In 1932, US government inspectors certified as useless the holdings of the Napa Valley winery Montelena. In the cellar of the great house built to resemble Bordeaux’s Chateau Lafite, a wooden tank holding a pre-Prohibition vintage had earlier fallen prey to worms that ate their way through the staves, spilling the once-prized wine onto the floor. Upon examination of all the holdings, men from the US Treasury determined the liquid unfit for human consumption, possibly not worth even making into vinegar.Footnote 1 Although Prohibition had not ended wine drinking in the United States—grape growers continued to sell fruit to home hobbyists hoping to make something like wine, and a few commercial winemakers continued supplying sacramental wine to religious establishments—the great experiment in temperance scuttled the ambitions of vintners like Chateau Montelena, who wanted to make wines fit for a connoisseur’s palate, rivaling the greatest products of the Old World.

Yet just over 40 years later, a 1973 Chateau Montelena chardonnay won the international blind tasting test popularly known as the Judgment of Paris, proving—along with the other California winners—that the state’s wines now ranked among the best in the world. After that 1976 tasting in Paris and the media coverage that ensued, California wines competed with the top Italian and French vintages. What once had been undrinkable was now, and for the foreseeable future would remain, highly desired.Footnote 2

That swift rise of California wine got under way owing considerably to the actions of the state—policies of both the United States and California, often written in cooperation with or at the request of winemakers. The state destroyed winemakers’ ambitions during Prohibition, and after repeal it was to the state that California’s vintners turned, seeking aid from the New Deal of the 1930s and pursuing government intervention to stabilize prices, ensure quality, provide loans and grants, and build infrastructure. The New Deal for wine included policies much like those that characterized the New Deal generally, and it received the same welcome in wine country as the New Deal did nationwide—while also, like the national New Deal, benefiting some constituencies more than others. Wine had a unique place in the New Deal, at the intersection of domestic and international, agricultural and industrial and even serving as a component of the administration’s conception of a better life for Americans putting both Prohibition and the Depression behind them. The recovery of the wine industry followed a pattern that was similar to that of overall economic recovery under the New Deal. Americans’ legal consumption of wine increased rapidly after 1933, exceeding its pre-Prohibition level by the end of Roosevelt’s first term and continuing apace—with an interruption for the 1937–38 recession—up to the war, making possible the still more successful decades that followed.Footnote 3

Scholars currently claim that the state contributed to the success of the California wine industry by getting out of entrepreneurs’ way, arguing that such federal involvement as remained after repeal only impeded progress. As one standard history has it, the Roosevelt administration “engaged in controlling the wine industry … largely in a nay-saying way” and “had no interest in” the wine industry, “except as it might be made to pay taxes.”Footnote 4 The historiography of US winemaking focuses principally on individual winemakers or tastemakers; even when considering the role of the state, it generally takes little notice of New Deal efforts beyond taxation.Footnote 5

In this article we demonstrate instead that by regulating, promoting, and protecting the wine industry, the federal government provided a framework for California winemakers to succeed and frequently did so at their request and with their cooperation. The state of California implemented related policies. Vintners wanted what one lobbyist called a “new deal for wine consumers”—which also entailed a new deal for wine producers.Footnote 6 Some New Deal policies, including taxation, tariffs, public works, scientific research, and image promotion, helped many different groups within the wine industry: workers and employers, small producers and major corporate wineries alike. On the other hand, some policies helped bigger companies at the expense of smaller ones or business owners and industrial laborers at the expense of farm workers. The New Deal for wine provides a useful case study in how the Roosevelt administration balanced priorities—industry against agriculture, domestic against foreign policy, recovery against reform—in charting a path out of the Depression. Overall, although New Deal policies did not benefit all stakeholders equally, they did contribute to economic recovery for an industry suffering from both Prohibition and the Depression and established a basis for still more improvement later. With repeal in 1933, the long-shackled Bacchus of California winemaking was unbound, but it took public assistance to get him up on his feet.

Repeal

Most Americans greeted Franklin Roosevelt’s victory in the presidential election of 1932 with hope, but no business group had greater expectations of the nascent New Deal than the alcoholic beverage industry. The Democratic Party platform of 1932 promised the unqualified repeal of Prohibition. Because it would take months for three-quarters of the states to ratify a constitutional amendment, the platform also proposed immediate modification of the Volstead Act—the federal law enabling enforcement of Prohibition—to permit production and sale of lightly alcoholic drinks. Roosevelt campaigned on this pledge as part of the New Deal; repeal, his campaign flyers told voters, would “give back jobs to thousands.” The Democrats swept the elections, and the new Congress sent the Twenty-First Amendment to the states at the end of February. Nothing further could be done so long as the dry Herbert Hoover remained in the White House, but once the new president took office in March, while the nation’s drinkers awaited ratification of repeal, Congress revised the law to permit the sale of beer at 3.2% alcohol by volume.Footnote 7

Alcohol manufacturers praised the new president and his program. According to one survey of industry leaders, the spirits, wine, and beer makers felt grateful to the Democrats and shared “a sense of obligation toward this political party and this administration who put them back in business.”Footnote 8 One hopeful winemaker, Sophus Federspiel, president of the Grape Growers League of California, told his colleagues, “No industry should respond more readily to [Roosevelt’s] appeal for cooperation in reemployment, increased wages, and restoration of national prosperity…. Grape growers and wine makers alike are already getting the benefits of the New Deal and bright days are ahead.”Footnote 9

