The eighteen (formerly nineteen) different cultures considered to constitute the Orang Asli (Original or Indigenous People) in Peninsular Malaysia today (fig. 1) are forging a unified identity in Malaysia as they fight for land rights and other considerations withheld from them. This process is perhaps common for small indigenous groups in nation-states when, in aggregate, they can achieve greater leverage. At the same time, as with any such synthesis, there can be lumps in the oatmeal, loci where cultural pride may inhibit blending into the larger whole. This article attempts to probe the ethnohistory of Temoq and Semelai, two ethnonyms which have been standard names for two Orang Asli groups in south-central Peninsular Malaysia.Footnote 1 In the process, two other ethnonyms, Jakun and Semaq Beri, play important but subsidiary roles in the story. In truth, this study has generated more questions than answers, but perhaps that is to be expected with such fragmentary evidence. It has demonstrated though the separateness of the ethnonyms, and their histories, from the ethnic groups themselves. A result of that separateness is that reporting on the results of this research becomes confusing since the same term represents different groupings at different times. It also suggests that the colonial administrators’ focus on language to get at race may have skewed indigenous ways of knowing themselves, fuelling a kind of social engineering by the Semelai in the use of the ethnonym Temoq.

Figure 1. Aslian languages of Peninsular Malaysia (drawn by Lee Li Kheng)

Investigating the ethnohistory of any society requires an approach from within and without. As much as possible, I have tried to understand these ethnonyms recorded in the past through insights obtained from ethnographic study of their own cultural models of ethnicity and ethnonymy. Orang Asli hold a substantial corpus of memory and knowledge of the past. This ethnohistorical inquiry is an outgrowth of ethnographic fieldwork conducted over nine extended fieldtrips since 1980, mostly with Semelai. Having originally studied archaeology, my interest in the history and evolution of the cultures on the Malay Peninsula continued into my ethnographic work with the Semelai and other Orang Asli groups. The study focused on Semelai language and cultural knowledge of forest product technology and trade. In 1987, I also spent about three weeks at Temoq and Jakun communities (Kampung Kemomol and Kampung Buluh Nipis) on the Jeram River and five days with Semaq Beri at Cahabuk in Maran, Pahang. My interest in language led me to collect and transcribe Semelai stories, as well as those of other groups, to find clues to the past and to the values and practices that distinguished these different groups from each other. In 1997, I wrote about Semelai concepts of ethnicity, primarily in relation to Malays and Temoq.Footnote 2 However, that study mostly relied on ethnographic data, and had little historical depth.

Written records can contribute to Orang Asli ethnohistories as well as link them to larger historical narratives. They can also help connect them with their land. Researching their history requires a knowledge of the ethnonyms used in written records by observers. Their names in historical sources have been filtered through early British colonial interactions with Malays, who themselves often relied on externalities, such as physical and cultural attributes for identification.

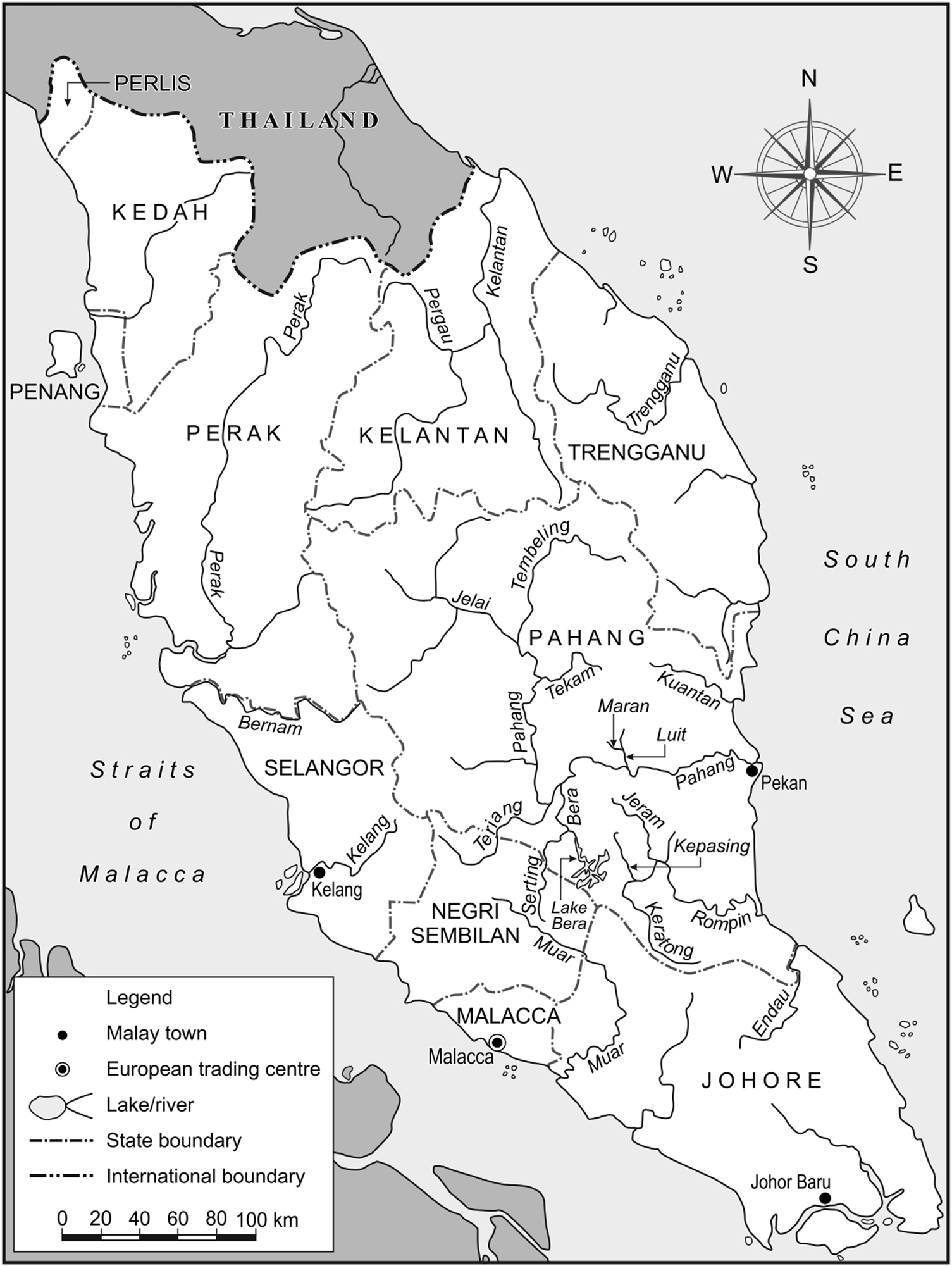

The Semelai told me themselves that ‘Semelai’ had been imposed on them in the twentieth century. But who were they before and where had they been? I became curious about the late appearance in written records of ‘Semelai’ (Sĕmilai) in 1893.Footnote 3 The few early instances of this ethnonym are centred in Pahang (see fig. 2). That inquiry, in turn, reactivated an interest in the genesis of ‘Temoq’, the ethnonym used for a very small Aslian-speaking group east of the Semelai. The term appears to derive from a Malay word for deterioration of clothing or of other materials, for example, rotten teeth.

Figure 2. British Malaya: Location map pre-1888 (drawn by Lee Li Kheng)

Ethnonyms

When people speak, the words they use, no matter how specific, simplify a reality that otherwise would be impossible to verbalise. And because the generalisations, stereotypes, and attribute clusters that constitute ethnonyms are, objectively, only partially representative of the complexities within the whole and between wholes, ethnonyms are regularly misapplied, redefined, and replaced. Nevertheless, they endure.

Ethnonyms are the names of peoples or ethnic groups thought of as wholes.Footnote 4 As imagined abstractions, they represent and define groupings perceived to have common attributes such as ancestry, culture, language, or any combination of these. Understanding ‘Temoq’ and ‘Semelai’ inevitably entails consideration of the attributes associated with those wholes, and contrasting wholes, by Temoq, Semelai, the writers, and others. A type or term that is undefined is unusable.

