Introduction

During the early Cambrian, East Antarctica was sutured between the now southern coast of Australia, Southeast Africa, and India and located at tropical latitudes (Brock et al., Reference Brock, Engelbrechtsen, Jago, Kruse, Laurie, Shergold, Shi and Sorauf2000; Torsvik and Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2013a, Reference Torsvik and Cocksb). The Shackleton Limestone crops out meridionally and episodically along the Central Transantarctic Mountains (Fig. 1). While the true thickness of this carbonate unit remains uncertain (Myrow et al., Reference Myrow, Pope, Goodge, Fischer and Palmer2002), it is estimated to be up to 2,000 m thick in places (Laird et al., Reference Laird, Mansergh and Chappell1971; Burgess and Lammerink, Reference Burgess and Lammerink1979). The unit consists of many lithofacies including sandy carbonates, pure limestones, and archaeocyath-microbialite bioherms (Rees et al., Reference Rees, Pratt and Rowell1989; Myrow et al., Reference Myrow, Pope, Goodge, Fischer and Palmer2002). The newly recovered fauna from measured stratigraphic sections through autochthonous exposures of the Byrd Group, central Transantarctic Mountains, includes archaeocyaths, brachiopods, bradoriid arthropods, cambroclavids, chancelloriids, hyoliths, sponge spicules, and tommotiids. This paper focusses on descriptions and biostratigraphy of eight helcionelloids, two pelagiellids, one scenellid, and the bivalve Pojetaia runnegari Jell, Reference Jell1980. Helcionelloids are typical components of ‘small shelly fossil’ (SSF) assemblages in lower Cambrian (Terreneuvian, Cambrian Series 2) strata around the world (Bengtson, Reference Bengtson2004; Kouchinsky et al., Reference Kouchinsky, Bengtson, Runnegar, Skovsted, Steiner and Vendrasco2012). Widespread phosphatized steinkerns of micromorphic univalved helcionelloids appear in the pre-trilobitic Terreneuvian (Khomentovsky et al., Reference Khomentovsky, Val'kov, Karlove, Khomentovsky, Yakshin and Karlove1990; Kouchinsky et al., Reference Kouchinsky, Bengtson, Runnegar, Skovsted, Steiner and Vendrasco2012) and range through to the Early Ordovician (Gubanov and Peel, Reference Gubanov and Peel2001; Peel and Horný, Reference Peel and Horný2004).

Figure 1. (1) Map of Antarctica showing approximate extent of the Transantarctic Mountains and area shown in (2). (2) Map of Nimrod Glacier, Holyoake Range, and Churchill Mountains. (3) Generalized relationship of Cambrian (Byrd Group) and Neoproterozoic (Beardmore Group) rock units of the Holyoake Range, adapted from Myrow et al. (Reference Myrow, Pope, Goodge, Fischer and Palmer2002). (4) Simplified geological map of the Holyoake Range, adapted from Myrow et al. (Reference Myrow, Pope, Goodge, Fischer and Palmer2002).

The taxonomic position of helcionelloids remains unresolved, with numerous authors suggesting different affinities and phylogenetic relationships (Parkhaev Reference Parkhaev, Ponder and Lindberg2008, table 3.1). Early efforts placed some asymmetrically coiled helcionelloids in the late Paleozoic macluritid gastropods and bilaterally symmetrical forms with the monoplacophoran tryblidiids—then considered a ‘primitive’ gastropod taxon (Knight, Reference Knight1952). Helcionelloids have also been suggested by some authors to be basal to the rest of the Gastropoda (e.g., Golikov and Starobogatov, Reference Golikov and Starobogatov1975; Runnegar and Jell, Reference Runnegar and Jell1976; Parkhaev, Reference Parkhaev2017a); a polyphyletic approach was proposed by other authors, with some helcionelloids considered ancestral to the major groups of mollusks (Runnegar and Jell, Reference Runnegar and Jell1976, fig. 4; Runnegar, Reference Runnegar1983, fig. 1) while others (the superfamily Helcionellacea Wenz, Reference Wenz1938) were referred to the monoplacophorans. Problems with these classification schemes are apparent, as a diagnostic criterion of the gastropods is torsion (Salvini-Plawen, Reference Salvini-Plawen1980; Ponder and Lindberg, Reference Ponder and Lindberg1997), a characteristic obvious only in soft anatomy and never convincingly demonstrated in any helcionelloid taxon (but see Runnegar, Reference Runnegar1981). A monoplacophoran affinity is also difficult to demonstrate as helcionelloids invariably lack the serially repeated muscles scars on the shell interior reflecting the muscle attachment common to all extant monoplacophorans (Lindberg, Reference Lindberg2009). Lindsey and Kier (Reference Lindsey and Kier1984) hypothesized a separate paraphyletic class for some asymmetrical helcionelloid mollusks (the Paragastropoda) on the basis that they lacked evidence of both torsion and serially repeated muscle scars, which included the pelagiellids. However, the asymmetrically coiled pelagiellids are perhaps the best candidates for inclusion in the gastropods. Preserved features such as muscle scars similar to those found in torted gastropods (Landing et al., Reference Landing, Geyer and Bartowski2002, fig. 9), a large mantle cavity, and potential anal notch have been inferred by some authors as indirect evidence of torsion (Landing et al., Reference Landing, Geyer and Bartowski2002). The class Helcionelloida Peel, Reference Peel, Simonetta and Conway Morris1991a was erected to include bilaterally symmetrical forms, excluding asymmetrical forms of the Paragastropoda. Recognized sinistral and dextral asymmetrical deviations from typically symmetric forms remain within Helcionelloida (Gubanov and Peel, Reference Gubanov and Peel2000). Recent systematic treatment of pelagiellids has them assigned to the helcionelloids (e.g., Skovsted and Peel, Reference Skovsted and Peel2007; Topper et al., Reference Topper, Brock, Skovsted and Paterson2009; Wotte and Sundberg, Reference Wotte and Sundberg2017) or to the gastropods (e.g., Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer and Bartowski2002; Parkhaev, Reference Parkhaev2007a, Reference Parkhaev2017a).

While many authors have worked on the paleobiology of the helcionelloids (e.g., Peel, Reference Peel, Simonetta and Conway Morris1991a; Brock, Reference Brock1998; Parkhaev, Reference Parkhaev2000, Reference Parkhaev2001), these and other SSFs can also be utilized in biostratigraphy, with certain caveats. Parkhaev in Gravestock et al. (Reference Gravestock2001) created loosely defined molluscan assemblage ‘zones’ for their work on the biostratigraphy of the lower Cambrian succession in the Stansbury Basin, South Australia. These were defined according to the presence of certain key taxa, and four ‘zones’ were recognized (oldest to youngest): Pelagiella subangulata, Bemella communis, Stenotheca drepanoida, and Pelagiella madianensis ‘zones.’ Jacquet et al. (Reference Jacquet, Brougham, Skovsted, Jago, Laurie, Betts, Topper and Brock2017) criticized these molluscan biozones noting they have very poorly defined boundaries and are based on poorly preserved, long-ranging taxa with considerable overlapping ranges. Close inspection of the data provided by Gravestock et al. (Reference Gravestock2001) reveals clear temporal discrepancies between the sections on Yorke and Fleurieu peninsulas (see Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Brougham, Skovsted, Jago, Laurie, Betts, Topper and Brock2017, p. 1093–1094 for details; Betts et al., Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2016a).

Broad biostratigraphic correlations of lower Cambrian rocks have proven difficult due to strong provincialism and facies dependence in faunas (Landing, Reference Landing, Lipps and Signor1992; Mount and Signor, Reference Mount, Signor, Lipps and Signor1992; Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Li and Zhu2004, Reference Steiner, Li, Qian, Zhu and Erdtmann2007; Landing et al., Reference Landing, Geyer, Brasier and Bowring2013; Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Betts and Brock2016a; Yun et al., Reference Yun, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Liu2016). Betts et al. (Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2016a, Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2017) created regional SSF biozones for the early Cambrian of South Australia and used mollusks as key accessory taxa. The choice of the primarily phosphatic tommotiid taxa Kulparina rostrata Conway Morris and Bengtson in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990, Micrina etheridgei (Tate, Reference Tate1892), and Dailyatia odyssei Evans and Rowell, Reference Evans and Rowell1990 to define these zones avoided some of the taxonomic and taphonomic problems associated with facies dependence and incomplete steinkern preservation in lower Cambrian carbonates (Mount and Signor, Reference Mount, Signor, Lipps and Signor1992; Jacquet et al. Reference Jacquet, Betts and Brock2016a). Molluskan steinkerns are also often difficult to identify accurately to species level due to lack of information on the shell exterior, especially micro-ornament and other surficial features, an important criterion for species differentiation (Skovsted, Reference Skovsted2006a; Betts et al., Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2016b; Jacquet and Brock, Reference Jacquet and Brock2016). The base of Cambrian Series 2, Stage 3, remains unresolved, although the first appearance datum of trilobites occurs around this boundary (see Babcock et al., Reference Babcock, Peng and Ahlberg2017 and Zhang et al., Reference Zhang2017 for recent reviews). The use of SSFs, including mollusks, for establishing regional bases of Series 2 and Stage 3 has been put forward by some authors, for example, the Pelagiella subangulata taxon-range zone for South China (Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Li, Qian, Zhu and Erdtmann2007, Reference Steiner, Li and Ergaliev2011).

