Introduction

Active labour market programmes (ALMPs), designed to move unemployed persons into paid work, have become a core pillar of social policy across the developed world. While these vary in form and content (van der Aa and van Berkel, Reference van der Aa and van Berkel2014), the trend is towards ‘work-first/workfare’, aimed at forcing quick job entry, as pioneered in the US and UK from the 1980s (Seikel and Spannagel, Reference Seikel, Spannagel, Lohmann and Marx2018). A relatively neglected aspect, however, has been the role of employers. With employers increasingly seen as crucial to their ‘success’, there is growing academic and policy interest in why and how employers engage with such programmes (Ingold and Stuart, Reference Ingold and Stuart2015; Bredgaard, Reference Bredgaard2018). In the UK, state-driven ALMPs involve public, private and third-sector organisations (TSOs), with some TSOs also running their own employability programmes. Most research has focused on government-funded schemes. Few studies have examined employer engagement with programmes led by TSOs on the margins of workfare.

The position of employers vis-a-vis ALMPs is controversial. Greer (Reference Greer2016: 165) highlights the ‘recommodification of labour’ aimed at disciplining the unemployed to accept low-paid, precarious and dead-end jobs. Such critiques focus attention on the sustainability and quality of work (McCollum, Reference McCollum2012), and whether getting just ‘any job’ is beneficial for personal well-being (Chandola and Zhang, Reference Chandola and Zhang2018). Crucially, then, programmes need to be evaluated in terms of whether they lead to ‘decent sustainable employment’, used here to denote secure work that affords a real living wage and good working conditions, or realistic progression to such employment.

Consideration must also be given to the complex needs of many programme users. Van Berkel et al. (Reference Van Berkel, Ingold, McGurk, Boselie and Bredgaard2017: 503) define employer engagement as ‘the active involvement of employers in addressing the societal challenge of promoting the labour market participation of vulnerable groups.’ This includes, amongst others, persons with disabilities, poor mental health, previous offenders, refugees, single parents and carers, whose integration into working life makes considerable demands on employers (Frøyland et al., Reference Frøyland, Andreassen and Innvaer2019). Not-for-profit TSOs are seen to have advantages in supporting such individuals into work. Their social mission focuses on personalised support and individual empowerment, designed to help users progress at their own pace towards their own goals (Damm, Reference Damm2012; Lindsay et al., Reference Lindsay, Pearson, Batty, Cullen and Eadson2021). However, they still need to engage employers to provide work experience and employment opportunities.

Two recent UK studies offer a useful starting point for exploring employer engagement with TSO-led programmes in terms of employers’ motives and roles. Simms’ (Reference Simms2017) research on state-funded youth apprenticeship programmes stressed the importance of addressing employers’ human resource (HR) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) ‘logics’ in combination. Orton et al. (Reference Orton, Green, Gaby and Barnes2019) studied a non-governmental, TSO-led programme aimed at young people, and found employers could act as ‘gatekeepers to jobs’ and ‘proactive strategic partners’ involved in project design and implementation. Probing the interrelationships between these logics and roles would seem important if TSO-led programmes are to help vulnerable individuals into decent sustainable employment.

This article starts from the proposition that TSO-led programmes may have advantages in combining these roles and logics, compared with mandatory workfare programmes. Arguably, proactive employer partners with deep social commitment might offer a potential channel into decent sustainable employment if they can be persuaded to do so. However, such programmes may also confront employers seeking to fill low quality jobs which would then present TSOs with serious ethical dilemmas (Beck, Reference Beck2018).

This article explores these issues using a case study of two TSO-led projects in an English county. Drawing on interviews with programme actors, delivery partners and engaged employers, it addresses two key questions. First, what motivated employers to engage, and what roles were they prepared to embrace? Second, how far were the projects able to combine HR and CSR logics, and straddle gatekeeper and strategic partner roles, to open up decent sustainable employment opportunities? The findings highlight a more complex reality than existing theoretical propositions/models might lead us to presume when applied to TSO-led programmes working with vulnerable persons. The article opens with an overview of the literature on employer engagement with ALMPs, focusing on the role of TSOs in the UK. Next, the research context and methods are presented, followed by the findings. The discussion and conclusion consider why TSOs and other intermediaries may struggle to engage employers in helping vulnerable individuals into decent sustainable work.

Employer engagement with ALMPs

Until recently, research on employer engagement with ALMPs was a relatively neglected field – a reflection of the dominant supply-side orthodoxy which focuses on making the unemployed ‘job ready’, and positions employers as ‘passive recipients’ of labour (Orton et al., Reference Orton, Green, Gaby and Barnes2019). It is increasingly recognised that engaging employers is crucial – for example, by helping to ‘match’ users to employers’ recruitment needs. This remains a predominantly ‘supply-side’ approach as it takes employers’ recruitment and workplace practices as given. Employers, however, may be reluctant to modify their practices to be inclusive of individuals with complex needs who often require in-work support and work adjustments. ‘Demand-side’ ALMPs acknowledge this, seeking to address both individuals’ employability and employers’ practices (Bredgaard, Reference Bredgaard2018; Frøyland et al., Reference Frøyland, Andreassen and Innvaer2019).

