The covid-19 pandemic has led to an increasing centralization of the “health threat” narrative in the discussion of immigration policy, which portrays immigrants as potential vectors for disease, thus potentially justifying their exclusion or expulsion. The sort of story being told in media coverage of covid-19 in the context of immigration can help highlight certain elements of the pandemic and downplay others, foregrounding some policy solutions. In addition, it bears examining how the kind of story being told may differ depending on the type of media outlet in question. Drawing on an analysis of online newspaper coverage both nationally (Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and New York Times) and locally in two border states (California and Texas), we examine the prevalence of two competing frames in media coverage of Latinx immigration and the covid-19 pandemic. The first frames covid-19 as a threat to the nation in the context of immigration, which can be used to justify restrictionist actions such as the use of Title 42 to protect the health of the American people. The second portrays covid-19 as threat to immigrant communities themselves, who are often marginalized and may lack or have limited access to health care. Covid-19 is thus framed as a threat caused by, or as a threat to immigrants themselves. We find over the first year of the pandemic there were significant differences between the two levels of coverage. Local news sources in California and Texas were more likely to frame covid-19 as a threat to immigrant communities, while national coverage more often framed immigration as a public health threat that needed to be regulated in some way. We also find that in some cases national outlets responded within this threat frame to challenge politicians’ claims, undermining the idea that immigration needed to be curtailed. How local and national sources differ in their framing is significant, as research has found that nearly a quarter of Americans relied on state and local news (23%) for information on covid-19, sixteen percent looked to solely to national news outlets, and a majority (61%) drew on both national and local news (Shearer Reference Shearer2020). Therefore, how national and local framing of covid-19 in the context of immigration differs is likely to influence public attitudes toward immigrants and immigration.

Immigration and threat narratives

From the nation’s earliest days, immigration has often been framed by public officials and media as a cultural, economic, or criminal threat to the United States. To date, there have been a variety of studies examining the prevalence and content of these frames, as well as their influence on public attitudes toward immigrants and immigration. This research has shown that media coverage and elite rhetoric tend to portray Latinx immigrants in terms of threat. This is often in the context of criminal behavior but is also in relation to jobs and the social welfare system, as well as to American culture and language (Abrajano, and Singh Reference Abrajano and Singh2009; Brown Reference Brown2016; Chavez Reference Chavez2008; Chavez, Whiteford, and Hoewe Reference Chavez, Whiteford and Hoewe2010; Cisneros Reference Cisneros2008; Collingwood, and Gonzalez O’Brien Reference Collingwood and Gonzalez O’Brien2019; Farris, and Mohamed Reference Farris and Silber Mohamed2018; Fryberg et al. Reference Fryberg, Stephens, Covarrubias, Markus, Carter, Laiduc and Salido2012; Gonzalez O’Brien et al. Reference Gonzalez O’Brien, Hurst, Reedy and Collingwood2019; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Carvalho, Davis and Mullins2011; Santa Ana Reference Santa Ana2002, Reference Santa Ana2013). This tendency on the part of media to frame immigration negatively is not just limited to the United States but has also been found in studies of European media outlets (Eberl et al. Reference Eberl, Meltzer, Heidenreich, Herrero, Theorin, Lind, Berganza, Boomgaarden, Schemer and Strömbäck2018). The framing of immigration by media and elites has in turn been shown to influence public opinion, with those exposed to negative frames more likely to favor restrictionist policies, express anti-immigrant attitudes, or support right-wing parties (Boomgaarden, and Vliegenthart Reference Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2007; Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Burscher, van Spanje and de Vreese Reference Burscher, van Spanje and de Vreese2015; Cargile, Merolla, and Pantoja Reference Cargile, Merolla, Pantoja, Carty, Woldemikael and Luevano2014; Figueroa-Caballero, and Mastro Reference Figueroa-Caballero and Mastro2019; Gil de Zuniga, Correa, and Valenzuela Reference Gil de Zúñiga, Correa and Valenzuela2012; Gonzalez O’Brien Reference Gonzalez O’Brien2018; Haynes, Merrolla, and Ramakrishnan Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016; Masuoka, and Junn Reference Masuoka and Junn2013; Valentino, Brader, and Jardina Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013). While cultural, criminal, and economic threat frames have been widely studied, less attention has been paid to the health threat frame, which in the past played a significant role in discussion of immigration and pushes for restriction (Minna Stern Reference Minna Stern1999). This frame is once again central to the discussion of immigration because of the covid-19 pandemic. The emergence of the virus in Wuhan, China quickly led to racist narratives ascribing poor hygiene and unusual culinary habits to Chinese nationals through rhetoric about “wet markets” and bat consumption (Shen-Berro Reference Shen-Berro2020). President Trump would reference covid-19 as the “Wuhan virus,” “Chinese virus,” and “kung flu” and move to limit immigration from Asia in response to the pandemic (“President Trump” 2020). This narrative of Asian immigrants as a threat to the health of the nation, perpetuated and legitimated by Trump’s rhetoric, would lead to a spike in hate crimes against Asians in the United States (Associated Press 2021). Yet this narrative would not remain limited to Asian immigrants, as it was quickly seized upon by the president, and immigration restrictionists more broadly, to target immigration from Latin America, another issue that was a high priority for the administration. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis blamed “overwhelmingly Hispanic” fieldworkers for the state’s surge in covid-19 in 2020, while Trump touted the border wall as a barrier to the diseased masses in Mexico (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Conarck and Contorno2020; Agren Reference Agren2020).