J.V. Wright defined ‘type’, for archaeological study of ceramics, this way:

The term ‘type’ has acquired a number of meanings, but for the purposes of this paper it is regarded as ‘a group of objects exhibiting interrelated similar features which have temporal and spatial significance’.Footnote 5 An attribute is a qualifiable and, therefore, quantifiable single feature.Footnote 6

In anthropological study, ethnonyms are ready-made types ‘exhibiting interrelated similar features’, whose attributes an anthropologist attempts to discern. This conception of ‘type’ provides room for incomplete correspondences between individual instances of a type. Not every group member will display all the attributes of a type. The attributes thought diagnostic of a type of people may differ based on perspective or false knowledge. Different people may recognise a type but emphasise some attributes while being blind to others. Types may grade into each other. Scientific typologies self-consciously aim for objectivity, but they are also susceptible to unconscious biases. Furthermore, false knowledge and bias can be major factors in writings concerned with ethnicity and race, as these are. The individual instances of each type discussed here are too few to be worth quantifying.

There are two types of ethnonyms: exonyms are created by others outside of the ethnic group, while autonyms are self-appellations. The same name though could be used for both. It is common on the Peninsula to choose a distinctive word in a language to name the group that speaks that language.Footnote 7 For example, the Semelai refer to the Temuan, their neighbours to the west, as /smaɁ bɁɲãp/ ‘the people who say /Ɂɲãp/ “no”’.Footnote 8 This is because when they overheard the language, which was unintelligible to them, what stood out was the word for ‘no’, used often and emphatically. In another Orang Asli language, Jah Hut, /jah/ means ‘person’ in that language while hut means ‘no’. Therefore, Jah Hut are also ‘the people who say “no”.’Footnote 9 Jah Hut must have originated as an exonym because a people would never have devised such a name for themselves. ‘Ja’ in Jakun may derive from the same etymon.Footnote 10 Exonyms used by dominant groups for marginalised minorities are usually superficial and/or derogatory, although subordinate groups need to label other groups seen as threats. For example, /gɔp/, which originally meant ‘outsider’ is now more commonly the word in Aslian languages for ‘Malays’. Before the twentieth century, ethnonyms in Malay for indigenous peoples were mostly based upon visible physical/racial and cultural features.

Finally, if there is nothing gained by making an ethnonymic distinction, one may not arise. If a culture is anarchic, as some Orang Asli groups have been,Footnote 11 then there may be few instances in which an ethnic label is needed. For example, Orang Asli groups often identified more with the body of water near them: Semelai at Lake Bera refer to themselves as /smaɁ tasik/Footnote 12 ‘lake people’; and /smaʔ kratoŋ/ ‘Keratong River People’ was what Semelai sometimes called another group, before Jakun became common. Also, speakers in any language might simply say ‘my people’, ‘your people’ or ‘us’. Thus, Semelai often refer to themselves as /smaʔ driʔ/ ‘my/our people’, either inclusively or exclusively.Footnote 13

Europeans, Malays, and Orang Asli

Documents concerning the indigenous peoples of the Malay Peninsula, created by chroniclers, travellers, colonial officials, and scientists, many of whom were European, used the attributes and overlapping typologies available in Malay and the author's language. Until the Malayan Emergency (1948–60), when the British colonial government began pursuing Communist insurgents hiding in the jungles, Orang Asli in south-central Malaya were rarely encountered by people who might write about them. The treacherous, difficult terrain in that area surely contributed to the dearth of information recorded for those groups until well into the twentieth century. Accordingly, the names used for those Orang Asli groups were inconsistent and general exonyms.

Theories of human nature and evolution have underlain European intellectual interest in the Orang Asli. Objectivity was an Enlightenment value, but as Sandra Manickam documents, European anthropologists wanted to find and study ‘original’ people, that is, a people who would display backward or ‘lower’ stages of human progress, in a scientific way, even though the concept itself was not scientifically valid.Footnote 14 The construction of cultural difference and attribution of value between contemporaneous societies in terms of time and progress is highly questionable. Were Orang Asli obsolete versions of humankind? The British called them ‘aborigine’, from Latin ab origine ‘from the beginning’. Orang Asli in Malay means ‘Natural or Original People’. As ‘aborigine’ came to be seen as pejorative, Orang Asli became their ethnonym in English. I will use ‘indigenous’ for the historical antecedents of today's Orang Asli.

As Manickam demonstrates, the classification of indigenous peoples by British observers in Malaya, based on attributes of their physiognomies, cultures, and languages, but laden with moral judgment, whether derived from local terminology or Western evolutionary constructs, was racist, devaluing, self-serving, and contradictory.Footnote 15 Opposing dualities such as ‘Malay–Sakai’, and attributes such as ‘original vs mixed’, ‘settled vs nomadic’, and ‘wild vs tame’, unfortunately, were saturated with ethnocentric bias, often crosscut each other, and, in each binary, simplified a spectrum of variability. Regarding contradictions, classifying indigenous peoples who had adapted to their new circumstances and moved from one mode of living, such as nomadic, to settlement, was problematic. Was an Orang Asli who had settled down and converted to Islam still an Orang Asli or now a Malay? The official definition of Orang Asli in the Aboriginal Peoples Act, 3 (2), in 1954 settled that question; they were still Orang Asli. But, in general, the types have been exceedingly difficult to use reliably in censuses or to validate in scientific studies.

Power differentials among Europeans, Malays, and Orang Asli during the colonial era further skewed written observations. A group's attempts to maintain its moral status and power often entailed drawing sharp boundaries based on unacceptable behaviours associated with neighbouring groups.

And yet, with all of those cautions in mind, I remain convinced that written records have more to contribute to Orang Asli ethnohistories.

When European colonisers came to the Peninsula, they found a fringe of mostly Malay settlements and entrepôts along the coasts, fronting a sparsely populated interior expanse of dense rainforest, swamps, and mountains. Having endured slave raiding and encroachment by Sumatrans and others, Orang Asli were embattled and traumatisedFootnote 16 and perhaps that is why, in 1837, J.H. Moor wrote, ‘They appear to practice no cruel rites, and in their manners to be altogether extremely inoffensive.’Footnote 17 Not being Muslims left Orang Asli vulnerable to slave raids until the early twentieth century; theft and appropriation of their land has continued. But many also socialised and traded with Malays, abandoned their own language for Malay, intermarried with Malays, and had children with them.

The Orang Asli

In this study, which focuses on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, ‘the ethnographic present’ will be the period prior to major deforestation in southern Pahang, eastern Negeri Sembilan and northern Johor, which began around 1960 and has varied from place to place until the present.

Orang Asli subsisted lightly on the land and mainly by some combination of hunting-gathering, forest product collecting, and agriculture. Those that practised swidden agriculture were semi-nomadic and were sometimes called jinak ‘tame’, while those that relied on hunting-gathering were more nomadic, and called liar ‘wild’, both in Malay. Orang Asli societies were kin-based, with conjugal and extended family groupings that trace their kinship ties cognatically.Footnote 18 Many Orang Asli were communal with little if any surplus production. However, others, like the Semelai, had some ascribed status differences related to political offices. These groups were more oriented toward trading with other peoples for merchandise or money. Sharing was less important for them and there were some wealth differences. However, those who became too arrogant or greedy could be accused of witchcraft. Their religions were predominantly animistic but again, using the Semelai as an example, Islamic elements were included in their beliefs as well.

According to the Department of Orang Asli Development (Jabatan Kemajuan Orang Asli, JAKOA), the Orang Asli ethnolinguistic groups together comprise less than 1 per cent of the population of Malaysia.Footnote 19 Thirteen JAKOA-recognised Orang Asli groups speak at least eighteen Aslian languages.Footnote 20 Aslian languages form a branch of the Mon-Khmer subfamily of Austroasiatic, the most ancient in situ language family in Southeast Asia.

