I. INTRODUCTION

The processing of metals through the application of severe plastic deformation (SPD) has attracted much attention for the production of ultrafine-grained metals having grain sizes in the submicrometer or even the nanometer range. Reference Valiev, Islamgaliev and Alexandrov1 Among the various SPD techniques, high-pressure torsion (HPT) provides the potential for achieving true nanometer grains in bulk metals. Reference Zhilyaev and Langdon2 In HPT, a disk is strained under a high compressive pressure with concurrent torsional straining and the processing is usually conducted at room temperature which is effective even for difficult-to-deform materials such as Mg alloys. Reference Abdulov, Valiev and Krasilnikov3 Numerous reports are now available describing the application of HPT to a range of pure metals and simple alloys and they demonstrate an enhancement of the physical and mechanical characteristics through significant grain refinement and the intensive introduction of defects. Reference Zhilyaev and Langdon2,Reference Langdon4

A critical limitation in HPT processing is that the imposed strain within the disk sample is significantly inhomogeneous. Specifically, when a disk is strained by conventional HPT, the shear strain, γ, is given by a relationship of the form Reference Valiev, Ivanisenko, Rauch and Baudelet5

where N is the number of HPT revolutions and r and h are the radius and thickness of the disk, respectively. Therefore, it is apparent from Eq. (1) that the torsional straining imposed within the disk sample is dependent upon the distance from the center of the disk and there is even zero straining at r = 0 during processing. This suggests that there is an inevitable inhomogeneity both in the microstructure and in the hardness in HPT disk samples after processing. Nevertheless, early experiments demonstrated that high numbers of HPT revolutions and/or high applied pressures are effective in producing reasonably homogeneous microstructures and homogeneous values for the microhardness throughout the disks. Reference Jiang, Zhu, Butt, Alexandrov and Lowe6–Reference Zhilyaev, Nurislamova, Kim, Baró, Szpunar and Langdon8

The light-weight metals of Al and Mg are widely used in structural applications in the automotive, aerospace, and electronic industries but improvements in the mechanical properties of these metals would accelerate their usage in future applications. Combinations of different SPD processing techniques are available to enhance the upper limit of mechanical properties of a specific alloy Reference Duan, Liao, Kawasaki, Figueiredo and Langdon9–Reference Sabbaghianrad and Langdon13 but it is also important to study achieving superior properties by bonding dissimilar metals through a procedure such as fusion welding. Alternatively, processing by HPT was applied recently for the consolidation of metal powders and for fabricating dissimilar metallic systems based on aluminum and magnesium: for example, Al–Fe, Reference Cubero-Sesin and Horita14 Al–Mg, Reference Kaneko, Hata, Tokunaga and Horita15 Al–Ni, Reference Edalati, Toh, Watanabe and Horita16 Al–Ti, Reference Edalati, Toh, Iwaoka, Watanabe, Horita, Kashioka, Kishida and Inui17 Al–W, Reference Rajulapati, Scattergood, Murty, Horita, Langdon and Koch18,Reference Edalati, Toh, Iwaoka and Horita19 and Mg–Zn–Y. Reference Jenei, Gubicza, Yoon and Kim20 Nevertheless, the practical difficulties associated with these processes include a requirement for a high processing temperature, Reference Edalati, Toh, Watanabe and Horita16,Reference Edalati, Toh, Iwaoka, Watanabe, Horita, Kashioka, Kishida and Inui17,Reference Edalati, Toh, Iwaoka and Horita19,Reference Jenei, Gubicza, Yoon and Kim20 the need for a two-step process of cold/hot compaction prior to consolidation by HPT Reference Rajulapati, Scattergood, Murty, Horita, Langdon and Koch18 and the inherent damage that may be introduced in the HPT anvils because of the stacking of fine hard powders in the depressions on the anvil surfaces.

Considering the processes for bonding of dissimilar metals, cladding-type metal working is generally utilized by pressing or rolling dissimilar bulk metals together under a high pressure as in the roll-bonding process. Reference Peng, Wuhrer, Heness and Yeung21–Reference Lee, Lee and Kwon25 This approach was also developed using the accumulative roll bonding (ARB) process Reference Saito, Tsuji, Utsunomiya, Sakai and Hong26 but the essential drawback of the processed metal plate after ARB involves the anisotropic mechanical response which is dependent upon the rolling direction and the through-thickness direction. Reference Beausir, Scharnweber, Jaschinski, Brokmeier, Oertel and Skrotzki27

A very recent report demonstrated a solid-state reaction in an Al–Cu system through the bonding of semicircular half-disks of Al and Cu through HPT at ambient temperature for up to 100 turns Reference Oh-ishi, Edalati, Kim, Hono and Horita28 and the vision of architecturing hybrid metals through HPT was discussed using computational calculations. Reference Bouaziz, Kim and Estrin29 Accordingly, the present research was initiated to examine the alternative possibility of achieving direct diffusion bonding of Al and Mg disks through conventional HPT processing for a short period of time. A very recent study showed the first demonstration of diffusion bonding of separate Al and Mg disks by HPT for 10 turns and the processed disk recorded very high specific strength attained by a combination of grain refinement, solution strengthening, and precipitation hardening. Reference Ahn, Zhilyaev, Lee, Kawasaki and Langdon30 However, the microstructural change through HPT generally occurs in the early stage of processing and the essential issue of the diffusion bonding of these dissimilar metal disks was not well understood in the earlier study. Therefore, the present research was aimed specifically to examine the feasibility of the formation of a multi-layered Al–Mg system through the bonding of Al and Mg disks through HPT for 5 turns and the resultant microstructure was evaluated by estimating the diffusivity of Mg atoms in an Al phase under the specific processing conditions of 5 turns. As will be demonstrated, the results provide a direct confirmation of the potential for making use of HPT for the formation of an intermetallic-based metal matrix nanocomposite in the nanostructured multi-layered Al–Mg disk through diffusion bonding for 5 HPT turns at room temperature.

II. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Two separate metals of aluminum and magnesium were used in the present experiments. Specifically, they were a commercial purity (99.5%) aluminum Al-1050 alloy containing 0.40 wt% Fe and 0.25 wt% Si as a major impurity with <0.07 wt% Zn and <0.05 wt% of Cu and Mg as a minor impurity and a commercial ZK60 magnesium alloy containing 4.79 wt% Zn and 0.75 wt% Zr. Both of these alloys were received as bars after extrusion with diameters of ∼10 mm. Each bar was cut and sliced into disks having thicknesses of ∼1.2 mm and these disks were polished to have final thicknesses of ∼0.83 mm.

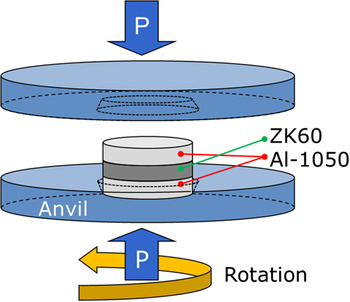

The processing of these materials was conducted using a quasi-constrained HPT facility Reference Figueiredo, Cetlin and Langdon31,Reference Figueiredo, Pereira, Aguilar, Cetlin and Langdon32 at room temperature in a conventional manner Reference Kawasaki and Langdon33 except that the pressing simultaneously involved two separate materials. Thus, separate disks of the Al and Mg alloys were placed in the order of Al/Mg/Al into the depression on the lower anvil. It should be noted that the stacking of metal disks was prepared without using any glue or metal brushing treatment. A schematic illustration of the sample set-up for HPT processing is shown in Fig. 1 where a ZK60 magnesium alloy is placed between two Al-1050 disks. Reference Ahn, Zhilyaev, Lee, Kawasaki and Langdon30 Two separate piles of three disks were processed through HPT under an applied pressure, P, of 6.0 GPa for total numbers of revolutions, N, of 1 and 5 turns using a constant rotational speed of 1 rpm.

FIG. 1. Schematic illustration of the sample set-up for HPT processing. Reference Ahn, Zhilyaev, Lee, Kawasaki and Langdon30

Following processing, the two disks were cut vertically along their diameters to give two semicircular disks for each testing condition. One vertical cross-section from each disk was then polished, chemically etched using Keller's etchant and examined by optical microscopy (OM). Subsequently, values of the Vickers microhardness, H v, were recorded over the vertical cross-sections of the disks after HPT for 1 and 5 turns using a Shimazu HMV-2 facility (Shimazu, Tokyo, Japan) with a load of 50 gf. These individual microhardness values were recorded following a rectilinear grid pattern with an incremental spacing of 0.2 mm and they were used to construct color-coded contour maps displaying the hardness distributions within the vertical cross-sections. For the highly strained disk after 5 turns, an overview of the semicircle disk surface was also observed by OM after slight polishing of the outer rough surface using a Buehler VibroMet 2 (Buehler, Lake Bluff, Illinois) with 0.06 μm colloidal silica suspension under 60% vibration amplitude of the equipment maximum.

The vertical cross-section of the other semicircular disk processed by HPT for 5 turns was polished mechanically and an elemental analysis was conducted using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) in a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM), FEI Nova NanoSEM 450 (FEI Company, Hillsboro, Oregon). The detailed microstructure was investigated by FE-SEM, JEOL JSM-6700F (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), in the peripheral region near the outer edge of the disk on the vertical cross-section after preparing using a broad ion beam cross-section polisher, JEOL IB-09020CP (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), with 6 kV Ar ion beam and ±30° swing angle of specimen stage to minimize beam striations on the strain-free polished surface.

An X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed using a Rigaku UltimaIV XRD (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) on the slightly polished disk surface after HPT through 5 turns. The examination used a Cu Kα radiation with a scanning speed of 3°/min and a step interval of 0.01°. Additional microstructural analysis was conducted by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a spherical aberration (Cs) corrected JEOL JEOM-2100F (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with 200 kV accelerating voltage for a specimen prepared by an in situ lift-out technique using OmniProbe 200 and an Omni gas injection system (Oxford Instruments, Dallas, Texas) in a focused ion beam (FIB), JEOL JIB-4500 (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). High resolution compositional maps were obtained from specific areas of interest using Oxford EDS with Si(Li) detector in a scanning TEM (STEM) mode.

III. EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

A. Overview of the synthesized microstructure in an Al–Mg alloy system after HPT

Figure 2 shows microstructure of the Al–Mg multi-layered disks after HPT at room temperature where (a) provides overview montages of the vertical cross-sectional planes after 1 turn (upper) and 5 turns (lower) taken by OM and (b) and (c) show the microstructures in high magnification taken by OM and SEM, respectively, in the areas of the red rectangles at the center and edge of the disk after 5 turns as indicated in Fig. 2(a): for the OM images, the bright regions denote the Al-rich phase and the dark regions correspond to the Mg-rich phase.

