Dari, or Afghan Persian (Indo-European, Iranian, Southwestern; ISO 639-3: prs; Lewis, Simons & Fennig Reference Lewis, Simons and Fennig2013), is one of the national languages of Afghanistan, and a language of wider communication in much of the country. It is one of the three major Persian varieties, the others being Farsi (or Iranian Persian) and Tajiki (or Tajik Persian). Afghans refer to Dari either as [dɐˈɾi] or [fʌɾˈsi].

An important phonological analysis of Dari is Henderson (Reference Henderson1972). Kieffer's (Reference Kieffer1985) discussion provides a number of insights into dialectal variation around Afghanistan, and the relationship between Afghan Persian and other dialects. A wealth of data is to be found in Glassman (Reference Glassman2000), though the focus of the text is pedagogical rather than linguistic. The phonology of Iranian Persian has previously been illustrated in Majidi & Ternes (Reference Majidi and Ternes1999). More detailed phonological studies of the Iranian and Tajik varieties of Persian are Windfuhr (Reference Windfuhr, Kaye and Daniels1997) and Windfuhr & Perry (Reference Windfuhr, Perry and Windfuhr2009).

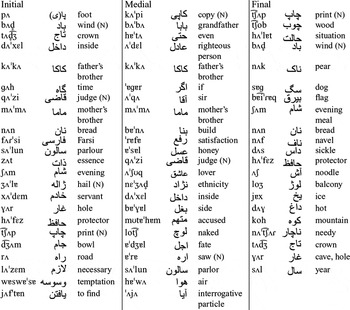

This Illustration is of the Dari spoken in Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan. Speakers of Dari exhibit a range of speech styles, depending on the formality of the situation. To capture some of this variation, recordings from two speakers are presented. The isolated words and the text so marked represent the formal speech style. The speaker for these recordings is from Kabul, though he has spent much of his adult life in Faizabad, Badakhshan province, and some time in Iran. In spite of these influences, he retains an identifiably Kabuli accent. The text is also presented in informal style. The speaker for the informal version is a lifelong resident of Kabul, educated, and about forty years of age. While not a trained linguist, he has considerable grammatical knowledge and metalinguistic awareness, arising from his position as a teacher of Dari to foreigners.

As the written form of the language is the basis for the formal style, formal pronunciations tend toward fidelity to the orthographic form. For example, the formal text contains [ˈme-kɐɾd-ɐnd] ‘they were doing’ where the informal text has [ˈme-kɐd-ɐn]. The [ɾ] and [d] present in the formal pronunciation reflect the written form,

![]() . Accordingly, formal Afghan and Iranian Persian are quite similar to one another, though not identical. The phonological analysis cannot merely recapitulate the orthography, however: several of the vowels are not represented orthographically, and orthographic forms often reflect the Arabic rather than the Persian pronunciations of words.

. Accordingly, formal Afghan and Iranian Persian are quite similar to one another, though not identical. The phonological analysis cannot merely recapitulate the orthography, however: several of the vowels are not represented orthographically, and orthographic forms often reflect the Arabic rather than the Persian pronunciations of words.

Consonants

There is not a great deal of categorical allophonic variation in Dari, though a number of consonant deletions and vowel coalescences occur at morpheme boundaries, as illustrated in the transcribed text below. The stops of Dari are unaspirated or lightly aspirated in all positions, except in careful speech. Voiced stops and affricates are optionally devoiced; in the recordings of isolated words, compare the devoiced allophones in [bʌ

![]() ] ‘wind (n)’, [xu

] ‘wind (n)’, [xu

![]() ] ‘good’, [tʌ

] ‘good’, [tʌ

![]() ] ‘crown’, [neˈʒʌ

] ‘crown’, [neˈʒʌ

![]() ] ‘ethnicity’ with the voiced voiced allophones in [bʊɾd] ‘he carried’, [sud] ‘interest’, [

