In 2018, The American Conservative expressed its concern about the conceptual inflation of the meaning of the term ‘racist’ in the following tweet:

There are people with far, far more offensive racial views than Donald Trump or Tucker Carlson. If Trump and Tucker are ‘racists,’ then what do you call those other people? (https://twitter.com/amconmag/status/1035230671256444928)

The American Conservative is not alone. This concern with conceptual inflation is shared across the political spectrum, and comes with a respectable intellectual pedigree. Sociologist Robert Miles has devoted an entire chapter to critiquing the conceptual inflation of ‘racism’ and ‘racist’ in Racism (Miles Reference Miles1989: ch. 2). In turn, Miles's critique has been echoed in philosophy of race by J. L. A. Garcia (Reference Garcia1997), Lawrence Blum (Reference Blum2002a: ch. 1; Reference Blum2002b), and Elizabeth Anderson (Reference Anderson2010: 47–48). This concern with conceptual inflation remains salient in ongoing philosophical debates; for example, Rima Basu (Reference Basu2019) defends her account of the wrongness of racist belief from a worry about conceptual inflation. This concern with conceptual inflation also appears in contributions that professional philosophers make to the ongoing popular discourse about racism (Case Reference Case2019; Preston Reference Preston2020).

We think worries about the conceptual inflation of ‘racist’ and related expressions are misplaced because they do not attend closely enough to the way ordinary speakers in fact use those expressions. Drawing on evidence from large linguistic corpora, we explain how these expressions fit into a standard semantic theory of adjectives and nominals. In particular, we show that ‘racist’ and similar expressions have semantic properties that allow their users to make nuanced expressions of moral condemnations with respect to different degrees of wrongness and with respect to different dimensions of ills. After showing how these expressions are actually used in ordinary language, we argue that the critics who raise the concern with conceptual inflation actually turn out to be the ones who are making a revisionary linguistic prescription: they are recommending that we engage in the conceptual deflation of ‘racist’ and similar terms relative to their current ordinary language meanings.

1. The Charge of Conceptual Inflation

Critics who raise the charge of conceptual inflation hold that, relative to some standard, the use of a term by some group has expanded to cover too wide a set of instances. These critics of conceptual inflation allege that the wide use of the term makes the term lose its nuanced meaning and, thereby, its moral force. In response, these critics favor restricting the use of the term to cover a narrower set of instances.

Blum provides a representative expression of this charge, with respect to the meaning of ‘racism’ and ‘racist’:

A major reason for what Robert Miles calls the ‘conceptual inflation’ (Miles, Reference Miles1989, pp. 41–68), to which the idea of ‘racism’ has been subject is its having become the central or even only notion used to mark morally suspect behavior, attitude, and social practice regarding race. The result—either something is racist, or it is morally in the clear . . . . If our only choices are to label an act ‘racist’ or ‘nothing to get too upset about’, those who seek to garner moral attention to some racial malfeasance will be tempted to call it ‘racist’. That overuse in turn feeds a diminishing of ‘racism's’ moral force, and thus contributes to weakened concern about racism and other racial ills. (Blum Reference Blum2002b: 206)

To name an act or a person ‘racism’ or ‘racist’ is particularly severe condemnation. But the terms are in danger of losing their moral force, for they have been subject to conceptual inflation (overexpansive usage) and moral overload (covering morally too diverse phenomena), thus inhibiting honest interracial exchange. (Blum Reference Blum2002a: 31)

On this characterization, the charge of conceptual inflation depends on an observation about the way language is actually used. Opponents of the conceptual inflation of ‘racism’ and related expressions allege that the wide conception of these terms obliterates different degrees of racial wrongs and obscures the diverse dimensions of racial ills. Instead, they claim that a race-talk vocabulary in which ‘racist’ is used only rarely, given that the term covers only a narrow set of instances, is more suitable for facilitating productive conversations about racial matters (Blum Reference Blum2002b: 217).

The charge of conceptual inflation is made with other terms in addition to ‘racism’ and ‘racist’. Garcia (Reference Garcia1997) and Blum (Reference Blum2002b) quote separate opinion pieces that make the charge of conceptual inflation with ‘sexism’ and ‘homophobia’. And Spencer Case (Reference Case2019) makes the charge of conceptual inflation with, among others, ‘sexism’ and ‘colonialism’. Let us provisionally dub this group of terms expressions condemning oppression because they all refer to and connect a particular instance—such as a person, an event, or an institution—to broader patterns of oppression and do so with the force of moral condemnation.

The dubbing is only provisional because, while it will be convenient to have a way to refer to this cluster of terms that frequently face the charge of conceptual inflation, we will also ultimately argue that—semantically speaking—they turn out to be unexceptional examples of adjectives and nominals that are gradable and multidimensional. Nevertheless, there may be a genealogical relationship that unites the most prominent expressions condemning oppression. Sally McConnell-Ginet (Reference McConnell-Ginet2020: 175–82) notes that ‘sexism’, ‘ableism’, ‘audism’, and ‘ageism’ are intentionally modeled after, and meant to evoke the moral force of, ‘racism’. In addition, ‘homophobia’ and ‘transphobia’ also have academic counterparts, ‘heterosexism’ and ‘cisgenderism’, that share the same genealogical relationship (Herek Reference Herek2004; Lennon and Mistler Reference Lennon and Mistler2014).

In its concern with the way expressions are actually used, the charge of conceptual inflation reflects a general concern with ordinary language in philosophers’ debate about the concept of racism (Taylor Reference Taylor2013: 36–53). In evaluating definitions of racism, Garcia (Reference Garcia1997: 6) appeals to a current usage criterion: that the concept of racism ‘conform[s] to our everyday discourse about racism, insofar as this is free from confusion’. Similarly, Blum (Reference Blum2002b: 209) appeals to ‘an agreed upon meaning for “racism’’’, which he believes ‘should facilitate interracial communication’. And Anderson (Reference Anderson2010: 47) makes the observation that ‘in popular moral discourse, the term “racist” is used as a severe character judgment, to label people such as neo-Nazis’. In the same spirit, Joshua Glasgow (Reference Glasgow2009: 64–65) explicitly states that analyses of the concept of racism ‘should accommodate ordinary usage of relevant terms, terms like “racism”’.

