Republican Glenn Youngkin’s victory over Democrat Terry McCauliffe in the 2021 Virginia Gubernatorial election raised an important question for the study of American politics and policy. During the statewide election campaign, Youngkin made the promise to ban critical race theory (CRT) from schools “on day one.Footnote 1 ” As election day grew closer, anti-CRT messaging became a central part of his campaign. He won by a slim 2% margin.Footnote 2 According to a Fox News exit survey of Virginia voters, 1-in-4 identified critical race theory as the single most important reason that brought them to the polls.Footnote 3 How does critical race theory, a rigorous line of legal thought taught in the corners of America’s most prestigious law schools, become a policy issue that helps decide a statewide election?

To influence elections, critical race theory must have reached a high level of public salience. However, given its technical nature, very few Americans likely understand its nuances. CRT, therefore, illustrates the important distinction between policy salience and policy knowledge. Beyond CRT, it seems clear that the American public’s recognition of salient policy issues is driven by politics; be it campaigns, media coverage, or on-the-ground organizing. Policy recognition, however, typically gets conflated with political knowledge. As a result, we know less about how the public comes to recognize policy issues and form policy preferences when they recognize a policy, but the overall knowledge of the policy issue is relatively low. I argue that members of the public lacking knowledge on an issue will take strong positions, nonetheless, when they are exposed to policy branding.

The argument responds to a larger question of how the public forms policy preferences. The modern literature in political science largely looks to media effects in explaining policy knowledge, policy positions, and the public’s acceptance of misinformation (Iyengar and Kinder Reference Iyengar and Kinder2010; Guardino Reference Guardino2019; Hochschild and Einstein Reference Hochschild and Einstein2015; Jerit and Zhao Reference Jerit and Zhao2020). The other leading explanation is elite messaging cues, which often intersects with access to (and therefore influence on) news media. However, this is but one form of the way in which politics shapes the public’s ideas of policy. I argue that a parallel pathway is through what I term here as policy branding.

I define policy branding as instances in which political agencies such as (but not limited to) political parties strategically construct a narrative around a policy issue. The notion that branding is a way to understand party behavior is far from new. Decades of research on American politics has looked to the concept of branding to explain the behavior of parties enacted through campaigns, elections, and policymaking (Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005; Reference Cox and McCubbins2007; Cox Kousser and McCubbins Reference Cox, Kousser and McCubbins2010; Clark Reference Clark2012). However, political scientists have largely thought of the relationship between parties, policy, and branding as flowing in one particular direction. We know that parties take positions on policies to shape a party’s brand. That is party branding. However, party branding is most effective when parties take positions on highly salient political issues of which voters, on average, have a baseline understanding. How does branding work when the public has little knowledge on the issue?

My concept of policy branding addresses this gap. I am arguing that policy branding occurs when parties strategically brand policy issues in which the public’s average comprehension level is relatively low. Parties use policy branding to create public support (or opposition) for an issue that can strengthen the party’s brand. I argue that critical race theory, as an education policy issue, shows us clear evidence of policy branding. I provide evidence of policy branding by fielding original survey experiments around public support for antiracist teaching, which is the curricular education reform issue at the core of the policy debate (and misinformation) surrounding critical race theory. I leverage the policy issue of antiracist teaching and the policy branding of it as critical race theory by randomly assigning half of the survey participants to indicate their level of support for antiracist teaching when termed as critical race theory. I find evidence that support for antiracist teaching significantly declines when framed as critical race theory.

Theoretically, I argue that policy branding relies on existing political cleavages. Parties engage in policy branding to leverage gaping political divides. These divides tend to be rooted, not in policy disagreements but cultural and value-based messaging. Existing research in American politics on race and ethnicity come together to establish how routinely negative cultural and/or value-based assumptions about race operate as arguably the deepest source of the racial divisions (Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001; Avery and Peffley Reference Avery and Peffley2003; Hutchings Reference Hutchings2015; Masouka and Junn Reference Masuoka and Junn2013; Wilson and Brewer Reference Wilson and Brewer2013; Tesler Reference Tesler2020; Nuamah and Ogorzalek, Reference Nuamah and Ogorzalek2021). More specifically, white in-group desires for preserving certain values and norms often become the outward justification for embracing racially regressive ideologies and public policies. The branding of antiracist teaching and curriculum as critical race theory aligns with this tradition of race and ethnicity operating as a pre-existing political cleavage that heavily influences how Americans think about some of the most salient public policy issues.

Partisan branding

Branding has become a central concept to the study of politics. Cox and McCubbins (Reference Cox and McCubbins2007) argue that political parties have incentives to behave like cartels and, by doing so, there is motivation to engage in branding. In their model, a party’s brand is its reputation, a reputation rooted in legislative accomplishment. Party brands, therefore, rest upon the policy behavior of parties. Aldrich (Reference Aldrich1995) precedes them by also arguing that parties are amorphous institutions that can be shaped and remade in order to create the proper “brand name” that politicians need to increase their likelihood of election (or reelection). An entire sub-literature has since emerged establishing the importance of branding to the behavior of political parties, both in the USA (Bloch Rubin Reference Rubin2017; Cox and Rosenbluth Reference Cox and Rosenbluth1993; Dewan and Squintani Reference Dewan and Squintani2016; Koger, Masket and Noel Reference Koger, Masket and Noel2009; Thomsen Reference Thomsen2017) and around the world (Adams, Ezrow, and Wlezien Reference Adams, Ezrow and Wlezien2016; Lupu Reference Lupu2016).