JAKOA today divides Orang Asli very roughly into three subtypes based on physical, linguistic, and cultural features:Footnote 21 Negrito, Senoi, and Melayu Proto ‘Aboriginal Malays or Proto-Malays’.Footnote 22 Historically, the three groups were often called Semang, Sakai, and Jakun, the last two considered derogatory.Footnote 23 W.W. Skeat and C.O. Blagden,Footnote 24 following Rudolf Martin,Footnote 25 divided the Orang Asli into racial types based on their hair,Footnote 26 detailed below. Linguistically, Aslian has three sub-branches: Northern, Central, and Southern Aslian, while five Orang Asli groups speak Malay dialects.Footnote 27 I will use Semang, Senoi, and Aboriginal Malays for the three groupings.

• Semang are considered racially distinct, based on their woolly hair, short stature, and dark skin. Most have been primarily hunter-gatherers who also trade forest products for necessities that are shared. Most speak Northern Aslian languages.

• Senoi tend to have wavy hair, lighter skin and are taller and thinner than Semang. Those in the highlands practice swidden agriculture and tend to trade forest products for necessities like iron and salt. Those in more accessible areas, such as the Ceq Wong, were more dedicated traders and swidden agriculturalists. Most speak Central Aslian languages.

• Aboriginal Malays include speakers of Semelai and Temoq (Aslian languages) and Malay. These groups, historically, were also called the ‘Mixed Tribes’ or ‘Mongrel Races’ in English, and ‘Jakun’, or ‘Orang Benua’ in Malay. Having mostly straight hair, they are considered the Orang Asli most similar physically, linguistically, and culturally to Malays.Footnote 28 Some were much more dedicated to swidden agriculture than others, but forest product trade was prominent in all their economies. They also exhibited some economic and political hierarchy. They have been the Orang Asli most engaged with outsiders.

This study focuses on tracing four Aboriginal Malay ethnonyms, Jakun, Semelai, Temoq, and Semaq Beri, used today for linguistic groupings that, in written records, were not distinguished by ethnonyms until the twentieth century. Semelai live in the lowland watersheds of the Bera, Serting, Muar, and Teriang rivers in Negeri Sembilan and Pahang. Temoq are in the Jeram River valley but before the 1950s were also in the Bera and Kepasing watersheds. Semaq Beri are very wide-ranging geographically, extending over a large area in northeastern Pahang, southern Kelantan, and parts of northern Terengganu.

European colonialism and the Jakun

From 1511 until the early nineteenth century, the Portuguese and then the Dutch, in 1641, who colonised Melaka, mostly confined their interest to its immediate hinterland. To the extent that they took note of aboriginal peoples, it was those in the south, in Melaka, Negeri Sembilan, and Johor. The term (Orang) Benua, ‘Mainland People’, used in seventeenth-century Melaka, is probably the earliest recorded ethnonym for Orang Asli. Regiam de Banvás, ‘Region of Banuas’, appears on Eredia's 1613 map of Melaka.Footnote 29 A 1642 report by a Dutch colonial official, described his encounter with Bonuaes near Melaka.Footnote 30

In 1824, Great Britain acquired Melaka, while also gaining sovereignty over the remainder of the southern Peninsula. Once the British plan to develop the Peninsula was under way, those with anthropological, governmental, and/or commercial interests began making forays into the country, and information, sometimes from direct observation, began to flow. Anthropologists who were keen on finding isolated peoples thought to represent earlier stages of human evolution, shifted their focus north to the less ‘mixed’ Senoi and Semang. That pattern has remained true to the present day.

Maintaining a focus here on the southern indigenous peoples as they appear in British colonial documents, Jakun was first recorded in 1818 in a ‘Jokong’ wordlist.Footnote 31 The allogram ‘Jakong’ was recorded in 1837:

The brown savages, called the JAKONG and the BENUA, are wild races of men living in the deep forests of the interior of the Peninsula, being spread over the territories of Malacca, RumboweFootnote 32 and Johor.Footnote 33

Nineteenth-century accounts of the south seem to use Benua and Jakun in equal measure, sometimes combining them; the two were not clearly distinguished. H.D. Noone's article on the Benua Jakun language of Sungai Lenga, Ulu Muar, Johor in 1939, is the most recent use I could find of ‘Benua’.Footnote 34

Economic development also entailed significant disruption and displacement of forest-adapted groups. The colony's thirst for labour drove immigration at that time. The Aboriginal Malays were some of the most affected by labour migration and British colonial development.

Tin mines were opened and plantations of pepper and gambier were encouraged, mostly worked by immigrant labour from Indonesia, India, and China:Footnote 35 ‘[b]etween 1880 and 1957 Malaya's population multiplied fivefold from less than a million and a half to 7 ¾ millions’.Footnote 36 The people now called Semelai, living along the Muar, for example, were likely pushed upstream by the influx. According to John Cameron, the indigenous peoples of Johor and Melaka continued to move about the valleys and hills ‘but with this difference, that they have now altogether forsaken the coastline, and retreated to the fastnesses of the interior before the gradually encroaching inroads of the Malays’.Footnote 37

Linguistics and the 1911 Census

In the late nineteenth century, Blagden and P.W. Schmidt noticed similarities between many Peninsular languages and the Austroasiatic languages of Southeast Asia.Footnote 38 For comparative analysis and governmental administration, linguists and ethnologists began to standardise language names.Footnote 39 They drew from local ethnonyms such as Sakai, which in British Malaya meant many things, including ‘aborigine’ and ‘Senoi’ but also ‘slave’ and ‘subject, dependent’.Footnote 40 In the late nineteenth century, linguists adopted ‘Sakai’ as the umbrella term for what would later be called the Senoic or Central Aslian languages. In 1906, Blagden expanded Sakai's umbrella by adding a Southern Sakai language group, which included Mah Meri (Besisi) and ‘Southeastern Sakai’. The latter was recorded in the Serting and Bera valleys and was in fact the Semelai language known today.Footnote 41 However, it was considered of minor importance in the hunt for the original, ‘uncontaminated’ Jakun,Footnote 42 perhaps because Semelai culture did not fit the researchers’ expectations of purity and primitiveness. While Malays defined ‘Jakun’ as a person with mixed indigenous and Malay ancestry, R.J. Wilkinson, the British Resident in Negeri Sembilan and student of Malayan languages, chose to define Jakun as ‘aboriginal communities who inhabit the plains and lower hill country of the interior of Pahang and who have a distinct language of their own’, that is to say, their original language, for the 1911 Census of the Federated Malay States.Footnote 43 That way, the census could use language as a proxy for race.Footnote 44 R.O. Winstedt, for the 1921 Census, made the intention explicit:

This method, though offending the canons of the anthropologist in basing race on linguistics, was the only one practical, was checked by the published records of anthropologists and gave valuable results. At the same time it is too unscientific to be anything but a guide to future students of the aborigines, and there would be no point in repeating it in the present Census. … Still a racial division based on the use of five words would add nothing to the quite considerable knowledge of the aboriginal tribes which we now possess.Footnote 45

This quote demonstrates that what remained of most interest to researchers were racial categories, and that linguistic categories were considered an expedient substitute. Therefore, linguistic data were elicited by the enumerators, and ‘Semelai’ and ‘Temoq’ became documented as ethnonyms and languages. The census report said this:

there is in use among some of the Sakai a main line of definition between two different branches of the aborigines, and that line seems to follow the difference of vocal articulation. The people who have the guttural articulation (jokng for jong, etc.) are called Temok (? onomatopoeic) while the people who have not that articulation call themselves (or their language) Semelai. The Temok language appears to correspond more or less to ‘Besisi’ as shown in Mr. Wilkinson's comparative vocabularies; the Semelai appears to be the language of the tribe having its headquarters in the Bra valley and extending into the upper waters of the Rompin and the tributaries of the Pahang in this district above Kuala Lepar. The Temok speech may include that of the Malay-speaking Sakai of the plain, which has for its most characteristic sound a strangled final guttural which may be represented by K; the absence of all but a few relics of the speech of the Malay-speaking Sakai renders impossible a comparison with the (?) Besisi-speaking people.Footnote 46

