Cicipu ([tʃìtʃípù], ISO 639–3 code awc) is spoken by approximately 20,000 people in northwest Nigeria, with the main language area straddling the boundary between Kebbi and Niger states. The language belongs to the Kambari subgroup (not Kamuku as stated by Lewis, Simons & Fennig Reference Lewis, Simons and Fennig2013) of Kainji (Benue-Congo), although it is heavily influenced by the lingua franca Hausa, in which almost all speakers are fluent. There are several identifiable dialects, with native speakers of Cicipu generally listing seven. Of these, Tirisino is the most prestigious and least endangered dialect, and this is the one presented here. Tikumbasi is the most divergent of the dialects, with the /o/ vowel in the other dialects consistently corresponding to /e/ in Tikumbasi (for example /póːpò/ ‘hello’ ~ /péːpè/, /tʃìkóːtò/ ‘drum’ ~ /tʃìkʷéːtè/). The distinction between /o/ and /ɔ/ has been lost in Tikumbasi.

The analysis presented in this Illustration is based on a database of 1400 nouns and verbs not identifiable as loanwords, as well as approximately ten hours of recorded and annotated text. This material was collected during four field trips by the author between 2006 and 2011, funded by the Hans Rausing Endangered Languages Project, the University of London Central Research Fund, and the Kay Williamson Educational Fund, and is available online at www.cicipu.org. For further details on the language see McGill (Reference McGill2009).

Most of the recordings accompanying this account were provided by Tirisino speakers Markus Yabani and Musa Ɗanjuma. At the time of recording, both men were in their 30s and they had lived all their lives in the Tirisino village of Inguwar Rogo, near Sakaba. Some supplementary recordings were provided by Ibrahim Ɗanjuma, Mohammed Mallam, Garba Daniel, and Yabani Ga’allah of the same village. The orthography used in this paper was approved by representatives of the Cicipu community in Sakaba, April 2010.

Consonants

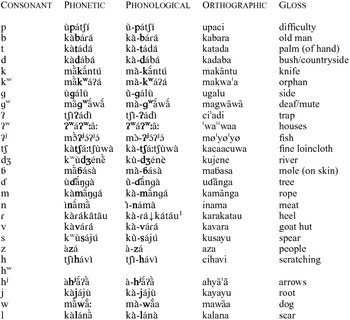

Consonant phonemes

There are 27 consonant phonemes in Cicipu. This number has been arrived at by counting /kʷ/, /ɡʷ/, /ʔʷ/, /ʔʲ/, /hʷ/, and /hʲ/ as single phonemes with secondary articulations, rather than as two-phoneme sequences. This analysis has been adopted in order to avoid admitting onset clusters, which are otherwise absent in the language (see Hyman Reference Hyman1975: 96 for similar logic applied to Igbo); an alternative analysis would be to say that there are only 21 consonant phonemes, and to stipulate /kw/, /ɡw/, /ʔw/, /ʔj/, /hw/, and /hj/ as the only permissible onset clusters.

Every noun word in Cicipu consists of an obligatory noun prefix followed by a stem. In the following list, the relevant phonemic contrasts are the root-initial ones, given after the hyphen.

The phoneme /hʷ/ is marginal in Cicipu. So far it has only been found in the time adverb /hʷ

![]() ʔʲ

ʔʲ

![]() / ‘day before yesterday’ and a number of verbs borrowed from Hausa (e.g. /hʷaːɾa/ ‘start’ from Sokoto Hausa hwara; compare fara in standard Hausa).

/ ‘day before yesterday’ and a number of verbs borrowed from Hausa (e.g. /hʷaːɾa/ ‘start’ from Sokoto Hausa hwara; compare fara in standard Hausa).

Allophonic variation

As well as the labialised and palatalised phonemes which appear in the consonant chart above, there are a number of non-phonemic allophones with these modifications. /m/, /v/, and /s/ have labialised allophones [mʷ], [vʷ], and [sʷ] before the rounded vowels /o/, /ɔ/, and /u/, while /k/ and /ɡ/ have palatalised allophones [kʲ] and [ɡʲ]. [kʲ] occurs before both front vowels /i/ and /e/, whereas [ɡʲ] has only been found before /i/ (contrast /kè

kː

![]()

![]() / [kʲè

kːʲ

/ [kʲè

kːʲ

![]()

![]() ] ‘clapperless bell’ with /ɡéɗù/ [ɡéɗù] ‘above’). Examples follow:

] ‘clapperless bell’ with /ɡéɗù/ [ɡéɗù] ‘above’). Examples follow:

Labialised and palatalised allophones

Before rounded vowels /k/, /ɡ/, /ʔ/, and /h/ do not appear to contrast with their labialised counterparts, and so the underlying consonant in such sequences cannot be determined. Similarly before front vowels /ʔ/ and /h/ do not contrast with their palatalised counterparts. For the phonological transcriptions in this paper, in such cases of neutralisation I have (arbitrarily) chosen the unmodified phonemes (i.e. /k/, /ɡ/, /ʔ/, /h/).

