Background

Widespread child undernutrition is one important problem in Africa(Reference Onyango, Jean-Baptiste and Samburu1) and Ethiopia(Reference Girma, Woldie and Mekonnen2,3) . According to the World Health Organization (WHO), wasting, stunting and being underweight are the main forms of undernutrition defined as z-scores less than −2 standard deviations of weight for height, height for age and weight for age, respectively(4). Globally, 144 million children under 5 were stunted in 2019(5). Among the three forms of the above-mentioned undernutrition, stunting is a devastating result of poor nutrition during fetal development and in early childhood(Reference de Onis and Branca6). At the global level, more than one in four children under the age of 5 years are stunted and Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia suffer the heaviest burden, with 75 % of the world's stunted children(Reference De Onis, Dewey and Borghi7).

Undernutrition in children occurs from multifaceted factors, including food insecurity(8–Reference Bantamen, Belaynew and Dube10). One of the underlying causes of undernutrition in the conceptual framework of UNICEF is mainly linked to poor dietary intake(11). This indicates a high vulnerability to undernutrition among children from food-insecure households. Although food insecurity affects the nutritional status of the general population, its effect is more serious on the venerable segment of the population mothers and children(12).

Ethiopia is one of the countries reported with the worst food crises in 2018(Reference Lartey13). Food insecurity in the Ethiopian context is a serious problem and the majority of the country's population lives in rural areas(14,Reference Bokora15) . Moreover, the number of food-insecure people in the country is increasing from year to year. For comparison 2⋅9 million in 2014 and 4⋅5 million in 2015 were estimated to be food insecure, and by the end of the same year, this figure had increased by more than twofold (10⋅2 million)(16). According to the report of FAO, despite the ongoing assistance in Ethiopia, an estimated 8 million people were severely food insecure and the situation worsens between July and September, due to erratic rains, conflict and high food prices(Reference Berhanu17).

Food insecurity and malnutrition were one of the public health problems in Ethiopia and throughout Sub-Saharan Africa(18). In these regions, a high number of children were reported to be suffering from undernutrition(Reference Burchi, Scarlato and D'Agostino19), and an increased risk of food shortage related to a variety of factors(20). The country is facing multiple, underlying vulnerabilities, for child undernutrition including food insecurity(Reference Fufa and Laloto21,Reference Yirga, Mwambi and Ayele22) . In addition to several factors(Reference Bantamen, Belaynew and Dube10–14), the emerging global problem, the COVID-19 is likely to exacerbate the existing food security problems in these regions(Reference Zidouemba, Kinda and Ouedraogo23). The situation may be exacerbated in many ways including being an obstacle to imports and transportation problems, related to a combination of lockdowns and travel restrictions. And hence it is logical that this may exacerbate the already considerable burden of malnutrition and food insecurity, and the worst effect is expected among the poor communities(24). Because of these and related conditions, the country is at risk of secondary impacts of COVID-19 such as increased cases of acute and chronic malnutrition(25); although data are reported inadequate on the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 in settings vulnerable to food insecurity(Reference Omar, Elfagi and Nouh26).

During our data collection, the Ethiopian government began a contact tracing and isolating those who tested positive for the virus, closed schools, banned all public gatherings and sporting activities, and recommended social distancing a few days after the report of the first case of COVID-19 in March 2020. Although the travel restrictions can be effective in minimising the spread of the virus, they may play a negative role in the economy of the country(Reference Hirvonen, Abate and De Brauw27). Therefore, the present study aimed to assess the food insecurity situation, nutritional status and risk factors among children 6–23 months during the emergence of the pandemic COVID-19 enabling us to anticipate its effect in this poor rural setting.

Methods

Study area and design

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in the Siraro district, East Shoa Zone of the Oromia region from March to May 2020. Siraro district is located 322 km southwest of the capital Addis Ababa. The population of the district is estimated at 213 741 of which, 106 870 are females. The total households of the district were reported at 44 531. Administratively Siraro District is divided into 32 kebeles (smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia) (28 rural and 4 towns). The mean annual temperature of the district is found between 13 and 25°C. However, there is a slight variation in temperature from month to month. The district is among the most impacted by climate variability-induced hazards in the region, and one of the largely food-insecure districts targeted for social security programmes by the government of Ethiopia(28).

Sample size and sampling procedure

Children 6–23 months of age with their mothers living in the Siraro district were the study population. The sample size was calculated using the single population proportion formula with assumptions of 32 % stunting prevalence in Ethiopia(Reference Tasic, Akseer and Gebreyesus29), 5 % marginal error, 95 % confidence level and 5 % nonresponse rate. A total of 371 mother–child pairs were included in the study. The numbers of subjects were allocated proportionally from the kebeles based on the total number of households with 6–23 months children in each kebele. Study subjects were then selected by simple random sampling using a list of households in each kebele.