] ‘ethnicity’ with the voiced voiced allophones in [bʊɾd] ‘he carried’, [sud] ‘interest’, [

![]() ob] ‘wood’, and [sɐg] ‘dog’. The phoneme /ɾ/ may be trilled to [r] in emphatic speech, as occurs in the words [ˈɐɡɐr] ‘if’, [ˈrɐfɐ] ‘satisfaction’, [ɣʌr] ‘cave, hole’, [rʌ] ‘road’ in the word list above; compare the flap [ɾ] which occurs in the transcribed text. The phoneme /h/ is frequently lost in everyday speech, though less often in formal contexts. Variation in the (formally produced) word list is illustrated above, with the word-final [h] preserved in [gʌh] ‘time’ and [koh] ‘mountain’, but dropped in [rʌ] ‘road’.

ob] ‘wood’, and [sɐg] ‘dog’. The phoneme /ɾ/ may be trilled to [r] in emphatic speech, as occurs in the words [ˈɐɡɐr] ‘if’, [ˈrɐfɐ] ‘satisfaction’, [ɣʌr] ‘cave, hole’, [rʌ] ‘road’ in the word list above; compare the flap [ɾ] which occurs in the transcribed text. The phoneme /h/ is frequently lost in everyday speech, though less often in formal contexts. Variation in the (formally produced) word list is illustrated above, with the word-final [h] preserved in [gʌh] ‘time’ and [koh] ‘mountain’, but dropped in [rʌ] ‘road’.

In relation to Iranian Persian, it can be noted that Dari has distinct /q/ and /ɣ/, which are merged in Iranian Persian but similarly distinct in Tajik Persian (Kieffer Reference Kieffer1985; Windfuhr & Perry Reference Windfuhr, Perry and Windfuhr2009: 427). Dari always has the labiovelar approximant [w] instead of the Iranian or Tajik Persian [v]; [v] is never heard, even in formal speech.

Vowels

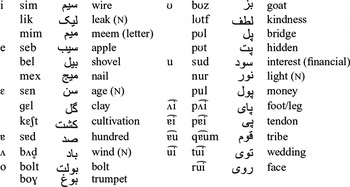

Dari has a larger inventory of vowels than Iranian Persian (see the six-vowel system indicated by Majidi & Ternes Reference Majidi and Ternes1999, and also more ‘traditional’ grammars like Thackston Reference Thackston1993 and Mace Reference Mace2003). The additional contrasts – reported previously by Henderson (Reference Henderson1972) and Glassman (Reference Glassman2000) – are between the front round vowels [e] and [ɛ], and the back round vowels [o] and [ʊ]. These contrasts are similar to vowel contrasts present in Middle and Early Modern Persian (Windfuhr Reference Windfuhr, Kaye and Daniels1997) though a more precise statement of the relation awaits further etymological study.

The distinction between the back rounded vowels is illustrated by the words [xu

![]() ] ‘good’, [xʊd] ‘self’, and [

] ‘good’, [xʊd] ‘self’, and [

![]() ob] ‘wood’. The phonemes /e/ and /ɛ/ are distinguished by the similar pair [bel] ‘shovel’ and [gɛl] ‘mud’.Footnote

1

Several examples of each of these vowels are given above. As discussed below, the difference between [e] and [ɛ], and [o] and [ʊ], is reinforced with a length contrast.

ob] ‘wood’. The phonemes /e/ and /ɛ/ are distinguished by the similar pair [bel] ‘shovel’ and [gɛl] ‘mud’.Footnote

1

Several examples of each of these vowels are given above. As discussed below, the difference between [e] and [ɛ], and [o] and [ʊ], is reinforced with a length contrast.

