Introduction

As the proponents of representative bureaucracy have long advocated, when bureaucrats share the same key demographic characteristics as their target population, they are more likely to understand their needs and interests and are therefore better able to serve them (Kingsley Reference Kingsley1944; Krislov Reference Krislov1974; Krislov and Rosenbloom Reference Krislov and Rosenbloom1981; Meier Reference Meier1993). This has been found to be true for major identity categories such as race (Gilad and Dahan Reference Gilad and Dahan2021), ethnicity (Choi and Hong Reference Choi and Hong2020), and gender (An, Song, and Meier Reference An, Song and Meier2022), as well as sexuality (Davidovitz Reference Davidovitz2022), country of origin (Grissom, Darling-Aduana, and Hall Reference Grissom, Darling-Aduana and Hall2023), region (Rivera Reference Rivera2016), culture (Cohen Reference Cohen2018), and language (Murdoch et al. Reference Murdoch, Gravier and Gänzle2022). Over the years, the literature on representative bureaucracy has expanded considerably, accounting for a wider variety of identities and taking more intersectional approaches.

There is, however, an identity category that has so far been overlooked. In different regions of the world, and Europe, in particular, the “migrant” identity is of high importance, especially since the so-called migration crisis of 2015–2017. Yet, from a public administration perspective, little attention has been dedicated to existing migrants who, after several years of residence, are now active on the frontlines of migration management, delivering social services to recently arrived migrants. There is, therefore, a phenomenon whereby “old” migrants are serving “new” migrants. This article examines this phenomenon through the lens of representative bureaucracy, seeking to shed light on how being simultaneously a migrant and a migration policy implementer shapes migrant bureaucrats’ discretionary behavior.

The term “migrant” is broadly defined here, including expatriates, economic immigrants, and asylum seekers and refugees, independent of their ethnicity, nationality, or race. Accounting also for the complex nexus of state and non-state actors in Europe’s migration management landscape (Glyniadaki Reference Glyniadaki2021), those who implement migration policy on the ground will be considered street-level bureaucrats (Lipsky Reference Lipsky1980) sensu lato. In short, they will be referred to as “migrant bureaucrats,” irrespective of whether they work for public agencies, NGOs, or grassroots groups (see also Brodkin Reference Brodkin2012).

As such, migrant bureaucrats may or may not share similar ethnic, religious, linguistic, or cultural backgrounds with their migrant clients. Even so, sharing a “migrant” identity in the same host society still assumes some common experiences and interests. For instance, non-discrimination and equal rights for migrants in relation to access to education, work, or healthcare would be a shared goal among migrants from all backgrounds. The question that consequently arises is whether migrant bureaucrats would be more likely to help migrant clients because of this shared identity. In representative bureaucracy terms, would passive representation lead to active representation? This research examines this question, using qualitative interviews with migrant street-level bureaucrats who delivered social services (e.g. housing, social work, and legal assistance) to newly arrived migrants in the capital cities of Athens, Greece, and Berlin, Germany, between 2015 and 2017.

This article contributes to the existing literature in two ways. First, placing emphasis on the “migrant” identity category and building on the notion of “minority representative” (Selden et. al. Reference Selden, Brudney and Kellough1998) introduce the term “migrant representative.” Both denote that active representation depends upon the extent to which street-level bureaucrats adhere to the role of a representative of their clients, whether these are migrants or minority persons. Second, by looking more closely at how migrant bureaucrats self-identify, this research finds four profiles of migrant bureaucrats: “spokesperson,” “localised,” “peacemaker,“ and “ambivalent.” Each of these profiles corresponds to a different level of identification with, on the one hand, migrant clients and the migrant representative role or, on the other hand, the local migration management system and the system representative role (see also citizen agent vs. state-agent – Maynard-Moody and Musheno Reference Maynard-Moody and Musheno2003). The role played by the status of the migrant bureaucrat in shaping their stance toward migrant clients is also discussed.

The remainder of this article begins by reviewing the existing literature on representative bureaucracy, especially in relation to race and ethnicity, and discussing how these apply in the European social context. Next section describes the research methods of this study. This is followed by a presentation of the four migrant bureaucrat profiles identified, as well as an empirical section that illustrates these findings based on interview data. The article ends with an analytical discussion of these observations.

Passive versus active representation

Public administration scholars generally view representative bureaucracy as good and desirable. When the personnel of a public agency reflect the diversity of the general population, the interests of all citizens are thought to be better represented (Saidel and Loscocco Reference Saidel and Loscocco2005). The assumption is that when public servants share the same key identities, such as race, class, or gender, with their clients, they also share common life experiences and values. As a result, public servants are better able to identify the specific needs and interests of their clients, therefore being better placed to serve them (Dolan and Rosenbloom Reference Dolan and Rosenbloom2003; Meier Reference Meier1993; Riccucci and Meyers Reference Riccucci and Meyers2004; Selden Reference Selden1997).

Nonetheless, having a proportional number of minority, working-class, or female bureaucrats does not necessarily guarantee substantive representation of the needs or interests of the respective social groups. Put differently, passive representation does not automatically lead to active representation (Mosher Reference Mosher1986). Studies have shown, for example, that when minority bureaucrats are worried about their own professional standing within the organization, they are less inclined to go out of their way to help minority clients (Watkins-Hayes Reference Watkins-Hayes2011). Similarly, if they can only advance within the organization by adopting the existing organizational values, they are less likely to take action to change the status quo once they rise to a position of power (Thompson Reference Thompson1976).

