INTRODUCTION

There's an event on women's participation in the peace process today. The event is organised by a local women's organisation, supported by international donors. It takes place at the Centre Aoua Keita in downtown Bamako, located just off Avenue de l'Indépendence and next to the roundabout with the big hippo statue. The conference centre is named after Malian politician and activist Aoua Keita, whose career and activism were central in the emergence of the early women's movement in Mali during the late colonial and post-colonial period. The centre is quite run-down, like many buildings in Bamako except a few international conference hotels and some hosting international organisations. I have found my way to the venue and been placed around a large conference table. Now we are waiting for the opening ceremony to start. In the front of the room there is a staged table with nameplates and a white tablecloth. Someone tells me that the minister was supposed to come but he sent someone in his place at the last minute. We wait, quite a few people are here now. I am impressed that so many people, including internationals, have shown up at this two-day event about women's participation in the peace process. The opening ceremony finally begins. When it's done, most of the people leave, including all the internationals. (Fieldnotes 19.10.2017)

This article analyses the interactions between different international and local actors involved in promoting UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSCR 1325) and subsequent resolutions referred to as the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda in Mali. Between February 2017 and June 2019, I spent time on and off in Bamako researching women's participation in the ongoing peace process. The analysis is based on participant observation, informal conversations, and 65 interviews with Malian civil society representatives, individuals working for the Malian government, and representatives from the international community working in Bamako. Some members of the international community interviewed in Bamako expressed frustration about their work trying to promote women's participation in the peace process, saying that the women in Mali were difficult to work with. On the other hand, Malian women's activists sometimes accused the international community of not doing enough to pressure the conflict parties to include more women. Despite working towards shared goals, interactions between local and international norm promoters were at times conflictual. This left me wondering how interactions between different actors affect the processes that take place when global norms travel to a new context.

After the outbreak of a Tuareg armed rebellion in the country's northern regions in 2012, an internationally supported peace process was launched in 2013 to support Mali's transition. As a result, Mali has moved from the periphery to the centre of international peace and security matters. In addition to French bilateral diplomatic and military engagement, the international community has been present in Mali through the UN peacekeeping operation MINUSMA since 2013 and is currently supporting the implementation of the 2015 Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in Mali (hereafter the Algiers Agreement). The Algiers Agreement was signed in Bamako in June 2015 by the Malian government and two coalitions of rebel groups (CMA and Plateforme), after 10 months of negotiations. It stipulates the creation of several mechanisms to support its implementation. While the transitional period was originally designed to cover 2015–2017, the implementation of the Algiers Agreement has been slow and incomplete (Boutellis & Zahar Reference Boutellis and Zahar2017; The Carter Center 2020).

While the adoption of UNSCR 1325 is considered a watershed moment for the recognition of women's roles in peace and security, critics have argued that the WPS agenda reproduces gender stereotypes of women as victims (of conflict-related sexual violence) or as agents of change (peacebuilders), and overlooks aspects such as race, class, sexuality and how they intersect with gender in the WPS framework (Pratt Reference Pratt2013; Shepherd Reference Shepherd2016; De Almagro Reference De Almagro2018). The WPS agenda covers a range of issues and is often referred to in terms of its four pillars: participation, conflict prevention, protection, and relief and recovery. In this article, I focus on women's participation in the peace process, which has been an important aspect of the work to promote WPS in Mali. From the beginning, the peace process was criticised for not including marginalised groups, such as women, youth and ethnic minorities (Boutellis & Zahar Reference Boutellis and Zahar2017). Promoting women's participation in the peace process was also the primary objective of the National Action Plan for the Implementation of UNSCR 1325, launched in 2015.

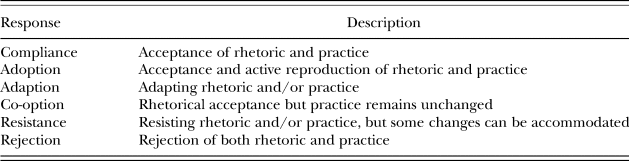

The literature on norms in International Relations (IR) has explored the ways in which norms travel between different contexts and the role of local intermediaries and translators in these processes (Acharya Reference Acharya2004; Berger Reference Berger2017; Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann2017). I build on and seek to contribute to this literature by deepening our understanding of the complexity of global–local interactions. I propose to study these interactions through the analytical lens of friction, defined as conflictual encounters in which local and global agents respond with strategies of compliance, adoption, adaption, co-option, resistance and rejection (Björkdahl et al. Reference Björkdahl, Höglund, Millar, van der Lijn and Verkoren2016: 6). In doing so, the article seeks to respond to the following research questions: what characterises frictional interactions between different (local and international) actors when norms travel? How do frictional interactions affect norm trajectories?

The article proceeds by introducing the theoretical framework on frictional interactions and travelling norms, followed by a presentation of the data and method. At the centre of my inquiry is the Malian women's movement, a diverse group of actors who play a key role as translators between global and local norms. A background on the Malian women's movement and women's rights reforms in Mali is therefore provided. In the analysis which follows, I analyse vertical (between local and international actors) and horizontal (between local actors) friction (Björkdahl & Höglund Reference Björkdahl and Höglund2013) in the Malian context, as well as the way different actors respond to friction and the outcomes that this produces.

