Introduction

Food insecurity impacts approximately one in eight Americans.(1) People who experience food insecurity lack reliable, consistent access to a sufficient quantity of food to live a healthful life.(2) Households that experience low income are more likely to experience food insecurity and hunger than those with average incomes.(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Rabbitt, Gregory and Singh3) While food insecurity is a social issue that can be addressed in multiple settings, evidence points to the connection between food insecurity and negative health outcomes and increased healthcare costs.(Reference Seligman, Davis, Schillinger and Wolf4–Reference Palakshappa, Garg, Peltz, Wong, Cholera and Berkowitz9) Healthcare institutions in recent years have begun to screen for food insecurity and provide resources to address the issue, and food insecurity screening is also often part of mandatory social determinants of health screens in certain institutions and U.S. states.(Reference Sandhu, Sharma, Cholera and Bettger10) Food insecurity alleviation programmes at healthcare institutions have the potential to provide food and food-related support services directly to their patients. Provision of food not only impacts dietary intake and alleviates food insecurity, but also can free up food dollars to be spent on other necessities, such as housing, transportation, utilities, or medications.(Reference Berkowitz, Shahid and Terranova11) Food insecurity programmes implemented at healthcare institutions have previously found positive impacts on food security,(Reference Gany, Pan, Ramirez and Paolantonio12) diet quality,(Reference Liu, Alexander, Crawford, Pickard, Hedeker and Walton13–Reference Leone, Tripicchio and Haynes-Maslow17) cardiometabolic biomarkers,(Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15) hospital admission and readmission rates,(Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18) and healthcare costs.(Reference Berkowitz, Terranova, Randall, Cranston, Waters and Hsu19) They can also connect patients to resources that can alleviate food insecurity(Reference Ratcliffe, McKernan and Zhang20,Reference Carlson and Keith-Jennings21) and improve management of chronic conditions and health outcomes.(Reference Feinberg, Hess, Passaretti, Coolbaugh and Lee22) Healthcare-based food insecurity programmes are likely to be more successful if they are consistent and sustainable.(Reference Newman and Lee23)

There is a growing literature base regarding healthcare-based food insecurity programmes.(Reference De Marchis, Torres and Benesch24,25) Nonprofit and advocacy organisations, such as Feeding America, the Food Research & Action Center, and Children's HealthWatch, have established guidelines on creating and executing these programmes.(26) However, there is a lack of specific, detailed, and actionable implementation guidance for healthcare institutions of differing sizes and types to design, operate, and maintain an array of food insecurity alleviation programmes. Healthcare providers have also expressed that education and assistance with logistics would facilitate implementation of food insecurity alleviation programmes.(Reference Coward, Cafer, Rosenthal, Allen and Paltanwale27)

As a result of United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) funding, there is a small, but growing, evidence base of evaluations of produce prescription programmes,(Reference Stotz, Budd Nugent and Ridberg28) a type of food insecurity intervention located at healthcare institutions in which a provider writes a ‘prescription’ for fruits and vegetables.(29) However, produce prescription programmes may not be the right intervention for every healthcare institution and its patient population.

To support decision-makers and implementers, we aimed to create a typology of intervention components that can be used to create and execute impactful food insecurity programmes at healthcare institutions. We conducted a scoping review of food insecurity interventions based at healthcare institutions and used content analysis(Reference Hsieh and Shannon30) to create a typology of programmes. This typology may assist programme implementers consider programmatic intended impact, institutional logistical constraints, and planning for sustainability in an effort to effectively achieve their goals.

Methods

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, and Cochrane databases for papers published between 1 January2010 and 31 December2021, with the following terms: food assistance, initiative, program, health, medical, medical center, academic, community health, federally qualified, and food. We also mined reference lists of relevant research articles. We included peer-reviewed papers of interventions based at healthcare institutions in the United States that provided food assistance for their patient population. Papers were eligible for inclusion if they reported implementation and intervention details and patient population descriptions. We included papers that did not evaluate outcomes as long as details regarding programme design and implementation were included. We excluded interventions that screened for food insecurity without providing assistance obtaining food, and those that used a passive referral process, such as handing out a list of available resources, as these interventions have been found to have minimal success connecting patients to resources.(Reference Marpadga, Fernandez, Leung, Tang, Seligman and Murphy31) Our search strategy is summarised in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. This PRISMA flow diagram depicts our systematic search process that we followed in order to identify articles for inclusion in this work.

After identifying the manuscripts eligible for inclusion in the review, we created a data charting form with intervention component categories previously identified in the literature. Intervention components included the location of the program, type of healthcare institution in which the programme was located, an overview of the program, duration of patients’ participation in the program, and patient eligibility for the programme. Two reviewers, R.R. and E.M., independently read through each complete manuscript and completed the chart by extracting relevant programmatic information and performing a content analysis.(Reference Hsieh and Shannon30) Reviewers met regularly throughout the data extraction process to compare completed charts, discuss discrepancies, and create consensus. Any discrepancies were moderated by J.G.