In the Netherlands, van der Aa and van Berkel (Reference van der Aa and van Berkel2014: 20) identified three reasons why employers engage – to recruit workers, reduce wage costs, and social commitment to help the disadvantaged. Bredgaard and Halkjaer (Reference Bredgaard and Halkjaer2016: 51) used six theories to explain the motives behind Danish employers’ participation in a wage-subsidy programme. These studies highlight national institutional pressures, such as the role of employer organisations and trade unions, along with policy instruments, acting as incentives for employers to participate. Valizade et al. (Reference Valizade, Ingold and Stuart2022) found that the participation of Danish employers is linked to cohesive employer organisation and collective bargaining. In the UK, where collective bargaining is fragmented, engagement is more challenging but increases when employers receive information through social networks activated via membership of a business association. Even in relatively propitious contexts like Denmark, however, most employers remain ‘sceptical’ or ‘dismissive’ (Bredgaard, Reference Bredgaard2018: 365)

It is generally acknowledged that employers’ motives for engagement reflect an HR rationale, concerned with the relative costs and benefits of recruiting staff, and CSR concerns. In the UK, Simms (Reference Simms2017) found that employers participated in youth apprenticeship programmes when HR and CSR ‘logics’ combined. Asking employers to ‘do the right thing’ was insufficient, with ‘important implications for wider policy initiatives intended to help other groups of vulnerable workers into employment’ (p.563). Other studies suggest that UK employers’ engagement with ALMPs is limited and typically driven by ‘instrumental’, short-term considerations (Ingold and Valizade, Reference Ingold and Valizade2015: 31). McGurk (Reference McGurk2014) found employer engagement with programmes aimed at unemployed youth, while ‘weak’ overall, mainly involved sectors recruiting for low-paid retail jobs with limited entry requirements. Given the low skills profile of many programme users, the employers most likely to engage tend to have business models that limit the scope for decent sustainable employment with progression (Sissons and Green, Reference Sissons and Green2017: 570-571).

These studies question how far employers are prepared to engage and whether this is likely to deliver decent sustainable employment, especially given the UK’s weakly regulated labour market and high volumes of low-paid precarious work (TUC, 2021). Such issues loom large in relation to persons with complex needs. Many employers regard welfare claimants as lacking work motivation and/or too risky to employ – a problem not confined to the UK (van der Aa and van Berkel, Reference van der Aa and van Berkel2014). Furthermore, helping vulnerable individuals to adjust to the demands of working life may require considerable in-work support, mentoring and ‘job crafting’ – the costs of which, in terms of employers’ time and resources, can be considerable (van Berkel et al., Reference Van Berkel, Ingold, McGurk, Boselie and Bredgaard2017: 506). Might TSOs, however, be better positioned to enlist employers’ support in helping vulnerable users into decent sustainable jobs?

Third-sector involvement in ALMPs in the UK

In the UK, the role of the third-sector in ALMPs began in the 1980s and expanded under New Labour between 1997-2010 (Lindsay et al., Reference Lindsay, Osborne and Bond2014). The ‘marketisation’ of welfare-to-work services saw TSOs drawn into sub-contracting relationships with large ‘prime providers’, typically from the private sector. This continued under Coalition (2010-15) and Conservative governments (2015-) through the Department for Work and Pension’s (DWP) Work Programme (WP) (2011-17), which was mandatory for certain claimant groups. Welfare ‘conditionality’, as monitored by Jobcentre Plus (the DWP’s social security agency), whereby access to unemployment benefits depends on evidencing active job search, became more punitive (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Fletcher and Stewart2020).

The literature on TSOs’ role in ALMPs focuses mainly on the WP and the challenges of managing relationships with ‘primes’, securing a reliable income stream, and dealing with ‘payment-by-results’ (PBR) (Lindsay et al., Reference Lindsay, Osborne and Bond2014; Egdell et al., Reference Egdell, Dutton and McQuaid2016). Although the WP had employer engagement teams and a commitment to support individuals into work for longer than six months, research suggests this goal was subsumed by a PBR-funding formula that encouraged rapid job entry. This could result in providers ‘cherry-picking’ or ‘creaming’ clients who were easiest to move into work, while ‘parking’ those with more complex needs, prompting concerns that TSOs may experience ‘mission drift’ (Lindsay et al., Reference Lindsay, Osborne and Bond2014; Egdell et al., Reference Egdell, Dutton and McQuaid2016). Johnson et al.’s (Reference Johnson, Martinez Lucio, Grimshaw and Watt2023) study of an ‘innovation pilot’ under the WP’s successor, the Work and Health ProgrammeFootnote 1 , is instructive. Although user participation was voluntary, providers, including one TSO, remained locked into ‘familiar’ employability interventions. These centred around CV/interview preparation and confidence building, geared towards employers’ demands to fill low-wage jobs requiring little training.

The evidence suggests that engaging employers through state-funded ALMPs to deliver decent sustainable employment for vulnerable individuals is challenging. Might the prospects be brighter where TSOs run their own programmes with alternative funding arrangements? The few available studies of such programmes focus mainly on whether they can empower vulnerable users to achieve their own goals, given welfare conditionality and a deregulated labour market (Beck, Reference Beck2018; Lindsay et al., Reference Lindsay, Pearson, Batty, Cullen and Eadson2021). While these studies draw divergent conclusions, the role of employers is rarely considered.

