INTRODUCTION

TAZARA is the monument of the China–Africa friendship. Revitalisation of the project … signals a new era of cooperation. It means developing the railway of freedom and friendship to [sic] the railway of development and prosperity. (Then Chinese Ambassador to Tanzania, Lu Youqing, quoted in The Citizen 2017)

Half a century after breaking ground for its construction, the 1,860km-long Tanzania–Zambia Railway Authority (TAZARA), which links Zambia's Central Province with the port of Dar es Salaam, remains not only China's largest foreign aid project to date but also the single-most prominent symbol of Sino-African solidarity. China's support for the railway during Southern Africa's liberation struggle facilitated close political, economic and cultural ties among China, Tanzania and Zambia, thereby establishing what is often called an ‘all-weather friendship’. In the context of rapidly diversifying China–Africa relations, decision-makers on both sides frequently invoke the railway as proof of ‘win-win’ cooperation (合作共赢; hézuò gòngyíng).Footnote 1

Notwithstanding the profound legacy of TAZARA's construction era, China's current involvement in the ‘revitalisation’ of the binational rail company occurs in a vastly different global context. China has long outgrown its African ‘all-weather friends’ – politically and economically. Its contemporary geo-economic strategy, epitomised by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), is motivated by the need to access new markets (Taylor & Zajontz Reference Taylor and Zajontz2020; Carmody et al. Reference Carmody, Taylor and Zajontz2021). Formerly an instrument of Maoist anti-imperialism, today the chronically undercapitalised TAZARA with its dilapidated infrastructural assets provides a potential investment outlet for rapidly globalising Chinese (state) capital. As Harvey (Reference Harvey2003: 150) notes, ‘[d]evalued capital assets can be bought up at fire-sale prices and profitably recycled back into the circulation of capital by overaccumulated capital. … Valuable assets are thrown out of circulation and devalued. They lie fallow and dormant until surplus capital seizes upon them to breath [sic] new life into capital accumulation.’ Chinese surplus capital stands ready to breathe new life into TAZARA. The ‘new era of cooperation’, which China's former Ambassador to Tanzania referred to in the introductory quote, is not least driven by Chinese interests in long-term investments in African infrastructural assets and, where possible, their ownership and operation. Unsurprisingly, TAZARA's rehabilitation is considered a priority project under the BRI.

Whilst framed by the usual ‘win-win’ narrative, talks about a Chinese participation in the company have been marked by hitherto irreconcilable differences over the terms of a Chinese investment. Informed by the recent African ‘agency turn’ in Africa–China studies (Alden & Large Reference Alden and Large2019: 13), this article directs analytical attention towards the strategies pursued by the Tanzanian and Zambian governments in the 2016 negotiations with a Chinese consortium about TAZARA's rehabilitation. By employing the strategic-relational approach (SRA) it is shown that African agency in Africa–China relations is conditioned by strategically selective structural contexts. The article draws on a combination of primary and secondary data. Passive observation and interviews with Tanzanian and Zambian government officials, academics and civil society actors as well as with representatives of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were conducted in Tanzania and Zambia between 2017 and 2019.Footnote 2 Where possible, interview data were triangulated within the method by speaking to different people in different places at different times. It was also checked against information in media reports, secondary literature and official documents.

The article proceeds in four steps. First, Sino–African cooperation in the infrastructure sector is contextualised and the SRA introduced, as it transcends dualist ontologies of the structure-agency relationship that prevail in Africa–China studies. Second, TAZARA's history and politico-economic factors for its steady decline are recounted, as both form part of the strategically selective context in which the railway's rehabilitation is negotiated. Part 3 reveals factors that have informed strategic calculation and learning on the part of the shareholding governments in the negotiations. Part 4 documents how growing fiscal constraints in Zambia and the rise of autocratic developmentalism under late President Magufuli in Tanzania have affected the two governments’ strategic capacities to rehabilitate TAZARA. The article concludes that the African ‘agency turn’ in Africa–China studies could profit from closer analytical attention towards the ways in which African actors interact with their strategically selective structural environments.

THE (INFRA)STRUCTURE-AGENCY CONUNDRUM

Since the turn of the millennium, infrastructure has made a comeback in economic policymaking and development planning in Africa (Zajontz & Taylor Reference Zajontz, Taylor, Oritsejafor and Cooper2021). This trend has been fostered by the emergence of a global ‘regime of infrastructure-led development’ in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis (Schindler & Kanai Reference Schindler and Kanai2021), which has caused a ‘Global Race to Build Africa's Infrastructure’ (Gil et al. Reference Gil, Stafford and Musonda2019). A widespread assumption is that the renewed interest in African infrastructure markets and the resultant diversification of infrastructure financiers beyond the ‘traditional’ Western and multilateral sources have provided African governments and regional organisations with more leeway to steer economic development (see Soulé Reference Soulé2020; Links Reference Links and Schneider2021). Especially Chinese finance is seen as a welcome ‘gap filler’ in Africa's infrastructure sector (Goodfellow Reference Goodfellow2020; Zajontz Reference Zajontz2021).

As elaborated elsewhere (Zajontz Reference Zajontz2020b; Carmody et al. Reference Carmody, Taylor and Zajontz2021), Chinese loan-debt investment in Africa's infrastructure sector has been part of Beijing's efforts to address mounting overaccumulation post-2008. Meanwhile, Chinese involvement in Africa's infrastructure sector is no longer confined to loans and export credits from China's policy banks which are usually tied to Engineering-Procurement-Construction (EPC) contracts for Chinese companies. Both Chinese SOEs and private firms are increasingly seeking opportunities to invest in and/or operate African infrastructure by means of public-private partnerships (PPPs) (Alden & Jiang Reference Alden and Jiang2019; Zajontz Reference Zajontz2020b). This trend is likely to solidify considering that servicing sovereign debt for large-scale infrastructure has become increasingly burdensome for some governments, as in the cases of Kenya's and Ethiopia's Chinese-funded railways (Carmody et al. Reference Carmody, Taylor and Zajontz2021; Zajontz Reference Zajontz, Cope and Ness2022).

In light of mounting public controversies about the questionable economic viability of some infrastructure projects, the issue of debt sustainability and frequent allegations of corruption in tender processes, Mohan & Tan-Mullins (Reference Mohan and Tan-Mullins2019: 1370) are right in pointing to the role of political elites in brokering infrastructure deals: ‘The interaction between Chinese state-backed actors and the agency of Southern political elites shapes how infrastructure is financed, funded and utilised, which are ultimately questions of “who benefits?”’. Yet, if not appropriately conceptualised, there is a risk to reduce African state agency to elite agency and to misconstrue actions of political elites and officials as detached from state-society relations, historically specific state forms and wider political-economic structures. This analysis thus draws on the SRA which situates politicians, state officials, governments and bureaucracies firmly within the wider structural context of the state. Jessop (Reference Jessop2016: 56) notes that ‘[a]lthough these “insiders” are key players in the exercise of state powers, they always act in relation to a wider balance of forces within and beyond a given state’.