We then analysed programme components and created the typology. We iteratively compared and contrasted different programme components to identify patterns and groupings that often were often observed together or seemed to influence other programme elements. We also compared any overlapping components or patterns found in multiple categories to further explore these classification definitions, identifying distinguishing characteristics. We continued this process through five iterations until each category had a distinct set of characteristics, resulting in a draft typology. Finally, we validated the draft typology against the research articles to ensure accuracy, with each article fitting distinctly into each category.

Results

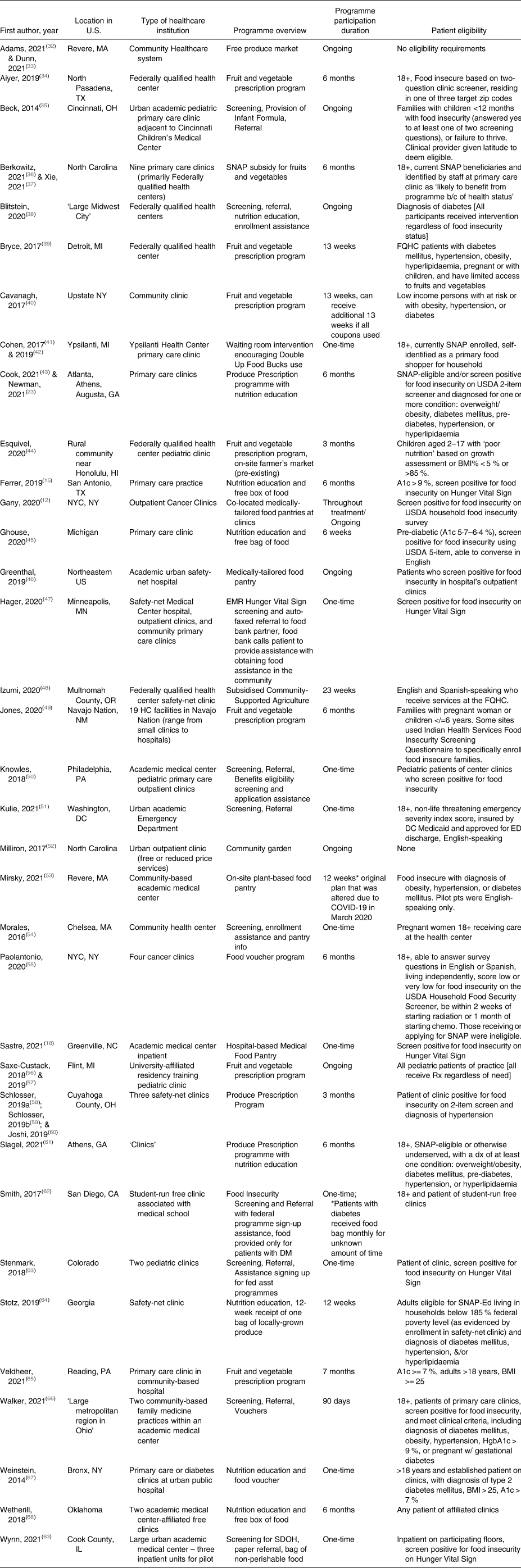

Among 8706 identified articles, forty-three met inclusion criteria. Several articles reported on the same intervention; ultimately, thirty-five distinct interventions were represented in the forty-three articles identified for inclusion. They are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Description of Healthcare-based food assistance programmes

Results of content analysis

In our content analysis, we identified eight core characteristics of healthcare-based food insecurity programmes: screening for food insecurity, defining eligibility criteria, direct provision of food, provision of vouchers, provision of referrals, offering patient education, healthcare team involved in staffing, and programme length. These characteristics were consistent with the literature, used to assess the forty-three articles in our review, and informed the creation of the typology.

Screening for food insecurity

Eighteen(Reference Gany, Pan, Ramirez and Paolantonio12,Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Berkowitz, Terranova, Randall, Cranston, Waters and Hsu19,Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,Reference Hager, De Kesel Lofthus, Balan and Cutts47,Reference Knowles, Khan and Palakshappa50,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53,Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55,Reference Schlosser, Joshi, Smith, Thornton, Bolen and Trapl58,Reference Schlosser, Smith, Joshi, Thornton, Trapl and Bolen59,Reference Joshi, Smith, Bolen, Osborne, Benko and Trapl60,Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62,Reference Wynn, Staffileno, Grenier and Phillips63,Reference Walker, DePuccio and Hefner66,Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69) of the thirty-five programmes discussed screening for food insecurity. Of these, six programmes(Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55,Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62,Reference Gany70) used the USDA Household Food Security Survey, with number of items ranging from two to eighteen. Thirteen programmes(Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35–Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye37,Reference Hager, De Kesel Lofthus, Balan and Cutts47,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Knowles, Khan and Palakshappa50,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53,Reference Schlosser, Joshi, Smith, Thornton, Bolen and Trapl58–Reference Joshi, Smith, Bolen, Osborne, Benko and Trapl60,Reference Wynn, Staffileno, Grenier and Phillips63,Reference Walker, DePuccio and Hefner66,Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69) screened for food insecurity using the Hunger Vital Sign.,(Reference Hager, Quigg and Black71–Reference Cutts and Cook73) two programmes(Reference Cohen, Richardson and Heisler41,Reference Cohen, Oatmen and Heisler42,Reference Kulie, Steinmetz, Johnson and McCarthy51) used unique screeners, and one used a ‘standardised assessment form’.(Reference Morales, Epstein, Marable, Oo and Berkowitz54) programmes that did not screen for food insecurity were either open to anyone regardless of food insecurity status,(Reference Adams32,Reference Dunn, Vercammen and Bleich33,Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52) open to patients of clinics that serve primarily low-income populations, or used medical records to identify patients with ‘poor nutrition’.(Reference Esquivel, Higa, Hitchens, Shelton and Okihiro44) One programme used the clinical expertise of an on-site nutritionist to identify eligible patients.(Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski, Bozlak, Hastings and Klein40)