The fossils described herein are almost exclusively steinkerns of calcium phosphate, with occasional external molds. Primary mineralized or secondarily replaced shells are not present, but mineral imprints are present on the exterior of some steinkerns, which correspond to a variety of calcitic or aragonitic crystal morphologies. Examples of this, among others, include polygonal imprints that are interpreted as calcitic semi-nacre (Kouchinsky, Reference Kouchinsky2000; Vendrasco et al., Reference Vendrasco, Porter, Kouchinsky, Li and Fernandez2010; Vendrasco and Checa, Reference Vendrasco and Checa2015) and elongated crystal laths that are interpreted to be aragonitic (Landing and Bartowski, Reference Landing and Bartowski1996; Kouchinsky, Reference Kouchinsky2000; Landing et al., Reference Landing, Geyer and Bartowski2002; Vendrasco et al., Reference Vendrasco, Porter, Kouchinsky, Li and Fernandez2010; Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Yun and Li2017). The chemical formation of phosphatic steinkerns is biased toward micromorphic forms (Creveling et al., Reference Creveling, Knoll and Johnston2014), suggesting some helcionelloid fossils might represent the juvenile shells (protoconchs) of macroscopic univalved mollusks (see Martí-Mus et al., Reference Martí-Mus, Palacios and Jensen2008; Jacquet and Brock, Reference Jacquet and Brock2016; Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Jago and Brock2016b). One of the first quantitative analyses of the fidelity of steinkern representation of the original shell identified the size of the umbilicus of anisostrophically coiled Ordovician mollusks as an indicator of the size of the original organism (Dattilo et al., Reference Dattilo, Freeman, Peters, Heimbrock, Deline, Martin, Kallmeyer, Reeder and Argast2016. This indicated the size of the steinkerns of the micromolluskan fauna studied was taphonomically, not ecologically, controlled. The basic size of the steinkern therefore cannot be used to indicate ontogeny, and morphological differences between two steinkerns of the same size may not indicate taxonomically meaningful differences. The term ‘teilsteinkern’ was introduced to describe incomplete internal molds (Dattilo et al., Reference Dattilo, Freeman, Peters, Heimbrock, Deline, Martin, Kallmeyer, Reeder and Argast2016).

Some evidence suggests that the preservation of phosphatic steinkerns is tied to particular lithologies and depositional processes. Phosphate replacement and coating of originally calcareous fossils was related to phosphate precipitation and intense denitrification within sediments or above an oxygen minimum zone (Landing Reference Landing, Lipps and Signor1992; Landing et al., Reference Landing, Geyer and Bartowski2002). Subsequently, Jacquet et al. (Reference Jacquet, Betts and Brock2016a) noted the occurrence of abundant micromolluskan residues was linked to facies characterized by sediment reworking (i.e., tempestites) or low sedimentation rates (i.e., firmgrounds and true hardgrounds).

Geological setting and previous work

The bulk of fossil material recovered is derived from an archaeocyath-rich biohermal unit near the top of a stratigraphic section (HRA) measured through the Shackleton Limestone and the overlying dark nodular carbonates and interbedded calc-siltsones of the Holyoake Formation. These rock units make up part of the Byrd Group (Figs. 1, 2), which crops out along the Central Transantarctic Mountains (Myrow et al., Reference Myrow, Pope, Goodge, Fischer and Palmer2002). The deposition of the Shackleton Limestone was interrupted by the Ross Orogenic events, involving a change in the East Antarctic plate margin from passive to orogenic subduction regime (Boger and Miller, Reference Boger and Miller2004). Subsidence resulted in a brief marine transgression across the continental shelf and deposition of the deeper-water argillaceous Holyoake Formation (Goodge et al., Reference Goodge, Walker and Hansen1993, Reference Goodge, Myrow, Philips, Fanning and Williams2004; Myrow et al., Reference Myrow, Pope, Goodge, Fischer and Palmer2002) at approximately 515–510 Ma (Paulsen et al., Reference Paulsen, Encarnación, Grunow, Layer and Watkeys2007). This was followed by a shallowing succession and ?syn-orogenic deposition of fine to medium calcareous sandstones of the Starshot Formation and overlying boulder conglomerates of the Douglas Conglomerate (Rowell et al., Reference Rowell, Rees, Cooper and Pratt1988a; Myrow et al., Reference Myrow, Pope, Goodge, Fischer and Palmer2002; Goodge et al., Reference Goodge, Myrow, Philips, Fanning and Williams2004; Paulsen et al., Reference Paulsen, Encarnación, Grunow, Layer and Watkeys2007). Stratigraphic sections through the Shackleton Limestone have proven difficult to interpret into a coherent in situ stratigraphy due to pervasive folding and faulting (including fault repetition) of the carbonate-dominated succession, the result of tectonism associated with the Ross Orogeny (Paulsen et al., Reference Paulsen, Encarnación, Grunow, Layer and Watkeys2007).

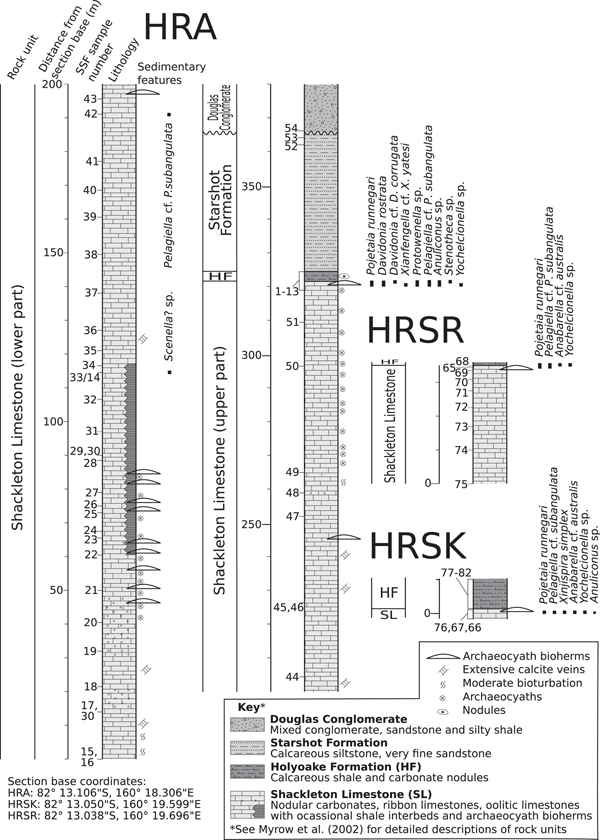

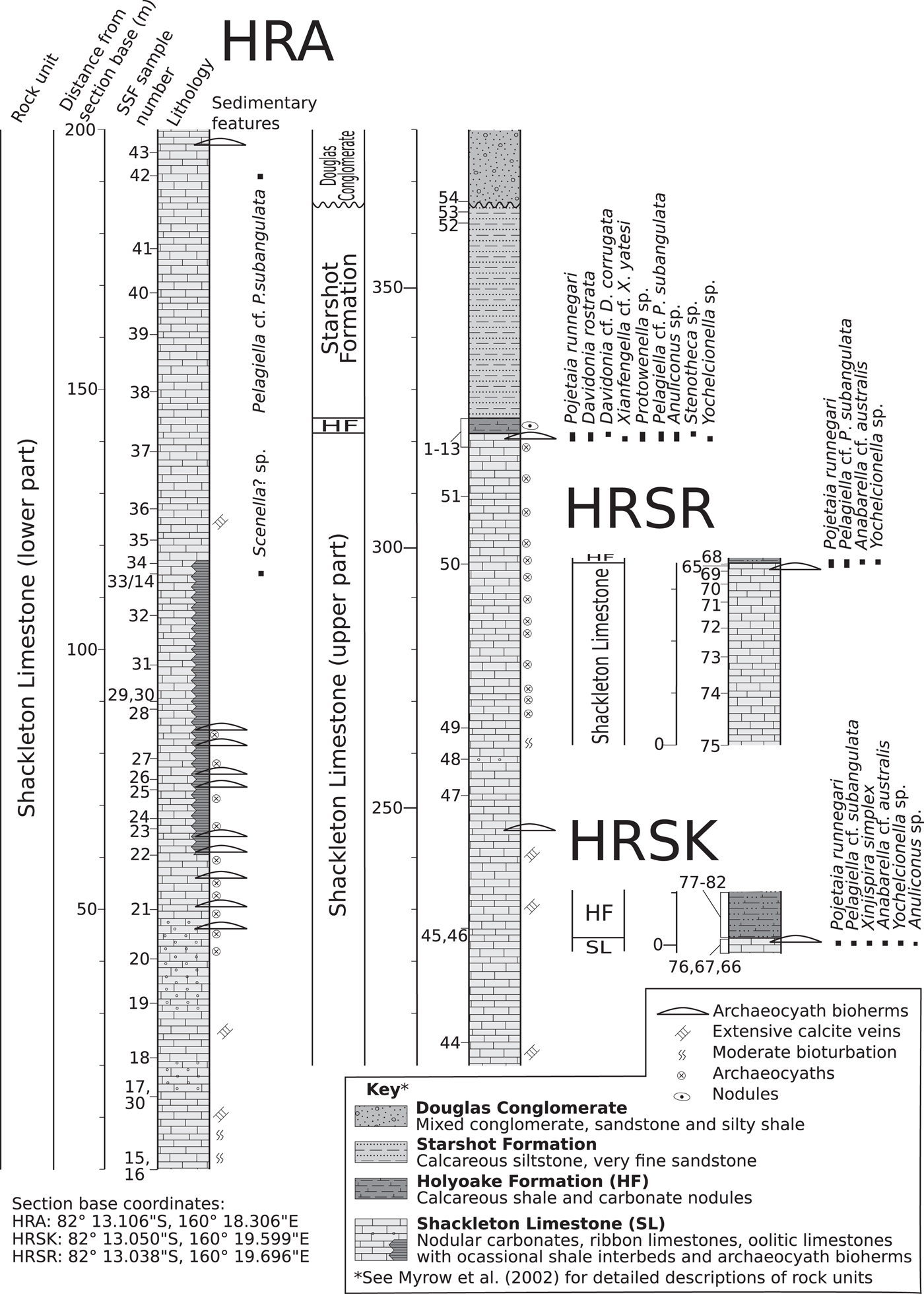

Figure 2. Sedimentary columns with micromollusk occurrences of measured sections of the Holyoake Range. HF = Holyoake Formation; SL = Shackleton Limestone.