Anticipation provided the first vital spur to recovery, inspiring new applicants for winemaking permits to join the wineries that had clung to business during Prohibition by making still-legal sacramental or medicinal wine and industrial alcohol. By the time Utah provided the last vote needed to rescind the Eighteenth Amendment on December 5, 1933, California held 380 bonded wineries—more than twice as many as had been operating at Roosevelt’s inauguration.Footnote 10 These California wineries constituted the vast majority of American wine producers. The Golden State made about 85% of the wine produced in the United States and grew 90% of the grapes.Footnote 11 The industry was vital to the state’s economy: about one in 25 Californians depended directly or indirectly on wines and grapes for a living.Footnote 12

Yet most winemakers would not shift easily to the new era of alcohol control. For a start, Americans did not prefer wine over other intoxicating beverages, even when they could legally drink it. Before Prohibition, on a volume basis, beer represented approximately 90% of alcoholic beverages consumed from 1900 until Prohibition began; spirits accounted for 7%, and wine trailed them both at 3%.Footnote 13

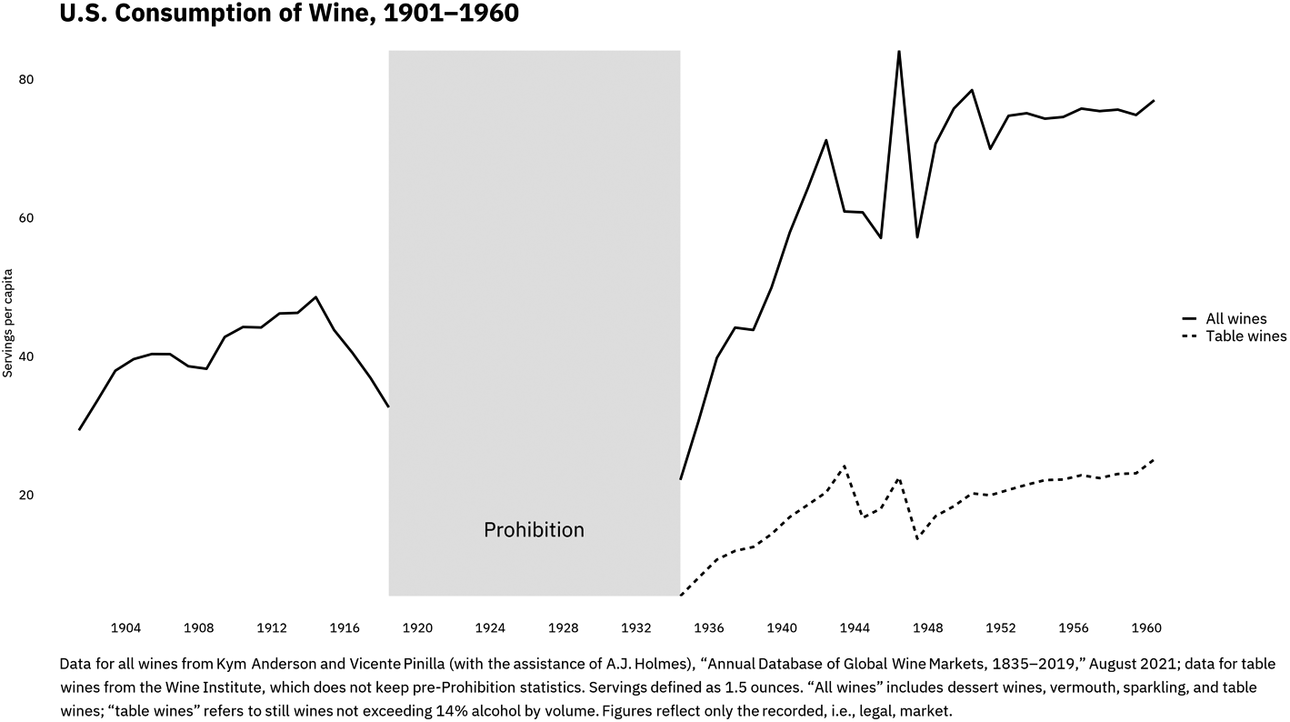

Prohibition shaped the wine market in two ways that posed challenges to commercial winemakers following repeal. First, a loophole in the Volstead Act permitted Americans to make up to 200 gallons of wine for personal consumption. Consequently, a substantial market in home enology sprang up during Prohibition. Second, at the same time, Americans’ tastes shifted decisively toward sweeter, higher-alcohol wines; under the ban on booze, drinkers sought bang for buck in their illicit intoxicants, not a tasteful complement to their main course. As one wine industry executive explained, “My generation was the Prohibition era, so all we drank was bootleg whiskey and bathtub gin and things of this nature. That’s what took so long, to educate our generation to the use of wines, because our generation had completely escaped that.”Footnote 14 After repeal, commercial winemakers hoped to reverse both trends, luring home winemakers back into the commercial market and persuading wine drinkers to return to commercially made dry table wines (which, tellingly, they had come to refer to as “sour”). The New Deal helped with both: the commercial market for wine expanded rapidly during Roosevelt’s first two terms, and table wines constituted an increasing share of that market (see Figure 1).Footnote 15

Figure 1. U.S. Consumption of Wine, 1901–1960.

