I. INTRODUCTION

I wrote this address during the first weeks of the murderous and devastating invasion of Russia in Ukraine, in a fluctuating mood of anger and sadness. My aim was addressing the issue of the use of history to legitimize ideology, and I was contemplating how I could convince you of the urgency of this issue, and then this war broke out.

Putin had legitimized his war by an essay, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” already published on July 12, 2021.Footnote 1 In this essay he writes that Russia and Ukraine are “essentially the same historical and spiritual space” and thereby denies the existence of a separate Ukrainian culture, language, and identity. To show this, he draws a history covering a period of “over more than a thousand years,” by focusing “on the key, pivotal moments that are important for us to remember, both in Russia and Ukraine.” The “spiritual space” was supposed to be determined by a common language, what he called “Old Russian,” and a common “Orthodox faith.” It is an essentialist legitimation, which Karl Popper (Reference Popper1994), in his Open Society and Its Enemies, had criticized profoundly. In his analysis of the legitimation Nazi Germany used for its invasions, Popper found its roots in Georg Hegel’s historical theory of the nation, according to which a nation is united not only by a language but also by a “Spirit” that enfolds in history.

Because history can be used not only as a legitimation of an ideology but also as its weapon, we, historians, must critically reflect on our work and see where we can abandon any opportunity for such abuse.Footnote 2

II. LOOKING IN THE MIRROR

A good starting point for such a self-reflection is the symposium on “Misusing History,” organized by Roy Weintraub in 2005 and published in History of Political Economy. Weintraub (Reference Weintraub2005, p. 178) had “asked a number of prominent historians of economics for their favorite example of how a modern economist, mainstream or heterodox, has constructed a spurious past, one known to be inconsistent with the historical evidence.” Even though Weintraub had approached only those who in his eyes are historians of economics, and assumed that the misuse takes place only at the side of the modern economists, I nevertheless consider this symposium as a good first step of self-reflection. Namely, most of the members of the History of Economics Society have a training in economics and a position as economist; only a few have a position as historian or something else. A long-heard argument is even that for doing history of economics, one should be an economist; an argument that already can be found in one of the founding papers of the “revival” of history of economics, Alfred (“Bob”) Coats’s “Research Priorities in the History of Economics.” He saw “a real danger” when history of economics would be left to “sociologists or intellectual historians, few of whom understand the economist’s intellectual equipment and distinctive point of view” (Coats Reference Coats1969, p. 16).

The second reason why I see this symposium on misuse of history as a first step of critical self-reflection is because of Evelyn Forget’s (Reference Forget2005) contribution to this symposium, “Same View, Many Lenses,” in which she makes clear that “we can correct error related to particular historical events, but we delude ourselves if we believe that a definitive history is possible” (p. 210). It is important to have the facts correct, but these facts are not the most important part of history. Her contribution is to show that “history is about identity” (p. 209). History confers identity because historical facts allow more stories to be told.

Between any two points in time lies an infinite density of historical events. The veracity of each of these events can be known, with more or less certainty, depending on the quality of the archival record and the diligence of the historians mining it. Fact checking, however, is a very minor part of constructing histories. The art of writing history lies in distinguishing between relevant and irrelevant events, establishing beginnings and endings, and building narrative bridges between the relevant events in such a way as to establish meaning. It follows that any two or more points in time can be linked in a very large number of ways. Multiple histories are not only conceivable but usual, and no amount of fact checking will eliminate them. (Forget Reference Forget2005, p. 205)Footnote 3

Forget distinguishes three tasks: first, the establishment of facts, though she emphasized that it is the meaning they imply that is considered to be more relevant to historians. The second task is to “demonstrate the possibility of multiple, equally valid, histories to those convinced of the objectivity of their own story. This involves collecting and documenting the various histories that are constructed, knowingly and unknowingly, by those with a stake in the telling” (pp. 205–206). The third, and according to Forget the most important, task is to help people to understand the implications of various ways of telling history.

Forget presents history as an empirical science, and as every empirical scientist knows, facts allow for many equally validated models. We should be aware of this, but her main message is that because of this possibility of a multiplicity of historical narratives, history can be used to define identity.

A similar message was presented by Lorraine Daston in her essay The History of Science as European Self-Portraiture, in which she shows that “no other culture [than the European] has relied so heavily on the history of science to define its own identity” (Daston Reference Daston2005, p. 30).

This essay was written for the occasion that in 2005 the Erasmus Prize was awarded to two historians of science, Simon Schaffer and Steven Shapin. The Erasmus Prize is awarded annually to “a person or institution that has made an exceptional contribution to the humanities, the social sciences or the arts, in Europe and beyond” (erasmusprijs.org; accessed January 20, 2023), and derives its name from the Dutch humanist scholar Desiderius Erasmus. In the choice of its laureates, the importance of tolerance, cultural pluriformity, and non-dogmatic critical thinking is most valued. To give a general impression about the diversity of laureates, the first prize in 1958 was given to the Austrian People, the 1967 prizewinner was Jan Tinbergen, and the most recent award went to the Israeli writer David Grossman.

“History of Science” was the theme of 2005, and Schaffer and Shapin were nominated because they

have changed the way people think about the history of science and its complex relationship with culture and society. They have shown how science and society are not separate entities that exist independently, and either influence each other or not. Instead, the practice of science, both conceptually and instrumentally, is seen to be full of social assumptions. Crucial to their work is the idea that science is based on the public’s faith in it. This is why it is important to keep explaining how sound knowledge is generated, how the process works, who takes part in the process and how. (erasmusprijs.org)

While Schaffer and Shapin showed how fundamental innovations in science such as the emergence of experiment as a method of inquiry was linked to coeval political and social events, Daston emphasized that “the history of science had long been central to another, quite different narrative that traced connections between scientific knowledge and a certain characteristically modern—and European—social order” (Reference Daston2005, p. 11): “Post-seventeenth-century European science, and to some extent technology, was taken as evidence of the gap between—and superiority of—European culture with respect to all others, everywhere and always” (Daston Reference Daston2005, p. 12; italics are mine).

