Introduction

Ptychitid ammonoids appear at the lower-middle Anisian boundary with Malletoptychites, as well constrained only in the Tethys Himalaya (Krystyn et al., Reference Krystyn, Balini and Nicora2004), and are a typical component of the open-marine ammonoid assemblages during Anisian and partially Ladinian times (Balini, Reference Balini1998). The family fills the gap after a minor ammonoid extinction event when almost all grambergiids disappeared (Konstantinov, Reference Konstantinov2008). The type genus itself, Ptychites, is one of the most characteristic ammonoids in the fossil record that was erected by Mojsisovics in Neumayr (Reference Neumayr1875), based on material from the Tethys Realm. Only a limited number of species was known in the early years after erecting the genus, but Mojsisovics’ (Reference Mojsisovics1882) monograph boosted its importance. This work is regarded as a milestone in the history of Triassic ammonoids and chronostratigraphy (e.g., Tozer, Reference Tozer1971, Reference Tozer1984; Balini et al., Reference Balini, Lucas, Jenks and Spielmann2010; Lucas, Reference Lucas2010; Jenks et al., Reference Jenks, Monnet, Balini, Brayard, Meier, Klug, Korn, De Baets, Kruta and Mapes2015). Mojsisovics enlarged the number of species of Ptychites, and advanced the organization of this genus in several groups. After the group featured prominently in Mojsisovics (Reference Mojsisovics1882), it became one of the guide fossils for Triassic correlations. Its iconic status was also reflected by being a part of Ernst Haeckel's ammonoid selection in his influential book “Kunstformen der Natur”—a trendsetting issue, connecting science and art more than a century ago (Haeckel, Reference Haeckel1899, Reference Haeckel1900). In fact, Ptychites has been described from almost all over the world: (1) Nevada (Smith, Reference Smith1914; Monnet and Bucher, Reference Monnet and Bucher2005); (2) British Columbia (McLearn, Reference McLearn1948; Tozer, Reference Tozer1994); (3) Spitsbergen (Lindström, Reference Lindström1865; Mojsisovics, Reference Mojsisovics1886; Köhler-Lopez and Lehmann, Reference Köhler-Lopez and Lehmann1984); (4) the Himalayas (Diener, Reference Diener1895a, Reference Diener1907, Reference Diener1913; Waterhouse, Reference Waterhouse1994, Reference Waterhouse1999, Reference Waterhouse2002a; Krystyn et al., Reference Krystyn, Balini and Nicora2004); (5) the Northern Alps (Hallstatt area, Schreyeralm Limestone, condensed Ammonitico-Rosso facies; Mojsisovics, Reference Mojsisovics1882; Diener, Reference Diener1900); (6) the Balaton Highlands (Vörös, Reference Vörös2018), and (7) the Dinarids and Hellenids (Han Bulog Limestone; von Hauer, Reference Hauer and von1892; Renz, Reference Renz1910; Salopek, Reference Salopek1911; Pomoni and Tselepidis, Reference Pomoni and Tselepidis2013). In the Triassic of Spitsbergen and the Western Tethys, namely the wider Alpine and the Himalayan regions, the genus Ptychites is especially characteristic (e.g., Mojsisovics, Reference Mojsisovics1886; Weitschat and Lehmann, Reference Weitschat and Lehmann1983; Harland and Geddes, Reference Harland, Geddes and Harland1997; Balini, Reference Balini1998). Therefore, scientists introduced the terms “Ptychitenkalke” (Ptychites limestone; Mojsisovics, Reference Mojsisovics1882, Reference Mojsisovics1886; Gugenberger, Reference Gugenberger1927; Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg1952) and “Ptychites beds” (Spath, Reference Spath1921; Harland and Geddes, Reference Harland, Geddes and Harland1997). Ptychites were well adapted to quite a large number of different paleoenvironments (Balini, Reference Balini1998). Despite this fact, the genus shows a low morphological disparity. The new species described herein does not challenge this picture.

In this paper, we describe a new species of Ptychites and discuss the taxonomic diversity and morphologic disparity of this genus during the Middle Triassic of the west coast of North America. Our study area in north-western Nevada, USA, belongs to the world's most complete low-paleolatitude sequences, revealing late Anisian ammonoid faunas (Monnet and Bucher, Reference Monnet and Bucher2005). The continuous sequences, which include a very diverse and abundant ammonoid fauna, provide a good basis for ontogenetic studies on a high-resolution scale. Due to their distinctive ontogenetic trajectories (model curves), ptychitids will act as an important cornerstone in future quantification of ontogenetic analyses.

Because Ptychites is found all over the world, this study also contributes to the worldwide correlation of Middle Triassic sediments. Representatives of this group were described from many different localities all over the world. However, most of these records originate from condensed facies, with significant uncertainty regarding the number and age of the faunas, and the composition of the populations. This makes correlative work particularly challenging. The problems of correlation and condensation are discussed by Tozer (Reference Tozer1971) and are, for example, reported from Epidauros (Greece) by Krystyn and Mariolakos (Reference Krystyn and Mariolakos1975) and Krystyn (Reference Krystyn1983). Furthermore, Balini (Reference Balini1998, p. 144) emphasized that the alpha taxonomy of Ptychites is characterized by a lack of information on the stratigraphic relationships between the type specimens. The study of ptychitid ammonoids therefore holds great potential for both biostratigraphic and paleobiological work.

Geological setting and material

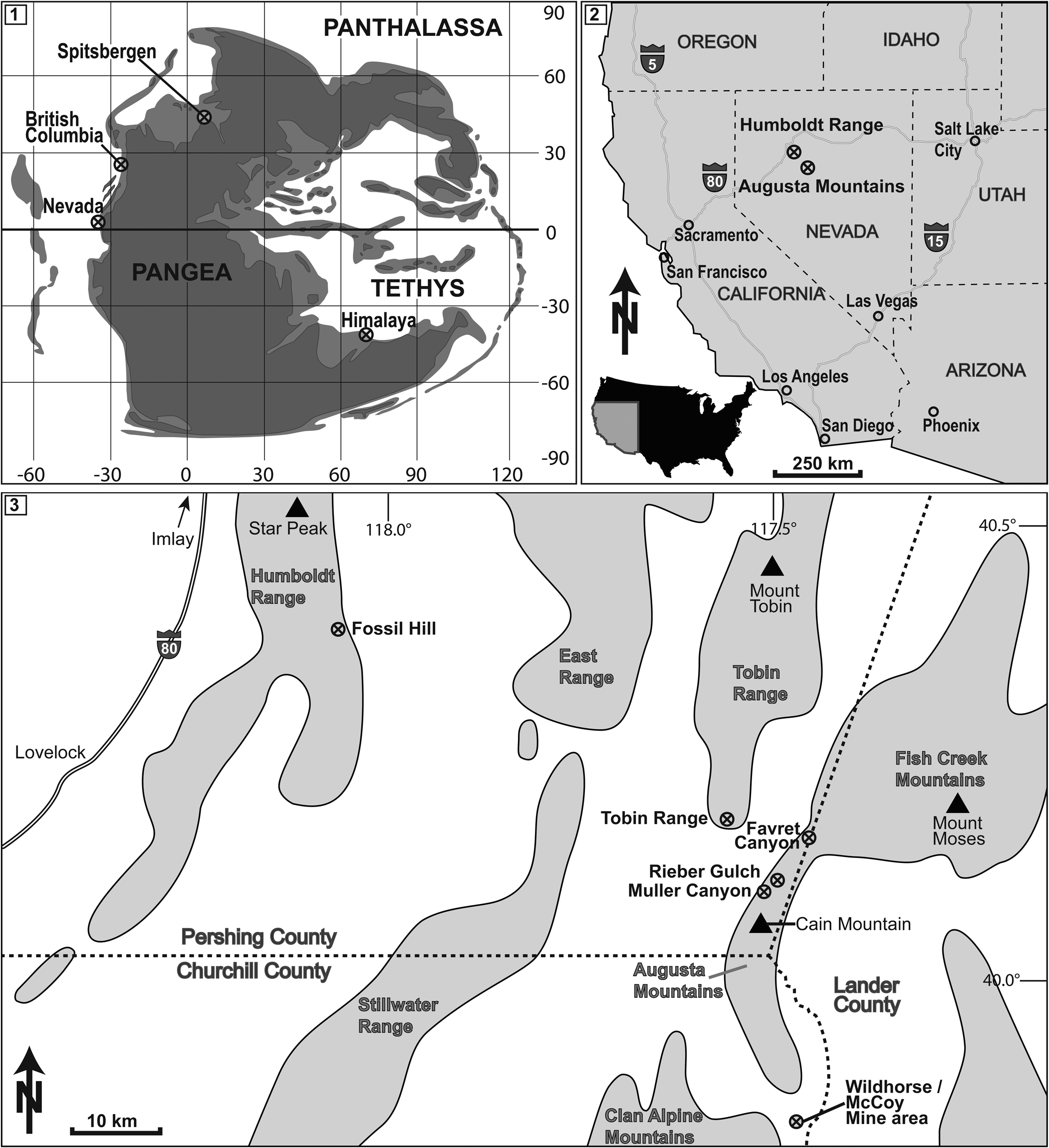

The bulk of the fossil material used here was collected by members of the Geosciences Collection of the University of Bremen (Germany). It derives from the Muller and Favret Canyon of the Augusta Mountains (Pershing County), north-western Nevada, USA (see Fig. 1). A complete section of the upper portion of the late Anisian Fossil Hill Member of the Favret Formation and the lowermost part of the early Ladinian Home Station Member of the Augusta Mountain Formation was meticulously documented and measured. Furthermore, J. Jenks collected additional material in Rieber Gulch and Favret Canyon of the Augusta Mountains, Pershing County, and the Wildhorse-McCoy Mine area, Churchill County (see also Fig. 1). Since the fossil material of J. Jenks was loosely collected, no measured sections are associated with this material. However, the sites where the fossil material was found are thoroughly documented and the biostratigraphic framework is well known (Jenks et al., Reference Jenks, Monnet, Balini, Brayard, Meier, Klug, Korn, De Baets, Kruta and Mapes2015).

