Introduction

Malnutrition is a significant global public health burden with greater concern among children under 5 years in Sub-Saharan Africa(Reference Obasohan, Walters and Jacques1). Nearly half of all deaths in children under-five children are attributable to undernutrition which puts them at greater risk of dying from common infections through increasing the frequency and severity of such infections and delaying recovery(2).

In Ethiopia, over 25 000 children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) are admitted every month and the survivors are more likely to perform poorly in school and, once grown up, girls are more likely to suffer from complications during childbirth(Reference Lanyero, Teka and Negash3). SAM is a life-threatening condition among the children with SAM being nine to eleven times more likely to die than a non-malnourished child(Reference Pravana, Piryani and Chaurasiya4,5) . Early identification of SAM is important for initiating treatment and minimising the risk of complications which can be done in both community and healthcare settings using appropriate indicators(6). It can also be prevented by specific interventions including promotion of exclusive breastfeeding, vaccination and timely healthcare-seeking behaviours(Reference Sand, Kumar and Shaikh7).

Malnutrition has many unpleasant results on child health during illness and after discharge. Many children younger than 5 years in developing countries are exposed to multiple risks, including poverty, malnutrition, poor health and non-stimulating home environments. These can detrimentally affect their cognitive, motor and social-emotional development(Reference Grantham-McGregor, Cheung and Cueto8) leading to repeated bouts of SAM. Nearly half of all deaths in under-five children are attributable to undernutrition through increasing the frequency and severity of infections and delaying recovery(9).

Relapse after treatment is also another challenge of SAM case happening usually at 4 months or 16 weeks post-discharge(Reference Lelijveld, Musyoki and Adongo10). Close follow-up of children with SAM after discharge is crucial for successful management of complications including relapse and mortality during this period. Weekly follow-up is recommended, as these patients have a tendency of suffering from relapse. A quarter of these children fail to be followed up in 6 months due to migration, social, political and logistic reasons(11).

Eventhough the WHO recommends that children with SAM who are discharged from treatment programme should be periodically monitored to avoid a relapse with strong recommendation(12). However, in Ethiopia, there is a lack of study that address either time to relapse or post-discharge status. As we have seen above after treatment of SAM and discharge under-five children may face multiple health challenge, so this study is paramount important for government focus on post-discharge status of SAM children.

Methods

Study area and design

An institution-based retrospective cohort study was conducted among a cohort of children admitted for treatment of SAM from 2014 to 30 August 2020 in twenty selected health posts in Hadiya Zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia. The data were abstracted from the medical's records of children from 1 August to 30 August 2020 using a format prepared for the purpose.

In Hadiya Zone, according to the 24 May 2004 World Bank Memorandum, 6 % of the inhabitants have access to electricity, a road density of 104⋅1 kilometres per 1000 square kilometres compared to the national average of 30 km(13). The average rural household has 0⋅6 hectare of land compared to the national average of 1⋅01 hectare(14). A fifth (22⋅8 %) of the population has non-farm-related jobs compared to the national average of 25 % and a regional average of 32 %. Seventy-four percent of eligible children were enrolled in primary and 21 % in secondary schools(15). This zone is characterised by a predominant agricultural activity especially the enset, combined with grain including, barley and maize and rearing domestic animals(16).

In Hadiya Zone, there were 280 health posts (HPs), 60 rural health centres, 1 university teaching hospital and 3 primary level hospitals. Hadiya zone is divided into eleven districts for administrative purposes. The woredas were: East Bedewacho, Siraro Bedewacho, West Bedewacho and Shone town administration separated from the rest of the zone by Kembeta Tambaro and the administrative centre of Hadiya is Hosanna(16). Of which, this study was conducted in two woradas and one town administration among twenty health posts with the highest number of cases East Bedewacho Siraro Bedewacho and Shone Town administration. The health posts were selected based on the number of SAM cases.

