In 2017, archaeologists at Pompeii exposed by far the longest tomb inscription ever found at the city, discovered in situ on a monumental tomb just outside the Stabian Gate.Footnote 1 At 183 words, this elogium provided insight into many aspects of the city and its social, economic, and political world.Footnote 2 One clause in the elogium attests to the distribution of baked bread in the city. This note argues that the passage provides new evidence from Pompeii that might answer two longstanding questions. The first is that of the subject of an often-reproduced fresco from Pompeii. Scholars have debated the identity of the main figure in the genre painting, calling him either a baker or a politician – or occasionally a combination of the two. But with no clear comparanda for either, no definitive conclusion has been reached. The second question is the status of the owner of the property on which the fresco was discovered, specifically in terms of his political and social rank and network. Together, the painting and inscription illuminate the mechanics of beneficence at Pompeii and arguably serve to identify the residence of someone in the community who operated in the political networks of the 1st c. CE at a level just below the most elite or politically successful. Let us start with the house and fresco before moving to the inscription.

The house and fresco at VII.3.30

The fresco under discussion was exposed in 1863 in excavations in the tablinum of a domus at VII.3.30, Casa del Panettiere, the House of the Baker, so called after the presumed subject of the painting.Footnote 3

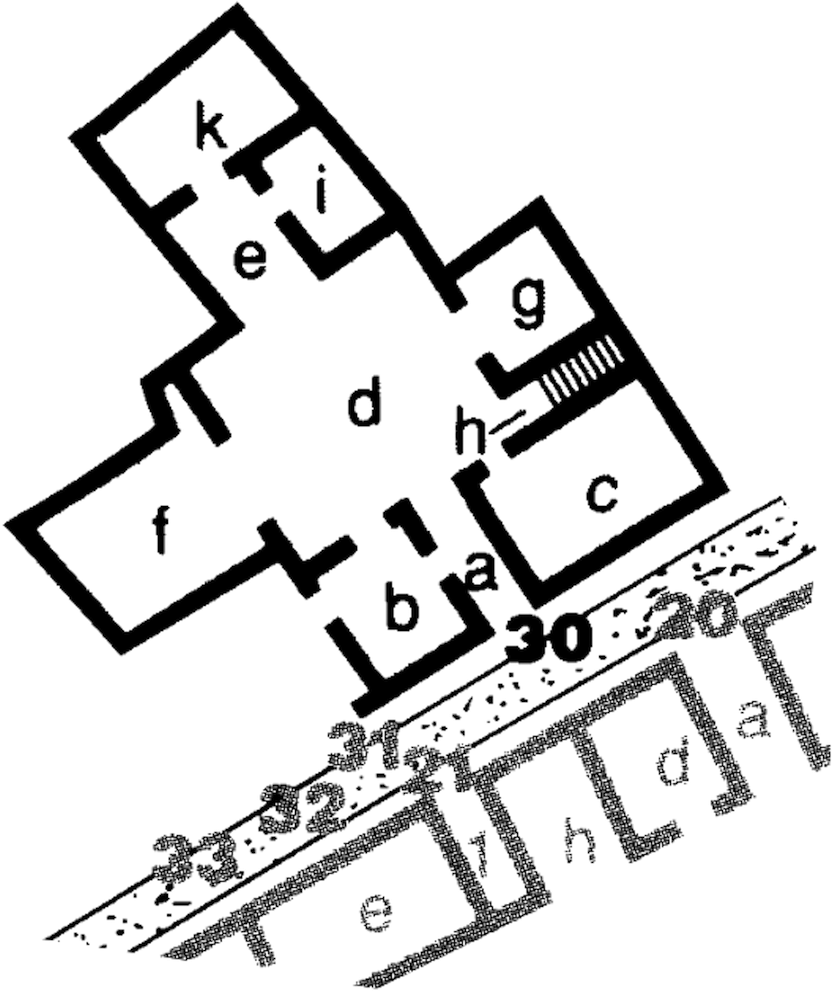