Figure 1. (1) Middle Triassic paleogeographical setting. Nevada as well as other important localities of Ptychites spp. are marked. Redrawn from Péron et al. (Reference Péron, Bourquin, Fluteau and Guillocheau2005), Brayard et al. (Reference Brayard, Bucher, Escarguel, Fluteau, Bourquin and Galfetti2006), and Skrzycki et al. (Reference Skrzycki, Niedźwiedzki and Tałanda2018). (2, 3) Location of the study area in NW Nevada, USA. The most important localities of Fossil Hill Member outcrops are marked.

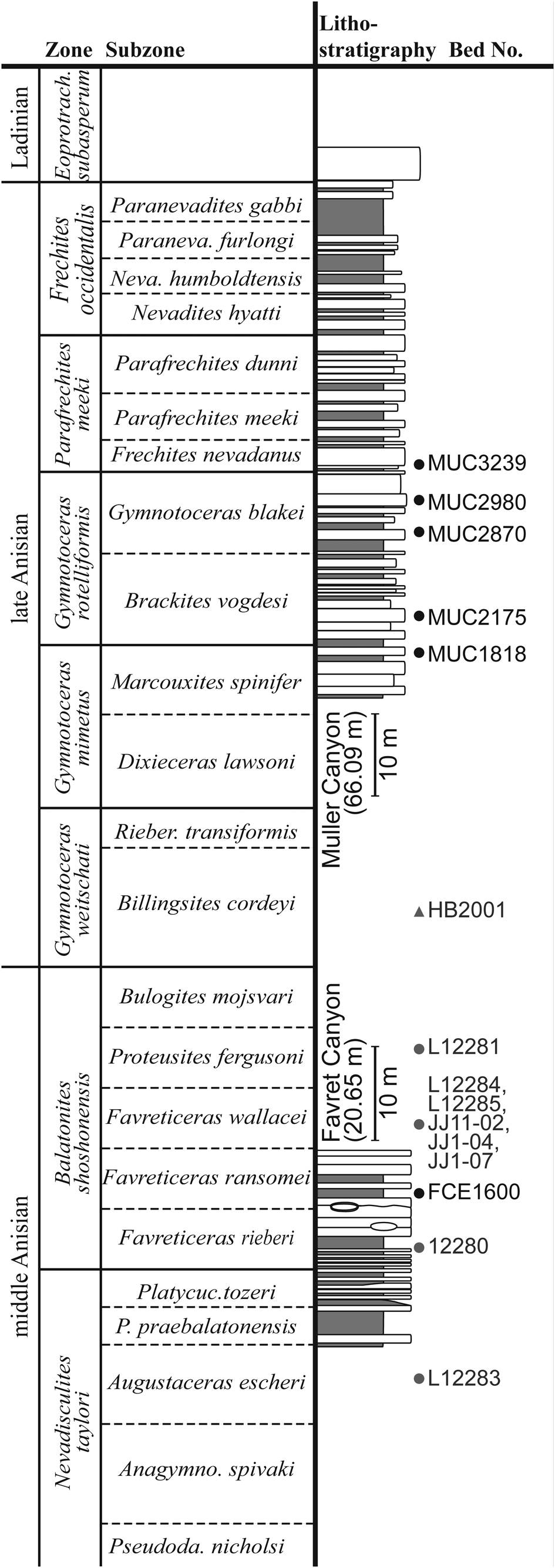

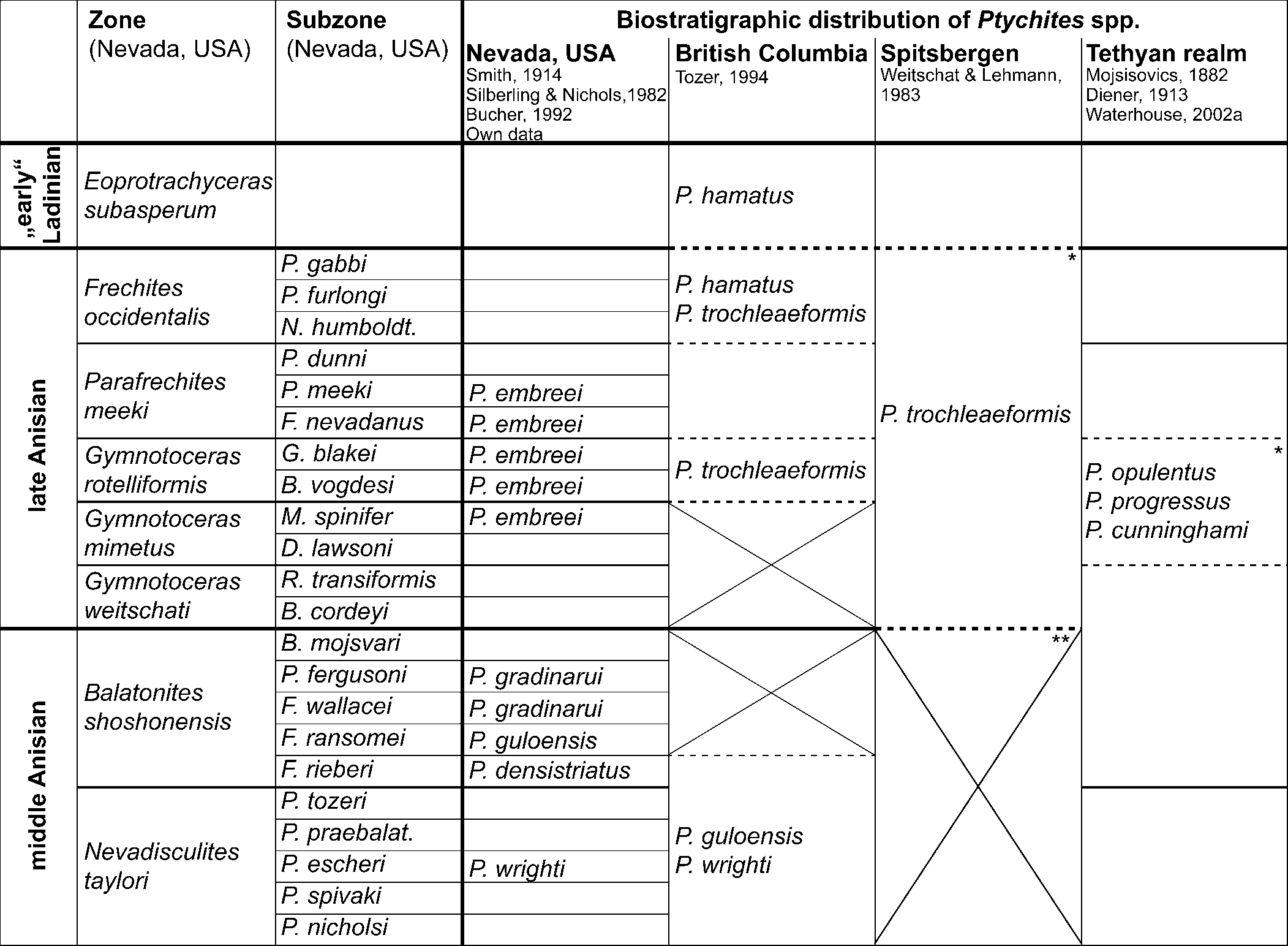

Biostratigraphically, Ptychites spp. from Nevada that are the focus of this study were collected in the Balatonites shoshonensis and the Gymnotoceras mimetus–Gymnotoceras rotelliformis zones of the Fossil Hill Member (middle and late Anisian; see Fig. 2). The Fossil Hill Member consists of alternating layers of calcareous siltstone and mudstone with lenticular limestone. The rich fauna of the succession primarily consists of halobiid bivalves and ammonoids. Ceratitids are quite abundant and diverse throughout the member. The Anisian faunas of the Humboldt Range were previously described in the 19th and early 20th century (Gabb, Reference Gabb1864; Hyatt and Smith, Reference Hyatt and Smith1905; Smith, Reference Smith1914). Recently, Silberling and Nichols (Reference Silberling and Nichols1982) and Monnet and Bucher (Reference Monnet and Bucher2005) refined the original alpha taxonomy and the biostratigraphy.

Figure 2. Measured lithostratigraphic sections in the Muller and Favret canyons of the Augusta Mountains, Pershing County, NW Nevada, USA from where our specimens were collected. Black dots: Beds within our measured sections; Gray dots: JJ-localities documented by J. Jenks, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA; Gray triangle: HB-locality, documented by H. Bucher, Zurich, Switzerland (Monnet and Bucher, Reference Monnet and Bucher2005).