There are good reasons, however, for thinking that TSO-led programmes might have advantages in engaging employers. Their place-based knowledge may help to engage local employers, even if this is not the exclusive preserve of such programmes. Employers may regard users on voluntary TSO-led programmes as more motivated and better prepared for work than those forced into mandatory government-funded schemes. Employers may also find TSOs’ social mission chimes with their CSR agenda and desire to be seen as a ‘good’ employer. Two important caveats are worth noting. First, CSR commitments can range from the tokenistic and instrumental to more deeply felt concerns to help disadvantaged groups. Second, some employers may see such programmes as a source of labour for hard-to-fill, poor-quality jobs. Following the pandemic and ‘Brexit’, labour shortages may open-up employment opportunities for programme users in certain sectors and localities, though not necessarily decent sustainable work (Manning, Reference Manning2021).

While TSO-led programmes may appeal to employers’ HR and CSR logics (Simms, Reference Simms2017), the empirical evidence for examining whether and how they might combine these logics to deliver decent sustainable employment for their users remains limited. Orton et al. (Reference Orton, Green, Gaby and Barnes2019) studied the Big Lottery-funded ‘Talent Match’ programme in England, aimed at young people not in education, employment or training, which offers useful insights. It identified two distinctive but overlapping roles for employers – ‘reactive gatekeepers to jobs’ and ‘proactive strategic partners’ engaged in programme design and implementation. Although the gatekeeper role was dominant, both groups cited CSR motives.

Orton et al. (Reference Orton, Green, Gaby and Barnes2019: 526) highlight ‘win-win-win’ outcomes, whereby employers received ‘job-ready’ workers, users were given appropriate training and ‘matched’ to vacancies, and the programme supported clients into work. Four points should be noted. First, in terms of gatekeepers, the study found that HR and CSR logics could overlap. Second, while the strategic partner group helped identify ‘hidden vacancies’ with other employers, they did not necessarily offer jobs themselves, which depended on their business model and labour requirements. Third, Talent Match sought to ensure clients were ‘employable on their own merits’ rather than seeking to change employers’ recruitment and workplace practices (Orton et al.: 525). Fourth, and perhaps most significantly, the study hints at difficulties in securing decent sustainable employment. Some employers were looking to fill ‘low paid temporary jobs with variable hours’, with one company offering only zero-hours contracts (Orton et al.: 522-23). Indeed, Sanderson (Reference Sanderson2020: 1323) notes that three-fifths of users secured no employment, and most of those entering work experienced ‘impermanence and precarity.’

Based on existing theorisation, it might be argued that programmes need strong partners with deep social commitment and business models that afford decent sustainable employment who are willing to provide adapted jobs for vulnerable clients. If so, a key question is whether TSO-led programmes can address employers’ HR and CSR concerns in combination, and straddle gatekeeper and strategic partner roles, to open up such employment opportunities. To explore this empirically, the research focused on two projects in an English county.

Research context and method

‘Project-Adult’ and ‘Project-Youth’ operate under a single management umbrella, seeking to help persons, aged 18+ and 15-24 respectively, into employment, education/training, or job search. They are part of the Building Better Opportunities programme, co-funded by the ‘Big Lottery’ and European Social Fund, with funding channelled through a lead TSO in the county. Users participate on a voluntary basis. Most have complex needs, including low education, disabilities, poor mental health, alcohol/substance use and caring responsibilities.

Project-Adult users are assigned an ‘employment support officer’ (ESO) who develops a personalised support plan. For Project-Youth, a ‘key worker’ provides tailored support with the help of delivery partners that have specialist expertise in working with young people. Funding is based on three-year grants, with users expected to progress towards their own goals at their own pace. The lead TSO has a relatively relaxed approach to setting outcome targets which provides space for ESOs and key workers to take account of client needs. Both projects operate with a small team of staff and limited resources, which means relying on other partners to interface with employers (Payne and Butler, Reference Payne and Butler2022). For Project-Adult, employers are engaged via a national partner, Business in the Community (BITC), while Project-Youth uses various national and local partners.