Defining eligibility criteria

Sixteen(Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Berkowitz, Curran, Hoeffler, Henderson, Price and Ng36–Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski, Bozlak, Hastings and Klein40,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Esquivel, Higa, Hitchens, Shelton and Okihiro44,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53,Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55,Reference Schlosser, Joshi, Smith, Thornton, Bolen and Trapl58,Reference Schlosser, Smith, Joshi, Thornton, Trapl and Bolen59,Reference Joshi, Smith, Bolen, Osborne, Benko and Trapl60,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61,Reference Stotz, Thompson, Bhargava, Scarrow, Capitano and Lee64–Reference Weinstein, Galindo, Fried, Rucker and Davis67) of the thirty-five programmes included a cardiometabolic diagnosis (e.g. overweight, obesity, pre-diabetes, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or hyperlipidaemia) as part of their eligibility criteria. One programme(Reference Morales, Epstein, Marable, Oo and Berkowitz54) was created explicitly for pregnant women, four(Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Esquivel, Higa, Hitchens, Shelton and Okihiro44,Reference Knowles, Khan and Palakshappa50,Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance, Hanna-Attisha and Ceja57) for children, and one(Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49) for families with either pregnant women or children under age seven. Fourteen(Reference Gany, Pan, Ramirez and Paolantonio12,Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45–Reference Hager, De Kesel Lofthus, Balan and Cutts47,Reference Knowles, Khan and Palakshappa50,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53,Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55,Reference Schlosser, Joshi, Smith, Thornton, Bolen and Trapl58–Reference Joshi, Smith, Bolen, Osborne, Benko and Trapl60,Reference Wynn, Staffileno, Grenier and Phillips63,Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69) programmes required patients to screen positive for food insecurity in order to be enrolled. One programme(Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43) required patients to be eligible for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programme (SNAP) or to screen positive for food insecurity.

Direct provision of food

Fourteen programmes(Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Adams32,Reference Dunn, Vercammen and Bleich33,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,Reference Greenthal, Jia, Poblacion and James46,Reference Izumi, Martin and Garvin48,Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53,Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55,Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62–Reference Stotz, Thompson, Bhargava, Scarrow, Capitano and Lee64,Reference Wetherill, Chancellor McIntosh, Beachy and Shadid68) provided food directly to patients. Of these, eight(Reference Gany, Pan, Ramirez and Paolantonio12,Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,Reference Greenthal, Jia, Poblacion and James46,Reference Izumi, Martin and Garvin48,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53,Reference Wetherill, Chancellor McIntosh, Beachy and Shadid68) provided both produce and non-perishable foods, three(Reference Adams32,Reference Dunn, Vercammen and Bleich33,Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52,Reference Stotz, Thompson, Bhargava, Scarrow, Capitano and Lee64) provided only produce, one [40] provided only non-perishable foods, and one(Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35) provided baby formula. Refrigerated storage capacity was noted as a barrier to providing produce directly to patients.(Reference Gany, Pan, Ramirez and Paolantonio12,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53) programmes circumvented this issue by partnering with community-based organisations (CBOs) to provide same-day delivery and distribution of produce,(Reference Gany, Pan, Ramirez and Paolantonio12,Reference Adams32,Reference Dunn, Vercammen and Bleich33,Reference Izumi, Martin and Garvin48,Reference Stotz, Thompson, Bhargava, Scarrow, Capitano and Lee64) while others obtained dedicated refrigeration space.(Reference Greenthal, Jia, Poblacion and James46,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53) One programme(Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52) utilised an on-site community garden. Two programmes (Reference Gany, Pan, Ramirez and Paolantonio12,Reference Greenthal, Jia, Poblacion and James46) that provided food directly to patients offered a choice of food, while ten programmes(Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Adams32,Reference Dunn, Vercammen and Bleich33,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,Reference Izumi, Martin and Garvin48,Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53,Reference Wynn, Staffileno, Grenier and Phillips63,Reference Stotz, Thompson, Bhargava, Scarrow, Capitano and Lee64,Reference Wetherill, Chancellor McIntosh, Beachy and Shadid68) provided participants with a pre-packed bag. Three programmes (Reference Gany, Pan, Ramirez and Paolantonio12,Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Greenthal, Jia, Poblacion and James46) provided medically-tailored foods, that is, foods that met the nutritional requirements of the patient based on their medical status, as designated by their physician or registered dietitian. These three medically-tailored programmes operated as on-site food pantries.