It was painted in situ on the west wall of the tablinum, the only wall unbroken by a door (Fig. 1). The house is located in Region VII, northeast of the forum on Vicolo del Panettiere, which was named after the house and runs a short distance between Vicolo Storto to the west and Via Stabiana to the east. The discovery of an evidently commissioned, unique, non-mythological painting in such a house has been part of the scholarly debate about the house's ownership and the commissioning of the painting. I say “such a house” because as an atrium-style house it is an outlier in a number of ways. First, its size and scale are both small. It has only eight small rooms on the ground floor, with a total area of 211.56 m2. Although the house contains what we might refer to as the “core room set” of an atrium house, with a vestibulum, atrium, and tablinum, it has no rooms that are readily identifiable as alae, cubicula, or triclinia. Furthermore, none of the rooms is large and none is regularly square or rectangular. There seems not to be a 90-degree corner in the entire property. In addition, the arrangement of the rooms lacks any of the symmetry seen in other, larger atrium-style houses. Instead, the house presents a seeming insistence on including the canonical types of rooms that are found in larger houses crammed into this small irregular space in an asymmetrical and rather distorted form. Within the tablinum of this house, the painting was created.

Fig. 1. Plan, House of the Baker, Pompeii (VII.3.30). (After Clarke Reference Clarke2003, fig. 152.)

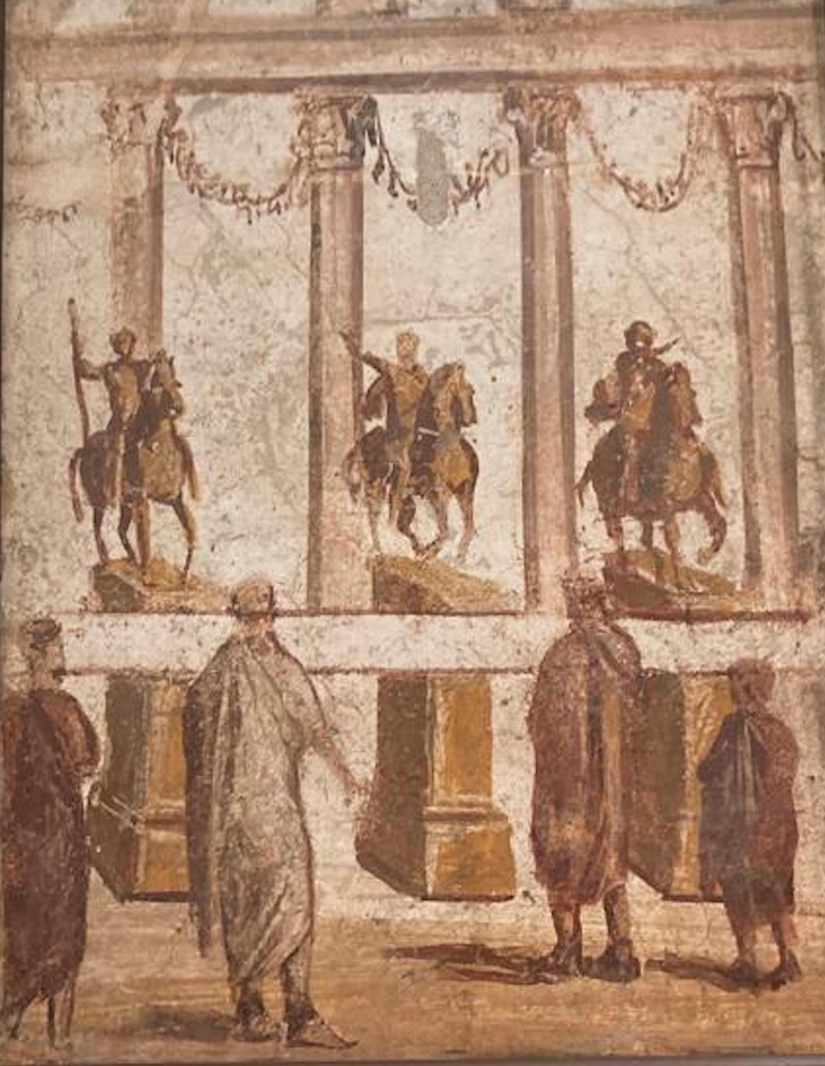

The rectangular painting (Fig. 2), 69 × 60 cm, was removed from the wall of the tablinum almost immediately following excavation and is now in the collections of the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, MANN inv. 9071.

