Numerous psychologists have recently emphasised the importance of developing positive psychological traits. How people positively apprehend their experiences and construct meaning in life has been discussed in the context of Western culture (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi2000; Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, Reference Steger, Frazier, Oishi and Kaler2006). Finding meaning in life increases a person's confidence, ability to cope with stress, and happiness (Chaudhry, Reference Chaudhry2008). Kronman (Reference Kronman2007) stated that people construct distinct meanings in life based on their backgrounds, including their endowments, life stages, and cultural environments. However, few studies have described how young people in Eastern culture, which focuses on collectivism, find and conceptualise meaning in life during their time in college (Zhang, Dik, Wei, & Zhang, Reference Zhang, Dik, Wei and Zhang2014). College years constitute a critical time for reflecting, creating, examining, and reconstructing meaning in life, but a substantial amount of evidence has indicated that students are bored, or merely driven by courses and credentials, and do not reflect on life experiences to find meaning in life (Damon, Reference Damon2008; Kronman, Reference Kronman2007; Nash & Murray, Reference Nash and Murray2009). Therefore, this study provides insight into how college social service learning centres, professors, college students, and elementary school teachers in a community can work and learn together in a social service program in an East Asian society. We used the social group via internet platform (SGIP) in Taipei, Taiwan as an example, and describe how the top-down style of action research (Kemmis, Reference Kemmis and McTaggart1988) is effective for people to find life meaning in a college campus. We reflect on the action research process and participants’ experiences, which empowered the participants and facilitated future development of the SGIP for college students.

Meaning in Life in the West

Various definitions of meaning in life have been provided by Western researchers. Specifically, these researchers have proposed that meaning in life is derived from a person's reflections of daily life experiences (Crumbaugh & Maholick, Reference Crumbaugh and Maholick1964), from life coherence and connected events (Reker & Wong, Reference Reker, Wong, Birren and Bengston1988), and from a person's goals and sense of calling (Ryff & Singer, Reference Ryff and Singer1998). Some researchers have stated that meaning in life stems from determining life purposes and personal values (Baumeister, Reference Baumeister1991), daily decisions and actions (Maddi, Reference Maddi and Page1970), and the achievement of self-transcendence (Seligman, Reference Seligman2002). These differences have prevented the establishment of a single definition of meaning in life, but have illuminated various perspectives from which people approach the questions Who am I?, What do I care about?, and What is my calling in life? The perspective of a calling, rooted in Western culture, which focuses on individualism, typically refers to a sense of direction that a person develops through experience and reflection on life activities (Hall & Chandler, Reference Hall and Chandler2005; Elangovan, Pinder, & McLean, Reference Elangovan, Pinder and McLean2010). Dik, Duffy, and Eldridge (Reference Dik, Duffy and Eldridge2009) defined a calling as an external summons or crucial social values. Evidence has indicated that the categories of calling are identification with work, personal environment fit, value-driven behaviour, religious force, and altruistic values (Hagmaier & Able, Reference Hagmaier and Abele2012; Hunter, Dik, & Banning, Reference Hunter, Dik and Banning2010). These perspectives indicate that researchers disagree regarding the definition of calling.

Studies have identified factors influencing college students’ definition of meaning in life. These factors include college leadership (Kronman, Reference Kronman2007; Nash & Murray, Reference Nash and Murray2009), student curiosity (Kashdan & Steger, Reference Kashdan and Steger2007), cognitive variation (Park, Reference Park2010), and the cultural environment (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Dik, Wei and Zhang2014). Kronman (Reference Kronman2007) adopted a political perspective to explain why college students require support to find meaning in life. University leadership has recently placed emphasis on providing an excellent education to develop the technical skills of students and enable them to acquire various professional certificates, which contribute to school rankings and the economy of a country. Kronman suggested that these contributions are crucial; however, if colleges do not create an environment in which students are required to interact with others who are unlike them, or do not promote citizenship, then students might expect a college education to be merely vocational. Failing to create such an environment can cause students to neglect reflecting on experiences and finding meaning in life, and to fail to exhibit value-driven behaviour, self-transcendence, and altruistic values. Duffy and Sedlacek (Reference Duffy and Sedlacek2010) suggested that further action is required to foster college students’ search for meaning in life. Social service learning provides an opportunity for learners to interact with each other and the environment, develop reflective thinking, and acquire a sense of achievement (Moser & Rogers, Reference Moser and Rogers2005; Papamarcos, Reference Papamarcos2005). Social service learning can be provided to address Kronman's (Reference Kronman2007) suggestion that colleges provide more opportunities for students to interact with other people, including peers, professors, and professionals.