Provision of vouchers

Fourteen programmes (Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34,Reference Berkowitz, Curran, Hoeffler, Henderson, Price and Ng36,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye37,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski, Bozlak, Hastings and Klein40–Reference Esquivel, Higa, Hitchens, Shelton and Okihiro44,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55–Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62,Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Bordner65–Reference Weinstein, Galindo, Fried, Rucker and Davis67) provided vouchers or other cash incentives that allowed participants to increase their purchasing power for food. By virtue of providing cash assistance to purchase foods, all fourteen programmes provided the participant with some form of choice in the foods they received. None of these programmes provided medically-tailored foods.

The amount of money provided to participants in voucher programmes ranged from a minimum of $6 for the entire programme in 2011 dollars(Reference Weinstein, Galindo, Fried, Rucker and Davis67) to a maximum of $230 per month for six months in 2021 dollars.(Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55) Four programmes (Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61) provided $1 (between 2015 and 2018) per household member per day.

Ten programmes(Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski, Bozlak, Hastings and Klein40–Reference Esquivel, Higa, Hitchens, Shelton and Okihiro44,Reference Saxe-Custack, Lofton and Hanna-Attisha56–Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61,Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Bordner65,Reference Weinstein, Galindo, Fried, Rucker and Davis67) allowed the vouchers to be utilised only for fresh fruits and vegetables, and three programmes(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34,Reference Berkowitz, Curran, Hoeffler, Henderson, Price and Ng36,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye37,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49) allowed voucher use for both fresh and non-perishable healthful (e.g. fruits, vegetables, or whole grains, etc.) foods. One programme allowed participants to use the voucher for any food purchases, though they were reminded to choose healthful foods.(Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55) Ten programmes(Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Cohen, Richardson and Heisler41–Reference Esquivel, Higa, Hitchens, Shelton and Okihiro44,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Saxe-Custack, Lofton and Hanna-Attisha56,Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance, Hanna-Attisha and Ceja57–Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61,Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Bordner65,Reference Weinstein, Galindo, Fried, Rucker and Davis67) partnered with farmer's markets to accept the vouchers, two(Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Esquivel, Higa, Hitchens, Shelton and Okihiro44) of which were markets located on-site at the healthcare center where the programme was implemented. One programme(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34) provided vouchers for a food pantry, and one programme(Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski, Bozlak, Hastings and Klein40) provided a voucher to be used at a mobile produce truck that parked at the health center where the intervention was implemented once weekly. Three programmes(Reference Berkowitz, Curran, Hoeffler, Henderson, Price and Ng36,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye37,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55) allowed participants to utilize the programme at participating partner supermarkets, and one(Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49) at convenience stores. Three(Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55) used debit cards and one programme(Reference Berkowitz, Curran, Hoeffler, Henderson, Price and Ng36,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye37) loaded additional funds onto EBT cards. Others used printed vouchers or tokens.

Nine programmes(Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Esquivel, Higa, Hitchens, Shelton and Okihiro44,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Saxe-Custack, Lofton and Hanna-Attisha56–Reference Schlosser, Joshi, Smith, Thornton, Bolen and Trapl58,Reference Joshi, Smith, Bolen, Osborne, Benko and Trapl60,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61,Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Bordner65) were fruit and vegetable prescription (FVRx) programmes, in which clinicians wrote ‘prescriptions’ that patients could take to farmer's markets to purchase a certain number of fruits and vegetables.

Provision of referrals

Thirteen programmes(Reference Gany, Pan, Ramirez and Paolantonio12,Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,Reference Knowles, Khan and Palakshappa50,Reference Kulie, Steinmetz, Johnson and McCarthy51,Reference Morales, Epstein, Marable, Oo and Berkowitz54,Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62,Reference Wynn, Staffileno, Grenier and Phillips63,Reference Walker, DePuccio and Hefner66,Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69,Reference Hager, Quigg and Black71) provided referrals to local or national food programmes, such as local food pantries, SNAP, or the Special Supplemental Nutrition programme for Women, Infants, and Children, commonly referred to as WIC. Of these, twelve(Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,Reference Knowles, Khan and Palakshappa50,Reference Kulie, Steinmetz, Johnson and McCarthy51,Reference Morales, Epstein, Marable, Oo and Berkowitz54,Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62,Reference Wynn, Staffileno, Grenier and Phillips63,Reference Walker, DePuccio and Hefner66,Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69,Reference Hager, Quigg and Black71) of these programmes referred to local CBOs, such as food pantries, and eight(Reference Gany, Pan, Ramirez and Paolantonio12,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38,Reference Knowles, Khan and Palakshappa50,Reference Morales, Epstein, Marable, Oo and Berkowitz54,Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62,Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69,Reference Hager, Quigg and Black71) assisted with enrollment in SNAP and WIC. Seven programmes(Reference Gany, Pan, Ramirez and Paolantonio12,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38,Reference Knowles, Khan and Palakshappa50,Reference Morales, Epstein, Marable, Oo and Berkowitz54,Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62,Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69,Reference Hager, Quigg and Black71) provided both. Six programmes(Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38,Reference Kulie, Steinmetz, Johnson and McCarthy51,Reference Morales, Epstein, Marable, Oo and Berkowitz54,Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62,Reference Walker, DePuccio and Hefner66) utilised on-site benefits specialists to assist with referrals, while five(Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Knowles, Khan and Palakshappa50,Reference Wynn, Staffileno, Grenier and Phillips63,Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69,Reference Hager, Quigg and Black71) used electronic referrals to alternative CBOs (e.g. food bank,(Reference Walker, DePuccio and Hefner66) NowPow,(Reference Wynn, Staffileno, Grenier and Phillips63) Benefits Data Trust,(Reference Knowles, Khan and Palakshappa50) medical–legal partnership,(Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35) or Hunger Free Colorado(Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69)), who then followed up with the patient.