Passive representation is therefore not a sufficient condition for active representation, but nor is it a necessary one. That is, active representation may also come from non-group members (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2013), what Slack (Reference Slack2001) calls “indirect representation.” Either due to their formal education or due to their close contact with another group, bureaucrats may develop an enhanced understanding of that group’s needs and, in turn, be more helpful. Black and Latino students, for instance, may receive high support from white teachers who are aware of their pupils’ disadvantaged circumstances (Harber et al. Reference Harber, Gorman, Gengaro, Butisingh, Tsang and Ouellette2012), and homosexuals living with HIV/AIDS may encounter engaged advocacy by community members who are heterosexual and uninfected (Slack Reference Slack2001).

While the linkage between passive and active representation remains under scholarly scrutiny, certain factors do seem to facilitate this relationship. At the individual level of analysis, one of the key determinants that shapes a bureaucrat’s behavior is their notion of the “minority representative role” (Selden Reference Selden1997; Selden, Brudney and Kellough Reference Selden, Brudney and Kellough1998). Simply put, whether and how much a bureaucrat sees themselves as a representative of the specific social group they serve is ultimately what determines whether and how much they will push for the rights and interests of that group’s members. Accordingly, when it comes to racial or ethnic minority groups, if a bureaucrat strongly identifies with the role of the “minority representative,” they are more likely to use their professional discretion in ways that represent the interests of their minority clients.

Relative to this, the issue of the salience of the identity in question also matters (Meier Reference Meier1993; Raaphorst, Ashikali and Groeneveld, Reference Raaphorst, Ashikali and Groeneveld2024; Thompson Reference Thompson1976). As each person is simultaneously a member of several social categories – race, class, gender, etc. – the identity that is most salient in a given policy implementation context is the one that is most likely to shape the bureaucrat’s behavior. For example, African-American public administrators who serve African-American communities are found to share the views of such citizens and to embrace the “minority representative” role significantly more so than their white counterparts do (Bradbury and Kellough Reference Bradbury and Kellough2008). This shows that identity matters not only as a descriptive characteristic but also, and perhaps more so, as self-understanding.

Migrant representativeness in Europe

The existing literature on representative bureaucracy has so far been primarily US-based and to a large degree focused on the notion of race (see also Bishu and Kennedy Reference Bishu and Kennedy2020; Kennedy Reference Kennedy2014). Although the representativeness of the EU’s agencies and top-level bureaucracies has been widely examined (e.g., Cingolani Reference Cingolani2023; Pérez-Durán and Bravo-Laguna Reference Pérez-Durán and Bravo-Laguna2019; Trondal, Murdoch and Geys Reference Trondal, Murdoch and Geys2015), fewer studies have focused on policy implementation and street-level dynamics (e.g., Guul Reference Guul2018; Jankowski, Prokop and Tepe Reference Jankowski, Prokop and Tepe2020).

In contemporary European scholarly accounts, ethnic identity takes the central stage to a greater extent than race (Delanty, Jones and Wodak Reference Delanty, Jones, Wodak, Delanty, Jones and Wodak2008). Racial and ethnic identities are, of course, practically intertwined, as is the discrimination based on the two. Everyday acts of race and ethnicity-based exclusion (e.g., staring or verbal rejection) are observed in the interactions of migrants with locals (e.g., Di Masso, Castrechini and Valera Reference Di Masso, Castrechini and Valera2014) and with state employees (e.g., Flam and Beauzamy Reference Flam, Beauzamy, Delanty, Jones and Wodak2008). European migration scholars have discussed the “racialisation of migrants,” where race plays a significant role in how migrants are seen and treated by both host society members and governments (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2005). This mix of xenophobia and racism has been described by some as “xeno-racism” (Delanty, Jones and Wodak Reference Delanty, Jones, Wodak, Delanty, Jones and Wodak2008; Fekete Reference Fekete2001; Sivanandan Reference Sivanandan2001). With this nuance in mind, the term “migrant representative” seems more appropriate for capturing representatives in the European context of migration management, as opposed to the term “minority representative.”

It is important to acknowledge here the great diversity of migrants in the EU, also considering the right to free movement within the Schengen area. This is associated with certain migration trends, from less to more wealthy countries, and certain social hierarchies across different migrant groups. For example, Germany is a host country for various migrant groups, some from Southern European countries and others from Middle Eastern countries. In practice, let us say, Greeks and Italians in Germany enjoy more legal rights (e.g., no visa requirements and automatic access to work) than Iranians and Iraqis. Moreover, as Europeans, they may also be seen as being more “compatible” with German culture. In that sense, it can be argued that migrants from Southern Europe may enjoy a higher status in Germany than migrants from the Middle East, the region from where most of the migrants who arrived between 2015 and 2017 originated (OECD 2018).

Different migrants may thus have different statuses within the same host society, depending on various factors, including nationality, race, and class. At times, this may also lead to instances of discrimination and racism across migrant groups. Fox (Reference Fox2013), for example, finds that Hungarian and Romanian migrants in the UK play into Britain’s racialized hierarchies to gain an advantageous position over other migrants. Despite being a target of xenophobia themselves, they use racism to distance themselves from Black and Roma migrants and emphasize their “Whiteness” to prove their deservingness to belong to the local society. The stratification among different migrant identities could therefore influence whether and to what extent migrant bureaucrats adopt the migrant representative role, depending on their own status within the existing social hierarchy (see also Groeneveld and Meier Reference Groeneveld and Meier2022).