Methods and conventions

In order to underpin the description of Ptychites embreei new species, we performed an ontogenetic analysis of selected specimens of Ptychites. The methods introduced by Korn (Reference Korn2010) and Klug et al. (Reference Klug, Korn, Landman, Tanabe, De Baets, Naglik, Klug, Korn, De Baets, Kruta and Mapes2015) were used. All samples used for ontogenetic analysis were first removed from the rock matrix by mechanical preparation and were then measured along the longest axis. The conch dimensions of the growth stages were obtained from digitized sketches of high-precision cross-sections intersecting the protoconch. In order to find a non-destructive method, a CT scan of selected specimens with a GE Phoenix v device, tome, x s 240 with a nanoray tube NF 180 kV was performed at the University of Erlangen, Germany. Unfortunately, the differences in density were marginal, and therefore the contrast of the internal structures on the scan images were not sufficient for further analysis.

The basic conch parameters (dm: diameter; ww: whorl width; wh: whorl height) for all available specimens were measured at every distinct growth stage (i.e., half whorl), starting at the protoconch. For the ontogenetic analysis, the growth parameters whorl expansion rate (WERn = [dmn/dmn-0.5]2), whorl width index (WWIn = wwn/whn), umbilical width index (UWIn = uwn/dmn), and the conch width index (CWIn = wwn/dmn) were calculated (for further explanations see Korn, Reference Korn2010; Klug et al., Reference Klug, Korn, Landman, Tanabe, De Baets, Naglik, Klug, Korn, De Baets, Kruta and Mapes2015).

Ontogenetic morphospace

The growth parameters WER, UWI, and CWI were also analyzed in a principal component analysis (PCA). The dataset comprises the values for all distinct growth stages of an individual. In contrast to most other ontogenetic studies using ternary plots or multivariate statistics (e.g., Korn and Klug, Reference Korn, Klug, Landman, Davis and Mapes2007; Klug et al., Reference Klug, De Baets and Korn2016; Walton and Korn, Reference Walton and Korn2017, Reference Walton and Korn2018), herein every individual is defined by the sum of all parameters of all ontogenetic stages. In order to omit missing values in the analysis, the PCA data set was limited to the last growth stage of the specimen with the fewest number of half whorls (here growth stage number 5.0; see Appendix). All parameters are numbered consecutively, starting with the first half whorl (i.e., WER0.5, CWI0.5, UWI1.0) to the last one of the analysis (i.e., WER5.0, CWI5.0, UWI5.0). Therefore, the space opened up by this analysis is not a classical morphospace showing the morphology of an individual at a specific growth stage, but in an artificial state of combined morphologies of different ontogenetic stages. It illustrates how the ontogeny of the groups differ. To prevent confusion, we introduce the term “ontogenetic morphospace.” The PCA with correlation matrix was run using PAST (version 3.25; Hammer et al., Reference Hammer, Harper and Ryan2001).

Suture lines

The preservation of the ammonoids occasionally permits the drawing of suture lines. Among the fossil material herein, GSUB C13194 (P. guloensis Tozer, Reference Tozer1994) and C13196 (P. gradinarui Bucher, Reference Bucher1992) were the only specimens with a nicely preserved suture line. We used the suture terminology of Wedekind (Reference Wedekind1916), as applied by Kullmann and Wiedmann (Reference Kullmann and Wiedmann1970) and modified by Korn et al. (Reference Korn, Ebbighausen, Bockwinkel and Klug2003)—E: external lobe; A: adventive lobe (that corresponds to letter L of the traditional nomenclature); U: umbilical lobe; I: internal lobe; E/A (that is E/L of traditional nomenclature) is the saddle between E and A; A/U (that is L/U of traditional nomenclature) corresponds to the saddle between A and U.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Geosciences Collection of the University of Bremen (GSUB), Germany; Paleontological Institute and Museum University of Zurich (PIMUZ), Switzerland; New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science (NMMNH), Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA. The abbreviation JJ refers to localities of J. Jenks, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA, and HB refers to localities of H. Bucher, Zurich, Switzerland.

In the synonymy list we used ‘[n.s.]’ for publications we have not seen, because we could not get hold of a copy of that paper.

Systematic paleontology

Order Ceratitida Hyatt, Reference Hyatt1884

Superfamily Ptychitoidea Mojsisovics, Reference Mojsisovics1882

Family Ptychitidae Mojsisovics, Reference Mojsisovics1882

Genus Ptychites Mojsisovics in Neumayr, Reference Neumayr1875

Type species

Ammonites rugifer Oppel, Reference Oppel1863 (designated by Tozer, Reference Tozer1994, see discussion on p. 133). Tozer (Reference Tozer, House and Senior1981, p. 94) was used as reference for the family-group taxonomy.

Ptychites guloensis Tozer, Reference Tozer1994

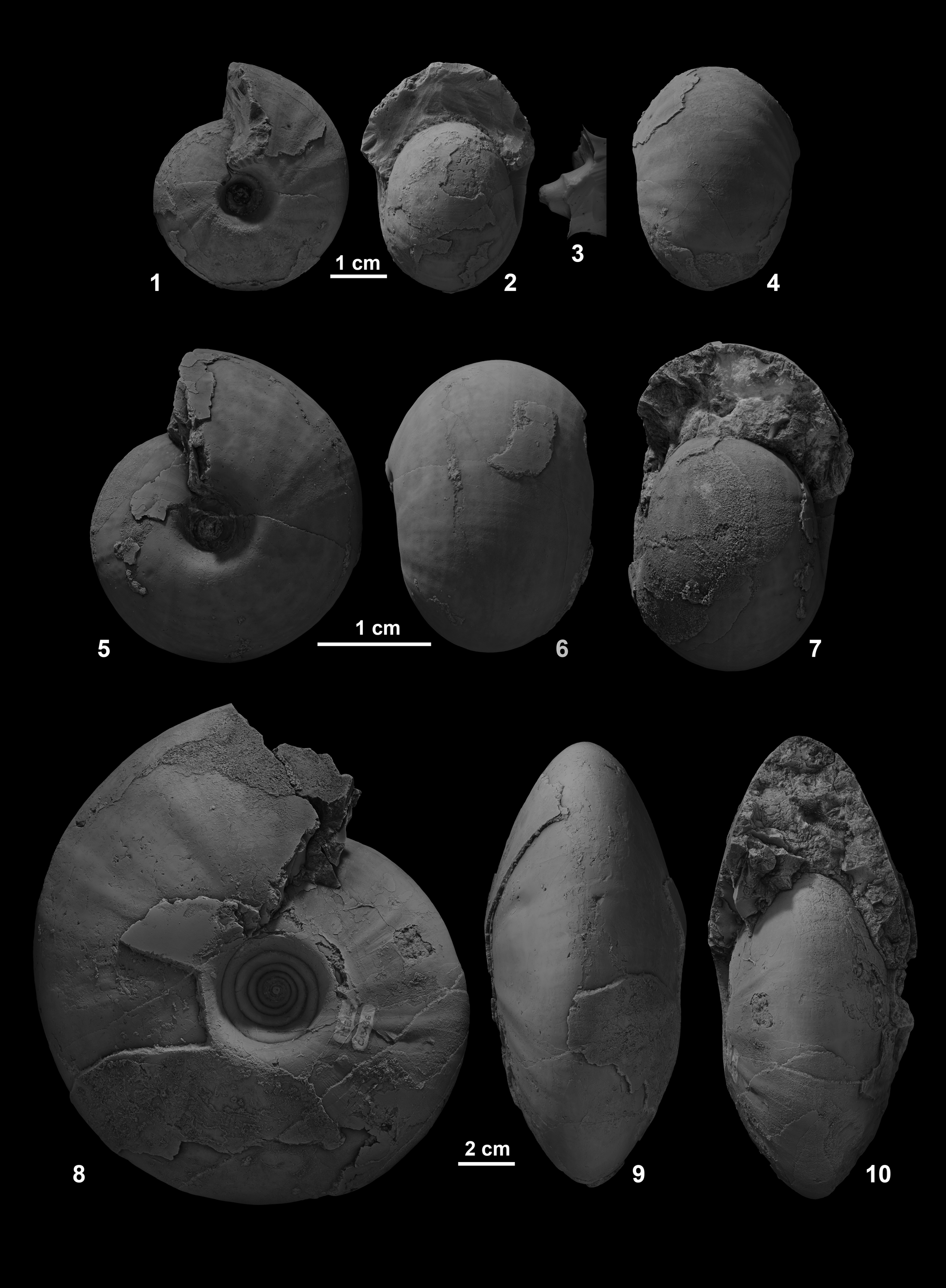

Figures 3.5–3.7, 4

- Reference Tozer1994

Ptychites guloensis; Tozer, p. 133, pl. 48, figs. 1, 2, text-figs. 35d, e.

Holotype

Holotype is GSC 70993 from the Sulphur Mountain Formation, Minor Zone, near south end of Hook Lake, NTS Kinuseo Falls (GSC loc. 83873), Canada; several paratypes from other localities in the same area.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Ptychites guloensis by Tozer (Reference Tozer1994, p. 133) is as follows: “Ptychites attaining a diameter of at least 70 mm; H about 50 per cent, W 60–70 per cent, U about 15 per cent of diameter. Whorl section ovoid, the flanks and venter merging to form a perfect arch. Distinct ribbing absent, growth striae nearly or perfectly radial. Suture line with four lateral saddles, the outer two large and the inner two small. The inner two are depressed in relation to the large saddles. The outer large saddles are not bifid; the inner small saddles weakly bifid. Moderately sized to large Ptychites with a perfectly rounded venter. Rather narrow umbilicus with a steep umbilical wall. Almost smooth conch with only fine growth striae.”