The SRA helps us to transcend ‘rather static and one-dimensional concept[s] of agency’ (Carmody & Kragelund Reference Carmody and Kragelund2016: 5) which have characterised the African ‘agency turn’ in Africa–China studies. The bulk of research has remained surprisingly unconcerned with structure-agency dialectics and has relied on voluntarist conceptions of agency which ultimately fail to explain how agents are differentially affected by their structural contexts. Most attempts to counter crudely structuralist narratives of an all-powerful China, which supposedly sets the ‘rules of the game’ and deprives African actors of their agency, have remained confined to a methodological move towards analysing African actors and practices. Whilst we now have empirically rich accounts documenting the variety of ‘African agency’, theory-informed analyses of how the latter interrelates with structural contexts over time and in particular spatio-temporal conjunctures are rare (for a notable exception, see Lampert & Mohan Reference Lampert, Mohan and Gadzala2015). Structural constraints are occasionally mentioned but seldom integrated into conceptualisations of African agency. Structuralist reductionism has been countered by accounts of agency that are void of structure. Links (Reference Links and Schneider2021:115–16) recognises this when referring to agency as ‘both the act of holding specific interests and goals as well as the capacity that actors possess to set agendas, negotiate, and act in accordance with their specific interests and goals. Power then, is not a focal or defining characteristic of agency but is closely related to structure’. Hence the apposite call for a ‘contextual approach … that considers the contours and specificities of African agency’ (Links Reference Links and Schneider2021: 124). Such an approach must transcend the conceptual structure-agency dualism that has thus far characterised the African ‘agency turn’.

The SRA treats agents as ontologically inseparable from their structured social contexts. It relates structures and agents dialectically with the help of strategy as a second-order concept (Hay Reference Hay2002: 127–8). Social structures are conceptualised as strategically selective in that they ‘may privilege some actors, some identities, some strategies, some spatial and temporal horizons, some actions over others’. Agents, in turn, act (or refrain from acting) upon ‘structurally-oriented strategic calculation’ with the aim of realising certain objectives (Jessop Reference Jessop2005: 48). Hence, the SRA ‘identifies a strategic actor within a strategically selective context’ (Hay Reference Hay2002: 128). By implication, any analysis of agency requires a (diachronic and synchronic) analysis of structural contexts within and towards which strategies are formulated (Hay Reference Hay, Hay, Lister and Marsh2006: 75).

Crucially, structural contexts only ever tendentially impose biases towards the selection or rejection of certain strategies (over others). The actualisation of specific biases is contingent upon their interaction with other structurally inscribed strategic selectivities and the strategic capacities of specific agents in specific conjunctures (Jessop Reference Jessop2006: n.n., Reference Jessop2016: 55). In the recursive interaction between strategic actors and their strategically selective environments, ‘strategic learning’ becomes essential, as actors try to enhance their awareness of structural constraints and opportunities and adjust their strategies in order to maximise the chances to modify structures (Hay Reference Hay2002: 133; Jessop Reference Jessop2005: 51). This implies a ‘processual’ and ‘evolutionary’ dimension of the structure-agency relationship, as it incorporates a logic of path-dependency, in terms of ‘inherited structures and strategic capacities’, and a logic of path-shaping, in terms of the ‘modification of structures and capacities’ (Jessop Reference Jessop2006: n.n.).

The case of TAZARA was theoretically sampled, thus considered instructive regarding the structure-agency conundrum. The railway's history has created path-dependencies in terms of a densely structured action context, whilst the binational ownership of the company allows for an analysis of distinct structural constraints/opportunities and strategic capacities of two shareholding governments. Aspects of path-dependency are assessed in the following section by documenting how the longstanding cooperation amongst the Chinese, Tanzanian and Zambian governments in building and maintaining TAZARA has brought forth a context of action marked by dense historical, political and institutional relations with limiting effects on the shareholding governments’ strategic choices in the negotiations. Constraints have also arisen from previous strategic (in)action on the part of the shareholding governments in the operation, management and maintenance of TAZARA. Inefficient and politicised management structures, chronic underinvestment and the company's indebtedness form part of the strategically selective structural context in which TAZARA's rehabilitation is negotiated.

The subsequent section takes a closer look at the preferred rehabilitation strategies that the negotiating parties pursued as well as at key considerations in the ‘“strategic context” analysis’ (Jessop Reference Jessop2016: 55) of the Tanzanian and Zambian governments. Strategic calculation on the part of public authorities when negotiating PPPs is commonly marked by economic, political and social cost-benefit analyses. In the concrete case, the latter are documented with the help of interviewees’ appraisals of the financial terms and fiscal consequences of the Chinese proposal and of proposed retrenchments. Strategic learning depends on actors’ reflexivity about failures and successes of past strategic actions, in the concrete case previous railway privatisations. Moreover, actors’ awareness of the structural context of action and of (perceived) interests pursued by other actors – in the concrete case the Chinese investor – determines actors’ learning capacities.

Essential to the notion of strategic selectivity is that the extent to which structures constrain or enable actors differs from actor to actor (Jessop Reference Jessop2006: n.n., Reference Jessop2016: 55). The last part of the paper examines how the two shareholding governments have been differentially constrained/enabled by their respective structural context. Their strategic capacities refer to their ability to determine the conditions under which TAZARA is rehabilitated. As will be shown in the Zambian case, rehabilitating a highly indebted and chronically underfunded railway is crucially dependent on the availability of public financial resources. Tanzania's strategy in turn has shifted as a result of a changing balance of political forces in Tanzanian politics.

THE MONUMENTAL RISE AND STEADY DECLINE OF THE ‘FREEDOM RAILWAY’

The construction of TAZARA and China's decisive role in this endeavour were prompted by geo-political and geo-economic developments in the region. At independence, Zambia had been fully integrated into the political economy of colonial Southern Africa and its regionalised networks of trade, migration and infrastructure for over a century. This closely tied the country to South Africa, Rhodesia and Mozambique for the import and export of commodities and for the provision of labour (Niemann Reference Niemann2000: 102–6; Söderbaum Reference Söderbaum2002: 62). Zambia's economic vulnerability became blatant upon Rhodesia's unilateral declaration of independence in 1965 which caused a ‘transportation emergency for landlocked Zambia’ during which oil and other essential goods needed to be airlifted into Zambia (Monson Reference Monson2009: 23). Zambia was almost exclusively dependent on copper exports, which amounted to 97% of its forex earnings in 1969. Its main export route went through Rhodesia for which the transit of copper was an important source of foreign exchange (Rettman Reference Rettman1973; Sklar Reference Sklar and Tordoff1974). The Tanzanians for their part expected the railway to boost agricultural production in the country's fertile south-west. Both presidents Kaunda of Zambia and Nyerere of Tanzania ‘envisioned a post-colonial transportation infrastructure that would be based upon regional cooperation rather than colonial dependency’ (Monson Reference Monson2009: 15).

