Introduction

Steve Jobs, Apple’s charismatic leader, successfully led the company for almost a decade, based on the innovative and effective strategy of designing a user-friendly personal computer. However, in March 1985, major troubles in the Mac division, which he headed, led to his resignation. While at times the company’s strategy was compatible with the market, Jobs’ interpersonal charisma was colored by his overreliance on intuition and the frequent dismissal of others’ opinions, to the point of being blind to facts and creating a ‘reality distortion field’ (Isaacson, Reference Isaacson2011: 117). By 1997, when he returned to a downtrodden Apple as its CEO (Chief Executive Officer), Jobs had learned his lesson well. Recognizing the limitations of interpersonal leadership and firm strategy alone to help fulfill his desire to ‘build an enduring company’ (Isaacson, Reference Isaacson2011: 567), Jobs built a suitable organizational infrastructure by delegating clear authority to the managers he selected, especially in the areas where he was less competent, giving them full rein to lead processes and realize their individual potential. Significant structuring ensued in: operations (led by Tim Cook), new product development and customer-centered marketing (led by Jobs), design (led by Jonathan Ive) and in Apple retail stores (led by Ron Johnson). Apple’s subsequent consistent success to introduce innovative products in new markets cannot be attributed to a single individual, however talented. As Jobs realized, while both strategy and interpersonal skills are important, these levers work best when combined with significant organizational structuring activities.

The case of Apple and Steve Jobs highlights the need for a more integrated leadership approach – one that recognizes multiple levers or processes by which leaders can affect organizational outcomes (Yukl, Reference Yukl1999; Van Knippenberg & Sitkin, Reference Uygur2013). Specifically, this case reflects the contribution of structuring, that is creating the necessary mechanisms needed for dividing, allocating and integrating the work through organizational structures and processes (Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1979), as well as instilling high motivation (Collins & Porras, Reference Conger and Kanungo1994).

The literature on organizational leadership includes 66 Theories of Leadership (Dinh, Lord, Gardner, Meuser, Liden, & Hu, Reference Droge, Jayaram and Vickery2014). As Yukl remarked, it is ‘difficult to see the forest for the trees’ (Reference Yukl2006: 494). To try to envisage the whole forest, we focus on the most prevalent theories. As reviewed in several studies (Dinh et al., Reference Droge, Jayaram and Vickery2014; Day, Fleenor, Atwater, Sturm, & McKee, Reference Day, Fleenor, Atwater, Sturm and McKee2014), these are charismatic-transformational leadership at the micro level and strategic management theory (including strategic leadership, top management team and the upper echelon approaches) at the macro level (Boal & Hooijberg, Reference Boal and Hooijberg2001; Vera & Crossan, Reference Vera and Crossan2004).

As Yukl noted, ‘Most leadership theories are beset with conceptual weakness’ (Reference Yukl2006: 493). Despite their many contributions, each of the most prevalent approaches has notable ‘blind spots’ and relies on biased assumptions. Moreover, the macro–micro polarization of major leadership theories overlooks important meso perspective processes, such as structuring (Dinh et al., Reference Droge, Jayaram and Vickery2014), which leaders can use to attain more compounded and sustained effects on organizational outcomes (Aguinis, Boyd, Pierce, & Short, Reference Aguinis, Boyd, Pierce and Short2011). Structuring extends the leader’s reach – both in time and space: its effects both pervade the entire organization and are more robust than a leader’s charisma, the effects of which can be significant, but short-lived.

The goal of this paper is to propose an integrative theoretical framework – value-creating leadership (VCL) – which provides what is missing from the theory of organizational leadership. VCL combines transformational leadership at the micro level and strategic leadership at the macro level, along with architectural leadership at the meso perspective to create a unified model of corporate leadership.

Following Selznick (Reference Schein1984), we define a leader as one who shapes the organization’s purpose and works to realize it by defining policies and building the means for this realization – through the institutional embodiment of the purpose and policies embedded in the organizational structure. This definition applies to all levels of the organization, while each unit leader is subordinate to the purpose and policies defined by the CEO. The main leader’s lever for exercising influence at the macro level is shaping the organizational vision and strategy. The main lever at the meso perspective is structuring, while the main lever at the micro level is interpersonal influence. The definition we use highlights leadership as a purposeful process. This definition, as well as the VCL framework we develop, place a special emphasis on processes – shaping, influencing and particularly structuring – but, at the same time, views these processes as an integrated entity that directs the organization and creates value. Thus, the name VCL indicates the desired outcome of the leadership process– to enhance organizational value – to ensure that the leadership process is directed – in advance – in the right direction. Moreover, connecting the leadership process to organizational outcomes contributes to the leadership literature. As Dinh et al. put it, ‘a key aspect of leadership is to structure the way that the inputs of others are combined to produce organizational outputs’… and it has ‘been successful in organizing leadership research’ (Reference Droge, Jayaram and Vickery2014: 37).

We begin by analyzing the weaknesses of the micro and macro perspectives; then we identify the conceptual gap between them and note the importance of closing this meso gap, after which we propose architectural leadership as a way of narrowing the gap. Finally, we present a theoretical model that combines the three perspectives into one integrated theory (VCL) and suggest directions for future research.

Existing approaches: interpersonal leadership and strategic management

Herein, we briefly review key micro and macro leadership models and examine their main assumptions in order to show the need for a more integrated approach, elaborated on from the existing approaches.

There is an extensive body of literature on the personal influence of leaders (for a review, see Bass, Reference Bass2008). For example, one prominent micro approach highlighting the personal impact of a leader is the full range leadership theory (Bass, Reference Bass1985; Bass & Avolio, Reference Bass and Avolio1990). Aspects of transformational leadership – idealized influence (initially defined as ‘charisma’); inspirational motivation; individualized consideration; intellectual stimulation – are the most influential among the entire range of behaviors included in the model. These elements influence the emotional and symbolical levels, lead to higher commitment among followers and cause people to act above and beyond the call of duty (Bass, Reference Bass1985; Eden, Reference Finkelstein and Hambrick1990). The link between transformational leadership and effectiveness has received strong empirical support (e.g., Lowe, Kroeck, & Sivasubramaniam, Reference Lowe, Kroeck and Sivasubramaniam1996; Waldman, Ramirez, House, & Puranam, Reference Waldman, Ramirez, House and Puranam2001). Another example of a micro leadership model – that of trait theory – currently focuses on a small number of basic attributes, such as the ‘Big Five (attributes) model’ (Barrick & Mount, Reference Barrick and Mount1991). Research in this tradition shows that a single attribute only rarely has a significant predictive power regarding a particular performance criterion. Furthermore, attributes depend on the social situation and may change over time (Mischel, Reference Mischel1968; Hogan, Reference Hogan1991).

Recently, there has been a growing awareness of the possibility that too much weight has been attributed to the personality and direct influence of the leader (Popper, Reference Popper2012). For instance, social scientists have noted a phenomenon known as the fundamental attribution error, in which people excessively attribute decisive weight to certain individuals, to the point of sometimes even ignoring contextual factors (Ross, Ambile, & Steinmatz, Reference Rosenbloom1977). Several organizational researchers have suggested that this universal perceptual bias has perhaps excessively magnified the importance of charismatic leaders in explaining what goes on in organizations (Conger & Kanungo, Reference Copeland, Koller and Murrin1998; Collins, Reference Collins and Porras2001; Yukl, Reference Yukl2008). Other researchers have discussed the power and dangers inherent in charismatic leadership, indicating the demise, or at least diminishing, of organizations after the departure of the charismatic leader (Samuel, Reference Ross, Amebile and Steinmatz2012). Furthermore, narcissistic leaders radiating a sense of vitality are, in many cases, charismatic. However, they may become problematic and unhelpful to their organizations – being preoccupied with their own emotions, tending to devalue others and abusing their power (Stein, Reference Sillince and Shipton2013).

The main assumption underlying much of leadership research at the micro level is that most of the leader’s influence stems from his or her personality and behavior (Day et al., Reference Day, Fleenor, Atwater, Sturm and McKee2014; Dinh et al., Reference Droge, Jayaram and Vickery2014). Such an influence requires the presence of the leader. In other words, the influence is essentially based on interpersonal interaction (only exceptionally charismatic leaders can overcome this constraint). Therefore, this view is more suitable for small organizations, such as start-ups. Indeed, most studies have almost exclusively examined leadership in small groups (Vera & Crossan, Reference Vera and Crossan2004).