Occurrence

Favret Canyon, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County: GSUB loc. FCE, F. ransomei Subzone, B. shoshonensis Zone, Fossil Hill Member of the Augusta Mountain Formation. According to Tozer (Reference Tozer1994, p. 133), P. guloensis also occurs in the Middle Anisian, Middle Triassic, H. minor Zone, Toad Formation of north-eastern British Columbia.

Description

Measurements of the selected specimen are provided in Table 1. Specimen GSUB C13194 (Fig. 3.5–3.7) is a complete conch with a maximum diameter of 26.71 mm. The pachyconic conch (ww/dm = 0.69) is subinvolute (uw/dm = 0.22) and has a perfectly rounded venter. The narrow umbilicus is deeply incised revealing a steep umbilical wall. The umbilical shoulders merge into the venter in a wide arch. The largest part of the shell is not preserved. The remnants of the shell and some imprints on the steinkern however reveal that the shell was smooth, bearing some fine growth striae.

Figure 3. (1–4) Ptychites wrighti, from north side of Favret Canyon, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County; (3) cast of deeply incised and funnel-shaped umbilicus, NMMNH 80882. (5–7) Ptychites guloensis, Favret Canyon, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County, GSUB C13194. (8–10) Ptychites gradinarui, Favret Canyon, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County, GSUB C13196.

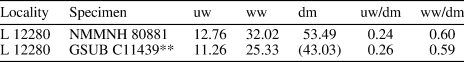

Table 1. Measurements in mm of one specimen of Ptychites guloensis Tozer, Reference Tozer1994 collected in the Fossil Hill Member of the Favret Formation at the Muller Canyon locality in the Augusta Mountains, Pershing County, Nevada, USA. For further details on the bed number, see Figure 2 (“Bed No.”). uw: maximum umbilical width; ww: maximum whorl width; dm: maximum diameter of shell.

The major elements of the suture line of specimen GSUB C13194 (Fig. 4.1) are uniformly large, namely with an U3/U2, U2, A/U2, and an A that are of a similar extent. The A lobe is bifid, with the endings slightly less incised compared to the other major sutural elements. The U2/A tapers towards the aperture. The E/A is slender and less strongly denticulate. The U1/U4 shows a prominent, slender spur. The suture line of GSUB C13194 shows only minor differences to the sutures redrawn from Tozer (Reference Tozer1994) (Fig. 4.2). The latter differs by a trifid A lobe that is slightly smaller, a U2/A that is not tapering, and the U1/U4 that lacks a spur.

Figure 4. Suture line of Ptychites guloensis, (1) GSUB C13194 compared to (2) Tozer (Reference Tozer1994, p. 444, fig. 35e). Bracketed letters indicate traditional suture nomenclature.

Materials

One specimen (GSUB C13196).

Remarks

Köhler-Lopez and Lehmann (Reference Köhler-Lopez and Lehmann1984) illustrated the ontogenetic development of the suture line of Aristoptychites, and thus demonstrated that the traditional nomenclature should be modified in Ptychitidae. In this respect, Tozer (Reference Tozer1994, p. 133) refers to “four lateral saddles,” these are the U2/A, U3/U2, U4/U3, and U1/U4 of the ontogenetic nomenclature used herein. The diagnosis of the suture line of P. guloensis given by Tozer (Reference Tozer1994, p. 133) is as follows: “[…] with four lateral saddles, the outer two large and the inner two small. The inner two are depressed in relation to the large saddles. The outer large saddles are not bifid; the inner small saddles weakly bifid.” However, this does not characterize the species because the features can be found in other species of Ptychites as well. Nevertheless, the Canadian specimen shows typical features of Ptychites, such as the rather broad and rounded outline of the U3/U2 and U2/A and the multi point indentations of the lobes. Although we consider the preservation of GSUB C13194 as good, we cannot rule out that the slightly more slender and irregular indentations of the U3/U2 and U2/A and the different shape of the lowermost tip of the A lobe with fairly broad and simple indentations are a matter of preservation.

Ptychites wrighti McLearn, Reference McLearn1946

Figure 3.1–3.4

- Reference McLearn1946

Ptychites wrighti; McLearn, p. 3, pl. 4, fig. 5 [n. s.].

- Reference McLearn1948

Ptychites wrighti; McLearn, p. 12, pl. 4, fig. 5.

- Reference McLearn1969

Ptychites wrighti; McLearn, p. 56, text-fig. 31, pl. 10, fig. 1a–c.

- Reference Tozer1994

Ptychites wrighti; Tozer, p. 134, pl. 48, figs. 3, 4.

Holotype

According to McLearn (Reference McLearn1969), the holotype (GSC 6442) is from the Toad Formation, far up “McTaggart Creek,” west slope of Mount Wooliever, Sikanni Chief River valley (GSC loc. 10731), Canada.

Diagnosis

Small to moderately sized species of Ptychites with a rounded to subtriangular venter and a rather narrow umbilicus with an abrupt umbilical shoulder. The conch bears very weak folds and ribs.

Occurrence

North side of Favret Canyon, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County: NMMNH loc. L 12283, A. escheri Subzone, N. taylori Zone. According to Tozer (Reference Tozer1994), P. wrighti also occurs in the middle Anisian, Middle Triassic, H. minor Zone?, Toad Formation of north-eastern British Columbia.

Description

Measurements of the selected specimen are provided in Table 2. Specimen NMMNH 80882 (Fig. 3.1–3.4) is a complete conch with a maximum diameter of 38.74 mm. The pachyconic shell (ww/dm = 0.74) is subinvolute (uw/dm = 0.26) revealing a deeply incised umbilicus (Fig. 3.3) and an abrupt umbilical shoulder. Rounded to subtriangular shoulder. The flanks are covered with very weak, irregular and slightly rursiradiate ribs and folds. The length of the body chamber exceeds one whorl.

Table 2. Measurements in mm of one specimen of Ptychites wrighti McLearn, Reference McLearn1946 collected by J. Jenks in the Fossil Hill Member of the Favret Formation, Pershing County, Nevada, USA. For further details on the bed number, see Figure 2 (“Bed No.”). uw: maximum umbilical width; ww: maximum whorl width; dm: maximum diameter of shell.

Materials

One specimen (NMMNH 80882).

Remarks

The diagnosis for this species is newly established here, due to a lack of a former diagnosis. The occurrence of this species seems to be restricted to the open water fauna of the Panthalassic Ocean. The available material does not allow an ontogenetic analysis. The suture line published in McLearn (Reference McLearn1969) shows that the sutural elements of this species are comparatively strongly denticulate with deep incisions and a rather weak frilling.

Ptychites gradinarui Bucher, Reference Bucher1992

Figures 3.8–3.10, 5, 6.1–6.11, 7, 8

- Reference Silberling and Tozer1968

Ptychites cf. P. domatus (Hauer); Silberling and Tozer, p. 37.

- Reference Bucher1992

Ptychites gradinarui; Bucher, p. 439, pl. 9, figs. 11, 12, pl. 10, figs. 1–4, pl. 11, figs. 21–26, text-fig. 22.

- Reference Jenks, Spielmann, Lucas, Lucas and Spielmann2007

Ptychites gradinarui; Jenks et al., p. 36, pl. 18, figs. a, b.

Holotype

The holotype USNM 448264, the paratypes USNM 448262, USNM 448265–448267, and the plesiotype USNM 448263 are all stored in the collection of the National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C, USA (Bucher, Reference Bucher1992).

Diagnosis

Rather large species of Ptychites reaching a diameter of 90 mm and in rare cases more than 250 mm (see Bucher, Reference Bucher1992, p. 440). The conch of juvenile specimens is mostly pachyconic. The later ontogenetic stages, however, show two different morphotypes: pachyconic-subevolute (ww/dm ~0.70; uw/dm ~0.40) and discoidal-subinvolute (ww/dm ~0.50; uw/dm ~0.30). Furthermore, the conch bears a smooth ornament of irregular, rectiradiate to slightly falcoid ribs and growth striae. The internal mold of juvenile specimens shows growth constriction.

Occurrence

Wildhorse-McCoy Mine area, Churchill County: NMMNH locs. L 12281 (P. fergusoni Subzone), 12285 and J. Jenks loc. JJ1-04, JJ1-07 (F. wallacei Subzone) of the B. shoshonensis Zone. Rieber Gulch, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County: NMMNH loc. L 12284 and JJ11-02, F. wallacei Subzone, B. shoshonensis Zone. Favret Canyon, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County: GSUB loc. FCE1600, F. ransomei Subzone, B. shoshonensis Zone.

Description

Measurements of the selected specimens are provided in Table 3. The largest pachyconic (ww/dm = 0.76) and robust specimen (NMMNH 80879; Fig. 5.4–5.6) has a diameter of dm = 66.66 mm. The subevolute to evolute umbilicus (uw/dm = 0.44) is very deeply incised with a steep umbilical wall and a very abrupt umbilical shoulder. The venter is subtriangular. The ornamentation of the conch consists of smooth and irregular, rectiradiate to slightly falcoid ribs, and very fine growth striae. The partly preserved shell of the largest specimen (GSUB C13196; Fig. 3.8–3.10) is very thick (1.5 mm at the venter and >3 mm along the umbilical shoulder).

