Ida Bell Wells stood center stage in the YMCA Hall in Bristol, southwest England, in April 1894 and explained her problem. Speaking at a public meeting chaired by a local vicar, she gave a lecture, like dozens she had given across Britain, in which she described the recent increase in lynchings inflicted on African Americans in the Southern United States. With the aid of photographs, Wells described in graphic detail the circumstances of individual murders and the flimsy justifications used by white lynch mobs.Footnote 1 As she explained to her audience that night, her efforts to alert the wider public to the rise of lynchings in the United States had been prevented in her own country as, “the newspapers, the telegraph wires, the cables, every avenue of communication with the outside world belonged to the white man.”Footnote 2 Her current mission was to, with the help of a sympathetic British public, circumvent these barriers and generate enough public outrage, communicated though these same avenues of communication, to force “powerful agencies in the United States” to condemn lynching.Footnote 3 By informing the British public of the horrors she had encountered, Wells hoped to shame her own nation into action.

Although she had left the shores of the United States, Wells had not escaped America. In crossing the Atlantic, Wells entered a world of American circuses, baseball teams, revivalist preachers, temperance campaigners, and blackface minstrels all plying their trade in Britain. Wells’s discussion of the injustice faced by African Americans in the United States clashed with a range of entertainments that celebrated the unique vitality of American life. The most notable product within this emerging canon was Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Buffalo Bill (real name William Cody) made a fortune presenting the romance and danger of “authentic” life on the Western frontier to great success in Britain from 1887 onward. The Wild West enjoyed the full institutional force of American support. General William Tecumseh Sherman wrote to Cody from the United States during the show’s first season in Britain, noting that, via daily reports communicated by Atlantic cable, “our papers have kept us well ‘posted’” of his transatlantic success, taking pride in the show’s narrative of western settlement and the conquest of indigenous populations.Footnote 4 Here was a story the nation could take pride in, and, unlike stories of rising violence against African Americans, it was duly communicated to the American public by the column load. Wells intended to disrupt the prevailing image of the United States proliferating through these entertainments, but she did so from a disadvantaged position.

In some ways, the appearance of figures such as Ida B. Wells in Britain amid this broader American presence resembled what theorist bell hooks referred to as an “oppositional gaze,” whereby Black women unsettled the message of white, male-controlled media simply by observing it from a critical distance.Footnote 5 Beyond this, however, Wells and others like her struggled to be heard among a broader marketplace of American figures vying for the attention and, in some instances, action of a majority white British audience. Such infrastructural imbalances served as a transatlantic extension of American racial hierarchy. Wells, however, was keen to emphasize the differences between the land of her birth and the country in which she now worked. Even in simply traveling by train between speaking engagements, she noted that she enjoyed a sense of liberty in Britain unavailable to her in “many of the States of my own free America.”Footnote 6

By focusing on the invocations of national ideals and history in the work of Americans in Britain, this essay explores the role of what I call “transatlantic performance” in advancing alternating conceptions of American nationality and national identity in the decades prior to the First World War. By traveling to and working in Britain at a time when American mass culture was taking shape, African American performers developed an argument that centered on their own oppositional American identity. These actors powerfully condemned contemporary American racism while still positioning themselves as the embodiment of an authentic national spirit. Nevertheless, the impact of this argument was constricted by three connected factors: the lack of resources available to African American performers, a subsequent overreliance on British support, and the narrow focus on the nation-state (especially the United States, in explicit contrast to Britain) as the key site of racial injustice. Rather than fully upturning American racism, the articulation of this oppositional identity highlighted issues that would only be identified and addressed in the wake of the First World War.

The first section of this article argues that conceptualizing transatlantic performance as a field enables historians to better assess the connected inequalities of capital and race that shaped the dominant American culture and its relationship with Britain. It then uses this framework to explore oppositional formations of American nationality in Britain. While historians have recently turned their attention to the rapid acceleration of international exchange and communication in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, they have heretofore underestimated the importance of these exchanges in consolidating the importance of “national” thinking. Nationality, as the preeminent collective subjectivity of modernity, was firmly embedded in international exchange, exhibition, and comparison. Recognizing both the shared features and points of divergence in these articulations allows for a fuller understanding of the role of transnational interaction in the production of national culture.

Transatlantic Performance: A Field Structured in Dominance

Transatlantic performers constituted a distinct category of transnational Americans. They neither represented the United States in an official capacity, nor did they comprise part of the so-called American colonies of permanent and semipermanent emigrants that emerged in most major European cities during the nineteenth century.Footnote 7 American performers often interacted with these overseas American communities, but they were by nature far more transitory. They moved between the United States and Britain, often on multiple occasions, using the perspective granted by transnational mobility to offer judgment and experience from both sides of the Atlantic. In this sense, they had more in common with the waves of wealthy tourists who crossed the Atlantic in increasing numbers in the period, bolstering the “American colonies,” forging their own version of the aristocratic “Grand Tour,” and producing their own assessments of national culture at the birth of the twentieth century.Footnote 8 This was the period in which American money, in the form of both individual consumers and large-scale corporate activity, first made its presence truly felt in the Old World.Footnote 9 This was also the period in which the journalists W.T. Stead and Frederick A. McKenzie first identified a trend that came to be known as “Americanization,” but it was a trend that many British hosts gladly accepted.Footnote 10 By 1902, shopkeepers on London’s Regent Street would hoist Stars and Stripes above their door each April in preparation for the “invasion season” of wealthy American tourists.Footnote 11 In many ways, traveling performers were part of this swelling transatlantic current.