There are only two phonemic nasals in Cicipu, /m/ and /n/. All nasal-consonant (NC) clusters in Cicipu are homorganic, with [ŋ] and [ɱ] occurring before velar and labio-dental consonants, respectively. Examples follow (see below for [ɱ]):

Homorganic nasal-consonant clusters in Cicipu

Morpheme-internal NC clusters are only found when the C is a plosive and the cluster occurs after a nasal vowel; in fact the nasal component could be argued to be absent phonologically (see McGill Reference McGill2009: 109–111 for details). Thus, [ɱv] clusters are only found across morpheme boundaries e.g. /

![]() -vàɾì/ [

-vàɾì/ [

![]() vàɾì] ‘wild dogs’, where the root /-vàɾì/ follows the syllabic nc5 prefix /

vàɾì] ‘wild dogs’, where the root /-vàɾì/ follows the syllabic nc5 prefix /

![]() /.

/.

Ungeminated /ɾ/ is realised as a flap [ɾ], both utterance-initially and utterance-medially, as in /ɾìɓá/ [ɾìɓá] ‘sinkǃ’ and /kà-ɾá↓ká

tá

u/ [kàɾákā

tā

u] ‘heel’. A long /ɾ/ is realised as an approximant [ɹ] as in /ɾː

![]() i/ [ɹ

i/ [ɹ

![]()

![]() ] ‘towns’, optionally followed by a flap [ɾ], for example /ké↓-ɾː

] ‘towns’, optionally followed by a flap [ɾ], for example /ké↓-ɾː

![]() i/ [k

i/ [k

![]() ɹɾ

ɹɾ

![]()

![]() ] ‘of-towns’. Sometimes /ɾ/ surfaces as a mild retroflex/post-alveolar [ɽ] (this can be heard especially in the [k

] ‘of-towns’. Sometimes /ɾ/ surfaces as a mild retroflex/post-alveolar [ɽ] (this can be heard especially in the [k

![]() ɹɾ

ɹɾ

![]()

![]() ] token accompanying this paper, which might be transcribed [k

] token accompanying this paper, which might be transcribed [k

![]() ɹɽ

ɹɽ

![]()

![]() ]). Unlike in Hausa (Newman Reference Newman2000: 394–395), there is not believed to be a phonemic distinction between coronal and post-alveolar flaps.

]). Unlike in Hausa (Newman Reference Newman2000: 394–395), there is not believed to be a phonemic distinction between coronal and post-alveolar flaps.

The approximants /j/ and /w/ have nasalised allophones [

![]() ] and [

] and [

![]() ] which occur in the neighbourhood of nasalised vowels, as shown by /kù-j

] which occur in the neighbourhood of nasalised vowels, as shown by /kù-j

![]() j

j

![]() ː/ [kʷ

ː/ [kʷ

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ː] ‘sand’ and /ù-w

ː] ‘sand’ and /ù-w

![]() ːw

ːw

![]() / [

/ [

![]()

![]()

![]() ː

ː

![]()

![]() ] ‘recovering’, respectively.

] ‘recovering’, respectively.

The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/ sometimes undergo lenition to [ɸ] and [β] when they occur intervocalically, especially in quick speech. For example, /já pù/ ‘two’ may surface as [jáɸù] and /dʒiːbo/ ‘have breakfast’ as [dʒiːβo].

The fricative [ʃ] is non-phonemic, apart from in borrowings such as the Hausa loan shawara [ʃáwáɾà] ‘advice’. In native words the phone only occurs as a variant of /s/ before [i] for some speakers, as in /rúːsì/ [ɾúːʃì] ‘rainy season’; the precise nature of the variation is not understood.