The vowels [

![]() ], [

], [

![]() ], [

], [

![]() ], and [

], and [

![]() ] are analyzed here as diphthongs, but could alternately be analyzed as a monophthong–glide sequence. There is evidence in favor of both analyses. Although the maximal syllable template of Dari is CVCC, diphthongs do not occur in syllables with two coda consonants. This could be taken as an indication that one consonant position is being taken up by a glide. On the other hand, syllables with two consonants are not so frequent as to rule out the possibility of an accidental gap in the lexicon. Conversely, glides do not occur freely in coda position: a monophthongal analysis would then have to stipulate a list of permissible vowel–consonant sequences (i.e. [ʌj], [ɐj], [ɐw], [uj]), which in a sense merely recapitulates the diphthongal analysis. Therefore, though the phonological facts do not force one analysis over another, the diphthongal analysis is adopted here.

] are analyzed here as diphthongs, but could alternately be analyzed as a monophthong–glide sequence. There is evidence in favor of both analyses. Although the maximal syllable template of Dari is CVCC, diphthongs do not occur in syllables with two coda consonants. This could be taken as an indication that one consonant position is being taken up by a glide. On the other hand, syllables with two consonants are not so frequent as to rule out the possibility of an accidental gap in the lexicon. Conversely, glides do not occur freely in coda position: a monophthongal analysis would then have to stipulate a list of permissible vowel–consonant sequences (i.e. [ʌj], [ɐj], [ɐw], [uj]), which in a sense merely recapitulates the diphthongal analysis. Therefore, though the phonological facts do not force one analysis over another, the diphthongal analysis is adopted here.

In the diagram above, the monophthongs are shown in their approximate locations in F2-F1 space. Two measurements are given for the diphthongs, corresponding to steady states towards the beginning and ends of the diphthongs.

Traditional analyses of Persian have distinguished between long vowels (as transcribed here, [i ʌ u]) and short vowels ([ɛ ɐ o]). Dari does not make a length distinction independent of vowel quality, though there are differences in the lengths of vowels. For purposes of this Illustration, duration measurements were made for the monophthongal vowels of the words produced in isolation. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Vowel duration measurements of monophthongal vowels produced in isolation in the present paper.

An ANOVA shows a general effect of vowel identity on vowel duration: F(7,135) = 3.78, p < .001. The difference in length between traditional long vowels of [i ʌ u] and the short vowels [ɛ ɐ o] is also significant: F(1,141) = 19.20 (p < .001). Finally, the difference is again significant if the Dari long vowel [e] and short vowel [ʊ] are included in the test: F(1,131) = 13.35, p < .001. In summary, then, there are length distinctions in Dari, which are redundant with vowel quality. These correspond to the traditional analysis of Persian short and long vowels.

Syllable structure follows a maximal syllable template of CVCC. The onset is optional; the obligatory epenthetic glottal stop reported by Windfuhr & Perry (Reference Windfuhr, Perry and Windfuhr2009) is not found in Dari (compare the words [ɐˈrɐ] ‘saw (n)’ and [ɐˈdʒɐl] ‘fate’). Windfuhr & Perry (Reference Windfuhr, Perry and Windfuhr2009) note that Arabic loanwords are a source of many complex codas. On nouns, stress is typically syllable-final, including any suffixes and clitics. On verbs, stress falls on the first prefix, or on the last syllable of the root if there is no prefix.

Transcription of recorded passage

The story ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ was adapted by the language consultant from Majidi & Ternes's (Reference Majidi and Ternes1999) Farsi version, to reflect Afghan word choice and usage.