Population

All records of under-five children who were admitted to the selected health posts in the three woradas from November 2014 to 30 August 2020 were source population. A total of 900 child records were eligible from which 760 were selected by a simple random sampling technique using ENA SMART software. Cards of children with incomplete records, unknown admission dates and unknown discharge dates were excluded. And cards of children that were admitted to program by transferee with complete records were included.

Sample size and sampling procedure

Sample size was determined from a study conducted in North Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia(17). Then, it is calculated by medcalc©version 119.1.1.3 survival analysis (logranktest) at http://www.medcal.org (Reference Mamo, Derso and Gelaye18). Diarrhoea on admission was used as the main exposure variable with outcome of 75 % a total event needed of 484. As we selected zones to woradas and from worada to Kebeles, a design effect of 1⋅5 was considered giving a final sample size of 726. Finally, the records were collected from the card room based on the medical record number of the selected participants and the data were collected from these records.

Measurement

A data extraction tool was prepared from the national treatment protocol for the management of SAM(Reference Lanyero, Teka and Negash3), SAM registration booklet with complete registration, health management information system (HMIS) register was used. The data extraction format used consisted of socio-demographic data (age, sex), time (time for first admission, time for discharge and time for readmission) and anthropometric measurements (height, weight, MUAC, oedema). Four data collectors (MPH) and one supervisor were recruited based on their experience in data collection. Data collectors received a 1-d training on the extraction tool and deployed to collect data once the principal investigator was convinced about their competency. The primary investigator of the study and the supervisors critically followed the data collection process to minimise missing information and inconsistencies.

Operational definition

Relapse/repeated episodes: admission of a child with a diagnosis of SAM that means diagnosed by weight-for-height below −3 sd of the WHO standards, by a MUAC <11⋅5 cm and by Clinical sign like bilateral oedema after being discharged with a status of recovery or treatment discontinuation for several compliant(Reference Ostend19–21).

Wasting: weight-for-height Z-score < −2. It often indicates recent and severe weight loss, although it can also persist for a long time(Reference Akparibo, CK Lee and Booth22).

Criteria for admission for the first and second; if the child have SAM: It is diagnosed by weight-for-height below −3 sd of the WHO standards, by a MUAC <11⋅5 cm and by Clinical sign like bilateral oedema(20,21) .

Kwashiorkor or oedematous malnutrition is also the form of severe undernutrition, the child's muscles were wasted, but wasting may not be apparent due to generalised oedema or swelling from excess fluid in the tissues(20,23) .

Criteria for discharging children from treatment; weight-for-height/length is ≥−2 Z-scores and having no oedema for at least 2 weeks, or mid-upper-arm circumference is ≥125 mm and no oedema for at least 2 weeks(24).

Data processing and analysis

Data were coded, entered into Ep-data version 4.2 software and exported to SPSS for windows version 25 software for analysis. The presence of missing values, possible outliers and multicollinearity were checked through exploratory analysis.