This line of argument uses the concept of branding to establish a clear relationship between political parties and public policy. The working assumption is that parties use policy as a tool for branding. This is extremely useful for explaining why partisan candidates take positions on salient issues with which the public, particularly low-information voters, have a working understanding. For instance, it behooves elected officials to take positions on economic policy in ways that reinforce their reputation more broadly. Political scientists have long documented the centrality of economic policy to the behavior of voters (Fiorina Reference Fiorina1978; Lewis-Beck Reference Lewis-Beck1985). Economic policy that connects directly to the pocketbook has a particularly high salience and public accessibility. Therefore, elected officials have incentive to tie their reputation to pocketbook-related economic policies.

What happens with policy issues that the public considers to be less accessible? Through the logic of partisan branding, elected officials have very little political incentive to take positions on these issues. Why take a position on a more technical or complex policy issue that most voters do not understand? When public understanding is low, the public should be much less likely to develop strong preferences around a particular policy issue (Crowder-Meyer, Gadarian, and Trounstine Reference Crowder-Meyer, Gadarian and Trounstine2020). This is consistent with the literature on low-information voters, which routinely documents their heavy reliance on heuristics (Schaffner and Streb Reference Schaffner and Streb2002; Zaller Reference Zaller2004). Low-information voters are, therefore, more likely to follow the party brand than to follow a public official, when forming their positions on a dense or seemingly obscure policy issue. So, how do we explain the rare deep politicization of more complicated policy issues? This is the puzzle that confronts the politics of antiracist teaching and critical race theory.

The politicization of critical race theory

Critical race theory (CRT) has emerged as one of the most contentious policy issues, not just within the politics of education but within American politics more broadly. In addition to playing a role in the 2021Virgina Gubernatorial Election, conservative political candidates across the local, state, and federal levels have employed anti-CRT positions to advance their political campaigns. Political officials have also taken legislative action on the issue. In the span of 2 years (2020–2022), 36 of 50 state legislatures received bills sponsored by Republican Party lawmakers looking to ban CRT.Footnote 4 However, in 17 states, lawmakers of the Democratic Party have also sponsored bills to counteract the assault on CRT by supporting the expansion of efforts to teach kids about racism and racial bias. CRT has become a policy that fits into the larger sphere of partisan polarization.

CRT, as a policy idea, traces directly to the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd in May of 2020 (Ray Reference Ray2022). Floyd, an unarmed African American male, was violently choked to death by a white police officer. Floyd’s murder sparked a months-long spree of protests for racial justice across the USA in different parts of the world. Emerging from Floyd’s murder was a national conversation on antiracism and the need for white Americans to engage in discussions about the depths of anti-black racism and white privilege (Gause Reference Gause2022). This national conversation sparked discourse on teaching concepts of antiracism to adults and eventually to students in schools. However, the George Floyd protests were not a national call for critical race theory, let alone any sort of mandatory teaching of the concept.

CRT was never called for because it is not an education policy initiative. It is a rigorous nichè legal theory taught in the corners of the most prestigious law schools in the USA. CRT, as a theoretical lens, argues that anti-black racism is deeply integrated into the fabric of American law, policy, and societal norms (Bell Reference Bell1995; Delgado and Stefancic Reference Delgado and Stefancic2023). The actual theory is a major departure from the policy debate occurring in legislative chambers. Policy aiming to ban CRT strives to penalize teachers (and their schools and/or districts) for discussing race in the classroom. The affirmative policy proposals push to position teachers to discuss race and identity in the classroom. These policies largely intend to impact civics and social studies curricula.

CRT, I argue, is the result of strategic policy branding. The anti-CRT movement began with former President Donald Trump launching the 1776 Commission to promote “patriotic education” (Wise Reference Wise2020). This was a direct response to journalist Nikole Hannah Jones publishing the 1619 Project, which placed the enslavement of African people at the center of understanding American history (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2021). While CRT became an increasingly emphasized focus issue in Trump’s condemnation of “divisive” teaching that focused on race, conservative activist Chris Rufo turned the attacks into a strategic political messaging campaign. In fact, Rufo admits to explicitly branding CRT as a policy issue when he tweeted in 2021: “The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think “critical race theory.” We have decodified the term and will recodify it to annex the entire range of cultural constructions that are unpopular with Americans,” (Martinez Reference Martinez2022). CRT was, therefore, branded as a policy catchall for white resentment toward a more diversifying American culture. American schools serve as the centerpiece of this larger culture war that has grown to dominate political discourse in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown (Collins Reference Collins2023).

That CRT has become salient as an education policy issue is an unexpected outcome. Education policy issues rarely surface to the top of the political discourse in the USA. Gallup public opinion surveys asking Americans to rank the most important problems show education routinely prioritized underneath the economy, crime, and racism (Saad Reference Saad2022). A part of the lack of national attention to education policy is structural in that states have constitutional authority. When education policy has garnered national attention, it has been when it interacts with other, more salient issues, mainly race. For example, education policy is arguably most salient in the mid-20th century due to the Brown versus Board of Education ruling, when education policy directly interacts with racism and racial inequality (Frankenberg, Ayscue and Orfield, 2019). The ruling triggered federal intervention to support school desegregation as well as the creation of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, which created the Title 1 Program to address the economic inequality that heavily overlapped with racial discrimination. Thus, when race moved to the center of the USA national policy debate, the USA federal government made its most seismic education policy shift.