FRICTIONAL INTERACTIONS AND TRAVELLING NORMS

A rich IR literature on norms has explored questions related to how norms travel between different socio-political contexts. Initially, scholars theorised that global human rights norms travel throughout the international system through cascades (Finnemore & Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998), diffusion spirals (Risse et al. Reference Risse, Ropp and Sikkink1999) and boomerang effects (Keck & Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998). A second wave of scholarship, however, criticised these theories for assuming that norm content remains stable and that norms diffuse from centre to periphery (Acharya Reference Acharya2004; Wiener Reference Wiener2004; Krook & True Reference Krook and True2010). In response, scholars developed theories on the localisation, translation and contestation of global norms, arguing that the meanings of norms change as they travel from one context to another (Acharya Reference Acharya2004; Wiener Reference Wiener2004; Zwingel Reference Zwingel2012). In line with current constructivist scholarship, this article adopts a conceptualisation of norms as dynamic processes characterised by their ongoing constitution which are both structuring and constructed (Wiener Reference Wiener2004: 201; Krook & True Reference Krook and True2010: 105).

The norms literature has conceptualised the different actors involved when norms travel to new contexts as external norm promoters and local translators, and highlighted the role of local translators who have knowledge of and master both the global and the local norms, and who translate global norms into localised practices that resonate with local norms (Acharya Reference Acharya2004; Berger Reference Berger2017; Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann2017). These local translators are usually NGOs, regional organisations, and local elites and/or activists, such as the diverse group of actors who constitute the Malian women's movement and who are at the heart of my analysis.

In order to analyse interactions between different actors involved when norms travel, I draw on insights from anthropology and peacebuilding researchers who have used the concept of ‘friction’ to analyse ‘the conflictual elements of global–local encounters’ (Björkdahl & Höglund Reference Björkdahl and Höglund2013: 291; see also Millar et al. Reference Millar, van der Lijn and Verkoren2013; Björkdahl et al. Reference Björkdahl, Höglund, Millar, van der Lijn and Verkoren2016). ‘Friction’ can be defined as interactions across difference with awkward, unequal, unstable and creative qualities, which define movement, cultural form and agency (Tsing Reference Tsing2005: 4–6). I suggest that analysing interaction through the lens of friction will contribute to a better understanding of the trajectories of norms. Friction further manifests in sites where local and international discourses and practices meet (Björkdahl & Höglund Reference Björkdahl and Höglund2013: 296), such as the Malian peace process. While the norms literature has had a tendency to focus on the global–local encounter, frictional encounters may be vertical, between local and international actors, and horizontal, between local actors (Björkdahl & Höglund Reference Björkdahl and Höglund2013; Kappler Reference Kappler2013).

The outcomes of friction may be positive and negative and can be both empowering and disempowering (Björkdahl & Höglund Reference Björkdahl and Höglund2013: 294; Björkdahl et al. Reference Björkdahl, Höglund, Millar, van der Lijn and Verkoren2016: 6), as well as ‘enabling, excluding, and particularizing’ (Tsing Reference Tsing2005: 6). According to Björkdahl et al. (Reference Björkdahl, Höglund, Millar, van der Lijn and Verkoren2016: 6), responses to friction consist of ‘compliance, adoption, adaption, co-option, resistance and rejection’. Such responses may be carried out by both local and international actors, and different combinations of responses may take place simultaneously. See Table I for definitions of the different responses used in this article. The analysis identifies several instances of vertical and horizontal friction, different actors’ responses to these, and the outcomes that this produces.

Table I. Responses to friction.

DATA AND METHOD

The research for this article relies on a diversity of data collection methods, including participant observation, informal conversations, formal interviews and collection of documents (Hammersley & Atkinson Reference Hammersley and Atkinson2007: 3). This article contributes to the ‘ethnographic turn’ in peace and conflict studies which considers ethnographic methods to be particularly well suited for exploring bottom-up processes and local experiences (Mac Ginty Reference Mac Ginty2008; Mac Ginty & Richmond Reference Mac Ginty and Richmond2016: 223; Millar Reference Millar2018). Between February 2017 and June 2019, I conducted fieldwork in Bamako over the course of five trips, lasting four and a half months in total. I conducted 65 interviews with 21 men and 54 women, consisting of 17 interviews with representatives from the international community working in Bamako (diplomats, UN staff, INGO staff), eight interviews with individuals working for the Malian government (Ministries and other government bodies, peace process mechanisms), and 40 interviews with Malian civil society representatives (women's organisations, other civil society organisations, researchers and activists).Footnote 1 I also attended numerous seminars, workshops and events organised by civil society, international donors and the Malian government on topics related to my research. I engaged in countless informal conversations spurred by the context in which these conversations took place, the nature of the work of conversation partners, or people showing an interest in my research. My fieldwork and data generation strategy were driven by an interest in learning about how different actors, local and international, worked with and interacted on WPS and women's participation in the peace process.

The analysis and writing up process focused on how different actors interacted over the WPS agenda and its meaning, and how they responded to friction. I coded the data using NVivo software according to three overarching themes: relationships, practices and understandings (of WPS). Within these three themes, I identified subthemes. The relationships theme included the subthemes of global/local relations, conflict/cooperation between actors and how interviewees talked about other actors. The practices theme included the subthemes resistance and promotion/activism. The understandings theme focused on what interviewees understood WPS to mean and subthemes including WPS as a Western concept, as women's presence, and as women's contributions as peace agents emerged inductively from the data. I then compared the themes across different groups of actors (international, government and civil society).