Fig. 2. Bread distribution fresco, MANN inv. 9071. (With the permission of the Ministero della Cultura – Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.)

The painting provides an axonometric view from above and to the right of a scene with four figures and a wooden stall. The stall, carefully painted with the nail heads and the wood grain of its boards depicted, has two shelves behind and a long counter in front. Between these is a male figure wearing a white garment. This may be a tunic or toga, although the bulk given to the garment seems to suggest a toga. He is seated on a raised seat or platform. On the counter and the shelves there are at least 13 stacks containing a great number of loaves of bread piled on top of each other. The loaves are of various sizes but uniform shapes, all consistent with the segmented type found at Pompeii and Herculaneum.Footnote 4 In addition, a wicker basket on the counter to the right of the seated figure contains smaller loaves of bread or buns. The seated man holds out a loaf of bread in his right hand to a group of three people standing in front of the stall, two adult men wearing dark tunics and boots and an adolescent boy on the right in a dark tunic and sandals. All three wear cloaks: the boy and the man on the left have dark cloaks, the same color as their tunics, while the taller man in the center of the group wears a yellow cloak. He raises his right arm to take the offered loaf and stands out from the group because of his bright cloak, height, and position facing the counter. In contrast, the boy and other man are in profile, facing him on his right and left sides, essentially acting as pendent figures focusing the viewers’ attention on the man accepting the loaf. The boy has both hands raised, and his weight is clearly on his left foot as he reaches forward and up towards the loaf of bread.

The depiction of the figures seems to establish their social context. The man in the stall is seated and raised above the standing men to the point where his waist is at head level for the tallest of them. Their visual relationship is similar to a man seated on the rostra or as magistrate on a podium or suggestus, as depicted, for example, in a fresco on the tomb of Vestorius Priscus at Pompeii, where the magistrate is seated above 12 men standing with six on either side of him.Footnote 5 The man seated in the stall is clean-shaven, while the two adult men standing in front appear to have short, close-cropped beards in the chinstrap style. Clothing also sets up what appears to be a deliberate contrast.Footnote 6 The white clothes of the seated man, whether tunic or toga, are visually associated with candidates for office (toga candida), while the short tunics and cloaks of those standing before him are clearly not the togate dress of the local elite in their official capacity, as seen in other frescoes at Pompeii; for example, the fresco on the tomb of Vestorius Priscus noted above. They are, instead, similar to the dress seen on a number of men engaged in various commercial activities in the Forum Frieze, market frescoes from the atrium of the Praedia of Julia Felix (II.4.3) at Pompeii (Fig. 3).Footnote 7 One section of that fresco contains four figures dressed very similarly to those in the subject fresco, including one man in a toga and two adult men and a boy in dark tunics and cloaks.

Fig. 3. Detail of Forum Frieze from the Praedia of Julia Felix, Pompeii. (Photo by Christopher Mural, with the permission of the Ministero della Cultura – Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.)

Whether the scene was intended to be understood as an actual event or a generic representation, the artist has gone to some trouble to give it tremendous verisimilitude. The meaning of the scene has been interpreted variously over the past 150 years.

Almost immediately upon its excavation and removal, it was thought to illustrate a baker or bread seller, hence the name given to the house.Footnote 8 That interpretation held for a number of years, as attested by variations in the name of the house including the House of the Seller of Loaves, Mercante dei Pani.Footnote 9 Later authors emended that interpretation based at least partially on the fresco's location in the tablinum of the house, which was assumed to indicate an association with, if not actual depiction of, the owner of the property. Fiorelli described the scene as an aedile or magistrate distributing free bread to two men and a boy.Footnote 10 Some scholars focus on the activity to draw conclusions about the patron and presumed subject of the painting and not the source of the bread. Della Corte disagreed with the bread seller conclusion and thought this house should be attributed to an anonymous magistrate instead of a baker.Footnote 11 Mayeske, however, returns to the earlier interpretation and refers to the scene as the sale of bread.Footnote 12 Clarke provides a revised interpretation, concluding “the most likely scenario is that he was a bread baker who at a prosperous moment in his life decided to give free bread to the populace.”Footnote 13 This interpretation permits the close association of the types of bread depicted with those actually found at Pompeii. Subsequent scholars seem to follow this blended suggestion with sometimes more or less ambiguous wording.Footnote 14