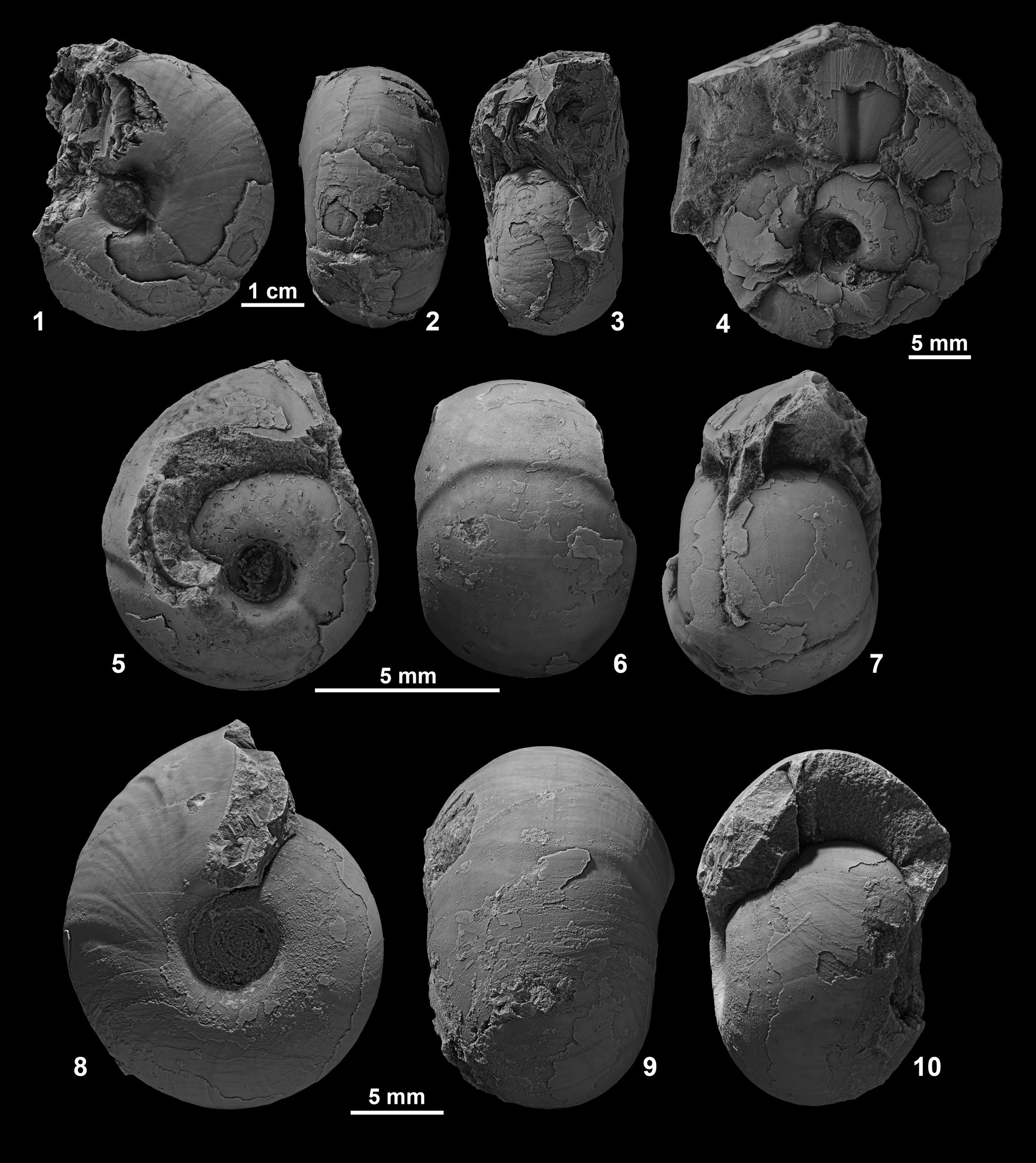

Figure 5. Ptychites gradinarui (1–6) from Rieber Gulch, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County, (1–3) NMMNH 80878, (4–6) NMMNH 80879; (7–14) from the Wildhorse-McCoy mine area, Churchill County, (7–10) GSUB C11443, (9) cast of deeply incised and funnel-shaped umbilicus; (11–14) NMMNH 80880, (12, 14) casts of deeply incised and funnel-shaped umbilicus.

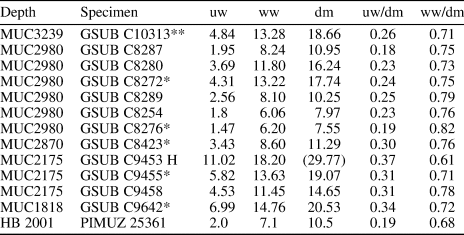

Table 3. Measurements in mm of selected specimens of Ptychites gradinarui Bucher, Reference Bucher1992 collected by J. Jenks and us in the Fossil Hill Member of the Favret Formation, Churchill and Pershing counties, Nevada, USA. For further details on the bed number, see Figure 2 (“Bed No.”). uw: maximum umbilical width; ww: maximum whorl width; dm: maximum diameter of shell; (): Fragmented specimens, estimated values; *: specimen used for ontogenetic analysis, cast present.

The partially preserved suture line of GSUB C13196 is illustrated in Figure 7. The umbilical part of the line is missing. The widths of U3/U2, U2, A/U2, A, and A/E of the herein described specimen (Fig. 7.1, 7.2) are comparable to those of the specimen published in Bucher, Reference Bucher1992 (Fig. 7.3 herein). The A lobe is trifid. As with the E/A illustrated in Bucher, Reference Bucher1992, this saddle is slender and less strongly denticulate than the others are. Bucher (Reference Bucher1992) did not illustrate the conch of the specimen he analyzed. However, since the whorl height of the specimen indicated is ~80 mm, the specimen must have had a similar conch size to the specimen of this study (whorl height of specimen GSUB C13196: 88.30 mm).

The largest discoidal (ww/dm = 0.46) specimen used for the ontogenetic analysis (GSUB C11443; Fig. 5.7–5.10), has a diameter of dm = 85.62 mm. The subinvolute umbilicus (uw/dm = 0.27) is also very deeply incised (Fig. 5.9). The umbilical wall is a little bit less steep than that of their more robust conspecifics. The venter of the discoidal specimen is subtriangular. The ornamentation, however, equals the robust specimens.

Ontogenetic description

The ontogenetic development of P. gradinarui is illustrated in Figure 8, and the raw data of the analysis are supplied in the Appendix. The whorl expansion rate (WER; Fig. 8.2) shows a triphasic behavior with a strong decrease in the earliest stages and a rather stable intermediate phase. In phase III, the WER increases again, indicating an acceleration of growth.

The values for the whorl width index (WWI) are more scattered than the other series (Fig. 8.3). Nevertheless, a triphasic development of the growth trajectories can be observed. In phase I and II, the conch width index (CWI) and the umbilical width index (UWI) describe opposing parabolas (Fig. 8.4). Ptychites gradinarui shows a trend of developing a slightly more pachyconic and less evolute conch in their early stages, resulting in a clock-wise progression (Fig. 8.5). In contrast to UWI, the CWI is a triphasic trajectory. Therefore, at growth stage 8.0, the two indices decouple. Whereas the UWI sticks to the parabolic curve progression, CWI quite abruptly decreases after whorl 8.0, causing a distinct buckle in the growth trajectories (Fig. 8.5). This means that in later ontogenetic stages, the species develops more discoidal and less evolute conches. Following the notation of Walton and Korn (Reference Walton and Korn2017), the morphologic development of P. gradinarui is characterized by a C-mode ontogeny.

In general, all the trajectories shown in Figure 8.2–8.5 show a change in direction towards the end of the phase II (growth stage 5.0 to 8.0; roughly corresponds to growth size of 9–27 mm; see also Appendix). These changes in the progression of the trajectories are interpreted to mark the transition from juvenile to adult stages. The analysis of a large pachyconic specimen would allow testing whether the two morphotypes (discoidal and pachyconic, see above) could be explained by sexual dimorphism. If more globous variants of this species show the same ontogenetic trends, at around the same growth stage, this would underpin the hypothesis of sexual dimorphism. However, no appropriate specimen was available.

Materials

Nine specimens (NMMNH 80877–80880, GSUB C11440–C11443, GSUB C13196).

Remarks

The diagnosis for this species is newly established here, due to a lack of a former diagnosis. This species appears to be endemic to Nevada, with its closest ally, P. sahadeva Diener, Reference Diener1895a, from the Himalayan region according to Bucher (Reference Bucher1992). Among the material herein, two different morphotypes can be distinguished—a more depressed type with a subtriangular venter and a slightly narrower umbilicus, and a robust variant with very abrupt umbilical shoulders. However, the ornamentation with irregular fine ribs, growth striae, and weak depressions are very similar. Furthermore, smaller specimens herein and the specimens illustrated in Bucher (Reference Bucher1992) seem to be intermediate to these two morphotypes. Because the biostratigraphic and geographic ranges of both morphotypes are also overlapping, the two morphotypes were assigned to one species, dimorphism cannot be excluded.

Ptychites densistriatus Bucher, Reference Bucher1992

Figures 6.12–6.14, 9.1–9.3

- Reference Bucher1992

Ptychites densistriatus; Bucher, p. 441, pl. 9, figs. 1–10.

Figure 6. (1–11) Ptychites gradinarui (1–5) from Rieber Gulch, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County, (1–3) GSUB C11442, (4, 5) GSUB C11441; (6–11) from the Wildhorse-McCoy Mine area, Churchill County, (6, 7) GSUB C11440, (8–11) NMMNH 80877, (10) cast of deeply incised and funnel-shaped umbilicus. (12–14) Ptychites densistriatus from the south side of Favret Canyon, Augusta Mountain, Pershing County, NMMNH 80881.