Lastly, there is another aspect that has been overlooked in the existing literature: the fact that people increasingly refuse to put themselves into single identity categories. Instead, they may identify with more than one category or they may refuse to position themselves within the existing identification system altogether. This is more commonly the case in relation to ethnicity within Europe (e.g., Prümm, Sackmann and Schultz Reference Prümm, Sackmann, Schultz, Rosemarie, Bernhard and Thomas2003), but it is also true for race in the US (Tatum 1997/Reference Tatum2017), as well as gender (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2016). As these multi-ethnic, biracial, non-binary, and generally non-standard identities increase in frequency, they also become more relevant to scholarly research, including the field of representative bureaucracy. In migration management, the ways in which migrant bureaucrats place themselves across or between migrant identity categories are also bound to have implications for their discretionary behavior toward migrant clients.

Based on the theoretical discussion above, a set of expectations grounds the analysis that follows: a) not all migrant bureaucrats are likely to actively represent their migrant clients; b) migrant bureaucrats who see themselves as migrant representatives would be more inclined to actively represent migrant clients; c) the migrant identity is likely to be a salient identity in the context of migration policy implementation and during a time of a migration “crisis”; d) some migrant bureaucrats have a higher migrant status than others; and e) migrant bureaucrats may identify fully, partly, or not at all with their migrant clients.

Research methods

This research follows a qualitative methodological approach consisting of in-depth interviews with street-level bureaucrats who are “old” migrants, meaning they have been residing in the country of focus for at least 5 years prior to the data collection, and who deliver social services to newly arrived migrants. The data collection took place in Athens, Greece, and Berlin, Germany, between December 2015 and January 2019.

This study is part of a larger research project, totalling 149 interviews with street-level bureaucrats in migration management (79 in Athens and 70 in Berlin). Of these, 37 interviews were analyzed here, selected on the basis of participants having a migration background themselves (Table 1). This includes those who have previously migrated from other EU (13) and non-EU countries (14), as well as those who have dual nationality and have been raised in more than one country (e.g., Turkey and Germany or Albania and Greece) (10). Although at the initial stage of data collection migrant bureaucrats were not specifically recruited, being an “old migrant” emerged as an important and meaningful identity for research participants. Through both in-person visits to migrant housing facilities and the snowball technique, more migrant bureaucrats were subsequently located and asked to take part in this study.

Table 1. List of participants with migrant background

In terms of the policy implementation domain, participants primarily engaged with facilitating the delivery of social services to newly arrived asylum seekers staying in state-funded privately-run housing facilities, in the case of Germany (Chazan Reference Chazan2016), or state camps (Asylum Information Database 2017) and “housing squats” run by local activists (Georgiopoulou Reference Georgiopoulou2015), in the case of Greece. The services provided revolved around psychosocial care and legal aid provision. With a rapidly changing situation on the ground, participants’ daily tasks varied from one day to the next, depending on the given needs of newly arrived migrants (e.g. support with asylum application, access to medical care, or attendance of language courses).

All but two participants (who were public servants in Germany) worked in the third sector, either as NGO employees or grassroots group members. This is indicative of a recent trend toward contracting and privatization of human services, especially in the field of migration management, as well as the rise of a “welcome culture” during the early 2015–2017 “crisis” period, when many European citizens became spontaneously involved in the reception of newcoming migrants (Glyniadaki Reference Glyniadaki2021). Although participants in Germany were generally more likely to be officially employed than participants in Greece, due to a comparatively more formalized civil society (Ibid.), this varied, with participants holding positions in different organizations and groups over time, depending on the funding available, vis-à-vis their individual financial circumstances.

The data collection and analysis followed the Research Ethics Policy and the Code or Research Conduct of the author’s affiliated institution. The author acknowledges that her positionality as a white European citizen who resides in a relatively wealthy country and pursues a higher education degree at a known institution may have influenced her interactions with participants and therefore her research observations.

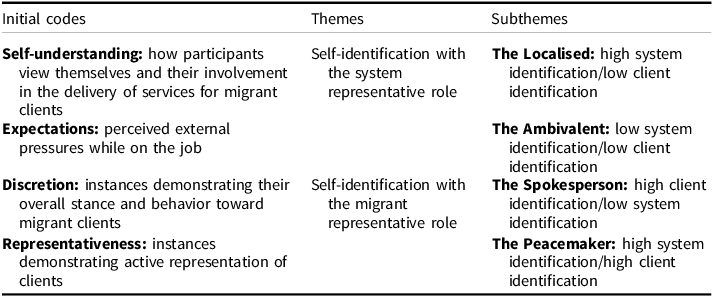

Semi-structured interviews took place at each participant’s place of work or nearby public location. A series of open-ended questions were asked, such as: What kind of responsibilities does your current role entail? What are some challenges you encounter when carrying out your daily tasks? What helps you find solutions? The duration of interviews ranged between 40 minutes and 2 hours. With the participants’ consent, the interviews were audio recorded. They were then transcribed verbatim and analyzed thematically (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006) using NVivo 11 qualitative research analysis software. The analysis steps were as follows: extensive familiarization with the interview data, generation of initial codes (“self-understanding,” “expectations,” and “discretion”), identification of themes (“system-identification” and “client-identification”), and subthemes (“spokesperson,” “localised,” “peacemaker,” and “ambivalent”) (Table A1 in Appendix), as well as revision and writing up.