But while tourists flitted between destinations at their own desire, interacting with each other and those in their host country as they saw fit, these touring Americans traveled across the Atlantic and then around Britain for a particular purpose. Each traveled with the explicit objective of exhibiting their work in public before an intentionally gathered audience for financial, social, or political incentive. Transatlantic touring was work. Unlike the circulation of commodities and consumer goods tied to Americanization narratives, performers talked back.Footnote 12 They interacted with, challenged the expectations of, and learned from their experiences in Britain. The corporeal presence of these Americans in Britain served as testament to some broader social reality in the United States. In explicit and implicit ways, they performed their identity on stage, and served as an embodiment of their nation abroad.

Bringing together a diverse range of traveling public figures, activists, and entertainers under the rubric of “transatlantic performance” creates an artificial but useful category of historical activity. This broad approach challenges conventional narratives regarding the international expansion of American “mass culture” prior to the First World War. It enables historians to better understand the mutually constitutive nature of culture, technology and politics. The increasing ease of transatlantic travel and communication in the second half of the nineteenth century made British touring an attractive prospect for many Americans; performers could reach new audiences abroad while maintaining, and usually bolstering, their reputation back in the United States.

This was the case for a variety of performers with vastly different agendas. Britain was a key market for American entertainment magnates such as P.T. Barnum, who gained international fame exhibiting the six-year-old “General Tom Thumb” in the court of Queen Victoria in the 1840s and over four decades later staged his traveling circus in London during the 1889 season.Footnote 13 Most famous was the exhibition of Buffalo Bill’s “Wild West” show in London in 1887. British audiences were fascinated by the show’s narrative of national self-making through racialized conflict on the western frontier.Footnote 14 The Wild West was presented simultaneously as a site of popular entertainment and an authentic insight into a quickly fading chapter of American history. The vocal approval of British royalty and aristocracy helped to confirm it as (according to its own promotional literature) “America’s National Entertainment” and the United States’ most popular cultural export in the decades prior to the First World War.Footnote 15

Britain was also a prime target for the sporting entrepreneur Albert Spalding, who attempted to export baseball overseas through two transatlantic expeditions and opened a branch of his sporting goods store in the capital in 1896.Footnote 16 American vaudeville performers toured the British music halls in growing numbers, a possibility that was facilitated by the systematization of the halls’ management structure and content through the growth of a syndicate system.Footnote 17 A growing number of Americans also used the British stage to advance social missions they had initiated at home. The religious revivals of Dwight Lyman Moody and the social purity campaigns of temperance leader Frances Willard were enacted through public addresses at mass gatherings, and both figures wielded new technologies of promotion and communication to advance a connected project between Britain and the United States.Footnote 18 None of these actors professed to represent American society in its exhaustive totality, but they gelled together in a way that represented the dynamism of modern American culture abroad. They cohered to form the dominant culture of America in Britain, a perpetually expanding grouping that reproduced what cultural theorist Raymond Williams describes as a “reciprocally confirming” system of meanings and values.Footnote 19

This was not, however, a free-flowing marketplace of ideas, of alternating representations of American identity absent of political or historical baggage. The same patterns of capital that organized American society and formed the American “colony” also narrowed the range of American performers that crossed the Atlantic, excluding some and including others. The American presence in Britain was structured, most obviously by the ability to cross the Atlantic. The advent of steamship travel, which made the prospect of an Atlantic voyage both amenable and affordable to a growing portion of middle-class Americans, was either the key facilitator or barrier to innumerable prospective performers, many of whom fell outside this social and economic group.Footnote 20

The field of transatlantic performance was structured most profoundly by broader societal formations and inequalities. In the late nineteenth-century United States, the predominant organizing force in society was race. It was no coincidence that those who represented America’s dominant culture abroad, whether they foregrounded it in their work like Buffalo Bill or left it unspoken, were white. Race worked as a structural and ideological mechanism that divided the population and naturalized the prescribed social roles of American citizens under capitalism. In the decades following the Civil War, social and economic relations in the Southern United States in particular were reconfigured and redirected through a regime of racial segregation that could be molded around a rapidly urbanizing nation.Footnote 21 From segregated employment and public facilities, through the restriction of social mobility and barriers to economic opportunities, to the looming threat of interpersonal and mob violence, America’s modern social order was produced and reified through a regime of racial domination that replaced the older system of enslavement.Footnote 22 Stuart Hall refers to such a segregated society as a totality “structured in dominance,” wherein racial divisions operate as a productive force within specific historical conditions, operating through “economic, political and ideological practices” and serving to fix and ascribe social groups within a hierarchy in “a form favourable to the long-term development of the economic productive base.”Footnote 23 Economic gain may not have been the motivation for every instance of racist persecution, but it provided the underlying logic for the adaptation in social relations in the decades following emancipation.

The system of racial domination in the Southern United States that came to be known as “Jim Crow” permeated economic, social, and cultural life. While this system developed over time and was variegated by region, it emerged through a national consensus that the subjugated position of Black people and other people marginalized on the grounds of race would secure the dominance of whites.Footnote 24 Though not impenetrable, this system functioned like the tentacles of an octopus, reaching across the nation and into the public and private lives of its citizens. The culture that was produced under this system tended to reflect or react against these conditions.