A careful look at these statements reveals an ambiguity in the charge of conceptual inflation that is worth clarifying. To get a sense of this ambiguity, consider a distinction that Charles Mills (Reference Mills2005: 553; see also Reference Mills2003: 32–34) draws:

Definitions can be thought of as falling roughly into two classes, the conventional, which accept and make more precise existing linguistic practice, and the revisionist, which seek to challenge existing linguistic practice. The task of the definer in the first case is to persuade us that her definition conforms to standard usage (perhaps with some refinements), while in the second case to persuade us that her definition is an improvement over standard usage.

Recall our rough characterization of the charge of conceptual inflation: the use of a term by some group has expanded too much relative to some standard. This standard, drawing on Mills's distinction, has both descriptive and prescriptive varieties, which correspond to two related variants of the charge of conceptual inflation:

The Descriptivist Charge of Conceptual Inflation: The use of a term by some group has expanded too much relative to its meaning in ordinary language.

The Prescriptivist Charge of Conceptual Inflation: The use of a term by some group has expanded too much relative to the meaning it should have in ordinary language.

The descriptive standard directly appeals to ordinary meaning. The descriptivist charge of conceptual inflation alleges that the ordinary meaning of the term in question is narrow. Thus, those who use an expression according to the wide conception include ‘too much’ relative to this descriptive standard, thereby diverging from the ordinary meaning of the relevant expression.

By contrast, the prescriptive standard appeals to ordinary use of language in two distinct ways. First, a prominent version of the prescriptivist charge of conceptual inflation alleges that use of the term in question should be narrow because its ordinary meaning is narrow. Those who use an expression according to the wide conception include ‘too much’ relative to a prescriptive standard because they include ‘too much’ relative to a descriptive standard. This appeal to meaning in ordinary language reveals a premise in the argument of those who oppose conceptual inflation that is typically assumed without justification: the fact that the meaning of the term is narrow is a reason to think that it should be narrow. This premise is a specific instance of a general background view about language, meaning conservatism, which aims to preserve the current ordinary language meaning of a term. As Alberto Urquidez (Reference Urquidez2020: 231) characterizes this view, ‘conservatives believe that disagreement about the meaning of “racism” can be resolved by reference to ordinary usage of this term’. Moreover, Urquidez (Reference Urquidez2018, Reference Urquidez2020) argues that while few conservatives realize it, meaning conservatism is itself a normative view insofar as it offers a default prescription for how language should be used (compare Lindauer Reference Lindauer2020). On this first type of appeal to meaning in ordinary language, meaning conservativism directly connects the prescriptivist charge of conceptual inflation to a descriptivist foundation.

Second, a different version of the prescriptivist charge of conceptual inflation alleges that the use of the term in question should be narrow because that makes it more suitable for facilitating productive conversations. The prescriptivist charge could, in principle, be made completely independently of facts about whether the ordinary meaning of the term in question is narrow or wide. But in practice the prescriptivist charge of conceptual inflation is not completely independent from assumptions about the ordinary use of the relevant expressions. It assumes that narrow uses of the relevant expressions are better at facilitating communication than wide uses, and whether that is true is at least partly an empirical question. As we will argue below, expressions condemning oppression are unexceptional examples of other gradable, multidimensional adjectives with wide meanings, and there is no reason to think that other gradable, multidimensional adjectives with wide meanings are worse at facilitating communication than expressions with narrow meanings. The burden should therefore be on critics of conceptual inflation to give some evidence that expressions with narrow meanings are better at facilitating communication.

Facts about the ordinary use of expressions condemning oppression are therefore relevant to assessing the descriptivist charge of conceptual inflation and to meaning conservatism, a form of the prescriptivist charge of conceptual inflation that directly appeals to patterns of ordinary use. Facts about the ordinary use of expressions are also relevant to assessing forms of the prescriptivist charge of conceptual inflation that do not make any direct appeals to ordinary use insofar as these facts challenge the idea that narrow meanings better facilitate communication than wide meanings.

Drawing the distinction between descriptive and prescriptive versions of the charge of conceptual inflation also shows how our response to the critics differs from existing responses in this debate. Other philosophers have given normative responses to the charge of conceptual inflation (Shelby Reference Shelby2003, Reference Shelby2014; Headley Reference Headley2006; Hardimon Reference Hardimon2019). For example, Tommie Shelby (Reference Shelby2003: 125) argues that Blum ‘overestimates the negative impact of contemporary uses of “racism” and underrates their value to those who are most vulnerable to being victimized by race-related offenses’. While these normative responses repudiate the prescriptivist charge of conceptual inflation, they essentially concede the descriptivist charge. For example, Shelby (Reference Shelby2014: 59) notes that ‘Despite the obvious merits of Blum's narrow-scope conception of racism, I favor a broader conception, one that has a different focus and that gives less weight to how the term is used in everyday life’. While we sympathize with these normative responses, we also believe that they have been overly concessive with respect to critics’ claims about ordinary language.

We aim to give an empirical response that pushes back directly on the descriptivist charge of conceptual inflation and thereby also indirectly on the prescriptivist charge of conceptual inflation by undermining its descriptivist foundation and undercutting the normative arguments that depend on assumptions about ordinary meaning. We draw a theoretical framework from formal semantics and evidence from linguistic corpora to make our empirical response. We will present evidence that everyday uses of expressions condemning oppression allow for nuance with respect to different degrees of wrongs and diverse dimensions of ills. We will also present evidence that the ordinary language meanings of expressions condemning oppression are actually wide rather than narrow based on two ways of precisifying the notions of ‘wide’ and ‘narrow’ meaning: namely, with respect to these expressions’ degree and dimension structures.

In fact, these precisifications reveal that expressions condemning oppression are semantically unexceptional: they resemble other terms with wide meanings that are commonly used in ordinary language that do not standardly threaten productive conversations. We agree with Urquidez (Reference Urquidez2020: 245) that in theorizing about the meaning of ‘racism’, ‘empirical investigation is required to identify the pertinent facts and organize them into a plausible normative argument for or against ordinary usage’. Our primary aim is to present those pertinent facts about ordinary use. Our empirical response is distinct from, but congruent with, existing normative responses to the charge of conceptual inflation.