Through analysing the participants’ subjective narratives (see also Portillo Reference Portillo2012), the aim of this study was to see how they understand and frame the unique experience of being both a migrant and a migration policy implementer. While the theoretical discussion of this paper precedes the presentation of the research findings, data analysis and theoretical development have occurred iteratively.

Migrant bureaucrats: Four profiles

To better understand whether and when migrant bureaucrats identify as “migrant representatives,” it is helpful to consider their alternative options. If not their clients, whom would they represent? This study suggests “the system.” This is the term participants used to describe the broader migration management mechanism in their respective cities, referring to relevant policies, services, and bureaucratic procedures, and often including local implementing actors. At a time of “crisis,” when the demands for migrant services considerably outweighed the available supply, the “system” did not adequately serve migrants’ rights. Migrant bureaucrats therefore had to meet their clients’ needs while operating in a system that is not sufficiently supportive of migrants. While this tension is known in street-level service delivery (state-agent vs. citizen-agent narratives – Maynard-Moody and Musheno Reference Maynard-Moody and Musheno2003), it is even more pronounced during a “migration crisis,” when the migrant identity is more salient, leading to heightened performance pressures for migrant bureaucrats (see also Gilad and Dahan Reference Gilad and Dahan2021).

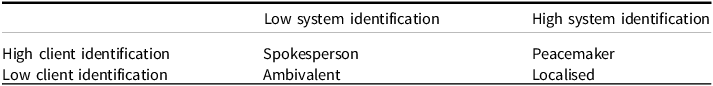

Through the analysis of interview data, this study finds that, when facing this contradictory set of expectations, of being both a migrant representative and a system representative, migrant bureaucrats may embody one of four different profiles. These profiles are named here: “spokesperson,” “localised,” “peacemaker,” and “ambivalent,” each corresponding to different levels of identification with the system and with the clients, as Table 2 illustrates.

Table 2. Profiles of migrant street-level bureaucrats: system and client identification

The “spokesperson” profile describes a migrant street-level bureaucrat who identifies more with their clients than with the system and is willing to bend the rules to meet the clients’ needs. The “localised” migrant bureaucrat is one who sides more with the system than with the clients, seeing themselves as an enforcer of the local rules and norms. The “peacemaker” is a migrant bureaucrat who feels equally close to the system and the clients and aims to ease interactions between the two sides. Finally, the “ambivalent” migrant bureaucrat is one who struggles to take a clear stance between the system and the clients, feeling stuck in the middle.

These four profiles correspond to varying degrees of identification with the migrant representative and the system representative roles, shaping accordingly the chances of turning passive representation into active representation. Those who fit the “spokesperson” profile identify more strongly as migrant representatives, while those with the “localised” profile see themselves primarily as system representatives. “Peacemakers” identify with the migrant representative role as much as they do with that of the system representative, whereas those fitting the “ambivalent” profile do not fully identify with either category. Passive representation is therefore more likely to turn into active representation for migrant bureaucrats who embody the spokesperson profile and less likely for those with the localized profile. Those with the peacemaker and ambivalent profiles are somewhere in between these two ends.

Four profiles in practice

To illustrate the observations above, there follow the examples of four participants, herein named Zena, Genti, Joan, and Leila, each representing one of the profiles described above.

Profile A: Zena, the “Spokesperson”

Zena was once a refugee child. In the early 1990s, her Russian mother and Iranian father fled with her to Sweden, where she subsequently grew up. In 2013, in her mid-30s, Zena moved to Berlin, attracted by the city’s vibe. She learned German quickly and decided to work as a social worker at a shelter for migrants. This way she could use her Swedish social work degree, while also working toward a cause she cares about: helping refugees.

On the job, Zena was surprised to discover that social services in Germany are largely privatized. She found this problematic:

From my boss’s point of view, we are contract partners with this [government] authority and need to execute their will. From my professional point of view, I am the social worker of the people who are quite often in conflict with this authority. Of course, this is a completely unrealistic situation; either you stay focused on your clients, which will, at some point, mean that you will be uncomfortable towards your profit-driven bosses, or you stay in line with the policy of the company, but then you are actually not producing good social work.

This quote illustrates the conflict between the expectations of Zena’s boss versus those of her migrant clients, exemplifying the tension between being a system representative and a migrant representative. In this conundrum, Zena takes a clear stance: she is with her clients. She disputes the term migration crisis by emphasizing that “it is humans we are talking about,” and she explains that most asylum applicants have not found themselves in Berlin by choice but have been uprooted and feel homesick. She expresses the migrants’ perspective.

Zena is also critical of the local Berlin authorities, describing their lack of responsiveness as “appalling.” Although social workers may contact a designated governmental office with inquiries about their clients’ needs, rarely does anyone pick up the phone or respond to their emails. She calls this a “void” and a “black hole.” She also describes the exhausting process of asylum determination, the poor food quality at the shelters, and the hostility from locals, commenting that none of these factors contributes to migrants’ integration. Once again, she sides with her migrant clients and not with the “system.”

Turning her words into actions, Zena takes on a migrant-representative role and becomes the “spokesperson” for migrants, using her professional discretion to defend migrants’ rights, even if that means disregarding system rules:

We don’t do the room controls which we are supposed to do… which means going into people’s homes and looking to see if they are clean or not… We say [to our bosses that] we do, we have to, but we don’t…We don’t always count [the nappies] we give out. We trust people… [And], as much as we can, we try to stop deportations by warning our clients. When we get phone calls and we understand […] We warn our clients.