The issue of critical race theory demonstrates how education policy reform can become extremely salient when connected to race. What differs between the CRT debate and the school desegregation movement of the mid-20th century is that the latter is rooted in an actual policy debate ignited by a Supreme Court judicial ruling, while the former is based on a political construct. However, CRT, at the core, is a term that seems to activate ideas of an intrusion on white cultural values, with the teaching of ideas of race or alternative histories as the intrusion tool. Thus, CRT as a policy reform, is an arbitrary concept that has been forged onto the idea of teaching kids about white privilege and structural racism. The application of CRT by education researchers shows proof of a mislabeling project. The research applying a critical race theory lens to the study of education focuses on conceptualizing racial inequities in education through our understanding of how race and property rights prevent major shifts toward racial justice (Ladson-Billings Reference Ladson-Billings2021). The aim of the research is to help district and school leaders as well as teachers better meet the needs of students on the wrong side of racial inequity distributions.

The CRT policy debate has erroneously centered around preventing teachers from having students discuss race in the classroom. Fittingly, there is currently no state or federal mandate that teachers teach about race. The policies put forth seeking to ban CRT are policies that create the conditions for parents and students to take legal action should race be discussed in a way that makes students feel uncomfortable. These are not policies that impact the day-to-day operation of schooling in the way that school desegregation busing plans do or even policies around school funding reform or standardized testing. So, what explains differences in public opinion on the larger issue surrounding CRT?

Policy branding

I argue that public opinion on whether schools should be allowed to teach children about race is largely driven by two factors. The first factor is the major political cleavage attached to the issue. The other factor is what I am calling policy branding. With the political cleavage, race and racial attitudes should be what largely explains support and opposition for antiracist teaching and curriculum. Through policy branding, parties reconstruct a more threatening and divisive definition of the policy issue. Policy branding should, therefore, deepen polarization on the original issue.

With policy branding, a party or faction group targets a policy high in salience but low in technical understanding. That organization then brands the policy by taking a strong support (or oppositional) position on the issue. Parties, for instance, can engage in policy branding to further reinforce their own partisan brand. Policy branding, therefore, can work in concert with partisan branding. However, the distinction is that parties engage in partisan branding by taking positions on issues that reach a level of national salience and on which the public has an opinion rooted in a working understanding of the policy. Partisan branding is reactive to issues with which the public is relatively knowledgeable. However, parties engage in policy branding when taking a position on an issue where public opinion is opaque. Parties, therefore, brand the policy that is highly salient but lacking opinions formed through exercising policy knowledge.

Policy branding allows parties to create a policy issue on which the public largely lacks accurate or technical information. This allows parties to, therefore, leverage a lack of information that the public has on the policy issue to brand it in a strategic way. Policy branding creates channels through which new information on the issue can be created. If a party can benefit from framing an issue as threatening to voters, the party can take the lead in disseminating information suggesting such. Parties can also, therefore, brand a policy as an issue that urgently requires mass mobilization. Policy branding has direct implications for policy opinion formation and political behavior.

Policy branding relies on a policy issue becoming salient, primarily through controversy. More specifically, parties look to brand a derivative of an existing issue through a controversial frame. Policy branding, therefore, builds upon Vesla Weaver’s (Reference Weaver2007) notion of frontlash. Weaver defines frontlash as” the process by which formerly defeated groups may become dominant issue entrepreneurs in light of the development of a new issue campaign.” However, whereas Weaver’s frontlash idea centers on the fusion of multiple issues (e.g. crime into racial equality), policy branding repurposes something arbitrary into a policy issue. In other words, policy branding is about constructing an idea and branding it as a policy, as opposed to realigning an existing policy issue with another policy area. Policy branding, therefore, adds an additional level of understanding to how parties engage in policy issue entrepreneurship.

Critical race theory as policy branding

I argue that critical race theory has been a victim of policy branding. The argument hinges on the claim that CRT became a highly salient, low-information policy issue. Does CRT fit these criteria? In order to address this salience component, I turn to data from Google Trends. Figure 1 shows the search interest as a standardized measure between 0 and 100, with 100 being the highest level of search interest within the given terms. The figure shows search activity over the span of 3 years (2020–2023). In addition to search activity around the term “critical race theory,” I include the term “antiracist,” which is the term more accurately connected to the civics and social studies curricular movement aiming to expand teaching about race. I also include two of the most widely and publicly debated education policy issues: “standardized testing” and “school choice.”

Figure 1. Internet Search Interest by Term (2020–2023). Note: Graph displays Google search activity trends for four terms: “critical race theory,” “antiracist,” “standardize testing,” and “school choice.” The activity is displayed on a 0–100 scale that is indicates the relative popularity of the search terms, with 100 being the highest level of relative popularity.

The term “critical race theory” generates significantly more search activity over the three-year period. The term “antiracist” generates the first surge in search activity, and it occurs on May 31st, which is 5 days after the murder of George Floyd. From there, the majority of the search activity surrounding the four terms is associated with critical race theory. The second major spike (and the first surge in search activity around critical race theory) occurs on September 6, 2020, which is the same day that then-President Donald Trump announced via Twitter that the USA. Department of Education would be investigating whether schools could use the 1619 Project history curriculum.Footnote 5 During the second spike, CRT accounts for 17% of search interest relative to the highest point over the three-year period. Of the other terms, only “school choice” rose above 1% to account for 3%.

The largest spike in interest in any of the terms was search activity on CRT on June 20th, 2021. This was the day after the USA federal government recognized Juneteenth as a national holiday, which is a holiday long celebrated by African Americans in Texas to commemorate the emancipation of Africa-descending slaves within in the USA. While CRT was the most widely searched term on that day (reaching the highest point of the three-year period), only school choice, once again, rose beyond 1% at 2% of the total search interest. Critical race theory maintained an extremely high level of salience from 2020 onward before dissolving in 2022.