2. Linguistic Corpora and Applied Ordinary Language Philosophy

Our approach is to investigate empirically how expressions condemning oppression are used in ordinary language. We will be applying standard diagnostic tests drawn from semantic theories of adjectives to ‘racist’ and other expressions condemning oppression as they occur in large English corpora. Our approach can therefore be considered a form of applied ordinary language philosophy, using non-armchair methods (Hansen Reference Hansen2014).

Classic, mid-twentieth-century ordinary language philosophy was criticized for basing claims about the ordinary use of various expressions on the judgments of a small group of elite speakers whose judgments did not always align with each other (Mates Reference Mates1958; Tennessen Reference Tennessen1965; Hansen Reference Hansen2017). Contemporary ordinary language philosophy has the advantage of having access to large-scale, easily searchable linguistic corpora that provide evidence of patterns of use that range far beyond Oxford senior common rooms. While linguistic corpora have long been a standard empirical resource in linguistics, philosophers have only recently started to take advantage of evidence drawn from linguistic corpora to inform debates about the meaning of ‘know’ (Ludlow Reference Ludlow, Preyer and Peter2005; Pinillos and Nichols Reference Pinillos and Nichols2018; Hansen, Porter, and Francis Reference Hansen, Porter and Francis2021), to challenge philosophers’ informal judgments about the meaning of disposition ascriptions (Vetter Reference Vetter2014), in support of the idea that aesthetic adjectives behave differently from relative adjectives (Liao, McNally, and Meskin Reference Liao, McNally and Meskin2016), to investigate the way people talk about causation (Sytsma et al. Reference Sytsma, Bluhm, Willemsen, Reuter, Fischer and Curtis2019), and to track the changing frequency of philosophers’ talk about ‘intuitions’ (Andow Reference Andow2015). In parallel with philosophers’ recent discovery of how useful linguistic corpora can be for uncovering facts about ordinary use, lawyers and judges have started to cite corpora as evidence for the ‘ordinary meaning’ of key expressions in legal cases, rather than relying solely on dictionary entries or judges’ potentially idiosyncratic linguistic judgments (Lee and Mouritsen Reference Lee and Mouritsen2017; Goldfarb Reference Goldfarb2017; Tobia Reference Tobia2020).

Throughout our empirical investigation, we look at the semantic properties of ‘racist’ rather than ‘racism’—and, likewise, ‘sexist’ rather than ‘sexism’ and ‘homophobic’ rather than ‘homophobia’—because we think doing so enables us to focus only on uses of these terms that involve moral condemnation (compare Hardimon Reference Hardimon2019: 224 on different senses of ‘racism’). We think closer attention to the resources available in ordinary language, specifically the linguistic devices we have in English for modifying ‘racist’, can inform theorizing about concepts such as racism and likewise about other expressions condemning oppression and their corresponding concepts.

There is no universal English corpus, and any particular corpus will have limitations. The example sentences we discuss later are drawn from Corpus of Global Web-based English (GloWbE) unless noted otherwise (infelicitous and questionable examples—marked with ‘#’ and ‘??’—are exceptions). GloWbE contains 1.9 billion words of text from websites based in twenty different countries (Davies Reference Davies2013). We chose GloWbE because of its large size and international coverage.Footnote 1 GloWbE is a corpus of web-based English, so one limitation of GloWbE is that it does not capture patterns of use from the more distant past. Because we are primarily interested in the charge of conceptual inflation as a contemporary issue, this is not a serious limitation for our investigation.

That said, the charge of conceptual inflation can also be investigated primarily as a historical issue. Among Garcia's (Reference Garcia1997: 6) criteria for evaluating an understanding of the concept of racism, there is a historical usage criterion: that the concept of racism ‘either stand[s] continuous with past uses of the term “racism”, or involve[s] a change of the term's meaning that represents a plausible transformation along reasonable lines of development’. To examine historical usage, we can turn to the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA), which contains 400 million words of text from 1810–2009 (Davies Reference Davies2010). Although the evidence is limited, given the smaller corpus, we have some reason to believe that the semantic facts we uncover with contemporary uses also hold true of earlier uses. For example, the semantic property of gradability can be found in both contemporary and earlier uses of ‘racist’. In COHA, gradable occurrences of ‘racist’ go back at least to the mid-1960s, as the following passage from a 1964 issue of The New Republic demonstrates:

‘There has been a spectrum in geography running from the deepest, most racist South, typified by Mississippi, to the middle tokenism South, typified by North Carolina, to the border states and to the North, where problems of race blur into circular issues of poverty, family deterioration, urban blight, and so forth, which cut across race lines.’

In addition, as John McWhorter (Reference McWhorter2020) notes, prior to the 1970s and 1980s, ‘prejudiced’ was the more common term to refer to racial bias. And, not surprisingly, we also find gradable occurrences of ‘prejudiced’ (in the racial sense) in COHA.

A more important limitation of GloWbE is that it only captures patterns of use by those portions of the population who have internet access, which means it is missing the poorest and least educated users of English (Pew Research Center 2019). But even with those limitations in mind, we think GloWbE is a suitable tool for our investigation because only in a very large corpus will we find enough examples of the kinds of expressions that we are interested in. In smaller corpora, there are not enough occurrences of expressions condemning oppression to reveal meaningful patterns of use (though as we will discuss in section 3.2 below, even GloWbE needs to be supplemented with additional evidence when certain expressions occur only very rarely).

3. Response to the Descriptivist Charge of Conceptual Inflation: Degrees

Critics who raise the descriptivist charge of conceptual inflation allege that the ordinary meaning of a term in question is narrow and accuse those who use that term on the wide conception as using it to cover too wide a set of instances relative to its meaning in ordinary language. When it comes to expressions condemning oppression, as exemplified by ‘racist’, critics allege that the wide conception obliterates the ability to pick out different degrees of wrongs, such that people who use these terms are left with an apparent choice between calling something ‘racist’ or seeing it as of no moral concern at all.

Given this allegation, in this first part of our empirical response we focus on semantic features of ‘racist’ and other expressions condemning oppression. We show that in their adjectival forms, these terms function as gradable adjectives—that is, adjectives that admit of degrees—and that their nominal forms also exhibit hallmarks of gradability. Given the repertoire of degree modifiers available in English, users of expressions condemning oppression can, and in fact do, express a broad spectrum of moral condemnation with these terms. Moreover, through examining the application patterns of these terms’ adjectival forms, we argue that they have a minimum rather than a maximum standard of application, such that, for example, a particular instance only needs to be racist to a minimal degree to be appropriately described as ‘racist’. That is, in terms of their scale structure, expressions condemning oppression have wide, rather than narrow, ranges of application in their ordinary language meanings.

