No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

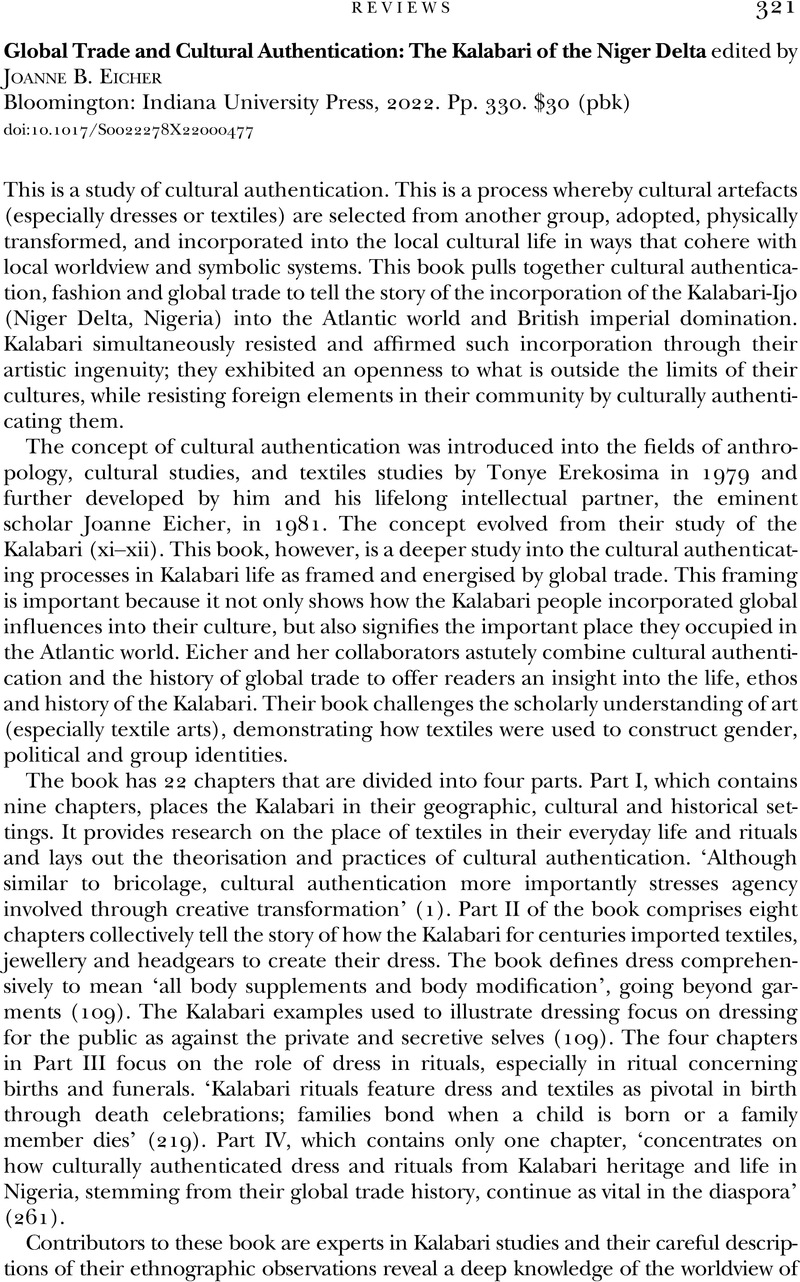

Global Trade and Cultural Authentication: The Kalabari of the Niger Delta edited by Joanne B. Eicher Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2022. Pp. 330. $30 (pbk)

Review products

Global Trade and Cultural Authentication: The Kalabari of the Niger Delta edited by Joanne B. Eicher Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2022. Pp. 330. $30 (pbk)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 July 2023

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Review

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press