These tentacles also stretched across the Atlantic. American circuits of racial power were extended through both unilateral assertions and occasional points of convergence between Britain and the United States’ regimes of racial hierarchy. The Wild West’s second visit to Britain in 1891 was bolstered by the addition of twenty-three Lakota “hostages” who had been detained as military prisoners at Fort Sheridan since the violent suppression of the Ghost Dance movement the previous year.Footnote 25 Their participation was sanctioned by Lewis A. Grant, the acting Secretary of War, whose letter of authorization was quoted liberally in the show’s promotional literature as evidence of the Wild West’s authenticity in Britain and its alignment with the punitive policies of the American government.Footnote 26

Many African and Native Americans nevertheless crossed the Atlantic of their own accord, despite (and often because of) a worsening situation at home. Black American travelers, while always a minority, were increasingly common in Britain in the decades following emancipation. These travelers still encountered various barriers to mobility and exhibition. When the musical group the Fisk Jubilee Singers first toured Britain under the auspices of the American Missionary Association (AMA) in 1873, the group was initially denied passage by multiple steamship company agents in New York, citing fears that “passengers would not like to have negroes to accompany them in the cabins.” The group traveled to Boston to find more hospitable traveling conditions.Footnote 27 In 1913, the boxer Jack Johnson, who had appeared on British music hall stages on several occasions as he trained for official bouts, was the subject of a boycott by the Variety Artistes Federation, the trade union of music hall performers. Johnson had recently fled the United States having been convicted of violating the 1910 Mann Act, a which prohibited the transportation of women across state lines for “prostitution, debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose” and whose heavily racialized origin led to it being nicknamed “the White Slavery Act.” The union argued that Johnson’s status as a fugitive from the American legal system meant that allowing his musical comedy routine to go ahead would signify a “clear degradation of the music halls.”Footnote 28 Johnson’s contract with the syndicate Variety Theatres Consolidated was eventually terminated by mutual consent.Footnote 29 Union members and public commentators insisted that the boycott was a matter of “public decency” rather than racial discrimination, but they took their cues from a judicial system that had criminalized Johnson’s behavior in the United States on the grounds of his race.Footnote 30

Britain produced its own cultures of anti-Blackness. Blackface minstrelsy, though originating in 1840s New York, was enormously popular overseas. By the late nineteenth century minstrelsy in Britain had assumed a distinctive imperial character, incorporating scenes from imagined “darkest Africa” as well as the antebellum plantation.Footnote 31 The stereotypes and racist caricatures of the minstrel show were an obstacle to the success of almost every African American public figure in Britain, including the waves of “genuine” Black minstrels that gained popularity toward the end of the century.Footnote 32

Outright racial prohibitions were also occasionally enacted. Two years before the music hall union boycott, a licensed fight involving Jack Johnson scheduled to take place in London was prohibited by the Home Office following complaints that the match might lead to racial disturbances in the British Caribbean. These concerns were fueled by the race “riots” that had exploded across the United States following Johnson’s victory over the white boxer Jim Jeffries in Nevada the previous year. However, this panic was rooted in the fragility of minority white rule in parts of the Empire rather than a fear of the threat of mass racial violence in Britain.Footnote 33 Race was articulated differently in colony and metropole, even as the two were drawn together through the deepening economic ties and the domestic jingoism of the “New Imperialism” of the late nineteenth century.Footnote 34 Although Britain controlled the world’s largest empire at the turn of the twentieth century, the interpersonal violence inherent in the maintenance of colonial power was (until the seaport riots of 1919) mostly contained to its territories.Footnote 35 The small number of Black people resident in the metropole enjoyed comparatively positive relations. Despite occasional points of ideological and practical confluence, racial hierarchy operated very differently in Victorian and Edwardian Britain than the post-Reconstruction United States. This meant that, with notable exceptions, African Americans were usually freer to work and express their opinion on the British stage than they would be at “home.”

The extension of American racial domination into the mechanics of transatlantic performance more frequently and more subtly manifested in differences in access and resources. All transatlantic performers interacted with the same structures and engaged in similar efforts in the course of their work. All advertised their public appearances, all sought the approval of British audiences, and all chose to communicate their reception back to the United States, but they did so from fundamentally different vantage points. As the historian Janet Davis has demonstrated, public intrigue in the “spectacular labor” involved in promoting, organizing and staging the large-scale entertainments of the Gilded Age helped to clarify the uniquely American character of this emerging mass culture.Footnote 36 Half a million dollars was invested in the opening London performance of Barnum’s circus in 1889. Over two hundred tons of material was shipped from Buffalo, New York, for preliminary advertising alone.Footnote 37 The crew behind the Wild West’s later British tours included a team of forty-five advance agents, including a three-man Press Bureau charged with furnishing city walls and local newspapers with information on its upcoming appearances.Footnote 38 African American performers advertised their work of course; the Jubilee Singers’ flyposting and newspaper advertising campaigns were remarkably comprehensive, to the extent that their apparent early embrace of commercialism drew criticism from some of their more conservative religious patrons.Footnote 39 But no non-white managed American entertainment could match the scale and enterprise of these larger shows, and as such struggled to challenge their claims to represent the nation abroad.

The transmission of performers’ reception in Britain back to the United States was also structured by material disparities. The increased use of the transatlantic telegraph in the late nineteenth century and the growth of a cartel of press agencies led by the Associated Press, which enabled subscribing members to receive reports from overseas via transatlantic cable, connected the British and American public spheres in new ways.Footnote 40 Performers made extensive and creative use of these technologies. The World’s Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), under the leadership of Frances Willard, strongly encouraged its members to employ stenographers to assist the local and national press in reporting its meetings.Footnote 41 In June 1895, a one-thousand-word transcription of Willard’s address at the organizations convention at the Queen’s Hall in London, calling for a worldwide union of “English-speaking women” to “clasp hands in the unity of spirit and the bond of peace,” was cabled in time to be published that same evening by papers in Boston, New Haven, and Fort Wayne.Footnote 42 When two professional baseball teams visited Britain in 1889 under Spalding’s direction, a designated correspondent for New York Herald’s European bureau cabled daily box scores and reports of the group’s exploits to the paper’s American offices via the Atlantic cable that the Herald’s publisher had financed five years earlier.Footnote 43

Dictated by the purview of owners and correspondents as well as the presumed interests of advertisers and readers, the provisions of this technology were predictably limited. The Associated Press denied membership to African American papers, although most of these publications were so financially precarious that they would have struggled to pay the subscription cost regardless of formal exclusion.Footnote 44 Black performers found their own way to advertise their success back home, writing letters and posting clippings of British reports praising their work to sympathetic newspapers in the United States, which were further disseminated through informal circuits of republication and citation.Footnote 45 For her second tour of Britain, Ida B. Wells was paid by the Chicago Inter-Ocean, a white-owned newspaper, to write and send by mail a series of dispatches on her experiences overseas.Footnote 46 These improvisational practices enabled the work of innumerable Americans to reach domestic audiences prior to their return to the United States, but were by nature more fractured in their transmission and circulation. In contrast, the effective dominance of the visions of American life as communicated through these emergent infrastructures and technologies was, thanks to their increasing reach, all but preordained. The emergence of this apparatus represented a shift from earlier waves of transatlantic performance. This imbalance, and its connection to the deeper structuring force of race, was one that travelers like Ida B. Wells were all too keenly aware of.