3.1. Gradability of Expressions Condemning Oppression

Adjectives are gradable when they admit of comparative constructions and degree modifiers (Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972). Take ‘big’ as a paradigmatic example: it is felicitous to say ‘an elephant is bigger than an ant’ and ‘an elephant is very big’. Gradable adjectives have received a great deal of attention from semanticists and philosophers of language, and there are competing semantic theories of how best to explain the ways they function when combined with degree modifiers and in comparative constructions (see, for example: Kennedy and McNally Reference Kennedy and McNally2005; Rotstein and Winter Reference Rotstein and Winter2004; McNally Reference McNally, Nouwen, Rooij, Sauerland and Schmitz2011; Toledo and Sassoon Reference Toledo and Sassoon2011; Sassoon Reference Sassoon2013; Burnett Reference Burnett2014, Reference Burnett2016; Wellwood Reference Wellwood2019). Our aim in this paper is not to take a side in those debates, but to make the case that expressions condemning oppression such as ‘racist’, in their adjectival form, are utterly unexceptional gradable adjectives.

As mentioned earlier, characteristic features of gradable adjectives include the ability to appear felicitously in comparative constructions and combine with degree modifiers. We find evidence in GloWbE that ‘racist’ is used in comparative constructions, such as:

(1) Adolf Hitler was certainly more racist than the leaders of America are today…

(2) London is a lot less racist than America.

And we also find evidence that ‘racist’ combines with degree modifiers, such as:

(3) Power rangers [sic] was the most racist show on tv haha …

(4) I hate indian [sic] people because they are so racist …

(5) … in fact the Chinese are very racist, especially to non-Chinese Asians.

(6) What are the least racist cities in America?

Because ‘racist’ is a gradable adjective, we are not limited to describing things as either ‘racist’ or ‘of no moral concern at all’. Even Blum ultimately observes that ‘racism comes in degrees, and it is worse to be more rather than less racist’ (Blum Reference Blum2002a: 29). There is a broad spectrum of moral condemnation that can be communicated by combining degree modifiers with ‘racist’: saying that something is ‘extremely racist’ or ‘very racist’, all else being equal, expresses stronger moral condemnation than saying it is ‘slightly racist’ or ‘kinda racist’. In fact, our investigation into ordinary uses of ‘racist’ shows that the fact that racism comes in degrees is present in everyday discourse about racism.

The same semantic features about gradability can be observed with other expressions condemning oppression. They too admit of comparative constructions, such as

(7) … I've found the British men to be far more sexist than their Australian counterparts!

And they too combine with degree modifiers, such as

(8) The Prime Minister himself has shown that he is leading a very homophobic country and he has no problem with that.

Due to their gradability, these other expressions condemning oppression are also capable of figuring in nuanced moral condemnations. After doing some empirically-informed ordinary language philosophy, we can see that the way they do is semantically unexceptional.

So far, we have focused on the adjectival form of ‘racist’ and other expressions condemning oppression. But opponents of conceptual inflation might complain that this focus misses out on what they take to be the most controversial use of the term: the use of ‘racist’ and other expressions condemning oppression in nominal form to describe a person. And so we turn next to consider nominal forms of expressions condemning oppression.

The nominal form of ‘racist’ (including ‘racists’) is also relatively common in English, occurring about half as frequently (9.7 words per million) as the adjectival form (16.87 words per million) in GloWbE. Without diving into the details of the relation between the semantics of nominals and adjectives, it is sufficient for our purposes to point out that the nominal form of ‘racist’ and other expressions condemning oppression are also gradable, like their adjectival forms (Morzycki Reference Morzycki2016: ch. 6).

The nominal form of ‘racist’, like the adjectival form, can occur in comparative constructions, and it can be modified with size adjectives like ‘big’ and ‘huge’ (though not with ‘small’ or ‘tiny’; see Morzycki Reference Morzycki2009):

(9) Himself a Chiss, a race of blue skinned, red eyed humanoids, he acquired the rank of Grand Admiral … a [sic] unprecedented achievement considering the Emperor was a huge racist and xenophobe.

(10) Glenn Beck of Fox simply dismissed Woodrow Wilson as ‘a big racist’.

(11) Joe is a bigger racist than I thought he was.

(12) He is more of a racist than Bull Conner [sic] ever was at Binmingham [sic].

The fact that the nominal form of ‘racist’ can occur in comparative constructions and be modified with adjectives like ‘huge’ and ‘big’ indicates that it is associated with a scale measuring degrees to which a person can be a racist (Morzycki Reference Morzycki2016). As such, even when ‘racist’—and, by analogy, other expressions condemning oppression—in its nominal form is used to describe a person, speakers can still make use of the descriptive resources available in ordinary language to express nuanced moral condemnations in ways that are semantically unexceptional.

3.2. Application Thresholds of Expressions Condemning Oppression

In addition to demonstrating that ‘racist’ is a gradable adjective, we can also use English corpora to reveal a more subtle semantic fact about ‘racist’—namely, the type of gradable adjective that it is. Christopher Kennedy and Louise McNally (Reference Kennedy and McNally2005) have developed an influential typology of gradable adjectives (see also Unger Reference Unger1971). On this typology, relative gradable adjectives—such as ‘big’ and ‘tall’—have context-dependent standards: whether they can be felicitously applied to an instance depends on, for example, the comparison class salient in the conversational context. By contrast, absolute gradable adjectives have comparatively context-independent standards. There are two types of absolute gradable adjectives (see also Rotstein and Winter Reference Rotstein and Winter2004). Minimum-standard absolute gradable adjectives—such as ‘dirty’ and ‘bumpy’—can be felicitously applied to an instance once it has a minimal degree of the relevant underlying property. Maximum-standard absolute gradable adjectives—such as ‘clean’ and ‘flat’—can be felicitously applied to an instance only once it has a maximal degree of the relevant underlying property. There is a general recognition that even absolute gradable adjectives can still be context-dependent in some ways even though there are ongoing debates about whether these phenomena are best captured semantically or pragmatically as well as about the extent of context-dependence in absolute adjectives (see, for example: Toledo and Sassoon Reference Toledo and Sassoon2011; McNally Reference McNally, Nouwen, Rooij, Sauerland and Schmitz2011; Burnett Reference Burnett2014, Reference Burnett2016; Liao, McNally, and Meskin Reference Liao, McNally and Meskin2016; Hansen and Chemla Reference Hansen and Chemla2017; Liao and Meskin Reference Liao and Meskin2017).