Figure 7. Adult suture of Ptychites gradinarui. Bracketed letters indicate traditional suture nomenclature. (1, 2) Suture lines drawn from specimen GSUB C13196, of which (2) is reversed. (3) Reversed suture line redrawn from Bucher, Reference Bucher1992, text-figure 22a.

Figure 8. Ontogenetic analysis of Ptychites gradinarui. (1) Cross section of the largest discoidal specimen GSUB C11443, scale bar units 5 mm. (2–4) Ontogenetic development of the whorl expansion rate (WERn = (dmn/dmn-0.5)2), whorl width index (WWIn = wwn/whn), umbilical width index (UWIn = uwn/dmn), and the conch width index (CWIn = wwn/dmn) plotted against number of half whorls (ontogenetic stages). (5) Ratio between UWI and CWI of the available specimens. Bubble size refers to number of half whorl; the picture in the background shows the shape of the last complete whorl (developed by Korn, Reference Korn2010). Roman numbers refer to interpretation of different life phases; I: Hatchling, II: Juvenile; III: Subadult–adult; for more detailed explanations see Walton and Korn (Reference Walton and Korn2017, p. 713).

Figure 9. (1–3) Ptychites densistriatus from Favret Canyon, Pershing County, Nevada, GSUB C11439. (4–10) Ptychites embreei n. sp. from Muller Canyon, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County, (4) GSUB C8273 (paratype), (5–7) GSUB C8254, (8–10) GSUB C8287 (paratype).

Holotype

According to Bucher (Reference Bucher1992), the holotype (USNM 448261), the paratypes (USNM 448259, 448260), and the plesiotype (USNM 448258) are all stored in the collection of the National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C., USA.

Diagnosis

Moderately sized species of Ptychites with a subinvolute (uw/dm ~0.25) and discoidal to pachyconic conch (ww/dm ~0.60). Whereas juvenile specimens are clearly pachyconic, the conch gets more depressed towards later ontogenetic stages. More rounded umbilical shoulder. Smooth shell with an ornament of thick radial growth striae.

Occurrence

Favret Canyon, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County: NMMNH loc. L 12280, F. rieberi Subzone, B. shoshonensis Zone.

Description

Measurements of the selected specimens are provided in Table 4. Specimen NMMNH 80881 (Fig. 6.12–6.14) is a complete conch with a maximum diameter of 53.49 mm. The discoidal to pachyconic shell (ww/dm = 0.60) is subinvolute (uw/dm = 0.24), revealing a deeply incised umbilicus with a steep umbilical wall and a narrowly rounded umbilical shoulder. The specimen is slightly ovoid. Furthermore, the almost smooth surface of the conch only bears smooth growth striae.

Table 4. Measurements in mm of selected specimens of Ptychites densistriatus Bucher, Reference Bucher1992 collected by J. Jenks in the Fossil Hill Member of the Favret Formation. Pershing County, Nevada, USA. For further details on the bed number, see Figure 2 (“Bed No.”). uw: maximum umbilical width; ww: maximum whorl width; dm: maximum diameter of shell; (): fragmented specimen, estimated value;**: specimen used for ontogenetic analysis, preservation not sufficient, cast present.

Materials

Two specimens (NMMNH 80881, GSUB C11439).

Remarks

The diagnosis for this species is newly established here, due to a lack of a former diagnosis. To our knowledge, this species in endemic to Nevada. Preservation of the available material did not allow a sutural and ontogenetic analysis.

Ptychites embreei new species

Figures 9.4–9.10, 10–13

- Reference Monnet and Bucher2005

Ptychites sp. indet; Monnet and Bucher, p. 49, pl. 23, fig. 9.

Figure 10. Ptychites embreei n. sp. from Muller Canyon, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County. (1–3) GSUB C8272, (4–6) GSUB C10313, (7–9) GSUB C8289 (paratype).

Figure 11. Ptychites embreei n. sp. from Muller Canyon, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County. (1–3) GSUB C8280 (paratype), (4–6) GSUB C9458 (paratype), (7–9) GSUB C9455, (10–12) GSUB C9642.

Figure 12. (1, 2) Holotype GSUB C9453 of Ptychites embreei n. sp. from Muller Canyon, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County.

Figure 13. Ontogenetic analysis of Ptychites embreei n. sp. (1) Cross section of specimen GSUB C9642, scale bar units 5 mm. (2–4): Ontogenetic development of the whorl expansion rate (WERn = (dmn/dmn-0.5)2), whorl width index (WWIn = wwn/whn), umbilical width index (UWIn = uwn/dmn) and the conch width index (CWIn = wwn/dmn) plotted against number of half whorls (ontogenetic stages). (5) Ratio between UWI and CWI of the available specimens. Bubble size refers to number of half whorl; the picture in the background shows the shape of the last complete whorl (developed by Korn, Reference Korn2010). Roman numbers refer to interpretation of different life phases; I: Hatchling, II: Juvenile; III: Subadult–adult; for more detailed explanations see Walton and Korn (Reference Walton and Korn2017).

Holotype

GSUB C9453 (Fig. 12), Fossil Hill Member of the Favret Formation, Muller Canyon in the Augusta Mountains, Pershing County, Nevada, USA.

Paratypes

Five specimens GSUB C8273 (Fig. 9.4), C8287 (Fig. 9.8–9.10), C8289 (Fig. 10.7–10.9), C8280 (Fig. 11.1–11.3), and C9458 (Fig. 11.7–11.9), Fossil Hill Member of the Favret Formation, Muller Canyon in the Augusta Mountains, Pershing County, Nevada, USA.

Diagnosis

Very small to small-sized and depressed Ptychites attaining a diameter <30 mm at maximum. Conch subinvolute to subevolute (uw/dm ~0.29) and pachyconic (ww/dm ~0.73). Smooth surface of shell with a fine ornament of striae. More rounded umbilical shoulder.

Occurrence

Muller Canyon, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County: GSUB loc. MUC, from M. spinifer Subzone, G. mimetus Zone to P. meeki Subzone, P. meeki Zone. McCoy Mine, Churchill County: Loc. HB 2001, B. cordeyi Subzone, G. weitschati Zone (Monnet and Bucher, Reference Monnet and Bucher2005, specimen PIMUZ 25361).

Description

Measurements of the selected specimens are provided in Table 5. The holotype (GSUB C9453; Fig. 12) is a complete specimen with a maximum diameter of 29.77 mm. Because of its large size, compared to other representatives of this new species, it is interpreted as an adult specimen; there are no other criteria for maturity. The pachyconic (ww/dm = 0.61) shell is subevolute (uw/dm = 0.37) and reveals a deeply incised umbilicus with a steep umbilical wall and a distinctive umbilical shoulder. The surface of the shell is smooth and bears a very fine ornament of striae. The venter is perfectly rounded and smooth.

Table 5. Measurements in mm of selected specimen of Ptychites embreei n. sp. collected in the Fossil Hill Member of the Favret Formation at the Muller Canyon locality in the Augusta Mountains. Pershing County. Nevada. USA. Further details on the bed number see Figure 2 (“Bed No.”). uw: maximum umbilical width; ww: Maximum whorl width; dm: maximum diameter of shell; (): fragmented specimen, estimated value; *: specimens used for ontogenetic analysis, cast present; **: specimen used for ontogenetic analysis, preservation not sufficient, cast present; H: holotype.

In general, smaller specimens are subinvolute and slightly more depressed than larger specimens (see Table 5). Furthermore, the umbilical shoulder is more abrupt. The internal molds of some specimens show growth constrictions (C8273, Fig. 9.4; C8254, Fig. 9.5, 9.6; C8287, Fig. 9.9).

Ontogenetic description

The ontogenetic development of P. embreei n. sp. is illustrated in Figure 13, and the raw data of the analysis are supplied in the Appendix. The whorl expansion rate (WER; Fig. 13.2) shows a regular behavior with a strong decrease in the earliest stages, followed by more stable state towards the end of phase II. The slightly higher values of half whorl 7.5 and 8.5 suggest a possible acceleration of growth in later ontogenetic stages.

The values for the whorl width index (WWI; Fig. 13.3) are more scattered than the other series. However, considering the shape of the CWI trajectory (Fig. 13.4) and the more regular WWI of P. gradinarui (Fig. 8.3), it can be assumed that the progression of WWI is at least triphasic.

During phase I and II, the trajectories for the conch width index (CWI) and the umbilical width index (UWI) are inverse (Fig. 13.4), indicating a close relationship between these two indices. The development of UWI and CWI is similar to the C-mode ontogeny introduced by Walton and Korn (Reference Walton and Korn2017). However, towards later ontogenetic stages, the UWI and CWI are decoupled, which distinguishes P. embreei n. sp. from regular C-mode ontogeny. Whereas the conches of early stage P. embreei n. sp. are more globous and more involute, in the course of their growth they build slightly more discoidal and more evolute conches, resulting in a counterclockwise progression (Fig. 13.5). The decoupling of the CWI and UWI results in a distinct buckle in the progression. In general, all the trajectories (Fig. 13.2–13.5) that are long enough show a change towards the end of the second phase (growth stage 5.0 to 8.0; roughly corresponds to a growth size of 12–19 mm). These changes in the progression of the trajectories most probably mark the transition from the juvenile to the adult stage.