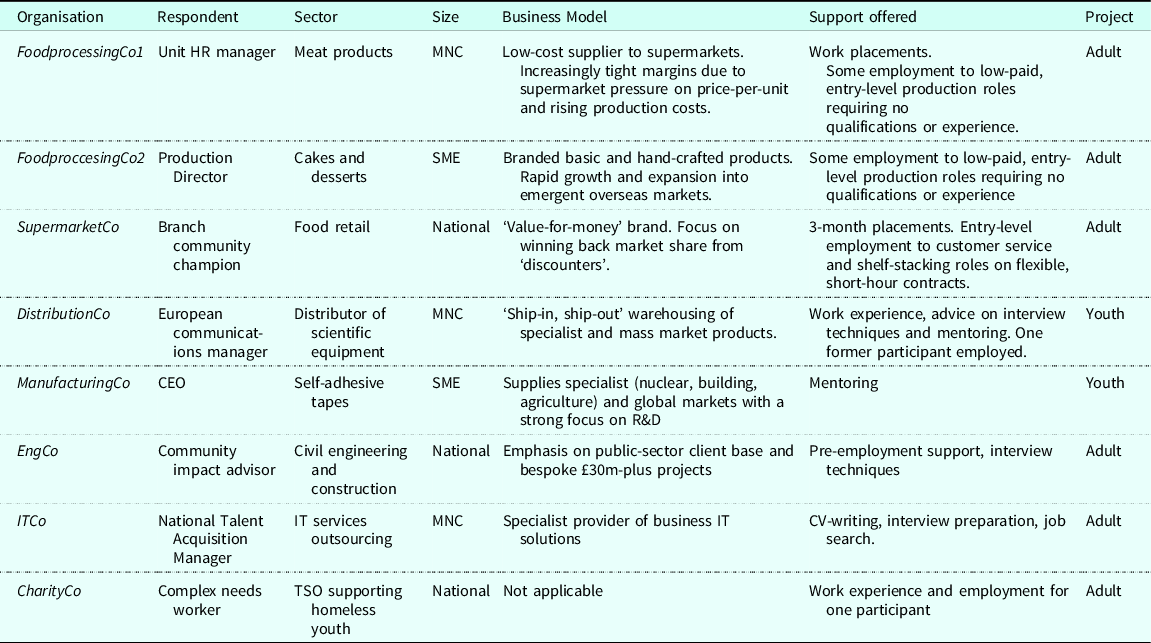

This article draws on 29 semi-structured interviews with project leads, ESOs, key workers and delivery partners, including eight employers (Tables 1 & 2). Following university ethical clearance, the research was conducted between November 2020-May 2021 at the height of the pandemic. Participation was voluntary and based on informed consent. Employer interviews were facilitated by project leads and BITC at a time when securing interviews was challenging. The eight employers are drawn from different sectors and have contrasting business models, and were regarded by project leads and BITC as broadly representative of engaged employers.

Table 1. Interviewees

* Joint interview

** Focus group with Project-Adult manager and data analyst

Table 2. Employer characteristics

The timing of the research is significant. The pandemic saw a large fall in UK employment, peaking in the second quarter of 2020, with differential effects on sectors within the study. For example, wholesale and retail experienced a 6.5% reduction in employment from 2020Q2 to 2021Q1 (Economics Observatory, Reference Observatory2021). The UK’s departure from the European Union has led to some low-paying firms in the food processing sector experiencing labour shortages, often linked to local labour market factors (Manning, Reference Manning2021). The pandemic impacted on the projects’ engagement with employers, especially their ability to broker workplace tours, placements and employment opportunities. The interviews sought, therefore, to unpack employers’ roles in ‘normal times’, and how this might develop post-pandemic.

All interviews were conducted ‘online’ and lasted 60-90 minutes. Apart from a focus group and joint interview, most were undertaken with individual respondents. Those with project teams covered programme governance, interactions with users, the challenges users faced in the labour market, and the role of employers. Interviews with BITC and delivery partners addressed how employers were engaged, their views on employer motives, and the experience of users receiving help, placements or employment. Interviews with employers explored how and why they were involved, the nature of any employment offered, and prospects for further involvement. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, with the data analysed thematically. To ensure coding was consistent, a small sample was initially coded by the researchers using codes derived from the literature review. Some codes were added to capture key insights before full coding of the data was undertaken. Any queries were followed up with participants through email.

Employer engagement in action

The research sought to examine whether TSO programmes are well placed to engage employers in providing decent sustainable employment for vulnerable users by combining HR and CSR ‘logics’ (Simms, Reference Simms2017) and linking gatekeeper and strategic partner roles (Orton et al., Reference Orton, Green, Gaby and Barnes2019). The aim was to categorise the roles that employers were actually playing or might be prepared to adopt, whilst probing the depth of any CSR commitment and the nature of any employment offered. It was also felt important to examine the views of the project teams and delivery partners to triangulate different perspectives beyond those of employers. We begin with project perspectives, before turning to those of employers.

Project perspectives

Significantly, neither project included a role for employers as ‘strategic partners’ in project design and implementation. Project leads noted that, with limited resources, there was little scope for teams to directly engage with employers. For Project-Adult, the main link with employers is through BITC, which champions the business case for inclusive hiring, ‘good work’ (including providing a ‘real living wage’ and in-work progression), and supporting disadvantaged groups into employment. The aim is to work with businesses offering ‘quality sustainable work’ (BITC2). In practical terms, the focus is on signing-up employers to provide workplace tours and two-week placements that may lead to employment. Securing placements was seen as the greatest challenge, given the costs to employers and the need to clarify business benefits. The primary aim was getting clients a job interview, without ‘asking the employer to do massive changes around actual work conditions’ (BITC1).

Small employers were seen as difficult to engage. Employers willing to offer employment were often said to be struggling to fill vacancies and frustrated with ‘unreliable’ agency workers. The Social Value Act, which requires employers bidding for public contracts to demonstrate ‘social value’ – for example, by helping disadvantaged groups – was also seen as incentivising employer engagement. This typically involved employers offering to help clients with interview skills and CV writing. Overall, local employer engagement was regarded as a ‘tough nut to crack’, especially securing work experience and employment opportunities (BITC1).

It is questionable how far employers are screened for offering decent sustainable employment, and project leads were unaware if business intermediaries undertook such screening. BITC conducts quarterly post-employment checks during the first 12 months of employment. However, there is no tracking of job quality, including in-work progression, just whether the person remains employed. During the pandemic, BITC decided not to respond to labour requests from warehouses, given health and safety concerns over lack of social distancing. Nonetheless, BITC is prepared to engage with organisations, like Amazon, and ‘try to edge them to become an employer of choice’. While BITC ‘ideally’ seeks to avoid employers offering ‘zero-hours contracts’, it does not dismiss enquiries from those offering ‘flexible’, short-hour contracts: ‘we make the client aware…and it’s their choice’. This often means ‘walking a fine’ line between deciding which employers to work with and ‘the dire need for employers to offer us the work’ (BITC1).