While the majority of the formal interviews were conducted between September and December 2017, it was useful to be able to carry out multiple research stays. During my later visits, I relied more on informal conversations and participant observation, and I could observe how the work on women's participation in the peace process and the WPS agenda developed over time. I found that the level of engagement with the WPS agenda among international actors, as well as the number of events or workshops on the topic, increased during the period I was conducting my fieldwork. To record my observations, I relied on fieldnotes, which together with interview transcripts form the primary data upon which the analysis is based.

At the centre of my analysis is the Malian women's movement, the segment of civil society that works on improving the situation for women in Mali in diverse ways, consisting of national and local women's organisations, individual activists and women leaders. I took a special interest in this group of actors due to their role as translators of global norms in the Malian context. While the landscape of Malian women's organisations is very diverse, my interviews and observations were geographically limited to the capital, Bamako, due to the security situation in the rest of the country at the time of my fieldwork. Further, because of my limited knowledge of local languages, the people I talked to mostly belonged to an educated, French-speaking elite. The following section provides a historical background of the women's movement and women's rights reforms in Mali.

THE MALIAN WOMEN'S MOVEMENT AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS REFORMS

The Malian women's movement

In the period following decolonisation until Mali's democratic transition in 1991, which ended 23 years of authoritarian rule by Moussa Traoré, women's national associations were subordinated to the party structure. The one-party system was set up so that the ruling party had a corresponding national women's organisation, which functioned as the only accepted outlet for women's public expression. The leader of the women's organisation had a place in the party leadership and represented the formal link between the women's organisation and the party. During this period, women's public participation mainly consisted of participation in political events (such as elections) and national holidays (Ba Konaré Reference Ba Konaré1993). De Jorio (Reference De Jorio and Stone2001: 325) found that Malian women argued for a greater level of women's public participation based on traditional values, which upheld the household as women's specific field of intervention, and without questioning traditional gender roles within the family. Women leaders in Mali thus articulated an extension of women's roles from the domestic to the public sphere, from the household to the national level, and women initially came to play a ‘maternal’ role in public. According to De Jorio, such gender-based discourses succeeded in creating opportunities for women's political intervention during colonialism and the decades following independence.

It is well known that Malian women played a central role in the developments and the demonstrations that preceded the 1991 events (Ba Konaré Reference Ba Konaré1993). The subsequent political opening brought a proliferation in the number of women's organisations in Mali, similar to many other African countries. An umbrella organisation, the Coordination des Association et ONG Feminine du Mali (CAFO), was founded in 1991 by four women's organisations in Bamako in order to serve as a link between the government and women's organisations across the country. In 1994, the number of member organisations was 50, and by 2002 it had reached 2,044 (Wing Reference Wing2008: 106–7). These changes in women's associational practices altered the way many women saw their public roles. The CAFO used its networks and influence to increase women's presence in politics by supporting women candidates across all of Mali. However, there were also divisions and conflicts within the women's movement, often linked to the gap between urban and rural women's realities (Wing Reference Wing2008: 107).

During the presidency of Alpha Oumar Konaré (1992–2002), and later also Amadou Toumani Touré (2002–2012), the government became increasingly involved in the coordination of women's organisations. In response to the explosive growth in the number of women's organisations, the Malian government claimed that a more cohesive and coordinated programme was needed. This co-opted the women's movement through increasing influence over the CAFO and the granting of access to funding and political appointments. These developments have favoured those groups of women who are closer to the majority party over others, and women's organisations rarely challenge the government (De Jorio Reference De Jorio and Stone2001: 325–6; Wing Reference Wing2008: 103).

Women's rights reforms

Following the political opening in the 1990s, the government of Alpha Oumar Konaré (1992–2002) pursued an ambitious neoliberal reform agenda (Soares Reference Soares2009). The first lady Adam Ba Konaré was an outspoken advocate of women's rights, and often spoke publicly about the need for reform. A prominent historian, in 1993 she published a biographical dictionary of famous Malian women in which she also identified some of the major challenges to gender equality in Mali (Ba Konaré Reference Ba Konaré1993). Gains during this period include changes to certain laws adversely affecting the rights of women, such as commercial and tax law, and institutional changes such as the establishment of the Ministry for the Promotion of Women, Children and Families (MPFEF) in 1997, and the establishment of a special division within the ministry tasked with the advancement of women's rights in 1999 (Soares Reference Soares2009: 410, 416).

National legislation on women's rights has, however, been a subject of controversy in Mali (Wing Reference Wing2008; Diallo Reference Diallo and Schlyter2009; Soares Reference Soares2009). During the late 1990s and throughout the 2000s, there were continuous struggles for women's rights over the attempts to reform the electoral code and the family code. The Malian Family Code of 1962 violates women's rights as recognised under international law by allowing child marriage for girls (at 15 years), by not always requiring consent for a marriage to be valid, and for discriminating against women in matters of inheritance. While the Malian state is secular, more than 90% of the population is Muslim and the tenets of Islam strongly influence the personal, social and increasingly also the political spheres. Over the past two decades, more conservative versions of Islam have gained a stronger position in Malian society and religious leaders have been exerting increasing influence over social and political life. Some of these religious actors openly oppose efforts to promote gender equality and women's rights and have managed to block legal reforms on several occasions, such as the attempts to reform the Family Code in 2002 and in 2009. The suggested reforms to the family code proposed to the National Assembly in 2002 consisted of raising the age for girls to marry from 15 to 18 years (the same as for men) and making husband and wife equal in marriage and men and women equal in inheritance. Faced with considerable criticism from Malian Muslims, the proposal was withdrawn weeks later. During another attempt at reform in 2009, the Islamic High Council (HCI) mobilised massive street protests against the proposed legal reform that again resulted in withdrawal of the proposal (Diallo Reference Diallo and Schlyter2009; Soares Reference Soares2009).