Long consonants

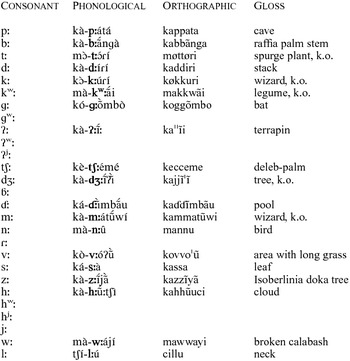

All twenty-seven consonantal phonemes may be geminated, including the glottal fricatives and plosives, and all of these geminates may be found word-initially. This is unusual cross-linguistically (McGill Reference McGill, Blench and McGill2012). Nineteen of these have been found root-initially in nouns:

Root-initial geminates in nouns

The geminate implosive /ɗː/ is realised with an almost complete glottal closure, as evidenced by the apparently zero amplitude and very faint spectrogram bands of /ká-ɗː

![]() mb

mb

![]() u/ ‘pool’ in Figure 1, which contrast with those of /ù-ɗ

u/ ‘pool’ in Figure 1, which contrast with those of /ù-ɗ

![]() nɡà/ ‘tree’.

nɡà/ ‘tree’.

Figure 1

ká-ɗː

![]() mb

mb

![]() u ‘pool’ (left) vs. ù-ɗ

u ‘pool’ (left) vs. ù-ɗ

![]() nɡà ‘tree’ (right).

nɡà ‘tree’ (right).

All except one of the gaps in the list of root-initial geminates in nouns above are covered by the verb forms given in the list of word-initial geminates in verbs below. Although all Cicipu verb roots begin with short consonants, the second person singular realis (2ps\rls) is formed by geminating the first consonant of the root, giving rise to a word-initial geminate. This list contrasts the short consonants found in the imperative forms with the geminates found in the 2ps realis forms. The realis forms are given in two contexts: utterance-initially (e.g. /pːásà/ ‘you(s) crossed’), and then after the independent 2ps pronoun (pro) /ìv

![]() / (e.g. /ìv

/ (e.g. /ìv

![]() pːásà/ ‘you(s) crossed’).

pːásà/ ‘you(s) crossed’).

Geminates occurring word-initially in verb forms

No known verbs begin with/ʔʲː/, one of the rarer phonemes in the language, and so it is not possible to demonstrate a long /ʔʲ/ here.

The data presented in the above list as well as in McGill (Reference McGill, Blench and McGill2012) show that there are morphophonological reasons for postulating word-initial geminates; however, the precise nature of the phonetic differences between word-initial short and long consonants is yet to be investigated experimentally.

Vowels

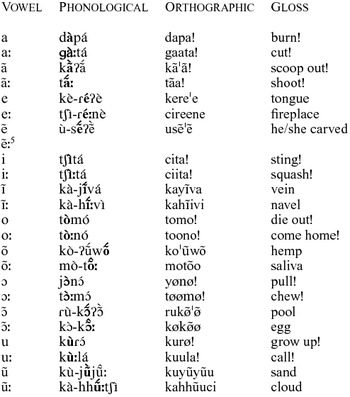

Monophthongs

There are six contrastive monophthongs.

The Bark chart (Figure 2) shows the F1/F2 distribution of the vowels of a single male speaker, measured in Hertz and based on thirty tokens of short oral vowels.

Figure 2 Bark chart of Cicipu vowels.

The lack of a high central vowel phoneme is unusual in (Western) Kainji, where most other languages have two central vowels, /a/ and /ɘ/. A schwa-coloured (i.e. centralised) vowel does occur in Cicipu as an allophone [ö] of /o/ in the environment _CV[+high], that is when the next vowel in the word is /i/ or /u/. Examples include /kò

j

![]() nɡó

lì/ [kò

j

nɡó

lì/ [kò

j

![]() ŋɡʷ

ŋɡʷ

![]() lì] ‘k.o. large ant’ and /dòːsò

nû/ [dòːs

lì] ‘k.o. large ant’ and /dòːsò

nû/ [dòːs

![]() n

n

![]() ] ‘swimǃ’. When such words are pronounced carefully, the surface vowel quality is never [ɘ] or [ə].

] ‘swimǃ’. When such words are pronounced carefully, the surface vowel quality is never [ɘ] or [ə].

/i/ may be optionally realised as [u] in the neighbourhood of a rounded vowel; the following example shows both /ɡutu/ and /ɡitu/ in almost identical environments.