Globally, the covid-19 pandemic has led to an increase in hostility toward immigrants, migrant workers, asylum seekers, and refugees (Elias et al. Reference Elias, Ben, Mansouri and Paradies2021). Donald Trump used the pandemic to justify restrictionist policies toward Latinx immigrants and asylum seekers, in the name of protecting the nation, all the while ignoring the massive toll the virus was taking on these communities in the United States. The Trump administration was the first to invoke Title 42 not only to prevent immigrants from entering the United States because of the potential public health threat they posed, but also to expel asylum seekers and immigrants from U.S. territory, a practice that has continued under President Joe Biden. This characterization of covid-19 as a problem of, rather than a problem for, Latinx immigrant groups is not the only narrative though. Research has shown that the pandemic has taken a particularly large toll on Latinx immigrant communities (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Fredricks, Woc-Colburn, Bottazzi and Weatherhead2020). This has led to counter narratives highlighting the cost of the pandemic for immigrant communities, migrant workers, and other immigrants in high-risk jobs, as well as for those being held in often crowded immigrant detention facilities (Turcotte Reference Turcotte2021).

Research has demonstrated the significant impact framing effects can have on public opinion, as many form their opinions based on cues from media and political elites (Abrajano, and Singh Reference Abrajano and Singh2009; Boomgaarden, and Vliegenthart Reference Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2007; Cargile, Merolla, and Pantoja Reference Cargile, Merolla, Pantoja, Carty, Woldemikael and Luevano2014; Scheufele Reference Scheufele2000; Scheufele, and Tewksbury Reference Scheufele and Tewksbury2006; Gil de Zuniga, Correa, and Valenzuela Reference Gil de Zúñiga, Correa and Valenzuela2012; Iyengar, and Kinder Reference Iyengar and Kinder2010; Lecheler et al. Reference Lecheler, Bos and Vliegenthart2015; Valentino, Brader, and Jardina Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013; Zaller Reference Zaller1992). While there is a voluminous literature on the framing of immigration in media generally, there have been far fewer studies to-date examining how national and local media framing of immigration varies (De Trinidad Young Reference De Trinidad Young, Sarnoff, Lang and Ramírez2022; Fryberg et al. Reference Fryberg, Stephens, Covarrubias, Markus, Carter, Laiduc and Salido2012; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Carvalho, Davis and Mullins2011; Kim, and Wanta Reference Kim and Wanta2018; Lawlor Reference Lawlor2015; Viladrich Reference Viladrich2019). In the context of covid-19, there are reasons to believe local and national coverage will differ, especially in border states with large Latinx populations where the impact of covid-19 on these communities is likely to be more salient to readers. Past research has found, for example, that Spanish-language news tends to be more balanced on immigration than English-language news (Abrajano, and Singh Reference Abrajano and Singh2009) and that the coverage of Arizona’s SB1070, which would have allowed officers to ask for proof of citizenship during routine traffic stops, in national newspapers framed support in the context of threat more often than did local newspaper coverage (Fryberg et al. Reference Fryberg, Stephens, Covarrubias, Markus, Carter, Laiduc and Salido2012). Yet until recently there was little opportunity to examine how at-risk communities, like Latinx immigrants, would be framed by media in the context of a global pandemic like covid-19.

Local and national framing of immigration

Framing refers to a media process by which issues are explained or organized for the public by mass media sources (Boaz Reference Boaz2005). While there is no work to-date analyzing differences in local and national news framing of covid-19 in the context of immigration policy, there is research on immigration policy more broadly that can help us form some assumptions about the likely differences in these levels of coverage. Fryberg et al. (Reference Fryberg, Stephens, Covarrubias, Markus, Carter, Laiduc and Salido2012) found that location affected how newspapers framed Arizona’s SB1070, a bill that would have allowed officers to inquire into immigration status during routine traffic stops. Branton and Dunaway (Reference Branton and Dunaway2009) found that papers closer to the border were more likely to negatively frame immigration, with Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Carvalho, Davis and Mullins2011) similarly finding that border state newspapers were more likely to negatively frame immigration than newspapers in non-border states. One potential reason why border states may frame immigration more negatively, explains Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Carvalho, Davis and Mullins2011), is that these issues more directly impact these states. They go on to explain that local news sources, unlike national sources, carry an obligation to represent the interests of local communities (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Carvalho, Davis and Mullins2011). Lawlor (Reference Lawlor2015) argues that media coverage of policy issues like immigration may be geographically distinct, as, it is the local towns and cities where new migrants settle. Thus, local and national news sources may vary in how they frame immigration. This makes for the argument that geography, or location, is a relevant variable to consider when examining media effects, framing, and immigration.