However, time constraints and the physical and psychological distance between many leaders and their followers often diminish the manager’s capacity to be an ongoing and available source of interpersonal influence (Yukl, Reference Yukl1999, Reference Yukl2006) – a limitation that becomes more severe given the centrality of large and geographically dispersed organizations in today’s environment. Such settings require a more pervasive and enduring influence, which interpersonal leadership is ill equipped to offer – an influence that is not conditional upon the personal characteristics of CEOs and their behavior. Moreover, beyond the critique of transformational leadership theory provided by Van Knippenberg and Sitkin (Reference Uygur2013), explanations of organizational effectiveness relying on claims relevant to the micro perspective are not broadly applicable (Yukl, Reference Yukl2006, Reference Yukl2008).

Given the above, the assumption we propose is that in large organizations, and in order for leaders’ impact to permeate all levels of the organization, interpersonal influence needs to be supplemented by other means that produce a broader impact. Thus, an approach that provides a solution to the disadvantages of the micro perspective should tackle the following issues: (i) How can leadership be available to followers in large organizations? (ii) How can leadership impact be maintained on a large scale without being solely dependent on certain prominent (charismatic) leaders?

Macro leadership theories can be represented by the strategic management approach (e.g., Tushman & Romanelli, Reference Tushman, Newman and Romanelli1985; Hambrick, Reference Hambrick1989, Reference Hambrick2007; Finkelstein & Hambrick, Reference Foster and Kaplan1997; Mintzberg, Ahlstrand, & Lampel, Reference Mintzberg, Ahlstrand and Lampel1998). Strategic management approach emphasizes the view of the organization as a whole and therefore focuses on organizational strategy and performance, unlike most leadership theories that tend to focus on the individual and the team level. The organization’s strategy is formulated by its top executives based on monitoring the environment and identifying opportunities and threats, as well as on recognizing the organization’s strengths and weaknesses. The main assumption underlying such approaches is that the organization’s success depends primarily on a suitable strategy (Yukl, Reference Yukl2006).

Instead of seeing strategy as an abstract concept that tends to be sustained even if there is a managers’ turnover, strategic management focuses on the CEO and the top executive team. According to Hambrick, it ‘put top managers back in the strategy picture’ (Reference Hambrick1989: 5) in the late 1980s. However, strategic management is a broad field, not a unified theory. It deals mainly with management and only a few strategic management scholars refer to leadership (e.g., Hambrick, Reference Hambrick1989, Reference Hambrick2007; Finkelstein & Hambrick, Reference Foster and Kaplan1997; Vera & Crossan, Reference Vera and Crossan2004). While leadership approaches focus on employees and organizational development – through granting employees meaning and purpose (House & Adita, Reference House, Rousseau and Thomas-Hunt1997) and fostering managers as leaders (Boal & Hooijberg, Reference Boal and Hooijberg2001) – most strategic management models focus on control and supervision, and tend to overlook employee motivation and commitment. The result is insufficient attention to employees, including middle management, and to organizational vision, culture and behavior patterns.

Moreover, by and large strategic management research tends to give priority to strategic analysis and planning (Porter, Reference Porter1980), and especially to economic aspects, placing less importance on strategy implementation (Raes, Heijltjes, Glunk, & Roe, Reference Rappaport2011). Furthermore, it tends to emphasize looking outward, at the organization’s external environment, to ensure that the organization is compatible with the environment, has a competitive advantage and is in a position to exploit opportunities and improve its performance. It pays less attention to intra-organizational issues, such as developing new capabilities (Hamel & Prahalad, Reference Hamel and Prahalad1989), which are likely to enable the planning and application of new strategic components, rather than extrapolating from extant directions (Mintzberg, Ahlstrand, & Lampel, Reference Mintzberg, Ahlstrand and Lampel1998). This abstraction fails to explain the actual means and processes (Dinh et al., Reference Droge, Jayaram and Vickery2014) available for managers to bring about improved performance.

Given the above, we follow the approach of strategic leadership, as supported by the entrepreneurial and learning schools of thought (Mintzberg, Ahlstrand, & Lampel, Reference Mintzberg, Ahlstrand and Lampel1998). From the entrepreneurial schools of thought, we have adopted the theme of vision, believing that the focus should be on the macro perspective of leading the organization in the entrepreneurial spirit of the metaphor ‘clock building, not time telling’ (Collins & Porras, Reference Conger and Kanungo1994). From the learning schools of thought, we have adopted the theme of the learning organization rather than focusing on a single core process of organizational learning (Senge, Reference Selznick1990a).

Consequently, the proposed assumption is that in the dynamic markets of our time, suitable strategy does not suffice; the leader must develop dynamic capabilities that will facilitate strategy implementation and tailor them to the changing strategy. Thus, an approach that provides a solution to the disadvantages of the macro perspective should tackle the following issues: (i) strategy implementation (beyond the design phase); (ii) orientation toward internal organizational issues, rather than excessive external focus; and (iii) constant examination of the status quo.

The prevalent partial and biased assumptions expressed by the micro and macro perspectives derive mainly from being limited to a single organizational level, thereby resulting in incomplete leadership approaches. To overcome this bounded perspective and develop a complete leadership approach, this impediment must be addressed.

The lacuna in the literature

While we stress the assumptions and potential blind spots of the micro and macro leadership perspectives and propose alternative assumptions, it is also worthwhile to point out a broader problem in the field. Often promoted by economic-oriented research and psychology research, respectively, the macro and micro leadership approaches tend to be unrelated to one another. As Yukl observed, ‘the leadership research has been characterized by narrowly focused studies, with little integration of findings from the different approaches’ (Reference Yukl2006: 500). This limitation calls for meso approaches to provide the necessary ‘glue’ (House, Rousseau, & Thomas-Hunt, Reference House and Adita1995) to integrate several levels of analysis (Aguinis et al., Reference Aguinis, Boyd, Pierce and Short2011; Day et al., Reference Day, Fleenor, Atwater, Sturm and McKee2014; Dinh et al., Reference Droge, Jayaram and Vickery2014). Given the above and the alternative assumptions, the research question is as follows: how is it possible to integrate micro and macro perspectives into a comprehensive organizational leadership approach that will be effective in large organizations facing rapidly changing environments?

