Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 September 2012

1 Olmstead (o.c. 247 f.) writes: ‘Among the words not in Liddell and Scott are the Latin νομμείας and καστέλλους, εἰσένγραφον, 1. 44; τρέπου, 1. 62; εὐγούρου, 1. 66 … σπαθαφόρου is used in 1. 64 for εὐγούρου, γινЗοφλακος 1. 66, is more exact than the common γαзοφύλαξ … While ảμαξα as a Persian loanword for “wagon” is well known, ἁμαξάσπου appears to be a transliteration of a Persian word meaning “wagon horse”. ἐξεντίας, 1. 8, is cited in the eighth edition only from First Maccabees but is missing in the last revision.’ On what Greek text these remarks are based I do not know; reference to Sprengling's edition, known to Olmstead (246, n. 13), shows that we must read μνείας (l. 52, p. 390; μνείαν occurs in 11.39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45, 53, pp. 385 ff.) for (1. 44, p. 387) for νομμείας, εἰς ἔνγραφον (l. 62, p. 410) for τρέπου, θυρουροῦ (l. 66, p. 414) for εἰσένγραφον, ἐπιτρόπου, σπαθοφόρου (l. 64, p. 413) for σπαθαφόρου, γανӡοφύλακος (l. 66, p. 415) for γινЗοφύλακος, and ἐξ ἐναντίας (l. 8, pp. 360 f.) for ἐξεντίας. Along with καστέλλους (l. 12) we have the equally unprecedented καστέλλοφύλακος, (l. 63), not to mention a number of Persian words which have found an entry into this professedly Greek document. The word Amazaspou (or Hamazaspou) in l. 60 (p. 409) appears to be a Persian proper name. Cf. n. 3 below.

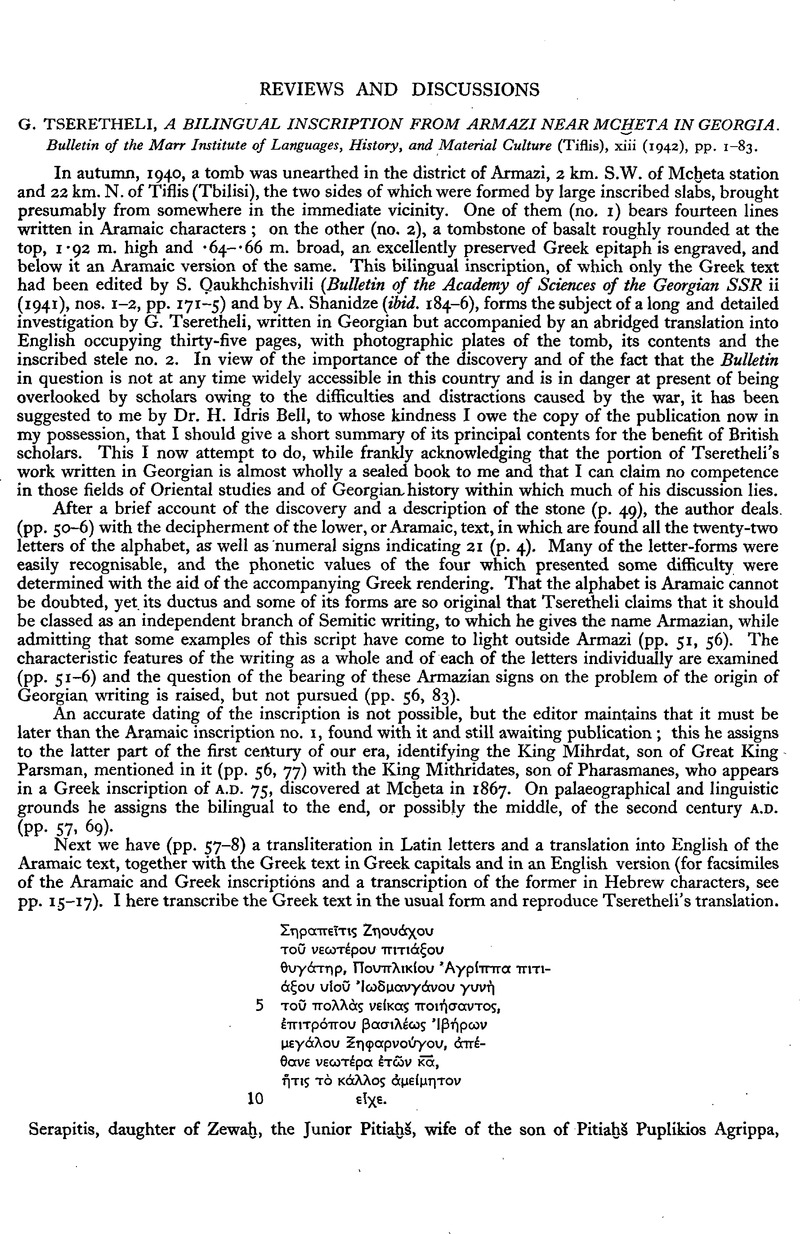

2 Dittenberger, Cagnat and Dessau (see below) read Ἰαμάσδει τῷ υἱῷ, but Amiranashvili, after a renewed examination of the stone, vouches for the reading Ἰαμὰσπῳ. On the stone is engraved φιλορωμαίων and ἐξωχύροσαν. Wolters' suggestion that the mason should have written φιλορωμαίῳ καὶ Ἰβήρων τῷ ἔθνει has been recorded with approval by subsequent editors. Tseretheli refers for this inscription to three publications in Russian or Georgian which are out of my reach (p. 57, n. 1), and to Debevoise, N. C., Political History of Parthia (Chicago, 1938), 201,Google Scholar n. 60, with bibliography. But the references there given are so inadequate, omitting as they do the three epigraphical collections to which students most naturally turn, that I venture to offer a fuller bibliography. Mohl, J. and Renier, L., Journal Asiatique sér. vi, t. xiii (1869), 93Google Scholar ff. (with engraving: wrongly cited as JA 1859, t. ix, p. 93,Google Scholar by C. de la Berge, Essai sur le règne de Trajan 163), drew largely on an article by J. de Bartholomaei in a Georgian periodical, and formed the basis of Mommsen's, edition in CIL iii, 6052Google Scholar (not 605, as in OGI); the inscription was independently published in the Νέα Ἐφημερίς of Constantinople for 7th–19th December, 1896, which led to a new and improved text by Wolters, P. (Ath. Mitt, xxi, 472Google Scholar f.), on which all later editions are founded (except H. C. Newton, Epigraphical Evidence for the Reigns of Vespasian and Titus 19 f.); W. Dittenberger, OGI 379; Cagnat, R., IGRom. iii, 133;Google Scholar ILS 8795. Cf. also Amiranashvili, A., Izvestia of the Academy for the History of Material Culture, Leningrad, v (1927), 409Google Scholar ff. (summarised in Phil. Woch. xlviii, 838); B. W. Henderson, Five Roman Emperors 64; R. Syme, CAH xi, 143; N. C. Debevoise l.c.

3 See Kaibel's notes in Epigr. Graeca 549, and IG xiv, 1374; also PIR ii, 382, no. 459, and OGI 379, n. 9. The name Ἀμάзασπος, it may be noted, recurs in l. 60 of the Shapur-inscription (Am. Journ. Sem. Lang. lvii, 409); cf. n. 1 above.