Introduction

In the wake of the Great Recession, redistribution has become an increasingly polarizing issue. Fiscal conservatives advocate austerity and a roll-back of the welfare state, while others want the government to reduce economic inequalities. Yet to fully understand the depth of this social conflict, it is not enough to simply observe that citizens hold opposing opinions. As research on social and affective polarization makes clear (e.g. Iyengar and Westwood, Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Mason, Reference Mason2013), it is equally important to realize just how morally charged the conflict between those on either side of the redistributive fault-line is. One manifestation of this would be the attribution of negative motives to those either favouring or opposing redistribution.

We therefore argue that to better our understanding of the moral politics of the welfare state, we must go beyond a focus on preferences and investigate what we term motive attribution: that is, how people answer the question “what drives others to take the positions that they hold?” We do so using ten original survey questions designed to assess how respondents evaluate other citizens’ redistributive preferences. Do they think wanting more redistribution is an expression of self-interest, altruism, jealousy, beliefs in fairness, or laziness? Do they see opposition to redistribution as an expression of concern for the economy, status maintenance, or dislike of the poor?

By examining the motives citizens ascribe to their pro- and anti-redistribution compatriots, we aim to provide new insights into welfare state attitudes and debates. As we argue below, existing research on the moralism surrounding redistributive and social policy preferences is surprisingly narrow in focus, with a longstanding concentration on fairness norms and deservingness perceptions, in particular vis-à-vis the poor (e.g. Sahar, Reference Sahar2014; van Oorschot, Reference Van Oorschot2000). Thus, although moralistic attitudes have been shown to have a variety of important consequences – ranging from greater political engagement to increased hostility and intolerance (e.g. Ryan, Reference Ryan2014; Reference Ryan2017; Skitka et al., Reference Skitka, Washburn and Carsel2015) – our understanding of the topic is exceedingly one-dimensional.

Studying motive attributions offers a valuable route to widening this understanding. Key here is the shift in the subject of moralistic attitudes: while past work has almost exclusively focused on perceptions of welfare state beneficiaries (e.g. Jensen and Petersen, Reference Jensen and Petersen2017; van Oorschot, Reference Van Oorschot2000), we take a much broader focus, aiming to uncover what citizens think of those who hold a given stance toward the welfare state. Doing so has the potential to help us better understand not only social animosity, but also social policy preferences. On the one hand, research on social polarization (e.g. Mason, Reference Mason2015, Reference Mason2016) suggests that motive attributions are likely to both reflect and structure the way that individuals relate to people whose preferences differ from their own; from this perspective, negative motive attributions could be considered a manifestation of social polarization with the potential to further entrench animosity. On the other, social relations are themselves a potentially important factor shaping preferences (e.g. Green et al., Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002): one’s thoughts about the sorts of people who take pro- and anti-welfare state positions likely combine with self-conceptions to help shape opinions; and the more negative motive attributions are, the less likely individuals may be to shift their own positions.

There are thus good reasons to think that motive attributions should matter as both an independent and dependent variable. The focus of this first look at the concept, however, is necessarily narrow. Taking our cue from the extensive body of research debating the effects of social policy design on public opinion (cf. Arts and Gelissen, Reference Arts and Gelissen2001; Jæger, Reference Jæger2009; Kevins, Reference Kevins2017; Laenen, Reference Laenen2018), this article homes in on the potential role of welfare state regimes (see Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Scruggs and Allan, Reference Scruggs and Allan2008) in shaping motive attributions. To conduct this investigation, we rely on data from original, nationally representative surveys that we fielded in 10 Western democracies – Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States – to a total of over 12 000 respondents.

The analysis of these data is guided by two questions: to what extent are motive attributions stable across diverse contexts; and to what extent do differences in motive attributions reflect welfare state types? Our major findings are twofold. First, there is substantial variation across the different motives: respondents generally ascribe more benign motives to those favouring redistribution and more negative ones to those opposing it. Second, there is sizeable cross-country variation, but that variation does not map neatly onto welfare state regime clusters. Notwithstanding some evidence of universalist regime effects vis-à-vis certain motives, our overall findings are suggestive of sizeable cross-national variation in the mix of motive attributions, both within and across welfare regimes.

The concept of motive attribution and the empirical results we present add to a burgeoning literature on welfare state attitudes. Given the potential impact of these preferences on social policy outcomes (see Jensen, Reference Jensen2007; Soroka and Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010), the guiding questions of this vast body of research have so far been “Who wants what, and why?” (e.g. Blekesaune, Reference Blekesaune2012; Jensen, Reference Jensen2014; Kearns et al., Reference Kearns, Bailey, Gannon, Livingston and Leyland2014; Kevins et al., Reference Kevins, Horn, Jensen and van Kersbergen2019). Adding to these literatures, we hope to demonstrate that motive attribution is an important – and, until now, overlooked – dimension of cross-country variation that future research ought to consider.

The concept of motive attribution

While motive attribution is a new and distinct concept, we take our point of departure from the related welfare state literature on the causal attributions of poverty (e.g. Sahar, Reference Sahar2014; Zucker and Weiner, Reference Zucker and Weiner1993). The best example of this approach is found in work on deservingness, which focuses on the causal attributions from which moral evaluations of responsibility are drawn (e.g. Jensen and Petersen, Reference Jensen and Petersen2017; van Oorschot, Reference Van Oorschot2006): in other words, what do citizens believe causes poverty, and how do these beliefs affect social policy preferences? In this research, the focus is on perceptions of welfare recipients, who may or may not be seen as responsible for their lot in life. Studies in this vein typically distinguish between three types of attributed causes of poverty: individual (i.e. the poor are to blame for their condition); structural (i.e. something in society, such as the structure of the economy, causes poverty); and fate (i.e. misfortune is at fault) (see Sahar, Reference Sahar2014). On the whole, recipients are deemed less deserving of support if the need for help is thought to be caused by a lack of effort on their part rather than by something beyond their control. In brief, citizens attribute certain positive and negative qualities to benefit recipients and this, in turn, informs politically relevant moral evaluations of deservingness.