Meaning in Life in Collectivist Chinese Culture

Research on helping college students find meaning in life is rare and warranted. Lu and Yang (Reference Lu and Yang2005) indicated that finding meaning in life involves self-actualisation, which is performed by an independent self in society. This independent self may be influenced by the emphasis on collectivism in Chinese culture and exam culture (Turner, Reference Turner2006; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Dik, Wei and Zhang2014). These cultures were derived from Confucianism, which emphasises cardinal relationships and the importance of honouring ancestors and family connections, creating a social-relationship-oriented culture. Lu and Yang (Reference Lu and Yang2005) reported that repaying the family with personal accomplishments is a crucial means of self-actualisation among Chinese college students. Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Dik, Wei and Zhang2014) indicated that finding meaning in life entails understanding relationships and shiming (使命). The Mandarin term shiming is defined as the fulfillment of an expectation, order, or mission delegated by a superior authority. For example, college students may work diligently to pass an entrance exam, to choose a major, and to find a job in order to fulfill their parents’ expectations (Lu & Yang, Reference Lu and Yang2005). Likewise, the exam culture reinforces shiming. To attain a high social status and to be appreciated by a superior authority or society, students must pass exams, maintain high academic motivation, and exhibit diligence (Tweed & Lehman, Reference Tweed and Lehman2002; Hwang, Reference Hwang2004). In addition, methods for achieving academically and passing exams include repetition and memorisation (Mok et al., Reference Mok, Chik, Ko, Lo, Ference, Ng, Szeto, Biggs and Watkins2001). Reflective and experiential learning, which is associated with finding meaning in life by responding to a calling derived from personal reflection on learning experiences, is not confined to formal education.

Chen (Reference Chen2008) determined that strong motivation and diligence in academic work are not always beneficial and can even harm the mental health of adolescents in schools. Other scholars (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Jose, Sheldon, Singelis, Cheung and Sims2011; Steele & Lynch, Reference Steele and Lynch2013) have suggested that Chinese collectivism has become infused with Western individualism. Among college students, self-actualisation entails developing a sense of self and being benevolent in society; however, college students worry that they are unable to fulfill family expectations, to make decisions regarding their calling, and to be active in social engagement (Hirschi, Reference Hirschi2011; Lu & Yang, Reference Lu and Yang2005). Findings regarding the integration of two cultures and students’ worries have implied that counselling and learning opportunities are required in schools. Recommendations for learning opportunities that incorporate those learnings favoured in a Western context, such as encouraging students to link personal values, learning experiences and interests to identify a direction in life, may be relevant (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Dik, Wei and Zhang2014).

Based on the aforementioned research regarding collectivist and individualist cultures and the integration of the two cultures, we developed two premises. The first is that students entering college have not had many opportunities to explore their meaning in life by participating in programs in which alternative learning methods, such as social service learning, are used (Turner, Reference Turner2006). The Chinese exam culture and the evolving collectivist culture infused with individualism reinforce the notion that students require guidance to find meaning in life, which entails understanding the self and others and identifying a personal calling. A calling is not only a sense of duty to fulfill the expectations of others, but also a sense of purpose developed though learning experiences. Therefore, we focused on leadership in college education to help students find their meaning in life, enhance the students’ learning experiences, and reflect on our (i.e., the researchers) actions in the context of an evolving Chinese culture.