Zena and her like-minded colleagues do their best to assist their migrant clients, at times going as far as to “warn” them, so as to prevent their deportations.

Over time, Zena’s friction against “the system” escalates. She discusses an instance of a government order which only allowed migrants with high prospects of being recognized (e.g., Syrians) to cook their own meals in the shelter kitchen, whereas for the rest there would be (poor quality) catering. Despite this regulation later being withdrawn, Zena’s boss continued to ban migrant residents from using their kitchens. Residents complained. Without hesitation, Zena took sides:

It became a pretty open conflict where we had to take a side, and we decided to take our clients’ side… Our clients had a demonstration exercising their right to express their opinion on the street. Like every other German person [would]. And instead of seeing that this was maybe a very good note for the integration work that we have been doing, it was looked upon as something very bad by my bosses who came together with [the local government agency] and tried to stop this, and tried to force us to make our clients shut up, which we refused.

Yet another dispute with her boss followed this incident and Zena was reprimanded for helping organize a protest. This example demonstrates Zena’s high identification with her migrant clients and low identification with the local migration management “system” in Berlin. It also shows another instance of passive representation turning into active representation.

As we see from Zena’s profile, the “spokesperson” is a migrant bureaucrat who views themselves as a migrant representative. Zena recognizes the conflicting demands of working to serve migrant clients while simultaneously being paid by a system which does not prioritize migrants’ rights. Zena stands by the migrants, acting as their representative and spokesperson. Compared to her clients, Zena has a higher migrant status because she has migrated by choice and, as an EU citizen, she is in an advantageous position in terms of freedom of movement and access to work. Taking advantage of this status, she goes out of her way to support migrant clients, thereby actively representing their needs and interests.

Profile B: Genti, the “Localised” migrant bureaucrat

Genti moved to Greece from Albania in 1991, as a young adult. While relieved to escape a country in chaos, he found that the receiving society was not exactly welcoming. Although the developing economy allowed for the absorption of low-paid labor, xenophobia was rampant. Genti had spent five years struggling with overt discrimination when he came across the “network for the support of immigrants and refugees” in central Athens. He describes this as an eye-opening and heart-warming experience: “Until that point, I did not believe that there could be even one Greek who might see [Albanians] as human beings. I had just been through so, so much racism.” Genti became and remained a network member.

In the summer of 2015, when migrant flows to Greece reached a record point, the network initiated a solidarity movement for refugees and immigrants, an effort joined by newly mobilized parts of mainstream society. Identifying with the migrant experience, Genti found himself at the front lines:

While I was not forced out due to war, I was forced out due to deprivation, it was hope that ‘pushed’ me towards a better life… So, because I have already lived this, being in a foreign country without anything and without having any support – maybe because we were the first bunch of migrants in Greece back then in 91 – so, ok, we got some experience from hardships etc., so we can maybe make it a little easier for them.

Like newcomers, Genti had migrated out of need, not choice, which motivated him to try to ease the hardships newcomers were facing.

Nonetheless, by taking part in the solidarity movement, Genti came to see himself as a local “solidarian.” He became involved in running the largest “housing squat” for migrants in central Athens. Once an abandoned hotel, the building now hosted approximately 400 migrants. On a regular basis, Genti performed a variety of tasks: maintenance work, security shifts at the gate, service work in the reception area, and attendance at assembly meetings.

Two years into this demanding routine, Genti describes his involvement with great enthusiasm and pride. He recounts the positive attention the initiative attracted from international media outlets and the numerous encounters with high-profile visitors, including Judith Butler and Manu Chao. The work of solidarians was also praised by the Greek migration minister (Giannarou Reference Giannarou2016), despite squatting being illegal. As a “solidarian,” Genti was part of something bigger. With the movement gaining momentum and exposure, Genti’s photo appeared in magazines and online videos in various countries. “I felt like George Clooney,” he says in a humorous tone and with an expression of self-satisfaction.

By contrast, when Genti discusses his interactions with migrants, he does not seem equally pleased. “They have some things that, for us, are not understandable,” he tells me, pointing his index finger at me and then back to him, in repetition. His account continues with a long list of issues that he finds problematic about migrants: racism between ethnic groups, low education, excessive levels of religiosity, sexist behaviors, gender-based violence, irresponsible parenting, lack of appreciation for solidarians’s efforts, and a curious sense of entitlement. His words below encapsulate the latter.

One thing they do, which is quite annoying – other solidarians have also told me this – is that they keep saying: “You know what we’ve been through.?” Okay, yes, but you see this coloured, like in a film, through a shiny filter. Okay, you’ve been through a lot. But sitting there being miserable about it and making it like now you have to treat me well, because of what I’ve been through, doesn’t work. It is just annoying.

Using an “us versus them” distinction, Genti criticizes new migrants and sides with solidarians.

In his interactions with new migrants, Genti urges them to “correct” their behavior and align it to the requirements of the European value system, as he understands it:

I have told them. Their mentality due to religion, etc., is in a very different direction from that of the locals. They came to Europe. Europe is not going to change for you. Don’t insist. You are the one that has to change. I am not saying to get rid of your culture, but some things that are not compatible, some stupid stuff that the Quran says or whatever … you have to change them! Otherwise, you are automatically getting yourself excluded. You will be standing out and…it can’t be otherwise. You have to adjust!