Etymology

The species was named in honor of geologist Patrick G. Embree (Orangevale, CA, USA) for his contributions and broad support of the research on the Triassic of Nevada.

Materials

In total, we collected 38 specimens of P. embreei n. sp. in Muller Canyon of the Augusta Mountains, Pershing County, NW Nevada, USA. Two specimens: GSUB C9642, C9643, from bed No. MUC1818; 10 specimens: GSUB C9453, C9455–C9462, C8564, from bed No. MUC2175; one specimen: GSUB C8423, from bed No. MUC2870; 19 specimens: GSUB C8254, C8265, C8267, C8269, C8270, C8272–C8280, C8285–C8287, C8290, from bed No. MUC2980; and six specimens: GSUB C9619, C9621–C9624, C10313; from bed No. MUC3239. The specimen PIMUZ 25361 was illustrated in Monnet and Bucher (Reference Monnet and Bucher2005) and is stored in the original collection of the Paleontological Institute and Museum University of Zurich, Switzerland. For further explanation on the beds see Figure 2.

Remarks

Specimen PIMUZ 25361, referred to as Ptychites sp. indet. by Monnet and Bucher (Reference Monnet and Bucher2005), is regarded as conspecific with P. embreei n. sp. Among the ptychitids of Nevada, P. embreei n. sp. covers by far the largest time span. It remains to be clarified whether this is due to biological processes or reflects a bias caused by more intensive sampling associated with this study relative to prior work.

There are two more globular genera occurring in sediments of the same age in Nevada: Humboldtites Silberling and Nichols, Reference Silberling and Nichols1982 and Proarcestes Mojsisovics, Reference Mojsisovics1893. Both genera differ from representatives of P. embreei n. sp. through their very involute to closed umbilicus and the more compressed shape. Furthermore, their suture lines have much narrower main saddles and a more constricted base.

Mojsisovics (Reference Mojsisovics1882, p. 244) divided all species of Ptychites in five different groups: P. rugiferi, P. megalodisci, P. subflexuosi, P. opulenti, and P. flexuosi. Ptychites embreei n. sp. is included into the group of P. opulenti because it agrees in being predominantly globular. The distinguishing morphologic features of different species of this group are given in Table 6. In summary, representatives of P. embreei n sp. differ from other Ptychites species mainly in having smaller growth size, the absence of ribs, and the more rounded umbilical shoulder.

Table 6. Morphologic comparison of different species of Ptychites of the P. opulentus group to the newly introduced species P. embreei n. sp. For biostratigraphic and geographic distribution, see Figure 15. U and uw: maximum umbilical width; D and dm: maximum diameter of conch; S.s.: Small specimens; L.s.: Large specimens.

The range of intraspecific variability among the material described herein is rather small. The largest differences seem to result from ontogenetic processes, which is also the case with certain Paleozoic ammonoids (e.g., Korn, Reference Korn2017; Korn et al., Reference Korn, Price and Weyer2018), in which the trajectories for CWI and UWI are inverses (Fig. 13.4), indicating a close relationship between these two indices. This means that, in agreement with Buckman's first Rule of Covariation (Westermann, Reference Westermann1966), compression co-occurs with less evolute conches.

Morphospace

In order to analyze the ontogenetic morphospaces of Ptychites gradinarui and P. embreei n. sp., a principal component analysis was performed (Fig. 14). Despite the low number of available specimens, the ontogenetic morphospaces of the two species are clearly separated in the PCA plot. The first two principal components of the PCA explain ~81.52% (PC 1: 73.76%; PC 2: 7.76%) of the observed variation. The raw data for the analysis are provided in the Appendix.

Figure 14. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of combined ontogenetic stages of all available specimens of Ptychites gradinarui and Ptychites embreei n. sp. The parameters whorl expansion rate (WER), umbilical width index (UWI), and conch width index (CWI) were used. Every individual is defined by the sum of all parameters of all ontogenetic stages. Black dots P. gradinarui, gray dots P. embreei n. sp.

The first principal component (PC1) is mainly dominated by values of the umbilical width index (UWI) and the conch width index (CWI), which have similar loadings. On principal component 2 (PC2), however, values for the whorl expansion rate (WER) alone feature dominantly. Therefore, the axes of the analysis reflect the following: (1) high PC 1 values express a more depressed and lower values a more compressed conch shape, and (2) high PC 2 values mainly coincide with a higher WER. The right part of the morphospace is thus occupied by more pachyconic, and the left part with rather discoidal conches. Most of the ontogenetic changes are captured within changes of the umbilical diameter and the conch width. Even though P. gradinarui generally reaches a much larger growth size, the whorl expansion rate seems to be of minor importance for the distinction of the ontogenetic pathways of these species.

Geographic and stratigraphic occurrence of ptychitids

During the Middle Triassic, representatives of Ptychites were widely distributed in the Panthalassic as well as the Tethys Ocean. Here we present a summary of the biostratigraphic distribution of Ptychites spp. in the most significant domains (Fig. 15). The different biostratigraphic occurrences of P. guloensis in Nevada and British Columbia are possibly biased by a low number of specimens. However, it is apparent that the faunas of Nevada and British Columbia are similar in composition to a certain degree.

Figure 15. Biostratigraphic distribution of Ptychites spp. The biostratigraphic framework and correlation of Nevada, British Columbia, and the Tethyan realm follows Jenks et al. (Reference Jenks, Monnet, Balini, Brayard, Meier, Klug, Korn, De Baets, Kruta and Mapes2015). For the correlation of Spitsbergen, Harland and Geddes (Reference Harland, Geddes and Harland1997) and Weitschat and Lehmann (Reference Weitschat and Lehmann1983) were used. Only representatives of Ptychites discussed in this publication are listed in this table. Therefore, empty boxes do not necessarily indicate the absence of all Ptychites spp. * Indicates location of the “Ptychiten Kalke—Ptychites layers” (e.g., Mojsisovics, Reference Mojsisovics1886; Spath, Reference Spath1921; Gugenberger, Reference Gugenberger1927; Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg1952; Harland and Geddes, Reference Harland, Geddes and Harland1997). Paleogeographic locations of the localities are provided in Figure 1. ** According to Weitschat (Reference Weitschat1986, p. 253), the preservation of middle Anisian ammonoids of Spitsbergen is not sufficient for a successful zonation of the area. Crosses mark gaps in the ammonoid biostratigraphic framework.

Representatives of Flexoptychites, closely allied to Ptychites, were also described from the isolated Germanic Muschelkalk Sea (e.g., Claus, Reference Claus1921, Reference Claus1955; Urlichs and Kurzweil, Reference Urlichs and Kurzweil1977), which is characterized by an endemic ammonoid fauna. In fact, ptychitids are known from the Lower and the Upper Muschelkalk, probably reflecting that the endemism is higher in the Upper Muschelkalk (see Urlichs and Mundlos, Reference Urlichs, Mundlos, Bayer and Seilacher1985; Kaim and Niedźwiedzki, Reference Kaim and Niedźwiedzki1999). However, based on the description and illustrations in the former, it cannot be verified with certainty whether the described specimens really belong to Ptychites or closely allied forms. Furthermore, Urlichs and Mundlos (Reference Urlichs, Mundlos, Bayer and Seilacher1985) and Balini (Reference Balini1998) doubted that those occurrences were part of a living population and suggested a post-mortem drift of the shells from the Tethys. For those reasons, the Germanic Muschelkalk Basin was not considered in the summary of the biostratigraphical occurrences of ptychitids during the Anisian stage (Fig. 15).

Discussion

Representatives of Ptychites can be found in sediments that were deposited in the Panthalassic (e.g., Smith, Reference Smith1914; McLearn, Reference McLearn1948; Tozer, Reference Tozer1994; Monnet and Bucher, Reference Monnet and Bucher2005) and Tethyan Oceans (e.g., Diener, Reference Diener1913; Waterhouse, Reference Waterhouse1994, Reference Waterhouse1999, Reference Waterhouse2002a, Reference Waterhouseb). Due to its almost global distribution, the genus Ptychites has been broadly discussed in the literature, but limited research has been done in recent years. Especially the correlation between the Tethyan and Panthalassic faunas still demands further attention. In the Panthalassic realm, the co-occurrence of ptychitids in Nevada and British Columbia supports the statement of Ji and Bucher (Reference Ji and Bucher2018) that low- and mid-paleolatitude regions were well connected during the Middle Triassic. This stresses the importance of re-evaluation of the alpha taxonomy of ptychitid species by novel or underexplored methods, as performed in this study.

Ontogenetic analysis

Ammonoid generic diversity reached its maximum during the Triassic Period (Brayard et al., Reference Brayard, Escarguel, Bucher, Monnet, Brühwiler, Goudemand, Galfetti and Guex2009). At present, few studies have investigated trends in morphological disparity of Triassic ammonoids (Monnet et al., Reference Monnet, Brayard, Brosse, Klug, Korn, De Baets, Kruta and Mapes2015). McGowan (Reference McGowan2004, Reference McGowan2005) and Brosse et al. (Reference Brosse, Brayard, Fara and Neige2013) carried out important foundational research in this field. Although the background data of both studies differ significantly, both come to the same conclusion: the taxonomic diversity and morphologic disparity of Triassic ammonoids are decoupled. However, it is open to debate whether the high diversity is also biased by taxonomic over-splitting (Forey et al., Reference Forey, Fortey, Kenrick and Smith2004; De Baets et al., Reference De Baets, Klug and Monnet2013) of the ammonoid faunas.