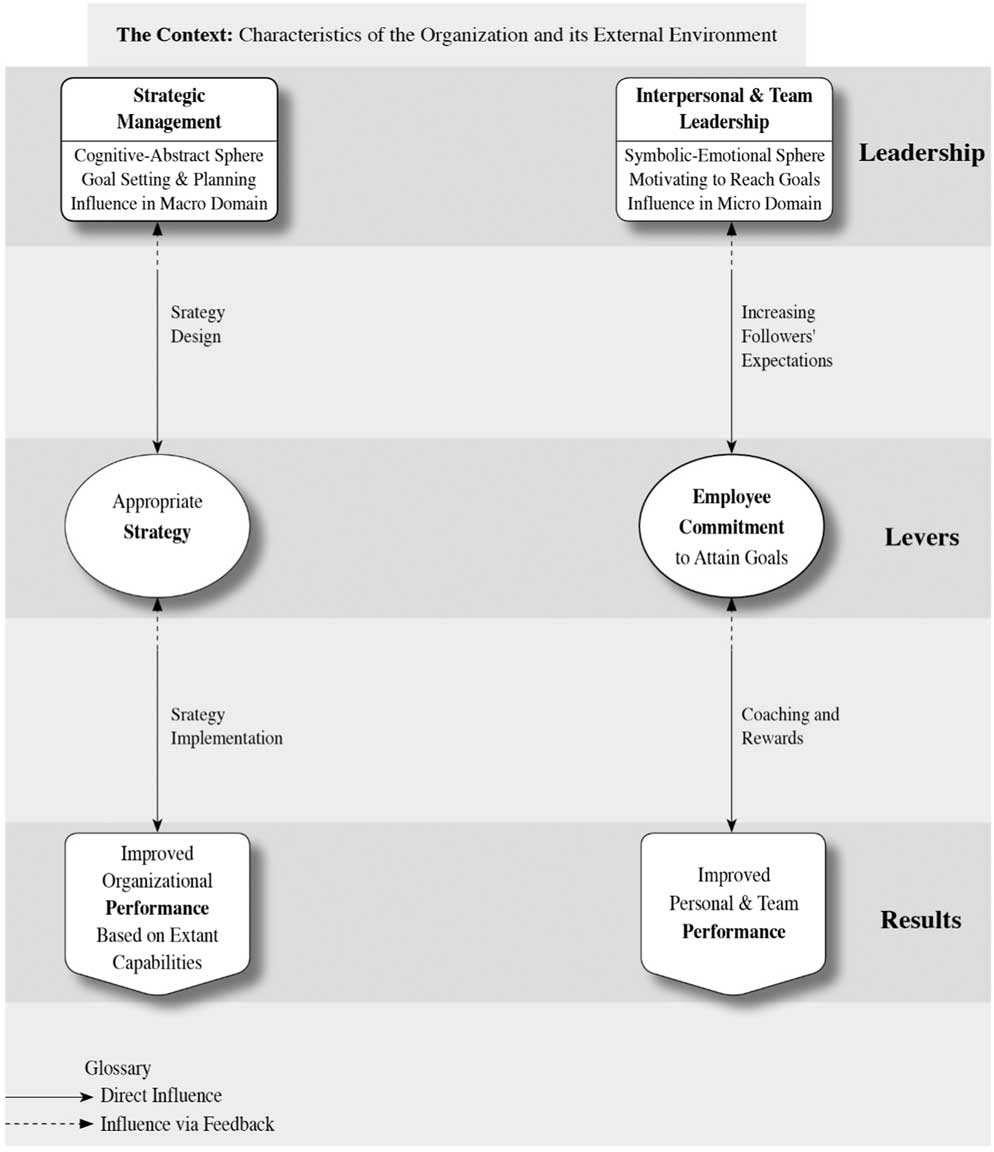

Figure 1 describes the different foci of existing leadership approaches and the levers they highlight for leaders to obtain the desired results. As noted, micro approaches center on the psychology of leadership and their followership, internal aspects of the organization, short-term influences and on individuals’ outcomes such as motivation and expectations. By contrast, the macro perspective highlights the external organizational environment, the firm’s long-term positioning and competitive advantage within its environment, as well as firm performance.

Figure 1 Leadership: micro and macro perspectives in organizations

The figure displays the existing aspects, but also implies the missing ones. Improved personal and team performance do not necessarily lead to improved organizational performance, especially when the leadership is not aligned with the firm’s strategy. Moreover, a strategy based solely on extant organizational capabilities does not fully exploit the organization’s potential. Furthermore, the existing micro and macro approaches focus on a particular goal – to transform expectations and to formulate an appropriate strategy – respectively. Clearly missing are the organizational means required to attain the firm’s strategic goals (Selznick, Reference Schein1984). Thus, the main problem with micro and macro leadership perspectives is not that they are inaccurate or trivial, but that they are simply incomplete (Hitt, Beamish, Jackson, & Mathieu, Reference Hitt, Beamish, Jackson and Mathieu2007; Day et al., Reference Day, Fleenor, Atwater, Sturm and McKee2014). Adhering to a single polar perspective creates distortion and even blindness to other possibilities (Quinn, Reference Quinn1988), missing the opportunity to achieve integration at a level that is beyond the polar extremes (Watzlawick, Weakland, & Fish, Reference Watzlawick, Weakland and Fish1974; Collins & Porras, Reference Conger and Kanungo1994).

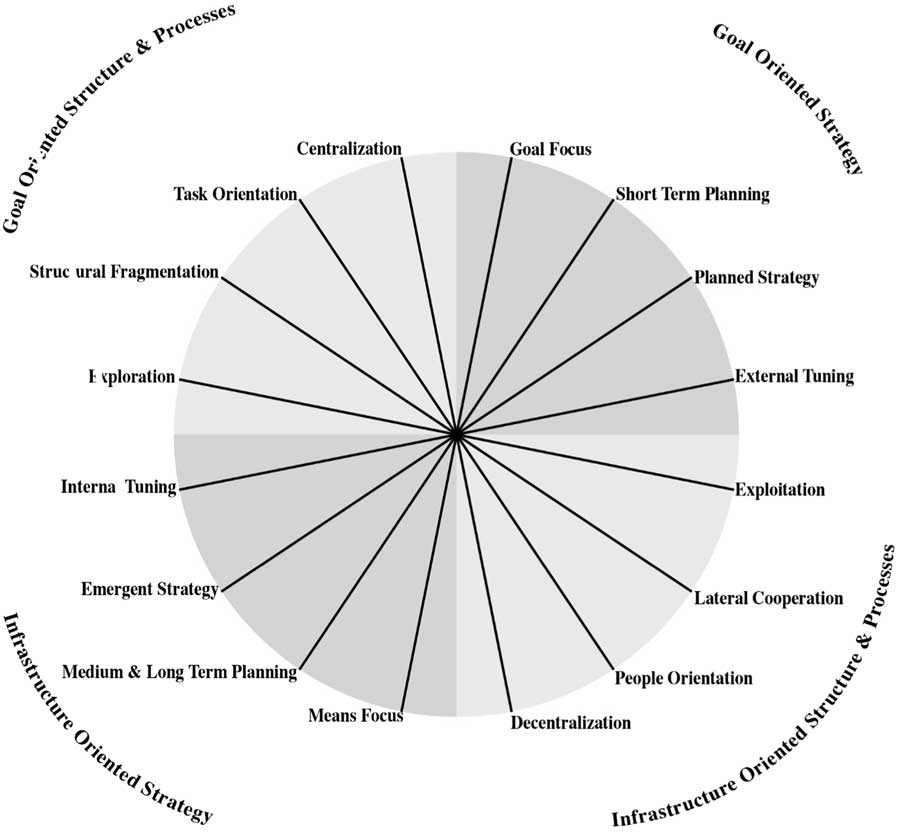

Managers are plagued by many inherent conflicts that seem insoluble using the prevalent management and leadership approaches. These include conflicts between long-term and short-term considerations, between the local perspective and the overall perspective, between intra-organizational and extra-organizational considerations, opposing outlooks, contrasting interests and more. The complexities are many and varied. Only too often, the conflicting demands and problems inherent in the organization are responsible for the low achievements of many businesses, causing a high rate of organizational demise, even among those firms appearing in the Fortune 500 and Forbes 100 lists (De Geus, Reference Deming1997; Foster & Kaplan, Reference De Geus2001; Morris, Reference Morris2009). Figure 2 represents the main dilemmas that we perceive to be the most prevalent in the process of leading organizations.

Figure 2 Conflicting organizational needs

The necessity of addressing these issues stems from the understanding that most management problems involve multilevel phenomena. ‘Multilevel research is one way to promote the development of a more expansive management paradigm’ (Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Beamish, Jackson and Mathieu2007: 1385).

Hence, an approach that solves the theoretical lacuna and deals with the contradictory demands between the micro and macro perspectives should meet the following four requirements: first, it is necessary to narrow the gap between the micro and macro perspectives, so the leader can deal with the complex and contradictory organizational realities (as opposed to being locked into the narrow micro/macro perspectives). Second, it is important to provide a system-wide explanation for organizational effectiveness (as opposed to a micro perspective-based explanation). Third, balanced human resource management is imperative: avoiding excessive focus on individuals, often at the expense of the mission (as is customary in interpersonal leadership) or excessive focus on the task, often at the expense of individuals, sufficing with supervision and control (as is customary in strategic management). Finally, it is necessary to harness employees and managers to the organizational targets, rather than taking a local view (as in a micro perspective, at the expense of a strategic view), or an external view (as in a macro perspective, at the expense of motivating employees).

Before we introduce the VCL as a more unified model of organizational leadership that complements the existing approaches, we discuss the meso perspective architectural leadership approach.