A three-month placement for Project-Youth clients with a major UK retailer was highlighted as a ‘top-notch’ programme. Brokered by a national delivery partner (Youth-partnerB), with wages covered by the DWP, users have the opportunity to learn transferable retail skills in a ‘market-leading’ organisation. Few were said to achieve permanent jobs with the retailer, which depended upon vacancies being available when the placement ended. A key worker could recall just ten permanent job offers in three years: ‘I feel like sometimes you can almost set a young person up to fail by putting them in a temporary contact’ (PY-Keyworker-YouthpartnerB). The respondent had raised concerns with the national partnerships’ manager after the retailer had shortened the placement to four weeks to fill Christmas vacancies: ‘I didn’t like the fact that basically we were acting as a recruitment agency for Christmas temp jobs’ (PY-Keyworker-YouthpartnerB). It appears that nothing was done, however, for fear of losing the contract. There were also concerns about the varied quality of placements, with some store managers offering little support. Some users had not received basic induction training, a workplace tour or even a uniform, and several had reported being ‘bullied’ and ‘shouted at’ (PY-Keyworker-YouthpartnerB).

Youth-partnerA engages local employers to help young people with a range of support from workplace placements to help with CV-writing and interview technique. Employers pay a staggered membership fee to be a ‘Bronze’, ‘Silver’ or ‘Gold’ medal partner, depending on company size and the level of support offered. Again, the biggest challenge was getting partners to offer work placements. The respondent found it ‘annoying’ that some employers would pay a fee to badge their CSR credentials without offering work experience. The few that did tended to ‘cherry pick’ those ‘going to university’ or ‘with quite good A-levels’ rather than young people requiring ‘extra support’. Of thirty-five fee-paying members, only five were currently active, and changing employer attitudes was seen as ‘difficult’ (PY-Keyworker-YouthpartnerA).

While the projects did not seek to engage employers as strategic partners, they have sought to enlist them as gatekeepers to jobs and as partners offering help with general employability skills. The view from the projects would suggest that combining HR and CSR logics, and straddling gatekeeper and partner roles, to open up decent sustainable employment opportunities is challenging. Faced with the need to secure work experience and employment opportunities, the projects and their intermediaries would not appear to have pushed hard on job quality or made demands on employers to offer in-work adaptation for vulnerable individuals. The next section examines employers’ perspectives.

Employer perspectives

This section examines employers’ roles and motives for engagement across two groups: gatekeepers to jobs and non-strategic, low-level partners. In addressing HR and CSR logics, it probes the type of employment made available, along with the nature and depth of any CSR commitment, and considers the prospects for combining logics and roles to deliver decent sustainable employment opportunities.

Gatekeepers to jobs

This group comprises four of the eight employers. It includes two food processing firms, both of which hosted workplace tours for Project-Adult participants, a large supermarket, and a charity. FoodprocessingCo1 produces meat products for supermarkets, and had provided employment for six participants from Project-Adult. With ‘fridge-like’ working conditions, routinised work and pay just 29 pence above the national minimum wage (NMW), the HR manager admitted that ‘it’s not the sexiest place to work.’ The company had previously relied heavily on East European migrants and was now experiencing acute labour shortages following ‘Brexit’ and immigration restrictions on the entry of low-skilled foreign workers. With labour turnover averaging 19%, and a local Amazon warehouse offering better pay, the company was ‘up against it…that’s why I try to work with the local community and bring people in.’

Project-Adult participants were seen as preferable to agency workers and welfare claimants whom, it was claimed, applied for positions simply to satisfy the DWP’s ‘conditionality’ demands:

…there’s a lot of people who are on benefits, put themselves forward for things and really have no intention…of working…The DWP doesn’t work…I don’t think there’s enough penalties if people don’t accept jobs.

FoodprocessingCo1 was, therefore, increasingly looking to use Project-Adult as a recruitment channel: ‘I would go to [Project-Adult] before I’d go to the DWP’. Although progression opportunities were available to team leader and supervisory positions, there was limited evidence of movement beyond entry-level operative. The sole exception was a participant with mental health issues who had become a team leader. This individual had been invited to speak at public events held by Project-Adult and was celebrated as a success story. While the ‘HR logic’ in this case involved sourcing cheap labour for hard-to-fill vacancies, the employer also alluded to CSR, insisting this was ‘about the community and giving back’.

FoodprocessingCo2 manufactures cakes and pastries for supermarkets, employing around 40 production operatives with entry-level positions paid at the NMW. The work is low-skilled, with opportunities available for ‘people that haven’t worked in a while.’ Four participants with Project-Adult had been employed since 2019. This partly reflected a need to meet supermarkets’ ‘social audits’, but the production manager also considered it ‘a good thing to get involved in the community’. Unlike FoodprocessingCo1, positions were ‘easy to fill’, and there was no clear HR logic to its engagement. While project participants are cheaper to employ than agency workers, Food processingCo2 did not anticipate employing more participants owing to the extra support they needed. One ex-project user with mental health issues had left after two weeks, having gone ‘off the rails’, the manager noting that ‘we let him down because there was no intervention.’ Another with mental health issues had ‘grown in stature’ as an entry-level operative but had struggled emotionally during lockdown. While ‘skilled operative’ and team leader roles were available, the manager acknowledged: ‘there isn’t much opportunity for progression.’