On our rough characterization, critics who raise the charge of conceptual inflation with ‘racism’ and ‘racist’ favor a narrow conception of these terms, and they are targeting those who favor a wide conception of these terms. The notions of ‘narrow’ and ‘wide’ in this rough characterization are admittedly vague, but one way they can be made more precise is by using the typology of different kinds of gradable adjectives. On the wide conception, something needs to be racist only to a minimal degree for it to be appropriately described as ‘racist’. That is, the wide conception plausibly takes ‘racist’ to be a minimum-standard absolute gradable adjective, given Kennedy and McNally's typology. By contrast, on the narrow conception, something must be racist to a maximal degree for it to be appropriately described as ‘racist’. That is, the narrow conception takes ‘racist’ to be a maximum-standard absolute gradable adjective. Sometimes this understanding is stated explicitly, such as in Anderson's (Reference Anderson2010) observation that, in popular moral discourse, ‘racist’ is reserved for making extreme character judgments. Other times, this understanding is conveyed implicitly, shown by the entailment pattern that opponents of conceptual inflation allege is licensed by ordinary uses of ‘racist’.

One diagnostic for classifying gradable adjectives is based on the entailment patterns that they standardly license (Toledo and Sassoon Reference Toledo and Sassoon2011). In particular, maximum-standard absolute gradable adjectives standardly license the following entailment pattern:

For example: table x is cleaner than table y; therefore table y is not clean. By contrast, minimum-standard absolute gradable adjectives standardly license a distinct entailment pattern:

For example: table x is dirtier than table y; therefore, table x is dirty. Finally, relative gradable adjectives standardly license neither entailment pattern. For example: ‘table x is bigger than table y’ does not entail that table y is not big, nor does it entail that table x is big. In the tweet quoted at the beginning of this paper, The American Conservative implicates that ‘racist’ follows the entailment pattern characteristic of maximum-standard absolute gradable adjectives: there are people more racist than Trump and Carlson; therefore, Trump and Carlson are not racist.

Is ‘racist’ best classified as a maximum-standard absolute gradable adjective, as opponents of conceptual inflation seem to understand it? To answer this empirical question, we can return to English corpora and apply another diagnostic for classifying gradable adjectives, which targets their characteristic degree modifiers (Rotstein and Winter Reference Rotstein and Winter2004). Maximum-standard absolute gradable adjectives felicitously combine with the modifier ‘almost’.Footnote 2 Minimum-standard absolute gradable adjectives felicitously combine with the modifier ‘slightly’. And relative gradable adjectives felicitously combine with neither modifier. For example, it is felicitous to say ‘this table is almost clean’ (maximum-standard), but infelicitous to say ‘this table is almost dirty’ (minimum-standard) or ‘this table is almost big’ (relative). And it is felicitous to say ‘this table is slightly dirty’, but infelicitous to say ‘this table is slightly clean’ or to say ‘this table is slightly big’. (However, note that sometimes people say ‘this table is slightly big’ to express the different thought that the table is slightly too big—see Rotstein and Winter [2004] for discussions of contextual variability in the way these modifiers combine with different types of gradable adjectives.)

GloWbE confirms these patterns are borne out in ordinary use:

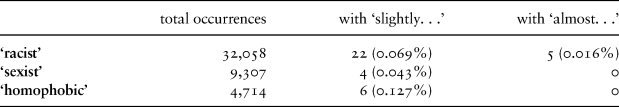

Table 1. Frequencies of modification for paradigmatic adjectives of different types

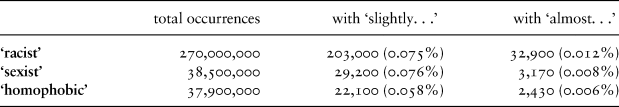

In GloWbE, we do find a handful of uses of ‘racist’ with ‘almost’. However, we find more uses of ‘racist’ with ‘slightly’. This pattern also holds with ‘sexist’ and ‘homophobic’, for which there are no examples of modification with ‘almost’ in the corpus (see table 2).

Table 2. Frequencies of modification for adjectival expressions condemning oppression in GloWbE

The number of occurrences of these expressions in GloWbE is very small, therefore we should be cautious about drawing strong conclusions from them. But there are other patterns that support the claim that expressions condemning oppression combine more readily with ‘slightly’ than with ‘almost’. Google searches for the relevant strings turn up the same pattern of preference for modifying expressions condemning oppression with ‘slightly’ over ‘almost’:

Table 3. Frequencies of modification for expressions condemning oppression in Google (July 2021)

As with the patterns from GloWbE, we should not put too much weight on the results of these Google searches by themselves; they are estimates rather than exact counts and do not distinguish between parts of speech (for Google's limitations as a corpus, see https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/compare-google.asp). What matters for our purposes are the relative frequencies at which expressions condemning oppression are modified with ‘slightly’ versus ‘almost’, and the patterns from Google searches align with and clarify the patterns from GloWbE.

Given these patterns of occurrences from GloWbE and Google, in which expressions condemning oppression are modified more frequently with ‘slightly’ than with ‘almost’, we believe that these expressions should not be classified as maximum-standard absolute gradable adjectives or as relative standard gradable adjectives. (Kristen Syrett [Reference Syrett2007: 162] claims in passing that ‘racist’ is a non-maximum-standard adjective.) Instead, they should be classified as minimum-standard absolute gradable adjectives. ‘Racist’, therefore, does not license the entailment pattern suggested by The American Conservative: that there are people more racist than Trump and Carlson does not by itself tell us whether Trump and Carlson can be appropriately described as ‘racist’ or not.