There are a number of obstacles to developing a consensus solution to the problem of the subject of the fresco. First is the uniqueness of the scene. Nothing else like it has been found at either of the Vesuvian cities, or in fact elsewhere in the Roman world. There are no other frescoes with this precise scene, although there are carved reliefs from tombs that show what we conclude are related scenes of either bread production or grain distribution. For example, the tomb of Naevoleia Tyche and C. Munatius Faustus at Pompeii is illustrated with a scene in which toga-clad magistrates supervise grain distribution to a group of tunic-clad men, women, and children, paralleling the disparate dress of the figures in the fresco.Footnote 15 There is, of course, ample visual and written evidence for civic grain distribution in the Roman world.Footnote 16 The tomb of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces, known as the Tomb of the Baker, outside Rome is decorated with a set of reliefs that seem to document the baking process, with scenes of grinding grain, kneading dough, forming loaves, and baking and weighing bread.Footnote 17 It also features a toga-clad figure, presumably Eurysaces, overseeing tunic-clad workers in a variety of scenes of bread production. It does not, however, show sales or distribution at the end of the process.

The setting of the event in an apparently temporary wooden stall is also a source of uncertainty for interpretation. It is clearly not a permanent bakery as typically found throughout the city of Pompeii, nor is it a bakery with mill and oven and adjacent taberna, another pattern found in the city.Footnote 18 The body language of those receiving the bread, particularly the boy, seems celebratory, or at least animated beyond what might be expected from a daily shopping activity. Notably, none of the recipients carry sacks for merchandise, a common motif in sales scenes.Footnote 19 The scene also does not seem to depict a sale in that there's no obvious money changing hands as portrayed in some shop scenes; for example, on a shop sign from Ostia where a woman sells vegetables and small animals.Footnote 20 The dress and the position of the distributor seem inconsistent with other images of Roman commerce illustrating serving customers. The placement of the distributor not in a shop or workshop, which normally gives context to such commercial figures, is unusual, as is the fact that he appears alone, when many other images of commercial production, such as the Eurysaces reliefs, emphasize the collaborative nature of production.Footnote 21 Finally, the bread is stacked on the front counter, not kept out of reach of the “customers” as was frequently the case for commodities in many other images of sales establishments.Footnote 22

All of these variances from the typical components in the genre of shopping scenes may skew conclusions towards the painting being a magistrate scene. Unfortunately, that conclusion also has weaknesses. For instance, the bread distributor appears alone, with no subordinates or onlookers. That is very unusual for images of local elites in Pompeii or other civic contexts in Roman cities. For instance, none of the frescoes from the tomb of Vestorius Priscus show the deceased alone; he is invariably accompanied by subordinates or spectators.Footnote 23 The same situation is reflected in the relief from the tomb of C. Munatius Faustus at Pompeii and the relief from the tomb of Lusius Storax from Chieti (Teate).Footnote 24 Their public actions are witnessed (and presumably admired and approved of) by their peers. Genre paintings from Pompeii that illustrate private scenes – or social scenes in domestic space – also invariably feature servants, onlookers, or supporters of the elite individuals in them.Footnote 25

Genre paintings may not be the best parallel, as this painting seems to show a specific event. Perhaps more useful in this regard is the fresco of the riot in the amphitheater at Pompeii (MANN inv. 112222), which may also have shown an approximately contemporary event in the city in a specially commissioned work. That painting demonstrates that an actual event, rather than a generic representation, could be the subject of such a domestic fresco. It was found in the peristyle of another modest house, I.3.23, which is slightly larger at 334.97 m2.Footnote 26 In contrast to the bread fresco, it does not serve to promote any elite identity or connections.Footnote 27 The location of the bread distribution painting on a wall in the tablinum is very unusual as that space is almost invariably decorated with mythological imagery.Footnote 28 This is an outlier in what has been termed the “shared Campanian visual culture” characterized by mythological paintings in these spaces.Footnote 29