Our focus, however, is not narrowly on perceptions of welfare recipients, but rather extends to anyone with redistributive preferences (be they pro- or anti-). We agree with the implicit assumption in the deservingness literature that normative assessments of recipients can have important political consequences – unemployment benefit cuts, for instance, seem more likely if the jobless are viewed as undeserving (e.g. van Oorschot, Reference Van Oorschot2000). Yet, benefit recipients are not the only individuals subject to these sorts of evaluations; indeed, normative assessments surrounding the welfare state are likely to be quite an extensive phenomenon (e.g. Rowlingson and Connor, Reference Rowlingson and Connor2011). Redistribution is at its core about conflict: some who have little make a claim on others who have a lot (or at least somewhat) more. The fairness of the implied redistribution has been intensely debated (see Jensen and van Kersbergen, Reference Jensen and van Kersbergen2017) and it is plausible that such conflict colours assessments of other citizens as well.

There are several reasons to believe that investigating the mix of intentions ascribed to those holding pro- or anti-redistribution stances will provide insights that could not simply be gleaned by examining attitudes toward redistribution. First, recent research suggests that social polarization and issue polarization may, in fact, be relatively distinct phenomena (e.g. Mason, Reference Mason2013, Reference Mason2016). From this perspective, partisan and ideological identities may, under certain circumstances, lead citizens to “grow increasingly politically rancorous and uncivil in their interactions, even in the presence of comparatively moderate issue positions” (Mason, Reference Mason2015: 129). As a consequence, at both the individual- and country-level, it seems likely that redistributive preferences may obscure variation in the level of animosity and affective polarization (see Iyengar and Westwood, Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012).

Second and relatedly, while welfare state politics have long been recognized to have a strong moral dimension (e.g. Curchin, Reference Curchin2015; Moon, Reference Moon and Gutmann1988; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein1998; Rowlingson and Connor, Reference Rowlingson and Connor2011), the study of moralism underlying social policy preferences has had a surprisingly narrow focus. As highlighted above, most such work focuses on deservingness perceptions and fairness norms (e.g. Larsen, Reference Larsen2008b; Isaksson and Lindskog, Reference Isaksson and Lindskog2009; Sahar, Reference Sahar2014), and almost always in relation to the poor. This is a considerable shortcoming, in particular since moralism itself is likely to bring about its own set of effects, both positive (e.g. greater political involvement) and negative (e.g. greater intolerance) in nature (e.g. Ryan, Reference Ryan2014, Reference Ryan2017; Skitka et al., Reference Skitka, Bauman and Sargis2005). As Ryan (Reference Ryan2014: 380) argues, “[m]orally convicted attitudes are special because they seem to engage a distinctive mode of processing: they powerfully arouse certain negative emotions, engender hostile opinions, and inspire punitive action.” Examining the mix of intentions assigned to pro- and anti-redistribution individuals thus provides an opportunity to explore the degree to which moral conviction and hostility pervade these debates in the minds of citizens. Doing so cross-nationally, in turn, allows us to investigate whether and to what extent these patterns vary by country.

In embarking on this study, we define motive attribution as an individual’s attribution of (underlying) motives to the preferences of others. In this initial presentation of the concept, we suggest four categories of motive attribution, all of which are ascribable to both pro- and anti-redistributive preferences: other-regarding motives, fairness beliefs, self-interest, and personality defects. We consider the first two motive categories to be relatively benign, whereas the latter two – and especially personality defects – may indicate greater animosity. Note that while we do not lay out an exhaustive list of potential motives in this paper, the motive attributions discussed here provide a first cut at investigating the topic and categorizing the underlying components.

Addressing our four categories in turn, other-regarding motives entail a concern with other citizens, whether directly or indirectly. A person may, for instance, favour redistribution out of a desire to help the poor, but not herself; or she may oppose redistribution based on the belief that it will keep the economy strong, in the process benefiting everyone in society. In highlighting a concern for others, this is clearly a more charitable form of motive attribution. With similar connotations, fairness beliefs refer to abstract notions of what is right (just) and wrong (unjust). Crucially, with both of these motive categories, an individual’s pro- or anti-redistributive preference is not attributed to personal gain, but rather to broader concerns related to the well-being of other individuals and/or society as a whole.

Our remaining two categories have decreasingly benign connotations. Self-interest points to an explicit and tangible benefit behind favouring or opposing redistribution. Note that the personal benefits in question do not necessarily have to be monetary, as they may also extend to improvements in social status more broadly; rather, the key factor is that personal gains and losses are perceived to be central, as attributing pro- or anti-redistributive preferences to self-interest implies that these stances are the result of rationalistic personal utility calculations. In other words, these preferences are assumed to at least partly reflect the living conditions of an individual (e.g. they are poor/rich and would like to be better off/hold on to what they have).

Personality defects, in turn, refer to arbitrary or idiosyncratic shortcomings that characterize individual persons, and are clearly the most negative of the motive attributions we investigate. For example, an individual might be thought to favour redistribution due to laziness (i.e. he or she is simply too lazy to work harder, or perhaps even to work at all) or to oppose it out of a simple dislike of the poor. To be sure, such motives are almost certainly often wrapped up with self-interest: the imagined lazy pro-redistribution individual would likely be perceived to be heavily driven by self-interest. Yet perceived personality defects seem less likely than pure self-interest to be explained away with reference to external circumstances or rationality, and as a consequence they are potentially the harshest, most hostile form of motive attribution.