On the production side, as the mass of Americans forgot how to drink quality wine, the mass of vintners neglected the craft of making it. Many of the nation’s best enologists left the business or the country during Prohibition. Some, like those at Chateau Montelena, let their equipment deteriorate; others uprooted their vines and replanted their fields with grapes that would produce the hardy, sweet wines preferred by America’s new generation of home winemakers. Vintners in the US stopped tracking European technological or scientific innovations in viticulture and enology: there was no profit in improving the product. The 1930s saw the resumption of substantial public investment in the science of winemaking.Footnote 16

Beyond the challenges of retraining American palates and relearning enological skills, postrepeal winemakers faced the diverse regulatory and tax environments that sprang up after Prohibition. Some states remained dry after repeal. Interstate transporters of alcohol had to skirt their borders, and commercial airlines stopped serving when flying over dry territory. States that did allow alcohol sales followed different models. Some imposed a publicly owned monopoly on the alcohol trade, allowing only state-run retailers to sell intoxicating beverages; others established a licensing regime with regulations and taxes for private vendors. Each state made its own decisions with respect to the time, place, and manner of alcohol sales. California winemakers thus faced a variety of challenges as the age of alcohol control dawned—and they looked to Washington, DC and to Sacramento for help.

Regulation

Winemakers wanted government first and foremost to regulate, however counterintuitive it may seem. Most established vintners urged government officials to police their industry and expel tax cheats, adulterators, and fraudsters. They hoped federal and state governments could thus help reestablish public trust in the health and safety of their product.

The National Recovery Administration, set up by the National Industrial Recovery Act of June 1933, wrote the first rules for the reborn wine industry. The National Recovery Administration sponsored industry-wide cartels that brought regulators, management, and—at least in theory—labor and consumers together to draft codes determining basic conditions of manufacture and sale, seeking to restore prices and wages to levels that would maximize employment.Footnote 17 Alcoholic beverages came under the Federal Alcohol Control Administration (FACA), established by executive order a day before nationwide repeal, December 4, 1933, to oversee implementation of these codes for the alcoholic beverage industry.Footnote 18 The code for the wine industry followed shortly afterward, upon application by the Wine Producers Association, and was approved by the president on December 27, 1933. Drafted in haste, the code included no labor provisions beyond the bare minimum required by law—the National Industrial Recovery Act mandated recognition of workers’ right to organize and bargain collectively. Provisions for maximum working hours or days would come later. The initial code reflected industry priorities: a rigorous division of makers from sellers, regulation of prices, and a ban on false or misleading advertisement or branding of wine to mislead the purchaser as to its identity and quality. The federal government would issue permits to make wine and inspect facilities to determine their compliance with standards of safety, quality, and hygiene.Footnote 19

Far from objecting to these new standards, the alcoholic beverage industry urged them on the Roosevelt administration. As the chief of the federal Beverages Code Section wrote, industry leaders wanted Washington to “hold in check any irresponsible or too-aggressive member or members who might otherwise seriously and permanently hurt their industry by rushing madly into intense competitive methods to get distribution and sales, regardless of the public welfare or the good of their own industry.”Footnote 20 These producers did not want a free marketplace; they wanted stability, imposed by the federal government.

The California vintners’ trade association, the Wine Institute, organized in 1934, frequently expressed its members’ appreciation for the New Deal’s role in stabilizing and standardizing their industry. In December 1934, Harry Caddow, secretary of the Wine Institute, reported to readers of the California Chamber of Commerce journal that the FACA administrator had “surrounded himself with able official personnel” and understood from the start “the necessity of minimizing the amount of governmental red tape in dealing with wine.” Caddow further noted, “it is everywhere evident that the chaos in which the hastily revived wine industry found itself immediately following repeal has already been transformed to a large extent into a condition of order and understanding…. The entire wine industry is grateful to President Franklin D. Roosevelt … for the opportunities for advancement which have been afforded by the assistance of the Government.”Footnote 21 Two years later, Caddow maintained that FACA and the code of fair competition had saved the industry money and time. “The wine industry owes much of its advancement during the past year to this governmental cooperation,” he wrote.Footnote 22

The FACA, along with the rest of the National Recovery Administration, ended abruptly in May 1935 when the Supreme Court declared the program unconstitutional. The Roosevelt administration quickly set up a successor agency for the alcohol industry, the Federal Alcohol Administration (FAA), within the Treasury Department. Like its predecessor, the new agency required alcohol manufacturers to obtain permits and refrain from unfair trade practices. Starting in 1936, the FAA also regulated the wine industry’s labeling and, particularly, the names it used to describe its wines. Place names had value: wine from a recognized viticultural area fetched a higher price. As the Wine Institute’s Caddow noted, some winemakers disliked the new labeling requirements, which they found burdensome—that is, they found it inconvenient or less profitable to give a truer description of their wine’s place of origin. But the industry generally welcomed the government’s step toward creating “a permanent system of nomenclature and a permanent standardization as to identity and quality.”Footnote 23

Moreover, rather than impose these names on districts, the FAA solicited local growers’ assistance in drawing viticultural boundaries. Writing to John Colombero of the Etiwanda Grape Products company—makers of Fountain of Youth wines—an FAA official requested “a statement of your opinion of the boundaries of the ‘Cucamonga District,’ describing such boundaries by rivers, mountain ranges, railways, highways or other easily identified features of topography, or preferably, by submitting a map.” Colombero responded with a map, noting that “Cucamonga wine has established a very good name on the market and at present demands a premium.” The FAA officials were meanwhile, like the growers, much more relaxed about protecting the integrity of French wine names: the FAA expressly allowed Columbero to call his wines “burgundy” or “claret,” so long as “you will bring out the word ‘California’ in a more conspicuous color so as to be substantially as conspicuous and emphatic as the geographical wine names you have employed.” In defining American viticultural areas, while less conscientiously respecting French viticultural areas, the FAA sought to please California winemakers.Footnote 24