A method, whose potential is far from being fully exploited, is the analysis of ontogenetic trajectories obtained from longitudinal cross-sections. The accretionary growth of ammonoids with conservation of juvenile stages allows the investigation of complete ontogenetic transformations of a set of traits, such as the conch geometry and septal characters (Korn, Reference Korn2012). Therefore, ontogenetic analyses are an ideal tool to unravel phylogenetic and taxonomic relationships between ammonoid groups (Rieber, Reference Rieber1962). This makes them ideal for the study of evolutionary change in ontogeny through time (Naglik et al., Reference Naglik, Monnet, Goetz, Kolb, De Baets, Tajika and Klug2015).

Walton and Korn (Reference Walton and Korn2017) carried out an extensive comparative ontogenetic analysis of ammonoids within the pachyconic to globular morphospace. They introduced the term C-mode ontogeny, which is by far the most common ontogeny of pachyconic to globular ammonoids. Whereas the herein discussed species P. gradinarui shows a C-mode ontogeny, P. embreei n. sp. has a different development. In phase I and II, P. embreei n. sp. and P. gradinarui have opposing trends in their relationships of the CWI and UWI (Figs. 8.5, 13.5). However, both trajectories show a distinct buckle in the curve that marks the decoupling of the UWI and CWI, which is approximately located at an UWI of 0.35 and CWI of 0.70. The change in the direction of the progression marks the onset of the third phase, during which both trajectories behave more or less collinear. According to Walton and Korn (Reference Walton and Korn2017), the change in conch morphologies during ontogeny could be caused by the adaptation to different niche types in the different life phases. It is questionable, whether the disparity of these two groups is significant enough to suggest two different modes of life during the earliest life phases. Nevertheless, it is very interesting to note that ptychitids have very distinct ontogenetic developments even at the species level.

In general, there is limited literature on ontogenetic analysis of individual species. However, in their study of heteromorph ammonites of the Early Cretaceous, Hoffmann et al. (Reference Hoffmann, Weinkauf, Wiedenroth, Goeddertz and De Baets2019) used similar multivariate methods as described in this study. Their study proved that the statistical evaluation of ontogenetic trajectories of ammonoids provides useful information about diversity and disparity at species level. Our study verifies that the statistical evaluation of ontogenetic processes is applicable to normally coiled planispiral ammonoid species from the Middle Triassic. Important ontogenetic changes can be visualized using univariate (Figs. 8, 13) and multivariate (Fig. 14) methods. Despite a low number of available specimens, the principal component analysis succeeded in separating the two ontogenetic morphospaces of the two ammonoid groups. This highlights the uniqueness of the ontogenetic trajectories and morphospaces that representatives of this group occupy.

Sutures

The tapering U2/A saddle and the U1/U4 with a slender spur appear to be unique sutural features among ptychitids. However, due to the lack of specimens for comparison, it remains unclear if this is significant. No further features of the suture line of GSUB C13194, P. guloensis, seem to be unique (e.g., bifid endings in the A lobe occur in our material as well as in other specimens referred to the genus; sutures of P. opulentus Mojsisovics, Reference Mojsisovics1882 [Qingge et al., Reference Qingge, Guoxiong and Yigang1980]; Flexoptychites cf. cochleatus [Oppel, Reference Oppel1863] and P. cf. asura Diener, Reference Diener1895b [Win, Reference Win1991]). Our examination of published suture lines in ptychitids underlines the opinion of Köhler-Lopez and Lehmann (Reference Köhler-Lopez and Lehmann1984, p. 63) that suture lines of ptychitids vary significantly, “much in degree of incision,” but “not in the number of elements.” These authors state that the lateral saddle of the very well-investigated species Aristoptychites kolymensis Kiparisova, Reference Kiparisova1937 is always extremely small and narrow. This is true for many specimens of closely related genera and their species as well, but there are exceptions to this rule and thus this cannot be generalized for this group (e.g., P. cf. cochleatus in Win, Reference Win1991). We see no clear relation of sutural features to the conch morphology of ptychitid genera. The suture lines are highly dependent on the growth stage. The very large specimen GSUB C13196 (P. gradinarui, Figs. 3.8–3.10, 8) shows clearly more incisions of lobes and saddles than specimens in earlier stages. Specimen GSUB C13194 (P. guloensis, Figs. 3.5–3.7, 4) does not show the sutural development and thus we cannot discuss the ontogeny of the suture line of the species based on our material. Nevertheless, the high number of sutural elements at the umbilical seam might indicate a multiplication of elements of the U3 as recorded by Kullmann and Wiedmann (Reference Kullmann and Wiedmann1970). The latter was called a sutural lobe due to its position at the umbilical seam (Wedekind, Reference Wedekind1916; “sutural” means umbilical seam in this respect); this term is problematic, though, because it only refers to the position on the shell. Köhler-Lopez and Lehmann (Reference Köhler-Lopez and Lehmann1984) nicely show that the U1 (with multiple subdivisions) can be located at this position as well. Therefore, we agree with Köhler-Lopez and Lehmann (Reference Köhler-Lopez and Lehmann1984) that a U3 developed as a sutural lobe does not characterize Ptychitidae. In fact, the sutures of many species of Ptychites and closely allied genera do not show this feature, including P. compressus Yabe and Shimizu, Reference Yabe and Shimizu1927; P. guloensis; P. opulentus; P. wrighti; Discoptychites megalodiscus (Beyrich, Reference Beyrich1967); Flexoptychites flexuosus (Mojsisovics, Reference Mojsisovics1882); and Malletoptychites malletianus (see Diener, Reference Diener1895a; Onuki and Bando, Reference Onuki and Bando1959; McLearn, Reference McLearn1969; Qingge et al., Reference Qingge, Guoxiong and Yigang1980).

Conclusions

Here we enhance the taxonomic understanding of ptychitids, including a description of Ptychites embreei n. sp. from the late Anisian of Nevada. According to the state of the art, this species is the longest-ranging within the group. Furthermore, it fills a gap in the otherwise intensively studied ammonoid fauna of north-western Nevada, USA.

After the Permian/Triassic boundary, Ptychitoidea, Megaphyllitoidea, and Arcestoidea filled the cadicone morphospace (Brosse et al., Reference Brosse, Brayard, Fara and Neige2013; De Baets et al., Reference De Baets, Hoffmann, Sessa and Klug2016, fig. 7). Despite the wide geographic distribution of ptychitids, they exhibit a remarkably low level of morphological variation within their morphospace. Since all ptychitids have an almost smooth shell, with a subordinate ornamentation only, one of the most important morphological descriptive features of ammonoids (Klug et al., Reference Klug, Korn, Landman, Tanabe, De Baets, Naglik, Klug, Korn, De Baets, Kruta and Mapes2015) is not applicable to the group. This means there are narrow limits regarding the shell variability in the cadicone morphospace in the Anisian, with mostly leiostracan forms (smooth shelled ammonoids; Westermann, Reference Westermann, Landman, Tanabe and Davis1996). However, some features characterizing the species seem to be hidden in a distinct ontogeny (Figs. 8, 13, 14). We emphasize the ontogenetic differences of ptychitids to other Middle Triassic ammonoids of Nevada. Ptychitids, despite their similar morphologies, have unique ontogenetic trajectories, as demonstrated above (Figs. 8, 13). Ontogenetic analyses are therefore an ideal tool to improve the alpha taxonomy of ptychitids.

Since the evaluation of ontogenetic trajectories is a rather descriptive and therefore, to some extent, subjective process, a great potential of this method lies within their statistical quantification and interpretation. This study includes one of the first attempts to quantify the ontogenetic development of individuals using statistical methods. The analysis of the very distinct ontogenetic pathways of ptychitids will serve as an important cornerstone in future studies on the statistical quantification of ontogenetic analyses of ammonoids.

Acknowledgments

First, we thank J. Jenks (Utah, USA) for providing valuable material for this study and his agreement to house these specimens at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science in Albuquerque, USA. N. Ridgwell (Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA) is thanked for transferring the material collected by J. Jenks and its inventory. D. Kuhlmann (Bremen, Germany) did the mechanical preparation of the material collected by our working group and M. Krogmann (Bremen, Germany) is thanked for his broad support in the artwork for this article. Furthermore, we thank C. Anderson for critically reading the manuscript and improving the English. We would also like to express many thanks to C. Schulbert (Erlangen, Germany) and J. Titschack (Bremen, Germany) for testing CT scanning of the material at hand. C. Klug (Zurich, Switzerland) we thank for casting a specimen from the PIMUZ collection. We thank the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management (BLM, Nevada State office, Winnemucca District) for permission to collect samples in the Wilderness Study Area of the Augusta Mountains, Pershing County. This research received support from the German Science Foundation (DFG), project “Nevammonoidea” (LE 1241/3-1). We thank both reviewers, C. Monnet (Lille) and M. Balini (Milan), for their very useful comments.

Appendix

Morphometric data for the available specimens that were measured on the cross-sections and used for the ontogenetic analysis in this study. dm: maximum diameter at respective growth stage (number of half whorl); ww: maximum whorl width (in mm); wh: maximum whorl height (in mm); uw: maximum umbilical width (calculated, in mm); WERn = (dmn/dmn-0.5)2, whorl expansion rate; UWIn = uwn/dmn, umbilical width index; CWIn = wwn/dmn, conch width index; WWIn = wwn/whn, whorl width index.