Britain itself occupied an ambiguous position in the affirmation of a dominant American national culture. Whereas activists like Willard championed a unique racial bond between the elites of the two nations (a fin-de-siecle cause célèbre for many intellectuals and reformers on both sides of the Atlantic) as an impetus for increasingly closer relations, for many more travelers Britain was little more than a stepping stone to greater triumphs in Europe and beyond.Footnote 47 Likewise, transatlantic success was a boon for many American performers but not everyone. For proponents of baseball, failure and derision in Britain during the late nineteenth century eventually served as a foil to better emphasize the distinct American character of the “national pastime.”Footnote 48 And as new markets on the American continent and across the Pacific were eased or pried open in the first decades of the twentieth century, artistes and activists diversified their touring itineraries. Though Britain continued to hold a prominent place in the international circuitry of American culture, never again would Americans imbue the success of a dominant transatlantic performance with as much significance as the Wild West’s conquest of Britain in the late 1880s.

Oppositional National Identity

Britain retained a more consistent place in the affirmation of an oppositional American identity. Just as the mainstream culture of the United States was reconciled through a shared commitment to whiteness, racial inequality was the fracture along which the most vibrant opposition to this normative order erupted. The travel and testimony of Black travelers in Britain could offer a profound challenge to the virtuous dynamism of the United States as depicted through its dominant culture. However, the mere social reality of being Black did not determine a position of oppositionality. Many “genuine” Black minstrel performers challenged the racist assumptions of white audiences and management but were also frequently presented alongside their blackface counterparts with little commotion or comment.Footnote 49 Non-white activists who worked with reform organizations such as the WCTU pressured the organization to modify its work in colony and metropole but were seldom afforded the space to challenge the racial order of United States or Britain.Footnote 50

Nor did being an African American in Britain inevitably afford a space of active opposition. Raymond Williams refers to oppositional culture as the practices of a person or group who “wants to change the society in its light,” distinct from the formation of an alternative culture of “someone who simply finds a different way to live and wishes to be left alone with it.”Footnote 51 These practices are by their very nature unassimilable into the dominant order. In contrast, many cultural products that had been developed by African Americans, such as ragtime music and the “cakewalk” dance, were adapted, adopted, and incorporated within the dominant culture through transatlantic exhibition. Historians and performance scholars have demonstrated the subversive potential of various “alternative” cultural practices that found a space, however precarious, on the fringes of mainstream society, but these were rarely afforded the resources and audience to mount a pronounced and overt opposition to American racial hierarchy.Footnote 52 Structured by the mediation of promotional agents and patrons, the existence of non-white Americans within the field of transatlantic performance did not upset the dominant postulations of American identity in Britain.

But it was no coincidence that the most significant challenges to the dominant consensus came from African Americans. The very fact of Black mobility was a strike against the prevailing racial order of the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, and many Black travelers utilized transatlantic travel as an opportunity to defamiliarize and repudiate these structures. This strategy drew on a half-century long tradition of political protest and activism pioneered by the anti-slavery movement. With the assistance of sympathetic patrons, most notably a community of nonconformist Christian reformists centered in industrial Northern England, African Americans traveled across the Atlantic to spread the cause of abolition throughout Britain and Ireland in the decades prior to the Civil War. Frederick Douglass’s two-year visit beginning in 1845 remains the most famous and best-documented of these sojourns.Footnote 53 However, the historic fixation on Douglass’s well-crafted orations and carefully managed public persona has tended to unintentionally separate the transatlantic abolitionist movement from its broader cultural context. Dozens of activists crossed the ocean and willingly adopted the vernacular of mid-Victorian performance culture. Among these were Henry “Box” Brown, who frequently reenacted his dramatic escape from enslavement via a packing box on stage, and William and Ellen Craft, whose repeated visits to the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace in 1851 effectively disrupted the message of national progress projected through the United States’ official “section” of the exhibition.Footnote 54 This diversity of tactics demonstrates a recognition on the part of abolitionists that they were competing for the attention and affections of a leisure-going British public.Footnote 55 These campaigners produced their own touring infrastructure and forged connections that would guide the work of later transatlantic performers. They did so out of a belief that the erection of a “moral cordon” of British condemnation would hasten the end of slavery in the United States.Footnote 56

Much in the vein of this tradition, Ida B. Wells used her position abroad to rally against both the increased lynching of Black people by Southern whites and the complicity of elite Northerners who refused to fully condemn these crimes. On stage and in newspaper correspondence, she spoke of a concerted “American prejudice” that had both energized racist violence and closed the “doors of the churches, reading-rooms, concert and lecture halls” to dissenting voices.Footnote 57 In the columns she wrote for the Chicago Inter-Ocean, Wells recalled the shock of audiences at the grotesque details of the crimes she reported and the repression she had faced in the United States. She noted with some irony that she was only able to gain such a hearing, “in monarchical England—that it would be impossible in democratic America.”Footnote 58