In much of the New Deal, implementation of novel programs to revitalize and modernize US industry fell to state governments, and the New Deal for wine was no exception. The state of California responded even more eagerly than Washington to the wine industry’s desire for more government regulation. The state department of public health worked with the Wine Institute to establish quality standards for wine made in the state and to prosecute violators of those standards.Footnote 25 Once again, the Wine Institute was thrilled with government intervention. “These regulations,” the institute declared, “will work no hardship on any bona-fide producer who has been making sound, wholesome California or American wines, but it will make it more uncomfortable for those who have been imposing on the public since repeal.”Footnote 26 Hugh Adams, the vice president and general sales manager of Fruit Industries, one of the largest wine producers, took partial credit for the new rules. “Our company,” he said, “has, by intensive educational campaign among the better class of national dealers, been able to prove definitely that the traffic of wines of good standard is the only sure method of conducting a profitable wine business.”Footnote 27 According to this wine manufacturer, the “better class of national leaders” fought for more government regulation, not less. The largest wineries particularly embraced regulation because, often, they helped write it. The Wine Institute’s counsel, Jefferson Peyser, boasted that the wine industry initiated nine out of 10 laws regulating its product.Footnote 28

In 1938, the Wine Institute won a two-year fight to make the California regulations, which they had helped author, into a nationwide code. California winemakers worried that out-of-state vintners marketed substandard, adulterated beverages as “California wine” and sought federal protection of their brand. New federal regulations of 1938 effectively required that any product sold as “California wine” in the United States would have to conform to the state’s rigorous public health standards.Footnote 29

The Wine Institute pressed for and welcomed these rules because they benefited its members. The institute lobbied on behalf of big growers and producers who wanted to create a stable, predictable, profitable market. They understood that government standardization of processes and ingredients could help them do it. Consequently, individual large-scale manufacturers echoed the Wine Institute’s praise for government regulation. J. B. Cella, the president of Roma Wine (which had become, as its advertisements said, “America’s Largest Winery”) told one official in 1939 that the entire industry knew that federal regulators “have been extremely cooperative with us in our steps forward and we appreciate that help.” Cella concluded that “it goes without saying” that the regulators “have been credited in the eyes of the industry.”Footnote 30

Some smaller-scale producers, many of them poorer, took a different view; they often could not afford to meet the new government requirements for better equipment and superior hygiene or hire experts to help them understand the system. John and Constanzo Chiesa of Gilroy, for example, applied in 1934 for a license to make wine from the grapes of their 40-acre vineyard, but they could not understand all the regulations because, they wrote, of their “not being able to read the English language intelligently.” Their winery closed in 1937.Footnote 31 Eligio Piccioni of Montecito, a former small-time bootlegger, applied for a permit to make wine legally from his 10-acre vineyard, but he did not have enough money to afford the federally mandated equipment.Footnote 32 “The winery and retail has [sic] been a continued loss to me,” he said in a letter asking regulators to help him terminate his permit. “Small producers cannot compete with the larger concerns.”Footnote 33

Still, not all immigrant winemakers working on a smaller scale found the system impossible to navigate. John Colombero, who would help define the Cucamonga district for the regulators, moved to the United States from Italy before the Great War, became a naturalized citizen in 1927, and applied to start a winery promptly upon repeal in 1933 on a hundred acres where he had been growing wine grapes through Prohibition for “the drug trade and sacramental purposes.” With borrowed money secured on the new crop and few assets save his Ford truck, he built his own fermenting tanks, telling regulators, “It was a case of have to.” He established a reputation as a rule-abiding vintner with the FAA and remained in business through the Second World War.Footnote 34

The rules and regulations the winemakers helped to write served important purposes in legitimizing their recently illicit product—they prevented fraud and illegal sales, as well as tax evasion, and they established the industry as one on which consumers could now rely. They also posed less of an impediment to larger producers, who could more readily afford compliance. By the end of the 1930s, the United States did not yet have a national market in wine—as indeed it still does not, well into the twenty-first century. But these steps toward regulation, largely taken at the behest of industry, contributed considerably to the increased consumption of California wine around the country.Footnote 35

Labor

The largest wineries and grape growers also benefited from New Deal labor policies, which helped contain the grievances of industrial workers while permitting vintners to break farmworker unions, sometimes with violence. As in the rest of the nation, New Deal labor law encouraged the unionization of factory and warehouse workers in the wine industry while excluding from its protection the grape pickers who most needed its assistance.

The National Industrial Recovery Act, and after 1935 the National Labor Relations Act (or Wagner Act), protected the rights of industrial workers to form unions, bargain collectively, and earn a minimum wage. These new federal protections for labor led to a surge of unionization and labor action throughout the country, including in 1934 a dockworkers’ strike in San Francisco that turned into a general strike.Footnote 36

Some workers in the wineries, defined as industrial workers and thus protected by these New Deal labor laws, organized successfully. In the northern San Joaquin Valley, many laborers at the biggest wine companies joined the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), which employers despised for leading the San Francisco general strike. The ILWU and its leader, the Australian immigrant (and Communist) Harry Bridges, terrified the wine growers. When other workers threatened to join Bridges’s union, employers suddenly began encouraging unionization—so long as it happened under the auspices of the more conservative American Federation of Labor instead of the ILWU or the Congress of Industrial Organizations, also active in the California fields at the time. The American Federation of Labor subsequently organized several local affiliates of the Distillery, Rectifying and Wine Workers International Union of America, which, after consolidating into one statewide local, negotiated contracts with the state’s biggest wineries. By 1952, the American Federation of Labor had succeeded in organizing workers at 30 of the 69 wineries in the San Joaquin Valley, whereas the ILWU represented workers at just one, Petri. Together the two unions organized all the largest wineries, which collectively produced more than 88% of the valley’s wine. Over the years, the unions won benefits and pay raises for their members.Footnote 37