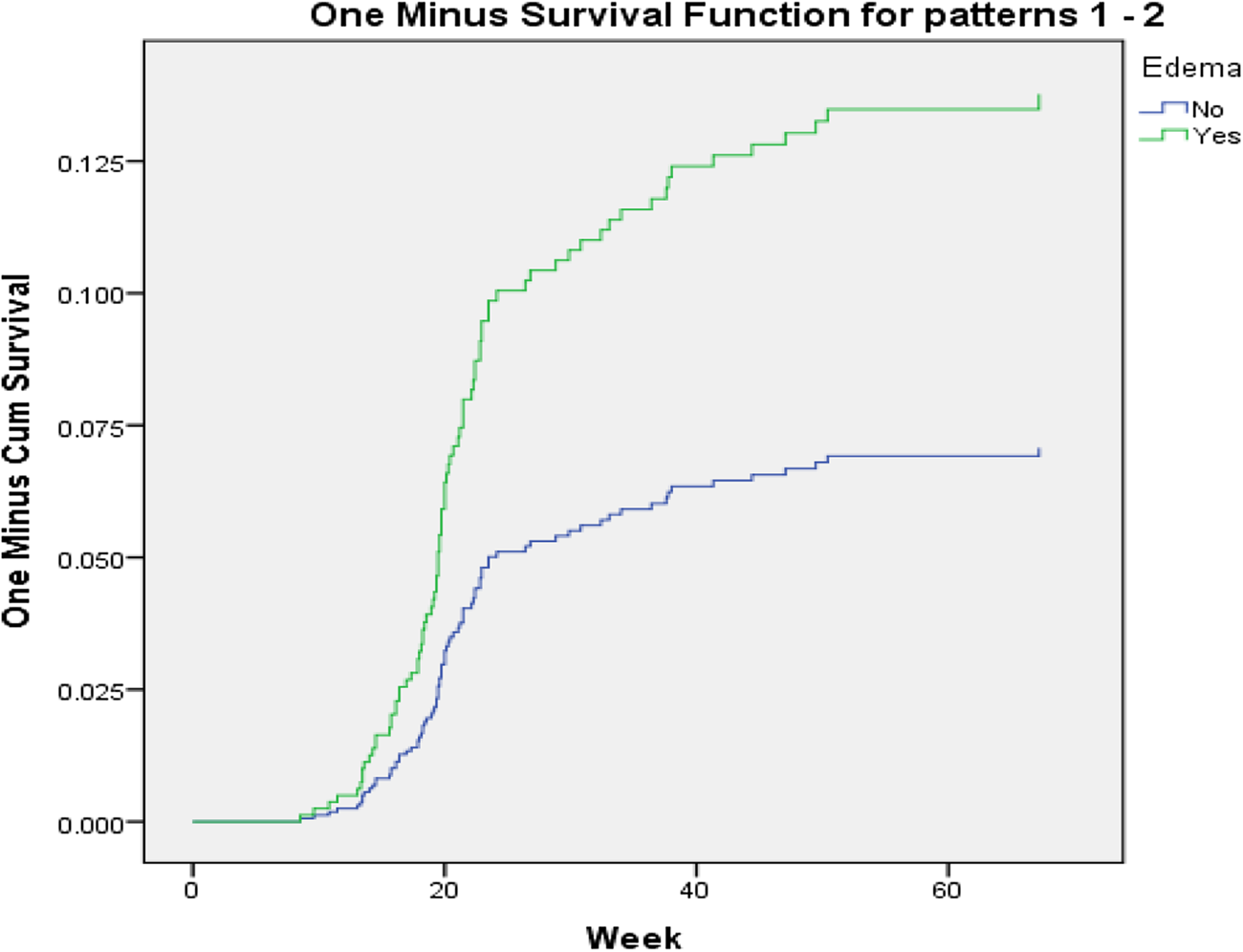

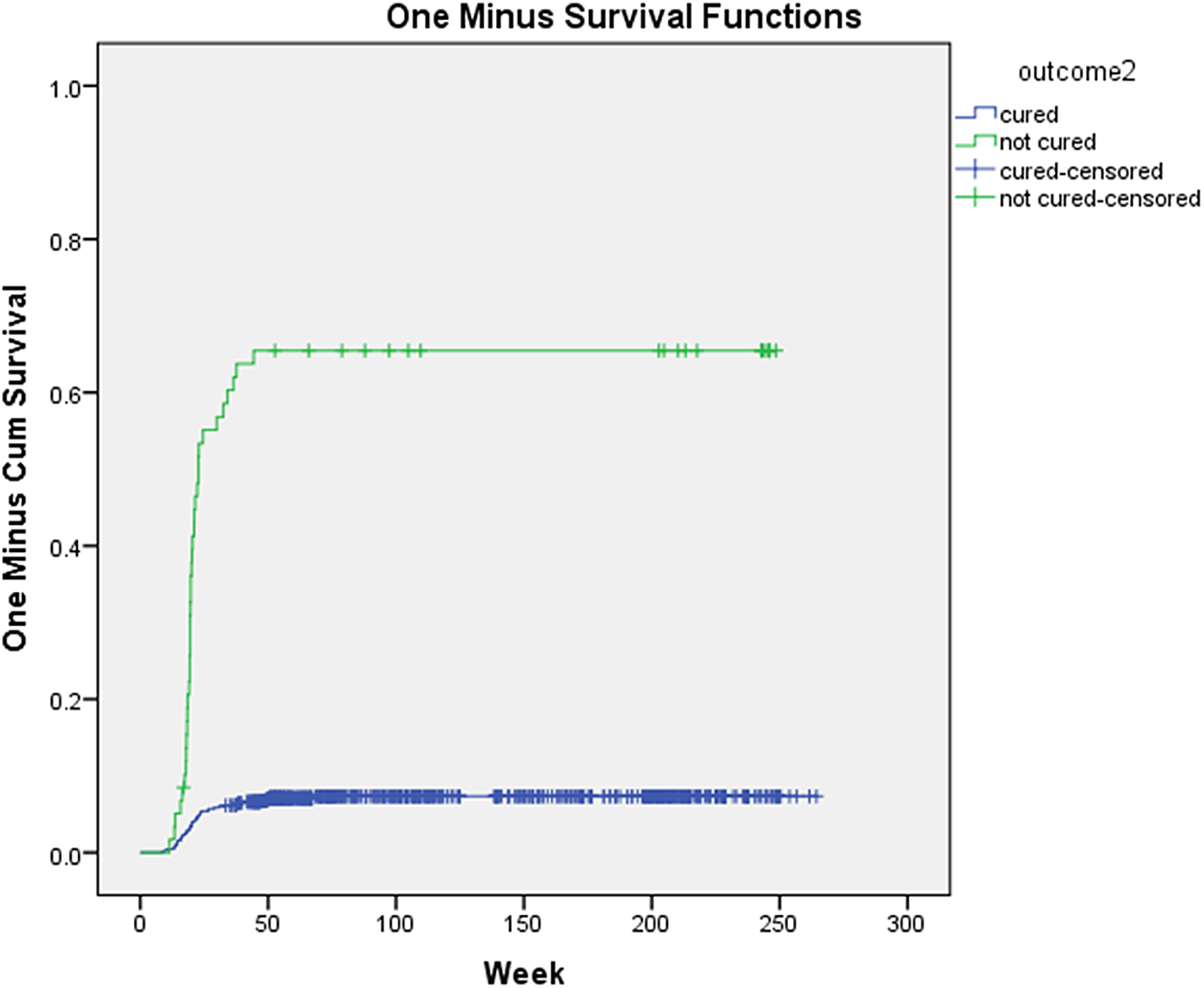

Both bivariate and multivariable Cox regression analyses were performed. Kaplan Meier hazard curve with the log-rank test was fitted to identify the presence of a difference in recovery rate among the categorical variables. Mantel-Cox and Generalized Wilcoxon test of equality of survival distributions is significant and one minus survival function line is also parallel for those candidate variables of multivariable Cox regression (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1. One minus survival function test for oedematous children in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia.

Fig. 2. One minus curve for testing parallel hazards assumption among children in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia.

For the different levels, under-five children with SAM were followed in weeks from admission to the occurrence of the event (relapse). Person-time was calculated and the incidence was determined. In the present study, person-time was reported in child-week. Child-week are total follow-up times of each child from admission to the occurrence of the events (relapse or censored).

Those variables with P ≤ 0⋅25 in the bivariate Cox regression were selected for the multivariable Cox regression analysis. All statistical tests were considered significant at P-values of <0⋅05.

Ethical considerations

Before starting the data collection process, the study was ethically approved by Jimma University Health Research Ethics Review Committee (IHRERC). An official letter was written from Jimma University to the Hadiya Zonal Health Office.

Informed written consent was obtained from all health extension workers of selected health posts and woreda health office, confidentiality of the study documents and the abstracted information was ensured according to the principle of Helsinki declaration ethical code for human subjects.