Offering patient education

Nineteen programmes (Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,Reference Greenthal, Jia, Poblacion and James46,Reference Izumi, Martin and Garvin48,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53,Reference Schlosser, Joshi, Smith, Thornton, Bolen and Trapl58–Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61,Reference Stotz, Thompson, Bhargava, Scarrow, Capitano and Lee64,Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Bordner65,Reference Weinstein, Galindo, Fried, Rucker and Davis67,Reference Wetherill, Chancellor McIntosh, Beachy and Shadid68) provided education to patients, which included nationally-available courses such as Cooking Matters(Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,74) and ‘Eat Right When Money's Tight’,(Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38) as well as education produced by the intervention healthcare institution. Of the 19, sixteen programmes (Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53,Reference Schlosser, Joshi, Smith, Thornton, Bolen and Trapl58–Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61,Reference Stotz, Thompson, Bhargava, Scarrow, Capitano and Lee64,Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Bordner65,Reference Weinstein, Galindo, Fried, Rucker and Davis67,Reference Wetherill, Chancellor McIntosh, Beachy and Shadid68) provided nutrition education, while eight(Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,Reference Greenthal, Jia, Poblacion and James46,Reference Izumi, Martin and Garvin48,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61,Reference Stotz, Thompson, Bhargava, Scarrow, Capitano and Lee64) provided cooking demonstrations or education. Five programmes(Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61,Reference Stotz, Thompson, Bhargava, Scarrow, Capitano and Lee64) provided both. Seven of the nineteen programmes(Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Schlosser, Joshi, Smith, Thornton, Bolen and Trapl58,Reference Schlosser, Smith, Joshi, Thornton, Trapl and Bolen59,Reference Joshi, Smith, Bolen, Osborne, Benko and Trapl60,Reference Stotz, Thompson, Bhargava, Scarrow, Capitano and Lee64,Reference Wetherill, Chancellor McIntosh, Beachy and Shadid68) provided education on cooking on a budget or food resource management. Six programmes(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38,Reference Schlosser, Joshi, Smith, Thornton, Bolen and Trapl58,Reference Schlosser, Smith, Joshi, Thornton, Trapl and Bolen59,Reference Stotz, Thompson, Bhargava, Scarrow, Capitano and Lee64,Reference Wetherill, Chancellor McIntosh, Beachy and Shadid68) used passive nutrition education, such as with printed materials or online videos, while nine(Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45,Reference Greenthal, Jia, Poblacion and James46,Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61,Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Bordner65) provided in-person education or cooking demonstrations. Two programmes(Reference Izumi, Martin and Garvin48,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49) provided both printed materials and in-person cooking demonstrations. Four programmes(Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Izumi, Martin and Garvin48,Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53) provided education informally, such as during other healthcare visits,(Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52) in passing and without billing,(Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53) or during a farmer's market.(Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Izumi, Martin and Garvin48)

Health care team members involved in staffing

Staffing of interventions was varied. Screening and/or referral into interventions was completed by clinic staff in eight programmes,(Reference Gany, Pan, Ramirez and Paolantonio12,Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34,Reference Berkowitz, Curran, Hoeffler, Henderson, Price and Ng36,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye37,Reference Izumi, Martin and Garvin48,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Bordner65,Reference Wetherill, Chancellor McIntosh, Beachy and Shadid68,Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69) by a physician in three programmes,(Reference Esquivel, Higa, Hitchens, Shelton and Okihiro44,Reference Hager, De Kesel Lofthus, Balan and Cutts47,Reference Weinstein, Galindo, Fried, Rucker and Davis67) by a programme manager in one program,(Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53) by a nutritionist in one,(Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski, Bozlak, Hastings and Klein40) and by research study staff in four programmes.(Reference Cohen, Richardson and Heisler41,Reference Cohen, Oatmen and Heisler42,Reference Knowles, Khan and Palakshappa50,Reference Kulie, Steinmetz, Johnson and McCarthy51,Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55) Seven other programmes listed ‘providers’ as tasked with screening and/or referring patients into the program, but did not specify which type of provider.(Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Greenthal, Jia, Poblacion and James46,Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52,Reference Morales, Epstein, Marable, Oo and Berkowitz54,Reference Schlosser, Joshi, Smith, Thornton, Bolen and Trapl58,Reference Joshi, Smith, Bolen, Osborne, Benko and Trapl60)