The physical context of the painting has also led scholars to question whether the main subject should be identified as a beneficent magistrate. As noted, the house in which it was painted is small, cramped, and consists of, at most, eight very small rooms on the ground floor.Footnote 30 And these are poorly laid out for welcoming visitors or proclaiming any sort of elite or pretended or aspired-to elite identity. The Fourth Style decoration has been described as “rather bland,”Footnote 31 and the tablinum, where the painting was found, was small, off-axis, and had only one side wall unbroken by a door allowing for a single central panel painting. The house seems too small for an elite politician at Pompeii, which is part of the reason the painting has been referred to as a “literal work scene” in a house, “the painting of the baker.”Footnote 32 By comparison, the houses of roughly contemporary magistrates are much larger. The house of C. Cuspius Pansa, duovir in 62 CE, at IX.1.22 is approximately four times the size of this house at 1,027.34 m2.Footnote 33 The large house identified as belonging to the early Flavian duovir, M. Epidius Sabinus, IX.1.20, is also considerably larger at 1,244.09 m2 and has been called “one of the city's most notable.”Footnote 34 We can further compare the size of the ground floor of the property to other famous houses, all of which are far larger: Casa dei Vettii (VI.15.1), 1,165.41 m2, House of Octavius Quartio (II.2.2), 2,507.15 m2, House of the Faun (VI.12), 2,952.80 m2, Casa di N. Popidius Priscus (VII.2.20), 1,384.29 m2. The small size of the house is also an obstacle to it belonging to a successful merchant, even of commodities like bread. By contrast, the house of Umbricius Scaurus, the garum merchant, in the same region of the city at VII.16.13, is many times larger at 1,328.42 m2 and apparently more lavishly decorated, creating a personalized commercial identity in domestic space.Footnote 35 There is also an almost complete lack of supporting evidence for bread distribution to a civic population by a baker, candidate for office, or magistrate, which brings us to the new evidence provided by the elogium.