Study Group Via Internet Platform

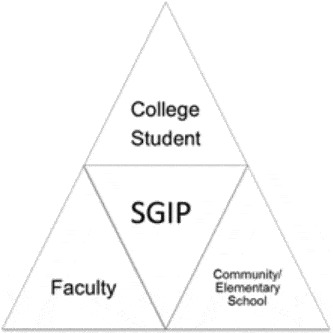

The SGIP is a social service learning model that the second author and two other administrative staff at the Fu Jen Catholic University Social Service Center designed and implemented in 2008. The philosophy of the Social Service Center is based on the philosophy of Fu Jen Catholic University (http://www.fju.edu.tw/aboutFju.jsp?labelID = 1). The Fu Jen Catholic University is an academic community of students and teachers closely associated with fostering the growth of the whole person, on the basis of Truth, Goodness, Beauty, and Holiness. The university is also committed to a dialogue leading to the integration of Chinese culture and Christian faith; to academic research and the promotion of genuine knowledge; and to the development of society and the advancement of humankind. According to this philosophy, the purposes of the SGIP are: (1) linking the faculty and students of the school to communities and facilitating academic study on service learning (see Figure 1); (2) developing a spirit of care in college students; and (3) encouraging elementary school students to enjoy reading and sharing knowledge and ideas through discussion with college students on a web-based platform.

Figure 1 The purpose of the SGIP.

The steps for implementing the SGIP were divided between the administrative staff at the centre, faculty members and elementary school teachers, who provided guidance and suggestions for activities. First, the administrative staff of the centre held a seminar on campus to explain the philosophy of the SGIP and the activities conducted using the SGIP. In addition, the administrative staff contacted administrators at the elementary schools that requested services to determine the number of classes involved. The ages of the students ranged from 6 to 12 years. Subsequently, university faculty members of various departments began to apply for collaboration courses. In the departments’ courses, students were required to use the SGIP. After collecting information from elementary schools and applications from department faculty members, the administrative staff of the centre allocated university courses to elementary schools and their classes that had requested services. The total numbers and ages of the college and elementary school students involved varied each year, depending on the number of courses held and the needs of elementary schools.

In structuring the course, the SGIP activities were jointly promoted by the university faculty members and elementary school teachers. These activities were (1) picture book reading; (2) discussion of picture books between the college students and the elementary school students on a web-based platform for at least 10 minutes per week for 10—12 weeks (each group consisted of approximately two college students and one elementary school student); (3) two 2-hour visits by college students to elementary school classrooms; (4) reflection on activity participation by the college students in the participating departments’ courses. The elementary school teachers selected three or four picture books based on discussion with the university faculty members, read the books with their students, and participated in the college students’ classroom visits. During the visits, the college students designed age-appropriate and fun activities related to the book content or the content of their professional courses to form relationships with the elementary school students. The university faculty members and elementary school teachers provided guidance and suggestions before, during, and after the activities.

A unique feature of the SGIP program is that it involved college administrative assistance and engagement from faculty members, students, and the community, reflecting the notion that finding meaning in life requires support from society and the environment (Kronman, Reference Kronman2007; Dik et al., Reference Dik, Duffy and Eldridge2009). Another feature of the SGIP program is that picture books for children and a web-based platform were used. The picture books were selected based on story content; specifically, the books were required to contain story lines related to understanding the self, caring for others, and caring for the environment. The books motivated readers to relate to the pictures and text, to see the world through the characters’ perspectives, to identify values, and to form a schema (Louie, Reference Louie2006). Previous studies have demonstrated the effect of the SGIP on children's learning in written expression and reading (Lin, Reference Lin2011; Cheung, Reference Cheung2011); however, little research has focused on how it influences other aspects of learning, particularly learning about meaning in life. Furthermore, research on how college faculty members worked with the centre and the lessons learned by those participating in the program was required.

Conceptual Framework

The foregoing literature review motivated us to conduct this action research. In addition, we were motivated to reflect on the research process and apply Mezirow's (Reference Mezirow2000) transformative learning theory to discuss the learning and challenges of the participants.