The very understanding of Europe as a cultural unity was part of this narrative. By the end of the seventeenth century, European geographers, as Daston argued, were describing Europe as not just a continent but a culture. The sciences were wielded as a proof of European cultural superiority.

Daston showed that this science-defined European culture was based on two closely connected ideals: liberty and progress, illustrated with Jean d’Alembert’s statement (quoted in Daston Reference Daston2005, p. 14): “For liberty of action and thought alone is capable of producing great things, and liberty requires only enlightenment to preserve itself from excess.” A liberal social order was, according to d’Alembert and many other Enlightenment intellectuals, a precondition for the spectacular progress of the sciences.

This creation of a history of European culture of progress and liberty, based on a history of science, has, however, the essentialist characteristics that actually endanger these two European ideals of progress and liberty. It is what Popper called “historicism” and what he saw as a threat to liberty and progress in both science and society.

This brings us back to our original problem of how to separate history from essentialist tendencies, but now formulated more precisely: How can we avoid the fact that one identity is seen as more superior than others? The answer is to better understand when a history is seen as most superior. In science, the most superior view is the most objective one. So let us investigate what that means.

III. A VIEW FROM SOMEWHERE

According to the received view of science, the objective view is the “view from nowhere.” Thomas Nagel (Reference Nagel1986) discussed objectivity in terms of taking more “distance,” of “stepping back.” An objective standpoint is supposed to be created by step by step, “leaving a more subjective, individual, or even just human perspective behind” (p. 7), until one reaches a most distant perspective-less point, which is the point of nowhere.Footnote 4

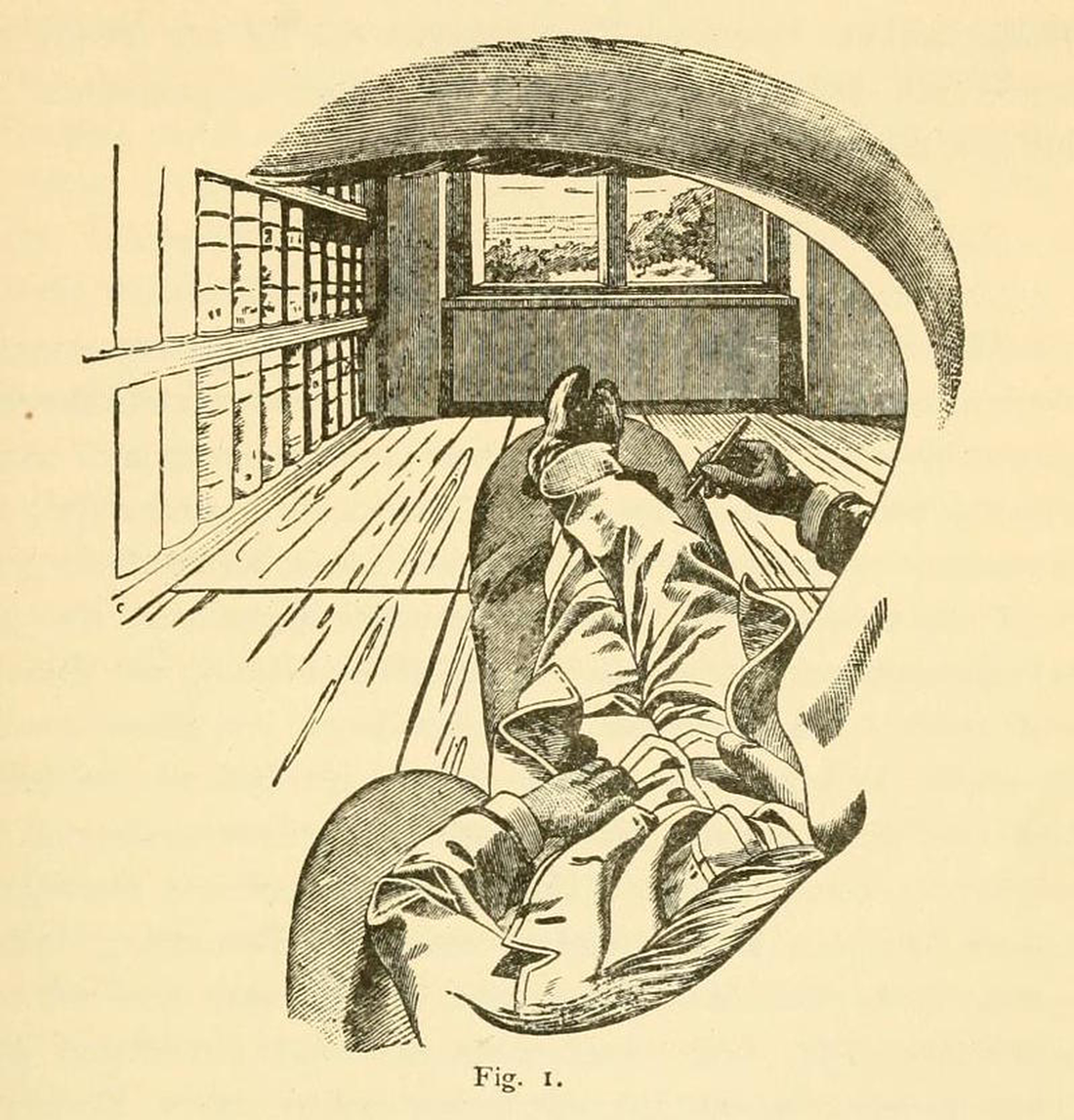

Nagel argues, however, that an objective view is possible only if “we place ourselves in the world that is to be understood” (Reference Nagel1986, p. 4; italics are mine). For Ernst Mach (Reference Mach1959, p. 3), the point of view for an empirical science was what he called the “Ego,” that is “the complex of memories, moods, feelings, joined to a particular body (the human body).” In a drawing (see Figure 1), “to carry out the self-inspection of the Ego” (Mach Reference Mach1959, p. 20 n2), Mach depicted the continuity between his Ego, his body, and the world around him.