Some of this information is of questionable validity. The ‘guttural articulation’ in final consonants cited here for Temoq is a prestopped nasal.Footnote 47 Both Semelai and Temoq have prestopped nasals, therefore they are not distinguishable by that feature. It is noteworthy though that the contrast implies that the Temoq language is ‘coarser’ than the Semelai language. The other information on Temoq is difficult to parse but the reference to ‘the Malay speaking-Sakai of the plain’, possibly places Temoq in the Bera-Serting or Keratong River watersheds. For ‘Semelai’, however, the geographic information is more specific, placing them in an expansive, remote, and mountainous area that stretches from the Bera area in the west to Kuala Lepar, about 130 km to the east over land the Semelai of today have never occupied. At the same time, the Semelai of the Muar, Serting and Teriang are not mentioned. The ‘Semelai’ territory described in the census better approximates the likely territory of Temoq who, based on ethnohistoric accounts, were in the Bera valley before the Semelai and who, may possibly have extended as far east as Kuala Lepar under the guise of ethnonyms such as Jakun, Orang Dalam ‘Inside People’, or Orang Bukit, ‘Hill People’.Footnote 48 My first thought was that the writer had mistakenly transposed ‘Semelai’ with ‘Temoq’. However, I.H.N. Evans’ accounts (below) gave me pause.

The 1921 Census and pre-1940 ethnographic notes on ethnonyms in south-central British Malaya

In 1914, Evans met a group on the Serting River near Bahau, Negeri Sembilan, who he identified as ‘Serting Jakun’, and whose language he characterised as ‘essentially similar to that of the mixed peoples of S. Pahang’.Footnote 49 He continued,

The Serting people are called by the Malays either ‘Orang Bukit,’ a very general name for aboriginal tribes, or Sakai Semlai (or Semleh). The latter name refers to their language, which for some undiscoverable reason, is called Semlai. According to their own account, they call themselves Bekturk Chong, which has exactly the same meaning as the Malay Orang Bukit, i.e. Hill People.Footnote 50

Orang Bukit, ‘Hill People’, is not generally descriptive of Semelai, who live in lowland swamps. According to Nicole Kruspe,

[Evans] claimed that the people refer to themselves as Berkturk Chong, which he erroneously translated as the equivalent of Orang Bukit ‘Hill People’. ‘Berkturk’ (obviously /bktǝk/) is recorded as the entry for ‘person’ in the accompanying word list. It in fact means ‘weeds or undergrowth’. Bktǝk ‘undergrowth’ is possibly a pun on the Malay word semak [sǝmaɁ] ‘undergrowth, scrub’, a homonym with smaɁ [sǝmaɁ] the Semelai word for ‘person’.Footnote 51

That passage by itself reveals how confusing it can be to tease apart the different groups and their ethnonyms in historical sources. Based on Kruspe's analysis, we can dispense with Orang Bukit. The Serting people were not saying that they call themselves ‘Hill People’; they were joking. But why?

Evans appeared unfamiliar with the term Semlai and did not mention ‘Southeastern Sakai’. He wrote that Malays called this Serting group Sakai Semlai, implying that the people themselves did not, making it an exonym. Were the Serting people unfamiliar with the name? That is unlikely. Or did they dislike it, perhaps associating it with another group?

In 1917, Evans met people on the Tekam river he called ‘Bera Sakai-Jakun’, and ‘The Bera Tribe’.Footnote 52 They had traded for their wooden blowpipes, made by a ‘tribe’ on the Luit River near Lubok Paku, roughly 45 km northeast of the Bera River. He did not identify the people at Tekam as Semelai but because they were a Bera group who had traded for their wooden blowpipes, they were probably the people we today call Semelai. Evans also met Jakun at Barop and Gading,Footnote 53 on the lower Rompin River who told him that their blowpipes had been ‘made by the wild tribe—the Orang Semlai—which lives at some distance from the Rompin River and towards its source, occupying, I suppose, part at any rate of the country between the Rompin and the Pahang’.Footnote 54

In a footnote, Evans explained

‘Orang Semlai’ is a term frequently applied by tribes who speak Malay as their mother-tongue to those who speak Sakai dialects. From what I could learn of these people from the Rompin Jakun, I believe them [Semlai] to be a Sakai-speaking tribe, of mixed blood, probably with Proto-Malay (Jakun) characters predominating.Footnote 55

In these passages, Orang Semlai, a people who speak an Aslian language, are placed in a mountainous region east of Lake Bera and south of the Pahang River, a geographic range overlapping that described for Semelai in the 1911 Census. Furthermore, Jakun characterise them as ‘the wild tribe’, which is an unlikely characterisation of the Semelai I have known.

The ethnonym ‘Semelai’ /smlay/ has been hypothesised to derive from *slaay, an ancient Mon-Khmer etymon that gave rise to the Jah Hut word slay ~ hlay for ‘swidden’.Footnote 56 Infixation of agentive <m> in the Jah Hut word could hypothetically produce s<m>lay [səməlay], ‘those who make swiddens’.Footnote 57 It seems though that the term ‘Semelai’ had not long been attached to the swiddening people now called Semelai.Footnote 58 It also seems that the earlier eastern ‘Semelai’ were, at least, not dedicated swiddeners. ‘Swidden’ in Semelai is /dʔoh/, and one person mentioned that the Temoq called the Semelai /smaʔ dʔoh/ ‘swiddening people’. Semelai sometimes use that term for themselves as well.

Whereas the blowpipes in the remainder of the Peninsula were made of bamboo, among some indigenous groups in southern and eastern Pahang blowpipes had a very different technology.Footnote 59 They consisted of a cylinder of very hard wood split in half. Each half was carefully grooved so that once reunited, they formed a tube with a diameter that could fit the butt of a dart. The cylinder was tightly wrapped in Calamus sp. rattan that was split and shaved. The rattan is coated with Palaquium obovatum latex. The mouthpiece was usually made of gutta percha (Palaquium gutta). Wooden blowpipes were sought after by groups that did not manufacture them; they lasted much longer than those made of bamboo. They were also considered an essential attribute of the ‘original Jakun’ by Wilkinson and others.Footnote 60

The 1921 Census elicited more information about indigenous groups in the Pekan District of Pahang.

Few or no ‘Jakun’ were found. These people, of whom there are very few in Pekan district—perhaps not fifty all told—are so rarely seen that not even the Sakai of Kepasing in Keratong can tell their whereabouts. They fly at the slightest suspicion of strangers, have no houses, and are far more like wild beasts than human beings.

The vast majority of those enumerated spoke Malay-[…]

A Jakun vocabulary was obtained from a Sakai at Kepasing, whose mother was a Jakun—(it was very difficult to find any one [sic] who knew even a few words) […]

Only at Kepasing could I find anyone acquainted with the language of the ‘Orang Bukit’ (as these Sakai call them) or Jakun. My informant was a young man whose mother was of this race, and he supplied me with the words given in the list appended. The Keratong Sakai say they see these Orang Bukit very rarely indeed, and fear them very much. Occasionally a few will come in for salt.

The blow pipe is universally in use in the Keratong, and consists of a penaqa tube closely and neatly bound with a strip of rattam [sic] from end to end.Footnote 61

This Census’ use of ‘Jakun’ appears to follow Wilkinson's redefinition, that is, Proto-Malays who speak their own language. That explains why they could not find many Jakun. In contrast, ‘Sakai’ here appears to mean ‘Malay-speaking indigenous peoples’. The Kepasing Sakai man with a Jakun mother was therefore a Malay-speaking indigenous person whose mother spoke an Aslian language, which, based on the rough wordlist in J.E. Kempe's diaries,Footnote 62 is likely Temoq. ‘Orang Bukit’ here is used by the Keratong people, making it an exonym. Was it also an autonym? In this Census, neither Semelai nor Temoq were mentioned, which is probably because, as exonyms, neither would have been used to self-identify.