-

(1)

Matters are further complicated by the influence of the approximant /j/ on a preceding /u/, or conversely /w/ on a preceding /i/. For example, /ɡuja/ ‘be able to’ is pronounced [ɡʷija] (demonstrated by the verb form /íɡːù

jà/ [íɡːʷìjà] ‘you(s) should be able to’; note verbs in Cicipu are inherently toneless – see below), and /tì-w

![]() m

m

![]() / ‘chieftaincy’ is pronounced [tù-w

/ ‘chieftaincy’ is pronounced [tù-w

![]() m

m

![]() ]. In general, the distribution of the high vowels /i/ and /u/ is problematic, just as in Hausa (Newman Reference Newman2000: 399–400).

]. In general, the distribution of the high vowels /i/ and /u/ is problematic, just as in Hausa (Newman Reference Newman2000: 399–400).

Vowel length and nasalisation

All vowels contrast in both length and nasality. Short vowels are more common than long vowels, by a ratio of approximately 7:1 in the lexicon. Oral vowels are considerably more common across the lexicon than nasal vowels, with a ratio of about 5:1 in the words collected so far. Examples are listed here:

Diphthongs

Cicipu has the following diphthongs, all of which are falling (i.e. from an open to a closed vowel quality): /ai/, /au/, and perhaps /ei/ and /eu/ (see below).

Other than in borrowed words, diphthongs are limited to root-final position (of either mono- or multi-syllabic roots). Thus, they differ from both short and long vowels in their distributional properties: short vowels do not occur in monosyllabic roots, and long vowels occur as the last vowel of a multi-syllabic root only rarely.

Almost all diphthongs are nasalised (discounting loanwords); the only two attested exceptions involve /au/: /tʃːátʃáu/ ‘ankle bracelet’ and /kà-ɾá↓ká tá u/ ‘heel’.

Evidence from related languages and loanwords such as /kà-nà

bâ

i/ ‘account’ (Hausa labari) and /kà-l

![]() z

z

![]() i/ ‘horse bit’ (Hausa linzami) suggests that Cicipu diphthongs have come about due to the loss of a consonant which previously separated two different vowels.

i/ ‘horse bit’ (Hausa linzami) suggests that Cicipu diphthongs have come about due to the loss of a consonant which previously separated two different vowels.

The distribution of /ei/ and /eu/ is problematic, and it has not been possible to find good contrasts with /

![]() ː/, with analysis hampered by the rarity of all of these sounds. In the examples collected so far, [

ː/, with analysis hampered by the rarity of all of these sounds. In the examples collected so far, [

![]() i] occurs only after /d ɡ k

p

s

t/, [

i] occurs only after /d ɡ k

p

s

t/, [

![]() u] occurs only after /n

z/, and [

u] occurs only after /n

z/, and [

![]() ː] occurs only after /b/. It would therefore be theoretically possible to analyse all of these as allophones of /

ː] occurs only after /b/. It would therefore be theoretically possible to analyse all of these as allophones of /

![]() ː/, reducing the number of diphthongs to two.

ː/, reducing the number of diphthongs to two.

These sounds are analysed as diphthongs rather than vowel–glide sequences for phonotactic reasons, since there are no unambiguous word-final codas in Cicipu. However, a bi-syllabic analysis could also be appropriate.

Vowel harmony

There is widespread vowel harmony in Cicipu, of the kind called ‘total’ by Aoki (Reference Aoki1968: 142; see also Hyman Reference Hyman1975: 234 on vowel copying/reduplication). This harmony is manifest not just as a distributional constraint operating on all word classes within the lexicon but also as an active process affecting many nominal and verbal affixes.

The six vowels can be divided into (i) the four non-high vowels {o, ɔ, e, a}, which form a set of mutually exclusive harmonic counterparts, and (ii) the two high vowels {i, u}, which are neutral and so may occur with any vowel from the first set. Vowels from the first set {o, ɔ, e, a} are mutually exclusive in roots, regardless of word class. So if a root contains /a/, its other vowels must come only from the set {a, i, u}, /e/ only occurs with {e, i, u}, and so on. Put more concisely:

-

(2) If there are two [–high] vowels in a phonological word then they must be identical.

The vowel harmony system operates across all lexical roots, apart from some borrowings. Table 1 shows the distribution of V1 and V2 in native CVCV noun roots where both Vs are short and oral (there are 274 such roots in the database used for this study).

Table 1 Vowel co-occurrence restrictions in CVCV noun roots where V1 and V2 are both short oral vowels (V1 down the left, V2 along the top).