Results

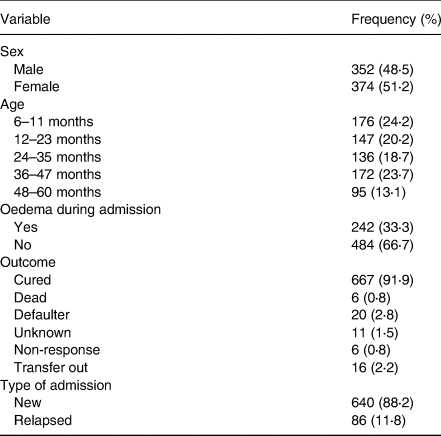

The medical charts of 726 SAM cases admitted in the 20 health posts in the last 5 years were reviewed. With regard to admission characteristics, 51 % were females, 24⋅2 % were in the age of 6–11 months followed by those in the age group of 12–23 months (20⋅2 %). Overall, 88⋅2 % (95 % CI 85⋅8, 90⋅2) were new admission, while 11⋅8 % (95 % CI 9⋅8, 14⋅2) were relapsed cases.

During the first admission, 33⋅3 % had oedema and the mean weight of children during admission was 7⋅94(±2⋅36) kg. Similarly, the mean(±sd) MUAC of children during admission was 10⋅60(±0⋅76) cm. Regarding the outcome of SAM treatment during first admission, 91⋅9 % were cured and followed by those who died (2⋅8 %). The mean(±sd) time for recovery from SAM was 10(±3⋅3) weeks for the first admission. The mean discharge weight was 11⋅15(±2⋅1) kg and mean discharge MUAC was 11⋅57(±0⋅81) cm (Table 1).

Table 1. Profile of admitted children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in Sothern region Hadiya Zone Ethiopia

Time to relapse of SAM

A total of 11⋅8 % cases were relapsed cases readmitted with SAM in the last 5 years. The mean time for relapse of SAM was 22(±9⋅9) weeks the date of discharge from the first admission with minimum and maximum time for relapse being 9 and 67 weeks, respectively.

There was disparity in the meantime to relapse by gender. The mean time to relapse was 21(±8⋅6) weeks for male children, while it was 24(±11⋅1) weeks for female children. Likewise, the mean relapse time among oedematous children was 22(±11⋅77) weeks. The mean relapse time was shorter 15(±3⋅52) weeks for children 48–60 months, while it was longer 21(±8⋅4) for children aged 24–35 months (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean time of relapse among children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in Sothern Region Hadiya Zone Ethiopia

sd, standard deviation.

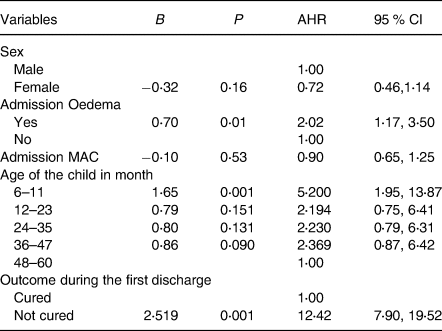

Risky factor for time to relapse

In Cox Proportional Hazards Model, after adjusting for related variables to control confounders, children in the younger age (6–11 months) had 5⋅2 times increased hazard of relapse (AHR 5⋅2, 95 % CI 1⋅95, 13⋅87) compared to the age group of 48–60 months. Similarly, having oedema on the first admission increased the hazard of relapse twice (AHR 2⋅02, 95 % CI 1⋅17, 3⋅50) compared to non-oedematous children. The hazard of relapse was 12 times higher among children who had an outcome of not cured on discharge from the first treatment (AHR 12⋅42, 95 % CI 7⋅90, 19⋅52) compared to cured ones. However, there is no association between gender and relapse in the present study (Table 3).

Table 3. Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards model identifying the determinants of time to relapse among children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in Sothern Region Hadiya Zone Ethiopia

AHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; MUAC, mid-upper-arm circumference.

Discussion

We found out that the mean(±sd) time for relapse of SAM among under-five children was 22(±9⋅9) weeks, which is a long relapse time compared to the report from Nigeria(25). This may be due to differences in study design as study conducted in Nigeria was a prospective cohort conducted for only 6 months, while the present study captured data over 5 years in addition to being a retrospective cohort which may result in differences.