Tanzania and Zambia sought support from several Western governments, the Soviet Union, the World Bank, the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the mining multi-national Lonhro – without success. China first offered its support during Nyerere's China visit in 1965 (Gleave Reference Gleave1992; Lusinde Int.). A tripartite agreement was signed in Beijing in 1967, followed by surveys and planning regarding the route (Monson Reference Monson2009: 24). Job Lusinde, the Tanzanian minister in charge of the transport and works portfolios between 1965 and 1975, remembered a conversation with Nyerere: ‘From what Mwalimu [Nyerere] told me, Mao Zedong asked them [Nyerere and Kaunda] one question: “Would that [construction of a railway] assist the liberation of Africa?” And the answer was: “yes”. And the reaction was: “It will be built”. Just like that’ (Lusinde Int.).

In 1969, the governments signed a finance agreement over ¥988 million (about $415 million at the time) (Monson Reference Monson2009: 30). Construction commenced in the latter half of 1970 and tracklaying was completed in mid-1975. The railway was officially commissioned in July 1976. TAZARA's design capacity was 2.5 million tons per annum and per direction and its initial operating capacity 2.16 million tons (Gleave Reference Gleave1992: 255). However, its actual performance has remained far below its capacity, with its peak performance of 1.27 million tons being recorded in 1977/78 (see Figure 1). China's involvement in building the ‘Freedom Railway’ – Reli ya Uhuru in Swahili – was steeped in an anti-imperialist narrative which emphasised Sino–African solidarity based on the shared legacy of colonial subjugation and anti-imperial struggles (Monson Reference Monson2009: 3, 6, 26–27; Scott Reference Scott2019: 182). Simultaneously, China sought to establish diplomatic relations with newly independent African states and to secure support for the Chinese bid for UN membership and a Security Council seat (Rettman Reference Rettman1973: 237).

Figure 1 Cargo conveyed by TAZARA, 1976–2019

Source: Author's compilation, based on TAZARA data.

The funding arrangement was informed by Zhou Enlai's Eight Principles for Economic Aid and Technical Assistance to Other Countries (Monson Reference Monson2009: 30). Principle 3 states that ‘China provides economic aid in the form of interest-free or low-interest loans and extends the time limit for the repayment when necessary so as to lighten the burden of the recipient countries as far as possible’ (PRC 1964). China has lived up to the principle by having repeatedly rescheduled loan repayments. In 2011, another $150 million in debt from the initial loan was written off (Liu & Monson Reference Liu, Monson, Dietz, Havnevik, Kaag and Oestigaard2011: 229 n.2). The Eight Principles also stipulated that China's aid policy should strengthen the ‘self-reliance’ of recipient countries (PRC 1964). China's approach to development aid was cherished by Nyerere: ‘Africa was, and is still, not used to getting assistance on such terms. Yet, there has been no hidden cost, and no concealed string, to this aid’ (Nyerere Reference Nyerere2015: 65). Since the construction, China has supported TAZARA by means of hitherto 15 Protocols of Economic and Technical Cooperation. The trilateral protocols have been implemented by a team of staff from China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC)Footnote 3 that is permanently seconded to TAZARA, the Chinese Railway Expert Team (CRET).Footnote 4 Recent protocols primarily aimed at ameliorating TAZARA's shortage in rolling stock, locomotives, spare parts and equipment (Key informant A Int.).

China's longstanding involvement in the railway has created path-dependencies which have impacted the shareholding governments’ strategic scope regarding TAZARA's rehabilitation. In the words of one interviewee, Chinese investors were seen to hold the ‘right of first refusal’ and were given ‘priority, because they are the ones who constructed this’ (Key informant B Int.). A Tanzanian academic reasoned that the history and symbolic significance of TAZARA effectively forbid the consideration of a non-Chinese investor (Kamata Int.). A Chinese interviewee argued that ‘no one can compete with CCECC’ for the rehabilitation, as they were the only ones who had the plans from the construction period (Chinese journalist Int.). In conceptual terms, past strategies and interactions have brought forth a strategically selective context which tendentially limits investor selection to Chinese firms. Other structural constraints have arisen from past strategic (in)action and TAZARA's steady decline.

The devaluation of a monument

TAZARA's performance first took a hit following the partial re-opening of southern transport routes in October 1978, which caused a significant drop in the share of Zambia's foreign trade that travelled along the Dar es Salaam corridor (Mwase Reference Mwase1987; Gleave Reference Gleave1992). Yet, more detrimental was the liberalisation of African economies in general and the transport sector in particular. As funding for large public infrastructure had started to dry up by the late-1970s, African railways became subject to a ‘steady process of attrition’ (Nugent Reference Nugent, Schubert, Engel and Elisio2018: 22). In Zambia and Tanzania, the conjuncture of economic stagnation, rising sovereign debt and resultant policy straitjackets imposed by structural adjustment programmes further limited the shareholding governments’ capacity to maintain TAZARA's infrastructure and rolling stock. As an exception to the chronic lack of investment, TAZARA, in 1985, received capital injections totalling $150 million as part of donor-funded aid projects. The resultant capacity increase in rolling stock, alongside the involvement of Chinese experts in the ‘cooperative management’ of TAZARA, led to recovering freight volumes and passenger numbers in the late 1980s (Liu & Monson Reference Liu, Monson, Dietz, Havnevik, Kaag and Oestigaard2011: 240).

The recovery was short. TAZARA's decline continued during the privatisation of Zambia's mining sector between 1992 and 2000, which entailed the end of the ‘symbiosis’ between state-owned Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines and TAZARA. Henceforth, an increasing share of copper was transported by road, both along refurbished southern routes and the TANZAM Highway. Inefficiencies, capacity constraints, long dwell times and high fees at Dar es Salaam port further compromised TAZARA's competitiveness (World Bank 2013: x, 27, 31; Zambian senior official Int.). Simultaneously, clientelistic networks of Tanzanian politicians and business people involved in road haulage along the Dar corridor greatly profited from TAZARA's decay and, hence, had little interest in reversing it (Scott Reference Scott2019: 183).

Besides external political and economic factors, TAZARA has faced challenges that arise from its institutional set-up. Former transport minister Lusinde explained that ‘our structure, our administration, I think was wrong from the beginning and it was never changed. The management that was built up was mainly political, it was not technical’ (Lusinde Int.). Political ‘interference’ has been the order of the day, as one interviewee confirmed:

I'm sure you understand the politics of parastatals. Especially parastatals in Africa – state-owned enterprises. There are quite some politics. You cannot distance yourself from the government or from the politicians. So, it's always a problem. So, what makes it particularly challenging is that we have two governments with two different interests at any given time. (Key informant B Int.)

