown as a standard vowel trapezoid in Figure 9, and as an F1 versus F2 plot in Figure 10. Values were normalized using the Nearey 1 formula (Nearey Reference Nearey1977) and scaled to Hz. The selection of vowel symbols was based on Lindblom's (1986) quasi-cardinal vowels as modified by Iivonen (Reference Iivonen1994).

Figure 9 Vowel chart of Mapudungun.

Figure 10 Plot of F1 versus F2 for average values of 871 stressed (black circles) and unstressed (white circles) vowel tokens produced by 4 female and 5 male speakers. Values were normalized using the Nearey 1 formula and scaled to Hz.

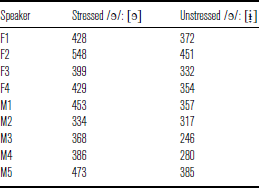

As the instrumental analysis reverses the traditional interpretation of the stressed ([ɘ] instead of [ɨ]) and unstressed ([

![]() ] instead of [ə]) allophones of Mapudungun's sixth vowel, we provide their unnormalized mean F1 values for each speaker in Table 1.

] instead of [ə]) allophones of Mapudungun's sixth vowel, we provide their unnormalized mean F1 values for each speaker in Table 1.

Table 1 Unnormalized mean F1 values (in Hz) of stressed and unstressed tokens of /ɘ/.

Fully 10 of Mapudungun's 12 vowel allophones are concentrated in the high vowel space, while the remaining two fall in the mid-low area (Figure 10). Furthermore, the entire vowel space used by the language is a mid-centralized subset of the available space. Even when taking into account 1 standard deviation of dispersion, the Hz-scaled normalized average F1 values of Mapudungun vowels are limited to a range of approximately 325–575 Hz, while F2 falls between 1000 Hz and 2050 Hz. Yet in spite of this compact spacing, there is little overlap between vowels, especially stressed ones. This vowel distribution pattern does not seem to accord with the typologically prevalent one of maximum dispersion (Disner 1984).

Conventions

Unstressed vowels are generally devoiced, and often elided, in utterance-final position when following voiceless consonants (/ˈɲ

![]()

![]() ɪ/ ‘spiced, coagulated blood’ > [ˈɲ

ɪ/ ‘spiced, coagulated blood’ > [ˈɲ

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ] or [ɲ

] or [ɲ

![]()

![]() ]). Some-what less frequently, utterance-final vowels may also undergo devoicing or elision after voiced consonants (/ˈköʐɘ/ ‘soup’ > [ˈköʐ

]). Some-what less frequently, utterance-final vowels may also undergo devoicing or elision after voiced consonants (/ˈköʐɘ/ ‘soup’ > [ˈköʐ

![]() ] or [köʐ ]).

] or [köʐ ]).

In word-medial position, /ɘ/ may be elided when it occurs in the syllable following the stressed one (/ˈk

![]() ɲpɘlë/ ‘a different place’ > [ˈk

ɲpɘlë/ ‘a different place’ > [ˈk

![]() ɲpl

ɲpl

![]() ]), and it may be devoiced in the syllable preceding the stressed one when following a voiceless consonant (/kɘˈ

]), and it may be devoiced in the syllable preceding the stressed one when following a voiceless consonant (/kɘˈ

![]() ɘŋ/ ‘tied, bundled’ > [k

ɘŋ/ ‘tied, bundled’ > [k

![]() ˈ

ˈ

![]() ɘŋ]).

ɘŋ]).

Suprasegmental features

Stress in Mapudungun is non-contrastive. In general, closed syllables tend to attract stress. Words ending in a consonant are stressed on the final syllable ([mɜˈkʊɲ] ‘cape, poncho’). Disyllabic words ending in a vowel tend to be stressed on the final syllable in northern and north-central dialects ([p

![]() ˈɲɪ] ‘potato’), and on the penultimate syllable in southern and south-central dialects ([ˈpöɲ

ˈɲɪ] ‘potato’), and on the penultimate syllable in southern and south-central dialects ([ˈpöɲ

![]() ] ‘potato’). If the first syllable is closed and the second open, stress falls on the first ([ˈwën

] ‘potato’). If the first syllable is closed and the second open, stress falls on the first ([ˈwën

![]()

![]() ] ‘man’). If both syllables are closed, stress tends to fall on the final one ([

] ‘man’). If both syllables are closed, stress tends to fall on the final one ([

![]() ɲˈ

ɲˈ

![]() ɪɲ] ‘we (plural)’) (Zúñiga Reference Zúñiga2006). There may also be some degree of idiolectal variation in the assignment of stress.

ɪɲ] ‘we (plural)’) (Zúñiga Reference Zúñiga2006). There may also be some degree of idiolectal variation in the assignment of stress.

In trisyllabic words, stress tends to fall on the penult if the word ends with an open syllable ([mɜˈwɪθɜ] ‘hill, mountain’), and on the final syllable otherwise ([mɜ

![]()

![]() ˈtʊn] ‘Mapuche healing ceremony’).

ˈtʊn] ‘Mapuche healing ceremony’).

In words of four or more syllables, primary stress is assigned in accordance with the rules detailed above for disyllabic words, as applied to the last two syllables of the polysyllabic word. Additionally, words of four or more syllables receive a secondary stress accent on the first or second syllable from the left. If one of the first two syllables is closed, it receives the secondary stress ([ˌ

![]() nt

nt

![]() mɜˈl

mɜˈl

![]() l] ‘sunny terrain’; [ɜˌθɘmˈ

l] ‘sunny terrain’; [ɜˌθɘmˈ

![]() ëf

ëf

![]() ] ‘person who teaches’). If both syllables are open, secondary stress falls on the first syllable ([ˌ

] ‘person who teaches’). If both syllables are open, secondary stress falls on the first syllable ([ˌ

![]()

![]() ʐ

ʐ

![]() ˈlöŋk

ˈlöŋk

![]() ] ‘headband’), while if both are closed, it falls on the second syllable ([

] ‘headband’), while if both are closed, it falls on the second syllable ([

![]() ɜlˌk

ɜlˌk

![]() nˈwën

nˈwën

![]() ] ‘thunderous skies’).

] ‘thunderous skies’).

The maximum syllable structure in Mapudungun is CVC. In pre-nuclear position, all consonants may occur; in post-nuclear position, all but plosives and affricates may occur. Mapudungun is a non-tonal language.

Transcription

Broad

Narrow

Orthographic

Piku kürüf engu antü

Piku kürüf engu antü n'otukawmekelu tuchi ñi doy newenngen, ruparumi kiñe wentru makuñtulelu. Fey mew feypiwingu: tuchi nentuñmafile ñi makuñ feytichi wentru fey doy newenngerkey pinngey. Fey mew fütra newentu tripay ti piku kürüf; welu tiyechi wentru fey doy ümpülhuwi ñi makuñ mew. Femlu ti wentru fey ti piku kürüf rupay. Fey mew ti antü wülüfüy ñi alof tripan. Arelu ti wentru, nentuy ñi makuñ. Fey mew ti piku kürüf kimi antü ñi doy newenngen.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the people of Isla Huapi for their generous cooperation, as well as Viviana Vergara Fernández for her valuable assistance in performing the fieldwork related to this illustration. The authors would also like to thank Fernando Zúñiga and Lucía Golluscio for the insightful comments they provided during the JIPA review process.