In this instance, too, Genti conveys a self-view that is much closer to that of a system representative than to a migrant representative. Being an Albanian and a manual laborer, Genti has carried a lower-status migrant identity and has been considered an outsider in Greek society. By participating actively in the solidarity movement for refugees and immigrants, he is claiming a place together with the locals, cultivating his own sense of belonging. One way to be seen as a local is to stand with the locals and operate as an enforcer of local norms, values, and practices during his interactions with the new migrants.

Genti identifies as a migrant but not with the migrants. By suggesting that the migrants should change and become more “like us,” he positions himself as a representative of the system rather than as a representative of the migrants, casting himself as a “localised” migrant bureaucrat. In this case, passive representation does not lead to active representation.

Profile C: Joan, the “Peacemaker”

Joan, 23, was born in the UK to Greek Cypriot parents and raised in a privileged social environment in North London. Her mother was once a refugee, having fled Cyprus when Turkish forces invaded the island in 1974. Growing up, Joan often had the chance to visit Greece and Cyprus for holidays and family visits, which helped her become fluent in Greek. She holds a bachelor’s and a master’s degree from reputable UK universities, both on human rights and works for a local NGO in Athens, assisting unaccompanied migrant minors.

Her involvement with migrants began in the summer of 2015, with the humanitarian crisis in the Aegean. Holidaying on a Greek island elsewhere, Joan could not look the other way. She changed her travel plans and went to Lesvos, where she ended up spending the rest of the summer volunteering in highly chaotic and violent-prone conditions. She remembers that stressful period: “Having to pull children who have come to Greece as refugees out of tear gas on a day-to-day basis…It just takes a toll on you.”

Joan places high emphasis on the needs and rights of migrants. Simultaneously, she feels comfortable around local authorities and is able to converse with them with ease. When needed, she takes on the role of an intermediary between the two sides:

Say [the UNHCR field administrator] has an opinion opposite to [that of] the police, she would send me to go to speak to the police because her job disallowed her from going to talk to them. She wasn’t allowed to tell them to stop the riots. She just had to stand there and watch the riots. While we [the independent volunteers] were allowed to go in there and argue with the police.

In this instance, Joan acts as a middleperson between law enforcement and migrant rights representatives.

At the end of that summer, Joan moved to Athens, where she could spend more time assisting migrant families, primarily from Syria. An abandoned school building near her family house had just been occupied by local activists and turned into squatter housing for nearly 300 migrants. Joan found this a convenient opportunity to help “make a difference.” For months, her daily tasks included registering migrant children at school, counselling teenagers, assisting with the building’s restoration needs, and holding night shifts to help keep away fascists and prevent police eviction efforts. Moreover, she regularly accompanied residents to medical appointments:

We would not abandon these people in terrible Greek hospitals as they could be there for hours because they didn’t have someone that spoke Greek. We noticed that things got done a lot quicker when someone Greek was with them. So, my friend [Maria] and I were always at the hospital for appointments with people.

Joan here describes herself as a local Greek who is using her language skills to ease challenging healthcare encounters migrants can face. She can thus be seen as a migrant bureaucrat who adheres to the migrant representative role, prioritizing the interests of her clients.

Nonetheless, in other instances, Joan also describes her role as complementary to that of governmental and intergovernmental organizations, which indicates she also sees herself as a system representative. In the quote below, she argues that migrant squatter housing essentially functions to fill state gaps.

The reason the squats have been open until now is because the government needs us to be open, because they don’t have a place to put all these people. As soon as they have a place […]. [the migrants] will leave.

In her view, street-level bureaucrats such as herself are essentially assisting the Greek government to meet its legal obligations to asylum seekers, something the state seems unable to achieve on its own. Cognisant of this, Joan operates as a de facto arm of the state.

Joan’s family history and education have sensitized her to the migrant experience and made her aware of migrants’ needs. At the same time, her multi-ethnic identity, her familiarity with the Greek language and culture, and perhaps her looks allow her to pass as a local while in Greece. Coming from a relatively privileged British upbringing, Joan finds meaning in assisting both migrants and the state. She finds ways to make use of her time and skills to help both sides, wanting to “make a difference” in a time of crisis.

Joan is a high-status migrant who sides with both the local migration management system and her migrant clients, often operating as an intermediary between the two. She thus identifies with both the system representative and the migrant representative roles, managing to either combine the two or switch with ease from one to the other. Joan’s profile is that of the “peacemaker” migrant bureaucrat. This position indicates higher levels of active representation compared to the localized profile, but perhaps not as high as the spokesperson profile.

Profile D: Leila, the “Ambivalent” migrant bureaucrat

Leila, 24, is Syrian and works as a Sozialbetreuer or “social carer,” at a shelter for migrants in Eastern Berlin. She is also studying for her master’s degree in English Literature. Leila moved from Syria to Germany together with her family in 2013, a few years before most of her co-nationals. “I came here legally,” she informs me, pointedly, although this was not something I was planning to ask. Leila had already had German lessons at home for two years prior to her journey, so language was not a barrier to her transition. Her education, clothing, and general remarks point to a person from a higher socio-economic background.

Along with assisting the shelter’s residents with their everyday needs, including bureaucratic, medical, and educational appointments, and paperwork, Leila also translates for them. While combining these duties, she often finds it difficult to assert her role as a policy implementer and a system representative in the eyes of her migrant clients.