Programming was staffed by an array of volunteers and professionals. While some programmes had only one type of staff member running programming, other programmes used a variety of staff to execute different functions of the program, in addition to their primary responsibilities. Community volunteers were utilised by three programmes,(Reference Adams32,Reference Dunn, Vercammen and Bleich33,Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34,Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52) while staff volunteers were used by one.(Reference Wynn, Staffileno, Grenier and Phillips63) CBOs delivered programming in seven interventions.(Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Knowles, Khan and Palakshappa50,Reference Kulie, Steinmetz, Johnson and McCarthy51,Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62,Reference Walker, DePuccio and Hefner66,Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69) A range of medical staff was used in programme delivery, such as for education: four programmes used providers,(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance, Hanna-Attisha and Ceja57,Reference Weinstein, Galindo, Fried, Rucker and Davis67) one used Registered Nurses,(Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18) one used Nurse Practitioners,(Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61) five used Registered Dietitian Nutritionists,(Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski, Bozlak, Hastings and Klein40,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61,Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Bordner65,Reference Wetherill, Chancellor McIntosh, Beachy and Shadid68) and three used Community Health Workers.(Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Izumi, Martin and Garvin48,Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Bordner65) One programme utilised a nutrition educator and licensed chef to deliver education.(Reference Ghouse, Gunther and Sebastian45) Research staff delivered programming in one intervention.(Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62)

Programme length

Eight programmes(Reference Gany, Pan, Ramirez and Paolantonio12,Reference Adams32,Reference Dunn, Vercammen and Bleich33,Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35,Reference Greenthal, Jia, Poblacion and James46,Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53,Reference Saxe-Custack, Lofton and Hanna-Attisha56,Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance, Hanna-Attisha and Ceja57,Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62) were permanent. These programmes included on-site food pantries(Reference Greenthal, Jia, Poblacion and James46,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53,Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55) and gardens,(Reference Milliron, Vitolins, Gamble, Jones, Chenault and Tooze52) two monthly on-site food distributions,(Reference Adams32,Reference Dunn, Vercammen and Bleich33,Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62) on-site distribution of baby formula,(Reference Beck, Henize, Kahn, Reiber, Young and Klein35) and a produce prescription programme.(Reference Saxe-Custack, Lofton and Hanna-Attisha56,Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance, Hanna-Attisha and Ceja57) Eleven programmes(Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Blitstein, Lazar and Gregory38,Reference Cohen, Richardson and Heisler41,Reference Cohen, Oatmen and Heisler42,Reference Hager, De Kesel Lofthus, Balan and Cutts47,Reference Knowles, Khan and Palakshappa50,Reference Kulie, Steinmetz, Johnson and McCarthy51,Reference Morales, Epstein, Marable, Oo and Berkowitz54,Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62,Reference Wynn, Staffileno, Grenier and Phillips63,Reference Weinstein, Galindo, Fried, Rucker and Davis67,Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69) included programming that each patient received only once, even if they attended the healthcare institution repeatedly. All of these programmes, except one,(Reference Weinstein, Galindo, Fried, Rucker and Davis67) included food insecurity screening and referral to federal or local food assistance programmes. Two of these programmes also provided participants with one bag of non-perishable foods from a hospital-based food pantry,(Reference Sastre, Wynn, Roupe and Jacobs18,Reference Wynn, Staffileno, Grenier and Phillips63) and one included ongoing monthly on-site food distributions to participants with diabetes.(Reference Smith, Malinak and Chang62) Eighteen(Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34–Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye37,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski, Bozlak, Hastings and Klein40,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Esquivel, Higa, Hitchens, Shelton and Okihiro44,Reference Izumi, Martin and Garvin48,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55,Reference Schlosser, Joshi, Smith, Thornton, Bolen and Trapl58–Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61,Reference Stotz, Thompson, Bhargava, Scarrow, Capitano and Lee64–Reference Walker, DePuccio and Hefner66,Reference Wetherill, Chancellor McIntosh, Beachy and Shadid68) programmes were time-limited, ranging from three to nine months. Fourteen(Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello34–Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye37,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza39,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski, Bozlak, Hastings and Klein40,Reference Cook, Ward and Newman43,Reference Esquivel, Higa, Hitchens, Shelton and Okihiro44,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas49,Reference Paolantonio, Kim and Ramirez55,Reference Schlosser, Joshi, Smith, Thornton, Bolen and Trapl58–Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville61,Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Bordner65,Reference Walker, DePuccio and Hefner66) of these programmes utilised cash assistance to increase participants’ purchasing power of food, while four(Reference Ferrer, Neira, De Leon Garcia, Cuellar and Rodriguez15,Reference Izumi, Martin and Garvin48,Reference Stotz, Thompson, Bhargava, Scarrow, Capitano and Lee64,Reference Wetherill, Chancellor McIntosh, Beachy and Shadid68) provided food directly to patients.