If this classification is correct, then ‘racist’ and other expressions condemning oppression function like other minimum-standard absolute gradable adjectives such as ‘dirty’ and ‘bumpy’. In the same way that a thing's being dirty to some degree entails that it can be felicitously described as ‘dirty’, full stop, a thing's being racist to some degree entails that it can be felicitously described as ‘racist’, full stop. This fact about the semantics of ‘racist’ may be part of what opponents of conceptual inflation are reacting to, but it does not entail that ‘racist’ cannot be used to pick out varying degrees of racism. As noted earlier, we find frequent uses of degree modifiers—such as ‘most’, ‘so’, ‘very’, ‘least’, ‘extremely’, ‘really’, ‘pretty’, ‘highly’, ‘incredibly’, ‘rather’—in combination with ‘racist’ in English corpora. To generalize from the case of ‘racist’, we can conclude that the ordinary meanings of expressions condemning oppression are wide rather than narrow in terms of their standards on a scale of degrees, and we maintain that this fact is compatible with their uses in nuanced moral condemnations. Importantly, the fact that the ordinary meaning of ‘racist’ admits of different degrees does not imply that it is intrinsically confusing, or that it is unsuitable for facilitating productive conversations. Unless we are willing to similarly restrict the everyday use of other minimum-standard gradable terms, we should be also unwilling to do so for ‘racist’ and other expressions condemning oppression.

4. Response to the Descriptivist Charge of Conceptual Inflation: Dimensions

Critics who raise the descriptivist charge of conceptual inflation allege that the ordinary meaning of a term in question is narrow and accuse those who use that term on the wide conception as covering too wide a set of instances relative to its meaning in ordinary language. When it comes to expressions condemning oppression, as exemplified by ‘racist’, critics allege that the wide conception obscures the diversity of ills that ‘racist’ is used to describe, and they recommend an alternative vocabulary for oppression-talk. For example, they recommend only rarely using ‘racist’ and using instead other terms such as ‘racial insensitivity’, ‘racial injustice’, ‘racial ignorance’, and so on.

Given this allegation, in this second part of our empirical response, we focus on the dimension structure of ‘racist’ and other expressions condemning oppression. We argue that they are multidimensional adjectives—that is, adjectives that are associated with multiple scales that can order objects in different ways. We also show that even their nominal forms exhibit hallmarks of multidimensionality. Given the rich linguistic repertoire available in English, users of expressions condemning oppression can, and in fact do, express a diverse range of moral condemnation with these terms. Moreover, through examining the way these expressions combine with exception phrases, we argue that their application criteria are disjunctive rather than conjunctive, such that, for example, a particular instance needs to be racist on only one dimension to be felicitously described as ‘racist’. That is, in terms of dimensions, expressions condemning oppression have wide, rather than narrow, ranges of application.

4.1. Multidimensionality of Expressions Condemning Oppression

Adjectives are multidimensional when their application depends on multiple dimensions along which orderings of objects might differ (Kamp Reference Kamp and Keenan1975; Klein Reference Klein1980). Again, take ‘big’ as a paradigmatic example: it is felicitous to say ‘Tokyo is bigger than Kinshasa’ with respect to population size, and it is also felicitous to say ‘Kinshasa is bigger than Tokyo’ with respect to geographical size.

One characteristic feature of multidimensional adjectives is that they can be modified by quantification markers such as ‘in some way’ and ‘in every respect’ (Sassoon Reference Sassoon2013; but see Solt Reference Solt, Castroviejo, McNally and Sassoon2018: 70–78 for complications). For example, it is felicitous to say that someone is ‘healthy in every respect’, where ‘healthy’ is a paradigmatically multidimensional adjective, but it is not felicitous to say that someone is ‘tall in every respect’, where ‘tall’ is a paradigmatically unidimensional adjective. And we find evidence in GloWbE that ‘racist’ can be modified by quantificational markers:

(13) It is not racist in any way at all, though, to judge some cultures as better than others on a host of criteria.

(14) Some people like to make out that Elvis was racist in some ways.

Searching for appearances of ‘in’ immediately after ‘racist’, we also find specific dimensions that are contextually salient. For example:

(15) … libertarianism could be seen as having consequences that would empower racists, although not racist in intent.

(16) The same thing happens when we say that an action is racist in effect if not in intention.

(17) Prohibiting mixed marriages is not racist in the same way as, say, Jim Crow laws.

The multidimensionality of ‘racist’ interacts with its gradability (compare Liao and Huebner Reference Liao and Huebner2021: note 13). That is, ordinary uses of ‘racist’ indicate that one can be more or less racist depending on the relevant way in which one is racist. Take the following sentence drawn from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; Davies Reference Davies2008):

(18) . . . he's slightly racist but in an old-person type way not in a hateful type way.

In example sentence (18), the speaker distinguishes two different dimensions along which one's racism can be measured and says that the target of the statement has a positive degree on one dimension, but a zero degree on the other.

Multidimensionality can also be observed with other expressions condemning oppression. They, too, can be modified by quantificational markers, such as

(19) Go play my little pony [sic] if you want a game that isn't sexist in some way.

And modifiers can be used to pick out specific dimensions that are contextually salient, such as:

(20) ‘Ladies Night’ is sexist in the way that pink aisles of children's toys are sexist.

The multidimensionality of expressions condemning oppression is another expressive resource such expressions have for making nuanced moral condemnations. Once again, an empirically informed approach to studying ordinary language shows that these expressions do so in ways that are semantically unexceptional for gradable, multidimensional adjectives.

Like the adjectival form of ‘racist’, the nominal form encodes different dimensions in which people are racists and which can be quantified:

(21) Barrack [sic] Obama is a racist in every way.

And speakers can specify specific dimensions in which people are racists:

(22) I would rather be a racist in my words rather than a racist in my deeds.

Thus, like the adjectival form, the nominal form of ‘racist’, as it occurs in ordinary language, can be used to express varying dimensions along which people are racists when it is combined with descriptive resources present in ordinary language (but see Sassoon [Reference Sassoon2011] for subtle differences between multidimensionality in adjectives versus in nominals). Because ‘racist’—whether in its adjectival or nominal form—is gradable and multidimensional, it allows for nuance with respect to describing different degrees of racial wrongs and diverse dimensions of racial ills. To emphasize our central point, our investigation into ordinary uses of ‘racist’ and other expressions condemning oppression shows that the fact that racism and other forms of oppression come in different degrees and dimensions is registered in ordinary language.