Formal speech style

jɐk ɾoz

bʌd

hɐmˈɾʌjɛ ʌfˈtʌb ‖ ˈkɐti

jɛk

dɛˈgɐɾ dɐˈwʌ ˈmekɐɾdɐnd

ke

kʊˈdʌmɛʃ qɐwiˈtɐɾ ɐs ‖ dɐɾ in

wɐqt

jɐk

mʊsʌˈfɛɾ ɾɐˈsid | ke

jɐk

pɐˈtuje

dɐˈbɐl

dɐɾ ˈdɐwɾɛ xʊd

pe

![]() iˈdɐ bud ‖ ʌnˈhʌ gʊftɐnd

ke | hɐɾ kʊˈdʌmɛ mʌ ke ɐˈwɐl ˈbɛtɐwʌnim

mʊsʌˈfɛɾ ɾʌ mɐ

iˈdɐ bud ‖ ʌnˈhʌ gʊftɐnd

ke | hɐɾ kʊˈdʌmɛ mʌ ke ɐˈwɐl ˈbɛtɐwʌnim

mʊsʌˈfɛɾ ɾʌ mɐ

![]() ˈbuɾ kʊˈnim | pɐˈtujɛʃ ɾʌ ɐz ˈ

ˈbuɾ kʊˈnim | pɐˈtujɛʃ ɾʌ ɐz ˈ

![]() ʌnɛʃ duɾ ˈkʊnɐd | mɐˈlum ˈmɛʃɐwɐd

ke ˈzuɾɛʃ zijʌd ɐst ‖ bʌd

tʌ tɐwʌˈnɛst

wɐˈzid ‖ ˈlekɛn ˈhɐɾ

ʌnɛʃ duɾ ˈkʊnɐd | mɐˈlum ˈmɛʃɐwɐd

ke ˈzuɾɛʃ zijʌd ɐst ‖ bʌd

tʌ tɐwʌˈnɛst

wɐˈzid ‖ ˈlekɛn ˈhɐɾ

![]() e

ke | beʃˈtɐɾ wɐˈzid | mʊsʌˈfɛɾ pɐˈtujɛʃ ɾʌ dɐɾ ˈdɐwɾɛ ˈxʊdɛʃ

e

ke | beʃˈtɐɾ wɐˈzid | mʊsʌˈfɛɾ pɐˈtujɛʃ ɾʌ dɐɾ ˈdɐwɾɛ ˈxʊdɛʃ

![]() ɐmɐ kɐɾd ‖ ˈbɛlʌxɛɾɐ | bʌd

xɐsˈtɐ ʃʊd

wɐ mʊnsɐˈɾɛf ʃʊd ‖ bʌd ɐz ʌn | ʌfˈtʌb

tʌˈbid

wɐ hɐˈwʌ ˈinqɐdɐɾ gɐɾm ʃʊd

ke | ˈfɐwɾɐn

mʊsʌˈfɛɾ pɐˈtujɛʃ ɾʌ ɐz ˈ

ɐmɐ kɐɾd ‖ ˈbɛlʌxɛɾɐ | bʌd

xɐsˈtɐ ʃʊd

wɐ mʊnsɐˈɾɛf ʃʊd ‖ bʌd ɐz ʌn | ʌfˈtʌb

tʌˈbid

wɐ hɐˈwʌ ˈinqɐdɐɾ gɐɾm ʃʊd

ke | ˈfɐwɾɐn

mʊsʌˈfɛɾ pɐˈtujɛʃ ɾʌ ɐz ˈ

![]() ʌnɛʃ duɾ kɐɾd ‖ bʌd ɐz ʌn | bʌd

mɐ

ʌnɛʃ duɾ kɐɾd ‖ bʌd ɐz ʌn | bʌd

mɐ

![]() ˈbuɾ ʃʊd

ke ɛqˈɾʌɾ kʊˈnɐd

ke ɐfˈtʌb ˈzuɾɛʃ zijʌd ɐst

ˈbuɾ ʃʊd

ke ɛqˈɾʌɾ kʊˈnɐd

ke ɐfˈtʌb ˈzuɾɛʃ zijʌd ɐst

Informal speech style

jɐk ɾoz

bʌd ɐmˈɾʌjɛ ɐfˈtɐw ˈkɐti

jɛkidɛˈgɐ dʌˈwʌ ˈmekɐdɐn

ke

kʊˈdʌmɛʃʌn

qɐwiˈtɐɾ ɐs ‖ dɐ i

wɐxt

jɐk

mʊsʌˈfɛɾ ɾɐˈsid | ke

jɐk

pɐˈtuje

dɐˈbɐl

dɐ ˈdɐwɾɛ xʊd

pe

![]() ʌnˈdɐ bud ‖ uˈnʌ ˈgʊftɐn

ke | hɐɾkʊˈdʌme

mʌ ke ɐˈwɐl ˈbɛtʌnim