TAZARA's decade-long devaluation is reflected in its economic performance. Cargo levels reached a new all-time low in the financial year 2014/15 when it transported a mere 87,860 metric tonnes. To put the number in perspective: in 2015, 2.5 million tonnes of cargo left Dar es Salaam port for Zambia (Domasa Reference Domasa2016). According to the Zambia Chamber of Mines, Zambia produced 711,515 tonnes in copper alone (Hill Reference Hill2016). TAZARA's performance has gradually improved in recent years, with cargo volumes averaging 174,000 tonnes in the four financial years following the negative record. The number of ‘speed restricted zones’ could be reduced from 50 to less than 20 (Key informant B Int.). While cargo trains occasionally needed up to 21 days in 2006, which ‘scared a lot of clients, they ran away’ (Key informant B Int.), the transit time between the termini decreased to an average of 6.6 days in 2017/18 (TAZARA 2018: 7) and averaged four days in February 2019 (Key informant B Int.).

Notwithstanding these improvements, TAZARA still faces serious infrastructural and operational challenges, such as an outdated and inoperative signalling system. Severe limitations in rolling stock pose a major challenge for meeting market demands. In February 2019, the company was operating ‘with just about twelve locomotives’ daily. To reach its estimated breakeven point of 600,000 tonnes of cargo, the enterprise would need at least 20 locomotives (Key informant B Int.). Moreover, the company is highly indebted, with outstanding liabilities amounting to $800 million (Key informant B Int.; TAZARA labour union executive Int.). A senior Zambian official acknowledged that

TAZARA hasn't had as much a good share of investment. Most of the investment … over the years have been the Chinese protocols on one side, which largely focused on the Chinese providing equipment or selling us spare parts. The financing from both governments – Tanzania and Zambia – has largely been focused on paying salaries and that is basically a way of quieting the workers. But then the investments that are required to be able to make the company viable and vibrant were not being looked at. (Zambian senior official Int.)

Past strategic (in)actions, such as chronic underinvestment, and inherited structures, such as TAZARA's dysfunctional and politicised corporate structure, have crucially informed the strategically selective structural context of the 2016 negotiations. Following from China's longstanding involvement in TAZARA and the company's poor economic situation, this structural context is tendentially biased towards the privatisation of the company to a Chinese investor. To what extent such structural biases actualise depends on the reflexivity of the shareholding governments as well as on their differentially constrained strategic capacities.

STRATEGIC CALCULATION AND LEARNING: NEGOTIATING WITH THE ‘CHINESE OF TODAY’

As a result of TAZARA's ailing condition, the shareholding governments approached their Chinese counterpart to determine options to rehabilitate the railway. In March 2012, the three governments signed a protocol which provided for a feasibility study for the ‘Renovation Project of Tanzania–Zambia Railway’. The study was assigned to the Chinese state-owned Third Railway Survey and Design Institute Group Corporation (TSDI) and released in May 2016 (TSDI 2016: 2). It inter alia recommends ‘that the government [sic] of Tanzania and Zambia enact appropriate laws and create an agreeable commercial environment for the future development of Tanzania–Zambia Railway so as to attract investment and improve the management level’. Total investment required was estimated at $370 million (TSDI 2016: 230). The study foresees the closure of nine of TAZARA's remaining 57 stations, five in Tanzania and four in Zambia (TSDI 2016: 31; Key informant B Int.).

Negotiations resumed in May 2016 when a technical committee met to explore options on the basis of the TSDI study. The Chinese delegation was headed by Liu Junfeng, Deputy Director General of the Ministry of Commerce, while Zambia was represented by Secretary to the Cabinet, Rowland Msiska, and Tanzania by Chief Secretary at the State House, John Kijazi. In a post-meeting working document, which is quoted in The Citizen, ‘[t]he Chinese, Tanzania[n] and Zambian sides all agree that the current form of management and operation shall be changed and commercial operation shall be introduced to realise the revitalisation and sustainable development of Tazara’. Furthermore, ‘Tanzania and Zambia will do their best to ensure Tazara is provided with preferential policies and legal instruments to make it commercially viable’. Reportedly, the document also proposes the downsizing of the TAZARA workforce (The Citizen 2016; italics added).

According to a Tanzanian top official, three options to rehabilitate TAZARA were ‘on the table’: ‘Concession, management contract or complete rehabilitation by the shareholding governments’. The interviewee claimed that, whilst the Tanzanian government ‘left all the three options open’, rehabilitation by means of own resources was financially unfeasible for Zambia (Tanzanian top official Int.). As a result, the two shareholding governments ‘had both agreed that what would be best for TAZARA is a management contract’ (Key Informant B Int.; also Zambian Senior Official Int.). Management contracts are short-term (3–5 years) PPPs in which ownership and capital expenditure remain with the public authority, whereas operation and maintenance are handled by a private contractor. The latter is compensated through set management fees (Farquharson et al. Reference Farquharson, Torres de Mästle, Yescombe and Encinas2011: 10).

The Chinese side proposed a Rehabilitate-Operate-Transfer (ROT) PPP instead.Footnote 5 A CCECC executive explained that, for the Chinese side, the ‘key question’ had been whether to invest in rebuilding or in mere maintenance, with either ‘big money’ or ‘little money’ being spent. The Chinese government preferred a major investment with a time horizon of 30 years, which would aim at ‘refresh[ing]’ and ‘rebuilding TAZARA only once’, over short-term capital injections towards the maintenance of the railway (CCECC executive Int.). The Chinese preference was reflected in the institutional set-up for the intergovernmental negotiations. The Chinese government set up an advisory working group which was steered by China Railway. As a Chinese interviewee reasoned, China Railway ‘has the experience of running railways. That's why they were chosen … by the Chinese government to be the leading company in that joint working group’. Other members were CCECC (on behalf of its parent company China Railway Construction Corporation), TSDI and China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation (Key informant A Int.).

The Chinese proposal anticipated a contract duration of 30 years and provided for the injection of $380 m. As a precondition for investment, the Chinese consortium expected the shareholders to assume TAZARA's outstanding debts, which amounts to ‘no less than 800 million dollars’ (Key informant B Int.). A Tanzanian official with direct knowledge of the negotiations confirmed that ‘one of the terms was to clear out the balance sheet of TAZARA’. The interviewee argued that the offer made little economic sense for the Tanzanian government: ‘If you have the capacity of doing that, why do you find someone else? … If you were to pay all the debt before someone thinks of [a] concession, then you can as well do it yourself’. The interviewee stated that the Zambian government equally considered it impossible to take on TAZARA's debts (Tanzanian top official Int.). Another interviewee suggested that the Chinese side used TAZARA's debt and other financial liabilities towards suppliers and (former) employees as a ‘negotiation tool’ (Key informant B Int.).