FIG. 2. (a) An overview of the vertical cross-sectional planes of the Al–Mg multi-layered disks after HPT at room temperature under a pressure of 6.0 GPa through 1 turn (upper) and 5 turns (lower); (b) and (c) give the microstructures taken in the areas of the red rectangles after 5 turns as shown in (a) at the center and edge of the disk, respectively.

It is readily apparent that, after HPT for 1 turn as shown in the upper image in Fig. 2(a), the three disks of Al and Mg are bonded together without any segregation and the initial total height of ∼2.5 mm is reduced to an overall thickness of ∼0.83 mm through HPT processing. Due to the bonding of the Al and Mg phases, an Al–Mg multi-layered microstructure is formed throughout the diameter of the disk after HPT for 1 turn. Although layered structures are consistently observed in metals processed by ARB, a significant difference in the HPT disk in Fig. 2(a) is that the Al and Mg phases extend horizontally but the Mg disk is necked and fragmented by the torsional straining so that the magnesium appears as islands. These islands of the Mg phases are slightly larger and thicker close to the center of the disk and they become thinner in the peripheral region. It should be noted that the Al–Mg multi-layered microstructure is different from the earlier report using two semi–circular disks of pure Al and pure Cu where these two phases were separated without any phase fragmentation after processing by HPT for 1 turn under an applied pressure of 6.0 GPa. Reference Oh-ishi, Edalati, Kim, Hono and Horita28

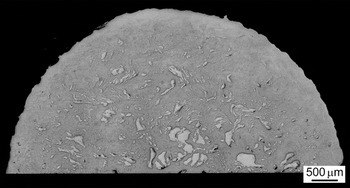

Processing by HPT for 5 turns produces an Al–Mg multi-layered disk with a unique microstructural distribution as shown in the lower image in Fig. 2(a) and in Figs. 2(b) and 2(c). Specifically, two different microstructural features are clearly visible on the vertical cross-section after 5 turns depending upon the radial distance, r, from the center of the disk. First, in the central region at r ≈ 2.5 mm there are relatively thick stacked layers up to ∼200 µm in thickness for the Mg phase between the Al phases. This multi-layered microstructure is shown at a higher magnification in Fig. 2(b) and the microstructural feature is essentially similar to the disk after HPT for 1 turn as shown in the upper image in Fig. 2(a). Second, the remainder of the disk after 5 turns consists of a homogeneously distributed very fine Mg phase confined within an Al matrix and this is especially evident in the SEM micrograph taken at the peripheral region as shown in Fig. 2(c) where the compression direction is vertical. In the SEM image, the darker phase corresponds to Mg and this phase is thin with widths of less than ∼5 µm and it is elongated reasonably normal to the compression axis and aligned in the shear direction. Careful inspection showed that there is a homogeneously distributed fine Mg phase visible from r ≈ 2.5–3.0 mm to the outer edge of the disk where it follows from Eq. (1) that this region received shear strains, γ, from ∼120 to 200 after HPT through 5 turns. A gradation in distribution of Mg layers within the Al matrix is also apparent on the polished disk surface after HPT for 5 turns as shown in Fig. 3 where the brighter phase denotes Mg and the dark region denotes Al. A relatively large size of Mg phases with diameters of 200–300 µm remain in the central region up to r ≈ 2.5 µm and the numbers of small thin Mg phases are equally spread up to r ≈ 3.5–4.0 µm whereas much smaller Mg phases shown in Fig. 2(c) at the peripheral region are not visible at the magnification used for Fig. 3.

FIG. 3. A semi-circle surface of the polished disk after HPT for 5 turns.

Figure 4 shows the results of the EDS analysis at the center of the Al–Mg disk after 5 turns where the scanned window and the interdiffusion curves of the Al and Mg atoms are given at the upper and lower positions, respectively. It is apparent that the Al and Mg atoms diffuse into each other at the interface during HPT and the diffusion length is measured as ∼2.5 µm where the layers of the Mg phase have thicknesses of a few hundred micrometers in the compressive direction at the center of the disk. A similar measurement was also performed for the relatively large elongated Mg phases having thicknesses of ∼5–10 µm at the edge of the disk and an intermixing of Al and Mg atoms was observed with a diffusion length of ∼1–2 µm. The SEM micrographs and EDS analysis demonstrate clearly that there is no evidence for any cavity formation in either the Al or Mg phases throughout the disk where the formation of cavities may occur due to the Kirkendall effect in diffusion couples when the diffusivities are significantly different. Reference Choi, Matlock and Olson34,Reference Ghalandari and Moshksar35

FIG. 4. (a) The EDS results with a scanned microstructure and (b) the diffusion curves of Al and Mg atoms measured at the center of the Al-Mg disk after HPT under a pressure of 6.0 GPa for 5 turns.

