Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 November 2014

1 Janin, R., Constantinople byzantine (Paris 1950), 67-69 and 81–84 Google Scholar; Wiener, W. Müller, Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls (Tübingen 1977) 255–57Google Scholar, with prior bibliography; Mango, C., “Constantinopolitana,” JdI 80 (1965) 305–13Google Scholar; id., “Constantine’s Porphyry Column and the Chapel of St. Constantine,” Deltion tes Christianikes Archaiologikes Etaireias 10 (1981) 103-10; id., “Constantine's Column,” in id., Studies on Constantinople (Aldershot 1993) Study II; Dagron, G., Naissance d’une capitale: Constantinople et ses institutions de 330 à 451 (Paris 1984) especially 37–42 Google Scholar; Karamouzi, M., “Das Forum und die Säule Constantini in Konstantinopel: Gegebenheiten und Probleme,” Balkan Studies 27 (1986) 219–36Google Scholar; Bauer, F. A., Stadt, Platz und Denkmal in der Spätantike (Mainz 1996) 173–77Google Scholar; Bassett, S., The urban image of late antique Constantinople (Cambridge 2004) especially 192–204 Google Scholar; Bardill, J., Constantine: divine emperor of the Christian golden age (Cambridge 2012) especially 28–63 Google Scholar. Note also Barnes, T. D., Constantine: dynasty, religion and power in the Later Roman Empire (Chichester 2011) especially 107–43Google Scholar, whose radical revision of the prehistory of Constantinople is beyond the scope of this essay.

2 Dagron, Naissance (supra n.1) 39-40; Baldovin, J., The urban character of Christian worship: the origins, development, and meaning of the Stational Liturgy (Orientalia Christiana Analecta 228, 1987) 169 Google Scholar.

3 C. Mango, “The columns of Justinian and his successors,” and “Justinian’s equestrian statue,” in Studies on Constantinople (supra n.1) study X and study XI = ArtB 41 (1959) 351–56Google Scholar; see also Raby, J., “Mehmed the conqueror and the equestrian statue of the Augustaion,” Illinois Class. Stud. 12 (1987) 305–13Google Scholar; Vickers, M., “Mantegna and Constantinople,” Burlington Mag. 117 (1976) especially 683 Google Scholar; see also Stichel, R., “Zum Bronzekoloß Justinians I. vom Augusteion in Konstantinopel,” Griechische und römische Statuetten und Großbronzen, Akten der 9. int. Tagung (Vienna 1988) 133-36Google Scholar; Bauer (supra n.1) 158-62.

4 Proc., Aed. 1.2.1-11 (transl. Dewing, Loeb vol. 7, 32-37).

5 Trinity College Library, ms 0.17.2, fol. 1; Mango 1965 (supra n.1) 305-13 and fig. 1.

6 As recounted by Mamboury, E., “Le Forum de Constantin, la chapelle de St. Constantin, et les mystères de la Colonne Brulée,” Πε1 πραγμένα το ῦ Θ´Διεθωο1 ῦς Βυζ. Συνεδρίο υ (Athens 1955) vol. I, 275–80Google Scholar. Note also d’Alessio, E. Dalleggio, “Les fouilles archéologiques à la colonne de Constantin à Constantinople,” Echos d'Orient 159 (1930) 339–41Google Scholar; Mamboury, E., “Les fouilles byzantines à Istanbul,” Byzantion 11 (1936) 266 Google Scholar; Mango 1981 (supra n.1) 103-10. A photograph of the excavation appears (improperly identified) in Stamatopoulos, C. M., Constantinople through the lens of Achilles Samandji and Eugene Dalleggio (Turin 2009) 150 Google Scholar.

7 For Eusebius's description and a summary of the scholarship, see Cameron, Averil and Hall, S. (edd.), Eusebius. Life of Constantine (Oxford 1999) III, 1–7 Google Scholar: “the Emperor used these very toys [i.e., pagan statues] for the laughter and amusement of the spectator'; 143-44, with commentary on 301-3; note also Bassett (supra n.1) 48-49. Note also comments by Barnes (supra n.1) 24-25, who views the statue as “neither noteworthy nor problematical for Christians”.