There are many reasons why the mix of attributed motives are liable to vary across countries, ranging from political discourse to real-life differences in actually-existing motives. Here we home in on one potential factor that has been the subject of particular attention in the social policy literature: welfare state institutions. Indeed, a long line of research suggests that social policy design may shape popular opinion (e.g. Ellingsæter et al., Reference Ellingsæter, Kitterød and Lyngstadm2017; Jordan, Reference Jordan2013; Kevins, Reference Kevins2017). Larsen and Dejgaard (Reference Larsen and Dejgaard2013), for example, argue that the universal welfare model, as found in Scandinavia, creates a sense of social affinity within the population; this, in turn, leads to a less negative representation in public discourse of welfare recipients than is typically found in liberal welfare states. Much of this effect is likely tied to the universal welfare state’s most characteristic feature: in designing programmes that benefit everyone in society, rather than simply targeting those with the greatest need, universalist institutions pursue a “simple egalitarian strategy” rather than a “Robin Hood” one (see Korpi and Palme, Reference Korpi and Palme1998: 671). The result is less arguing about redistribution, targeting, and neediness thresholds, and more of a focus on debating how we should develop “our” collective welfare state (e.g. Jacques and Noël, Reference Jacques and Noël2018; Larsen, Reference Larsen2008a).

Yet the existence of welfare regime effects cannot be taken for granted, especially as another strand of the literature has called into question the relevance of welfare types for popular opinion (e.g. Arts and Gelissen, Reference Arts and Gelissen2001; Jæger, Reference Jæger2009). It is also unclear whether institutional types can help us to understand motive attributions in Continental and Southern European welfare states: both of these systems stress the delivery of benefits along corporatist lines, with occupation and employment history typically determining entitlement (e.g. Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Ferrera, Reference Ferrera1996); and the difference between them is often conceptualized as one of degree, with Southern European welfare states exhibiting higher fragmentation, placing greater emphasis on employment history, and giving a central support role to the family unit (see Kevins, Reference Kevins2017; Naldini, Reference Naldini2003; van Kersbergen, Reference Van Kersbergen1995). We thus might expect these welfare states to foment a compartmentalized variant of solidarity rather than a universal one (e.g. Rothstein and Stolle, Reference Rothstein, Stolle, Hooghe and Stolle2003) – but the Continental and Southern European institutions are clearly of less a priori relevance than either of our two other welfare state types.

Based on existing work, then, one would expect that the key regime-related distinction here should be between universalist Scandinavia and the selectivist/liberal Anglo countries (see Korpi and Palme, Reference Korpi and Palme1998; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein1998; van Oorschot, Reference Van Oorschot2000), with the mix of motive attributions in corporatist and Southern European welfare states likely falling in between these two extremes. Our expectations can thus be summarized with three hypotheses: universalist welfare states will be associated with a generally more benign set of motive attributions; liberal welfare states will exhibit a more negative set; and motive attributions in Continental and Southern European will be more mixed than in either the liberal or universalist countries.

To be clear, with only ten countries in our dataset we are unable to draw any definitive conclusions about the causal relationships underlying various mixes of motive attributions – in particular given that a variety of contextual factors are likely to matter. Instead, our goal here is to conduct an investigatory probe centred around two questions: to what extent are motive attributions stable across diverse contexts; and to what extent do differences in motive attributions reflect welfare state types?

Data

To explore patterns of motive attribution, we fielded identical surveys in 2016 within Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, the UK, and the US. The countries were first and foremost chosen to maximize variation in terms of welfare regimes (see Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Ferrera, Reference Ferrera1996): the UK and the US represent the so-called residual, liberal regime type; Denmark, Norway, and Sweden represent the universal, social-democratic type; France, Germany, and the Netherlands represent the Continental type; and Italy and Spain represent the Southern European type.

The number of respondents per country ranges from 1200 (in the US) to 1214 (in Sweden), with 12 050 respondents in total (Appendix Table 1 provides a full breakdown of respondents by country). The surveys were fielded by YouGov, a commercial polling company. Using their online panels, respondents were quota-sampled to achieve representativeness in terms of gender, age, geographical region (defined according to the European Union’s NUTS 2 classification of regions), and education; i.e. the conventional set of socio-demographic background variables upon which most surveys aim to obtain representativeness. Research (in fact, directly examining YouGov) indicates that carefully conducted online surveys yield virtually identical total survey error and coefficient estimates to traditional telephone and mail interviews (Ansolabehere and Schaffner, Reference Ansolabehere and Schaffner2014). As a consequence, we can feel reasonably confident about the quality of the data employed in the analysis.

Our surveys included ten questions meant to assess potential motive attributions. The first five relate to motive attributions for pro-redistributive preferences, while the last five address motive attributions for anti-redistributive preferences. In each instance, respondents were asked to state their degree of agreement with each of the five motives on an 11-point scale running from “definitely not” to “maybe” to “definitely.” The first battery of items reads:

Some people want to redistribute wealth from the rich to the poor. Why do you think people support such redistribution? Is it…

1. To help themselves

2. To help the poor, but not themselves

3. Because they are jealous of the rich

4. Because they believe it is fair

5. Because they are lazy

Reflecting the four categories laid out above, items 1 and 3 can both be tied to self-interest: the first asks directly if people desire redistribution in order to help themselves, whereas the third concerns their desired status (i.e. they want to be rich too). Item 2 is meant to capture other-regarding motives (helping the poor), while item 4 has a similarly benign focus on fairness concerns. Finally, item 5 captures belief that a personality defect (i.e. laziness) drives those favouring redistribution.

Respondents were then asked to repeat the procedure, this time with regard to anti-redistribution motives:

Similarly, some people don’t want to redistribute wealth from the rich to the poor. Why do you think people are against redistribution? Is it…

1. To help themselves

2. To keep the economy strong

3. To protect their lifestyle and status

4. Because they believe it is fair

5. Because they just don’t like the poor

As with the former question battery: items 1 and 3 are meant to broadly capture self-interest; item 2 assesses other-regarding motives; item 4 turns to a belief in fairness; and item 5 looks at ascribed personality defect (i.e. brute dislike of the poor).

Two points are worth noting at this juncture. First, all ten questions ask respondents to attribute motives to people who do or do not “want to redistribute wealth from the rich to the poor.” This stylized framing thus prompts respondents to think solely about individuals falling into pro- and anti-redistribution camps; although this is practical for a first investigation of the topic, the wording nevertheless leads us to gloss over differences in degrees of support for redistribution – or, indeed, preferences for different types of redistribution. Second, the survey items include several attributable motives that are, by necessity, tied explicitly and exclusively to the rich or the poor (e.g. favouring/opposing redistribution “to help themselves”). While it would otherwise be impossible to consider the perceived role of self-interest, the downside of this approach is that we risk priming respondents in such a way that they think only of the poor and the rich even when reflecting upon other potential pro- and anti-redistribution motives. We return to each of these points in the conclusion.