Further controversy was caused by the Chinese request for tax concessions to make an investment economically feasible. In its financial appraisal, the TSDI concludes that ‘[t]he financial internal rate of returns of project investment is below zero and the financial benefit of the project is poor. The government of the three countries should provide certain support, so as to provide [a] powerful guarantee for the financial viability of the project’ (TSDI 2016: 257). The study presupposes the continuation of tax abatements after the privatisation: ‘In view that Tanzania–Zambia Railway is the project aided by China, and it shall be [a] tax-exempt[ed] project. In this study, it is considered that Tanzania–Zambia Railway still has income tax immunity rights’ (TSDI 2016: 255). Interviewees confirmed that the Chinese negotiators demanded tax holidays and subsidies until TAZARA could be run profitably, which according to their projections could take 15–20 years. The Chinese calculated the break-even point above 1 million metric tonnes of cargo per annum, whereas TAZARA projects the same at 600,000 tonnes (Key informant B Int.; Tanzanian official Int.). According to one interviewee, the differing bases of calculation were ‘the gist of the matter’. The official recalled that ‘the numbers were very, very different – what they had and what we had. So, we said: “No, we cannot discuss on these particular terms. When we are saying that on this basis we break even at 600,000 tonnes and then you [referring to the Chinese investor] are saying 1.2 [million tonnes]”’ (Tanzanian top official Int.).

Whilst tax exemptions and state subsidies are a common instrument to ensure profitability of infrastructure PPPs (see Hildyard Reference Hildyard2016: Ch. 3), the Chinese demands were considered disproportionate. One interviewee described the demand for tax holidays ‘as a trick or rather as a tactic to evade tax’. The interviewee also argued that it was the Tanzanian government which deemed far-reaching tax exemptions unacceptable, stating that ‘if you are a nationalist [referring to late President Magufuli] you ask the question: So, why should I bring this company from China? Why should they come? They are saying, they don't want to pay tax. They will not pay tax for 15, 20 years’ (Key informant B Int.).

The future of TAZARA's workforce also played a central role in the shareholders’ strategic calculation. The Chinese proposal was to retrench the entire workforce and to recruit under new contracts. An official stated that the investor expected the shareholding governments to defray the costs related to the retrenchment. The interviewee underscored the political sensitivity of the issue: ‘If you touch someone, retrench workers, you have political chaos’ (Tanzanian official Int.; also Key informant B Int.). Job Lusinde, who supervised TAZARA's construction as Minister of Transport, underlined this assessment: ‘What will happen to the African workforce? Are you going to remove all the managers and bring in Chinese? You are looking for trouble’ (Lusinde Int.). As past rounds of retrenchments have shown, the TAZARA workforce has traditionally been strongly identified with the company and proven ready to defend their jobs (Liu & Monson Reference Liu, Monson, Dietz, Havnevik, Kaag and Oestigaard2011: 242; Monson Reference Monson2013: 56–57; Shivji Int.).

Strategic calculation on the part of both shareholding governments has been crucially informed by previous failed railway concessions. In 2000, Zambia embarked on a World Bank-sponsored privatisation of Zambia Railways which quickly resulted in contentions over agreed investment plans and financial targets. The concession was terminated under President Sata in 2012 (Bullock Reference Bullock2005: 23; AfDB 2015: 189). A Zambian interviewee emphasised the importance to avoid mistakes made in the context of previous railway concessions through which ‘both countries got burnt’. The objective would be to ‘negotiate a better deal than we did last time’ and ‘to learn from our previous concession. Just because the previous concession went bad, it doesn't mean concession is a bad thing in itself’ (Zambian senior official Int.). The interviewee also underscored the political sensitivity of a Chinese participation, stating that ‘TAZARA's concessioning [must] not look like they are giving it away to the Chinese but allowing the Chinese to invest into it’ (Zambian senior official Int.).

The unsuccessful privatisation of Tanzania Railways Corporation (TRC) in the 2000s equally affected the strategic calculation of the Tanzanian government. Soon after both freight and passenger services had been privatised, disputes about the maintenance of assets, wage increases and the underperformance of the newly established Tanzania Railway Limited resulted in the cancellation of the concession by the government in 2010 (World Bank 2014: 5; AfDB 2015: 181, 184). A senior official acknowledged that

it was not a very good lesson that we had when we concessioned TRC. And we don't want to repeat the mistakes that have been done. So, we keep on improving – even the quality of negotiation is not the same. We look into other parameters which maybe were not considered previously. But the bottom line is the national interest is primary now to our negotiations. … We learned a lot in terms of concession arrangements. … Are we going to gain much more compared to the situation we have now? Or are we going to enter into huge debts that again will come back for the government to service? Because that is what happened when we concessioned TRC. So, we are a bit hesitant because we are conscious of the bad experience that we had. (Tanzanian senior official Int.)

The relatively recent instances of early terminated railway concessions have affected the Chinese negotiation strategy. The terms of the Chinese ROT proposal clearly aimed at maximising investment security and profitability. Simultaneously, a Chinese interviewee was fully aware of the political sensitivity of railway privatisations in both countries: ‘Both governments are claiming that according to their experience, concession for a railway is not going to work. Because the concessionaire … is always focusing on its own profits. It will not be interested in invest[ing] in the railway itself. That's the major barrier for the two governments’. The interviewee mentioned that: ‘For [the] Chinese side, it seems we don't want to call it concession. We call it – how to say? It's like a kind of BOT [contract] – I mean we do the rehabilitation, we operate for some time and then transfer’ (Key informant A Int.; for a distinction, see note 5).

Despite such tactical reframing, Mohan (Reference Mohan2013: 1260) rightly reminds us that ‘the Chinese firms central to its internationalization are capitalist, thus we have to acknowledge the accumulation imperative in any relationship with African actors’. Officials involved in the negotiations have proven highly ‘context-sensitive’ (Jessop Reference Jessop2005: 48) regarding broader politico-economic transformations and the commercial interests of globalising Chinese (state) capital. One senior official explained that the Chinese

have a long history when it comes to TAZARA. And I would say they are not ready to give it up. Because it's part of their history when it comes to Chinese–Africa relations. … That's the first project that they have done. So, they don't want to lose it. They want to be part of TAZARA. But Chinese of that time are not Chinese of today. That's the problem. They are very much different and Chinese of today they are business-minded. And business is not bad, but we are also saying that we should be able to benefit from whatever kind of arrangement that we are going to agree [on]. Benefits should not always be on their side. We should share. Maybe we might be seen as not cooperating, but we also want to benefit. (Tanzanian senior official Int.)

Overall, the terms put forward by the Chinese consortium were considered ‘not workable’ by the shareholding governments (Tanzanian top official Int.). One interviewee argued that the Chinese proposal ‘does not make economic sense, unless somebody is just desperate to get involved’. The interviewee equally emphasised the (perceived) difference between China's historical and contemporary interest in TAZARA:

The China that we are dealing with today is not the same China that we were dealing with 40 years ago. It's a different China. These are capitalist-oriented Chinese. They want to make money. The way they are driving this thing [TAZARA's rehabilitation] is to make sure they maximise their benefits. They are not saying: “We are just helping TAZARA”. No, they want to make money. … What they've been proposing is way too much. What they've been asking for is way too much. (Key informant B Int.)

Whilst the shareholding governments acted in agreement when rejecting the Chinese proposal, their leeway to rehabilitate TAZARA is affected by distinct structural constraints and strategic capacities.