While evidence suggests that location matters for local coverage of immigration in terms of border vs. non-border states or proximity to the southern border, the evidence of differences in national and local coverage of immigration is much more mixed. Kim, and Wanta (Reference Kim and Wanta2018) found no difference in coverage between national newspapers like the New York Times or Los Angeles Times, and more locally oriented papers (St. Petersburg Times, St. Louis Post-Dispatch). Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Carvalho, Davis and Mullins2011) found border state newspapers to have slightly more negatively framed articles than national newspapers, but this difference was not large, while Fryberg et al. (Reference Fryberg, Stephens, Covarrubias, Markus, Carter, Laiduc and Salido2012) found national newspapers tended to reference threat in the context of Arizona’s SB1070 more often than local papers. Outside of the United States, Lawlor (Reference Lawlor2015) found no difference in coverage of immigration at the local and national levels in the United Kingdom and Canada.

There are reasons to expect that national and local coverage of immigration in the context of covid-19 will vary, despite the mixed evidence on immigration to date. While immigration is often framed as a broader national issue, the covid-19 pandemic had locally specific impacts on immigrant communities. These are less likely to become a focus of national coverage, as these audiences have been found to be more focused on issues of national significance (Price, and Zaller Reference Price and Zaller1993). Audiences for local news tend to be more interested in issues immediately impacting them, which influences both what is reported and how larger problems are framed (Graber Reference Graber2009). Support for this is demonstrated by Mourão et al. (Reference Mourão, Brown and Sylvie2021), who found significant differences between local and national newspapers in the framing of the 2014 protests in Ferguson. National outlets were more likely to include frames related to police militarization (17%) compared to local outlets (7%), while local newspapers were more likely to feature stories discussing the role of economic inequality in the protests (10.7%) compared to those with a national audience (6.5%).

In the context of covid-19 there are reasons to believe the level of coverage could differ in their framing. First, border states have large Latinx populations, with significant geographic overlap between citizen, immigrant, and undocumented populations. Outbreaks of covid-19 among immigrant populations, or potential outbreaks, would thus be highly salient for the communities served by local newspapers. In states like California and Texas, an outbreak of covid-19 among immigrant populations could have a significant effect on the local economy, as well as potentially lead to increased infection of the Latinx population or other members of the community. Second, local papers are more likely to feature official voices from the area, who may be more inclined to frame covid-19 as a threat to the populations they serve, including the Latinx immigrant population. National newspapers are more likely to feature federal officials, who are more likely to frame the pandemic in broader terms of the threat it poses to the nation, instead of specific communities, which is of less salience to a national audience. These two reasons are also deeply intertwined, as national-level officials focus their attention on aspects of the issues that they care about and on reaching national-level audiences, just as local officials do the same with local-level issues and audiences (Graber Reference Graber2009).

Media coverage and framing effects

Entman’s (Reference Entman1993) defines the framing process, saying: “To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (p. 52). In this study, we examine news stories in which covid-19 and immigration have been tied together or made salient in both local and national news stories. Framing acts as a sense-making device, events and issues “are made sense by” the news source for the readers (Boaz Reference Boaz2005, p. 349). Media frames highlight or focus a receiver’s attention on some aspects of a story or issue in favor of others, helping people make sense of an issue and understand implications and policy solutions (Nisbet, Brossard, and Kroepsch Reference Nisbet, Brossard and Kroepsch2003; Scheufele Reference Scheufele1999). Rather than analyzing framing effects on individuals or the public, we base our analysis in the framing source, or text. The source is one of Entman’s (Reference Entman1993) four framing types: communicator, text, culture, and receiver. In this study, we are interested in the communicator, that is the elite public figures who help build frames; and the text, or the frames themselves as presented in news sources. Elites and then the texts are high up in frame order. Entman (Reference Entman2003) describes a cascading activation model, in which each level of the cascade contains “networks of association” (p. 419). These associations exist among the frames through people and symbols; that is, the words and images within a ‘text.’

Though our analysis is based in the text, we consider the historical context and ways in which the frame within the text may trickle down to the public. Entman’s (Reference Entman2003) original cascade model shows the (1) Administration at the top (White House, State, and Defense), followed by (2) Other Elites (congress members and staffers, ex-officials, and experts); (3) Media (journalists and news organizations); (4) News frames (framing words and images); and finally (5) the public (polls and other indicators). Not only does information trickle down the levels, but lower levels inform higher levels; that is to say, the levels are interdependent. As seen in Figure 1, this model has been more recently re-formed to include the impact of rogue political actors and social media platforms, making room for digitalized affordances (Entman, and Usher Reference Entman and Usher2018). Rather than analyzing all levels, in this study we focus on media text and elite impact. As previously discussed, the Trump administration was vocal across multiple platforms, connecting the virus to specific races, such as calling the virus the “Wuhan virus” and “kung Flu” (“President Trump” 2020). Also, during this time, political elites, particularly on the right, touted the border wall between the U.S. and Mexico as a barrier to covid-19 from Mexico (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Conarck and Contorno2020; Agren Reference Agren2020). Compared to Entman, and Usher‘s (Reference Entman and Usher2018) model seen in Figure 1, our current study remains on both sides of the model, analyzing frame similarities among national and regional news sources, as well as the narratives and counter narratives of threat based on covid-19.