4.2. Dimension Quantification of Expressions Condemning Oppression

In addition to demonstrating that ‘racist’ is a multidimensional adjective, we can also use English corpora to reveal a more subtle semantic fact about ‘racist’—namely, the type of multidimensional adjective that it is. Multidimensional adjectives can be classified according to whether they felicitously apply only to instances that meet the relevant standard on all of their dimensions or also to instances that meet the relevant standard on only some of their dimensions. For example, for something to count as healthy, it needs to be healthy in all respects or dimensions; for something to count as sick, it only needs to count as sick in one respect or dimension (Hoeksema Reference Hoeksema, van der Does and van Eijck1995). Galit Weidman Sassoon (Reference Sassoon2013: 339) calls the first type of multidimensional adjective conjunctive, meaning the adjective applies only if all of the dimensions are satisfied, and the second type disjunctive, meaning the adjective applies if at least one of its dimensions is satisfied.

On our rough characterization, critics who raise the charge of conceptual inflation with ‘racism’ and ‘racist’ favor a narrow conception of these terms, and they are targeting those who favor a wide conception of these terms. As mentioned earlier, the notions of ‘narrow’ and ‘wide’ in this rough characterization are admittedly vague, and one way they can be made more precise is in terms of their standards of application on a scale of degrees. Another (compatible) way they can be precisified is in terms of their standards of application with regard to dimensions: that is, whether they are conjunctive or disjunctive. On the wide conception, something needs to be racist on only one dimension for it to be appropriately described as ‘racist’. That is, the wide conception plausibly takes ‘racist’ to be a disjunctive multidimensional adjective, given Sassoon's typology. By contrast, if ‘racist’ is indeed multidimensional, then on the narrow conception, something must be racist on all dimensions for it to be appropriately described as ‘racist’. That is, the narrow conception plausibly takes ‘racist’ to be a conjunctive multidimensional adjective. While this narrow conception is rarely overtly stated, it often covertly operates in the background: for example, when one argues that a policy that admittedly produces racially discriminatory effects is not aptly called ‘racist’ if it is not also designed with racially prejudicial intentions.

Sassoon (Reference Sassoon2013) proposes a syntactic test for determining whether an adjective is conjunctive or disjunctive: if an adjective can felicitously combine with the exception phrase ‘except’ in its positive form and not in its negative form, that is evidence that it is conjunctive and not disjunctive. The test is based on the more general phenomenon that exception phrases can combine with universal quantifiers but not with existential quantifiers, as exemplified by the following sentences (Sassoon Reference Sassoon2013: 343):

(23) Everyone is happy except for Dan.

(24) No one is happy except for Dan.

(25) # Someone is happy except for Dan.

Because conjunctive multidimensional adjectives require an instance to satisfy all of their associated dimensions, their compatibility with exception phrases should pattern like universal quantifiers, and disjunctive multidimensional adjectives should pattern with existential quantifiers with respect to compatibility with exception phrases.

‘Healthy’ and ‘sick’ can be distinguished using this test (the felicitous example (26) below is from GloWbE; (29) is a version of a felicitous example from Sassoon Reference Sassoon2013: 345):

(26) She was perfectly healthy except for missing one eye. [conjunctive]

(27) # She's sick except for having normal blood pressure. [disjunctive]

As Sassoon points out, the test is inverted in negative contexts because while conjunctive multidimensional adjectives (‘healthy’, for example) require an object to satisfy all of the relevant dimensions, the negation of a conjunctive multidimensional adjective requires an object to satisfy only one of the relevant dimensions (‘not healthy’); disjunctive multidimensional adjectives (‘sick’, for example) require an object to satisfy only one of the relevant dimensions, while the negation of a conjunctive multidimensional adjective (‘not sick’) requires that the object satisfy all of the relevant dimensions:

(28) # She wasn't healthy except for her blood pressure. [conjunctive]

(29) She's not sick except for having high blood pressure. [disjunctive]

How do expressions condemning oppression behave when combined with ‘except’ in positive and negative contexts? The data are a little muddy, primarily because the combination of ‘except’ with expressions condemning oppression is relatively rare, even in large corpora. But we think the existing evidence points toward classifying expressions condemning oppression with disjunctive multidimensional adjectives. Consider the following felicitous example of ‘racist’ (in nominal form) from GloWbE combining with ‘except’ in a negative context and its adjective counterpart (which does not appear in the corpus but which sounds felicitous):

(30) I'm not a racist except for the company I keep.

(31) I'm not racist except for the company I keep.

Combining ‘racist’ with ‘except’ sounds noticeably worse—though not completely unacceptable—in positive contexts:

(32) ?? I'm a racist except for the company I keep.

(33) ?? I'm racist except for the company I keep.

That pattern of comparative acceptability points toward ‘racist’ being a disjunctive multidimensional adjective.

‘Sexist’ displays a similar pattern of comparative acceptability when combined with ‘except’ in negative versus positive contexts. For example, ‘except’ sounds acceptable when combined with ‘sexist’ in negative contexts, as in:

(34) … he wasn't sexist, except for when it came to women on the police force. (https://www.womensmediacenter.com/fbomb/im-not-at-all-sexist-except)

Combining ‘sexist’ with ‘except’ in a positive context sounds borderline acceptable, but worse than it sounds in the negative context:

(35) ?? … he was sexist, except for when it came to women on the police force

These patterns are evidence that expressions condemning oppression are disjunctive—an instance only needs to satisfy one of the dimensions associated with ‘racist’, ‘sexist’, or ‘homophobic’ in order for the terms to apply felicitously. For example, assuming ‘racist’ includes dimensions for racist in intent and racist in effect, then if something is racist in intent, but not in effect, or vice versa, that is sufficient for ‘racist’ to apply to that thing. Indeed, the earlier example sentence (18) offers an illustration: the speaker is applying ‘racist’ to someone who is racist in one way (an ‘old-person type way’) but not in another (a ‘hateful type way’).

There are bound to be disputes about which dimension is, or should be, most salient in a given context or about whether certain dimensions should be part of the meaning of the expression at all. But this is just an unexceptional pattern with multidimensional adjectives (compare Väyrynen Reference Väyrynen2014). Consider, for example, debates about what dimensions should figure in rankings of ‘top tier’ law schools (Espeland and Saunder Reference Espeland and Saunder2016) or what dimensions should figure in assessments of how painful something is (Borg, Salomons, and Hansen Reference Borg, Salomons, Hansen and Rysewyk2019: 276–77). Importantly, the fact that the ordinary meaning of ‘racist’ includes a disjunction of multiple dimensions over which disputes exist does not imply that the term is intrinsically confusing or that it is unsuitable for facilitating productive conversations. Unless we are willing to similarly restrict the everyday use of other disjunctive multidimensional terms, we should be also unwilling to do so for ‘racist’ and other expressions condemning oppression.