The Answer to the Middle Ground: Architectural Leadership

The architectural leadership approach offers a solution to the existing gap between micro and macro perspectives, through leadership activity in the middle ground existing between the two. Because we conceptualize leadership as a process, research should not suffice with leaders and their characteristics, but rather focus on organizational processes (Day et al., Reference Day, Fleenor, Atwater, Sturm and McKee2014; Dinh et al., Reference Droge, Jayaram and Vickery2014). We particularly stress organizational structuring of ‘the sum total of the ways in which the organization divides its labor into distinct tasks and then achieves coordination among them’ (Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1979: 2). Importantly, architectural leadership focuses on processes that cut across the vertical organization’s hierarchy and connect the departments in the various divisions participating in the execution of a joint procedure, thereby promoting cooperation between the departments and integrating the mechanisms for carrying out coordinated work.

To achieve the organization’s goals, the processes are geared to suit the environment. They include organization-wide managerial processes such as operations, knowledge management, control reporting and feedback, human resources management, as well as interorganizational managerial processes that support the management of relations with the environment (Nalebuff & Brandenburger, Reference Nalebuff and Brandenburger1996; Lavie, Reference Lavie2006). There is nothing improvised or casual about these processes; they are structured and methodical, thus helping institutionalize knowledge and changes. They embody and transmit the leader’s policy, diffusing it through management layers, incorporating it into the daily behavior of the organization’s members and creating desired patterns of activity. In this way, these processes leverage the influence of leaders beyond their direct personal effect, enabling them to harness the entire organization, or at least a considerable part of it, to achieve their goals. The contribution of processes to the organization’s performance has been confirmed in various studies (Droge, Jayaram, & Vickery, Reference Eden2004; Watson, Blackstone, & Gardiner, Reference Watson, Blackstone and Gardiner2007).

Just as an architect designs a building and is responsible not only for the planning, but also for its execution, the architectural leader designs the functional and behavioral organizational space in a way that will achieve the organization’s goals. The architectural leader structures the important processes that derive from the organization’s strategy and express the organization’s capabilities, which are an important source of sustainable competitive advantage (Barney, Reference Barney1991; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Stein1997). We are not talking about a one-time activity, but about the ongoing improvement and adaptation of the organization’s design to the environment and circumstances, similar to the way in which the interior designer, and particularly the urban architect and landscape architect, go about their work. A complex architectural undertaking is not meant to be the work of just one person, but that of a team, with the chief architect dividing the project into subprojects, delegating authority, guiding the lower-ranking architects and ensuring that their work integrates into an overall completeness. Contrary to the concept of management, which accepts the given context and surrenders to it (Bennis, Reference Bennis1989: 25), architectural leadership strives to master the context in order to improve the organization’s performance.

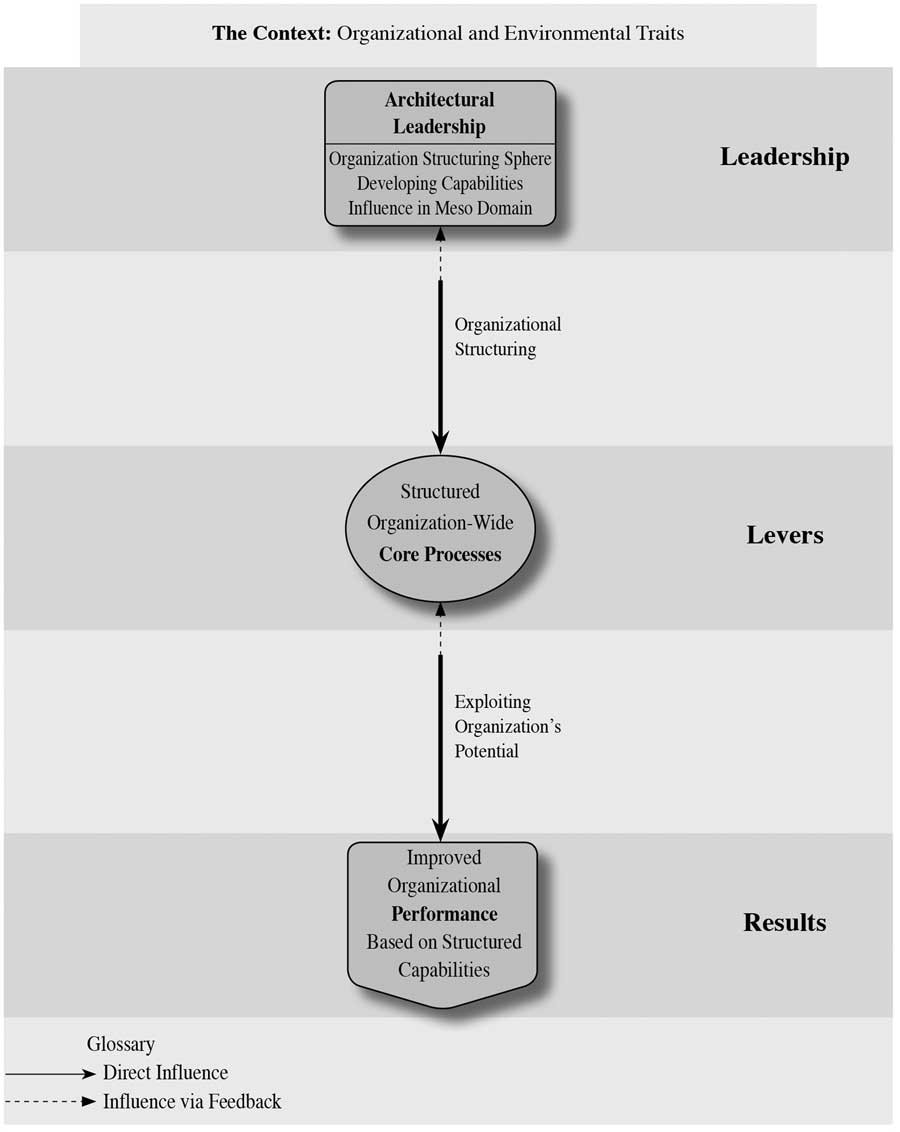

The process through which the architectural leader influences the organization’s performance is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Architectural leadership: meso perspective in organizations

Organization-wide structuring is particularly important for core processes that are vital to achieving goals such as knowledge management and organizational learning. However, leveraging the knowledge embedded in the firm and transferring it across the firm must first overcome many difficulties (Uygur, Reference Tushman and Romanelli2013). For example, Nonaka (Reference Nonaka1994) showed that organizational learning requires the integration of many specific knowledge resources, as well as the transformation of personal knowledge into organizational knowledge (termed externalization), thereby calling for an organization-wide process.

Employees and managers participating in formulating and implementing an organization-wide process that cuts through divisions constitute a community of knowledge and practice. The ongoing dialogue within the community helps externalize personal knowledge, fusing knowledge and creating new knowledge, thanks to the different perspectives of the participants in the common process (Davenport & Prusak, Reference Davenport and Prusak1998). Each core process has strategic significance: each is built out of a strategic need or necessity and aims at creating value. Employees involved in the operation of a successful process ponder the meaning of it, which contributes to the cognitive aspect of learning. At the same time, they also experience success in the implementation of the strategy, interpreting this as evidence that they are in control and on the right path. This elicits pleasant, positive feelings that assist organizational learning (Sillince & Shipton, Reference Shamir2013).

According to the resource-based view criteria, a core process is an organizational capacity that is meant to contribute to the organization’s competitive advantage (Barney, Reference Barney1991), and embodies accumulated knowledge as well as operational experience. It is important to note that instituting, maintaining and developing organizational capabilities requires an architectural leadership constellation in which all managers are responsible for developing an infrastructure that will serve the organization’s strategy in their particular area. This responsibility to improve operations performance as part of the implementation of the organization’s strategy, reflects the importance assigned to middle managers (Van Rensburg, Davis, & Venter, Reference Van Knippenberg and Sitkin2014). At the same time, since the perspective of architectural leadership is organizational rather than local, the CEO is the final arbiter and it is his or her responsibility to approve the definition and the planning of each proposed organization-wide process. Still, the core process combines top-down knowledge embodied in its architectural design, following an object-based knowledge management approach, with bottom-up knowledge emerging as a result of interaction within the community of practice, following a community-based knowledge management approach (Lee, Dun-Hou Tsai, & Amjadi, Reference Lee, Dun-Hou Tsai and Amjadi2012).