Sakai-Jakun as an anthropological type

Wilkinson eventually decided that Southeastern Sakai was the Jakun language after all and that it extended across the entire range of people classified, by his definition, as Jakun.Footnote 63 Today, Jakun are Orang Asli in Pahang and Johor who are defined as people of mixed descent who speak Malay, the opposite of Wilkinson's definition.

Evans mostly used ‘Jakun’ to refer to indigenous people who appear to be physically and culturally of mixed descent with Malays, usually reserving Sakai-Jakun for Jakun who spoke a Sakai (Aslian) ‘language’. In 1920, he classified the Bera tribe, as well as the Krau (present-day Jah Hut) and the Tekam and Kemaman River tribes (present-day Semaq Beri), as ‘Sakai-Jakun’.Footnote 64 He labelled the Serting people ‘Jakun’ but added ‘Sakai Semlai’, which established them as Aslian speakers. Even though consisting of Malay words, Sakai-Jakun was not a Malay term. Also, Sakai-Jakun was not what those groups called themselves.

The 1940s and after: Ethnographic notes on ethnonyms in south-central British Malaya

H.D. Collings, Curator of Anthropology at the Raffles Museum in Singapore, conducted ethnographic fieldwork at Lake Bera, and the Bera and Jeram Rivers in 1940 and 1947. The remainder of this study draws mainly upon Collings, Hood Mohamad Salleh,Footnote 65 and my own work.

Semelai

There is no known record of Semelai as an ethnonym or language before the late nineteenth century. Semelai said that they had come to the Serting and Bera valleys from the west.Footnote 66 (In fact, they said they began their journey in Pagar Ruyong, Sumatra.Footnote 67) The Semelai claim to western origins is also supported by monetary terms in Semelai that possibly date to Portuguese Melaka in the sixteenth century.Footnote 68 This group having moved inland makes sense given the population increases in British Malaya during the nineteenth century noted earlier.

In 1940, when Collings first visited Lake Bera, he called the non-Temoq there Semelai. The Lake Bera Semelai in 1982 claimed, to me, that they felt they were having an unfamiliar exonym imposed on them. They even began calling him ‘Tuan Semelai’. One Semelai consultant told me,

This name [Semelai] was not known by the Semelai until /twɒn kuleŋ/ (H.D. Collings) started calling them that. Before, they had always been called /smaʔ darat/ [Land People]. People in fact tended to be called by the name of the place they were from, e.g., /smaʔ tasik/ [Lake People], /smaʔ braʔ/ [Bera River People], /smaʔ sərteŋ/ ‘Serting River People’.Footnote 69

Another Semelai elder confirmed her claim, saying that ‘The British used “Semelai”.’ However, 25 years earlier, this ethnonym, Semelai, had been used by Malays at Serting to label them. It had also been used to label people living at Lake Bera and east of it. How could they not recognise it? A third elder, in fact, disputed the notion and said that ‘Semelai’ had existed before Collings’ arrival. However, this man had moved to Lake Bera from the east, the Mentenang River, and was not originally of this group. All three agreed that the Semelai called themselves /smaʔ darat/ ‘Land People’. The third added that Temoq were also called /smaɁ darat/.Footnote 70 But /smaʔ darat/ is generic, similar in meaning to Orang Asli. It is used in contrast with non-Orang Asli. When a Semelai man told me that his father was Chinese, he used /smaʔ darat/ for his mother who was Semelai. Malays at Kuala Bera called Semelai orang darat.Footnote 71 Does this mean that there was no term defining the Semelai as a separate indigenous people with their own language?

Semaq Beri/Semoq Beri

Another Orang Asli group, officially labelled Semaq Beri by JAKOA, are a large, heterogeneous ethnolinguistic grouping in northeastern Pahang, southern Kelantan and Terengganu, whose language is closely related to Semelai and Temoq.Footnote 72 According to Rodney Needham, in the 1950s, some northern Semaq Beri groups called themselves, and were called by local Batek (a Semang group), ‘Semelai’.Footnote 73 However, Nicole Kruspe, in a recent study, found no accounts of the use, by Semaq Beri, of Semelai as an autonym.Footnote 74 In 1987, a Semaq Beri at Cahabuk told me that they call themselves and other Semaq Beri along the Maran, along other streams that flow into the lower Pahang River from the north, and along the Kuantan River, /smaʔ b-ktəʔ/ [səmaʔ bəkətəʔ]. They called the Semaq Beri at the headwaters of the Tembeling River /tãrɛ̃ʔ/.

These groups practice hunting and gathering but also trade forest products for goods beyond the bare necessities that more communal Orang Asli tend to seek. Few historical records mention these Semaq Beri groups. It is not known whether these northern Semelai are related to the Semelai, historical or current, to their south.

Temoq

The present-day Semelai have used /tmoʔ/ to refer to a group, now numbering fewer than 100 people, some of whom lived in the Lake Bera area before the Semelai, remaining there until the Emergency. Their settlements are now primarily along the Jeram River. The Semelai also call them /smaʔ bri/, ‘Forest People’, but it is /tmoʔ/, as Temoq, that has been institutionalised by researchers and government officials.

There were other groups called /tmoʔ/ around Lake Bera that no longer exist. According to one consultant, Temoq at the headwaters of the Bera River, east of Lake Bera, were called /tmoʔ-smlay/, because they spoke both languages, and /tmoʔ brumun/.Footnote 75 On the western side of the lake, there were /tmoʔ kas/ or /khas/,Footnote 76 who he described as /lyar btol/ ‘truly wild’. They could speak a little Semelai but had a language of their own.

Based on oral history, the Aslian-speaking Temoq had been primarily hunter-gatherers and forest product traders. In 1940, there were still some nomadic groups on the Kepasing, a Rompin river tributary between Lake Bera and the Jeram, but in the early twentieth century they began practising some swidden cultivation.Footnote 77 The Semelai admired the Temoq as exceptional hunters of dangerous animals such as elephants, rhinoceros, and tigers; Lake Bera Semelais never hunted these animals; elephants and rhinoceros did not come near the lake because it was so marshy. Temoq ate wild yams they dug in the forest, which most Semelai hardly could recognise. Among six or seven Temoq, one or two had a jungle knife, I was told. Temoq made and used wooden blowpipes, called /blahan/, and spears to hunt, mostly monkeys and gibbons, which they ate or traded to Semelais. They ate much more meat and much less starch than Semelai did, which made their bodies strong and healthy. Semelai only knew how to make bamboo blowpipes, so Temoq traded wooden blowpipes to them in exchange for starchy tubers, iron implements, tobacco, and small quantities of salt. Semelai complained to me that Temoq frequently stole tubers from their swiddens. One story I heard several times was of a Temoq man, trespassing in a swidden, who was speared by a spring trap set for a sambhur deer; even though Semelais performed a shamanic healing ritual, the man died.

Semelai said that Temoq did not eat salt, implying that they preferred not to eat it. However, a Temoq elder told me that, before and during the Second World War, they had difficulty getting salt, because they feared slave raiders and the Japanese. Many suffered from goiters. They got less than a handful of salt from the Semelai in exchange for a blowpiped monkey.

Semelai jargon for ‘Temoq’ was /smaɁ ʔen cŋnɛŋ/ ‘the people in between swidden and forest’. Such transitional ecotones are good places to find game. Temoq often camped near Semelai settlements. Members of the two groups socialised, sometimes married. Temoq, unlike the Semelai, do not practice circumcision.Footnote 78 Temoq attended Semelai wakes; Temoq did not have funerary rites, compelled as they were by fear to abandon their dead at their campsites. But Temoq shamans, called /puyɒŋ bri/ ‘forest shamans’, were considered more powerful than Semelai shamans, called /puyɒŋ dʔoh/ ‘swidden shamans’. This duality also echoes the /smaʔ bri/ - /smaʔ dʔoh/ duality mentioned earlier.