While there are examples of women holding government ministerial posts and seats in the National Assembly, historically the numbers are low. Efforts to address the low representation of women in administrative and political bodies failed in 2006, when the Malian National Assembly almost unanimously rejected a proposal for the introduction of a quota system into the electoral code (Diallo Reference Diallo and Schlyter2009: 121). In December 2015, however, the Malian government adopted a decree calling for a 30% quota for female appointments to national institutions and legislative bodies. The women's movement had campaigned for a reform in the electoral code since the 2000s, and activists I spoke with in Bamako considered this action to be a victory and the result of many years’ struggle. The gender quota was implemented during the 2016 local elections (Johnson Reference Johnson2019), and following parliamentary elections in April 2020 the percentage of women deputies in the National Assembly increased from 9.5% to 27.9% (Interparliamentary Union 2020).

TRAVELLING NORMS: WOMEN, PEACE AND SECURITY IN MALI

Today, UNSCR 1325 is well known among activists, women's organisations and responsible government institutions in Mali, but it remains little known outside these circles. Many women's activists had learned about UNSCR 1325 through their involvement in various activities and processes, such as a woman leader I talked to who participated in the peace negotiations in Algiers: ‘resolution 1325 speaks above all about the representation of women in negotiations. Above all, Resolution 1325 gives women a role to play in the process, in the process of building peace, from the negotiating table, to implementation, in the monitoring’ (Woman Leader 22.9.2017, Int.). Women's organisations have used the resolution as a tool for advocacy and have worked on spreading knowledge about UNSCR 1325 and its contents through the organisation of training and workshops across the country.

Mali launched its first National Action Plan (NAP) for the implementation of UNSCR 1325 on Women, Peace and Security in 2012. This work, however, was little known and implemented, due in part to its launch coinciding with the 2012 crisis. The second NAP was launched in 2015 for the period 2015–2017, and its overarching goal was to promote women's participation in the implementation of the Algiers Agreement. The second NAP suffered from a lack of funding to support its implementation, and when UN Women assessed this work in 2018, they found that only 50% of the planned activities had been carried out. It was further beset by challenges concerning how to decentralise its commitments from the national to the local levels. A third NAP for the period 2019–2023 was developed by the Ministry for the Promotion of Women, Children and Families (MPFEF), supported by UN Women in the period 2017–2019 and launched in 2019.

The work of implementing the WPS agenda in Mali is the responsibility of MPFEF in collaboration with Malian civil society organisations, with support from international partners. Within the ministry, there is a permanent secretariat that monitors the implementation of Mali's gender policies. Further, there is the Higher Council for National Gender Policy, which is chaired by the Prime Minister (MPFEF 6.12.2017, Int.). A technical team, including a specialist on Women, Peace and Security, was established in 2017 to coordinate and follow up the development and implementation of the third 1325 NAP. Focal points have been appointed by the government ministries whose work will be affected by the NAP and who will be responsible for its implementation, and these receive capacity-building and follow-up from international partners (UN Women 27.11.2018, Int.).

Adapting to vertical friction: creating spaces for empowerment

Across the interviews and informal conversations I conducted in Mali, many examples of vertical friction between international and local actors emerged. In this section, I analyse how international actors responded to friction over WPS as a ‘Western concept’ by adapting their rhetoric and practice. Donors play a big role in supporting the activities of local NGOs and associations in Mali. Almost everyone I spoke with thinks that international partners are important and that they have an impact on the situation of civil society organisations in Mali and the conditions for their work, and can give examples of collaboration or support, including funding. MINUSMA, UN Women and some individual governments were mentioned as important partners and supporters in promoting women's participation. A woman working for a local peacebuilding NGO (5.10.2017, Int.) explained:

Because we actually have the same vision, so maybe there can be some moments of … I don't know how to say … small differences. Which are related to social constraints that we must adapt to in this society. Otherwise it's good, there is no problem. Because well, the international partners, they have a certain ambition, we have almost the same vision, but perhaps it is the approach that can differ a little.

While the majority of interviewees found the collaboration with international partners to be good, the above statement shows that, in some cases, local realities might not correspond to the demands of donors. Historically, campaigns for women's rights reforms in Mali have often been met with suspicion and accusations of advocating the imposition of Western values on Malian Muslims (Soares Reference Soares2005: 89), and many women who were active in the women's movement in the 1990s and 2000s found it necessary to distance themselves from the international human rights movement or risk being labelled as ‘Westernised’ and out of touch with Malian realities (Wing Reference Wing2008: 118). A statement by a government employee (7.12.2017, Int.) suggests that many consider WPS a foreign idea that has been imported to Mali: ‘It was after [the Algiers negotiations] that the problem of women was introduced. And who introduced the problem of women? It was the foreigners.’ During the Algiers negotiations however, Malian women's activists engaged in advocacy campaigns to promote women's inclusion in the negotiations with support from several (but far from all) international partners (Lorentzen Reference Lorentzen2020: 496).

