No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 June 2009

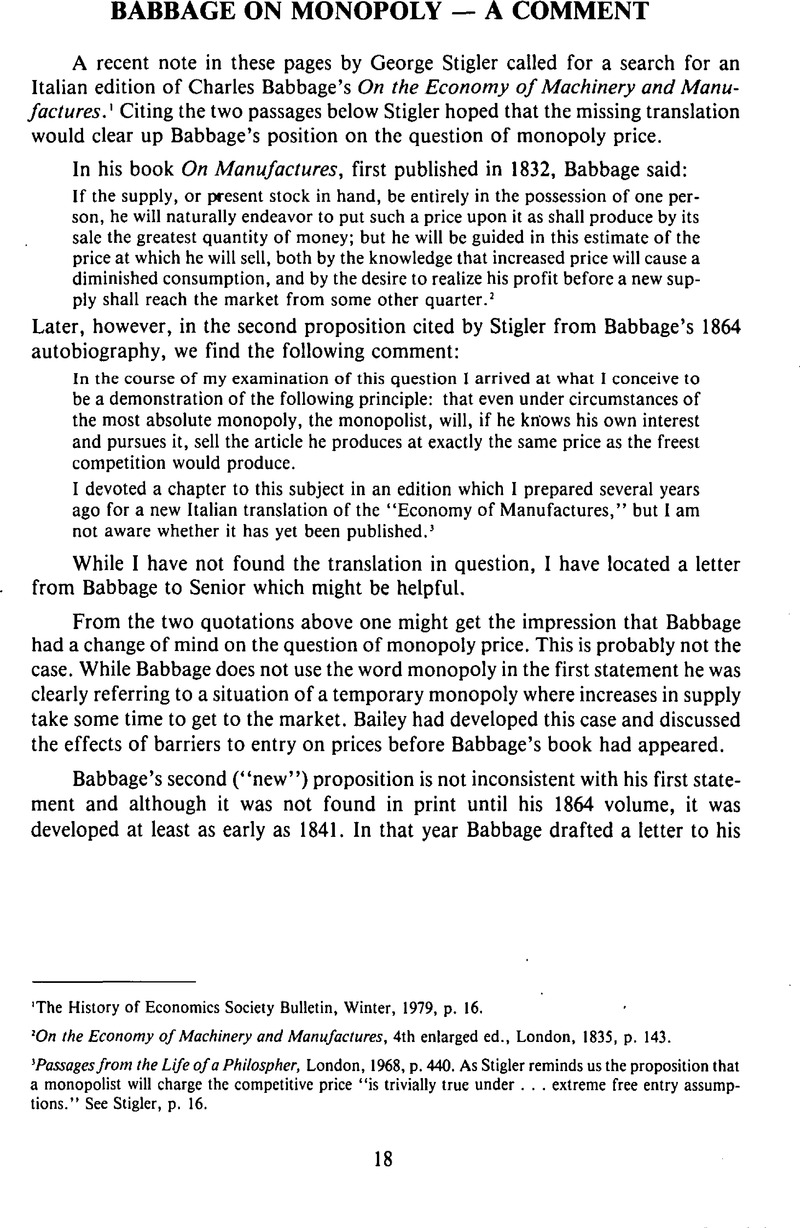

1 The History of Economics Society Bulletin, Winter, 1979, p. 16Google Scholar.

2 On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, 4th enlarged ed., London, 1835, p. 143Google Scholar.

3 Passages from the Life of a Philospher, London, 1968, p. 440Google Scholar. As Stigler reminds us the proposition that a monopolist will charge the competitive price “is trivially true under … extreme free entry assumptions.” See Stigler, p. 16Google Scholar.

4 B. M. Add. Mss. 37, 191, fos 695–96. The relevant portion of the letter follows. I have bracketed those parts which were either unclear to me or were crossed out by Babbage in a correction of the draft.

My view is

That the price which will be charged under the most absolute monopoly is, if the monopolist knows his own interest, the same as he would charge under free competition.

That the evils of monopoly [depend] on other causes.

When the monopolist has no rival the price he will charge for each article is regulated by that price which yields him the ….

(Babbage probably meant to follow this with the words “greatest quantity of money.” See quote from On Manufactures above).

I sent you a MSS on the first [part of] the question when the supply the monopolist can produce is unlimited. If the supply is limited the same principle prevails and even if a government were to compel him to sell at a cheaper rate the public would receive no benefit from the interference.

Suppose the North Western Railway could not carry more than 4000 persons to Birmingham in each day and suppose 6000 persons wanted to go if the expense were [10 sh. each]. The company would naturally raise the price until only 4000 would pay it. Let us suppose 20 sh. to be that price. Now if government were to compel the [company] to charge only 10 sh. for each traveller the public would still have to pay 20. For a class of middlemen would immediately arise who would [ ] purchase all the seats for sometime beforehand. These would retail them to individual travellers as there are by supposition 4000 willing to pay 20 sh. The middlemen would sell all their tickets and make a great profit. This has been the case frequently with tickets at the opera.

The example which Babbage gives does not help us fully understand his position. It merely says that under conditions of fixed supply if the government attempts to set a price below the equilibrium level, black markets will develop and the consumers will not pay the lower price. He does not elaborate on why the monopolist would charge the competitive price under these conditions but it is clear from his railroad example that its revenue would be the same by doing so.

5 I have verified this only through correspondence.

6 Bowley, Marian, Studies in the History of Economic Thought Before 1870, London: Macmillan, 1973, pp. 161–69CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Discusses Senior and Bailey on barriers to entry.

7 On Manufactures, viii–ixGoogle Scholar.

8 Ibid., p. 361.

9 Babbage did seem to recognize the possible advantage of a natural monopoly. This situation may occur in the “supply of water or gas … docks, canals, railroads, etc., and in other cases where the capital required is very large, and the competition is very limited.” In these cases the price should not be left “to the discretion of the monopolists” but the government might regulate the profit rate to protect the public. Ibid., p. 313.

10 This note was adapted from a longer article on Babbage which will be published in HOPE. My research has been supported by the State University of New York Research Foundation and has benefited from discussions and correspondence with Professor Stigler.