The indicated four requirements – which are not sufficiently satisfied in the middle ground – are suggested to be dealt with based on several management approaches, with a few adjustments. First, we adopted the core competencies approach of Hamel and Prahalad, but the competencies we suggest are core processes, rather than ‘a bundle of skills and technologies’ (Reference Hamel and Prahalad1994: 223). Second, we adopted the routines approach of Nelson and Winter (Reference Nelson and Winter1982) and the dynamic capabilities approach of Teece, Pisano, and Shuen (Reference Stein1997). In our view, however, the capabilities are organization-wide, not micro-processes, and are built through leader guidance, not through bottom-up dynamics. Third, we adopted Deming’s Total Quality Management (TQM) (Reference Dinh, Lord, Gardner, Meuser, Liden and Hu1986), but perceive the structuring effort as being focused rather than dispersed. Fourth, we adopted the reengineering approach of Hammer and Champy (Reference Hammer and Champy1993), and propose that the development is a gradual process, rather than a revolutionary process.

Thanks to the above merits, architectural leadership enables large companies to combine their scale advantages with a value-creating focus on their customers, and to acquire the effectiveness usually only achieved by small companies. The examples of companies such as GE, Toyota, Fedex and Dell show the benefits of structuring processes, indicating the structuring of processes as a central aid to the ongoing improvement of organizational performance. Indeed, there is much evidence on companies that managed to retain their leading position for many years, even after the charismatic or transformational founding leader had long since left the arena (Schein, Reference Samuel1992; Collins & Porras, Reference Conger and Kanungo1994).

An Integrative Model: VCL

Similar to Jobs, Jack Welch established effective organizational processes at General Electric, including processes for managing human resources, in what he fondly referred to as his ‘people factory’ (Welch & Byrne, Reference Welch and Byrne2001, Chapter 11). The success of General Electric under the leadership of Jack Welch illustrates the integration by a leader of the macro, micro and meso perspectives: (i) the macro perspective of determining the organization’s direction; (ii) the micro perspective of employee motivation; (iii) connecting the macro and micro perspectives by means of structuring and institutionalizing organization-wide processes. Welch changed GE from a government-oriented company to a market-oriented company, dedicated to value creation through competitiveness. This change expressed itself in the creation of performance measures that impacted the personal behavior of workers and managers by offering guidance and rewards. The connection between value creation and everyday behavior was made through structuring processes and systems that translated value creation into activities.

Thus, for instance, Welch built a training system that dealt intensively with the development of employees and managers, and instilled the notion of value creation through organization-wide performance measures and a process of defining and implementing stretch goals. He also instituted the learning and dissemination of best practices as well as process improvement through the Six Sigma (TQM) approach. Welch eased the control of GE’s head office and cut down on redundancies through a restructuring process. At the same time, he formulated effective strategic management processes that gave much more latitude to managers. To promote cooperation throughout the organization, Welch broke down barriers between divisions; to encourage the output of fresh ideas from below, he created a ‘workout’ process, in the form of a periodic workshop where suggestions for improving effectiveness were presented for discussion, most of which were accepted and implemented without delay. He also developed processes related to evaluation, coaching, promotion and rewards for managers, and is reported to have invested about 70% of his time in these processes (Welch & Byrne, Reference Welch and Byrne2001).

These structuring examples indicate the importance of the neglected component of leadership, which operates at the level of structuring processes. Thus, to fully and effectively exploit organizational potential, the leadership has to act on three levels: strategic leadership (the macro perspective); motivating individuals through transformational leadership (the micro perspective); and architectural leadership that structures processes (the meso perspective).

The VCL model adopts the value-based management approach, according to which the goal of a business is to increase its value (measured as a discounted cash flow) to its shareholders over time. In the long run, the approach also contributes to the other stakeholders, including customers and employees (Rappaport, Reference Raes, Heijltjes, Glunk and Roe1997; Copeland, Koller, & Murrin, Reference Cândido and Santos2010). The value-based management approach has been expanded into the value-focused management model (Ronen, Lieber, & Geri, Reference Van Rensburg, Davis and Venter2007; Ronen & Pass, Reference Ronen, Lieber and Geri2008). The latter approach identifies value drivers and focuses on creating value through them. The value drivers can be operational (like increasing output, reducing lead times), financial (changing capital structure, for instance) or strategic. The VCL model extends these approaches in that it directs the spotlight onto the role of leadership in creating value, specifies the systems and processes required to create value, and also relates to not-for-profit organizations, where value is added by improving performance in the core activity that derives from the organization’s goals.

The VCL model focuses on value creation and does not merely set strategic goals or attempt to motivate employees – practices that do not necessarily lead to added value. Setting value creation as a leading goal is a necessary condition, without which a business organization will not survive in the long term, but it is not a sufficient condition. It is possible, for instance, to create short-term value by financial or marketing maneuvering, but ‘the leader’s primary responsibility is… building the foundation for its continued success’ (Bennis & Nanus, Reference Bennis and Nanus1985: 211), which entails the construction of a suitable infrastructure that will provide the organization with the necessary capabilities.

Unlike the full-range leadership model (Bass, Reference Bass1985; Bass & Avolio, Reference Bass and Avolio1990), the VCL model does not map leadership styles according to categories of effectiveness and behaviors and place them side by side without integration, but rather suggests a comprehensive perspective. The key to effectiveness is the integration of the three main leadership approaches and the cooperation among leaders at various organizational levels. Thus, the proposed model integrates the levers and the effects of the three approaches to the organizational leadership approach described above. (i) Creating the direction, embodied in thinking, planning and implementing at the strategy level: the strategic leadership that sets goals. (ii) Motivating people to carry out assignments, embodied mainly in personal leadership, which deals with the psychological aspects of employees and impinges on their aspirations. (iii) Organizational structuring of the capabilities required to carry out the assignments, embodied in the processes that are required to improve the organization’s performance: the architectural leadership. The three categories of leadership complement and strengthen each other, so that the value they create is greater than the sum of their parts. The overall impact of the three levers creates a cumulative effect directed toward creating value for the organization.