Action research focuses on changing practices and social structures, ensuring that researchers carefully observe a phenomenon and incite action to change a situation. During the research process, researchers plan, act, observe, and reflect in a continual cycle. Moreover, action research provides opportunities for people to do ‘things in ways that will fit their own cultural context’ (Brydon-Miller, Greenwood, & Maguire, Reference Brydon-Miller, Greenwood and Maguire2003, p. 14). In action research: (1) participants are assumed to be competent and reflective in the research process; (2) participants and researchers collaboratively address a problematic situation; (3) the meanings of experiences are constructed by reflecting on action; and (4) the knowledge generated from the research process is valued regardless of whether the resulting action solves problems, because the process increases the self-determination of the participants and the community (Wadsworth, Reference Wadsworth, Reason and Bradbury2006; Kindon, Pain, & Kesby, Reference Kindon, Pain and Kesby2007). We observed that college students in the Chinese exam culture lack opportunities to find meaning in life through experiences. Furthermore, our campus and community require leadership to address learning about meaning in life in addition to vocational education for college students. We observed that creating an environment conducive to finding meaning in life is crucial. We reflected on these needs and determined that action research provides methods for determining potential solutions and changes.

Mezirow (Reference Mezirow2000), who stated that learning is a process of constructing meaning, advocated the theory of transformative learning. He proposed that social interaction is vital because it provides adults with the opportunity to interact with others and find meaning during social interaction. This theory has exerted a profound influence on adult and higher education (Chang, Chen, Huang, & Yuan, Reference Chang, Chen, Huang and Yuan2012; Mezirow & Taylor, Reference Mezirow and Taylor2009), encouraging educators to provide learners with interactive learning experiences and to assess learners’ learning outcomes carefully. Mezirow (Reference Mezirow2000) divided areas of learning into three categories: technical, communicative, and emancipatory. Technical learning focuses on people's awareness of a need or difficulty and involves using techniques to solve problems. Communicative learning focuses on achieving a mutual understanding through collaboration, which requires a person to recognise the ideas and needs of others. Emancipatory learning focuses on the individual or group pursuit of self-transcendence. This type of learning requires people to access knowledge regarding past learning experiences to understand changes in their own knowledge, abilities, and values in a historical context. Based on Mezirow's learning theory, we examined the lessons that the participants learned regarding meaning in life during the social service experience, and discussed the categories of learning.

Research Method

Researchers’ Stances

Three researchers were involved in this action research. As the first author, I was the coordinator of the research, having accepted the role after reflecting on my calling, teaching experience, and literature reviews. I am also a faculty member of the Department of Child and Family Studies (CFS) at Fu Jen Catholic University. The Social Service Center's SGIP program echoed my calling, which is to provide experiential and holistic education for college students, to foster students’ reflective ability, and to support families’ and children's needs in communities. I have learned that being reflective and passionate enables professionals to care for themselves and others rather than become technicians who only meet the minimal skill requirements for a job.

The second researcher was Pang, who has been the director of the Social Service Center for 3 years and is a faculty member of the Department of CFS. He has been involved in social service learning and has designed numerous programs, including the SGIP, at the centre. His calling is to lead a meaningful life and to encourage people to construct their own life stories. Pang's philosophy is that because people take more than they give in life, they must learn to care about others, determine their needs, and provide services.

The third researcher was Chen, a faculty member of the Department of Clinical Psychology. His calling is to research issues related to positive psychology and the mental health of adolescents. He supports learning opportunities that foster healthy minds in adolescents and young adults and encourages students to find meaning in life.

Research Participants

The participants were 12 college freshmen with an average age of 18.8 years, and five third and fourth grade teachers. The students were from the Department of CFS and were selected from approximately 150 students who participated in the SGIP program. These 12 freshmen — 2 male and 10 female students — were enrolled in the Introduction to the Study of Children and Families course taught by Pang, who required students in the course to participate in the SGIP program. The students were chosen using a homogeneous sampling method, which enables a particular subgroup to be described in depth (Patton, Reference Patton2002). We adopted this sampling method to explore CFS students because they influence the lives of children and families more than other students do. We considered their learning about life meaning through the social service vital and considered them information-rich participants (Merriam, Reference Merriam2002). The other participants were five elementary school teachers in a nearby community. The teachers participated in the SGIP program by scheduling time for the college students to meet with their students, reading picture books with their students, and encouraging their students to discuss the books with the participating college students by using the platform. Thus, the 12 college students provided social services to the classes.