Vowel harmony in words is root-controlled. Affixes vowels are either /i u/, or a harmonising vowel, written here as /A/; there are no invariant affix vowels from the harmonising set {o, ɔ, e, a}. Thus, for example, the nc1 class prefix /kA-/ has four allomorphs {ko, kɔ, ke, ka}, as illustrated in the following:

If the stem contains only high vowels, then the affix vowel usually surfaces as [a], as in /k à-kú lù/ [kà kʷú lù] ‘hailstone’ (but see below).

The high vowels /i/ and /u/ are neutral and usually transparent, as illustrated by (3)–(5) (see McGill Reference McGill2011 for some exceptions to transparency).

-

(3)

-

(4)

-

(5)

In some words, the mid vowels [e] and [o] (or [ɔ]) may surface unexpectedly as affix vowels. A case in point is the word [n

![]() jù-n

jù-n

![]() ] ‘send/rls-vent’ from (1) above. The ventive suffix is underlyingly -na, and so we should expect [n

] ‘send/rls-vent’ from (1) above. The ventive suffix is underlyingly -na, and so we should expect [n

![]() jù-n

jù-n

![]() ] here. This is an instance of an optional (i.e. lexically-specified) process of affix vowel assimilation which occurs when the root contains only high vowels, whereby an affix vowel a is realised as either:

] here. This is an instance of an optional (i.e. lexically-specified) process of affix vowel assimilation which occurs when the root contains only high vowels, whereby an affix vowel a is realised as either:

-

• [e], if the root contains only /i/, as in (6)), or;

-

• [o] (or sometimes [ɔ]), if the root contains only /u/, as in (7)), or a mix of /i/ and /u/, as in (8)) and (9)).

In contrast, in the (b) examples no assimilation has taken place and these forms are consistent with the vowel harmony process described above. It is not yet known if there is any way to predict whether this assimilatory process will apply.

-

(6)

-

(7)

-

(8)

-

(9)

Note that the (a) forms are not disharmonic according to (2) above, since they only contain a single non-high vowel – it is just that (2) alone cannot explain why the prefix surfaces with a mid vowel. For further examples see McGill (Reference McGill2011).

Anderson (Reference Anderson and Hyman1980) briefly discussed prefix–root vowel harmony in nouns for the Eastern Kainji language Amo. He states that ‘[t]hough this vowel harmony may provide a phonetic “target”, considerable variation still exists even on individual words’ (Reference Anderson and Hyman1980: 157). This is true for Cicipu affix-vowel harmony to some extent, especially in the Tidipo dialect. An example of failure to harmonise in Tirisino can be seen in the token [à kʲíːsʷó] ‘spirits’ in the list of labialised and palatalised allophones above (compare example (10) from the same speaker).

-

(10)

Tone

Cicipu vowels are found with two contrastive tones: H and L, with contour tones being found on long vowels and diphthongs. Examples of contrast are given in the list below; see also the verb forms in the list of geminates occurring word-initially in verb forms above, which illustrate tone contrast in monosyllabic words.

Tone contrasts

Predictable tones in verbs

Verb lexemes are inherently toneless, deriving their surface tones from their Tense-Aspect-Mood properties (such systems are called ‘predictable’ by Kisseberth & Odden Reference Kisseberth, Odden, Nurse and Phillipson2003: 61). Perhaps the most important grammatical function of tone in Cicipu is to mark the distinction between realis and irrealis mood. Other than the 2ps form (where there is also a segmental difference), it is only the tone which distinguishes the two moods: compare /ù-dú kʷà/ ‘he/she went’ with /ú-dù kʷà/ ‘he/she should go’. In the orthography, irrealis verbs are written with an acute accent over the first vowel, for example, údukwa.

Falling or rising tones can occur phonetically as a consequence of applying a particular tone pattern to a long vowel, diphthong, or sequence of two vowels. This is illustrated by example (11), where the first two tones of the realis LHL pattern fall on the long vowel.

-

(11)

Note that while LH tones can arise from the overlay of grammatical tone patterns, they are never lexically specified.

Downdrift and downstep with ‘Plateauing’

Tones in Cicipu utterances undergo automatic terraced downdrift within each intonation group, whereby the pitch of each H is lower than that of the one before. Successive L tones also decline in pitch, but by less, and thus the distinction between H and L is less towards the end of an intonation group than at the beginning.