Figure 1. Entman, and Usher’s (Reference Entman and Usher2018) Updated Model

Our work also builds on prior scholarship on emerging controversies over biomedical and scientific issues becoming politicized, as was the case with stem cell research and vaccines for HPV (Gastil et al. Reference Gastil, Reedy, Braman and Kahan2008; Nisbet et al. Reference Nisbet, Brossard and Kroepsch2003). Such research has noted that the bounds of the debate on this issue—in other words, the terms in which it is framed—can lead to some aspects of the topic becoming the focus of public and elite discourse and particular policy options gaining prominence over others (Nisbet et al. Reference Nisbet, Brossard and Kroepsch2003). Frames in this context are essentially neutral: they are the narrative elements of the topic that are highlighted and the lens through which the media and public examine the topic. If elites and media outlets focus on covid-19 as a potential pathogen carried by immigrants coming into a country, that encourages people to see this issue as a debate over the public health risk (or lack thereof) of immigration, rather than the quite different debate over whether covid-19 is a public health risk that is especially harmful to minority, immigrant, and other underserved populations. Though our human-coded content analysis of the media coverage will allow for nuance within these categories, such as the potential for news outlets to challenge or problematize either of these frames, we should note that framing the issue in a particular way helps focus the bounds of the debate within that particular frame—and furthermore, focuses attention on different suites of policy options (e.g., restricting immigration or not) that fit with that frame (Nisbet et al. Reference Nisbet, Brossard and Kroepsch2003). Furthermore, we expect that journalistic norms of ideological and political balance would lead to mainstream news outlets giving space to sources that are positively and negatively valenced within particular frames (Page Reference Page1996). For example, newspaper reporters who are covering Trump administration claims about covid-19 being carried over the border by immigrants might seek out more moderate and liberal sources that will counter such claims to ensure they are providing a balanced presentation of this issue. Again, however, simply using a particular frame focuses the debate on specific aspects of the issue, even when it presents multiple views within that frame (Nisbet et al. Reference Nisbet, Brossard and Kroepsch2003).

Research questions and hypotheses

Because covid-19, and the health threat narrative, became entrenched in discussions of the southern border we analyze papers from national sources (WSJ, NYT, USAT) and newspapers from two border states, California and Texas, that have significantly different politics in regard to Latinx immigration. California is a sanctuary state whose governor, Gavin Newsom, extended financial support to the undocumented community during the pandemic, while Texas has banned sanctuary policies and Governor Greg Abbott controversially issued an executive order directing the Department of Public Safety to turn away vehicles transporting individuals who could pose a risk of covid-19 (Office of Governor Gavin Newsom, 2020; Abbott Reference Abbott2021). Drawing on these sources of media coverage, we seek to answer the following research question:

RQ1: How do local and national news sources differ in their framing of covid-19 among immigrant and migrant populations?

We hypothesize that the frames in the national news will focus on threats to the nation, more broadly, as national news is more likely to draw on narratives from federal officials, such as the President or members of Congress. While regional papers are also likely to cover federal elite narratives, they are also more likely to contextualize these stories for local readers or draw on rhetoric from local elites or opinion leaders. This leads us to propose the following hypothesis:

H1: National news sources will more frequently frame covid-19 as a public health threat to the nation than to immigrant communities.

We expect that local sources will be more impacted by local issues, in this case the impact of covid-19 on sizeable immigrant populations, whether immigrant communities broadly or more specifically immigrant workers in high-risk settings, immigrants in federal detention due to lack of documentation, and other immigrant sub-groups facing pandemic challenges. In communities in border states, which have large immigrant or migrant populations, we hypothesize that the local frame, the health threat to immigrant communities, would supersede the national frame passed down through the White House’s agenda or by other federal opinion leaders. Thus, we hypothesize:

H2: Local news sources will frame covid-19 more as a public health threat to immigrant communities than national news outlets.

Methods

Our content analysis was designed to compare local and national sources to understand how news narrative surrounding the covid-19 virus and immigrant/migrant populations are framed as either public health threats to the nation or to immigrant and migrant communities residing in the United States. The data for this study are based on a content analysis of a sample of news articles from both local and national news outlets. The unit of analysis was an individual news article, a method that has been applied in past studies of political discourse about controversial topics (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Lawrence and Livingston2006; Nisbet et al. Reference Nisbet, Brossard and Kroepsch2003).

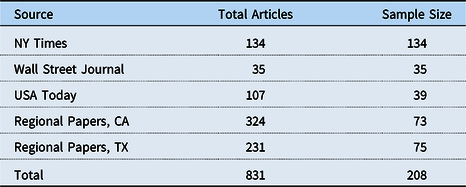

Articles for analysis were selected using NewsBank for local news sources in California and Texas and LexisNexis for national news sources and included articles from February 2020 through February 2021. The article search was conducted via a keyword search of headlines and lead paragraphs using a combination of the following search terms: border, mexic, refugee, immigr, or asyl. The terms were searched for using the [AND] function to also include articles with: illness, disease, covid, or coronavirus. Of note, full words were not used, so as to capture all variations of a word. After reading through the final list of articles, some were removed due to irrelevance. The final corpus of articles used in this paper included 208 articles representing national news stories from the politically conservative Wall Street Journal (WSJ, n = 35), the comparatively liberal New York Times (NYT, n = 134), and the moderate USA Today (USAT, n = 39), to ensure we had ideological diversity among our national outlets of study in addition to covering three of the largest newspapers by circulation in the US, a practice that has been used in past research on similar topics (Gonzalez O’Brien et al. Reference Gonzalez O’Brien, Hurst, Reedy and Collingwood2019; Mourão et al. Reference Mourão, Brown and Sylvie2021). We analyzed the entire corpus of relevant news stories from those three outlets.