Elogium

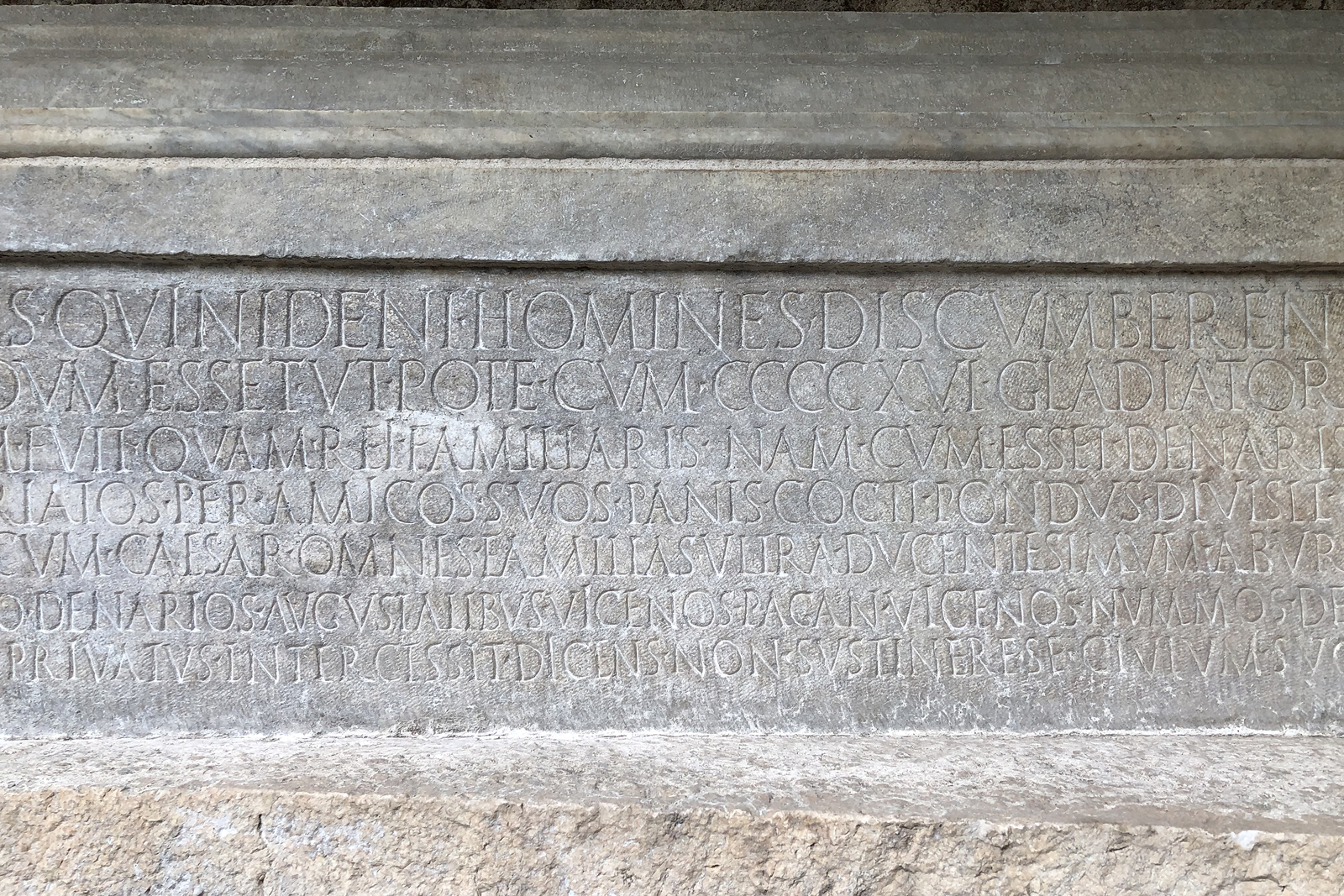

In 2017, during excavations outside the Stabian Gate at Pompeii, excavators revealed a damaged large monumental tomb with the longest inscription yet found at the city (Fig. 4). Referred to by the excavators as an elogium, it is a 183-word epigraph along the side of the tomb facing the extramural road.Footnote 36 The inscription has been described as a biography of the unnamed deceased man. It records a series of events in his life with corresponding and increasing acts of public beneficence, beginning with his assuming the toga virilis and ending with a vote by the decuriones to name him patron of Pompeii, a position which he tells us he declined. Among his generous gifts to the community were a banquet, gladiatorial games and animal hunts, food distributions to the community, and cash distributions to the people, Augustales, decuriones, and pagani.Footnote 37

Fig. 4. Detail of elogium with key passage in line 4: per amicos suos panis cocti pondus divisit. (Photo by the author, upon authorisation of the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Environment.)

The particular passage in the elogium that mentions the distribution of baked bread places it in the context of a grain shortage, in caritate annonae.Footnote 38

ut ad omnes haec liberalitas eius perveniret, viritim populo ad ternos victoriatos per amicos suos panis cocti pondus divisit.

so that this generosity of his should reach everyone, he distributed to the people individually though his own friends a weight of baked bread worth up to three victoriati.