Adapting to this situation, international actors are aware of the need to frame women's participation in the peace process as a local and not a Western agenda. When MINUSMA staff spoke about working with women in Mali, they said that they wanted the women to ‘tell your message, not our message’ (MINUSMA 11.12.2017, Int.), and emphasised that they were facilitators: ‘We facilitated, because we did a workshop where we invited all the organisations, civil society organisations, they came from the north, from practically all the regions, and then the ones here in Bamako as well’ (MINUSMA 28.2.2017, Int.). The use of words such as ‘facilitate’ or emphasising the need to convey ‘their’ message indicates that these international actors understand that Malian women risk being accused of promoting a Western agenda and are responding to vertical friction by adapting their rhetoric and strategies.

As this discussion shows, international actors may also function as norm translators when they respond to vertical friction by adapting to the local context in order to promote local ownership and legitimacy. In this case, international actors seek to empower local actors in order to promote normative change. One way this plays out is through the creation of spaces where such empowerment can take place. In the previous quotation, the interviewee is talking about the role of MINUSMA in establishing the Women Leaders Platform (Plateforme des Femmes Leaders).Footnote 2 Formed in Bamako in 2014, the Women Leaders Platform is a network of women's organisations who collaborate to influence the peace process. It was envisioned to help women organise in relation to the peace process, and to put forth women's demands with a unified voice. Individual members also received training through the Women Leaders Platform, and MINUSMA supported several workshops for women to discuss and find agreement on their priorities in relation to the peace process. Since the beginning of the peace process, international efforts to support women's participation have often focused on supporting women to become more united and have largely taken place via the Women Leaders Platform.

Adapting to and resisting vertical friction: women as agents for peace or conflict actors

Different instances of vertical friction were also responded to in diverse ways. In this section I discuss how local actors adapt and resist the way the WPS agenda and international actors assign women roles as ‘peace agents’. At the time of my fieldwork, there was one incident especially that caused some international actors to say that women in Mali were difficult to work with. In November 2017, MPFEF organised a four-day event in Bamako gathering women from all over Mali to discuss the peace process. I learned about the details of the meeting during a conversation with a woman who represents one of the rebel groups, and I went to the Modibo Keita Memorial where the opening ceremony would be held: ‘Outside, there is a big poster proclaiming that this is a meeting for peace, taking place under the patronage of the first lady and the minister for women's advancement. When I enter the large space, it is already filled with people. Before the minister speaks, her griot takes the podium to sing her praises. Afterwards, a summary of the speech is repeated in all the national languages of Mali. This is followed by a performance by a large group of women dressed in white who dance and sing “on veut la paix” (we want peace). Some people in the audience join in with the singing and dancing as well. Everything is very ceremonial and grand, and the spirit is high and positive’ (Fieldnotes, 25.11.2017). A couple of days later, an acquaintance in the diplomatic community asked me if I had heard about what had happened with ‘the women’. I also learned about the incident from an MPFEF employee (6.12.2017, Int.):

Unintentionally or for whatever reason, there is a woman who once wore a scarf hanging from … which looked like the flag of Azawad. It was not even the flag of Azawad. So, these are interpretations that have certainly created a lot of rumours, a lot of tension.

In the days following this meeting for peace, one of the participants had attended the National Assembly wearing a scarf that resembled the Azawad flag, which is the name of the northern territory for which independence was sought during the rebellion. During the Algiers negotiations, the parties agreed that they would give up the aspiration for Azawad, and the peace agreement rests upon a united Malian territory. The incident therefore caused a lot of tension and was the talk of the town for a few days. The minister for women's advancement had to give a public statement; because she had hosted the meeting, it was viewed as her responsibility. People said she almost had to resign. In response to the incident, which was widely interpreted as a political act, complaints about women being spoilers and difficult to work with were voiced. This incident illustrates women's political agency in the Malian conflict and peace process, and their roles as conflict actors.

Historically, Tuareg women in Mali have played active roles both in mobilising for rebellion and in appeasing tensions, for example as informal mediators (Bencherif & Ag Rousmane Reference Bencherif and Ag Rousmane2017: 3). International actors, however, usually expected women to represent the shared interests of women in the peace process rather than the interests of a group, ethnic or otherwise. A MINUSMA officer (11.12.2017, Int.) explained that working through the armed movements to promote women's participation had provided limited results, and that since women as a category were being ignored, ‘it is good if [women] can work together’. International actors thus expected women to play a role as agents for peace who could cut across existing divisions. This reflects the global WPS discourse where women tend to be represented as peace agents, while their roles as conflict actors are subverted. Women's agency is thus linked to their roles as peacebuilders and vertical friction arises when women are expected to behave in a specific way (as peace agents).

Similarly, many women's activists emphasised the importance of representing women's shared interests in the peace process: ‘When there were the first rounds of negotiations in Algiers, the women did not participate as women, so we did a lot of advocacy and in the second round we participated as women’ (Woman leader 17.10.2017, Int.). Further, a woman leader (29.9.2017, Int.) told me that ‘the woman is a natural peace champion’. This shows how interviewees would often highlight Malian women's traditional roles in society to support arguments about women as peace agents. Local norm translators such as women leaders and activists thus respond to vertical friction by adaptation: They draw on (local) understandings of women's roles to help the (global) understanding of women as peace agents gain traction in the local context.

This example shows how vertical friction between women as (global) peace agents or (local) conflict actors is characterised by a pull towards increased homogenisation of women as a group and their roles as peace agents. While government representatives and women leaders adapt the global discourse of women as peace agents to fit local norms and practices, women outside the women's movement did not conform to these expectations. This can be seen as a form of resistance to the homogenising pull of vertical friction.