To get a comparable local news dataset that is reasonable for a group of multiple human coders to accomplish, we then sampled 73 articles from the search results of local news sources in California (total n = 324) and 75 from those in Texas (total n = 231) for a total of 148 local news articles. In keeping with best practices for content analysis (Lacy et al. Reference Lacy, Watson, Riffe and Lovejoy2015), the local news articles were sampled using interval sampling within the full corpus of results, with an eye toward also selecting a diverse pool of news sources, including large (e.g., Houston Chronicle, San Diego Union Tribune) and small outlets in both states and coverage of different geographic regions of the states (see Appendix 1 for a list of the local newspapers and article count for each in the final sample). This analysis covered more than a quarter (27%) of the full corpus of text in the local news database. Once the final articles for coding were selected, a code book was made and training was conducted, along with a test of interrater reliability. Table 1 below shows the total number of articles from each source, as well as the sample size. Figure 2 shows the location of the local newspapers included in the analysis. Sources are further broken down by the location’s political leaning based on 2020 county election results.

Table 1. Sample Sizes by Source

Figure 2. Local news sources coded by county voting patterns (Red = Republican; Blue = Democratic).

Figure 2 considers the geographic and geo-political landscape of local newspapers. Grimm, and Andsager’s (Reference Grimm and Andsager2011) research suggests that the geo-ethnic contexts in which local newspapers exist, that is, the community communication infrastructure, should be taken into account by researchers when analyzing how and why frames occur and vary between local and national levels. As Figure 2 demonstrates, most of the papers in Texas are based in conservative-leaning areas, while in California we find most local newspapers based in liberal-leaning areas. This allows us to determine whether local partisanship affects the frame chosen.

Coding procedures

Before beginning the analysis of articles, it was important to create an initial codebook. Traditional content analysis requires human decision-making regarding unitizing, followed by assigning each text unit a code (Krippendorf Reference Krippendorff2004). Unitizing can be broken down by line, utterance, paragraph, page, or article. The research team decided to unitize coding by full article, rather than by paragraph or line-by-line coding. This allowed for a more holistic view of the articles and is in keeping with prior scholarship examining political discourse around a particular issue (e.g., Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Lawrence and Livingston2006). The following codes were included in the analysis: public health threat to nation (1), public health threat to immigrant communities (2), public health threat to both (3), and public health threat to other (4), with each article being sorted into one of these coding categories (Krippendorf Reference Krippendorff2004).

The first two coding categories, (1) and (2), were used to describe public health threats to either the nation or to immigrant/migrant communities. To be coded as (1) or (2), over half of the relevant article text had to lean one way or the other. The first category, public health threat to nation (1), was to be used for articles discussing immigrant and migrant groups in relation to the covid-19 virus, in respect to: how the group is a threat to the United States, how the group is spreading the virus in the United States, or how the United States needs to guard against potentially infected immigrant or migrant groups entering, residing in, or being detained in the country. The second category, public health threat to immigrant communities (2), was used for articles discussing immigrant and migrant groups in relation to the covid-19 virus, in respect to: how the group is especially susceptible to the virus due to lack of vaccines, outreach, related health inequities, or community distrust of government services; virus susceptibility to the community due to lack of trust; disease spread in holding facilities impacting migrants and asylum seekers being held at the border; disease spread among immigrant communities in working facilities, such as meat packing plants and farms, specifically impacting immigrant or migrant communities; immigrant or migrant community disease threat due to specific cultural practices, or virus spread in U.S. towns or regions with a large immigrant or immigrant-derived population (e.g., the Rio Grande Valley region). To be coded as (2), the article must focus on the primary health threat being to immigrant or migrant populations.

The third coding category, public health threat to both (3), was used when there was an equal distribution of relevant article text in relation to immigrant and migrant groups and the covid-19 virus in relation to both a health threat to the nation and a health threat to immigrant or migrant communities in the United States (e.g., an equal number of paragraphs in the article focused on both health threats). These articles may have included multiple sides of an argument or equal coverage of immigration policy, or how immigrant groups are spreading the virus to both the immigrant community and the broader American public. If the majority of the article fell under one of the previous categories, (1) or (2), with only passing mention of an instance falling under the opposite category, the article would not be coded as (3), but rather, it would be coded as the category that the article mostly pertains to: (1) or (2). We should note that the code “Threat to Both” was rare, on the order of 7–9% of articles coded at the national and local levels.

The final coding category, public health threat to other (4), was only to be used with the article discussed immigrant and migrant groups in relation to the covid-19 virus, in a context not dealing with the United States, the broader United States public, or with immigrant or migrant communities themselves.