SupermarketCo is a large grocery retailer. Pay is around £10-per-hour, with part-time, short-hour and ‘flexi-contracts’ available. How far these jobs represent ‘quality sustainable employment’ is questionable. An HR logic was evident in that project participants could potentially fill available entry-level positions. The store had provided 80 people from Project-Adult or other local projects with work experience, 16 of whom had secured jobs. The low conversion rate reflected participants either finding the work was ‘not for them’ or ‘a lack of vacancies’ (local community champion). SupermarketCo’s involvement also signalled the retailer’s desire to be seen as a good local employer. The ‘local community champion’ considered this was more about developing a ‘corporate image’, where rival supermarkets were also competing to demonstrate their socially-progressive credentials: ‘look at us we’re great…It comes from head office…saying you need to do this…unfortunately, we have to tick boxes…keep up appearances.’ SupermarketCo’s engagement appears to involve an instrumental CSR logic, which seeks to project the right externally-facing profile to customers and local stakeholders.

The final employer in this group is CharityCo, a charity supporting young homeless persons, and a delivery partner for Project-Youth. These links had enabled one Project-Adult participant, whose level of need was lower than many other project participants, to obtain a zero-hours contract before transitioning to a full-time position as a ‘Complex Needs Worker’. This particular case appears to be a serendipitous one-off employment opportunity, and an anomaly in terms of the type of engaged employer offering employment.

Non-strategic, low-level partners

This group comprises four employers who engage as ‘non-strategic, low-level partners’ without providing employment for users. ManufacturingCo produces specialist adhesive tapes and has entry-level production roles that do not require any qualifications or experience. DistributionCo, a company distributing scientific equipment, offers potentially suitable entry-level positions in picking, packing and general warehousing. Neither was looking to offer jobs to project participants, nor did they view the projects as a future source of labour. The other two employers, ITCo, a technology company providing IT services, and EngCo, a company specialising in civil engineering projects, did not have potentially suitable entry-level positions, reflecting their business models.

These employers were helping project participants with general employability skills. The CEO of ManufacturingCo set aside two hours a week to mentor participants on Project-Youth. The marketing and communications manager of DistributionCo offered ‘Speedy Speaker talks’ and ‘mentoring advice’ to Project-Youth participants as part of a ‘proactive policy around community action’. ITCo’s ‘talent acquisition manager’, and EngCo’s ‘community impact advisor’, offered one-on-one support with CV writing, job search, LinkedIn profiles and mock interviews.

All cited a CSR logic and commitment to helping disadvantaged groups. ManufacturingCo’s CEO noted that while there was ‘not a huge commercial driver…you’ve got to do this sort of stuff’, which benefitted the company’s ‘social media image’. ITCo were ‘very much into their CSR…there’s not many companies who take it as seriously’, and the HR Director was said to be ‘extremely passionate about trying to give people opportunities.’

DistributionCo had a ‘proactive policy around community action’, with every site having a ‘Community Action Council’. Employees received eight hours paid leave annually to support local activities. The organisation was engaging with several projects supporting disadvantaged groups, including ex-offenders. In terms of business/HR benefits, such projects were seen as helping managers offering mentoring, advice and mock interviews to hone their skills in these areas, whilst demonstrating to its employees that it is a ‘caring employer’. The manager argued getting other employers to provide even this level of engagement could not rely on appeals to act responsibly as ‘pulling at the heart strings of it’s your duty as a good citizen, doesn’t wash’. Projects and intermediaries, therefore, needed to do more to demonstrate business benefits.

EngCo’s involvement stemmed from having a CEO committed to ‘seeing young people develop’. There was also a business logic centred on meeting ‘social value criteria’, specified in the Social Value Act, when tendering for public contracts. The employer noted that the weighting attached to such criteria had increased from 15 to 30 percent, and felt this could help to drive employer engagement with local projects helping disadvantaged groups into work. Others, however, insisted employers could tick the ‘social value’ box in a fairly limited and ‘painless’ manner by paying ‘lip service [to the criteria]…because ultimately the tenders win…on cost’ (DistributionCo). DistributionCo itself paid a £3,000 annual fee to be a ‘Gold medal’ partner with Youth-Partner1, seeing this as an ‘easy way’ to get involved with local community projects.

As noted above, the projects had not sought to involve employers as ‘strategic partners’. Significantly, none of these employers saw themselves adopting such a role, assuming the projects were minded to approach them to do so. Most preferred, what one called, a ‘more loosely structured way [of participating]’ (ManufacturingCo), and suggested using currently engaged employers and ‘big brands’ to engage other employers within their networks.

In the absence of a clear HR logic, employers in this group, some of whom potentially might have offered participants decent sustainable employment, showed no intention of doing so, despite citing commitments to CSR. A relatively modest level of engagement, centred on helping participants develop general employability skills, overlaps with concerns around corporate image, management development, or meeting local procurement requirements. How far such engagement helps vulnerable individuals to secure decent sustainable employment in the wider labour market cannot be ascertained from this data. It might be argued that such support, insofar as it focuses on general employability skills, is, at best, most likely to improve participants’ ability to compete for low-wage, entry-level positions requiring little training (McGurk, Reference McGurk2014; Johnson et al., Reference Valizade, Ingold and Stuart2022). Indeed, interviews with project leads suggest participants on Project-Adult who obtained employment were mainly taking-up low-wage, casual jobs in retail, care work and warehousing. Those on Project-Youth were predominantly entering retail work, reflecting the ‘precarious pathways’ many young people experience (Purcell et al., Reference Purcell, Elias, Green, Mizen, Simms, Whiteside, Wilson, Robertson and Tzanakou2017), not least those with complex needs.