Wells argued that elite Americans (especially Northerners) held the opinions of the British above all other nations, and appealed to British audiences to use their transatlantic connections to apply whatever pressure at their disposal to the United States.Footnote 59 In interviews with English periodicals and newspapers, Wells focused on the complicity of much of the American transatlantic community, including Frances Willard and Dwight Moody, who had ignored or even condoned these murders in order to smooth over the cracks in national reconciliation at home.Footnote 60 Her pamphlet Southern Horrors, which detailed in graphic detail the violence inflicted upon Black victims of white lynch mobs, was republished for British audiences as United States Atrocities, incriminating nation as well as region in these crimes.Footnote 61 But Wells did not disavow her country of birth entirely, couching her appeal in the fact that African Americans had been “loyal” to the Republic, combating claims that taking her campaign overseas marked her as “unpatriotic,” and insisting that she be referred to “Afro-American” in the British press as “Negro leaves out the element of nationality.”Footnote 62 More than providing temporary respite from the sharpest edges of white supremacy, her brief time abroad helped Wells argue more forcefully that Black people deserved the rights and privileges of American citizenship.

Opposition was also expressed by the musical impresario and vocalist Frederick Loudin, who first traveled to Britain as a member of the Fisk Jubilee Singers on their second British tour in 1875. The group had proved a success within the highest echelon of British society on its first tours, performing privately for Queen Victoria and taking breakfast with William Gladstone and his family.Footnote 63 Following the Singers’ disaffiliation from Fisk University and subsequent dissolution in 1878, Loudin “reorganized” the group, utilizing their identity and transatlantic connections, and overseeing almost continuous international touring until the turn of the century.Footnote 64 Loudin and his wife Harriet oversaw the Singers’ transformation in the popular imagination as they transitioned from serving as a proud testament to the cultural progress made through Reconstruction to a rarely mentioned and unfashionable artifact of a now-bygone era. The couple adapted to these changing circumstances by exploring new international markets (largely following the contours of the British Empire in Asia and Oceania), by integrating new compositions into the group’s repertoire and, most importantly, by asserting the group’s political relevance around the world in an age of intensifying hostility against African Americans at home.

Frederick Loudin wrote to Black newspapers and regularly spoke on American stages about the hospitality received by the group on their transatlantic travels, contrasted with the “prejudice which confronts a Negro at every turn in life” in the United States.Footnote 65 Promotional literature listed the foreign dignitaries and heads of state they had sung for and met with. Overseas, he gave speeches in intervals of concerts, explaining the origins of the group and its music in the wake of plantation slavery, the advances of the Reconstruction, and the recent deterioration in American race relations. The couple was committed to political activism, using the spoils of international success to challenge racial oppression at home and abroad. In 1893, Loudin proposed, solicited support for, and contributed $50 to the production of a pamphlet, edited by Ida B. Wells and Frederick Douglass, protesting the exclusion of African Americans from the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago.Footnote 66 An essay included in the pamphlet on “The Progress of the Afro-American since Emancipation” cited the Jubilee Singers as responsible for making “the music of the American Negro known throughout the world.”Footnote 67 Loudin served on the executive committee of the first Pan-African Congress in London in 1900, which brought together campaigners from Africa, the Caribbean, and the United States, and was most famous for W.E.B. Du Bois’s speech in which he first identified the “Color Line” as the “problem of the twentieth century.”Footnote 68 As participants in an emerging Black political community, Frederick and Harriet Loudin weaponized their international success to challenge an increasingly racialized dominant American culture.Footnote 69

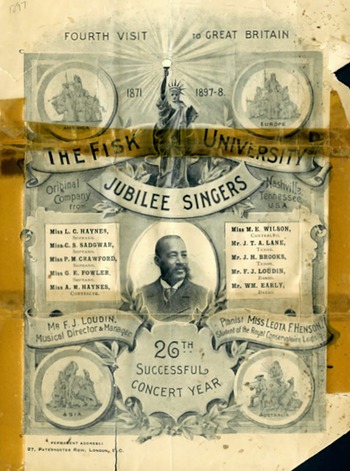

The Loudins’ attempt to situate the Jubilee Singers and their music within an emerging American cultural pantheon was one of their most effective tactics. Although alienated and treated poorly at home, overseas the group often sung in front of flags bearing the Stars and Stripes.Footnote 70 Whereas the original group’s austere promotional material stressed the group’s place within the history of enslavement and emancipation of Black people in the United States primarily in order to distinguish their work from blackface minstrel acts, by the late nineteenth century the group willingly embraced a more conventional national symbolism.Footnote 71 Promotional pamphlets for their final tours of Britain matched sketches of Loudin and the group’s name with a likeness of the Statue of Liberty, her rays shining outward (see fig. 1).Footnote 72 Representations of the territories the group had visited through international touring were marshaled under an icon of American freedom.Footnote 73 The position of the group and its members within society at large infused the use of this symbolism with a drastically different political valence than the promotional material of Barnum or Buffalo Bill, but it utilized the same visual language. This imagery situated the group as representatives of America in Britain at a time when Black contributions to national life in the United States were being denied or ignored.Footnote 74 [Figure 1]

Fig. 1. Commemorative program from the ‘Fisk University Jubilee Singers Fourth Visit to Great Britain’, 1897-1898. Fisk University, John Hope and Aurelia E. Franklin Library, Special Collections, Jubilee Singers Archives, Box 12, Folder 5.