Further, the way different actors respond to vertical friction triggers feedback loops, which in turn trigger new responses and outcomes. For example, international actors responded to vertical friction and women's behaviour as conflict actors with resistance by trying to depoliticise and homogenise women and their agency, and by dismissing women as being difficult to work with. This reduces the ways in which women can express their agency, with potentially disempowering outcomes. Moreover, if women are only afforded participation based on their roles as peace agents, this means that when some women act as conflict actors, this allows for arguments to be voiced against the participation of all women in the peace process. Therefore, when empowerment and inclusion are sought through homogenisation, vertical friction may also have unpredictable outcomes, such as disempowerment and exclusion.

Responding to vertical friction with co-option: the ‘workshop industry’

This section analyses an instance where the Malian women's movement responded to vertical friction by rhetorical acceptance of global norms while their practices largely remained unchanged. In response to events in the peace process, meetings would take place – often organised by or with the support of MINUSMA or UN Women – to bring the women together to agree on recommendations. This was done for example in preparation for the peace negotiations in Algiers in 2014/15, and in preparation for the Conference for National Reconciliation in March 2017. In many such cases, the expected outcome would be a written document that women could gather around, which could be presented to stakeholders in the peace process. Often, these demands would centre on women ‘getting a place’ in the peace process.

At the beginning of my second stay in Bamako, one interviewee who worked for an international NGO (18.9.2017, Int.) explained that there is a ‘workshop industry’ at the level of the capital. During the course of my stay, I would come to learn first-hand what she meant. In October 2017, I was present at one such workshop in Bamako, which lasted for two days. In my notes from the first day, I wrote: ‘I am sitting at my place at the table listening, taking notes. I find this difficult. I am struggling to follow everything that is being said, the microphone isn't working properly, and everything seems a bit disorganised. I am wondering if anyone is taking note of what is being said. … It's 4:15 and the last session was supposed to end at four. Many have left already. Everyone is tired’ (Fieldnotes, 19.10.2017). It was my understanding that the purpose of this workshop was to formulate women's recommendations for the peace process. However, it was unclear who would receive these recommendations. At first, I thought they would be presented to the UN Security Council who were visiting Mali later that same week. But when we were unable to finish formulating the recommendations over the two-day workshop, the organiser proposed to meet again in two weeks’ time. I asked them who was going to receive the recommendations, but I didn't get a clear answer. I also emailed the organiser two weeks later asking whether they had finalised the list of recommendations. They hadn't.

Many interviewees talked about the extensive organisation of workshops that extends throughout Malian civil society, including the women's movement. The different workshops tend to be attended by the same people, who often receive a per diem for their participation. Several interviewees, especially young people, also complained about the lack of inclusivity and diversity among workshop participants. The practices of the ‘workshop industry’ also caused vertical friction between local and international actors. A representative of an international NGO (3.10.2017, Int.) who had worked in Mali for several years promoting women's participation in the peace process told me about her experience:

We said: What do you want to do? What for? Is it to demand that there should be 15 women around the table? If so, what is it for? You want to go to these meetings; what do you want to say? And if you want my opinion, I think they never got past this stage. And it was a little disappointing because, for once, they really had people who were ready to help them work on this reflection. And in fact – you will soon realise this – we are in this tradition of activism where when you march, when you protest … then you do something. But we don't get to the second, third, fourth move after that action, you see?

The interviewee was clearly frustrated with what seemed like an endless number of meetings without concrete output. The quotation illustrates that while Malian women activists adopt a global rhetoric about women's participation, their practices do not significantly change. When I asked women leaders about their goals for the peace process, the responses revolved around women's participation (a place for women in the process), or more general demands including peace, and a united Malian territory. According to a Malian government employee (7.12.2017, Int.) working on the peace process, ‘women’ were mainly concerned with getting a place in the process: ‘They just want a place, they just want to participate, without saying concretely this is what they can contribute.’ Historically, however, activism in the Malian women's movement has been as supporters, facilitators and mobilisers of political events (De Jorio Reference De Jorio and Stone2001: 324). For Malian women's activists, operating within the confines of traditional gender roles and the expectations that came with this, activism often meant ‘doing something’, such as to organise a workshop or a protest, and participation meant ‘being present’.

Women leaders and activists in Mali thus responded to vertical friction with co-option. While they adopt the global rhetoric of the WPS agenda and participate in or organise events in response to expectations from international actors, they also continue to operate within the ‘workshop industry’; in this case, the WPS rhetoric is accepted, but certain practices remain unchanged. The frictional interaction between international and local actors produces only superficial change, with the result that projects and programmes achieve limited impact, and ‘empty’ practices of workshops are repeated without tangible outcomes. Local norms and practices appear to be resilient rather than to be changing as a result of vertical friction. While these practices may be meaningful locally, they appear meaningless to international actors. Despite intentions to empower local actors and perspectives, it can be argued that the outcome of this vertical friction is rather that local actors are disempowered.

Adapting to horizontal friction: defining insiders/outsiders

The previous discussion demonstrated how vertical friction involves a pull towards increased homogenisation of women as a group. However, as the following discussion will show, women's identities are complex and horizontal frictions arise when expectations for women to represent a shared identity as women clash with other axes along which their identities intersect, such as ethnicity, political ideology, age, class and location. In response, local actors adapt to horizontal friction by seeking to define who has access to spaces for empowerment such as the Women Leaders Platform.