Figure 1. View from the Left Eye, drawn by Ernst Mach.

Source: Mach Reference Mach1959, p. 19, Figure 1.

What is most striking of this drawing is the consequential strong perspective. In case of a view from nowhere, perspective does not play a role, because there is no standpoint. But for a view from in the world, from an Ego, it can only be perspectival. To better understand the view from a specific standpoint, the basic principles of perspective must be explored.

IV. SEEING IT IN PERSPECTIVE

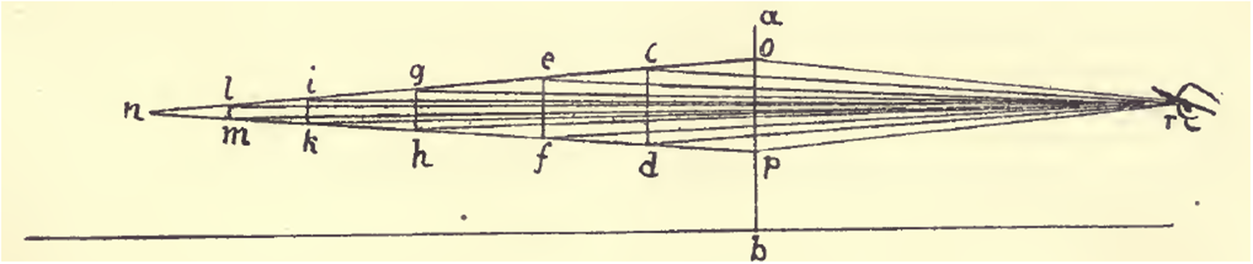

The basic principles of perspective, as applied to representational painting, were developed for the first time during the Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci was one of the foremost exponents of this new approach, particularly because of his geometric theory of perspective. According to da Vinci (quoted in Richter Reference Richter1883, p. 56), perspective “makes use of two opposite pyramids, one of which has its apex in the eye and the base as distant as the horizon. The other has the base towards the eye and the apex on the horizon.” By the first “pyramid of lines” he meant “those lines which start from the edges of the surface of bodies, and converging from a distance, meet in a single point” situated “in the eye which is the universal judge of all objects” (p. 32). These two pyramids intersect at a certain plane (see Figure 2): “Perspective is nothing else than seeing a place [or objects] behind a plane of glass, quite transparent, on the surface of which the objects behind that plane of glass are to be drawn. These can be traced in pyramids to the point in the eye, and these pyramids are intersected on the glass” (da Vinci quoted in Richter Reference Richter1883, p. 53).

Figure 2. “ab must be imagined as the plane of glass,” drawn by Leonardo da Vinci.

Source: Richter Reference Richter1883, p. 35.

These principles show that for a perspective, one needs not only a viewpoint (r in Figure 2) and, equally important, a chosen point on the horizon (n in Figure 2), but also a decision where to position the glass plane (line ab in Figure 2), later called “da Vinci’s window.” The scope of scenery that one can view through the window depends on the position of the window. Thus, besides choosing a viewpoint and a horizon, one has also to choose the scope of the scenery.

But seeing is not only receiving light rays on our eyes; it is also the cognitive activity of organizing the light rays into meaningful wholes. Seeing is the ability of perceiving a coherent visual world that is organized into meaningful objects rather than the chaotic juxtaposition of different colors that stimulate the individual retinal receptors (see Palmer Reference Palmer1999). Seeing is a sense-making activity.