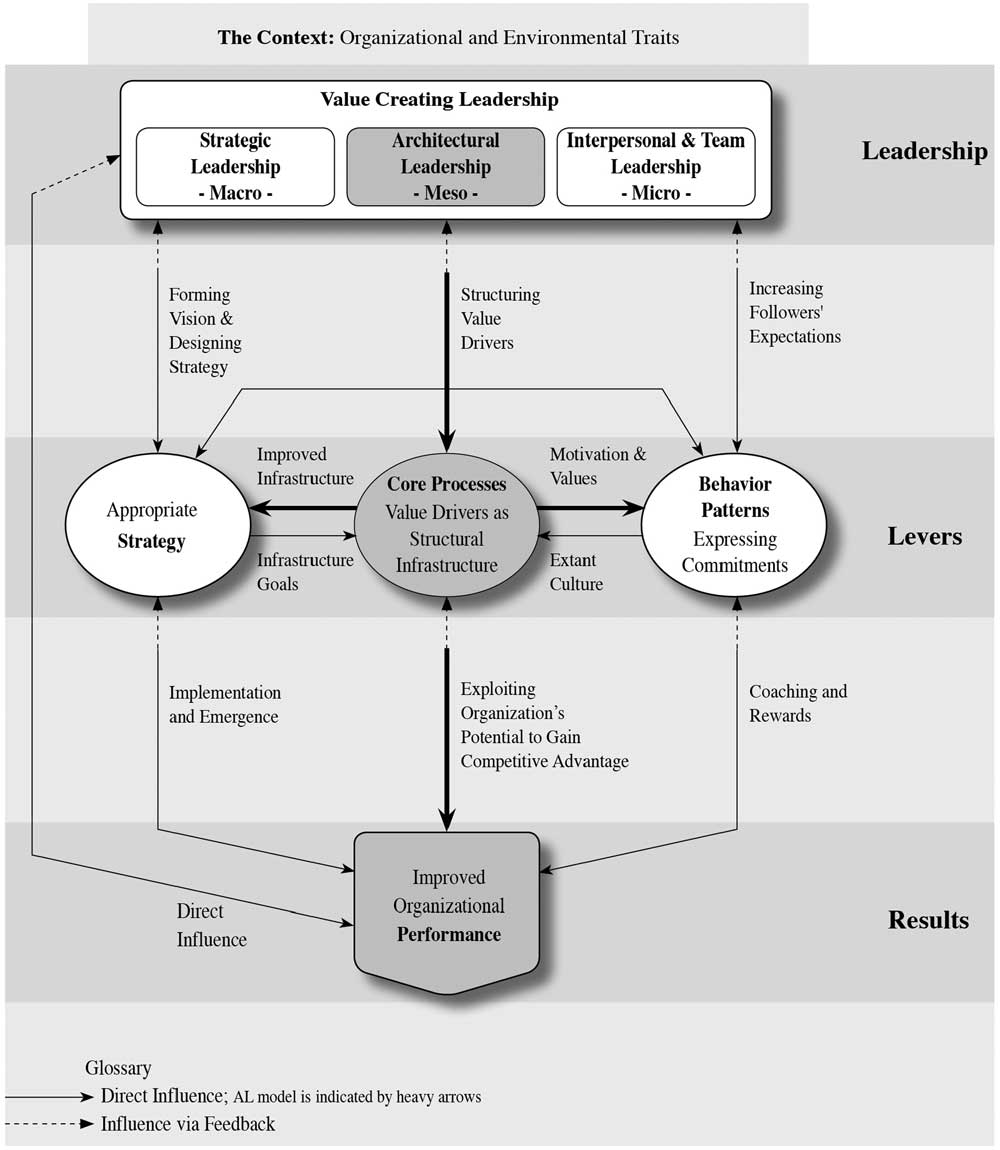

The full model is described in Figure 4, which has architectural leadership as its center (see Figure 3), bridging the gap between interpersonal (and team leadership) and strategic leadership (see Figure 1). The model describes the reciprocal relations among the three approaches and the reciprocal relations among the three levels of relating to them: leadership, levers and outcomes. To contend with the managerial bias of strategic management, strategic leadership includes leadership and vision components that are beyond strategic management, as well as an emergent strategy that complements the planned strategy (Mintzberg, Ahlstrand, & Lampel, Reference Mintzberg, Ahlstrand and Lampel1998).

Figure 4 The value-creating leadership model – at all organizational levels

To use the VCL model, no superman endowed with all the characteristics of the three types of leadership is needed. What is required from leaders is to learn, exercise and internalize the VCL model’s comprehensive point of view for organizational leadership, to develop leaders at all organizational levels accordingly, and to draw upon them to assist in implementing the model.

On the surface, and on principle, the organization’s leadership activates the levers in the following order: forming a strategy, structuring core processes and increasing followers’ expectations to create patterns of behavior expressing commitment. However, as can be seen from Figure 4, there is nothing orderly, simple or unidirectional about the process. It is rather a dynamic process with reciprocal influences among all the components. Thus, for instance, it can be seen that there is a connection between organizational performance and organizational levers, as well as a connection between organizational levers and decision making by the leadership – expressed by the dashed feedback arrows. The strategy provides objectives for patterns of behavior and core processes, and is influenced by the behavioral patterns and infrastructure granted by the core processes. The core processes also affect behavioral patterns through motivation and values, and are influenced by the existing culture.

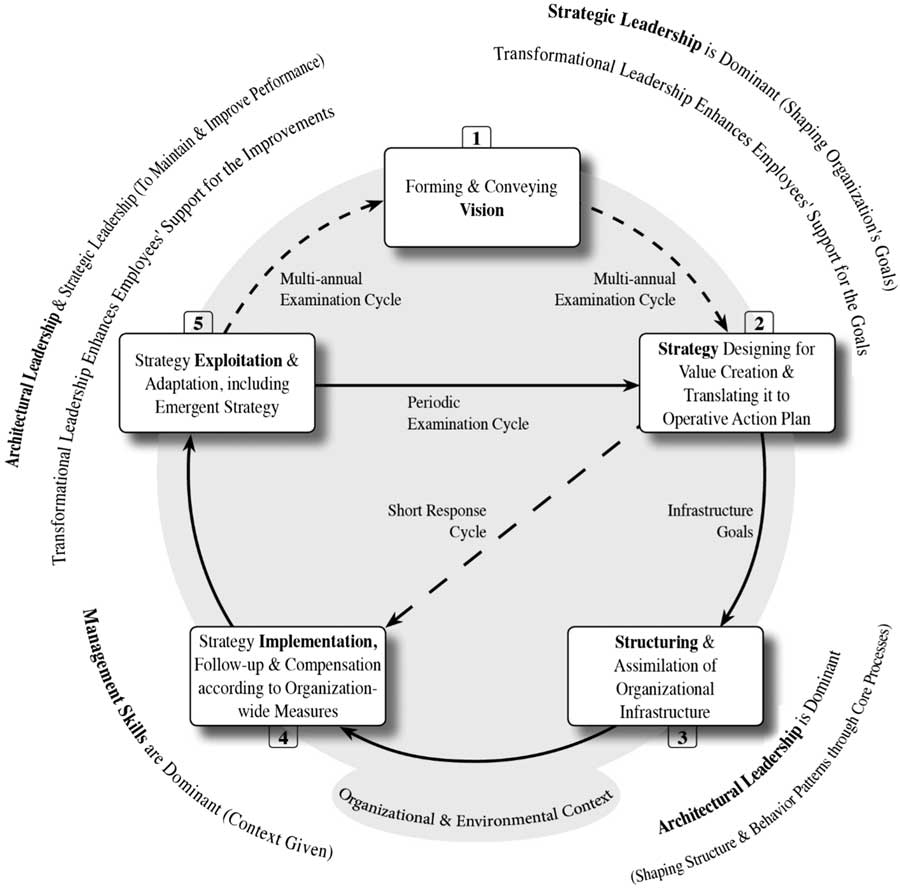

In order to demonstrate the principal order of the activities and the division of labor among the leadership components described in the VCL model, and to emphasize that we are talking about a cycle of ongoing activity, we suggest taking a process perspective, as described in Figure 5. The VCL cycle begins with forming a vision (Stage 1) and continues with the outlining of a strategy to realize the vision (Stage 2). In these stages, the strategic leadership component of VCL is the leading component. The VCL cycle continues with the structuring of capabilities to realize the strategy in practice and with the assimilation of these capabilities (Stage 3). Here, the architectural leadership component is dominant. In parallel, a strategy is actually implemented (Stage 4), while the skills required at this stage are mainly managerial, because the context is defined.

Figure 5 The value-creating leadership cycle – at all organizational levels

The VCL cycle ends with the strategic exploitation of the organization’s capabilities and their adaptation to the dynamic reality (Stage 5). This stage requires joint activity of the architectural and strategic VCL components. Once in a while, the value-creating leader re-examines whether the strategy is still appropriate (Sage 5) and, if necessary, sets a new cycle of value creation in motion by updating the strategy (Stage 2) or, infrequently, by updating the vision (Stage 1). Interpersonal leadership plays an important role in creating agreements and commitments (Boal & Hooijberg, Reference Boal and Hooijberg2001) to the organization’s goals and necessary improvements (Stages 1, 2 and 5). In other words, there are ongoing cycles of strategy updating, adapting of the structuring to circumstances, and motivating individuals to bring about new initiatives.

Together with the effectiveness that structuring achieves, the figure demonstrates the flexibility that is built into the structuring process by virtue of the ongoing adjustments (Stage 5), and the periodic re-examinations of the organization’s strategy and vision. Balancing the tension between the organization’s stability and efficiency and its flexibility, that is, its ‘dynamic efficiency’ (Ghemawat & Costa, Reference Ghemawat and Costa1993; Leana & Barry, Reference Leana and Barry2000), is essential in all of the organization’s three dimensions. In the strategic dimension, strategic planning by senior management (stability and efficiency) is meant to balance exploiting opportunities and initiatives that arise from below (flexibility); in the architectural dimension, introducing structured processes (stability and efficiency) is meant to balance their adaptation to the changing reality and their improvement in light of lessons learned (flexibility); in the interpersonal dimension, adherence to the assignment (stability) is meant to balance consideration for people and their needs (flexibility). This balancing act enables the combination of exploitation with exploration (March, Reference March1991): structuring core processes contributes to the exploitation of the organization’s capabilities; in parallel, the value-creating leader makes sure to explore new possibilities, both by encouraging emergent strategies, learning lessons and improving processes.