DIFFERENTIAL CONSTRAINTS AND STRATEGIC CAPACITIES IN A BINATIONAL RAILWAY

Although officials have emphasised unity between Tanzania and Zambia regarding TAZARA's rehabilitation, the two shareholding governments have been differentially constrained/enabled by distinct structural contexts, which in turn has resulted in strategic divergencies. One interviewee underscored this vividly when stating that, whereas the Tanzanian leadership is ‘very careful’ and thus ‘it is not easy to sell that idea [ROT proposal] from China in Tanzania’, the Zambian government has advocated a ROT PPP for fiscal reasons:

We have a new president [Magufuli] and the politics, again, they play a big part in the life of TAZARA. He is a nationalist. He says: “Tanzania first. What am I going to benefit from this? I bring in a foreign company to come and manage this company [TAZARA]. I take out all my employees, all my nationals, I have to pay them and then they bring in 400 million dollars. I spend 800 million to clean this company and then this new company comes with 400 million dollars. What's the point?” So, that's the sticking point. This guy [Magufuli] has said: “No, it cannot work”. But on the Zambian side, they have said: “No, no, no, let's [do it] – this company is too much of a drain on our coffers. … The money that they want us to invest – we don't have money for reinvestment. So, let's bring in a private [investor] – let's bring the Chinese.” (Key informant B Int.)

Correspondingly, a CCECC executive confirmed that the differences between the Chinese consortium and the Zambian government have been smaller than between the Chinese investors and the Tanzanian administration (CCECC executive Int.).

This last section focuses on two crucial developments within the structural context of the Zambian and Tanzanian states respectively, which affected the governments’ strategic capacities. First, it is shown how Zambia's deteriorating financial situation has compromised the government's strategic scope. Second, political and institutional changes under late President Magufuli have resulted in strategic attempts to rehabilitate TAZARA on Tanzanian terms.

The constraining effects of debt: TAZARA as ‘a drain on Zambia's coffers’

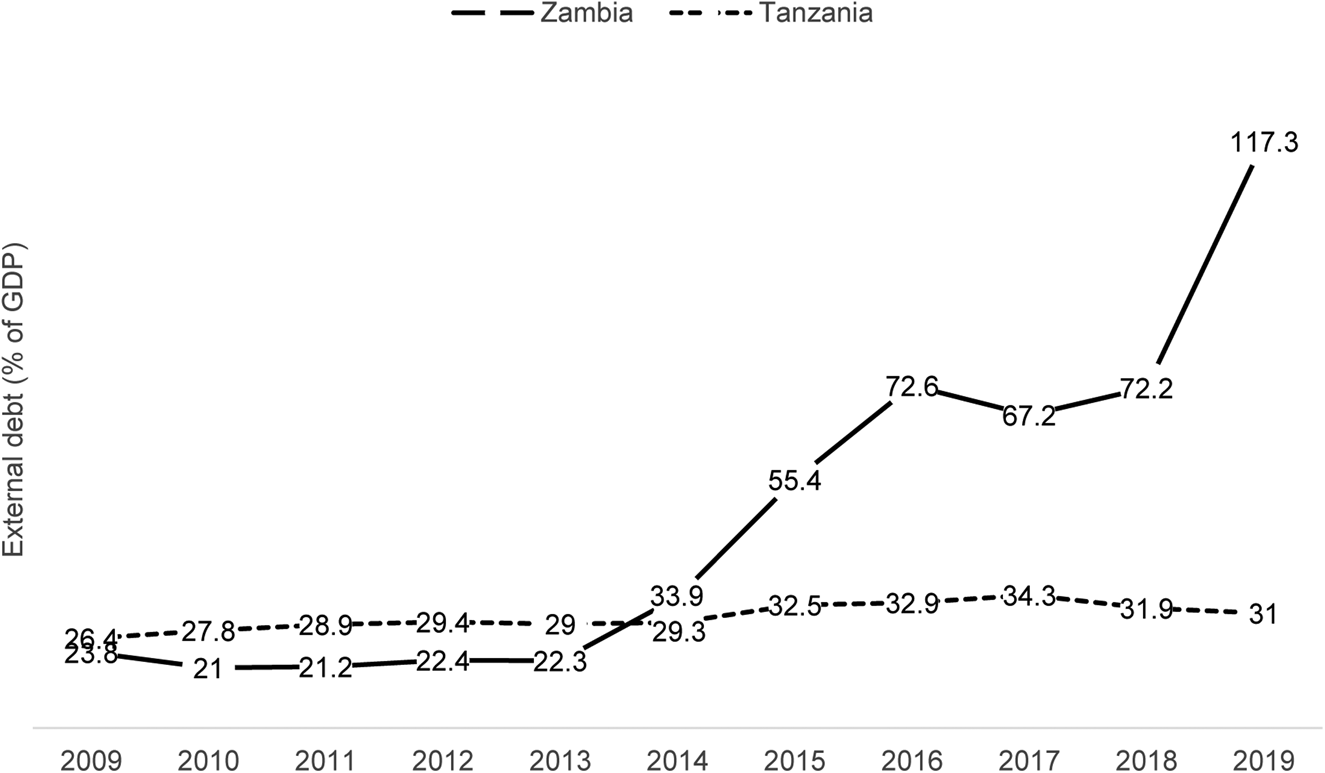

The strategic capacities of the Zambian government have been severely constrained by the country's rapidly deteriorating financial situation. After most of Zambia's external debt was forgiven as part of the Highly Indebted Poor Countries initiative in the mid-2000s, the Zambian state opted for expansionist fiscal policies and embarked on an ambitious, debt-financed ‘development-through-infrastructure’ agenda after a change in government in 2011 (Zajontz Reference Zajontz2020b). Besides signing Eurobonds to the tune of $3 billion between 2012–2015, the Zambian government contracted Chinese loans and export credits worth $9.3 billion between 2010–2019 (compared with $620 million between 2000–2009) (CARI & GDPC 2021). Figure 2 compares Zambia's and Tanzania's external debt as a percentage of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Zambia's shrinking fiscal space has translated into diminishing strategic scope regarding TAZARA's future. Despite Zambian officials’ reflexivity about the failed privatisation of Zambia Railways (and the resultant preference for a management contract), the government's ‘ability … to put lessons learnt into practice’ (Jessop Reference Jessop, Leicht and Jenkins2010: 49) has been compromised by limited financial resources which would allow for viable alternatives to a ROT PPP. In the words of a Zambian official, the Chinese dismissal of a management contract resulted in a situation in which ‘now we [Zambian government] have to go and convince our Tanzanian colleagues that “look, maybe we are better off having to concession this thing [TAZARA]”’. For the interviewee, Zambia's ‘fiscal constraints’ speak for a TAZARA concession for 20–25 years which should guarantee fixed investment sums, employment guarantees and technology transfer. The official further reasoned:

Concerning the constraints the economy has right now and the fiscal space we are better off concessioning TAZARA. Otherwise, with about 1.2 billion, 1.6 billion dollars of fiscal space for borrowing – if you take in 200 million dollars for TAZARA and another 200 million for Zambia Railways, you are close to 30 per cent of the fiscal space. So we have to think a bit more outside the box and see how the private sector could help us … Plus having the Chinese clean up the institution [TAZARA] for us to a level where moving forward would be much easier. (Zambian senior official Int.)