Paleontological studies on parautochthonous lower Cambrian rocks from the Shackleton Limestone have largely focused on trilobites (Palmer and Gatehouse, Reference Palmer and Gatehouse1972; Palmer and Rowell, Reference Palmer and Rowell1995) and archaeocyaths (Debrenne and Kruse, Reference Debrenne and Kruse1986, Reference Debrenne, Kruse and Crame1989). In terms of other clades, only tommotiids (Evans and Rowell, Reference Evans and Rowell1990), the helcionelloid mollusk Marocella mira Evans, Reference Evans1992, and a single bradoriid arthropod species, Bicarinellata evansi Rode et al., Reference Rode, Lieberman and Rowell2003, have been formally described systematically. Rowell et al., (Reference Rowell, Evans and Rees1988b, figs. G, L, P, Q) also illustrated some taxa, including an elkaniid-like lingulid, Lingulella sp. and the mollusk Latouchella sp., as well as an unnamed ‘euomphalid mollusk’ but without formal description. Brachiopods, mollusks, tommotiids, and other SSFs derived from allochthonous clasts redeposited in a Miocene glacial-marine succession on King George Island, near the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, were probably originally deposited within sediments equivalent to the Shackleton Limestone (Wrona, Reference Wrona1989, Reference Wrona2003, Reference Wrona2004; Holmer et al., Reference Holmer, Popov and Wrona1996). These discoveries have formed the bulk of knowledge of lower Cambrian faunas from Antarctica and confirm strong biostratigraphic and paleobiogeographic links with South Australia (Brock et al., Reference Brock, Engelbrechtsen, Jago, Kruse, Laurie, Shergold, Shi and Sorauf2000; Betts et al., Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2016a, Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2017), Northeast Greenland (Skovsted, Reference Skovsted2004, Reference Skovsted2006b), and North China (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Steiner and Keupp2015) during Cambrian Series 2, Stages 3–4.

Stratigraphic correlation

Antarctica

Lower Cambrian limestone erratics have been recovered within early Miocene glaciomarine deposits of King George Island, north of the Antarctic Peninsula (Gaździcki and Wrona, Reference Gaździcki and Wrona1986; Wrona, Reference Wrona1989); these contain a diverse fauna of poriferan spicules and chancellorid, sachitiid, and tommotiid sclerites (Wrona, Reference Wrona2004), organophosphatic brachiopods (Holmer et al., Reference Holmer, Popov and Wrona1996), bradoriids and phosphatocopids (Wrona, Reference Wrona2009), and mollusks (Wrona, Reference Wrona2003). The molluskan fauna from the erratics is similar to the Shackleton Limestone samples recovered from the Holyoake Range, including the genera Yochelcionella Runnegar and Pojeta Reference Runnegar and Pojeta1974, Anabarella Vostokova, Reference Vostokova1962, and Pelagiella (Matthew, Reference Matthew1895) (Wrona, Reference Wrona2003). The erratics most likely belong to the Shackleton Limestone and host the age-diagnostic tommotiid Dailyatia odyssei (Evans and Rowell, Reference Evans and Rowell1990; Wrona, Reference Wrona2004; Skovsted et al., Reference Skovsted, Betts, Topper and Brock2015).

South Australia

Previous studies suggesting a link between the Shackleton Limestone and South Australia were based on relatively few in situ samples from Antarctica, particularly of SSFs (see Brock et al., Reference Brock, Engelbrechtsen, Jago, Kruse, Laurie, Shergold, Shi and Sorauf2000; Topper et al., Reference Topper, Skovsted, Brock and Paterson2011; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Steiner and Keupp2015). Biostratigraphic correlation has previously been based on trilobites (Palmer and Gatehouse, Reference Palmer and Gatehouse1972; Palmer and Rowell, Reference Palmer and Rowell1995). Palmer and Rowell (Reference Palmer and Rowell1995) tentatively assigned their six assemblages of trilobites to be from Atdabanian to Toyonian in age, and their assemblage 4 was correlated to the Pararaia janae zone of South Australia on the basis of co-occurrence of Balcoracania (Jell in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990). Paterson and Brock (Reference Paterson and Brock2007) described Yunnanocephalus macromelos from the Mernmerna Formation, indicating a link between Palmer and Rowell's (Reference Palmer and Rowell1995) Assemblage 1 (which contains members of the genus) and the Pararaia bunyenrooensis Zone. Caution was suggested in these ages due to few easily compared species (Palmer and Rowell, Reference Palmer and Rowell1995, p. 4). Debrenne and Kruse (Reference Debrenne and Kruse1986, Reference Debrenne and Kruse1989) indicated an Atdabanian–Botoman age for Antarctic archaeocyaths and considered most species to be found in common with the Wilkawillina and Ajax Limestones (Debrenne and Kruse, Reference Debrenne, Kruse and Crame1989, p. 24). Accurately correlating the Shackleton Limestone on the basis of the molluskan fauna alone is problematic due to issues already discussed with steinkern formation (Creveling et al., Reference Creveling, Knoll and Johnston2014; Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Betts and Brock2016a) and long stratigraphic ranges of helcionelloids (Landing, Reference Landing1988; Geyer and Shergold, Reference Geyer and Shergold2000; Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Brougham, Skovsted, Jago, Laurie, Betts, Topper and Brock2017; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang2017). This problem was discussed by Betts et al. (Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2017, p. 202) and Jacquet et al. (Reference Jacquet, Brougham, Skovsted, Jago, Laurie, Betts, Topper and Brock2017) in reference to the informal molluskan assemblage biozonations in Gravestock et al. (Reference Gravestock2001). A close correlation to the Dailyatia odyssei Zone in South Australia is strengthened by the shared presence of the accessory taxa Cambroclavus absonus Conway Morris in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990 (Skovsted et al., Reference Skovsted, Brock and Paterson2006, fig. 2) in the biohermal facies at the top of the Shackleton Limestone and Spinospitella coronata in the overlying Holyoake Formation, both of which co-occur in the D. odyssei Zone with accessory taxon Schizopholis (=Karathele) yorkensis (Ushatinskaya and Holmer in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001). The presence of these taxa exclude the biohermal unit from correlation with the underlying Micrina etheridgei Zone, in which the steinkerns of the mollusks Pojetaia runnegari, Pelagiella, Anabarella, and Davidonia Parkhaev, Reference Parkhaev2017b also occur (Betts et al., Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2017, figs. 3, 4, 7, 8, 12). Xianfengella, Yochelcionella, and Stenotheca are all restricted to the D. odyssei Zone in South Australia, allowing for stronger correlation (Betts et al., Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2017, figs. 5, 10, 12). Protowenella Runnegar and Jell, Reference Runnegar and Jell1976 is also known from the Cambrian Series 3 in Australia (Runnegar and Jell, Reference Runnegar and Jell1976; Brock, Reference Brock1998; Vendrasco et al., Reference Vendrasco, Porter, Kouchinsky, Li and Fernandez2010), as well as Cambrian Series 2, Stage 4 (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Brock and Paterson2015), but the utility of this taxon in correlation with South Australia is doubtful due to problems with consistent identification.

The Shackleton Limestone fauna has most similarity with the Mernmerna Formation in the Arrowie Basin, which shares the micromollusks Pojetaia runnegari, Davidonia, Pelagiella, Anabarella, Stenotheca Hicks, Reference Hicks1872, and Xianfengella He and Yang, Reference He and Yang1982 (Topper et al., Reference Topper, Brock, Skovsted and Paterson2009). The macromollusk Marocella mira not reported in this study is also present in the upper Mernmerna Formation (Topper et al., Reference Topper, Brock, Skovsted and Paterson2009; Jacquet and Brock, Reference Jacquet and Brock2016) and the Shackleton Limestone that outcrops in the Churchill Mountains (Evans, Reference Evans1992). The Ajax Limestone in the Arrowie Basin also contains Davidonia and Anabarella steinkerns as well as Pelagiella subangulata (Tate, Reference Tate1892) (Betts et al., Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2016a, fig. 2). Pojetaia runnegari has also been reported from the Ajax Limestone (Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990, fig. 6) although the range extends down into the underlying M. etheridgei Zone. The Shackleton Limestone thus strongly correlates with the D. oddysei zone in the upper Ajax Limestone (Betts et al., Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2016a, fig. 2). Yochelcionella chinensis Pei, Reference Pei1985 has also been reported from the younger Oraparinna Shale (Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990) of the Pararaia janeae Zone (Jago et al., Reference Jago, Gehling, Paterson, Brock and Zang2012).

Highly diverse assemblages of micromollusks have been reported from the lower Cambrian Stansbury Basin (Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990; Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001), many of which also occur in the Shackleton Limestone. Davidonia rostrata (Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984), Pojetaia runnegari, as well as the genera Anuliconus Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, Anabarella, Pelagiella, and Stenotheca occur in the uppermost Kulpara Formation and disconformably overlying Parara Limestone in the western Stansbury Basin (Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990; Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001), indicating long stratigraphic ranges of limited correlation potential. Xianfengella yatesi Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001 has a more restricted occurrence, in the Parara Limestone at Yorke Peninsula (Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001). Betts et al. (Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2017, fig. 22) identified the D. odyssei Zone in the Parara Limestone at Horse Gully on Yorke Peninsula. A condensed Kulparina rostrata Zone and overlying Micrina etheridgei Zone occurr in the disconformably underlying Kulpara Formation (Betts et al., Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2017, p. 202).