Methods

The remainder of the paper lays out the empirical patterns present in the data – with all reported analyses incorporating design weights, so as to reflect the underlying country populations as closely as possible. We begin by first examining patterns in the overall sample, before then breaking responses down by country. Our goal here is to highlight differences across the motive attributions, as well as cross-country patterns in their variations. As these analyses are purely bivariate, however, we run the risk of identifying country effects that are driven only by compositional differences (i.e. that variation in individual-level characteristics is driving country-level differences). We therefore conclude the investigation by using entropy balancingFootnote 1 alongside standard ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions to adjust for inter-sample variation.Footnote 2 This allows us to mitigate potential confounders and ensure the robustness of our findings.

While most of the presented analysis is straightforward, our approach to controlling for inter-sample variation requires a more detailed description, in particular as it entailed two distinct steps. First, we began by generating entropy balancing weights relative to a consistent baseline country, Norway – chosen for its common position at the extremes of the motive attribution distributions. In creating these weights, we took into account survey design weights as well as a variety of individual-level variables that might potentially explain variations in motive attributions: gender; age bracket; religiosity; trade union membership; employment status; self-placement on the income decile spectrum; self-placement on the ideological spectrum; and having government benefits constitute the primary source of one’s income. Second, the resultant nine sets of generated entropy weights (one per country-pair) were applied to the survey respondents in OLS regressions examining the effect of “treatment” – that is, living in a given country context relative to our baseline (Norway) – for each of the ten motive attributions. The findings of this analysis thus effectively adjust for differences in the mean, variance, and skew of our control variables across our cases – in the process helping us to ensure that our bivariate results reflect country-level contextual factors rather than individual-level variation.

Analysis

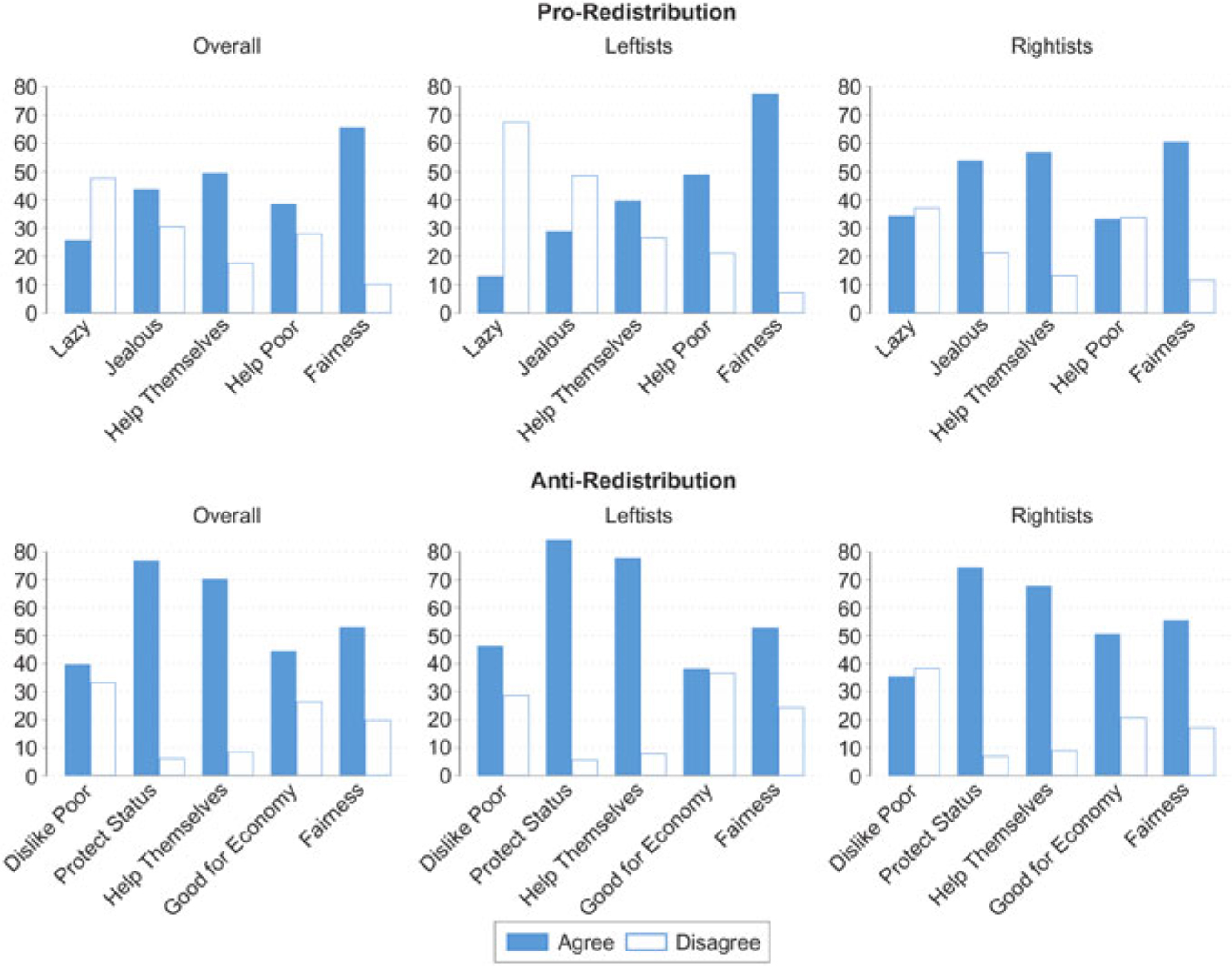

We begin by presenting the general distribution of motive attributions. Figure 1 plots the percentage of respondents who agree or disagree with the five potential motives for pro-redistribution (top panels) and anti-redistribution (bottom panels) stances. In doing so, it illustrates the overall distributions (left-most panels) as well as those among leftists (centre panels) and rightists (right-most panels), given the potential relevance of ideology for motive attributions. For these descriptive figures, respondents are: (1) coded as leftist if they placed their ideology between 0 and 4 on an 11-point scale, and rightist if they placed it between 6 and 10; and (2) coded as disagreeing with a motive attribution if they selected 0–4 on the 11-point agreement scale, and agreeing with it if they selected 6–10. To make it easier to visualize the distributions, we exclude the percentage that selected the middle category (5) for each motive attribution – though of course the totals always sum to 100 (consult Appendix Table 2 for additional descriptive statistics). In illustrating these results, we lay out the distribution of responses such that reading a given panel from left to right takes us from broadly negative motive attributions to more benign ones.