Data collection tools and techniques

We used the survey research method to collect the necessary information from sample respondents by a semi-structured questionnaire administered in a local language (Afan Oromo) as a major type of data collection method. These data were collected focusing on socio-demographic, economic, food insecurity status, maternal characteristics (antenatal and postnatal care), dietary, anthropometric and child morbidity characteristics (respiratory illness, diarrhoea and ear infection). The demographic data included the age and gender of the children, and household size (number of residents in a household). Child mothers or caretakers were asked to provide information on the child's age which was confirmed using child immunisation cards where available. Where cards were unavailable, the mothers or caretakers were asked to recall or use references to calendar events. The nutritional status of the child was assessed by anthropometric measurements undertaken in all eligible respondents in the selected households including height/length and weight for children standard categories of nutritional status are reported according to the WHO classification of anthropometric measurements cut-offs(Reference De Onis30). After removing shoes and extra clothing, the child weight was measured to the nearest 0⋅1 kg using a calibrated SECA electronic balance with a measuring range of 25 kg. Instrument calibration was checked before weighing each child and the weighing scale was tested daily against a standard weight for accuracy. Height and length were measured to the nearest 0⋅1 cm using the UNICEF wooden height and length boards while weight was assessed to the nearest 0⋅1 kg using a calibrated SECA electronic balance.

The dietary diversity score (DDS) was developed from a single-pass 24 h recall by asking mothers about all foods the child had consumed for meals and snacks in the 24 h before the survey. The data collector wrote a list of the foods consumed; the numbers of meals and snacks were summarised and the foods consumed were subdivided into the seven standardised food groups after completing the interview. The consumption of any amount of food from a food group was sufficient for it to be included. The seven food groups were (1) cereals, roots and tubers; (2) legumes and nuts; (3) dairy products; (4) flesh foods (any meat, fish or poultry product); (5) eggs; (6) vitamin A-rich vegetables and fruits and (7) other fruits and vegetables. Consuming ≥4 of the seven standardised food groups was labelled as adequate diversity and <4 groups were inadequate. The dietary diversity score was computed using Mean ± sd and children who scored less than and more than four food groups were also reported(31). The meal frequency of the child was determined by asking the mother how many times the child took solid, semisolid or soft foods in the 24 h preceding the survey. Accordingly, ≥2 times for breastfed infants aged 6–8 months, ≥3 times for breastfed children aged 9–23 months and 4 times for non-breastfed children aged 6–23 months were considered to mean the children received the minimum meal frequency(32).

The Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) is a continuous measure of the degree of food insecurity (access) in the household in the past 4 weeks (30 days). The total HFIAS can range from 0 to 27, indicating the degree of insecure food access. For the present study, it was assessed by classifying it as food secure if it had not experienced any food insecurity conditions or had rarely worried about not having enough food, whereas food-insecure households were categorised as mild, moderate and severe following the guidelines. The HFIAS was used to measure the status of food insecurity. This scale categorises households into four levels of household food insecurity: food secure, mild, moderate and severely food insecure. This was proposed by the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA)(Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky33). This instrument is a simple and valid tool to measure the access component of household food insecurity(Reference Knueppel, Demment and Kaiser34). The research instrument was pre-tested with 5 % of the total sample size out of the study area. This instrument was assessed for clarity, time to complete, understandability and completeness. Some questions were re-formed and re-ordered to carry out the objectives of the study and interview respondents smoothly. Adequate training was given to data collectors and supervisors on data collection techniques by the lead author. The data collectors administered the questionnaire privately to ensure confidentiality

Statistical analysis

The analysis was done using STATA 14 (Stata/se 14) statistical package. Frequency, percentage, mean and standard deviation were computed from continuous variables. Variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to check collinearity and non-collinear variables were included in the independent binary logistic regression model. Variables with a P < 0⋅05 in the multivariable logistic regression analysis were used to declare statistical significance with a 95 % confidence interval.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

Three hundred fifty-four study participants were involved in this study of 371 participants planned to be included, with a response rate of 95 %. Nearly half of the participant children were females (Table 1). The mean (±sd) age of the children was 14⋅5 (±4⋅6) mo and the mean family size was 4⋅9 (±1⋅8) persons. More than 14 % of households had three or more under-five children. Nearly 67 % of the households were food insecure, out of which 30 % were severely food insecure (Table 4).