Discussion

The findings indicate there are two groups of engaged employers. The first are ‘gatekeepers to jobs’ with a clear HR logic. This group comprises employers looking to source cheap labour or offering limited employment opportunities of questionable job quality (FoodprocessingCo1, FoodprocessingCo2, SupermarketCo). All referred to a CSR logic in weak, instrumentalist terms.

The second group are ‘non-strategic, low-level partners’. These lack an HR logic insofar as they do not offer employment opportunities but are willing to help with ‘general employability skills’, e.g. CV writing and interview technique (ManufacturingCo, DistributionCo, ITCO, EngCo). For these employers, the CSR logic appears somewhat stronger than the first group. This may be championed by an individual, or underpinned by general business concerns, including, in some cases, meeting social value criteria when tendering for public contracts. Crucially, what is missing are employers willing to provide decent sustainable jobs and in-work adaptation, including customised job tasks, mentoring and supervision, to help individuals with complex needs to stay in work (van Berkel et al., Reference Van Berkel, Ingold, McGurk, Boselie and Bredgaard2017: 506).

The findings problematise Simms’ (Reference Simms2017) ‘dual logics’ proposition as a driver of employer engagement, and Orton et al.’s (Reference Orton, Green, Gaby and Barnes2019) dual categorisation of employer roles, when applied to TSO-led programmes seeking to help vulnerable persons into decent sustainable employment. Contrary to Simms (Reference Simms2017: 562), while some gatekeepers referred to both HR and CSR concerns, these rationales did not conjoin to open up such employment. Turning to Orton et al.’s (Reference Orton, Green, Gaby and Barnes2019) categories, the projects did not seek to engage employers as ‘proactive strategic partners’ in project design and implementation. Moreover, existing low-level partners, despite professing CSR commitment, lacked any appetite for a ‘strategic’ role. As Orton et al. (Reference Orton, Green, Gaby and Barnes2019) note, this may not be the case where programmes are intent on seeking such engagement. The findings indicate, however, that Orton et al.’s (Reference Orton, Green, Gaby and Barnes2019) modelling may need adapting to take account of employers as ‘low-level partners’. More importantly, partners that might potentially have offered decent sustainable employment were unprepared to do so as there was no clear HR rationale given their business model. In this respect, Simms’ central point that a CSR logic alone may be insufficient remains apposite.

A reasonable supposition might be that what is needed are strong partners with deep social commitment and business models that afford decent sustainable employment who are willing to adapt jobs for vulnerable clients. While theory points to the need to combine HR and CSR logics and straddle gatekeeper and strategic partner roles, the findings suggest a more complex reality. The difficulty, as Orton et al. (Reference Orton, Green, Gaby and Barnes2019) note, is that strategic partners are reluctant to offer employment unless there is an HR logic and clear business benefit. An easy coalescence of CSR and HR logics appears unlikely however. As Frøyland et al. (Reference Frøyland, Andreassen and Innvaer2019: 9) observe, ‘addressing the “hard to place” puts high demands on resources and is therefore costly.’ Given such demands on the employer, such engagement would seem to rely on a deep commitment to CSR far beyond anything displayed by employers participating in these two projects, or, in its absence, other incentives and policy levers, as discussed below.

Conclusion

While employers are seen as vital to the success of ALMPs (Ingold and Stuart, Reference Ingold and Stuart2015; Bredgaard, Reference Bredgaard2018), research examining their roles and motives for engagement remains limited – a gap that widens in relation to non-governmental, TSO-led employability programmes. Studies suggest that employer engagement depends on combining HR and CSR logics (Simms, Reference Simms2017), with employers capable of acting as ‘gatekeepers to jobs’ and ‘proactive strategic partners’ (Orton et al., Reference Orton, Green, Gaby and Barnes2019). Drawing upon research undertaken with two TSO-led projects in England, this article has explored whether such programmes can combine these logics and roles to engage employers in opening up decent sustainable employment opportunities for vulnerable users (McCollum, Reference McCollum2012; van Berkel et al., Reference Van Berkel, Ingold, McGurk, Boselie and Bredgaard2017).

The findings underscore the challenges such programmes may encounter. Engaged employers fell into two groups – ‘gatekeepers to jobs’ and ‘non-strategic, low-level partners’ offering help with general employability skills. There was no evidence of either being willing to adapt their employment practices to assist vulnerable individuals to enter and hold down decent sustainable work. Indeed, some engaged employers were using the projects as a recruitment channel for low-quality jobs (Greer, Reference Greer2016). This raises serious ethical dilemmas for TSOs given their social mission (Damm, Reference Damm2012; Beck Reference Beck2018). Set alongside Orton et al.’s (Reference Orton, Green, Gaby and Barnes2019) research, the findings question how far TSO-led programmes can deliver ‘win-win-win’ gains for the programme, its users and employers once the quality and sustainability of employment are factored into the criteria for ‘success’.