Interview

Patton (Reference Patton2002) posited that ‘we cannot observe how people have organised the world and meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask questions about that’ (p. 341). We therefore interviewed the students and teachers at the beginning and end of the SGIP grogram to determine the lessons that they had learned about meaning in life from participating in the SGIP program. The interview with the students comprised two parts. The first part involved asking who they thought they were, what abilities they wanted to develop, and how and why they cared for their families and friends. The second part consisted of questions on the students’ experiences during the SGIP program and questions on their reflection papers. The elementary school teachers were requested to participate in a focus group interview to elucidate their learning and the challenges that they experienced while participating in the SGIP program. The interviews were transcribed and validated by the participants.

Web-Based Discussion on the Platform

We collected content from the 12 college students’ discussions with elementary school students on the platform. The discussion time was approximately 20 minutes each week, and the program was conducted for 12 weeks.

Reflection Papers

Students’ reflection papers were collected, which were written following two visits to the elementary school classrooms and online discussions with the elementary school students, as well as from sharing activities conducted in Pang's class. In the papers, the students reflected on the following three components: What did I learn about who I am? Who and what do I care about? What do I want to do in the future and how will I achieve this goal?

Researchers’ Discussion and Reflection

The content of five meetings held during a semester and email discussions were collected to determine what we learned during the SGIP program.

Data Analysis

The collected data and the analysis were in the language of Mandarin. We translated transcripts and findings into English. We conducted a thematic analysis involving a within-case examination and a cross-case examination (Creswell, Reference Creswell1998) of the transcribed interviews, students’ reflection papers, and researchers’ reflections. The analysis was conducted using a Word document. We independently read the data several times to become familiar with it, coded the data, and identified emerging themes regarding the participants’ meaning in life. Finding meaning in life entails identifying the uniqueness of the self and others, who a person cares about, and a life calling. Following these independent analyses, the research team held a series of meetings to discuss and compare the emerging themes and resolve disagreements based on a group consensus. After conducting the within-case analysis, we conducted a cross-case analysis to identify the common and distinct themes. In addition, we used data from the web-based discussions conducted using the platform and ensured that the participants agreed with the identified themes to increase the trustworthiness of the participants’ learning.

Results

According to our data, the college students (1) learned who they are, (2) learned ways to be with people that they care about, and (3) required realistic plans. A result regarding elementary teachers’ learning was the effect of the SGIP program on their lives and the lives of their students’ families. Regarding our learning, we were reassured of our callings and determined that meaning in life cannot be found through a single activity.

Students: Learning About Who They Are

The students learned who they are. They (1) learned to appreciate themselves, (2) became aware of the need to develop professional skills, and (3) determined their interests. For example, Mandy reported that she determined her expertise and appreciated her merits, stating, ‘I found my role in a group, and others could see my merit. I was good at preparing art work for our meetings with the children. Through this opportunity provided by the service, I found what I can do.’ Similarly, Yvonne stated, ‘I found that you are good at what you are specialised in during this experience. You do not have to be jealous of others.’ Judy described her need to enrol in more courses related to children's behaviour guidance and counselling after interacting with the children. Conversely, Shelly and Ting mentioned that, through the experience, they discovered that they thoroughly enjoyed working with and learning with children, as well as the feeling of helping others.

Students: Learning Ways to Live With People They Care About

The students (1) became aware of the importance of caring for family, peers, and children, and (2) learned how to communicate and cooperate with their peers in groups. For example, Sharon reported ‘discussing books with children is another way of caring, and the content of picture books reminded me of ways to show love to my mom, such as writing her a card on her birthday’. Wendy stated, ‘I learned to express my ideas constructively, not emotionally, when preparing activities with friends.’ Yoyo reported, ‘Sharing different ideas and cooperating and engaging with others were really challenging, but helped us to become supportive friends.’