FIGURE 1. Attributed motives for pro-and anti-redistributive preferences, percentage share overall and on the left and right.

Turning first to the pro-redistribution motives, we see a general trend toward ascribing relatively charitable motivations to those who support redistribution. Moving from left to right on the x-axes, we find that the proportion agreeing that a motive applies broadly increases, while the proportion disagreeing generally decreases. For the sample as a whole, the largest contrast is found on opposing ends of the figure: on the left-most point of the x-axis, we see that only 26 percent of the sample agrees that people support redistribution due to laziness, and 48 percent disagree; while on the right-most point, we note that 66 percent of respondents agree that people support redistribution out of fairness concerns. Yet, the trend is not unambiguous. Respondents – especially rightists – are relatively uninclined to ascribe the “help the poor” motive, and conservatives are more likely to suggest that laziness, jealousy, and self-interest motivate pro-redistribution citizens.

Turning to the bottom panels of Figure 1, we find a strikingly different pattern of motive attributions when it comes to anti-redistribution preferences. On average, respondents appear less positively disposed toward those who oppose redistribution, with more negative motives far more commonly ascribed than benign ones – a pattern that is present, remarkably, among both leftist and rightist respondents. Within the overall sample, 77 percent of respondents agree that people oppose redistribution to protect their own status, and 70 percent believe they do so to help themselves. Similarly, the proportion of respondents assigning the fairness motive is substantially lower (53 percent) than was found with regard to pro-redistribution motives (66 percent). The only motive that bucks the trend is “dislike the poor”, which generated the lowest level of agreement within this item set. This is, admittedly, a very negative, almost aggressive statement; as such, it is probably most surprising that 40 percent of respondents affirmed that it was a relevant motive.

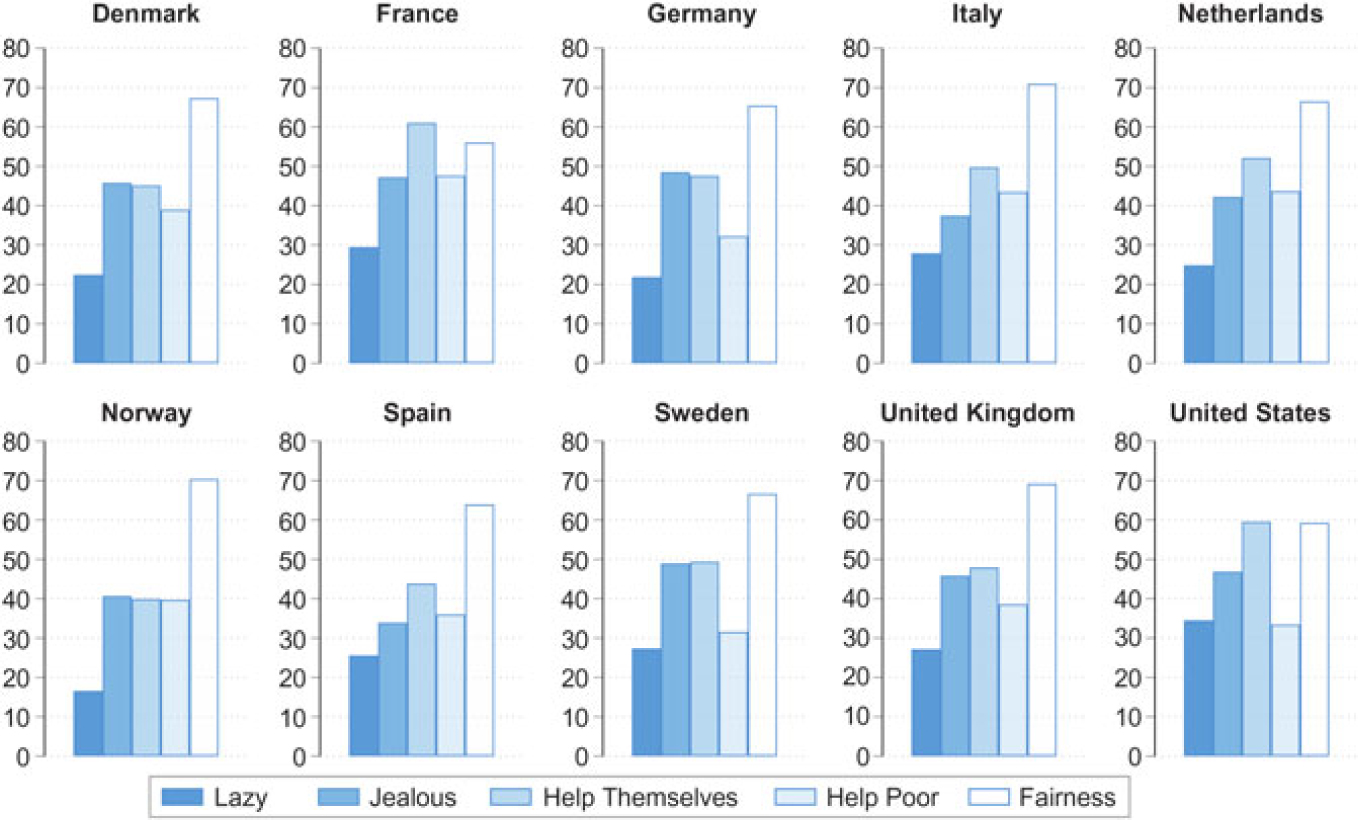

Our next step in the investigation is to examine whether there is any meaningful cross-country variation in the mix of motive attributions. How universal are the overall trends uncovered thus far? Figure 2 provides a first indication of the packages of ascribed motives for pro-redistribution stances across the countries, illustrating by-country agreement per motive for each sample. (We exclude the percentage in disagreement here for ease of visualization.) While the graphs provide a general overview of the data, ultimately pointing to considerable cross-country variation, several overarching observations seem especially noteworthy.