Due to lack of funds, the Zambian government has struggled to invest in TAZARA. In 2017, the company's governing bodies had agreed that each government would inject $5 million over a period of two years for urgent maintenance. Whilst the Tanzanian treasury released the funds, the Zambians did not (Key informant B Int.). A Tanzanian official likened TAZARA's situation to that of a ‘stepson’, whereby ‘every parent needs to make sure that the other parent puts in equally’ (Tanzanian official Int.). This has not been the case in recent years due to Zambia's budgetary constraints (Tanzanian senior official Int.; Tanzanian official Int.).

As a result of TAZARA's deteriorating performance, non-payment of salaries has become a regular source of quarrel between the company and its trade unions, who have endured non-payment of salaries for up to five months (TAZARA labour union executive Int.). The situation culminated in a strike in January 2015 which brought the railway to a standstill for more than a week. To avoid further strikes, the two governments decided to take over the company's wage bill. While the Tanzanian government has since fulfilled its commitments, its Zambian counterpart delayed salary payments for several months in 2017 (TAZARA labour union executive Int.). In April 2019, unionised TAZARA workers in Zambia went on strike, as the Zambian government had again not paid salaries for four consecutive months (The Mast 2019).

Lacking both borrowing capacity and fiscal room for investments, the Zambian government has recently shifted towards project finance PPPs as the preferred alternative to finance infrastructure (Zajontz Reference Zajontz2020b). This strategic shift is well exemplified in a statement by then Minister of Transport and Communication, Brian Mushimba, who commented on media reports which, in August 2018, falsely suggested that TAZARA had been privatised:

Here is a true story; we as PF [Patriotic Front] government, we are desirous to make sure that Tazara and Zambia [R]ailways are revamped. … [W]e look at all the options that are available to us. One option is borrowing, which is debt. You know how many people have raised concerns about borrowing and debt? The same people that brought this story, they are the same people that are screaming about borrowing and debt! So, we don't want to borrow. … So, in the discussions around how we will revamp and raise resources for TAZARA, the conversation came up to say “how about a concession to the Chinese?” They know TAZARA, they know how it was constructed, they know its gaps, they have money. They want to use TAZARA to move some of their cargo, so can't we create a win-win situation with the Chinese? (Quoted in Mbewe Reference Mbewe2018)

With the country's fiscal room to manoeuvre to reinvest in TAZARA shrinking, a long-term concession to a Chinese investor has been considered indispensable by the Zambian government. However, the privatisation has hitherto been averted by a divergent strategy pursued by the other shareholder, the Tanzanian government.

Strategic scrutiny of an ‘economic patriot’: rehabilitating TAZARA on Tanzanian terms

Most importantly, we must seize control of our economy and destiny. This will require courageous leadership, self-confidence, ingenuity, hard work and economic patriotism. (Magufuli Reference Magufuli, Mufuruki, Mawji, Marwa and Kasiga2017: viii)

The strategy pursued by the Tanzanian government during and after the 2016 negotiations was crucially informed by the changing balance of political forces leading up to late President Magufuli's election in 2015. Reacting to growing discontent, both within the ruling party and the population, over insufficient benefits from foreign investments, the Magufuli administration aligned economic policies with resource nationalism and an autocratic developmental state approach. Magufuli famously earned himself the nickname ‘Bulldozer’ due to his uncompromising anti-corruption campaign, rigid government interventions vis-à-vis foreign investors and repression of the political opposition, the media and civil society (see Andreoni Reference Andreoni2017; Polus & Tycholiz Reference Polus and Tycholiz2019).

The rise of autocratic developmentalism and the gradual transformation of the state apparatus significantly altered the political context for negotiations with Chinese actors in the infrastructure sector. Following irregularities in the initial tender, the Chinese contractors who allegedly corrupted officials to win the first phase of Tanzania's new Standard Gauge Railway were banned. The project was subsequently retendered and awarded to a Turkish–Portuguese consortium (Zajontz Reference Zajontz2020a: 177–9). High-ranking Tanzanian officials and later the president himself publicly denounced the ‘exploitative and awkward’ (Magufuli, quoted in The Citizen 2019) conditions proposed by China Merchants for a special economic zone and mega-port in Bagamoyo. The BRI flagship project has since been shelved, although it is likely that negotiations will resume under President Samia Suluhu Hassan.

Institutionally, Magufuli's tenure was characterised by a centralisation of (economic) decision-making power in the presidential office, a tightening of control and oversight of the treasury, line ministries and state agencies and a rigid scrutiny of public spending, borrowing and procurements (Andreoni Reference Andreoni2017; Polus & Tycholiz Reference Polus and Tycholiz2019). Makundi and colleagues argue that

efforts under Magufuli to bring about transformations in the governance process, as part of his war on corruption, elitism and preferential tendering … may over time also confront the notion of “win-win” which is argued to have predominantly benefited associated Chinese contractors and suppliers in the past. On the other hand, it can be argued that Magufuli's style is diverting the country away from the risk of long-term dependency on China. (Makundi et al. Reference Makundi, Huyse and Develtere2017: 346)

The centralisation of power in the presidency, alongside numerous replacements of senior officials, crucially affected processes of strategic calculation and learning within relevant line ministries concerned with the TAZARA negotiations. Several interviewees argued that Magufuli's personal experiences were a reason for closer oversight and more cautious cost–benefit analyses in the context of infrastructure projects. Not only had Magufuli overseen the unsuccessful TRC privatisation, he also had a lot of experience in negotiating with Chinese contractors. Shivji (Reference Shivji2021: 5) points out that Magufuli was ‘known for his close supervision of infrastructure projects’ in his previous capacity as Minister of Works, Transport and Communication (2000–05 and 2010–15). As one interviewee put it: ‘You have a president who has been in the infrastructure sector throughout his political career over twenty years and who has dealt with Chinese companies. Maybe he knows how they deal with government’ (Kamata Int.). Magufuli subjected the TAZARA negotiations to his direct control by charging a long-standing confidant, late Chief Secretary John Kijazi, with leading the 2016 Tanzanian negotiation team.