North China

Cambrian Series 2 strata from North China are divided into three biozones: the informal Stenotheca drepanoida-Pelagiella madianensis Biozone (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Qian and Rong1994), considered equivalent to the Pararaia janeae trilobite zone of South Australia (Yun et al., Reference Yun, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Liu2016), and the overlying Redlichia and Redlichia chinensis informal trilobite zones (Yun et al., Reference Yun, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Liu2016). Mollusks from the Cambrian Series 2, Stages 3–4, Xinji Formation in Shaanxi Province, Henan Province, and Anhui Province on the southwestern, southern, and southeastern margins of the North China Platform, respectively, can be closely correlated to the Shackleton Limestone based on shared genera Stenotheca, Pelagiella, Yochelcionella, Yu and Rong, Reference Yu and Rong1991, and Anabarella and species Xinjispira simplex, Pojetaia runnegari, and Davidonia rostrata (He et al., Reference He, Pei and Fu1984; Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984; He and Pei, Reference He and Pei1985; Pei, Reference Pei1985; Li and Zhou, Reference Li and Zhou1986; Yu and Rong, Reference Yu and Rong1991; Feng et al., Reference Feng, Qian and Rong1994; Yun et al., Reference Yun, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Liu2016). The presence of Xinjispira simplex in the Shackleton Limestone represents the first discovery of the species outside North China and helps strengthen this correlation. Putative Protowenella steinkerns are also known from the Xinji Formation (Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984). However, it should be noted that diagnostic muscle scars are not preserved on specimens from the Xinji Formation or Shackleton Limestone (and other putative pre-Series 3 specimens), making taxonomic assignment to this genus tentatative at this stage (Berg-Madsen and Peel, Reference Berg-Madsen and Peel1978; Brock, Reference Brock1998).

South China

Palmer and Rowell (Reference Palmer and Rowell1995) correlated their Trilobite Assemblage 1 (tentatively ‘Atdabanian’) to the Eoredlichia-Wutingaspis Zone of South China, which has significant overlap with the Dailyatia odyssei Zone of South Australia (Betts et al., Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2017). The Eoredlichia-Wutingaspis Zone is equivalent to the Pelagiella subangulata Zone of East Yunnan and central Sichuan in South China (Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Li, Qian, Zhu and Erdtmann2007). The uppermost Shiyantou, Yuanshan (Yunnan Province) and upper Jiulaodong (Sichuan Province) formations of this zone have no shared helcionelloids for correlation to the Shackleton Limestone. The Yuanshan Formation of East Yunnan is predominantly siliciclastic and preserves phosphatic SSFs only in the lowermost phosphatic conglomerate unit, which contains SSFs of the Sinosachites flabelliformis-Tannuolina zhangwengtangi Zone (Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Zhu, Weber and Geyer2001), immediately below the Pelagiella subangulata Zone (Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Li, Qian, Zhu and Erdtmann2007). This zone shares the taxon Xianfengella with the Shackleton Limestone only, in the Terreneuvian Yanjiahe Formation of Hubei (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Li and Li2014) and Zhujianqing Formation of Yunnan (Anabarites trusulcatus-Protohertzina anabarica to Watsonella crosbyi zones) (Parkhaev and Demidenko, Reference Parkhaev and Demidenko2010).

Laurentia

The SSF composition of eastern Laurentia suggests a continuous shelf margin during the early Cambrian (Skovsted, Reference Skovsted2006b; Skovsted and Peel, Reference Skovsted and Peel2010). Landing and Bartowski (Reference Landing and Bartowski1996) and Landing et al. (Reference Landing, Geyer and Bartowski2002) reported diverse assemblages of SSFs from the Browns Pond Formation of the Taconic Allochthon of New York (Landing and Bartowski, Reference Landing and Bartowski1996) and the ‘Anse Maranda Formation’ of Quebec (Landing et al., Reference Landing, Geyer and Bartowski2002), which contain a similar molluskan component of Davidonia rostrata, Yochelcionella, and Pelagiella. The material from the Browns Pond Formation was collected from the Elliptocephala asaphoides assemblage, recognized as part of the Bonnia-Olenellus Zone by Siveter and Williams (Reference Siveter and Williams1997). Also from Eastern Laurentia, the Forteau Formation of Newfoundland contains an abundant micromolluskan fauna (Skovsted and Peel, Reference Skovsted and Peel2007), which shares Pojetaia runnegari, Davidonia, Stenotheca, and Pelagiella with the Shackleton Limestone. The formation also belongs to the Bonnia-Olenellus Zone as both trilobite genera occur there (Schuchert and Dunbar, Reference Schuchert and Dunbar1934; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Boyce, Skovsted and Balthasar2017). Betts et al. (Reference Betts, Paterson, Jago, Jacquet, Skovsted, Topper and Brock2017) recognized an overlap between the younger Olenellus Zone (the base of which is the same as the Bonnia-Olenellus Zone; Landing et al., Reference Landing, Geyer, Brasier and Bowring2013) and the uppermost part of the Dailyatia odyssei Zone of South Australia. The Kinzers Formation of Pennsylvania, of upper Cambrian Series 2 age, also contains steinkerns of Yochelcionella and Pelagiella (Atkins and Peel, Reference Atkins and Peel2008; Skovsted and Peel, Reference Skovsted and Peel2010).

Northeast Greenland has lower Cambrian SSFs recognized as similar to those in South Australia and from the glacial erratics recovered from King George Island, Antarctica (Malinky and Skovsted, Reference Malinky and Skovsted2004; Skovsted, Reference Skovsted2004; Skovsted and Holmer, Reference Skovsted and Holmer2005; Skovsted, Reference Skovsted2006b). Skovsted (Reference Skovsted2004) reported a micromolluskan fauna from the Bastion Formation for Northeast Greenland, also correlated to the Bonnia-Olenellus Zone (Skovsted, Reference Skovsted2006b, fig. 5.1–5.3), placing them as Dyeran in age of Laurentian regional scheme (Landing et al., Reference Landing, Geyer, Brasier and Bowring2013). The micromollusk fauna of the Bastion Formation is very similar to that found in the Shackleton Limestone and shared taxa include Davidonia rostrata, Pojetaia runnegari, Anabarella, Stenotheca, and Yochelcionella, (Skovsted, Reference Skovsted2004) of which the latter four can be more loosely correlated at the generic level.

For western Laurentia, Skovsted (Reference Skovsted2006a) and Wotte and Sundberg (Reference Wotte and Sundberg2017) provided systematic descriptions of lower Cambrian micromollusks from the Great Basins area. Pelagiella and Anabarella appear widespread across the province, with Pelagiella aff. P. subangulata occurring in the Emigrant Formation, Montenegro Member of the Campito Formation and the Combined Metals Member of the Pioche Formation, in rocks of upper Montezuman to Dyeran Stages (Wotte and Sundberg, Reference Wotte and Sundberg2017) given Cambrian Series 2, Stage 3 (Montezuman) and Stages 3–4 (Dyeran) (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Babcock, Cooper, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012).

Materials and methods

Fossils were collected in the Austral summer during five weeks of fieldwork in October–November, 2011 (by LEH, CBS, GAB) from measured stratigraphic sections (HRA, HRSK, and HRSR) in the Holyoake Range, Central Transantarctic Mountains (Figs. 1, 2). The sections intersect the upper carbonate-dominated successions of the Shackleton Limestone, including inner shelf, shoal, and archaeocyath-microbialite bioherm facies, and the overlying and onlapping dark silty carbonates and argillites from the Holyoake Formation. The most diverse and abundant fossil materials are derived from well-exposed biohermal facies at the top of the Shackleton Limestone (Fig. 2). Stratigraphically, the sections are an extension of the section originally sampled and illustrated by Myrow et al. (Reference Myrow, Pope, Goodge, Fischer and Palmer2002). Phosphatic residues were extracted from the carbonate matrix with dilute 10% acetic acid solution following standard acid-leaching protocols (see Jeppsson et al., Reference Jeppsson, Anehus and Fredholm1999). Images were taken with a Zeiss Supra 35 SEM at Uppsala University, a Hitachi S-4300 SEM at the Natural History Museum, Stockholm, and a PHENOM XL Benchtop SEM at Macquarie University.

Repository and institutional abbreviation

All specimens are deposited at the Swedish Museum of Natural History (SMNH), Stockholm, Sweden.

Systematic paleontology

The phylogenetic relationships of the likely polyphyletic class Helcionelloida Peel, Reference Peel, Simonetta and Conway Morris1991a is still unresolved. Many simple, poorly preserved and minute cap-shaped steinkerns recovered from the Shackleton Limestone during this study are not dealt with here due to a lack of taxonomically informative features.

Phylum Mollusca Cuvier, Reference Cuvier1797

Class Bivalvia Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758

Order and family uncertain

Genus Pojetaia Jell, Reference Jell1980

Type species

Pojetaia runnegari Jell, Reference Jell1980, ‘Salterella Limestone,’ near Ardrossan, South Australia, by original designation. This likely corresponds to the Parara Limestone at Horse Gully, near Ardrossan, South Australia (cf. Jell, Reference Jell1980, p. 234; Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990, fig. 4).

Pojetaia runnegari Jell, Reference Jell1980

Figure 3

See Elicki and Gürsu (Reference Elicki and Gürsu2009, p. 281–282) for a detailed synonymy.

- 1980

Pojetaia runnegari Jell, p. 235, figs. 1–3.

- 2004a

Pojetaia runnegari; Parkhaev, p. 600, pl. 2, figs. 15–18.

- 2007

Pojetaia runnegari; Skovsted and Peel, p. 737, fig. 4 K, L.

- 2008

Pojetaia runnegari; Parkhaev, p. 38, fig. 3.4.

- 2009

Pojetaia runnegari; Elicki and Gürsu, p. 281, pl. 1, pl. 2, E–H.

- 2009

Pojetaia runnegari; Topper et al., p. 238, fig. 12 K–M.

- 2010

Pojetaia runnegari; Heuse et al., p. 107, fig. 2.14.

- 2011

Pojetaia runegari; Vendrasco et al., pl. 1–4.

- 2015

Pojetaia runnegari; Vinther, fig. 2H.

- 2016

Pojetaia runnegari; Yun et al., fig. 5M.

- 2017

Pojetaia runnegari; Betts et al., fig. 17O.

Figure 3. Pojetaia runnegari Jell, Reference Jell1980 from the Shackleton Limestone. (1–4) Specimen SMNH Mo185039 in (1) lateral view, (2) dorsal view, (3) magnification of the central margin, showing laminar crystalline imprints, (4) magnification of the cardinal teeth shown in (2). (5, 6) Specimen SMNH Mo185040, (5) lateral view, (6) magnification of lateral surface, showing laminar crystalline imprints. (7) Specimen SMNH Mo185041 in lateral view. (8) Specimen SMNH Mo185042 in lateral view. (9) Specimen SMNH Mo185043. (5, 6, 8) imaged under low vacuum settings. (1, 2, 6–9) Scale bars = 200 µm; (3–5) scale bars = 100 µm.