Students: Formulating Realistic Plans

When describing their future plans and calling in life after participating in the social service learning process, some participants said that they will continue to help others. However, other participants did not know whether helping others is one of their plans. Their future plans included passing exams, acquiring higher degrees, fulfilling filial duties to parents, and going abroad. For example, Jenny said, ‘I will continue helping others, but passing the exam to become a flight attendant to make money to support myself and prevent my parents from worrying is my plan.’ Some participants mentioned that they would attempt to pass English exams in order to travel abroad. For example, Yoyo stated, ‘I think that in the future I will go abroad to acquire a higher degree. This sounds realistic. Preparing for exams and studying hard are things that we can do now. I haven't really thought about what my purpose is or what I want to do as a career.’

Teachers: Learning the Effect of the SGIP Program on Their Lives and the Lives of Families

The SGIP program caused the teachers to realise the power of care and fostered their professional development. For example, one teacher shared that in her class one student from a single-parent family continually asked his grandmother who his parents were while reading picture books and participating in the SGIP program. This boy was raised by his grandmother after his parents divorced. His father had been suspicious about the child not being his own and had abandoned him. Therefore, the grandmother took the child to a hospital for a DNA test to verify the relationship. The father was regretful of his attitude and returned home to the child. The family appreciated this opportunity for their family to change. In another class, a teacher and a college student discovered that a second grade student wrote ‘I want to die’ on the platform. The teacher immediately contacted the student's parents to determine the reasons for the student's message. The student misunderstood her mother's expectations for her academic achievement and felt frustrated and worried about not being loved. After the parents reassured and comforted the student, she stopped feeling anxious and gained confidence. These stories reveal that teachers learned about family changes and the effect of the SGIP program on the lives of families.

In addition, the teachers learned that using an internet platform is an alternative approach for understanding students, and that college students exerted positive influences on their students. A teacher stated:

Providing the children with an opportunity to join the SGIP program and work with college students was an eye-opening experience for me. I learned how children think through their discussions with the college students. The experience encouraged me to spend more time in discussion with my students. It was also a professional development opportunity for me.

Researchers: Reassurance of Our Own Calling and Continuing Service is Required

We discussed how our professionalism can be determined based not only on the quantity of research publications in which we are involved but also on the creation of a campus environment in which professors, students, and community members find meaning in life. During the discussion, we realised that challenges occurred while providing the SGIP service. We learned that action research is a process that increases the self-determination of the participants and the community and generates new knowledge regardless of whether the action solves problems (Kindon et al., Reference Kindon, Pain and Kesby2007; Wadsworth, Reference Wadsworth, Reason and Bradbury2006). We examined the lessons learned from this action research and planned for the following year's SGIP program, hoping to initiate community change within 5 years. We committed to continue learning about ourselves and other people's discovery of meaning in life through social service.

We realised that people might not completely develop meaning in life through a single social service learning experience. During this study, the students began examining who they are and learned how to care for others, but confined their callings by developing realistic plans. In our meeting, Pang stated, ‘The students may not be able to find a calling, but a calling should be developed over time through self-reflection and dialogue with others. In addition, people may find their calling but may not be able to fulfill it because of many challenges.’

Discussion

According to Mezirow's perspective (Reference Mezirow2000), the students engaged in instrumental (the need to develop professional skills) and emancipatory learning (the importance of appreciating oneself and determining personal interests). Emancipatory learning is essential for framing meaning in life, because people who learn and appreciate their merits can experience a sense of happiness and engagement. These senses are positive emotions emphasised by positive psychologists (Chaudhry, Reference Chaudhry2008; Peterson, Park, & Seligman, Reference Peterson, Park and Seligman2005). The participants’ appreciation of themselves indicated that college students’ meaning in life is based not only on the role of an individual in society, as indicated by other research findings (Lu & Yang, Reference Lu and Yang2005). The participants in the SGIP program did not focus on being appreciated by a superior authority, which is emphasised in Chinese society (Hwang, Reference Hwang2006), indicating that the meaning in life as perceived by the younger generation has changed in response to the evolution of Chinese culture.