mʊsʌˈfɛɾɐ mɐ

ʌnˈdɐ bud ‖ uˈnʌ ˈgʊftɐn

ke | hɐɾkʊˈdʌme

mʌ ke ɐˈwɐl ˈbɛtʌnim

mʊsʌˈfɛɾɐ mɐ

![]() ˈbuɾ kʊˈnim

ke | pɐˈtujɛʃɐ ɐz ˈ

ˈbuɾ kʊˈnim

ke | pɐˈtujɛʃɐ ɐz ˈ

![]() ʌnɛʃ duɾ ˈkʊnɐ | mʌˈlum ˈmɛʃɐ ke ˈzuɾɛʃ zijʌdˈtɐɾ ɐs ‖ bʌd

tʌ ke

tʌˈnɛst | wɐˈzid ‖ ˈlʌkɛn | ˈɐɾ

ʌnɛʃ duɾ ˈkʊnɐ | mʌˈlum ˈmɛʃɐ ke ˈzuɾɛʃ zijʌdˈtɐɾ ɐs ‖ bʌd

tʌ ke

tʌˈnɛst | wɐˈzid ‖ ˈlʌkɛn | ˈɐɾ

![]() e

ke

beʃˈtɐɾ wɐˈzid | mʊsʌˈfɛɾ pɐˈtujɛʃɐ dɐ ˈdɐwɾɛ ˈxʊdɛʃ

e

ke

beʃˈtɐɾ wɐˈzid | mʊsʌˈfɛɾ pɐˈtujɛʃɐ dɐ ˈdɐwɾɛ ˈxʊdɛʃ

![]() ɐm

kɐd ‖ ˈbɛlʌxɛɾɐ | bʌd

xɐsˈtɐ ʃʊd

o

mʊnsɐˈɾɛf ʃʊd ‖ bʌd ɐz

u | ɐfˈtɐw

tʌˈbid

o

hɐˈwʌ ˈɛqɐdɐɾ gɐɾm ʃʊd

ke ˈfɐwɾɐn

mʊsʌˈfɛɾ pɐˈtujɛʃɐ ɐz ˈ

ɐm

kɐd ‖ ˈbɛlʌxɛɾɐ | bʌd

xɐsˈtɐ ʃʊd

o

mʊnsɐˈɾɛf ʃʊd ‖ bʌd ɐz

u | ɐfˈtɐw

tʌˈbid

o

hɐˈwʌ ˈɛqɐdɐɾ gɐɾm ʃʊd

ke ˈfɐwɾɐn

mʊsʌˈfɛɾ pɐˈtujɛʃɐ ɐz ˈ

![]() ʌnɛʃ duɾ kɐd ‖ bʌd ɐz

u | bʌd

mɐ

ʌnɛʃ duɾ kɐd ‖ bʌd ɐz

u | bʌd

mɐ

![]() ˈbuɾ ʃʊd

ke ɛqˈɾʌɾ kʊˈnɐ ke ɐfˈtɐw ˈzuɾɛʃ zijʌdˈtɐɾ ɐs

ˈbuɾ ʃʊd

ke ɛqˈɾʌɾ kʊˈnɐ ke ɐfˈtɐw ˈzuɾɛʃ zijʌdˈtɐɾ ɐs

Orthographic version

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the help of Mir Aqa in producing the recordings of the word list and formal version of the text, the anonymous speaker who produced the informal version of the text, and the helpful comments of two anonymous reviewers. The collection of words was made much easier by an otherwise unpublished word list, produced by Ted Feierabend, MD, and made available to me by the Language and Orientation Program of the International Assistance Mission, Kabul, Afghanistan.