Holotype

P59669, Paleontological collections, National Museum of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia. Internal mold of articulated valves, ‘Salterella limestone,’ lower Cambrian, South Australia.

Occurrence

See Elicki and Gürsu (Reference Elicki and Gürsu2009, p. 273) for a full review of global stratigraphic distribution. Distribution now includes Cambrian unnamed Series 2, Stages 3–4, of Newfoundland, Canada (Skovsted and Peel, Reference Skovsted and Peel2007), and East Antarctica.

Description

Small equibivalved steinkerns, suboval or subcircular in outline to slightly extended caudally, range from 0.8–1.5 mm in length, 0.4–1.1 mm in height. Umbo central to subcentral and prosogyral. Shells 0.8–1.5 mm in length, 0.4–1.1 mm in height. One to two cardinal teeth on straight dorsal hinge but sometimes not preserved. Small, projecting auricle present on posterior part of the hinge. Ventral margin slightly convex, transition to anterior and posterior margins variable from distinct bend to gentle curve. Ligament or muscle scars not preserved. Prismatic imprints present on the internal mold, covering the majority of the steinkern, becoming smaller but clearer at the ventral margin.

Materials

Thirty-six steinkerns from localities HRSR 65, 68, HRSK 66, and HRA 2, 4, and 6 (Fig. 2)

Remarks

Antarctic specimens are exclusively steinkerns, which hinders comparison to specimens preserved as external molds that are used to diagnose the species (e.g., Jell, Reference Jell1980; Runnegar and Bentley, Reference Runnegar and Bentley1983; Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990; Skovsted, Reference Skovsted2004; Elicki and Gürsu, Reference Elicki and Gürsu2009). The specimens fit within the known size and morphological range for P. runnegari (see Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990, figs. 165, 166; Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, p. 201–203, pl. 49, figs. 1–13, pl. 50, figs. 1–9; Elicki and Gürsu, Reference Elicki and Gürsu2009) and have a similar distribution of foliated aragonite imprints on the steinkern surface (Fig. 3.3, 3.5; cf. Runnegar and Bentley, Reference Runnegar and Bentley1983, fig. 6A, B, E, I; Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990, fig. 165E–G; Vendrasco et al., Reference Vendrasco, Checa and Kouchinsky2011, pl. 3, 4). Compared to measured specimens, height-to-length ratios and overall size of the Antarctic specimens cover the range of values for Pojetaia and Fordilla (Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, p. 202; Elicki and Gürsu, Reference Elicki and Gürsu2009, p. 275), although measurements given are few. The specimens are assigned to P. runnegari due to lack of visible muscle scars, typical for P. runnergari (Runnegar and Bentley, Reference Runnegar and Bentley1983) and shorter caudal extension than in Fordilla, a taxon not reported from East Gondwana.

Antarctic specimens are typically missing the anterior auricle, which appears to be broken off, although the posterior auricle is occasionally present (Fig. 3.7). Judging by the variation in caudal extension, the Antarctic specimens appear to conform to Jell's (Reference Jell1980) observation that the size of the posterior auricle is variable.

‘Class Helcionelloida’ Peel, Reference Peel, Simonetta and Conway Morris1991a

Order Helcionellida Geyer, Reference Geyer1994

Family Helcionellidae Wenz, Reference Wenz1938

Genus Davidonia Parkhaev, Reference Parkhaev2017b

Type species

Davidonia davidi (Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990), by original designation (=Mellopegma rostratum Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984) from the lower Cambrian Parara Limestone, Stansbury Basin, South Australia, Dailyatia odyssei Zone.

Remarks

Steinkerns of Davidonia exhibit a range of characteristics (Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, p.175) such as bilateral symmetry and presence of rugae (Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, p. 175–176) but typically preserve microstructural polygonal imprints of tabular aragonite on their surface (Vendrasco and Checa, Reference Vendrasco and Checa2015). Cyrtoconic Davidonia rostrata is typically more recurved than others (Fig. 4.6, 4.8, 4.6, 4.12; e.g., Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 40, figs. 1–3, 5, 8, pl. 41, figs. 1, 2, 7, 8, 9). At the other end of the spectrum lies the erect, almost orthoconic Davidonia taconica (e.g., Landing and Bartowski, Reference Landing and Bartowski1996, fig. 5.5, 5.7–5.9; Skovsted, Reference Skovsted2004, fig. 3I, L). Davidonia taconica was originally included in the genus Stenotheca (Landing and Bartowski, Reference Landing and Bartowski1996) but later removed and placed in a new genus ‘Aequiconus’ (Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001). Skovsted (Reference Skovsted2004) later placed the species in Davidonia due to the prominent lateral rugae with polygonal aragonite imprints. This reassignment leaves M. taconica and another species, M. puppis Høyberget et al., Reference Høyberget, Ebbestad, Funke and Nakrem2015, from the Cambrian Stage 4 Evjevik Member of the Ringstrand Formation Norway (Høyberget et al., Reference Høyberget, Ebbestad, Funke and Nakrem2015), as outliers within the genus, as they lack a parietal train.

Davidonia rostrata (Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984)

Figure 4.6–4.14

- 1984

Mellopegma rostratum n. sp. Zhou and Xiao, p. 132, pl. 3, figs. 7–10.

- ?1984

Bemella anhuiensis n. sp. Zhou and Xiao, p. 129, pl. 1, figs. 8, 9.

- ?1984

Bemella costa n. sp. Zhou and Xiao, p. 128, pl. 1, fig. 10.

- 1990

Mackinnonia davidi n. sp. Runnegar in Bengtson et al., p. 234, figs. 159, 160 J.

- 1994

Mellopegma rostratum; Feng et al., p. 7, pl. 2, figs. 5–9.

- 1996

Mackinnonia obliqua n. sp. Landing and Bartowski, p. 754, figs. 5.10–5.16.

- 2001

Mackinnonia rostrata; Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., p. 176, pl. 40, 41.

- ?2002

Mackinnonia obliqua; Landing et al., p. 296, fig. 8.3.

- 2004

Mackinnonia rostrata; Skovsted, p. 16, fig. 3A–H.

- ?2006

Mackinnonia cf. M. rostrata; Wotte, p. 151, fig. 5 g–k.

- 2014

Mackinnonia rostrata; Parkhaev, p. 374, pl. 3, figs. 2, 3.

- 2016

Mackinnonia sp.; Jacquet and Brock, p. 340, fig. 5 H, J.

- 2016a

Mackinnonia rostrata; Betts et al., p. 196, fig. 18N–U.

Figure 4. Helcionellids from the Shackleton Limestone. (1–5) Davidonia cf. D. corrugata Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990. (1–3) Specimen SMNH Mo185044 in (1) oblique lateral view, (2) apical view, (3) magnification of apical region in lateral view, showing protoconch and transition to teleoconch; (4) specimen SMNH Mo185045, oblique view of supra-apical field; (5) specimen SMNH Mo185046 lateral view. (6–14) Davidonia rostrata (Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984), (6, 7) specimen SMNH Mo185047, (6) lateral view, (7) dorsal view of supra-apical field; (8–11) specimen SMNH Mo185048, (8) magnification of lateral view of parietal train, showing polygonal crystalline imprints on the side surface, (9) dorsal view of supra-apical field, (10) lateral view, (11) magnification of oblique lateral view of supra-apical field, showing polygonal crystalline imprints; (12) specimen SMNH Mo182501 in lateral view; (13) specimen SMNH Mo182502 in lateral view; (14) specimen SMNH Mo182503 in lateral view. (15–18) Xianfengella cf. X. yatesi Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, specimen SMNH Mo185049, (15) dorsal view, (16) oblique apical view, (17) magnified view of supra-apical field showing crystalline imprints, (18) oblique lateral view. (19–21) Protowenella? sp. Runnegar and Jell, Reference Runnegar and Jell1976 specimen SMNH Mo185050, (19) lateral view, (20) dorsal view, (21) apical view. (22–28) Anuliconus sp. Parkhaev in Gravestock et al. (Reference Gravestock2001), (22–24) specimen SMNH Mo185051, (23) lateral view, (22) magnification of apex in lateral view, (24) apertural view; (25, 26) specimen SMNH Mo185052, (25) lateral view, (26) apical view; (27, 28) specimen SMNH Mo185053, (27) lateral view, (28) apical view. (3, 10, 11, 17, 22, 24) Scale bars = 100 µm; all others, scale bars = 200 µm.

Holotype

No. 800059, Geological Institute, Anhui Province, People's Republic of China. Internal mold from the Xinji (=Yutaishan) Formation of the lower Cambrian of Anhui Province, China.

Occurrence

Cambrian, Stage 2 and Series 2, Stages 3–4 Dailyatia odyssei Zone of South Australia, Cambrian Series 2 Stages 3–4 of North China, Northeast Greenland, Taconic Allochthon of New York, USA, Quebec, Canada, and East Antarctica. Potentially Cambrian Stage 5 of northwestern Spain.

Description

Moderately high, cyrtoconic steinkerns, coiled through one-third of a whorl and moderately laterally compressed. Range 0.5–1.3 mm in length, 0.2–0.8 mm in height (see Table 1), and approximately 1.5 times longer than high. Protoconch reclined, rounded, rapidly expanding, and distinct from the teleoconch by change in microstructural imprints from smooth to polygonal. Strongly hooked apex directly above the parietal train or displaced up to one-quarter the length of the steinkern beyond the parietal train. Supra-apical field evenly convex, subapical field short and concave; moderate rate of expansion. Apertural outline elongated elliptical, sometimes with short rounded parietal train separated by a distinct indent from the subapical field. Rounded parietal train tilts upward at an angle. In lateral view the aperture exhibits a convex profile. Transverse rugae subdued, not present on all Antarctic material but terminate before subapical field when present. Some small juvenile specimens lack rugae. Polygonal microstructural imprints (9–12 µm wide) are exhibited on the surface of the co-marginal rugae, with smooth furrows. The parietal train has pitted depressions on the steinkern surface (3–5 µm wide), and the protoconchs are smooth.