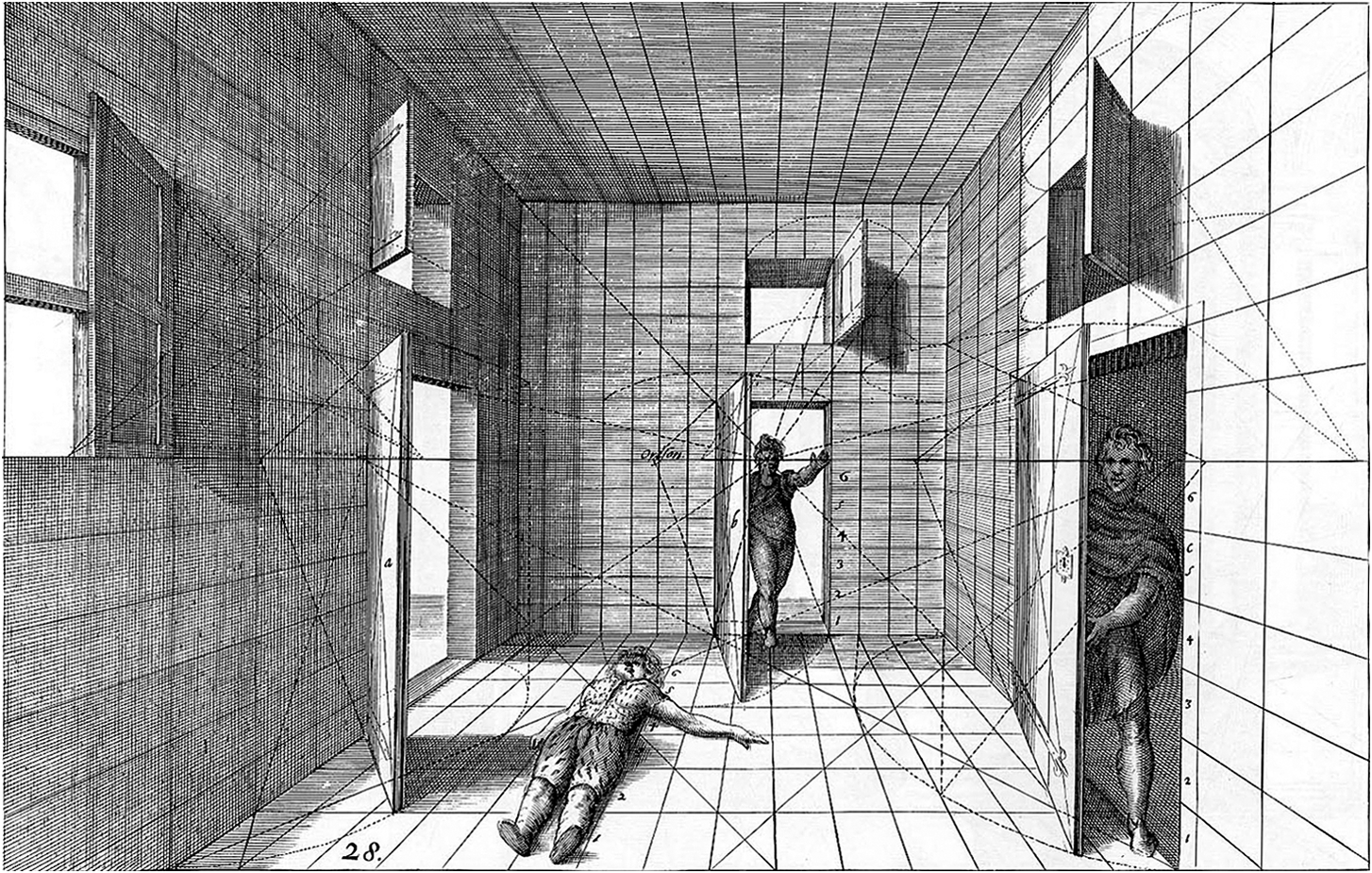

To make sense of a scenery, we turn it into a scene; that is, we make it part of a story. Take, for example, the following engraving (see Figure 3) by Jan Vredeman de Vries, a Dutch painter and architect who wrote and illustrated Perspective (Reference Vredeman de Vries1968), originally published in 1604 and 1605, which became in the seventeenth century one of the major guidebooks on perspective for designers, painters, and architects. Perspective includes a number of scenes and projections employing one- and multi-point perspective.

Figure 3. Perspectival Scene.

Source: Vredeman de Vries Reference Vredeman de Vries1968, Plate 1–28.

In his book The Scientific Image, Harry Robin commented on this engraving in the following terms: “As with many others in de Vries’s book, this scene has a faintly disturbing undercurrent. Is the supine figure the victim of a crime? Is the man behind the door at the right the criminal? And is the visitor entering the room at the distant door—which is also the vanishing point of the drawing—the discoverer of the crime?” (Robin Reference Robin1992, p. 203). To make sense of this scenery, Robin turns it into a crime scene.

Etymologically, history and story have the same root; both are narrativizing activities. In her recent account of narratives, Mary Morgan (Reference Morgan, Morgan, Hajek and Berry2022) shows that narrativizing can be understood as a sense-making technology for science.

According to Morgan (Reference Morgan, Morgan, Hajek and Berry2022), the quintessential feature of narrativizing is that it shows how things relate together, so that constructing a narrative account in science involves figuring out how the elements of a phenomenon are related to each other, in order to form a coherent account of the phenomenon. She argues that, “Narrativizing serves to join things up, glue them together, express them in conjunction, triangulate, splice/integrate them together (and so forth)” (p. 12). As such, a narrative can be understood as a colligation in the sense William Whewell has given to this term. Whewell used the term “colligation” for the binding of a number of isolated facts by a general notion or hypothesis. “Colligation of Facts” is a term that may be applied “to every case in which, by an act of the intellect, we establish a precise connexion among the phenomena which are presented to our senses” (Whewell [1840] Reference Whewell2014, p. 202).

But not every colligation is a narrative. According to Morgan, the colligation must take place on a “grid.” She observes two main sense-making grids that play a role in narrativizing. One grid is a possible network of relationships as the main device for ordering materials and the other grid is the ordering of elements along space or time lines. The relational grid is a network pattern depicting a set of relationships of various kinds; they can be causal, mechanistic, or associational. The benefit of colligating on a network grid is that the resulting narrative can be “opaque about the exact nature of those relations; it can allow knowledge to be uncertain; it can allow for multiple perspectives; it can enable complexity to be maintained; and it can embrace context where the cut between content and context is unclear” (Morgan Reference Morgan, Morgan, Hajek and Berry2022, p. 14).

Narrativizing is also in another sense more than colligating. It is not only joining things up; sometimes the need to clarify relations between these things means that scientists have first to sort things out so that the relationships can be seen more clearly. Sometimes the sorted-out things are joined in a different order or set of relations than they first appear. This sorting out and putting back together could involve a set of more heterogeneous observations, coming in different forms from different observers in different places, contributing diverse information in the empirical domain.