B. Microhardness distribution and XRD analysis

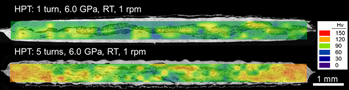

The distribution of microhardness on the vertical cross-sections of the disks is shown in the color-coded contour maps in Fig. 5 for the Al–Mg multi-layered disks processed by HPT for 1 (upper) and 5 turns (lower). The values of the hardness are shown in the key on the right in Fig. 5. For reference, the saturated H v values were ∼63–65 for Al-1050 (Ref. Reference Kawasaki, Alhajeri, Xu and Langdon36) and ∼105–110 for the ZK60 alloy Reference Lee, Lee, Jung, Lee, Ahn, Kawasaki and Langdon37 after HPT for 5 turns under 6.0 GPa and these values were reasonably saturated across the disk diameters without any evidence for the hardness gradations which are often present along the diameters of disks in the early stages of HPT. Reference Kawasaki38,Reference Kawasaki, Figueiredo, Huang and Langdon39 The unique distribution of hardness after 10 turns was described in a recent report. Reference Ahn, Zhilyaev, Lee, Kawasaki and Langdon30

FIG. 5. Color-coded contour maps of the Vickers microhardness for the Al-Mg system after HPT for 1 turn (upper) and 5 turns (lower); the values associated with the various colors are given in the color key at right.

The hardness distribution for the disk after HPT for 1 turn shows a distribution of H v of ∼60–100 throughout the vertical cross-sections and the higher hardness values of ∼90–100 tend to appear on the Mg layers with lower hardness of ∼60 recorded on the Al matrix phase. After 5 turns, it is apparent that the central region in the disk containing the thick layered phases shows a lower hardness of ∼60–70 which is consistent with the hardness of the Al-1050 alloy after HPT for 5 turns. Reference Kawasaki, Alhajeri, Xu and Langdon36 However, there are significantly higher hardness values in the peripheral regions where there is a homogeneous mixture of the fine Al–Mg phases as shown in Fig. 2(c). Thus, in the peripheral region the values of H v reach a maximum of ∼130 which is even higher than ∼105–110 for the ZK60 alloy after HPT for 5 turns.

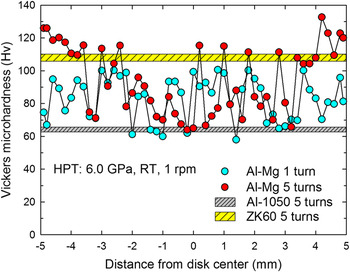

The unexpected high hardness is also visualized when plotting the hardness variations along the diameters of the Al–Mg disks after HPT for 1 and 5 turns and the plot is shown in Fig. 6 where these values were measured at the mid-section in the height direction on each disk. For comparison purposes, the map includes the hardness ranges of ∼63–65 for Al-1050 (Ref. Reference Kawasaki, Alhajeri, Xu and Langdon36) and ∼105–110 for the ZK60 alloy Reference Lee, Lee, Jung, Lee, Ahn, Kawasaki and Langdon37 after HPT for 5 turns in gray and yellow markers, respectively. As was shown in Fig. 5, the hardness values after 1 turn of HPT are within 60–100 and this wide variation within the disk is due to the measurement locations on different phases of Al or Mg. However, it is interesting to note that even the low hardness of H v ≈ 60 after 1 turn in the Al–Mg system is much higher than the minimum hardness of ∼45 for Al-1050 after HPT for 1 turn under 6.0 GPa. Reference Kawasaki, Alhajeri, Xu and Langdon36 Thus, although there is no significant high hardness, the multi-layered structure of the Al–Mg alloy system leads to a rise in the minimum hardness limit after HPT for 1 turn. After 5 turns of HPT, there is no change in hardness at the central region because the multi-layered structure remains whereas there is an exceptional hardness at r > 4 mm including the maximum of H v ≈ 135. This high hardness is higher than the highest attainable value of ∼110 for the ZK60 alloy after HPT for 5 turns and the area exhibiting high hardness is coincident with the region showing the homogeneous distribution of fine Mg phases within the Al matrix as shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 6. The hardness variations along the diameters of the Al–Mg disks after HPT for 1 and 5 turns: the map includes the hardness ranges of ∼63–65 for Al-1050 (Ref. Reference Kawasaki, Alhajeri, Xu and Langdon36) and ∼105–110 for the ZK60 alloy Reference Lee, Lee, Jung, Lee, Ahn, Kawasaki and Langdon37 after HPT for 5 turns in gray and yellow markers, respectively.

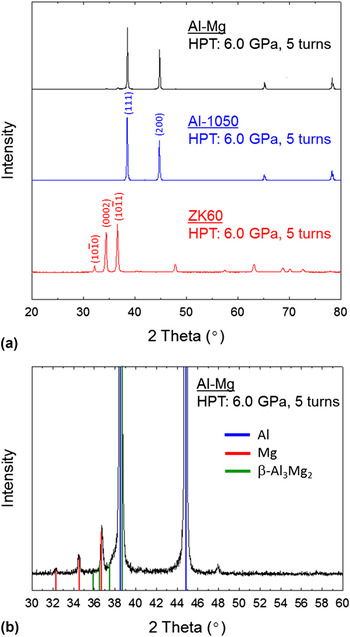

Figure 7(a) shows the XRD patterns for, in descending order, the Al–Mg disk, Al-1050 and ZK60, respectively, after HPT under 6.0 GPa for 5 turns at room temperature and Fig. 7(b) shows the Al–Mg alloy over the limited angular range for 2 theta of 30°–60°. It is apparent from Fig. 7(a) that the processed Al–Mg disk has an XRD pattern that is very similar to Al-1050 but there are weak peaks of pure Mg on the