After the Malayan Emergency began in 1948, Temoq who refused British colonial government regroupment withdrew to the Jeram River, while those who remained at Pos Iskandar assimilated and became Semelai. Hoe Ban Seng in his 1964 ethnographic report on the Semelai does not mention the Temoq.Footnote 79 Hood, based on his ethnographic fieldwork with the Semelai at Lake Bera in 1972–73, wrote, ‘In the whole of my investigations among them, Semelai made no significant reference to the Temoq, indeed as a group the latter was a non-entity’.Footnote 80 He concluded that the Temoq must have assimilated.Footnote 81

Review of the evidence thus far

At this juncture, a review of the evidence presented, and its possible implications, will help frame the next sections.

• ‘Semelai’ has been thought to derive from a Mon-Khmer etymon, *slaay, meaning ‘swidden’. With an <m> infix it could become *s<m>lay ‘swiddeners’.

• A swiddening ethnolinguistic group came to the Bera-Serting watershed from the west. It is the furthest east they have lived.

• The Serting people were called Semelai by Malays, but neither the Serting nor the Bera people (at Tekam) self-identified as Semelai. At Lake Bera in the 1980s, I was told that, before Collings, they were unfamiliar with the name ‘Semelai’.

• The 1911 Census stated that the Semelai (from the Bera valley extending east into the upper Rompin and Pahang tributaries above Kuala Lepar) ‘call themselves (or their language) Semelai’. The Rompin Jakun situated the ‘wild tribe’ ‘Semlai’ between the source of the Rompin River and the Pahang River, a mountainous and remote area. Therefore, both sources place ‘Semlai’ in the upper Rompin and its tributaries. Temoq, on the Jeram River, which flows into the upper Rompin, are of that area. However, in the 1921 Census, neither Semelai nor Temoq were mentioned, confirming their status as exonyms.

• The Bera-Serting people would not have been described as ‘the wild tribe’. They were dedicated agriculturalists who saw the Temoq and other nomads as inferior. ‘Wild tribe’ suggests that the upper Rompin Semelai were hunter-gatherers, which would not support the etymological reconstruction of ‘Semelai’ as ‘swiddeners’, but would not disqualify it either.

• Both the Rompin Jakun and the Bahau Malays used Semlai to mean ‘Sakai (Aslian) speakers’, accurate for both Semelai and Temoq. But the Semlai of the upper Rompin made wooden blowpipes, while the Serting Semlai did not.

• Temoq made wooden blowpipes and lived in the upper Rompin. The Bera-Serting Semelai traded with Temoq for wooden blowpipes.

In summary, there is a disjuncture between the location and characteristics of people called ‘Semelai’ in the early twentieth century and from 1940 on. The blowpipe makers called Orang Semlai or Semelai were later called Temoq, Semaq Beri, or Jakun. Before 1940, the Serting-Bera people did not self-identify as Semelai.

Orang Asli ethnonyms and the Department of Orang Asli Affairs

After the Malayan Emergency began in 1948, with Communist insurgents taking refuge in jungle near Orang Asli communities, the colonial government began to pay more attention to Orang Asli. In 1953, the Department of Aborigines was given more responsibilities. Among other things, it systematised, administratively, ethnonyms for the different indigenous groups. Stories, perhaps apocryphal, tell of colonial officers creating a group's name for them. Administrators and others appear to have made conscious efforts to avoid derogatory ethnonyms and often chose names derived from the group's own language. A pattern developed of Orang Asli groups becoming known by ethnonyms that are neutrally descriptive in their language. For example, Orang Hutan ‘Forest People’ in Malay is a generic descriptor that may be used for any land-based Orang Asli, whatever language they speak. However, the equivalent of Orang Hutan in a group's own language can be a distinctive ethnonym for the group. Therefore, the earliest record I could find of Semoq Beri for this group was from 1952 in An Introduction to the Malayan Aborigines, by P.D.R. Williams-Hunt, head of the Department of Aborigines.Footnote 82 The ethnonym Mah Meri appears to be another attempt to use the people's own term for ‘forest people’, even though Mah is an inaccurate rendering of /hmaʔ/ ‘person’ in their language.Footnote 83

Temoq as an ethnonym

According to Collings,

For some reason, the name Tĕmoq always amuses the Semelai and embarrasses the Tĕmoq. Perhaps this is because it is associated with their way of life, or it has some unpleasing meaning. In the speech of the Sisiq of Selangor and of the Che Wông of Běnom in Pahang, the word means a gibbon ape.Footnote 84

In this section, I will attempt to identify the source of this ethnonym that visibly embarrasses the people it names. The concept of ‘Temoq’ was already established before Collings began his ethnographic study in 1940. After its mention in the 1911 Census, Paul Schebesta, in 1926, surveying the known ‘jungle tribes’, included ‘the Tĕmo’’, whom he characterised as Negritos living in the headwaters of the Bera River in Pahang, but this was hearsay.Footnote 85 Temoq is an exonym that emphasises negatively perceived features of race, language, and culture. While /smaʔ bri/, ‘forest people’, provides a respectful counterbalance to /tmoʔ/, outsiders generally have not known of it.

What is the etymology of the ethnonym /tmoʔ/?

The Semelai and Temoq word in question, /tmoʔ/, consists of a /t/ followed by a neutral vowel ([ǝ] schwa), which is non-phonemic (that is, does not distinguish words from each other in that language).Footnote 86 ‘ĕ’ for ‘ə’ was common in the spelling of Malay words. However, in the New Rumi Spelling reform of 1972, ‘ĕ’ in written Malay was replaced by ‘e’. The problem with ‘e’ is that, in Malay, it could also represent /e/, a phonemic vowel, a vowel that is used to distinguish words from each other.

/t/, /m/, /o/, and /ʔ/ (glottal stop) in Semelai are all phonemes. However, for the purposes of this analysis of /tmoʔ/, there is one caveat. In Semelai, vowels that follow nasal stops are usually non-phonemically nasalised.Footnote 87 For example, the word /khmur/ for ‘caterpillar’ is pronounced phonetically as [khəmũr] and the word /kmɔŋ/ ‘all gone’, is pronounced [kəmɔ̃ŋ]. (Non-phonemic [ǝ], are left out of phonemic transcriptions.) The nasalisation of the phonemic oral vowel in each case is not phonemic; it is an artefact of the nasal stop it follows. However, if a nasal stop is followed by an oral vowel, that indicates that there had been an intervocalic cluster of a homorganic nasal plus voiced stop that was reduced to the nasal.Footnote 88 That voiced stop was dropped leaving a nasal stop followed by an oral vowel. The many instances of this phenomenon I have recorded are all in Malay loanwords.Footnote 89 For example,

• The /ɛ/ in Semelai /lmɛŋ/ ‘spear’, from Malay lembing, is not nasalised.

• The /e/ in Semelai /sneɁ/ ‘joint’, from Malay sendi, is not nasalised.

• The second /o/ in /ponoŋ/ ‘hut’, from Malay pondong, is not nasalised.

The /o/ in Semelai /tmoɁ/ is an oral vowel, even though it follows a nasal stop; that indicates that there had been a homorganic voiced stop /b/ between the /m/ and the /o/. Therefore, the precursor of /tmoʔ/ was /tmboʔ/ [tǝmboɁ].

Table 1 (below) comparing the words for ‘gibbon’ in four different southern aboriginal groupsFootnote 90 elucidates Collings’ quote above. Blagden, at the time, was using an orthography that contrasted ‘ĕ’ with ‘e’. However, the words have an /e/ or /i/ after the /t/, not the non-phonemic [ĕ] or [ə] following the /t/ in Semelai /tmoɁ/. In fact, the horizontal line over the ‘e’ and ‘i’ in two of them seems to emphasise their phonemic status. The only question mark is the ‘b’ in Southern Sakai (Mah Meri) ‘tembo’’, which causes that word to appear to derive from Malay tembok [təmboʔ]. However, the ‘b’ is a postploded nasal; the word's phonemic representation is /tɛmɔʔ/.Footnote 91

Table 1. ‘Gibbon’ in four southern aboriginal languages

Note: The macron indicates vowel length.