Salience, however, is one condition. The other condition for policy branding is that the public must not be well informed on the issue. Google Trends information is useful in testing this as well. Table 1 displays the most common queries Google searchers made in relation to the term. As the first column of the table illustrates, all of the top 5 queries on CRT emerge from questions about the misinformation surrounding CRT. Searchers showed interested in whether CRT is taught in schools, when there is no evidence of district-or-state-sanctioned CRT K-12 curriculum being used in America’s schools, and whether CRT has been banned. There is inquiry into what is said about CRT on Fox News (a conservative national media outlet that circulated misinformation on CRT). Meanwhile, we also see search activity around the 1619 Project, which does not mention CRT, and President Biden, who never addresses CRT in any speeches or addresses. The search activity speaks to the larger confusion around the term.

Table 1. Google trends search Queries by term

Note: Term rankings are derived from Google Trends.

For comparison, none of the top 5 queries around the term “antiracist” involved such questions rooted in misinformation. Instead, most of the search activity is related to the texts on antiracism published by scholar Ibram X. Kendi, which do not involve the application of critical race theory. For the more mundane education policy terms “standardized testing” and “school choice,” the search activity centered around the implementation status of each. Very little of the search activity for the other terms show such clear signs of confusion around the term itself. In comparison, the general public appears to have a particularly low level of understanding of what critical race theory is, despite its extremely high salience.

Search activity is but one source of evidence. While useful, it raises endogeneity concerns. It is difficult to fully make the claim that search query language is indicative of the public’s level of policy (or terminology) knowledge because one of the primary purposes of an internet search is to seek information on an issue. The queries could, therefore, speak more to what internet users must search in order to find information than how uninformed they are upon conducting a search.

I, therefore, examine public opinion polls measuring Americans’ support for (or opposition to) critical race theory. Most surveys, however, ask the public about their support for teaching students about race and/or racism. However, a small set of surveys ask specifically about CRT. I am particularly interested in policy salience and policy knowledge on the issue. Surveys reveal a relatively high salience level. A Fall 2022 poll conducted by the USC Rossier School of Education finds that nearly two-thirds of respondents were familiar with the term CRT to some degree. Yet, less than 20% said they knew “a lot” about the concept or “enough to explain to others,” (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2022). A year prior, a poll conducted through a collaboration between YouGov and the Economist found that, in June of 2021, only 36% of Americans had either never heard of CRT or had “heard only a little about it,” (Economist, 2021).

Meanwhile, polls that measure policy knowledge on CRT find that Americans, on average, know very little about the concept. In a November 2021 national poll of over 19,000 respondents, Alauna Safarpour, David Lazar and colleagues (Reference Safarpour, Lazer, Lin, Pippert, Druckman, Baum and Qu2021) estimate that about 70% of respondents could not accurately articulate a definition of CRT. In a Reuters and Ipsos poll conducted in July of 2021, they find that over 40% of respondents were familiar with the term, but when those familiar with the term were asked seven true-false follow-up questions, only 5% provided all correct answers. Only 32% answered a majority of the questions correctly (Duran and Jackson, Reference Duran and Jackson2021). There is external evidence that, while salience is high, knowledge is low. I, therefore, move into the study of explaining attitudes toward CRT with evidence that conditions for policy branding have been met. However, can we find clear evidence that CRT opinions are driven by policy branding?

Measuring public support for antiracist curriculum

To establish measurement of the effect of policy branding, I begin by measuring the core issue of antiracist curriculum policy. I begin with antiracist curriculum policy because it is the idea central to the CRT debate. It helps us understand the potential role of race as a political cleavage. I measure support for antiracist curriculum by fielding a series of nationally representative surveys entitled, “Assessing Opinions of Public Education and Political Participation under COVID-19.” Through survey research firm Prolific, I fielded the first iteration of the survey in 2020 from July 30th to Aug. 2nd to a sample of n = 1,273 respondents. I fielded a replication to an entirely different group of respondents in 2021 from Jan. 21st to 26th (n = 983). These are nationally representative surveys.Footnote 6 Specific to antiracist curriculum, I use the surveys to present half of the participants with the following language: “All schools should feature curriculum that teaches kids about the history of racism in the USA” Relying on a Likert scale to capture responses, I ask them to indicate whether they strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, disagree, strongly disagree, or neither agree nor disagree with the statement.

There is also an experimental component to the surveys. As the political debate about antiracist curriculum entered the public sphere, my initial hypothesis was that the source of opposition would be rooted in civil liberties. I suspected that parents, particularly White parents, would object to antiracist curriculum because they would see the teaching of it in schools as an infringement upon their rights as parents, who should have a say in whether their child is taught controversial topics. As a result, I presented the other half of the respondents with the same statement that I show in the previous paragraph, but with an added clause that the schools feature this curriculum regardless of whether parents give consent. Here is the specific language presented to the treatment group: “All schools should feature curriculum that teaches kids about the history of racism in the USA, regardless of whether their parents’ consent.”

In addition to the primary statement about antiracist curriculum and the consent experiment, the surveys include additional variables that I use to assess other factors that may contribute to opposition to antiracist curriculum. I, of course, include a list of the usual suspects used by social scientists in survey research. Given the focus on schools and curriculum, I ask about parental status. Because of the politicized nature of the issue, I also record partisan and ideological identities. I include age as well, and due to the racialized nature of the issue, I retrieve racial identity.