Some activists complained that the women who were chosen to participate in the peace process often did not represent the shared interests of women: ‘They bring women. But is it women who defend the interests of women? No.… They're there because the president put them there’ (Woman leader 7.11.2017, Int.). The way women leaders and activists argue that women should be represented in the peace process ‘as women’ echoes the global WPS discourse, which also emphasises women's shared identities. This can cause horizontal friction between local norm translators (i.e. activists and women leaders) and other local actors, since women often also have other group affiliations.

Many Tuareg women in northern Mali, especially in Kidal, remain sceptical of the peace process. Some fear that the return of state authority will involve renewed humiliations and atrocities such as those committed by the Malian state and its security forces during previous rebellions. Women leaders from southern Mali on the other hand often highlight that the Tuareg rebellion is not the only element of the 2012 crisis, which also threw Mali into a constitutional crisis following a coup d’état on 21 March 2012 (Bencherif & Ag Rousmane Reference Bencherif and Ag Rousmane2017: 3). Areas in the south have been less affected by conflict, and do not share the experiences of state sanctioned abuse. However, in the years following the signing of the Algiers agreement the conflict has spread to the central regions of Mali. Here, many Fulani communities have experienced targeted attacks and killings by security forces of mainly Bambara ethnicity (Sandor Reference Sandor2017: 13), thus eroding trust in the central state and its security apparatus. Further, the Malian conflict, and not least the Tuareg rebel movement, has been characterised by fragmentation and unstable alliances (Chebli Reference Chebli2019), highlighting how there are considerable differences and fractures between Tuareg and other communities, and among Tuareg.

These horizontal frictions became apparent to me when I attended meetings or events organised by members of the Women Leaders Platform in Bamako. At these meetings, representatives of the women from the rebel groups were often also present: ‘One of the women leaders in the room asks for the word and starts speaking. At first, she talks about how women have been the victims of so many harms and that they are not included, and that the peace agreement has given them nothing. Then she says: ‘The CMA and Plateforme are in Bamako in their airconditioned hotel rooms dragging their feet, delaying the agreement. They don't want peace.’ This caused a very heated rebuttal from a woman representing one of the rebel groups. She said: ‘This is not true, everybody wants peace, otherwise they wouldn't have signed the agreement.’ She verbally attacks the other in a language I don't understand. The other participants try to calm the tensions and after a while the discussions resume’ (Fieldnotes, 19.10.2017).

I was confused at first regarding the role of the women representing the rebel groups, and their position in the Women Leaders Platform. Conversations and interviews helped me understand how other actors saw these women and their position:

These women tell themselves that they are for peace, they do activities within the framework of the peace process you see. But a woman here, in a group, generally she adopts the philosophy of the group. If this is a group that is for peace, the woman will work in this direction. If it is a group which is not for peace she is obliged to conform, otherwise she will be replaced by someone else. (Local UN staff 26.9.2017, Int.)

I learned that many found the roles of the women representing the rebel groups ambiguous, and their group affiliations were perceived to be more important than their shared identities as women. Defining who has the right to represent the interests of women thus becomes very important, because it potentially grants access to the peace process, in this case through the Women Leaders Platform. Adapting to this situation, the women representing the rebel groups had started to see and present themselves as peace agents representing the shared interests of women, thus seeking access to the peace process on this basis.

From conversations with different actors in Bamako, I also learned that women leaders representing civil society found it important to be perceived as separate from the women representing the rebel groups. This group adapted to horizontal friction by trying to draw a line between themselves and the women representing the rebel groups. The peace process and vertical friction thus bring together women representatives who perhaps would not have joined forces otherwise, leading to horizontal friction and discussions about what their roles are and who they represent.

This does not mean that the women representing the rebel groups were excluded. They legitimately represented the interests of their group (and of women within that group), and regularly attended the meetings with other women leaders. The challenge was whether the Women Leaders Platform was able to credibly unite these different women leaders. While many women's activists consider the peace process an opportunity to promote women's rights as part of an ongoing struggle for legal and institutional changes, for women who are affiliated with the rebel groups, the peace process is more often a way of seeking redress for group rights. Women leaders respond to horizontal friction by adapting their rhetoric and practices, creating a situation where people start defining insiders and outsiders. Rather than homogenising and uniting the group, more diversity is brought in with the outcome that the group appears fragmented.

Responding to horizontal friction with resistance and co-option: female leadership and power relations within the women's movement

In this section, I analyse how actors responded to horizontal friction over access to power and resources within the women's movement with resistance and co-option. While the Women Leaders Platform was meant to unite women, it mainly succeeded in providing a forum for bringing together women who hold established positions within the women's movement at the level of the capital. A male representative of a local peacebuilding organisation (26.9.2017, Int.) observed:

It is necessary to take into account the Malian reality which is that most women are rural. And that there are some intellectual women in the big cities, in particular Bamako, who do this work of feminist activism, which is not always well connected with the reality of the rural areas. And when it is not connected, that means that it is not legitimate, if I can put it like that. Meaning that they are not the true spokesperson for the aspiration of women out there.