Results of typology development

We identified three types of food assistance programmes located at healthcare institutions: those that provide food directly to patients, those that refer patients to resources that provide food, and those that provide vouchers or cash assistance in order to purchase food. These are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2. Typology of healthcare-based food assistance programmes

Programmes that provide food directly

programmes that provide food directly to patients provide both produce and non-perishable foods and tend not to offer patients a choice of food, instead, providing a standardised pre-packed bag or box. These programmes frequently include nutrition education, and sometimes cooking demonstrations, and tend to be permanent and on-site. Examples include food pantries, community gardens, and on-site food delivery and distribution in partnership with a local food bank. Often, institutions and programmes partner with CBOs for obtaining the food to be provided.

Patients can be referred to these programmes by their healthcare providers (e.g. physicians or dietitians) and utilize the programme at any time at any time in their care, as they are static programmes. These programmes vary in size: some provide assistance to a limited number of patients, while others provide food to any patient who would benefit. Often these programmes are only developed for and provided to patients with certain diagnoses, most often nutrition-related cardiometabolic diagnoses, such as diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. However, it is not uncommon that these programmes also provide foods for all patients with food insecurity, regardless of cardiometabolic diagnosis.

Programmes that refer patients to resources that provide food assistance

Programmes that refer to resources that provide food assistance are typically available for all patients that screen positive for food insecurity, either on the Hunger Vital Sign(Reference Hager, Quigg and Black71,Reference Gundersen, Engelhard, Crumbaugh and Seligman72,Reference Cutts and Cook73) or another screening tool.(75) These programmes can be time-limited or permanent at the healthcare institution, but each participant's interaction with the programme happens only once, when they are referred to resources.

Referrals can be to local CBOs such as food pantries, regional resources such as a Feeding America site, or enrollment assistance with federal food assistance programmes such as SNAP and WIC. Enrollment assistance happens both on-site or via referral to a CBO to assist.

Referral programmes are more limited in scope than other food assistance programmes. Because the programme consists of a referral to an outside entity, the healthcare institution has no control over the type of food provided; patients instead receive food assistance from the CBO or federal programme. Nutrition education is rarely provided by the healthcare institution in tandem with the referral programme. Reach for these programmes is significant; many patients are able to be referred. The referral programmes we identified used research staff to complete the patient identification and referral process. Use of temporary research staff, rather than permanent healthcare staff, highlights the uncertainty of programme funding and sustainability.

Programmes that provide vouchers to purchase food

Programmes that provide vouchers to purchase food are time-bound, providing patients with vouchers for an average of three to six months. They are typically available for patients with both food insecurity and a health status associated with nutritional risk (e.g. pregnancy obesity, underweight) or cardiometabolic disease. Produce prescription programmes, which are a type of voucher program, are frequently funded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive programme (GusNIP), which requires that they reach low-income populations with diet-related health conditions.(29)

Voucher programmes prioritize the procurement of fruits and vegetables over non-perishable foods and provide a choice of foods within this limitation (i.e. patients can choose which fruits or vegetables they would like to purchase with their voucher). Nutrition education and cooking demonstrations are frequently paired with these programmes. Partnerships with food purveyors, such as farmers, farmer's markets, supermarkets, and convenience stores, are necessary for providing a venue in which the vouchers are accepted.(29,Reference Caceres76) These programmes are often limited in reach, helping fewer patients than other types of programmes, likely due to the cost of providing financial assistance. These programmes often require a physician to refer the patient to the program; they are rarely open to all patients; only those with a prescription can participate.

Discussion

We used results of our scoping review to create a typology that identified three distinct types of healthcare-based food insecurity interventions: those that provide food directly to patients, those that refer patients to resources that provide food assistance, and those that provide vouchers to purchase food. Our findings from the typology indicate that logistical considerations and constraints impact feasibility of healthcare-based food insecurity interventions. Important logistics to consider include staffing, refrigeration and storage space, existence of willing CBOs and partners, and programme goals.

Staffing of food insecurity alleviation programmes varied by the type of programme: programmes that provide vouchers or financial assistance to patients often require a physician to refer qualifying patients to the programme, while programmes that provide food directly to patients utilize a variety of clinic staff members, such as registered dietitians and community health workers. Referral programmes rarely used permanent staff, and often filled these positions with members of the research team.

Implementation science literature indicates that staffing of healthcare-based programming heavily influences implementation and sustainability.(Reference Shelton, Cooper and Stirman77) Analysing staff capacity prior to programme development and implementation and aligning programme choice with existing capacity should help to ensure that adequate human resources are in place. Physicians have previously reported that limited training and time during patient visits are barriers to implementing voucher programmes.(Reference Stotz, Budd Nugent and Ridberg28) If adequate training and time is unavailable, implementers may wish to consider a programme that does not require physician involvement, such as a referral programme. Importantly, having a dedicated, paid, staff member, rather than a volunteer programme champion, to run any type of food insecurity alleviation programme improves provider experiences and overall programming.(Reference Stotz, Budd Nugent and Ridberg28)