To the idea of race as the political cleavage, I wanted also to include a variable that helped assess the link between antiracist curriculum and racial politics – not just identity. The distinction is one that has been made consistently in political science (Smith 2004; Hutchings and Valentino 2004). While racial identity is one’s in-group association with a particular racial group, racial politics is any sort of political project where race is the primary driver (Sawyer Reference Sawyer2005; Phoenix Reference Phoenix2019; Jefferson et al. Reference Jefferson, Neuner and Pasek2021). The George Floyd Protests of 2020 represent a major episode of racial politics. Millions around the country gathered in mass demonstration against the idea of racial injustice. This political moment, arguably, became a catalyst for conversations around antiracism. Could attitudes toward the protests factor into support for antiracist curriculum? What about the Jan. 6th Capitol Insurrection? With white supremacists making up a contingent of the rioters, there is reason to believe that the event was, at least to some degree, racially motivated.

I test this. I presented survey participants with the following language: “I OPPOSE the summer protests that occurred in reaction to unarmed African Americans being killed by police officers.” Once again, they can agree or disagree on the full Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Given the presence of self-identified white supremacists, there is also reasonable suspicion that the January 6th Capitol Insurrection was motivated by racism and xenophobia (Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Alegre, Bailey, Davis, Ferrer, Nguy and Robertson2023). I, therefore, include the following statement: “I OPPOSE the protests that led to the USA. Capitol being raided and damaged on Jan. 6th, 2021.” However, given that the event did not occur until after I fielded the first survey, I only collected reactions to the Jan. 6th Capitol Insurrection in the 2nd iteration and beyond. In sum, I measure public support for antiracist curriculum and a host of factors that I hypothesize to be related to that support or opposition.

Do Americans support antiracist teaching?

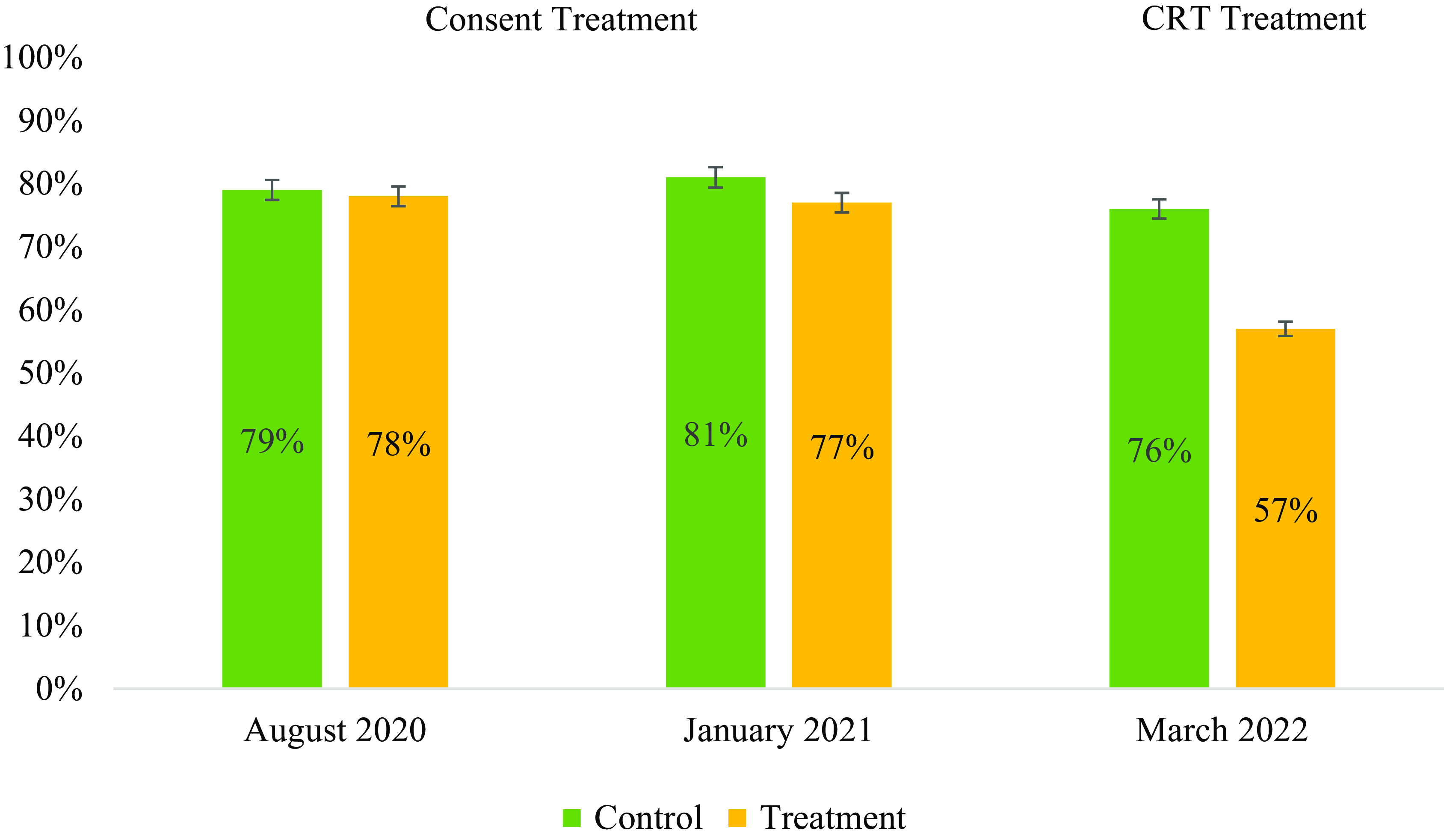

The analysis from my survey data collection effort reveals what has run counter to the public narrative. Americans, on average, expressed overwhelming support for antiracist curriculum. Figure 2 provides the results for the control group responses to the 2020 and 2021 iterations of the survey. In measuring support for antiracist curriculum, I distinguish between respondents who indicated that they either strongly agreed, agreed, or somewhat agreed with the statement shown in the survey compared to the survey participants who chose disagreement or the neutral response. As we can see, about 80% of the samples expressed some level of support for antiracist curriculum, and the results remain virtually unchanged over the two iterations. Also, in terms of the parental consent dynamic, respondents shown the treatment were equally as likely to support antiracist curriculum in 2020 and 2021.