Sometimes, they don’t take me seriously as a decision-maker, or a person who knows information. So, when I tell them that this doesn’t work like this, like seriously this is not allowed… they ask to talk to my boss, for example, instead. They find out that it is the same result, my boss says the same thing, but… They assume… That I don’t really know much about whatever they are asking about.

Phrases like “this doesn’t work like this” and “this is not allowed” are meant to convey the existing rules to the migrant clients, be they organizational regulations or state law. Her effort to fulfil the requirements of the system representative role is met with resistance from her clients, who do not seem to acknowledge her as such.

Moreover, Leila often finds it difficult to connect with her clients, which also inhibits her from fully seeing herself as a migrant representative.

I come from the same culture, but they come from different environments, within the same country, that I haven’t necessarily had contact with, even when I was there myself… the language they use when they ask questions, or when they want something, is not necessarily always nice. […] Some of them expect that we have to do everything for them… or expect that we are here as servants or something. The language implies this. And I always excuse them because I know that not everyone has had the same educational chances, for example, or they were not all raised the same way…

It becomes apparent here that Leila does not identify strongly with her migrant clients. Since they come from “different environments” or because she disapproves of their manners, their relationship is somewhat uneasy.

Incumbent in this tension is a struggle to belong to local society. While Leila is working to increase her “Germanness,” her clients expect her to follow the stereotypical behaviors of an Arab woman. Inevitably, this constitutes an additional challenge in her daily work.

I have also been Germanised, in a way, because I learnt a lot about Germany. That you have to be direct but also very polite. You can never say “Do this” or “Do that”. In Syria, it is different […]. The problem is always because Syrians are indirect when they have to complain about something, I cannot directly say, “This is not like this, you have to respect me”, because I am an Arab, and they are Arab. They will understand it differently, because in an Arab country, you don’t criticise directly. In Germany, you criticise directly. I am in Germany but I am not a German…

Leila’s “Germanisation” process seems to be hijacked by the primary image her clients have of her, that of a fellow-Arab woman, as well as the behavioral expectations that come with it.

In her effort to establish her Germanness and her role as a system representative, Leila encounters one more struggle: her colleagues fail to understand and acknowledge her perspective.

We always have conflicts because of this… My German colleagues don’t get my point on why I can’t be direct. They don’t get it. […]. This is one big issue for me.

Although, when discussing her interactions with her migrant clients, she referred to herself as “Germanised,” the difficulties in her interactions with her local colleagues suggest that she is perhaps not yet fully “Germanised.”

As Leila’s case illustrates, there are migrant bureaucrats who, in their effort to belong to the host society and to help newcomers do the same, face constant challenges on both fronts. Leila reports feeling like “a buffer between the two [sides]” and cannot identify fully with either the migrant representative role or the system representative role. She therefore embodies the “ambivalent” migrant bureaucrat profile. This indicates a relatively low degree of active representation.

Discussion and conclusion

This study has sought to examine the linkage between passive and active representation (Thompson Reference Thompson1976) by focusing on the context of migration management in two European capitals, Athens and Berlin, and the conditions where migrant street-level bureaucrats deliver services to migrant clients. In doing so, it has made a two-fold contribution to the existing literature. First, it has drawn attention to the representation of an identity category that has so far been overlooked, namely, “migrant” identity. Building on the concept of “minority representative” (Bradbury and Kellough Reference Bradbury and Kellough2008; Selden Reference Selden1997; Selden, Brudney and Kellough Reference Selden, Brudney and Kellough1998), it has introduced the concept of the “migrant representative,” which is more fitting in the context of migration policy implementation, especially in Europe. With both terms, the premise is that street-level bureaucrats who see themselves as representatives of their clients are more likely to actively represent the interests of the latter.

Second, elaborating on this under-researched dynamic whereby “old” migrants are serving “new” migrants, this study has offered a more nuanced analysis of the degree to which migrant street-level bureaucrats may embrace the migrant representative role and the corresponding implications in their discretionary behavior toward migrant clients. Drawing from interview data with migrant bureaucrats during the so-called migrant “crisis” of 2015–2017, this research has found four profiles of migrant bureaucrats – “spokesperson,” “peacemaker,” “localised,” and “ambivalent” – each corresponding to a different degree of self-identification with the local migration management system and with migrant clients. Depending on whether migrant bureaucrats see themselves as representatives of the system (localized), the clients (spokesperson), both (peacemaker), or neither (ambivalent), they adopt a more or less favorable stance toward migrant clients.

From the theoretical discussion on representative bureaucracy, it follows that the more migrant bureaucrats embrace the role of the migrant representative, the more likely they are to meet their migrant clients’ interests, thereby turning passive representation into active representation. This study additionally shows that embodying a client representative role is not simply a matter of yes or no, but it may reflect the simultaneous embodiment of different identities, in this case, the system representative role as well as varying degrees of identification.

Listing all the factors that may push individual migrant bureaucrats to identify with each of the four profiles is not within the scope of this article, but there is one individual characteristic which has appeared to play an important role and which was not initially anticipated: migrant bureaucrat status. Because of the legal rights associated with their nationalities (e.g., more rights for EU nationals), their class (e.g., high socioeconomic background), or the way in which they are perceived in the local society (e.g., as culturally compatible), some migrant bureaucrats may enjoy a higher status than others. Higher-status migrant bureaucrats, this study finds, are more inclined to see themselves as migrant representatives and use positive discretion toward migrant clients (see also Belabas and Gerrits Reference Belabas and Lasse2017; Glyniadaki Reference Glyniadaki2024; James and Julian Reference James and Julian2021), exactly because they have a relatively greater sense of security.