Grape pickers also benefited from a New Deal program: the Farm Security Administration of the New Deal built 16 labor camps for migrant pickers in California, providing housing with flush toilets, showers, community centers, and health care. The camps dramatically improved the lives of the workers who could find places in them.Footnote 38 In The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck portrayed the Farm Security Administration camps as a sanctuary from the dehumanizing conditions of California fields. But the camps never received enough funding to house all who needed them.Footnote 39

Aside from the underfunded Farm Security Administration camps, though, the New Deal did little to improve the lives of farm workers. Many California agricultural workers wanted to think, early on, that the New Deal would protect their efforts at organization; one federal commission reported that pickers “have heard of the N.R.A., they believe that the Federal Government is going to protect them and improve their economic status, but they do not know that the N.R.A. does not apply to agricultural pursuits.”Footnote 40 Hoping to trigger federal intervention, more than a thousand grape pickers went on strike up and down the San Joaquin Valley in 1933—in Fresno, Visalia, and Lodi—where hundreds of vigilantes attacked strikers with sticks and clubs while law enforcement officers routed the workers with tear gas and fire hoses.Footnote 41 Neither federal nor state regulators intervened because the new labor laws did not protect the pickers’ right to organize. As with many other New Deal measures, including old-age pensions, unemployment insurance, and the minimum wage, farm workers found themselves excluded from the federal protections extended to industrial workers.Footnote 42

Market Stabilization

As the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 sought to revive the manufacturing economy by stabilizing prices and wages, the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933 and its successor legislation tried to solve similar problems for farm owners. Its best-known instrument was an agreement among commodity producers to reduce their production in return for federal subsidies. The AAA also provided for marketing agreements, signed by associations of farmers, to set prices and trade practices for farm produce. Although the original draft of the AAA offered these agreements only to “basic” commodities—wheat, cotton, corn, hogs, rice, tobacco, and dairy products—the California Farm Bureau Federation successfully lobbied to extend the program to other agricultural goods. Consequently, within the first year of AAA operation, the wine-grape variety known as Tokay joined other California produce as a crop governed by a AAA marketing agreement.Footnote 43

The wine industry also persuaded the California and US governments to use other programs beyond the AAA to help grape growers cooperate to raise prices. Once again, as with labor and regulatory policies, the New Deal benefited some growers at the expense of others.

Grape prices began to fall to unprofitable levels in the middle 1930s, as growers harvested bumper crops of raisin grapes. Though quality winemakers did not use raisin or table grapes like Thompson seedless in their products, the largest Central Valley vintners did, and the low prices for raisin grapes affected all grape growers, bringing down the price of wine as well. The state offered a solution.Footnote 44 The California Prorate Act of 1938 permitted growers of agricultural commodities to vote on whether to create a marketing plan for their product; if 65% agreed, then all growers had to abide by the plan. The state’s grape growers took advantage of the act immediately and voted to create a commission, which compelled all California grape growers to turn 45% of their crop into brandy. The goal was to keep grape produce in this easily stored form—casks of high-proof alcohol—until the price for grapes went up. In return for converting almost half their harvest, the grape growers received a state-mandated minimum price for the rest of their crop. The state established and enforced the program, and private banks and the federal Reconstruction Finance Corporation funded it. Large Central Valley grape growers benefited enormously from the program, but premium wine-grape growers—who did not suffer from a surplus—hated the prorate plan, which had them wasting their subtly flavored produce on brandy production. This conflict helped ensure that the program ended after just a single year.Footnote 45

Winery owners then turned to another state law, the Marketing Act, which permitted farmers, under the direction of the state Department of Agriculture, to tax themselves to fund advertising and marketing campaigns for their products.Footnote 46 Many winemakers, including some leaders in the Wine Institute, wanted to participate. But the law limited the program to producers of agricultural commodities—that is, although grapes might be covered, the finished product of wine would not. Jefferson Peyser, the Wine Institute’s counsel, successfully persuaded state officials that wine itself should be considered an agricultural product and that its producers were in fact “wine growers,” a term for which Peyser took credit despite ridicule from his peers. “You could have heard the laughter all the way to Los Angeles” from San Francisco, he said, when he first suggested it. Although the term long predated the New Deal, Peyser and his colleagues gave it regulatory and marketing force. The term “wine grower” allowed the industry to benefit from the Marketing Act and helped the owners of wine factories to sell an image of themselves as humble tillers of the soil.Footnote 47

As with the Prorate Act, some winery owners disliked the mandatory marketing tax and claimed that their business should not be covered by the Marketing Act. Disputing Peyser’s preferred terminology, they insisted that wine could not be grown. The Wine Institute responded by successfully lobbying the state legislature to amend state law to define wine henceforth as an agricultural product. Under the authority of the Marketing Act, which now clearly applied to “wine growers,” the director of the state agriculture department appointed a Wine Advisory Board, which used marketing taxes to hire the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency to devise its publicity campaign. And for publicity, the board hired the longtime champion of “wine growers,” the Wine Institute.Footnote 48