![]() $(10\bar 10)$

prism plane, (0002) basal plane, and

$(10\bar 10)$

prism plane, (0002) basal plane, and

![]() $(10\bar 11)$

pyramidal plane which are also visible in Fig. 7(b). In addition, an analysis of the relative peak intensities in Fig. 7(b) shows evidence for the formation of a β-Al3Mg2 intermetallic compound in the Al–Mg disk after HPT for 5 turns. It should be mentioned that the XRD measurements were repeated several times at different surfaces by polishing the disk surfaces, thus corresponding to different sections in the height direction, but the β-Al3Mg2 was rarely observed in these measurements. This suggests that the amount of β-Al3Mg2 is less than the detectable limit of ∼5 vol% in the total measured region. The intermetallic β-Al3Mg2 was also observed earlier as very fine decomposed dispersions in Al–5% Mg and Al–10% Mg solid solution alloys when processing by HPT at room temperature under a pressure of 5.0 GPa for 5 turns

Reference Straumal, Baretzky, Mazilkin, Phillipp, Kogtenkova, Volkov and Valiev40,Reference Mazilkin, Straumal, Rabkin, Baretzky, Enders, Protasova, Kogtenkova and Valiev41

but it was not observed in a cryomilled Al–7.5% Mg alloy consolidated by HPT at room temperature at 6.0 GPa for up to 5 turns.

Reference Lee, Zhou, Valiev, Lavernia and Nutt42

$(10\bar 11)$

pyramidal plane which are also visible in Fig. 7(b). In addition, an analysis of the relative peak intensities in Fig. 7(b) shows evidence for the formation of a β-Al3Mg2 intermetallic compound in the Al–Mg disk after HPT for 5 turns. It should be mentioned that the XRD measurements were repeated several times at different surfaces by polishing the disk surfaces, thus corresponding to different sections in the height direction, but the β-Al3Mg2 was rarely observed in these measurements. This suggests that the amount of β-Al3Mg2 is less than the detectable limit of ∼5 vol% in the total measured region. The intermetallic β-Al3Mg2 was also observed earlier as very fine decomposed dispersions in Al–5% Mg and Al–10% Mg solid solution alloys when processing by HPT at room temperature under a pressure of 5.0 GPa for 5 turns

Reference Straumal, Baretzky, Mazilkin, Phillipp, Kogtenkova, Volkov and Valiev40,Reference Mazilkin, Straumal, Rabkin, Baretzky, Enders, Protasova, Kogtenkova and Valiev41

but it was not observed in a cryomilled Al–7.5% Mg alloy consolidated by HPT at room temperature at 6.0 GPa for up to 5 turns.

Reference Lee, Zhou, Valiev, Lavernia and Nutt42

FIG. 7. (a) The XRD patterns showing, in descending order, the Al–Mg, Al-1050 and ZK60 disks processed by HPT under a pressure of 6.0 GPa for 5 turns and (b) the XRD pattern over a limited 2 theta angular range for the Al–Mg disk after processing by HPT under a pressure of 6.0 GPa for 5 turns.

C. Formation of a nanocomposite

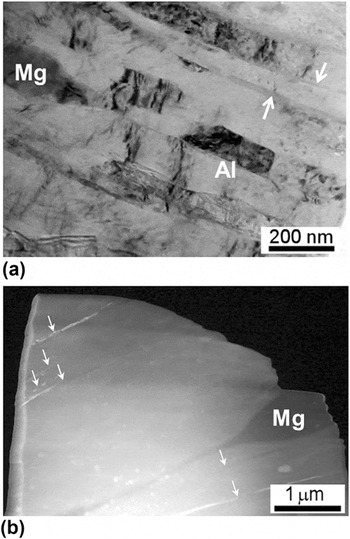

Figure 8 shows a TEM bright-field image in (a) high magnification Reference Ahn, Zhilyaev, Lee, Kawasaki and Langdon30 and (b) low magnification taken at the edge of the Al–Mg multi-layered disk after HPT for 5 turns. From Fig. 8(a), it is apparent that much of the Al matrix phase consists of a layered structure with thicknesses of ∼90–120 nm and these layers contain numerous dislocations subdividing these layers in a vertical sense. The Mg phase labeled in the image has a thickness of ∼150 nm and it has a homogeneous bonding interface without any visible voids. The majority of the measurement region consists of an Al matrix phase and there are several thin layers with an average thickness of ∼20 nm as indicated by the white arrows in Fig. 8(a). An average grain size, d, of ∼190 nm was observed in the Al matrix at the edge of the Al–Mg multi-layered disk after 5 turns. It is important to note that these thin layers are not visible at the interfaces of the Al and Mg phases but instead they form within the Al matrix phase. Specifically, the β-Al3Mg2 phase is formed as thin layers with a very small amount as demonstrated in the XRD analysis and there was no evidence for the formation of a lamellar structure. This is well documented by Fig. 8(b) showing the TEM sample tip after FIB of the 5-turn disk. The thin layers denoted by the white arrows are the β-Al3Mg2 and the large gray phase is a Mg-rich phase which is shown in Fig. 8(a). It is apparent that the β-Al3Mg2 thin layers are distributed irregularly within the Al matrix and some show the discontinuities of the thin layers.