Refrigeration and storage space for food provision also heavily impacts the type of programming a healthcare institution can implement. For example, many of the programmes we included in the review lacked refrigeration space for storing fresh produce; some programmes chose to ameliorate this issue by providing only non-perishable foods, while others partnered with CBOs to deliver fresh produce to be distributed to patients on the same day. Securing space agreements and identifying community partners early in programme development not only help to increase likelihood of programme success but also dictate what type of programme may best fit the needs of the healthcare institution and patient population.(Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53)

Community partnerships were influential in almost all the programmes we identified. Programmes that provided food directly to patients often partnered with local food banks to source the food; referral programmes partnered with CBOs to assist with registering patients for SNAP and WIC, or to local food pantries for additional food resources; and programmes that provided vouchers to patients often partnered with food purveyors such as farmers markets or supermarkets. Identifying and working with community partners early in development and implementation of food assistance programmes will dictate what programming can be provided effectively.(29,Reference Mirsky, Zack, Berkowitz and Fiechtner53,Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69) .

In addition to logistical constraints, healthcare institutions should consider their goals for the program, including how many and what type of patients they aim to reach and the length of time of the intervention they foresee. As evidenced in the typology, programmes that wish to serve a greater number of food insecure patients may wish to implement a referral program, which allows for higher throughput than a voucher or food provision programme.(Reference Stenmark, Steiner, Marpadga, DeBor, Underhill and Seligman69,Reference Hager, Quigg and Black71) Alternatively, institutions that wish to provide programming for patients with the dual burden of food insecurity and cardiometabolic disease may choose to implement a more rigorous, but less wide-reaching initiative, such as a fruit and vegetable prescription programme.(29) It is, however, important to consider the length of the intervention; provision of food for a months-long period is a worthy goal but may lack durability of any health or food security outcomes observed.(Reference Newman and Lee23)

A limitation of this typology is that we do not include information on programme sustainability. Healthcare institutions that aim to create food insecurity alleviation programmes should consider not only their implementation, but their plan for sustainability. Research indicates that sustainability of healthcare-based programmes is heavily influenced by organisational support, staff turnover, and funding.(Reference Newman and Lee23,Reference Shelton, Cooper and Stirman77) Being explicit about programme components and clearly defining scope of work and processes can increase sustainability and achievement of strategic outcomes.(Reference Fiori, Patel and Sanderson78) Referral programmes may be best able to reach the largest number of patients, but follow-through to ensure that patients are connected to and receive resources is a challenge.(Reference De Marchis, Torres and Benesch24)

A second limitation to this typology is that we did not assess programme outcomes, but rather the implementation and programming. Importantly, a 2019 review of healthcare-based food insecurity interventions found that the majority of studies were low quality and most analysed only process outcomes.(Reference De Marchis, Torres and Benesch24) Evaluation of programme impacts and outcomes, such as improvements in health or decreased healthcare utilisation, can lead to increased funding, and thus sustainability, of these programmes.(Reference Stotz, Budd Nugent and Ridberg28) Formal evaluations are often not done, however, because many of these programmes are small in scope and created by clinical staff members to help patients, rather than researchers aiming to evaluate a programme.(Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Knehans79) Additionally, it is difficult to assess the body of literature as a whole because of the heterogeneity of programme components(Reference De Marchis, Torres and Benesch24,Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Knehans79 ) and goals: some to improve food security and some to improve overall health and healthcare spending. Future research should aim to identify which programme components and outcomes are most important for improving food insecurity among patient populations.

Lastly, this scoping review and typology included only interventions from the peer-reviewed literature; there are certainly other healthcare-based food insecurity programmes in the United States that have not published peer-reviewed literature of their findings.(Reference Feinberg, Hess, Passaretti, Coolbaugh and Lee22,25,Reference Feinberg, Slotkin, Hess and Erskine80) There is likely significant institutional knowledge at other sites, and the field would benefit from tapping into both the positive and negative experiences of existing programmes. Communities of practice, focused forums, and other forms of information sharing may be the best way to identify learnings and innovations, and ultimately share effective practices.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2023.111

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Eilisha Manandhar, MPH, for her assistance with the scoping review.

This work was supported by the Boston University School of Public Health Maternal and Child Health Center of Excellence Doctoral Fellowship in Maternal Child Health Epidemiology (R.R.). The funder had no role in the design, analysis, or writing of this article.

All authors contributed to this manuscript. R.R. assisted with conceptualisation the study design, conducted data collection and analysis, and authored the manuscript. E.B. assisted with conceptualisation of the study design and provided substantial feedback and edits with the manuscript. K.S. assisted with conceptualisation of the study design and provided substantial feedback and edits with the manuscript. M.-L.D. assisted with conceptualisation of the study design, provided guidance regarding data analyses and creation of the typology, and provided substantial feedback and edits to the manuscript. J.G. assisted with conceptualisation of the study design, provided guidance regarding data analyses and creation of the typology, and provided substantial feedback and edits to the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Boston University School of Public Health Maternal and Child Health Center of Excellence Doctoral Fellowship in Maternal Child Health Epidemiology (R.R.). The funder had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This research did not involve human participants.