8 Bassett (supra n.1) pp. 192-204 includes most references; see also Dagron 1984 (supra n.1) 39-42; Karamouzi (supra n.1) 222-23; and Bralewski, S., “The Porphyry Column of Constantine and the Relics of the True Cross,” Studia Ceranea 1 (2011) 87–100 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

9 Schaff, P. and Wace, H., Scholasticus, Socrates and Scholasticus, Sozomen, Ecclesiastical history in A select library of the Nicene and post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church (Grand Rapids, MI 1952) vol. I, 17 Google Scholar ( PG 67, 33–841 Google Scholar).

10 Hesychios of Miletos, Patria Konstantinopoleos 41 (Bassett [supra n.1] 192).

11 Jeffreys, E., Jeffreys, M., Scott, R. et al., The Chronicle of John Malalas: a translation (Byzantina Australiensia 4, 1986) 321 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

12 Proc., BGoth 1.15 (transl. Dewing 114-15).

13 Whitby, M. and Whitby, M., Chronikon Paschale 284-628 A.D. (Liverpool 1989) vol. 1, 528 and 573 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

14 Mango, C. and Scott, R. (edd.), The Chronicle of Theophanes (Oxford 1997) 125-26 and 222 Google Scholar.

15 Cameron, Averil and Herrin, J. (edd.), Constantinople in the eighth century: the Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai (Leiden 1984) especially 39, pp. 104–5 and commentary on p. 219CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

16 Ibid., translates the term stele as statue. The text refers to the items concealed “κάτωθεν τῆςμεγάλης στήλης”. Following Constantine of Rhodes, ll. 75-79, it more likely indicates the column proper.

17 Berger, A. (ed.), Accounts of medieval Constantinople: the Patria (Cambridge, MA 2013) 78–81 Google Scholar.

18 Monachus, George, Chronikon (de Boor, 1987) 500 Google Scholar (Bassett [supra n.1] 198).

19 Ibid. 500 (Bassett ibid. 198)

20 Grammaticus, Leo, Chronographia (ed. Bekker, , 1842) 87 Google Scholar (Bassett ibid. 198).

21 Ibid. 254 (Bassett ibid. 198).

22 Cedrenus, Georgius, Historiarum Compendium (ed. Bekker, , 1838–1839) vol. 1, 564 Google Scholar (Bassett ibid. 198).

23 Dawes, E. A. S. (transl.), The Alexiad of the Princess Anna Comnena (London 1967) XII.4 Google Scholar.

24 I have no idea what her point here might have been, except possibly to discredit a false omen against her father Alexios.

25 Zonaras, , Epit. Hist. (edd. Pinder, and Büttner-Wobst, , 1841–1897) XIII.17–18 Google Scholar (Bassett [supra n.1]199); see more recently Bianchich, T. M. and Lane, E. N. (transl.), The history of Zonaras from Alexander Severus to the death of Theodosius the Great (London 2009) 155 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

26 Tzetzes, Johannes, Historiarum variorum Chiliades (ed. Keissling, , Leipzig 1827) VIII.192 Google Scholar (Bassett ibid. 199).

27 Nicephoras Callistus, Hist. Eccl., in PG 145, VII.49 (Bassett ibid. 199). For the arches, see Mango 1981 (supra n.1) 107.

28 Majeska, G. P., Russian travelers to Constantinople in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (Dumbarton Oaks Studies 19, 1984) 184-85 and 260–61Google Scholar.

29 As I have discussed elsewhere: “Constantinople and the construction of a medieval urban identity,” in Stephenson, P. (ed.), The Byzantine world (London 2010) 334–51CrossRefGoogle Scholar; “The sanctity of place and the sanctity of buildings: Constantinople versus Jerusalem,” in Wescoat, B. D. and Ousterhout, R. (edd.), Architecture of the sacred: space, ritual, and experience from Classical Greece to Byzantium (Cambridge 2012) 281–306 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

30 Arranz, M., L’eucologio constantinopolitano agli inizi del secolo XI (Rome 1996) 227–51Google Scholar.

31 Livy 26.27.14.

32 Bassett (supra n.1) 69-71; see also Rose, C. B., “Troy and the historical imagination,” CW 91 (1998) 98–100 Google Scholar.