Table 1. Socio-demographic and anthropometric measures of participants from Siraro district, Ethiopia, 2020 (n 354)

LAZ, length for age z-score; sd, standard deviation; WAZ, weight for age z-score; WLZ, weight for length z-score.

Maternal characteristics

The majority (92 %) of mothers reported the pregnancy for the first child within the age range of 15–26 years (Table 2). Nearly 26 % of mothers gave five or more live births and 21 % of child mothers had more than three antenatal care (ANC) visits for their most recent pregnancy. Four percent of mothers gave their most recent birth at a health facility. More than 50 % of participant mothers did not ever have postnatal care (PNC) for their most recent delivery. Furthermore, more than 95 % of mothers did not get postpartum vitamin A supplements after this delivery as recommended by the World Health Organization(35).

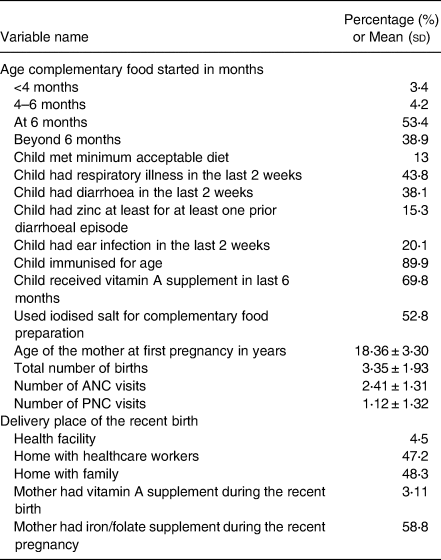

Table 2. Child feeding practices, and health characteristics of participants from Siraro district, Ethiopia, 2020 (n 354)

Child feeding practice

Fifty-three percent of children started complementary food at 6 months of age (Table 2). Nearly 20 % of children had adequate diet diversity reported from the 24 h dietary information (Table 3). The majority of children (94⋅9 %) are fed cereal-based foods. Only 15 % had flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry, liver/organ meats). The egg was consumed nearly by 25 % and vitamin A-rich (yellow, green and red coloured) vegetables and fruits by 18⋅6 %. Nearly 13 % of participant children met the minimum acceptable diet criteria, 53⋅1 % of participant children ate animal source food within a week interval and 15⋅3 % of children had zinc at least for one prior diarrhoeal episode (Table 2). Participant mothers who used iodised salt for complementary food were 52⋅8 %.

Table 3. Dietary diversity score of infants and young children (6–23 months) from Siraro district, Ethiopia, 2020 (n 354)

Child health characteristics

In the 2 weeks preceding the survey, 44 % of mothers reported their children had respiratory infections, 20 % reported an ear infection, and 38 % reported their children experienced diarrhoea (Table 2).

Prevalence of child undernutrition

Totally, 42⋅7 % (95 % CI 37⋅5, 47⋅8) were stunted, 9⋅9 % (95 % CI 7⋅12, 13⋅4) wasted and 27⋅7 % (95 % CI 23⋅2, 32⋅6) underweight (Table 1). Stunting and underweight were common among children in the 12–23 months age group compared to the 6–11 months age (Table 4).

Table 4. Distribution of household food insecurity access prevalence (HFIAP) Siraro district, Ethiopia, 2020 (n 354)

Factors associated with child undernutrition

The multivariate logistic regression model that adjusted for covariates (Table 5), identified significant associations with stunting at P < 0⋅01 for age, gender and zinc supplements as well as associations at P < 0⋅05 for parity, iodised salt intake and child diet diversity. Among these variables, more than fourfold higher odds of stunting were found among children in the 12–23 months group (AOR 4⋅02; 95 % CI 2⋅27, 7⋅12), compared to 6–11 months infants. Girls have more than 1⋅9 times higher odds of being stunted (AOR 1⋅84; 95 % CI 1⋅21, 3⋅08), compared to boys. Similarly, children who never had therapeutic zinc supplements for diarrhoea showed more than four folds higher odds of being stunted (AOR 4⋅93; 95 % CI 2⋅12, 10⋅92), compared to those who had at least once in life. Those children whose mothers had five or more times birth also showed nearly double fold higher odds of being stunted (AOR 1⋅95; 95 % CI 1⋅15, 3⋅30), compared to those whose mothers had less than five births. The adjusted odds of stunting among children who consumed less than four food groups in the 24 h before the survey was 1⋅92 (95 % CI 1⋅05, 3⋅49), compared to those who had four or more food groups. The adjusted model predicting wasting (Table 6) identified family size, growth monitoring and maternal income to be significantly associated (P < 0⋅05).