The Answers of the VCL Model to the Discussed Points of Criticism

We shall now examine whether the VCL model meets the requirements determined in light of the weaknesses identified and discussed in each perspective.

Addressing disadvantages related to the micro perspective on leadership

The VCL model addresses two shortcomings related to the micro perspective. First, spreading leadership at all organizational levels provides followers with leadership availability. The VCL model suggests nurturing leadership and spreading it throughout all echelons of the organization, through the decentralization of authority; the rationale being that leaders who are trained, coached and promoted according to their achievements will strive to attain the common goal of value creation. Thus, the model contributes to creating reserves of leadership and a continuum of appropriate leadership at the top executive team level (Tushman, Newman, & Romanelli, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1986; Grinyer, Mayes, & McKiernan, Reference Grinyer, Mayes and McKiernan1990; Kotter, Reference Kotter1990; Yukl, Reference Yukl2006). Different from other models, the VCL model does not attribute any special aura of uniqueness to the leader. On the one hand, there is no dealing with a ‘larger than life’ leader figure (Shamir, Reference Senge1995) at the top of the pyramid without whom nothing can happen. On the other hand, we are not talking about charismatic team leaders who get people to exert themselves simply out of respect and affection for them as personalities (Bass, Reference Bass1985; Lindholm, Reference Lindholm1988).

As Raes et al. (Reference Rappaport2011) noted, the academic literature has given little consideration to the interface between top and middle management. Attention has been limited mostly to involving middle management in the strategic conversation or in strategy formation (e.g., Westley, Reference Westley1990; Wooldridge & Floyd, Reference Wooldridge and Floyd1990). Though the importance of such cooperation is not to be denied, it is the structuring and processes that create the systematic mechanism by which the top management team participates and exerts a direct influence on middle management, as well as on the whole organization.

Second, VCL stresses the exercise of organization-wide influence through the practical guidance of daily activities. Through the structuring of core processes, the value-creating leader clarifies the main tasks and the expectations of the employees. By means of core processes, the leader provides employees with guidance and support, and directs their efforts toward useful channels. The strong leverage of core processes penetrates through levels of management and accustoms employees to desirable daily patterns of behavior. These activity patterns shape their attitudes and gradually their work values. For example, because core processes create structural linkage among groups that are separated by structural boundaries, but participate in a common process – they facilitate cooperation among these groups.

Addressing disadvantages of the macro perspective on leadership

The VCL model addresses three shortcomings of the macro perspective. First it focuses on building the means for strategy implementation. After formulating a strategy, the value-creating leader does not suffice with simply supervising its implementation. Rather, he or she leads the definition of requirements derived from the strategy regarding the development of an infrastructure that enables effective implementation of the strategy. To this end, a process leader, subordinate to the CEO or one of the deputies, should be appointed to each core process. The process leader is responsible for the community of practice engaged in the construction, operation and improvements of that process. In this way, the process leaders assist the CEO in fulfilling his/her overall responsibility for structuring the means by which to develop and implement the strategy. Design and implementation are ongoing processes because organizational design is never perfect and doesn’t last forever (Nadler & Tushman, Reference Nadler and Tushman1997).

Second, VCL stresses improving the organization’s capabilities as a result of attention to internal issues. The VCL model pays special attention to issues inside the organization and, in particular, to the definition, construction and improvement of core processes. These processes incorporate the organization’s resources and capabilities. They are sustainable, unique, exploitable and difficult to imitate. Therefore, they provide the organization with a sustained competitive advantage (Barney, Reference Barney1991; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Stein1997). Improving these capabilities allows the organization to realize its potential; developing new capabilities increases this potential. Moreover, after the leader builds the core processes, they do not remain static. Rather, they are constantly infused by the leader’s energy, steadily improved and adapted to the circumstances – through organizational learning and knowledge management – and therefore constitute dynamic capabilities. As such, they enable the organization to overcome structural rigidity and respond to environmental changes in dynamic industries (Rosenbloom, Reference Ronen and Pass2000).

Third, strategic leadership challenges the context and drives the organization toward its desired future. The organization naturally finds itself permanently under pressure and often even subject to erosion by the constant need to dedicate attention and energy to dealing with urgent problems (Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1973), sometimes at the expense of long-term considerations embedded in its strategy. The commonly heard expression – that the urgent supersedes the important – expresses this very well. In the dynamic reality of the current era, this problem becomes acute and, in addition, all strategies must be updated from time to time. Therefore, it is essential to give the organization a relatively stable picture of its desired future (Collins & Porras, Reference Conger and Kanungo1994) – that is, a corporate vision – to serve as the North Star in a turbulent sea.

The vision of the organization provides guidance and increases the attention invested in formulating an appropriate strategy and building the capabilities needed for its implementation. Thus, the operational capacity to implement a strategy is enhanced, and the prospects for the strategy’s success improve (Cândido & Santos, Reference Collins2015). Moreover, a vision gives meaning and purpose to the organization and its activities, beyond the capacity of what the individual can achieve on his/her own. Consequently, a vision strengthens employees’ solidarity with the organization and encourages them to initiate ideas and activities that will contribute to its development. Thus, the organizational vision contributes to the growth of the emergent strategy, which spurs innovation and progress, and complements the planned strategy (Collins & Porras, Reference Conger and Kanungo1994).

VCL – the ‘glue’ between the macro and micro perspectives

Working within the framework of two opposing views, VCL makes four main contributions. First, it provides a meso perspective that narrows the gap and incorporates opposing perspectives. It allows for choosing the golden path, which is neither a compromise between opposite views, nor their average. Achieving a balance between organizational stability and flexibility – the above mentioned ‘dynamic efficiency’ (Ghemawat & Costa, Reference Ghemawat and Costa1993) – demonstrates an example of how to find the golden path. There are many factors that accord the organization stability, thereby contributing to its efficiency: the organization’s vision, the strategy that derives from it, the systematic infusing of core processes (to prevent entropy), and the organizational structure that supports the processes. At the same time, the VCL model outlines various steps that ensure flexibility when coping with changing circumstances. A significant change in the circumstances requires a significant change in strategy, followed by a significant change in core processes (to prevent stagnation).

An analysis of the inherent opposing requirements (see Figure 2) clarifies the contribution of the VCL model. The value-creating leader is not bounded to the narrow perspective of a single leadership approach and a single lever of influence, and can therefore provide an appropriate answer to common organizational dilemmas.

Therefore, the VCL model we propose can serve as a compass to aid in the dynamic organization of our conflict-ridden reality, similar to Quinn’s competing values model (Reference Quinn1988). This balanced organizing becomes feasible thanks to the theoretical and practical framework proposed by the model for dealing with the four basic orientations presented in the four corners of Figure 2 (goal-oriented or infrastructure-oriented strategy; goal-oriented or infrastructure-oriented structure and processes), using the three leadership patterns integrated within the model. Conflict resolution using VCL facilitates exploitation of the organization’s potential and enhanced performance.

Second, structuring value-creating processes provides a system-wide explanation for organizational effectiveness. The concept of value creation in itself is meaningful to only a relatively small group of managers and cannot empower the employees unless it is translated into daily activities. Any effort on the part of the organization’s management to realize value creation directly, without defining a vision and activating the three organizational levers, will not be effective in the long term. However, activating the three organizational levers enables the value-creating leader to achieve sustainable value enhancement, based on an organizational infrastructure of core processes constructed precisely for this purpose. To exploit the organization’s potential and gain value enhancement, the leader must integrate the three organizational levers: inspiration (embodied in the vision), commitment (as an outcome of the influence of leadership) and guidance (through structured customer-oriented processes, organization-wide performance measures and coaching procedures).