33 Chapt. 39; Cameron and Herrin (supra n.15) 104-5 and 219; for the Artopolia, see Janin, R., Constantinople byzantine (Paris 1964) 95–96 Google Scholar.

34 Dagron, G., Emperor and priest: the imperial office in Byzantium (Cambridge 2003), transl. Birrell, J., p. 50 Google Scholar.

35 Mango 1981 (supra n.1) 109; Berger, K. (ed.), Die griechische Daniel-Diegese (Leiden 1976) 15 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Rydén, L., “The Andreas Salos Apocalypse,” DOP 28 (1974) 211 Google Scholar.

36 Bosio, L., La Tabula Peutingeriana (Rimini 1983) fig. 22Google Scholar; also Talbert, R. J. A., Rome’s world: the Peutinger Map reconsidered (Cambridge 2010)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; http://peutinger.atlantides.org (viewed Feb. 9, 2014). Note comments by Barnes (supra n.1) 24-25, who would like to see the radiate crown as a later addition, since it does not appear in the map image.

37 Ensoli, S., “I colossi di bronzo a Roma in età tardoantica: dal Colosso di Nerone al Colosso di Costantino. A proposito dei tre frammenti bronzei dei Musei Capitolini,” in ead. and Rocca, E. La (edd.), Aurea Roma. Dalla città pagana alla città cristiana (Rome 2001) 66–90 Google Scholar; Platner–Ashby 130-31; see also http://romereborn.frischerconsulting.com (viewed Feb. 9, 2014). Smith, R. R. R., Hellenistic ruler portraits (Oxford 1988)Google Scholar.

38 Johnson, F. P., “The Colossus of Barletta,” AJA 29 (1925) 20–25 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Peschlow, U., “Eine wiedergewonnene byzantinische Ehrensäule in Istanbul,” in Studien zur spätantiken und frühbyzantinischen Kunst. Festschrift F. W. Deichmann (Mainz 1986) vol. 1, 21–33 Google Scholar.

39 Bassett (supra n.1) 201-4 and fig. 21; Bardill (supra n.1) 28-125 and fig. 86.

40 Kantorowicz, E., “Gods in uniform,” ProcAmPhilosSoc 105 (1961) 368–93Google Scholar.

41 Mango 1993 (supra n.1) 2-4.

42 Bassett (supra n.1) 203.

43 Bardill (supra n.1) 28-34, and figs. 17-19; see also http://www.byzantium1200.com/forum-c.html (viewed Feb. 9, 2014).

44 Bassett (supra n.1) 203. Barnes (supra n.1) 24-25 also supports nudity, but views this as representing Constantine as a “traditional Roman emperor”.

45 I thank C. B. Rose for this suggestion.

46 Bassett (supra n.1) 203, following R. R. R. Smith.

47 See most recently Bardill (supra n.1) 84-104.

48 Ibid. figs. 83 and 86.

49 Marlowe, E., “Framing the sun: the Arch of Constantine and the Roman cityscape,” ArtB 88 (2006) 223–42Google Scholar.

50 See Brandenburg, H., Ancient churches of Rome (Turnhout 2004) pl. 45Google Scholar; note also recent comments by S. Ćurčić, “Divine light: constructing the immaterial in Byzantine art and architecture,” in Ousterhout and Wescoat (supra n.29) 307-37.