Table 1. Height and length measurements of selected specimens of Davidonia rostrata (Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984).

Materials

ca. 100 steinkerns of varying size and quality of preservation from HRA 2, 4–6.

Remarks

Specimens identified as Davidonia rostrata from the Shackleton Limestone range in size and shape (see Table 1), lending support to the concept that this is a morphologically variable species (Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001). This morphological variation is interpreted to reflect ontogenetic, taphonomic, and potential intraspecific variation in this taxon group. Significant variation in the shape of the protoconch between biogeographically distinct assemblages of this species indicate they were morphologically distinct from an early ontogenetic stage, although qualitatively identical at later stages (Jackson and Claybourn, Reference Jackson and Claybourn2018). Smaller specimens (e.g., Fig. 4.13: ~0.6 mm in length, 0.3 mm in height) resemble a similarly recurved helcionellid, Figurina nana (Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984), which can otherwise be readily distinguished from D. rostrata by the lack of distinct rugae, a transverse depression above the aperture, and circular protoconch. Some of the specimens (e.g., Fig. 4.13) from the Shackleton Limestone where the rugae are absent are considered juveniles of D. rostrata due to their smaller size compared to figured specimens of F. nana (Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984, pl. 3, fig. 11a; Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 35, figs. 4–8) and shared microstructure with other D. rostrata specimens from the Shackleton Limestone (Fig. 4.10, 4.11). A similar pattern was recognized among Australian specimens by Parkhaev in Gravestock et al. (Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 41, fig. 11).

Figured specimens of Davidonia rostrata from the Xinji Formation of the North China platform (Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984, pl. 1, figs. 8–10, pl. 2, figs. 1–10; Feng et al., Reference Feng, Qian and Rong1994 pl. 2, figs. 5–8) are typically tall, strongly recurved examples of Davidonia rostrata with prominent rugae and with weakly developed parietal trains. Exceptions are two specimens figured by Zhou and Xiao (Reference Zhou and Xiao1984, pl. 1, figs. 8, 9), which are longer than high, are more recurved, and lack parietal trains. The loss of the train is probably due to an incomplete formation of the steinkern, as the rugae are truncated at the base. This morphological variability in height is also reflected in Antarctic specimens, with moderate (Fig. 4.6, 4.12) and low specimens (Fig. 4.8, 4.14) occurring together, but with identical rugae, microstructural imprints, and parietal train.

A wide range of morphologies is figured in Gravestock et al. (Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 40, 41) from the Parara Limestone (Stansbury Basin, Cambrian Series 2, Stages 3–4), Sellick Hill Formation (Stansbury Basin, Terreneuvian, Stage 2), and the Mernmerna Formation (Arrowie Basin, Cambrian Series 2, Stages 3–4), South Australia. Larger specimens have more prominent rugae than those from the Shackleton Limestone (Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 40, figs. 1–3, 5a, 8, pl. 40, figs. 1–7, 9), and smaller specimens tend to lack (Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 41, fig. 11) or have subdued rugae (Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 41, figs. 6, 10). This probably reflects the ontogeny of Davidonia rostrata, with shell thickenings (preserved as rugae observed on steinkerns) only developing later in their ontogeny. This distribution is comparable to some smaller D. rostrata specimens (Fig. 4.13). Another feature that only appears to occur on larger specimens is the development of a sinus on the parietal train (Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 40, figs. 4, 6). Compared to specimens from the Shackleton Limestone, Australian specimens generally have a larger maximum size, with more prominent rugae, but share the same strong recurvature and microstructure. Runnegar in Bengtson et al. (Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990) figured specimens (fig. 159 A–H) from the Parara Limestone and the upper part of the Ajax Limestone (Cambrian Series 2, Stages 3–4), also in South Australia. These share a common morphology with other specimens figured in Gravestock et al. (Reference Gravestock2001), as well as having a transverse thickening on the subapical field (Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990, fig. 159A, B), a feature that is lacking in Antarctic specimens.

Skovsted (Reference Skovsted2004, fig. 3A, B, F) described Davidonia rostrata from the Bastion Formation (unnamed Cambrian Series 2, Stages 3–4) of northeast Greenland, which consists of specimens with lower profiles, more subdued rugae, and parietal trains that lack sinuses (Skovsted, Reference Skovsted2004, fig. 3G, C). Both characteristics are more similar to specimens from the Shackleton limestone (e.g., Fig. 4.6, 4.8, 4.14,). Included in Skovsted's (Reference Skovsted2004) synonymy of Davidonia rostrata was ‘Mackinnonia sp.’ (Kouchinsky, Reference Kouchinsky2000, fig. 10) from Siberia, which was reassigned to Davidonia anabarica Parkhaev, Reference Parkhaev2005. Although similar to D. rostrata in its overall morphology, the steinkerns of D. anabarica show prominent transverse tubercles, clearly distinguishing it from D. rostrata (Kouchinsky, Reference Kouchinsky2000, fig. 10 E; Parkhaev, Reference Parkhaev2005, pl. 2, fig. 2E).

‘Mackinnonia cf. M. rostrata’ from the Leonian (Cambrian Stage 5) Láncara Formation of northern Spain (Wotte, Reference Wotte2006) is only tentatively included in the synonymy list, due to the poor preservation and younger stratigraphic age compared to D. rostrata sensu stricto. The synonymization by Parkhaev (in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001) of Bemella anhuiensis Zhou and Xiao Reference Zhou and Xiao1984 and B. costa with Davidonia rostrata have been followed here, but with some uncertainty due to the low clarity of the images available from the original descriptions by Zhou and Xiao (Reference Zhou and Xiao1984). Kouchinsky et al. (Reference Kouchinsky, Bengtson, Clausen and Vendrasco2015, p. 430) expressed doubt in the synonymy of Davidonia davidi with D. rostrata due to D. davidi having a higher profile, greater degree of coiling, and more-prominent rugae on the steinkerns. Material from the Shackleton Limestone have examples that have both moderate profiles and subdued rugae (Fig. 4.6, 4.12), indicating these characteristics alone are not sufficient to distinguish the two species. This leaves the prominence of rugae alone to distinguish the two, which might be ontogenetic, ecophenotypic, or influenced by taphonomic processes of replication of the shell and shell interior of micromollusks by calcium phosphate (Creveling et al., Reference Creveling, Knoll and Johnston2014).

Davidonia cf. D. corrugata (Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990)

Figure 4.1–4.5

See Supplementary file 1 for taxa assigned to Davidonia corrugata

Holotype

‘Lepostega? corrugata’ Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990, SAMP29006, Cambrian Stage 3 Parara Limestone, Carramulka, South Australia.

Occurrences

Davidonia corrugata occurs in the Cambrian Stages 3–4 Dailyatia odyssei Zone in South Australia.

Description

High cyrtoconic, erect steinkerns with hooked apex, moderately laterally compressed, apex displaced beyond subapical margin. Steinkerns 0.5–0.6 mm in length and 0.5–0.6 mm in height. Protoconch smooth, small, and pinched, distinct from teleoconch, which expands more rapidly. Supra-apical field convex, subapical field gently concave, moderate rate of expansion. Aperture elliptical to subquadrate. Transverse rugae broad, flat, and subrectangular in profile with reduced width of furrows. Rugae encircle the teleoconch and preserve surficial polygonal imprints, which extend to the uppermost parts of the furrows. Lower parts of the furrows and protoconch are smooth. Parietal train not present in any recovered specimens.

Materials

Five steinkerns from locality HRA6.

Remarks

Davidonia corrugata was synonymized with Davidonia plicata (=Isitella plicata Missarzhevsky, Reference Missarzhevsky1989) without detailed explanation (Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, p. 178) and only a brief discussion in a later publication (Parkhaev Reference Parkhaev2005, p. 618). We follow Skovsted (Reference Skovsted2004, p. 15) and refer the specimens to Davidonia cf. D. corrugata (Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990).

Compared to specimens of Davidonia rostrata from the Shackleton Limestone, these specimens are far less recurved and have more prominent rugae. The lack of a parietal train and less recurved form are similar to D. taconica from Northeast Greenland (Skovsted, Reference Skovsted2004, p. 17–18, figs. 3I–R, 4), but the greater recurvature and more prominent rugae are sufficient to distinguish the two. Davidonia puppis Høyberget et al., Reference Høyberget, Ebbestad, Funke and Nakrem2015 is similar to Davidonia cf. D. corrugata but is much larger in size, up to 6.5 mm in length (Høyberget et al., Reference Høyberget, Ebbestad, Funke and Nakrem2015, p. 49), and has a less recurved apex (Høyberget et al., Reference Høyberget, Ebbestad, Funke and Nakrem2015, fig. 16, A–J).

Specimens from South Australia show different rates of expansion from the apex: from rapidly expanding with a short protoconch (Runnegar in Bengtson, Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990, p. 237, fig. 160A–G; Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, p. 296, pl. 39, figs. 6–12) to morphologies with a narrow, elongate protoconch (Topper et al., Reference Topper, Brock, Skovsted and Paterson2009, p. 226, fig. 9A–H). The specimens are referred to Davidonia cf. D. corrugata due to their broad, prominent rugae (Fig. 4.5) and upright suborthoconic profile (Fig. 4.1, 4.4, 4.5), which are most similar to those figured by Topper et al. (Reference Topper, Brock, Skovsted and Paterson2009, fig. 9A–H). A more certain assignment to a species is precluded by lack of information on the aperture and low number of specimens. The broad rugae, narrow furrows, and high profile also differentiate the specimens from Davidonia rostrata, which is characterized by narrower and less prominent rugae and a protoconch that is broader and more rounded. Davidonia taconica can also be readily distinguished from D. cf. D. corrugata by having a more upright form, broader protoconch, and reduced bilateral compression (cf. Skovsted, Reference Skovsted2004, fig. 3I–R). The specimens of D. corrugata from the Mermerna Formation, South Australia, have the same pinched protoconch as the Shackleton Limestone specimens (cf. Fig. 4.1–4.3 with Topper et al., Reference Topper, Brock, Skovsted and Paterson2009, pl. 9, fig. H), while specimens from the Parara Limestone (Stansbury Basin) and Oraparinna Shale (Arrowie Basin) have broad, more spoon-shaped protoconchs in outline, leading to a more regular rate of whorl expansion (Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990, fig. 160A–F; Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 39, figs. 4, 6b). The Shackleton Limestone specimens also lack a parietal train, unlike specimens from South Australia (Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 38, fig. 7, pl. 39, figs. 2, 3, 7), although this is likely taphonomic due to incomplete steinkern formation.