5. Response to the Prescriptivist Charge of Conceptual Inflation

Let us recap central findings from our empirical investigation of expressions condemning oppression. We have shown that these terms, in both their adjectival and nominal forms, are gradable and multidimensional. And so, with resources available in ordinary language, they can be used to pick out different degrees of wrongs and diverse dimensions of ills. Hence, they can be—and in fact are—used to express nuanced moral condemnations in ways that are typical of gradable, multidimensional adjectives. Moreover, we have found that on two ways of precisifying the distinction between narrow and wide conceptions of these terms—namely, in terms of their degree and dimension structures—their ordinary meanings are wide rather than narrow: they function as minimum-standard rather than maximum-standard gradable adjectives, and they function as disjunctive rather than conjunctive multidimensional adjectives. These facts about the ordinary meaning of these expressions undermine the descriptivist charge of conceptual inflation. We now turn to address the prescriptivist charge of conceptual inflation.

By undermining the primary descriptivist foundation, our empirical investigation reveals that it is actually the critics who make prescriptivist versions of the charge of conceptual inflation who are making revisionary claims (compare Headley Reference Headley2006; Shelby Reference Shelby2014; Hardimon Reference Hardimon2019; Urquidez Reference Urquidez2018, Reference Urquidez2020). For example, whereas ordinary usage of ‘racist’ reveals that it is a minimum-standard gradable adjective, applying to objects just in case they are racist to some degree, opponents of conceptual inflation first complain that ‘racist’ should not have such a wide extension and then recommend that the meaning of ‘racist’ should be revised so that it applies only to the most extreme examples. And while ordinary usage of ‘racist’ reveals its disjunctive multidimensionality, opponents of conceptual inflation first complain that ‘racist’ should not range over so many dimensions and then recommend that the meaning of ‘racist’ is to be revised so that either it becomes unidimensional, perhaps privileging the racist-in-attitude dimension, or that it becomes conjunctively multidimensional such that the racist-in-attitude is an indispensible criterion of application.

Indeed, if one accepts the assumption of meaning conservatism typically made by opponents of conceptual inflation, which says the term in question should keep its ordinary meaning, one should prescribe the continuing wide use of expressions condemning oppression. Insofar as they advocate for the narrow use of expressions condemning oppression over wide use, opponents of conceptual inflation are therefore making revisionary metalinguistic moves themselves, either covert metalinguistic negotiations (Plunkett and Sundell Reference Plunkett and Sundell2013) or overt metalinguistic proposals (Hansen Reference Hansen2021). In fact, opponents of conceptual inflation make two linked metalinguistic moves. First, they make the charge of conceptual inflation. Second, they seek to enact conceptual deflation, which occurs when the criteria of application for an expression become so restrictive that it loses its usefulness (compare the ‘narrow-the-scope’ proposal in Hardimon [2019] contra the meaning of ‘conceptual deflation’ in Miles [1989: ch. 3]).

Our empirical investigation also undermines a secondary normative consideration given for the prescriptivist charge of conceptual inflation. Opponents of conceptual inflation might prescribe a narrow use of an expression on the grounds that expressions with narrow meaning are generally more suitable to facilitate productive conversations compared to expressions with wide meaning. For example, if the narrow use of ‘racist’ were to be better at facilitating productive conversations about racial matters than the wider use, then that would be a reason for thinking that ‘racist’ should be used narrowly.

We think it is preferable for critics who raise the charge of conceptual inflation to admit explicitly that they are proposing a linguistic revision on normative grounds, rather than conservatively adhering to ordinary meaning because facts about ordinary meaning do not support their charge. However, even such a revisionary proposal still partly rests on an empirical assumption. For example, it is an open question whether the narrow use of ‘racist’ would in fact be better at facilitating interracial communication than the wider use. While we cannot directly answer this question here, we believe there is an indirect reason to think that the narrow use would not be better at facilitating communication. Our empirical investigation showed how expressions condemning oppression are semantically unexceptional instances of minimum-standard gradable and disjunctively multidimensional expressions. From this perspective, we can ask whether paradigmatic minimum-standard gradable adjectives, such as ‘dirty’, tend to be worse at facilitating communication than paradigmatic maximum-standard gradable adjectives such as ‘clean’; and we can also ask whether paradigmatic disjunctively multidimensional adjectives, such as ‘sick’, tend to be worse at facilitating communication than paradigmatic conjunctively multidimensional adjectives, such as ‘healthy’. Given the unproblematic everyday use of minimum-standard gradable and disjunctively multidimensional terms in ordinary language, we are skeptical that the semantic features that are characteristic of expressions with wide meaning pose any special communicative challenge. Thus, we conjecture that, given that these expressions are semantically unexceptional, the current wide uses of expressions condemning oppression do not pose any special communicative challenges either. Of course, our conjecture might turn out to be wrong, but we think the burden is now on opponents of conceptual inflation to show otherwise.

6. Conclusion

Like other theorists who have drawn evidence from linguistic corpora, we recognize that pointing out facts about ordinary language will not itself resolve normative disputes about how expressions should be used, especially expressions caught up in political struggles that make them ‘essentially contested’ (Gallie Reference Gallie1956; Harris Reference Harris1998). We do not intend to draw any substantive conclusions about the concept of racism from ordinary use directly, and we recognize that, for example, our findings will not settle the debate between those who privilege the agential dimension of racism versus those who privilege the structural dimension of racism. But we do believe that awareness of the linguistic facts can help theorists avoid making linguistic prescriptions that are unnecessary or counterproductive, given the descriptive resources present in ordinary language.

To borrow J. L. Austin's (Reference Austin1956) well-known methodological remark, while facts about ordinary language are not the ‘last word’ in philosophical disputes, they are a useful ‘first word’, and attention to the details of ordinary language can equip us with fruitful distinctions for philosophical theorizing. The first word in debates about the purported conceptual inflation of expressions condemning oppression should be the fact that ‘racist’ and similar terms have wide, nuanced uses in ordinary language insofar as they are applicable to different degrees and different dimensions of racism and other forms of oppression.