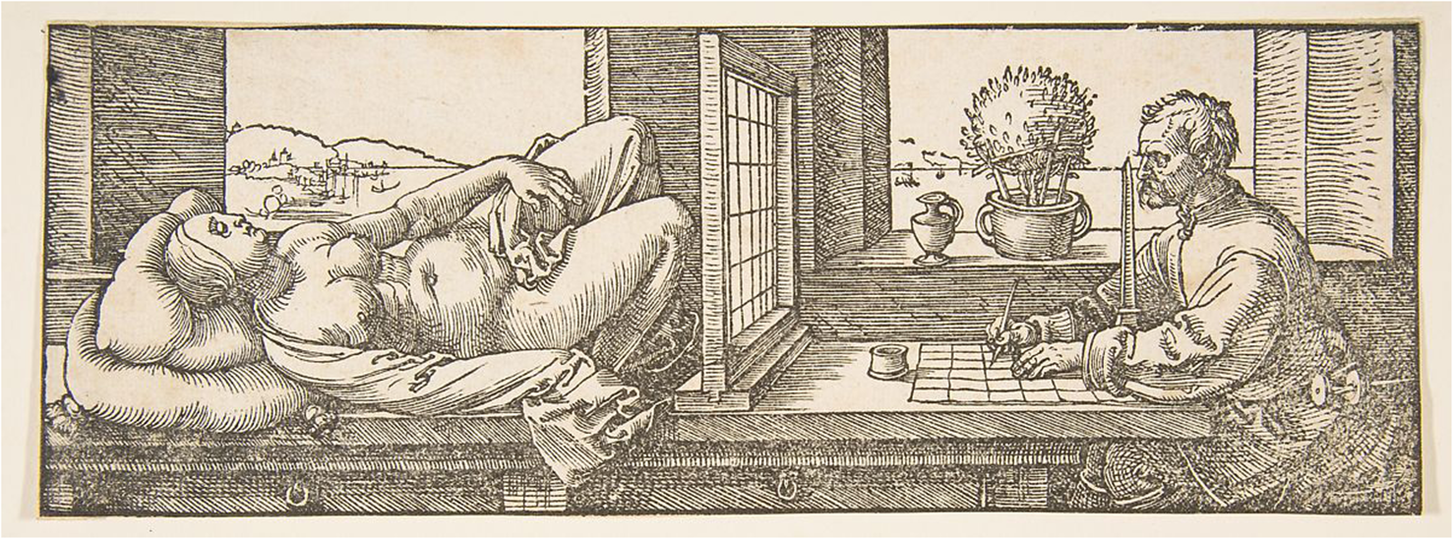

This account of narrativizing can be related to da Vinci’s theory of perspective, in which the grid is the window. But it also shows that this theory of perspective is not sufficient to understand objectivity; it misses the sorting-out part of narrativizing. Take, for example, Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut Draughtsman Making a Perspective Drawing of a Reclining Woman (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Draughtsman Making a Perspective Drawing of a Reclining Woman, by Albrecht Dürer.

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Henry Walters, 1917.

It shows clearly da Vinci’s window as a grid, and the viewpoint is represented by the obelisk, but the most striking aspect of this woodcut is the contrast between what is shown at both sides of this grid. It is a clear illustration of the various kinds of dichotomies that play a role in science, representing implicit scientific values, such as subjectivity/objectivity, subject/object, female/male, and passive/active, as well as issues of sexuality, male gaze, and voyeurism—dichotomies that are discussed in detail by Evelyn Fox Keller (Reference Keller1985). This woodcut is a nice illustration of the value-ladenness of any scientific perspective, in Dürer’s drawing represented by the draftsman’s gaze.

V. THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS

What are the subjects we wish to sort out, what are the topics we are interested in, what are the objects we would like to pay attention to? Looking at the history of portrait art, the people who are usually portraited are those who are considered to be successful and often painted with the aim of showing their success. The paintings of historical scenes are usually paragons of victory. The unsuccessful only figure in the background to emphasize the successful; the defeated to give grandeur to the victors. Or as Bertolt Brecht (Reference Brecht, Manheim and Willett1979) versed it in the final strophes of his Threepenny Opera:

The subject of painting changed, however, at the end of the nineteenth century with painters like Vincent van Gogh. While working on his now famous Potato Eaters in 1885, he also made sketches and paintings of peasants working in the fields. In his letters to his brother, Theo, he defended his choice at a time in which the historic or romantic-exotic genre was dominant. In every city, he wrote, there is an academy with “a preference for models of historical, Arabic, Louis XV, and in one word all, provided not real existing figures” (Hulsker Reference Hulsker1985, p. 308; my translation). But an academy where one teaches how to draw a digger, a sower, a woman hanging the pot over the fire, or a sewer did not exist, according to van Gogh (Hulsker Reference Hulsker1985, p. 308). Most exemplary for the unusualness of the choice of his subjects is the painting of old shoes he made a year later (see Figure 5). The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam provides the following explanatory notes about this painting: “An acquaintance of Van Gogh’s in Paris described how he bought old work shoes at a flea market. Then he walked through the mud in them until they were filthy. Only then did he feel they were interesting enough to paint.”Footnote 5

Figure 5. Shoes, painted by Vincent van Gogh, 1886.

Source: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

In history of science and history of economics, this attention to the ordinary is of a much more recent date. There is of course, since the 1980s, an increasing number of studies of non-White, non-male, non-Western scientists, but they are still selected for their success. It still keeps the unsuccessful and ordinary in the dark. Even though most historians of economics have abandoned “victorious” historiographies, “a history of winners and losers” (Weintraub Reference Weintraub2002, p. 259), the subjects that are mostly written about still align with the successful or the exotic.

The attention to the ordinary became possible only due to the use of a specific lens, namely the “lens of practice.” Thomas Stapleford (Reference Stapleford2017) discusses the consequences of such a lens. He defines practices as “collections of behavior that are teleological, subject to normative evaluation by broader groups, and exhibit regularities across people in a constrained portion of time and space” (p. 118). In other words, a practice of “doing economics” encompasses a collection of behaviors that exhibit regular patterns at any given time and place. It is subject to social norms and is teleological: the on-site researchers try to accomplish certain things, and what constitutes a valid accomplishment is subject to normative evaluation (p. 118). Thus, a practice is not defined by the success of a brilliant thinker, a genius, but is populated by various kinds of ordinary people doing different kinds of things with the aim of contributing to a shared target of accomplishment. It shifts, or, better, broadens, the attention from, for example, the writings of Wassily Leontief to the contributions of all the people involved with the Harvard Economics Research Project, or from the works of Wesley C. Mitchell to all those working at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Besides the fact that looking through the lens of practice makes ordinary people visible, it also makes history non-essential. One of the reasons that a history of practices might differ from a history of thought is that the lens of practice acknowledges that ideas do not travel in time: “texts cannot be treated as vessels for discrete ideas. Instead, every novel text must be interpreted in its new locale, and that interpretation relies on existing hermeneutical and theoretical practices” (Stapleford Reference Stapleford2017, p. 120). Ideas do not travel through ether; they are written down in letters, printed in publications, spoken out at meetings, discussed and interpreted at specific sites, with all the usual noise between sender and receiver. And also, ideas themselves are not always clear, not only to the receiver but maybe as well to the sender. Ideas are not global; they are local. But I want to go a step further: ideas are not universal either; there is no Platonic world of pure ideas that gradually, in the course of time, are picked up by great thinkers. I do not mean to say that there are no great ideas. Ideas are great when they are accepted by a community as providing a smart solution to a problem that is faced at a particular time and place.