FIGURE 2. Attributed motives for pro-redistributive preferences, percentage share of agreement by country.

First, it is in the US and France – two countries with markedly different welfare regimes – that citizens appear most inclined to ascribe less benign motives to those who favour redistribution: most notably, respondents from these countries were the most likely to agree that people support redistribution because they are lazy or to help themselves. Norwegians and Danes, by contrast, were repeatedly among the least likely to agree with these statements. Yet there is no similar pattern with regard to “jealousy”, as all but the Southern European countries are clustered in the 40 percent range (specifically, between 41 and 49 percent). Second, despite an overall tendency toward more benign motives, “help the poor” is rather unpopular across the entire set of countries. Strikingly, agreement is at its lowest in Sweden (32 percent), which sits alongside Germany and the US, while it is at its highest in France (48 percent). Finally, we find that a majority of respondents in all countries believe that people support redistribution out of fairness concerns; here again, however, it is noteworthy that respondents in the US and France are the most sceptical about the motives of those with pro-redistributive preferences. Figure 2 thus paints a picture of substantial differences between the motive attributions of respondents living in the US and (more surprisingly) France, on the one hand, and those living in Scandinavia (though not Sweden) on the other. Yet, this pattern holds only when it comes to the somewhat more hostile motive attributions: that people support redistribution to help themselves or because they are lazy. Attributions of jealousy, by contrast, are relatively consistent across the cases.

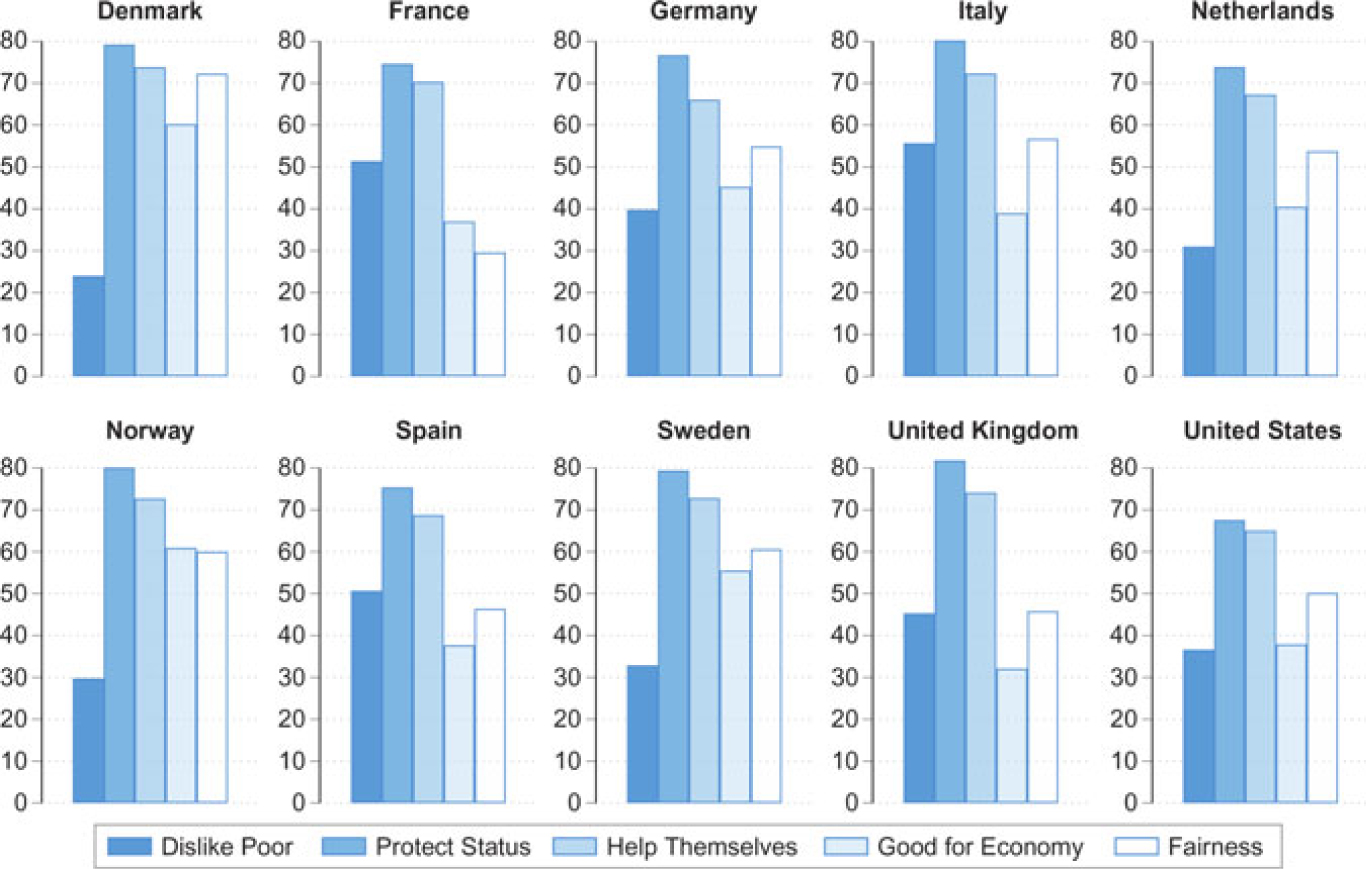

Figure 3 repeats the above exercise, but for the motives thought to drive anti-redistribution preferences. Findings suggest that the less benign motivations of “protect status” and “help themselves” are incredibly popular across all of the cases, with agreement between 70 and 80 percent in most countries. Only the US stands at all apart on these items – but even there about two-thirds of respondents agreed that these motives were applicable. Cross-country variation grows substantially, however, when it comes to what is arguably the most hostile motive, “dislike the poor”; over half of the Spanish, French, and Italian samples felt this motivation was attributable to those holding anti-redistribution stances, compared to less than a third of Scandinavian and Dutch respondents. Variation on the charitable “keep the economy strong” motive is of a similar magnitude, though here it is the Scandinavian populations that are most in agreement: a majority of Norwegians, Danes, and Swedes agreed this motive applied, while agreement in the Anglo, Southern European, and French samples was situated in the thirty-percent range. Rounding out the results, we find an even more exaggerated version of this pattern for our other benign motive, “fairness”. Agreement on this item ranges from 72 percent in Denmark to a mere 30 percent in France.