Figure 2. Public Support for Antiracist Teaching with and without Consent Message. Note: Results are means derived from two separate surveys of national samples of Americans. Error bars indicate standard error ranges around mean estimations.

I examine support for antiracist curriculum for specific demographics of respondents as well. On Table 2, I show average support for antiracist curriculum for not only the full control group samples but also parents, Black and White respondents, Democrats, Republicans, liberals, conservatives, and seniors. Every demographic, on average, expressed some level of support for antiracist curriculum, whether it be parents (82% in 2020; 81% in 2021), White Americans (78% in 2020; 77% in 2021), conservatives (59% in 2020; 52% in 2021), or Republicans (56% in 2020; 52% in 2021). The latter two, conservatives and Republicans, are the only two groups that decline more than 3% points from 2020 to 2021. The support for antiracist curriculum was strong and persisted across groups.

Table 2. Public support for teaching about Racism, 2020 & 2021

Note: Results are means derived from two separate surveys of national samples of Americans.

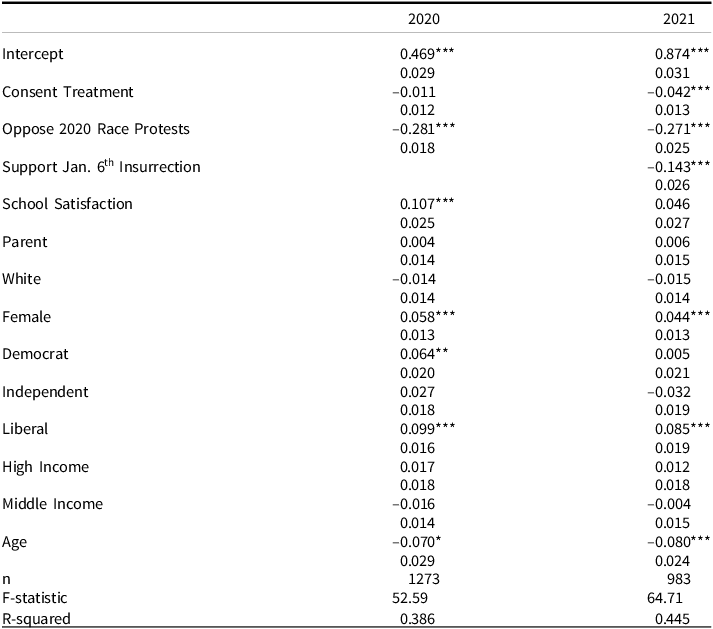

The question then becomes, what explains the minority of opposition to antiracist curriculum? To explore this question, I conduct a multivariate regression analysis to try and assess the relationship between support for antiracist curriculum and the assortment of variables I measure alongside it. I standardized the variables in the statistical model to vary between 0 and 1. This enables me to produce measurements that can be interpreted almost as percentages. Table 3 provides the results of the regression analysis. It shows two columns; the 1st column shows the results for 2020, while the 2nd column displays the estimates for 2021.

Table 3. Modeling support for Antiracist history teaching, 2022 & 2021

Note: Results are produced using ordinary least squares (OLS) multivariate regression.

***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

For both years, the strongest predictor remains the same. Respondents who opposed the George Floyd Protests of 2020 were most likely to oppose antiracist curriculum. More specifically, if you strongly opposed the protests, you were about 0.28 or 0.27 standard units (close to 28% or 27%) less likely to support antiracist curriculum than someone who strongly supported the protests. The second largest factor in 2020, school satisfaction (those with high satisfaction with their own district schools were more likely to support antiracist curriculum), is less than half the coefficient size, which suggests it has a much less robust relationship with antiracist curriculum. In 2021, the second largest coefficient is another political event; support for the Jan. 6th Capitol Insurrection is negatively correlated (0.14 standard units or close to a 14% difference) with support for antiracist curriculum (supporters of the insurrection were significantly less likely to support antiracist curriculum). Opposition towards antiracist curriculum appears to be a direct function of individual attitudes towards the George Floyd Protests and the Capitol Insurrection. Race seems to be the main political cleavage wedging the divide in opinion.

Equally as interesting as what turns out to be related to support or opposition towards antiracist curriculum is what is statistically uncorrelated. For instance, parental status is statistically unrelated during both the 2020 and 2021 iterations. In other words, parents are no less likely to express support for antiracist curriculum than are non-parents. White respondents are also no less likely to support antiracist curriculum than people of color. The key caveat to keep in mind is that this estimate is the relationship between identifying as White and support for antiracist curriculum with the other factors held constant. This means that, when we account for the ideological differences and views towards the major political events, White Americans are no less likely to support antiracist curriculum. This also reinforces the primary finding, which is that – beyond racial identification – one’s position on these racialized political events largely dictates support or opposition towards antiracist curriculum.