But calling myself a “historian” does not position myself outside history, or enable me a view from never. My appreciation of some great ideas is as local and present as someone else’s appreciation of other ideas, whether of a historian or an economist. The metaphor of lenses reminds us that we often need them because of a common myopia, a tendency to magnify what is close and familiar, and to shrink what is further away, whether in time or place. It is like a View of the World from 9th Avenue, a drawing by Saul Steinberg that appeared as cover of The New Yorker on March 29, 1976.Footnote 6 It is a nice imagination of the parochial view by enlarging one’s close environment and by minimizing the rest of the world.

The consequence of a parochial view is that local ideas are taken as global, again both in time and place. This means that one expects that there must be “forerunners” and “followers” of great ideas, and so that these ideas have a longer history along which they have remained intact.

Does the locality of economic ideas mean that drawing larger lines through history does not make sense? That everything is relative? The answer is no, but the lines are of a different character than in terms of the “development” of ideas, in the sense of gradual enfolding, bringing out their potential. They are narrativizing lines, in the sense that they can, in Weintraub’s (Reference Weintraub2002, p. 272) words, “illuminate, entertain, teach, and thus lead to a change in our collective beliefs about our past.” The lines we draw through history depend very much on whom we wish to identify ourselves with, whom we wish to paint on the foreground in our portraitures of economics.

VI. IDENTITY

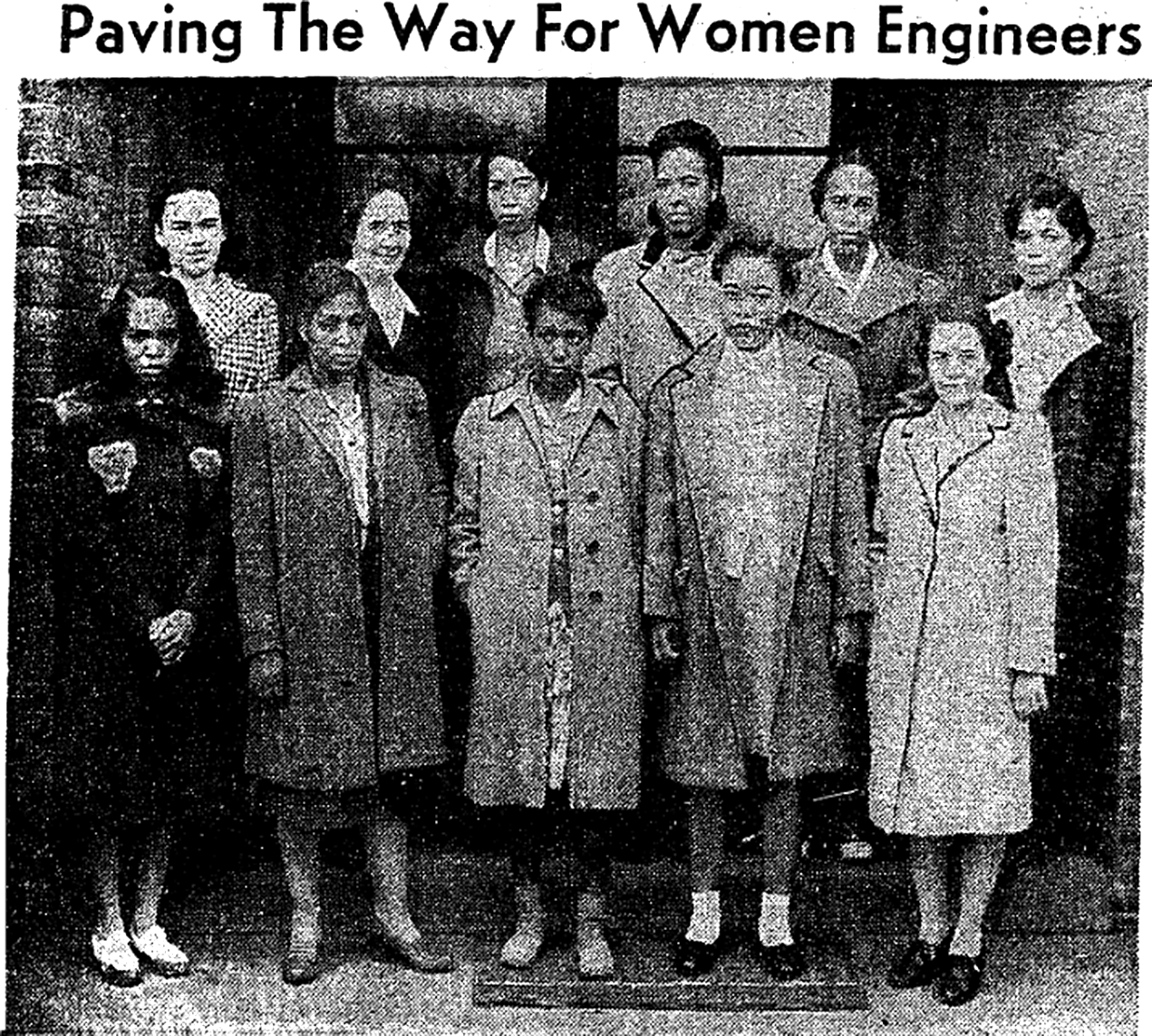

In her book Hidden Figures, Margot Lee Shetterly (Reference Shetterly2016) not only identifies the so-far-anonymous group of African American women who worked as mathematicians at NASA and were crucial in the development of its space program (see Figure 6), but she also changed our portraiture of US aeronautics, space research, and computer technology, and, by this, also modern American history. In her own words:

All too often their portrayals [of Black women]—our portrayals—in history are burdened with the negative imagery and vulnerability—that come from being both black and female. More disheartening is how frequently we look into the national mirror to see no reflection at all, no discernible fingerprint on what is considered history with a capital H. For me, and I believe for many others, the story of the West Computers is so electrifying because it provides evidence of something that we’ve believed to be true, that we want with our entire beings to be true, but that we don’t always know how to prove: that many numbers of black women have participated as protagonists in the epic of America. (Shetterly Reference Shetterly2016, pp. 247–248)

In discussing the possibilities of writing non-essentialist history, the options so far call for careful attention for the choices of viewpoint, horizon, grid, and scenery. Is this enough? The newspaper’s headline above the photo of the hidden figures in Figure 6 alerts us that it is not. Labels, titles, and heads are equally important in portraiture. In the newspaper, the women were identified as engineers; at NASA they were called “West Computers,” but Shetterly shows that their crucial role in the aerospace program was because of their contributions as mathematicians. To tell a history, one needs an appropriate vocabulary. When reading Forget’s account on how history is about identity, it is striking how much care she puts in describing how people call themselves in contrast to the more general labels that are given by others. If identity is related to labels, we need to consider vocabulary, too. And for a non-essentialist history, this vocabulary needs to be nominalist: labels are descriptors, and no names of essences.

Figure 6. The mathematicians of NASA’s west-side of Langley Research Center.

Source: New Journal and Guide, May 8, 1943; Norfolk Journal and Guide, p. A22.

I am not aware of any discipline in which labels do play such an important role to identify oneself and others. These labels, such as Classical, Neoclassical, New Classical, Keynesian, Post-Keynesian, New Keynesian, Old Institutional, New Institutional, Orthodox, Heterodox, to mention only some of the currently used identities, resemble more the labels art historians use to categorize various kinds of styles. But when these labels are used it is not clear what they represent. Historians of economics often would say that they represent specific “schools of thought.” But this only shifts the question to what a specific school represents. In my experience, a “school” usually refers to a small number of scholars who are claimed to share some ideas. These ideas could be about certain economic phenomena but also about how to study them.

Actually the usage of labels helps to avoid the problem of exactly describing what the shared thoughts are. It is easier to refer to some people and some of their works than describe what they exactly share. The reason is that any attempt to do so would give the embarrassing insight of doing severe injustice to the ideas of each individual scholar. Labeling implies reduction. So, why do we use these labels? We use them because labeling is supposed to give historical meaning. We wish to make ideas more global by putting them into a tradition. Clarifying in which tradition one stands is an important aspect of one’s identity.

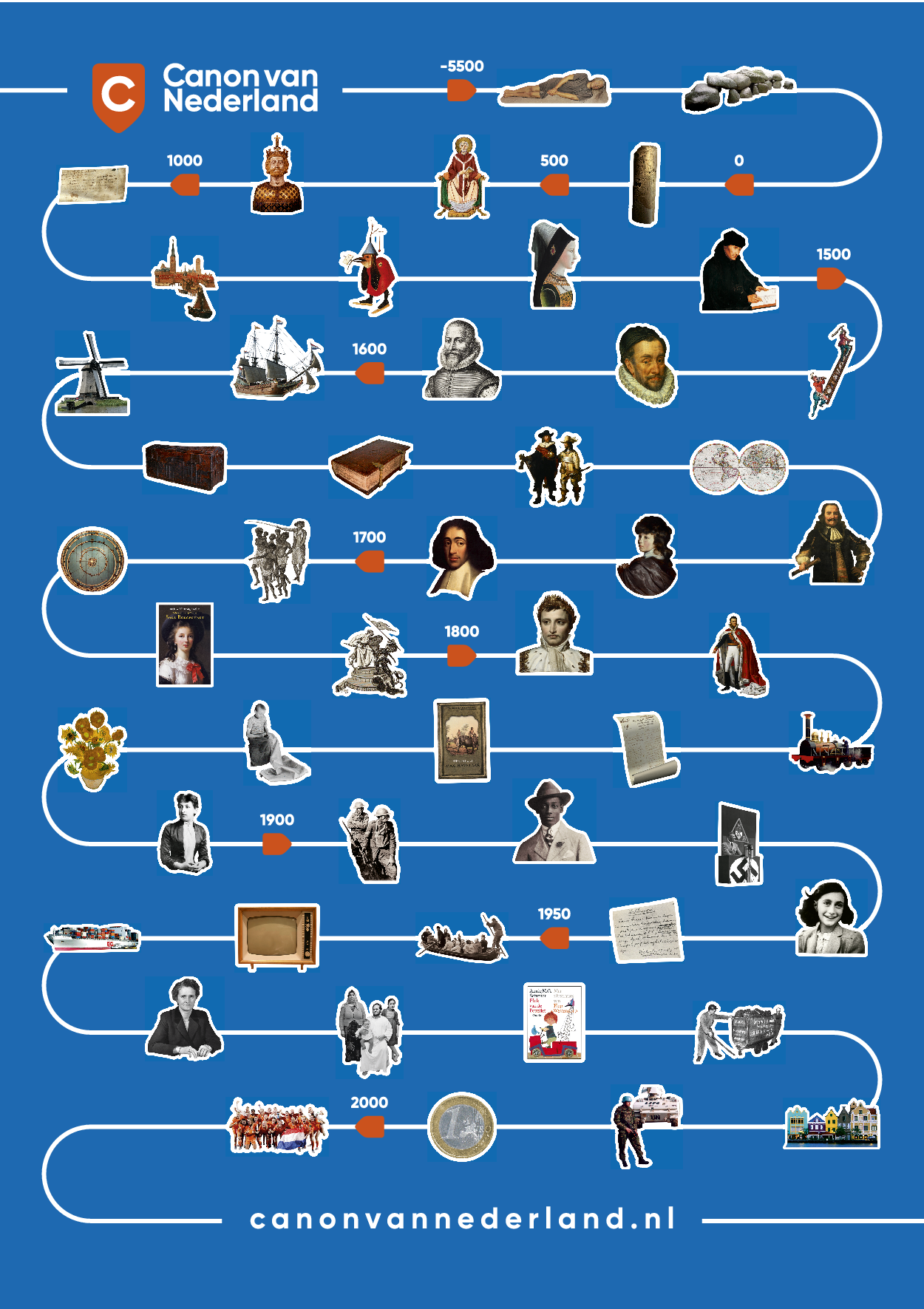

A nice example of how tradition confers identity is the construction of the Canon of the Netherlands, consisting of fifty windows that “serve as a basis for illustrating the epochs” (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2020, p. 15; my translation) and seven main lines representing “the common threads through the history of the Netherlands” (p. 21; my translation) (see Figure 7). The windows are represented by “icons,” such as paintings by Jeroen Bosch and Rembrandt, portraits of Erasmus and Spinoza, and a photo of Anne Frank.Footnote 7

Figure 7. Windows of the Canon of the Netherlands.