51 Bardill (supra n.1) 203-17, with prior bibliography.

52 Ensoli (supra n.37) 71-81.

53 Marlowe (supra n.49) especially 226.

54 Mango 1993 (supra n.1) 1-2.

55 Janin (supra n.33) 81-84.

56 Compare to Bardill (supra n.1) figs. 17-18, and http://www.byzantium1200.com/forum-c.html.

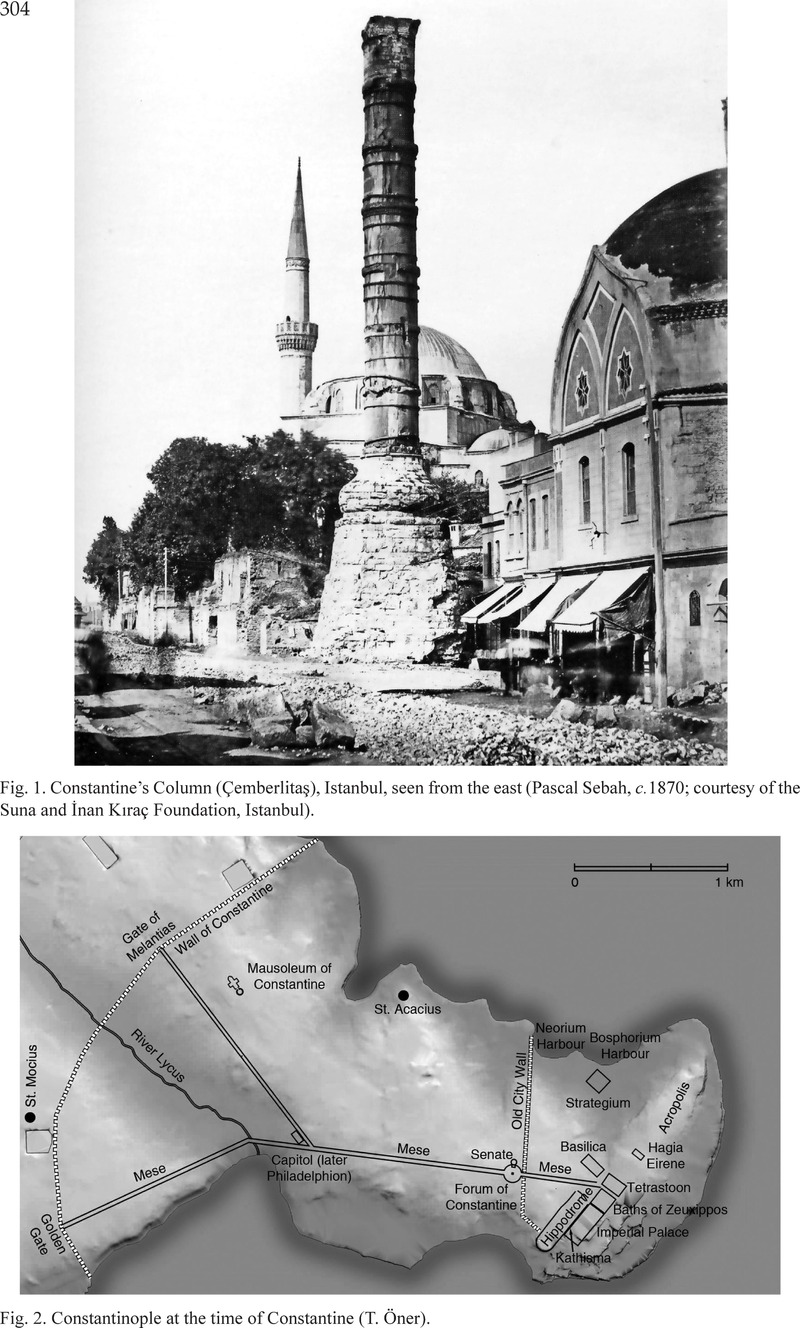

57 I thank T. Öner for his comments on this matter.

58 Alexiad. 12.4.

59 Euseb. 1.43.3; transl. Cameron and Hall (supra n.7) 87; for Constantine’s luminosity, see Bardill (supra n.1) especially 101-4.

60 The via triumphalis actually approaches from the southwest, but the statue must have been turned slightly to relate it to the Forum Romanum, to the north.

61 Manuel’s inscription begins on the W side, so this direction must have been significant for the Column.

62 Mango 1981 (supra n.1) 109.

63 Philostorgius, Hist. Eccl. 2.17 (ed. Bidez, Sources chrétiennes 564 [2013]).

64 Kazhdan, A., “Constantin imaginaire,” Byzantion 57 (1987) 196–250 Google Scholar.

65 See, inter alios, Walter, C., The iconography of Constantine the Great, emperor and saint (Leiden 2006)Google Scholar; and Brubaker, L., Vision and meaning in ninth-century Byzantium: image as exegesis in the Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus (Cambridge 1999) 163–72Google Scholar.