Publications on the elogium provide excellent, in-depth analysis and commentary, which it is unnecessary to repeat here, although some key points need to be addressed. The Latin makes it clear that this distribution is to the populus of Pompeii viritim (individually) – or literally man-by-man – rather than through intermediaries or in some collective manner. The word populus can have a number of meanings, but I think the preponderance of evidence and argument leads us to conclude that here it refers to adult male citizens of Pompeii.Footnote 39 This form of beneficence to the entire community through the male citizens has many precedents, but none for the distribution of baked bread. In fact, the logistics of bread distribution as opposed to grain distribution seem problematic. This raises the question of why one would choose to distribute bread and not grain, the almost ubiquitous choice for food distribution. It has been argued that the decision was based on the desire of the donor to alleviate fraud by distributing food in a form that is more perishable and harder to redistribute for personal gain.Footnote 40 While this argument makes sense, it seems to me that the point of giving bread is rather that it creates a more spectacular, valuable, immediate, and generous gift. And one that is not ordinarily accessible to everyone, especially the poor, equally. The gift is greater here than the grain that would make up the loaves because of the additional cost and technical difficulties of having baked bread for the poorer citizens, who would certainly not have had ovens or in some cases even mills or kitchens to process raw grain. In addition, the generosity is increased by the immediacy of the available bread, perhaps indicating a desire to have the act associated with a specific event, such as an upcoming election or a certain occasion in the life of the donor, of the kind to which so many of his gifts to the community are tied. No preparation or waiting would be needed prior to enjoying this gift. Furthermore, it stands by itself, perhaps unlike grain, which could as easily be stored with other household grain and so lose its standing as a separate gift. References to cooked or baked bread (panis coctus) are very rare in Latin inscriptions. In fact, I can find only one other: an inscription recording one of the Acts of the Arval Brethren from 87 CE refers to it in the context of the dining activities of the Arvals.Footnote 41 The only other possible reference to a bread distribution is provided by a dipinto, one of the electoral programmata from Pompeii.

C(aium) Iulium Polybium / aed(ilem) o(ro) v(os) f(aciatis) panem bonum fertFootnote 42

I beg you to elect Gaius Julius Polybius aedile. He brings good bread.

The reference to panem bonum perhaps refers to a bread distribution either already made by Polybius or promised after his election. The terse nature of these dipinti and the use of the present tense leaves the meaning somewhat open to interpretation. Nevertheless, the epigraphical evidence for civic baked bread distribution is minimal but present at Pompeii.Footnote 43

Intersections between the fresco, elogium, and dipinto

Returning to the fresco, we can now consider the relationship between the three pieces of evidence for bread distribution. It seems certain that the fresco shows a distribution, perhaps the one mentioned in the elogium, perhaps one like it, perhaps one inspired by it, taking place between men. The mention of men is significant because the image in the fresco conforms so closely to the reference to viritim populo in the elogium. While shopping scenes often portray shoppers of either or both genders, the exclusively male group on both sides of the transaction in the fresco is unusual. The answer to the key question of the actual relationship between these men can perhaps be found in the dates of each of the three works and, in the case of the elogium, the date of the inscription versus the date of the distribution, to the degree that these can be determined.

Given the excavation date of the Casa del Panettiere in 1863, nothing that provided a firm date for the house was recorded at that time, although to be fair, such a thing may never have existed. Furthermore, the mural painting was not removed to the museum, which might have helped to more precisely date the decorative scheme of the house, and it has since deteriorated to almost nothing. A few fugitive details survive on the exposed walls, while a few other details are preserved in earlier published works on Pompeian painting. The painting style of the house is generally recognized as Fourth Style, a conclusion with which I agree based on the little remaining decoration I have examined.Footnote 44 The largest in situ element is a wall with the remains of garden painting of the type familiar from other Fourth Style houses, with a fence in the foreground filling the dado and plants behind and above, as seen in better-preserved examples in Villa A at Oplontis or the Casa della Venere in Conchiglia (II.3.3) in Pompeii. Other details of the painting scheme seem clearly Fourth Style, as the published illustrations of wall decor include wall panels with red backgrounds broken by single floating figures and framed by fine line tracery or floral tendrils.Footnote 45 The elements and layout are similar to decoration in the Casa dei Vettii (VI.15.1) and so plausibly from the mid-60s or 70s CE.

The elogium provides two potential dates, the internal date of the documented distribution and the date of the composition of the inscription itself. The overall inscription has a firmer terminus post quem since it refers to at least some events in the aftermath of the 59 CE riot in the amphitheater at Pompeii.Footnote 46 More precisely, one scholar has suggested that the elogium belongs to the tomb of Cn. Alleius Nigidius Maius, a well-known magistrate at Pompeii, and dates to the last year of the city.Footnote 47 As for the date of the distribution itself, that is more relative. It seems to fall within a four-year period during the caritas annonae, which is undated but likely earlier in his career than his major magistracy, a duovir quinquennalis in 55–56 CE.Footnote 48 It is all but impossible to date the grain crisis in Pompeii based on external indicators. Although there was a well-documented shortage in Rome in ca. 42–43 CE and in Corinth in 51 CE, it is clear that the Roman world had neither an integrated grain market nor even a consistent climate, but a series of bioclimatic microregions and small-scale markets.Footnote 49 The fresco seems clearly to post-date both the distribution documented in the elogium and the earliest possible date of the elogium, meaning that the painting may illustrate the elogium distribution, or have been inspired by it or possibly based on it.