FIG. 8. A TEM bright-field image taken at the disk edge after HPT for 5 turns in (a) high magnification Reference Ahn, Zhilyaev, Lee, Kawasaki and Langdon30 and (b) low magnification showing a layered microstructure consisting of an Al matrix region including one visible Mg phase and thin layers of β-Al3Mg2.

A compositional examination was conducted in STEM mode in the region including the randomly distributed thin layers present in Fig. 8(b) where a dark-field image within the enclosed measurement region marked by a red line is presented in Fig. 9(a) and Figs. 9(b)–9(d) show the corresponding compositional maps for Al, Mg, and O atoms, respectively, taken at the edge of the Al–Mg multi-layered disk after HPT through 5 turns. Several thin layers are visible in Fig. 9 and these thin layers exist within the Al matrix. It is apparent that these thin layers are composed of both Al and Mg atoms and these atoms are homogeneously distributed as demonstrated in Figs. 9(b) and 9(c). Moreover, Fig. 9(d) shows there is no difference in the amount of O at the location of the thin layers so that the thin layers are not the oxide phase. A detailed analysis of the chemical composition was conducted at a thin layer in the 5-turn disk and the measurement location is marked as spectrum 1 in the dark-filed TEM image in Fig. 10 where there is a visible Mg phase. The measured composition records ∼64.01 at.% Al and ∼31.43 at.% Mg with small amounts of O, Zn and Zr of 4.21, 0.32 and 0.02 at.%, respectively, and, following conventional practice, Reference Nayeb-Hashemi and Clark43 it is defined as the intermetallic compound β-Al3Mg2. Thereby, the HPT processing of Al and Mg alloys demonstrates the formation of an intermetallic-based metal matrix nanocomposite. It should be noted that the quantitative analysis was conducted close to the thin layer but within the Al matrix and it demonstrated there was ∼0.2 wt% Mg in the Al matrix which is much higher than the value of ∼0.05 wt% Mg in the commercial-grade Al-1050 alloy. However, it is lower than the maximum solubility of 1.8 wt% Mg in Al at room temperature and thus there is no evidence for the formation of a supersaturated solid solution in the Al–Mg alloy system after HPT for 5 turns.

FIG. 9. (a) A TEM dark-field image and the corresponding compositional maps of (b) Al, (c) Mg and (d) O atoms taken at the edge of the Al–Mg disk after HPT under a pressure of 6.0 GPa for 5 turns.

FIG. 10. A TEM dark-field image showing the point for the chemical composition measurement.

There is a Mg phase with a thickness of ∼500 nm and the homogeneous interface of Al and Mg phases without any voiding in Fig. 10 where the dark-field image displays a thickness of the interface of ∼20 nm. Thus, it appears that there is homogeneous diffusion bonding at the Al/Mg interface with a diffusion length of ∼20 nm and with a fine dispersion of the Mg phase within the Al matrix at the disk edge after HPT processing through 5 turns.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Potential for using HPT to achieve nanocomposite materials

The results described in this report provide the first comprehensive study demonstrating the formation of an intermetallic-based Al matrix nanocomposite through the processing of disks of commercial Al and Mg alloys using conventional quasi-constrained HPT at room temperature. In practice, processing by HPT for 5 turns leads to the unique formation of a multi-layered Al–Mg material at the disk center without the development of any visible voids. The results display a fine dispersion of a magnesium-rich phase in the nanostructured Al matrix with rapid diffusion of Mg in the Al synthesizing intermetallic thin layers and thereby leading to the formation of a nanocomposite in the peripheral regions of the disk. It should be noted that the introduction of fine dispersions of dissimilar metal phases is not common after processing by ARB processing unless the sheet thickness of the hard metal is specially prepared so that it is much less than the thickness of the soft metal. Reference Ghalandari and Moshksar35,Reference Eizadjou, Kazemi Talachi, Danesh Manesh, Shakur Shahabi and Janghorban44–Reference Chang, Zheng, Xu, Fan, Brokmeier and Wu47

The intermetallic compound, β-Al3Mg2, has a low density of ∼2.25 g/cm3 (Ref. Reference Samson48) and a measured high upper yield stress of ∼780 MPa at a temperature of 498 K when testing at a strain rate of 10−4 s−1 (Ref. Reference Roitsch, Heggen, Lipiński-Chwalek and Feuerbacher49) so that it has an excellent potential for serving as a reinforcing agent in Al matrix composites for increasing the hardness, the compressive strength and the wear resistance. Reference Zolriasatein, Khosroshahi, Emamy and Nemati50 In the present experiments, as shown in Figs. 5 and 6, the peripheral region in the processed Al–Mg nanocomposite exhibits a higher hardness than in the processed Al-1050 alloy or the ZK60 alloy and this increased hardness is due to the presence of the nano-layered intermetallic compound. Thus, the β-Al3Mg2 thin layers in the nanostructured Al–Mg alloy system lead to the formation of an intermetallic-based Al matrix nanocomposite after processing by HPT through 5 turns. In a recent study it was shown that an additional 5 turns will provide exceptional hardness in the hybrid Al–Mg system by HPT due to the combination of further grain refinement, solution strengthening, and precipitation hardening. Reference Ahn, Zhilyaev, Lee, Kawasaki and Langdon30 It should be noted that there are at present some limited reports of the production of Al/Mg/Al layered sheets which demonstrate the formation of intermetallic compounds by hot or warm rolling and ARB processing Reference Zhang, Yang, Castagne and Wang23–Reference Lee, Lee and Kwon25,Reference Chen, Kuo, Chang, Hsieh, Chang and Wu45 but there are no reports of either a nanostructured matrix phase or nano-scale intermetallic phases.