66 Whittemore, T., The mosaics of St. Sophia at Istanbul, the second preliminary report on work done in 1933 and 1934. The mosaics of the southern vestibule (Oxford 1936)Google Scholar; Cormack, R., Writing in gold: Byzantine society and its icons (London 1985) 160–65Google Scholar.

67 Mango 1981 (supra n.1) fig. 1, for possible reconstruction.

68 Cameron and Herrin (supra n.15) passim; Mango, C., “Antique statuary and the Byzantine beholder,” DOP 17 (1963) 55–75 Google Scholar; James, E., “‘Pray not to fall into temptation and be on your guard’: pagan statues in Christian Constantinople,” Gesta 35 (1996) 12–20 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

69 Parastaseis ch. 28; Cameron and Herrin (supra n.15) 88-91; James ibid. 12 et passim.

70 On Byzantine attitudes toward nudity, see Maguire, E. D. and Maguire, H., Other icons: art and power in Byzantine secular culture (Princeton, NJ 2007) 97–134 Google Scholar.

71 Mt. Athos-Panteleimon Monastery, ms. 6, fols. 162v-165v; see Pelikanidis, S. M. (ed.), The treasures of Mount Athos (Athens 1975) vol. 2, figs. 310-16Google Scholar, illustrating the Pseudo-Nonnos commentary.

72 See Mango (supra n.68) 74 with figs. 15-16 and 19 (Cod. Vat. Gr. 1631, pp. 13, 371); note the recent facsimile of the manuscript: El “Menologio de Basilio II”, emperador de Bizancio (Vat. gr. 1613) (Madrid 2005)Google Scholar, and the associated commentary, D'Aiuto, F. (ed.), El “Menologio de Basilio II”, Città del Vaticano, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. Gr. 1613. Libro de Estudios con ocasión de la edición facsímil (Vatican City 2008)Google Scholar. From the paginated manuscript see especially pp. 13 and 371; also, p. 125 depicts St. Cornelius destroying a temple, with statues falling from their columns. My illustrations are taken from the older edition, Il Menologio di Basilio II (cod. vaticano greco 1613) (Turin 1907)Google Scholar.

73 dell’Acqua, F., “The fall of the idol on the frame of the Genoa Mandylion: a narrative on/of borders,” in Crostini, B. and Porta, S. La (edd.), Negotiating co-existence: communities, cultures, and convivencia in Byzantine society (Trier 2013) 143–67 and fig. 2Google Scholar.

74 The only exceptions I know are the Tetrarchic monument in the Roman Forum and the Jupiter Column from Maastricht, both Western examples; for the former, see Bardill (supra n.1) fig. 64.

75 Mango (supra n.68) 74.

76 Delehaye, H., Les saints stylites (Brussels 1923)Google Scholar; for a common image, see Menologio p. 2.

77 Delehaye, ibid.; also Dawes, E. (transl.), Baynes, N. H. (notes by), Three Byzantine saints: contemporary biographies of St. Daniel the Stylite, St. Theodore of Sykeon and St. John the Almsgiver (London 1948)Google Scholar; for an image, see Menologio, p. 237.

78 Theodoret, , Hist. Relig. 2.27–28 Google Scholar; Canivet, P. and Leroy-Molinghen, A. (ed.), Théodoret de Cyr: l’histoire des moines de Syrie (Sources chrétiennes 257 [1977])Google Scholar.

79 Miller, P. Cox, “On the edge of self and other: holy bodies in late antiquity,” J. Early Christian Stud. 17.2 (2009) especially 185–86Google Scholar.

80 See James (supra n.68) especially 18; and Eastmond, A., “Body vs. column: the cults of St Symeon Stylites,” in James, E. (ed.), Desire and denial in Byzantium (Aldershot 1999) especially 98 Google Scholar, who notes the similarity of imperial and stylite columns, but concludes: “Whereas on the imperial column the state stood in for the prototype, at Qalat Siman, Symeon became the image”.