Table 5. Factors associated with stunting among 6–23 months children from Siraro district, Ethiopia, 2020a

AOR, adjusted odd ratio; COR, crude odd ratio.

a n 354.

b Reference categories.

* Statistically significant P < 0⋅05.

** Statistically significant P < 0⋅001.

Table 6. Factors associated with wasting among 6–23 months children from Siraro district, Ethiopia, 2020a

AOR, adjusted odd ratio; COR, crude odd ratio.

a n 354.

b Family size in number.

c Reference categories.

* Statistically significant P < 0⋅05.

Being in a family size of five or more was significantly associated with wasting (AOR 2⋅40; 95 % CI 1⋅10, 5⋅23), compared to those children from a family size of less than five. Children who do not receive growth monitoring services have relatively higher odds to be wasted (AOR 0⋅43; 95 % CI 0⋅20, 0⋅92), compared to those who received. Likewise, children of mothers who have their income showed more than threefold higher odds of being wasted (AOR 3⋅57; 95 % CI 1⋅21, 10⋅53).

Regarding underweight, the multivariate logistic model (Table 7) detected an association of zinc supplements, and total number of birth (P < 0⋅01), and diet diversity (P < 0⋅05). Children from mothers with five or more number births showed more than two folds higher odds of being underweight (AOR 2⋅00; 95 % CI 1⋅19, 3⋅37) than children from mothers with less than five births. Likewise, children who had never received zinc supplements were >4 times more likely to be underweight (AOR 4⋅35, 95 % CI 1⋅66, 11⋅40), compared to those who had at least once in life. Finally, more than two folds higher odds of being underweight were found among children who do not meet the minimum diet diversity (AOR 2⋅09, 95 % CI 1⋅06, 4⋅14), compared to those who had met.

Table 7. Factors associated with underweight among 6–23 months children from Siraro district, Ethiopia, 2020a

AOR, adjusted odd ratio; COR, crude odd ratio.

a n 354.

b Reference categories.

* Statistically significant P < 0⋅05.

** Statistically significant P < 0⋅001.

Discussion

The prevalence of stunting is consistent with prior studies reported from Ethiopia(Reference Amare, Ahmed and Mehari36,Reference Dake, Solomon and Bobe37) but much higher than stunting rates reported in previous studies in 2014, 23⋅3 %(Reference Seedhol, Mohamed and Mahfouz38), and in 2015 17⋅1 %(Reference Ubeysekara, Jayathissa and Wijesinghe39). Although an association between household food insecurity and child undernutrition has been reported in previous studies from Bangladesh(Reference Hong, Banta and Betancourt40) and Pakistan(Reference Baig-Ansari, Rahbar and Bhutta41), our study did not show significant associations of this variable with either stunting wasting or underweight. Quite likely a lack of statistical symmetry on the distribution of households in the present study contributed because the study specifically was conducted in a largely food-insecure area. A similar finding was also noted in our previous published study(Reference Tafese, Reta Alemayehu and Anato42).

Our study revealed the risk of stunting increased with the age of the child. A similar finding was reported from prior studies in 2017 and 2018 from Ethiopia(Reference Geberselassie, Abebe and Melsew43,Reference Derso, Tariku and Biks44) . The plausible reason may be as children grow older they have greater energy needs. Besides, stunting reflects chronic malnutrition that can be manifested after long-term nutritional deficiency. The other factor associated with stunting in the present study was inadequate diet diversity, which was consistent with the finding from previous studies(Reference Arimond and Ruel45,Reference Mallard, Houghton and Filteau46) . It is a known fact that adequate complementary feeding is a challenge for children aged 6–23 months in Ethiopia(3,Reference Bantamen, Belaynew and Dube10,Reference Fufa and Laloto21) . This is due to the number of food groups the child had has been considered as a proxy indicator of diet quality and nutrient adequacy(Reference Bosch, Baqui and van Ginneken47,Reference Islam, Sanin and Mahfuz48) , and this may play a crucial role in the linear growth of children.

Contrary to previous studies(Reference Baig-Ansari, Rahbar and Bhutta41,Reference Shrimpton, Victora and De Onis49,Reference Bork and Diallo50) , the present study showed that girls were more stunted than boys. As reported by our previous study(Reference Tafese, Reta Alemayehu and Anato42), in Ethiopia, where girls are discriminated against(Reference Belachew, Hadley and Lindstrom51), the first choice may have been given to the needs of male children, especially as the household experienced a greater food shortage.