Spending and Lending

A variety of New Deal programs involved federal spending to employ Americans in the depths of the Depression on public works that improved the transportation and other infrastructure of the nation, and wine country benefited from these programs. Particularly, the construction and improvement of farm-to-market roads was a major part of New Deal public work, and these thoroughfares rendered the grape-growing and wine-making regions of California more accessible to their urban consumers. Major improvements included those made to US 99, then the “central arterial of the California State Highway System,” running the length of the Central Valley. New Deal modifications made it “safer, faster, and … shorter than the old road.” The state reported that the most improved highway led from Los Angeles into the Central Valley: “Prior to 1933, the motorist traveling from Castaic [in northwestern Los Angeles County] northerly to the floor of the San Joaquin Valley labored and fretted through 48 miles of narrow, tortuous mountain grades…. Today he travels only 38 miles between the same points, speedily and safely.”Footnote 49

Throughout the New Deal, the federal government promoted borrowing, or lent money itself, often specifically to benefit farm owners. As A. Setrakian, president of the California Growers Wineries, noted in a speech of 1938, “We California grape growers feel very appreciative and most grateful for what our President and our Congress have done for us…. Through different Federal lending agencies we were enabled to secure funds to take care of our farms properly.” The Farm Credit Administration of 1933 promoted the refinancing of agricultural properties otherwise under threat of foreclosure, and without such aid, Setrakian said, “I don’t know what would have become of our grape industry.”Footnote 50

Nor was federal assistance limited to emergency aid; the National Housing Act, as amended in 1935, created a class of loans that was insured by the Federal Housing Administration and usable for modernizing any property that was not a single-family dwelling, including “business or other commercial buildings” and “manufacturing or industrial plants.” This provision, one Federal Housing Administration official in California pointed out, “could not have been fashioned to fit more perfectly the particular problems of vineyardists contributing to California’s major output of fine wines.” The loans of up to $50,000 financed structural changes and also the purchase and installation of any permanently attached machinery and equipment—including the large storage and blending tanks that are essential to winemaking.Footnote 51 Whereas the Federal Housing Administration’s mortgage loans mainly supported home buyers in cities, the agency’s modernization loans were more evenly distributed throughout California, which reflected their appeal to rural borrowers like vintners who seized the opportunity to improve their establishments.Footnote 52

Tariffs

Although workers and employers might differ on the merits of government regulation of the workplace, they could agree on what they wanted from federal trade policies. Americans involved in the wine industry were unified in their conviction that the Roosevelt administration needed to shed its commitment to freer trade, at least so far as wine went.

Wine tariffs presented New Dealers with difficulties. The Democratic party had long preferred free trade, and Roosevelt did too. Moreover, after Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, Roosevelt wanted to establish closer commercial relations with France and Britain to serve as a bulwark against Nazism. As the president-elect told the French ambassador, Paul Claudel, in a meeting of February 1933, “the fate of Western civilization is at stake if there is not effective cooperation established in the near future between the United States, France, and Britain.” Claudel agreed, taking the opportunity of his conversations with Roosevelt to add that one of the best ways to ensure such cooperation would be to reverse the trend of the 1920s by lowering tariffs, expressing “the hope of seeing the American market largely open to our products and especially our wines. On this latter point M. Roosevelt agreed with me,” the ambassador wrote.Footnote 53 So Roosevelt had not only a general commitment to freer trade but also a specific concern to forge closer ties with France.

At the same time, although Roosevelt did tell Claudel that he would seek “favorable treatment” for French goods, it would be difficult to do so for anything “in competition with important American products.”Footnote 54 And California vintners wanted to make sure that Roosevelt put California wine on the list of those important American products. As one wrote to the president, “wine makers have suffered immensely during [Prohibition] and now they have the only opportunity of their lives to get a market which is rightfully theirs.” But they could not succeed if they had to compete with established foreign—especially French—wines. So, they asked the president to impose a ban, or at least a restrictive tariff, on imported wines.Footnote 55

He did: before Prohibition expired, using the power that remained to him until repeal, Roosevelt declared a temporary embargo on imported wines and liquors, saying that any such goods coming into the country would amount to defiance of the still-existing law.Footnote 56 After repeal caused that temporary embargo to expire, the administration set up a permitting system with quotas capping wine imports at 1.63 million gallons total, of which 784,000 gallons could come from France—pending a reciprocal trade agreement to ease trade. Roosevelt would use these restrictions to exact concessions from France, raising the quota slightly in later years. But he had established his willingness to use New Deal agencies to protect the California wine industry from overseas competition while it recovered from Prohibition.Footnote 57

In addition to the temporary embargo and quotas, the federal government levied a much higher tax on foreign table wines than on domestic wine, imposing a surcharge of $1.25 per gallon, as against 10 cents for US wine. Still, the administration’s harsh treatment of its ally France did not last. In 1936 it reduced the tariff on bottled French wine to 75 cents; no other nation received such a concession until 1941, when the import duties on Argentine wine were similarly reduced.Footnote 58 Like the rest of the New Deal, the Roosevelt program for wine became more internationalist over time.Footnote 59