Source: Skeat and Blagden, The pagan races, vol. 2, p. 407.

Therefore, Semelai /tmoʔ/ is not phonologically equivalent to the words for gibbon and unlikely to have been derived from them. That /tmoɁ/ sounds like the word for gibbon in those languages may though have contributed to the insult if those language speakers were in contact with Semelai and Temoq speakers.

Is /tmoɁ/ a Mon-Khmer word?

In Shorto's comparative Mon-Khmer dictionary, *t2mɔɁ, for ‘stone’, and, in one case, ‘hill’, is the closest etymon to Semelai /tmoɁ/:

146 *t2mɔɁ stone.

A: (Mon, Khmer, Katuic, Bahnaric, Palaungic, Khasi, Aslian) Old Mon tmo’ /tmɔɁ/

stone, rock, hill, Modern Mon mɔɁ stone, rock, Old Khmer t(h)mo, Modern Khmer

thmɔ:, Kuy tmau, Halang mo:, Palaung mo, Khasi maw, Che’ Wong tǝmɔɁ, Jah

Hut tǝmɔ:Ɂ stone; from a suffixed form Semaq Beri tǝmɔŋ stone; (probably) ~

Stieng tǝmɒ:u, Chrau tǝmo:, Bahnar tǝmɔ: (→ Jeh tamou?), Praok simaw,

Lawa Bo Luang samɒuɁ, Lawa Umphai, Mae Sariang samoɁ stone. Footnote 92

However, to derive /tmoɁ/ from t2mɔɁ would not account for the oral vowel after the /m/. Because of the phenomenon described above, the precursor to /tmoʔ/ must be /tmboʔ/ [təmboʔ]. If we look to Austronesian Malay as a possible source for the etymon, we find tembok [təmboʔ], which means ‘perforated; holed; rotten or hollow (of teeth); worm-eaten (of planking); eaten through by white ants; corroded by rust’.Footnote 93 Is this the source of /tmoʔ/? We need to know more about its ethnographic context to gauge the likelihood.

Tapping into derision

Collings described what he saw as the effect jelutong (Dyera costulata) tapping had on Temoq men in 1947:

Nowadays some of the Tĕmoq wear Chinese, Malay and European clothes got as a result of the jelutong trade which is largely carried on by making the tappers clothes conscious and results in a lot of unhealthy, ragged and usually filthy clothes which are quite unfitted to be worn in wet equatorial forests.Footnote 94

Jelutong trees grew wild in lowland areas where Semelai and Temoq lived. Beginning in the nineteenth century, jelutong latex was used for ‘goods where elasticity was not a prime consideration’.Footnote 95 Once the British began cultivating Brazilian rubber trees in Malaya in 1877, the market for jelutong disappeared. But in 1922 researchers discovered that jelutong latex could partially replace chicle in chewing gum,Footnote 96 and tapping began anew.

According to my interviews, Semelai guided Chinese jelutong tappers in the forest. Semelai did not tap jelutong themselves because they lacked access to coagulants. In contrast, Collings reports that Temoq in 1947 were tapping the trees themselves; he even notes how much they were paid for the latex.Footnote 97 He also mentions that Temoq ‘used to steal the belongings of the men who went tapping the jĕlutong trees’.Footnote 98 That statement may explain how they obtained the coagulants the Semelais lacked.

While Collings noted that Temoq had hereditary headmanship (a batin), he described a startling order given by the Semelai batin to the Temoq:

There is also a possibility that the Sĕmĕlai have some kind of overlordship, as the late Sĕmĕlai Batin Sidin of Tasek Běra, … is said to have ordered the Tĕmoq to give up their own tongue and to speak Semelai only.Footnote 99

The Tĕmoq of the Jeram who have obeyed Batin Sidin's order to give up their old speech have not suffered any loss of their self-respect, whereas these living further down the river who have come in contact with Malays and the jĕlutong trade are already degenerated. They cringe, call themselves ‘poor Sakai’, and before strangers, they are ashamed of their bodies. Their food growing has also suffered and it is not an uncommon thing to hear aboriginal women complaining that jelutong tapping so interferes with food growing that, in spite of having money and clothes, they often go short of food.Footnote 100

There seems to be more going on here than simply two peoples who speak different languages. It appears that as long as the Temoq spoke their language and remained nomadic while living in proximity to Semelai, they would be treated as a subordinate and dependent caste.

The extent to which Collings’ characterisations of Temoq jelutong tappers may have been influenced by his Semelai consultants remains unclear. But while Collings described Temoq clothing as filthy and ragged, his photographs reveal little difference between Semelai and Temoq in their dress: some from each group wear traditional loincloths while others wear sarongs or shorts obtained through trade. Describing Temoq who avoided downstream commerce as having self-respect, he seems to view Temoq ‘degeneration’ as circumstantial, that, like many indigenous groups, Temoq are vulnerable to exploitation and moral debasement from regular contact with Malays and other cultures.

It is noteworthy though that the Semelai viewed Temoq as degenerating because of their language, which they scorned. This Semelai solution to Temoq social problems demonstrates the great pride the Semelai take in being Semelai. They believed that conversion to Semelai culture would save Temoq from demoralisation from poverty and the condescending attitudes of Malays and other outsiders. Semelais may also have wanted to distinguish themselves from these ‘others who are almost the same’ to gain the favour of outsiders such as Collings. Much like Malays who have viewed Orang Asli as inferior, Semelai have viewed the Temoq as inferior, perhaps even as a subordinate class within Semelai society.

Temoq sensu lato

According to JAKOA administrators and to researchers, Temoq are the people who speak Temoq. However, Semelai often expand the meaning of /tmoʔ/ to include any nomadic hunter-gatherer group. It is not clear what language the /tmoʔ khas/ spoke, although one consultant said that they are the Malay-speaking Orang Asli who now live at Kampung Bukit Serok, on the Keratong.Footnote 101 Sometimes, Semelai today refer to Jakun, who border the Semelai and Temoq on the south and east, as /tmoʔ/. For example, a Serting River Semelai told me,

His father was a Jakun, Temoq lah, on the side of the Keratong River … at [Kampung] Bukit Serok. Now they say Jakun, but really Temoq. Like Tamils their women. … Temoq /srupaʔ/ ‘equals’ Jakun.Footnote 102

‘Temoq equals Jakun’ equates the two, making it unlikely that Bukit Serok people are a fusion of two groups although there may have been many marriages between the two. ‘Now they say Jakun’, reaffirms the non-use of Jakun in the past. The Keratong River flows into the upper Rompin River near the Jeram and Lake Bera. While Temoq, administratively speaking, are a tiny group in the Jeram valley, this quote expands the ethnonym to include Malay-speakers, now called Jakun, living in a much broader area of Pahang and Johor. Given the Semelai assumption that those now called Jakun once spoke Aslian languages, in that frame, it makes sense to see them as Temoq. The quote gives Temoq a racial dimension as well. Darker people are more likely to be called Temoq. Some of Collings’ photographs of Temoq were labelled according to a racial typology albeit one that did not include skin colour.Footnote 103

The Semelai also applied /tmoʔ/ to themselves at times. If a Semelai did something uncouth, for example, like spitting betel juice onto a ladder rung instead of between the rungs, they risked being called /tmoʔ/, an effective means of social control and boundary maintenance.

When I visited the Temoq on the Jeram River in 1987, they did not voice sensitivity toward use of Temoq. Perhaps they were resigned to outsiders using that term. My impressions of the settlement were these: I did not notice anything amiss or degenerate in people's behaviour. They were kind and helpful, answering my questions patiently. The kampung was clean and orderly. Shamanic rituals were conducted almost every night. They had not tapped jelutong for fifteen years. Tapping of Dipterocarpus spp. oleoresin and rattan collection were ongoing enterprises, much as in Semelai communities.