Genus Xianfengella He and Yang, Reference He and Yang1982

Type species

Xianfengella prima He and Yang, Reference He and Yang1982 by original designation, from the lower Cambrian Zhongyicun Member of the Meishucun Formation, Yunnan Province, China.

Xianfengella cf. X. yatesi Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001

Figure 4.15–4.18

See Supplementary file 1 for taxa assigned to Xianfengella yatesi.

Holotype

PIN 4664/1506, Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia. Steinkern from the Parara Limestone, Horse Gully, Yorke Peninsula, South Australia, Dailyatia odyssei Zone.

Occurrence

Xianfengella yatesi is known from Cambrian Stages 3–4 Dailyatia odyssei Zone of South Australia. Possibly known from Northeast Greenland and East Antarctica.

Description

Low, cap-shaped steinkern, recurved to approximately one-third of a whorl, apex recurved, displaced beyond the aperture. Single specimen approximately 0.6 mm wide, 0.6 mm high, and 0.9 mm long: two-thirds as wide as it is long. Apex narrow, expands rapidly after first 200 µm, with no distinction between protoconch and teleoconch. Lateral fields and supra-apical field strongly convex. Subapical field short and concave with pegma-like brim at base. Ovoid apertural outline, tapered to the apex, rounded to the base of the supra-apical field. Radial rugae extend from near the apex to the aperture. Polygonal imprints present on entire steinkern surface 13–18 µm wide.

Materials

Single well-preserved steinkern from HRA 4.

Remarks

Xianfengella has been included within the helcionelloids despite previous comparisons to the cap-like terminations in halkieriids as well as Ocruranus-like fossils (Peel and Skovsted, Reference Peel and Skovsted2005). The polygonal imprints on the steinkern of this specimen (Fig. 4.17) resemble the polygonal aragonite imprints found on other helcionelloids (e.g., Vendrasco et al., Reference Vendrasco, Porter, Kouchinsky, Li and Fernandez2010, p. 1, figs. 4, 5; Vendrasco and Checa, Reference Vendrasco and Checa2015, figs. 2A–D) rather than the layered fibrous bundles that characterize Ocruranus (Vendrasco et al., Reference Vendrasco, Li, Porter and Fernandez2009, pl. 1). The Antarctic specimens differ from those figured from South Australia (Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 34). Diamond-shaped depressions and smooth ridges were reported, but not clearly figured, on the surfaces of the South Australian steinkerns (Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001), which may correspond to the polygonal imprints and longitudinal ridges on the Antarctic specimen. Other features are more easily compared, such as a notch at the subapical margin of the aperture (compare Fig. 4.16 with Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 34. figs. 6b, 8a, 8b; Topper et al., Reference Topper, Brock, Skovsted and Paterson2009, fig. 10J) and strongly recurved and posteriorly displaced apex (Fig. 4.16, 4.18; Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 34, figs. 1, 6a, 8b; Topper et al., Reference Topper, Brock, Skovsted and Paterson2009, fig. 10J). Unfortunately, the aperture and some of the subapical field are both obscured by clastic material in this specimen, making this feature difficult to decipher for closer comparison to X. yatesi from South Australia.

The specimen appears most similar to Xianfengella? cf. X. yatesi from the Bastion Formation, Northeast Greenland (Peel and Skovsted, Reference Peel and Skovsted2005) in terms of the polygonal microstructure on the steinkern exterior (Peel and Skovsted, Reference Peel and Skovsted2005, fig. 5P) and radial ridges (fig. 5 F). Both the Antarctic and Northeast Greenland specimens preserve a brim at the subapical part of the aperture (Fig. 4.16; Peel and Skovsted, Reference Peel and Skovsted2005, fig. 5A–G, J), which is not present on South Australian specimens (cf. short parietal train of Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 34, figs. 1, 2, 8a). For this reason and the fact that only a single specimen has been recovered from the Shackleton Limestone, a cautious taxonomic approach is taken, and we refer this specimen to Xianfengella cf. X. yatesi.

Genus Anuliconus Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001

Type species

Anuliconus magnificus, Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001 by original designation from Kulpara Formation (Cambrian Stages 2–3) and Parara Limestone (Cambrian Stages 3–4) in the Stansbury Basin and Mernmerna Formation (Cambrian Stages 3–4) in the Arrowie Basin, South Australia.

Anuliconus sp.

Figure 4.22–4.28

Description

High cyrtoconic and moderately bilaterally compressed steinkerns with lateral fields concave at the apex transitioning to flat on the teleoconch. Apex gently recurved over subapical field. Specimens approximately 0.4–0.5 mm wide, 0.5–0.7 mm long, and 0.7–0.9 mm high. Protoconch elongated to knob-like, separated from the teleoconch by a distinct pinching. Supra-apical surface gently convex, subapical surface moderately concave, low to moderate rate of expansion. Apertural outline varies from elliptical to subcircular. Regular, rounded, concentric rugae encircle teleoconch.

Materials

Thirty-three steinkerns from HRSK 66, HRA 2, 6.

Remarks

The Antarctic specimens generally fall within the documented intraspecific variation of the genus based on the original description of Anuliconus (Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, p. 142, pl. 25, figs. 8–17). The steinkerns are moderately bilaterally compressed, gently recurved with a concave subapical field and a convex supra-apical field, with a displacement of the apex over the subapical field and concentric rugae. It is possible the specimens from the Shackleton Limestone represent more than one species due to variations in these features, such as having more subdued (Fig. 4.27) to more prominent (Fig. 4.23, 4.24) rugae and a more (Fig. 4.27) or less (Fig. 4.23) concave subapical field, but these differences alone are insufficient for species distinction. Most of the collection have irregular apertural outlines (Fig. 4.26) or rugae truncated at the aperture (Fig. 4.23, 4.24, 4.25), indicating incomplete steinkerns (‘teilsteinkerns’ sensu Dattilo et al., Reference Dattilo, Freeman, Peters, Heimbrock, Deline, Martin, Kallmeyer, Reeder and Argast2016). Anuliconus sp. are easily distinguished from the similarly shaped Obtusoconus Yu, Reference Yu1979 by having a protoconch recurving over the subapical field.

Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., (Reference Gravestock2001) named three new species from Cambrian Series 2 sediments of South Australia, of which Anuliconus magnificus Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., (Reference Gravestock2001, p. 141) and Anuliconus truncatus Parkhaev in Gravestock et al. (Reference Gravestock2001, p. 144) bear some similarities to specimens from the Shackleton Limestone. Anuliconus magnificus shares a similar profile to taller Antarctic specimens (compare Fig. 4.23 with Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 24, figs. 8–17) and rounded triangular ribs (Fig. 4.25), and the more irregular, subdued ribs on some specimens (Fig. 4.27, Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 25, figs. 8–15) are similar to A. truncatus (Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 26, fig. 1–4).

Genus Protowenella Runnegar and Jell, Reference Runnegar and Jell1976

Type species

Protowenella flemingi Runnegar and Jell, Reference Runnegar and Jell1976 by original designation from the Cambrian Series 5 Currant Bush Limestone, Locality L128, Queensland, Australia.

Protowenella? sp.

Figure 4.19–4.21

Description

Planispiral, open-coiled steinkern coiling through three-quarters of a whorl, apex displaced beyond subcircular apertural margin. Height ~0.9 mm and total length ~1.5 mm. Protoconch slender and elongate with no clear distinction from the teleoconch. Supra-apical field strongly convex; shell exhibits gradual expansion to half a whorl, followed by more rapid expansion of the rest of the teleoconch. Aperture outline subcircular to ovoid, tapering toward apex. Sinus or umbilicus absent.

Materials

Four poorly preserved steinkerns from HRA 2, 5, 6.

Remarks

These globose planispiral steinkerns recovered from the Shackleton Limestone are included in the genus Protowenella, but only tentatively due to their poor preservation and low number. The specimens from the Shackleton Limestone have the general morphological features of the genus, such as planispiral, involute profile (Fig. 4.19–4.21), overall globose appearance, and they lack an apertural sinus (Runnegar and Jell, Reference Runnegar and Jell1976, p. 133). The specimens do not have the important circumbilical channels figured but not included in the original diagnosis (Runnegar and Jell, Reference Runnegar and Jell1976, fig. 6E; see also Brock, Reference Brock1998) and described in the revised diagnosis (Berg-Madsen and Peel, Reference Berg-Madsen and Peel1978, p. 118). The Antarctic specimens are more tightly coiled (Fig. 4.19) than Protowenella cobbensis Mackinnon, Reference Mackinnon1985 (fig. 9G), so they can be more closely compared to the more openly coiled type species Protowenella flemingi Runnegar and Jell, Reference Runnegar and Jell1976 (fig. 6). The only other Cambrian Series 2 species that have been described are from the Xinji Formation of South China: Protowenella primaria Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984 and Protowenella huainanensis Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984. P. primaria figured from the Xinji Formation is typically planispiral, but some specimens might demonstrate slight asymmetry (e.g., Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984, pl. 3, fig. 19a, b, pl. 4, figs. 4b, 5b). They also do not coil as tightly as the Shackleton Limestone specimens, and they have a broad umbilicus. This asymmetry seems to be more pronounced in P. huiananensis (Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao1984, pl. 3, figs. 18b, 19b). These specimens also appear to lack circumbilical channels (Zhou and Xiao, pl. 3, figs. 18–20, pl. 4, figs. 1–5). The lack of circumbilical channels in specimens described as Protowenella indicate they may not have the necessary features to be included in the genus (Berg-Madsen and Peel, Reference Berg-Madsen and Peel1978), an issue discussed by Brock (Reference Brock1998), who pointed out another species, P. plena Missarzhevsky and Mambetov, Reference Missarzhevsky and Mambetov1981, may also be excluded on the same basis. The only specimen of Protowenella that can be confidently assigned to the genus from Cambrian Series 2 rocks is Protowenella sp. from the Cambrian Series 2, Stage 4, Tempe Formation from the Northern Territory, Australia, on the basis of well-preserved muscle scars (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Brock and Paterson2015, fig. 6H).