Taxation

While successfully lobbying the president to increase taxes on imports, the wine industry also lobbied him to do what he could to reduce taxes on their own products. Vintners in the US acknowledged that much of the nation had only grudgingly accepted legalization of their product and would therefore insist on taxing it as a deterrent to its consumption. Industry advocates therefore sought to make the case that wine was more virtuous than distilled spirits and ought to be taxed less to encourage relative sobriety. Among the most prominent proponents of this argument was the administration’s chief alcohol regulator, Joseph H. Choate, Jr., the director of the Federal Alcohol Control Administration. After leaving his post in 1935, Choate used his new prominence to promote wine over other forms of intoxicating drink. “Wine drinkers seem almost everywhere to be temperate,” he explained. Lower taxes on wine would teach Americans to “sip rather than to guzzle,” Choate said, and would lead to decreased alcohol consumption overall.Footnote 60

Wine boosters also anticipated the Laffer curve by arguing that lower taxes on wine would lead to higher tax revenues. Taxes so severely inhibited sales, they argued, that reduced tax rates would more than make up in volume what they lost in each assessment.Footnote 61 Moreover, more wine drinking would stimulate the economy, creating more jobs for grape farmers and winery workers and leading to a stronger recovery from the Depression. Frank Buck, Napa Valley’s representative in the US Congress, wrote Roosevelt to argue, “increased consumption of wine over hard liquors is not only justified on the ground of temperance, but is a positive aid to the tens of thousands of grape growing farmers throughout the country.”Footnote 62 Choate went even further: if every American drank four glasses of wine per week, he predicted, “the country’s unemployment would be sharply reduced and the whole agricultural problem would be solved.”Footnote 63

Napa’s Congressman Buck, a Democrat elected to Congress in 1932, reflected the Golden State’s broader shift toward Roosevelt’s party that year. Clarence Lea, the Democrat who represented the neighboring district including Sonoma, complemented Buck as a promoter of the wine growers’ interests in the New Deal. But wine country did not need Democratic politicians to benefit from the New Deal. The grape growers of Fresno were represented in Congress by the staunch Republican conservative Bertrand Gearhart. The New Deal benefited wine regions irrespective of partisan tilt.Footnote 64

In domestic as in foreign taxation, the wine industry found a friend in Roosevelt who, as Buck noted, had long shown sympathy for the proponents of reduced wine taxation.Footnote 65 In 1936, with Roosevelt’s support, Congress cut wine taxes in half, from 10 cents to 5 cents a gallon for table wine and from 20 cents to 10 cents a gallon for fortified wine.Footnote 66 In contrast, the federal government levied $2 per taxable gallon of distilled spirits.Footnote 67

The state of California likewise heeded the requests of its wine lobbyists. At repeal, state taxes on wine ranged from California’s 2 cents per gallon to Florida’s punishing $1.75 per gallon.Footnote 68 California soon cut its already low rate in half, to a penny per gallon, contributing to record wine consumption in the state. Californians consumed an average of 3.3 gallons of wine per capita annually, more than six times the national average.Footnote 69

Image

Choate was not the only member of the Roosevelt administration who believed wine had intrinsic virtues that deserved promotion. New Dealers more generally took what opportunities they could find to offer positive opinions of the grape.

To distinguish wine from liquor or beer, promoters told just-so stories about wine’s traditionally sacramental and medicinal uses. Its very nature was more spiritual than spirituous, they said; it belonged at the family table rather than in the saloon, and its vitamins and other nonalcoholic contents promoted health. The Wine Institute’s trade publication Wines and Vines frequently ran articles claiming to prove, scientifically, the health-inducing qualities of wine, which allegedly provided nutrition and killed any bacteria lurking in your meal. And, of course, wine provided relaxation and good cheer, its boosters claimed. “A little wine will enable us to live longer and more useful lives,” wrote one viticulturist in Wines and Vines; “it will make us more pleasant to ourselves and to those with whom we come in contact.”Footnote 70

The administration reinforced this message. Undersecretary of Agriculture Rexford Tugwell, in a 1934 speech titled “Wine, Women, and the New Deal,” argued that wine fostered “contentment” as against “bathtub gin or three weeks’ whisky,” which promoted more aggressive moods. Rehearsing the virtues of Mediterranean civilizations and their long histories of winemaking, he predicted that the development of wine growing in the United States would “serve the broader purposes of the New Deal in making for a calmer and happier type of existence” as well as “help the American farmer find a better market for his produce.”Footnote 71

Tugwell and many of his colleagues took this notion seriously. They sought to restructure agrarian America along sustainable and modernized lines, creating throughout the farm belt new, model cities that would serve as small manufacturing hubs close to the rural producers that fed them raw materials. This idea gave rise to the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Resettlement Administration, which built new communities with affordable housing, schools, and small processing facilities and moved farm families into them. These developments were supposed to foster democratic self-government and economic independence. And often, as in Pine Mountain, Georgia—close to Roosevelt’s winter home in Warm Springs—they were to grow grapes for winemaking as part of this better rural life. New Dealers’ efforts to improve the countryside through viticulture met with substantial congressional opposition that thwarted their ambitions for broader, national application, much as their hopes to duplicate the Tennessee Valley Authority around the nation had done, but the contracts negotiated with producers to ferment the product of these model towns attests to the sincerity of the New Dealers’ belief that wine growing should be integrated into the rural good life.Footnote 72

Nor was Tugwell the sole White House adviser to promote drinking wine. Eleanor Roosevelt, though a nondrinker herself, added wine to the menu for White House dinners for the first time since 1920, announcing in a statement, “There will be no fixed rule as to the serving of wine, but when served there will be, of course, simple wines, preference being given to American wines.”Footnote 73 The first lady’s efforts made her a heroic figure to domestic wine producers. “My next vote goes to Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt as Commander-in-Chief,” joked one vintner in a letter to the president.Footnote 74

State

The federal government played by far the larger role in helping the wine industry recover from Prohibition and Depression, but the California state government contributed substantially, often working closely with Washington. As noted already, the state oversaw the grape prorate plan of 1938, organized the marketing agreement for the wine industry, and led the nation in implementing high standards for hygienic wine production. But the state’s more important contribution was a long-term commitment. By funding the viticulturists and enologists at the University of California, the state government subsidized wine and grape research and ensured the wine industry’s attainment of world-class status in the 1970s.