Non-automatic downstepped H tones also occur. For example, in the post-verbal complement position of non-imperative clauses, objects whose initial vowel is underlyingly H always surface at the same pitch level as the previous (underlying) L. Subsequent L tones are even lower. Examples (12)–(14) demonstrate three phonetic levels of pitch in realis clauses (for these examples, there are accompanying whistle tracks produced by the speaker). The phonetic pitch of these utterances can be explained by assuming a ‘Plateauing’ rule (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith1990: 36), causing HLH to become H↓HH. Thus, in (12), for example, underlying /t

![]() ndà

ká

sːà/ is realised as [t

ndà

ká

sːà/ is realised as [t

![]() nd↓á ká

sːà] by the delinking of the L from the /a/ of /t

nd↓á ká

sːà] by the delinking of the L from the /a/ of /t

![]() ndà/ to become a floating tone, and the consequent backward spreading of the H tone of /ká

sːà/.

ndà/ to become a floating tone, and the consequent backward spreading of the H tone of /ká

sːà/.

-

(12)

-

(13)

-

(14)

The same phenomenon has been observed in a heterogeneous set of syntactic environments (see McGill Reference McGill2009: 137–139), which suggests a more general description is possible.

Transcription

The text provided is Markus Yabani's retelling of the Hausa audio version of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’.

Phonemic transcription

Vowel elision and coalescence are common at word boundaries, with the rightmost vowel quality usually dominant, e.g. /ámbè l êː úː wâːjà/ (line 5) surfaces as [ámbèl úː wâ ajà]. As discussed above, certain grammatical constructions induce tonal downstep, and where this occurs word-internally, it is indicated by ↓. Downstep at word boundaries (e.g. between a verb and its complement) is not marked here. Rightward-spreading of high tones is common, and this too has been omitted. Tense-Aspect-Mood tone patterns superimposed on verbs are glossed using a backslash (e.g. 3p-do\rls).

Orthographic transcription

Kanabai kampa kanabai k-ulenji ke, n-upepi. Kwaakulle go, ulenji n-upepi wu-kkudu, wu-saˈa v-uyeyu, ayãa gaddama. Ulenji wuhyãa wuɗaa upepi uˈũsũ. Upepi wu-kkudu kuma wu-saˈa v-uyeyu, uhyãa uɗaa ulenji uˈũsũ. To kwaakulle, sei ga wuna zza wuutono kudu in mettegu meevi m-uyeyu, uyũuni. Degelee, mettegu mana kuma, uvãˈã me, uvãˈilã me kam kam. Degelee upepi wuhyãa to, indu ambe lee u-uwaaya. Waya ugwada uˈũsũ weevi. Degelee ana waayana uˈungono bu-bu-bu-bu. Uˈosu ˈesenu, uˈosu ˈesenu, uˈosu ˈesenu. Mettegu melle, uguya ce up

![]() ˈ

ˈ

![]() me, uguya ce up

me, uguya ce up

![]() ˈ

ˈ

![]() zza ville mettegu. Degelee, uyãa uyãa uyãa uyãa uyãa uyãa, uyãa iyaaka v-uguyaani weevi, uyãa iyaaka v-uˈũsũ weevi, uguya ce. Degelee, waya ucaa kalaahiya, waya usallama zza ville. Degelee, ulenji waya uhyãa to indu ambe lee u-uwaaya. Ulenji waya wuutono. Ana wuutonno, uhwaara ugwaruwana. Uˈesu ugwaruwana, uˈesenu usiɗi. Wuyãa usiɗi, uˈosu ucaa usiɗi g

zza ville mettegu. Degelee, uyãa uyãa uyãa uyãa uyãa uyãa, uyãa iyaaka v-uguyaani weevi, uyãa iyaaka v-uˈũsũ weevi, uguya ce. Degelee, waya ucaa kalaahiya, waya usallama zza ville. Degelee, ulenji waya uhyãa to indu ambe lee u-uwaaya. Ulenji waya wuutono. Ana wuutonno, uhwaara ugwaruwana. Uˈesu ugwaruwana, uˈesenu usiɗi. Wuyãa usiɗi, uˈosu ucaa usiɗi g

![]() i. Degelee, zza ville wuuwa caaˈwãi tidaamukwi vi. Evi in kat

i. Degelee, zza ville wuuwa caaˈwãi tidaamukwi vi. Evi in kat

![]() i keevi waaya, up

i keevi waaya, up

![]() ˈ

ˈ

![]() mettegu.

mettegu.

Interlinear version

Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

I have enjoyed discussions on Cicipu phonology with David Crozier and Sophie Salffner, and I am also grateful to an anonymous reviewer for many helpful comments and suggestions.