With these factors in mind, the specimens from the Shackleton Limestone have only been tentatively included in Protowenella, with the caveat that if better-preserved specimens are discovered that entirely lack circumbilical channels, they should be removed from the genus (Brock, Reference Brock1998). A full redescription of all Protowenella specimens is necessary to resolve these problems. The degree of expansion and elongation of the apex is similar to figured specimens of Protowenella sp. from the middle Cambrian of Siberia (Gubanov et al., Reference Gubanov, Kouchinsky, Peel and Bengtson2004, fig. 10). Another planispiral, Protowenella-like univalved mollusk from Shackleton Limestone has been figured but not described (Rowell et al., Reference Rowell, Evans and Rees1988b, pl. 1, figs. O, P) and is referred to only as a ‘euomphalid mollusk.’

Family Yochelcionellidae Runnegar and Jell, Reference Runnegar and Jell1976

Genus Yochelcionella Runnegar and Pojeta, Reference Runnegar and Pojeta1974

Type species

Yochelcionella cyrano Runnegar and Pojeta, Reference Runnegar and Pojeta1974 by original designation, Cambrian Series 3, ‘first discovery limestone’ Member of the Coonigan Formation, New South Wales, Australia.

Yochelcionella sp.

Figure 6.1–6.8

Description

Cyrtoconic, moderately bilaterally compressed steinkerns with cylindrical subapical extension or cross section of shell forming a snorkel. Apex positioned above commencement of snorkel in lateral view. Protoconch rounded with distinctive pinching marking transition between protoconch and teleoconch; one specimen with faint polygonal imprints (Fig. 2). Subapical field short and concave, supra-apical field evenly convex. Elongate oval aperture broken in both specimens. Faint transverse rugae present between protoconch and snorkel. Irregular pitted microstructural imprints in surface of the teleoconch steinkern, 2–5 µm wide.

Materials

Five steinkerns from HRSK 66, HRSR 68, and HRA 2.

Remarks

Although the specimens are damaged, they appear most similar to Yochelcionella chinensis Pei, Reference Pei1985 as both specimens show displacement of the apical part of the shell above the snorkel away from the subapical field (Pei, Reference Pei1985, fig. 1a). Specimens from the Shackleton Limestone have rounded, rapidly expanding protoconchs with a distinctive pinch at the transition to the teleoconch (Fig. 6.1, 6.2). The specimens can be distinguished from Y. gracilis Atkins and Peel, Reference Atkins and Peel2004 from the Henson Gletscher Formation (Cambrian Stages 2–3) of North Greenland by their convex supra-apical field, where Y. gracilis has a concave supra-apical field (Atkins and Peel, Reference Atkins and Peel2004, fig. 3A, F). Yochelcionella greenlandica Atkins and Peel, Reference Atkins and Peel2004 from the Aftenstjernesø Formation (Cambrian Stage 2) of North Greenland has a similar displacement in the subapical field below the snorkel (Atkins and Peel, Reference Atkins and Peel2004, fig. 2B, D, L, N) but has well-developed rugae, which are fewer in number and much larger than Yochelcionella sp. from the Shackleton Limestone (Fig. 6.2, 6.5–6.8; see Atkins and Peel, Reference Atkins and Peel2004, fig. 2A, F, J). Specimens of Y. crassa Esakova and Zhegallo, Reference Esakova and Zhegallo1996 from the Bystraya Formation (Siberian Botoman Stage), Eastern Transbaikalia, figured by Parkhaev (Reference Parkhaev2014, pl. 1, figs. 15–18), show a similar strongly concave subapical field and highly reduced rugae, but the Shackleton Limestone specimens are not well preserved enough to draw closer comparisons. The rounded protoconch, pinching, fine rugae, and displacement are also present in Yochelcionella cf. Y. chinensis from the Forteau Formation (Cambrian Series 2, Stages 3–4), Newfoundland (Skovsted and Peel, Reference Skovsted and Peel2007, fig. 4D). Specimens preserve a pitted microstructure on the steinkern exteriors of the teleoconchs (Fig. 6.5, 6.6). Microstructure preserved on steinkerns of Yochelcionella has been reported previously. Vendrasco et al. (Reference Vendrasco, Porter, Kouchinsky, Li and Fernandez2010) described laminar and polygonal microstructures (pl. 6) on Y. saginata Vendrasco et al., Reference Vendrasco, Porter, Kouchinsky, Li and Fernandez2010 and Y. snorkorum Vendrasco et al., Reference Vendrasco, Porter, Kouchinsky, Li and Fernandez2010, inverted relative to those seen on other micromullusks (i.e., the polygon is raised and the walls between them are depressed) from the Drumian Gowers Formation from the Geogina Basin in Queensland, Australia. Kouchinsky (Reference Kouchinsky2000) described Yochelcionella sp. from the lower Cambrian of Siberia that preserved both polygons (with normal relief) and tubercles at the apex (Kouchinsky, Reference Kouchinsky2000, fig. 9). These five microstructural types, laminar, inverted polygons, normal polygons, tubercles, and now pits, on a single genus of helcionelloid represents a wide range of strategies for biomineralization.

Wrona (Reference Wrona2003) reported a single specimen of Yochelcionella? sp. from glacial erratics of King George Island, West Antarctica. The specimen is poorly preserved, with no information on the teleoconch below the snorkel (Wrona, Reference Wrona2003, fig. 13A1). The apex has a similar rounded shape to the Shackleton Limestone specimens (Fig. 6.1, 6.7, 6.8; Wrona, Reference Wrona2003, fig. 13A1).

Family Stenothecidae Runnegar and Jell, Reference Runnegar and Jell1980

Genus Stenotheca Hicks, Reference Hicks1872

Type species

Stenotheca cornucopia Salter in Hicks, Reference Hicks1872 by original designation, lower Cambrian, Pembrokeshire, Wales. The type specimen was reported lost while on loan from the Sedgwick Museum, Cambridge (Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990).

Stenotheca sp.

Figure 6.9–6.16, 6.19–6.21

Description

Bilaterally compressed steinkern, coiled to one-quarter of a whorl. Hooked apex, with entire protoconch displaced beyond subapical margin. Apertural length 0.3–0.5 mm, total height 0.35–0.55 mm. Distinct pinching at termination of protoconch, which is knob-like, elongated, and straight. Supra-apical field convex and almost flat from apex to mid-shell length. Subapical field short and concave. Lateral fields almost flat. Apertural outline elliptical in outline. Smooth regular transverse rugae present encircling teleoconch. Partial preservation of pseudomorphic phosphatic coating shows transverse ribs with more relief, closely packed nearer to the aperture (furrows 6–9 µm wide) and more widely spaced toward the apex (furrows 13–23 µm wide) (Fig. 6.14).

Materials

Approximately 12 steinkerns from HRA 6.

Remarks

These specimens are assigned to Stenotheca due to their strong bilateral compression and recurvature (Fig. 6.9–6.16, 6.19–6.21). Most specimens retain transverse rugae on the exterior of the steinkern teleoconch (Fig. 6.8, 6.9) and, in one specimen, part of the external mold with lirae (Fig. 6.14). These features are present on Stenotheca cf. S. drepanoida from the Parara and Ajax limestones from South Australia (Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990, fig. 163B–E). The recurved morphology and bilateral compression are similar to other figured specimens of Stenotheca drepanoida (He and Ting in He et al., Reference He, Pei and Fu1984) from the Xinji Formation (He et al., Reference He, Pei and Fu1984, pl. 2, figs. 1–5; Feng et al., Reference Feng, Qian and Rong1994, pl. 3, figs. 3, 6) of North China. The morphology of Stenotheca sp. is similar to the apical parts of S. drepanoida in having strong bilateral symmetry and recurvature (Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 43, figs. 1–6) and an egg-shaped protoconch, with a pinch at the transition to the teleoconch (Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990, fig. 163G; Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, pl. 43, figs. 8, 9). This feature is not present on all specimens assigned to S. drepanoida; specimens from the Mernmerna Formation of South Australia have a slender, slowly expanding apex without a clear transition to the teleoconch (Topper et al., Reference Topper, Brock, Skovsted and Paterson2009, fig. 10B–D). Stenotheca transbaikalica Parkhaev, Reference Parkhaev2004a also has a similar apical part of the shell, with a straightened, more elongate protoconch at an angle to the teleoconch on the subapical field (Parkhaev, Reference Parkhaev2004a, pl. 2, fig. 3).

Missing from the Shackleton Limestone specimens is information on the aperture. For this reason, Stenotheca sp. has been left in open nomenclature. This may be a taphonomic loss of information potentially due to steinkern-type preservation partially forming molds within quickly dissolving aragonitic shells (i.e., teilsteinkerns). Evidence for this can be seen in the truncation of the rugae at the apertural margin of the specimens (Fig. 6.10, 6.19–6.21) and the relatively small size when compared to specimens from other regions (cf. Parkhaev in Gravestock et al., Reference Gravestock2001, p. 183).

Genus Anabarella Vostokova, Reference Vostokova1962

Type species

Anabarella plana Vostokova Reference Vostokova1962 by original designation, Nemakit-Daldynian–Tommotian Stages, Siberia, Russia.

Anabarella cf. A. australis Runnegar in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990

Figure 6.17, 6.18, 6.22