Before conducting interrater reliability, coders worked with 10 articles together for training purposes and to agree on the coding protocol. Next, a basic test of interrater reliability following percent agreement (P A) was calculated using an additional 25 articles. Syed and Nelson (Reference Syed and Nelson2015), percent agreement for interrater reliability is an appropriate and straightforward method, utilizing ratio of agreement. For the initial (n = 25), (P A) = 88%. Coders worked independently and took notes on their coding decisions. During this time,coders met two times to discuss coding and disagreements. Additional changes were made to the code book and to the shared notes for coding based on these discussions. For example, coders noticed the occasional appearance of repeat articles. Following a team discussion, coders decided to include the articles that were repeated, or that were duplicates of a previous article, but that showed up in different publications or on different dates. We contended that in the case of local news organizations, some large companies own multiple local sources; thus, it makes sense that they may use duplicate stories. Likewise, local news sources may also pull from Associated Press (AP) articles. Ultimately, these articles either showed up in different news sources and were thus read by different readers, or they showed up on different dates, for example a day later, and could also have different readership. Therefore, the frames were still counted as being disseminated to different local audiences. Only 11 total articles were repeated, all in the sample of local coverage from CA and TX. Once training and testing of interrater reliability was completed, articles were split roughly equally between the two coders. Coders included in their coding logs the following information: article identification code; the code category (1, 2, 3, or 4); notes that may be relevant for future analysis, such as repeat article, and the title of the article.

Results

We were not interested in positive versus negative framing of these stories for multiple reasons. Due to journalistic standards, stories are often framed in both a positive and negative light, as well as with neutral valences (Page Reference Page1996). While frames may tell us how to think about a political issue (Entman Reference Entman1993), they don’t necessarily have to do so in a way that is overtly only positive or negative. Our research question asks how local and national news sources differed in their framing of covid-19 among immigrant and migrant populations (RQ1). The results of our content analysis help answer this question. The national media did substantially follow the framing of this issue as one of immigrants potentially being a public health threat. In short, the argument by the Trump administration that immigrants could bring the coronavirus with them across the border was quite common in our sample. For example, this article from USA Today in June 2020 focused on concerns from officials in the departments of Health and Human Services and Homeland Security about potential spread due to immigration from Mexico:

Top federal officials are privately exploring whether Latinos are to blame for regional spikes in new coronavirus cases, asking in internal communications if Mexicans could be carrying the disease across the border, fueling domestic outbreaks (Murphy, and Stein Reference Murphy and Stein2020).

However, national outlets also communicated a great deal of skepticism and critique of this argument, both in opinion content (e.g., op-eds, editorials) and in hard news coverage. For instance, one NYT article explicitly tied the administration’s pandemic actions to its political goals of restricting immigration. They note the public health threat cited by Trump and other officials who claimed, “the latest measures are needed to prevent new cases of infection from entering the country,” but also point out the history of previous “public health measures” and the likely political cover this was giving the administration to restrict immigration:

The idea that immigrants carry infections into the country echoes a racist notion with a long history in the United States that associates minorities with disease. The federal law on public health that (Trump official) Mr. (Stephen) Miller has long wanted to use grants power to the surgeon general and president to block people from entering the United States when it is necessary to avert a “serious danger” posed by the presence of a communicable disease in foreign countries (Dickerson, and Shear Reference Dickerson and Shear2020).

As we anticipated, media coverage that stayed within the threat to the nation frame was often balanced, in keeping with norms of journalistic balance among newspaper outlets in the US that encourage presenting both or multiple sides within debates (Page Reference Page1996). However, it is important to note again that this coverage was still operating within the general frame of public health threat to the nation, which could focus attention on immigration policy over options that would address health disparities, for instance.

In addition to these findings, we note that much of the coverage of the intersection of immigration and covid-19 was sympathetic towards immigrants. For example, this article about the pandemic hitting south Texas Latino communities very hard was in the NYT, and was like some local coverage in local Texas news outlets in its discussion of the challenges faced in immigrant communities:

In the Rio Grande Valley, more than a third of families live in poverty. Up to half of residents have no health insurance, including at least 100,000 undocumented people, who often rely on under-resourced community clinics or emergency rooms for care. More than 90 percent of the population is Latino, a group that is dying from the virus at higher rates than white Americans are (Dickerson, and Addario Reference Dickerson and Addario2020).

Turning next to our hypotheses, we first argued that national news sources would more often focus on the health threat to the nation, indexing their coverage to elite frames—either to cover or critique that argument by the Trump administration (H1). As Figure 3 demonstrates, this hypothesis was supported: More than half (50.96%) of the national articles were coded as focusing on the threat to the nation, compared to 32.21% being coded as focusing on the threat to immigrants. The remaining articles were either coded as a threat to both (9.13%) or to other (7.69%). Compared to local papers, national outlets were more likely to frame covid-19 as a health threat to the nation, x 2 (1, N = 356) = 20.48, p < .001.

Figure 3. Framing of Covid-19 in Nationally Circulated Newspapers

National news coverage of this issue often cited arguments from administration officials and from Trump himself discussing the “threat” of immigrants bringing the virus into the US to justify their border crackdowns, such as the shutdown of legal asylum requests:

“The threat we face from outside our borders, from this global infectious disease, highlights the need now more than ever before for border security,” said Mark Morgan, the acting commissioner of Customs and Border Protection (Shear, and Kanno-Youngs Reference Shear and Kanno-Youngs2020).

However, news coverage often pushed back on this argument within the threat to nation frame, as in this example from a NYT article about border wall construction continuing despite shutdowns in many other segments of the economy:

“We will do everything in our power to keep the infection and those carrying the infection from entering our country,” he said at a campaign rally in February. But epidemiologists say that a wall would do little or nothing to stop the virus, which initially entered the country via infected travelers who arrived on airplanes and cruise ships (Romero Reference Romero2020).