In the present study, the frequency of relapse was 11⋅8 % for SAM, which is similar to the report of a study in Burkina Faso(Reference Adegoke, Arif and Bahwere26). This may show the communalities of the problem in developing countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, where the home environment is not usually altered although the child is treated for SAM in the health facility, which could lead to relapse. For SAM cases treated at home, there could also be sharing of the Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food (RTUF) resulting in suboptimal treatment and a possibly relapse. This calls for addressing the home environment especially for maternal/caregivers’ knowledge as an underlying cause of malnutrition through behaviour change communications.

On multivariable analyses, variables that were independent determinants of the hazard of relapse of SAM were: age, having oedema on the first admission and not being cured on the first discharge.

The present study showed that as the age of the child increased the hazard of time to relapse was higher. Children in the age group of 6–11 months had 5⋅2 times higher hazards of relapse compared with those in the age of 48–60 months which is supported by the report of another cross-sectional study conducted in Afar region of Ethiopia reveals that low survival rate(Reference Somasse, Dramaix and Bahwere27). This may be due to the fact that children at this age are mostly dependent on maternal source of energy. Moreover, physiologically childhood is the age when there is the highest demand for energy kg per day(28). It also may be due to the increased chance of readmission for SAM children at this age as the younger ages are likely to more frequently encounter the regular(routine) screening that is going on with the community for all children below 59 months.

Similarly, having oedema on the first admission increased the hazard relapse twice compared to non-oedematous children. This may be related to early discharge from the programme as weight is discharge criteria for SAM cases at health post. Children with oedema may have early weight gain as remnant of nutritional oedema-related weight. As nutritional oedema affects the function of the glycocalyx are dependent upon sulphated proteoglycans and other glycosaminoglycans fundamentally related to a defect in Sulphur metabolism which can explain all the clinical features of the condition, including the formation of oedema(Reference Gebre, Reddy and Mulugeta29). Children may have false weight that is related to prior oedema.

Likewise, children who were not cured during discharge from the first admission had more than twelve times higher hazard of relapse compared to cured ones. This finding is similar to the report of a study conducted in Ethiopia(Reference Golden30). This may be due to the fact that treatment discontinuation like defaulting or treatment discontinuation due to several compliant may increase the risk of readmission as children are not fully treated for the metabolic and nutritional derangements that occurred with SAM.

The results have practical implications for the management of children with SAM. The fact that SAM children with oedema and those who were not cured during discharge of the first admission had high hazard of relapse calls for reconsideration of the SAM management protocol and the discharge criteria. It also implies the need for strict monitoring of oedema before discharge and follow-up of SAM cases to avoid defaulters and partially treated cases through strong awareness creation and counselling of mothers/caregivers.

In the present study, an effort was made to cover twenty health posts to minimise sampling error. As there is no prior study on time for relapse this study will give new insight for researchers and program planners. As the present study is a retrospective cohort study, we acknowledge the limitation of not being able to assess multiple determinants, which should be addressed in future study using a prospective cohort design.

Conclusion

The finding showed that children discharged from SAM are likely to have relapse in 22 weeks time given the prevailing situation of the home environment. Having oedema during admission, being younger age and being not cured at the first discharge were independent risk factors of relapse. The results imply the need for reviewing follow-up system after discharge and working on the caring practices through behaviour change communication to improve the home environment. There is also a need for revising the discharge criteria for oedematous children rather than basing only on weight change.

Acknowledgements

I want to acknowledge my data collectors Morkete Gata and Yordanos Mezemir for their commitment to valuable data extraction and, at last, but not the least, I want to thank my mother Lero Biramo for her advice on my non-academic work that can have effect on my academic performance.

All authors in this work agreed to publish on this journal.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

A. L.: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Visualisation, Writing and original draft; D. T.: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing and review & editing; T. B.: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Software, Software, Supervision, review & editing.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.