The present study demonstrates a potential for using HPT at ambient temperature for synthesizing, over a very short period of time, an intermetallic-based metal matrix nanocomposite in a multi-layered structure having exceptionally high strength through diffusion bonding in the Al–Mg system. It is worth noting that the HPT procedure introduces very high straining within samples but the final bulk solid contains a gradient-type nanostructure. Recently, this type of microstructure is well recognized in many biological systems Reference Chen, McKittrick and Meyers51 and the microstructure is also focused as a new type of structure in engineering materials having a potential for exhibiting excellent mechanical properties. Reference Fang, Li, Tao and Lu52–Reference Lu54 Accordingly, the present study demonstrates significant results and a great potential for using SPD processing for fabricating high-strength nanocomposites. More research is now necessary to confirm the capability of using this powerful technique for synthesizing other metallic systems.

B. The kinetics of diffusion bonding and the growth of an intermetallic compound

In this investigation, the interfaces between the Al and Mg phases are homogeneously bonded throughout the disk after HPT for 5 turns at room temperature. Different diffusion lengths were measured at different locations and the diffusion length, x, was evaluated though the relationship

where D is the diffusion coefficient [= D oexp(−Q/RT) where D o is a frequency factor, Q is the activation energy, R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature] and t is the processing time. Specifically, it is possible to take two examples of x ≈ 2–5 μm for the relatively large Mg phase in the central region of the disk as shown in Fig. 2 and x ≈ 20 nm for the fine Mg phase at the edge of the disk as shown in Fig. 10. Using Eq. (2), it then follows that the values of D are estimated in the range of ∼3.0 × 10−19 to ∼10−14 m2/s after t = 300 s for 5 turns of HPT at 1 rpm.

When synthesizing a new alloy system from separate solid metals by diffusion bonding under a high pressure, it is reasonable to consider the interdiffusion of an Al–Mg binary system where the Mg atoms are accelerated to diffuse into the Al matrix by the effect of the imposed hydraulic pressure. In practice, the compressive pressure is expected to reduce the activation energies for diffusion processes so that, by using fundamental parameters, Reference Frost and Ashby55 the modified diffusivity, D m, is given in the following form:

where σ y is the yield stress and Ω0 is the molar volume of Mg (∼1.4 × 10−5 m3/mol). Thus, Eq. (3) is applicable for calculating the diffusivities of Mg in Al by both grain boundary diffusion and bulk diffusion so that the effective diffusion coefficient under a hydraulic stress, D eff, is obtained using the coefficients of grain boundary diffusion, D gb, and bulk diffusion, D l, in the following form:

where f gb is the volume fraction of grain boundaries Reference Fujita, Horita and Langdon56 given by f gb = 3sδ/d, where s is the grain boundary segregation factor generally taken as ∼1 and δ is the grain boundary width of ∼0.5 nm. Using D o(gb) ≈ 1.4 × 10−4 m2/s and D o(l) ≈ 1.24 × 10−4 m2/s for grain boundary diffusion and bulk diffusion of Mg, Reference Frost and Ashby55 respectively, and the presence of stresses up to ∼0.45 GPa (equivalent to H v ≈ 135) and applying grain sizes of ∼190 nm, Eqs. (3) and (4) give D eff of 1.2 × 10−18–1.5 × 10−14 m2/s at 300–423 K. Considering this level of inevitable temperature rise during HPT attributed to high friction between the sample and anvils, Reference Zhilyaev, García-Infanta, Carreño, Langdon and Ruano57,Reference Pereira, Figueiredo, Huang, Cetlin and Langdon58 the estimated effective diffusivity of Mg under the compressive stress is in excellent agreement with the value of D for diffusion bonding of Al and Mg phases calculated by Eq. (2). It is also worthwhile noting that these values calculated for D and estimated for D eff are reasonably consistent with an earlier report estimating the interdiffusion coefficient in Al–Mg binary diffusion couples even though these earlier measurements were conducted without any compressive pressure but instead at high temperatures of 653–693 K for up to t = 100 h. Reference Kulkarmi and Luo59

Furthermore, the present estimation of effective diffusivity also derives an activation energy of Q ≈ 80 kJ/mol for diffusion bonding of the Al and Mg phases in the Al–Mg system through HPT. As suggested in earlier reports, Reference Edalati, Toh, Iwaoka and Horita19,Reference Oh-ishi, Edalati, Kim, Hono and Horita28 the estimated activation energy should be of the order of ∼1/2 to ∼2/3 of the activation energies of 142 and 135 kJ/mol for lattice diffusion of Al and Mg, Reference Frost and Ashby55 respectively, so that the activation energy is therefore comparable to the value for surface diffusion. This very rapid diffusivity is due to the high population of lattice defects, and especially it is due to the presence of vacancies and vacancy agglomerates which are introduced in metals when processing by SPD techniques such as equal-channel angular pressing Reference Schafler, Steiner, Korznikova, Kerber and Zehetbauer60 and HPT. Reference Setman, Schafler, Korznikova and Zehetbauer61

Accordingly, it appears that the rapid diffusion forms nano-layers of the intermetallic compound β-Al3Mg2 in the nanostructured Al matrix near the edge of the disk after HPT for 5 turns. The growth kinetics of intermetallic phases under diffusion growth may be calculated from the following relationship Reference Brennan, Bermudez, Kulkarni, Sohn, Sillekens, Agnew, Neelameggham and Mathaudhu62 :

where Y is the thickness of the intermetallic layer, k is the growth constant, and t is the time of formation which is equivalent to the processing time. The temperature dependence of the growth of the intermetallic layers should follow an Arrhenius relation so that k is expressed by a relationship of the form

where k 0 is a pre-exponential factor.