Conversely, low-status migrant bureaucrats who are concerned about their own social standing in the local society may be less inclined to actively represent their migrant clients. Questioning or going against a local migration management system that does not prioritize migrants’ rights presents a greater risk for them. This risk may involve compromising their own legal or social status as migrants or potentially lead to further social exclusion. The case of migrant bureaucrats not being particularly supportive of migrant clients is similar to that of women or minority bureaucrats within an organization being less likely to use their discretion to the advantage of women or minority clients, either because they lack the power or because they want to avoid risking their own professional status (Assadi and Lundin Reference Assadi and Lundin2018; Portillo Reference Portillo2012; Watkins-Hayes Reference Watkins-Hayes2011).

The observation that low-status migrant bureaucrats are less inclined to take on the migrant representative role partly echoes findings of recent studies that specifically examine the role of the status of bureaucrats in representative bureaucracy (Raaphorst, Ashikali and Groeneveld Reference Raaphorst, Ashikali and Groeneveld2024). At the same time, however, it contradicts existing arguments that suggest that a lower status distance between bureaucrats and clients facilitates and enhances the quality of interaction, thereby leading to more effective service delivery and more active representation (Groeneveld and Meier Reference Groeneveld and Meier2022). Further research on the role of bureaucrats’ status could help shed light on this debate.

More generally, by focusing on migrant bureaucrats in Europe and their subjective narratives, this study has responded to calls for greater use of qualitative research methodology in representative bureaucracy, and for the analysis of data that is not US-centered, and which goes beyond the commonly used social categories of race and gender (Bishu and Kennedy Reference Bishu and Kennedy2020; Moloney, Sanabria-Pulido and Demircioglu Reference Moloney, Sanabria-Pulido and Demircioglu2023; Rivera Reference Rivera2016; Strader et al. Reference Strader, Griffie, Irelan, Kwan, Northcott and Sanjay2023). The chosen approach addresses a social context that has so far not been analyzed from this theoretical and methodological angle. This has several advantages, as discussed above, but it also comes with caveats and limitations.

Returning to the four migrant bureaucrat profiles this study has identified (Table 2), it is important to note that they do not constitute clearly demarcated and fixed categories. This is to say that, over time, migrant bureaucrats may change the degree to which they embrace the migrant representative identity and therefore their stance toward migrant clients, for a number of reasons. For example, as already noted, the landscape of service delivery for migrants in most major European cities is diverse and fast-changing, with different policy programs having varying amounts of funding at different times. In practice, this means that migrant bureaucrats may not always have equally secure employment status, which suggests that their status distance from migrant clients, and therefore their discretionary behavior toward them, may also fluctuate over time. The research methods used in this study could not adequately address this meaningful longitudinal dimension.

Accordingly, the micro-level focus of this research means that there are also other important aspects that could not be captured in their full complexity. Indicatively, the stance of migrant bureaucrats toward migrant clients, and the degree to which passive representation translates into active representation, may also be influenced by factors such as contextual idiosyncrasies (e.g., the extent to which civil society is formalized in one host country as opposed to in another), societal pressures (e.g., the rise of far-right parties and ideologies), or even client characteristics (e.g., Middle Eastern vs. Ukrainian migrants). These could be examined in further detail by future studies.

Finally, future research could also further examine the main observations brought forward by this study. From a representative bureaucracy theoretical perspective, the migrant identity, as a shared identity between street-level bureaucrats and clients in the delivery of migration policies, could be explored in greater detail and in more countries and contexts. Moreover, the four profiles of migrant bureaucrats established here, as well as the ways in which bureaucrats identify with the migrant representative or system representative roles, and the implications of that pattern formation for the active representation of migrant clients, could also be examined further. This is the case not only at the frontlines of migration management but also beyond.

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods and no replication materials are available.

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by the Hellenic Observatory, at the London School of Economics. It has benefited greatly from the comments and feedback of Martin Lodge, Sharon Gilad, Jonathan Turner as well as the two anonymous reviewers.

Competing interests

No conflict of interest to declare.

Appendix

Interview guide:

-

1. For how long have you been engaged with migrant-related issues? And, what made you decide to get involved?

-

2. Can you tell me a few things about your current role and the specific activities in which you engage?

-

3. What are some difficulties or challenges that you face in relation to the daily activities you just described? Can you give me 1 or 2 specific examples?

-

4. When you are facing such types of challenges, what helps you make the difficult decisions that you need to make? Are there certain guidelines or criteria that you have in mind?

-

5. Can you describe for me a specific example of a case that you found particularly challenging? How did you handle it?

-

6. Is the way you handle such cases similar to how your colleagues would handle them? In other words, would you say your approach is in accordance with your organization’s values?

-

7. In your interaction with refugees and migrants, have you come across any significant differences (e.g. in social or cultural values)? Can you think of a particular example?

-

8. From your perspective and your experience, have things changed over time in relation to the management of migration locally? If yes, in which way?

-

9. If you were to turn back time, would you handle certain cases differently from how you handled them? If yes, how?

-

10. Are there any things, that are not dependent on you, but if they were to change, would help make your job easier and more effective? Examples?

-

11. Is there anything else you would like to add?

Table A1. Coding summary