Though there were a far smaller number of articles from both the conservative-leaning Wall Street Journal and more moderate USA Today on immigration and covid-19, we did compare the three outlets to determine if there was any significant difference in how left-leaning, moderate, and right-leaning national news sources framed the pandemic in the context of immigrant communities. Somewhat surprisingly, we found no real difference in the percentage of articles framing immigration as a public health threat between the NYT and WSJ, with approximately 54% of both New York Times and Wall Street Journal articles framing the pandemic in this manner. There were slightly larger differences in the framing of covid-19 as a threat to immigrant communities, with approximately 30% of New York Times articles referencing this frame, whereas 20% of articles from the Wall Street Journal did so. However, this difference was not statistically significant, x 2 (1, N = 269) = 1.34, p < .25. The WSJ also had a larger number of articles that were coded as threat to other (17%) than the NYT (∼6%).

In the case of USA Today, the numbers initially looked similar to what we expected to find with local papers, with 35.9% utilizing the threat to nation frame, and 51.28% portraying covid-19 as a threat to immigrant communities. This seemed to contradict H1, even considering the relatively small number of articles in USAT. Digging a little deeper into the corpus, we found that the online archive included articles from both the national desk, as well as from local papers that were part of the USA Today network. This gave us the opportunity to look at national and local framing within the same media company, so we went back through and coded the articles as being from either the national desk or a local affiliate. Figure 4 demonstrates when these were separated, USAT articles from the national desk looked very similar to the NYT and WSJ, with 43% framing covid-19 as a threat to the nation and 39% as one to immigrant communities. Though this is lower than the 54% for the NYT and WSJ, threat to nation was still the most prevalent frame, which is in line with H1.

Figure 4. Framing of Covid-19 in Nationally Circulated Newspapers, USAT National Only & USA Today National & Network Affiliates

While there was variation between the frame referenced by articles from the national desk and local affiliates, we ultimately included all the USAT articles in the national sample for comparison to local outlets because these were part of USAT’s coverage. The difference between national and local frames remained significant at p<.001 even with the inclusion of the full corpus of USAT articles.

In our second hypothesis, we posited that local news sources, with their connections to and knowledge of their communities, would focus more on the threat to immigrants and immigrant communities than national news sources (H2). This was also supported: Approximately sixty percent of local articles were coded as focusing on the threat to immigrants, while less than a third (27%) focused on the threat to the nation. The difference between local and national framing of covid-19 as a threat to immigrant communities was significant at the p<.001 level based on a chi-squared test, (1, N = 356) = 27.39.

As Figure 5 illustrates, there was little in terms of regional differences between sources from California and those from Texas. In California, 58.67% of local news articles framed covid-19 as a threat to immigrant communities, compared to 59.21% of those in Texas. A chi-squared test found no difference in the framing of covid-19 as a threat to immigrant communities between TX and CA-based papers, x 2(1, N = 148) = .0012, p<.97. Articles from Texas news outlets were slightly more likely to frame immigration as a public health threat to the nation, with 28.95% utilizing this narrative. In California this was referenced less often, with 24% of articles drawing on this frame. This difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 5. Framing of Covid-19 in Local Papers (CA & TX)

Many local outlets in the border states of California and Texas cover areas that are home to border crossings, of course, as well to immigration detention facilities; these locations were often cited in coverage of the pandemic. For example, one article in the Riverside (CA) Press-Enterprise focused on an ACLU lawsuit over the threat faced by people held in an immigration detention facility in the area:

Conditions in the Adelanto ICE Processing Center in San Bernardino County — including inadequate sanitation and beds placed too close together — provide an “ideal incubation” opportunity for coronavirus, according to a federal lawsuit filed Monday by six immigrant detainees currently being held in the center (Kopetman Reference Kopetman2020).

Such articles about immigrant detention facilities were quite common in the sample, with most focusing on the threat to the migrants being kept there in crowded conditions. However, some articles also noted the threat to US immigration and border enforcement personnel and other American citizens in the area. One interesting exception to this pattern was from another article about the Adelanto center, this one from the Barstow (CA) Desert Dispatch. It extensively quoted a state legislator representing the area who referred to ICE detainees as “Californians,” rather than as distinct from US residents:

“During the covid-19 pandemic, Californians incarcerated in these for-profit, private immigration detention centers are at unacceptable heightened risk of contracting the virus and spreading it to other detained Californians as well,” he added. “They risk severe health consequences. We must stop ICE transfers to protect the health, safety and welfare of all Californians (Plevin Reference Plevin2020b).”

In addition, local articles in both California and Texas often provided a nuanced view of the US-Mexico borderlands and covered the pandemic as an issue affecting people on both sides of the border, as well as those who may live on one side but have strong connections on the other (though these were not always coded as “Threat to both” articles). For instance, one article in the El Paso (TX) Times discussed the impact of the pandemic on maquiladoras, factories in Mexico that export their products to the US, navigating a complex world of regulations and shutdowns:

The adjustments maquiladoras had to go through to reduce the spread of covid-19 might need to be considered in the long term, Fullerton said. For Farell and other companies, it meant following covid-19 regulations to keep employees in their warehouses, transportation sites and administrative offices in El Paso and Southern New Mexico safe, while also following a different set of rules for their factories in Juárez (Martinez Reference Martinez2020).