In addition, the participants learned to care for family, peers, and children, and how to cooperate with their peers in groups, indicating that they engaged in communicative learning according to Mezirow (Reference Mezirow2000). This type of learning requires a person to recognise the ideas and needs of others. Our program provided an opportunity for learners to interact and develop reflective thinking regarding care for others and how to work with peers during social service; the results are consistent with those of previous research (Moser & Rogers, Reference Moser and Rogers2005; Papamarcos, Reference Papamarcos2005). In addition to showing care for others, the students developed approaches for communicating and engaging in peer groups. This observation is inconsistent with previous research findings, indicating that finding meaning in life in Chinese society entails fulfilling an expectation of a higher authority (Yue & Ng, Reference Yue and Ng1999). The students began to reflect on experiences as observed in Western culture (Steele & Lynch, Reference Steele and Lynch2013), and realised that relationships and active involvement in peer groups are vital. Furthermore, our program provided an opportunity for college students to be active in social engagement, as suggested by a previous research finding (Hirshi, Reference Hirschi2011). Participating in this service was crucial for students’ identification of meaning in life, because learning to cooperate with others enables students to join a group and develop a sense of belonging (Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Stillman, Hicks, Kamble, Baumeister and Fincham2013).

In our study, the students learned to examine who they are and how to care for others, but confined their callings by developing realistic plans. Their realistic plans were passing exams, acquiring higher degrees, fulfilling filial duties to parents, and going abroad. We determined these callings to be similar to the callings emphasised by exam and collectivist cultures, which focus on family connections and maintaining strong motivation to achieve academically (Lu & Yang, Reference Lu and Yang2005; Hwang, Reference Hwang2004). These callings were not derived from the social service learning experience.

Damon (Reference Damon2008) determined three elements that are characteristic of young people who have found their calling: namely, having a sense of purpose, being realistic, and having support from families. Being realistic involves identifying professional abilities and applying these abilities to achieve goals. Based on Damon's three elements and the lessons learned in this study, we determined that the participants’ realistic plans were inconsistent with Damon's definitions. We attributed this difference to cultural differences and to the freshman status of the students, who were in the process of developing professional skills. Therefore, further action to support the students in developing their professional abilities, reflecting on experiences, and finding their calling may be required in the future. Another calling identified by the participants — going abroad — differs from the calling advocated in Chinese culture. This finding emphasises the need for future research to explore the meaning of going abroad as it is perceived by the younger generation of Chinese people.

Finally, Harwood, Klopper, Osanyin, and Vanderlee (Reference Harwood, Klopper, Osanyin and Vanderlee2013) stated that professionalism in education involves caring for others. The SGIP program fostered our professional development and that of the elementary school teachers and caused us and the elementary school teachers to realise the power of care. This experience reflected Mezirow's (Reference Mezirow2000) concepts of technical, communicative, and emancipatory learning. We learned that action research is a process that increases the self-determination of the participants and the community (Wadsworth, Reference Wadsworth, Reason and Bradbury2006; Kindon et al., Reference Kindon, Pain and Kesby2007) and generates new knowledge, regardless of whether the action solves problems. Although the students’ callings were not derived from reflection on the social service learning experience, we examined the lessons learned from this action research and planned for the following year's SGIP program, hoping to help the people in our communities find meaning in life and initiate community change within 5 years. We are committed to continue learning about ourselves and other people's discovery of meaning in life through social service.

Lesson Learned for Future Development

Based on our findings and discussion, we plan to continue implementing the SGIP program for the following 5 years. Next year, three aspects of the program will be modified to help participants find their calling and strengthen the effect of the program on the community over time.

First, we will develop a series of courses associated with the SGIP program, continue arranging college students’ visits to elementary schools, and modify the reflection form completed by college students. In the second and third year of the program, we intend to use the SGIP in two courses, Play and Child Education and Design of Teaching Material. We will continue to examine the results of action each year and modify plans accordingly in the following year.