The Jubilee Singers’ claim to national relevance was corroborated first through the praise lavished on the group by foreign journalists, and eventually in the tributes of American observers, to the national distinctiveness of the group’s music. European critics and some American allies in the 1870s had commented on the distinctiveness of the spiritual as “an original style of music peculiar to America.”Footnote 75 After a decline in interest following the original group’s disbandment, this discourse enjoyed a seemingly unlikely resurgence in the 1890s. The Czech composer Antonin Dvořák wrote in 1893 of his belief that “the future of this country must be founded upon what are called the Negro melodies.” W.E.B. Du Bois most famously credited the group in 1903’s Souls of Black Folk with having “sang the slave songs so deeply into the world’s heart that it can never wholly forget them again.” Du Bois argued that the spirituals (which he termed the “sorrow songs”) themselves represented “the sole American music’ that had been “given to the world.” While the songs had been “neglected … half despised … persistently mistaken and misunderstood” by domestic audiences, they occupied a status as “the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people.”Footnote 76 In this conceptualization, the fact that the spiritual had gone unappreciated did not preclude it from playing a role in the cultural production of the nation. The continuing transatlantic circulation of the group’s members and their music, and the Loudins’ entanglement in a nascent Black internationalism, imbued the Spiritual with a defiant, oppositional status in the United States at a time of increasing repression for African Americans.

But while this mobility has prompted the cultural studies scholar Paul Gilroy to situate the Jubilee Singers’ music as a formative component in the development of a “Black Atlantic” that transcended “both the structures of the nation-state and the constraints of ethnicity and national particularity,” their most forceful and immediate political appeal emerged through an assertion of contemporary national relevance.Footnote 77 Loudin’s scrutiny of the apparently exceptional features of American racism, along with the group’s inversion of national symbols, located their political work in direct opposition to the dominant American order. Rather than transcend the nation, Ida B. Wells and the Fisk Jubilee Singers’ transatlantic work served to implant this sense of a uniquely American character more firmly in global and domestic imaginations.

This was partly down to the practical nature of transatlantic performance. When the anarchist campaigner Lucy Parsons visited Britain in 1889 to commemorate the execution of her husband in the wake of the Haymarket affair two years earlier, she quickly recognized the expectations placed upon her as a visitor from the United States. At home, Parsons called for the violent overthrow of the local ruling class as part of an international worker’s struggle, but overseas she framed this effort as the recovery of a lost national spirit. Whereas stateside speeches often focused on the need for further direct action against the state, most of Parsons’s speeches in Britain focused instead on the history of the labor movement in the United States and her husband’s plight.Footnote 78 She declared herself a follower of “one of the promoters of the Declaration of Independence—Thomas Paine.” Though “liberty on American soil” was now imperiled, through her status as “one whose ancestors are indigenous to the soil of America” (Parsons was mixed race, and claimed Muscogee Creek ancestry), she argued that she represented “the genuine American,” reclaiming a lost tradition of rebellion.Footnote 79

While Lucy Parsons’s own anarchist politics specifically challenged the authority of national borders and their attendant political structures, her position as an American radical in London prompted her to expound on the distinct features of her ideology and upbringing, to present herself as “the genuine American.” Ida B. Wells had been brought to Britain at the invitation of and with the financial support of the editorial staff of an anti-racist periodical, Anti-Caste. The periodical was as formed part of an explicitly internationalist project, one that sought to be “as truly English as it was American as truly Indian as English.”Footnote 80 Wells, as the visiting American representative of this cause in Britain, was therefore encouraged to consider the specific American characteristics of lynch law and Southern racism so that it may be better comprehended by her newfound comrades. The defamiliarizing experience of transatlantic travel and the expectations of British audiences pushed these travelers to act as the “embodiment” of their cause in Britain, and to ruminate on the distinctive national character of their own work.Footnote 81

However, this tendency toward national thinking also formed a more conscious ideological effort to invert the dominant expressions of American identity in Britain. This was evident in the frequent invocations of nominally distinct American ideals and values by activists and entertainers; Parsons’s use of Thomas Paine’s words; Loudin’s appropriation of the Statue of Liberty to herald the achievements of a Black vocal group; Wells’s repeated assertion that African Americans had been “loyal” to the country of their birth, along with her ironic summoning of “free” and “democratic” America in comparing her treatment in Britain to the United States. These were attempts to affirm the value of their work as a reclamation of a forgotten or betrayed national tradition, which became more notable through their position as American representatives in a foreign land. Britain became a key site of struggle over the meaning of the nation.

These attempts were produced under certain conditions, both economic and ideological. Most notably, the work of these oppositional Americans was produced and responded to in a context where a dominant vision of the United States as a virtuous, powerful, and virile young nation was being communicated to the rest of the world, especially to the United Kingdom. To return to Stuart Hall—

racist interpellations can become themselves the sites and stake in the ideological struggle, occupied and redefined to become the elementary forms of an oppositional formation—as where “white racism” is vigorously contested through the symbolic inversions of “black power.” The ideologies of racism remain contradictory structures, which can function both as the vehicles for the imposition of dominant ideologies, and as the elementary forms for the cultures of resistance.Footnote 82

The nation proved the most powerful of these “contradictory structures” at the turn of the twentieth century, reifying the racist actions of white Americans as serving a wider interest while also functioning as the primary repository of social meaning for African Americans seeking to affirm their belonging within a political community. Going abroad helped these actors situate their work within a wider project of national redemption. Transatlantic exhibition proved a particularly fruitful ground for the development of a culture of resistance that invoked many of the same forms and symbols as the dominant culture.