Engaging employers who are willing and able to provide decent sustainable employment, including appropriate in-work support and workplace adjustments, would mean attracting those whose business model lends itself to such employment. How, or to what extent, such employers can be engaged is a key question. Given the heavy demands made on employers’ time and resource, it seems unlikely that there is a clear HR logic for such engagement. Contra Simms (Reference Simms2017), this would seem to leave programmes having to appeal almost exclusively to a strong CSR orientation.

Simms (Reference Simms2017) may well be correct, however, in that simply appealing to employers to ‘do the right thing’ is unlikely to receive many takers. Programmes might try to address this conundrum by offering more focused pre-employment support, including targeted skills development, that is strategically focused on employers with decent sustainable employment opportunities. They might also offer clients continuing support when taking up any employment, including with progression opportunities (Sissons and Green, Reference Sissons and Green2017: 566). Programmes would have to establish clear criteria for deciding which employers to engage with, and be willing to challenge employers around hiring practices and in-work support. Programmes are likely to face a dilemma in that the more demanding they are of employers in terms of the quality of employment, the fewer are likely to engage and offer employment opportunities (Sissons and Green, Reference Sissons and Green2017). This may leave vulnerable users even more reliant on employment they can secure with the help of project workers through ‘open competition’ in the labour market, which is problematic given their position at the back of the job queue (van der Aa and van Berkel, Reference van der Aa and van Berkel2014: 25).

The research makes an important empirical and conceptual contribution to the study of employer engagement with activation/employability programmes. While TSOs might be thought well placed to combine HR and CSR logics and to link up gatekeeper and strategic partner roles, our research suggests this is problematic. If TSOs are to engage employers in providing decent sustainable employment, they may have to appeal almost exclusively to a CSR logic which may cut little ice with employers.

Clearly, the challenges TSOs confront partly reflect the complex needs of the jobseeker client group. Another element is how far the programmes themselves seek to engage employers to deliver relatively ambitious employment outcomes for users, along with their resources and ability to do so. The national ‘regulatory framework with respect to wages and working conditions’ (van der Aa and van Berkel, Reference van der Aa and van Berkel2014: 25) is also key, given that the UK labour market generates many poor quality, entry-level jobs. Other factors, linked to the current conjuncture, should be noted. While the pandemic and Brexit have left some firms in sectors like food processing in dire need of labour, it does not follow that the jobs available are decent or sustainable (TUC, 2021; Manning, Reference Manning2021), even if employers are willing to consider employing the users of TSO-led programmes.

It seems reasonable to ask, therefore, how far any UK intermediary (public, private or third-sector) can deliver ‘win-win-win’ outcomes for programmes, users and employers (Orton et al., Reference Orton, Green, Gaby and Barnes2019). Such an assessment may depend on what counts as a ‘good’ employment outcome and who makes such judgements (Payne and Butler, Reference Payne and Butler2022). This is further complicated in that ‘job quality’ comprises many elements, and not all entry-level jobs are the same (Carré et al., Reference Carré, Findlay, Tilly, Warhurst, Warhurst, Carré, Findlay and Tilly2012). Allowing for some variability in the quality of these jobs, programmes can try to factor this in when engaging employers and helping vulnerable individuals into work they value.

Academics need to be realistic when making policy recommendations (McCollum, Reference McCollum2012), without setting their sights too low and forsaking progressive alternative possibilities. Valizade et al. (Reference Valizade, Ingold and Stuart2022: 19) note that, in Denmark, the combination of cohesive employer associations and trade unions supports more progressive employment policies. This ‘explains why Danish employers were more likely than their British counterparts to commit to ALMPs that subsidised and guaranteed jobs to the unemployed, while UK firms opted for short-term work placements.’ Notwithstanding national institutional differences, potential policy levers exist in terms of tax credits, the reimbursement of on-job training costs, wage subsidies and public procurement based on ‘social return’ (van der Aa and van Berkel, Reference van der Aa and van Berkel2014: 18). The last of these would mean going beyond current ‘social clauses’ in the UK’s Social Value Act which allows employers to demonstrate CSR commitment to helping local disadvantaged groups in fairly limited ways.

ALMPs cannot ‘buck’ the labour market. None of the above circumvents the need for welfare and labour market reforms to de-commodify labour by improving labour and social rights so that the unemployed have better jobs on offer and the ability to refuse employment where it clashes with caring responsibilities (Greer, Reference Greer2016; Johnson et al., Reference Valizade, Ingold and Stuart2022). This would help to create a context where the public employment system, and TSOs supporting employability within and outside it, would find it easier to engage employers in providing decent sustainable employment. Even with a more conducive ‘configuration’ of regulations, responsibilities and incentives (van der Aa and van Berkel, Reference van der Aa and van Berkel2014: 25), however, vulnerable individuals would still need tailored, humane employment support of the kind TSOs can offer.

This research has several limitations. Whether existing forms of employer engagement help project participants to obtain ‘decent sustainable employment’ in the wider labour market is difficult to ascertain from the data. This would require more longitudinal research tracking what happens to them over time. The findings are based on a single case study involving two small local projects; it is important, therefore, to avoid generalising to others. Further research within the UK and beyond, may shed light on how far, and under what conditions, TSO employability programmes can balance the interests of vulnerable unemployed people and employers. TSOs have potential advantages in working with such individuals and local employers, and are well-placed to support the public employment system in such an endeavour. Whether that potential can be fully realised in the UK remains to be seen.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their very valuable comments. All errors are the authors’ own. The article represents a 50/50 contribution by each author.

Competing interests

The authors declare none