Source: www.canonvannederland.nl (accessed January 20, 2023).

The reason for developing a Canon of the Netherlands was a discussion in the 2000s about the Dutch identity. Therefore, a “Canon Committee” was established to help define Dutch identity (WRR 2007, p. 30). The idea was to strengthen national identity through the link of national history (WRR 2007, p. 42).

The “imagination” of a Dutch identity is by the Canon represented as a numbers of windows that are connected by a line. But a line is not a history. The timeline seems to offer a simple grid for relating Dutch icons: they are lined up along a single line, and so related according to their time. But such a line does not necessarily create a meaningful relationship. A chronological ordering along a line is not a narrative.

In his contribution to the New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics on the lemma “History of Economic Thought,” Craufurd Goodwin actually follows the same procedure as with the Dutch Canon: he first periodizes the timeline, and then gives windows for each period. Goodwin’s windows are not icons but more like group pictures. The periods are “The Enlightenment,” covering the second half of the seventeenth century; “Classical Political Economy,” covering most of the eighteenth century; “Neoclassical and Historical Economics,” the long nineteenth century, from 1870 until the First World War; “The Golden Age,” beginning around the First World War and ending in the 1950s and 1960s; and the period in which we live now, “Building a New Sub-discipline of HET.” For each period, history of economic thought is characterized by the ideas of a number of scholars and a selection of their works.

Besides that labels can be inclusive by giving you an identity, labels can also be used as instruments of exclusion. Goodwin (Reference Goodwin and Jones2018, p. 5898) ends his lemma with a prospect of the future of HET:

The original use for HET in the rhetoric of policy debates persists, but mainly on the surface. Libertarians wear Adam Smith ties and opponents of an active government in the economy dismiss their opponents collectively as Keynesians, but in both cases the combatants understand little beyond the labels. HET as doctrinal cleansing is still performed, but mainly in review articles and chapters, such as those in the Journal of Economic Literature and the various Handbook series, prepared not by specialists in HET but by high priests of the various sub-disciplines.

The worrisome aspect of this prospect is that Goodwin (p. 5887; italics are mine) also observes—he actually opens his contribution with it—that “the history of economic thought … is explored today for the most part within a sub-discipline of economics.” The doctrinal cleansing takes place not only outside HET but also within its borders.

The problem with any list is that it is restrictive and hence there are always people not on that list. History not only confers identity, it can also deprive one of identity. If history is about identity, we should pay more attention to the power that historians have not only to bring people into the historical window but also to place them outside it.

I found the placement outside the window best expressed by the American artist Gary Simmons with his untitled sculpture composed of typical blackboard materials: a smooth, dark surface; wooden frame and ledge; and a black chalk.Footnote 8 Most striking about this blackboard is that its height is very small, only 13.65 centimeters. The accompanying text of the Museum of Contemporary Art notes: “its impossible narrow proportions and black colored chalk limit the opportunity for written expression. As such, the artist reclaims a teaching aid—and platform on which history is conventionally taught—to address racial inequalities in America. And, the modified blackboard suggests a restricted, and obscured or unwritten, history.”

VII. WRAPPING UP

This brings me back to Putin’s attempts to destroy the Ukrainian identity, which he legitimizes by historical arguments. What kind of response is possible to keep or regain one’s own identity? I saw, in my view, a very adequate response by the Ukrainian people in an article in the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant on March 26, Reference de Weerd2022. The article on the history of Ukraine with the title “The Ukrainian Identity Gets Only Stronger,” written by the historian Fleur de Weerd, opens with a group photo of Ukrainian soldiers, which was broadly shared on social media among Ukrainians during the first weeks of the war (see Figure 8). The soldiers are posed in such a way that it recreates a painting from Ilja Repin, called Zaporozhian Cossacks Write a Letter to the Turkish Sultan (see Figure 9). The theme of this painting is a seventeenth-century episode in the history of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. They lived in a large area south of Kyiv on the banks of the Dnepr and were known for their strong sense of independence. The painting shows the answer of the Cossacks when the sultan demands their surrender. The story tells that the letter was a taunt, ending with the message that the sultan “canst kiss us thou knowest where.”Footnote 9 The reason that this photo was shared is that the Ukrainian identity is connected to this history of the Cossacks; the chorus of the Ukraine anthem refers to it. Unfortunately history can legitimize a war, but not stop it.

Figure 8. Group photo of Ukraianian soldiers.

Source: De Volkskrant, March 26, 2022.

Figure 9. Zaporozhian Cossacks Write a Letter to the Turkish Sultan, painting by Ilja Repin.

Source: Wikimedia Commons (accessed January 20, 2023).

We, historians of economics, contribute to the self-image of economics. This implies a responsibility to communicate the limitations of our histories and the potential misuse of our research, to paraphrase David Colander and co-authors in their (Reference Colander, Goldberg, Haas, Juselius, Kirman, Lux and Sloth2009) article on the responsibility of the economics profession after the financial crisis. We have to communicate that our portraits are not painted at a great distance but close to the subjects that we think need our attention. Our work, therefore, can never be an overview of the whole field, telling the whole story. And we should ask ourselves whether we have paid enough attention to what is really valuable.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The author declares no competing interests exist.