Third, VCL offers a balanced human resource management approach, subject to the organization’s strategy. Instead of focusing excessively on the clear rational assumptions typical of many management models, or on the feelings of the individual (without taking a system-wide view), as happens in most of the existing psychological models that deal with leadership (Bass, Reference Bass2008), we adopt a holistic approach. The treatment of human resources is spread over three levels of analysis: at the micro perspective – motivating high performance; at the meso perspective – guidance and support through structured work-processes as well as processes for evaluating and rewarding daily effort and performance; at the macro perspective – connecting rewards with the organization’s value creation, as part of the strategic management (considering the fact that the good of the employees depends on the organization’s success). This prevents the tendency to give the individual a too low priority (as in strategic management) or a too high priority (as in transformational leadership).

Fourth, VCL stresses the magnetization of the organization’s components to align and harness them to its goal. The VCL model focuses on the interest of the entire organization and on nurturing, structuring and motivation directed at strengthening the forces that push toward integration and cohesion around the common goals. Every organization contains inherent forces that push toward fragmentation and the strengthening of local units for parochial reasons, at the expense of integration and overall interest. These forces are expressed in an excess of internal competitiveness, a lack of cooperation, the hiding of knowledge and other negative phenomena. Without proper leadership, the result is the disintegration of the organization into isolated units (i.e., silos). Political management, for instance, divides the organization into interested parties that seek local, short-term interests, and is viewed by Mintzberg as ‘a form of organizational illness’ (Reference Mintzberg1989: 236). Thus, implementing VCL can, to a large degree, spare the organization the high costs of futile power struggles that erode the organization’s interest. Moreover, according to Senge (Reference Senge1990b), organizations include three levels: events, patterns of behavior and the deepest level – systemic structures. Only the structures level – as described in the VCL framework – expresses an overall system view, as summarized by Senge: ‘Structural explanations are the most powerful. Only they address the underlying causes of behavior at a level such that patterns of behavior can be changed’ (Reference Senge1990b: 12).

The VCL model offers an organization-wide link – of managers and workers – to strategic goals through organization-wide core processes aimed at strategy implementation. Thus, for example, the contribution of managers to the overall success of the organization (using integrative measures) serves as the basis for evaluating their performance. In this way, in the inherent conflict between the centrifugal forces that push away from the center toward fragmentation and centripetal forces that push toward the center, the vector of the unifying forces wins out.

Contribution of the VCL Model to Organizational Leadership Theory

The VCL model can conceptually contribute to the discussed organizational levels. In relation to the micro perspective, the VCL model adds to the four transformational leadership behaviors (Bass, Reference Bass1985, Bass & Avolio, Reference Bass and Avolio1990) – which have a limited range – the requirement for leadership at all levels of the organization and outlines their relationship to core organizational processes and to the organizational strategy.

In relation to the macro perspective, the VCL model can clearly contribute to a better conceptualization of the somewhat blurry notion of vision. Vision stems from two behavioral elements of transformational leadership, that is inspirational motivation and intellectual stimulation. The VCL model argues for more orientation toward value enhancement and strategy that creates value. In so doing, it shifts the emphasis existing in most leadership models from interpersonal variables to more systemic mechanisms.

In relation to the meso perspective, the VCL expands on certain approaches located at the periphery of the strategic management literature, which have not been sufficiently integrated. The main additions are (i) emphasizing the centrality of core competences which, unlike the common discussion, are organization-wide core processes; (ii) the capabilities are built by the leader, rather than through bottom-up growth; (iii) the core processes aim high, but are developed step by step. The basic idea is that ‘leadership in everyday life’ is the ‘true story,’ rather than the outstanding leadership manifestation overly emphasized in traditional leadership theories (Popper, Reference Popper2012).

The structuring process contributes to the literature on leadership in organizations, because, due to the absence of an underlying process that explains the leader influence, many researchers have criticized its validity (Yukl, Reference Yukl1999; Boal & Hooijberg, Reference Boal and Hooijberg2001; Van Knippenberg & Sitkin, Reference Uygur2013; Day et al., Reference Day, Fleenor, Atwater, Sturm and McKee2014; Dinh et al., Reference Droge, Jayaram and Vickery2014).

The VCL model contributes to leadership theory by integrating three branches of leadership: strategic, architectural and micro interpersonal. VCL stresses leaders but view them as using strategy and structuring as levers. It moves leadership theory from a more closed-system that focuses on individuals, teams and their performance, to advancing the organization as a whole and adapting it to the changing environment. While emphasizing internal capabilities, VCL has always an eye on how these capabilities help compete externally. VCL moves strategic management closer to leadership by adopting a strategic leadership view of challenging the context and encouraging innovation, as well as by connecting managers at all organizational levels to the top executive team through vision, strategy, structuring and the common goal of value creation.

This connection is the axis of integrating all levels of activities described in the article. If the VCL model is embedded in the mind set of all mangers-leaders, their daily decisions and activities will be guided by this approach. In other words, unlike in the traditional approaches, all leaders, juniors as well as seniors, function as ’strategic leaders’ – harnessing all their efforts in light of advancing the value of the entire system. This view of organizational leadership is not only more integrative theoretically, it has an added value particularly in times of rapid changes in which mangers at all levels must understand the ‘big picture’ and act on it. Thus, the article present a framework in which the organizational notion of leadership as well as the self-perception of each manager as a leader is broader than solely affecting the motivation of their direct subordinates.

Conclusion

Organizational leadership is often viewed as one of the key organizational factors affecting organizational performance and sustainability. However, how this factor exactly affects these outcomes critically depends first on how leadership is conceptualized – as an interpersonal influence or as a force behind a firm’s strategy – and second, on how different levers at leaders’ disposal come together.

Extant leadership theory tends to adopt either a micro approach – based on interpersonal influence, or a strategic approach – which focuses on strategic choice and positioning in the firm’s environment. This polarization and associated fragmentation often leads to an incomplete view of what leadership can do to influence organizational outcomes. The meso approach of architectural leadership and its stress on structuring highlights the need for leadership theory to better recognize processes – particularly the ones that can have more sustained and pervasive results than their micro and macro counterparts.

The importance of this meso approach, while distinct from the interpersonal and strategic leadership approaches, lies in complementing these other leadership levers. VCL brings these three levers together, bridging the cross-level theoretical divide between micro and macro, as well as promoting a process approach to leadership. The practical contribution is also significant as it invites leaders to take a broader view of how they can affect long-term organizational outcomes. By highlighting structuring through communities of practice, it reinforces approaches relating to individual growth and motivation and, at the same time, fleshes out organizational strategy in ways that magnify its effects, making them more pervasive and sustainable.

Future research should analyze and determine with greater precision the links among architectural leadership, strategic leadership and the existing leadership concepts, together with VCL measures. Furthermore, the VCL model needs elaboration in terms of ‘soft’ areas that are beyond concrete operations, especially values and culture. For example, the core processes of human resources management affect the values of the organization in areas such as spurring innovation and encouraging organizational learning.

From an empirical point of view, there is a need to assess the validity of the propositions of the VCL model, represented by the arrows in the model’s diagram, as well as the model’s contribution to value creation. One way to test the propositions is to conduct a field study, comparing the performance of large companies, some of which have adopted the model and some of which have not.

Outstanding CEOs have used their good intuition to enhance the value of their companies by integrating the three leadership perspectives described above, and by building an appropriate infrastructure to provide an enduring competitive advantage. Examples include William McKnight and his successors, who built an infrastructure for innovation at 3 M; Michael Dell, who structured ‘direct sell’ at Dell; and Fred Smith, who structured fast delivery at FedEx. These examples represent methods related to organizational level design and application. Indeed, ongoing success can neither be described in anecdotal terms, nor ascribed to a special talent in a specific area, and certainly not to a one-time inspiration.

By providing the conceptual framework for an outlook and a methodical, effective and coherent way of leading an organization – the VCL model frees organizations from their dependence on ‘executive stars,’ who possess special intuition and insight. The VCL can be applied to training, developing, coaching and promoting managers and to leading processes that increase the value of the organization – without relying on a charismatic leader or a superhero.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Moshe Farjoun at Schulish School of Business, York University, for his vital contribution, as well as JMO editors and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the draft of this paper.