From antiracist teaching to policy branding as critical race theory

My analysis of the surveys I fielded in 2020 and 2021 offer evidence of how support for antiracist curriculum seems to work. Despite the surrounding political controversy, Americans seemed to be in favor of antiracist curriculum both in 2020 and 2021. Now, because of the political controversy, the biggest differences in support/opposition seem to a function of the politicization and racialization of the debate. Different views toward the George Floyd Protests of 2020 and the Jan. 6th Capitol Insurrection as well as overall ideological differences between liberals and conservatives appear to be what drives the divide. This politicization of antiracist curriculum creates the conditions for policy branding. If the racialization is motivating the opposition toward antiracist curriculum, arbitrarily rebranding the issue as more explicitly racialized should further increase opposition.

As I mentioned earlier, I rely on a survey research firm to recruit survey participants. Within the firm’s user platform, there is a direct messaging tool. So, survey participants have the option to send direct messages to researchers like me, while they are participating in our studies. While fielding the 2021 survey, I received a message from a participant who completed the survey, but they needed deliver their sentiment. “I just want to let you know that I don’t have a problem with schools teaching kids about racism, but what I don’t support is that critical race theory!” This respondent’s support for antiracism curriculum yet rejection of “critical race theory” illustrated the depth of policy branding project undertaken by political conservatives to construct a policy issue that seemed distinct.

Was this single disgruntled respondent representative of the larger population? Are Americans, particularly individuals identifying as politically conservative, responsive to this political construction of CRT? Has CRT become a function of policy branding? This single respondent led me to field the third survey with an adjustment to the experimental design. Instead of randomly assigning half of the respondents to express support for antiracist curriculum regardless of parental consent, I tested for policy branding by asking the treatment group whether they supported “a Critical Race Theory curriculum, which teaches kids about the history of racism in the USA” The only difference between control and treatment are the words “critical race theory” inserted into the latter. I fielded the third iteration of the survey in March of 2022. It was another nationally representative survey, with a larger sample (n = 1509). Beyond the CRT treatment, the other questions used to construct the additional variables for the analyses remained the same from the previous surveys.

I also fielded the experiment in the third iteration after the original experiment, parental consent, seemed to have little-to-no impact on support for antiracist curriculum (see Figure 3). As Table 4 displays, the coefficient size for the first two iterations of the results was extremely small (no more than 0.05). Moreover, the estimated impact of the treatment only reaches statistical significance in 2021. The interpretation of the results of the experiment for the first two waves is that, in 2020, the idea of parental consent did not matter at all on average, and we can be confident that there was a small negative impact imposed by the idea of consent in 2021. This is consistent with the initial results in Figure 2.

Figure 3. Antiracist Teaching Support Experiment Results. Note: Results are means derived from three separate surveys of national samples of Americans. Error bars indicate standard error ranges around mean estimations.

Table 4. Modeling support for Antiracist history teaching, 2020–2022

Note: Results are produced using ordinary least squares (OLS) multivariate regression.

***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

When I test the critical race theory treatment, I see a notable difference. While the parental consent experiment only resulted in a 4% decline in support between treatment and control in 2021, the CRT treatment led to an almost 20% decrease in public support for antiracist curriculum in 2022 (see Figure 3). When I conduct an additional regression estimate for the 2022 data with the new treatment, the multivariate results are consistent with the raw treatment effects shown in Figure 3. As column 3 of Table 4 shows, respondents who received the treatment were 0.185 standard units (around 19%) less likely support antiracist curriculum. This makes my very simple language-tweak-of-a-treatment the third most impactful variable on preferences for antiracist curriculum. The only stronger predictors beyond having received the treatment are the two variables that have remained strong throughout the entirety of this analysis, which are one’s opposition towards the 2020 racial injustice protests and/or one’s support for the Jan. 6th Insurrection, respectively.

There is a concern that the effect of the treatment may be a part of a larger zeitgeist effect. Perhaps the CRT treatment works because any racialized curricular idea or concept would be negatively received once we reach the year 2022. This could be a zeitgeist effect. Perhaps anything mentioning race, whether it be CRT or “antiracist curriculum,” drew more disdain than in previous years. I look more closely at the control group to explore this possibility.

Figure 4 reveals the findings. There is an overall downward shift in support for antiracist curriculum happening from 2021 to 2022, but that shift is extremely small (5% points) relative to the effect of the treatment (20% points). Still, except for liberals, the shift is consistent across demographic groups within the control group. According to the table on Figure 4, the biggest drop is amongst control group Republicans, who are 8% points less likely to support antiracist curriculum in 2022 than control group Republicans were in 2021. However, even despite the small overall decline across groups (for the control group), Republicans were the only group in 2022 to have less than a majority express support for antiracist curriculum. In other words, there is a small falling tide, but the support for antiracist curriculum remains above sea level.

Figure 4. Public Support for Antiracist Teaching, 2020 – 2022. Note: Results are means derived from three separate surveys of national samples of Americans.

In juxtaposition, the literal term “critical race theory” seems to be what considerably drags down support for antiracist curriculum. When I look at the differences across demographic groups between the CRT treatment group and the control group, the power of the simple phrase “critical race theory” is extremely clear. As Figure 5 shows, every demographic becomes noticeably less likely to support antiracist curriculum, when presented with the term “critical race theory.” Support amongst parents is 22% lower. Democrats and liberals are 15% less likely to support antiracist curriculum at the mention of CRT. Even Black Americans show a sizeable decline (9% less likely). Meanwhile, support amongst Republicans and conservatives decline by an enormous 30%. These are moderate-to-seismic downward shifts. They underscore the title of this article, which is that, when it comes to support for antiracist curriculum, Americans support the concept. Yet, they have been primed to oppose the rebranded term: “critical race theory.”