Our data showed high odds of being stunted among children who never received zinc supplements for diarrhoea. Though, a significant proportion of zinc-deficient children in Ethiopia(Reference Dassoni, Abebe and Ricceri52), poor implementation of micronutrient supplementation have also been reported(3). These emphasised the need for improvement of the micronutrient supplement programme.

Having more siblings was associated with higher odds of being stunted and underweight, and this is a piece of supporting evidence for a previous study from Ethiopia which stated that children whose mothers gave birth to more than four children were more likely to be stunted compared to those children who born from mothers who had only one child(Reference Asfaw, Wondaferash and Taha53). This may be related to families with more children may face difficulty in providing proper care for child growth and development.

The age of the child is one of the risk factors for child undernutrition. This finding suggests a need for initiatives focused on improving infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices and diet diversity, particularly those associated with complementary feeding. Failure to receive zinc supplementation for the treatment of diarrhoea increased nutritional risk as did having more siblings which suggests targets for improved implementation in the healthcare system. Additional investigation is emphasised for higher risk for female children in food-insecure areas.

This is one of a few studies in food-insecure areas of Ethiopia to investigate the prevalence and factors associated with child undernutrition at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and that enables us to anticipate the negative impact of the pandemic on food insecurity. Food insecurity in the study area was already alarmingly high showing 67 % of the population food insecure, out of which nearly 31 % are severely food insecure. As reported by a prior study(54), in addition to other factors the key drivers of food insecurity regarding COVID-19 include an increase in food prices, exacerbated food shortages resulting from travel restrictions, reduced agricultural production and physical distancing measures. Because of these, the pandemic may likely have a worsening effect on the existing food insecurity situation. As a result, it is logical to predict the situation becomes very severe shortly, particularly in the already food-insecure areas.

Furthermore, the ongoing desert locust outbreak should also be emphasised because it may further deteriorate food security(8). Food may become unavailable, inaccessible, and unaffordable and malnutrition may be increased in these areas. Hence, all nutrition implementers should consider all this and work on reducing child undernutrition and maybe food shortage. Similarly, the existing social protection programmes consider promoting nutritious, safe, affordable and sustainable diets that support adequate nutrition and prevent undernutrition among infants and young children in the study area and similar settings.

The limitation of the present study was the failure to collect information on variables like the seasonality of food availability, food taboos and the COVID-19 situation in the area. There may also be recall bias in reporting different food groups consumed over the previous day referring to dietary diversity score.

Conclusion

The main factors significantly associated with child undernutrition in the study area were having more siblings, lack of zinc supplement for diarrhoea, lack of child growth monitoring, inadequate diet diversity and poor income of mothers. These factors may be particularly important targets for intervention in the study population. Our finding suggests a need for initiatives focused on improving IYCF practices and diet diversity, particularly those associated with complementary feeding. Improving zinc supplementation for the treatment of diarrhoea should be taken as one intervention strategy to mitigate child undernutrition in the study area. Limiting the number of birth and improving the growth monitoring and counselling service suggests improvement in the health care system. Our result also showed the importance of involving mothers in income-generating activities for improved nutritional status of the child.

Based on the study results, child undernutrition and food insecurity situation are alarmingly high in the study area. The situation is calling the attention of the existing social security programme. Furthermore, all actors of nutrition should be prepared to handle the worsening effects of the mentioned factors on food insecurity in the area by contributing different aspects including humanitarian actions, and advocacy focusing on educating governments and the public on the importance of nutrition to people's survival. The nutrition community also has a role in advising the government on approaches to target the most vulnerable populations for safety nets and food aid in the context of reduced food access.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge study participants and data collectors. We also acknowledge Hawassa University SPIR-DFSA project for the financial support in accomplishing this paper. The authors would also like to extend their deep thanks to all individuals who contribute to this survey.

The financial support for this study came from the SPIR-DFSA learning agenda of Hawassa University funded by the United States Agency for International Development through World Vision Ethiopia. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the views of the funder.

Z. T. conceived of the study, carried out the analysis and interpretations, and drafted and edited the manuscript. A. A. helped to conceive the study and analysis and drafted and edited the manuscript. F. R. and B. M. helped with the analysis, drafting and critically edited all versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved this manuscript to be published.

The authors declare they have no competing interests in this work.

The data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The proposal gained ethical clearance from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the College of Health Sciences of Hawassa University. Participation in the study was conducted voluntarily and with oral consent, from participant mothers. Before administering the questionnaire the study participants discussed the research objective and requested permission to participate. The participants were reassured about the confidentiality of the data.