The University of California began studying grape varieties and winemaking in 1880 through its Fruit Products laboratory at its original campus in Berkeley. After repeal, the research on wine and grapes moved 60 miles up the highway to the university farm in Davis, later to become the University of California, Davis.

The state’s winemakers revered the work of the university scientists who conducted experiments that might not produce results for years. As the Wine Institute explained, the state university provided a perfect venue for addressing issues “that require fundamental research work which is too complicated or too general in nature for the industrial control or research laboratories.”Footnote 75

One such problem was how best to grow wine grapes in the vast vineyards of the state’s inland valleys. A UC Davis geneticist, Harold Olmo, devoted his career to developing some two dozen new hybrid grape varieties that could both handle the heat of the Central Valley and produce decent table wines. This research took too long—roughly 15 years, start to finish, for each new variety—for a winery to do itself.Footnote 76

As Olmo hand-pollinated and hybridized new grapes for the large producers of central California, two UC Davis enologists, Maynard Amerine and Albert Winkler, conducted extensive research on grape farming and winemaking. Their small-batch wines helped them understand which grapes grew best in different regions of the state. During the 1930s, they distributed their research to the state’s winemakers by publishing their conclusions in wine journals, saying which varieties to plant where, when to harvest them, and how to make the best wine from them. In 1944, Amerine and Winkler compiled their research into a book that became the basic text for California winemakers.Footnote 77

In a characteristically effusive story about the enologists at Davis, Wines and Vines crowed that the University Farm laboratory in 1938 contained “sixteen hundred wine types!” The figure was “not a typographical error,” the magazine added; Amerine and Winkler’s enological experiments made UC Davis the “most remarkable winery in the world today.” Though the university’s research could “well win for California the position of a foremost wine-producing region in the world,” it would require the state’s wine growers to take advantage of the knowledge the researchers had produced.Footnote 78

Eventually they did: the influence of Olmo, Amerine, and Winkler is visible in data compiled by federal and state agencies to aid the wine growers. The New Deal’s Agricultural Adjustment Administration, together with the Works Progress Administration and the California department of agriculture, collected data on acres planted to particular crops. By the 1960s, the Olmo varieties that had initially been planted on only a few experimental acres had become an essential part of the state’s wine produce, as had older varieties of reds and whites—including the chardonnay and cabernet sauvignon that became the basis for Napa Valley’s prize-winning wines in the 1970s—given a renaissance by the work of Amerine and Winkler.Footnote 79

Among the greatest enthusiasts of state-funded research at UC Davis were—in terms of the scale and profits of the business—some of the most successful winemakers in history. Ernest Gallo who, with his brother Julio, founded and led Gallo Wine, which became the world’s largest wine producer by the 1960s, told in his memoir how a series of pamphlets published by UC enologists provided the information necessary for his first foray into legal winemaking after repeal. “They were exactly what we needed,” he wrote of the government pamphlets. “This was the beginning of our knowledge about making commercial wine, such as how to have a sound, clean fermentation, and how to clarify the wine. These old pamphlets probably saved us from going out of business our very first year.”Footnote 80 The Gallos continued to express gratitude to the UC winemakers throughout their long career; their only concern was that the university might be too generous in imparting its research to vintners outside the United States: “I think Davis is sometimes too quick to share technology developed with money supplied by the taxpayers of California,” Ernest Gallo wrote. “Our taxpayers helped make [winemakers in other nations] stronger competitors to U.S. wines.”Footnote 81

Gallo’s nationalist complaint reflects the invaluable role of the state in the broader wine industry’s recovery from Prohibition and Depression. The consumption figures show a rapid increase in the quantity of wine consumed compared with the pre-Prohibition years and a shift back to more quality wines. As the New Deal for wine, like the New Deal in general, became more internationalist, it helped create a global market. California winemakers’ success in recovering from Prohibition and assuming the status of global prize-winning wines owed much to the intervention and assistance of the US government during the Roosevelt administration.

The state’s role in helping the wine industry after repeal has implications for the historiography of the New Deal as well as for present-day policy making. First, scholars often underrate the contribution of New Deal programs to the nation’s economic recovery; the case of wine supports the observation that the national recovery was steady and rapid, with the exception of the 1937–38 recession.Footnote 82 Second, the repeal of Prohibition played a critical role in this story of success. The rebirth of the alcohol industry created jobs and markets that stimulated the national economy. Finally, this history gives us a window into the successes as well as the pitfalls of state promotion of economic recovery and development. The New Deal state helped the wine industry to recover, but sometimes at the expense of the most marginalized workers and businessmen, even as it held out an ideal of the good and prosperous life that would include them.

By building roads, lending money, regulating quality, promoting image, protecting industrial workers’ rights and income, managing foreign competition, and reducing taxes on domestic products, the national New Deal worked with the state land grant university and the California state government to nurture the reborn US wine industry and to help it recover from Prohibition. Federal and state assistance made possible California wines’ progression from banned substances to world-class, prize-winning chardonnays and cabernets in just a few decades.