FIGURE 3. Attributed motives for anti-redistributive preferences, percentage share of agreement by country.

Viewing Figures 2 and 3 in combination reveals some interesting cross-country patterns. In Denmark and Norway, neither those wanting redistribution nor those opposing it are thought of in overly negative terms – yet Swedes tend to be more sceptical toward those with pro-redistribution stances. A similar, though less pronounced, picture emerged for Germany and the Netherlands. American and French respondents, by contrast, tend to assign comparatively negative motivations to those on either side of the redistribution question, while Britons do so only with regard to anti-redistribution motives. Finally, Southern Europeans are relatively more likely to ascribe less benign motives to those opposing redistribution, and less likely to ascribe them to those favouring it.

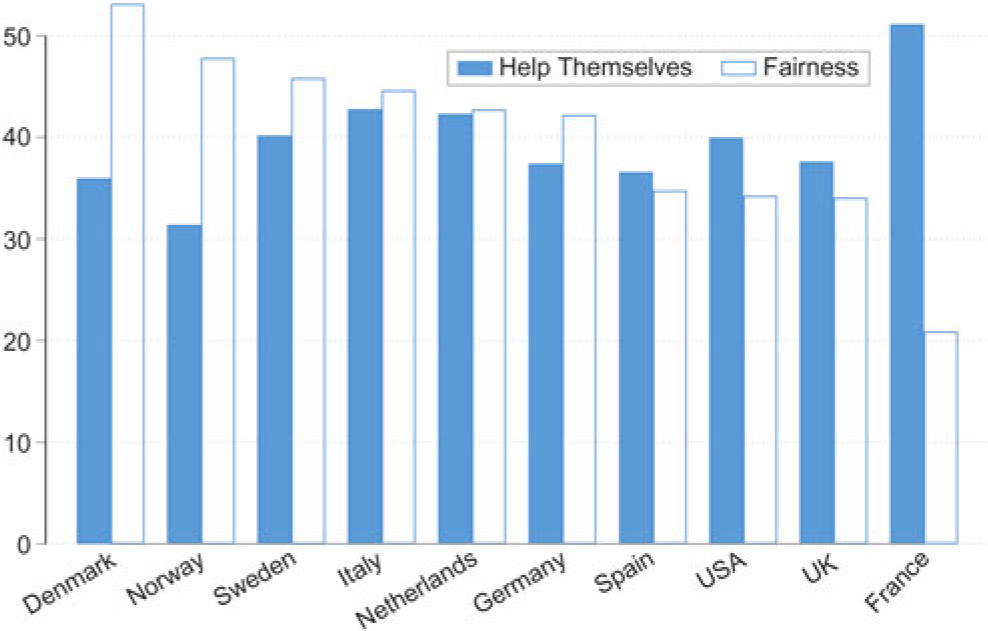

Another way to compare the mix of attributed motives across countries is to calculate how large a proportion of respondents applied the same motive – whether negative or benign – to those holding pro- and anti-redistribution stances. In the case of the more charitable motives, such a duality might be interpreted as a sign of a less hostile environment, while applying a negative motive to both sides might indicate greater scepticism and cynicism. Limiting ourselves to the motives that are precisely comparable, Figure 4 reports the percentage of respondents agreeing that those on both sides of the redistribution debate were motivated by a desire to help themselves or out of fairness concerns. Countries are ordered based on the percentage of their populations that agreed that “fairness” motivated both pro- and anti-redistribution individuals.

FIGURE 4. Respondents assigning the same motive to those holding pro- and anti-redistribution stances, percentage share by country.

The findings are telling. Turning first to the fairness motive, the Scandinavian populations appear to live up to the consensual expectations present in some strands of the welfare state literature: 53 percent of Danes thought that fairness motivated those on both sides of the redistribution debate, as did 48 percent of Norwegians and 46 percent of Swedes. That percentage drops to just under 35 percent in the UK, the US, and Spain – and to a mere 21 percent in France. In the mirror image of these results, French respondents were by far most likely to agree that both sides are motivated by a desire to help themselves (51 percent). Norway and Denmark, in turn, are the two countries where this was least likely to be the case (31 and 36 percent respectively), followed closely by Spain and Germany (both at 37 percent). Overall, these results thus seem to reflect a broader divide between a more consensual Scandinavian cluster and a more conflictual Anglo and French one. In keeping with our observations above, however, Sweden occupies a rather more ambiguous, middling position – most notably when it comes to negative motives.

It is possible, however, that the cross-country variation highlighted so far simply reflects compositional differences in the samples. The demography of the countries in our sample is not identical; it is well-known, for example, that the proportion of elderly persons is higher in Italy than in the US. Similarly, Scandinavians are both more secularized and unionized than the populations of Southern Europe and the US. If we want to ensure that our uncovered patterns are not simply artefacts of compositional differences across the cases, we need a more robust way to test country variation.

To that end, Figure 5 presents the findings from the OLS regression analyses incorporating entropy balancing weights.Footnote 3 The columns list the motives, once again roughly moving from more negative (on the left) to charitable (on the right), while the countries are separated into their respective welfare state types. Regression coefficients are plotted with 95% confidence intervals and indicate country effects on agreement with a given motive attribution (recall that answers are on an 11-point scale); for example, a score of positive two for a given country-motive pair – as with Italy and the dislike the poor motive – suggests that respondents living in that country agree that that motive is important at a level two points higher than respondents in Norway (accounting for survey design weights and controlling for compositional differences across the countries).