The present experiments reveal an intermetallic layer thickness of Y ≈ 20 nm after t = 300 s for 5 turns by HPT as shown in Figs. 8–10 and, using Eq. (5), this leads to a growth constant of k ≈ 1.2 × 10−9 m2/s for the β-Al3Mg2 nano-layers. In addition, using Eq. (6) with Q ≈ 80 kJ/mol and taking temperatures from 300 to 423 K to allow for processing at room temperature and the temperature rise during HPT processing, the pre-exponential constant is estimated as k 0 ≈ 102–105 m2/s for the β-Al3Mg2 nano-layers under these experimental conditions. The activation energy for formation of the β-Al3Mg2 nano-layers of Q ≈ 80 kJ/mol is consistent with the reported value of ∼86 kJ/mol for the formation of the β-Al3Mg2 intermetallic phase using a solid-to-solid diffusion couple technique at elevated temperatures of 573–673 K. Reference Brennan, Bermudez, Kulkarni, Sohn, Sillekens, Agnew, Neelameggham and Mathaudhu62,Reference Brennan, Bermudez, Kulkarni and Sohn63 The measured k 0 value in the present analysis is much higher than the reported value of k 0 ≈ 2 × 10−6 m2/s Reference Brennan, Bermudez, Kulkarni, Sohn, Sillekens, Agnew, Neelameggham and Mathaudhu62,Reference Brennan, Bermudez, Kulkarni and Sohn63 and this difference is due to the rapid diffusion associated with the enhanced concentration of vacancy-type defects due to the HPT processing. This conclusion agrees with recent reports demonstrating that the enhanced atomic diffusion in nanostructured material after equal-channel angular pressing (ECAP) is attributed to the introduction of extra free volumes due to the high population of lattice defects in the nanostructure. Reference Divinski, Ribbe, Baither, Schmitz, Reglitz, Rösner, Sato, Estrin and Wilde64,Reference Divinski, Reglitz, Rösner, Estrin and Wilde65

It is reasonable to conclude from these results that the deformation-induced rapid diffusion not only bonds the Al and Mg phases to give a multi-layered structure but also becomes the driving force for the formation of the β-Al3Mg2 intermetallic nano-layers at room temperature. Thus, an intermetallic-based Al matrix nanocomposite is introduced around the periphery of the Al–Mg alloy during processing by HPT through 5 turns. The present results are unusual and they suggest there may be a considerable potential for using processing by HPT to synthesize new alloy systems from simple metals and alloys. Further investigations are now needed to fully explore the potential and limitations of this approach and especially to examine the detailed microstructural changes that may be produced in different metal systems.

V. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

-

(1) Conventional HPT processing was performed successfully by processing through 5 turns at room temperature to produce an Al–Mg alloy system having unique microstructural distribution within the disk through the diffusion bonding of separate Al and Mg disks. Following processing, the microhardness and the deformed microstructure were examined, including the compositions at selected areas, to evaluate the feasibility of using HPT for the formation of intermetallic compounds through diffusion bonding.

-

(2) The results demonstrate the formation of an intermetallic compound, β-Al3Mg2, in the form of nano-layers in the Al matrix and the synthesis of an intermetallic-based Al matrix nanocomposite in the highly deformed region around the periphery of the disk after processing by HPT. Overall, different scales of an Al-Mg multi-layered structure are formed with large phases at the disk center and with phases in the submicrometer level at the disk edge after processing for 5 turns.

-

(3) The effective diffusion of Mg atoms in the Al matrix is estimated under compression and the value is in excellent agreement with the calculated diffusivity for diffusion bonding of Al and Mg phases in the processed Al–Mg alloy system. Moreover, the rapid diffusion leads to a low activation energy for diffusion bonding and this activation energy is also responsible for the formation of a β-Al3Mg2 intermetallic compound. This rapid diffusion requiring low activation energy is due to the severely deformed microstructure and the excess of vacancy-type defects introduced by HPT processing.

-

(4) The results demonstrate a considerable potential for using HPT processing for the development of new alloy systems. Further investigations are now needed to fully explore these possibilities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the NRF Korea funded by MoE under Grant No. NRF-2014R1A1A2057697 (M.K.), in part by the NRF Korea funded by MSIP under Grant No. NRF-2012R1A1A1012983 (B.A.), in part by the Russian Science Foundation under Grant No. 14-29-00199 (A.P.Z.), in part by the NSF of the United States under Grant No. DMR-1160966 and in part by the European Research Council under ERC Grant Agreement No. 267464-SPDMETALS (T.G.L.).