The elementary school teachers reported that through their first-year experiences with college students’ visits to their classrooms, they felt supported and that they had gained opportunities for professional development. Furthermore, we observed that combining online discussion and the college students’ meetings with the elementary school students before and during the online platform discussion reduced social isolation. We will continue to support these teachers to realise how professional skills and callings are applied in real settings, as well as the influences of these teachers’ abilities on others. Accordingly, we will continue arranging the visits, but will provide students with opportunities to reflect on the connections among the learning experiences acquired, professional skills learned, and callings discovered through participation in the program with peers. Students will apply the professional knowledge and skills that they learned from courses to activity designs for elementary school students. The students will then discuss and reflect on learning experiences and the effects of courses on their ability and calling. For example, for college students who will take the Design of Teaching Materials for Children course during the sophomore year, the first author will introduce various picture books related to life education and the purposes of and methods for designing teaching materials. The college students will then guide elementary school students in creating artwork based on the content of the picture books, and invite the elementary school students to share their ideas during online discussion. After engaging in the activity and online discussion, the college students will discuss with their peers in the course any previously acquired professional skill that they applied in the service, challenges they met, and potential professional plans for themselves.

Second, we will consider using participant action research (PAR) in the future and invite elementary school teachers and college students to serve as researchers. The challenge for the elementary school teachers was not directly related to finding their calling. The teachers’ learning motivated us to explore teachers’ concerns regarding the connection between professional development and their callings. PAR entails developing an egalitarian relationship with participants to facilitate communication with and gain perspectives from them. It enables participants to express their thoughts and needs. New ideas for action can thus be generated (Mertens, Reference Mertens2005). Furthermore, PAR is a method that combines academic and grassroots knowledge (Bryceson, Manicom, & Kassam, Reference Bryceson, Manicom, Kassam, Kassam and Mustafa1982). We plan to invite teachers to present their professional stories to the college students in our courses and discuss with teachers research ideas related to finding meaning in life that they would like to explore. We will invite students who enrolled in my class and Pang's class in this study to draft personal professional development plans, to share their ideas and strategies for finding a calling, and to discuss any focus of the SGIP program related to finding meaning in life.

Third, we will consider researching the effect of the SGIP program on the meaning in life found by people on campus and in communities. In this first-year study, we explored our learning experiences and challenges regarding meaning in life as well as those of the participants in the SGIP program. However, the participating freshmen students were from only one department. Although the results indicated that the SGIP program positively influenced these students, the results would be more generalisable if more students and professors from various departments and years were to participate. Increasing the diversity of the sample would assist other researchers and practitioners in understanding how a college SGIP system engenders a cooperative environment among students and professors from various departments, and would clarify how faculty members of a university perceive the importance of searching for meaning in life within their professional fields.

Conclusion

This article describes the meaning in life that participants discovered through participation in the SGIP program and our reflections on the participants’ learning. This study provides researchers with an understanding of how a college social service learning centre in an East Asian society provided a model for researchers, college students, and community elementary school teachers to learn together and find meaning in life.

Our SGIP activity demonstrated that the benefits acquired by the college students were representative of communicative and emancipatory learning. These benefits included being aware of meaning in life from the perspective of self-understanding and approaches to being with people that they care about. These two benefits are consistent with the meaning in life characteristic of Western culture, indicating that the meaning in life of the younger generation of Chinese people has changed in response to the evolution of Chinese culture. The students confined their callings by developing realistic plans, which consisted of goals emphasised in Chinese traditional culture. The benefits attained by the elementary school teachers included technical, communicative, and emancipatory learning. The teachers received support from the college students as well as opportunities for professional development and learning about their students and their families. We were reassured of our own callings through this experience and were inspired to continue our research in the future. Future programs will involve integrating the SGIP into course activities of various years. The design of the SGIP program must be improved because a single event was insufficient for enabling students to find meaning in life. Improving the design might enhance the capacity of the SGIP program to help students find their calling in life. We will consider using PAR in the future and inviting students and elementary students to serve as researchers. We will also consider collecting data from students and professors who participated in the SGIP program from various departments and school years. These modifications of the SGIP program would demonstrate how the program can develop with the participants and the research findings, thereby revealing its effect on people on campus and in the community who are searching for meaning in life.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Taiwan National Sci-Tech Program, Ministry of Science and Technology (Grant Number: NSC102-2410-H-030-072).