FIGURE 5. Balanced cross-country differences (relative to Norway) in motive attributions.

Several observations can be drawn from this analysis. First, the findings do indeed broadly reflect those described above: country effects are strongest for the motives that exhibited a greater range of cross-country variation. We can therefore say with greater confidence that these differences are not simply the result of underlying compositional differences across the samples, whether connected to basic demographics, labour-market status, or even ideological leanings. Second, the largest country effects – both for pro- and anti-redistribution preferences – are typically found in the US, Southern Europe, and France. The other Continental countries tend to nevertheless exhibit only modest differences from Norway, whereas Denmark and, to a lesser extent, Sweden display the smallest effects (often to the point of being statistically indistinguishable from the Norwegian baseline).

The findings of our investigation thus suggest considerable variation in the mix of motive attributions within and across welfare state regimes. In line with past research highlighting the attitudinal and discursive effects of universalism (e.g. Larsen, Reference Larsen2008a; Larsen and Dejgaard, Reference Larsen and Dejgaard2013), Norwegians and Danes tend to ascribe more benign motives to those supporting and opposing redistribution – yet the mix of motive attributions in Sweden is much more ambiguous. Attitudes in the liberal welfare states of the US and the UK, in turn, are only similar vis-à-vis the motives of those opposed to redistribution. Instead, it is the French, not the British, who most resemble their American counterparts; indeed, France often shows evidence of an even more conflictual context than that found in the Anglo democracies, while the other Continental welfare states are generally home to a less extreme mix of motive attributions. Finally, although Italians and Spaniards are broadly less likely to assign less benign motives, they are far less similar when it comes to other motive attributions.

Conclusion

In this article, we have proposed a new way of looking at the moral politics surrounding issues of income redistribution and welfare state support. To that end, we developed and operationalized a new concept, motive attribution, which examines how people evaluate others’ motives for supporting and opposing income redistribution. We do so in the hopes of opening up a new and relevant field of research on the moral dimension of redistributive politics (see Moon, Reference Moon and Gutmann1988; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein1998). As a result of this moral dimension, redistributive politics is often highly contentious, and we expect research on motive attribution to help us to understand how support coalitions for and against redistributive policies might emerge, evolve, and relate (see Green et al., Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002; Skitka et al., Reference Skitka, Bauman and Sargis2005, Reference Skitka, Washburn and Carsel2015; Ryan, Reference Ryan2017).

The findings reported above provide a first cut at studying motive attributions, pointing out areas of both overlap and divergence cross-nationally. Examining the mix of motive attributions in our ten countries suggests that citizens on the whole tend to view anti-redistributive preferences in a more negative light than pro-redistribution preferences. Comparing responses cross-nationally, however, we find only limited support for the expectation that welfare state divisions would be central to the mix of motive attributions across the cases: in line with the literature on universalism (Jacques and Noël, Reference Jacques and Noël2018; Larsen, Reference Larsen2008a), Denmark and Norway do indeed appear to be home to a more benign set of motive attributions – yet it is less clear that Sweden falls into the same pattern, in particular with regard to pro-redistribution motives. At the other end of the spectrum, it is the US and France – two countries with markedly different welfare state regimes – that are generally associated with a more negative mix of motive attributions, while in the UK negative attributes are mainly applied only to those holding anti-redistribution stances. Thus, despite partial evidence of welfare state effects, in particular vis-à-vis universalism, we consider these results to be more closely aligned with research highlighting the limits of existing regime classifications (e.g. Jæger, Reference Jæger2009; Kevins and van Kersbergen, Reference Kevins and van Kersbergen2019; van Kersbergen and Vis, Reference Van Kersbergen and Vis2015).

Several limitations nevertheless mark this initial attempt at studying motive attributions. First, the present study has focused only on the motives ascribed to those who do or do not “want to redistribute wealth from the rich to the poor.” Yet this stylized distinction clearly obscures meaningful differences in redistributive preferences: at least across the countries under study, preferences for redistribution are more likely to be situated along a spectrum moving from more to less than to reflect a clear dichotomy opposing those for and against. Second, some of the listed motives (e.g. “to help themselves”) may prompt respondents to think only (or primarily) of the rich and poor when they reflect on the other potential motives driving those with anti- or pro-redistribution stances; consequently, it is difficult to say whether a priming effect may be colouring (via deservingness perceptions) some responses. Third and relatedly, attributing motives to imagined individuals necessarily implies that respondents may have different people in mind when they think about those who favour or oppose redistribution – a risk that is especially large when we compare respondents from different countries, as perceived differences in motives sit alongside actual differences. Finally, the present study only considers four categories of motive attribution. A more complete analysis would elaborate a thorough set of motive attribution categories and discern the extent of overlap between potentially related ones (such as self interest and personality defects).

Both the findings and limitations of the present study thus point to a number of avenues for further research. More generally, future work on the causes and consequences of more negative or positive motives attributions would be particularly welcome. Research in this vein could serve to explain cross-country patterns related not only to motive attributions, but also to a range of connected phenomena (e.g. polarization, redistributive preferences, policy u-turns). What is more, to the extent that mutable contextual factors may shape motive attributions, such research might even lay out potential policy routes toward mitigating social tensions and partisan animosity.

Acknowledgements

Early drafts of this article were presented at Aarhus University’s Department of Political Science, the 2016 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, and the Utrecht University School of Governance. We are thankful for the many helpful comments we received at these events, including from Charlotte Cavaille, Ekaterina Rashkova, and Barbara Vis. The project was made possible by funding from the Independent Research Fund Denmark (4003–00013) and Aarhus University Research Foundation’s AU IDEAS programme. Anthony Kevins also received financial support from a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship (Grant no. 750556).

Appendix

Appendix TABLE 1. Number of respondents per country

APPENDIX TABLE 2. Weighted descriptive statistics