Tanzanian officials with direct insights into the negotiations stressed that the Chinese proposal did not provide for a ‘win-win situation’ (Tanzanian top official Int.) and failed to serve the ‘national interest’ (Tanzanian senior official Int.). The Tanzanian government did not rule out a concession but the ‘issue was on the terms’: ‘If we would gain optimally from the arrangement but the problem is that we could not – when we assessed – the gain was not that much. So we thought: “why shouldn't we look for other options?” Yeah – better options than those which were given by the Chinese’ (Tanzanian senior official Int.). According to Tanzanian officials, Magufuli's presidency affected the government's strategic calculation when negotiating projects and investments:

The change is obvious that this time around [referring to the Magufuli administration] the government is moving slowly but cautiously. Cautiously. We need to make sure that whatever decision we take, we should not come to regret. We should do it perfectly and for the interest of the nation. … It should not be for this current generation, it should be for the future generation. Because when it comes to those arrangements you might give the railway – say TAZARA – concession it for 30 years. 30 years – it's a long time. So, before you come to such a decision, you should satisfy yourself. You should be pretty sure that the investment – or the arrangement – that you are going to enter into is of national interest, is of benefit to our side. It will move us from one point of development to the other. (Tanzanian senior official Int.)

Simultaneously, the Tanzanian government started to invest in TAZARA with its own resources. A top official reasoned that the government is committed to improving the overall state of the company for when ‘we take the big decisions’, emphasising that ‘we cannot be seen as neglecting the railway because without an injection of investments it will fade’ (Tanzanian top official Int.). In 2017, Tanzania allocated about $6.65 million for urgent maintenance measures over a period of two years. The bulk of the funds was allocated to procure 42 traction motors, with which seven locomotives can be rehabilitated. In July 2019, Magufuli, before using a TAZARA train to travel to Kisaki, personally inquired at the company's headquarters about the progress of the investment (Lusaka Times 2019), which exemplifies the high degree of control he exerted over public spending. A labour union executive argued that ‘the political will started to change towards TAZARA’ and that ‘the coming in of the new Head of State [Magufuli] has changed the way he thinks and the way the people in Tanzania are believed to think towards TAZARA’ (TAZARA labour union executive Int.).

The Tanzanian government, through the board of directors, has also urged the company to enter into access agreements with private operators to create alternative revenue streams (Tanzanian official Int.). In February 2018, TAZARA started a pilot project with the logistics company Calabash Freight, which led to a permanent contract in April 2019. Calabash meanwhile transports similar, some weeks even higher, cargo volumes than TAZARA itself. TAZARA also leases locomotives from Calabash to increase its pulling power (Tanzanian official Int.; Key informant A Int.; Tanzanian top official Int.). Since 2013, the shareholding governments have been in the process of revising the TAZARA Act of 1995. The revision is intended to further decentralise TAZARA's operation by strengthening the autonomous role of the cost and profit centres – the Zambian one in Mpika and the Tanzanian one in Dar es Salaam – and by restricting the duties of the company's headquarters to non-operative policy issues, to end the duplication of structures. The revised act will also clarify and extend legal provisions on possible modes of private-sector participation in TAZARA, such as open access agreements, operation contracts, concessions and investments into infrastructure (Tanzanian top official Int.; Tanzanian senior official Int.; Tanzanian official Int.).

Whilst the reform is necessary for a possible concession to a Chinese investor, Tanzanian officials stressed that investments in TAZARA would be considered regardless of their origin and that there was ‘appetite from the private sector’ (Tanzanian senior official Int.; also Tanzanian top official Int.). The explicit openness on the part of Tanzanian officials towards non-Chinese investment can be interpreted as an attempt to modify strategic selectivities that result from TAZARA's history, viz. the perceived dependence on a Chinese investor. In July 2019, Magufuli urged the relevant authorities to speed up the revision of the TAZARA act so that ‘legal provisions … allow any of the two countries to be able to conduct investment activities’ independently (quoted in Lusaka Times 2019). Magufuli had discovered the reform process as an opportunity to rehabilitate TAZARA on Tanzanian terms.

CONCLUSION

This article has illuminated the negotiations about the rehabilitation of an African railway steeped in history: TAZARA. It first discussed the lasting legacy of the anti-colonial history of the railway and problematised politico-economic developments leading to TAZARA'S steady decline. It was argued that China's long-standing involvement in the construction and maintenance of the railway, alongside the chronic underinvestment in the parastatal and its dysfunctional and politicised corporate structures, have created a strategically selective structural context that is biased towards the privatisation of the company to a Chinese investor.

The article subsequently revealed the different models for a Chinese participation that were preferred by the negotiating parties. The conditions of the Chinese proposal of a 30-years ROT PPP, notably the debt assumption by the shareholding governments, substantial tax exemptions and subsidies as well as layoffs of TAZARA workers, are emblematic for current Chinese accumulation strategies which have started to shift from loan-financed EPC contracts to long-term (equity) investments in Africa's infrastructure sector. Strategic calculation on the part of the shareholding governments was marked by reflexivity about and learning from previous failed railway privatisations. Negotiators also proved reflective regarding the commercial interests of the ‘Chinese of today’ (Tanzanian senior official Int.). Chinese strategies in the negotiations were perceived as markedly different from China's historical involvement in TAZARA. After the Chinese investors declined the shareholders’ proposal of a short-term management contract, the shareholding governments remained adamant in their rejection of the Chinese ROT proposal whose financial terms and expected social repercussions were deemed unacceptable.

Although a privatisation under the terms proposed by the Chinese consortium could be averted, the strategic leeway of the shareholding governments to rehabilitate TAZARA has differed as a result of distinct structural constraints and opportunities. Rehabilitating a highly indebted and chronically underfunded railway is crucially dependent on the availability of public financial resources. It was shown that the strategic capacity of the Zambian government has been increasingly constrained by paucity of funds, which has caused the Zambian government to advocate a long-term PPP with the Chinese investor. These findings underline that, whilst politicised allegations of a Chinese ‘debt trap’ have been rightly refuted, the growing indebtedness of some African countries to Chinese and other creditors can have detrimental effects on African agency (see Zajontz Reference Zajontz2021).

The article furthermore argued that African (state) agency in Sino–African relations is crucially co-determined by a ‘wider balance of forces within and beyond a given state’ (Jessop Reference Jessop2016: 56). It was shown that Tanzania's transformation towards an autocratic developmental state under late President Magufuli – itself a reaction to a changing balance of power in Tanzanian politics – has prompted the Tanzanian government to pursue a strategy in the TAZARA negotiations that was marked by cautious cost-benefit analyses. Simultaneously, the Magufuli administration invested into urgent maintenance measures and urged TAZARA to create alternative revenues from open access agreements, which can be understood as deliberate attempts at improving the strategically selective structural context of action in which TAZARA is rehabilitated.

The article has thus shown that African governments are differentially constrained in their strategic engagement with Chinese investors. I aimed at advancing the burgeoning, though largely atheoretical, debate about African agency in Africa–China relations. Attempts to assess the degree to which African actors, state or non-state, shape Africa–China relations must address the differential impact of structural contexts. This requires theoretical accounts that integrate structure and agency dialectically and, thus, transcend both crudely structuralist accounts of an all-powerful China and ontologically shallow conceptions of African agency that fail to explain how agents are differentially constrained or enabled by their structural contexts. The SRA offers a conceptually rich, heuristic framework for further analyses of how strategic actors interact with their strategically selective environment in concrete Sino–African conjunctures.