Other articles discussed the many people who live in Mexico and commute to work in the US, or vice-versa, as well as the many US citizens who have settled in Mexico, and the impact of the pandemic on these cross-border residents and on the hospitals and medical systems that serve them. An article in the Barstow (CA) Desert Dispatch explained the complex nature of the border community and how it was leading to problems with hospitals in the region filling up:

Economically and culturally, Imperial County and the Mexicali Valley have long been one binational region, divided by a fence…The pandemic is underscoring that the border region shares health challenges, too. “Diseases don’t respect borders as much as we might wish,” said Dr. Jess Mandel, chief of the division of pulmonary, critical care and sleep at UC San Diego Health (Plevin Reference Plevin2020a).

As we hypothesized, the story of the pandemic’s impact in these local outlets was primarily focused on immigrant and migrant people and related communities, within the frame of a threat to immigrant communities, unlike framing at the national level. This suggests that reading papers from national or local outlets could activate different policy frameworks for understanding and addressing covid-19 in the context of immigration or immigrant populations. At the national level, the framing of covid-19 is largely related to questions of openness or restriction of immigration. This situates the discussion in the broader discussion of U.S. immigration policy. At the local level the framework is more public health-oriented, suggesting solutions more related to health policy, such as vaccination drives or reducing crowding in detention facilities. While this is beyond the scope of the current study, the impact of these different frames on public opinion is a fruitful path for future research.

Discussion

Recall that framing is a media process where issues are selected and “made sense of” for the reader. Entman (Reference Entman1993) defined framing as a process, “to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (p. 52). In the case of our study, we analyzed national and local sources from two border states, California and Texas, and found they differed in their framings of immigration and covid-19 as a health threat. Based on this frame building, it would be expected that frames would differ between national sources and local sources. Who the public is shapes the frames that are ultimately selected, and for those in border states immigration is both highly salient and something that has a direct effect on their communities, leading to not only more coverage of covid-19 and immigration but also different frames, as we have shown in this study (Entman Reference Entman2003; Branton, and Dunaway Reference Branton and Dunaway2009). These sources may also focus on local issues, such as conditions in detention facilities, more than national-level political issues like federal immigration policy. National news sources framed immigration as a health threat to the nation during covid-19 significantly more often than local news sources, while over half of the local news sources framed covid-19 as a health threat to immigrant communities.

As we noted in our literature review above, the fact that many national news sources provided counter-arguments to the Trump administration claims of a pandemic threat posed by immigrants does not change the fact that a large majority of this coverage was still operating within the frame of covid-19 and immigration as a health threat to the nation. Though policy discourse is beyond the scope of the present study, we should note that the proliferation of this frame likely led to policy debates on covid-19 response being dominated by border control policy options, in favor of policy responses to the disproportionate health effects being felt in immigrant communities, such as mask mandates and support for workers in higher-risk jobs or people with covid-19 risk factors, or in neighboring countries in Latin America with lower-resourced health systems.

While the local sources did have a higher percentage of sources framed as a health threat to immigrant populations, both included a large number of stories which framed immigrants and immigration as a health threat to the nation over the first year of the pandemic. When we consider who makes the frames, political elites, government entities, and mass media are closely connected in a cascading system of information dissemination and interpretation (Entman Reference Entman2003; Entman, and Usher Reference Entman and Usher2018). During the Trump administration, when anti-immigration policies and the construction of a wall along the southern border were high on the agenda, it makes sense that the narrative of immigrants as a threat would cascade down to both local and national sources. In many ways, covid-19 helped to push the nationalistic and protectionist immigration policies of the Trump administration by providing another threat narrative and one that was both less abstract and more immediate than the cultural, criminal, or economic frames. Our findings suggest that local communities in border states were getting exposed to news frames that shone a light on the problems immigrants faced during the pandemic, perhaps helping counter the anti-immigrant rhetoric being pushed by the administration.

We must acknowledge that this study had multiple limitations. First, it utilized content analysis using human coding. This methodology has long been used to analyze news media but, by nature, meant that fewer articles can be analyzed than through machine coding. However, this method of coding does allow for a more nuanced understanding of the articles and a broader approach. Related to article numbers, this study was limited by the number of articles that fit the research domain. Simply put, we had fewer articles during the first year of the pandemic related to immigration and covid-19 than expected and ran into the problem of repeated stories. Because many local news organizations are either owned by the same company or pull from Associated Press (AP) articles, we noticed repeat articles in our analysis. We argue that this is not problematic, as the stories, as well as the frames, are being disseminated to different local audiences.

This research is ultimately meant as a jumping off point for future work, which could examine more explicitly ideological outlets (e.g. cable news, blogs, etc.) that are less concerned about journalistic norms of balance, as well as political elite discourse and policy debates that are likely more openly partisan. Additionally, this study focused on the first year of the pandemic and future work could examine how these narratives, at both the local and national levels, shifted over time. More research is also needed to determine how alternative framings of the health threat narrative influence public opinion and this project is part of a study series that will focus on various parts of a larger story: how blame has been placed and stories twisted in the era of covid-19, revitalizing the health threat narrative, and providing restrictionists with another tool to use in the battle over immigration policy.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2023.14