In 2022, I discussed Collings’ portrayal of the Temoq with a Semelai consultant about 55 years old. He said that Collings could be right about the effect of jelutong tapping on the Temoq men, but that the issues went beyond that. According to my interviewee: The Temoq stole crops, lied, didn't want to work, wanted easy money, were always in debt, were unreliable, would agree to meet at a certain time but then would not appear, were dirty and unpresentable, and would sell sexual access to their wives to Chinese and Malay men. When I pointed out that Semelais have exhibited these behaviours as well, he agreed, but argued that Semelais behaved that way much, much less often. At the end of our discussion, he added that circumstances are different today and that Orang Asli identities have become more integrated, lessening differences among cultural groupings. All Orang Asli today are hardworking, he concluded.

This last point was confirmed in an interview I did in 1998 with an elderly consultant. He said that, in the past, Temoq had been at Lake Bera but now there were none left. When I asked where they went, he said they went up to the Keratong River. They were not in this area anymore. ‘They are good at school nowadays. Temoq children are [working] up at Gombak [Hospital].Footnote 104 They are good writers and are paid salaries by the government.’ When asked if any Semelai at Lake Bera had Temoq ancestry, he said there were some: ‘Those who made Temoq pregnant. People in the distant past. There are Temoq who married us. Like that.’

‘Temoq’ from ‘Tembok’

The analysis of /tmoʔ/ above hypothesised that a Semelai loanword from Malay [tǝmboɁ] for rotten, holey, and deteriorated, regarding clothing or appearance,Footnote 105 had lost the /b/, creating [təmoɁ] /tmoʔ/. The meaning in Malay accords with Collings’ description of the Temoq jelutong tappers’ clothing. As mentioned above, in the Semelai wordlist from 1914, the phonological shift is not evidenced. However, Hood's transcription of the ‘Myth of I Tembeling’ (see below) includes both versions.Footnote 106 Also, in my 1987 Temoq fieldnotes, I had written that ‘[tǝmboɁ] was the old version of Temoq’. It may be that this phonological change was so recent that the variants were still in flux. However, it is more likely an instance of co-existence of /tmoʔ/ and /tmboʔ/ in Temoq. Finally, when I recently asked the Semelai consultant above about the likelihood of /tmoʔ/ deriving from Malay tembok, he enthusiastically agreed. By contrast, ‘stone, rock’ the meaning associated with the Mon-Khmer etymon *t2mɔɁ in some Aslian languages, has little salience for the Semelai relative to Temoq.

Semelai and Temoq

Another reason to reject *t2mɔɁ as the source of Semelai /tmoɁ/ is the negative connotation placed on the latter. Semelais use /tmoɁ/ when they are joking or speaking derisively. There is more meaning embedded in that word than simple topography. When speaking respectfully, Semelai say /smaɁ bri/ ‘forest people’. In Semelai, /tmoɁ/ and /smaɁ bri/ denote the same group but carry different moral evaluations. That today so few people identify themselves as Temoq may well be related to its derogatory connotations. However, relations between Semelai and Temoq were often positive, as described earlier. In fact, two Semelai elders suggested that Semelai and Temoq were the same people. A Semelai man, Sahat Sipin, recounted an oral history of the initial migration of Semelais into Lake Bera; he specifically cited the Temoq for recommending that Semelais move upstream into the lake where the fishing was so much better than in the Bera and Serting Rivers.Footnote 107

The interrelationship between Semelai and Temoq is the focus of a Semelai origin story about a man who had a pet tiger.Footnote 108 In Collings’ version, Tĕmĕling is the tiger; in the version I recorded, the man was named /tmbleŋ/ [tǝmbǝleŋ].Footnote 109 One day the tiger licked the blood from a leech bite on the man's leg. The tiger liked the taste and proceeded to eat its owner and everyone in the settlement, except for two girls who hid inside a drum. One day two brothers came along. (In the version Collings recorded, the brothers are called Tĕmoq; in Hood's version they are called both Temoq and Tembok;Footnote 110 in Epen's version, which I recorded, the brothers are called /smaʔ bri/ and /tmoʔ/.Footnote 111) They found the girls, who told the brothers about the tiger. The men hid and then stabbed the tiger to death with their spears as it tried to leap through the door. Then the girls married the brothers. Epen concluded by saying, ‘that is why the Semelai male line is Temoq, and the female line is Semelai.’ In Collings’ version, one couple had a girl, the other a boy, ‘and it is from them that the Sĕmĕlai are sprung’. Both versions claim a dual ancestry for Semelais. It is difficult to see the story as anything other than a Semelai affirmation of their Temoq heritage, and a positive one at that: the Temoq brothers are completely respectable and heroic. The story relies on the well-known bravery of Temoq hunters. In Epen's version, the brothers are first identified as /smaʔ bri/ and then as /tmoʔ/ thereby recognising these two ethnonyms as representing one and the same people.

Conclusion

Ethnographic research combined with close reading of historical texts can provide additional insight into the past and present of groups living today. This study has attempted to trace how the ethnonymic landscape relative to Orang Asli groups in the south-central lowlands of the Malay Peninsula changed during the colonial and post-colonial periods and how much that is related to active shaping by European anthropologists, linguists, and government officials but also by the Orang Asli themselves. The four ethnonyms in this study were all imposed on the ethnic groups that carry them, with mixed results. ‘Temoq’ was imposed on that group by Semelai but then taken up by colonial functionaries and researchers. Wilkinson's emphasis on language in the 1911 Census furthered scholarly recognition of the different ethnolinguistic groups in that very inaccessible region of Pahang. Whether or not that has been helpful to different Orang Asli groups remains to be seen. Eventually, ‘Jakun’ became the administrative ethnonym for Malay-speaking Orang Asli in Johor and southeastern Pahang. These groups may have distinctive and interesting cultures but, perhaps because they speak Malay, they have received little attention.

I have suggested that Temoq and Semaq Beri language speakers, if called Semelai, may have been widespread in the south-central lowlands before today's Semelai arrived. It was noted that Semelai had been the exonym of a northeastern Pahang group, now called Semaq Beri. But if the Semaq Beri and the Temoq are the people formerly called Semelai, a highly speculative assertion, who are the people now called Semelai? And how did that name come to label them? Was it just an error compounded by the British colonial administration? The /smaʔ bri/ ‘forest people’ – /smaʔ dʔoh/ ‘swiddening people’ duality mentioned earlier could bear further investigation.

Is it possible that Malays and others extended ‘Semelai’ to this newly arrived group from the west because they were speaking an Aslian language similar to the Aslian spoken by people already there? Perhaps the Serting Jakun then turned around and relabelled the ‘original Semelai’ ‘Temoq’ to achieve identity separation from them. That would explain why the Serting Jakun seemed unwilling to own ‘Semelai’. It is also possible that Semelai were annoyed by the emphasis placed by the British colonial administration on labelling indigenous groups based on language. Nowadays though, Semelai call themselves Semelai quite freely.

I have argued that Temoq is an ethnonym in the Semelai language, from a borrowed Malay word that describes a tattered and dissolute appearance. It became the vehicle for expressing negative stereotypes Semelai harbour about Temoq people and for differentiating themselves from a people to whom they attributed a lower status. Temoq, an exonym, seems more oriented to a negative evaluation of a way of life than an actual linguistically distinct group.

The confusion surrounding Semelai, Temoq, Jakun, and Semaq Beri, has been recognised for some time now.Footnote 112 The outsiders who have reified these terms have not necessarily been aware of the different dimensions of their meanings in different languages. Semelai /smaʔ bri/ as the flip side of /tmoʔ/ adds to the confusion, but perhaps that is to be expected; natural language is complicated.

Given the negative associations of Temoq, will it continue to be used? JAKOA has de-institutionalised it. Replacing Temoq with another name would be another ethnonym imposition, however respectful the intent. But as alluded to above, one reason there are so few Temoq may be because of the negative stereotypes. Many Temoq may have already decided to abandon or refuse it. The Semaq Beri are known to be a heterogeneous amalgam of groups. It is also possible that with greater recognition among Orang Asli of their commonalities rather than their differences, the term Temoq is becoming less pejorative. The future is hard to predict.