The electoral programma naming C. Iulius Polybius and his good bread is, like so many programmata, very challenging to date with any precision. It is one of about 50 painted programmata that mention C. Iulius Polybius, but the only one that references good bread. It has been dated as late as 73 CE and as early as the mid-60s.Footnote 50 The mid-60s date seems more likely given that it refers to him as a candidate for office. Other, presumably later, dipinti use his name to ask the reader to support other candidates, a standard tactic by prominent senior politicians at Pompeii.Footnote 51 That date range is consistent with the occupation and redecoration of the House of C. Iulius Polybius, IX.13.1, the identification of which along the north side of the Via dell'Abbondanza in Pompeii has been generally accepted. It was an older house but like others such as the Casa dei Vettii, redecorated with white ground Fourth Style wall paintings, which along with finds in the house demonstrate continued occupation by the family. The electoral programmata with the name of Polybius along the façade of this and adjacent properties testify to the family's continued political activity into the last years of Pompeii.Footnote 52

Conclusions

All of these dates and data lead to a consideration of approximate correlation or causality and the possible relationship between these pieces of evidence and the people behind them. Of particular significance is the contemporality of the three pieces of rare evidence for bread distribution at Pompeii: elogium, painting, and programma. And since the elogium and the painting may well be contemporaneous, and even refer to/depict the same event, they may provide very rare substantiating evidence for an actual event in the political life of Pompeii.Footnote 53 The question arises of what this inscription tells us about the image and the owner of the house. If this is a “portrait,” it is not an image of a baker but of beneficence. How does the elogium inform the apparent conflict between the size and form of the house and the commissioned personalized painting? If the owner of the house is one of the elected official's amici rather than the official himself, the occasion on which he distributed bread might have been, up to that moment, the most significant event in his public life. It connected him to a more prominent local political figure, possibly Cn. Alleius Nigidius Maius or Decimus Lucretius Valens, and gave him public recognition for beneficence. The elogium may help reinforce the conclusion that the fresco shows an owner of the house or related family member as one of the friends distributing grain. While it is challenging to connect members of political networks in this period, some work has been done tracing the connections of C. Iulius Polybius, for example.Footnote 54

I think the evidence goes further and helps to provide a solution to a problem identified by Bodel and colleagues: “Precisely how these amici assisted in handing out bread is unclear.”Footnote 55 The fresco may show us the answer: friends of the magistrate or candidate were stationed in temporary stalls across the city, literally handing out bread to members of the populus, in this instance men, to whom, Bodel and his colleagues concluded, these benefactions in the elogium were directed. This solution may give insight into the reason for the puzzlingly small size and indifferent decoration of the house. It is not the house of a magistrate but of one of his friends, presumably a group that would include men not quite at the same level as the distinguished duovir, whether Cn. Alleius Nigidius Maius or someone similarly successful in local public office. Is it plausible that a friend of one of the most prominent men in Pompeii would be so modest? I think yes. Verboven concluded that “the term amicus covered both amici pares and amici inferiores or clientes.”Footnote 56 In other words, the term could cover a range of relationships or refer to people of various social and economic statuses, not just peers of similar rank. The three pieces of evidence discussed here help to illuminate the lives of those at the sub-elite level and their participation in this form of beneficence in Roman cities. People not otherwise documented in the programmata, for example, were part of the system of distribution and of political networks in these communities. The house in question perhaps consciously aspires to the homes of the more elite individuals in the community to whom the owner is connected through political networks, referred to allusively on the elogium as amicos suos.

Competing interests

The author declares none