The Bind of the National

These forms and symbols, however, were anchored in broader structures. One consequence of the emergence of a milieu of transatlantic performance so resolutely opposed to the dominant forces of the United States was that it invited a reply from those forces. Ida B. Wells’s anti-lynching campaign provoked action from her newfound influential British allies, but this alliance attracted a new wave of criticism. Her popularity abroad was used as evidence by her domestic opponents that Wells was (according to the New York Times) “‘Showing up’ America,” or that she was (according to one of Frances Willard’s allies in the WCTU) a “traitor” to her country and “her people” for discussing this violence abroad.”Footnote 83 Opponents in the United States mobilized an older rhetorical tradition of Anglophobia to bolster their own nationalist credentials; William Meade Fishback, the Governor of Arkansas, writing in response to the visit of an “English Anti-Lynching League,” organized in the wake of Wells’s 1894 lecture tour, asserted that members of the committee had “neither national training, national habit, nor national character” to exercise any positive influence on the situation in the United States.Footnote 84

For apologists of lynching, this invocation of tyrannical English intrusion provided a formidable national opponent to their own defense of American “liberty.” Wells’s own declarations of national loyalty, meanwhile, were largely ignored in the United States. Although her positive reception in Britain resulted in greater coverage of lynching at home, the critiques of her work were more coordinated and sustained than previous attacks. Statements from American newspaper correspondents in Britain attacking her work were transmitted by Atlantic cable, reformulated domestically and circulated nationwide by news agencies, unifying North and South against the perceived arrogance of British oversight.Footnote 85 In August 1894, the Charlotte Observer republished an extract from the New York Examiner arguing that Wells’s transatlantic efforts demonstrated that she knew “very little about the American character” and rejected the intrusions of the British in the first person; “we do not like when foreigners take care of us.”Footnote 86 As historian Sarah Silkey has argued, while her American campaign faltered, the most enduring legacy of Wells’s transatlantic work was the effect it had on British perceptions of racial violence in the United States.Footnote 87 Wells had made lynching a national problem, but her work had also inspired a nationalist response.

Wells’s campaigns of 1893 and 1894 provoked a uniquely aggressive backlash in the United States, but this response contained the kernel of a broader inequity. As these oppositional Americans attempted to summon historic struggles and patriotic declarations of universal equality in appealing for a renewed commitment to the promises of the Republic, they had to contend with the political reality of a dominant culture that understood the current condition of American life as the fulfillment of these very same ideals. Representing oneself as authentically, genuinely American abroad was a powerful gesture, but at home these claims conflicted with a growing body of evidence that the United States rewarded a racially exclusive, culturally conformist national identity.Footnote 88 This was both the basis and the burden of an oppositional American identity.

Not all were willing to make a commitment to an oppositional national project. The Black writer Paul Laurence Dunbar, who also traveled to Britain in 1897 for a mostly unheralded tour reciting his poetry, dismissed the claims of Dvořák and other “foreign critics” regarding the spiritual’s American character out of hand in an article for the Chicago Record in 1899.Footnote 89 Having heard from his friend Frederick Loudin how the public had “flocked to hear his troupe sing their plantation melodies” and alternately witnessed such music performed badly at white American glee clubs, he contested the claim that the spiritual represented “the only original music that America has produced.”Footnote 90 Instead, “she [the United States] has only taken what Africa has given her.”Footnote 91 In Dunbar’s estimation, adoption by white America was not a welcome marker of success for a race that had been so thoroughly excluded from the national community. National ideologies and identities were limited by historical and political factors; attempts to reclaim them under the guise of racial equality struck some observers as a fool’s errand.Footnote 92

Frederick Loudin was increasingly convinced of this view. Though he continued to sing in front of American flags and sold pamphlets emblazoned with national icons, his time abroad accelerated a sense of profound alienation from his country of birth. In the 1870s he had described himself in writing as “an enthusiastic American” to buttress hopeful appeals for change from abroad, but by the turn of the century this hope had dissipated. In private correspondence he referred to the United States as the “land of the free and home of the brave lynchers.”Footnote 93 He spent extended periods overseas, returning only to his home in Ohio for the final two years of his life in 1902 after ill health prevented further touring. Even then he resented his return to “free America with its restrictions, limitations, repressions and prescriptions,” finding few comforts in the United States besides his “friends and the Negro race.”Footnote 94

As his hope for the United States waned, Loudin became increasingly enamored with Britain. This affection only intensified following his group’s two-year tour of the British Empire in the 1880s. His experience performing for audiences comprised predominantly of white settlers in “New Zealand, Tasmania, Ceylon, India, Burmah, Singapore and Hong Kong” further convinced him of the benefits of a life lived “beneath the folds of the Union Jack.”Footnote 95 Wells too, in highlighting the distinct “American” character of lynch law, wrote glowingly of her reception overseas. She likened her time abroad as being “born into another world, to be welcomed among persons of the highest order of intellectual and social culture as if one were one of themselves.”Footnote 96 The use of apparent British magnanimity to shine a harsher light on the United States’ failings was a strategy pioneered by earlier abolitionist campaigners.Footnote 97 Their elite British allies may have welcomed favorable comparisons with the United States for self-congratulatory or strategic geopolitical reasons, but African Americans had their own reasons for praising their own nation’s former adversary.Footnote 98

Why did African Americans express such fondness for the world’s largest empire at the height of the “New Imperialism”? To a certain extent, this affection can be explained by the heavily mediated nature of transatlantic performance; Americans that traveled to and were successful in Britain were often sheltered from the harshest realities of life for racialized subjects in the imperial core. Their success, as American representatives of elevated social standing, shielded them from many of the most racist practices of Britain and its Empire.Footnote 99 It was also a product of oppositional Americans’ necessary greater reliance on the logistical assistance and patronage of their British allies than their dominant counterparts. Whereas figures like Buffalo Bill could control almost every aspect of their transatlantic operations, the dearth of resources available to African American performers meant that their success was contingent on the consistent support and sympathy of promoters, power brokers, and other local figures of influence.