81 Delehaye (supra n.76) 148-69; Menologio p. 208. My thanks N. Marinides for bringing the text to my attention.

82 Mango, C., “A memorial to the emperor Maurice?” Deltion tes Christianikes Archaiologikes Etaireias 42 (2011) 15–20 Google Scholar.

83 Baldovin (supra n.2) 212, 292-300.

84 Mateos, Juan, Le Typicon de la Grande Église (Orientalia Christiana Analecta 165-66 [1962–63] t.2, 200–3Google Scholar; see also Nelson, R. S., “Empathetic vision: looking at and looking with a performative Byzantine miniature,” Art History 30 (2007) especially 493 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

85 My thanks to N. Ševčenko for sharing her unpublished paper “Moving through space: Byzantine processional patterns,” delivered at the Byzantine Symposium held at Birmingham in 2000; see also Baldovin (supra n.2) 220-25. For stational stops at the Forum, see Porphyrogennetos, Constantine, The Book of Ceremonies (transl. Moffatt, A. and Tall, M.; Byzantina Australiensis 18, 2012)Google Scholar with the Greek edition of the CSHB (Bonn 1829), e.g. pp. 28–33 (I.1)Google Scholar; p. 74 (I.10), pp. 164-65 (I.30); Mateos, , Typicon I, passimGoogle Scholar.

86 Book of Ceremonies, Birth of the Virgin: I.1, pp. 28-30; Annunciation: I.1, p. 33 and I.30, pp. 164-66.

87 Ševčenko (supra n.85).

88 Ibid.; Mateos, Typicon I passim; John Baldovin (supra n.2) 292-300.

89 As Ševčenko emphasizes; see Baldovin ibid. 220-25.

90 Book of Ceremonies, II.19, pp. 609–12Google Scholar.

91 See also McCormick, M., Eternal victory: triumphal rulership in late antiquity, Byzantium, and the Early Medieval West (New York 1986) 161–65Google Scholar.

92 E.g., ibid. 154-57, et passim 198-230.

93 Frolow, A., “La dedicace de Constantinople dans la tradition byzantine,” RHistRelig 127 (1944) 61–127 Google Scholar.

94 Ibid. 69-74; Dagron 1984 (supra n.1) 42.

95 Mateos, , Typicon I, 286–91Google Scholar.

96 Delehaye, Hippolyte, Propylaeum ad Acta Sanctorum novembris: synaxarium ecclesiae Constantinopolitanae (Brussels 1902), col. 673Google Scholar.

97 Janin, R., La géographie ecclésiastique de l’Empire byzantin I.3. Les églises et monastères (Paris 1969) 236–37Google Scholar.

98 Macrides, R., Munitiz, J. A. and Angelov, D. (edd.), Pseudo-Kodinos and the Constantinopolitan court: offices and ceremonies (Farnham 2013) 12-13 and 195 Google Scholar.

99 See Lafontaine-Dosogne, J., “Iconography of the cycle of the infancy of Christ,” in Underwood, P. A. (ed.), The Kariye Djami vol. 4 (1975) 226–29Google Scholar.

100 The story apparently originated in oriental paraphrases of the Gospel story in the Syrian tradition; it was incorporated into strophe 12 of the Akathistos Hymn; see Lafontaine-Dosogne ibid. 228.

101 Underwood (supra n.99) vol. 1 (1966) 97-98; vol. 2 (1966) pls. 182-83.

102 Lafontaine-Dosogne (supra n.99) 229 with figs. 53b and 56.

103 Cf., e.g., Menologio p. 274.

104 Such as episodes from the vitae of Saints Cornelius and Nicholas; for the former, see Menologio p. 125; for the latter, see Ševčenko, N. P., The life of St Nicholas in Byzantine art (Bari 1983)Google Scholar.

105 Cutler, A., Transfigurations: studies in the dynamics of Byzantine iconography (University Park, PA 1975) 111–41Google Scholar; R. Ousterhout, “The Virgin of the Chora: an image and its contexts,” in id. and L. Brubaker (edd.), The sacred image East and West (Urbana, IL 1995) 91-108, with additional bibliography.

106 Pseudo-Codinus 195.

107 Bassett (supra n.1) especially 17-36.