Are the women who gain access to the peace process representative of women's interests in general, or mainly the interests of elite, urban women? Many interviewees raised this issue, which points to longstanding tensions and divisions in Malian society related to the gap between urban and rural populations, and between elites and non-elites (Wing Reference Wing2008: 123). Historically, patron–client relations have served as an important structuring force within women's organisations in Mali. Women's organisations coalesced around elite women who were able to form patron–client relations with other women, creating a situation where they were able to secure access to economic opportunities (employment, development projects etc.) for their members (De Jorio Reference De Jorio and Stone2001: 331–3). Membership in organisations thus became centred on the individual rather than on ideology, and this personalised approach goes a long way to explaining the conflicts that characterise some of these organisations, and why it has been challenging to unite the diverse landscape that makes up the Malian women's organisations under a shared identity as ‘women’.

The government's increasing control over organisations such as the CAFO has made leadership positions in the women's movement a potential route to positions of power elsewhere. For example, Oumou Touré Traoré, who was the Minister for the Advancement of Women in 2017–2018, came directly from the position as secretary general of the CAFO. Interviewees also claimed that the power struggles within organisations and between individuals sometimes diverted attention away from what were supposedly the objectives of their work, such as inclusion or peacebuilding (International NGO 3.10.2017, Int.). And while women leaders emphasised the need for women to speak with a unified voice, they also described horizontal friction in the form of power struggles within the women's movement:

After the agreement, the signature … as a reaction, many women like me, I am no longer very active in the platform, because we created the platform to defend a common cause, evolve, move forward. Not everyone can be in positions, but those who are represented must come from the masses, must be a choice of all women. (Woman leader 29.11.2017, Int.)

Some women, such as the woman leader quoted above, responded to horizontal friction within the women's movement with resistance and decided to detach themselves from the activities of the Women Leaders Platform. For other women, the activities of the Women Leaders Platform and other activities related to the peace process have offered new career opportunities or consolidated their positions within the women's movement. These actors have responded to horizontal friction with co-option: by accepting a rhetoric of uniting and representing the shared interests of women while continuing practices of female leadership that are built on patron–client relations, they have used the new opportunities created by the peace process to secure positions for themselves.

In contrast to the horizontal friction between representatives from civil society and those from the rebel groups, which seemed to emerge in response to the homogenising pull of vertical friction, the horizontal frictions within the women's movement described here are rather linked to longstanding class tensions within the women's movement and more generally in Malian society. In this case, horizontal frictions are exacerbated by the way the work to promote women's participation in the peace process has built on existing practices of female leadership. The outcome of the latter horizontal frictions is reinforcement of existing power dynamics, further empowering some actors while disempowering others.

CONCLUSION

This article has analysed the frictional interactions that occur when global norms travel to a new context, based on a study of how different actors – local and international – worked with and interacted on WPS and women's participation in the Malian peace process. This has been achieved through discussing vertical (global–local) and horizontal (local–local) frictions between actors in the Malian context, the ways in which different actors respond to friction, and the outcomes that these responses to friction produce. By focusing on the social dynamics that unfold between different actors, the article deepens our understanding of the processes that take place when norms travel between different contexts.

The article argues that complex frictional interactions affect norm trajectories. It finds that the ways different actors respond to friction shape trajectories and relations and trigger feedback loops, which in turn trigger new responses and outcomes. Among the findings are that international actors respond to vertical friction by adaptation, creating spaces for empowerment such as the Women Leaders Platform. At the centre of the inquiry is the Malian women's movement, a diverse group of actors who play a key role as norm translators in the encounter between global and local norms. However, while existing literature has focused on the role of local intermediaries (such as women's rights activists), the analysis shows that international actors who operate in the local context also play an important role as ‘local’ translators.

Vertical frictions are further characterised by a pull towards increased homogenisation of women as a group and their roles as peace agents. Although empowerment and inclusion were the intended outcomes, vertical friction sometimes also resulted in disempowerment and exclusion when women did not comply with global WPS norms and the expectations of international actors. Moreover, global norms were not always able to replace local norms and practices, and sometimes vertical friction was characterised by co-option through the resilience of local practice. Rather than producing new spaces for empowerment, this resulted in superficial change and ‘empty practices’. Horizontal frictions also surfaced in response to the homogenising pull of vertical friction, when women representing civil society and women representing the rebel groups adapted their strategies to define insiders and outsiders in the Women Leaders Platform, which resulted in women ‘as a group’ appearing more fragmented. Horizontal frictions within the women's movement were met with resistance and co-option. This reinforced existing power dynamics – empowering and including some women, while disempowering and excluding others.

A contribution of this paper is the generation of new insights into how vertical and horizontal friction are linked in the local context, though not necessarily causally. When horizontal friction was observed between women representing civil society and those representing the rebel groups, this happened in response to vertical friction. On the other hand, existing lines of division within the women's movement were exacerbated – but by no means created – by vertical friction. While vertical friction sometimes produces spaces for empowerment such as the Women Leaders Platform, responses to horizontal friction seek to define who belongs in those spaces and impacts whether those spaces will be empowering or disempowering (and for whom).

Finally, this article joins important ongoing debates in the vast literature on the WPS agenda regarding where this agenda is located and produced. On the occasion of the agenda's 20th anniversary, a recent special issue of the International Feminist Journal of Politics highlighted how theory building must happen ‘on the ground’ and that ‘to understand WPS, researchers and practitioners must examine its local contexts’ (Shepherd Reference Shepherd2020: 458). The article contributes to these discussions by showing how the agenda is translated, and thereby infused with meaning, by a range of different actors in the Malian context, and how this affects the meaning and practice of norms and ideas about women's participation that are at the heart of the agenda.