This insulation partly explains the enthusiasm of African American travelers toward Britain, but not entirely. Ida B. Wells toured Scotland in 1893 with Celestine Edwards, a Dominican activist who observed the pernicious influence that British imperialism had on race relations in the metropole, identifying a swelling racial animosity in the second half of the nineteenth century that manifested in renewed public interest in racist cultural forms including blackface minstrelsy and “savage exhibitions” as well as street harassment and hostility toward Black students and professionals.Footnote 100 Members of the original Jubilee Singers likewise documented the racist comments made by British onlookers.Footnote 101 In correspondence, Loudin also observed increased racial prejudice in Ireland on his final tours, but he ascribed this trend in particular to “the contact and intercourse with Americans who come over here and those who move from this country to America.”Footnote 102 Although Wells was involved with Anti-Caste during her time abroad, the publication and its contributors’ frequent linking of American racism and British imperialism were never communicated to her readers in the United States. Neither was the considerable backlash Wells received from British journalists and letter writers who refused to believe that lynchings took place on the scale she depicted, or who argued that they served as a necessary phase in reaffirmation of law and order in the wake of Reconstruction.Footnote 103 This selective recollection can be understood as a kind of “strategic Anglophilia” that embraced and even obscured British injustice to better characterize the exceptional nature of American racism.Footnote 104 Here was a transatlantic mobility that constricted even as it expanded. Criticism of the United States was made more forceful by travel and transatlantic success, but the work of these activists produced a rhetorical bind that precluded viewing Britain as guilty of similar wrongdoing.

Breaking the Bind

This recourse to national tendencies was a mystification of wider systems of power, but it also constituted a logical response to injustice in a world structured by national borders and institutions. Any critique of systemic inequality or appeal for reform required a reckoning with the fact that while these systems may have been produced globally, they were regulated and enforced through national units. Lucy Parsons, for one, largely avoided the romantic vision of Britain offered by some oppositional Americans, calling London “a stupid place” full of “misery” for the working classes.Footnote 105 The transatlantic comparison nevertheless still held symbolic value in that Britain, a self-evidently despotic imperial power, occupied a position as a remarkably lesser evil in comparison to the increased repression faced by radicals in the United States. Frederick Loudin similarly saw his accommodation to Britain as part of a broader political project, namely one of empowering the global Black diaspora. Although Africa was one of only two continents that Loudin did not visit with his Jubilee Singers, he wrote for Black newspapers from London during the Second Boer War, lobbying African American civic organizations to actively support the British war effort out of concern for “our people” living in South Africa.Footnote 106

Other formations of solidarity that deliberately repudiated the imperial nation-state would emerge in the coming decades, from the work of Marcus Garvey and his acolytes in the 1920s to a variety of international socialist movements that linked anti-colonial struggle worldwide with domestic racial inequality in the United States.Footnote 107 Increasingly, radicals conceptualized the global Black population as constituting a “nation” unto themselves. Though precedents to this argument emerged in the late nineteenth century, whether in the minor resurgence of “back to Africa” emigration schemes or in the personal disillusionment of figures like Frederick Loudin, the experience of World War I proved particularly crucial to a wider shift in perspective.Footnote 108 Growing numbers of observers saw in the European crisis a broader demonstration of the fallibility of the old imperial powers. Historian Jeannette Eileen Jones has highlighted a change in African American approaches to Africa that took place during this period, from a continent that willing collaborators could travel to with white benefactors in order to help to “redeem” from a state of supposed savagery to the nucleus of a broader movement to build solidarity and challenge European colonial influence.Footnote 109 Other African American performers, most notably Paul Robeson, would continue to use Britain and London in particular as a base for clarifying their Pan-African politics, but their Anglophilia now took a back seat to a universal resistance to racism and empire.Footnote 110 These later movements were linked to earlier transnational Black activism and performance, but mobility itself did not produce a politics that challenged these national boundaries. Instead, it was the rupture of conflict that expanded the accepted limits of the oppositional vision of America.

For the time being, the nation reigned supreme, even for those formulating a nascent internationalist or diasporic politics. W.E.B. Du Bois may have identified the global “Color Line” as the “problem of the twentieth century” in his opening address at the 1900 Pan-African Congress in London, but he also recognized that he spoke to a world artificially segmented by national borders and political systems. This reality shaped the propositions and avenues to liberation identified in his speech. While noting the commonalities between different systems of racial domination around the world, Du Bois almost immediately demarcated the terms of this system through distinctive national histories. On behalf of the conference, he appealed to Britain “as the first modern champion of Negro” to be the first to act by granting the right of self-government to its African and Caribbean colonies, and entreated the United States to “let not the spirit of Garrison, Phillips, and Douglass wholly die out.”Footnote 111 Even in an age of growing cooperation, differentiations between perceived national characteristics were inextricably tied to struggles over the global politics of race.Footnote 112 Whether or not he and his fellow delegates had any belief that these appeals would be heeded, at this point they had little other recourse.Footnote 113 This was the world that oppositional Americans stepped into, and, in tandem with the specific financial and social incentives entangled in transatlantic performance, it accounts for their fixation on the nation.

At the turn of the twentieth century, transatlantic performance played a powerful role in formulating a distinctly oppositional American identity. By embracing a performance politics that foregrounded national characteristics, African Americans were able to temporarily disrupt the dominant vision of American identity in Britain. The lasting impact of this work was nevertheless limited by infrastructural imbalances, an overreliance on British support, and an unwillingness to directly connect racial injustice within the United States with worldwide imperial rule.

However, this is not to suggest that these performers were simply short-sighted or misguided in their efforts. Rather, they were responding to changing political forces shaping culture in the United States and capitalizing on the attention generated by their overseas work. This experience, though formed by particular circumstances, contains a broader lesson for historians examining the international dimensions of anti-racist activism. One might assume that transnational mobility inevitably leads to an examination of the artificiality of the “national” as a catchall for vast domestic populations, or as a misnomer that concealed the coercive technologies of imperial rule. However, it just as often brings to the surface the perceived exceptional facets of national histories and culture.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Gary Gerstle, Sarah Hammond and the two anonymous reviewers whose feedback helped refine this article’s argument and structure. The research for this article was made possible by a PhD studentship from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (grant reference AH/L503897/1).