Figure 5. Effect of CRT Treatment Across Demographic Groups. Note: Results are means derived from a national sample surveyed in 2022. Bars indicate average support for the CRT treatment versus the antiracism control disaggregated by subgroups.

Discussion

I find evidence that there has been consistent, widespread support for K-12 antiracist teaching or teaching about the history or racism in the USA. That widespread support extends across three years, as captured by three nationally representative surveys conducted in 2020, 2021, and 2022. The strong support is bipartisan and transcends divides in political ideology, although support is weakest amongst self-identifying Republicans as well as political conservatives. Meanwhile, the strongest predictors of Americans’ opposition to antiracist teaching are opposition to the George Floyd Protests of 2020 and support for the Jan 6. Capitol Insurrection. As one would expect, negative racial attitudes and perceptions of racial threat, are driving the relatively small opposition to antiracist teaching.

When antiracist teaching is masked behind the concept of critical race theory, the overall level of opposition increases. I find that that by just referring to antiracist teaching as critical race theory in 2022, Americans are much less likely to support it. While the increased opposition occurs across groups, it is most pronounced amongst Republicans and conservatives. However, white Americans and parents show an increase in their opposition to the term as well. I argue that this is clear evidence of policy branding. Conservative strategists have taken a non-policy issue and branded it as a policy issue. Half of the political conservatives in the control support antiracist teaching. Less than a fourth of the conservatives in the treatment support CRT.

Policy branding, as a broader concept is not new, particularly the rebranding of policy for the purpose of racialization. Conservative leaders branded the Affordable Care Act of 2010 as Obamacare, and subsequent research found strong evidence of opposition to the healthcare reform policy directly linking to negative racial attitudes (Tesler, Reference Tesler2012). In 2008, Democratic Party elites used the legislative process to rebrand the Food Stamp Program as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) because the former had been contorted into racialized stigma (Shaw, Reference Shaw2009). The idea of branding American policy by attaching it to (or detaching it from) racial attitudes is a routinely employed political strategy.

The difference with critical race theory is that this type of policy branding is closer to a complete political construction of a term. Political elites retrieved a term that is largely unrelated to the central policy issue, social studies curriculum, and branded it as a central part of the policy debate. This new type of policy branding has scary implications for public policy moving forward. More ideas that are developed within the academy could be employed, oversimplified, and weaponized within our larger political discourse. Legislative bodies can continue to pass actual laws based on the threat of academic terms. Parties can, therefore, strengthen their brand by labeling rigorous and transformative academic ideas as policy terms that threaten the livelihoods of those consuming misinformation through the policy branding process. We see this in the state of Florida, where Gov. Ron DeSantis escalates political opposition to the “War on Woke” in an effort to target the teaching of Black history in K-12 schools, policies and practices protecting diversity, equity, and inclusion programs at the higher education level, and programs, strategies, and initiatives that protect and/or affirm LGBTQ citizens (Lopez and Sleeter Reference López and Sleeter2023). Critical race theory is just be the beginning.

Policy branding can also lead to an inattention to more pressing policy concerns. The irony of the politicization of CRT as a social studies/civics curriculum is that it distracts the public from the fact that states need substantive policy intervention around social studies and civics curriculum. Civics, as an area of K-12 study, has been in desperate need of more aggressive policy action for decades. Civics is the subject area that has been evaluated the least over time by the USA. Department of Education’s National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) program, which has been testing and evaluating student achievement for students at elementary and secondary levels since 1973. In that span, NAEP has produced 14 assessments of math and reading achievement. How many times have they evaluated student knowledge of civics over that period? Five: 1998, 2006, 2010, 2014, and 2018. The national inattention to civics education should be deeply concerning.

It is not just a problem of federal neglect. State education agencies have control over the curricula put in place within districts across their states. When it comes to subjects like math and reading, states make attempts to outline clear academic guidelines and expectations. They establish parameters for what the curricula in these subject areas should include and/or emphasize. Some states allow districts to recommend curricula, but even in those cases, the state education agency must approve it based on accountability standards that the state has established. This same process exists for civics and social studies curricula, but states’ attention to standards and accountability are much more laxed. State education agencies devote minimal staff to civics curriculum administration and oversight. Most states do not produce any sort of statewide civics assessment. Recent research highlights the inability for standard civics curricula to foster skills for democratic engagement (Nelson Reference Nelsen2023). The legislative action stemming from the policy branding of CRT, therefore, occurs within a larger policy environment that has been plagued by inaction on civics and social studies reform. By fostering misinformation and preventing meaningful civics policy reform, the movement to policy brand critical race theory as an education policy issue is one of the largest modern threats to American democracy.

The threat to democracy, however, is much deeper. Branding academic terms and racializing them in the effort to do so has important consequences. The attacks on Black education and inclusive schooling at the K-12 and higher education levels threaten access to not just academic development but also civic knowledge and skills. This type of negative policy branding makes Black communities and other marginalized communities in the USA targets of efforts that can result even higher barriers to political participation (Walton Reference Walton1985; Nunnally Reference Nunnally2020; Dawson Reference Dawson2019; Collins and Block Reference Collins and Block2020). In other words, the CRT policy branding could lead to the further accumulation of what Sally Nuamah (Reference Nuamah2022) calls “collective participatory debt.” When terms are weaponized for politics, they can leave everlasting scars.

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse:

Collins, Jonathan, 2024, “Replication Data for ‘They Only Hate the Term’”, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LF1SIG, Harvard Dataverse, V1

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to feedback I received from Jack Schneider. I also received constructive feedback from Ricky Blissett and the AERA ’23 “Public Power and Opinion in Education Reform” panel.